External Validation of Cancer Risk Prediction Algorithms: A Foundational Guide for Biomedical Research and Clinical Translation

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the critical role of external validation in the development and implementation of cancer risk prediction algorithms.

External Validation of Cancer Risk Prediction Algorithms: A Foundational Guide for Biomedical Research and Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the critical role of external validation in the development and implementation of cancer risk prediction algorithms. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of external validation, contrasting it with internal validation. The scope covers methodological frameworks for conducting rigorous external validation, addresses common challenges and optimization strategies such as handling overfitting and incorporating novel biomarkers, and presents a comparative analysis of model performance across different validation studies. By synthesizing recent evidence and methodological standards, this article serves as a guide for evaluating the generalizability, robustness, and clinical readiness of predictive models in oncology.

The Critical Role of External Validation in Cancer Risk Prediction

Defining External vs. Internal Validation in Statistical Modeling

In the field of cancer research, statistical prediction models are powerful tools for estimating disease risk, prognosis, and treatment outcomes. However, their reliability depends critically on rigorous validation—the process of evaluating a model's performance on independent data. This guide examines the fundamental distinction between internal and external validation, two sequential processes essential for establishing model credibility. Through comparative analysis of methodologies, performance metrics, and case studies from contemporary oncology research, we provide researchers with a framework for developing robust, clinically applicable prediction models.

Cancer prediction algorithms have emerged as indispensable tools for improving early diagnosis, prognostic stratification, and treatment selection. These mathematical models combine multiple patient-specific variables—including demographic characteristics, clinical symptoms, laboratory results, and imaging features—to generate individualized risk estimates [1]. However, a model's performance in the development dataset often provides an overly optimistic estimate of its real-world accuracy—a phenomenon known as overfitting [2]. Validation methodologies serve as critical safeguards against this optimism bias, separating clinically viable models from those that fail to generalize beyond their original development context.

The validation process is typically conducted in two sequential phases: internal validation, which assesses model stability and optimizes parameters within the original dataset, and external validation, which evaluates model transportability to new patient populations [3]. Understanding the distinction between these processes is fundamental for researchers developing prediction tools and clinicians interpreting their potential clinical utility. This guide examines the methodological frameworks, implementation protocols, and performance interpretation for both validation types within the context of cancer research.

Core Concepts and Definitions

Internal Validation

Internal validation assesses the reproducibility of a prediction model within the same dataset used for its development, providing an initial estimate of potential overfitting [3]. This process uses resampling techniques to evaluate how the model would perform on hypothetical new data drawn from the same underlying population. Internal validation represents a necessary first step in model evaluation but does not guarantee performance in truly independent populations [4].

External Validation

External validation tests the original prediction model on entirely new patients collected separately from the development cohort [3]. This rigorous assessment determines whether the model maintains its predictive accuracy when applied to different geographic regions, healthcare settings, or temporal periods. External validation is a prerequisite for clinical implementation, as it establishes the model's generalizability beyond the specific context in which it was created [5].

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Validation Types

| Characteristic | Internal Validation | External Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Testing model performance within the original dataset using resampling methods | Testing the original model on completely independent data |

| Primary Purpose | Estimate and correct for overfitting; optimize model parameters | Assess model reproducibility and generalizability to new populations |

| Key Methods | Train-test split, cross-validation, bootstrapping | Geographic, temporal, or fully independent validation |

| Dataset Relationship | Derived from original development data | Structurally separate from development data |

| Performance Interpretation | Indicates model stability | Determines clinical applicability and transportability |

| Role in Implementation | Necessary development step | Prerequisite for clinical use |

Methodological Frameworks

Internal Validation Techniques

Internal validation employs several established methodologies to estimate model performance without collecting new data:

Split-sample validation randomly divides the available dataset into development and validation subsets, typically using a 70:30 ratio [6]. While conceptually simple, this approach is statistically inefficient, particularly in smaller datasets, as it reduces the sample size available for both model development and validation [3].

Cross-validation extends the split-sample approach by repeatedly partitioning the data. In k-fold cross-validation, the dataset is divided into k equally sized subsets (typically k=5 or k=10). The model is trained on k-1 folds and validated on the remaining fold, repeating this process until each fold has served as the validation set [4]. The performance estimates are then averaged across all iterations, providing a more robust assessment than single split-sample validation.

Bootstrapping creates multiple resampled datasets with replacement from the original data, each the same size as the original cohort. The model is developed on each bootstrap sample and tested on both the bootstrap sample and the original dataset [4]. The average difference between these performance estimates (the "optimism") is subtracted from the apparent performance to obtain a bias-corrected estimate.

Table 2: Internal Validation Methods in Cancer Prediction Models

| Method | Implementation | Advantages | Limitations | Cancer Research Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Split-sample | Random division into training/test sets (e.g., 70:30) | Simple implementation and interpretation | Statistically inefficient; high variance in small samples | Colorectal cancer risk model using PLCO trial data [6] |

| K-fold cross-validation | Data divided into k subsets; iterative training/validation | More stable than split-sample; uses all data | Computationally intensive; complex implementation | Transcriptomic prognosis model for head and neck cancer [4] |

| Bootstrap validation | Multiple resampled datasets with replacement | Most efficient use of available data | Can be over-optimistic or pessimistic without correction [4] | Myeloma risk prediction model [7] |

External Validation Approaches

External validation employs distinct strategies to assess model transportability:

Temporal validation tests the model on patients from the same institutions or geographic regions but treated during a later time period. This approach assesses whether the model remains accurate as clinical practices evolve [3].

Geographic validation evaluates the model on patients from different healthcare systems or regions. For instance, a model developed in the United Kingdom might be validated on patients from other European countries [1] [8]. This approach tests the model's robustness to variations in healthcare delivery, genetic backgrounds, and environmental factors.

Fully independent validation represents the most rigorous approach, where the model is tested by completely separate research teams using different data collection protocols [5] [9]. This method minimizes potential biases introduced by the original developers and provides the strongest evidence of generalizability.

Experimental Protocols and Performance Metrics

Standardized Validation Workflows

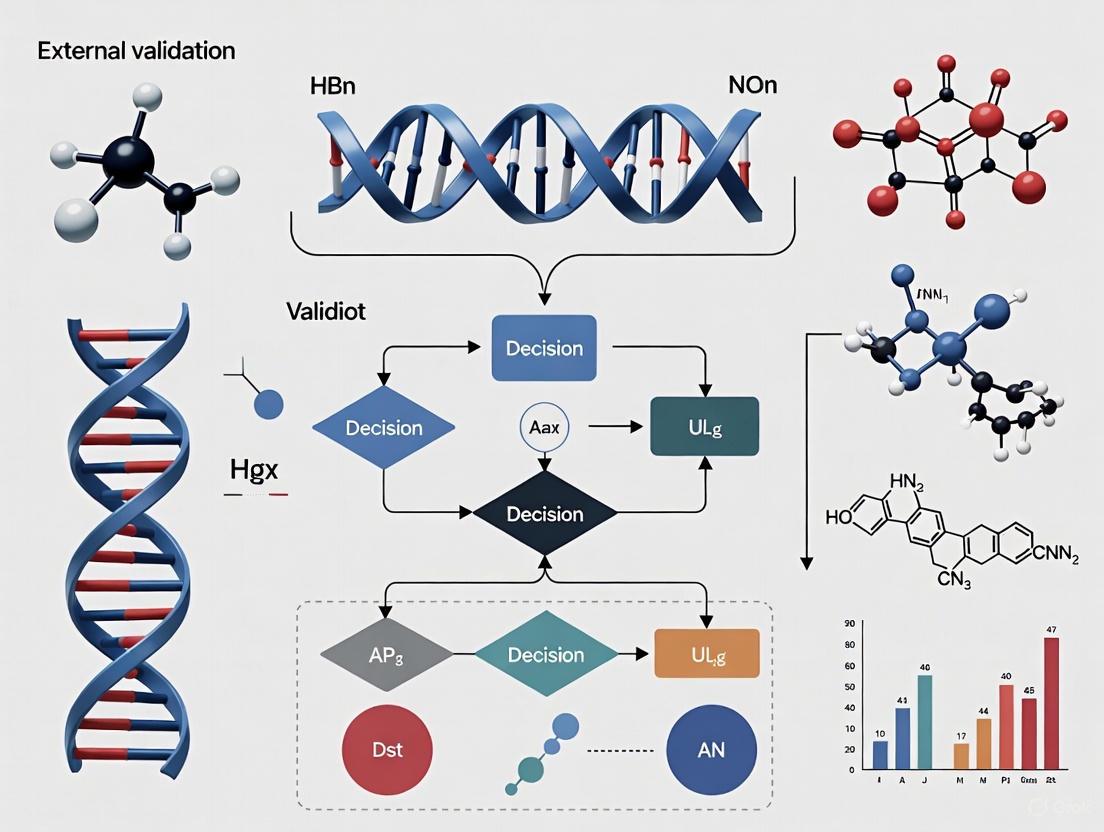

A systematic approach to validation ensures comprehensive assessment and reproducible results. The following workflow illustrates the sequential process of model development and validation:

