Ensemble Pharmacophore Modeling: A Flexible Approach for Targeting Dynamic Binding Sites in Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of ensemble pharmacophore modeling, a powerful computational strategy that addresses the challenge of protein flexibility in structure-based drug design.

Ensemble Pharmacophore Modeling: A Flexible Approach for Targeting Dynamic Binding Sites in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of ensemble pharmacophore modeling, a powerful computational strategy that addresses the challenge of protein flexibility in structure-based drug design. By moving beyond single static structures, ensemble methods leverage multiple protein conformations to create more accurate and effective pharmacophore models. We explore the foundational concepts, detailing the necessity of this approach for flexible binding sites and its basis in the conformational selection theory. The article then delves into practical methodologies, from MD simulations and druggability simulations to tools like Pharmmaker, and illustrates their successful application against targets like tubulin and GSK-3β. A dedicated troubleshooting section addresses common pitfalls in virtual screening and ADMET prediction, while validation protocols and performance metrics are discussed to ensure model reliability. This resource is tailored for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to implement these advanced in silico techniques to identify novel hits for challenging biological targets.

Beyond the Static Structure: The Why and How of Ensemble Pharmacophore Modeling

The Challenge of Protein Flexibility in Structure-Based Drug Design

Protein flexibility is a fundamental characteristic of biological macromolecules that presents both a challenge and an opportunity in structure-based drug design (SBDD). The intrinsic dynamic nature of proteins enables them to adopt multiple conformational states, creating a complex conformational ensemble that influences biomolecular recognition and ligand binding [1]. Traditional SBDD approaches that treat protein targets as rigid entities fail to capture the dynamic binding processes central to drug action, creating a significant gap between computational predictions and experimental results [1] [2].

The evolution from rigid lock-and-key models to more sophisticated understanding of binding mechanisms has highlighted the importance of conformational selection and induced fit in molecular recognition [1]. In conformational selection, the ligand selectively stabilizes specific pre-existing receptor conformations from the ensemble, causing a population shift toward these states [1]. In contrast, induced fit involves conformational changes that occur after initial ligand binding [1]. Most real-world systems involve a combination of both mechanisms, with recent studies showing that "conformational selection is usually followed by a conformational adjustment" [1].

This application note examines the challenge of protein flexibility within the context of ensemble pharmacophore modeling, providing detailed protocols and quantitative frameworks to address dynamic binding sites in rational drug discovery campaigns.

Biomolecular Recognition Mechanisms and Their Implications for Drug Design

Fundamental Binding Mechanisms

Understanding protein-ligand binding requires appreciation of three primary mechanisms that have evolved in our conceptual framework:

- Lock-and-Key Model: The earliest model depicting perfect steric complementarity between rigid ligand and protein.

- Induced Fit: Introduced by Koshland, this mechanism involves formation of an initial loose ligand-receptor complex that induces conformational changes leading to tighter binding [1].

- Conformational Selection/Population Shift: Proposed by Nussinov and colleagues, this model posits that all conformations exist in the unbound state, with ligands selectively stabilizing specific conformational states from this ensemble [1].

Allostery and Signal Transduction

Allosteric effects represent a crucial manifestation of protein flexibility with profound implications for drug discovery. Allostery describes interactions between a regulatory (allosteric) site and another protein site (often the active site) that produce functional changes [1]. The Monod-Wyman-Changeux (MWC) model explains allosteric effects through equilibrium shifts between pre-existing conformational states, while the Koshland-Némethy-Filmer (KNF) model emphasizes induced fit-like conformational transitions [1]. A third model, entropic allostery, suggests purely dynamical effects without major conformational changes [1].

G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) exemplify the pharmacological importance of allosteric transitions, where different ligands stabilize distinct conformations that activate specific signaling pathways [1]. The approved allosteric drug maraviroc, which modulates chemokine CCR5, demonstrates the therapeutic potential of targeting allosteric sites [1].

Table 1: Biomolecular Recognition Mechanisms and Their Characteristics

| Mechanism | Fundamental Principle | Key Contributors | Implications for Drug Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lock-and-Key | Rigid steric complementarity | Emil Fischer | Limited applicability to flexible targets |

| Induced Fit | Conformational change after binding | Daniel Koshland | Difficult to predict binding poses |

| Conformational Selection | Ligand selects pre-existing conformations | Ruth Nussinov, others | Requires ensemble-based approaches |

| Allostery | Remote regulation via effector binding | Jacques Monod, others | Enables targeting of non-active sites |

Computational Approaches to Address Protein Flexibility

Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations provide an atomistic, dynamic view of ligand-receptor complexes by numerically solving Newton's equations of motion for all atoms in the system [3]. These simulations capture conformational changes, binding flexibility, and transient effects that influence drug behavior [3]. Advanced implementations include steered MD and umbrella sampling to study binding/unbinding kinetics and thermodynamics [3].

In practice, MD simulations generate structural ensembles for ensemble docking, where multiple protein conformations are used in docking processes to account for structural variability [4] [5]. A typical workflow involves running simulations, clustering trajectory frames based on root-mean-square deviation (RMSD), and selecting representative structures from the largest clusters [5].

Enhanced Sampling and Normal Mode Analysis

Enhanced sampling techniques such as accelerated MD and replica exchange MD improve conformational sampling efficiency by overcoming energy barriers that limit exploration in conventional MD [1] [4]. These methods are particularly valuable for studying rare events or complex conformational transitions.

Elastic network models (ENM), including the Anisotropic Network Model (ANM), provide computationally efficient frameworks for understanding protein flexibility by capturing low-frequency, large-scale motions [4]. ANM can generate plausible conformers for ensemble docking by deforming protein structures along their slowest normal modes related to functional dynamics [4]. One recent study generated 36 conformers of triose phosphate isomerase (TIM) by assessing six deformation parameters in both directions of the three slowest harmonic motions [4].

Machine Learning and Generative Models

Recent advances in machine learning (ML) have introduced powerful approaches for handling protein flexibility in drug design. Diffusion models such as PharmacoForge generate 3D pharmacophores conditioned on protein pockets using denoising diffusion probabilistic models (DDPMs) [6] [7]. These models are E(3)-equivariant, meaning they maintain molecular identity under Euclidean transformations (rotation, reflection, translation) [6] [7].

FlexSBDD represents another ML advancement that explicitly models flexible protein-ligand complex structures for ligand generation using flow matching frameworks and E(3)-equivariant networks with scalar-vector dual representations [2]. These approaches address the critical limitation of treating proteins as rigid entities, leading to fewer steric clashes and more favorable interactions in generated molecules [2].

Ensemble Pharmacophore Modeling: Protocols and Applications

Dynamic Pharmacophore Modeling with dyphAI

The dyphAI protocol integrates machine learning, ligand-based pharmacophore models, and complex-based pharmacophore models into a pharmacophore model ensemble that captures key protein-ligand interactions [8]. This approach was successfully applied to identify novel acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibitors, discovering 18 novel molecules from the ZINC database with binding energies ranging from -62 to -115 kJ/mol [8].

Experimental validation confirmed that two identified molecules (P-1894047 and P-2652815) exhibited IC₅₀ values lower than or equal to the control (galantamine), demonstrating potent inhibitory activity [8]. This success highlights the value of integrating computational predictions of dynamic pharmacophores with experimental validation.

PharmacoForge: Diffusion-Based Pharmacophore Generation

PharmacoForge is a diffusion model that generates 3D pharmacophores conditioned on protein binding pockets [6] [7]. The model produces pharmacophore queries that identify valid, commercially available molecules through rapid pharmacophore search, which operates in sub-linear time - orders of magnitude faster than traditional virtual screening methods like molecular docking [6].

In evaluation benchmarks, PharmacoForge surpassed other automated pharmacophore generation methods (Apo2ph4, PharmRL) in the LIT-PCBA benchmark and performed similarly to de novo generated ligands in DUD-E target docking while producing lower strain energies [6] [7].

