Ensemble Methods for Cancer Classification: Enhancing Accuracy and Interpretability in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of ensemble machine learning methods for cancer classification, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Ensemble Methods for Cancer Classification: Enhancing Accuracy and Interpretability in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of ensemble machine learning methods for cancer classification, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational principles explaining why ensemble models outperform single classifiers by reducing overfitting and capturing complex, nonlinear relationships in high-dimensional biomedical data. The scope extends to detailed methodologies including stacking, bagging, and boosting, with applications across diverse data types such as gene expression, multiomics, and histopathology images. The article further addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization strategies for handling class imbalance and high-dimensionality and concludes with rigorous validation frameworks and comparative analyses demonstrating state-of-the-art performance metrics, positioning ensemble methods as indispensable tools for precise oncology and biomarker discovery.

Why Ensemble Methods? Overcoming the Limitations of Single Classifiers in Oncology

The Critical Need for Accurate Cancer Classification in Modern Healthcare

Accurate cancer classification is a cornerstone of modern oncology, directly influencing diagnostic precision, treatment selection, and ultimately, patient survival. The complex heterogeneity of cancer necessitates classification systems that move beyond traditional histology to integrate molecular and genomic characteristics. Ensemble methods, which combine multiple machine learning models, have emerged as a powerful approach to enhance the accuracy and robustness of cancer classification. These methods integrate diverse data types—including genomic, imaging, and clinical data—to create a more comprehensive predictive model than any single algorithm could achieve alone. This document provides application notes and detailed protocols for implementing ensemble-based classification frameworks, designed for researchers and drug development professionals working to translate computational advances into clinical utility.

Recent studies demonstrate that ensemble methods consistently achieve high performance in discriminating between cancer types and subtypes. The following table summarizes quantitative results from key experiments.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Recent Ensemble Classification Models

| Cancer Focus | Data Type(s) | Ensemble Method | Key Performance Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Five Common Cancers (e.g., Breast, Colorectal) | RNA-seq, Somatic Mutation, DNA Methylation | Stacking Ensemble (SVM, KNN, ANN, CNN, RF) | Accuracy: 98% (Multiomics) vs 96% (single-omic) | [1] |

| Lung Cancer (Multiclass) | CT Scan Images | Hybrid CNN-SVD Feature Extraction + Voting Ensemble (SVM, KNN, RF, GNB, GBM) | Accuracy: 99.49%, AUC: 99.73%, Precision: 100%, Recall: 99%, F1-Score: 99% | [2] |

| Lung Cancer (Binary) | CT Scan Images | Same as above | All performance indicators: 100% | [2] |

| Six Tumor Types | DNA Methylation | GC-Forest with Intelligent SMOTE | High sensitivity for minority class while maintaining overall accuracy | [3] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Multiomics Data Integration Using a Stacking Ensemble

This protocol outlines the methodology for classifying five common cancer types by integrating RNA sequencing, somatic mutation, and DNA methylation data within a stacking ensemble framework [1].

Applications and Use Cases

- Primary Application: Classifying common cancer types (e.g., breast, colorectal, thyroid) in a primary care or diagnostic setting.

- Research Use: Investigating the complementary value of different omics data types in understanding cancer biology.

- Data Integration: Serving as a template for building robust classifiers that fuse high-dimensional, heterogeneous biological data.

Materials and Reagents

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Multiomics Analysis

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) | Source of RNA sequencing data for various cancer types [1]. |

| LinkedOmics Database | Source of somatic mutation and DNA methylation data corresponding to TCGA samples [1]. |

| Python 3.10+ | Programming language and environment for implementing the ensemble model [1]. |

| Transcripts Per Million (TPM) | Normalization method for RNA-seq data to eliminate technical bias and enable cross-sample comparison [1]. |

| Autoencoder | A deep learning technique used for non-linear dimensionality reduction and feature extraction from high-dimensional RNA-seq data [1]. |

Procedure

Data Acquisition and Cleaning:

- Download RNA-seq, somatic mutation, and DNA methylation data for the target cancer types from TCGA and LinkedOmics.

- Perform data cleaning to remove cases with missing or duplicate values (approximately 7% of data may be removed).

Data Preprocessing and Normalization:

- For RNA-seq data, apply TPM normalization using the formula:

TPM = (10^6 * reads mapped to transcript / transcript length) / (sum(reads mapped to transcript / transcript length))[1]. - Somatic mutation data is typically binary (0 or 1), indicating the presence or absence of a mutation.

- DNA methylation data consists of continuous values, often ranging from -1 to 1.

- For RNA-seq data, apply TPM normalization using the formula:

Feature Extraction:

- To address the high dimensionality of RNA-seq data, employ an autoencoder for feature extraction. The encoder compresses the input data into a lower-dimensional code, which the decoder then uses to reconstruct the input. The compressed code layer represents the extracted features.

Ensemble Model Training and Stacking:

- Base-Level Models: Train five distinct base classifiers on the preprocessed multiomics data: Support Vector Machine (SVM), k-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), Artificial Neural Network (ANN), Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), and Random Forest (RF).

- Meta-Learner: Use the predictions from these base models as input features to train a final meta-learner (which can be another classifier like logistic regression) to produce the ultimate classification.

Model Validation:

- Validate the stacked ensemble model using rigorous techniques such as k-fold cross-validation on a held-out test set to report final performance metrics like accuracy, precision, and recall.

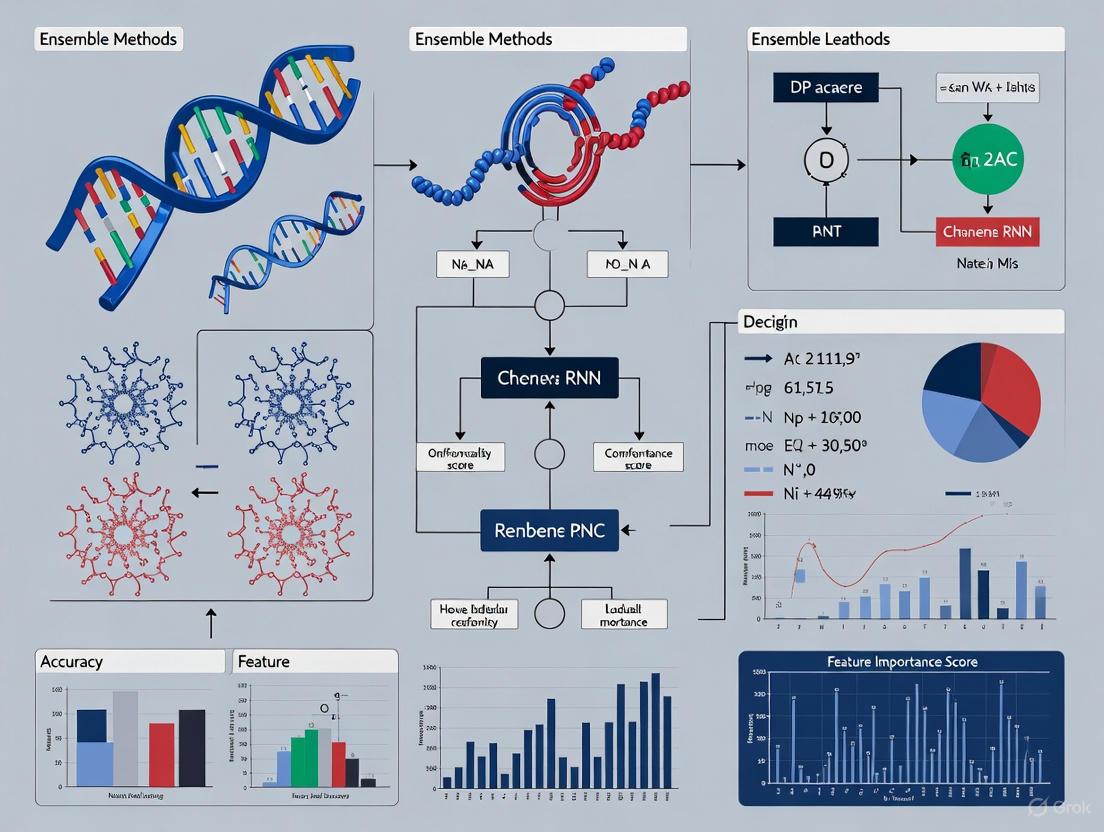

Workflow Visualization

Protocol 2: Hybrid CNN-SVD Ensemble for Medical Image Classification

This protocol describes a novel approach for lung cancer classification from CT scans that combines deep learning feature extraction with singular value decomposition (SVD) and a voting ensemble [2].