Key Performance Metrics

Both internal and external validation employ standardized metrics to quantify predictive performance:

Discrimination measures how well a model distinguishes between patients who experience the outcome versus those who do not. The C-statistic (equivalent to the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve, AUC) is commonly used, with values ranging from 0.5 (no discrimination) to 1.0 (perfect discrimination) [1]. For example, a recent cancer prediction algorithm incorporating blood tests demonstrated C-statistics of 0.876 for men and 0.844 for women for any cancer diagnosis [1].

Calibration assesses the agreement between predicted probabilities and observed outcomes. Well-calibrated models generate predictions that match the actual event rates across different risk levels [10]. Calibration is typically visualized using calibration plots and quantified with statistics like the calibration slope, where a value of 1 indicates perfect calibration [1].

Clinical utility evaluates whether using the model improves decision-making compared to standard approaches. Decision curve analysis quantifies net benefit across different probability thresholds, balancing true positives against false positives [5].

Case Studies in Cancer Research

Comprehensive Cancer Prediction Algorithm

A 2025 study developed and validated algorithms to improve early cancer diagnosis using English primary care data from 7.46 million patients [1]. The researchers created two models: one with clinical factors and symptoms, and another incorporating routine blood tests. After internal validation, they performed rigorous external validation using two separate cohorts totaling over 5 million patients from across the UK. The externally validated models demonstrated excellent discrimination (C-statistic 0.876 for men, 0.844 for women) and maintained calibration across diverse populations, outperforming existing prediction tools [1].

External Validation of Breast Cancer Models

A 2023 study exemplifies the critical importance of external validation, evaluating 87 breast cancer prediction models using Dutch registry data from 271,040 patients [5]. The results revealed substantial performance variation: only 34 models (39%) performed well after external validation, 26 showed moderate performance, and 27 (31%) performed poorly despite previous promising development. This comprehensive validation effort prevented the implementation of potentially misleading models and identified robust tools suitable for Dutch clinical practice [5].

Machine Learning in Gastric Cancer Surgery

A 2024 study externally validated a machine learning model predicting 90-day mortality after gastrectomy for cancer [8]. The original model, developed from the Spanish EURECCA registry, achieved an AUC of 0.829. When applied to the international GASTRODATA registry (2,546 patients from 24 European hospitals), performance modestly decreased to an AUC of 0.716, yet maintained clinically useful discrimination. This performance attenuation in external validation is typical, highlighting how differences in patient populations, surgical techniques, and perioperative care can affect model transportability [8].

Table 3: Performance Metrics in Cancer Prediction Model Validations

| Study & Cancer Type | Development Performance | Internal Validation | External Validation | Key Insights |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-cancer early detection [1] | C-statistic: Not separately reported | C-statistic: 0.876 (M), 0.844 (F) with blood tests | Similar performance in 2.74M patients from Scotland, Wales, NI | Blood tests (FBC, liver function) significantly improved prediction |

| Breast cancer models [5] | Various performance in original studies | Not applicable | 34/87 (39%) performed well; 27/87 (31%) performed poorly | Comprehensive registry data enables broad validation of multiple models |

| Gastric cancer surgery [8] | AUC: 0.829 | Not separately reported | AUC: 0.716 in international cohort | Modest performance reduction common in external validation |

| Cervical cancer survival [10] | C-index: 0.882 | C-index: 0.885 | C-index: 0.872 in hospital data | Nomogram maintained performance across validation cohorts |

Statistical Software and Computing Environments

- R Statistical Software (version 4.3.2): Open-source environment with comprehensive packages for prediction modeling (

rms,glmnet,mlr3) and validation (rms,pROC) [10]. - Python with scikit-learn: Machine learning library providing implementations of cross-validation, bootstrapping, and performance metrics.

- mlr3 Package: Comprehensive machine learning framework for R facilitating internal and external validation of predictive models [8].

- Electronic Health Records: Large-scale primary care databases (e.g., QResearch, CPRD) containing linked primary care, hospital, and mortality data [1].

- Cancer Registries: Population-based registries (e.g., Netherlands Cancer Registry, SEER database) providing detailed clinical and outcome data [5] [10].

- International Consortia: Multi-center collaborations (e.g., GASTRODATA registry) enabling geographic validation across diverse healthcare systems [8].

Reporting Guidelines and Methodological Standards

- TRIPOD Statement (Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis Or Diagnosis): Comprehensive checklist ensuring complete reporting of prediction model development and validation studies [8].

- REMARK Guidelines (Reporting Recommendations for Tumor Marker Prognostic Studies): Specialized guidelines for reporting cancer prognostic studies [2].

Internal and external validation serve distinct but complementary roles in the development of cancer prediction models. Internal validation provides initial estimates of model stability and optimizes parameters, while external validation establishes generalizability to new populations—a prerequisite for clinical implementation. The case studies presented demonstrate that even models with excellent internal performance may show diminished accuracy when applied externally, underscoring the necessity of rigorous validation across diverse settings. As cancer research increasingly embraces artificial intelligence and complex machine learning algorithms, adherence to robust validation methodologies will be essential for translating statistical predictions into clinically actionable tools that improve patient outcomes.

Why External Validation is Non-Negotiable for Clinical Generalizability

In the pursuit of refining cancer care, clinicians and researchers increasingly rely on predictive algorithms to estimate everything from a patient's initial cancer risk to their likelihood of recurrence. However, a model's promising performance in the laboratory provides no guarantee of its effectiveness in the diverse and unpredictable environment of real-world clinical practice. External validation—the process of evaluating a prediction model in data that was not used for its development—serves as the critical bridge between theoretical development and trustworthy clinical application. It is the fundamental process that tests whether a model's predictions hold true for new populations, from different geographical regions or care settings, ensuring that the algorithms intended to guide patient care are both reliable and generalizable.

Defining the Validation Landscape: From Internal Checks to External Generalizability

Before a model can be deemed fit for widespread clinical use, it must pass through several stages of validation, each serving a distinct purpose. The journey begins with internal validation, which assesses a model's reproducibility within the same underlying population from which it was derived. Techniques like bootstrapping or cross-validation correct for over-optimism, providing a more realistic estimate of performance had the model been applied to similar, but new, patients from that same population [3] [11].

External validation moves beyond this, testing the model's transportability to entirely new settings. As outlined in the literature, this encompasses several key dimensions [11]:

- Temporal Validation: Assessing performance in patients from the same institution or region but from a later time period. This checks for "data drift," where relationships between variables and outcomes may evolve.

- Geographical Validation: Testing the model on data collected from a different location, such as a hospital in another country. This is crucial for establishing that the model works across diverse healthcare systems and patient demographics.

- Domain Validation: Evaluating whether the algorithm generalizes to a different clinical context, such as from a primary care population to a secondary care population, or from one specific cancer type to another.

Independent external validation, conducted by researchers not involved in the model's original development, is considered the gold standard, as it eliminates the potential for conscious or unconscious fine-tuning of the model to the validation data [3].

Comparative Performance: How Externally Validated Models Measure Up

The following table summarizes key performance metrics from recent, high-impact studies that have undertaken rigorous external validation of cancer prediction algorithms.