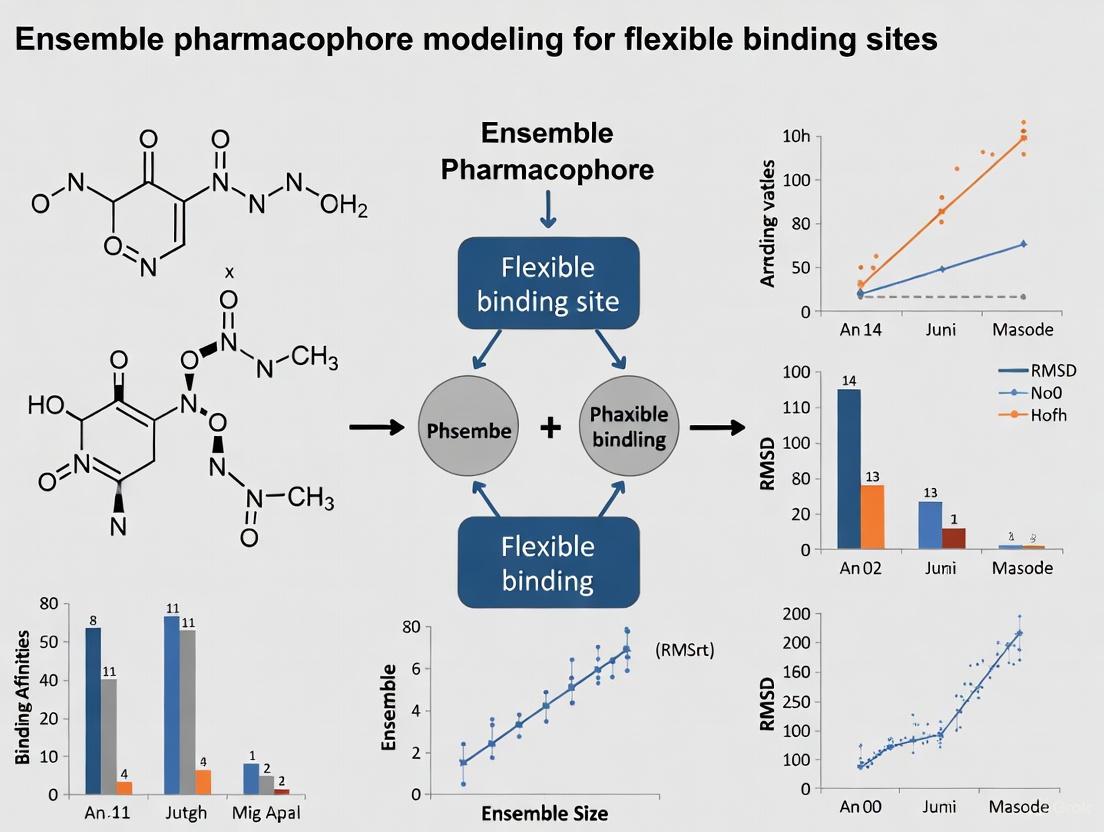

Diagram 1: Ensemble Pharmacophore Modeling Workflow. This diagram illustrates the integrated computational-experimental pipeline for dynamic pharmacophore modeling, combining molecular dynamics, machine learning, and experimental validation.

Mixed-Resolution Conformer Generation Protocol

A computationally efficient method for generating plausible protein conformers combines mixed-resolution modeling with anisotropic network models (ANM) [4]. This approach models binding sites at atomistic resolution while coarse-graining the remaining structure, significantly reducing computational costs while maintaining accuracy in binding site representation [4].

The protocol involves:

- Applying ANM to obtain the slowest normal modes related to functional dynamics

- Generating conformers by deforming high-resolution binding site regions along these normal modes

- Identifying optimal deformation extents through energy minimization and docking calculations

- Performing molecular dynamics simulations with appropriate harmonic restraints (0, 25, 35, and 50 kcal/mol·Å²) to prevent disintegration of truncated structures [4]

This method achieved total simulation times of 15.2 μs for triose phosphate isomerase, with binding free energy calculations indicating that 100 ns-long simulations were sufficient to estimate binding affinities accurately [4].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Computational Methods Addressing Protein Flexibility

| Method | Computational Cost | Key Advantages | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Dynamics | High (μs-scale simulations) | Atomistic detail, physical accuracy | 100 ns sufficient for TIM binding affinity [4] |

| Enhanced Sampling (aMD, REMD) | High | Better exploration of conformational space | Improved conformational sampling for docking [4] |

| Elastic Network Models (ANM) | Low | Efficient for large-scale motions | 36 conformers generated for TIM [4] |

| PharmacoForge | Medium | Fast screening, valid molecules | Superior to Apo2ph4, PharmRL in LIT-PCBA [6] |

| dyphAI | Medium | Integrates multiple data sources | 18 novel AChE inhibitors identified [8] |

| Mixed-Resolution ANM | Medium | Balanced cost/accuracy for large systems | 15.2 μs total simulation for TIM [4] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Ensemble Docking with MD-Derived Conformers

This protocol generates protein conformational ensembles from molecular dynamics simulations for ensemble-based docking [5].

Materials and Software Requirements:

- Molecular dynamics software (e.g., GROMACS, AMBER, Desmond)

- Avogadro software for structural analysis

- Clustering and analysis tools (built-in MD packages)

- Chimera software for visualization and structure preparation

- Docking software (e.g., AutoDock, Schrödinger Glide)

Procedure:

System Preparation:

- Obtain the 3D structure of the target protein (from PDB or homology modeling)

- Prepare the protein structure using standard preparation protocols (add hydrogens, assign partial charges, optimize side chains)

Molecular Dynamics Simulation:

- Solvate the protein in an appropriate water model (TIP3P, SPC)

- Add counterions to neutralize system charge

- Energy minimize the system using steepest descent or conjugate gradient algorithms

- Equilibrate with position restraints on protein heavy atoms (NPT and NVT ensembles)

- Run production MD simulation for sufficient time to capture relevant motions (typically 50-500 ns)

Trajectory Clustering:

- Extract frames from the MD trajectory at regular intervals (e.g., every 100 ps)

- Calculate root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) for all frames relative to a reference

- Perform cluster analysis using the RMSD matrix

- Open the cluster-size.xvg file to assess cluster distribution

- Adjust RMSD cutoff value if needed (increase cutoff if too few clusters, decrease if too many)

- Select representative structures from the largest clusters for docking

Structure Preparation for Docking:

- Open Chimera software and load cluster representatives

- Isolate individual chains if needed (Select → Chain → No ID, then invert selection and delete)

- Save each cluster representative as a separate PDB file

Ensemble Docking:

- Launch docking software (AutoDock Tool described here)

- For each cluster structure:

- Load protein structure (cluster1.pdb)

- Add Kollman charges (Edit → Charges → Add Kollman Charges)

- Save as PDBQT format (Grid → Macromolecules → Choose → Save)

- Prepare ligand (Ligand → Input → Choose ligand → Detect Root → Save as PDBQT)

- Set up grid box (Grid → Grid Box: 120 points in XYZ, 0.375 Å spacing)

- Save grid parameter file (Grid → Output → Save GPF)

- Run AutoGrid (Run → Run AutoGrid)

- Configure docking parameters (Docking → Macromolecule → Set; Docking → Ligand → Choose; Docking → Genetic Algorithm: 100 runs)

- Save docking parameter file (Docking → Output → Save DPF)

- Run AutoDock (Run → Run AutoDock)

- Repeat for all cluster representatives

Analysis:

- Compare binding poses and energies across different conformers

- Identify consistent interaction patterns and conformation-specific variations

- Select top candidates based on binding energy and interaction quality

Troubleshooting Tips:

- If simulations show instability, check system neutralization and minimization protocols

- If clustering produces too few/too many clusters, adjust RMSD cutoff iteratively

- If docking results show high variability, increase the number of cluster representatives

- Validate protocol using known ligands with experimental binding data

Protocol 2: Automated Pharmacophore Generation with PharmacoForge

This protocol utilizes the PharmacoForge diffusion model to generate pharmacophores for virtual screening [6] [7].

