Exclusion Volumes in Pharmacophore Modeling: A Guide to Enhancing Virtual Screening Accuracy

This article provides a comprehensive overview of exclusion volumes, the critical steric constraints in pharmacophore modeling that represent regions of space forbidden to ligands due to the physical presence of...

Exclusion Volumes in Pharmacophore Modeling: A Guide to Enhancing Virtual Screening Accuracy

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of exclusion volumes, the critical steric constraints in pharmacophore modeling that represent regions of space forbidden to ligands due to the physical presence of the binding site. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational definition and geometric representation of exclusion volumes, methods for their generation from both protein structures and ligand data, strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing model performance, and techniques for rigorous validation. By synthesizing current methodologies and applications, this guide serves as a vital resource for improving the precision and success rate of virtual screening campaigns in computer-aided drug design.

What Are Exclusion Volumes? Defining the Essential Steric Constraints in Pharmacophore Models

The IUPAC Concept and Spatial Role of Exclusion Volumes

In pharmacophore modeling, the exclusion volume is a critical steric constraint feature that defines regions in space where a ligand must not occupy for successful binding to a biological target. According to the official International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) definition, a pharmacophore is "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or to block) its biological response" [1] [2] [3]. Exclusion volumes directly contribute to this "steric and electronic" ensemble by representing the spatial constraints imposed by the shape of the binding site [1].

Exclusion volumes are not merely auxiliary components but are fundamental to accurately modeling the three-dimensional binding cavity. They are typically represented as spheres of different sizes that designate receptor areas the ligand is forbidden to occupy after alignment with the pharmacophore [1]. The most reliable information for defining these volumes comes from X-ray structures of ligand-receptor complexes, which provide atomic-level detail of the binding site geometry [1]. When such structural information is unavailable, exclusion volumes can be assigned manually or through computational methods that distribute spheres based on the union of molecular shapes from aligned known active compounds [1].

Methodological Approaches for Defining Exclusion Volumes

Structure-Based Definition from Macromolecular Complexes

The most direct method for defining exclusion volumes involves analyzing experimentally determined protein-ligand complexes from sources like the Protein Data Bank (PDB) [1] [3]. In this structure-based approach, the protein structure is prepared by evaluating residue protonation states, hydrogen atom positions, and overall structural quality [4]. The binding site is then characterized, and exclusion volume spheres are placed to represent the van der Waals surfaces of protein atoms that line the binding cavity but do not participate in favorable interactions with the ligand [1] [5].

Software Implementation: Tools like LigandScout and Discovery Studio can automatically generate exclusion volumes from protein-ligand complexes by analyzing atomic coordinates and identifying regions where ligand atoms would experience steric clashes [5] [3]. These programs typically represent exclusion volumes as spheres whose sizes correspond to the atomic radii of the protein atoms in the binding site.

Ligand-Based Definition from Active Compound Alignments

When the 3D structure of the target is unavailable, exclusion volumes can be derived through ligand-based approaches [1]. This method requires a sufficient number of known active ligands that bind to the same receptor site in the same orientation [1]. The molecular shapes of these aligned active compounds are analyzed, and exclusion volumes are generated to represent regions not occupied by any of the active molecules, under the assumption that these regions would cause steric clashes with the receptor [1] [6].

Software Implementation: The HypoGenRefine algorithm in Catalyst can automatically generate exclusion volumes from ligand information alone, adding these features to pharmacophore models to account for steric effects on activity [6]. This approach penalizes molecules occupying steric regions not occupied by active molecules, thereby improving model selectivity [6].

Advanced Shape-Focused Modeling Techniques

Recent methodological advances have introduced more sophisticated approaches for representing binding site constraints. The O-LAP algorithm generates shape-focused pharmacophore models through pairwise distance graph clustering of overlapping atomic content from flexibly docked active ligands [7]. This method fills the target protein cavity with docked ligands and clusters overlapping atoms to create representative centroids, effectively capturing the binding site shape without explicitly defining exclusion volumes [7].

Table 1: Comparison of Exclusion Volume Definition Methods

| Method | Data Requirements | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structure-Based from Complexes | High-resolution protein-ligand complex (e.g., from PDB) | High accuracy; Direct representation of true binding site | Requires experimental structure; May not account for flexibility |

| Ligand-Based from Actives | Multiple known active compounds with common binding mode | No protein structure needed; Captures essential steric constraints | Dependent on quality and diversity of active compounds |

| Shape-Focused Clustering (O-LAP) | Top-ranked poses of flexibly docked active ligands | Enriches docking performance; Works in rigid docking | Complex implementation; Computationally intensive |

Quantitative Impact on Virtual Screening Performance

Enhancement of Enrichment and Selectivity

The incorporation of exclusion volumes significantly improves virtual screening performance by reducing false positives and increasing enrichment rates. A study on CDK2 and human DHFR demonstrated that automated refinement of pharmacophore models with exclusion volume features provided more selective models that effectively reduced false positives and improved enrichment in virtual screening [6]. The exclusion volumes penalize molecules occupying steric regions not occupied by active molecules, thereby accounting for steric effects on activity that would otherwise remain unaddressed by pharmacophore features alone [6].

In a separate study targeting the XIAP protein, a structure-based pharmacophore model was generated containing 15 exclusion volume features in addition to various chemical features [5]. The model demonstrated exceptional performance in validation, achieving an early enrichment factor (EF1%) of 10.0 with an area under the ROC curve (AUC) value of 0.98 at the 1% threshold, confirming its ability to distinguish true actives from decoy compounds [5]. This high level of discriminative power relies heavily on the exclusion volumes to eliminate compounds that might otherwise fit the chemical features but would experience steric clashes in the binding site.

Case Study: Akt2 Inhibitor Screening

A research campaign for novel Akt2 inhibitors developed a structure-based pharmacophore hypothesis (PharA) containing seven pharmacophoric features and eighteen exclusion volume spheres [8]. The exclusion volumes were strategically placed around important active site residues to represent spatial restrictions. When validated using a decoy set containing 1980 molecules with unknown activity and 20 known active compounds, the model demonstrated significant enrichment, confirming that the exclusion volumes effectively filtered out compounds that would experience steric hindrance while retaining true binders [8].

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Pharmacophore Models with Exclusion Volumes

| Study Target | Exclusion Volume Count | Key Performance Metrics | Impact on Screening |

|---|---|---|---|

| XIAP Protein [5] | 15 exclusion volumes | EF1% = 10.0; AUC = 0.98 | Excellent active/inactive separation |

| Akt2 Kinase [8] | 18 exclusion volume spheres | Significant enrichment in decoy set | Effective false positive reduction |

| CDK2/DHFR [6] | Not specified | Improved selectivity and enrichment | Reduced false positives |

Experimental Protocols for Implementation

Structure-Based Protocol Using Protein-Ligand Complex

Objective: To generate a pharmacophore model with exclusion volumes from a protein-ligand complex structure.

Required Materials and Software:

- Protein Data Bank (PDB) structure of target with bound ligand [4] [5]

- Molecular visualization software (e.g., Discovery Studio, LigandScout) [5] [3]

- Protein preparation tools for adding hydrogen atoms, assigning protonation states, and energy minimization [4]

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Retrieve and Prepare Protein Structure: Obtain the 3D structure from PDB and preprocess it by adding hydrogen atoms, correcting protonation states of residues, and performing energy minimization to ensure structural quality [4].

- Define Binding Site: Identify the ligand binding site, either manually by selecting residues within the cavity or using automated binding site detection tools available in software packages [4] [3].

- Generate Pharmacophore Features: Extract chemical features (hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic areas, etc.) from the protein-ligand interaction pattern [5] [3].

- Add Exclusion Volumes: Automatically or manually place exclusion volume spheres representing the van der Waals surfaces of protein atoms in the binding site that do not interact favorably with the ligand [1] [5].

- Refine Model: Remove redundant features and adjust exclusion volume sizes based on protein atom types and known structure-activity relationships [5] [3].

- Validate Model: Test the model using known active and inactive compounds to verify its ability to discriminate true binders [5] [3].

Ligand-Based Protocol Using Known Active Compounds

Objective: To develop a pharmacophore model with exclusion volumes using only known active ligands.

