Explainable AI in Clinical Decision Support: Building Trust, Transparency, and Efficacy for Biomedical Research

The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) into Clinical Decision Support Systems (CDSS) promises to revolutionize healthcare by enhancing diagnostic precision and personalized treatment.

Explainable AI in Clinical Decision Support: Building Trust, Transparency, and Efficacy for Biomedical Research

Abstract

The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) into Clinical Decision Support Systems (CDSS) promises to revolutionize healthcare by enhancing diagnostic precision and personalized treatment. However, the 'black-box' nature of complex AI models remains a significant barrier to clinical adoption, raising concerns about trust, accountability, and potential bias. This article provides a comprehensive analysis of Explainable AI (XAI) for a audience of researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational need for transparency in high-stakes medical environments, reviews cutting-edge XAI methodologies and their clinical applications, addresses critical implementation challenges such as workflow integration and trust calibration, and evaluates frameworks for validating and comparing XAI effectiveness. By synthesizing the latest research, this review aims to guide the development of transparent, trustworthy, and clinically actionable AI tools that can be safely integrated into the biomedical research and development pipeline.

The Imperative for Transparency: Why Explainable AI is Non-Negotiable in Clinical Decision Support

The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) into healthcare promises to revolutionize patient care by enhancing diagnostic precision, personalizing treatment plans, and streamlining clinical workflows [1] [2]. However, the proliferation of sophisticated machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) models has introduced a significant challenge: the "black box" problem [1] [3]. This term describes AI systems whose internal decision-making processes are opaque, meaning that while they can produce highly accurate outputs, the reasoning behind these conclusions cannot be easily understood by human users [3] [4]. In high-stakes domains like medicine, this opacity creates a substantial trust and accountability gap [5].

Clinicians are justifiably reluctant to base decisions on recommendations they cannot verify or interpret [2] [3]. This lack of transparency challenges core medical ethical principles, including patient autonomy and the requirement for informed consent [3] [4]. Furthermore, the black-box nature of these systems complicates the assignment of liability when errors occur, potentially leaving a vacuum of accountability among developers, physicians, and healthcare institutions [3] [5]. This paper examines the technical and ethical dimensions of the black-box problem within Clinical Decision Support Systems (CDSS), framing it as the central impediment to trustworthy AI in healthcare and exploring the emerging solutions aimed at bridging this critical gap.

Quantifying the Trust Gap: Evidence and Impact

The challenges posed by black-box AI are not merely theoretical; they have tangible effects on clinical adoption and effectiveness. Recent research quantifies the trust gap and explores its consequences.

Table 1: Documented Impacts of the Black-Box Problem in Healthcare AI

| Impact Dimension | Quantitative / Qualitative Evidence | Source Domain |

|---|---|---|

| Barrier to Adoption | Over 65% of organizations cite "lack of explainability" as the primary barrier to AI adoption. [6] | Cross-sector (including healthcare) |

| Clinical Reliance | AI is "extremely influential" on doctor prescriptions, but Explainable AI (XAI) is not more influential than unexplainable AI. [4] | Clinical Decision-Making |

| Psychological & Financial Harm | Unexplainability can cause psychological distress and financial burdens for patients, e.g., from incorrect AI-driven diagnoses. [3] | Patient-Centered Care |

| Undermined Patient Autonomy | Lack of explainability limits a physician's ability to convey information, impeding shared decision-making and informed consent. [3] [4] | Medical Ethics & Law |

A systematic review of XAI for CDSS using non-imaging data highlights that a primary challenge is balancing explanation faithfulness (accuracy) with user plausibility, which is crucial for building appropriate trust [7]. This trust is not automatically conferred by providing explanations; one study found that while AI is highly influential on doctors' decisions, the presence of XAI did not increase that influence, and there was no correlation between self-reported influence and actual influence [4]. This suggests that the mere presence of an explanation is insufficient; it must be meaningful, usable, and integrated into the clinical workflow to bridge the trust gap effectively [8].

Technical Architectures for Explainability: From Black Box to Glass Box

To address the black-box problem, the field of Explainable AI (XAI) has developed a suite of techniques to make AI models more transparent and interpretable. These methods can be broadly categorized into two groups: ante hoc (intrinsically interpretable models) and post hoc (methods applied after a model makes a decision) [8].

Table 2: Key Explainable AI (XAI) Techniques and Their Applications in Healthcare

| XAI Technique | Category | Mechanism | Example Healthcare Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) [2] [6] | Post hoc, Model-agnostic | Uses game theory to assign each feature an importance value for a specific prediction. | Identifying key risk factors for sepsis prediction from Electronic Health Record (EHR) data. [2] |

| LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations) [2] [6] | Post hoc, Model-agnostic | Creates a local, interpretable surrogate model to approximate the black-box model's predictions for a single instance. | Explaining an individual patient's cancer diagnosis from genomic data. [2] |

| Grad-CAM (Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping) [2] | Post hoc, Model-specific | Produces heatmaps that highlight important regions in an image for a model's decision. | Localizing tumors in histology images or MRIs. [2] |

| Counterfactual Explanations [6] [8] | Post hoc, Model-agnostic | Shows the minimal changes to input features needed to alter the model's outcome. | Informing a patient: "If your cholesterol were 20 points lower, your heart disease risk would be classified as low." |

| Attention Mechanisms [2] | (Often) Ante hoc, Model-specific | Allows models to learn and highlight which parts of input data (e.g., words in a clinical note) are most relevant. | Analyzing sequential medical data for disease prediction. [2] |

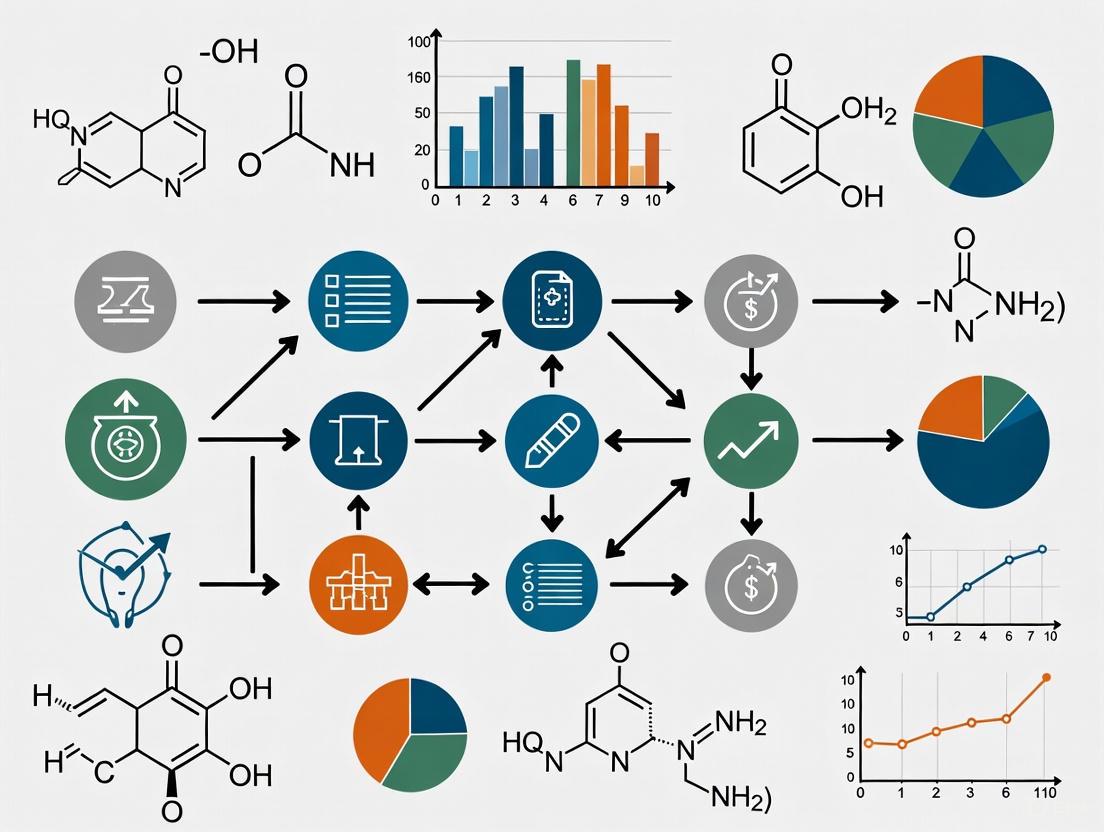

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and relationship between different XAI approaches in a clinical research context:

Experimental Protocols for Evaluating XAI in Clinical Research

For XAI to be clinically adopted, rigorous evaluation is paramount. This requires moving beyond technical metrics to include human-centered assessments. The following protocol outlines a robust methodology for evaluating an XAI system.