Materials and Software Requirements:

- PharmacoForge implementation (available from original authors)

- Protein structure in PDB format

- Pharmacophore screening software (Pharmit, Pharmer)

- Compound databases (ZINC, ChEMBL, in-house libraries)

Procedure:

Protein Preparation:

- Identify and prepare the binding pocket of interest

- Ensure proper protonation states of key residues

- Remove crystallographic waters unless functionally important

Pharmacophore Generation:

- Input the prepared protein structure into PharmacoForge

- Configure generation parameters (number of pharmacophores, feature types)

- Run the diffusion model to generate multiple pharmacophore hypotheses

- Select top pharmacophores based on model confidence scores

Pharmacophore Refinement:

- Analyze generated pharmacophores for chemical合理性

- Adjust feature tolerances based on binding site flexibility

- Merge or filter redundant features

Virtual Screening:

- Use pharmacophore queries to screen compound databases

- Apply sub-structure filters to focus on desired chemotypes

- Perform shape screening if applicable

Hit Analysis:

- Examine matched compounds for drug-like properties

- Cluster results by structural similarity

- Select diverse representatives for further evaluation

Experimental Validation:

- Acquire or synthesize top-ranked compounds

- Test binding affinity and functional activity

- Use results to refine pharmacophore models iteratively

Validation Metrics:

- Enrichment factors in retrospective screening

- docking scores of top hits

- Experimental IC₅₀ values for confirmed actives

- Comparison with known active compounds

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Ensemble Pharmacophore Modeling

| Tool/Software | Type | Primary Function | Application in Ensemble Modeling |

|---|---|---|---|

| GROMACS/AMBER | MD Software | Molecular dynamics simulations | Generate conformational ensembles [5] |

| AutoDock | Docking Software | Molecular docking | Ensemble docking across multiple conformers [5] |

| PharmacoForge | Diffusion Model | 3D Pharmacophore generation | Create pharmacophores conditioned on protein pockets [6] [7] |

| Pharmit/Pharmer | Pharmacophore Software | Pharmacophore screening | Rapid virtual screening with pharmacophore queries [6] |

| dyphAI | AI Workflow | Ensemble pharmacophore modeling | Integrate multiple pharmacophore models [8] |

| ANM Tools | Normal Mode Analysis | Low-frequency motion prediction | Generate large-scale conformational changes [4] |

| Chimera | Visualization | Structural analysis | Visualization and preparation of structural ensembles [5] |

Addressing protein flexibility through ensemble pharmacophore modeling represents a paradigm shift in structure-based drug design. By moving beyond single static structures to dynamic conformational ensembles, researchers can better capture the complexity of biomolecular recognition and improve the success rate of drug discovery campaigns.

The integration of molecular dynamics, machine learning, and experimental validation creates a powerful framework for tackling flexible binding sites. Methods such as dyphAI and PharmacoForge demonstrate how ensemble-based approaches can identify novel inhibitors with validated activity, while mixed-resolution modeling strategies provide computationally efficient alternatives for studying large systems.

As these technologies continue to mature, the field moves closer to truly predictive drug design that accounts for the intrinsic dynamics of biological systems, ultimately enabling the discovery of more effective therapeutics with improved safety profiles.

The evolution of structure-based drug discovery has been marked by a fundamental recognition: biological macromolecules are not static entities. Traditional rigid docking approaches, which treat the protein target as a single, fixed conformation, often failed to account for the dynamic nature of binding sites, leading to limited success in virtual screening campaigns. This limitation sparked a historical shift toward ensemble docking, which utilizes multiple representative conformations of the target protein to better capture its flexibility. Concurrently, pharmacophore modeling evolved from static, ligand-based models to dynamic, structure-based approaches that incorporate protein flexibility. Ensemble pharmacophore modeling represents the convergence of these methodologies, creating a powerful framework for identifying and optimizing therapeutic compounds, particularly for targets with highly flexible binding sites such as nuclear hormone receptors and G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) [9] [10] [11].

The theoretical underpinning of this shift lies in the mechanism of conformational selection, where ligands selectively bind to pre-existing protein conformations that are thermodynamically favorable for binding, rather than inducing fit through structural rearrangements. This paradigm, now widely accepted, has driven methodological advances in computational drug discovery, enabling more effective screening and design of molecules that account for the intrinsic dynamics of biological targets [10].

The Limitations of Rigid Docking and the Rise of Ensemble Methods

Fundamental Challenges of Static Representations

Molecular docking, a cornerstone of structure-based virtual screening, aims to predict the preferred position, orientation, and conformation of a small molecule (ligand) when bound to a protein target. Traditional implementations treated the protein as a rigid body, allowing only the ligand full flexibility. While computationally efficient, this simplification often proved inadequate because protein binding sites can undergo significant conformational changes upon ligand binding, including side-chain rearrangements, loop movements, and backbone shifts [11].

The performance of docking depends critically on the quality of scoring functions used to distinguish true binders from non-binders. When using a single, rigid protein structure, these functions often fail to achieve satisfactory enrichment—the ability to prioritize active ligands over inactive compounds in a virtual screen. This occurs because a single structure cannot represent the diverse conformational states that can accommodate different ligands, leading to false negatives where genuine binders are incorrectly scored [12].

The Ensemble Docking Solution

Ensemble docking emerged to address these limitations by using an "ensemble" of drug target conformations, typically obtained through molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, which is then used in docking candidate ligands. This approach, now well-established in early-stage drug discovery, effectively samples the conformational landscape of the target, increasing the probability that at least one structure will provide a complementary fit for a given ligand [11].

The theoretical advantage of ensemble docking was quantitatively demonstrated in benchmark studies. For example, research showed that combining results from multiple docking programs using a novel exponential consensus ranking (ECR) method significantly outperformed traditional consensus strategies across diverse protein families. The ECR method assigns a score to each molecule based on the sum of exponential distributions of its ranks across different docking programs, creating a robust metric that is independent of score units and scales [12].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Docking Strategies Across Multiple Targets (EF2 Values)

| System | Best Single Program | Traditional Consensus | Exponential Consensus (ECR) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CDK2 | 25.4 | 28.7 | 32.1 |

| ESR1 | 31.2 | 33.5 | 36.8 |

| ADRB2 | 18.7 | 22.3 | 25.9 |

| CAH2 | 15.8 | 19.1 | 21.4 |

| Average | 22.8 | 25.9 | 29.1 |

Enrichment Factor at 2% (EF2) values demonstrate the superior performance of exponential consensus ranking across different biological targets. Data adapted from Scientific Reports [12].

Ensemble Pharmacophore Modeling: Integrating Dynamics with Molecular Recognition

From Static to Dynamic Pharmacophores

Pharmacophore models provide an abstract representation of the steric and electronic features necessary for molecular recognition: hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, charged groups, hydrophobic regions, and aromatic rings. Traditional pharmacophore modeling relied on either a set of known active ligands (ligand-based) or a single protein structure (structure-based) [13].

Ensemble pharmacophore modeling represents a significant advancement by incorporating multiple protein conformations into the pharmacophore generation process. This approach captures the dynamic pharmacophoric features that emerge across different conformational states, creating more comprehensive models that reflect the true binding environment. For highly flexible targets like the Liver X Receptor β (LXRβ), differences in ligand binding poses and interactions present challenges in identifying general binding elements. Generating pharmacophore models based on multiple ligands aligned with their binding coordinates has proven effective in such cases [9].

Methodological Framework and Workflow

The typical workflow for ensemble pharmacophore modeling integrates molecular dynamics, binding site analysis, and feature clustering:

Figure 1: Ensemble Pharmacophore Modeling Workflow. The process begins with a protein structure, generates conformational ensembles via MD simulations, identifies binding sites, extracts and clusters pharmacophore features, and produces a comprehensive model for virtual screening.

Machine Learning-Enhanced Pharmacophore Modeling

Recent advances integrate machine learning (ML) with ensemble pharmacophore approaches to identify key features associated with ligand-specific protein conformations. By leveraging pharmacophore descriptors, ML frameworks can prioritize features uniquely associated with ligand-selected conformations, enabling a mechanism-driven understanding of binding interactions [10].

In one implementation, researchers used four different ML feature selection algorithms—analysis of variance (ANOVA), mutual information (MI), recurrence quantification analysis (RQA), and Spearman correlation—to identify critical pharmacophore properties and eliminate redundant ones. This approach significantly enriched true positive ligands, improving database enrichment by up to 54-fold compared to random selection [10].

Advanced Applications and Protocol Development

Water-Based Pharmacophore Modeling for Kinase Inhibitors

An emerging specialization within ensemble approaches is water-based pharmacophore modeling, which leverages the dynamics of explicit water molecules within ligand-free, water-filled binding sites. This strategy was demonstrated in a case study targeting the ATP binding sites of Fyn and Lyn protein kinases, members of the Src family [14].

The protocol involves:

- Molecular dynamics simulations of apo kinase structures

- Generation of dynamic molecular interaction fields (dMIFs) from water molecules

- Conversion of these fields into pharmacophore features using tools like PyRod

- Virtual screening using the resulting water-based pharmacophore models

This ligand-independent strategy effectively identified novel chemotypes, including a flavonoid-like molecule with low-micromolar inhibitory activity, demonstrating the method's potential for exploring underutilized chemical and conformational space [14].

