Filter vs. Wrapper Feature Selection: A Comparative Guide for Biomedical Data Analysis

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of filter and wrapper feature selection methods, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development and biomedical sciences.

Filter vs. Wrapper Feature Selection: A Comparative Guide for Biomedical Data Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of filter and wrapper feature selection methods, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development and biomedical sciences. With the growing challenge of high-dimensional data in genomics and transcriptomics, selecting the right features is crucial for building accurate, interpretable, and generalizable predictive models. We explore the foundational principles, methodological applications, and practical trade-offs of these techniques. Through a troubleshooting lens, we address common pitfalls like overfitting and computational costs. The article concludes with a validation framework, comparing performance metrics and offering guidance on method selection to optimize drug response prediction and biomarker discovery, directly addressing the needs of modern precision medicine.

Understanding Feature Selection: Core Concepts and Critical Need in Biomedicine

The 'Curse of Dimensionality' in Genomic and Clinical Datasets

The "Curse of Dimensionality" describes a set of phenomena and analytical challenges that arise when working with data in a high-dimensional space, particularly when the number of features (dimensions) vastly exceeds the number of observations (samples) [1]. In genomic and clinical research, this is not a theoretical concern but a fundamental practical constraint. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) routinely analyze millions of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), while modern clinical datasets encompass diverse data streams from medical imaging to continuous wearable sensor data, speech samples, and electronic health records [2] [3]. This high-dimensionality leads to data sparsity, where the available samples become isolated points in a vast, mostly empty space, making it difficult to detect robust patterns and increasing the risk of identifying spurious correlations [3] [1].

A critical consequence in biomarker discovery is the Biomarker Uncertainty Principle, which posits that a molecular signature can be "either parsimonious or predictive, but not both" [4]. This creates a pressing need for sophisticated feature selection methods—techniques designed to identify the most relevant and informative variables from a vast initial set. Within this context, filter methods and wrapper methods represent two fundamentally different philosophical approaches to tackling this problem, each with distinct strengths and weaknesses in the face of the curse of dimensionality [5] [6].

Methodological Comparison: Filter vs. Wrapper Feature Selection

Feature selection is a critical preprocessing step to mitigate the curse of dimensionality by reducing the number of features, thus speeding up learning and enhancing model performance [6]. The two primary approaches, filter and wrapper, offer different strategies.

Filter methods evaluate the relevance of features independently of the classification model, relying solely on the intrinsic properties of the data [5]. Common techniques include correlation-based feature selection and mutual information [5]. A key advantage is their computational efficiency, as they do not involve training a predictive model, making them suitable for high-dimensional datasets with thousands of features [6]. However, a significant drawback is that they assess features in isolation, potentially overlooking complex interactions between features that could be crucial for prediction [6]. They may eliminate features that are individually weak but powerful in combination with others.

Wrapper methods, in contrast, utilize a specific predictive model to evaluate feature subsets [5]. Techniques like Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) iteratively select features based on their importance in a predictive model [5]. The primary strength of wrappers is their ability to account for feature dependencies and interactions, often leading to higher predictive accuracy [6]. The trade-off is their computational intensity, as they require repeatedly training and evaluating a model, which can be prohibitive for very large feature sets [6]. They are also more prone to overfitting if not properly validated [6].

Table 1: Comparison of Filter and Wrapper Feature Selection Methods

| Characteristic | Filter Methods | Wrapper Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Selects features based on intrinsic data properties and statistical measures [5]. | Selects features based on their performance in a predictive model [5]. |

| Computational Cost | Low; fast and scalable [6]. | High; computationally intensive and slower [6]. |

| Risk of Overfitting | Lower, as no model is involved in selection. | Higher, requires careful validation to mitigate [6]. |

| Consideration of Feature Interactions | No; evaluates features individually [6]. | Yes; accounts for feature dependencies [6]. |

| Primary Advantage | Computational efficiency. | Potential for higher predictive accuracy [6]. |

| Key Limitation | May miss relevant features that are only predictive in combination [6]. | Computationally prohibitive for massive feature sets [6]. |

Experimental Evidence and Performance Benchmarking

Empirical studies provide critical insights into the practical performance of filter and wrapper methods. A 2025 comparative study on Speech Emotion Recognition (SER), a domain with high-dimensional acoustic feature vectors, offers a clear benchmark [5]. Researchers evaluated filter methods (correlation-based, mutual information) and the wrapper method RFE using three different feature sets, measuring performance via accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score.

Table 2: Performance of Feature Selection Methods in Speech Emotion Recognition [5]

| Feature Set & Method | Number of Features Selected | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | F1-Score (%) | Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Features | 170 | - | - | - | 61.42 |

| Mutual Information (Filter) | 120 | 65.00 | 65.00 | 65.00 | 64.71 |

| Correlation-Based (Filter) | 63 | 64.00 | 64.00 | 64.00 | 63.80 |

| RFE (Wrapper) | 120 | 64.00 | 64.00 | 64.00 | 63.59 |

The results demonstrate that feature selection consistently improved performance over using all available features. The filter method Mutual Information achieved the highest accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score, all at 65% [5]. This indicates that for this specific high-dimensional task, a filter method was not only computationally efficient but also most effective. The wrapper method, RFE, showed competitive but slightly lower performance, stabilizing its results when using a sufficient number of features (around 120) [5].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Speech Emotion Recognition

To ensure reproducibility, the core methodology from the SER study is outlined below [5].

Objective: To compare the effectiveness of filter and wrapper-based feature selection methods for emotion recognition from speech signals.

Datasets: The experiment utilized three publicly available audio datasets:

- Toronto Emotional Speech Set (TESS)

- Crowd-sourced Emotional Multimodal Actors Dataset (CREMA-D)

- Ryerson Audio-Visual Database of Emotional Speech and Song (RAVDESS)

Feature Extraction: A comprehensive set of 170 acoustic features was extracted from the speech signals, including:

- Mel-frequency cepstral coefficients (MFCCs): Captures spectral properties.

- Root mean square energy (RMS): Measures signal energy.

- Zero crossing rate (ZCR): Estimates signal frequency.

- Spectral centroid frequency (SCF): Indicates the "center of mass" of the spectrum.

- Chromagram: Represents tonal content.

- Tonnetz: Encodes harmonic relationships.

- Mel spectrogram: Provides a time-frequency representation.

Feature Selection & Model Training:

- Filter Methods: Features were ranked using correlation-based and mutual information criteria. Different thresholds were applied to select feature subsets of varying sizes.

- Wrapper Method: The Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) method was used with a classifier to iteratively remove the least important features.

- Evaluation: All selected feature subsets were used to train a classification model. Performance was assessed using k-fold cross-validation to compute precision, recall, F1-score, and accuracy.

Advanced Hybrid Frameworks and Future Directions

Recognizing the limitations of pure filter or wrapper approaches, recent research has focused on hybrid frameworks that seek to combine their strengths. The core challenge in such hybrids is managing the inherent conflict: filters efficiently remove features but may discard some that are useful in combination, while wrappers can find these interactions but are computationally costly and prone to overfitting [6].