Objective: To assess the efficacy of an XAI method in explaining a predictive model for disease risk (e.g., Sepsis) in an ICU setting, focusing on technical fidelity, user trust, and clinical utility.

Phase 1: Model Development and Technical XAI Evaluation

- Data Preparation: Use a retrospective, de-identified dataset from EHRs (e.g., MIMIC-IV). Key features include vital signs, laboratory values, and demographic data. The outcome variable is the onset of sepsis within a 6-hour window [2] [7].

- Model Training: Train a black-box model (e.g., Gradient Boosting or LSTM) and an intrinsically interpretable baseline model (e.g., Logistic Regression) [2].

- XAI Application: Apply post hoc XAI methods (e.g., SHAP, LIME) to the black-box model to generate explanations for individual predictions [2] [8].

- Technical Metrics:

- Explanation Fidelity: Measure how well the explanation approximates the black-box model's behavior. For LIME, this is the fidelity of the local surrogate model. For SHAP, this can be measured via the consistency of its attributions [7] [8].

- Accuracy: Standard metrics (AUC, F1-score) to ensure model performance is maintained [2].

Phase 2: Human-Centered Evaluation

- Study Design: A mixed-methods approach combining quantitative tasks with qualitative feedback [7] [8].

- Participants: Recruit clinicians (e.g., intensivists, ICU nurses) and present them with a series of patient cases in a simulated CDSS interface.

- Experimental Workflow: The workflow for this human-centered evaluation phase is methodically structured as follows:

- Key Metrics:

- Trust and Usability: Measured via standardized scales (e.g., the Trust in Automation scale) and System Usability Scale (SUS) [7] [8].

- Clinical Reasoning Alignment: Qualitative analysis of interviews to determine if explanations align with or challenge clinical intuition [7] [8].

- Actionability: The degree to which the explanation influences a clinical decision, such as initiating a treatment protocol [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents for XAI Experimentation

Table 3: Essential Materials and Tools for XAI Research in Healthcare

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in XAI Research |

|---|---|---|

| SHAP Library [2] [8] | Software Library | Computes consistent feature importance values for any model based on game theory. |

| LIME Package [2] [8] | Software Library | Generates local, interpretable surrogate models to explain individual predictions. |

| Electronic Health Record (EHR) Datasets (e.g., MIMIC-IV) [2] [7] | Data Resource | Provides structured, real-world clinical data for training and validating AI/XAI models. |

| Grad-CAM Implementation (e.g., in PyTorch/TensorFlow) [2] | Software Library | Generates visual explanations for convolutional neural networks (CNNs) used in medical imaging. |

| User Interface (UI) Prototyping Tools (e.g., Figma) [8] | Design Software | Enables the co-design of CDSS interfaces that effectively present XAI outputs to clinicians. |

The black-box problem represents a critical juncture in the adoption of AI in healthcare. While the performance of these systems is often remarkable, a lack of transparency fundamentally undermines trust, accountability, and ethical practice [3] [5]. Bridging this gap requires a multi-faceted approach that integrates technical innovation with human-centered design and rigorous validation.

The future of trustworthy healthcare AI lies not in choosing between performance and explainability, but in developing systems that achieve both. This involves a concerted effort from interdisciplinary teams—including computer scientists, clinicians, ethicists, and regulators—to create frameworks like the proposed Healthcare AI Trustworthiness Index (HAITI) [5]. By prioritizing explainability through robust XAI methods, user-centered design, and comprehensive evaluation protocols, we can unlock the full potential of AI to augment clinical expertise, enhance patient safety, and foster a new era of data-driven, transparent, and accountable medicine.

The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) into clinical decision support systems (CDSS) represents a paradigm shift in modern healthcare, offering unprecedented capabilities for enhancing diagnostic precision, risk stratification, and treatment planning [2]. However, the "black-box" nature of many advanced AI models has raised significant concerns regarding transparency, accountability, and trust [8]. This technological challenge has catalyzed a rapid regulatory evolution, beginning with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and culminating in the world's first comprehensive AI legal framework—the EU AI Act [9] [10]. These regulatory frameworks collectively establish explainable AI (XAI) not merely as a technical enhancement but as a fundamental legal requirement for high-stakes healthcare applications.

For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals operating within the European market, understanding this regulatory trajectory is essential for both compliance and innovation. The GDPR, implemented in 2018, introduced foundational principles of transparency and the "right to explanation" for automated decision-making [2]. The newly enacted EU AI Act builds upon this foundation by establishing a detailed, risk-based regulatory ecosystem that imposes stringent requirements for AI systems in clinical settings [9] [10]. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical analysis of these regulatory drivers, with a specific focus on their implications for the development, validation, and deployment of explainable AI in clinical research and decision support systems.

Regulatory Foundations: From GDPR to the AI Act

The GDPR Precursor: Establishing the Right to Explanation

While not exclusively focused on AI, the GDPR (Regulation (EU) 2016/679) laid crucial groundwork for algorithmic transparency by establishing individuals' rights regarding automated processing. Articles 13-15 and 22 explicitly provide individuals with the right to obtain "meaningful information about the logic involved" in automated decision-making systems that significantly affect them [2]. In healthcare contexts, this translates to a legal obligation for CDSS developers and deployers to provide explanations for AI-driven diagnoses or treatment recommendations upon request. The regulation mandates that data processing must be fair, transparent, and lawful, principles that inherently challenge purely opaque AI systems [11]. The GDPR's emphasis on purpose limitation and data minimization further constrains how AI models can be developed and the types of data they can process, establishing privacy as a complementary regulatory concern to transparency.

The EU AI Act: A Risk-Based Framework for Healthcare AI

The EU AI Act (Regulation (EU) 2024/1689), which entered into force in August 2024, establishes a comprehensive, risk-based regulatory framework specifically for AI systems [9]. It categorizes AI applications into four distinct risk levels, with corresponding regulatory obligations:

Unacceptable Risk: Banned AI practices include all systems considered a clear threat to safety, livelihoods, and rights. Specific prohibitions relevant to healthcare include:

- Harmful AI-based manipulation and deception

- Harmful AI-based exploitation of vulnerabilities of specific social groups

- Social scoring by public authorities

- AI for individual criminal offense risk assessment or prediction

- Untargeted scraping of facial images from the internet or CCTV to create facial recognition databases [9]

- These prohibitions became applicable in February 2025.

High-Risk AI Systems: This category encompasses most clinical decision support applications, including:

- AI safety components in critical infrastructures (e.g., transport), the failure of which could put life and health at risk

- AI solutions used in education and vocational training that may determine access to education and professional course (e.g., scoring of exams)

- AI-based safety components of products (e.g., AI application in robot-assisted surgery)

- AI tools for employment, management of workers, and access to self-employment (e.g., CV-sorting software for recruitment)

- AI systems used to provide access to essential private and public services (e.g., credit scoring denying citizens opportunity to obtain a loan)

- AI systems used in certain areas of law enforcement and migration, asylum, and border control management

- AI solutions used in the administration of justice and democratic processes [9]

- The strict rules for high-risk AI systems will come into effect in August 2026 and August 2027.

Limited Risk: This category primarily entails transparency risk, referring to the need for transparency around AI use. The AI Act introduces specific disclosure obligations. For instance, users interacting with chatbots must be made aware they are communicating with an AI. Providers of generative AI must ensure AI-generated content is identifiable, with clear labelling for deep fakes and text published to inform the public on matters of public interest [9]. These transparency rules come into effect in August 2026.