Required Materials and Software:

- Set of known active compounds with demonstrated binding to the target [1] [3]

- Conformational analysis software to generate biologically relevant 3D conformations [3]

- Pharmacophore generation platform with exclusion volume capabilities (e.g., Catalyst/HypoGen) [6]

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Select Training Set Compounds: Curate a set of structurally diverse known active compounds that bind to the same site with the same mode [1] [3].

- Generate Conformational Models: Create comprehensive conformational ensembles for each compound, ensuring coverage of potential bioactive conformations [3].

- Align Compounds: Superimpose the compounds based on their common pharmacophoric features [1] [3].

- Identify Common Features: Determine the chemical features shared among the aligned active compounds [3].

- Define Exclusion Volumes: Generate exclusion volumes based on regions outside the union of molecular volumes of the aligned active compounds, representing areas that would cause steric clashes with the target [1] [6].

- Apply Steric Refinement: Use algorithms like HypoGenRefine to automatically add and optimize exclusion volumes based on activity data [6].

- Validate with Inactives: Test the model with known inactive compounds to verify its selectivity [3].

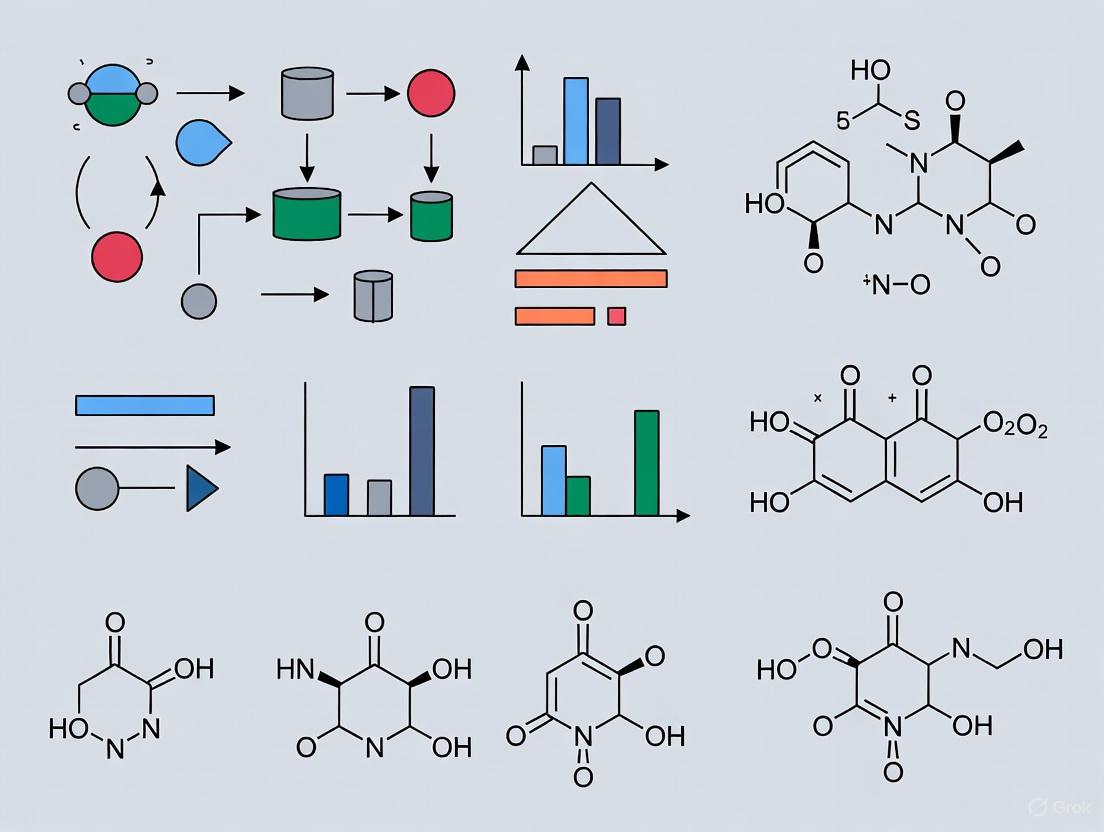

Workflow for Implementing Exclusion Volumes in Pharmacophore Modeling

Research Reagent Solutions for Exclusion Volume Implementation

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Exclusion Volume Implementation

| Tool/Software | Type | Primary Function | Exclusion Volume Capabilities |

|---|---|---|---|

| LigandScout [5] [3] | Software Platform | Structure- and ligand-based pharmacophore modeling | Automatic exclusion volume generation from protein-ligand complexes |

| Discovery Studio [3] [8] | Software Platform | Comprehensive drug discovery suite | Manual and automated exclusion volume placement; Binding site analysis |

| Catalyst/HypoGen [6] | Algorithm | Pharmacophore generation and refinement | HypoGenRefine for automated exclusion volume addition from ligand data |

| O-LAP [7] | Algorithm | Shape-focused pharmacophore modeling | Graph clustering of docked ligands to implicit shape constraints |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) [4] [3] | Database | Repository of 3D protein structures | Source of protein-ligand complexes for structure-based approaches |

| DUD-E [5] [3] | Database | Directory of Useful Decoys | Source of decoy molecules for model validation and enrichment calculation |

Exclusion volumes transform abstract pharmacophore models into spatially accurate representations of binding sites by explicitly defining forbidden regions where ligand atoms cannot reside. Their implementation significantly enhances virtual screening outcomes by reducing false positives that might otherwise satisfy electronic and hydrogen-bonding feature requirements but would experience steric clashes in the actual binding site [6] [5]. As pharmacophore modeling continues to evolve, particularly with shape-focused approaches like O-LAP that implicitly incorporate spatial constraints [7], the fundamental role of exclusion volumes remains central to creating predictive models that accurately reflect the steric realities of molecular recognition. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastery of exclusion volume implementation represents a critical competency in structure-based drug design, enabling more efficient identification of viable lead compounds with reduced potential for steric incompatibility.

In the realm of computer-aided drug design, pharmacophore models abstract the essential steric and electronic features necessary for a molecule to interact with a biological target [4]. A critical, yet sometimes overlooked, component of these models is the exclusion volume sphere, also known as forbidden space. These spheres represent regions in three-dimensional space that a ligand must avoid to ensure productive binding, effectively modeling the steric constraints imposed by the protein's binding site [9] [8]. The inclusion of these volumes is paramount for enhancing the selectivity and predictive accuracy of structure-based pharmacophore models, as they encode the negative image of the protein's shape, guiding virtual screening toward ligands that fit the binding pocket both geometrically and chemically [7].

This technical guide delves into the core principles, quantitative parameters, and methodological protocols for implementing exclusion volumes within pharmacophore modeling. Framed within broader research on pharmacophore efficiency, it provides drug development professionals with a comprehensive resource for leveraging these forbidden spaces to improve virtual screening outcomes.

Geometric and Energetic Principles of Forbidden Spheres

Fundamental Geometric Representation

Exclusion volumes are geometrically represented as spheres that define forbidden space. When a pharmacophore model is generated from a protein-ligand complex, these spheres are strategically placed in the binding site to represent the van der Waals radii of protein atoms that are not directly involved in favorable interactions with a ligand [10] [8]. The underlying principle is straightforward: any atom from a screened ligand that intersects these spherical volumes is subject to a significant steric penalty, as it would clash with the protein structure in a real binding scenario.

The core geometric principle is one of complementarity. While traditional pharmacophore features (e.g., hydrogen bond donors, hydrophobic areas) define where ligand atoms should be, exclusion volumes define where ligand atoms cannot be. This creates a more complete negative image of the binding site, leading to more accurate virtual screening [7].

Energetic and Functional Role

The primary functional role of exclusion volumes is to penalize steric clashes. In computational terms, a ligand pose that overlaps with an exclusion volume sphere is typically assigned a poor score or filtered out entirely during virtual screening [11]. This process mimics the repulsive van der Waals forces that would dominate in a real physical interaction, preventing the selection of ligands that are sterically incompatible with the target.

Incorporating these forbidden spaces is particularly crucial for distinguishing between true active compounds and decoy molecules that may possess the necessary chemical features but lack the appropriate shape and size to fit the binding pocket without clashes [8]. This significantly improves the enrichment factor in virtual screening campaigns.