Applications and Use Cases

- Medical Imaging: Precise classification of lung cancer subtypes (e.g., adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma) from CT scans.

- Feature Engineering: A robust method for extracting and refining the most salient features from complex image data.

- Model Interpretability: Using explainable AI (XAI) techniques to build trust and provide insights for clinical decision-making.

Materials and Reagents

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Image-Based Classification

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Public Chest CT Scan Dataset | Curated dataset of lung cancer CT images for model development and testing [2]. |

| Contrast-Limited Adaptive\nHistogram Equalization (CLAHE) | Preprocessing technique to enhance image contrast with minimal noise amplification [2]. |

| Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) | Deep learning model used for automatic feature extraction from image data [2]. |

| Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) | A linear algebra technique for dimensionality reduction and feature selection [2]. |

| Gradient-weighted Class Activation\nMapping (Grad-CAM) | An explainable AI (XAI) technique to visualize regions of the image most influential to the model's prediction [2]. |

Procedure

Image Preprocessing:

- Apply Contrast-Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalization (CLAHE) to the input CT scans. This enhances contrast, making distinctive features more prominent while minimizing noise.

Hybrid Feature Extraction with CNN-SVD:

- CNN Feature Maps: Pass the preprocessed images through a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN). Extract the feature maps from a deep layer within the network.

- Dimensionality Reduction with SVD: Apply Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) to the flattened CNN feature maps. SVD decomposes the feature matrix, allowing you to select the top-k singular vectors (those with the highest singular values) as the most informative, compressed feature set.

Voting Ensemble Classification:

- The optimized features from the CNN-SVD process are used to train a diverse set of machine learning classifiers. The study used SVM, KNN, RF, Gaussian Naive Bayes (GNB), and Gradient Boosting Machine (GBM).

- A voting ensemble combines the predictions of these individual classifiers. In hard voting, the final class prediction is the one that receives the majority of votes.

Model Interpretation with Explainable AI (XAI):

- Implement Grad-CAM on the original CNN model. This technique uses the gradients of the target class flowing into the final convolutional layer to produce a heatmap highlighting the important regions in the image for predicting that class.

Workflow Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table consolidates key resources referenced across the featured protocols and broader literature, providing a quick reference for researchers in this field.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Ensemble-Based Cancer Classification

| Category | Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Data Sources | The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) | Comprehensive public repository containing molecular and clinical data for over 20,000 primary cancer samples across 33 cancer types [1]. |

| LinkedOmics | Publicly accessible database providing multiomics data from all 32 TCGA cancer types, used for sourcing somatic mutation and methylation data [1]. | |

| Computational Tools | Python | Primary programming language for implementing machine learning and deep learning models, data preprocessing, and analysis [1]. |

| Autoencoder | A type of neural network used for unsupervised feature learning and non-linear dimensionality reduction of high-dimensional data like RNA-seq [1]. | |

| Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) | A matrix factorization technique used for dimensionality reduction and feature selection from complex data structures like CNN feature maps [2]. | |

| Experimental Techniques | Intelligent SMOTE | An oversampling technique used to address class imbalance in datasets by generating synthetic samples for the minority class [3]. |

| Grad-CAM | An explainable AI technique that produces visual explanations for decisions from CNN-based models, crucial for clinical interpretability [2]. |

Ensemble learning is a machine learning paradigm that strategically combines multiple base models, often called "weak learners," to create a composite model that delivers superior predictive performance, enhanced stability, and greater robustness than any of its individual components. In the high-stakes field of cancer classification research, where diagnostic accuracy directly impacts clinical decision-making, the ability of ensemble methods to mitigate overfitting and improve generalization is particularly valuable [4]. The core principle is that a collection of models, when properly combined, can compensate for individual errors, leading to more reliable and accurate predictions on complex, high-dimensional biomedical data [5].

This approach is especially potent for tackling challenges inherent to cancer datasets, such as class imbalance (e.g., rare cancer subtypes versus more common ones), heterogeneity in tumor characteristics, and the "curse of dimensionality" often encountered with genomic and radiomic features [6]. By leveraging the strengths of diverse algorithms, ensemble methods provide researchers and clinicians with a more powerful and trustworthy tool for tasks ranging from early detection to prognosis prediction.

Core Principles and Methodologies of Ensemble Learning

The enhanced performance of ensemble learning rests on three foundational principles: the reduction of variance, the minimization of bias, and the expansion of the overall predictive space. By combining models that make different, uncorrelated errors, the ensemble can arrive at a more accurate and stable consensus, much like a wise crowd often outperforms a single expert. The most common strategies for building ensembles are Bagging, Boosting, and Voting, each with a distinct mechanism for aggregating predictions.

Table 1: Core Ensemble Learning Methodologies

| Methodology | Core Mechanism | Key Advantage | Common Algorithms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bagging | Trains multiple instances of the same model in parallel on different data subsets via bootstrap sampling [4]. | Significantly reduces model variance and overfitting, excellent for high-variance models like decision trees. | Random Forest [4] |

| Boosting | Trains models sequentially, where each new model focuses on correcting the errors of its predecessors [4]. | Reduces both bias and variance, often achieving very high predictive accuracy. | XGBoost, LightGBM, AdaBoost, CatBoost [6] [4] |

| Voting / Stacking | Combines predictions from multiple, often different, base models by averaging (regression) or majority vote (classification) [4]. | Leverages the unique strengths of diverse model architectures for improved robustness. | Voting Classifier, Stacked Generalization |

Performance and Robustness in Cancer Classification

Empirical evidence from recent cancer classification studies consistently demonstrates the superiority of ensemble methods over single-model approaches. The performance gains are measurable not only in raw accuracy but also in critical metrics like AUC (Area Under the ROC Curve), F1-score, and robustness to class imbalance, which is a common challenge in medical datasets.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance of Ensemble Models in Cancer Research

| Study & Application | Ensemble Model(s) Used | Key Performance Metrics | Reported Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biomarker-Based Cancer Classification [6] | Pre-trained Hyperfast Ensemble, XGBoost, LightGBM | AUC: 0.9929 (BRCA vs. non-BRCA) | Robustness on highly imbalanced datasets; state-of-the-art accuracy with only 500 features. |

| Lung Tumor Detection from CT Scans [5] | Reinforcement Learning-based Dynamic CNN Ensemble | Accuracy: 99.55%, 97.22%, 99.94% on three datasets. F1-Score: ≈1.0 | Superior domain adaptability and cross-dataset robustness. |

| Rectal Cancer Tumor Deposit Prediction from MRI [4] | Voting-Ensemble Learning Model (VELM) | AUC: 0.875, Accuracy: 0.800 (Testing Cohort) | Superior net benefit in decision curve analysis and clear feature clustering. |

The robustness of ensemble methods is twofold. First, they exhibit greater stability against overfitting, especially when individual models are trained on resampled data or with regularization [4]. Second, they specifically improve performance on minority classes. For instance, a pre-trained Hyperfast ensemble was shown to provide prior-insensitive decisions under bounded bias and yield minority-error reductions under mild error diversity, making it particularly suitable for detecting rare cancer types [6]. Furthermore, dynamic ensemble methods that use reinforcement learning to adaptively select and weight classifiers have shown remarkable cross-domain robustness, maintaining high performance across datasets with different distributions [5].

Experimental Protocols for Ensemble Construction

Implementing an effective ensemble model requires a systematic and rigorous protocol. The following workflow, adapted from state-of-the-art research in cancer diagnostics, outlines the key steps from data preparation to model evaluation, with a focus on a voting ensemble for a classification task such as predicting tumor deposits from medical images [4].

Protocol 4.1: Voting Ensemble for Cancer Classification

Objective: To construct a robust predictive model for a binary or multi-class cancer classification task (e.g., malignant vs. benign, or cancer subtype classification) by combining multiple machine learning classifiers.