Table 1: Performance Metrics from Externally Validated Cancer Prediction Models

| Cancer Type / Focus | Model Description | Validation Type & Cohort Size | Key Performance Metrics | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple Cancers (15 types) | Algorithm incorporating symptoms, history, and blood tests (Model B) | Geographical validation on 2.74 million patients from Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland [1] | Any Cancer (Men): C-statistic = 0.876 (95% CI 0.874–0.878)Any Cancer (Women): C-statistic = 0.844 (95% CI 0.842–0.847) | [1] |

| Early-Stage Lung Cancer | Machine learning model using CT radiomics and clinical data | External validation on 252 patients from a separate medical center [9] | Superior risk stratification vs. TNM staging (HR for DFS: 3.34 vs. 1.98 in external cohort); correlated with pathologic risk factors (p < 0.05) | [9] |

| Bladder Cancer (Distant Metastasis) | Nomogram based on tumor size, N stage, and surgery | External validation on a cohort of 112 patients from a Chinese hospital [12] | AUC of 0.968 in the external validation cohort | [12] |

| AI in Oncology (Scoping Review) | Review of 56 externally validated ML models for clinical decision-making | Analysis of multi-institutional studies published 2018-2022 [13] | Found that most studies were retrospective; noted challenges with limited international ethnic diversity and inconsistent calibration reporting | [13] |

The data consistently shows that high-performing, externally validated models share common traits: they are often developed on very large datasets, validated across different populations, and demonstrate robust discrimination (as measured by C-statistics or AUC). The superior hazard ratios (HR) for disease-free survival in the lung cancer model, for instance, indicate its enhanced ability to stratify risk compared to the current clinical standard [9].

Experimental Protocols for Robust External Validation

A methodologically sound external validation study follows a structured protocol to ensure its findings are credible and actionable.

Table 2: Key Methodological Steps for External Validation Studies

| Protocol Step | Description | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Model Selection & Definition | Obtain the full prediction model formula, including all coefficients and intercepts. | Ensure the model is specified exactly as developed; any deviation invalidates the validation [3]. |

| 2. Validation Cohort Definition | Identify a cohort that is distinct from the development data. | The cohort should represent the target population for the model's intended use (e.g., different geography, time period) [11]. |

| 3. Predictor & Outcome Ascertainment | Extract or measure the predictor variables and outcome as defined in the original model. | Harmonization of variable definitions (e.g., smoking status, cancer stage) across datasets is critical [12]. |

| 4. Risk Calculation | Apply the original model's equation to calculate predicted risks for each individual in the validation cohort. | This step should be automated and reproducible [3]. |

| 5. Performance Assessment | Compare predicted risks to observed outcomes using discrimination, calibration, and clinical utility metrics. | Discrimination (e.g., C-statistic) measures how well the model separates patients with and without the outcome. Calibration (often with a plot) assesses the agreement between predicted probabilities and observed frequencies [1] [13]. |

| 6. Model Comparison & Updating | Compare performance to existing models or clinical standards. If performance is poor but transportable, consider model updating. | Updating might involve adjusting the model's intercept or re-estimating some coefficients for the new population [3]. |

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and key decision points in a rigorous external validation process.

Conducting robust validation studies requires access to specific data, tools, and methodologies. The table below details key resources frequently utilized in this field.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for External Validation Studies

| Tool / Resource | Type | Function in Validation | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Large Electronic Health Record (EHR) Databases (e.g., QResearch, CPRD) [1] [14] | Data Source | Provide large, representative, longitudinal patient data for model development and geographical/temporal validation. | Used to develop and validate a cancer prediction algorithm across 7.46 million patients [1]. |

| National Cancer Registries (e.g., SEER, NCRAS) [12] | Data Source | Offer high-quality, curated data on cancer incidence, stage, and outcomes for outcome ascertainment and validation. | Used as a primary data source for developing a nomogram for distant metastasis in bladder cancer [12]. |

| Statistical Software (e.g., R, Python with scikit-learn) | Analytical Tool | Used to calculate predicted risks, perform statistical tests, and generate performance metrics and plots (e.g., calibration curves). | Essential for all steps of the validation protocol, from risk calculation to performance assessment [3]. |

| TRIPOD/TRIPOD-AI Guidelines [11] | Reporting Framework | A checklist to ensure transparent and complete reporting of prediction model development and validation studies. | Improves the reproducibility and credibility of published validation research [11]. |

| Bioinformatics Tools (e.g., for radiomics or genomic analysis) [9] [12] | Analytical Tool | Extract and analyze high-dimensional features from medical images or genomic data for complex AI model validation. | Used to extract radiomic features from CT scans for a lung cancer recurrence prediction model [9]. |

The journey of a cancer prediction algorithm from a concept to a tool that can reliably inform patient care is fraught with potential for failure. External validation is the non-negotiable checkpoint that separates speculative tools from clinically credible ones. It provides the necessary evidence that an algorithm can perform adequately across different populations, times, and settings—the very definition of generalizability. For researchers, it is a mandatory step to combat research waste and build trust in their models. For clinicians, drug developers, and, most importantly, patients, it is the safeguard that ensures the decisions guided by these algorithms are based on reliable, evidence-based science.

The transition of a cancer risk prediction algorithm from a statistical model to a clinically useful tool hinges on rigorous validation against three core principles: discrimination, calibration, and clinical net benefit. Discrimination assesses a model's ability to separate patients with and without the outcome of interest, typically measured by the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC) or C-statistic. Calibration evaluates how well predicted probabilities match observed frequencies, often visualized via calibration plots. Clinical net benefit quantifies the model's utility in informing clinical decisions, balancing true positives against false positives across different probability thresholds using decision curve analysis (DCA) [15] [16].

These metrics are particularly crucial in oncology, where prediction models inform high-stakes decisions about screening, intervention, and treatment. A model with excellent discrimination may still be clinically useless if it is poorly calibrated, leading to overestimation or underestimation of risk for individual patients. Furthermore, a model must demonstrate that its use improves clinical decision-making compared to standard approaches, which is the essence of assessing clinical net benefit [15]. This guide objectively compares the performance of recently developed and validated cancer prediction models against these three fundamental criteria.

Performance Data Comparison of Cancer Prediction Models

Table 1: Discrimination and Calibration Performance of Recent Cancer Prediction Models

| Cancer Type / Context | Model Name/Type | Discrimination (AUC/C-statistic) | Calibration Assessment | Clinical Net Benefit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple Cancers (Diagnostic) | Model A (Symptoms + Clinical Factors) | Men: 0.876 (95% CI 0.874-0.878); Women: 0.844 (95% CI 0.842-0.847) [1] | Not explicitly reported in summary | Superior net benefit compared to existing scores [1] |

| Model B (Includes Blood Tests) | Improved over Model A, though confidence intervals overlapped [1] | Not explicitly reported in summary | Superior net benefit compared to existing scores [1] | |

| Melanoma (SLN Metastasis) | MIA Nomogram | 0.753 (95% CI 0.694-0.812) [16] | Well-calibrated across clinically relevant risk thresholds [16] | Net benefit and reduction in avoidable SLNBs for thresholds ≥5% [16] |

| MSKCC Nomogram | 0.729 (95% CI 0.671-0.787) [16] | Well-calibrated across clinically relevant risk thresholds [16] | Net benefit and reduction in avoidable SLNBs for thresholds ≥5% [16] | |

| Premenopausal Breast Cancer (5-year risk) | PBCCG Model | 59.1% (95% CI 58.1–60.1%) [17] | Overestimation on average (E/O=1.18); underestimation in lower deciles, overestimation in upper deciles [17] | Not reported |

| Bladder Cancer (Distant Metastasis) | SEER-based Nomogram | Training: 0.732; Internal Validation: 0.750; External Validation: 0.968 [12] | Calibration curves showed good predictive accuracy across cohorts [12] | Not reported |

Table 2: Machine Learning Model Performance for Kinesiophobia and Stroke-Associated Pneumonia

| Clinical Context | Model Type | Discrimination (AUC) | Additional Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kinesiophobia in Postoperative Lung Cancer | Random Forest (RF) | 0.893 [18] | Accuracy: 0.803; Precision: 0.732; Recall: 0.870; F1: 0.795 [18] |

| XGBoost | Not specified | Performance compared, RF was optimal [18] | |

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) | Not specified | Performance compared, RF was optimal [18] | |

| Stroke-Associated Pneumonia in Older Hemorrhagic Stroke | Logistic Regression (LR) | Training: 0.883; Internal: 0.855; External: 0.882 [19] | Demonstrated stable generalizability [19] |

| XGBoost | Not specified | LR demonstrated the best and most stable performance [19] | |

| Naive Bayes | Not specified | LR demonstrated the best and most stable performance [19] |

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation

Model Development and Validation Workflow

The pathway to a robustly validated prediction model follows a structured workflow encompassing development, internal validation, and external validation, with rigorous evaluation at each stage.

