Enrichment Factor Analysis: The Essential Guide to Validating Pharmacophore Models in Drug Discovery

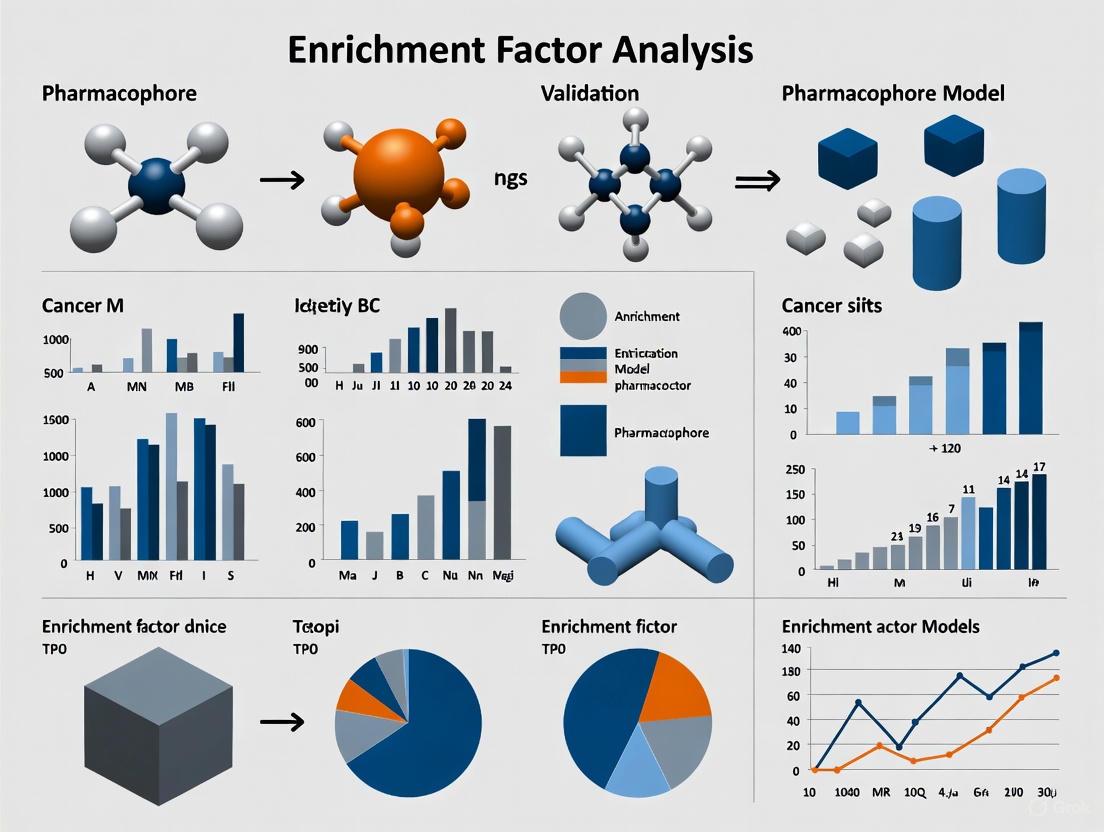

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Enrichment Factor (EF) analysis, a critical metric for evaluating the performance and predictive power of pharmacophore models in virtual screening.

Enrichment Factor Analysis: The Essential Guide to Validating Pharmacophore Models in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Enrichment Factor (EF) analysis, a critical metric for evaluating the performance and predictive power of pharmacophore models in virtual screening. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles of EF, its calculation, and interpretation within the broader context of model validation. Readers will find detailed methodological workflows for applying EF analysis, strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing underperforming models, and a comparative framework for integrating EF with other validation techniques like ROC curves and goodness-of-hit scores. The content synthesizes current best practices to empower scientists in building robust, reliable pharmacophore models that effectively prioritize active compounds in large chemical libraries.

What is Enrichment Factor Analysis? Defining the Key Metric for Pharmacophore Validation

Defining Enrichment Factor (EF) and its Critical Role in Virtual Screening

In the field of computer-aided drug discovery, virtual screening is a fundamental computational approach used to rapidly evaluate large libraries of chemical compounds to identify promising candidates for experimental testing [1]. The success of any virtual screening method, whether it is pharmacophore-based or docking-based, hinges on its ability to distinguish active compounds (true binders) from inactive ones effectively. To quantitatively measure this discriminatory power, researchers rely heavily on a metric known as the Enrichment Factor (EF) [2] [3].

The Enrichment Factor provides a straightforward, yet powerful, measure of how much better a virtual screening method performs compared to a random selection of compounds. It is particularly valued for its interpretability in the early stages of a screening campaign, where researchers are most interested in the quality of the top-ranked compounds [3]. A high EF indicates that the computational model successfully enriches the top of the ranked list with true actives, thereby increasing the hit rate and reducing the number of compounds that need to be experimentally screened. This review will dissect the definition, calculation, and critical role of EF, providing a comparative analysis of its application in validating pharmacophore models and other virtual screening methodologies.

Defining and Calculating the Enrichment Factor

The Standard Enrichment Factor Formula

The traditional Enrichment Factor is a ratio that compares the fraction of active compounds found in a selected top-ranked subset of the screening library to the fraction of active compounds one would expect to find through random selection. The standard formula is expressed as:

EFχ = (Number of actives found in top χ% of ranked list / Total number of actives in library) / (χ%)

In this formula, χ represents the selection fraction, or the early portion of the ranked database that is considered (e.g., 1%, 5%, or 10%) [3]. For example, an EF₁% of 30 means that the model found active compounds in the top 1% of the list at a rate 30 times greater than random chance. The maximum value EFχ can achieve is theoretically limited by the ratio of inactive to active compounds in the dataset, which in practice often caps its value, especially for benchmarks with high inactive-to-active ratios [3].

The Bayes Enrichment Factor (EFB): An Improved Metric

Recognizing the limitations of the standard EF formula, particularly its dependence on the active-to-inactive ratio in a benchmark set, recent research has proposed an improved formula known as the Bayes Enrichment Factor (EFB) [3]. This metric leverages Bayes' Theorem and is defined as:

EFχB = (Fraction of actives whose score is above a threshold Sχ) / (Fraction of random molecules whose score is above Sχ)

The EFB offers several key advantages. It eliminates the need for carefully curated "decoy" sets presumed to be inactive, instead requiring only a set of random compounds from the same chemical space as the actives. This avoids a potential source of error and makes creating benchmarks easier. Furthermore, the EFB does not have a hard maximum value tied to dataset composition, allowing it to better estimate performance in real-life screens of very large libraries where the inactive-to-active ratio is enormous [3]. To provide a single robust metric, researchers often report the EFmaxB, which is the maximum value of the EFB achieved over the measurable range [3].

Workflow for EF Calculation in a Virtual Screening Campaign

The process of calculating the Enrichment Factor is embedded within a broader virtual screening workflow. The following diagram illustrates the key steps from model preparation to performance evaluation.

Virtual Screening EF Workflow

EF as a Validation Tool for Pharmacophore Models

The Role of EF in Pharmacophore Model Selection and Validation

Pharmacophore modeling is a ligand-based or structure-based method that identifies the essential 3D arrangement of molecular features responsible for biological activity [1] [4]. Before a pharmacophore model is deployed in a prospective virtual screen, its performance must be rigorously validated—a process where the Enrichment Factor is a central metric.

For instance, in a study on COX-2 inhibitors, a validated pharmacophore model was assessed using a decoys set from DUD-E, which contained known active compounds and presumed inactives [2]. The model's sensitivity (true positive rate) and specificity (true negative rate) were calculated, and its overall ability to differentiate actives from inactives was summarized using a Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve and the Area Under the Curve (AUC) [2]. A high EF value in such a validation test confirms that the model can successfully prioritize active compounds, justifying its use for screening large, unknown databases.

Case Study: Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling for GPCRs

A compelling application is presented in a study on G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), a class of targets with high flexibility [4]. Researchers generated 5,000 random structure-based pharmacophore models for eight class A GPCRs. Each model was scored using the Enrichment Factor and the Goodness-of-Hit (GH) score by screening a database containing known active and decoy compounds. The results demonstrated that this method could produce pharmacophore models achieving the theoretical maximum EF value for all eight targets using resolved crystal structures and for seven of the eight using homology models [4]. This underscores EF's critical role not just in validation, but also in the automated selection of optimal pharmacophore models from a large pool of candidates, even for highly flexible targets.