Materials: Python environment (v3.9+), scikit-learn, XGBoost, LightGBM, PyRadiomics (if using radiomic features), ITK-SNAP for segmentation.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Data Preparation and Feature Extraction

- Data Sourcing: Collect and de-identify patient data, ensuring ethical approval. Define clear inclusion and exclusion criteria for the cohort.

- Region of Interest (ROI) Segmentation: Manually or automatically segment tumors from medical images (e.g., MRI, CT) using software like ITK-SNAP. This should be performed by multiple readers to assess inter-observer variability.

- Feature Extraction: Use a standardized library like PyRadiomics to extract a high-dimensional set of quantitative features (e.g., shape, texture, wavelet features) from the segmented ROIs. For genomic data, this could involve normalized expression levels of key biomarkers.

- Data Preprocessing: Normalize the feature matrix using Z-score normalization. Handle missing data through imputation or deletion. Address class imbalance in the training set only using techniques like SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique) [4].

Feature Selection

- Step 1 - Reliability Analysis: Calculate the Intra-class Correlation Coefficient (ICC) for all features if multiple segmentations exist. Retain only features with excellent reproducibility (e.g., ICC ≥ 0.8).

- Step 2 - Redundancy Reduction: Apply the Max-Relevance and Min-Redundancy (mRMR) algorithm to filter out redundant features, selecting a top-ranked subset (e.g., K=150).

- Step 3 - Regularization: Use Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) regression with 10-fold cross-validation to perform final feature selection, identifying the most predictive non-redundant features for the model.

Base Model Training and Hyperparameter Tuning

- Split the dataset into training (e.g., 70%), validation (e.g., 15%), and hold-out testing (e.g., 15%) cohorts. The validation set is used for tuning.

- Select a diverse set of 4-5 base classifiers (e.g., Random Forest, XGBoost, LightGBM, SVM, Logistic Regression).

- Independently optimize each base model using Grid Search or Randomized Search with 10-fold cross-validation on the training set, targeting maximization of AUC or balanced accuracy. The validation set can be used to evaluate the tuned models before ensemble construction.

Ensemble Construction (Voting)

- Combine the optimally tuned base models into a Voting Ensemble. Use a

VotingClassifierfrom scikit-learn. - For hard voting, the final prediction is the majority vote across all base model predictions.

- For soft voting, the final prediction is the argmax of the sum of predicted probabilities, which often yields better performance as it weights models by their confidence.

- Combine the optimally tuned base models into a Voting Ensemble. Use a

Model Evaluation and Validation

- Evaluate the final ensemble model on the held-out test set that was not used in any training or tuning steps.

- Performance Metrics: Report AUC, Accuracy, Precision, Recall (Sensitivity), Specificity, and F1-Score.

- Robustness and Clinical Utility:

- Plot calibration curves to assess the agreement between predicted probabilities and actual outcomes.

- Perform decision curve analysis (DCA) to evaluate the model's net benefit across a range of clinical decision thresholds.

- Use visualization techniques like t-SNE (t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding) to illustrate the clustering of features learned by the model.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The successful implementation of an ensemble learning project in cancer research relies on a suite of software tools, libraries, and data processing techniques. The following table details the essential "research reagents" for this computational task.

Table 3: Essential Tools and Software for Ensemble Learning Research

| Tool / Resource | Category | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Python (v3.9+) | Programming Language | The primary environment for scripting data preprocessing, model building, and analysis [4]. |

| Scikit-learn | Machine Learning Library | Provides implementations of standard classifiers (RF, SVM), ensemble methods (VotingClassifier), and vital utilities for feature selection (LASSO), preprocessing, and model evaluation [4]. |

| XGBoost / LightGBM | Boosting Algorithm | High-performance, gradient-boosting frameworks that are frequently used as powerful base learners within an ensemble [6] [4]. |

| PyRadiomics | Feature Extraction | A flexible open-source platform for extracting a large set of standardized radiomic features from medical images [4]. |

| ITK-SNAP | Image Segmentation | A specialized software tool for manual, semi-automatic, or automatic segmentation of structures in 3D medical images [4]. |

| PyTorch / TensorFlow | Deep Learning Framework | Essential for building and pre-training complex base models like Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), especially for image-based tasks [5]. |

In the field of oncology, the application of machine learning (ML) for classification and prognosis has become increasingly prevalent. However, two significant and interconnected data-related challenges consistently impede model performance: high-dimensionality and class imbalance. High-dimensionality arises in genomic data, where the number of features (e.g., genes) vastly exceeds the number of patient samples, leading to computational inefficiency and an increased risk of overfitting [7] [8]. Concurrently, class imbalance is common in prognostic tasks, such as predicting short-term survival, where the number of patients in one class (e.g., deceased) is significantly outnumbered by the other (e.g., survivors) [9] [10]. This imbalance biases classifiers toward the majority class, reducing sensitivity for detecting the critical minority class.

Ensemble methods, which combine multiple base models to improve robustness and accuracy, are particularly well-suited to tackle these challenges. Their inherent stability makes them effective for high-dimensional data, and they can be strategically paired with resampling techniques to correct for class distribution skews [9] [10]. This application note details these challenges and provides structured experimental protocols and resources for developing effective ensemble-based solutions.

The tables below summarize the core challenges and the demonstrated performance of various strategies to address them.

Table 1: Characterizing Data Challenges in Publicly Available Cancer Datasets

| Dataset | Primary Use | Sample Size | Feature Size | Imbalance Ratio | Key Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lung Cancer Detection [9] | Diagnosis | 309 | 16 | 1:7 (12.6% minority) | High Imbalance |

| SEER Colorectal Cancer (1-Year) [10] | Prognosis | Not Specified | 16 | 1:10 (9.1% minority) | Extreme Imbalance |

| Gene Expression (e.g., Microarray) [7] [8] | Classification | Small (e.g., 10s-100s) | Very High (e.g., 20,000 genes) | Varies | High-Dimensionality & Small Sample Size |

| Wisconsin Breast Cancer (WBCD) [9] | Diagnosis | 699 | 10 | 1.7:1 (34.5% minority) | Moderate Imbalance |

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Solutions on Benchmark Tasks

| Solution Strategy | Dataset / Task | Key Metric | Reported Performance | Baseline (No Solution) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hybrid Sampling (SMOTEENN) [9] | Multiple Cancer Dx/Prog | Mean Accuracy | 98.19% | 91.33% |

| LGBM + RENN Sampling [10] | 1-Year CRC Survival | Sensitivity | 72.30% | Not Reported |

| Random Forest [9] | Multiple Cancer Dx/Prog | Mean Accuracy | 94.69% | 91.33% |

| MI-Bagging Ensemble [7] | Gene Expression Classification | Accuracy | Outperforms single models | Lower in single models |

| Autoencoder + Classifier [11] | Prostate Cancer Prediction | Accuracy | Better than PCA-based | Lower with original data |

Addressing High-Dimensionality with Feature Reduction

High-dimensional data, such as gene expression profiles with over 20,000 genes, introduces noise and computational burden. Dimensionality reduction is an essential preprocessing step.

Application Note: Dimensionality Reduction for Ensemble Models

- Objective: To improve the performance and efficiency of ensemble classifiers by reducing the feature space of genomic data.

- Background: While ensemble methods like Random Forest can handle high-dimensional spaces, reducing irrelevant and redundant features mitigates overfitting and sharpens the model's focus on meaningful biological signals [12] [7].

- Experimental Workflow: The process involves transforming the original high-dimensional data into a compact, informative representation before training the ensemble model.

Protocol: Implementing an Autoencoder for Feature Extraction

Autoencoders are neural networks that learn compressed, non-linear representations of data, often outperforming linear methods like PCA [11].

- Data Preparation: Normalize the gene expression data (e.g., using min-max scaling or transcripts per million (TPM) for RNA-seq data) [13].

- Model Configuration:

- Architecture: Construct a symmetric encoder-decoder.

- Encoder: A sequence of fully connected (dense) layers that progressively reduce dimensionality (e.g., 2000 -> 500 -> 100 -> 30 units). Use ReLU activation functions.

- Bottleneck: The central layer with the lowest dimensionality (e.g., 30 units). This is the extracted feature vector.

- Decoder: A mirror of the encoder that reconstructs the input from the bottleneck (e.g., 30 -> 100 -> 500 -> 2000 units).