Quantitative Characterization of Exclusion Volumes

The effective implementation of exclusion volumes requires careful consideration of several quantitative parameters. The table below summarizes the key characteristics and their typical values or functions.

Table 1: Quantitative Parameters for Exclusion Volume Spheres in Pharmacophore Modeling

| Parameter | Description | Typical Value/Function |

|---|---|---|

| Sphere Radius | Defines the spatial extent of the forbidden volume around a protein atom. | Often set to the van der Waals radius of the respective protein atom (e.g., ~1.5-2.0 Å for carbon) [11]. |

| Placement | The 3D coordinates of the sphere's center. | Typically centered on the coordinates of non-interacting protein atoms in the binding site [8]. |

| Score Penalty | The energetic penalty applied when a ligand atom infringes upon the sphere. | High-value penalty in scoring functions; often results in direct pose rejection [9]. |

| Influence on Specificity | Impact on a model's ability to reject inactive decoys. | High; critical for improving the enrichment factor (EF) in virtual screening [8]. |

Methodological Workflows for Implementing Exclusion Volumes

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

The most common method for incorporating exclusion volumes involves a structure-based approach, where the 3D structure of a protein, often in complex with a ligand, is used as a template.

Table 2: Experimental Protocol for Structure-Based Exclusion Volume Generation

| Step | Protocol Description | Tools & Techniques |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Protein Preparation | Obtain a high-resolution 3D structure (e.g., from PDB). Add hydrogen atoms, assign protonation states, and optimize the structure energetically. | PDB Database, ChimeraX, DS (Discovery Studio), MOE [12] [8]. |

| 2. Binding Site Definition | Define the spatial boundaries of the ligand-binding site, typically as a sphere centered on a co-crystallized ligand. | Binding Site tool in DS, SiteMap, or manual selection based on known active site residues [4] [8]. |

| 3. Interaction Analysis | Identify protein atoms that form specific interactions (H-bond, hydrophobic) with a bound ligand. These are assigned to complementary pharmacophore features. | Interaction Generation protocol in DS, LigandScout [10] [8]. |

| 4. Exclusion Volume Placement | Place exclusion volume spheres on protein atoms within the binding site that do not participate in favorable interactions with the ligand. | Edit and Cluster pharmacophores tool in DS; automated in tools like LigandScout [8]. |

| 5. Model Validation | Validate the complete model (features + exclusion volumes) using test sets of known active and decoy compounds to assess enrichment. | Decoy set validation (e.g., DUD-E); calculation of Enrichment Factor (EF) [8]. |

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key steps in creating a structure-based pharmacophore model with exclusion volumes.

Advanced and Emerging Methods

Beyond traditional structure-based approaches, advanced methods dynamically define forbidden space.

- Water-Based Pharmacophore Modeling: This ligand-independent strategy uses molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of explicit water molecules in apo (ligand-free) binding sites. The dynamics of water clusters help map out both favorable interaction hotspots and steric constraints, which can be translated into pharmacophore features and exclusion volumes [12].

- Shape-Focused Modeling (O-LAP): Algorithms like O-LAP generate cavity-filling models by clustering overlapping atoms from docked active ligands. This process creates a shape-focused pharmacophore that inherently accounts for the steric boundaries of the pocket, which can be used similarly to exclusion volumes for docking rescoring [7].

- AI-Enhanced Approaches: Deep learning frameworks, such as DiffPhore, are beginning to incorporate pharmacophore constraints, including spatial restrictions, to guide the generation of ligand binding conformations. These models learn the implicit rules of forbidden space from training on 3D ligand-pharmacophore pairs [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Successful implementation of exclusion volumes relies on a suite of specialized software tools.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Exclusion Volume Modeling

| Tool/Reagent | Type | Primary Function in Exclusion Volume Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| Discovery Studio (DS) | Commercial Software | Provides integrated workflows for generating structure-based pharmacophores, including automated placement of exclusion volumes [8]. |

| LigandScout | Commercial Software | Advanced tool for creating structure- and ligand-based pharmacophores from protein-ligand complexes, with precise exclusion volume handling [10] [11]. |

| MOE | Commercial Software | A comprehensive molecular modeling environment with modules for pharmacophore model development and analysis [10] [11]. |

| PHARMIT | Web Server / Open Source | An interactive virtual screening platform that allows users to define and apply exclusion volumes (as part of shape constraints) in pharmacophore searches [11]. |

| O-LAP | Open Source Algorithm | Generates shape-focused pharmacophore models by clustering overlapping ligand atoms, defining steric constraints for docking rescoring [7]. |

| PyRod | Open Source Tool | Converts dynamic molecular interaction fields (dMIFs) from water-based MD simulations into pharmacophore features, potentially including exclusion constraints [12]. |

Exclusion volume spheres are indispensable components of modern, high-fidelity pharmacophore models. By providing a geometric representation of forbidden space, they translate the physical reality of steric hindrance into a computationally tractable form. The rigorous methodological protocols for their placement, combined with quantitative characterization and supported by a robust toolkit of software, enable researchers to create highly selective models. As the field evolves with advancements in MD simulations, shape-based clustering, and artificial intelligence, the precision and utility of these "forbidden spheres" will only increase, solidifying their critical role in the rational design of novel therapeutic agents.

In structure-based drug design, achieving shape complementarity between a ligand and its target protein is a fundamental principle for achieving high affinity and selectivity. The binding site of a protein is not a featureless void but a complex three-dimensional landscape with a unique topology and chemical character. Steric clashes—the repulsive forces that occur when atoms of the ligand and protein occupy the same space—can dramatically reduce binding affinity or prevent it entirely. Exclusion volumes (Xvols), a key feature in modern pharmacophore modeling, provide a computational solution to this challenge by explicitly defining the spatial regions forbidden to a ligand, thereby enforcing shape mimicry. Within the broader thesis of pharmacophore research, exclusion volumes represent the direct translation of protein steric constraints into a ligand design framework, ensuring that proposed compounds not only possess the necessary interacting chemical features but also conform to the physical shape of the binding pocket. This guide details the biological rationale, methodological implementation, and practical application of these critical features.

Core Concepts: Exclusion Volumes and the Energetics of Binding

Defining Exclusion Volumes in a Pharmacophore Context

A pharmacophore is defined as "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target and to trigger (or block) its biological response" [14]. Traditionally, this model focuses on positive chemical features like hydrogen bond donors/acceptors and hydrophobic regions. Exclusion volumes (also known as excluded volumes or steric constraints) complement these positive features by adding negative spatial constraints.

- Function: They are 3D entities, typically spheres, placed within a pharmacophore model to represent regions in space that are occupied by the protein's atoms and are therefore unavailable for ligand atoms to occupy [5] [14].

- Biological Rationale: Each exclusion volume symbolizes the van der Waals radius of a protein atom in the binding site. During virtual screening or ligand optimization, any proposed compound whose atoms intrude into these defined volumes is penalized, as this would indicate a steric clash in a real binding scenario [5] [7].

- Theoretical Foundation: The concept is grounded in the Pauli exclusion principle, which states that two atoms cannot be in the same quantum state at the same location. In practical terms, this translates to a steep repulsive energy when the electron clouds of two non-bonded atoms overlap.

The Energetic Cost of Steric Clashes

Steric clashes inflict a severe energetic penalty on the binding free energy (ΔG) of a protein-ligand complex. The relationship between atomic overlap and energy is described by potential functions like the Lennard-Jones potential. When a ligand atom is forced into a space already occupied by a protein atom, the resulting repulsive interaction can easily outweigh favorable interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic effects), rendering the ligand inactive. By incorporating exclusion volumes, pharmacophore models preemptively filter out compounds prone to such clashes, leading to a much higher success rate in virtual screening [7].