Comparative Performance of Virtual Screening Methods

Pharmacophore-Based vs. Docking-Based Virtual Screening

The Enrichment Factor enables direct, quantitative comparisons between different virtual screening methodologies. A landmark benchmark study compared pharmacophore-based virtual screening (PBVS) using Catalyst with several docking-based virtual screening (DBVS) programs (DOCK, GOLD, Glide) across eight diverse protein targets [5].

Table 1: Comparison of Pharmacophore-Based vs. Docking-Based Virtual Screening

| Screening Method | Average Hit Rate at 2% | Average Hit Rate at 5% | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmacophore-Based (Catalyst) | Much Higher | Much Higher | Outperformed DBVS in 14 out of 16 test cases [5] |

| Docking-Based (DOCK, GOLD, Glide) | Lower | Lower | Performance varied by target and program |

The study concluded that PBVS "outperformed DBVS methods in retrieving actives from the databases in our tested targets," showing a significantly higher average hit rate at the critical early enrichment levels (2% and 5% of the database) [5]. This highlights the utility of pharmacophore models as powerful filters in the early stages of drug discovery.

Performance of State-of-the-Art Screening Tools

EF is also indispensable for benchmarking new and improved virtual screening platforms. A recent development, RosettaVS, incorporates receptor flexibility and a new scoring function, RosettaGenFF-VS [6]. When evaluated on the standard CASF-2016 benchmark, RosettaVS achieved a top 1% enrichment factor (EF₁%) of 16.72, significantly outperforming the second-best method which had an EF₁% of 11.9 [6]. Similarly, on the DUD-E dataset, its performance was competitive with other state-of-the-art tools [6]. These results, quantified by EF, demonstrate the progressive refinement of virtual screening methods and their increasing ability to identify true bioactive molecules efficiently.

Table 2: Enrichment Factor Performance of Various Virtual Screening Methods

| Virtual Screening Method | Benchmark Dataset | Reported EF₁% | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| RosettaVS (RosettaGenFF-VS) | CASF-2016 | 16.72 | Models receptor flexibility [6] |

| Other Physics-Based Methods (Unspecified) | CASF-2016 | 11.9 (2nd best) | Varies by method [6] |

| PharmaGist (Pharmacophore-Based) | DUD | Comparable to state-of-the-art | Efficient for large chemical spaces [1] |

Experimental Protocols for EF Assessment

Protocol 1: Validating a Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Model

This protocol is adapted from studies involving the validation of pharmacophore models for targets like COX-2 inhibitors [2].

- Curate a Test Dataset: Assemble a benchmark set containing a known number of active compounds (e.g., confirmed COX-2 inhibitors) and a larger number of decoy molecules. Decoys can be obtained from public repositories like the Directory of Useful Decoys: Enhanced (DUD-E) [2].

- Run the Virtual Screen: Use the pharmacophore model (e.g., created in LigandScout) as a query to screen the entire test dataset. The software will output a list of compounds ranked by their fit value or a similar scoring metric.

- Calculate the Enrichment Factor:

- Define the early recognition threshold (e.g., χ = 1% or 5%).

- From the top χ% of the ranked list, count the number of true active compounds found.

- Calculate EFχ using the standard formula.

- Calculate Supplementary Metrics: Compute additional validation metrics to provide a comprehensive view:

- Sensitivity (True Positive Rate): TPR = TP / A, where A is all actives in the database [2].

- Specificity (True Negative Rate): TNR = TN / D, where D is all inactives/decoys in the database [2].

- ROC Curve and AUC: Plot the TPR against the False Positive Rate (FPR) across all thresholds and calculate the Area Under this curve [2].

Protocol 2: Benchmarking a Docking Program or Scoring Function

This protocol is based on large-scale evaluations of docking functions, such as those performed on the DUD-E dataset [3] [6].

- Select a Benchmark: Use a widely recognized benchmark like DUD-E (40 targets, ~100,000 compounds) or CASF [6]. These sets provide pre-defined actives and decoys for multiple targets.

- Perform Docking and Scoring: For each target in the benchmark, dock every compound (actives and decoys) using the program(s) of interest. Collect the docking scores for all compounds.

- Rank and Analyze: Rank the entire compound set for a target from best (most favorable score) to worst.

- Compute EF and EFB:

- Calculate the standard EF at various χ values (e.g., EF₁% and EF₁₀%).

- To calculate the Bayes EF (EFB), determine the score threshold Sχ that corresponds to the top χ% of a set of random compounds. Then, compute the fraction of actives that score better than this threshold [3].

- Report the EFmaxB, the maximum EFB value observed, as an indicator of the best possible performance in a large-scale screen [3].

Table 3: Essential Resources for Virtual Screening and EF Validation

| Resource Name | Type | Function in EF Validation | Reference/Availability |

|---|---|---|---|

| DUD-E (Directory of Useful Decoys, Enhanced) | Benchmark Dataset | Provides known actives and matched decoys for 40+ targets to test screening accuracy [2] [3]. | Publicly Available |

| CASF Benchmark | Benchmark Dataset | Standardized set for evaluating scoring function power, including "screening power" via EF [6]. | Publicly Available |

| ZINC Database | Compound Library | A public repository of commercially available compounds for prospective virtual screening after model validation [2] [4]. | Publicly Available |

| LigandScout | Software | Used to create and validate 3D pharmacophore models from protein-ligand complexes or ligand sets [2]. | Commercial Software |

| PharmaGist | Software | A ligand-based pharmacophore detection tool for aligning multiple flexible ligands and virtual screening [1]. | Web Server / Download |

| ROC Curve Analysis | Analytical Method | Visualizes the trade-off between sensitivity and specificity across all score thresholds, complementing EF [2]. | Standard Method |

The Enrichment Factor remains a cornerstone metric for evaluating the performance of virtual screening methods. Its simplicity and direct interpretation, especially regarding early enrichment, make it invaluable for validating pharmacophore models and comparing docking algorithms. While the standard EF is widely used, new formulations like the Bayes Enrichment Factor (EFB) address its limitations and offer a more robust way to predict performance in real-world, ultra-large library screens. As the field advances with methods like AI-accelerated platforms and flexible structure-based pharmacophores, the EF will continue to be the critical benchmark for quantifying success and driving efficiency in computational drug discovery.

In the field of computer-aided drug design (CADD), virtual screening (VS) serves as a fundamental technique for identifying potential hit compounds from extensive chemical libraries. To evaluate and compare the performance of these virtual screening methodologies, researchers rely on robust benchmarking datasets and quantitative metrics. Among these metrics, the Enrichment Factor (EF) stands as a crucial measure of a method's ability to prioritize active compounds over inactive ones during the early stages of screening. The calculation and interpretation of EF are intrinsically linked to three core components: the set of known active compounds, the selection of decoy molecules, and the total size of the screening database. A comprehensive understanding of these components and their interplay is essential for researchers aiming to validate pharmacophore models, docking protocols, or any other virtual screening approach rigorously. This guide objectively examines these core components, supported by experimental data and established protocols from current literature, to provide a solid foundation for enrichment factor analysis in pharmacophore model validation research.

Core Component 1: Active Compounds

Definition and Role in EF Calculation

Active compounds, often referred to as "known actives" or simply "actives," are molecules that have been experimentally confirmed to exhibit a desired biological activity against a specific therapeutic target. In the context of EF calculation, these compounds serve as the positive control set that a virtual screening method should ideally identify and rank highly. The quality, quantity, and diversity of the active set directly influence the reliability and relevance of the calculated EF.

The activity of these compounds is typically quantified through biochemical assays and represented by measurements such as half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC₅₀), inhibition constant (Kᵢ), or dissociation constant (K𝑑). For instance, in a study targeting the Brd4 protein for neuroblastoma, researchers curated 36 active antagonists from literature and the ChEMBL database, all with experimentally determined IC₅₀ values [7] [8]. Similarly, a pharmacophore model for SARS-CoV-2 PLpro validation was tested against 23 known active compounds with IC₅₀ values ranging from 0.1 to 5.7 μM [9].

Selection Criteria and Best Practices

The selection of active compounds for benchmarking is not arbitrary; it follows specific criteria to ensure a meaningful validation:

- Experimental Validation: Activities should be confirmed through reliable, consistent experimental assays. For example, a 3D-QSAR pharmacophore model for Akt2 inhibitors was built using a training set of 23 compounds whose IC₅₀ values were all measured using the same method [10].