Detailed Methodologies for Key Experiments

Multinational Cancer Diagnostic Prediction Algorithm

The study developing algorithms for early cancer diagnosis employed a population-based cohort design using electronic health records from over 7.4 million adults in England (derivation cohort) [1]. The model was externally validated in two separate cohorts totaling over 5.3 million people from across the UK [1].

- Predictors: Model A included age, sex, deprivation, smoking, alcohol, family history, medical diagnoses, and symptoms. Model B additionally incorporated full blood count and liver function tests [1].

- Statistical Analysis: Researchers used multinomial logistic regression to develop separate equations for men and women predicting the absolute probability of 15 cancer types. They assessed for overfitting using heuristic shrinkage and evaluated performance in independent validation cohorts [1].

- Performance Metrics: Discrimination was measured using the c-statistic (equivalent to AUROC). Calibration was assessed visually and statistically. Clinical utility was evaluated using net benefit analysis across various risk thresholds [1].

Melanoma Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy Nomogram Validation

The validation of melanoma nomograms followed a retrospective prognostic validation design using data from 712 melanoma cases in Southern Arizona, a region with high UV index [16].

- Model Application: Three established nomograms (MIA, MSKCC, University of Colorado) were applied to the cohort without recalibration [16].

- Statistical Analysis: Discrimination was assessed via receiver operating characteristic curves and the C-statistic. Calibration was evaluated using calibration plots. Clinical utility was tested through decision curve analysis (DCA) to determine net benefit and the number of net avoidable SLNBs across different risk thresholds [16].

- Threshold Analysis: Performance was specifically examined at clinically relevant risk thresholds (≥5%) and across different age groups to identify potential limitations [16].

Research Reagent Solutions for Prediction Modeling

Table 3: Essential Tools and Data Sources for Prediction Model Research

| Resource Category | Specific Resource | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Data Resources | QResearch/CPRD Databases | Large, linked electronic health record databases from the UK primary care, used for model derivation and validation [1] |

| SEER Database | US cancer registry providing population-level data for developing and validating oncology prediction models [12] | |

| Estonian Biobank | Genetic and clinical data repository enabling development of models incorporating polygenic risk scores [20] | |

| PBCCG Harmonized Datasets | International consortium data specifically for premenopausal breast cancer research, with harmonized variables across cohorts [17] | |

| Statistical Software & Packages | R Software | Open-source environment for statistical computing and graphics, used for developing nomograms and performing decision curve analysis [12] [19] |

| STATA | Statistical software for data management and analysis, particularly used for complex survival analyses [17] | |

| Glmnet Package | R package for implementing LASSO regression for variable selection in high-dimensional data [12] | |

| Validation Frameworks | TRIPOD+AI Guidelines | Reporting guideline for transparent reporting of multivariable prediction models, including those developed with machine learning [15] |

| Decision Curve Analysis | Methodological framework for evaluating the clinical value of prediction models by incorporating clinical consequences [16] | |

| Machine Learning Algorithms | Random Survival Forest | Machine learning method for survival data that can handle complex, non-linear relationships without proportional hazards assumptions [21] |

| XGBoost | Gradient boosting framework that often achieves state-of-the-art results on structured data, used in various cancer prediction studies [18] [19] |

Comparative Analysis and Research Implications

The comparative performance data reveals several critical patterns. First, comprehensive models incorporating diverse data types (e.g., symptoms, clinical factors, and blood tests) demonstrate superior discrimination (C-statistics >0.84) and net benefit compared to simpler models [1]. Second, model performance varies significantly by clinical context, with diagnostic models for general cancer detection generally showing higher discrimination (C-statistics 0.84-0.88) than risk prediction models for specific conditions (AUC 0.59-0.75) [1] [17] [16]. Third, traditional regression methods often perform comparably to complex machine learning algorithms in many clinical scenarios, particularly with structured clinical data [21] [19].

The validation methodologies highlight that external validation in geographically distinct populations is essential for assessing generalizability, as demonstrated by the melanoma nomogram study which tested models developed in Australia and New York on an Arizona population [16]. Furthermore, clinical utility assessment through decision curve analysis provides crucial information beyond traditional discrimination and calibration metrics, directly addressing whether a model would improve clinical decisions [15] [16].

For researchers and drug development professionals, these findings underscore that model selection should be based not merely on discriminatory performance but on comprehensive evaluation of all three core principles within the target population and clinical context. Future research should prioritize model interoperability across diverse healthcare systems, continuous monitoring and updating of deployed models, and integration of novel biomarkers to enhance predictive performance while maintaining calibration and clinical utility [1] [15] [12].

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) into oncology represents a paradigm shift in cancer risk prediction, offering the potential to identify high-risk individuals for targeted screening and early intervention. However, the transition from algorithm development to successful clinical implementation is fraught with challenges, and many promising tools fail to demonstrate real-world utility. A critical analysis of these failures reveals a consistent shortcoming: the absence of rigorous, multi-cohort external validation. This guide objectively compares the performance of various cancer risk prediction algorithms, framing the discussion within the broader thesis that external validation is not merely a final check but a fundamental component of the development process. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, these lessons are essential for building models that are not only statistically sound but also clinically effective and reliable across diverse populations.

The High Stakes of Prediction: Clinical Context and Implementation Failures

Cancer risk prediction algorithms are designed to support critical clinical decisions, from guiding screening referrals to enabling personalized prevention strategies. In the United Kingdom, where cancer survival rates lag behind other developed nations, such tools are seen as vital for achieving the NHS target of diagnosing 75% of cancers at an early (stage 1 or 2), curable stage [1]. Despite this urgent need, implementation in primary care remains low. Qualitative studies have identified barriers including clinician reluctance to rely on algorithmic outputs, challenges in integrating tools into clinical workflows, and practical issues around availability [22].

Beyond these practical hurdles, a core scientific reason for failed implementation is the lack of generalizability. An algorithm performing excellently in its derivation cohort may fail in a different population due to differences in data coding, prevalence of risk factors, or underlying population genetics. For instance, a model trained primarily on one ethnic group may not calibrate correctly for another, leading to systematic over- or under-prediction of risk. Furthermore, without robust external validation, algorithms may be susceptible to "concept drift," where the relationship between predictors and outcomes changes over time, rendering the model obsolete [23]. The failure to adequately test for these factors during development directly undermines clinical trust and leads to non-adoption, regardless of a model's theoretical sophistication.

Experimental Protocols for Rigorous Validation

To avoid implementation failures, a structured and transparent validation protocol is mandatory. The following methodology, exemplified by leading studies, provides a template for rigorous testing.

Cohort Design and Data Sourcing

The foundation of robust validation is independent, high-quality data.

- Derivation Cohort: Used to train and develop the initial algorithm. This should be a large, representative sample. For example, the development of the CanPredict oesophageal cancer algorithm used 12.9 million patient records from 1,354 QResearch general practices [23].

- Validation Cohorts: At least two separate, external cohorts are required to test generalizability.

- Internal Validation: A random sample held out from the derivation cohort (e.g., 20-30%).

- External Validation 1: A cohort from the same broader data source but different sites (e.g., 450 different QResearch practices for CanPredict) [23].

- External Validation 2: A cohort from a completely different data source, such as the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD), which contributed 2.53 million patient records for CanPredict validation [23]. This is the strongest test of portability.

Data should be routinely collected electronic health records (EHRs) from primary care, linked to hospital, mortality, and cancer registry data to ensure complete outcome capture. Key variables include demographics, lifestyle factors (smoking, alcohol), clinical symptoms, comorbidities, medications, and laboratory results [1] [23].