Table 1: Key Components of a Shape-Aware Pharmacophore Model

| Component Type | Description | Role in Preventing Steric Clashes |

|---|---|---|

| Positive Features | Hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic centers, charged groups. | Defines favorable interactions required for biological activity. |

| Exclusion Volumes (Xvols) | Spheres representing occupied space by protein atoms. | Defines forbidden regions for ligand atoms to prevent repulsive interactions [5] [14]. |

| Shape Constraints | Negative image-based (NIB) models or shape-focused pharmacophores. | Provides a continuous 3D definition of the binding cavity's void space [7]. |

Methodological Approaches: Incorporating Shape into Pharmacophore Models

Structure-Based Generation of Exclusion Volumes

The most direct method for generating exclusion volumes relies on the 3D structure of the target protein, typically obtained from X-ray crystallography, NMR, or cryo-EM.

Protocol: Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling with Exclusion Volumes

- Protein Preparation: Obtain a 3D structure of the target protein (e.g., from the Protein Data Bank, PDB). Prepare the structure by adding hydrogen atoms, assigning correct protonation states, and optimizing side-chain conformations using tools like ChimeraX or Schrödinger's Protein Preparation Wizard [12] [5].

- Binding Site Analysis: Define the spatial coordinates of the binding site, often based on the location of a co-crystallized native ligand or a known catalytic residue.

- Feature and Exclusion Volume Mapping: Use software such as LigandScout to analyze the protein's binding site [5]. The algorithm will:

- Identify key chemical features (hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic patches, etc.).

- Place exclusion volumes onto the coordinates of protein atoms lining the binding pocket. These volumes represent the van der Waals surfaces of the protein, creating a negative image of the cavity [5].

- Model Refinement: The initial model may be refined by adjusting the radii of exclusion volumes or removing volumes in flexible regions to allow for some induced fit.

Advanced and Ligand-Based Techniques

When a protein structure is unavailable, or to incorporate dynamic information, alternative methods are employed.

- Ligand-Based Shape Similarity: This approach uses the 3D shape of a known active ligand as a template. Tools like ROCS (Rapid Overlay of Chemical Structures) screen compound libraries for molecules with similar shape and chemistry [7]. The shape of the active ligand implicitly encodes the complementary shape of the binding site.

- Dynamic and Water-Based Pharmacophores: Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of the apo (ligand-free) protein can be used to generate more robust models. For instance, simulations of water-filled binding sites can map interaction "hotspots," and the resulting pharmacophores can include exclusion volumes derived from the average protein structure during the simulation, capturing the dynamic nature of the pocket [12].

- Negative Image-Based (NIB) Modeling: This method explicitly focuses on shape. It involves creating a pseudo-ligand composed of atoms or spheres that fill the protein's binding cavity, effectively creating a positive model of the cavity's void space [7]. Screening is then performed by comparing ligand shapes to this negative image.

Diagram 1: Workflow for generating shape-aware pharmacophore models, integrating both structure-based and ligand-based approaches.

Experimental Protocols and Validation

Detailed Protocol: Structure-Based Modeling with Exclusion Volumes

This protocol is adapted from studies on targets like the XIAP protein and Janus kinases [5] [14].

A. Reagents and Software Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Structure-Based Modeling

| Item / Software | Function / Description | Example Tools |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Structure | The 3D template for model generation. | PDB Database (RCSB) |

| Structure Prep Tool | Adds hydrogens, corrects residues, optimizes H-bond networks. | ChimeraX, Schrödinger Protein Prep Wizard, MOE |

| Pharmacophore Modeling Suite | Generates chemical features and exclusion volumes from the prepared structure. | LigandScout [5], MOE, Discovery Studio |

| Virtual Screening Platform | Screens compound libraries against the generated pharmacophore model. | PHASE, Catalyst, Pharmit [13] |

B. Step-by-Step Procedure

- Retrieve and Prepare Protein Structure: Download a high-resolution crystal structure (e.g., PDB ID: 5OQW for XIAP) [5]. Remove water molecules and co-crystallized ligands, then add hydrogen atoms using standard protonation states at pH 7.4. Energy minimization may be performed to relieve minor steric strain.

- Define the Binding Site: The binding site can be defined using the coordinates of the original ligand or by specifying a 3D grid around key catalytic residues.

- Generate the Pharmacophore Model: In LigandScout, use the "Create Pharmacophore from Protein" function. The software will automatically identify interaction features (hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions, etc.) and add exclusion volumes based on the protein's van der Waals surface within the binding site.

- Validate the Model: Critical step to ensure model quality.

- Decoy Set Validation: Use a dataset containing known active compounds and property-matched inactive decoys (e.g., from DUD-E) [5]. Screen this dataset.

- Calculate Enrichment Metrics: Generate a Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve and calculate the Area Under the Curve (AUC). A perfect model has an AUC of 1.0. Also, calculate the Enrichment Factor (EF), which measures the concentration of actives in the top ranks of the screening results. A good model should have an AUC > 0.7 and a high EF1% (enrichment in the top 1% of the screened database) [5].

Case Study: Validation of an XIAP Pharmacophore Model

A study targeting the XIAP protein for cancer therapy created a structure-based pharmacophore model from a crystal structure (PDB: 5OQW). The initial model contained 14 chemical features and 15 exclusion volumes [5]. Upon validation with 10 known active inhibitors and 5199 decoy molecules, the model demonstrated an excellent AUC value of 0.98 and an early enrichment factor (EF1%) of 10.0. This signifies that active compounds were 10 times more concentrated in the top 1% of the screening hits than in a random distribution, proving the model's powerful ability to discriminate actives from inactives, a capability heavily dependent on the accurate placement of exclusion volumes to filter out non-binders [5].

Implementation in Virtual Screening and Lead Optimization

The primary application of exclusion volume-integrated pharmacophores is in virtual screening, where they drastically improve the quality of hits.

- Tiered Screening Workflow: A common strategy is to use the pharmacophore as a filter. Large compound libraries (e.g., ZINC, Enamine) are first screened for molecules that match the positive chemical features of the pharmacophore. The resulting hits are then subjected to a second filtering step where compounds that clash with the exclusion volumes are removed. This two-tiered process efficiently eliminates non-binders with poor shape fit before more computationally expensive methods like molecular docking are applied [5] [7].

- Integration with Docking and MD: Pharmacophore models with exclusion volumes can be used as post-docking filters to remove poses that sterically clash with the protein. Furthermore, they can inform lead optimization by highlighting regions of the molecule where bulk cannot be added, guiding medicinal chemists to make modifications that improve potency without introducing clashes.

Table 3: Impact of Exclusion Volumes on Virtual Screening Performance

| Target Protein | Screening Method | Key Finding Related to Shape/Exclusion Volumes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| XIAP | Structure-based pharmacophore (LigandScout) | Model with 15 exclusion volumes achieved an EF1% of 10.0, showing high selectivity for true actives. | [5] |

| Multiple Kinases (Fyn, Lyn) | Water-based pharmacophore from MD simulations | Approach effective at modeling conserved core interactions; challenges remained with flexible regions, underscoring the need for dynamic shape considerations. | [12] |

| Multiple Targets (e.g., NEU, AA2AR) | O-LAP shape-focused pharmacophore (clustered docking poses) | Shape-focused models (derived from atomic clusters) massively improved default docking enrichment by explicitly scoring shape complementarity. | [7] |

The explicit incorporation of binding site shape through exclusion volumes is a critical advancement in pharmacophore modeling. Moving beyond a purely chemical feature-based approach to one that enforces steric complementarity allows for a more accurate in silico representation of the physical reality of ligand binding. This directly addresses the fundamental biological rationale that preventing steric clashes is non-negotiable for high-affinity interactions. As methods evolve to include dynamics and more sophisticated shape-matching algorithms, the ability of pharmacophore models to guide the efficient discovery of novel, potent, and selective therapeutic agents will only increase. The consistent integration of exclusion volumes is, therefore, a best practice that bridges the gap between abstract chemical patterns and the precise steric requirements of a target protein's binding pocket.

In the realm of structure-based drug design, pharmacophore modeling serves as a critical methodology for identifying and optimizing novel therapeutic agents. A pharmacophore is formally defined as "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or to block) its biological response" [4]. While much attention is given to the pharmacophoric features—hydrogen bond acceptors (HBAs), hydrogen bond donors (HBDs), hydrophobic areas (H), positively and negatively ionizable groups (PI/NI), and aromatic rings (AR)—the complete pharmacophore model requires an equally critical component: exclusion volumes [4].