Minimal Risk: The vast majority of AI systems with minimal or no risk, such as AI-enabled video games or spam filters, are not subject to further regulation under the AI Act [9].

The diagram below illustrates this risk-based classification and its implications for healthcare AI systems, particularly Clinical Decision Support Systems (CDSS).

Regulatory Timelines and Compliance Deadlines

Table: Key Implementation Deadlines of the EU AI Act

| Provision | Effective Date | Implications for Clinical AI Research |

|---|---|---|

| AI Act Entry into Force | August 2024 [9] | The regulation becomes EU law. |

| Prohibited AI Practices | February 2025 [9] | Banned applications (e.g., harmful manipulation, social scoring) become illegal. |

| Rules for General-Purpose AI (GPAI) Models | August 2025 [9] | Transparency and copyright-related rules for GPAI models become applicable. |

| Transparency Rules | August 2026 [9] | Disclosure obligations for AI interactions (e.g., chatbots) and AI-generated content (e.g., deepfakes) apply. |

| High-Risk AI Systems | August 2026 / August 2027 [9] | Strict obligations for high-risk AI systems, including most CDSS, become applicable. |

Technical Requirements for Explainability under the AI Act

Core Components of AI Transparency

The EU AI Act operationalizes explainability through several interconnected components that form the foundation of compliant AI systems for healthcare:

- Explainability: The ability to provide clear, user-understandable reasons behind AI decisions or recommendations in natural language or visual explanations [10]. For a CDSS, this means generating explanations that clinicians can interpret within their clinical workflow, such as highlighting key patient factors that contributed to a sepsis risk prediction [2] [8].

- Interpretability: The technical capacity to analyze and understand how input data, parameters, and processes within an AI system produce specific outputs [10]. This requires specialized tools for model inspection and visualization that enable technical teams to audit system behavior and ensure alignment with clinical reasoning patterns.

- Accountability: Establishing traceability mechanisms that assign clear responsibility for AI system decisions, errors, and downstream consequences [10]. This supports both internal governance and regulatory review by maintaining transparent chains of responsibility throughout the AI development and deployment lifecycle.

- Traceability: Maintaining comprehensive records, logs, and documentation tracking the development, training, input data, and operating contexts of AI systems [10]. This enables reconstruction of decisions and auditing of compliance, which is particularly crucial for clinical validation and post-market monitoring.

Specific Obligations for High-Risk CDSS

For AI-based Clinical Decision Support Systems classified as high-risk, the AI Act mandates rigorous technical and process-oriented requirements [9] [10]:

- Risk Management System: Continuous iterative risk assessment and mitigation throughout the entire lifecycle of the AI system.

- Data Governance: High-quality datasets feeding the system with appropriate bias detection and mitigation measures to minimize risks of discriminatory outcomes.

- Technical Documentation: Detailed documentation providing all information necessary for authorities to assess the system's compliance ("technical documentation").

- Record-Keeping: Automated logging of the AI system's activity to ensure traceability of results ("logging of activity").

- Transparency and Information to Users: Clear and adequate information to the deployer about the system's capabilities, limitations, and expected performance.

- Human Oversight: Measures designed to be effectively overseen by humans during the period of use.

- Accuracy, Robustness, and Cybersecurity: A high level of performance in these areas to ensure the system's resilience against errors and threats.

Explainable AI (XAI) Methodologies for Regulatory Compliance

Taxonomy of XAI Techniques

The pursuit of regulatory compliance necessitates the adoption of specific XAI methodologies. These can be broadly categorized into ante hoc (inherently interpretable) and post hoc (explaining existing black-box models) approaches [8].

Table: Key XAI Methods for Clinical Decision Support Systems

| XAI Method | Type | Scope | Clinical Application Example | Regulatory Alignment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) [2] [12] | Post hoc, Model-agnostic | Local & Global | Quantifies the contribution of each patient feature (e.g., lab values, vitals) to a specific prediction (e.g., sepsis risk). | Supports Explainability (Article 13) |

| LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations) [8] | Post hoc, Model-agnostic | Local | Creates a local surrogate model to approximate the black-box model's prediction for a single instance. | Supports Explainability & Interpretability |

| Grad-CAM (Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping) [2] | Post hoc, Model-specific | Local | Produces heatmaps highlighting regions of medical images (e.g., MRI, histology) most influential to a diagnosis. | Provides visual evidence for Traceability |

| Counterfactual Explanations [8] | Post hoc, Model-agnostic | Local | Indicates the minimal changes to input features required to alter a model's output (e.g., "If platelet count were >150k, the bleeding risk would be low."). | Enhances user understanding per Transparency requirements |

| Decision Trees / RuleFit [8] | Ante hoc | Global & Local | Provides a transparent, rule-based model that is inherently interpretable, often at a potential cost to performance. | Facilitates full Interpretability |

Experimental Protocol for Validating XAI in CDSS

To ensure compliance with the AI Act's requirements for high-risk systems, researchers must adopt rigorous validation protocols for their XAI implementations. The following workflow outlines a comprehensive methodology for developing and validating an explainable CDSS, from problem definition to deployment and monitoring.

Phase 1: Problem Formulation and Data Curation

- Define Clinical Task: Precisely specify the clinical prediction task (e.g., early sepsis detection, cancer metastasis prediction), ensuring alignment with a well-defined clinical workflow [8] [13].

- Data Curation & Annotation: Collect and preprocess multimodal data (EHR, medical images, genomics). Implement rigorous de-identification to comply with GDPR. Annotate data with clinical experts to establish ground truth [2] [14].

- Regulatory Risk Classification: Conduct an initial assessment to confirm the CDSS will be classified as a high-risk AI system, thereby defining the applicable regulatory requirements from the outset [9].

Phase 2: Model and XAI Development

- Base Model Training: Develop and train the core AI/ML model (e.g., CNN for imaging, GBM for tabular EHR data) using appropriate training, validation, and test splits [2].

- XAI Method Selection: Choose appropriate ante hoc or post hoc XAI methods (e.g., SHAP, LIME, Grad-CAM) based on the model architecture, data type, and clinical context (refer to Table 2) [8] [12].

- Explanation Generation: Implement the technical pipeline to generate explanations (e.g., feature importance scores, saliency maps) for the model's predictions [12].

Phase 3: Iterative Evaluation and Validation

- Model Performance Metrics: Evaluate the base model using standard metrics (AUC-ROC, accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score) on a held-out test set [2] [14].

- XAI Fidelity Assessment: Quantitatively evaluate the quality of the explanations. For post hoc methods, this involves measuring fidelity—how well the explanation approximates the true model's decision process for that instance [8].

- Clinical Utility Study: Conduct user studies with clinical professionals (e.g., physicians, nurses) to assess the actionability and interpretability of the explanations. Metrics include task time, diagnostic accuracy with the AI, and subjective feedback via surveys (e.g., System Usability Scale) and interviews [8] [13]. This phase is critical for demonstrating compliance with the "Transparency and information to users" requirement.

Phase 4: Documentation and Deployment Preparation

- Compile Technical Dossier: Prepare comprehensive documentation required by the AI Act, including data sheets, model cards, details on the XAI methods, and results from all validation studies [9] [10].

- Implement Human Oversight Mechanisms: Design the clinical user interface to present explanations effectively and facilitate informed human decision-making, as mandated by the AI Act [9] [8].

- Deploy with Continuous Monitoring: Plan for post-market monitoring to track model performance and explanation fidelity, identifying concept drift and ensuring ongoing compliance [9].