A novel proposed framework introduces a three-component filter-interface-wrapper architecture to mediate this collaboration [6]. The key innovation is an interface layer that employs Importance Probability Models (IPMs). These models are initialized using the feature rankings from a fast filter method. This information then guides the wrapper's search process (e.g., an evolutionary algorithm), iteratively refining the feature probabilities based on the wrapper's performance feedback [6]. This creates a dynamic synergy where the filter provides a robust starting point for exploration, and the wrapper performs targeted exploitation, potentially leading to more optimal feature subsets than either method could achieve alone.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

For researchers designing experiments in high-dimensional genomics and clinical data, selecting appropriate computational tools and reagents is paramount. The following table details key solutions.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for High-Dimensional Data Analysis

| Item Name | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| PySpark | A Python API for Apache Spark, used for distributed processing of extraordinarily large genomic datasets to overcome computational bottlenecks [2]. |

| Multifactor Dimensionality Reduction (MDR) | A non-parametric method to classify multi-dimensional genotypes into one-dimensional binary attributes for detecting gene-gene interactions [2]. |

| Principal Component Analysis (PCA) | A dimensionality reduction technique to project high-dimensional data into a lower-dimensional space, preserving global data structure [7]. |

| t-SNE & UMAP | Non-linear dimensionality reduction techniques ideal for visualizing and exploring clusters in high-dimensional data like single-cell RNA sequencing [7]. |

| LASSO & Elastic Net | Regularization techniques that perform feature selection by shrinking less important coefficients to zero, helping to build parsimonious models [4] [7]. |

| Random Forests / Gradient Boosting | Tree-based ensemble methods that provide robust feature importance rankings and handle complex, non-linear relationships [2] [7]. |

| Deep Learning (CNNs/RNNs) | Used to capture complex, non-linear patterns and dependencies in sequential genomic data or structured clinical data [2] [7]. |

| k-Fold Cross-Validation | A model validation technique critical for providing reliable performance estimates and guarding against overfitting in high-dimensional settings [7]. |

The curse of dimensionality presents a formidable challenge in genomic and clinical research, where the sheer volume of features can obscure true biological signals. This comparative analysis demonstrates that no single feature selection method is universally superior. Filter methods offer speed and scalability, making them ideal for initial analysis of massive datasets, while wrapper methods can yield higher accuracy by accounting for feature interactions at a greater computational cost. The emerging paradigm of hybrid filter-wrapper frameworks, facilitated by an intelligent interface, represents a promising path forward. By strategically leveraging the strengths of both approaches, researchers can more effectively navigate the high-dimensional landscape, ultimately accelerating the discovery of robust biomarkers and the development of precise clinical tools.

In the realm of data science and machine learning, feature selection serves as a fundamental preprocessing technique that directly addresses the challenges posed by high-dimensional data. The process involves identifying and selecting the most relevant subset of features from the original dataset to improve model performance, enhance interpretability, and reduce computational costs [8] [9]. As datasets continue to grow in both sample size and feature dimensionality across domains ranging from bioinformatics to network traffic analysis, the strategic implementation of feature selection has become increasingly critical for developing efficient and effective machine learning models [9] [10].

The primary goals of feature selection align with core challenges in machine learning: improving predictive accuracy by eliminating irrelevant and redundant features that may introduce noise; enhancing interpretability by providing domain experts with a more concise and relevant feature subset; and increasing computational efficiency by reducing the number of attributes that models must process [8] [9]. These objectives are particularly vital in fields like drug development, where model interpretability can be as crucial as predictive performance for understanding biological mechanisms [11] [12].

Methodological Approaches: Filter, Wrapper, and Embedded Methods

Feature selection methodologies are broadly categorized into three main approaches, each with distinct mechanisms, advantages, and limitations. Understanding these fundamental approaches provides the necessary context for comparing their performance and applicability across different domains and data characteristics.

Filter Methods: Statistical and Model-Independent Selection

Filter methods evaluate features based on statistical measures and intrinsic properties of the data, independent of any specific machine learning algorithm [8] [13]. These methods typically assess the relevance of features by examining their correlation with the target variable using metrics such as mutual information, correlation coefficients, or ANOVA F-value [14] [13]. By operating independently of a learning algorithm, filter methods offer significant computational advantages, making them particularly suitable for high-dimensional datasets and preliminary feature screening [8] [13].

The primary strength of filter methods lies in their computational efficiency and scalability to datasets with large numbers of features [8] [13]. This efficiency comes with the limitation of potentially overlooking complex feature interactions that might be important for prediction, as features are evaluated individually rather than in combination [6] [13]. Common filter techniques include correlation-based feature selection, mutual information, variance threshold, and select K best features based on statistical tests [14] [5].

Wrapper Methods: Performance-Driven and Model-Specific Selection

Wrapper methods approach feature selection as a search problem, where different feature subsets are evaluated based on their performance with a specific machine learning algorithm [8] [13]. These methods employ heuristic search strategies to navigate the feature space, using the model's performance metric (e.g., accuracy, F1-score) as the objective function to identify optimal feature subsets [6] [8]. Common wrapper approaches include sequential feature selection (forward or backward), recursive feature elimination (RFE), and evolutionary algorithms like Particle Swarm Optimization [15] [13].

The key advantage of wrapper methods is their ability to account for feature interactions and dependencies, often resulting in feature subsets that yield superior predictive performance for the specific model used in the selection process [6] [8]. This performance benefit comes with substantial computational costs, as the model must be trained and evaluated repeatedly for different feature subsets, making wrapper methods less suitable for very high-dimensional datasets [8] [13]. Additionally, wrapper methods carry a higher risk of overfitting, particularly with small sample sizes [8].

Embedded Methods: Integration of Selection and Model Training

Embedded methods integrate feature selection directly into the model training process, allowing the algorithm to dynamically determine feature importance during learning [15] [8]. These approaches combine the benefits of both filter and wrapper methods by performing feature selection as an inherent part of model construction, typically through regularization techniques or tree-based importance measures [15] [8]. Common examples include LASSO and Ridge regression, which use L1 and L2 regularization respectively to shrink coefficients, and tree-based algorithms like Random Forest and XGBoost that provide native feature importance scores [11] [14].

Embedded methods typically offer a favorable balance between computational efficiency and model-specific optimization [8]. They capture feature interactions more effectively than filter methods while being less computationally intensive than wrapper approaches [15] [8]. The main limitations include reduced interpretability compared to filter methods and algorithm-specific implementation that may not transfer well across different modeling techniques [8].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Feature Selection Methodologies

| Aspect | Filter Methods | Wrapper Methods | Embedded Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Mechanism | Statistical measures independent of model | Model performance evaluation | Integration with model training |

| Computational Cost | Low | High | Moderate |

| Risk of Overfitting | Low | High | Moderate |

| Feature Interactions | Not considered | Accounted for | Partially accounted for |

| Model Specificity | Model-agnostic | Model-specific | Model-specific |

| Primary Advantages | Fast execution, scalable to high dimensions | Potentially higher accuracy | Balance of efficiency and performance |

| Key Limitations | Ignores feature dependencies | Computationally expensive, overfitting risk | Limited interpretability, model-dependent |

Comparative Performance Analysis: Experimental Evidence Across Domains

Empirical evaluations across diverse domains provide critical insights into the performance characteristics of filter, wrapper, and embedded feature selection methods. The following comparative analysis synthesizes findings from recent studies in network traffic classification, drug response prediction, and speech emotion recognition to quantify the trade-offs between these approaches.

Network Traffic Classification: Accuracy-Efficiency Tradeoffs

A 2025 study on encrypted video traffic classification directly compared filter, wrapper, and embedded approaches using real-world traffic traces from YouTube, Netflix, and Amazon Prime Video [15]. The researchers evaluated methods based on F1-score and computational efficiency, revealing distinct performance trade-offs. The filter method demonstrated low computational overhead with moderate accuracy, while the wrapper method achieved higher accuracy at the cost of significantly longer processing times [15]. The embedded method provided a balanced compromise by integrating feature selection within model training, offering intermediate performance on both accuracy and efficiency metrics [15].

This domain exemplifies the critical trade-off between computational resources and predictive performance. For applications requiring real-time or near-real-time processing of high-dimensional network data, filter methods may be preferable despite their moderate accuracy, while wrapper methods become viable for offline analysis where maximum accuracy is prioritized over efficiency [15].

Drug Response Prediction: Biological Interpretability Considerations

In biomedical applications, particularly drug response prediction (DRP), feature selection methods must balance predictive accuracy with biological interpretability. A 2024 comprehensive evaluation of feature reduction methods for DRP compared nine knowledge-based and data-driven approaches using cell line and tumor data [11]. The study employed six machine learning models with over 6,000 runs to ensure robust evaluation, finding that transcription factor activities outperformed other methods in predicting drug responses [11].

