Enhancing Pharmacophore Models: Strategies for Superior Specificity and Selectivity in Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on advancing pharmacophore model specificity and selectivity. It covers foundational principles, explores advanced methodological approaches including structure-based and ligand-based modeling, and details optimization techniques such as exclusion volumes and machine-learned informacophores. The content further addresses rigorous validation protocols using statistical metrics like ROC-AUC and EF, alongside comparative analysis of software tools. By synthesizing these strategies, the article serves as a roadmap for creating highly predictive pharmacophore models that improve virtual screening success rates and accelerate the identification of novel therapeutic candidates.

Enhancing Pharmacophore Models: Strategies for Superior Specificity and Selectivity in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on advancing pharmacophore model specificity and selectivity. It covers foundational principles, explores advanced methodological approaches including structure-based and ligand-based modeling, and details optimization techniques such as exclusion volumes and machine-learned informacophores. The content further addresses rigorous validation protocols using statistical metrics like ROC-AUC and EF, alongside comparative analysis of software tools. By synthesizing these strategies, the article serves as a roadmap for creating highly predictive pharmacophore models that improve virtual screening success rates and accelerate the identification of novel therapeutic candidates.

Core Principles: Defining Specificity and Selectivity in Pharmacophore Modeling

Technical Support Center

This support center provides assistance for researchers developing and validating pharmacophore models, with a focus on enhancing model specificity and selectivity to reduce late-stage attrition in drug discovery.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between the classic IUPAC pharmacophore definition and the "informacophore" concept? A1: The IUPAC definition describes a pharmacophore as "an ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target and to trigger (or block) its biological response." It is a qualitative, feature-based model. The informacophore is a modern extension that integrates quantitative data (e.g., Ki, IC50, pharmacokinetic properties) and structural dynamics (e.g., molecular fingerprints, conformational entropy) directly into the pharmacophore definition, transforming it into a data-rich, predictive model for specific biological outcomes.

Q2: Why does my pharmacophore model, built from a highly active ligand, retrieve many inactive compounds (high false positives) in a virtual screen? A2: This is a common issue related to poor specificity. The model may be too generic. Key troubleshooting steps include:

- Feature Redundancy: The model may contain unnecessary features that are not critical for binding, making it too permissive.

- Lack of Excluded Volumes: Without excluded volumes, the model cannot sterically discriminate against compounds that have the right features but also have bulky substituents that cause clashes with the target protein.

- Inadequate Conformational Sampling: The model was generated from a single, low-energy conformation. It may not represent the bioactive conformation or the conformational constraints of active ligands.

Q3: How can I improve the selectivity of my pharmacophore model to distinguish between closely related protein subtypes (e.g., Kinase A vs. Kinase B)? A3: Enhancing selectivity requires a comparative approach:

- Multi-Target Pharmacophores: Generate separate models for each subtype (A and B) using known selective ligands.

- Feature Comparison: Identify the unique, discriminating features in each model. A feature present in the Kinase A model but absent in the Kinase B model is a potential selectivity feature.

- Incorporate Structure-Based Data: If crystal structures are available, use them to place excluded volumes in regions where the protein structures differ. This forces the model to favor compounds that fit only the intended subtype's binding pocket.

Q4: My model performs well on a training set but fails to predict the activity of new compounds. What could be wrong? A4: This indicates overfitting. The model has memorized the training set instead of learning the general rules for binding.

- Solution: Apply stricter feature tolerances, reduce the number of features to the absolute minimum essential set, and validate the model using an external test set of compounds that were not used in any phase of model generation.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Handling Tautomeric and Protonation States in Feature Generation

- Problem: Incorrect assignment of ligand tautomeric or protonation states leads to misidentification of hydrogen bond donors and acceptors, corrupting the pharmacophore model.

- Diagnosis: The model fails to retrieve known active compounds that have a different protonation state at physiological pH.

- Resolution:

- Pre-processing: Before model generation, pre-process all ligand structures using a tool like LigPrep (Schrödinger) or MOE's Wash module to generate probable states at a defined pH (e.g., 7.4 ± 0.5).

- Multiple Models: Consider generating multiple pharmacophore hypotheses, each based on a different dominant protonation/tautomeric state of the reference ligand.

- Validation: Test all hypotheses against a diverse validation set. The correct hypothesis will have the highest enrichment factor for active compounds.

Issue: Optimizing Pharmacophore Query Parameters for Virtual Screening

- Problem: The virtual screening workflow returns too few hits (overly restrictive) or too many hits with low potency (overly permissive).

- Diagnosis: The inter-feature distance tolerances and weight settings are not optimized.

- Resolution Protocol:

- Define a Decoy Set: Create a database containing known active compounds and inactive/decoy molecules.

- Systematic Variation: Run the virtual screen multiple times, varying the distance tolerance (e.g., from 1.0 Ã… to 2.5 Ã…) and feature weights.

- Quantitative Assessment: For each run, calculate the enrichment factor (EF) and the area under the ROC curve (AUC-ROC).

- Select Optimal Parameters: Choose the parameter set that maximizes both EF and AUC-ROC.

Table 1: Impact of Distance Tolerance on Screening Performance

| Distance Tolerance (Ã…) | Hits Retrieved | % of Known Actives Found | Enrichment Factor (EF1%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.0 | 150 | 25% | 5.2 |

| 1.5 | 450 | 65% | 12.1 |

| 2.0 | 1,200 | 85% | 8.9 |

| 2.5 | 3,500 | 90% | 3.1 |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Generating a Structure-Based Pharmacophore Model from a Protein-Ligand Complex

Objective: To create a high-specificity pharmacophore model using the 3D structure of a target protein bound with a native ligand or inhibitor.

Methodology:

- Structure Preparation:

- Obtain the PDB file of the protein-ligand complex.

- Using Maestro's Protein Preparation Wizard (Schrödinger) or MOE's QuickPrep, add hydrogens, assign bond orders, correct missing residues/side chains, and optimize hydrogen bonding networks.

- Perform a constrained energy minimization to relieve steric clashes.

- Ligand Interaction Analysis:

- Analyze the prepared complex using tools like MOE's Ligand Interactions or Maestro's Contact Analysis.

- Identify key interactions: hydrogen bonds (donors/acceptors), hydrophobic contacts, aromatic stacking, and ionic interactions.

- Pharmacophore Feature Generation:

- Use the interaction map to define pharmacophore features directly from the ligand atoms involved in critical interactions with the protein.

- Crucially, add Excluded Volumes: Place excluded volume spheres on protein atoms lining the binding pocket that are not in contact with the ligand. This defines the steric boundaries.

- Model Refinement:

- Adjust the tolerance radii of each feature based on the observed flexibility in similar crystal structures.

- Validate the model by screening a small set of known actives and decoys.