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for XAI-CDSS Development

| Reagent / Resource | Type | Function in XAI Research | Exemplary Tools / Libraries |

|---|---|---|---|

| XAI Software Libraries | Computational Tool | Provides pre-implemented algorithms for generating post hoc explanations (SHAP, LIME, Counterfactuals). | SHAP [12], LIME [8], Captum (for PyTorch), AIX360 (IBM) |

| Interpretable Model Packages | Computational Tool | Enables the development of inherently interpretable (ante hoc) models for comparison or final use. | InterpretML [8], scikit-learn (for GAMs, decision trees) |

| Clinical Datasets | Data Resource | Serves as benchmark data for training AI models and validating XAI methods in a clinically relevant context. | MIMIC-IV [2], The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), UK Biobank |

| Model & Data Cards Templates | Documentation Framework | Provides a structured format for documenting model characteristics, intended use, and limitations, aiding regulatory compliance. | Model Card Toolkit [10], Dataset Nutrition Label |

| Clinical User Interface (UI) Prototyping Tools | Design & Evaluation Tool | Facilitates the design and testing of how explanations are presented to clinicians within their workflow. | Figma, React.js with visualization libraries (D3.js) |

The regulatory landscape for AI in healthcare has irrevocably shifted from voluntary guidelines to legally binding obligations. The trajectory from GDPR to the EU AI Act establishes explainability as a non-negotiable requirement for clinical AI systems, particularly high-risk CDSS [9] [10]. For researchers and drug development professionals, this necessitates a fundamental integration of XAI principles into every stage of the AI lifecycle—from initial concept and data collection to model development, validation, and post-market surveillance [8].

Success in this new regulatory environment requires a proactive, interdisciplinary strategy. Technical teams must collaborate closely with clinical experts, legal advisors, and ethicists to ensure that XAI implementations are not only technically sound but also clinically meaningful and fully compliant [13]. The methodologies and frameworks outlined in this whitepaper provide a foundational roadmap. By prioritizing transparent model design, rigorous validation of explanations, and comprehensive documentation, the clinical AI research community can navigate these regulatory drivers effectively. This approach will not only ensure market access and legal compliance but, more importantly, build the trustworthy AI systems necessary to realize the full potential of AI in advancing human health.

The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) into Clinical Decision Support Systems (CDSS) represents a paradigm shift in modern healthcare, offering unprecedented capabilities for diagnostic precision, risk stratification, and treatment planning [2] [15]. Despite these advancements, a fundamental tension persists between developing highly accurate complex models and maintaining the clinical reliability essential for medical adoption [16] [17]. This trade-off between model complexity and clinical reliability constitutes a critical challenge in explainable AI (XAI) research for healthcare applications [8].

Clinical environments demand not only superior predictive performance but also transparency, interpretability, and accountability from AI systems [17]. The "black box" nature of many sophisticated machine learning algorithms, particularly deep neural networks, creates significant barriers to clinical implementation, as healthcare professionals remain justifiably reluctant to trust decisions without understanding their rationale [2] [18]. This whitepaper examines the multidimensional aspects of this fundamental trade-off, analyzes current XAI methodologies for bridging this gap, and provides experimental frameworks for evaluating AI systems in clinical contexts, with particular emphasis on their integration within CDSS research.

The Interpretability-Complexity Spectrum in Clinical AI

Defining the Spectrum

AI models in healthcare exist along a continuum from inherently interpretable designs to complex black-box approaches requiring post-hoc explanation. Interpretable models—including linear regression, decision trees, and Bayesian models—feature transparent internal logic that is readily understandable to human users [16] [17]. These ante hoc methods provide direct insight into their decision-making processes through clearly defined parameters or rule-based structures [8].

In contrast, complex models such as deep neural networks, ensemble methods, and gradient boosting machines achieve state-of-the-art predictive performance on many healthcare tasks but operate as "black boxes" with opaque internal workings [16] [19]. Their superior accuracy comes at the cost of interpretability, creating the central trade-off that XAI seeks to address through post-hoc explanation techniques [8].

The Clinical Imperative for Explainability

In high-stakes clinical environments, the demand for explainability extends beyond technical preference to ethical, regulatory, and safety necessities [17]. Several critical factors drive this requirement:

- Trust and Adoption: Clinicians require understanding of AI reasoning to appropriately trust and utilize system recommendations [2] [18].

- Error Identification: Explanation capabilities enable detection of model errors, spurious correlations, and inappropriate feature dependencies [16] [17].

- Bias Detection: Transparent models facilitate identification of dataset biases that could lead to discriminatory outcomes [20] [17].

- Regulatory Compliance: Emerging regulations, including the European Union's Artificial Intelligence Act, increasingly mandate transparency for high-risk AI systems [17].

- Clinical Workflow Integration: Actionable AI insights must align with clinical reasoning processes and workflow requirements [18] [8].

Table 1: Core Dimensions of Clinical Reliability in AI Systems

| Dimension | Definition | Clinical Importance |

|---|---|---|

| Safety | Avoidance of harm to patients from AI-assisted care | Prevents diagnostic and treatment errors; minimizes adverse events [16] |

| Effectiveness | Delivery of care based on scientific evidence that maximizes desired outcomes | Ensures alignment with evidence-based guidelines; avoids overuse/underuse [16] |

| Fairness | Assurance that predictions are unbiased and non-discriminatory | Prevents reinforcement of healthcare disparities; promotes equitable care [20] [17] |

| Accountability | Clear assignment of responsibility for AI-driven decisions | Supports clinical responsibility and liability frameworks [2] |

| Actionability | Provision of clinically relevant and implementable insights | Enables effective intervention; supports clinical workflow integration [17] |

XAI Methodologies: Bridging the Complexity-Reliability Gap

Technical Approaches to Explainability

XAI methodologies can be systematically categorized based on their implementation approach, explanation scope, and model specificity [8]. The taxonomy includes:

Ante Hoc (Interpretable Models): These inherently transparent models include linear/logistic regression, decision trees, and Bayesian models [16] [8]. Their internal logic is transparent by design, making them suitable for lower-complexity tasks where interpretability is paramount [16].

Post Hoc Explanation Methods: Applied after model training, these techniques explain existing black-box models [8]. They are further categorized by:

- Model-Specific Methods: Techniques tailored to specific model architectures, such as activation analysis for neural networks or feature importance for tree-based models [16].

- Model-Agnostic Methods: Approaches applicable to any ML model, including LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations) and SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) [16] [8].

- Explanation Scope: Global explanations elucidate overall model behavior, while local explanations clarify individual predictions [8].

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of XAI Techniques in Clinical Applications

| XAI Method | Category | Clinical Use Cases | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SHAP | Post-hoc, model-agnostic | Risk prediction models (sepsis, ICU admission) [16] [2] | Unified approach based on game theory; consistent explanations [8] | Computational intensity; potential approximation errors [8] |

| LIME | Post-hoc, model-agnostic | Imaging recommendations, treatment planning [16] | Local fidelity; intuitive feature perturbation [8] | Instability across similar instances; synthetic neighborhood generation [8] |

| Grad-CAM | Post-hoc, model-specific | Medical imaging (X-rays, histology) [2] [15] | Visual explanations; precise localization [2] | Limited to CNN architectures; intermediate layer dependence [2] |

| Counterfactual Explanations | Post-hoc, model-agnostic | Clinical eligibility, treatment alternatives [16] [15] | Intuitive "what-if" scenarios; aligns with clinical reasoning [15] | Computational complexity; may generate unrealistic instances [8] |

| Decision Trees | Ante hoc, interpretable | Triage rules, patient segmentation [16] | Fully transparent logic; no explanation needed [16] | Limited complexity; potential performance ceiling [15] |

| Attention Mechanisms | Model-specific | Medical text processing, time-series data [2] [15] | Context-aware weighting; inherent interpretability [15] | May not reflect true model reasoning; approximation concerns [2] |

Experimental Validation Framework for Clinical XAI

Robust experimental validation is essential for assessing the real-world utility of XAI systems in clinical contexts. The following protocols provide methodological guidance for evaluating XAI implementations:

Protocol 1: Clinical Reasonableness Assessment

Objective: Quantify the clinical plausibility of XAI-generated explanations through expert review [8].

Methodology:

- Panel Recruitment: Convene a multidisciplinary panel of clinical domain experts (physicians, nurses, specialists) with relevant expertise [8].

- Explanation Evaluation: Present XAI explanations for a curated set of model predictions without revealing the underlying clinical cases.

- Rating Scale Implementation: Utilize a structured rating scale (1-5) assessing:

- Physiological plausibility of featured parameters

- Consistency with established medical knowledge

- Clinical actionability of the explanation

- Alignment with expected reasoning patterns [8]

- Statistical Analysis: Calculate inter-rater reliability and aggregate scores for explanation quality.