Exclusion volumes, also termed "forbidden areas" or "excluded volumes," represent spatial constraints within the binding pocket where ligand atoms cannot encroach without incurring significant energetic penalties [4]. These steric constraints are typically represented as spheres in the 3D pharmacophore model and are derived from the protein's atomic structure. They encapsulate regions occupied by protein atoms that are not part of the binding pocket's accessible space, thereby providing crucial negative design elements that complement the positive design elements of traditional pharmacophoric features [6].

This technical guide examines the complementary roles of exclusion volumes and pharmacophoric features in constructing complete and effective pharmacophore models. We will explore their theoretical foundations, quantitative impact on virtual screening performance, practical implementation methodologies, and emerging applications in modern drug discovery pipelines.

Conceptual Foundation and Theoretical Basis

The Dual Nature of Molecular Recognition

The interaction between a ligand and its biological target is governed by both attractive and repulsive forces. Pharmacophoric features primarily represent the attractive components—specific chemical functionalities that form favorable interactions with the protein target, such as hydrogen bonds, ionic interactions, and hydrophobic contacts [4]. These features guide the identification of molecules capable of establishing productive binding interactions.

Conversely, exclusion volumes represent the repulsive components of molecular recognition. They explicitly model the shape complementarity required between the ligand and the binding pocket by defining regions where ligand atoms would experience steric clashes with protein atoms [6]. Without these constraints, pharmacophore models would identify compounds that possess the necessary functional groups but cannot physically fit within the binding site due to steric hindrance.

Spatial Representation of Binding Site Topology

In structure-based pharmacophore modeling, exclusion volumes are generated based on the 3D structure of the target protein. The process typically involves:

- Mapping the binding site cavity using the atomic coordinates of the protein structure

- Adding exclusion volumes to represent the van der Waals radii of protein atoms within and surrounding the binding pocket [5]

- Including an exclusion volume "coat"—a second shell of exclusion volumes to more comprehensively represent the binding site shape [15]

This spatial representation transforms the abstract concept of molecular shape into a queryable feature within the pharmacophore model, enabling more accurate virtual screening that accounts for both electronic and steric compatibility.

Table 1: Core Components of a Complete Pharmacophore Model

| Component Type | Representation | Role in Molecular Recognition | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmacophoric Features (Positive design) | Geometric entities (points, vectors, planes) | Define essential favorable interactions with target | HBA, HBD, Hydrophobic, Ionic [4] |

| Exclusion Volumes (Negative design) | Spheres representing forbidden regions | Define steric constraints and shape complementarity | Protein atom volumes, Binding site shape [6] |

| Complementary Role | Integrated 3D model | Simultaneously ensures interaction capability and binding compatibility | Combined features and volumes in screening queries [5] |

Quantitative Impact on Virtual Screening Performance

Enhancement of Enrichment Metrics

The inclusion of exclusion volumes in pharmacophore models significantly improves virtual screening performance by reducing false positives—compounds that match the pharmacophoric features but cannot properly bind due to steric clashes. This improvement is quantifiable through several key metrics:

In a study on XIAP protein inhibitors, a structure-based pharmacophore model incorporating exclusion volumes demonstrated exceptional discriminatory power, achieving an area under the ROC curve (AUC) value of 0.98 and an early enrichment factor (EF1%) of 10.0. This indicates a high capability to distinguish true active compounds from decoys [5].

Research on CDK2 and human DHFR systems demonstrated that pharmacophore models with excluded volumes provided "a more selective model to reduce false positives and a better enrichment rate in virtual screening" compared to models without these steric constraints [6].

Specific Case Study: σ1 Receptor Ligands

A comprehensive analysis of sigma-1 receptor (σ1R) pharmacophore models revealed the critical importance of exclusion volumes in predictive accuracy. When comparing multiple pharmacophore approaches, the model (5HK1-Ph.B) that properly accounted for steric restrictions through exclusion volumes achieved a ROC-AUC value above 0.8 and enrichment values above 3 at different fractions of screened samples [16].

Notably, this exclusion volume-enhanced model outperformed direct molecular docking in virtual screening accuracy, suggesting that the explicit representation of steric constraints in pharmacophore models may capture binding determinants that are not fully accounted for by some docking scoring functions [16].

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Improvement with Exclusion Volumes

| Target Protein | Screening Metric | Without Exclusion Volumes | With Exclusion Volumes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| XIAP | AUC (ROC Curve) | Not Reported | 0.98 | [5] |

| XIAP | Early Enrichment Factor (EF1%) | Not Reported | 10.0 | [5] |

| σ1 Receptor | ROC-AUC | Variable (model-dependent) | >0.80 | [16] |

| σ1 Receptor | Enrichment Factor | Variable (model-dependent) | >3.0 | [16] |

| CDK2 & DHFR | False Positive Rate | Higher | Significantly Reduced | [6] |

Methodological Implementation Protocols

Structure-Based Exclusion Volume Generation

The generation of exclusion volumes from protein structures follows a standardized workflow in most molecular design software platforms (e.g., Discovery Studio, LigandScout, MOE):

Protein Structure Preparation

- Obtain high-quality protein structure from PDB or homology modeling

- Add hydrogen atoms and optimize protonation states at physiological pH

- Energy minimization to relieve steric clashes [5] [16]

Binding Site Delineation

- Identify the binding pocket through analysis of co-crystallized ligands or binding site detection algorithms

- Define a region of interest around the binding site (typically 5-10 Å from reference ligand) [8]

Exclusion Volume Assignment

- Automatically generate exclusion volumes based on protein atom van der Waals radii

- Add exclusion volume "coat" for comprehensive shape representation [15]

- Manually refine volumes to remove artifacts and ensure biological relevance

Ligand-Based Approaches with HypoGenRefine

When protein structural information is unavailable, exclusion volumes can be derived indirectly from known active ligands using the HypoGenRefine algorithm in Catalyst (now part of Discovery Studio). This approach:

- Analyzes the steric constraints implied by a set of active compounds

- Automatically adds excluded volume features to ligand-based pharmacophores

- Accounts for steric effects on activity based on conserved molecular shapes [6]

The algorithm identifies regions consistently unoccupied by active ligands and incorporates these as exclusion volumes, effectively translating the collective shape information from multiple active compounds into steric constraints for virtual screening.

Advanced Implementation: FragmentScout Workflow

A recent innovative methodology called FragmentScout demonstrates the sophisticated application of exclusion volumes in fragment-based drug discovery. This workflow:

- Aggregates pharmacophore feature information from multiple experimental fragment poses

- Generates a joint pharmacophore query for each binding site cluster

- Incorporates comprehensive exclusion volumes derived from all fragment structures [15]

This approach is particularly valuable for leveraging high-throughput crystallographic fragment screening data (e.g., from XChem facilities), as it systematically captures the steric constraints observed across multiple fragment-bound structures.

Diagram 1: Fragment-based pharmacophore development workflow.

Integration with Contemporary Drug Discovery Workflows

Synergy with Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Static crystal structures provide limited information about protein flexibility, which can lead to overly restrictive exclusion volumes. Integration with molecular dynamics (MD) simulations addresses this limitation:

The dyphAI protocol employs an ensemble pharmacophore approach that incorporates protein flexibility by:

- Generating multiple receptor conformations through MD simulations

- Creating individual pharmacophore models for representative snapshots

- Combining these models into a consensus pharmacophore with appropriately defined exclusion volumes [17]

This dynamic pharmacophore modeling captures the essential steric constraints while accounting for binding site flexibility, potentially reducing overly restrictive exclusion that might eliminate viable ligands.

Complementarity with Deep Learning Approaches

Recent advances in AI-driven molecular generation demonstrate how exclusion volumes guide the creation of novel bioactive compounds:

The Pharmacophore-Guided deep learning approach for bioactive Molecule Generation (PGMG) uses pharmacophore hypotheses—including spatial constraints—as conditional inputs for generative models [18]. In this framework:

- Pharmacophore features (including exclusion volumes) are represented as graph nodes

- Spatial relationships between features are encoded as edge properties

- The generator creates molecules that satisfy both the positive pharmacophoric features and the steric constraints

This integration demonstrates how exclusion volumes serve as critical boundary conditions in the generative chemical space, ensuring that newly designed molecules possess both binding capability and structural compatibility.