- Compilation: Use the Adam optimizer and Mean Squared Error (MSE) as the loss function.

- Architecture: Construct a symmetric encoder-decoder.

- Training: Train the autoencoder to minimize the reconstruction error on the training set. Implement early stopping to prevent overfitting.

- Feature Extraction: Use the trained encoder to transform the original high-dimensional training and test datasets into the lower-dimensional bottleneck representations.

- Ensemble Training: Train the ensemble classifier (e.g., a voting classifier or Random Forest) using the extracted features from the bottleneck layer.

Addressing Class Imbalance with Resampling Techniques

Class imbalance causes classifiers to be biased toward the majority class. Resampling the training data is a common and effective solution.

Application Note: Resampling for Imbalanced Cancer Prognosis

- Objective: To enhance the sensitivity of ensemble models for predicting minority class outcomes (e.g., 1-year cancer survival) by balancing the training data.

- Background: In a colorectal cancer dataset with a 1:10 imbalance ratio for 1-year survival, standard models fail to identify non-survivors. Hybrid sampling methods like SMOTEENN have been shown to achieve the highest mean performance across various cancer datasets [9].

- Experimental Workflow: Resampling is applied only to the training set during cross-validation to avoid data leakage and over-optimistic performance.

Protocol: Hybrid Sampling with SMOTEENN

This protocol combines Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE) and Edited Nearest Neighbors (ENN) to first create synthetic minority samples and then clean the resulting data [9] [10].

- Data Splitting: Split the dataset into training and testing sets. Resampling will be applied only to the training set.

- SMOTE - Oversampling:

- For each sample in the minority class, SMOTE calculates its

knearest neighbors (typically k=5). - It then synthesizes new examples along the line segments joining the original sample and its neighbors.

- This step increases the number of minority class instances to a desired level (e.g., 50% of the majority class).

- For each sample in the minority class, SMOTE calculates its

- ENN - Undersampling:

- After SMOTE, ENN is applied to remove any instances (both majority and synthetic minority) whose class label differs from the majority of its

knearest neighbors. - This "cleaning" step removes noisy and borderline instances that may confuse the classifier.

- After SMOTE, ENN is applied to remove any instances (both majority and synthetic minority) whose class label differs from the majority of its

- Model Training and Evaluation:

- Train a tree-based ensemble classifier, such as Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LGBM) or Random Forest, on the resampled data.

- Evaluate the model on the untouched test set. Prioritize metrics like Sensitivity (Recall) and F1-Score over raw accuracy due to the imbalanced nature of the test data.

Integrated Solution: Multiomics Ensemble Classification

For the most challenging scenarios, an integrated approach combining multi-modal data and advanced ensemble architectures is required.

Application Note: Stacking Ensemble for Multiomics Data

- Objective: To leverage high-dimensional data from multiple sources (multiomics) for superior cancer classification by employing a stacked ensemble model.

- Background: Different omics data types (e.g., RNA sequencing, DNA methylation, somatic mutations) provide complementary information. A stacking ensemble can non-linearly combine predictions from diverse base models, each potentially specialized for a different data type, achieving higher accuracy than any single model [13].

- Experimental Workflow: This framework manages high-dimensionality per data type and integrates predictions through a meta-learner.

Protocol: Building a Stacking Ensemble Classifier

- Data Preprocessing and Reduction:

- Process each omics data type independently. Normalize RNA-seq and methylation data. Encode somatic mutations as binary features (0/1).

- Apply feature reduction techniques (e.g., Autoencoder, PCA) to each data type to manage dimensionality [13].

- Base Model Training (Level-0):

- Split the preprocessed data into training and validation sets.

- Train a diverse set of base models (e.g., SVM, KNN, ANN, CNN, RF) on the training set. These models can be trained on different omics types or combinations thereof.

- Use k-fold cross-validation on the training set to generate "out-of-fold" predictions for each base model. These predictions form the meta-features for the next level.

- Meta-Model Training (Level-1):

- The out-of-fold predictions from all base models are combined to create a new feature matrix (the meta-features).

- A meta-learner (e.g., Logistic Regression, Linear SVM) is trained on this new matrix to learn how to best combine the predictions of the base models.

- Evaluation:

- The final stacked model is evaluated on the held-out test set. Base models make predictions on the test set, which are fed as features to the meta-learner for the final classification.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Ensemble-Based Cancer Data Analysis

| Category / Item | Specification / Example | Primary Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Public Data Repositories | ||

| The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) | https://www.cancer.gov/ccg/research/genome-sequencing/tcga | Primary source for multiomics patient data (RNA-seq, methylation, mutations). |

| SEER Program | https://seer.cancer.gov/ | Source for large-scale clinical data for survival analysis and prognosis studies. |

| UCI / Kaggle Repositories | e.g., Wisconsin Breast Cancer, Lung Cancer Detection [9] | Source for curated benchmark datasets for diagnostic model development. |

| Computational Tools & Algorithms | ||

| Dimensionality Reduction | ||

| Autoencoder (AE) | Keras, PyTorch Frameworks | Non-linear feature extraction from high-dimensional genomic data [13] [11]. |

| Principal Component Analysis (PCA) | Scikit-learn PCA |

Linear dimensionality reduction and data compression [14] [11]. |

| Mutual Information (MI) | Scikit-learn mutual_info_classif |

Filter-based feature selection to identify informative genes [7]. |

| Resampling Techniques | ||

| SMOTE | Imbalanced-learn SMOTE |

Synthetic oversampling of the minority class to balance datasets [9] [10]. |

| Edited Nearest Neighbors (ENN/RENN) | Imbalanced-learn EditedNearestNeighbours |

Cleans data by removing noisy majority class instances after oversampling [10]. |

| Ensemble Classifiers | ||

| Random Forest (RF) | Scikit-learn RandomForestClassifier |

Robust bagging ensemble for classification and feature importance analysis [15] [9]. |

| LightGBM (LGBM) | LightGBM Framework | High-performance gradient boosting framework, effective with resampled data [10]. |

| Voting / Stacking Classifier | Scikit-learn VotingClassifier, StackingClassifier |

Combines predictions from multiple heterogeneous base estimators [12] [13]. |

| Model Interpretation | ||

| SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) | SHAP Library | Explains the output of any ML model, critical for clinical trust [15]. |

In the demanding field of cancer research, where diagnostic accuracy directly impacts patient outcomes, the transition from relying on single predictive models to harnessing the power of ensemble methods represents a significant paradigm shift. Ensemble learning, a subfield of machine learning, employs multiple learning algorithms to obtain better predictive performance than could be obtained from any of the constituent learning algorithms alone [16]. In the context of cancer classification—a task complicated by high-dimensional data, class imbalance, and the inherent biological complexity of the disease—this "collective intelligence" offers a robust framework for improving diagnostic precision. By strategically combining the predictions from diverse models, ensemble techniques effectively mitigate the individual weaknesses of single models, leading to enhanced stability and accuracy in classification tasks [16] [17]. This article explores the theoretical underpinnings of ensemble learning and provides detailed protocols for their application in cancer classification research, spanning multiomics data integration and medical image analysis.

Theoretical Foundations of Ensemble Learning

The theoretical justification for ensemble learning is deeply rooted in its ability to optimize the bias-variance trade-off, a fundamental concept in supervised learning. A single model, especially a complex one, might have low bias but high variance, meaning it is sensitive to small fluctuations in the training data and prone to overfitting. Conversely, an overly simplistic model may have high bias and fail to capture important patterns in the data [17].

- Bias-Variance Decomposition: The expected prediction error of a model can be decomposed into three components: bias, variance, and irreducible error. Ensemble methods aim to reduce variance, bias, or both, depending on the technique [17].

- The Power of Diversity: The efficacy of an ensemble hinges on the diversity of its base models. If all models make the same errors, combining them will not yield improvements. Empirically, ensembles tend to yield better results when there is a significant diversity among the models they combine [16]. This diversity can be achieved by using different algorithms, different training data subsets, or different model configurations.

The most common ensemble strategies are bagging, boosting, and stacking, each with distinct theoretical mechanisms for improving prediction.

Bagging (Bootstrap Aggregating)

Bagging reduces variance by averaging the predictions of multiple models trained on different bootstrapped datasets (random samples drawn from the training set with replacement) [16] [18].