- Structural Diversity: Whenever possible, the active set should encompass multiple chemical scaffolds to avoid bias toward a specific chemotype. Research on Akt2 inhibitors explicitly aimed to find novel scaffolds through virtual screening [10].

- Size of the Active Set: The number of known actives can vary significantly. Studies have used active sets ranging from just 3 actives for D-alanyl-D-alanine carboxypeptidase (DacA) to 32 for estrogen receptor α (ERα) [11]. A larger active set generally provides a more statistically robust validation.

Table 1: Examples of Active Compound Sets Used in Various Studies

| Target Protein | Number of Actives | Activity Range (IC₅₀) | Source/Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brd4 | 36 | Varied (from literature) | ChEMBL & Literature [7] |

| SARS-CoV-2 PLpro | 23 | 0.1 - 5.7 µM | Literature [9] |

| Akt2 | 23 (Training Set) | Spans 5 orders of magnitude | Merck Research Labs [10] |

| XIAP | 10 | e.g., 40 nM for CID: 46781908 | ChEMBL & Literature [12] |

| DacA | 3 | Not Specified | DUD-E [11] |

Core Component 2: Decoy Molecules

The Purpose and Evolution of Decoys

Decoys are molecules presumed to be inactive against the target and are used to mimic the "noise" of a real compound library. A well-constructed decoy set is critical for a realistic assessment of a method's discrimination power. The selection of decoys has evolved significantly, from simple random selection to sophisticated, property-matched protocols designed to minimize bias [13].

Early benchmarking databases used decoys that were randomly selected from large chemical databases like the Available Chemicals Directory (ACD) or the MDL Drug Data Report (MDDR). This approach often led to a significant physicochemical disparity between the active and decoy compounds. The virtual screening method could then easily distinguish actives based on simple properties like molecular weight, rather than true biological activity, leading to an artificial overestimation of the enrichment [13].

To address this, the concept of property-matched decoys was introduced. The Directory of Useful Decoys (DUD) database, a landmark in this evolution, established a protocol where decoys are matched to active compounds on key properties like molecular weight, calculated LogP, and hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, but are topologically dissimilar to avoid true activity [13]. This philosophy is continued and refined in its successor, the DUD-E (Enhanced DUD) database [14].

Modern Decoy Selection Methodologies

Current best practices for decoy selection involve rigorous matching and filtering:

- Physicochemical Matching: Decoys are selected to have similar one-dimensional (1D) physicochemical properties as the actives. This ensures the method is tested on its ability to identify activity, not just to filter out "drug-like" from "non-drug-like" molecules.

- Topological Dissimilarity: Despite physicochemical similarity, decoys are chosen to be dissimilar in two-dimensional (2D) structure (e.g., based on molecular fingerprints like ECFP4) to reduce the likelihood that they are actually active [14].

- Commercially Available and Drug-like: Modern decoy sets are often compiled from purchasable, "drug-like" compound subsets of databases like ZINC to reflect real-world screening scenarios [13].

- Experimentally Validated Inactives: The gold standard, though less common due to scarcity of data, is the use of compounds that have been experimentally confirmed to be inactive [13].

Table 2: Evolution of Decoy Selection Strategies

| Strategy | Description | Key Advantage | Potential Bias |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random Selection | Decoys randomly picked from large chemical directories. | Simple to implement. | High risk of artificial enrichment due to property mismatches. |

| Property-Matched (e.g., DUD/DUD-E) | Decoys matched to actives on key 1D properties but are topologically dissimilar. | Reduces bias, provides a more challenging and realistic test. | The quality of matching can vary; may not fully capture 3D complexity. |

| True Inactives | Use of compounds experimentally confirmed to be inactive. | Provides the most realistic benchmark. | Data is scarce and difficult to obtain for many targets. |

Core Component 3: Database Size and Composition

The Final Denominator in EF Calculation

The total size of the screening database (N) is the denominator in the EF calculation formula and thus has a direct mathematical impact on the result. The database is composed of the active compounds (A) and the decoy compounds (D), such that N = A + D. In practice, since the number of decoys (D) is typically much larger than the number of actives (A), the database size is largely determined by the number of decoys selected.

The formula for Enrichment Factor at a given percentage of the database screened (e.g., EF₁%) is:

EF{subset} = (TP / N{subset}) / (A / N) [14]

Where:

- TP is the number of true positives (retrieved actives) in the subset.

- N_{subset} is the size of the subset considered (e.g., top 1% of the database).

- A is the total number of active compounds in the database.

- N is the total number of compounds in the database.

Standardization and Its Impact

Using a standardized and consistent database size is critical for the fair comparison of different virtual screening methods. If two methods are tested on databases of different sizes, their EF values are not directly comparable, as the random hit rate (A/N) is different.

Common benchmarking databases and protocols often use a large and fixed ratio of decoys to actives. For example, the DUD database contains a total of 95,316 decoys for 2,950 ligands across 40 targets, averaging about 36 decoys per active [13]. This standardization allows for meaningful cross-target and cross-method comparisons. Studies have shown that using a large pool of property-matched decoys (e.g., thousands of compounds) provides a more statistically significant and rigorous assessment of performance than using a small, trivial dataset [11] [13].

Experimental Protocols for EF Calculation

Standard Workflow for Model Validation

The validation of a pharmacophore model using EF typically follows a well-defined workflow, integrating the three core components. The diagram below illustrates this standard protocol, from data preparation to performance evaluation.

Detailed Methodology

The workflow involves several critical steps, each requiring careful execution:

Data Preparation: The first and most crucial step is building a high-quality benchmarking dataset.

- Active Compilation: As detailed in Section 2.1, known actives are gathered from public databases like ChEMBL or from scientific literature. For example, in the XIAP inhibitor study, 10 active antagonists were collected from ChEMBL and literature to form the active set [12].

- Decoy Generation: Using a tool like DUD-E, a set of decoys is generated for the compiled actives. The study on Brd4 inhibitors submitted their 36 active compounds to the DUD-E server to retrieve corresponding decoys [7]. The final dataset for this study contained a total of 472 compounds (36 actives + 436 decoys) [7].

- Database Merging: The actives and decoys are merged into a single database file (e.g., in SDF or other compatible formats) for screening.

Virtual Screening Run: The pharmacophore model is used as a query to screen the benchmarking database. Software like LigandScout or Catalyst is typically used for this step. The screening process scores and ranks every compound in the database based on its fit value to the pharmacophore model.

Results Analysis & Ranking: The output of the screening is a list of all compounds, ranked from best fit to worst. This list is analyzed to determine the positions of the known active compounds within the ranked list.

EF Calculation: The enrichment factor is calculated at a specific early fraction of the screened database. The most common benchmarks are EF₁% and EF₅%, representing the enrichment at the top 1% and 5% of the ranked list, respectively.

- For instance, if a database of 10,000 compounds (N) contains 50 actives (A), the random hit rate at 1% (100 compounds) would be (50 / 10000) = 0.5%. If a pharmacophore model retrieves 10 actives within the top 100 compounds (TP=10), the EF₁% is calculated as: (10 / 100) / (50 / 10000) = 0.1 / 0.005 = 20.

Performance Evaluation: The calculated EF is interpreted. A value of 1 indicates random performance, while higher values indicate better enrichment. The model's quality is often further validated by analyzing the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve and the Area Under the Curve (AUC) [7] [12] [14].

Comparative Performance Data

EF as a Validation Metric in Published Studies

The Enrichment Factor is widely reported in the literature to demonstrate the predictive power of virtual screening methods. The following table compiles EF and related performance data from recent pharmacophore modeling studies, showcasing its application across diverse therapeutic targets.

Table 3: Reported Enrichment Factors in Pharmacophore Model Validation Studies

| Therapeutic Target | Model Type | Database Size (N) | EF at 1% (EF₁%) | ROC-AUC | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brd4 [7] | Structure-Based | 472 | Not Specified | 1.0 | The model showed excellent discriminatory power. |

| XIAP [12] | Structure-Based | 5,209 | 10.0 | 0.98 | High early enrichment with an EF of 10 at 1%. |

| SARS-CoV-2 Mpro [15] | Water Pharmacophore (CWFEP) | Not Specified | Not Specified | 0.81 | Achieved an Active Hit Rate (AHR) of 70%. |

| SARS-CoV-2 PLpro [9] | Structure-Based | 743 (23 actives + 720 decoys) | Reported via curve | >0.5 (Valid model) | Model validated against property-matched decoys from DEKOIS 2.0. |

Pharmacophore vs. Docking Performance

A benchmark comparison study across eight diverse protein targets provides valuable insight into the relative performance of pharmacophore-based virtual screening (PBVS) versus docking-based virtual screening (DBVS). The results strongly support the use of pharmacophore models for initial screening.