Protocol 2: Validating Pharmacophore Specificity and Selectivity

Objective: To quantitatively assess the ability of a pharmacophore model to correctly identify target-specific active compounds and reject inactives and off-target compounds.

Methodology:

- Curation of Validation Sets:

- Set A (Active): 20-50 confirmed active compounds for the primary target.

- Set B (Inactive/Decoy): 1000+ molecules with similar physicochemical properties but confirmed inactivity against the primary target.

- Set C (Selectivity Challenge): Known active compounds for a closely related off-target (e.g., a different kinase isoform).

- Virtual Screening Execution:

- Screen all three sets (A, B, C) against the pharmacophore model using a flexible search algorithm.

- Record the hit rates for each set.

- Data Analysis and Metric Calculation:

- Sensitivity: (Actives in Hit List / Total Actives in Set A)

- Specificity: (Inactives Correctly Rejected / Total Inactives in Set B) or use Precision: (True Positives / (True Positives + False Positives))

- Selectivity Index: (Hit Rate for Set A / Hit Rate for Set C). A value >1 indicates selectivity for the primary target.

Table 2: Example Validation Results for a Kinase Inhibitor Pharmacophore

| Validation Set | Total Compounds | Hits Retrieved | Hit Rate | Key Metric Calculated |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Set A (Actives) | 30 | 27 | 90.0% | Sensitivity = 90.0% |

| Set B (Decoys) | 1000 | 50 | 5.0% | Precision = 27/(27+50) = 35.1% |

| Set C (Off-target Actives) | 25 | 5 | 20.0% | Selectivity Index = 90.0/20.0 = 4.5 |

Visualization

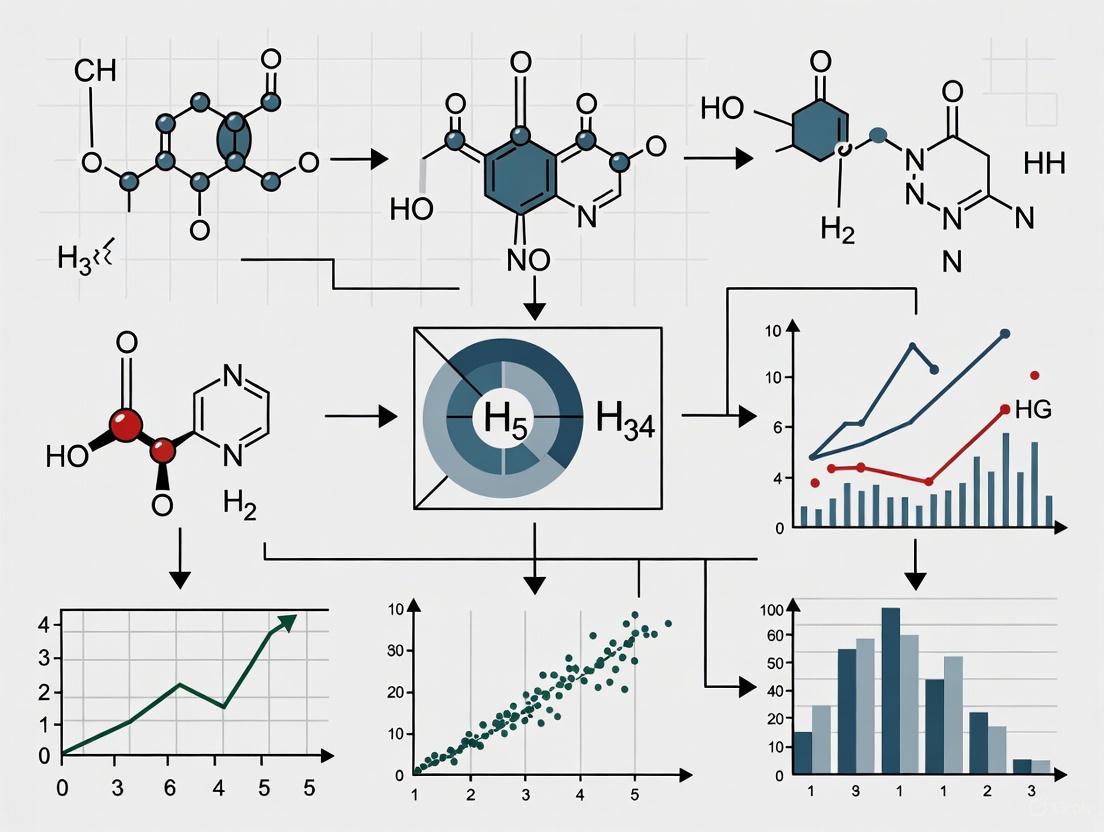

Diagram 1: Pharmacophore to Informacophore Evolution

Diagram 2: Pharmacophore Model Validation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Pharmacophore Modeling

| Item/Software | Function & Explanation |

|---|---|

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Source of 3D protein-ligand complex structures for structure-based pharmacophore generation. |

| LigandScout | Specialized software for automatically creating structure- and ligand-based pharmacophore models and performing virtual screening. |

| Schrödinger Suite | Integrated platform for protein preparation (Maestro), pharmacophore development (Phase), and virtual screening. |

| MOE (Molecular Operating Environment) | A comprehensive software suite for molecular modeling, simulation, and pharmacophore module (Pharmacophore Query Editor). |

| Conformational Database | A pre-computed database of low-energy conformers for screening compounds (e.g., generated with OMEGA). Essential for flexible screening. |

| Decoy Finder | Tools like DUD-E or Directory of Useful Decoys are used to generate property-matched decoy molecules for rigorous model validation. |

| CHEMBL / PubChem | Public databases of bioactive molecules with associated assay data, used for building training and test sets for model generation and validation. |

| Antitumor agent-101 | Antitumor agent-101, MF:C26H38N6O3, MW:482.6 g/mol |

| Bcl-2-IN-17 | Bcl-2-IN-17, MF:C29H21N3O3, MW:459.5 g/mol |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Q1: My pharmacophore model is generating too many false positives in virtual screening. How can I improve its specificity? A: This often occurs due to an oversimplified spatial definition of features.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Check Feature Tolerances: Reduce the angular and distance tolerances for hydrogen bond donors/acceptors and ionizable groups. Overly large tolerances create excessively permissive search volumes.

- Refine Excluded Volumes: Add excluded volumes based on the 3D structure of a known inactive compound. This defines regions where atoms cannot be placed, preventing the model from matching decoys with steric clashes.

- Re-evaluate Ionizable Groups: For ionizable groups, consider the protonation state at physiological pH (7.4). Define them as either charged or neutral consistently, as misassignment can drastically alter spatial matching.

Q2: How do I accurately define a hydrophobic feature, and why is my model missing active compounds with clear hydrophobic regions? A: Hydrophobic features are often ambiguously placed.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Use Surface Descriptors: Instead of placing points on atom centers, use computational methods to map the molecular hydrophobic surface (e.g., using MLP, LogP-based projections). This provides a more realistic spatial definition.