Outcome Measures: Mean clinical reasonableness score; percentage of explanations deemed clinically valid; identification of recurrent explanation patterns contradicting medical knowledge [17].

Protocol 2: Trust Calibration Measurement

Objective: Evaluate how XAI explanations influence clinician trust and reliance on AI recommendations [8].

Methodology:

- Simulated Clinical Encounter Design: Develop realistic clinical scenarios incorporating AI recommendations with explanations.

- Controlled Exposure: Randomize participants to receive either: (a) AI recommendation alone, (b) AI recommendation with XAI explanation, or (c) no AI support (control).

- Decision Task: Participants manage simulated cases and make treatment decisions.

- Trust Assessment: Measure trust through:

- Self-reported trust scales (0-10)

- Adherence rates to AI recommendations

- Time to decision completion

- Appropriate overrides of incorrect recommendations [8]

Outcome Measures: Trust calibration metrics; appropriate reliance index; identification of over-trust or under-trust patterns [17].

Protocol 3: Workflow Integration Efficiency

Objective: Assess the impact of XAI explanations on clinical workflow efficiency and cognitive load [8].

Methodology:

- Task Analysis: Map existing clinical workflows and identify integration points for XAI explanations.

- Usability Testing: Implement XAI systems in simulated clinical environments with representative tasks.

- Efficiency Metrics:

- Time to clinical decision

- Number of information sources consulted

- Subjective workload assessment (NASA-TLX)

- System usability scale (SUS) [8]

- Iterative Refinement: Use testing results to refine explanation presentation and integration.

Outcome Measures: Workflow efficiency metrics; usability scores; cognitive load assessment [8].

Case Studies: Navigating the Trade-Off in Clinical Practice

Sepsis Prediction in Critical Care

Sepsis recognition and management represents a clinically significant and computationally challenging domain where the reliability-complexity trade-off is prominently displayed [18]. Complex ensemble models and deep learning approaches demonstrate superior predictive performance for early sepsis detection but present significant explainability challenges [18] [17].

Implementation Example: Lauritsen et al. developed an XAI system providing early warnings for critical illnesses including sepsis, using SHAP values to explain individual risk predictions by highlighting contributing features such as abnormal laboratory values and comorbidities [17]. This approach enables clinicians to validate predictions against clinical context and recognize when models may be misled by outliers or missing data [16].

Clinical Impact: The integration of explainability transforms sepsis prediction from an alert system to a clinical reasoning tool, allowing clinicians to focus on modifiable factors and personalize interventions [17]. This demonstrates how appropriate XAI implementation can enhance both reliability and actionability without fundamentally compromising model complexity [16] [17].

Diagnostic Imaging Analysis

In medical imaging domains such as radiology and pathology, deep learning models have demonstrated diagnostic capabilities comparable to healthcare professionals but face significant translational barriers due to their black-box nature [2] [18].

Implementation Example: Grad-CAM (Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping) and similar visualization techniques generate heatmaps highlighting regions of interest in medical images that contribute most significantly to model predictions [2] [15]. This allows radiologists to verify that models focus on clinically relevant anatomical features rather than spurious correlations [17].

Validation Challenge: DeGrave et al. demonstrated that some deep learning models for COVID-19 pneumonia detection took "shortcuts" by relying on non-pathological features such as laterality markers or patient positioning rather than medically relevant pathology [17]. This underscores the critical importance of XAI validation in detecting potentially harmful model behaviors that would otherwise remain hidden in black-box systems [17].

Operational Workflow Optimization

Beyond direct clinical decision support, AI systems increasingly optimize operational aspects of healthcare delivery, including resource allocation, appointment scheduling, and length-of-stay prediction [16].

Implementation Example: Pall et al. applied feature importance methods to identify factors associated with drug shortages, enabling more resilient supply chain management [16]. Similarly, Shin et al. used SHAP explanations to identify drivers of outpatient wait times, supporting targeted process improvements [16].

Trade-off Consideration: In operational contexts where clinical risk is lower, the balance may shift toward increased model complexity despite explainability costs, though post-hoc explanations remain valuable for process validation and improvement [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Components for XAI Clinical Validation

| Research Component | Function | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|

| SHAP Library | Quantifies feature contribution to individual predictions | Python implementation for clinical risk models; provides unified feature importance values [16] [8] |

| LIME Framework | Generates local surrogate explanations | Model-agnostic explanations for treatment recommendation systems; creates interpretable local approximations [16] [8] |

| Grad-CAM Implementation | Produces visual explanations for convolutional neural networks | Medical image analysis; highlights diagnostically relevant regions in imaging data [2] [15] |

| Electronic Health Record (EHR) Simulators | Creates synthetic clinical data for controlled experimentation | Protocol development without patient risk; simulated sepsis cases for validation [17] |

| Clinical Assessment Scales | Quantifies expert evaluation of explanation quality | 5-point Likert scales for clinical reasonableness; structured evaluation frameworks [8] |

| Trust Calibration Metrics | Measures appropriate reliance on AI recommendations | Adherence rates to correct/incorrect suggestions; subjective trust assessments [8] |

| Workflow Integration Platforms | Embeds explanations within clinical information systems | EHR-integrated dashboards; context-aware explanation delivery [8] |

Future Directions and Research Agendas

The evolving landscape of XAI research suggests several promising directions for addressing the fundamental reliability-complexity trade-off:

Methodological Innovations

- Causal Explanation Frameworks: Moving beyond correlation-based explanations to causal relationships that better align with clinical reasoning processes [15].

- Concept-Based Explanations: Utilizing high-level clinical concepts (e.g., "consolidation" in radiology) rather than low-level features to enhance clinical relevance [15].

- Interactive Explanation Systems: Developing dialog-based interfaces that allow clinicians to interrogate models through iterative questioning [8].

- Longitudinal Validation: Implementing continuous monitoring systems to detect explanation drift and performance degradation over time [15].

Regulatory and Standardization Developments

The establishment of standardized evaluation metrics for XAI systems remains a critical challenge [17] [15]. Current research indicates growing recognition of the need for:

- Explanation Fidelity Metrics: Quantitative measures assessing how accurately explanations represent true model reasoning [8].

- Clinical Utility Standards: Domain-specific criteria for evaluating the practical usefulness of explanations in clinical contexts [8].

- Fairness Auditing Frameworks: Standardized approaches for detecting and mitigating biases in AI systems through explainability [17].

The fundamental trade-off between clinical reliability and model complexity represents a central challenge in healthcare AI that cannot be eliminated but can be strategically managed through thoughtful XAI implementation [16] [17]. The evolving landscape of explainability techniques provides a growing toolkit for making complex models more transparent, accountable, and clinically actionable without necessarily sacrificing predictive performance [8] [15].

Future progress in this domain requires continued interdisciplinary collaboration among computer scientists, clinicians, and regulatory bodies to develop explanation methodologies that genuinely enhance clinical understanding while respecting the constraints of healthcare workflows [18] [8]. By focusing on human-centered design principles and robust validation frameworks, the field can advance toward AI systems that offer not only superior predictive capabilities but also the transparency and trust required for meaningful clinical integration [8].

The ultimate goal is not to explain away complexity but to build bridges between sophisticated AI capabilities and clinical reasoning processes, creating collaborative systems where human expertise and artificial intelligence operate synergistically to improve patient care [18]. Through continued methodological innovation and rigorous clinical validation, XAI research promises to transform the fundamental trade-off between reliability and complexity from a barrier to adoption into a catalyst for more effective, trustworthy, and impactful healthcare AI systems [17] [15].

The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) into clinical decision support systems (CDSS) represents a paradigm shift in modern healthcare, offering unprecedented capabilities in diagnostic precision, risk stratification, and treatment planning [21]. Yet, the opaque "black-box" nature of many sophisticated AI models creates fundamental barriers to clinical adoption, particularly in high-stakes medical environments where understanding the rationale behind a decision is as crucial as the decision itself [22]. This has spurred intense focus on two interrelated concepts: interpretability and explainability. While these terms are often used interchangeably, they embody distinct technical and functional meanings within medical AI. Interpretability refers to the ability to observe a model's mechanics and understand the causal pathways without the need for external explanations, often associated with simpler, transparent models. Explainability (XAI) involves post-hoc techniques applied to complex models to make their outputs understandable to humans [22] [23].