Notably, the analysis revealed that ridge regression performed at least as well as any other machine learning model across different feature reduction methods [11]. This finding highlights the importance of selecting appropriate feature selection techniques based on the specific modeling approach and dataset characteristics. Furthermore, knowledge-based feature selection methods demonstrated advantages in interpretability, enabling researchers to connect selected features with established biological pathways and mechanisms [11].

Table 2: Performance Comparison in Drug Response Prediction [11]

| Feature Selection Method | Category | Key Findings | Interpretability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transcription Factor Activities | Knowledge-based | Best performance for 7 of 20 drugs | High |

| Pathway Activities | Knowledge-based | Smallest feature set (14 features) | High |

| Drug Pathway Genes | Knowledge-based | Largest feature set (3,704 genes average) | High |

| Landmark Genes | Knowledge-based | Captures significant transcriptome information | Moderate |

| Highly Correlated Genes | Data-driven | Drug-specific gene selection | Low to Moderate |

| Principal Components | Data-driven | Captures maximum variance | Low |

| Autoencoder Embedding | Data-driven | Captures nonlinear patterns | Low |

Speech Emotion Recognition: Empirical Accuracy Metrics

Research in speech emotion recognition provides additional comparative metrics for filter and wrapper methods. A 2025 study evaluated correlation-based filter methods, mutual information filters, and recursive feature elimination (RFE) as a wrapper approach using three different feature sets extracted from speech signals [5]. The results demonstrated that using all available features (170 total) yielded an accuracy of 61.42%, but included irrelevant data that reduced efficiency [5].

Mutual information with 120 selected features achieved the highest performance, with precision, recall, F1-score, and accuracy at 65%, 65%, 65%, and 64.71% respectively [5]. Correlation-based methods with moderate thresholds also performed well, balancing simplicity and accuracy, while RFE methods showed consistent improvement with more features, stabilizing around 120 features [5]. This study illustrates how appropriate feature selection can simultaneously improve both accuracy and efficiency compared to using the complete feature set.

Advanced Hybrid Frameworks and Emerging Approaches

Recent research has focused on developing hybrid approaches that combine the strengths of multiple feature selection methodologies while mitigating their individual limitations. These advanced frameworks represent the cutting edge of feature selection research, offering promising directions for addressing complex data challenges.

Filter-Wrapper Mediation Frameworks

A novel three-component framework of filter-interface-wrapper addresses the inconsistencies between filter and wrapper components by incorporating an interface layer that mediates their collaboration [6]. This approach employs learnable Importance Probability Models (IPMs) that begin with filter information and iteratively refine feature significance through population generation and mutation in the wrapper component [6]. The interface manages the transition procedure during collaboration between filter and wrapper by initially focusing on filter insights and gradually shifting to the wrapper as it matures [6].

Experimental results on 15 multi-label datasets demonstrated that this hybrid framework significantly improves feature selection outcomes, balancing efficiency and predictive power in complex scenarios [6]. The approach enhances exploration-exploitation balance in the solution space by combining multiple IPMs with an evolutionary wrapper, effectively using filter methods for broad exploration while leveraging wrapper methods for targeted refinement [6].

Adaptive Cutoff Optimization for Large-Scale Data

The FeatureCuts algorithm addresses the challenge of determining optimal feature cutoffs in hybrid feature selection, particularly for large-scale datasets [13]. This approach reformulates the selection process as an optimization problem and implements a Bayesian Optimization and Golden Section Search framework that adaptively selects the optimal cutoff with minimal overhead [13]. Evaluated on 14 publicly available datasets and one industry dataset, FeatureCuts achieved on average 15 percentage points more feature reduction and up to 99.6% less computation time while maintaining model performance compared to existing state-of-the-art methods [13].

When the features selected by FeatureCuts were used in a wrapper method such as Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), the hybrid approach enabled 25 percentage points more feature reduction, required 66% less computation time, and maintained model performance compared to PSO alone [13]. This demonstrates the significant efficiency gains possible through carefully designed hybrid methodologies, especially for enterprise-scale applications with large feature sets.

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Considerations

Robust experimental design is essential for meaningful comparison of feature selection methods. This section outlines common evaluation frameworks and methodological considerations based on current research practices.

Standardized Evaluation Frameworks

Comprehensive evaluation of feature selection methods requires assessment across multiple dimensions, including selection accuracy, prediction performance, stability, and computational efficiency [9]. A recently developed open Python framework for benchmarking feature selection algorithms facilitates standardized comparison using metrics that appraise selection accuracy, selection redundancy, prediction performance, algorithmic stability, selection reliability, and computational time [9].

This framework employs repeated random-subsampling cross-validation, typically with 100 random splits of 80% training and 20% testing data, to ensure robust performance estimation [11] [14]. Nested cross-validation within the training data is recommended for hyperparameter tuning to prevent overfitting and provide unbiased performance assessment [11].

Domain-Specific Methodological Adaptations

Different application domains require specialized methodological considerations for feature selection:

Drug Response Prediction: Studies typically employ molecular profiling data (e.g., gene expression) from databases like GDSC, CCLE, or PRISM, with drug responses measured as area under the dose-response curves (AUC) or IC50 values [11] [14]. Feature selection must account for biological interpretability alongside predictive accuracy.

Network Traffic Classification: Methods utilize statistical characteristics of data flows (average bit rate, variance, maximum/minimum bit rate) while maintaining resilience against encryption and obfuscation techniques [15]. Computational efficiency is particularly important for real-time implementation.

Microarray Data Analysis: Extreme high dimensionality with small sample sizes necessitates feature selection methods that effectively control overfitting risk while preserving biological relevance [10]. Stability of selected features across different data subsets is a critical consideration.

Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Implementing feature selection methodologies requires specific computational tools and resources. The following table details essential "research reagents" for experimental feature selection research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Feature Selection Experiments

| Resource | Type | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| GDSC/CCLE Databases | Biological Dataset | Provides molecular profiles and drug response data for cancer cell lines | Drug response prediction [11] [14] |

| PRISM Dataset | Biological Dataset | Comprehensive drug screening resource with cancer cell lines | Drug response prediction with recent data [11] |

| LINCS L1000 Dataset | Biological Reference Set | Set of ~1,000 genes capturing significant transcriptome information | Feature selection for gene expression data [14] |

| Scikit-learn Library | Computational Tool | Python library implementing basic filter, wrapper, and embedded methods | Accessible feature selection for researchers [14] |

| Custom Python Benchmarking Framework | Computational Tool | Open-source framework for standardized feature selection comparison | Comparative evaluation of algorithms [9] |

| TESS/CREMA-D/RAVDESS | Speech Dataset | Audio datasets with emotional speech recordings | Speech emotion recognition research [5] |

| YouTube/Netflix/Amazon Prime Traces | Network Dataset | Real-world encrypted video traffic data | Network traffic classification studies [15] |

The comparative analysis of filter, wrapper, and embedded feature selection methods reveals a consistent trade-off between computational efficiency and predictive performance. Filter methods offer speed and scalability, wrapper methods provide potentially higher accuracy through feature interaction analysis, and embedded approaches strike a balance between these competing objectives [15] [8] [13]. The optimal choice depends on specific application requirements, including dataset characteristics, computational resources, interpretability needs, and performance priorities.

Future research directions include developing more sophisticated hybrid frameworks that dynamically adapt to data characteristics [6] [13], creating specialized methods for emerging data types such as LLM embeddings [13], and improving the stability and reproducibility of feature selection algorithms [9]. As data complexity continues to grow across scientific and industrial domains, advanced feature selection methodologies will remain essential for building accurate, efficient, and interpretable machine learning systems.