- Cluster Hydrophobic Atoms: If using atom-centered points, ensure all contiguous hydrophobic atoms (e.g., in an alkyl chain) are clustered into a single, larger feature with a defined centroid, rather than multiple small points.

- Verify Probe Parameters: Check the parameters of the computational probe used to detect hydrophobicity. An overly small probe radius may fail to detect broader hydrophobic patches.

Q3: During model generation, what is the optimal way to handle tautomers and protomers for ionizable groups? A: Failing to account for multiple states is a common source of poor selectivity.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Generate Multiple Conformations: For each training set molecule, generate a set of low-energy conformations that include all relevant tautomeric and protonation states at pH 7.4.

- Use a Common Reference State: Align molecules based on a shared, rigid scaffold if available, rather than flexible ionizable groups.

- Implement Dynamic Features: Some advanced pharmacophore modeling software allows features like "ionizable" which can match both neutral and charged forms. Utilize these over static "positive/negative ion" features when chemical variability is expected.

Q4: The spatial arrangement of my model is too rigid and fails to capture key ligand-receptor flexibility. How can I introduce necessary flexibility? A: This is a limitation of rigid 3D pharmacophore searching.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Introduce Tolerances: Systematically increase distance and angle tolerances based on the observed variability in your aligned training set.

- Utilize Multiple Conformer Models: Create not one, but several distinct pharmacophore models, each based on a different low-energy conformation of a highly active ligand. Screen against this ensemble of models.

- Switch to Ligand-Based Screening: If the receptor structure is unknown, consider using a shape-based or ROCS (Rapid Overlay of Chemical Structures) approach alongside the pharmacophore to account for overall molecular volume and flexibility.

Table 1: Typical Energy Ranges and Geometries for Key Pharmacophore Interactions.

| Interaction Type | Optimal Distance (Å) | Optimal Angle (°) | Typical Energy (kcal/mol) | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Bond (Strong) | 2.7 - 3.1 | 150 - 180 (D-H-A) | -3 to -8 | Distance is H-Acceptor. Angles are critical for strength. |

| Hydrogen Bond (Weak) | 3.1 - 3.5 | 130 - 150 (D-H-A) | -1 to -3 | More forgiving angular geometry. |

| Ionic Interaction | 2.8 - 3.5 | N/A | -5 to -10+ | Highly dependent on dielectric constant of the environment. |

| Hydrophobic Contact | 3.5 - 5.0 | N/A | -0.5 to -1.5 per Ų | Entropically driven. Strength scales with buried surface area. |

Table 2: Common pKa Ranges for Ionizable Groups in Drug-like Molecules.

| Ionizable Group | Example | Typical pKa Range | Predominant State at pH 7.4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carboxylic Acid | Acetic Acid | 3.0 - 5.0 | Deprotonated (Anion) |

| Aromatic Amine | Aniline | 4.0 - 6.0 | Mixed / Context Dependent |

| Alkyl Amine | Piperidine | 9.0 - 11.0 | Protonated (Cation) |

| Pyridine | Nicotine | 4.5 - 5.5 | Mostly Protonated (Cation) |

| Guanidino | Arginine | 12.0 - 13.5 | Protonated (Cation) |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Systematic Pharmacophore Model Generation with Exclusion Volumes

Objective: To create a high-specificity pharmacophore model from a set of aligned active molecules, incorporating excluded volumes to reduce false positives.

Methodology:

- Data Curation: Collect a set of 15-30 structurally diverse molecules with known high activity against the target. Include 2-3 known inactive compounds for negative design.

- Conformational Analysis: Generate a representative set of low-energy conformers for each molecule using software like OMEGA or CONFGEN, ensuring coverage of relevant torsional space.

- Molecular Alignment: Align all active molecules using a common rigid scaffold or a field-based alignment method (e.g., ROCS, Phase).

- Feature Annotation: Using a tool like LigandScout or MOE, automatically identify and map conserved features: Hydrogen Bond Donor (HBD), Hydrogen Bond Acceptor (HBA), Hydrophobic (H), Positive Ionizable (PI), Negative Ionizable (NI).

- Excluded Volume Generation: Based on the aligned active set, generate excluded volumes (using van der Waals surfaces) to define sterically forbidden regions. Refine by ensuring known inactive compounds clash with these volumes.

- Model Validation: Screen the model against a large, diverse decoy set and a small set of known actives. Calculate enrichment factors (EF) and area under the ROC curve (AUC) to quantify performance.

Protocol 2: pKa Determination and Protonation State Assignment for Ionizable Groups

Objective: To experimentally determine the pKa of a lead compound for accurate protonation state assignment in pharmacophore modeling.

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a 0.1-1.0 mM solution of the compound in a suitable buffer (e.g., phosphate or carbonate). Ensure the ionic strength is consistent.

- Potentiometric Titration:

- Use an automated titrator equipped with a pH electrode.

- Titrate the compound solution from pH 2 to 12 using a standard KOH or HCl solution.

- Record the pH after each addition once equilibrium is reached.

- Data Analysis:

- Plot the titration curve (pH vs. volume of titrant).

- Use software (e.g., RefinementPro) to fit the data and calculate the macroscopic pKa values.

- Protonation State Assignment: At the target pH (e.g., 7.4), calculate the fractional population of each microspecies using the Henderson-Hasselbalch equation. The predominant species should be used for model generation.

Diagrams

Pharmacophore Modeling Workflow

Ligand-Receptor Interaction Map

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Software for Pharmacophore Modeling.

| Item | Function/Benefit |

|---|---|

| LigandScout | Software for automatic structure- and ligand-based pharmacophore model creation, visualization, and virtual screening. |

| Schrödinger Suite (Phase) | Integrated computational platform offering robust tools for pharmacophore perception, development, and screening within a drug discovery workflow. |

| OMEGA (OpenEye) | High-performance conformer generator essential for creating representative 3D conformational ensembles for model building. |

| CHEMBL/DrugBank | Public databases providing curated bioactivity data and structures for active and inactive compounds, crucial for training and validation sets. |

| MOE (Molecular Operating Environment) | Comprehensive software suite with strong pharmacophore modeling, QSAR, and molecular simulation capabilities. |

| pKa Prediction Tools (e.g., MoKa, Epik) | Software for predicting microscopic pKa values to accurately assign protonation states of ionizable groups under physiological conditions. |

| DUD-E Library | A database of useful decoys for benchmarking virtual screening methods, enabling quantitative model validation. |

| Csf1R-IN-21 | Csf1R-IN-21, MF:C24H20F3N5O3, MW:483.4 g/mol |

| Tubulin inhibitor 34 | Tubulin inhibitor 34, MF:C21H22N4O3S, MW:410.5 g/mol |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between structure-based and ligand-based pharmacophore generation? A1: Structure-based pharmacophore generation uses the 3D structure of a protein target, often with a bound ligand, to identify key interaction sites (e.g., hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic patches). Ligand-based pharmacophore generation derives common chemical features from a set of known active molecules, in the absence of the protein structure, by aligning them and extracting shared features critical for biological activity.