Shape-Focused Pharmacophore Models Using Graph Clustering

Another innovative approach introduces O-LAP, a C++/Qt5-based graph clustering algorithm that generates shape-focused pharmacophore models by clumping together overlapping atomic content from flexibly docked active ligands. The methodology involves:

- Filling the protein cavity with top-ranked docked active ligands

- Trimming non-polar hydrogen atoms and deleting covalent bonding information

- Clustering overlapping atoms with matching atom types into representative centroids using pairwise distance-based graph clustering

- Optional greedy search optimization using training set data

This method, benchmarked across five demanding drug targets from the DUDE-Z database, demonstrated substantial improvements in docking enrichment, effectively capturing the complementary shape of binding cavities [15].

Table 2: Key Software Solutions for Ensemble Pharmacophore Modeling

| Software/Tool | Type | Key Features | Application in Ensemble Modeling |

|---|---|---|---|

| MOE (Chemical Computing Group) | Commercial | Integrated DB-PH4 facility, SiteFinder, alpha shapes | Binding site analysis, pharmacophore feature generation from MD ensembles |

| O-LAP | Open-source (GNU GPL v3.0) | Graph clustering of overlapping ligand atoms | Generation of shape-focused pharmacophore models from docked ligands |

| PyRod | Open-source | Water-based pharmacophore generation | Conversion of water dynamics to pharmacophore features |

| BIOVIA Discovery Studio | Commercial | CATALYST pharmacophore modeling, ensemble pharmacophores | Handling diverse compound sets with multiple modes of action |

| RDKit | Open-source | Cheminformatics toolkit, fingerprint generation | Descriptor calculation, integration with ML workflows |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Ensemble Pharmacophore Generation from MD Simulations

Objective: Generate an ensemble pharmacophore model from molecular dynamics simulations of a target protein.

Materials and Methods:

- System Setup:

- Obtain protein structure from PDB (e.g., GPCR structures: ADORA2A:3EML, ADRB2:2RH1)

- Delete non-native domains and co-crystallized ligands; build missing loops

- Place protein in appropriate membrane environment (for membrane proteins) or solvation box

Molecular Dynamics Simulation:

- Use GROMACS v5.1.0 or similar MD software

- Apply coarse-grained or all-atom force fields (AMBER-ff19SB)

- Run 600-ns simulation, saving frames every 200 ps (3,000 conformations total)

- Conduct simulations under NPT ensemble (300K, 1 bar) after minimization and equilibration

Binding Site and Pharmacophore Analysis:

- Import all MD conformations into MOE or similar software

- Superpose structures based on heavy atoms of binding pocket residues

- Identify binding sites using SiteFinder (based on alpha shapes)

- Generate pharmacophore features using DB-PH4 facility with 6.5-Å cutoff from binding site

- Apply "unified scheme" pharmacophore definitions: hydrogen bond donor (Don), acceptor (Acc), cation (Cat), anion (Ani), aromatic center (Aro), hydrophobic (Hyd)

- Cluster features across all trajectories to create consensus pharmacophore model [10]

Protocol 2: Shape-Focused Pharmacophore Modeling with O-LAP

Objective: Create shape-focused pharmacophore models using graph clustering of docked ligands.

Materials and Methods:

- Ligand and Protein Preparation:

- Select active ligands and property-matched decoys from databases (e.g., DUDE-Z)

- Generate 3D conformers using LIGPREP (Schrödinger) or similar tools

- Add tautomeric states and assign partial charges (OPLS3)

Flexible Molecular Docking:

- Use docking software (PLANTS1.2, AutoDock Vina, etc.)

- Define docking center as centroid of co-crystallized ligand with 10-Å radius

- Generate multiple poses per ligand (e.g., 10 poses per ligand in PLANTS)

O-LAP Model Generation:

- Extract top-ranked docked poses of active ligands (e.g., 50 best-ranked poses)

- Remove non-polar hydrogen atoms and delete covalent bonding information

- Merge separate MOL2 entries into single input file

- Run O-LAP clustering with atom-type-specific radii:

- Apply graph clustering to group overlapping atoms

- Generate representative centroids for each cluster

- Perform enrichment-driven optimization using training set (optional)

- Validate model using separate test set of active and decoy compounds [15]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Table 3: Essential Resources for Ensemble Pharmacophore Research

| Category | Resource | Specifications/Functions | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| MD Software | GROMACS | Open-source MD package, all-atom and coarse-grained simulations | Generates conformational ensembles for flexible targets |

| Docking Tools | AutoDock Vina | Open-source docking, flexible ligand handling | Virtual screening against multiple receptor conformations |

| PLANTS | Protein-ligand docking, ChemPLP scoring function | Pose generation for O-LAP modeling | |

| Pharmacophore Modeling | MOE (Molecular Operating Environment) | DB-PH4 facility, SiteFinder, pharmacophore feature generation | Commercial solution with comprehensive modeling capabilities |

| O-LAP | Open-source (GNU GPL v3.0), graph clustering algorithm | Generates shape-focused models from docked ligands | |

| Cheminformatics | RDKit | Open-source cheminformatics, descriptor calculation, fingerprint generation | Preprocessing compounds, descriptor calculation for ML |

| DataWarrior | Open-source visualization, chemical intelligence | Interactive analysis of screening results | |

| Databases | DUDE-Z | Optimized version of DUD-E, active/decoy compounds | Benchmarking ensemble pharmacophore models |

| PharmaDB (BIOVIA) | ~240,000 receptor-ligand pharmacophore models | Off-target activity profiling, drug repurposing |

The historical shift from rigid docking to ensemble approaches represents a fundamental maturation in computational drug discovery, acknowledging and leveraging the dynamic nature of biological targets. Ensemble pharmacophore modeling stands as a powerful methodology that integrates conformational diversity with the essential features of molecular recognition. By capturing the dynamic pharmacophoric landscape of flexible binding sites, these approaches have demonstrated significant improvements in virtual screening enrichment, lead optimization efficiency, and overall success rates in structure-based drug design.

The continued integration of machine learning algorithms for feature selection, water-based pharmacophore strategies, and shape-focused modeling techniques promises to further enhance the predictive power and practical utility of ensemble approaches. As these methodologies become more accessible through both commercial and open-source implementations, they are poised to play an increasingly central role in tackling challenging drug targets, particularly those characterized by high flexibility and conformational heterogeneity.

Understanding the mechanisms by which proteins and ligands recognize and bind each other is fundamental to rational drug design. For decades, two primary models have explained these interactions: conformational selection and induced fit [16]. The distinction between these mechanisms has profound implications for drug discovery, particularly in the context of targeting proteins with flexible binding sites. Within the framework of ensemble pharmacophore modeling, discerning which mechanism governs a target's behavior directly influences the strategy for virtual screening and lead optimization [10] [17]. This application note delineates the core principles of these binding mechanisms, provides protocols for their experimental distinction, and details their critical role in developing effective pharmacophore models for flexible drug targets.

Core Principles and Quantitative Distinctions

Defining the Models

The induced fit model posits that a ligand first binds to its protein target in a reversible encounter complex, after which the protein's structure undergoes a conformational change to optimize the interaction [16]. In this scenario, the binding event induces the structural adjustment.

In contrast, the conformational selection model proposes that the unbound protein exists in a dynamic equilibrium of multiple conformations. The ligand selectively binds to and stabilizes a pre-existing, complementary conformation, thereby shifting the conformational equilibrium toward this bound state [10] [16]. An extended model incorporating elements of both mechanisms, often termed conformational selection with adjustment, is now widely accepted as a more complete description for many systems [16].

Kinetic and Thermodynamic Signatures

The two mechanisms can be distinguished by analyzing the dominant relaxation rate ((k_{obs})) as a function of total ligand concentration ([L]₀). The characteristic profiles are summarized in Table 1 and illustrated in the protocol section [18].

Table 1: Characteristic Relaxation Kinetics for Binding Mechanisms

| Binding Mechanism | Behavior of (k_{obs}) vs. [L]₀ | Key Identifying Feature | Mathematical Signature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Induced Fit | Monotonic increase under pseudo-first-order conditions; symmetric minimum at [L]₀ = [P]₀ - Kd for [P]₀ > Kd [18] | Symmetric function around [L]₀min [18] | ( k{obs} = ke + kr + \frac{1}{2}\gamma - \frac{1}{2}\sqrt{\gamma^2 + 4k-k_r} ) [18] |

| Conformational Selection | Decreases with [L]₀ for (ke < k-); exhibits a minimum for (ke > k-) and large [P]₀ [18] | Asymmetric function around [L]₀min [18] | ( k{obs} = ke + \frac{1}{2}\alpha - \frac{1}{2}\sqrt{\alpha^2 + \beta} ) [18] |

Experimental Protocols for Mechanism Discrimination

Protocol 1: Kinetic Analysis of Binding Mechanisms

Principle: This protocol determines the binding mechanism by measuring the dominant chemical relaxation rate ((k_{obs})) across a wide range of ligand and protein concentrations, moving beyond the traditional pseudo-first-order approximation [18].