Table 4: PBVS vs. DBVS: Average Hit Rates at Top 2% and 5% of Database [11]

| Virtual Screening Method | Average Hit Rate at Top 2% | Average Hit Rate at Top 5% |

|---|---|---|

| Pharmacophore-Based (PBVS) | Much Higher | Much Higher |

| Docking-Based (DBVS) | Lower | Lower |

The study concluded that in 14 out of 16 test cases, PBVS demonstrated higher enrichment factors than DBVS, establishing it as a powerful method for retrieving active compounds from large databases [11]. This underscores the importance of a well-validated pharmacophore model, for which accurate EF calculation is paramount.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

To conduct a rigorous enrichment factor analysis for pharmacophore validation, researchers require a specific set of computational tools and data resources. The following table details these essential components.

Table 5: Key Research Reagents for EF Calculation

| Reagent / Resource | Type | Primary Function in EF Analysis | Example Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Known Active Compounds | Dataset | Serves as the positive control set to be enriched by the model. | ChEMBL, PubChem BioAssay, Scientific Literature [7] [12] |

| Decoy Set Generator | Software Tool | Generates property-matched, putative inactive compounds for a given set of actives. | DUD-E (Database of Useful Decoys: Enhanced) [14] [9] |

| Pharmacophore Modeling Software | Software Platform | Used to create the pharmacophore model and perform the virtual screening of the benchmark database. | LigandScout [7] [12] [9], Catalyst [11], Schrodinger [14] |

| Benchmarking Database | Curated Dataset | Provides a pre-compiled set of actives and decoys for standardized testing. | DUD-E [14], DEKOIS 2.0 [9] |

| Chemical Database | Compound Library | Source for purchasable compounds for prospective virtual screening after model validation. | ZINC [7] [12] [10], CMNPD [9] |

The rigorous validation of a pharmacophore model through Enrichment Factor analysis hinges on the meticulous management of three interdependent components: a set of experimentally validated active compounds, a carefully curated set of property-matched decoys, and a defined screening database. The evolution from randomly selected decoys to sophisticated, matched sets available through resources like DUD-E has significantly improved the reliability and realism of virtual screening benchmarks. Experimental data consistently shows that pharmacophore models validated using these robust protocols demonstrate strong performance, often outperforming other virtual screening methods in early enrichment. By adhering to detailed experimental workflows and utilizing the essential tools outlined in this guide, researchers and drug development professionals can confidently employ EF as a critical metric to guide the selection and optimization of pharmacophore models, thereby de-risking the early stages of drug discovery.

In the field of computer-aided drug design, the Enrichment Factor (EF) is a crucial metric for evaluating the performance of virtual screening methods, including pharmacophore modeling, molecular docking, and QSAR-based approaches [2]. Virtual screening allows researchers to computationally sift through large chemical databases to identify potential hit compounds, saving substantial time and resources compared to experimental high-throughput screening alone [12]. EF quantitatively measures the ability of these computational methods to prioritize active compounds over inactive ones by calculating the enrichment of true positives within a selected top fraction of the screened database compared to what would be expected by random selection [2] [12]. This metric provides researchers with a straightforward, interpretable value to assess whether a virtual screening method offers genuine predictive power or merely reflects chance occurrence.

The mathematical calculation of EF directly compares the performance of a screening method against random selection. The standard formula for enrichment factor is:

EF = (Hitssampled / Nsampled) / (Hitstotal / Ntotal)

Where Hitssampled represents the number of active compounds found in the top fraction of the ranked database, Nsampled is the size of that top fraction, Hitstotal is the total number of active compounds in the entire database, and Ntotal is the total number of compounds in the database [2]. The denominator (Hitstotal / Ntotal) represents the baseline random selection scenario, where any compound selected randomly from the database has an equal probability of being active. An EF value of 1 indicates performance equivalent to random selection, while values increasingly greater than 1 indicate progressively better enrichment of active compounds in the top-ranked fraction.

EF Interpretation Framework: From Baseline to Ideal

Quantitative Interpretation of EF Values

The table below provides a standard framework for interpreting EF values in virtual screening experiments, particularly in pharmacophore model validation and related computational drug discovery approaches:

| EF Value Range | Interpretation | Performance Classification |

|---|---|---|

| EF = 1 | Baseline/Random | No enrichment beyond random selection |

| 1 < EF < 5 | Moderate Enrichment | Meaningful but modest predictive power |

| 5 < EF < 10 | Good Enrichment | Substantial improvement over random |

| EF > 10 | Excellent Enrichment | High-quality model with strong predictive power |

| EF = EFmax | Theoretical Maximum | Ideal performance (all actives ranked first) |

For a virtual screening method to be considered practically useful, it typically needs to achieve EF values significantly greater than 1. Research indicates that EF values greater than 10 are particularly noteworthy, demonstrating excellent enrichment capable of dramatically reducing the number of compounds requiring experimental testing [2]. In one study on COX-2 inhibitors, researchers considered their pharmacophore model validated specifically because it demonstrated "good ability to identify active compounds" with strong EF values [2]. Another study on XIAP inhibitors reported an exceptional early enrichment factor (EF1%) of 10.0, indicating that their method identified true actives ten times more effectively than random screening in the top 1% of the database [12].

Contextual Factors in EF Interpretation

Several important contextual factors influence the interpretation of EF values:

The EFmax (Maximum Possible EF) represents the theoretical upper limit where all active compounds are perfectly ranked at the top of the list [16]. It is calculated as EFmax = (Ntotal / Hitstotal) when Nsampled ≥ Hitstotal. The ratio EF/EFmax provides a normalized metric that accounts for the fact that EF values are constrained by the ratio of total to active compounds in different datasets [16].

The Sampled Fraction Size significantly impacts reported EF values. EF is typically calculated at specific early enrichment levels, commonly 0.5%, 1%, 2%, or 5% of the ranked database [12] [17]. For example, EF1% refers to enrichment within the top 1% of the database. Early enrichment (small fractions) is particularly important in virtual screening as it reflects the ability to identify actives with minimal experimental effort.

Database Composition affects EF values, as databases with higher ratios of active to inactive compounds naturally allow for higher maximum enrichment factors. This is why comparing EF values across different datasets requires caution unless normalized metrics like EF/EFmax are used [16].

Experimental Protocols for EF Calculation

Standard Validation Methodology Using Decoy Sets

The most rigorous approach for EF calculation involves testing a computational model against a dataset containing known active compounds and experimentally validated inactive compounds (decoys):

Detailed Protocol:

- Prepare Known Actives: Curate a set of 10-100 compounds with experimentally confirmed activity against the target (e.g., IC50 < 10 μM) [18] [17]. This set should be representative of known chemotypes but not identical to training compounds if validating a QSAR model.

- Generate Decoy Set: Use tools like DUD-E (Database of Useful Decoys: Enhanced) or DecoyFinder to generate decoy molecules [18]. Decoys should have similar physical properties (molecular weight, logP, hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, rotatable bonds) to actives but different 2D topology to ensure they are inactive [18].

- Merge and Screen: Combine actives and decoys into a single test database, then screen using the pharmacophore model or other virtual screening method.

- Rank and Calculate: Rank compounds based on the screening score (e.g., fit value for pharmacophores, docking score for docking studies) and calculate EF values at multiple fractions of the ranked database [2] [12].

- Statistical Validation: Calculate complementary metrics including AUC-ROC, sensitivity, specificity, and goodness of hit (GH) score for comprehensive validation [2] [18].

Case Study: EF Validation in Practice

A study on sigma-1 receptor (σ1R) ligands provides an excellent example of rigorous EF validation [17]. Researchers evaluated their pharmacophore model against a large dataset of over 25,000 compounds with experimentally determined σ1R affinity. They calculated EF values at different fractions of the screened sample and reported "enrichment values above 3 at different fractions of screened samples," with their best model (5HK1–Ph.B) achieving a ROC-AUC value above 0.8 [17]. This comprehensive validation against a large experimental dataset provides high confidence in the model's predictive power for identifying novel sigma-1 receptor ligands.