- Theoretical Mechanism: The variance of the combined model is reduced compared to the variance of a single base model. Assuming the prediction errors of the M base models are uncorrelated, the variance can be reduced by a factor of M while the bias remains similar to that of the individual models [17].

- Common Application: The Random Forest algorithm is an extension of bagging for decision trees, which introduces an additional layer of diversity by randomizing the features considered for splits at each node [16].

Boosting

Boosting follows an iterative, sequential process to reduce both bias and variance. New models are trained to focus on the errors or misclassified instances of the previous models, and their predictions are combined through a weighted majority vote [16] [17].

- Theoretical Mechanism: Boosting builds an additive model in a greedy manner. In each step, the algorithm tries to correct the residual errors from the previous model. This sequential refinement leads to a progressive reduction in bias. Variants like AdaBoost have been rigorously shown to reduce the overall prediction error exponentially across iterations [17].

- Common Applications: Algorithms like AdaBoost, Gradient Boosting, and Categorical Boosting (CatBoost) are widely used. For instance, CatBoost achieved a test accuracy of 98.75% in predicting cancer risk from lifestyle and genetic data, outperforming other traditional and ensemble models [19].

Stacking (Stacked Generalization)

Stacking, or blending, is a more flexible ensemble technique that involves training a meta-learner to optimally combine the predictions of several diverse base models [16] [18].

- Theoretical Mechanism: Instead of simple averaging or voting, stacking uses a second-level model to learn how to best integrate the predictions from the first-level models. Since the prediction function of the meta-learner can be non-linear, it can potentially reduce both the bias and variance terms in the error decomposition [17].

- Implementation: The process involves creating a new dataset where the inputs are the out-of-sample predictions (e.g., from cross-validation) of the base models, and the output is the true target value. A meta-model is then trained on this new dataset to form the final predictor [18].

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships and workflow between these core ensemble learning concepts.

Application in Cancer Classification: Protocols and Performance

Ensemble methods have demonstrated remarkable success across various cancer classification domains, from integrating multiomics data to analyzing medical images. The following table summarizes quantitative performance data from recent studies, highlighting the effectiveness of ensemble approaches.

Table 1: Performance of Ensemble Methods in Recent Cancer Classification Studies

| Cancer Type / Focus | Data Modality | Ensemble Method | Base Models | Key Performance Metric |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-Cancer Type Classification [13] [1] | Multiomics (RNA-seq, Somatic Mutation, DNA Methylation) | Stacking Ensemble | SVM, KNN, ANN, CNN, Random Forest | 98% Accuracy with multiomics data vs. 96% (RNA-seq alone) |

| Lung Cancer Classification [2] | CT Scan Images | Voting Ensemble | SVM, KNN, RF, GNB, GBM | 99.49% Accuracy, 100% Precision, 99% Recall |

| Cervical Cancer Classification [20] | Pap Smear Images | Ensemble (CNN, AlexNet, SqueezeNet) | CNN, AlexNet, SqueezeNet | 94% Accuracy (surpassing individual model accuracies of 90.8-92%) |

| General Cancer Risk Prediction [19] | Lifestyle & Genetic Data | Boosting (CatBoost) | N/A (Single ensemble model) | 98.75% Test Accuracy, F1-score: 0.9820 |

Protocol 1: Stacking Ensemble for Multiomics Cancer Classification

This protocol details the methodology for developing a stacking ensemble to classify five common cancer types (e.g., breast, colorectal, thyroid) using RNA sequencing, somatic mutation, and DNA methylation data [13] [1].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Computational Tools for Multiomics Analysis

| Item / Resource | Function / Description | Source / Example |

|---|---|---|

| The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) | Source for RNA sequencing data; provides ~20,000 primary cancer and matched normal samples. | National Cancer Institute |

| LinkedOmics Database | Source for somatic mutation and DNA methylation profiles corresponding to TCGA samples. | LinkedOmics Portal |

| Python 3.10+ | Primary programming language for implementing the data preprocessing and ensemble model. | Python Software Foundation |

| Aziz Supercomputer (or equivalent HPC) | High-performance computing resource for handling computationally intensive omics data processing. | King Abdulaziz University |

| scikit-learn, TensorFlow/PyTorch | Machine learning and deep learning libraries for building base models and meta-learner. | Open Source Libraries |

Step-by-Step Workflow

Data Acquisition and Cleaning:

- Download RNA sequencing data from TCGA and corresponding somatic mutation and methylation data from LinkedOmics for the target cancer types (e.g., BRCA, COAD, THCA) [13] [1].

- Perform data cleaning to ensure integrity: identify and remove cases with missing or duplicate values (approximately 7% of cases were removed in the original study) [13].

Data Preprocessing and Feature Extraction:

- Normalization: For RNA sequencing data, apply the Transcripts Per Million (TPM) method to eliminate technical variation using the formula provided in the original study to normalize gene expression counts [13] [1].

- Feature Extraction: To handle the high dimensionality of the RNA-seq data, employ an autoencoder to compress the input features into a lower-dimensional space, preserving essential biological properties [13].

Training Base Models:

- Split the preprocessed multiomics data into training and testing sets (e.g, 80%/20%).

- Individually train the following five base models on the training set. It is crucial to use cross-validation to generate out-of-sample predictions for the next step.

- Support Vector Machine (SVM)

- k-Nearest Neighbors (KNN)

- Artificial Neural Network (ANN)

- Convolutional Neural Network (CNN)

- Random Forest (RF)

Building the Stacking Ensemble:

- Create a new dataset (the "level-1" dataset) where each instance consists of the predicted class probabilities (or labels) from the five base models as features, and the true label as the target.

- Train a meta-learner on this new dataset. A common and effective choice is a regularized linear model, such as a linear regression with lasso penalty, which can help prune non-informative base models [18].

- The final stacked model makes predictions by first getting predictions from all base models and then feeding them into the trained meta-learner for the final classification.

The workflow for this protocol, from data preparation to final prediction, is visualized below.

Protocol 2: CNN-SVD Ensemble for Lung Cancer Classification from CT Scans

This protocol outlines a hybrid feature extraction and ensemble method for multiclass lung cancer classification, achieving state-of-the-art performance [2].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Tools for Image-Based Cancer Classification

| Item / Resource | Function / Description | Source / Example |

|---|---|---|

| Lung CT Scan Dataset | Publicly available dataset of chest CT scan images for lung cancer, annotated for binary and multiclass classification. | Public repositories (e.g., Kaggle, The Cancer Imaging Archive) |

| Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) | Used as a primary feature extractor from the medical images. | TensorFlow/PyTorch |

| Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) | A matrix factorization technique used for dimensionality reduction of the extracted CNN features. | scikit-learn, SciPy |

| Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM) | An explainable AI (XAI) technique to visualize regions of the image most influential to the prediction. | Various XAI Libraries |

Step-by-Step Workflow

Image Preprocessing:

- Apply Contrast-Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalization (CLAHE) to enhance the contrast of the CT scan images, generating images with minimal noise and prominent distinctive features [2].

- Resize all images to a uniform dimensions suitable for the CNN input.

Hybrid Feature Extraction with CNN-SVD:

- Use a pre-trained CNN (e.g., on ImageNet) without its final classification layer as a feature extractor. Process all CT images through this network to obtain a high-dimensional feature vector for each image.

- Apply Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) to the matrix of all feature vectors. SVD decomposes the matrix and allows for dimensionality reduction by selecting the top k singular values and their corresponding vectors, capturing the most important patterns while reducing noise and computational load [2].

Training the Voting Ensemble:

- The reduced feature set from the CNN-SVD step serves as the input for the following machine learning classifiers:

- Support Vector Machine (SVM)

- k-Nearest Neighbors (KNN)

- Random Forest (RF)

- Gaussian Naive Bayes (GNB)

- Gradient Boosting Machine (GBM)

- Train each of these models independently on the training set.

- Implement a voting ensemble for the final prediction. This can be a "hard" vote (final class is the mode of all predictions) or a "soft" vote (final class is derived from the average of predicted probabilities) [2].

- The reduced feature set from the CNN-SVD step serves as the input for the following machine learning classifiers:

Model Interpretation with Explainable AI (XAI):

- Integrate Grad-CAM with the CNN model to produce heatmaps that highlight the regions in the CT scans that were most influential for the classification decision. This step is critical for building trust and providing clinical interpretability [2].