Q2: My structure-based pharmacophore model is too stringent and fails to retrieve known actives from a database. What could be wrong? A2: This is a common issue of over-specificity.

- Cause 1: The model may be built from a single, rigid protein conformation. Protein flexibility is often key to ligand binding.

- Solution: Generate multiple pharmacophore models from different protein snapshots (e.g., from molecular dynamics simulations) or use an ensemble of receptor structures.

- Cause 2: The excluded volume spheres are too restrictive.

- Solution: Reduce the number or radius of excluded volume spheres, or remove them entirely for the initial screening phase to allow for more ligand conformational flexibility.

Q3: My ligand-based pharmacophore model retrieves many inactive compounds (high false positives). How can I improve its selectivity? A3: This indicates a lack of discriminatory power.

- Cause 1: The training set of active compounds is too diverse or contains weak/partial agonists.

- Solution: Curate a more homogeneous set of highly active ligands. Incorporate known inactive compounds to define "anti-pharmacophore" features that should be absent in true actives.

- Cause 2: The conformational space of the ligands is not adequately sampled during alignment.

- Solution: Increase the energy threshold for conformer generation to ensure a broader coverage of potential low-energy states.

Q4: Which approach is more suitable for a target with no known 3D structure but a large set of known active ligands? A4: Ligand-based pharmacophore generation is the clear choice in this scenario. It leverages the chemical information encoded in the known actives to create a model for virtual screening, even without any structural data on the target protein.

Q5: Can these approaches be combined? A5: Yes, a hybrid approach often yields superior results. A structure-based model can provide a solid foundational hypothesis, which can then be refined and validated using the chemical information from known active and inactive ligands, improving the model's real-world predictive power.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Structure-Based Model Has Poor Enrichment in Virtual Screening

| Step | Checkpoint | Action |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Protein Preparation | Ensure protonation states of key residues (e.g., His, Asp, Glu) are correct for the biological pH. |

| 2 | Ligand Interaction Analysis | Verify the automated feature detection. Manually curate features to remove redundant or non-essential ones. |

| 3 | Excluded Volumes | Temporarily disable excluded volumes. If enrichment improves, reintroduce them selectively only in the protein's core steric barriers. |

| 4 | Model Complexity | If the model has >6 features, try creating simpler sub-models with a subset of critical features and screen with them in parallel. |

Problem: Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Model Fails to Generate a Meaningful Alignment

| Step | Checkpoint | Action |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Training Set | Check if the molecules are truly congeneric. Remove outliers or split the set into different activity classes to build separate models. |

| 2 | Feature Definition | Re-evaluate the chemical features used. Overly specific features (e.g., precise aromatic ring vectors) can prevent alignment. Use more generic features (e.g., hydrophobic group) initially. |

| 3 | Conformer Generation | Increase the maximum number of conformers and the energy cutoff (e.g., from 10 kcal/mol to 20 kcal/mol) to ensure the active conformation is represented. |

| 4 | Algorithm Parameters | Adjust the "maximum omit feature" parameter. Allowing the model to ignore one feature for some ligands can lead to a better overall consensus alignment. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Structure-Based Pharmacophore Generation using a Protein-Ligand Complex

- Protein Preparation: Obtain the 3D structure from the PDB (e.g., 3ABC). In a tool like Maestro's Protein Preparation Wizard, add hydrogens, assign bond orders, correct missing residues, and optimize H-bond networks.

- Ligand Interaction Analysis: Analyze the binding site. Manually identify and map all non-covalent interactions (H-bonds, ionic, π-π stacking, hydrophobic contacts) between the protein and the co-crystallized ligand.

- Feature Generation: Translate the spatial information of the interactions into pharmacophore features. For example, a hydrogen bond between a ligand carbonyl and a protein backbone NH becomes a Hydrogen Bond Acceptor vector feature.

- Excluded Volumes: Add excluded volume spheres around protein atoms lining the binding pocket to define steric constraints.

- Model Validation: Screen a small decoy set containing known actives and inactives. Calculate the enrichment factor (EF) and hit rate to validate the model's discriminative power.

Protocol 2: Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Generation using Common Feature Approach

- Ligand Set Curation: Compile a set of 20-30 diverse, highly active molecules with confirmed biological activity. Include a few known inactives if available.

- Conformational Analysis: For each ligand, generate a representative set of low-energy conformers using software like OMEGA or CONFGEN. Use a root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) cutoff of 0.8-1.0 Ã… and an energy window of 10-20 kcal/mol.

- Feature Assignment: Define a common set of chemical features (e.g., Hydrogen Bond Acceptor, Hydrogen Bond Donor, Hydrophobic, Positive Ionizable) for all molecules.

- Hypothesis Generation: Use an algorithm like HipHop (in Discovery Studio) or PHASE to find the optimal alignment of the conformers that maximizes the overlap of common features. The algorithm will generate multiple hypotheses.

- Hypothesis Selection: Rank the generated hypotheses based on their selectivity score (a measure of how well they explain the actives vs. inactives) and visual inspection of the alignments.

Quantitative Data Comparison

Table 1: Characteristic Comparison of Pharmacophore Modeling Approaches

| Parameter | Structure-Based | Ligand-Based |

|---|---|---|

| Prerequisite | 3D Protein Structure | Set of Active Ligands |

| Key Strength | Directly encodes target constraints; good for selectivity analysis. | Does not require a protein structure; captures essential ligand features. |

| Key Limitation | Dependent on protein structure quality and a single conformation. | Limited by the diversity and quality of the ligand training set. |

| Typical Enrichment Factor (EF1%)* | 15-35 | 10-25 |

| Best Use Case | Target with a known structure; scaffold hopping from a known binder. | Target with no known structure; SAR analysis of a congeneric series. |

| Computational Cost | Low to Moderate | Moderate to High (due to conformer generation) |

*EF1% is a common metric showing how many more actives are found in the top 1% of a screened database compared to a random model.