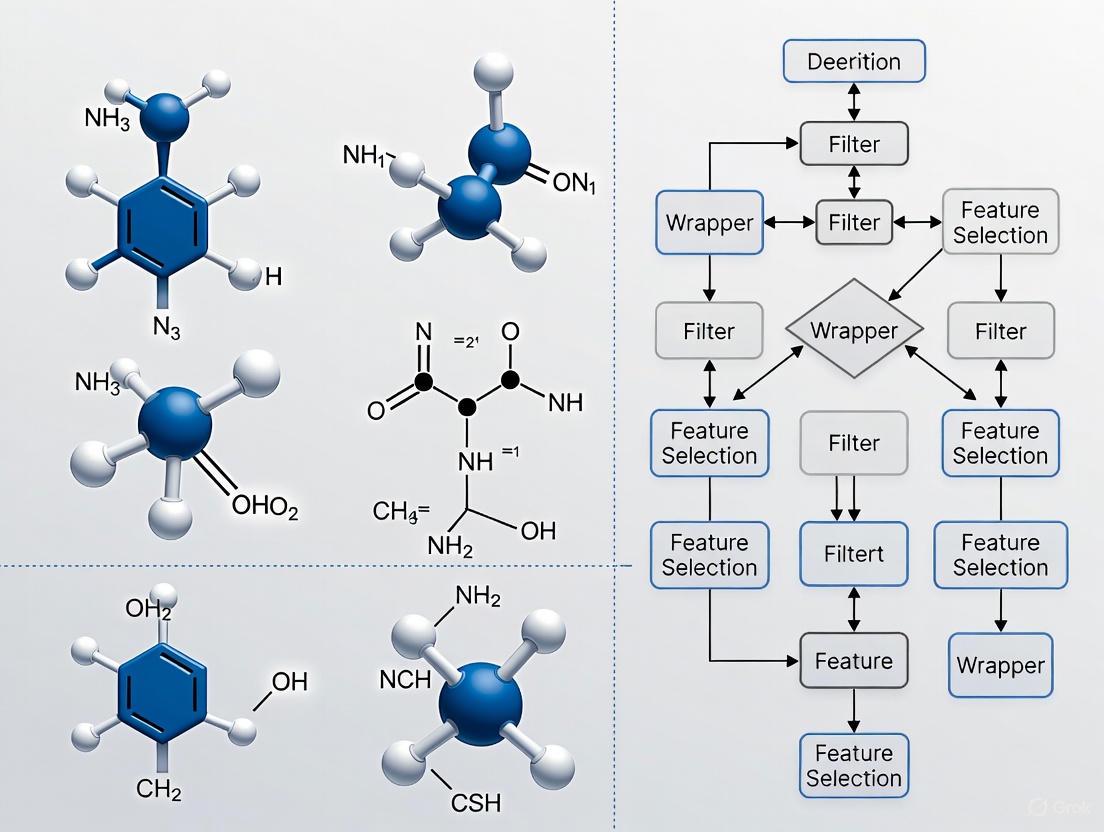

Feature Selection Method Workflow Comparison

Hybrid Filter-Wrapper Framework with Mediation

In the realm of data mining and machine learning, the curse of dimensionality presents a significant challenge for researchers and practitioners alike. Feature selection (FS) has emerged as a fundamental data pre-processing technique to mitigate this challenge by eliminating irrelevant and redundant features, thereby reducing computational costs, improving model accuracy, and enhancing data interpretability [9]. These methods are broadly categorized into three main paradigms: filter, wrapper, and embedded methods. A comprehensive understanding of these approaches is crucial for developing robust predictive models, particularly in data-intensive fields such as bioinformatics and drug development. This guide provides an objective comparison of these methodologies, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols, to inform their application in scientific research.

Feature selection techniques are designed to identify the most relevant subset of features from a larger pool. The table below summarizes the core characteristics, advantages, and disadvantages of the three primary approaches.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Feature Selection Methods

| Method Type | Core Principle | Key Advantages | Key Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Filter Methods | Selects features based on statistical measures (e.g., variance, correlation, mutual information) independently of a learning algorithm [16] [17]. | Computationally efficient and fast; Model-agnostic, providing generalizable results; Resistant to overfitting [15] [16]. | Ignores feature interactions with the model; May select redundant features without considering feature dependencies [15] [18]. |

| Wrapper Methods | Evaluates feature subsets by training and assessing a specific machine learning model's performance (e.g., accuracy, F1-score) [16] [19]. | Considers feature interactions; Typically achieves higher model accuracy by tailoring the subset to a specific classifier [15] [16]. | Computationally expensive and slow, especially with many features; Prone to overfitting if not properly cross-validated [16] [19]. |

| Embedded Methods | Integrates the feature selection process directly into the model training phase, often using regularization techniques [15] [18]. | Balances computational cost and performance; Model-specific, leading to optimized feature sets; More efficient than wrapper methods [15] [20]. | Limited generalizability as the selected features are tied to a specific model type [18]. |

The following diagram illustrates the typical workflow for applying these three feature selection methods in a machine learning pipeline.

Experimental Comparisons and Performance Data

Comparative Evaluation in Video Traffic Classification

A study on encrypted video traffic classification provides a direct comparison of the three approaches, evaluated using performance metrics like the F1-score and computational efficiency [15].

Table 2: Performance in Video Traffic Classification [15]

| Feature Selection Method | Representative Algorithms | Performance | Computational Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Filter | Correlation-based Feature Selection (CFS) | Moderate Accuracy | Low Overhead, Fast |

| Wrapper | Sequential Forward Selection (SFS) | Higher Accuracy | High Overhead, Slow |

| Embedded | LassoNet | Balanced Compromise | Moderate Efficiency |

The study concluded that the filter method offered the lowest computational overhead, the wrapper method achieved higher accuracy at the cost of longer processing times, and the embedded method provided a balanced compromise [15].

Comparative Evaluation in Geoscience

Another comparative study in the field of rockfall susceptibility prediction (RSP) employed multiple algorithms from each category, using a Random Forest (RF) model for final prediction [21].

Table 3: Performance in Rockfall Susceptibility Prediction [21]

| Feature Selection Method | Representative Algorithms | Best Performing Model | Model Performance (AUC) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Filter | ReliefF, Chi-square | Chi-square-RF | 0.865 |

| Wrapper | Genetic Algorithm (GA), Binary PSO (BPSO) | BPSO-RF | 0.891 |

| Embedded | L1-norm Minimization (LML), RFE | LML-RF | 0.874 |

The results demonstrated that the wrapper method, specifically the BPSO-RF model, achieved the best performance across all metrics, including AUC, Accuracy, Recall, and F1 Score. The study attributed this superiority to the wrapper's ability to account for mutual information between features, effectively removing redundancy and optimizing the prediction model [21].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

General Workflow for Comparative Studies

A standardized protocol for comparing feature selection methods involves several key stages, as utilized in the cited research [15] [21].

1. Data Collection and Pre-processing: Researchers collect a real-world dataset relevant to the domain. For example, a video traffic study might gather traffic traces from streaming platforms like YouTube, Netflix, and Amazon Prime Video [15]. A geoscience study might compile an inventory of historical rockfall events and related environmental factors [21]. Data is then cleaned and normalized.

2. Preliminary Influencing Factor Selection: A wide range of potential features (e.g., 21 factors in the rockfall study) is initially selected to establish an evaluation system [21].

3. Application of Feature Selection Algorithms: Multiple FS algorithms from the filter, wrapper, and embedded categories are applied to the dataset. For instance: - Filter Methods: Algorithms like ReliefF or Chi-square test are used to rank all features based on statistical measures [21]. - Wrapper Methods: Algorithms such as Genetic Algorithm (GA) or Binary Particle Swarm Optimization (BPSO) search for the optimal feature subset by repeatedly training and evaluating a model's performance (e.g., using accuracy or F1-score) [21]. - Embedded Methods: Algorithms like L1-norm regularization (Lasso) or Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) are implemented, which perform feature selection as an integral part of the model training process [21].