The theoretical framework of ensemble learning—centered on the principles of variance reduction, bias correction, and leveraging model diversity—provides a powerful foundation for tackling the complex challenges inherent in cancer classification. The protocols detailed herein, from stacking for multiomics data to hybrid CNN ensembles for medical imaging, offer researchers and drug development professionals reproducible methodologies to achieve state-of-the-art performance. As the field advances, future research should focus on refining these ensemble methodologies, expanding their applicability to other cancer types and data modalities, and further integrating explainable AI to ensure these powerful tools are both effective and transparent for clinical translation.

Building Powerful Ensemble Classifiers: From Stacking to Multiomics Integration

Ensemble learning represents a paradigm in machine learning where multiple models, often called "base learners" or "weak learners," are strategically combined to solve a particular computational intelligence problem. The core principle is that a group of weak models can collectively form a stronger, more robust model, a concept inspired by the "wisdom of the crowd" [21]. In cancer classification research, where high-dimensional multiomics data and complex medical images present significant analytical challenges, ensemble methods have proven particularly valuable for improving diagnostic accuracy, prognostic prediction, and treatment stratification [1] [2]. These techniques help mitigate common data issues in biomedical research, including class imbalance, overfitting on limited patient data, and the "curse of dimensionality" inherent to genomics and medical imaging data [1].

This article details the three core ensemble architectures—bagging, boosting, and stacking—within the context of cancer informatics. We provide structured comparisons, detailed experimental protocols, and implementation guidance specifically tailored for research scientists and drug development professionals working on computational oncology problems.

Bagging (Bootstrap Aggregating)

Conceptual Foundation

Bagging, an acronym for Bootstrap Aggregating, is an ensemble technique designed primarily to reduce variance and prevent overfitting in high-variance models [22]. The method operates by creating multiple versions of the original training dataset through bootstrap sampling (random sampling with replacement) and training a base model on each of these versions [21]. The final prediction is generated by aggregating the predictions of all individual models, typically through majority voting for classification problems or averaging for regression problems [23].

The theoretical foundation of bagging rests on the statistical method of bootstrapping, which enables robust estimation of model statistics. As demonstrated through Condorcet's Jury Theorem, the collective decision of multiple independent judges can yield more accurate results than any single judge, provided each judge has at least a modest level of competence [21]. Similarly, in bagging, the combined prediction from multiple models typically outperforms individual models, especially when the base learners are unstable (e.g., decision trees) [21].

Implementation Protocol

A standardized protocol for implementing bagging in a cancer classification context involves the following steps:

- Bootstrap Sampling: Given a training dataset ( D ) of size ( N ), generate ( M ) new bootstrap samples ( D1, D2, ..., D_M ), each of size ( N ), by randomly drawing instances from ( D ) with replacement. Each sample typically contains approximately 63.2% of the original training instances, with some duplicates.

- Base Model Training: Train ( M ) instances of a base classifier (e.g., Decision Tree, Random Forest) independently on each bootstrap sample ( D_i ). For cancer classification using histopathology images or genomic data, the base model architecture should be selected based on data modality (e.g., CNNs for images, ANNs for omics data).

- Prediction Aggregation: For a new test sample ( x ), obtain predictions ( a1(x), a2(x), ..., aM(x) ) from all trained models. The final ensemble prediction ( a(x) ) is determined by majority voting: ( a(x) = \text{mode}{a1(x), a2(x), ..., aM(x)} ).

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Bagging Ensemble in Cancer Classification

| Cancer Type | Data Modality | Base Model | Performance (Accuracy) | Key Benefit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lung Cancer [2] | CT Scans | Multiple ML classifiers | 99.49% | Superior accuracy in multiclass classification |

| Not Specified [22] | Generic | Decision Trees | Improved over base | Reduces variance and overfitting |

Workflow Visualization

Bagging Ensemble Architecture

Boosting

Conceptual Foundation

Boosting is a sequential ensemble technique that converts multiple weak learners into a single strong learner. Unlike bagging where models are built independently, boosting constructs models sequentially, with each new model focusing on the errors made by previous models [24] [22]. The core principle is to adaptively adjust the weights of training instances, giving higher weight to misclassified samples in subsequent iterations, thereby forcing the model to concentrate on harder-to-classify cases.

This approach is particularly effective for reducing both bias and variance, making it suitable for weak learners that perform only slightly better than random guessing [22]. In cancer classification, boosting algorithms excel at identifying subtle patterns in complex datasets, which can be critical for distinguishing between cancer subtypes with similar morphological or molecular characteristics [24].

Implementation Protocol

A generalized protocol for implementing boosting in a cancer classification context:

- Initialize Weights: Assign equal weight ( wi = 1/N ) to each training instance ( (xi, y_i) ) in dataset ( D ) of size ( N ).

- Sequential Model Training: For ( T ) iterations: a. Train a weak learner ( ht ) (e.g., a shallow decision tree) on the weighted training data. b. Calculate the weighted error ( \epsilont ) of ( ht ). c. Compute the model weight ( \alphat = \frac{1}{2} \ln \left( \frac{1 - \epsilont}{\epsilont} \right) ), which represents the contribution of ( h_t ) to the final prediction. d. Update the instance weights: increase weights for misclassified instances and decrease weights for correctly classified instances. e. Normalize the weights to form a probability distribution.

- Final Ensemble Formation: Combine all weak learners using weighted majority voting: ( H(x) = \text{sign}\left( \sum{t=1}^T \alphat h_t(x) \right) ).

Table 2: Popular Boosting Algorithms and Their Applications

| Algorithm | Key Mechanism | Cancer Research Application | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gradient Boosting (GBM) [24] | Fits new models to residuals of previous models | Histopathological image classification | High predictive accuracy |

| XGBoost [24] | Regularized model with presorted splitting | Genomic biomarker discovery | Computational efficiency, handling missing data |

| LightGBM [24] | Gradient-based One-Sided Sampling (GOSS) | Large-scale medical image analysis | Fast training speed, low memory usage |

| CatBoost [24] | Handles categorical features natively | Integration of clinical and genomic data | No preprocessing for categorical variables |

Workflow Visualization

Boosting Sequential Training Process

Stacking (Stacked Generalization)

Conceptual Foundation

Stacking, also known as stacked generalization, is an advanced ensemble technique that combines multiple heterogeneous base models (e.g., SVM, Random Forest, KNN) using a meta-learner [23] [25]. The fundamental concept is to learn the optimal way to combine the predictions of diverse base models, rather than relying on simple voting or averaging [26].

The stacking architecture typically consists of two or more levels: level-0 contains the base models that are trained on the original data, and level-1 contains a meta-model that is trained on the outputs (predictions) of the base models [23] [25]. This approach leverages the diverse inductive biases of different algorithms, allowing the ensemble to capture complementary patterns in the data that might be missed by any single algorithm.

In multiomics cancer classification, stacking has demonstrated exceptional performance by effectively integrating predictions from models trained on different data modalities (e.g., RNA sequencing, DNA methylation, somatic mutations) [1]. A recent study achieved 98% accuracy in classifying five common cancer types using a stacking ensemble that integrated multiomics data, outperforming models using single-omics data [1].

Implementation Protocol

A detailed protocol for implementing stacking in cancer classification:

Data Preparation and Base Model Selection: a. Split the dataset into training (( D{\text{train}} )) and testing (( D{\text{test}} )) sets. b. Select ( K ) diverse base models (e.g., SVM, Random Forest, KNN, Neural Networks) [25]. Diversity in model types is crucial for effective stacking.

Cross-Validation for Meta-Feature Generation: a. Split ( D{\text{train}} ) into ( V )-folds (typically 5-10) [26]. b. For each base model ( mk ): - For fold ( v = 1 ) to ( V ): * Train ( mk ) on ( V-1 ) folds. * Generate predictions on the validation fold ( v ). - Collect all out-of-fold predictions to form a new feature vector for the meta-model. c. Apply each trained base model to ( D{\text{test}} ) to generate test meta-features.

Meta-Model Training and Prediction: a. Train the meta-model (e.g., Logistic Regression, Random Forest, XGBoost) on the meta-features generated from ( D_{\text{train}} ) [25]. b. Use the trained meta-model to make final predictions on the test meta-features.