The ultimate goal of both is to foster trust—defined as the clinician's attitude that the AI will help achieve their goals in situations characterized by uncertainty and vulnerability [24]. However, trust is not a monolithic concept; it is a complex psychological state built on transparency, reliability, and understanding, and it directly influences a critical behavioral outcome: reliance, which is the observable extent to which a clinician's decision is influenced by the AI [24]. This technical guide delineates these core concepts, frames them within CDSS research, and provides a scientific toolkit for their evaluation and implementation, drawing upon the most recent advancements in the field.

Conceptual Framework and Definitions

Distinguishing Interpretability and Explainability

In both research and clinical practice, precisely defining the scope of interpretability and explainability is essential for developing and evaluating AI systems.

Interpretability is a characteristic of a model itself, describing the degree to which a human can consistently predict the model's result from its input data and architectural design. Intrinsically interpretable models, such as decision trees, linear models, or rule-based systems, offer transparency by design. Their internal workings are accessible and comprehensible, allowing a user to trace the reasoning process from input to output [22].

Explainability is a characteristic of a system's interface and functionality. It encompasses the methods and techniques used to translate the operations of a complex, often uninterpretable "black-box" model (e.g., a deep neural network) into a format that is understandable and meaningful for a human user. Explainability is often achieved through post-hoc techniques that provide insights into the model's behavior without fully elucidating its internal mechanics [23].

The relationship between these concepts is foundational to trust. Interpretability can be seen as a direct path to trust, whereas explainability often constructs a bridge to trust when direct observation is impossible.

The Trust-Reliance Dynamic in Clinical Settings

Trust and reliance are related but distinct concepts that must be measured separately in clinical studies [24]. A clinician may report high trust in an system (an attitude) but demonstrate low reliance (a behavior) due to external factors like workflow constraints, or vice versa.

A crucial concept emerging from recent research is appropriate reliance—the ideal where clinicians rely on the model when it is correct and override it when it is incorrect [24]. This is behaviorally defined as:

- Appropriate Reliance: The participant relied on the model when it was more accurate, or did not rely on it when it was less accurate.

- Under-Reliance: The participant did not rely on the model when it was more accurate.

- Over-Reliance: The participant relied on the model when it was less accurate.

Achieving appropriate reliance is the hallmark of a well-designed and effectively integrated clinical AI system, as blind over-reliance on an inaccurate model can lead to negative clinical outcomes.

Empirical Evidence and Quantitative Insights

Recent studies highlight both the potential and the challenges of XAI in clinical practice. The following table synthesizes quantitative findings from recent experimental and review studies, illustrating the measurable impact of XAI on clinical performance and the current state of methodological applications.

Table 1: Quantitative Findings from Recent XAI Clinical and Review Studies

| Study Focus | Key Performance Metric | Result Without AI/XAI | Result With AI/XAI | Context & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gestational Age Estimation (Reader Study) [24] | Clinician Mean Absolute Error (MAE) | 23.5 days | Prediction Only: 15.7 daysPrediction + XAI: 14.3 days | XAI provided a non-significant further reduction. High individual variability in response to XAI. |

| Hybrid ML-XAI Framework (Technical Framework) [22] | Overall Model Accuracy | N/A | 99.2% | Framework predicted 5 diseases; high accuracy achieved with ensemble models (XGBoost, Random Forest). |

| XAI in CDSS (Meta-Analysis) [21] | Dominant XAI Method | N/A | Model-agnostic techniques (e.g., Grad-CAM, attention mechanisms) | Analysis of 62 studies (2018-2025). Highlights dominance in imaging and sequential data tasks. |

The empirical data reveals a nuanced picture. While the addition of XAI can improve clinical performance, as in the gestational age study where it reduced error, the effect is not always statistically significant and varies significantly between clinicians [24]. This underscores that the mere presence of an explanation is not a panacea. Furthermore, technical frameworks demonstrate that high predictive accuracy can be maintained while integrating explainability, addressing a common concern that interpretability comes at the cost of performance [22].

Table 2: Analysis of Appropriate Reliance from a Clinical Reader Study [24]

| Reliance Category | Behavioral Definition | Clinical Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Appropriate Reliance | Participant relied on the model when it was better, or did not when it was worse. | Optimal interaction; enhances human-AI team performance. |

| Under-Reliance | Participant did not rely on the model when it was better. | Potential under-utilization of a beneficial tool; lost opportunity for improved accuracy. |

| Over-Reliance | Participant relied on the model when it was worse. | Clinically dangerous; can propagate and amplify model errors. |

Experimental Protocols for Evaluating XAI

Robust evaluation is critical for advancing XAI research. The following protocols, derived from recent literature, provide a template for assessing XAI's impact in clinical settings.

Three-Stage Clinical Reader Study Protocol

This protocol, adapted from a study on gestational age estimation, is designed to isolate the effects of AI predictions and explanations on clinician decision-making [24].

Objective: To measure the impact of model predictions and model explanations on clinician trust, reliance, and performance (e.g., estimation accuracy). Materials: A set of de-identified medical cases (e.g., images, patient records); a trained AI model with explainability output; a platform for presenting cases and collecting clinician responses; pre- and post-study questionnaires. Procedure:

- Stage 1 - Baseline Performance: Participants review and make decisions on a series of cases without any AI assistance. This establishes their baseline performance.

- Stage 2 - Prediction Influence: Participants review the same or a matched set of cases, now accompanied by the AI model's prediction. This stage measures the change in performance and reliance attributable to the prediction alone.

- Stage 3 - Explanation Influence: Participants review cases accompanied by both the AI model's prediction and its explanation (e.g., saliency map, prototype images). This stage measures the additional effect of the explanation.

- Data Collection: At each stage, collect: a) the participant's decision/estimate, b) time taken, c) self-reported confidence. In post-study questionnaires, gather qualitative feedback on perceived explanation usefulness and trust.

Analysis:

- Calculate performance metrics (e.g., Mean Absolute Error, accuracy) for each stage and compare.

- Quantify reliance by measuring the shift in the participant's decision toward the AI's prediction.

- Categorize each decision as appropriate reliance, over-reliance, or under-reliance based on the relative accuracy of the participant's baseline and the AI model for that specific case [24].

- Correlate questionnaire responses with performance changes to understand subjective vs. objective impacts.

Technical Framework for a Hybrid ML-XAI System

This protocol outlines the development of a hybrid system that combines high-performance models with post-hoc explainability, as demonstrated in a multi-disease prediction framework [22].

Objective: To build a predictive model for clinical risk (e.g., disease presence) that provides transparent, actionable explanations for its outputs. Materials: Structured clinical data (e.g., EHRs, lab results); ML libraries (e.g., scikit-learn, XGBoost); XAI libraries (e.g., SHAP, LIME). Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing: Handle missing values, normalize numerical features, and encode categorical variables. Address class imbalance using techniques like SMOTE if necessary.

- Model Training and Selection: Train multiple ML models (e.g., Decision Trees, Random Forest, XGBoost, Naive Bayes). Use cross-validation to select the best-performing model based on metrics like accuracy, AUC-ROC, and F1-score.

- Integration of XAI Techniques:

- Global Explainability: Apply SHAP to the entire dataset to understand the overall importance of each feature in the model's predictions. This identifies the key clinical drivers globally.

- Local Explainability: For an individual patient's prediction, use LIME or SHAP to generate a local explanation. This highlights the specific factors (e.g., elevated glucose, low RBC count) that most contributed to that particular risk assessment.

- Validation: Evaluate the model on a held-out test set. Validate the plausibility and clinical coherence of the explanations with domain experts.

Analysis:

- Report standard performance metrics for the chosen model.

- Present global feature importance plots.

- For case examples, present local explanations showing the contribution of each feature to the final prediction, allowing clinicians to "debug" the model's reasoning on a per-case basis.

Visualization of Logical Relationships and Workflows

The following diagrams, generated using Graphviz DOT language, map the core logical relationships in the XAI trust paradigm and the key experimental protocols.