Workflow:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a series of solutions with a fixed total protein concentration ([P]₀) that exceeds the overall dissociation constant (Kd). For each protein concentration, prepare a dilution series spanning a wide range of total ligand concentrations ([L]₀), from [L]₀ ≪ [P]₀ to [L]₀ ≫ [P]₀.

- Relaxation Rate Measurement: Use a stopped-flow instrument or temperature-jump apparatus to rapidly perturb the binding equilibrium of each sample. Monitor the return to equilibrium via fluorescence, absorbance, or another suitable spectroscopic technique.

- Data Fitting: Fit the observed relaxation kinetics to a single-exponential function to extract the dominant relaxation rate, (k_{obs}), for each [L]₀.

- Mechanism Identification: Plot (k{obs}) as a function of [L]₀.

- If the plot is symmetric with a minimum at [L]₀ = [P]₀ - Kd, the data support an induced fit mechanism.

- If the plot is asymmetric, or if (k{obs}) decreases monotonically with increasing [L]₀, the data support a conformational selection mechanism [18].

Protocol 2: Computational Solvent Mapping with NMR Ensembles

Principle: This protocol uses computational solvent mapping on an ensemble of ligand-free protein conformations (e.g., from NMR) to identify if pre-existing conformations possess binding sites similar to the ligand-bound state, providing evidence for conformational selection [19].

Workflow:

- Ensemble Acquisition: Obtain an ensemble of ligand-free protein conformations. Public repositories like the Protein Data Bank (PDB) contain NMR-derived ensembles suitable for this purpose [19].

- Computational Solvent Mapping: Perform mapping calculations on each conformation in the ensemble. Dock a diverse library of small molecular probes (e.g., benzene, methanol, acetate) to identify regions with high probe density (hot spots) [19].

- Hot Spot Analysis: For each protein conformation, analyze the mapping results to define the geometry and chemical features of the binding hot spots.

- Similarity Assessment: Compare the hot spots identified in the ligand-free conformations to the binding site of the known ligand-bound structure.

- Mechanism Identification:

- If one or more ligand-free conformations possess a hot spot that closely resembles the bound-state binding site in geometry and chemical features, this provides strong evidence for conformational selection [19].

- If no ligand-free conformation possesses a pre-formed, complementary binding site, the data suggest an induced fit mechanism is more likely.

Application in Ensemble Pharmacophore Modeling

Implications for Model Generation

The choice between conformational selection and induced fit directly dictates the strategy for generating pharmacophore models for virtual screening.

- For Conformational Selection Targets: The drug discovery process should leverage ensemble-based approaches. Multiple protein conformations that represent the dynamic state of the binding site should be used to generate a set of complementary pharmacophore models [10] [17]. Machine learning can be applied to prioritize pharmacophore features uniquely associated with ligand-selected conformations, improving database enrichment by up to 54-fold compared to random selection [10].

- For Induced Fit Targets: Structure-based pharmacophore generation may require techniques like Induced Fit Docking to model the structural adjustments triggered by ligand binding [20]. The resulting model will be highly specific to the ligand used for induction.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item Name | Function/Application | Relevance to Binding Mechanism Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Stopped-Flow Spectrometer | Rapid kinetic measurement of binding events after rapid mixing. | Essential for Protocol 1, enabling measurement of kobs at various [L]₀ [18]. |

| NMR-Derived Structural Ensembles | Experimentally determined ensembles of protein conformations (from PDB). | Critical input for Protocol 2; provides unbiased ensemble of unbound states [19]. |

| Site-Identification by Ligand Competitive Saturation (SILCS) | Computational method using MD simulations with probe molecules to map group-affinity patterns [21]. | Generates receptor-based pharmacophores accounting for flexibility/desolvation; useful for both mechanisms. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Software (e.g., GROMACS) | Software for simulating physical movements of atoms and molecules over time. | Generates conformational ensembles for analysis; used in SILCS and ML-based feature ranking [10] [21]. |

| O-LAP Software | Algorithm for generating shape-focused pharmacophore models via graph clustering [15]. | Creates cavity-filling models from docked active ligands, effective for docking rescoring in flexible sites. |

Discriminating between conformational selection and induced fit is not merely an academic exercise but a critical step in the rational design of drugs, especially for targets with high binding site flexibility. Kinetic analysis and computational mapping of structural ensembles provide robust experimental protocols for mechanism identification. For conformational selection-driven systems, which are common in protein-protein interactions, employing ensemble pharmacophore strategies that incorporate multiple pre-existing receptor states significantly increases the success of virtual screening campaigns. Integrating this mechanistic understanding into computational drug design workflows enables a more insightful and effective approach to discovering novel therapeutics.

The paradigm of drug discovery has progressively shifted from viewing biological targets as static entities to recognizing them as dynamic systems that sample multiple conformational states. Ensemble pharmacophore modeling is a computational approach that leverages this dynamic nature to improve the identification and optimization of active compounds, particularly for proteins with flexible binding sites. This methodology constructs a set of pharmacophore models, or an "ensemble," derived from multiple structurally distinct conformations of a target protein. The core premise is that a single static structure may not adequately represent the diverse binding modes required by different chemotypes, whereas an ensemble can capture the plasticity essential for molecular recognition [22]. This application note details the practical methodologies for sourcing these essential conformational ensembles through two powerful, complementary experimental and computational techniques: X-ray crystallography and Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations, providing a structured protocol for their application in rational drug design.

Sourcing Conformations: X-ray Crystallography vs. Molecular Dynamics

The first critical step in ensemble pharmacophore modeling is generating a diverse and relevant set of protein conformations. The two primary sources for these structures are X-ray crystallography and MD simulations, each with distinct strengths and limitations.

Conformations from X-ray Crystallography

Traditional X-ray crystallography, often performed at cryogenic temperatures (∼100 K), has been the workhorse of structural biology. However, a growing body of evidence suggests that flash-cooling crystals can introduce a significant bias, resulting in structures that are over-packed and conceal the true extent of conformational heterogeneity. Room-temperature X-ray crystallography has emerged as a powerful technique to access a more functionally relevant conformational ensemble [23]. A comparative analysis of 30 proteins revealed that cryocooling remodels the conformational distributions of more than 35% of side chains and can eliminate packing defects that are crucial for functional motions [23]. For instance, in the signaling switch protein H-Ras, an allosteric network detectable in solution by NMR was uncovered in room-temperature, but not cryogenic, electron-density maps [23].

Practical Application: Researchers can leverage the Protein Data Bank (PDB) to build ensembles. This involves:

- Identifying and retrieving multiple crystal structures of the same protein from the PDB.

- Structures should be determined under different conditions (e.g., room-temperature vs. cryogenic, different crystal forms, bound to different ligands, or apo forms).

- The collection of these independent experimental snapshots provides a foundational ensemble that captures inherent flexibility and ligand-induced plasticity [24] [17].

Conformations from Molecular Dynamics Simulations

MD simulations provide a computational means to sample the conformational landscape of a protein in silico. By numerically solving Newton's equations of motion, MD can model the time-dependent evolution of a protein's structure, capturing dynamics from femtoseconds to microseconds and beyond. This allows for the observation of transient pockets, loop motions, and allosteric shifts that may be absent in all available crystal structures [22].

The primary challenge with MD is the conformational sampling problem. The timescales required for functionally relevant conformational changes can be orders of magnitude longer than what is computationally feasible to simulate. Furthermore, the accuracy of the simulation is contingent upon the underlying molecular mechanics force field [22]. Despite these challenges, even relatively short MD simulations (tens of nanoseconds) have proven effective in sampling unseen, druggable pockets for multiple targets [22].

Practical Application: The standard protocol, known as the "relaxed complex scheme" (RCS), involves:

- Performing an MD simulation of the apo-protein or a holoprotein in solution.

- Extracting thousands of snapshots from the simulation trajectory.