Table 3: Stacking Ensemble Performance in Multiomics Cancer Classification

| Study | Cancer Types | Base Models | Meta-Model | Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multiomics Study [1] | Breast, Colorectal, Thyroid, NHL, Corpus Uteri | SVM, KNN, ANN, CNN, RF | Not Specified | 98% Accuracy with multiomics data |

| Iris Classification [25] | Iris Flower Species | Decision Tree, SVM, RF, KNN, Naive Bayes | Logistic Regression | Superior to individual base models |

Workflow Visualization

Stacking Ensemble Architecture

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents and Computational Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Ensemble-Based Cancer Classification

| Item | Function/Purpose | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) [1] | Provides comprehensive multiomics cancer datasets | Training and validation data source for ensemble models |

| RNA Sequencing Data [1] | Captures gene expression profiles for transcriptome analysis | Input for base models in multiomics integration |

| DNA Methylation Data [1] | Provides epigenetic regulation patterns | Complementary data modality for improved classification |

| Somatic Mutation Data [1] | Identifies genomic alterations driving carcinogenesis | Feature input for mutation-aware classification models |

| CT Scan Images [2] | Provides structural information for tumor identification | Input for CNN-based feature extraction in ensemble |

| Python Scikit-learn [25] | Implements standard ensemble algorithms and utilities | Protocol implementation for bagging, boosting, stacking |

| Autoencoders [1] | Reduces dimensionality of high-throughput omics data | Feature extraction preprocessing for high-dimensional data |

| Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM) [2] | Provides model interpretability by highlighting salient regions | Explainable AI for clinical validation of ensemble predictions |

Comparative Analysis and Decision Framework

Table 5: Comparative Analysis of Core Ensemble Architectures

| Aspect | Bagging | Boosting | Stacking |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Objective | Variance reduction, overfitting prevention [22] | Bias and variance reduction, error correction [22] | Optimal combination of diverse models [23] |

| Training Process | Parallel, independent [22] | Sequential, adaptive [24] [22] | Hierarchical with base and meta-learners [23] |

| Base Model Diversity | Homogeneous (same algorithm) | Homogeneous (same algorithm) | Heterogeneous (different algorithms) [25] |

| Overfitting Risk | Low [22] | High, if not properly regularized [22] | Moderate, requires careful validation [26] |

| Computational Demand | Moderate (parallelizable) [22] | High (sequential) [22] | High (multiple algorithms with cross-validation) [26] |

| Ideal Use Case in Cancer Research | High-variance models (deep trees) on large datasets [22] | Weak learners, imbalanced datasets, high accuracy needs [22] | Multiomics data integration, leveraging complementary models [1] |

| Representative Algorithms | Random Forest, Bagged Decision Trees [22] | AdaBoost, XGBoost, LightGBM [24] [22] | Custom stacks with diverse base classifiers and meta-learners [25] |

Decision Framework for Cancer Classification

Based on the comparative analysis, the following decision framework can guide researchers in selecting appropriate ensemble methods:

Select Bagging When: Working with high-variance models like deep decision trees; addressing overfitting in complex models; processing large-scale genomic or image datasets; when computational efficiency through parallelization is important [22].

Select Boosting When: Maximizing classification accuracy is critical; working with weaker base learners; dealing with imbalanced cancer datasets; the dataset is relatively clean of noise; and longer training times are acceptable [24] [22].

Select Stacking When: Integrating diverse data modalities (multiomics); combining predictions from fundamentally different model architectures; the predictive task is complex enough to benefit from model complementarity; and sufficient computational resources are available for rigorous cross-validation [1] [26].

For many cancer classification problems, a practical approach is to experiment with multiple ensemble strategies and compare their performance through rigorous cross-validation, as the optimal technique often depends on the specific characteristics of the dataset and the clinical question being addressed.

Advanced Stacking Ensembles for Multi-Cancer and Multiomics Data Classification

Advanced stacking ensemble methods represent a transformative approach in computational oncology, enabling robust cancer classification by integrating diverse multiomics data types. These techniques synergistically combine multiple machine learning models through a meta-learner framework to achieve superior predictive performance compared to individual classifiers. This protocol details the implementation of stacking ensembles for classifying five common cancer types—breast (BRCA), colorectal (COAD), thyroid (THCA), non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), and corpus uteri (UCEC)—using RNA sequencing, somatic mutation, and DNA methylation data. The documented methodology achieved 98% classification accuracy in validation studies, significantly outperforming single-modality approaches and establishing a new benchmark for multiomics cancer classification. We provide comprehensive application notes covering experimental design, computational workflows, and performance validation metrics to facilitate adoption within research and clinical settings.

Cancer classification has evolved from histopathological examination to molecular subtyping based on genomic, transcriptomic, and epigenomic alterations. The complexity and heterogeneity of cancer necessitate sophisticated computational approaches that can integrate diverse molecular data types—collectively termed multiomics—to achieve accurate classification [1]. Stacking ensemble learning has emerged as a particularly powerful framework for this challenge, combining the predictions of multiple base classifiers through a meta-learner to improve overall accuracy, robustness, and generalizability [27] [28].

The fundamental advantage of stacking ensembles lies in their ability to leverage the complementary strengths of diverse machine learning algorithms. While individual models may excel at capturing specific patterns in complex datasets, their performance can be limited by inherent algorithmic biases and assumptions. Stacking overcomes these limitations by training a meta-learner to optimally combine the predictions of multiple base models, effectively creating a more powerful composite classifier [29] [30]. This approach is particularly well-suited to multiomics data integration, where different data types (e.g., RNA sequencing, somatic mutations, DNA methylation) exhibit distinct statistical properties and biological significance.

Within oncology, stacking ensembles have demonstrated remarkable performance across diverse applications including cancer type classification [1], prognostic prediction [27], and drug response forecasting [31]. This protocol focuses specifically on their application for multi-cancer classification using multiomics data, providing researchers with a comprehensive framework for implementation and validation.

Background & Significance

Multiomics Data in Cancer Classification

Multiomics approaches provide a comprehensive view of molecular alterations in cancer by simultaneously analyzing multiple data types:

- RNA sequencing quantifies gene expression levels across the transcriptome, revealing which genes are actively expressed in cancer cells and providing functional insights into cancer phenotypes [1].

- Somatic mutation data captures DNA sequence alterations specific to cancer cells, with binary representation (0 or 1) indicating the presence or absence of mutations in specific genes [1].

- DNA methylation profiles epigenetic modifications involving the addition of methyl groups to DNA, typically represented as continuous values ranging from -1 to 1, which regulate gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence [1].

The integration of these complementary data types enables a more comprehensive understanding of cancer biology than any single data type alone. However, this integration presents substantial computational challenges due to the high dimensionality, heterogeneous scales, and different statistical properties of multiomics datasets [1].

Ensemble Learning Fundamentals

Ensemble learning methods operate on the principle that combining multiple models can produce better performance than any constituent model alone. Stacking (stacked generalization) represents an advanced ensemble approach wherein multiple base models (level-0 models) are trained on the same dataset, and their predictions are then combined using a meta-learner (level-1 model) [28] [30]. This architecture allows the meta-learner to learn which base models perform best for specific types of input patterns or in particular regions of the feature space.

The theoretical foundation for stacking ensembles derives from the concept of "wisdom of the crowd," where the collective decision of diverse experts typically outperforms individual experts. In computational terms, this diversity is achieved by incorporating models with different inductive biases (e.g., tree-based models, kernel methods, neural networks) that capture complementary patterns in the data [29].

Experimental Design & Protocols

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

- Obtain RNA sequencing data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), which comprises approximately 20,000 primary cancer and matched normal samples across 33 cancer types [1].

- Acquire somatic mutation and methylation data from the LinkedOmics database, containing multiomics data from all 32 TCGA cancer types and 10 Clinical Proteomic Tumor Analysis Consortium (CPTAC) cohorts [1].

- Focus on five cancer types prevalent in the study population: breast invasive carcinoma (BRCA), colon adenocarcinoma (COAD), thyroid carcinoma (THCA), non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), and uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma (UCEC).

Data Cleaning

- Identify and remove cases with missing or duplicate values (approximately 7% of cases in reference study) [1].