4. Model Training and Performance Evaluation: A predictive model (e.g., Random Forest) is trained using the feature subset selected by each method. The model's performance is then rigorously evaluated using a hold-out test set or cross-validation, with metrics such as Area Under the Curve (AUC), Accuracy (ACC), Recall (REC), and F1 Score (FS) [21].

5. Comparative Analysis: The performance metrics and computational efficiency of all models are compared to determine the relative effectiveness of the different feature selection approaches [15] [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Algorithms

Table 4: Key Algorithms and Evaluation Metrics for Feature Selection Research

| Category | Item | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Filter Algorithms | ReliefF, Chi-square Test, Correlation-based Feature Selection (CFS), Laplacian Score, Mutual Information | Ranks features based on statistical scores like correlation with the target or variance, independent of a classifier [21] [17]. |

| Wrapper Algorithms | Sequential Forward Selection (SFS), Genetic Algorithm (GA), Binary Particle Swarm Optimization (BPSO), Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) | Finds an optimal feature subset by iteratively training a model and evaluating its performance [15] [21] [16]. |

| Embedded Algorithms | Lasso (L1-norm), LassoNet, Random Forest Feature Importance, Ridge (L2-norm) | Integrates feature selection into the model training process, often via regularization, to learn feature importance [15] [20] [18]. |

| Evaluation Metrics | F1-Score, Area Under the Curve (AUC), Accuracy (ACC), Recall (REC), Computational Time | Quantifies the predictive performance of the model trained on the selected features and the efficiency of the selection process [15] [21] [9]. |

| Predictive Models | Random Forest (RF), Support Vector Machine (SVM), Logistic Regression (LR) | Serves as the target classifier for wrapper methods or for final evaluation after feature selection [21] [22]. |

The comparative analysis of filter, wrapper, and embedded feature selection methods reveals a consistent trade-off between computational efficiency and predictive performance. Filter methods offer speed and simplicity, making them suitable for initial data exploration and high-dimensional datasets. Wrapper methods, while computationally intensive, often yield superior accuracy by leveraging specific model feedback, ideal for scenarios where performance is critical and resources permit. Embedded methods strike a practical balance, efficiently producing performant feature sets as part of the model training process. The choice of method is not universal but should be guided by the specific dataset, computational constraints, and the ultimate goal of the research. As evidenced by experimental data, the wrapper method frequently achieves the highest accuracy, though the optimal approach is ultimately context-dependent [15] [21].

The journey of a drug from concept to clinic is fraught with challenges, predominantly due to the immense complexity of biological systems. Modern technologies generate unprecedented volumes of high-dimensional data, from genomic sequences to high-throughput screening results. This wealth of information, while valuable, presents a significant analytical hurdle known as the curse of dimensionality. Feature selection—the process of identifying the most relevant variables in a dataset—has emerged as a critical computational technique to overcome this obstacle, directly impacting the efficiency, cost, and success rate of pharmaceutical research and development [23] [24].

In drug development, feature selection is not merely a data preprocessing step but a fundamental component of building predictive and interpretable models. It enhances model performance, reduces overfitting, and decreases computational costs. More importantly, it helps researchers identify the most biologically significant factors, such as true predictive biomarkers or critical molecular descriptors, from thousands of candidates [8] [25]. This review provides a comparative analysis of feature selection methodologies, focusing on the ongoing research debate between filter and wrapper approaches, supported by experimental data from recent studies in biomarker discovery, toxicity prediction, and clinical outcome modeling.

Understanding Feature Selection Methodologies

Feature selection algorithms are broadly categorized into three classes: filter, wrapper, and embedded methods. Each possesses distinct mechanisms, advantages, and limitations, making them suitable for different scenarios in the drug development pipeline [26] [8].

Filter Methods

Filter methods assess the relevance of features based on intrinsic data properties, independently of any machine learning algorithm. They rely on statistical measures to evaluate the relationship between each feature and the target variable.

- Mechanism: These methods rank features using univariate metrics, selecting the top-ranked features for model building. Common criteria include correlation coefficients, chi-square tests, mutual information, and Fisher scores [26] [27].

- Advantages: Their primary strength is computational efficiency, making them suitable for high-dimensional datasets with thousands of features, a common scenario in genomics and cheminformatics. They are also model-agnostic and straightforward to implement [8] [27].

- Limitations: A key drawback is that they evaluate features in isolation, potentially ignoring feature interactions and dependencies that could be critical for prediction. They may also select redundant features that are highly correlated with each other [26] [25].

Wrapper Methods

Wrapper methods evaluate feature subsets by using a specific machine learning model's performance as the selection criterion. They search through the space of possible feature combinations to find the subset that yields the best predictive accuracy.

- Mechanism: These are "greedy" algorithms that iteratively select or remove features based on the model's performance (e.g., accuracy, F-measure). Common techniques include Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE), sequential feature selection, and genetic algorithms [26] [8].

- Advantages: They typically produce higher-performing models for the specific classifier used because they account for feature interdependencies and the model's bias [28] [25].

- Limitations: The primary disadvantage is high computational cost, as the model must be trained and validated repeatedly for different feature subsets. This makes them less practical for datasets with an extremely large number of features. They also carry a higher risk of overfitting [26] [8].

Embedded Methods

Embedded methods integrate the feature selection process directly into the model training algorithm. They combine the efficiency of filter methods and the performance of wrapper methods.

- Mechanism: Feature selection is performed as an inherent part of the model building process. Examples include L1 (LASSO) regularization, which adds a penalty term to the cost function to drive less important feature coefficients to zero, and decision tree-based algorithms that assign importance scores to features [26] [8].

- Advantages: They are computationally efficient and model-specific, leading to robust feature sets tailored to the learning algorithm [26].

- Limitations: The selected features are specific to the underlying model and may not be optimal for other algorithms. They can also be less interpretable than filter methods [8].

The following diagram illustrates the operational workflow and fundamental differences between these three categories.

Comparative Analysis: Filter vs. Wrapper Methods in Experimental Settings

The debate between filter and wrapper approaches is central to feature selection research. The following table provides a structured comparison based on key criteria relevant to drug development applications.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Filter and Wrapper Feature Selection Methods

| Criterion | Filter Methods | Wrapper Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Selects features based on statistical scores and intrinsic data properties [26]. | Selects features based on the performance of a specific predictive model [26]. |

| Computational Cost | Low; fast and efficient, ideal for very high-dimensional data [8] [27]. | High; requires repeated model training and validation, slower on large datasets [26] [8]. |

| Risk of Overfitting | Lower, as the process is independent of the classifier. | Higher, as features are fine-tuned to a specific model and dataset [8]. |

| Consideration of Feature Interactions | No; treats features as independent, which is a major limitation [26] [25]. | Yes; accounts for dependencies between features, a key strength [28] [25]. |

| Model Specificity | Model-agnostic; the selected feature set is generalizable to any algorithm. | Model-specific; the optimal feature subset is tied to the classifier used for selection. |

| Primary Applications in Drug Development | Initial screening of omics data (genomics, transcriptomics), large-scale molecular descriptor filtering [24]. | Biomarker signature refinement, toxicity prediction, clinical outcome models with curated feature sets [28] [25]. |

Experimental Evidence from Handwritten Character Recognition

A 2023 study directly comparing filter and wrapper approaches provides insightful empirical evidence. The research, though in a different domain, offers a robust controlled comparison. The key finding was that both filter and wrapper methods achieved similar classification accuracies. However, the filter approach accomplished this using fewer features and at a significantly lower computational cost [27]. This supports the use of filter methods as an efficient first-pass technique, especially when dealing with vast initial feature spaces.

Feature Selection in Action: Key Applications in Drug Development

Biomarker Discovery for Precision Oncology

The identification of robust predictive biomarkers is a cornerstone of precision oncology. Feature selection is crucial for distilling complex molecular profiling data into actionable biomarker signatures.