- Using structural clustering techniques (e.g., based on root mean-square deviation of the binding site residues) to identify a non-redundant set of representative conformations for the ensemble [22].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Conformation Sourcing Methods

| Feature | X-ray Crystallography | Molecular Dynamics (MD) |

|---|---|---|

| Source of Conformations | Experimental snapshots from crystals | Computational simulation of motion |

| Temporal Resolution | Static snapshots | Continuous trajectory from fs to ms |

| Key Advantage | Experimental accuracy; can access room-temperature ensembles [23] | Can simulate unpredicted motions and transient states [22] |

| Primary Limitation | May be biased by crystal packing or cryo-cooling [23] [24] | Sampling limitations and potential force field inaccuracies [22] |

| Best Use Case | Building ensembles from existing structural data; capturing ligand-induced states | Exploring flexibility beyond known structures; discovering cryptic pockets |

Integrated Workflow for Ensemble Construction

A robust ensemble often combines the strengths of both experimental and computational approaches. The following workflow, depicted in the diagram below, outlines a comprehensive protocol for constructing a conformational ensemble for pharmacophore modeling.

Workflow for Ensemble Construction and Application

Protocol 1: Building an Ensemble from the PDB

Objective: To curate a diverse set of protein conformations from existing X-ray crystal structures.

- Data Curation: Search the PDB for all available structures of the target protein. Prioritize structures determined at room temperature where available [23].

- Structure Preparation: For each structure, prepare the protein by removing exogenous ligands, adding hydrogen atoms, and assigning correct protonation states using a molecular modeling suite.

- Superposition and Alignment: Align all structures to a common reference frame based on the conserved core of the protein.

- Binding Site Analysis: Calculate the root mean-square deviation (RMSD) of the residues lining the binding site of interest across all aligned structures.

- Clustering: Perform cluster analysis (e.g., using hierarchical or k-means clustering) on the binding site RMSD matrix to group structurally similar conformations.

- Ensemble Selection: Select one representative structure (e.g., the centroid) from each cluster to form the final ensemble. This ensures conformational diversity while minimizing redundancy.

Protocol 2: Building an Ensemble from MD Simulations

Objective: To generate a conformational ensemble from an MD simulation trajectory that captures the dynamic motion of the protein.

- System Setup: Begin with an initial protein structure (from PDB). Solvate it in a water box, add necessary ions to neutralize the system, and assign a suitable force field.

- Simulation: Run an MD production simulation for a timescale feasible with available computational resources (nanoseconds to microseconds). Save snapshots of the trajectory at regular intervals (e.g., every 100 ps).

- Trajectory Processing: Superimpose all snapshots from the trajectory to a reference structure to remove global rotation and translation.

- Conformational Clustering: As in Protocol 1, perform cluster analysis on the binding site residues' RMSD to identify the most populated conformational states sampled during the simulation.

- Ensemble Selection: Select the centroid structure from the most statistically significant clusters to represent the ensemble. The number of clusters can be determined by the elbow method or based on a pre-defined RMSD cutoff.

Application in Ensemble Pharmacophore Modeling & Virtual Screening

Once a conformational ensemble is established, it can be directly applied to structure-based pharmacophore modeling and virtual screening.

Generating and Using the Ensemble Pharmacophore

- Pharmacophore Generation: For each representative structure in the conformational ensemble, generate a distinct receptor-based pharmacophore model. This can be done manually by analyzing key protein-ligand interactions or automatically using tools like the Site-Identification by Ligand Competitive Saturation (SILCS) method [21]. SILCS uses MD simulations with diverse probe molecules to create 3D maps of functional group affinity, which are then converted into pharmacophore features, naturally accounting for protein flexibility and desolvation [21].

- Virtual Screening: Screen a large database of compounds against every pharmacophore model in the ensemble. A compound is considered a "hit" if it matches the features of any one model in the ensemble. This approach, known as ensemble pharmacophore-based virtual screening, significantly increases the probability of identifying chemically diverse hits that may bind to different conformational substates of the target [17].

- Hit Prioritization: Rank the hits based on their fit value to the pharmacophore models. Further prioritization can be achieved by re-scoring the hits using more computationally intensive methods, such as calculating SILCS-based ligand grid free energies (LGFE) [21] or using machine-learning scoring functions like SVMSP trained on MD structures [25].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item/Tool | Function in Ensemble Modeling |

|---|---|

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Primary repository for sourcing multiple experimental protein conformations [24]. |

| Molecular Dynamics Software | Software to run simulations for conformational sampling. |

| Clustering Algorithms | Identifies non-redundant representative structures from MD trajectories or PDB sets [22]. |

| SILCS (Site Identification by Ligand Competitive Saturation) | Generates target-specific pharmacophore features and affinity maps from MD simulations [21]. |

| Pharmacophore Modeling Software | Platform for building, validating, and performing virtual screening with pharmacophore models. |

| Directory of Useful Decoys (DUD) | Database of active compounds and decoys for validating virtual screening protocols [25] [21]. |

Case Study: Discovery of Novel Tubulin Inhibitors

A compelling example of this integrated approach is the discovery of novel antimitotic tubulin inhibitors. The colchicine binding site of tubulin is characterized by high flexibility and three interconnected sub-pockets, making it a challenging target for structure-based design.

Researchers constructed an ensemble pharmacophore based on more than eighty published X-ray structures of tubulin in complex with ligands bound to the colchicine site. This ensemble captured the flexible interactional space between various ligands and the target. They then performed a virtual screening of a ZINC sub-library using this ensemble of pharmacophores. By combining the scaffolds that best fit the ensemble pharmacophore representation, they designed a new family of ligands. This led to the synthesis of a novel tetrazole-based compound (5) that satisfied the ensemble requirements. Experimental validation confirmed that compound 5 demonstrated micromolar activity against in vitro tubulin polymerization and a nanomolar anti-proliferative effect against human cancer cells, successfully disrupting cellular microtubules [17]. This case underscores the power of ensemble pharmacophore modeling for flexible protein targets.

Key Advantages for Targeting Interconnected and Allosteric Pockets

Allosteric regulation is a fundamental biological process where the binding of an effector molecule at one site (the allosteric site) topographically distinct from the active (orthosteric) site influences the activity and function of a protein at a distant location [26]. The pharmaceutical industry's interest in allosteric drug discovery has grown substantially, driven by the unique therapeutic advantages allosteric modulators offer over traditional orthosteric drugs [26] [27] [28]. These advantages include greater selectivity for specific protein subtypes, reduced off-target effects, and the potential to fine-tune protein activity rather than completely inhibit or activate it [26] [28]. Exploiting these benefits requires a deep understanding of the dynamic and interconnected nature of protein pockets and the development of sophisticated computational methods to identify and characterize them.

This application note details the key advantages of targeting interconnected and allosteric pockets, framed within the context of ensemble pharmacophore modeling. We provide a quantitative comparison of allosteric versus orthosteric targeting, detailed protocols for identifying dynamic allosteric pockets, and visualizations of the integrated workflows that combine multiple computational techniques to enhance the success of allosteric drug discovery campaigns.

Quantitative Advantages of Allosteric Targeting

The strategic value of allosteric sites in drug discovery is underscored by several distinct pharmacological benefits. Table 1 summarizes the core advantages compared to orthosteric targeting.

Table 1: Key Advantages of Targeting Allosteric Pockets over Orthosteric Pockets

| Advantage | Description | Impact on Drug Discovery |

|---|---|---|

| Enhanced Selectivity | Allosteric sites are less evolutionarily conserved than orthosteric sites across protein families [26] [28]. | Enables development of highly selective modulators for specific protein subtypes, reducing off-target toxicity [26]. |

| Functional Tunability | Allosteric modulators can fine-tune protein function (e.g., partial agonism, biased signaling) rather than simple on/off inhibition [27] [29]. | Potential for nuanced pharmacological effects and safer therapeutics with a ceiling on their effect [28] [30]. |

| Saturability of Effect | The allosteric effect is saturable due to its dependence on cooperativity with the orthosteric site [28]. | Provides a built-in safety margin, as the effect reaches a maximum even with increasing drug dose [28]. |

| Ability to Target "Undruggable" Sites | Allows modulation of proteins where the orthosteric site is flat, highly charged, or otherwise unsuitable for high-affinity drug binding [26]. | Expands the universe of druggable targets, including those previously considered intractable. |

The growing importance of this field is reflected in the scientific literature. A review of PubMed abstracts shows that publications mentioning "allostery" or "allosteric" have grown at a doubling rate of 10.8 years since 1990, outpacing the overall growth of PubMed itself [26]. Furthermore, publications focusing on allosteric drug discovery in major medicinal chemistry journals have seen a remarkable doubling rate of approximately 6.6 years since 2005 [26].