- Ensure sample matching across omics modalities to maintain consistent patient representation.

Table 1: Dataset Composition After Preprocessing

| Cancer Type | Abbreviation | RNA Sequencing | Somatic Mutation | Methylation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast | BRCA | 1,223 | 976 | 784 |

| Colorectal | COAD | 521 | 490 | 394 |

| Thyroid | THCA | 568 | 496 | 504 |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | NHL | 481 | 240 | 288 |

| Corpus uteri | UCEC | 587 | 249 | 432 |

Normalization Protocol

RNA sequencing data: Apply transcripts per million (TPM) normalization using the formula:

[ TPM = \frac{10^6 \times (\text{reads mapped to transcript} / \text{transcript length})}{\sum(\text{reads mapped to transcript} / \text{transcript length})} ]

This method eliminates systematic experimental bias and technical variation while maintaining biological diversity [1].

- Methylation data: Retain original beta values ranging from -1 to 1, as these already represent standardized methylation measurements.

- Somatic mutation data: Maintain binary representation (0/1) indicating absence/presence of mutations.

Feature Extraction

- Address high dimensionality of RNA sequencing data using autoencoder technique [1].

- Implement autoencoder with architecture comprising encoder (compresses input features), code (bottleneck layer), and decoder (reconstructs input from compressed representation).

- Train autoencoder to minimize reconstruction error, ensuring compressed representation retains biologically relevant information.

Base Model Selection and Training

Recommended Base Models

Incorporate five well-established machine learning models as base learners to ensure diversity in algorithmic approaches:

- Support Vector Machine (SVM): Effective for high-dimensional data, identifies complex decision boundaries [1] [30].

- k-Nearest Neighbors (KNN): Instance-based learning suitable for capturing local patterns in feature space [1].

- Artificial Neural Network (ANN): Captures nonlinear relationships through layered architecture [1].

- Convolutional Neural Network (CNN): Specialized for spatial pattern recognition, adaptable to omics data [1] [28].

- Random Forest (RF): Ensemble of decision trees, robust to noise and irrelevant features [1] [30].

Training Protocol

- Split data into training (70%), validation (15%), and test (15%) sets using stratified sampling to maintain class distribution.

- Implement k-fold cross-validation (k=5) for model training and hyperparameter optimization.

- Address class imbalance using Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE) or class weighting [1].

- Apply regularization techniques (L1/L2 regularization, dropout for neural networks) to mitigate overfitting.

Stacking Ensemble Implementation

Meta-Learner Selection

- Train meta-learner on predictions from base models using cross-validated approach to prevent data leakage.

- Consider logistic regression, neural networks, or gradient boosting machines as meta-learners [28] [29].

- For advanced implementations, Transformer-based meta-learners can dynamically weight base model contributions through self-attention mechanisms [29].

Implementation Workflow

- Train all base models on the training dataset using k-fold cross-validation.

- Generate cross-validated predictions from each base model for the training set.

- Create new dataset where features represent prediction probabilities from each base model.

- Train meta-learner on this new dataset to combine base model predictions optimally.

- Finalize model by retraining base models on entire training set with optimized hyperparameters.

The following diagram illustrates the complete stacking ensemble workflow for multiomics cancer classification:

Model Validation and Interpretation

Performance Metrics

- Calculate accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score for each cancer type.

- Generate multiclass receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and compute area under curve (AUC) values.

- For survival prediction tasks, use concordance index (C-index) to evaluate prognostic performance [27].

Validation Strategies

- Implement internal validation through k-fold cross-validation (k=5 or 10).

- Perform external validation on completely independent datasets when available.

- Conduct statistical significance testing (e.g., DeLong's test for AUC comparisons) to confirm performance improvements.

Model Interpretation

- Apply SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) to quantify feature importance across the ensemble [29].

- Analyze base model contributions to identify specialized capabilities for specific cancer types or data modalities.

- Visualize decision boundaries using dimensionality reduction techniques (t-SNE, UMAP).

Performance Benchmarking

Comparative Performance Analysis

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Classification Approaches

| Model Type | Data Modality | Accuracy | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stacking Ensemble | Multiomics (RNA-seq + Mutation + Methylation) | 98% | Highest performance integrating all data types [1] |

| Individual Model | RNA-seq only | 96% | Strong but inferior to multiintegration |

| Individual Model | Methylation only | 96% | Comparable to RNA-seq alone |

| Individual Model | Somatic mutation only | 81% | Lower performance due to data sparsity |

| Radiomics Stacking | PET + CT images | C-index: 0.9345 | Application in prognostic prediction [27] |

| Transformer Stacking | Gene expression | 99.7% | Advanced architecture for complex patterns [29] |

Ablation Studies

- Evaluate contribution of individual base models by systematically excluding each from the ensemble.

- Assess performance impact of different meta-learners on overall classification accuracy.

- Quantify value of each omics data type by training ensembles with different data combinations.

Research Reagent Solutions

Computational Tools and Platforms

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Resource | Type | Function | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Python 3.10+ | Programming Language | Primary implementation platform | Essential libraries: scikit-learn, TensorFlow/PyTorch, PyRadiomics |

| TCGA Database | Data Resource | Source for RNA sequencing data | ~20,000 primary cancer samples across 33 cancer types |

| LinkedOmics | Data Resource | Source for somatic mutation and methylation data | 32 TCGA cancer types + 10 CPTAC cohorts |

| Autoencoders | Feature Extraction | Dimensionality reduction for high-dimensional omics data | Preserves biological properties while reducing dimensionality |

| SHAP | Interpretation | Model explainability and feature importance | Critical for understanding ensemble decisions |

| PyRadiomics | Feature Extraction | Standardized radiomic feature extraction | Follows Image Biomarker Standardization Initiative guidelines |

Advanced Applications and Modifications

Transformer-Based Meta-Learners

For complex classification tasks with subtle patterns, consider replacing traditional meta-learners with Transformer-based architectures:

- Implement self-attention mechanisms to dynamically weight base model contributions based on input patterns [29].

- Train Transformer meta-learners on prediction probabilities from base models alongside original feature representations.

- Leverage multi-head attention to capture different aspects of base model relationships.

Multiomics Data Fusion Strategies

- Early fusion: Concatenate features from different omics modalities before model training.

- Intermediate fusion: Process each data type with specialized base models, then integrate representations before final layers.

- Late fusion: Train separate models on each data type and combine predictions at the meta-learner level.

Cross-Domain Adaptation

The stacking ensemble framework can be adapted to various cancer classification scenarios:

- Radiomics integration: Incorporate radiomic features from medical images alongside molecular data [27].

- Drug response prediction: Modify output layer to predict therapeutic sensitivity instead of cancer type [31].

- Multi-cancer screening: Extend classification to include additional cancer types with sufficient samples.

Troubleshooting and Optimization

Common Implementation Challenges

- Class imbalance: Address through synthetic oversampling (SMOTE), class weighting, or stratified sampling.

- Overfitting: Implement regularization (L1/L2, dropout), early stopping, and simplify model architecture.

- Computational complexity: Utilize high-performance computing resources, mini-batch processing, and feature selection.

- Data heterogeneity: Apply batch correction methods and domain adaptation techniques for multi-center studies.

Performance Optimization Guidelines

- Conduct systematic hyperparameter optimization for both base models and meta-learners.

- Ensure diversity in base model selection to capture complementary patterns.

- Implement feature selection tailored to each data type before ensemble integration.

- Validate on external datasets to confirm generalizability across populations and platforms.

Advanced stacking ensembles represent a powerful framework for multi-cancer classification using multiomics data, consistently demonstrating superior performance compared to individual modeling approaches. The methodology outlined in this protocol provides researchers with a comprehensive toolkit for implementing these ensembles, from data preprocessing through model interpretation. As computational oncology continues to evolve, stacking ensembles offer a flexible and robust approach for integrating increasingly diverse and complex datasets, ultimately contributing to more accurate cancer diagnosis and personalized treatment strategies.

The field continues to advance with innovations in meta-learner architectures (particularly Transformer-based approaches), expanded multiomics integration, and improved model interpretability. These developments promise to further enhance the clinical utility of ensemble methods in cancer classification and beyond.

Implementing Ensemble Models on Gene Expression and Exome Datasets for Early Diagnosis