Complementary Validation Metrics

While EF provides a valuable measure of early enrichment, comprehensive model validation requires multiple complementary metrics:

| Metric | Calculation | Interpretation | Optimal Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| AUC-ROC | Area under Receiver Operating Characteristic curve | Overall ability to distinguish actives from inactives | 0.9-1.0 (Excellent) |

| Sensitivity (Recall) | TP / (TP + FN) | Ability to identify true actives | Close to 1.0 |

| Specificity | TN / (TN + FP) | Ability to exclude inactives | Close to 1.0 |

| Goodness of Hit (GH) Score | Complex function of EF and coverage | Combined quality measure | 0.6-1.0 (Good to Excellent) |

| EF/EFmax Ratio | EF / Maximum Possible EF | Normalized enrichment measure | Close to 1.0 |

The Goodness of Hit (GH) Score is particularly valuable as it incorporates both enrichment and the recall of actives, providing a balanced assessment of model quality [2] [18]. GH score is calculated using the formula:

GH = [(Ha(3A + Ht)) / (4HtA)] × (1 - (Ht - Ha)/(D - A))]

Where Ha is the number of actives in the hit list, Ht is the hit list size, A is the number of actives in the database, and D is the total number of compounds in the database [18]. GH scores range from 0-1, with values above 0.6 indicating good to excellent models.

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below outlines essential computational tools and resources for conducting enrichment factor analysis in pharmacophore model validation:

| Resource/Tool | Type | Primary Function | Application in EF Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| DUD-E (Database of Useful Decoys: Enhanced) | Decoy Database | Provides property-matched decoys for known actives | Creates validation sets for calculating EF values [2] [18] |

| ZINC Database | Compound Database | Curated collection of commercially available compounds | Source of natural products & synthetic compounds for virtual screening [2] [12] |

| LigandScout | Software Platform | Advanced molecular design & pharmacophore modeling | Generates and validates pharmacophore models for screening [2] [7] |

| DecoyFinder | Standalone Tool | Generates decoy sets for specific target classes | Alternative to DUD-E for custom validation sets [18] |

| Schrodinger Suite | Software Platform | Comprehensive drug discovery platform | Includes enrichment analysis metrics and visualization [19] |

Proper interpretation of Enrichment Factors requires understanding the spectrum from baseline random selection (EF=1) to ideal enrichment (EF=EFmax). Excellent pharmacophore models typically achieve EF values significantly greater than 1, with EF>10 representing particularly strong performance in early enrichment [2] [12]. However, EF should never be interpreted in isolation—comprehensive validation requires multiple metrics including AUC-ROC, sensitivity, specificity, and goodness of hit scores to fully assess model performance [2] [18] [17]. The standardized experimental protocols and complementary interpretation frameworks presented in this guide provide researchers with a robust methodology for rigorously validating virtual screening approaches in drug discovery campaigns.

The Relationship Between EF, ROC Curves, and Goodness-of-Hit (GH) Score

In the field of computer-aided drug design, pharmacophore models serve as abstract representations of the steric and electronic features necessary for a molecule to interact with a specific biological target [20] [21]. The predictive performance and reliability of these models must be rigorously validated before their application in virtual screening campaigns. Three fundamental metrics form the cornerstone of this validation process: the Enrichment Factor (EF), the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve, and the Goodness-of-Hit (GH) score [2] [22] [12]. These quantitative measures collectively assess a model's ability to distinguish active compounds from inactive ones, providing researchers with critical insights into its potential for identifying novel drug candidates. EF provides a straightforward measure of early enrichment capability, the ROC curve offers a comprehensive visual representation of classification performance across all thresholds, and the GH score delivers a single value that balances the recall of actives with the precision of the hit list [23] [7]. Understanding the interrelationship between these metrics is essential for researchers engaged in enrichment factor analysis and pharmacophore model validation, as each offers complementary information that guides the selection and optimization of virtual screening strategies.

Theoretical Foundations of Key Validation Metrics

Enrichment Factor (EF)

The Enrichment Factor is a decisive metric that quantifies the effectiveness of a virtual screening method in concentrating active compounds early in the ranked list compared to a random selection. It is defined as the ratio of the fraction of actives found in a specified top portion of the screened database to the fraction of actives expected in that same portion through random selection [2] [12]. Mathematically, this is expressed as:

EF = (Hitssampled / Nsampled) / (Hitstotal / Ntotal)

where Hitssampled represents the number of active compounds identified in the top fraction of the screened database, Nsampled is the total number of compounds in that top fraction, Hitstotal is the total number of active compounds in the entire database, and Ntotal is the total number of compounds in the database [12]. The EF metric is particularly valuable in virtual screening contexts where early enrichment is paramount, as it directly measures a model's ability to prioritize potentially valuable compounds for further experimental testing. Researchers often calculate EF at multiple thresholds (such as 1% or 5%) to understand the enrichment behavior at different stages of the screening process [23]. For example, a study on COX-2 inhibitors reported excellent enrichment with EF values ranging from 11.4 to 13.1 at a 1% threshold, indicating that the pharmacophore model identified 11-13 times more actives in the top 1% of the ranked list than would be expected by chance [7].

ROC Curves and AUC Analysis

The Receiver Operating Characteristic curve provides a comprehensive graphical representation of a classification model's performance across all possible classification thresholds [2] [22]. In virtual screening applications, the ROC curve plots the true positive rate (sensitivity) against the false positive rate (1-specificity) as the threshold for considering a compound "active" is varied [23]. The true positive rate is calculated as TPR = TP/(TP+FN), while the false positive rate is FPR = FP/(FP+TN), where TP denotes true positives, FN false negatives, FP false positives, and TN true negatives [2].

The Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC) serves as a single-figure summary of the model's overall classification performance, with values ranging from 0 to 1 [12]. A perfect classifier achieves an AUC of 1.0, while a random classifier yields an AUC of 0.5 [2]. The following table presents typical interpretation guidelines for AUC values in virtual screening contexts:

Table 1: Interpretation of AUC Values in Pharmacophore Model Validation

| AUC Value Range | Classification Performance | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| 0.90 - 1.00 | Excellent | Model highly discriminates actives from inactives |

| 0.80 - 0.90 | Good | Model has good discrimination capability |

| 0.70 - 0.80 | Fair | Model has moderate discrimination capability |

| 0.60 - 0.70 | Poor | Model has limited discrimination capability |

| 0.50 - 0.60 | Fail | Model performs no better than random selection |

In research practice, a study on XIAP inhibitors reported an exceptional AUC value of 1.0, indicating perfect classification performance in their validation set, while a study on class IIa HDAC inhibitors demonstrated a robust AUC value of 0.98, confirming excellent model discriminatory power [22] [12].

Goodness-of-Hit (GH) Score

The Goodness-of-Hit score represents a composite metric that integrates both the recall of active compounds and the precision of the hit list into a single value ranging from 0 to 1, where 1 indicates perfect enrichment [22] [7]. The GH score incorporates three fundamental components: the percentage of identified actives (Ha), the percentage of screened compounds yielding these actives (Ht), and the total ratio of actives in the database (A). The calculation involves the following formula:

GH = [(3/4) × Ha + (1/4) × Ht] × (1 - (Ht - A)/Ht)

This formulation intentionally weights recall more heavily than precision, reflecting the practical reality that identifying a higher proportion of true actives is often more valuable in early drug discovery than minimizing false positives [7]. The GH score effectively penalizes models that achieve high recall rates only by selecting excessively large portions of the database, thus encouraging both comprehensive coverage of actives and selectivity in compound selection. A GH score approaching 1 indicates that a model successfully identifies most active compounds while screening only a small fraction of the database, representing the ideal scenario for virtual screening applications [22].