A 2025 study introduced MarkerPredict, a machine learning framework designed to predict clinically relevant biomarkers. The tool integrates network topology data and protein disorder information. It employs Random Forest and XGBoost (embedded methods) to classify potential biomarker-target pairs. In leave-one-out cross-validation (LOOCV), the models achieved an impressive accuracy ranging from 0.7 to 0.96, identifying 2084 potential predictive biomarkers for targeted cancer therapies [29]. This demonstrates how advanced feature selection integrated within ML models can systematically prioritize biomarkers for experimental validation.

Toxicity Prediction using QSAR Models

Predicting the toxicity of drug candidates is a critical step in development. Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models use molecular descriptors to predict biological activity, but often suffer from high dimensionality and imbalanced data.

A 2025 study addressed this by proposing a Binary Ant Colony Optimization (BACO) algorithm, a wrapper-type method. The algorithm was tested on 12 Tox21 challenge datasets. Its fitness function was designed to handle imbalanced data by maximizing a combination of F-measure, G-mean, and MCC (Matthews Correlation Coefficient). The results demonstrated that BACO significantly outperformed traditional filter methods (chi-square test, Gini index, mRMR). Notably, for one dataset (DS1), BACO using only 20 high-frequency features improved the F-measure from 0.5519 to 0.6029 and the AUC from 0.7128 to 0.7657 compared to using all 672 initial descriptors [25]. This highlights the superior performance of sophisticated wrapper methods in challenging prediction scenarios with complex, imbalanced data.

Table 2: Performance of BACO Feature Selection on Tox21 Datasets [25]

| Dataset | Number of Initial Descriptors | Performance with All Features (F-Measure) | Performance with BACO-Selected Features (F-Measure) | Number of Selected Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DS1 | 672 | 0.5519 | 0.6029 | 20 |

| DS2 | 669 | 0.5732 | 0.6168 | 20 |

| DS3 | 672 | 0.0898 | 0.2334 | 20 |

| DS4 | 671 | 0.0000 | 0.0570 | 20 |

Cancer Detection with Hybrid and Stacked Approaches

Some of the most promising results come from hybrid methodologies that combine the strengths of multiple feature selection paradigms.

A 2025 study on cancer detection proposed a 3-layer Hybrid Filter-Wrapper strategy for feature selection, combined with a stacked generalization model. The hybrid method first applied a greedy filter-based step to find features highly correlated with the class but not among themselves. A second, wrapper-based step used a best-first search with a logistic regression model to refine the subset. The final model, which used Logistic Regression, Naïve Bayes, and Decision Trees as base classifiers and a Multilayer Perceptron as a meta-classifier, achieved 100% accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and AUC on benchmark breast and lung cancer datasets using only a small subset of optimal features [28]. This breakthrough illustrates that a synergistic approach, rather than relying on a single method, can yield exceptional results.

The workflow of this successful hybrid approach is detailed below.

Drug Response Prediction

Predicting how a patient will respond to a drug is a primary goal of translational research. A 2024 comparative evaluation of nine feature reduction methods for drug response prediction (DRP) analyzed both knowledge-based and data-driven approaches. The study found that transcription factor (TF) activities, a knowledge-based feature transformation method, outperformed other methods. TF activities effectively distinguished between sensitive and resistant tumors for 7 out of 20 drugs evaluated. The study concluded that knowledge-based methods like this not only aid in prediction but also improve the interpretability of the models, which is crucial for generating testable biological hypotheses [24].

The experimental protocols cited in this review rely on several key public databases and computational tools that form the foundation of modern, data-driven drug development.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Resources for Feature Selection in Drug Development

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tox21 Database [25] | Public Dataset | Provides high-throughput screening data for toxicity testing of ~10,000 compounds across 12 nuclear receptor signaling pathways. | Used for training and validating QSAR models for molecular toxicity prediction. |

| Modred Descriptor Calculator [25] | Computational Tool | Calculates quantitative molecular descriptors from SMILES representations of chemical structures. | Converts chemical structures into a numerical feature set for machine learning models. |

| CIViCmine Database [29] | Literature-Mined Database | A text-mined resource of clinical evidence for cancer biomarkers, categorizing them as predictive, prognostic, or diagnostic. | Used as a knowledge base for training and validating biomarker discovery models like MarkerPredict. |

| DisProt / IUPred [29] | Protein Database & Tool | Databases and tools for identifying Intrinsically Disordered Proteins (IDPs) and regions, which are enriched in cancer biomarkers. | Used to incorporate protein disorder as a feature in predictive models of biomarker potential. |

| SciBERT / BioBERT [30] | Natural Language Processing (NLP) Model | Pre-trained models designed to understand and extract information from scientific and biomedical text. | Used for mining scientific literature to discover novel drug-disease relationships and biomarkers. |

The empirical evidence demonstrates that the choice between filter and wrapper feature selection methods is not about finding a universal winner, but about selecting the right tool for the specific stage and goal of a drug development project. Filter methods offer a scalable and efficient solution for the initial analysis of massively high-dimensional data, such as genome-wide screens or large chemical libraries. In contrast, wrapper and embedded methods provide a powerful, albeit more computationally demanding, approach for refining biomarker signatures and building highly accurate predictive models for toxicity or patient response, particularly when dealing with imbalanced data.

The most promising future direction lies in hybrid methodologies that strategically combine the scalability of filter methods with the precision of wrapper methods. As demonstrated by research achieving 100% accuracy in cancer detection, this synergistic approach can leverage the strengths of each paradigm while mitigating their weaknesses [28]. Furthermore, the integration of knowledge-based feature selection, which incorporates existing biological understanding from resources like pathway databases and protein interaction networks, will be crucial for developing models that are not only predictive but also interpretable and translatable into clinical insights [24] [29]. As drug development continues to embrace AI, sophisticated feature selection will remain a cornerstone for transforming complex biological data into actionable knowledge that accelerates the delivery of safe and effective therapies.

A Deep Dive into Filter and Wrapper Methods: Algorithms and Use Cases

In the comparative study of feature selection methods, filter methods represent a foundational approach characterized by their simplicity, computational efficiency, and model independence. These methods perform feature evaluation as a preprocessing step, selecting subsets of features based on their inherent statistical characteristics in relation to the target variable, without involving any machine learning algorithm [8] [31]. The core principle underlying filter methods is the scoring of each feature using a specific statistical measure, with features subsequently ranked and selected according to their scores, typically by retaining those exceeding a threshold or the top k-ranked features [8] [32].

The position of filter methods within the broader taxonomy of feature selection techniques is clearly established alongside wrapper and embedded methods. This taxonomy is defined by the interaction between the feature selection mechanism and model building [8] [33]. Wrapper methods employ a specific machine learning algorithm and evaluate feature subsets through a search process, using the model's performance as the selection criterion [8] [34]. While this often yields high-performing feature sets, the process is computationally intensive and carries a risk of overfitting [8]. Embedded methods integrate feature selection directly into the model training process, offering a balanced compromise between filter and wrapper approaches [8] [15] [34]. Filter methods remain distinct for their operation independent of any model, relying solely on statistical measures to assess feature relevance [32] [31].

In specialized domains such as drug development, filter methods provide significant practical advantages. Their computational efficiency makes them particularly suitable for the high-dimensional molecular data prevalent in the field, such as genome-wide gene expression profiles which may contain tens of thousands of features [11] [35]. Furthermore, the model independence of filter methods enhances the interpretability of results—a critical consideration for researchers and scientists who must understand and validate the biological relevance of selected features in experimental protocols [11] [35].

Core Statistical Measures for Feature Evaluation

The effectiveness of filter methods hinges on the appropriate selection of statistical measures used to evaluate the relationship between input features and the target variable. The choice of measure is primarily dictated by the data types of the variables involved, with different measures optimized for different combinations of numerical and categorical data [31].