Visualization: Workflow Diagrams

Title: Structure-Based Workflow

Title: Ligand-Based Workflow

Title: Hybrid Model Creation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Pharmacophore Modeling |

|---|---|

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | A repository for 3D structural data of proteins and nucleic acids, serving as the primary input for structure-based approaches. |

| Conformer Generation Algorithm (e.g., OMEGA) | Software that generates multiple low-energy 3D structures for a single molecule, which is critical for capturing the bioactive conformation in ligand-based modeling. |

| Pharmacophore Modeling Software (e.g., MOE, Discovery Studio, LigandScout) | Integrated platforms that provide the tools for feature mapping, hypothesis generation, model validation, and virtual screening. |

| Compound Database (e.g., ZINC, ChEMBL) | Large, commercially or publicly available collections of molecules used for virtual screening to identify novel hits using the validated pharmacophore model. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation Software (e.g., GROMACS, Desmond) | Used to generate an ensemble of protein conformations, providing a more dynamic and realistic basis for structure-based pharmacophore model generation. |

| Influenza virus-IN-8 | Influenza virus-IN-8, MF:C21H16BrN5O, MW:434.3 g/mol |

Advanced Techniques for Building High-Fidelity Pharmacophore Models

Fundamental Concepts & Workflow

What is a ligand-based pharmacophore model?

A pharmacophore is defined as "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or to block) its biological response" [1]. In ligand-based drug design (LBDD), this model is derived without target structure information by analyzing a set of known active compounds to identify their common chemical functionalities and spatial arrangement [1] [2] [3]. These features include hydrogen bond acceptors (HBAs), hydrogen bond donors (HBDs), hydrophobic areas (H), positively and negatively ionizable groups (PI/NI), and aromatic rings (AR) [1].

What is the general workflow for developing a ligand-based pharmacophore model?

The standard workflow involves several key stages, from data preparation to model application [1] [2] [3]. The following diagram illustrates this process and its role in the broader context of improving pharmacophore specificity and selectivity research.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Data Preparation & Conformational Analysis

Q: My pharmacophore model fails to identify active compounds from a test set. What might be wrong with my training set? A: This poor performance often originates from issues in the initial training set. Ensure your set includes 15-30 structurally diverse compounds that cover a wide activity range (ideally 4-5 orders of magnitude) [4] [2]. The compounds must share a common binding mode, and you should verify data quality by removing compounds with potential assay artifacts or questionable activity measurements [2] [5].

Q: How should I handle ligand conformational flexibility during model generation? A: Conformational flexibility is a core challenge in pharmacophore modeling [3]. Two primary strategies exist:

- Pre-enumerating method: Multiple conformations for each molecule are precomputed and stored in a database [3]. Use algorithms like Poling or energy minimization to ensure broad coverage of bioactive conformational space.

- On-the-fly method: Conformation analysis occurs during the pharmacophore modeling process itself, which can be more computationally intensive but may yield better results for specific targets [3].

Model Generation & Validation

Q: My pharmacophore model has too many features, making it too restrictive for virtual screening. How can I simplify it? A: Overly complex models with excessive features reduce the number of hits in virtual screening [1]. Use feature selection algorithms in software like Discovery Studio or Phase to identify the minimal essential features [6] [7]. Analyze protein-ligand interaction data (if available) to prioritize features interacting with key binding site residues [1]. Alternatively, generate multiple hypotheses and select the one with the best balance of simplicity and statistical significance in validation [2].

Q: What validation methods should I use to ensure my model is predictive? A: Proper validation is critical for model reliability, especially in selectivity research [4] [2]. Implement these essential validation steps:

Table 1: Essential Validation Methods for Pharmacophore Models

| Method Type | Specific Technique | Purpose | Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internal Validation | Fisher's randomization test | Verify model robustness | Significance level p < 0.05 |

| Internal Validation | Leave-one-out cross-validation | Assess predictive ability | Correlation coefficient > 0.6-0.7 |

| External Validation | Test set prediction | Evaluate performance on unknown compounds | Good correlation between predicted/actual activity |

| Decoy Screening | Screening against decoy sets (e.g., DUD-E) | Assess ability to distinguish actives from inactives | Sensitivity > 0.8, Specificity > 0.9 [8] |

| Application-based Validation | Virtual screening of known databases | Test utility in identifying diverse actives | Enrichment factor > 10-20 |

Selectivity & Specificity Challenges

Q: How can I improve my model's selectivity for one target isoform over another? A: Achieving selectivity is a central challenge in pharmacophore research [5]. Incorporate known selective compounds into your training set, including both actives for the target and inactives for related off-targets [5]. Add exclusion volumes based on the binding site of non-target proteins to create "forbidden" spaces [7]. Consider developing separate models for different receptor subtypes, then compare them to identify selectivity-determining features [5].

Q: Can machine learning enhance pharmacophore model specificity? A: Yes, machine learning (ML) significantly improves specificity predictions [5]. ML algorithms like Extra Trees, Random Forest, and XGBoost can process large descriptor sets (Mordred, RDKit, ECFP fingerprints) to identify subtle patterns correlating with specificity [5]. These approaches are particularly valuable for predicting selective ligands for structurally similar targets like sigma receptor subtypes S1R and S2R [5]. The following diagram illustrates how ML integrates with traditional pharmacophore modeling to enhance selectivity prediction.

Experimental Protocols

Standard Protocol for Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

Protocol Title: Development and Validation of a Selective Pharmacophore Model Using Diverse Ligand Sets

Objective: To create a validated, selective pharmacophore model for virtual screening of novel therapeutic candidates.

Materials and Software Requirements: Table 2: Essential Research Reagents & Computational Tools

| Category | Specific Tools/Software | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Modeling Software | Discovery Studio (CATALYST) [7] [9], Phase [6], MOE [8] | Pharmacophore generation, hypothesis building, and screening |

| Conformational Analysis | ConfGen [6], Molecular dynamics [2] | Generate representative ligand conformations |

| Chemical Databases | ZINC [9], ChEMBL [5], PubChem [5], In-house libraries | Source compounds for training sets and virtual screening |

| Descriptor Calculation | RDKit [5], Mordred [5] | Calculate molecular descriptors for QSAR/ML models |

| Validation Tools | DUD-E decoy sets [8], External test sets [4] | Validate model specificity and predictive power |

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Training Set Compilation (1-2 days)

- Select 20-30 compounds with known high activity (IC50 or Ki < 50 nM for highly active targets) [8] [9] and structural diversity.

- Include selective and non-selective compounds if targeting specific isoforms [5].

- Curate structures: Standardize representations, remove salts, and verify stereochemistry.

Conformational Analysis (1 day)

Pharmacophore Generation (1-2 days)

- Use automated algorithms (e.g., HypoGen in Discovery Studio [9] or common feature approaches) to generate multiple hypotheses.

- Align compounds and extract common chemical features (HBA, HBD, hydrophobic, aromatic, ionizable).

- Select 5-10 top-ranked hypotheses based on statistical scores (correlation coefficient, cost analysis) [9].

Model Validation (2-3 days)

- Internal validation: Perform Fisher's randomization test (95% confidence level) and cross-validation (leave-one-out) [4].

- External validation: Use a test set of 10-15 compounds not included in training. Calculate correlation between predicted and experimental activities.

- Decoy screening: Validate against DUD-E decoy sets to determine sensitivity and specificity [8].

- Selectivity assessment: Screen against related off-targets to verify specificity.