Comparative Analysis of Validation Metrics

The relationship between EF, ROC curves, and GH score can be understood through their complementary strengths and the specific aspects of model performance they emphasize. The following table provides a systematic comparison of these key validation metrics:

Table 2: Comprehensive Comparison of Pharmacophore Validation Metrics

| Metric | Core Focus | Calculation Components | Optimal Value | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enrichment Factor (EF) | Early enrichment capability | Hitssampled, Nsampled, Hitstotal, Ntotal [12] | >1 (Higher indicates better performance) | Intuitive interpretation; Directly relevant to practical screening efficiency |

| ROC Curve & AUC | Overall classification performance | True Positive Rate, False Positive Rate [2] | AUC: 1.0 (Perfect classifier) | Comprehensive threshold-independent assessment; Visual interpretation advantage |

| Goodness-of-Hit (GH) | Balanced recall and precision | Ha (hit rate), Ht (screened fraction), A (active ratio) [7] | 1.0 (Perfect enrichment) | Composite metric balancing multiple performance aspects; Penalizes excessive screening |

These metrics interrelate through their shared goal of quantifying model effectiveness while emphasizing different aspects of performance. EF provides crucial information about early enrichment that is particularly valuable in resource-constrained screening environments, while the ROC curve provides a more comprehensive view of performance across all operating thresholds [23]. The GH score serves as a balanced composite metric that incorporates elements of both, rewarding models that identify a high percentage of actives without requiring excessive screening of the database [22] [7]. A robust pharmacophore validation strategy should incorporate all three metrics to obtain a complete picture of model performance, as each reveals different facets of the model's strengths and limitations.

Experimental Protocols for Metric Evaluation

Standard Validation Workflow

The validation of pharmacophore models follows a systematic workflow that incorporates the calculation of EF, ROC curves, and GH scores. The standard protocol begins with the preparation of a validation dataset containing known active compounds and decoy molecules that resemble drug-like compounds but are presumed inactive [2] [12]. The critical first step involves curating a set of known active compounds, typically obtained from literature or databases like ChEMBL, accompanied by a substantially larger set of decoy compounds from resources such as the Directory of Useful Decoys (DUD-E) [12] [24]. The pharmacophore model is then used to screen this combined dataset, with each compound receiving a score or fit value reflecting how well it matches the pharmacophore features [20].

Based on these scores, compounds are ranked from best to worst match, enabling the calculation of all three validation metrics at various threshold levels [23]. The entire workflow is depicted in the following diagram:

Implementation Guidelines

Successful implementation of the validation protocol requires careful attention to several methodological considerations. The selection of decoy compounds should ensure they are physically similar but chemically distinct from the active compounds to prevent artificially inflated performance metrics [12]. When calculating EF, researchers should consistently report the threshold percentage used (typically 0.5%, 1%, 2%, or 5%) to enable meaningful cross-study comparisons [23]. For ROC curve analysis, it's essential to use the entire dataset rather than a subset to avoid biased AUC estimates [2]. The calculation of GH scores should follow the standard formula to maintain consistency with published research [7]. Multiple research groups have successfully implemented this comprehensive validation approach, including studies on COX-2 inhibitors, class IIa HDAC inhibitors, and XIAP inhibitors, demonstrating its broad applicability across different target classes [2] [22] [12].

Research Reagent Solutions for Validation Studies

The experimental validation of pharmacophore models relies on several essential computational tools and databases that collectively form the research reagent toolkit. The following table details these key resources and their specific functions in the validation process:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Pharmacophore Validation Studies

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Validation | Example Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| DUD-E Database | Decoy Compound Repository | Provides chemically matched decoys for known actives to prevent bias [12] | Used in XIAP inhibitor study with 36 actives & corresponding decoys [12] |

| ZINC Database | Purchasable Compound Library | Source of commercially available compounds for virtual screening [2] [7] | Screened for natural COX-2 inhibitors; contains 230M+ purchasable compounds [7] |

| ChEMBL Database | Bioactivity Database | Provides curated known active compounds with experimental IC50 values [12] [24] | Source of 20 known MAOB active antagonists for model validation [24] |

| LigandScout Software | Pharmacophore Modeling | Creates structure-based & ligand-based pharmacophore models; calculates features [2] [12] | Generated pharmacophore models for COX-2 & XIAP inhibitors [2] [12] |

| ZINCPharmer | Online Screening Tool | Performs pharmacophore-based screening of ZINC database [24] | Initial screening target for MAOB protein inhibitors [24] |

These research reagents form an integrated ecosystem that supports the entire validation workflow, from model creation and dataset preparation to screening and metric calculation. The consistent use of these well-established resources across multiple studies enables meaningful comparisons of validation results between different research projects and pharmacophore models [2] [12] [24].

Interrelationships and Practical Interpretation

The relationship between EF, ROC curves, and GH scores extends beyond their individual definitions to encompass important synergies in practical applications. These metrics form a complementary triad that collectively provides a more complete assessment of pharmacophore model performance than any single metric could offer independently [2] [22] [7]. The ROC curve and its associated AUC value offer the broadest perspective, illustrating the model's classification performance across all possible thresholds and providing a reliable indicator of overall discriminatory power [23]. The EF metric then adds crucial focus on early enrichment behavior, which directly corresponds to practical screening efficiency and resource allocation in drug discovery campaigns [12]. Finally, the GH score integrates concerns about both comprehensive active retrieval and screening efficiency, serving as a balanced figure-of-merit that aligns with the economic constraints of real-world screening operations [7].

This interpretative framework finds practical application across diverse therapeutic targets. In a study on COX-2 inhibitors, researchers obtained excellent values across all three metrics (high EF, AUC of 0.98, and strong GH score), indicating a robust and practically useful model [2]. Similarly, research on BET inhibitors for neuroblastoma reported an exceptional AUC of 1.0 coupled with strong EF values ranging from 11.4 to 13.1, demonstrating nearly ideal classification and enrichment performance [7]. These consistent findings across different target classes reinforce the value of the comprehensive three-metric approach and provide benchmark values for researchers validating new pharmacophore models. The integrated application of EF, ROC curves, and GH scores thus represents a best-practice methodology in pharmacophore model validation, ensuring both statistical rigor and practical relevance in virtual screening applications.

In the field of computer-aided drug design, virtual screening serves as a critical tool for rapidly identifying potential lead compounds from extensive chemical databases. The practical value of any virtual screening method hinges on its ability to distinguish truly active molecules from inactive ones efficiently. The Enrichment Factor (EF) has emerged as a pivotal metric for quantifying this performance, providing researchers with a straightforward, interpretable measure of how effectively a computational model prioritizes active compounds early in the screening process [14]. Unlike simple accuracy metrics, EF directly connects model performance to real-world screening efficiency by measuring the concentration of active compounds found in a selected top fraction of the screened database compared to a random selection [14]. This article explores the central role of EF in validating pharmacophore models, provides protocols for its calculation, and demonstrates through comparative data how EF serves as a crucial bridge between algorithmic performance and practical screening success.

Theoretical Foundations and Calculation of EF

Defining the Enrichment Factor

The Enrichment Factor (EF) is a metric that describes the number of active compounds found by using a specific pharmacophore model as opposed to the number hypothetically found if compounds were screened randomly [14]. Mathematically, it is defined as the ratio of the hit rate in a selected top fraction of the screened database to the hit rate in the entire database. The standard calculation for EF is expressed as:

$$EF{subset} = \frac{(N{hit}^{subset} / N{subset})}{(N{total}^{actives} / N_{total})}$$

Where:

- $N_{hit}^{subset}$ = number of active compounds in the selected subset

- $N_{subset}$ = total number of compounds in the selected subset

- $N_{total}^{actives}$ = total number of active compounds in the entire database

- $N_{total}$ = total number of compounds in the entire database [14]

This calculation can be applied at different thresholds of the screened database (e.g., EF1%, EF5%, EF10%), providing insights into the "early enrichment" capability of a model—a critical factor for practical screening efficiency where resources for experimental validation are often limited to only the top-ranked compounds.

EF in Context: Related Validation Metrics

While EF provides crucial information about early enrichment, comprehensive pharmacophore model validation typically employs multiple complementary metrics:

- Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) Curves: Visualize the trade-off between sensitivity (true positive rate) and specificity (false positive rate) across all classification thresholds [7] [12] [14]. A perfect model achieves an area under the curve (AUC) of 1.0, while random performance yields an AUC of 0.5 [12].

- Area Under the Curve (AUC): Provides a single-figure measure of overall model performance across all possible thresholds [7] [12].

- Güner-Henry (GH) Score: A composite metric that balances recall and precision while accounting for the size of the active compound set [7].

The relationship between these validation approaches and EF analysis can be visualized in the following workflow:

Experimental Protocols for EF Assessment

Standard EF Validation Methodology

A robust protocol for EF assessment requires carefully designed experiments and control sets. The following methodology has been widely adopted in pharmacophore model validation studies:

Preparation of Test Sets:

- Collect known active compounds against the target protein from literature and databases like ChEMBL [7] [12].