Integrated Workflow for Allosteric Pocket Identification

Accurate identification of allosteric pockets is a critical first step. These pockets are often hidden (cryptic) in static, apo protein structures and become evident only through conformational changes, making their prediction challenging [31] [32]. A robust, multi-technique approach that integrates static, dynamic, and evolutionary information significantly improves prediction success.

Figure 1 illustrates a validated workflow that combines molecular dynamics (MD), pocket detection, coevolution analysis, and machine learning to prioritize hidden allosteric sites reliably.

Figure 1: Integrated workflow for predicting hidden allosteric pockets. The process begins with a static protein structure and uses MD simulations to sample conformational states. Pockets detected across the ensemble are then scored and prioritized based on druggability, coevolutionary signals, and perturbation of protein dynamics before a final machine learning model ranks the most promising allosteric sites [31] [32] [30].

Protocol 1: Generating a Conformational Ensemble via Molecular Dynamics

Objective: To generate an ensemble of protein conformations to reveal hidden or transient allosteric pockets not visible in the static crystal structure.

Materials:

- Software: GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD, or related MD simulation package.

- Input: High-resolution protein structure (e.g., from PDB). Prefer structures with resolution better than 3.0 Å [32].

- System Setup: Solvation box (e.g., TIP3P water model), ions for neutralization, and appropriate force field (e.g., CHARMM, AMBER).

Method:

- System Preparation: Prepare the protein structure by adding missing atoms/residues and assigning protonation states using tools like PDB2PQR or the MD software's preprocessing suite.

- Solvation and Neutralization: Immerse the protein in a solvation box and add ions to neutralize the system's charge.

- Energy Minimization: Perform energy minimization (e.g., using steepest descent) until the maximum force is below a chosen threshold (e.g., 1000 kJ/mol/nm) to remove steric clashes.

- Equilibration: Conduct a two-stage equilibration in the NVT (constant Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature) and NPT (constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature) ensembles to stabilize the system's temperature and density.

- Production MD: Run a production simulation for a duration sufficient to capture relevant conformational changes. A 500 ns simulation has been successfully used to identify hidden allosteric pockets in proteins like LFA-1 and p38-α [31]. Save molecular snapshots at regular intervals (e.g., every 100 ps) to build the conformational ensemble.

Protocol 2: Pocket Detection, Druggability Scoring, and Coevolution Analysis

Objective: To identify, characterize, and filter potential binding pockets from the MD ensemble.

Materials:

Method:

- Pocket Detection: Run Fpocket on the static crystal structure and MDpocket on the entire MD trajectory or a representative subset of snapshots. MDpocket calculates the opening frequency and volume of pockets over time [31].

- Druggability Scoring: Calculate a Druggability Score (DS) for each detected pocket. The DS typically ranges from 0 to 1, with pockets scoring above 0.5 considered potentially druggable [31]. Rank the pockets based on their DS.

- Coevolution Analysis (Optional but Recommended): Perform Statistical Coupling Analysis (SCA) using a multiple sequence alignment (MSA) of the protein's homologs. Calculate a Coverage Score (CS), which is the percentage of coevolving amino acids within a pocket [31]. Pockets with high CS are likely functionally important and are strong allosteric candidates.

Ensemble Pharmacophore Modeling for Allosteric Sites

Once a potential allosteric pocket is identified, structure-based pharmacophore modeling can abstract its key interaction features to guide virtual screening and lead optimization. Traditional methods using a single static structure are limited. Ensemble pharmacophore modeling, which incorporates multiple conformations from MD simulations, accounts for pocket flexibility and delivers superior results [21] [11].

Protocol 3: Developing an Ensemble Pharmacophore Model with SILCS-Pharm

Objective: To create a robust, ensemble-based pharmacophore model that accounts for protein flexibility and desolvation effects.

Materials:

- Software: Site Identification by Ligand Competitive Saturation (SILCS) suite [21].

- Input: The conformational ensemble from Protocol 1.

Method:

- SILCS Simulation: Run Grand Canonical Monte Carlo (GCMC)/MD simulations for the protein in an aqueous solution containing a diverse set of probe molecules: benzene (aromatic/hydrophobic), propane (aliphatic), methanol (neutral H-bond donor/acceptor), formamide (neutral H-bond donor/acceptor), acetaldehyde (H-bond acceptor), methylammonium (positive ion), and acetate (negative ion) [21].

- FragMap Generation: Process the simulation trajectories to compute 3D probability maps of the probe locations. Convert these maps into Grid Free Energy (GFE) FragMaps via Boltzmann inversion. These FragMaps represent the affinity of different functional groups for every region around the protein [21].

- Feature Identification and Clustering: Select voxels from the GFE FragMaps that exceed a favorable free energy cutoff. Cluster these voxels to define distinct FragMap features representing potential interaction sites.

- Pharmacophore Hypothesis Generation: Convert the FragMap features into standard pharmacophore features (e.g., Hydrogen Bond Acceptor (HBA), Hydrogen Bond Donor (HBD), Hydrophobic (H)) based on the probe types. A feature grid free energy (FGFE) score is used to prioritize the most energetically favorable features [21]. The final model is a 3D spatial arrangement of these selected features, which can include exclusion volumes to define the shape of the binding site.

Table 2 outlines the key research reagents and computational tools essential for implementing the described protocols.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Allosteric Pocket Identification and Pharmacophore Modeling

| Reagent / Software Tool | Type | Primary Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS/AMBER | MD Software | Generates conformational ensembles from initial protein structures (Protocol 1) [31]. |

| Fpocket / MDpocket | Pocket Detection Algorithm | Identifies and analyzes potential binding pockets in static structures and MD ensembles (Protocol 2) [31] [30]. |

| SILCS | Pharmacophore Modeling Suite | Generates grid free energy (GFE) maps from MD with multiple probes to build ensemble pharmacophore models (Protocol 3) [21]. |

| Allosteric Site Database (ASD) | Data Resource | Provides curated data on known allosteric sites for model training and validation [32] [28]. |

| Druggability Score (DS) | Computational Metric | Scores the likelihood of a pocket binding drug-like molecules (Protocol 2) [31]. |

| Coverage Score (CS) | Computational Metric | From SCA, quantifies the fraction of coevolving residues in a pocket, indicating functional importance (Protocol 2) [31]. |

Targeting interconnected and allosteric pockets represents a powerful strategy in modern drug discovery, offering unparalleled selectivity and functional control. The experimental protocols and the integrated workflow detailed in this application note demonstrate that overcoming the challenges of hidden and dynamic allosteric sites is achievable through a synergistic approach. By combining the conformational sampling of MD, the analytical power of pocket detection and coevolution analysis, and the functional abstraction of ensemble pharmacophore modeling, researchers can systematically identify and characterize novel allosteric sites with high confidence. This multi-faceted methodology, centered on ensemble-based principles, provides a robust framework for expanding the therapeutic toolkit and developing the next generation of allosteric drugs.

Building and Applying Dynamic Pharmacophore Models: A Step-by-Step Guide

The biological function of a protein is determined not by a single, static three-dimensional structure but by its dynamic properties, which give rise to a conformational ensemble [33]. Characterizing these ensembles is crucial for a mechanistic understanding of protein activity and regulation, with significant impacts on biomedical sciences, biotechnology, and drug design [33]. This application note details established and emerging methodologies for generating and analyzing conformational ensembles, with a specific focus on their application within ensemble pharmacophore modeling for flexible binding sites. We provide detailed protocols for molecular dynamics (MD) simulations and subsequent clustering techniques, which together form the foundation for capturing the dynamic behavior of proteins, particularly for intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) and flexible binding sites that represent promising yet challenging drug targets.

Molecular Dynamics Simulations for Ensemble Generation

Molecular dynamics simulations serve as a computational workhorse for generating dynamic structural ensembles of proteins at atomistic resolutions. MD simulations sample possible configurations of a molecular system to identify energetically favorable regions in conformational space, thereby providing insights into protein dynamics and conformational transitions [33] [34].

Fundamental MD Protocol

The following protocol outlines a typical all-atom MD simulation setup for generating a conformational ensemble, adaptable for both structured proteins and IDPs.