Diagram 2: AI and pharmacophore modeling integration process.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Table 3: Essential Resources for Exclusion Volume-Enhanced Pharmacophore Modeling

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Key Functionality | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Software Platforms | LigandScout [5] [15] | Structure-based pharmacophore modeling with automatic exclusion volume generation | Virtual screening, fragment-based design |

| Discovery Studio [8] [16] | HypoGenRefine for ligand-based exclusion volumes; protein preparation | QSAR modeling, lead optimization | |

| MOE [16] | Pharmacophore elucidation and modeling | Multi-conformer pharmacophore generation | |

| Methodological Protocols | FragmentScout [15] | Joint pharmacophore query generation from fragment screens | Fragment-to-lead optimization |

| dyphAI [17] | Dynamic pharmacophore modeling with MD simulations | Accounting for protein flexibility | |

| PGMG [18] | Deep learning molecule generation guided by pharmacophores | De novo drug design | |

| Data Resources | RCSB Protein Data Bank [5] [19] | Source of experimental protein structures | Structure-based model development |

| ZINC Database [5] [19] | Commercially available compounds for virtual screening | Compound acquisition for testing | |

| ChEMBL [18] | Bioactivity data for model validation | Ligand-based model development |

Exclusion volumes and pharmacophoric features represent complementary elements that together constitute a complete and effective pharmacophore model. While pharmacophoric features define the essential electronic and steric characteristics necessary for productive binding interactions, exclusion volumes provide the critical steric constraints that ensure shape complementarity with the target binding site.

The integration of exclusion volumes significantly enhances virtual screening performance by reducing false positives and improving enrichment factors, as demonstrated across multiple target classes and therapeutic areas. Contemporary methodologies, including dynamic pharmacophore modeling and AI-driven molecular generation, continue to evolve the sophisticated application of exclusion volumes in drug discovery.

As structural information continues to grow through advances in crystallography and cryo-EM, and computational methods become increasingly integrated with machine learning approaches, the precise definition and application of exclusion volumes will remain fundamental to the development of effective pharmacophore models. Their continued refinement and appropriate implementation represent an essential component of rational drug design strategies aimed at efficiently identifying novel therapeutic agents with optimal binding characteristics.

In the realm of computer-aided drug discovery, pharmacophore modeling stands as a pivotal technique for identifying potential drug candidates by representing the essential steric and electronic features necessary for molecular recognition by a biological target [4]. The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) defines a pharmacophore as "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supra-molecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or to block) its biological response" [4]. These features typically include hydrogen bond acceptors (HBAs), hydrogen bond donors (HBDs), hydrophobic areas (H), positively and negatively ionizable groups (PI/NI), aromatic groups (AR), and metal coordinating areas [4].

However, a complete pharmacophore model requires more than just the definition of favorable interaction points; it must also account for spatial restrictions. Exclusion volumes (XVOL) serve as critical components in structure-based pharmacophore modeling by representing forbidden areas that reflect the size and shape of the binding pocket [4]. These volumes explicitly define regions of space where ligand atoms cannot encroach without incurring steric clashes with the target protein, thereby significantly enhancing the selectivity of virtual screening by filtering out molecules that, while possessing the necessary functional groups, are sterically incompatible with the binding site.

Table 1: Core Feature Types in Pharmacophore Modeling

| Feature Type | Symbol | Description | Role in Molecular Recognition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Bond Acceptor | HBA | Atom that can accept a hydrogen bond | Forms specific interactions with donor groups on protein |

| Hydrogen Bond Donor | HBD | Atom that can donate a hydrogen bond | Forms specific interactions with acceptor groups on protein |

| Hydrophobic Area | H | Non-polar atom or region | Engages in van der Waals and desolvation interactions |

| Aromatic Ring | AR | Planar conjugated π-system | Participates in cation-π, π-π, and hydrophobic interactions |

| Positively Ionizable | PI | Atom that can carry a positive charge | Engages in electrostatic interactions with acidic residues |

| Negatively Ionizable | NI | Atom that can carry a negative charge | Engages in electrostatic interactions with basic residues |

| Exclusion Volume | XVOL | Forbidden spatial region | Prevents steric clashes with protein atoms |

Theoretical Foundation: The Structural Basis of Exclusion Volumes

The Geometric and Energetic Rationale

Exclusion volumes are fundamentally rooted in the Pauli exclusion principle, which dictates that two atoms cannot occupy the same space simultaneously. In molecular interactions, this manifests as a steep repulsive energy when electron clouds of the ligand and receptor begin to overlap [20]. In structure-based pharmacophore modeling, these volumes are derived directly from the three-dimensional structure of the target protein, typically obtained from X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, or homology modeling [4].

The binding site of a protein is not merely a cavity waiting to be filled but a complex topography with specific steric constraints. Exclusion volumes are generated to represent the van der Waals surfaces of protein atoms that line this binding site, creating a negative image of the allowable space [20]. When a pharmacophore model incorporates these exclusion volumes, it becomes a much more accurate representation of the true binding environment, moving beyond simply what interactions are required to include where a ligand physically cannot be.

Contrasting Traditional and Advanced Modeling Approaches

Traditional structure-based pharmacophore methods often use a single, static protein structure to define exclusion volumes, which can limit their accuracy due to inherent protein flexibility [20]. More advanced approaches, such as the Site Identification by Ligand Competitive Saturation (SILCS) method, address this limitation by using molecular dynamics (MD) simulations in an aqueous solution containing various probe molecules [20]. This protocol naturally accounts for protein flexibility and desolvation effects, producing more realistic exclusion maps that represent the time-averaged spatial occupancy of the protein atoms [20]. The SILCS-Pharm protocol converts Grid Free Energy (GFE) FragMaps into pharmacophore features and uses the spatial distribution of the protein to define exclusion volumes that more accurately reflect the dynamic nature of the binding pocket [20].

Practical Implementation: Methodologies for Defining and Using Exclusion Volumes

Structure-Based Workflow for Exclusion Volume Implementation

The process of creating a pharmacophore model with exclusion volumes typically follows a structured workflow when starting from a protein structure. The key steps are visualized in the following diagram and explained in detail below:

Diagram 1: Workflow for Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling with Exclusion Volumes. This diagram illustrates the sequential process of creating a pharmacophore model that incorporates exclusion volumes, starting from a protein structure and culminating in virtual screening.

Protein Structure Preparation: The process begins with obtaining a high-quality 3D structure of the target protein, often from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) [4] [21]. The structure is then prepared by adding hydrogen atoms, correcting protonation states, and addressing any missing residues or atoms [4]. This step is crucial as the quality of the input structure directly influences the accuracy of the resulting pharmacophore model, including its exclusion volumes.

Binding Site Identification: The specific region where ligands bind must be identified. This can be done manually if the structure contains a co-crystallized ligand, or using computational tools like GRID or LUDI that analyze the protein surface to locate potential binding pockets based on energetic and geometric properties [4].

Pharmacophore Feature Generation: Key interaction points (hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic areas, etc.) are identified within the binding site. These features represent the positive interactions a ligand must make with the protein [4].

Exclusion Volume Placement: This critical step involves mapping the van der Waals surfaces of protein atoms that form the binding pocket. These surfaces are converted into spatial constraints, typically represented as spheres or grids, that define regions where ligand atoms are not permitted [4] [20]. In tools like RDKit, this can be implemented using functions like

AddExcludedVolumesto define these forbidden regions [22].Model Validation: Before use in virtual screening, the pharmacophore model (features and exclusion volumes) should be validated using known active and inactive compounds to ensure it can successfully discriminate between binders and non-binders [23].

Technical Implementation in Virtual Screening Workflows

During virtual screening, a pharmacophore model with exclusion volumes acts as a multi-tiered filter. Each compound in the virtual library is evaluated against the model in a process that typically involves:

- Conformational Sampling: Multiple low-energy 3D conformations are generated for each compound in the screening library [21].

- Feature Matching: Each conformation is tested to see if it can spatially align with all the essential pharmacophore features (HBA, HBD, hydrophobic, etc.).