Model Training and Statistical Methods

- Algorithm Selection: Cox proportional hazards models are commonly used for time-to-event data (e.g., 10-year cancer risk) [23]. For diagnostic prediction, multinomial logistic regression can estimate the probability of multiple cancer types simultaneously [1]. Machine learning models, such as Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LightGBM), are also employed for their ability to capture complex, non-linear interactions [6].

- Predictor Selection: Variables are chosen based on established literature and expert clinical opinion. Novel risk factors, such as specific blood tests or medications, should be justified and tested.

- Handling of Data Imperfections: Prespecified methods for imputing missing data and assessing for over-fitting (e.g., heuristic shrinkage) are critical to ensure model robustness [1].

Performance Evaluation Metrics

A comprehensive evaluation requires multiple metrics, calculated separately for each validation cohort [1] [23] [6].

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics for Cancer Risk Prediction Algorithms

| Metric | Definition | Interpretation in a Clinical Context |

|---|---|---|

| Discrimination (C-statistic/AUROC) | Ability to distinguish between patients who will vs. will not develop cancer. | A value of 0.80 means the model correctly ranks a random patient with cancer higher than one without 80% of the time. |

| Calibration | Agreement between predicted probabilities and observed outcomes. | A well-calibrated model predicting a 10% risk should see cancer occur in 10 out of 100 similar patients. |

| Sensitivity | Proportion of true cancer cases correctly identified as high-risk. | Of 100 patients with cancer, a sensitivity of 76% means the model correctly flagged 76 of them [23]. |

| Specificity | Proportion of true non-cases correctly identified as low-risk. | Of 100 cancer-free patients, a specificity of 80% means the model correctly reassured 80 of them [23]. |

| Net Benefit | A decision-analytic measure weighing true positives against false positives at a specific risk threshold. | Quantifies the clinical value of using the model for decision-making versus alternative strategies. |

The following workflow diagram summarizes this multi-stage validation process, illustrating the critical pathway from initial development to the final assessment of real-world readiness.

Performance Comparison: A Data-Driven Analysis

Objectively comparing algorithms requires examining their performance across independent validation cohorts. The tables below synthesize published data from recent studies.

Table 2: Comparative Performance of Diagnostic Cancer Prediction Algorithms (Any Cancer)

| Algorithm / Model | Validation Cohort | C-Statistic (AUROC) | Key Performance Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Novel Model A (with symptoms & clinical factors) [1] | QResearch (England), 2.64M patients | Men: 0.876 (0.874–0.878)Women: 0.844 (0.842–0.847) | Outperformed existing QCancer models, with improved discrimination and net benefit. |

| Novel Model B (adding blood tests) [1] | QResearch (England), 2.64M patients | Men: 0.876 (0.874–0.878)Women: 0.844 (0.842–0.847) | Incorporation of full blood count and liver function tests provided affordable digital biomarkers. |

| LightGBM for Colorectal Cancer [6] | PLCO Trial (Internal Validation) | 0.726 (0.698–0.753) | Model focused on readily available clinical/lifestyle factors for practical primary care use. |

Table 3: Comparative Performance of Long-Term Risk Algorithms

| Algorithm / Model | Validation Cohort | C-Statistic (AUROC) | Calibration & Sensitivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| CanPredict (Oesophageal Cancer) [23] | QResearch, 4.12M patients | Women: 0.859 (0.849–0.868)Men: Similar | Good calibration; sensitivity of 76% for the top 20% highest-risk patients. |

| CanPredict (Oesophageal Cancer) [23] | CPRD, 2.53M patients | Similar to QResearch results | Results were similar, demonstrating robustness across different UK populations. |

| AI Model for Lung Cancer Recurrence [9] | Multi-source (External) | Concordance Index reported | Outperformed TNM staging in stratifying Stage I patients into high/low-risk groups. |

The data reveals that algorithms undergoing extensive external validation, such as CanPredict and the novel models from [1], demonstrate strong and consistent performance across multiple, large-scale cohorts. This rigorous testing builds the evidence base required for clinical trust. In contrast, models with only internal validation, while potentially promising, lack the proven generalizability needed for widespread implementation. The addition of novel data types, such as blood tests [1] or CT radiomics [9], can enhance predictive power, but their value must also be confirmed in external settings.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The development and validation of these models rely on a suite of data and software "reagents." The following table details key resources for building and testing cancer risk prediction algorithms.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Algorithm Development and Validation

| Resource / Solution | Function | Example in Context |

|---|---|---|

| Large-scale EHR Databases | Provide longitudinal, real-world patient data for derivation and validation cohorts. | QResearch [23], CPRD [1], and PLCO Trial [6] databases provide millions of anonymized patient records. |

| Data Linkage Systems | Link primary care records to secondary care, cancer registry, and mortality data to ensure accurate and complete outcome ascertainment. | Crucial for studies where the primary outcome (cancer diagnosis) may occur outside the primary care setting [23]. |

| Specialized Statistical Software (R, Python) | Provide environments for complex statistical modeling, machine learning, and data analysis. | Used for running Cox regression [23], multinomial logistic regression [1], and LightGBM [6]. |

| GPT & Large Language Models (LLMs) | Assist in mining unstructured text from biomedical literature and EHRs to identify experimental conditions and key variables. | A multi-agent LLM system can extract critical experimental conditions (e.g., buffer type, pH) from assay descriptions to standardize data [24]. |

| Benchmark Datasets (e.g., PharmaBench) | Provide standardized, curated datasets for training and benchmarking predictive models, particularly for ADMET properties in drug development. | Comprises 11 ADMET datasets with 52,482 entries, offering a more relevant and extensive benchmark than previous sets [24]. |

The pathway from a validated algorithm to successful clinical implementation involves addressing both technical and human-factor barriers, as visualized below.

The journey from a conceptual cancer risk algorithm to a trusted clinical tool is arduous, with failed implementations often tracing back to insufficient testing beyond the initial development dataset. Rigorous, multi-cohort external validation is the non-negotiable standard that separates speculative tools from clinically actionable ones. It is the process that confirms an algorithm's discrimination, ensures its calibration across diverse populations, and ultimately builds the trust required for adoption by clinicians. As the field advances with more complex models incorporating genomics, radiomics, and digital biomarkers, the foundational principle remains: rigorous testing through external validation is the most critical investment for any team serious about making a tangible impact on cancer care. For researchers and drug developers, this is not just a methodological detail but the core of building translatable and effective predictive health technologies.

Conducting Rigorous External Validation: Frameworks and Best Practices

For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working on cancer risk prediction algorithms, the journey from conceptual model to clinically useful tool requires rigorous validation. While internal validation checks a model's performance on data from the same source, external validation assesses its generalizability to entirely separate populations, healthcare systems, and data collection protocols. This process is crucial for verifying that an algorithm will perform reliably in real-world clinical settings beyond the controlled environment of its development. The selection of appropriate external validation cohorts thus represents a fundamental step in translating predictive models from research artifacts into trustworthy clinical tools.

Despite its importance, robust external validation remains a significant challenge in the field. A systematic scoping review of AI pathology models for lung cancer found that only approximately 10% of developed models undergo any form of external validation, highlighting a critical gap between development and implementation [25]. This article provides a comparative guide to methodologies for sourcing truly external and representative datasets, examining current practices, experimental protocols, and essential tools for strengthening the validation phase of cancer prediction research.

Core Principles of External Cohort Selection

Defining "Truly External" Datasets

A "truly external" validation cohort must demonstrate complete independence from the derivation cohort across multiple dimensions. Key characteristics include:

- Geographical Separation: Sourcing data from different hospitals, regions, or countries than those used for model development.

- Temporal Separation: Using data collected from different time periods than the development data.

- Institutional Independence: Drawing from healthcare systems with different patient populations, clinical workflows, and data recording practices.

- Technical Variation: Incorporating data generated with different equipment, laboratory protocols, or measurement standards.

For instance, a study developing cancer prediction algorithms in England (QResearch database) demonstrated robust external validation by testing performance on separate English populations alongside populations from Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland [1]. This approach validated both geographical and health system generalizability.