- Generate decoy molecules with similar physicochemical properties but dissimilar 2D topology using databases such as DUD-E (Database of Useful Decoys: Enhanced) [12] [14]. The DUD-E database provides known actives and decoys that are calculated using similar 1D physico-chemical properties as the actives but dissimilar 2D topology based on ECFP4 fingerprints [14].

Virtual Screening Execution:

EF Calculation:

- Select assessment thresholds (typically 0.5%, 1%, 2%, 5%, and 10% of the ranked database) [14].

- Count the number of active compounds recovered at each threshold.

- Calculate EF values using the standard formula for each threshold.

Comparative Analysis:

Key Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 1: Essential Research Tools for EF Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function in EF Analysis | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| DUD-E Database | Database | Provides known actives and property-matched decoys | Creating unbiased validation sets [12] [14] |

| LigandScout | Software | Structure-based pharmacophore modeling and virtual screening | Generating and validating pharmacophore models [7] [12] [14] |

| ZINC Database | Database | Curated collection of commercially available compounds | Source of natural products and synthetic compounds for screening [7] [12] |

| ROC Curve Analysis | Statistical Method | Visualizing model performance across all thresholds | Determining AUC values [7] [12] |

| Molecular Dynamics Simulations | Computational Method | Refining protein-ligand structures for improved modeling | Enhancing pharmacophore model accuracy [14] |

Comparative Performance Data

EF Values in Published Pharmacophore Studies

Recent research publications provide substantial data on typical EF values achieved by validated pharmacophore models, offering benchmarks for model performance assessment:

Table 2: EF Performance in Recent Pharmacophore Studies

| Study Target | Screening Database | EF1% | EF5% | AUC | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brd4 Protein (Neuroblastoma) | Natural Compound Library | 11.4-13.1 | N/R | 1.0 | [7] |

| XIAP Protein (Cancer) | ZINC Database | 10.0 | N/R | 0.98 | [12] |

| FKBP12 Protein | DUD-E Database | N/R | N/R | 0.70-0.98* | [14] |

| Abl Kinase | DUD-E Database | N/R | N/R | 0.70-0.98* | [14] |

| HSP90-alpha | DUD-E Database | N/R | N/R | 0.70-0.98* | [14] |

*Range across six different protein systems studied [14]

The exceptional EF values of 11.4-13.1 at 1% threshold in the Brd4 protein study indicate that the pharmacophore model identified 11-13 times more active compounds in the top 1% of screened compounds than would be expected by random selection [7]. Similarly, the XIAP-targeting model achieved an EF of 10.0 at 1% threshold, demonstrating excellent early enrichment capability [12]. These values correlate strongly with the nearly perfect AUC values of 1.0 and 0.98, respectively, confirming the overall robustness of the models [7] [12].

MD-Refined vs. Crystal Structure Pharmacophore Models

A comparative study investigating pharmacophore models derived from crystal structures versus molecular dynamics (MD)-refined structures revealed important insights for EF optimization:

Table 3: MD-Refined vs. Crystal Structure Pharmacophore Models

| Protein System (PDB Code) | Model Type | Performance Improvement | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Six Diverse Protein Systems | Crystal Structure (Initial) | Baseline | Standard approach using PDB coordinates [14] |

| Same Six Systems | MD-Refined (Final) | Better discrimination in some cases | Models differed in feature number and type [14] |

| All Systems | Combined Approach | Complementary information | MD-refined models resolved crystal structure limitations [14] |

This research demonstrated that pharmacophore models derived from the final frames of MD simulations frequently differed in feature number and type compared to their crystal structure-derived counterparts [14]. In several cases, these MD-refined models showed improved ability to distinguish between active and decoy compounds, as measured by ROC curves and enrichment factors [14]. The study highlights how incorporating dynamic protein behavior can enhance model fidelity and subsequent screening efficiency.

Connecting EF to Real-World Screening Efficiency

Practical Implications of EF Values

The translation of EF values to practical screening efficiency can be quantified through the reduction in experimental burden:

High EF values directly translate to significant resource savings in drug discovery campaigns. For example, in a virtual screening of 100,000 compounds where 100 are truly active:

- Random screening would identify approximately 1 active compound in the top 1,000 compounds (1%)

- A model with EF=10 would identify 10 active compounds in the same number of tests

- A model with EF=13 would identify 13 active compounds [7]

This 10-13 fold enrichment means that researchers can identify the same number of active compounds by testing only 7.7%-10% as many samples, resulting in substantial savings in time, materials, and computational resources.

EF as a Decision Metric in Screening Strategy

Beyond mere performance assessment, EF serves as a critical decision metric for selecting appropriate screening strategies:

Database Selection: Models with higher early EF values (EF1%) are better suited for larger database screens where only the top-ranked compounds will undergo experimental validation.

Scaffold Hopping Potential: High EF values often correlate with models capable of identifying structurally diverse actives, as demonstrated by pharmacophore models that successfully identified novel natural product inhibitors with different scaffolds from known synthetic compounds [7] [12].

Protocol Optimization: EF analysis helps researchers balance sensitivity and specificity by selecting appropriate fit-value cutoffs that maximize the recovery of active compounds while minimizing false positives.

Resource Allocation: The EF metric guides practical decisions about screening investments, with higher EF values justifying more extensive experimental follow-up on top-ranked hits.

Enrichment Factor analysis represents far more than an abstract validation metric—it provides a direct quantitative connection between pharmacophore model performance and real-world screening efficiency. The comparative data presented in this review demonstrates that EF values consistently correlate with the practical utility of computational models in identifying bioactive compounds from complex chemical libraries. Through standardized experimental protocols and appropriate interpretation of EF in conjunction with complementary metrics like AUC, researchers can make informed decisions about virtual screening strategies that maximize resource efficiency in drug discovery. As pharmacophore modeling continues to evolve with integration of molecular dynamics refinements [14] and machine learning approaches [26], EF remains an essential measure for translating computational advances into tangible improvements in screening outcomes.

How to Calculate and Apply Enrichment Factor Analysis: A Step-by-Step Protocol

The preparation of a robust validation set is a critical first step in the objective evaluation of pharmacophore models. The choice of decoys—compounds presumed to be inactive—can profoundly influence the outcome of enrichment factor analysis, making their rational selection a cornerstone of reliable virtual screening (VS) validation [13]. This guide provides a comparative overview of decoy selection methodologies, their associated experimental protocols, and their impact on performance assessment.

The Evolution and Impact of Decoy Selection Strategies

The methodology for selecting decoy compounds has evolved significantly, moving from simple random selection to complex, property-matched strategies designed to minimize bias in VS benchmarking [13].

Historical and Modern Decoy Selection Workflows

The table below summarizes the key stages in the development of decoy selection strategies.

Table 1: Evolution of Decoy Selection Methodologies for Benchmarking Sets

| Era & Strategy | Core Principle | Key Features | Inherent Biases & Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early 2000s: Random Selection [13] | Selection of putative inactives through random sampling from large chemical databases (e.g., ACD, MDDR). | Simple and fast to implement; requires minimal computational resources. | Introduces significant artificial enrichment; active and decoy sets often differ drastically in physicochemical properties, making discrimination trivial [13]. |

| Mid-2000s: Physicochemical Filtering [13] | Application of filters (e.g., molecular weight, polarity) to decoys to make them more "drug-like" and broadly comparable to actives. | A step towards more realistic benchmarking; reduced the ease of discrimination based on simple properties like size. | Property distributions of actives and decoys could still be very different, leading to over-optimistic performance estimates [13]. |

| Modern Era: Property-Matched Decoys (e.g., DUD) [13] | Decoys are selected to be physicochemically similar to known actives (e.g., matching molecular weight, logP) but structurally dissimilar to avoid true activity. | Dramatically reduces "artificial enrichment" bias; became the gold standard for VS method evaluation. | The "false negative" risk remains, as some decoys might be active; the selection is based on putative, not confirmed, inactivity [13]. |

| Current Trends: Experimentally Validated & Specialized Decoys | Use of confirmed non-binders from high-throughput screening (HTS), such as Dark Chemical Matter (DCM), or decoys generated from docking poses [27]. | Provides high-confidence negative data; data augmentation from docking expands coverage of binding modes. | Availability of experimental non-binders is limited; docking-based decoys may inherit biases from the docking algorithm itself [27]. |

Comparative Analysis of Contemporary Approaches

Recent studies directly compare these modern strategies. Research on machine-learning scoring functions has shown that models trained with random selections from the ZINC15 database or with DCM compounds can closely mimic the performance of models trained with true non-binders, presenting viable alternatives when specific inactivity data is absent [27]. Furthermore, utilizing diverse conformations from docking results for data augmentation has been established as a valid strategy for expanding the representation of negative interactions in a dataset [27].