Statistical Measures by Data Type

Table 1: Statistical Measures for Filter-Based Feature Selection

| Input Variable Type | Output Variable Type | Statistical Measure | Relationship Type Captured | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Numerical | Numerical | Pearson's Correlation Coefficient | Linear | Regression predictive modeling |

| Numerical | Numerical | Spearman's Rank Coefficient | Nonlinear | Regression with monotonic relationships |

| Numerical | Categorical | ANOVA Correlation Coefficient | Linear | Classification predictive modeling |

| Numerical | Categorical | Kendall's Rank Coefficient | Nonlinear | Classification with ordinal targets |

| Categorical | Categorical | Chi-Squared Test | General association | Classification with categorical features |

| Categorical | Categorical | Mutual Information | General dependence | Classification, agnostic to data type |

For problems involving numerical input and numerical output (regression problems), Pearson's correlation coefficient serves as the most common measure for assessing linear relationships between features and target [32] [31]. This measure calculates the covariance between two variables divided by the product of their standard deviations, producing a value between -1 and 1 that indicates the strength and direction of their linear relationship. For nonlinear relationships, Spearman's rank correlation coefficient serves as a robust alternative that measures monotonic associations without assuming linearity [31].

In scenarios with numerical input and categorical output (classification problems), the ANOVA correlation coefficient (F-test) evaluates whether the means of different groups (defined by the categorical target) are significantly different [31]. This determines if a numerical feature has statistically distinct distributions across various classes. Kendall's rank coefficient offers a nonparametric alternative suitable for ordinal categorical targets [31].

For categorical input and categorical output, the chi-squared test assesses the independence between two categorical variables by comparing observed frequencies with expected frequencies under the independence assumption [31]. Mutual information, derived from information theory, measures the reduction in uncertainty about one variable given knowledge of another, making it particularly powerful for detecting both linear and nonlinear relationships [5] [31]. Mutual information is considered agnostic to data types and can be adapted for use with various variable type combinations [31].

Practical Implementation of Statistical Measures

The practical application of these statistical measures in research environments is facilitated by comprehensive programming libraries. The scikit-learn library in Python provides dedicated implementations for many of these measures, including f_regression() for Pearson's correlation, f_classif() for ANOVA, chi2() for chi-squared tests, and mutual_info_classif() along with mutual_info_regression() for mutual information [31]. Additionally, the SciPy library offers implementations of specialized statistics such as kendalltau for Kendall's tau and spearmanr for Spearman's rank correlation [31].

Once statistical scores are calculated for each feature, selection mechanisms filter features based on these scores. The SelectKBest method retains the top k highest-scoring features, while SelectPercentile selects the top percentile of features [31]. These filtering approaches provide researchers with flexible frameworks for dimensionality reduction tailored to specific analytical needs.

Comparative Analysis: Filter vs. Wrapper Methods

Performance Metrics Across Domains

Empirical evaluations across diverse domains provide critical insights into the relative performance characteristics of filter and wrapper methods. The following table synthesizes quantitative findings from multiple comparative studies, highlighting the context-specific tradeoffs between these approaches.

Table 2: Experimental Comparison of Filter and Wrapper Methods Across Applications

| Application Domain | Filter Method Performance | Wrapper Method Performance | Key Findings | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Encrypted Video Traffic Classification | Moderate accuracy with low computational overhead | Higher accuracy with significantly longer processing times | Embedded methods provided a balanced compromise | [15] |

| Speech Emotion Recognition | Mutual Information: 64.71% accuracy with 120 features | Recursive Feature Elimination: Performance improved with more features, stabilizing around 120 | Filter methods achieved highest performance with selected feature subsets | [5] |

| Seismic Damage Assessment | Effective for initial feature screening | Optimal feature subsets with enhanced accuracy but higher computational demands | Wrapper methods better captured complex feature interactions for structural assessment | [33] |

| Drug Response Prediction | Knowledge-based filters using biological insights yielded highly interpretable models | Data-driven wrapper approaches required more features and samples | Biologically-driven filters performed well for drugs targeting specific pathways | [35] |

Methodological Workflows in Experimental Protocols

The comparative evaluation of filter and wrapper methods follows distinct methodological workflows, each with characteristic strengths and limitations. Understanding these experimental protocols is essential for researchers designing feature selection strategies for drug development applications.

The filter method workflow initiates with statistical evaluation, where each feature is independently scored based on its relationship with the target variable using appropriate statistical measures [33] [31]. Features are then ranked according to their scores, and a subset is selected based on predefined criteria (e.g., top k features or threshold exceeding) [32]. This selected feature subset subsequently serves as input to machine learning models, with model performance providing the final evaluation metric [33]. This sequential process, while efficient, operates without direct feedback from the model regarding feature utility.

In contrast, wrapper methods employ an iterative, model-guided workflow. The process begins with the selection of a feature subset, followed by model training using this subset [8] [34]. Model performance is then evaluated on a validation set, and this performance metric directly informs the subsequent feature subset selection [33]. This cycle of feature subset selection, model training, and performance evaluation continues until a stopping criterion is satisfied (e.g., performance plateaus or maximum iterations reached) [8]. While computationally intensive, this approach explicitly optimizes feature selection for the specific model employed.

Diagram 1: Workflow comparison between filter and wrapper feature selection methods. Filter methods use a sequential process, while wrapper methods employ an iterative, model-guided approach.

Trade-off Analysis for Research Applications

The comparative evidence reveals a consistent trade-off between computational efficiency and predictive performance across domains. Filter methods demonstrate significant advantages in processing speed, making them particularly suitable for preliminary feature screening in high-dimensional datasets [8] [15]. Their model independence offers additional flexibility, allowing the same feature subset to be evaluated with multiple algorithms without reselection [32]. Furthermore, the statistical foundation of filter methods enhances interpretability, as feature selection relies on established statistical measures rather than model-specific metrics [35].

Wrapper methods consistently achieve superior predictive accuracy in multiple comparative studies, effectively capturing feature interactions and complex relationships that univariate filter methods might miss [15] [33]. This performance advantage comes at substantial computational cost, with processing times significantly longer than those required by filter methods [15]. Additionally, the feature subsets selected by wrapper methods are optimized for specific algorithms, potentially limiting their transferability across different modeling approaches [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Feature Selection Implementation

| Research Reagent | Function | Implementation Examples | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scikit-learn Feature Selection Module | Provides statistical measures and selection algorithms | SelectKBest, SelectPercentile, f_classif, chi2 |

General-purpose feature selection in Python |

| SciPy Statistical Functions | Advanced statistical testing | spearmanr, kendalltau, pearsonr |

Specialized correlation analysis |

| Variance Threshold | Removes low-variance features | VarianceThreshold from scikit-learn |

Preliminary filtering of uninformative features |

| Mutual Information Estimators | Measures dependency between variables | mutual_info_classif, mutual_info_regression |

Nonlinear relationship detection |

| Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) | Wrapper method implementation | RFE from scikit-learn |

Comparative evaluation with filter methods |

| Biological Pathway Databases | Knowledge-based feature selection | Drug target pathways, Reactome, OncoKB | Drug response prediction with biological context |

The comparative analysis of filter and wrapper feature selection methods reveals a nuanced landscape where methodological choice significantly impacts research outcomes. Filter methods, with their statistical foundation and computational efficiency, provide robust solutions for initial feature screening, high-dimensional data scenarios, and research contexts requiring interpretability. Wrapper methods, despite their computational demands, deliver enhanced predictive performance for mission-critical applications where accuracy outweighs efficiency concerns. For drug development professionals and researchers, the optimal approach depends on specific research objectives, dataset characteristics, and computational resources, with hybrid strategies often providing the most practical solution for complex analytical challenges.

Feature selection is a critical step in the machine learning pipeline, directly impacting model performance, interpretability, and computational efficiency. Within the broader comparative study of filter versus wrapper feature selection methods, wrapper methods distinguish themselves by evaluating feature subsets based on their actual performance with a specific learning algorithm [16] [26]. This guide provides a detailed comparative analysis of three fundamental wrapper methods: Sequential Selection, Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE), and Genetic Algorithms.