Ensuring Representativeness for Clinical Utility

Beyond mere independence, external cohorts must be representative of the intended use population to ensure clinical utility. Considerations include:

- Demographic Diversity: Appropriate distribution of age, sex, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status.

- Clinical Spectrum: Inclusion of the full range of disease severity and co-morbidities expected in practice.

- Data Completeness: Real-world levels of missing data and measurement variability.

- Setting Appropriateness: Data from the clinical setting where the model will ultimately be deployed (e.g., primary care for screening tools, secondary care for diagnostic tools).

Comparative Analysis of External Validation Approaches

Methodologies in Current Cancer Prediction Research

The table below summarizes external validation approaches across recent cancer prediction studies, highlighting cohort sources and key methodological features.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of External Validation Approaches in Cancer Prediction Studies

| Cancer Type | Development Cohort | External Validation Cohort | Key Validation Strengths | Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple Cancers (n=15) [1] | 7.46M patients from England (QResearch) | 2.64M from England + 2.74M from Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland | Geographical & temporal separation; Diverse healthcare systems | C-statistics: 0.876 (men), 0.844 (women) for Model B |

| Young-Onset Colorectal Cancer [26] | 10,874 young individuals from single center (2013-2021) | Temporal validation using 2022 data from same center | Temporal separation; Same center but different time period | AUC: 0.888; Recall: 0.872 |

| Early-Stage Lung Cancer [9] | 1,015 patients from NLST, NEMC, Stanford | 252 patients from North Estonia Medical Centre | Geographical & institutional independence; Multi-national | Hazard Ratio: 3.34 for stage I recurrence |

| Bladder Cancer Metastasis [12] | 2,313 patients from SEER database (US) | 112 patients from Chinese hospital | Geographical & ethnic diversity; Different healthcare systems | AUC: 0.968 in external validation |

| Cancer-Associated VTE [27] | 1,036 patients (retrospective cohort) | 321 patients (prospective cohort) | Prospective validation; Different study design | C-index: 0.709-0.760 across models |

Experimental Protocols for Robust Validation

Protocol for Multi-National Validation

A comprehensive study on cancer prediction algorithms provides a template for large-scale external validation [1]:

- Data Sources: Utilize separate national primary care electronic health record databases with linkage to hospital and mortality data.

- Population Definition: Apply consistent inclusion/exclusion criteria across all cohorts (e.g., adults aged 18-84 with no prior cancer diagnosis).

- Predictor Variables: Harmonize coding systems for symptoms, medical history, laboratory tests, and demographic factors across different databases.

- Outcome Ascertainment: Standardize cancer outcome definitions using linked cancer registry data, hospital records, and death certificates.

- Analysis Plan: Pre-specify performance metrics (discrimination, calibration, clinical utility) and subgroup analyses.

This protocol demonstrated that models incorporating blood tests (Model B) outperformed symptom-only models (Model A) across all external validation settings [1].

Protocol for Imaging-Based Prediction Models

The external validation of a lung cancer recurrence prediction model illustrates specialized considerations for AI imaging models [9]:

- Image Curation: Extensive (re)curation of preoperative CT scans to ensure consistency with clinical metadata and outcomes.

- Multi-Source Data Integration: Combine imaging data with routinely available clinical variables in the prediction model.

- Validation Against Pathologic Standards: Correlate machine learning-derived risk scores with established pathologic risk factors (e.g., lymphovascular invasion, pleural invasion).

- Stratified Performance Analysis: Evaluate model performance specifically within early-stage patients where clinical need is greatest.

This approach confirmed the model's ability to stratify recurrence risk more effectively than conventional staging in stage I patients (HR 3.34 vs 1.98) [9].

Methodological Challenges and Quality Assessment

Common Limitations in Current Practice

The external validation landscape faces several methodological challenges:

- Restricted Datasets: Many studies use artificially clean or restricted datasets that don't reflect real-world clinical environments [25].

- Retrospective Design: Most validations use retrospective data, with prospective studies and randomized trials being rare [25].

- Technical Diversity Insufficiency: Failure to account for variations in equipment, protocols, and measurement standards across institutions.

- Inadequate Reporting: Poor documentation of participant characteristics, missing data, and cohort selection criteria.

A systematic review of AI pathology models found high or unclear risk of bias in 86% of studies in the "Participant selection/study design" domain, highlighting pervasive methodological concerns [25].

Quality Assessment Framework

The QUADAS-AI tool provides a structured approach to assessing validation quality across multiple domains [25]:

- Participant Selection: Evaluate whether participants represent the intended use population.

- Image Selection: Assess appropriateness of image inclusion criteria and technical diversity.

- Reference Standard: Verify adequacy of the gold standard diagnosis.

- Flow and Timing: Examine timing between index test and reference standard.

- Index Test: Evaluate blinding and pre-specification of analysis.

Visualization of Cohort Selection Strategy

The following diagram illustrates a robust workflow for sourcing and validating external cohorts in cancer prediction research:

Diagram Title: External Cohort Selection Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions for Cohort Selection

Table 2: Essential Resources for Sourcing External Validation Cohorts

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function in External Validation | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Public Cancer Databases | SEER Program, TCGA, NLST | Provide diverse patient populations for validation; Enable cross-institutional comparison | Data harmonization required; May lack specific clinical variables |

| International EHR Networks | QResearch (UK), CPRD (UK) | Offer large-scale primary care data with linked outcomes; Enable geographical validation | Variable data quality; Different coding systems |

| Biobanks & Cohort Studies | UK Biobank, NLST | Provide richly phenotyped data with imaging and biomarkers | Access restrictions; May not represent general population |

| Data Harmonization Tools | OHDSI/OMOP Common Data Model | Standardize data structure across different sources; Enable federated analysis | Significant implementation effort; Information loss possible |

| Statistical Software Packages | R, Python, STAN | Implement performance metrics; Conduct calibration analysis | Specialized expertise required; Custom programming needed |

| Quality Assessment Tools | QUADAS-AI, PROBAST | Standardize methodological quality evaluation; Identify risk of bias | Subjective judgment involved; Requires multiple reviewers |

The external validation of cancer prediction algorithms requires meticulous cohort selection that prioritizes both independence from development data and representativeness of intended use populations. Current evidence suggests that models validated across diverse geographical settings, healthcare systems, and time periods demonstrate greater reliability and clinical utility. The integration of methodological rigor in validation design—including prospective studies, comprehensive quality assessment, and appropriate technical diversity—remains essential for bridging the gap between algorithm development and meaningful clinical implementation. As the field progresses, increased attention to these cohort selection principles will strengthen the translational pathway for cancer prediction models, ultimately supporting more personalized and effective cancer care.

External validation is a critical step in assessing the real-world performance of cancer risk prediction algorithms, determining whether a model developed on one population can generalize to others. This process relies on key quantitative metrics that evaluate different aspects of model performance: discrimination (the ability to separate patients with and without the outcome), calibration (the agreement between predicted probabilities and observed outcomes), and overall performance. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding these metrics is essential for evaluating which models are ready for clinical implementation and where improvements are needed.

The C-statistic (or AUC) evaluates discrimination, the Expected/Observed (E/O) ratio and calibration plots assess calibration, and the Polytomous Discrimination Index (PDI) extends discrimination assessment to multi-class outcomes. This guide compares the performance of contemporary cancer prediction algorithms using these metrics, providing a standardized framework for model evaluation in oncology research and development.