Table 2: Comparison of Contemporary Decoy Sources for Pharmacophore Model Validation

| Decoy Source / Strategy | Key Implementation Example | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Customized Property-Matching (e.g., DUD/E) | Decoys are matched to actives on molecular weight, logP, and other descriptors, while minimizing topological similarity [13]. | Greatly reduces physicochemical bias; considered a robust benchmark. | Decoy generation can be computationally intensive; potential for latent biases. |

| Database of Useful Decoys: Enhanced (DUDe) | Used to generate a set of decoys for XIAP antagonists, providing 5199 decoys for 10 known active compounds [12]. | Publicly available tool/generator; improves upon DUD by matching a wider array of physicochemical properties. | As with DUD, decoys are putative inactives, not experimentally confirmed. |

| Dark Chemical Matter (DCM) | Recurrent non-binders from HTS campaigns are used as high-quality decoys to train target-specific machine learning models [27]. | Composed of compounds confirmed to be inactive in multiple assays; high reliability. | Limited availability and diversity; may not cover all relevant chemical spaces. |

| Docking Conformation Augmentation | Using multiple, likely incorrect, binding poses of active molecules from docking simulations to represent non-binding interactions [27]. | Explores a wide range of non-productive binding modes; good for data augmentation. | Quality is dependent on the docking program and scoring function used. |

Experimental Protocols for Decoy Set Preparation and Validation

Protocol 1: Preparation of a Property-Matched Decoy Set using a DUDe-like Approach

This protocol outlines the creation of a decoy set designed to minimize physicochemical bias [13] [12].

- Active Compound Curation: A set of known active compounds for the target protein is collected from reliable bioactivity databases such as ChEMBL. Activity is typically defined by an experimental IC50 or Ki value below a specific cutoff (e.g., 10 µM) [27].

- Descriptor Calculation: Key physicochemical properties are calculated for every active molecule. These typically include:

- Molecular weight (MW)

- Calculated octanol-water partition coefficient (clogP)

- Number of hydrogen bond donors (HBD)

- Number of hydrogen bond acceptors (HBA)

- Number of rotatable bonds (RB)

- Topological polar surface area (TPSA)

- Decoy Selection from a Database: A large database of purchasable compounds (e.g., ZINC) is filtered for drug-like molecules. For each active compound, a set of decoys (typically 36-100x the number of actives) is selected from the filtered database. The selection algorithm ensures that the decoys' properties fall within a close range (e.g., ±1 or a specified variance) of the values for the active molecule [13].

- Dissimilarity Filtering: A critical final step is to ensure that the selected decoys are structurally dissimilar to the active to reduce the chance of including an undetected active compound. This is often done using molecular fingerprint-based similarity metrics (e.g., Tanimoto coefficient on ECFP4 fingerprints), with a low similarity threshold [13].

Protocol 2: Validation of the Pharmacophore Model using the Prepared Set

Once the validation set (actives + decoys) is prepared, it is used to validate the pharmacophore model's screening power [7] [12].

- Database Screening: The complete validation set is screened against the pharmacophore model. The output is a list of compounds that match the pharmacophore hypothesis, ranked according to the model's scoring or fit value.

- Performance Calculation:

- Enrichment Factor (EF): The EF measures how much more likely the model is to find an active compound compared to a random selection. It is calculated as follows:

- EF = (Hit~actives~ / N~actives~) / (Hit~total~ / N~total~)

- Where Hit~actives~ is the number of active compounds retrieved, N~actives~ is the total number of actives in the set, Hit~total~ is the total number of compounds retrieved (hits), and N~total~ is the total number of compounds in the validation set. The EF at the top 1% of the screened database (EF~1%~) is a commonly reported metric [12].

- Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) Curve & AUC: The ROC curve plots the true positive rate (sensitivity) against the false positive rate (1-specificity) across all possible ranking thresholds. The Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC) provides a single measure of the model's overall ability to discriminate between active and decoy compounds. An AUC of 1.0 represents perfect discrimination, while 0.5 represents a random classifier [7] [12].

- Enrichment Factor (EF): The EF measures how much more likely the model is to find an active compound compared to a random selection. It is calculated as follows:

- Interpretation: A robust pharmacophore model will show high early enrichment (a high EF~1%~) and a high AUC value (e.g., >0.7-0.8), indicating its utility for prospective virtual screening.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Validation Set Preparation

| Resource / Reagent | Function in Validation | Relevance to Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| ChEMBL Database | A manually curated database of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties. Serves as the primary source for experimentally validated active compounds [27] [7]. | Used in Protocol 1, Step 1 for curating the set of known actives for a specific target. |

| ZINC Database | A freely available database of commercially available compounds for virtual screening. Serves as the primary source for decoy compounds [27] [7] [12]. | Used in Protocol 1, Step 3 as the pool from which property-matched decoys are selected. |

| DUDe (Database of Useful Decoys: Enhanced) | A publicly available tool and database that provides pre-generated, property-matched decoys for a wide range of targets, streamlining the validation set creation process [12]. | An alternative to manually executing Protocol 1; provides ready-to-use decoy sets for common targets. |

| Molecular Fingerprints (e.g., ECFP4, Morgan) | A method to encode the structure of a molecule into a bit string. Used for calculating molecular similarity. | Used in Protocol 1, Step 4 for ensuring structural dissimilarity between actives and decoys. |

| Dark Chemical Matter (DCM) | Collections of compounds that have shown no activity across numerous HTS assays. Represent a source of high-confidence true negative compounds [27]. | Used as a premium source of decoys in advanced implementations, as discussed in comparative strategies. |

Workflow Diagram for Validation Set Preparation and Model Validation

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow integrating the decoy preparation and pharmacophore validation protocols.

Virtual screening (VS) has become an indispensable computational tool in modern drug discovery, enabling researchers to rapidly identify potential lead compounds from vast chemical libraries. When employing a pharmacophore model—an abstract representation of the steric and electronic features necessary for molecular recognition—the virtual screening process becomes a powerful method for retrieving compounds that share a specific biological activity despite potential structural dissimilarity. The core objective of executing virtual screening with a pharmacophore model is to efficiently sift through millions of compounds to find those that match the essential pharmacophoric pattern, thereby significantly increasing the likelihood of identifying novel bioactive molecules. The success of this exercise is most accurately measured by the enrichment factor (EF), a critical metric that quantifies how effectively the screening prioritizes active compounds over inactive ones in a database. A thorough understanding of the pharmacophore-based virtual screening (PBVS) workflow, its performance relative to other methods, and its optimal application is fundamental for researchers aiming to accelerate early-stage drug discovery campaigns.

Performance Benchmark: PBVS vs. Docking-Based Virtual Screening

A critical question for practitioners is how pharmacophore-based screening compares to the other predominant virtual screening method: docking-based virtual screening (DBVS). A comprehensive benchmark study against eight structurally diverse protein targets provides compelling experimental data, demonstrating that PBVS consistently outperforms DBVS in many scenarios [11] [5].

The study utilized two testing datasets and measured performance using enrichment Factor (EF) and hit rate. The results were clear: in 14 out of 16 virtual screening sets, PBVS achieved higher enrichment factors than DBVS methods employing three different docking programs (DOCK, GOLD, Glide) [11] [5]. The average hit rates over the eight targets at the top 2% and 5% of the ranked database were also "much higher" for PBVS [11]. This superior performance is attributed to pharmacophore models' ability to capture essential, ligand-based interaction patterns, making them robust tools for initial database filtering.

Table 1: Benchmark Performance of PBVS vs. DBVS Across Eight Targets [11] [5]

| Virtual Screening Method | Programs Used | Enrichment Factor (EF) Superiority (out of 16 tests) | Average Hit Rate (Top 2% & 5% of Database) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmacophore-Based (PBVS) | Catalyst | 14 cases higher | Much higher |

| Docking-Based (DBVS) | DOCK, GOLD, Glide | 2 cases higher | Lower |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for PBVS

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling and Screening

This protocol is used when a 3D structure of the target protein, often with a bound ligand, is available.