The Pathway to Appropriate Clinical Reliance on AI

Three-Stage Clinical Evaluation Protocol

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

For researchers designing and evaluating interpretable and explainable AI systems for clinical support, the following tools and datasets are essential.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Resources for Medical XAI Research

| Category | Item | Specifications & Function | Example Sources/References |

|---|---|---|---|

| XAI Software Libraries | SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) | Model-agnostic unified framework for interpreting model predictions based on game theory. Provides both global and local explanations. | [22] |

| LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations) | Creates local surrogate models to approximate predictions of any black-box model, explaining individual instances. | [22] | |

| Captum | A comprehensive library for model interpretability built on PyTorch. | [25] [26] | |

| Medical Imaging Datasets | CheXpert | Large dataset of chest X-rays with labels for automated interpretation, used for training and benchmarking. | [27] |

| MedTrinity-25M | A massive dataset of 25M images across 10 modalities and 65+ diseases, enabling robust model training. | [28] | |

| Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) | Multimodal dataset including MRI/PET images, genetics, and cognitive tests for neurodegenerative disease research. | [27] | |

| Clinical Tabular Data | MIMIC Critical Care Database | De-identified health data from over 40,000 critical care patients, ideal for predictive model development. | [27] |

| Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) | Nationwide US database for tracking trends in healthcare utilization, access, charges, and outcomes. | [27] | |

| Evaluation Frameworks | Three-Stage Reader Study Protocol | A structured methodology to isolate and measure the impact of AI predictions and explanations on clinician performance and reliance. | [24] |

| Quantus | A Python toolkit for standardized evaluation of XAI methods, providing a range of metrics. | [25] [26] |

The journey toward fully transparent, trustworthy, and seamlessly integrated AI in clinical decision support is ongoing. The definitions, evidence, protocols, and tools outlined in this guide provide a foundation for researchers and drug development professionals to advance this critical field. The empirical data clearly shows that the relationship between explanations, trust, and reliance is complex and highly variable among clinicians [24]. Future research must move beyond technical explanations to develop context-aware, user-dependent XAI systems that engage in genuine dialogue with clinicians [25] [26]. This requires an interdisciplinary approach, combining technical rigor with deep clinical understanding and insights from human-computer interaction, to create AI systems that clinicians can not only trust but also appropriately rely upon, thereby fulfilling the promise of AI to enhance patient care and outcomes.

XAI Techniques in Action: From Model-Agnostic Tools to Clinical Workflow Integration

The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) into Clinical Decision Support Systems (CDSS) has significantly enhanced diagnostic precision, risk stratification, and treatment planning in modern healthcare [2]. However, the widespread clinical adoption of AI models has been hampered by their inherent "black-box" nature, where these systems provide predictions or classifications without offering clear, human-understandable explanations for their outputs [2] [29]. This opacity presents a critical barrier in medical contexts, where clinicians must justify decisions and ensure patient safety, creating an urgent need for Explainable AI (XAI) methodologies that make AI systems transparent, interpretable, and accountable [2] [30]. The fundamental challenge lies in the trade-off between model performance and interpretability; while complex models like deep neural networks offer superior predictive power, simpler models are inherently more understandable [2].

Explainable AI has emerged as a transformative approach to address these challenges, particularly in safety-critical healthcare domains where erroneous AI predictions can have high-impact consequences [30]. Regulatory bodies such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) are increasingly emphasizing the need for transparency and accountability in AI-based medical devices [2]. Furthermore, explainability supports core ethical principles of AI—fairness, accountability, and transparency (FAT)—while enabling informed consent, shared decision-making, and the ability to audit algorithmic decisions [2]. In clinical settings, XAI methods provide insights into which features influence a model's decision, how sensitive the model is to input variations, and how trustworthy its predictions are across different contexts [2].

This technical guide presents a comprehensive taxonomy of XAI methods, focusing specifically on the critical distinction between ante-hoc (intrinsically interpretable) and post-hoc (retrospectively applied) explanations, framed within the context of clinical decision support systems research. We examine the technical foundations, implementation considerations, and clinical applications of each approach, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a structured framework for selecting and implementing appropriate XAI methodologies in healthcare contexts.

Fundamental Taxonomy: Ante-Hoc vs. Post-Hoc Explainable AI

The rapidly expanding field of XAI can be fundamentally categorized into two distinct paradigms: ante-hoc (intrinsically interpretable) and post-hoc (retrospectively applied) explainability [31]. This distinction represents a core taxonomic division in XAI methodologies, with significant implications for their application in clinical decision support systems.

Ante-hoc explainability refers to AI systems that are inherently transparent by design. These models possess a self-explanatory architecture where the decision-making process is naturally interpretable to human users without requiring additional explanation techniques [31]. Examples include decision trees, linear models, rule-based systems, and attention mechanisms that provide inherent insights into feature importance during the reasoning process. The primary advantage of ante-hoc methods lies in their faithful representation of the actual model mechanics, as the explanations directly correspond to how the model processes information and generates predictions [29]. In healthcare contexts, this inherent transparency aligns well with regulatory requirements and clinical needs for trustworthy systems.

In contrast, post-hoc explainability encompasses techniques applied to already-trained "black-box" models to generate explanations for their specific predictions after the fact [31]. These methods do not modify the underlying model architecture but instead create auxiliary explanations that help users understand the model's behavior. Common post-hoc approaches include model-agnostic methods like LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations) and SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations), as well as visualization techniques such as Grad-CAM (Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping) for convolutional neural networks [2] [32]. The survey by Gambetti et al. (2025) revealed that over 80% of XAI studies in clinical settings employ post-hoc, model-agnostic approaches, particularly SHAP and Grad-CAM [32].

The following table summarizes the core characteristics and trade-offs of these two XAI paradigms:

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Ante-Hoc vs. Post-Hoc XAI Methods

| Characteristic | Ante-Hoc Explainability | Post-Hoc Explainability |

|---|---|---|

| Interpretability Basis | Inherent model transparency | External explanation techniques |

| Model Flexibility | Limited to interpretable architectures | Compatible with any model type |

| Explanation Fidelity | High (direct representation) | Variable (approximation) |

| Implementation Complexity | Integrated during model design | Applied after model training |

| Common Techniques | Decision trees, linear models, attention mechanisms, rule-based systems | SHAP, LIME, Grad-CAM, surrogate models, counterfactual explanations |

| Clinical Trustworthiness | High (transparent mechanics) | Context-dependent (requires validation) |

| Performance Trade-off | Potential accuracy sacrifice for transparency | Maintains black-box performance |

| Regulatory Alignment | Strong (inherently auditable) | Requires additional validation |

The selection between ante-hoc and post-hoc approaches involves navigating critical trade-offs between model performance, explanation fidelity, and implementation complexity [31]. While post-hoc methods dominate current clinical applications due to their compatibility with high-performance models, ante-hoc methods offer compelling advantages for contexts requiring high transparency and regulatory compliance [2] [29].

Technical Specifications of XAI Methods

Ante-Hoc (Intrinsically Interpretable) Methods

Ante-hoc XAI methods encompass a range of AI systems designed with inherent transparency, where the model's structure and parameters directly provide insights into the decision-making process. In healthcare contexts, these methods align closely with clinical reasoning patterns, potentially facilitating smoother integration into clinical workflows.

Decision trees and rule-based systems represent one of the most established ante-hoc approaches in CDSS. These systems operate through a hierarchical structure of logical decisions that mirror clinical reasoning processes [29]. Knowledge-based CDSS often employ rule-based inference methodologies using evidential reasoning (RIMER), which are based on belief rule base (BRB) systems that set belief degrees to represent different types of uncertain knowledge [29]. Such systems have demonstrated effectiveness across various medical domains, including heart failure management, psychogenic pain assessment, tuberculosis diagnosis, and acute coronary syndrome [29]. The primary advantage of these systems is their explicit decision logic, which allows clinicians to trace exactly how specific patient characteristics lead to particular recommendations or predictions.

Attention mechanisms constitute another significant ante-hoc approach, particularly valuable for processing complex, multi-modal clinical data. These mechanisms enable models to dynamically weight the importance of different input features or data segments during processing, providing inherent insights into which elements most strongly influence the final prediction [2]. The resulting attention weights can be visualized to show clinicians which patient attributes, clinical measurements, or regions in medical images the model focuses on when making decisions. This capability is especially valuable in medical imaging applications, where attention maps can highlight anatomically relevant regions corresponding to pathological findings [2].