Performance Metrics Comparison of Cancer Prediction Algorithms

The table below summarizes the performance metrics of recently developed and validated cancer prediction algorithms across multiple cancer types and specific malignancies.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Cancer Prediction Algorithms in External Validation

| Prediction Model | Cancer Type | C-Statistic (95% CI) | E/O Ratio | Calibration Slope | PDI | Validation Cohort Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CanPredict (Model B) [1] | Any Cancer (Men) | 0.876 (0.874-0.878) | Not Reported | Not Reported | ~0.27* | 2.64M (QResearch) |

| CanPredict (Model B) [1] | Any Cancer (Women) | 0.844 (0.842-0.847) | Not Reported | Not Reported | ~0.26* | 2.64M (QResearch) |

| CanPredict (Model A) [1] | Any Cancer (Men) | 0.872 (0.870-0.874) | Not Reported | Not Reported | ~0.26* | 2.64M (QResearch) |

| CanPredict (Model A) [1] | Any Cancer (Women) | 0.841 (0.839-0.843) | Not Reported | Not Reported | ~0.26* | 2.64M (QResearch) |

| COLOFIT [28] | Colorectal | Not Reported | 1.52 (overall), 1.09 (best period) | 1.05 | Not Applicable | 51,477 |

| Cervical Cancer Nomogram [10] | Cervical Cancer | 0.872 (0.829-0.915) | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | 318 |

| Bladder Cancer Nomogram [29] | Bladder Cancer (DM) | 0.968 | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | 112 |

| Oesophageal Cancer (CanPredict) [23] | Oesophageal Cancer | 0.859 (0.849-0.868) | Good (Not Specified) | Not Reported | Not Reported | 4.12M |

Note: PDI values estimated from confidence intervals reported in [1]; Model A includes clinical factors and symptoms; Model B additionally includes blood test results; DM = Distant Metastasis

Detailed Metric Definitions and Methodologies

C-Statistic (Concordance Statistic)

The C-statistic measures a model's ability to discriminate between patients who experience an event and those who do not. It represents the probability that a randomly selected patient who experienced the event had a higher predicted risk than a randomly selected patient who did not. Values range from 0.5 (no better than chance) to 1.0 (perfect discrimination). In the context of cancer prediction, the CanPredict algorithm achieved C-statistics of 0.876 for men and 0.844 for women for any cancer diagnosis, indicating excellent discrimination [1]. For specific cancers, the cervical cancer nomogram maintained a C-statistic of 0.872 in external validation [10], while the oesophageal cancer model achieved 0.859 [23].

Calculation Methodology:

- For binary outcomes: Equivalent to the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC)

- For time-to-event data: Calculated using Harrell's C-index or similar time-dependent concordance measures

- Typically reported with 95% confidence intervals to indicate precision

Expected/Observed (E/O) Ratio

The E/O ratio is a fundamental measure of calibration, representing the ratio of the number of events predicted by the model (expected) to the number actually observed. An ideal E/O ratio is 1.0, indicating perfect calibration. Values below 1.0 suggest overprediction (the model predicts more events than occur), while values above 1.0 indicate underprediction. The COLOFIT model for colorectal cancer demonstrated how E/O ratios can vary across populations and time, with an overall ratio of 1.52 (indicating underprediction) that improved to 1.09 in certain periods [28]. This variability highlights the importance of evaluating calibration across different clinical settings.

Calculation Methodology:

- Sum all predicted probabilities for the validation cohort (Expected events)

- Count the actual number of observed events in the validation cohort (Observed events)

- Calculate ratio: E/O = Σ(Predicted Probabilities) / Observed Events

Calibration Plots and Slopes

Calibration plots provide visual representation of model calibration by plotting predicted probabilities against observed outcomes. A perfectly calibrated model follows the 45-degree line. The calibration slope quantifies this relationship, with an ideal value of 1.0. Values below 1.0 suggest the model needs shrinkage of its coefficients, while values above 1.0 indicate underfitting. In competing risk settings, calibration assessment becomes more complex, requiring evaluation of each cause-specific model to identify sources of miscalibration [30] [31]. The COLOFIT model maintained a calibration slope of 1.05 despite issues with the E/O ratio, indicating generally appropriate coefficient magnitudes [28].

Assessment Methodology:

- Divide patients into deciles based on predicted risk

- Calculate observed event rate for each decile (using Kaplan-Meier for time-to-event data)

- Plot mean predicted probability vs. observed event rate for each decile

- Fit a regression line to calculate the calibration slope

Polytomous Discrimination Index (PDI)

The PDI extends discrimination assessment to multi-class outcomes, such as distinguishing between multiple cancer types simultaneously. This is particularly valuable for comprehensive cancer prediction algorithms that aim to identify both the presence and type of cancer. The CanPredict algorithm, which predicts 15 cancer types, reported PDI values of approximately 0.27 for men and 0.26 for women [1]. These values indicate the model's ability to correctly classify patients not just as having cancer versus not, but specifically which type of cancer they have.

Calculation Methodology:

- Extends the concept of the C-statistic to multi-class outcomes

- Computes the probability that a patient with a particular cancer type has a higher predicted probability for that specific cancer than another patient with a different cancer type has for that same cancer

- Particularly useful for algorithms using multinomial logistic regression

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Large-Scale Algorithm Validation

The external validation of comprehensive cancer prediction algorithms like CanPredict followed rigorous methodology [1] [32]. The development cohort included 7.46 million patients from England, with validation conducted in two separate cohorts totaling over 5.38 million patients from across the UK. The protocol included:

- Data Extraction: Anonymized electronic health records from primary care practices linked to hospital episode statistics, cancer registry data, and mortality records

- Predictor Inclusion: Two models developed - Model A with clinical factors (age, sex, deprivation, symptoms, medical history) and Model B adding routine blood tests (full blood count, liver function tests)

- Statistical Analysis: Multinomial logistic regression to predict 15 cancer types simultaneously, with separate equations for men and women

- Validation Approach: Performance assessed in completely separate validation cohorts from different geographic populations

- Comparison Metrics: Evaluation against existing QCancer algorithms using discrimination, calibration, sensitivity, and net benefit analyses

Competing Risks Analysis

When validating models for specific cancer types, competing risks methodology is essential [30] [31]. The protocol includes:

- Cause-Specific Hazards Modeling: Separate models for the event of interest (specific cancer) and competing events (other cancers, non-cancer death)

- Pseudo-Observations Calculation: Used to estimate observed risks for calibration plots in the presence of competing risks

- Stratified Analysis: Assessment of calibration within subgroups based on the prognostic index

- Comprehensive Calibration Assessment: Evaluation of both cause-specific absolute risks and each cause-specific hazards model component using the complement of the cause-specific survival function

Figure 1: External Validation Workflow for Cancer Prediction Models

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Tools for Cancer Prediction Model Development and Validation

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| QResearch Database [1] | Electronic Health Record Database | Population-scale data for model development/validation | CanPredict algorithm development (7.46M patients) |

| CPRD Gold [1] | Electronic Health Record Database | Independent validation cohort | CanPredict validation (2.74M patients) |

| SEER Database [10] [29] | Cancer Registry Database | Cancer incidence and survival data | Cervical/bladder cancer nomogram development |

| R statistical software [10] [33] | Statistical Analysis Platform | Model development, validation, and visualization | Nomogram development and calibration plotting |

| calibrationCurves R package [33] | Statistical Software Package | Calibration assessment and visualization | Thyroid cancer model validation |

| dcurves R package [33] | Statistical Software Package | Decision curve analysis | Clinical utility assessment |

| SEER*Stat [10] [29] | Data Extraction Tool | Access and analysis of SEER database data | Patient cohort identification |

| Flexible Parametric Survival Models [31] | Statistical Methodology | Competing risks analysis | Cause-specific hazard modeling |

Comparative Analysis and Clinical Implications

The performance metrics reveal several important patterns across cancer prediction algorithms. Comprehensive models like CanPredict that incorporate multiple predictor types (including routine blood tests) demonstrate superior discrimination, with C-statistics exceeding 0.84 for any cancer diagnosis [1]. The inclusion of commonly available blood tests (full blood count and liver function tests) in Model B provided modest but consistent improvements in discrimination across most cancer types compared to Model A, which relied solely on clinical factors and symptoms [1].

The variation in E/O ratios observed with the COLOFIT model highlights how population characteristics and changing clinical practices affect model performance [28]. The model's performance varied significantly across different time periods, with referral reduction potential ranging from 23% to -2% depending on FIT testing rates and the proportion of high-risk symptoms in the population. This underscores the necessity for local validation and periodic model recalibration.

For specific cancers, nomograms demonstrate excellent discrimination, particularly for predicting distant metastasis in bladder cancer (C-statistic: 0.968) [29]. However, these specialized models typically address narrower clinical questions and require disease-specific validation.

The PDI metric provides crucial information for multi-class prediction algorithms, quantifying their ability to not just identify cancer presence but distinguish between cancer types [1]. This is particularly valuable in primary care settings where non-specific symptoms may indicate multiple possible cancers.