- Exclusion Volume Check: Conformations that successfully match all features are then checked for steric clashes with the defined exclusion volumes. Any conformation where an atom intersects with an exclusion volume sphere is rejected.

- Hit Selection: Compounds that possess at least one conformation satisfying both the feature matching and exclusion volume constraints are selected as virtual hits for further analysis.

Table 2: Impact of Exclusion Volumes on Virtual Screening Performance

| Validation Metric | Purpose | Impact of Proper Exclusion Volumes |

|---|---|---|

| Enrichment Factor (EF) | Measures the concentration of active compounds in the hit list | Significantly improves EF by removing false positives that match features but have steric clashes [23]. |

| Area Under the Curve (AUC) | Overall measure of model discrimination power | Increases AUC value by improving the model's ability to reject non-binders [23]. |

| False Positive Rate | Proportion of inactive compounds incorrectly identified as hits | Dramatically reduces false positives by filtering sterically incompatible molecules [20]. |

| Scaffold Diversity | Variety of chemical structures in the hit list | Can improve diversity by preventing bias toward overly bulky compounds that might fit without exclusion volumes. |

Case Studies and Experimental Evidence

Successful Applications in Drug Discovery

The strategic implementation of exclusion volumes has proven critical in numerous successful virtual screening campaigns. In one notable study targeting the Brd4 protein for neuroblastoma treatment, researchers developed a structure-based pharmacophore model that incorporated fifteen exclusion volumes alongside hydrophobic contacts and hydrogen bonding features [23]. This model demonstrated exceptional performance in validation, with an Area Under the Curve (AUC) of 1.0 and strong enrichment factors, leading to the identification of four promising natural compounds with potential inhibitory activity against Brd4 [23].

In another study targeting SARS-CoV-2 papain-like protease (PLpro), researchers developed a structure-based pharmacophore model with 9 features that was used to screen a marine natural product database [24]. The resulting 66 initial hits were further filtered by molecular weight and subjected to comparative molecular docking, ultimately identifying aspergillipeptide F as a promising inhibitor that engages all five binding sites of PLpro [24]. Molecular dynamics simulations confirmed the stability of the complex, demonstrating how pharmacophore screening serves as an effective initial filter in a multi-stage virtual screening workflow [24].

Experimental Protocols for Exclusion Volume Implementation

Protocol: Generating a Structure-Based Pharmacophore with Exclusion Volumes Using SILCS-Pharm

The SILCS-Pharm protocol provides a sophisticated approach to defining exclusion volumes that account for protein flexibility and desolvation effects [20].

System Setup and SILCS Simulation:

- Prepare the protein structure using standard molecular dynamics protocols.

- Set up the simulation system with the target protein solvated in an aqueous solution containing diverse probe molecules: benzene (aromatic), propane (aliphatic), methanol (neutral donor/acceptor), formamide (neutral donor/acceptor), acetaldehyde (acceptor), methylammonium (positive donor), and acetate (negative acceptor) [20].

- Perform extensive Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations to allow probe molecules to competitively sample the protein surface.

FragMap and Exclusion Map Generation:

- Process the MD trajectories to generate FragMaps by binning the residences of probe molecule atoms into a 3D grid surrounding the protein.

- Convert FragMaps into Grid Free Energy (GFE) representations using Boltzmann transformation [20].

- Define exclusion volumes based on the van der Waals surface of the protein, using the spatial distribution of protein atoms throughout the simulation to create a time-averaged exclusion map.

Pharmacophore Feature Identification:

- Identify potential pharmacophore features from the GFE FragMaps by selecting voxels with favorable interaction free energies.

- Cluster these voxels to define specific interaction features (hydrogen bond donors, acceptors, hydrophobic, etc.).

- Prioritize features using Feature Grid Free Energy (FGFE) scores, which represent the sum of voxel GFEs comprising a FragMap feature [20].

Pharmacophore Hypothesis Generation:

- Combine the highest-ranked pharmacophore features with the exclusion volumes to create the final pharmacophore hypothesis.

- Validate the model using known active and inactive compounds before proceeding to virtual screening.

Table 3: Key Software and Tools for Pharmacophore Modeling with Exclusion Volumes

| Tool/Software | Function | Exclusion Volume Capabilities |

|---|---|---|

| LigandScout | Advanced pharmacophore modeling | Generates exclusion volumes automatically from protein structure; allows manual refinement [23]. |

| SILCS-Pharm | Flexible pharmacophore modeling | Uses MD-derived exclusion maps that account for protein flexibility and desolvation [20]. |

| RDKit | Open-source cheminformatics | Provides AddExcludedVolumes functionality for defining exclusion spheres in pharmacophore models [22]. |

| GRID | Molecular interaction fields | Identifies favorable and unfavorable interaction regions that inform exclusion volume placement [4]. |

| Schrödinger Suite | Comprehensive drug discovery platform | Includes exclusion volume generation in its structure-based pharmacophore modeling workflows [21]. |

| OpenEye Toolkits | Molecular design and simulation | Offers conformer generation and pharmacophore tools that support spatial constraints [21]. |

Exclusion volumes represent a critical component in modern pharmacophore modeling, transforming simple feature-based queries into sophisticated, selective tools capable of accurately discriminating between true binders and non-binders. By explicitly representing the steric constraints of the binding pocket, exclusion volumes significantly reduce false positive rates in virtual screening and increase enrichment factors, thereby accelerating the drug discovery process. As computational methods continue to evolve, particularly with approaches that incorporate protein flexibility and solvation effects like SILCS-Pharm, the precision and predictive power of exclusion volumes will further increase. Their proper implementation remains an essential best practice for researchers aiming to leverage pharmacophore modeling for efficient and effective virtual screening in drug development.

Building Better Models: Structure-Based and Ligand-Based Generation of Exclusion Volumes

In the realm of structure-based drug design, a pharmacophore is defined as an abstract representation of the steric and electronic features essential for a molecule to interact with a specific biological target and trigger its biological response [4] [9]. While features like hydrogen bond donors and hydrophobic areas define favorable interaction points, exclusion volumes (also known as excluded volumes) constitute a critical steric component. These volumes represent regions in three-dimensional space that are occupied by the receptor and where the presence of a ligand atom would cause unfavorable steric clashes, thereby disrupting binding [4] [9].

The derivation of accurate exclusion volumes is, therefore, paramount for creating pharmacophore models that can reliably discriminate between active and inactive compounds during virtual screening. This guide details the methodologies for deriving these essential volumes from the two predominant experimental techniques in structural biology: X-ray crystallography and Cryo-Electron Microscopy (Cryo-EM).

Methodological Foundations: Deriving Exclusion Volumes from Protein Structures

Source Data Considerations and Preprocessing

The quality of the input protein structure directly dictates the reliability of the derived exclusion volumes. The first step in the workflow involves a critical assessment and preparation of the structural data.

Structure Quality Assessment:

- Resolution and Map Quality: For both X-ray and Cryo-EM structures, the global resolution is a primary indicator of quality. However, local resolution variations, particularly in Cryo-EM maps, must be examined. Regions with poor resolution may have ambiguous atom placements, leading to unreliable exclusion volumes.

- B-factors/Temperature Factors: These values indicate the vibrational motion or positional disorder of atoms. Atoms with exceptionally high B-factors are less rigidly positioned, and their associated exclusion volumes may need to be treated with caution or assigned a softer boundary.

- Real Space Correlation Coefficient (RSCC): This metric, available for both X-ray and Cryo-EM structures, measures how well the atomic model fits the experimental electron density. Residues with low RSCC values should be inspected carefully.

Structure Preparation:

- Protonation State Assignment: Hydrogen atoms are often not visible in experimental electron density maps. Using molecular modeling software, it is crucial to add hydrogen atoms and assign the correct protonation states to residues like Histidine, Aspartic Acid, and Glutamic Acid based on the local chemical environment and pH.

- Loop Modeling and Missing Residues: If the structure contains loops or regions with missing residues, these gaps should be filled using homology modeling or de novo loop modeling techniques to ensure a complete representation of the binding site sterics.

- Removal of Artifacts: Crystallization additives, buffer molecules, and water networks that are not part of the functional protein must be removed, unless a specific water molecule is deemed structurally critical and forms part of the binding site architecture.