Virtual Screening Application (Variable)

- Use validated model to screen large databases (ZINC, Enamine, internal collections) [6] [9].

- Apply drug-likeness filters (Lipinski's Rule of Five, Veber's rules) [10] [9].

- Apply SMART filtration and toxicity assessment [9].

- Select top 100-500 hits for further experimental testing or docking studies.

Troubleshooting Notes:

- If model fails validation (low statistical significance), expand training set diversity or revisit conformational analysis parameters.

- If model retrieves too many false positives in virtual screening, add exclusion volumes or refine feature definitions.

- For poor selectivity, incorporate inactive compounds for off-targets as negative examples in training.

Advanced Protocol: Integrating Machine Learning for Selectivity Prediction

Protocol Title: One-Step Multiclassification Workflow for Predicting Selective Ligands

Objective: To implement a machine learning approach for directly predicting activity and selectivity profiles of compounds against related targets.

Methodology Overview (based on sigma receptor case study [5]):

Data Curation and Labeling

- Collect bioactivity data for both target subtypes from public databases (ChEMBL, BindingDB) and in-house sources.

- Classify compounds into categories: "Selective for Target A," "Selective for Target B," "Nonselective," and "Nonbinders" based on activity thresholds (e.g., 100-fold difference for selectivity) [5].

Descriptor Calculation and Feature Selection

- Calculate 2D molecular descriptors (Mordred, RDKit) and fingerprints (ECFP4, ECFP6, MACCS Keys) [5].

- Apply feature selection techniques (recursive feature elimination, genetic algorithms) to reduce dimensionality.

Model Building and Validation

- Implement multiclassification ML algorithms (Extra Trees, Random Forest, XGBoost) using nested 5-fold cross-validation [5].

- Compare one-step multiclassification with two-step classification/regression workflows.

- Validate best-performing model on external test set using metrics like ROC-AUC, precision, recall, and F1-score [5].

Expected Outcomes: A robust predictive model capable of classifying novel compounds into appropriate selectivity categories, directly supporting specificity optimization in drug discovery projects.

Incorporating Exclusion Volumes to Sterically Define the Binding Site and Reduce False Positives

Technical Guide: Core Concepts and Implementation

What are exclusion volumes and what problem do they solve?

Exclusion volumes, also known as excluded volumes (XVOL), are spatial constraints incorporated into pharmacophore models to represent regions of the binding site that a ligand cannot sterically occupy [1] [11]. They are a critical tool for reducing false positive rates in virtual screening by accounting for the shape of the binding pocket.

The primary problem they address is the high rate of false positive hits generated by structure-based ligand screening. Traditional pharmacophore feature hypotheses predict activity based purely on the presence and arrangement of pharmacophoric features, leaving steric effects unaccounted for [12]. Without these volumes, a molecule might fit the pharmacophoric feature hypothesis perfectly but still fail to bind to the receptor due to steric clashes with the protein structure [13]. By penalizing molecules that occupy these forbidden regions, exclusion volumes provide a more selective model, leading to better enrichment rates in virtual screening [12].

Step-by-Step Protocol: Adding Exclusion Volumes to Your Pharmacophore Model

Method 1: Structure-Based Approach (Using a Protein-Ligand Complex)

This method is used when the 3D structure of the target receptor or a ligand-receptor complex is available [1] [11].

- Protein Preparation: Obtain the 3D structure of your target from a database like the RCSB Protein Data Bank. Prepare the structure by evaluating residue protonation states, adding hydrogen atoms (which are often absent in X-ray structures), and checking for missing residues or atoms [1].

- Binding Site Identification: Define the ligand-binding site. This can be done manually if the site is known from experimental data or by using bioinformatics tools like GRID or LUDI that inspect the protein surface for potential binding sites [1].

- Feature and Volume Generation: Use computational software to automatically derive both the pharmacophoric features (HBA, HBD, Hydrophobic, etc.) and the exclusion volumes from the 3D structure of the binding site. The software maps the steric boundaries of the pocket [1] [11].

- Model Refinement: The initial model may contain many features and volumes. Select only the exclusion volumes and pharmacophoric features that are essential for bioactivity. This can involve removing volumes that do not strongly contribute to the energy of binding or are not conserved across multiple structures [1].

Method 2: Ligand-Based Approach (Using the HypoGenRefine Algorithm)

This method is applied when the 3D structure of the protein target is unavailable, but you have a set of active ligands [12].

- Ligand Set Preparation: Compile a set of known active ligands that bind to the same site and in the same orientation.

- Automated Model Generation: Use an algorithm like HypoGenRefine in Catalyst software. The algorithm automatically generates a pharmacophore hypothesis based on the common features of the active ligands.

- Incorporation of Excluded Volumes: The HypoGenRefine algorithm automatically adds excluded volume features to the pharmacophore model based on the steric constraints inferred from the set of active molecules. These volumes represent regions not occupied by any active molecule, hence they are assumed to be sterically forbidden by the receptor [12].

- Validation: The refined model, which now accounts for steric effects, should be validated for its ability to discriminate between known active and inactive compounds, thereby reducing false positives [12].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My pharmacophore model with exclusion volumes is now too restrictive and filters out known active compounds. What should I do?

A: Overly restrictive models often result from exclusion volumes that are too large or too numerous. To troubleshoot:

- Adjust Volume Size: Systematically reduce the radius of exclusion volumes, especially those generated in regions of the binding site that may have some flexibility.

- Remove Low-Impact Volumes: Identify and remove exclusion volumes that are not critical for defining the core steric boundary. Focus on volumes that are conserved in multiple protein-ligand complexes if available.

- Validate with Decoys: Test your model's sensitivity (ability to find actives) and specificity (ability to reject inactives) using a dataset of known actives and decoys. Adjust the model until you achieve a good balance.

Q2: Can exclusion volumes be used for all types of molecular targets?

A: While beneficial, caution is needed for highly flexible targets. Exclusion volumes are typically derived from a single, static protein conformation (e.g., from an X-ray structure). If the binding site undergoes significant conformational changes upon ligand binding, the excluded volumes from one conformation might incorrectly penalize ligands that bind to a different protein conformation [14]. For flexible targets, consider using multiple pharmacophore models with different exclusion volume arrangements or employing advanced methods like Molecular Dynamics Pharmacophore models that account for protein flexibility [11].

Q3: How do exclusion volumes directly lead to a reduction in false positives?

A: False positives in virtual screening are often molecules that possess the necessary chemical features to bind but are sterically incompatible with the binding site. A study on CDK2 and human DHFR demonstrated that the addition of excluded volumes to pharmacophore models significantly improved their selectivity. By explicitly defining forbidden space, these models penalize and filter out molecules that would otherwise score well based on feature matching alone, leading to a more accurate and reliable virtual screening hit list [12].