Unlike filter methods that assess features based on intrinsic characteristics like variance or correlation, wrapper methods treat the model as a "black box" and use its performance as the objective function to guide the search for an optimal feature subset [16] [26]. While this approach is computationally more intensive, it often yields feature sets that deliver superior predictive performance, particularly when accounting for complex feature interactions [16] [9].

This article objectively compares these three key wrapper methodologies, providing experimental data, detailed protocols from cited studies, and practical implementation guidance tailored for researchers and drug development professionals working with high-dimensional biological data.

Core Methodologies and Comparative Mechanics

Sequential Feature Selection

Sequential Feature Selection (SFS) operates through a greedy search algorithm that iteratively builds the feature subset. Sequential Forward Selection (SFS) begins with an empty set and adds the most performance-improving feature each iteration. Conversely, Sequential Backward Selection (SBS) starts with all features and removes the least significant one at each step [16] [26]. The process continues until adding or removing features no longer significantly improves model performance or a predefined number of features is reached.

Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE)

Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) employs a backward elimination strategy. It starts by training a model on all features, ranking them based on a defined importance measure (e.g., coefficients for linear models, featureimportances for tree-based models), and recursively pruning the least important features [16] [36]. After each elimination round, the model is retrained with the remaining features, refining the importance rankings until the desired feature subset size is achieved.

Genetic Algorithms

Genetic Algorithms (GAs) for feature selection are inspired by natural evolution. A population of candidate feature subsets is represented as binary chromosomes (where '1' indicates feature inclusion and '0' exclusion). This population evolves over generations through selection (favoring subsets with higher model performance), crossover (combining parts of different subsets), and mutation (randomly flipping inclusion bits) [37]. This stochastic global search makes GAs particularly effective for avoiding local optima in complex feature spaces.

Direct Comparison of Mechanisms

The table below summarizes the core operational differences between these three wrapper methods.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Wrapper Methods

| Characteristic | Sequential Selection | Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) | Genetic Algorithms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Search Type | Greedy, Local | Greedy, Local | Stochastic, Global |

| Primary Direction | Forward (SFS) or Backward (SBS) | Backward | Non-directional / Evolutionary |

| Feature Interaction Handling | Limited | Moderate | Strong |

| Computational Cost | Moderate | Moderate to High | High |

| Risk of Local Optima | High | High | Low |

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental workflow common to all wrapper methods, highlighting the core iterative process of subset generation, model training, and performance evaluation.

Figure 1: Core Wrapper Method Workflow. This iterative process of subset generation, model training, and performance evaluation is fundamental to all wrapper methods.

Performance Analysis and Experimental Data

Quantitative Performance Benchmarks

Recent research across various domains provides empirical evidence of the performance characteristics of these wrapper methods. The table below summarizes key findings.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Comparison of Wrapper Methods

| Method | Dataset | Key Results | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequential Forward Selection (SFS) | 18 Diverse Datasets | Average classification accuracy of 89.81% (KNN), 87.55% (SVM), and 89.82% (RF) achieved in a two-stage wrapper method. | [22] |

| RFE with Bootstrap (PFBS-RFS-RFE) | RNA Gene & Dermatology Diseases | Enhanced accuracy to 99.994% and 100.000%, respectively, addressing over-fitting and computation time. | [36] |

| Genetic Algorithm with ELM (GAELMSFS) | IoT_ToN & UNSW-NB15 (IDS) | Achieved 99% and 86% accuracy, respectively, demonstrating effectiveness in high-dimensional feature reduction. | [37] |

| AIWrap (AI-Powered Wrapper) | Simulated & Real Biological Data | Showed better or on-par performance with standard penalized and wrapper algorithms, leveraging a performance prediction model. | [38] |

Analysis of Performance Trade-offs

The experimental data reveals a clear trade-off between predictive performance and computational cost. While advanced methods like bootstrap-enhanced RFE and GA-ELM can achieve exceptional accuracy, they require significantly more computational resources [36] [37].

Sequential methods often provide a compelling balance, offering substantial performance improvements over filter methods with moderate computational demands [22]. The choice of the underlying estimator (e.g., Logistic Regression, Random Forest, SVM) also significantly influences the final performance and the selected feature subset, underscoring the model-specific nature of wrapper methods [16] [22].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Recursive Feature Elimination with Bootstrap

This protocol is based on the PFBS-RFS-RFE method, which enhanced cancer classification performance [36].

1. Problem Definition: High-dimensional data problems, such as gene expression data with thousands of features and limited samples, lead to over-fitting and long computation times.

2. Method Steps:

- Step 1: Apply Bootstrap Resampling. Use one of three positions: Outer First Bootstrap Step (OFBS), Inner First Bootstrap Step (IFBS), or a hybrid Outer/Inner First Bootstrap Step (O/IFBS).

- Step 2: Feature Importance with Random Forest. Use Random Forest for Selection (RFS) to calculate feature importance. With OFBS, bootstrap is applied before RFS; with IFBS, bootstrap is integrated during RFS.

- Step 3: Hybrid RFE. The importance features from RFS are hybridized with Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE). RFE uses Logistic Regression (LR) as its estimator to recursively remove the weakest features.

- Step 4: Model Evaluation. The final subset of selected features is evaluated using metrics like accuracy, variance, and ROC area on independent test sets.

3. Outcome: This protocol successfully addressed over-fitting and high computational time on RNA gene and dermatology datasets, achieving near-perfect accuracy and ROC area [36].

Protocol 2: Genetic Algorithm with Extreme Learning Machine

This protocol outlines the GA-ELM method proposed for intrusion detection, a approach applicable to high-dimensional IoT data [37].

1. Problem Definition: Intrusion Detection Systems (IDS) trained on high-dimensional IoT data suffer from redundant features, which reduce detection accuracy and computational efficiency.

2. Method Steps:

- Step 1: Optimize ELM using GA. The input weights and biases of the Extreme Learning Machine (ELM) are optimized using a Genetic Algorithm (GA). The GA evolves a population of potential weight vectors, using the ELM's performance as the fitness function.

- Step 2: Sequential Forward Selection with Optimized ELM. The optimized ELM (GA-ELM) is used as the estimator within a Sequential Forward Selection (SFS) wrapper. SFS iteratively adds features that most improve the GA-ELM's performance.

- Step 3: Final Classification. The feature subset selected by GA-ELM-SFS is used to train a final Support Vector Machine (SVM) classifier for intrusion detection.

3. Outcome: The model achieved 99% accuracy on the IoT_ToN dataset and 86% on the UNSW-NB15 dataset, demonstrating robust feature reduction and classification performance [37].

The following workflow diagram visualizes the key stages of the GA-ELM protocol, illustrating the integration of evolutionary optimization with sequential feature selection.

Figure 2: GA-ELM-SFS Experimental Workflow. This protocol integrates evolutionary optimization with sequential feature selection.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Implementing wrapper methods effectively requires a combination of software tools, libraries, and computational resources. The following table details key "research reagents" for the modern data scientist.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Implementing Wrapper Methods

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| scikit-learn (Python) | Software Library | Provides ready implementations of RFE, SequentialFeatureSelector (SFS), and various estimators (LogisticRegression, RandomForest). | Rapid prototyping and benchmarking of wrapper methods on genomic data [16]. |

| TPOT (Python) | Automated ML Tool | Uses genetic programming to automate feature selection, model selection, and hyperparameter tuning. | Automating the search for an optimal feature pipeline with minimal manual intervention. |

| Custom GA Framework | Software Script | A custom-coded genetic algorithm for feature selection, allowing maximum flexibility in fitness functions and evolutionary operations. | Tailoring feature selection for specialized domains or integrating novel fitness metrics [37]. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Computational Resource | Provides the parallel processing power needed for computationally intensive wrapper methods, especially GAs and RFE with large feature sets. | Running multiple model training iterations in parallel to reduce the wall-clock time for feature selection [38]. |