Protocol 1: Deriving Exclusion Volumes from X-ray Crystallography Structures

X-ray crystallography provides a high-resolution, static model of the protein, which serves as an excellent starting point for defining precise exclusion volumes. The following protocol outlines a standard workflow for structure-based pharmacophore generation, including exclusion volume placement.

Table 1: Key Software Tools for Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

| Software Tool | Primary Function | Application in Exclusion Volume Derivation |

|---|---|---|

| GRID [4] | Generates molecular interaction fields | Identifies energetically unfavorable regions for probe atoms, directly informing exclusion volume placement. |

| LUDI [4] | Predicts interaction sites | Uses knowledge-based rules to define areas sterically forbidden for ligand atoms. |

| Phase [25] | Comprehensive pharmacophore modeling | Automatically generates exclusion volumes based on the van der Waals surface of the protein's binding site residues. |

Experimental Protocol:

- Retrieve and Prepare the Protein Structure: Download the protein-ligand complex structure from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). Using a suite like Maestro's Protein Preparation Wizard, add hydrogen atoms, assign bond orders, and optimize the hydrogen-bonding network.

- Define the Binding Site: The binding site can be defined as the residues within a specified radius (e.g., 5-10 Å) of the co-crystallized ligand. Alternatively, tools like GRID or SiteMap can be used to identify the binding pocket de novo [4].

- Generate the Pharmacophore Model: Initiate a structure-based pharmacophore generation module within software such as Phase or MOE. The algorithm will identify key protein-ligand interaction features (hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic patches, charged groups).

- Place Exclusion Volumes: The software automatically places exclusion volumes, typically represented as spheres, at grid points that fall within the protein's van der Waals radius. These spheres collectively define the space the ligand cannot occupy.

- Manual Refinement: Critically examine the automated model. Remove exclusion volumes in flexible side-chain regions if conformational flexibility is expected. The final model consists of the essential chemical features and the refined set of exclusion volumes, creating a spatial query for virtual screening [4] [26].

Diagram 1: Workflow for deriving exclusion volumes from X-ray crystal structures.

Protocol 2: Deriving Exclusion Volumes from Cryo-EM Structures

Cryo-EM is revolutionizing the study of large macromolecular complexes and membrane proteins that are difficult to crystallize [27] [28]. Deriving exclusion volumes from Cryo-EM structures involves working with an atomic model fitted into a 3D electron density map (often an EM map).

Experimental Protocol:

- Assess the Cryo-EM Data: Obtain the atomic model and the associated EM map from the Electron Microscopy Data Bank (EMDB). Critically evaluate the local resolution of the map around the binding site of interest using tools like UCSF Chimera.

- Model Preparation and Real-Space Refinement: Similar to X-ray structures, prepare the atomic model by adding hydrogens and assigning correct protonation states. It is often beneficial to perform a final round of real-space refinement of the model into the EM map to ensure optimal fit, particularly for flexible loops near the binding site.

- Map Segmentation and Binding Site Analysis: Isolate the electron density corresponding to the binding pocket. The contour level of the map (typically at 1-2 σ) defines the boundary of the protein's envelope.

- Generate and Validate Exclusion Volumes: Use the atomic model to generate exclusion volumes as in the X-ray protocol. However, the electron density map provides a crucial cross-check. Exclusion volumes should lie within the region defined by the contoured EM map. Any volume placed in a region with no supporting density should be considered suspect and may represent a modeling error or a flexible region not resolved in the map.

- Account for Conformational Heterogeneity: A key advantage of Cryo-EM is its ability to capture multiple conformational states from a single sample [28]. If 3D classification has revealed distinct states, derive a separate pharmacophore with unique exclusion volumes for each relevant state to enable state-specific inhibitor design.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis for Exclusion Volume Derivation

| Parameter | X-ray Crystallography | Cryo-Electron Microscopy |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Resolution Range | Often atomic (1.5 - 2.5 Å) | Near-atomic to atomic (1.8 - 4.0 Å) [29] |

| Primary Source for Volumes | Atomic model & B-factors | Atomic model, validated against EM map |

| Handling of Flexibility | Usually a single, static conformation | Can capture multiple conformations [28] |

| Key Challenge | Crystal packing may distort binding site | Lower resolution can blur precise steric boundaries |

| Best Suited For | Well-ordered, crystallizable proteins | Large complexes, membrane proteins, flexible systems |

Diagram 2: Workflow for deriving exclusion volumes from Cryo-EM structures.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful derivation of exclusion volumes relies on a combination of software tools, data resources, and structural biology techniques.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item Name | Function / Explanation | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Repository for 3D structural data of proteins and nucleic acids solved by X-ray crystallography, Cryo-EM, and NMR [4]. | Primary source for downloading initial protein-ligand complex structures for analysis. |

| Electron Microscopy Data Bank (EMDB) | Public repository for electron microscopy density maps, tomograms, and associated atomic models [29]. | Source for Cryo-EM maps used to validate and inform exclusion volume placement. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation | Computational method for simulating physical movements of atoms and molecules over time, providing insights into protein flexibility and dynamics [9]. | Used to generate an ensemble of protein conformations to create "soft" or dynamic exclusion volumes that account for side-chain motion. |

| Structure Preparation Software | Tools for adding missing atoms, assigning protonation states, and optimizing hydrogen-bonding networks (e.g., Maestro, MOE, UCSF Chimera). | Critical pre-processing step to ensure the atomic model is chemically accurate before pharmacophore generation. |

| Pharmacophore Modeling Suite | Integrated software for generating, visualizing, and validating pharmacophore models (e.g., Phase, MOE, LigandScout). | Core environment for the automated and manual placement of both chemical features and exclusion volumes. |

The accurate derivation of exclusion volumes from experimental protein structures is a cornerstone of effective structure-based pharmacophore modeling. While X-ray crystallography provides high-precision static models ideal for defining strict steric constraints, Cryo-EM offers a powerful and increasingly high-resolution window into the world of larger, more flexible complexes, allowing for the modeling of exclusion volumes in previously intractable targets. By adhering to the rigorous preprocessing, generation, and validation protocols outlined in this guide, researchers can create highly discriminative pharmacophore models. These models, which faithfully represent both the attractive interaction features and the repulsive steric constraints of the binding site, are indispensable tools for accelerating the discovery of novel and potent therapeutic agents.

The HypoGenRefine algorithm represents a significant advancement in ligand-based pharmacophore modeling by integrating excluded volumes to account for steric constraints that are critical for biological activity. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of the HypoGenRefine methodology, detailing its theoretical foundation, implementation protocols, and application in virtual screening. By incorporating excluded volume features derived from active ligands alone, HypoGenRefine addresses a fundamental limitation of traditional pharmacophore models that focus exclusively on favorable interaction features. The algorithm's ability to automatically generate and refine these steric constraints has demonstrated improved model selectivity and enhanced enrichment rates in virtual screening, making it a valuable tool for drug discovery researchers working in the absence of detailed structural target information.

A pharmacophore is defined as an abstract representation of the spatial arrangement of molecular features essential for a ligand's biological activity [9]. These features typically include hydrogen bond donors and acceptors, charged groups, and hydrophobic regions. Traditional pharmacophore models identify favorable ligand-receptor interactions but often neglect the critical aspect of steric constraints. Exclusion volumes address this limitation by representing regions in space that are sterically forbidden for ligand atoms, thereby mimicking the actual three-dimensional shape of the binding pocket [6]. The integration of these volumes transforms pharmacophore models from purely permissive interaction patterns to constrained models that more accurately reflect the binding site environment.

The HypoGenRefine algorithm within Catalyst (now part of BioVia's Discovery Studio) implements an automated approach to incorporate excluded volumes based solely on ligand information [6] [30]. This capability is particularly valuable in ligand-based drug design (LBDD) scenarios, where the three-dimensional structure of the target protein is unavailable [31] [32]. By analyzing the structural features of active and inactive compounds, HypoGenRefine deduces not only the essential interactions but also the steric restrictions that differentiate active from inactive molecules. This holistic approach results in pharmacophore models with significantly improved predictive power and practical utility in virtual screening campaigns.

Theoretical Foundation of HypoGenRefine

Algorithmic Principles