Step 1: System Preparation

- Initial Structure: Obtain a starting structure from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) or from computational models. For IDPs, this may be an extended structure or a model from a database.

- Force Field Selection: Choose an appropriate force field. For IDPs, recent specialized force fields such as those described in [35] (e.g., CHARMM36m, AMBER ff99SBdisp) are recommended. For structured proteins, GROMOS96 43a2 [36] or modern AMBER/CHARMM variants are suitable.

- Solvation: Place the protein in an octahedral or cubic box with explicit solvent molecules, such as the SPC (Simple Point Charge) water model [36]. Ensure a minimum distance (e.g., 1.2 nm) between the protein and the box boundaries.

- Neutralization: Add counter ions (e.g., Na⁺, Cl⁻) to neutralize the system's total charge.

Step 2: Energy Minimization

- Perform a short energy minimization (e.g., 100-1000 steps of steepest descent) to relieve any steric clashes introduced during solvation and system building. Convergence is typically reached when the maximum force is below a threshold (e.g., 1000 kJ/(mol·nm)) [36].

Step 3: System Equilibration

- Equilibrate the system in the NVT (constant Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature) ensemble, gradually heating the system from a low temperature (e.g., 10 K) to the target temperature (e.g., 300 K) [37].

- Further equilibrate in the NPT (constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature) ensemble to adjust the density of the system. Use a Berendsen thermostat at the target temperature with a coupling period (e.g., 0.1 ps) [36].

Step 4: Production MD

- Run a production simulation in the NPT ensemble for a duration sufficient to sample the relevant conformational space. For many functional motions, this can range from nanoseconds to microseconds, or longer for IDPs or large conformational changes. Use an integration time step of 2 fs [36].

- Constrain all bond distances in the protein using the LINCS algorithm [36] and water internal degrees of freedom using the SETTLE algorithm [36].

- Calculate long-range electrostatic interactions using the Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) summation method [36]. Save trajectory frames at regular intervals (e.g., every 1-100 ps) for subsequent analysis.

Advanced Sampling and Machine Learning Approaches

Standard MD simulations can be computationally limited for sampling large-scale transitions or heterogeneous IDP ensembles. The following advanced methods address this bottleneck:

- Enhanced Sampling: Techniques such as Replica Exchange Solute Tempering (REST) [35] and hybrid tempering (REHT) [35] improve conformational sampling, especially for IDPs.

- Machine Learning-Generated Ensembles: Generative models, such as Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), can directly produce physically realistic conformational ensembles at a negligible computational cost after training. The idpGAN model, for instance, is a conditional generative model based on a transformer architecture that can predict sequence-dependent coarse-grained ensembles for novel sequences, demonstrating significant transferability beyond its training data [33].

- Coarse-Grained (CG) Simulations: To access longer timescales, CG models like the Cα-based model used to train idpGAN [33] or the ABSINTH model [33] [35] can be employed. These models reduce the number of degrees of freedom, thereby accelerating sampling.

Clustering Techniques for Conformational Analysis

The massive datasets generated by MD simulations (often comprising tens to hundreds of thousands of structures) necessitate robust clustering techniques to parse heterogeneous ensembles into structurally and functionally meaningful subgroups. The table below summarizes the key clustering algorithms used in conformational ensemble analysis.

Table 1: Key Clustering Algorithms for Conformational Ensemble Analysis

| Algorithm | Type | Key Principle | Strengths | Ideal Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GROMOS [35] | Geometric, RMSD-based | Monte-Carlo algorithm using RMSD to partition structures around central conformers. | Simple, widely used for folded proteins with a reference structure. | Clustering ensembles of folded proteins with a stable native state. |

| K-means [38] | Geometric, Partitioning | Partitions n conformations into k clusters based on feature space proximity (e.g., dihedrals, distances). |

Computationally efficient, simple to implement. | Creating pharmacophore ensembles from fragment-flooded structures [38]. |

| Butina [39] | Geometric, Density-based | Clusters conformations based on the number of neighbors within a specified RMSD or similarity cutoff. | Does not require pre-defining the number of clusters; good for dense datasets. | Pre-processing ligand datasets for pharmacophore modeling [39]. |

| Self-Organising Maps (SOM) [36] | Neural Network, Topology-based | Uses unsupervised learning to project high-dimensional data onto a low-dimensional (2D) topological map. | Excellent for visualization and comparing multiple trajectories; preserves topology. | Analyzing and comparing conformational dynamics of protein domains and mutants [36]. |

| t-SNE [35] | Dimensionality Reduction & Clustering | Non-linear technique that embeds high-dimensional data into 2D/3D, preserving local neighborhoods. | Superior for disentangling multiple manifolds; ideal for heterogeneous IDP ensembles. | Identifying representative sub-states within highly heterogeneous IDP ensembles [35]. |

Detailed Protocol: t-SNE Clustering for IDP Ensembles

Given the critical challenge of analyzing IDP ensembles, we provide a detailed protocol for t-SNE clustering, which has proven highly effective for these systems [35].

Step 1: Feature Extraction

- From the MD trajectory, extract a feature vector for each conformation (snapshot). Common features include:

- Inter-atomic Distance Matrices: Calculate the all-pair Cα or backbone atom distances for each snapshot. This provides an E(3)-invariant (translation, rotation, and reflection invariant) description of the conformation [33].

- Dihedral Angles: The φ and ψ backbone dihedral angles for each residue.

- Global Features: Radius of gyration (Rg), end-to-end distance, etc.

- Format the data into a 2D array of dimensions (Nconformations × Nfeatures).

Step 2: Dimensionality Reduction with t-SNE

- Standardize the feature matrix by removing the mean and scaling to unit variance.

- Apply the t-SNE algorithm to project the high-dimensional feature vectors into a 2-dimensional space. Key parameters to optimize include:

- Perplexity: Should be chosen based on dataset size (typical values: 5-50).

- Learning Rate: Usually between 10 and 1000.

- Number of iterations: Ensure convergence (typically > 1000).

- The output is a 2D scatter plot where each point represents a single protein conformation, and the proximity of points reflects their structural similarity in the original high-dimensional space.

Step 3: Cluster Identification and Validation

- In the 2D t-SNE projection, apply a clustering algorithm like K-means or DBSCAN to identify discrete conformational microstates.

- Validate the clusters by analyzing the structural properties (e.g., Rg, contact maps) of the conformations within each cluster to ensure they are homogeneous and distinct from other clusters.

- Quantify the population of each cluster, as population shifts upon ligand binding can reveal mechanisms of action and specificity [35].

The following diagram illustrates the workflow for t-SNE clustering of conformational ensembles.

Application in Ensemble Pharmacophore Modeling

The conformational ensembles generated and clustered via the above methods are directly applicable to structure-based pharmacophore modeling, moving beyond the limitations of single-structure approaches.

Workflow Integration:

- Ensemble Generation: Perform an MD simulation of the target protein, focusing on a flexible binding site or an entire IDP.

- Clustering: Use t-SNE or SOM clustering to group the trajectory into representative conformational states.

- Pharmacophore Feature Mapping: For each major cluster, generate a pharmacophore model. The Site-Identification by Ligand Competitive Saturation (SILCS) method is particularly powerful here, as it uses MD simulations with diverse probe molecules (e.g., benzene, methanol, formamide, acetate) to map 3D functional group affinity patterns (FragMaps) on the protein surface, naturally accounting for protein flexibility and desolvation effects [21].

- Hypothesis Generation: Convert these FragMaps into pharmacophore features (e.g., hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, aromatic, hydrophobic) to create multiple, structure-based pharmacophore hypotheses [21].

- Ensemble Screening: Employ these multiple pharmacophore models in virtual screening, either by screening against each model independently and combining results or by using ensemble learning methods (e.g., voting, stacking) to balance the strengths of individual models [39].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Ensemble Generation and Analysis

| Category | Reagent / Software / Resource | Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simulation Suites | GROMACS [36], AMBER [37] | Performs MD simulations; energy minimization; trajectory analysis. | Open-source (GROMACS); GPU-accelerated; extensive analysis tools. |

| Force Fields | GROMOS96 43a2 [36], ff99SB [37], CHARMM36m, AMBER ff99SBdisp [35] | Defines potential energy functions and parameters for the molecular system. | Specialized versions for IDPs (e.g., ff99SBdisp); compatible with water models. |

| Generative Models | idpGAN [33] | Directly generates conformational ensembles using machine learning. | Transformer architecture; fast sampling; transferable to new sequences. |