Experimental Data and Performance

The following table summarizes key findings from studies that implemented exclusion volumes to improve pharmacophore model performance.

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of Exclusion Volumes on Virtual Screening

| Target Protein | Method | Key Performance Finding | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| CDK2 & human DHFR | HypoGenRefine algorithm with excluded volumes | Automated refinement provided a more selective model to reduce false positives and achieve a better enrichment rate. | [12] |

| HIV-1 Protease Flap Site | Free Energy Calculations (BEDAM/DDM) after docking | Analysis showed a primary reason for docking false positives was inadequate treatment of desolvation penalty for partially buried, unfulfilled polar groups—a steric and solvation issue that exclusion volumes can help mitigate. | [14] |

| General Practice | Structure-based Pharmacophore Modeling | Incorporation of exclusion volumes representing the binding site shape is crucial for obtaining high-quality models that discriminate between pocket binders and non-binders. | [13] [1] |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Incorporating Exclusion Volumes

| Tool / Reagent Name | Type/Function | Specific Application for Exclusion Volumes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| GRID | Software Program | A grid-based method that uses probe molecules to identify energetically favorable and unfavorable interaction points on the protein surface, helping to define steric boundaries. | [1] |

| LUDI | Software Program | Predicts potential interaction sites using knowledge-based rules and can also be used to characterize the geometry of the binding site for volume assignment. | [1] |

| Catalyst/HypoGenRefine | Algorithm | Automatically generates excluded volume features from a set of active ligands in the absence of a protein structure (ligand-based approach). | [12] |

| Exclusion Volumes (XVOL) | Pharmacophore Feature | The core steric feature type itself, represented as spheres or other 3D shapes in the model, indicating regions the ligand cannot occupy. | [1] [11] |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Structural Database | The primary source for experimentally-solved 3D structures of proteins and protein-ligand complexes, which serve as the essential input for structure-based exclusion volume definition. | [1] |

Experimental Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for incorporating exclusion volumes using both structure-based and ligand-based approaches, highlighting the role of exclusion volumes in reducing false positives.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary purpose of pharmacophore modeling in modern drug discovery? Pharmacophore modeling is a foundational technique in computer-aided drug design (CADD) that abstracts the essential steric and electronic features of a ligand responsible for its biological activity. It serves as a powerful template for virtual screening, enabling researchers to identify novel hit compounds from large chemical libraries by capturing the key interactions between a drug and its biological target. This approach is particularly valuable for enhancing the specificity and selectivity of drug candidates, as it allows researchers to focus on the critical molecular features required for binding, thereby reducing off-target effects [15] [16].

Q2: My pharmacophore model retrieves too many false positives during virtual screening. How can I improve its precision? A high rate of false positives often indicates that the pharmacophore model lacks sufficient constraints to distinguish true actives from inactive compounds. To improve precision, consider these strategies:

- Incorporate Excluded Volumes: Add excluded volume spheres to your model based on the 3D structure of the target protein's binding pocket. These spheres represent regions where atoms from a potential ligand would cause steric clashes, thereby filtering out molecules that do not fit the pocket's shape.

- Use Multiple Structures: Develop a shared feature pharmacophore by overlaying multiple active ligands bound to the same target. This consensus approach helps distill the most critical interaction features common across different chemotypes, reducing over-reliance on features specific to a single ligand.

- Refine with Inactives: If data is available, perform a virtual screen and analyze the top-ranking compounds that are known inactives. Identify features or spatial arrangements that are over-represented in these inactives and consider adding corresponding constraints to your model to exclude them [17].

Q3: What are the best practices for constructing a structure-based pharmacophore from a protein-ligand complex? Constructing a robust structure-based pharmacophore involves a meticulous process:

- Prepare the Structure: Obtain a high-resolution crystal structure of the protein-ligand complex (e.g., from the PDB). Carefully check and correct the ligand's structure, including bond orders, protonation states, and formal charges.

- Generate the Pharmacophore: Using software like LigandScout, automatically map interaction features (e.g., hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions, charged groups) between the ligand and the protein.

- Validate and Refine: Critically review the automatically generated features. Remove potential false positives and adjust feature tolerances based on the observed interaction geometry in the complex. This ensures the model accurately reflects the true binding mode [17].

Q4: How can I leverage pharmacophore models to design selective inhibitors for a specific protein isoform? Designing selective inhibitors is a key application of advanced pharmacophore modeling. The core strategy involves a comparative analysis of the binding sites across different isoforms:

- Construct Comparative Models: Generate structure-based pharmacophores for your target isoform and other closely related isoforms (e.g., PARP1 vs. PARP2).

- Identify Selectivity Features: Meticulously compare the models to pinpoint unique interaction features present in your target isoform but absent in the others. These could be a specific hydrogen bond acceptor in a distinct sub-pocket, a unique hydrophobic patch, or a charged interaction not available elsewhere.

- Screen for Selective Hits: Use the target-specific pharmacophore as a query for virtual screening. This will prioritize compounds that can engage the unique features of your target, thereby increasing the likelihood of achieving selectivity [18].

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Issues and Solutions in Pharmacophore Modeling

The following table summarizes frequent challenges encountered during pharmacophore model construction and virtual screening, along with recommended solutions.

| Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poor hit rate in virtual screening | Model is too general or lacks key steric constraints. | Incorporate excluded volume spheres from the protein binding site. Use a consensus model derived from multiple active compounds [17]. |

| Model fails to retrieve known active compounds | Model is too restrictive or contains incorrect features. | Re-evaluate the ligand-protein interactions in the original complex. Widen the spatial tolerances of existing features or re-generate the model with a different set of training ligands. |

| Low selectivity of retrieved hits | Model does not capture unique features of the target. | Perform a comparative analysis with off-target pharmacophores and add differentiating features to your model [18]. |

| Inconsistent results after model merging | Incorrect alignment of parent pharmacophores. | Ensure the parent models are accurately superimposed based on common chemical features or a shared reference framework before merging [17]. |

| Difficulty handling complex binding modes | Over-simplification of protein-ligand interactions. | Utilize advanced software capabilities that can model complex features like metal coordination, polyaromatic interactions, and solvent-mediated hydrogen bonds. |

Workflow for Enhancing Model Specificity and Selectivity

Achieving high specificity and selectivity is a multi-stage process that integrates computational and experimental data. The diagram below illustrates a robust workflow for tackling this challenge.

Advanced Protocol: Developing a Selective Inhibitor Pharmacophore Model

This detailed protocol outlines the steps for constructing a pharmacophore model aimed at discovering selective inhibitors, a critical task in modern drug discovery [18].

Objective: To create a structure-based pharmacophore model for a target protein (e.g., PARP1) that incorporates selective features to minimize cross-reactivity with a closely related off-target (e.g., PARP2).