From a clinical implementation perspective, algorithms must demonstrate both strong discrimination and calibration. A model with excellent discrimination but poor calibration may lead to inappropriate clinical decisions due to systematic over- or under-prediction of risk. The integration of these validated algorithms into clinical decision support systems, with appropriate threshold setting based on local cancer prevalence and healthcare resources, can potentially facilitate earlier cancer diagnosis and improve patient outcomes.

The development of algorithms for multi-cancer early detection (MCED) and risk prediction represents a transformative frontier in oncology. The United Kingdom, with its centralized healthcare systems and rich, linkable data resources, provides an unparalleled environment for conducting large-scale validation studies essential for translating these models from research to clinical practice. External validation in independent, diverse populations is a critical step in the scientific evaluation of any predictive algorithm, as it provides a true measure of its generalizability, calibration, and potential for real-world impact [1]. This case study examines the methodologies and outcomes of recent, large-scale efforts to validate multi-cancer prediction algorithms within UK populations, comparing their performance and highlighting the evolution of validation science in this field.

Comparative Analysis of Validated Multi-Cancer Algorithms

The following section objectively compares the performance and characteristics of several key algorithms that have undergone substantial validation in UK cohorts.

Clinical and Blood Test-Enhanced Prediction Algorithms

A landmark study developed and externally validated two diagnostic prediction algorithms to estimate the probability of having a current, undiagnosed cancer for 15 cancer types. The first model (Model A) incorporated predictors like age, sex, deprivation, smoking, alcohol, family history, medical diagnoses, and symptoms. The second model (Model B) additionally included commonly used blood tests (full blood count and liver function tests) [1].

Table 1: Performance of Clinical Prediction Algorithms in UK Validation Cohorts

| Metric | Model A (Clinical & Symptoms) | Model B (Model A + Blood Tests) |

|---|---|---|

| Validation Cohort | QResearch (England): 2.64M people, 44,984 cancersCPRD (Scotland, Wales, NI): 2.74M people, 32,328 cancers | QResearch (England): 2.64M people, 44,984 cancersCPRD (Scotland, Wales, NI): 2.74M people, 32,328 cancers |

| Overall C-Statistic (AUROC) - Men | 0.872 (95% CI 0.870-0.874) | 0.876 (95% CI 0.874-0.878) |

| Overall C-Statistic (AUROC) - Women | 0.840 (95% CI 0.837-0.842) | 0.844 (95% CI 0.842-0.847) |

| Key Cancer-Specific C-Statistics (Men, Model B) | Lung: 0.903, Pancreatic: 0.892, Liver: 0.913, Myeloma: 0.883 | |

| Key Cancer-Specific C-Statistics (Women, Model B) | Lung: 0.885, Pancreatic: 0.875, Liver: 0.894, Ovarian: 0.819, Cervical: 0.694 | |

| Comparison to Existing Models | Outperformed existing QCancer algorithms in discrimination, calibration, sensitivity, and net benefit. | |

| Experimental Protocol | Model derivation used a population of 7.46 million adults in England. Multinomial logistic regression was used to develop separate equations for men and women to predict the absolute probability of 15 cancer types. |

National Data Integration for Multi-Cancer Risk Cohorts

A 2025 study presented a novel approach to constructing multi-cancer risk cohorts using national data from medical helplines (NHS 111) and secondary care from all hospitals in England. Focusing on nine cancer types with high rates of late-stage diagnosis, this research demonstrated the utility of non-clinician-initiated data for population risk stratification [34].

Table 2: Performance of NHS Data-Integrated Model for Predicting Cancer Diagnosis

| Cancer Type | Area Under the Curve (AUC) | Key Influential Features |

|---|---|---|

| Bladder | 0.80 | NHS 111 symptoms, frequency of hospital appointments, comorbidities |

| Oesophageal | 0.83 | NHS 111 symptoms, frequency of hospital appointments, comorbidities |

| Ovarian | 0.69 | NHS 111 symptoms, frequency of hospital appointments, comorbidities |

| Pancreatic | 0.79 | NHS 111 symptoms, frequency of hospital appointments, comorbidities |

| Stomach | 0.78 | NHS 111 symptoms, frequency of hospital appointments, comorbidities |

| Head and Neck | 0.76 | NHS 111 symptoms, frequency of hospital appointments, comorbidities |

| Lymphoma | 0.77 | NHS 111 symptoms, frequency of hospital appointments, comorbidities |

| Myeloma | 0.75 | NHS 111 symptoms, frequency of hospital appointments, comorbidities |

| Kidney | 0.78 | NHS 111 symptoms, frequency of hospital appointments, comorbidities |

| Validation Scope | 23.6 million patient histories of individuals aged 40-74 in England. | |

| Model Type | XGBoost, selected based on performance comparison with other classifiers. |

AI-Empowered Blood-Based Multi-Cancer Early Detection

The OncoSeek test is an AI-empowered, blood-based test for multi-cancer early detection. While not exclusively validated in a UK population, its large-scale, multi-centre validation framework provides a relevant comparison for MCED methodologies. The test integrates a panel of seven protein tumour markers (PTMs) with clinical data using artificial intelligence [35].

Table 3: Performance of the OncoSeek MCED Test Across Multiple Cohorts

| Metric | Performance in ALL Cohort (7 cohorts) | Performance in Symptomatic Cohort (HNCH) |

|---|---|---|

| Total Participants | 15,122 (3,029 cancer; 12,093 non-cancer) | Not Specified |

| Sensitivity | 58.4% (95% CI: 56.6%-60.1%) | 73.1% (95% CI: 70.0%-76.0%) |

| Specificity | 92.0% (95% CI: 91.5%-92.5%) | 90.6% (95% CI: 87.9%-92.9%) |

| Area Under Curve (AUC) | 0.829 | 0.883 |

| Tissue of Origin (TOO) Accuracy | 70.6% for true positives | Not Specified |

| Key Cancer Sensitivities | Bile duct: 83.3%, Pancreas: 79.1%, Ovary: 74.5%, Lung: 66.1%, Breast: 38.9% | Not Specified |

| Experimental Protocol | Multi-centre validation across 7 centres in 3 countries, using 4 quantification platforms and 2 sample types (serum and plasma). Assays demonstrated high consistency across different laboratories (Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.99-1.00). |

Polygenic Risk Score Integration for Cancer Risk Prediction

Another approach integrated polygenic risk scores (PRS) with clinical variables for risk prediction of eight cancers. This model was developed using the UK Biobank, a large-scale, prospective cohort study [36].

Table 4: Performance of Polygenic Risk Score (PRS) and Clinical Model

| Cancer Type | Area Under the Curve (AUC) | Risk Stratification (Top 5% vs. Lowest 10%) |

|---|---|---|

| Lung Cancer | 0.831 (95% CI: 0.817-0.845) | Not Specified |

| Breast Cancer | 0.755 (95% CI: 0.745-0.765) | Nearly 13x greater risk |

| Colorectal Cancer | 0.673 (95% CI: 0.657-0.689) | Not Specified |

| Prostate Cancer | 0.733 (95% CI: 0.721-0.745) | Not Specified |

| Ovarian Cancer | 0.618 (95% CI: 0.581-0.655) | Not Specified |

| Bladder Cancer | 0.642 (95% CI: 0.622-0.662) | Not Specified |

| Pancreatic Cancer | 0.647 (95% CI: 0.611-0.683) | Not Specified |

| Kidney Cancer | 0.659 (95% CI: 0.635-0.683) | Not Specified |

| Key Finding | Combination of PRS and clinical risk factors had better predictive performance than either alone. PRS was more predictive for early-onset cancer, while clinical risk was more predictive for late-onset cancer. | |

| Experimental Protocol | Used UK Biobank to train best polygenic risk scores from 5 methods and selected relevant clinical variables from 733 baseline traits through XGBoost. Combined PRS and clinical variables in Cox proportional hazards models. |

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Workflows

This section details the core methodologies employed in the development and validation of the algorithms discussed.

Workflow for National Data Integration and Model Validation

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive process of building and validating a multi-cancer prediction model using national-scale UK data sources, as exemplified by the NHS 111 and secondary care study [34].

Algorithm Development and External Validation Protocol