Bayesian networks offer a probabilistic framework for ante-hoc explainability that naturally represents uncertainty—a crucial aspect of clinical decision-making. These networks model conditional dependencies between variables through directed acyclic graphs, allowing clinicians to understand both the reasoning process and the uncertainty associated with predictions [29]. In healthcare applications, Bayesian networks have been deployed for liver disease diagnosis, breast cancer assessment, infectious disease monitoring, and diabetes management [29]. Their capacity for what-if analysis enables clinicians to investigate how changes in patient conditions might affect outcomes, supporting exploratory reasoning and treatment planning.

Post-Hoc (Retrospectively Applied) Explanation Methods

Post-hoc XAI methods generate explanations for pre-existing models without modifying their internal architecture. These techniques have gained significant traction in clinical settings due to their compatibility with high-performance black-box models.

Feature attribution methods represent the most prominent category of post-hoc explanations in healthcare. These techniques assign importance scores to input features, indicating their relative contribution to a model's prediction for a specific case [2]. SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) leverages game-theoretic principles to compute feature importance values that satisfy desirable mathematical properties, providing both local (individual prediction) and global (overall model behavior) explanations [2] [32]. In clinical practice, SHAP has been applied to explain risk predictions in cardiology by highlighting contributing factors from electronic health records [2]. Similarly, LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations) creates local surrogate models that approximate the black-box model's behavior in the vicinity of a specific prediction, generating explanations by perturbing input features and observing output changes [2].

Visual explanation techniques are particularly valuable for medical imaging applications. Grad-CAM (Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping) generates heatmaps that highlight regions in input images most influential in a model's decision, making it invaluable for domains like radiology, pathology, and dermatology [2] [32]. For instance, in tumor detection from histology images, Grad-CAM heatmaps can localize malignant regions and show overlapping areas with pathologist annotations, allowing radiologists to verify and validate the model's conclusions [2]. These visual explanations facilitate human-AI collaboration by enabling clinicians to quickly assess whether a model focuses on clinically relevant image regions.

Surrogate models represent another post-hoc approach where a simpler, interpretable model (such as a decision tree or linear model) is trained to approximate the predictions of a complex black-box model [30]. While these surrogates provide intuitive explanations, their fidelity to the original model's decision boundaries must be carefully evaluated [2]. The effectiveness of surrogate explanations depends on the complexity of the underlying model and the adequacy of the surrogate in capturing its behavior.

Table 2: Technical Specifications of Prominent XAI Methods in Clinical Applications

| XAI Method | Category | Explanation Mechanism | Clinical Applications | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decision Trees | Ante-hoc | Hierarchical decision rules | General CDSS, glaucoma, thyroid nodules [29] | High transparency, mirrors clinical reasoning | Limited complexity, potential overfitting |

| Attention Mechanisms | Ante-hoc | Feature importance weighting | Medical imaging, sequential data analysis [2] | Dynamic focus, preserves model performance | Partial explanation, requires interpretation |

| Bayesian Networks | Ante-hoc | Probabilistic dependency graphs | Liver disease, breast cancer, diabetes [29] | Natural uncertainty quantification | Complex construction, computational cost |

| SHAP | Post-hoc | Game-theoretic feature attribution | Cardiology, oncology, risk prediction [2] [32] | Strong theoretical foundation, consistent | Computational intensity, approximation error |

| LIME | Post-hoc | Local surrogate modeling | General CDSS, simulated data [2] | Model-agnostic, intuitive local explanations | Instability to perturbations, sampling artifacts |

| Grad-CAM | Post-hoc | Visual heatmap generation | Radiology, pathology, medical imaging [2] [32] | Intuitive visualizations, model-specific | Limited to CNN architectures, coarse localization |

Experimental Protocols and Evaluation Frameworks

Methodological Approaches for XAI Validation

Rigorous evaluation of XAI methods in clinical contexts requires multi-faceted assessment protocols that address both technical correctness and clinical utility. The validation framework must encompass quantitative metrics, human-centered evaluations, and clinical relevance assessments to ensure explanations meet the needs of healthcare stakeholders.

Technical evaluation metrics focus on quantifying explanation quality through computational measures. For feature attribution methods, common metrics include explanation fidelity (how well explanations represent the model's actual reasoning) and robustness (consistency of explanations under minor input perturbations) [2]. In imaging applications, techniques like Intersection over Union (IoU) are used to measure the spatial alignment between visual explanations (e.g., Grad-CAM heatmaps) and expert annotations (e.g., radiologist markings) [2]. Model performance metrics such as Area Under the Curve (AUC) remain important for ensuring that explainability enhancements do not compromise predictive accuracy, particularly in critical applications like sepsis prediction in ICU settings [2].

Human-centered evaluation represents a crucial dimension for assessing XAI effectiveness in clinical contexts. These studies typically involve clinicians evaluating explanations based on criteria such as comprehensibility, clinical plausibility, trustworthiness, and decision-making confidence [32] [33]. However, current studies often suffer from methodological limitations, with most employing small-scale clinician studies (typically fewer than 25 participants) that limit statistical power and generalizability [32]. More robust experimental designs incorporate longitudinal assessments and mixed-methods approaches combining quantitative measures with qualitative feedback to capture nuanced aspects of explanation utility in clinical workflows [2] [33].

Clinical workflow integration testing evaluates how effectively XAI systems function within actual clinical environments and electronic health record (EHR) systems. This includes assessing explanation delivery timing, presentation format compatibility with existing interfaces, and minimization of cognitive load [2] [33]. Studies have shown that explanations must be integrable into fast-paced clinical settings where, as one attending physician noted, "When [the system] gives me an elevated risk score, I must be able to see within minutes if [the results] make sense" [33]. Effective integration often requires context-aware explanations that adapt to different clinical scenarios, user roles, and time constraints.

Implementation Challenges and Methodological Gaps

Despite advances in XAI methodologies, significant implementation challenges persist in healthcare contexts. A critical gap exists between technical explanation generation and clinically meaningful interpretation, with developers and clinicians often possessing opposing mental models of explainability [33]. Developers typically focus on model interpretability—understanding what features the model uses—while clinicians prioritize clinical plausibility—whether results align with medical knowledge and specific patient contexts [33].

This disconnect manifests in several ways. Developers tend to regard data as the primary source of truth, trusting that "the model chose the most relevant factors to make accurate predictions," while clinicians view algorithmic outputs as "only one piece of the puzzle" to be combined with physical examination findings, patient history, and other non-quantifiable information [33]. Furthermore, tensions exist between exploration versus exploitation mindsets; developers value ML systems for discovering "unknown patterns in the data to learn something new," while clinicians typically trust only systems relying on "established knowledge gained from clinical studies and evidence-based medicine" [33].

Additional methodological challenges include the lack of standardized evaluation metrics for explanation quality, with current assessments often relying on researcher-defined criteria without consensus on what constitutes a "good" explanation across different clinical contexts [2]. There is also insufficient attention to population-specific validation, with many XAI systems failing to demonstrate consistent explanation quality across diverse patient demographics and clinical subgroups [2]. These gaps highlight the need for more sophisticated, clinically-grounded evaluation frameworks that address the unique requirements of healthcare applications.

Visual Representations of XAI Methodologies

The following diagrams provide visual representations of key XAI workflows and methodological relationships, created using Graphviz DOT language with adherence to the specified color palette and contrast requirements.

Diagram 1: Ante-Hoc XAI Workflow

Diagram 2: Post-Hoc XAI Workflow

Implementing and evaluating XAI methods in clinical contexts requires specialized computational resources, software tools, and datasets. The following table details key "research reagent solutions" essential for conducting rigorous XAI research in healthcare settings.

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for XAI in Clinical Decision Support

| Resource Category | Specific Tools & Platforms | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| XAI Algorithm Libraries | SHAP, LIME, Captum, InterpretML, AIX360 | Implementation of explanation algorithms | Model-agnostic and model-specific explanation generation |