Methodology:

Target and Off-Target Structure Preparation:

- Download high-quality crystal structures of PARP1 and PARP2 in complex with their respective ligands from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). If structures are unavailable, generate reliable homology models.

- Use a molecular modeling suite (e.g., MOE) to prepare the proteins: add hydrogen atoms, assign correct protonation states at biological pH, and perform a brief energy minimization to relieve any steric clashes.

Individual Pharmacophore Model Generation:

- For each complex (PARP1-ligand and PARP2-ligand), use LigandScout to automatically generate a detailed pharmacophore model.

- The software will map features like:

- Hydrogen Bond Donors (HBD)

- Hydrogen Bond Acceptors (HBA)

- Hydrophobic Interactions (H)

- Positive/Negative Ionizable Areas (PI/NI)

- Exclusion Volumes (XV)

- Manually curate these features to ensure they accurately represent the key interactions observed in the crystal structure.

Comparative Analysis for Selectivity:

- Superimpose the binding sites of PARP1 and PARP2 based on their protein structure alignment.

- Compare the two pharmacophore models to identify features unique to PARP1. For example, a specific hydrogen bond acceptor pattern in a sub-pocket that is geometrically different in PARP2.

- Document these "selectivity features."

Consensus Selective Pharmacophore Construction:

- In your pharmacophore modeling software (e.g., Phase), create a new model.

- Incorporate all the critical binding features from the PARP1 model.

- Crucially, add the identified "selectivity features" as mandatory constraints.

- Also, include excluded volumes from the PARP1 binding site that differ from PARP2 to sterically block compounds that might fit the off-target.

Model Validation and Virtual Screening:

- Validation: Test the model's ability to retrieve known PARP1 selective inhibitors from a decoy set of compounds, including known PARP2 binders. A good model will enrich the PARP1 actives and reject the PARP2 binders.

- Screening: Once validated, use the selective pharmacophore as a 3D query to screen large commercial or in-house compound databases to identify novel, selective hit candidates for PARP1.

This table lists key computational tools and data resources that are fundamental to pharmacophore modeling and selectivity research.

| Tool / Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| LigandScout | Software | Creates structure- and ligand-based pharmacophores, performs virtual screening, and analyzes binding interactions [17]. |

| AlphaFold | Database & Model | Provides highly accurate predicted protein structures for targets with no experimental 3D structure available, enabling structure-based design [15]. |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Database | A repository for experimentally determined 3D structures of proteins, nucleic acids, and complexes, serving as the primary source for structural data [17]. |

| ChEMBL | Database | A large-scale bioactivity database containing binding, functional, and ADMET information for drug-like molecules, useful for model validation [18]. |

| CrossDocked Dataset | Benchmark Dataset | A curated set of protein-ligand complexes used for training and benchmarking structure-based molecular generation models [18]. |

Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why does my pharmacophore model retrieve a high number of false positives during the screening of an ultra-large library?

- A: This is often a problem of model specificity. Your model may be too general, matching features common to many molecules, not just actives. To improve specificity, consider: 1) Incorporating excluded volumes to define steric constraints. 2) Refining feature definitions using data from known inactive compounds (negative design). 3) Increasing the required weight or specificity of chemical features (e.g., changing a general "Hydrogen Bond Acceptor" to a "Positively Ionizable" feature if justified).

Q2: My validated pharmacophore model performs well on a test set but fails to identify any novel hits in the ultra-large library. What could be wrong?

- A: This typically indicates a selectivity issue or a conformational sampling problem. The model might be over-fitted to the specific scaffold of your known actives. Ensure your screening protocol allows for sufficient ligand conformational flexibility. Also, verify that the chemical space of your ultra-large library is not biased away from your target's requirements; perform a chemical space analysis to check for coverage.

Q3: What is the recommended workflow for pre-processing an ultra-large chemical library (e.g., >1 billion compounds) for pharmacophore screening?

- A: Pre-processing is critical for feasibility. The standard workflow involves: 1) Format Standardization (e.g., converting to a consistent tautomer/protonation state). 2) Desalting and Cleaning (removing counterions, salts). 3) Conformer Generation using a fast, database-oriented method (e.g., RDKit's ETKDG). 4) Database Indexing for rapid search. This pre-processing must be done on high-performance computing (HPC) infrastructure.

Q4: How do I balance computational speed with accuracy when screening billions of compounds?

- A: Employ a multi-stage funnel approach. The first step should be a very fast, geometric screening using a coarse conformer generation. This rapidly filters billions down to millions. Subsequent stages apply more rigorous, energy-minimized conformer generation and finer tolerance matching to the reduced set, improving accuracy without the initial computational burden.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: The virtual screening job fails or runs out of memory.

- Check 1: Verify the input library format is supported and not corrupted.

- Check 2: Ensure you are using a screening software (e.g., Catalyst, Phase, MOE) configured for ultra-large screening and not a desktop-only version.

- Check 3: Partition the ultra-large library into smaller, manageable chunks and run the screening in parallel on a cluster.

- Check 4: Monitor RAM usage; pre-processing may require terabytes of storage and hundreds of gigabytes of RAM.

Issue: The post-screen analysis yields an unmanageably large number of hits (>1% of the library).

- Check 1: Re-evaluate your pharmacophore model's feature tolerances. They may be too lenient.

- Check 2: Introduce excluded volume spheres based on the protein's active site crystal structure to eliminate sterically clashing molecules.

- Check 3: Apply simple property filters (e.g., molecular weight, logP, rotatable bonds) before or immediately after pharmacophore screening to adhere to drug-like (Lipinski's Rule of Five) or lead-like criteria.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Generation and Validation of a Target-Specific Pharmacophore Model

Methodology:

- Data Curation: Collect a diverse set of known high-affinity ligands and (critically) known inactive compounds for the target.

- Ligand Preparation: Optimize the geometry of all ligands using a molecular mechanics force field (e.g., MMFF94). Generate multiple low-energy conformers for each ligand.

- Model Generation: Use a common-feature approach (e.g., HipHop in Catalyst, Common Features Pharmacophore in Schrödinger's Phase). Align the active molecules to identify 3D spatial arrangements of chemical features (H-bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions, charged groups) common to their bioactive conformations.

- Model Validation:

- Test Set Decoy Screening: Screen the model against a test set containing known actives and decoys (assumed inactives, e.g., from the DUD-E database).

- Quantitative Analysis: Calculate enrichment metrics (see Table 1).

Table 1: Key Validation Metrics for Pharmacophore Models

| Metric | Formula / Description | Ideal Value |

|---|---|---|

| Enrichment Factor (EF) | (Hitssampled / Nsampled) / (Hitstotal / Ntotal) |

>10 (for early enrichment) |

| Area Under the Curve (AUC) | Area under the ROC curve. | >0.7 |

| Goodness of Hit Score (GH) | Combines yield of actives and coverage of actives. | >0.7 |

| % Yield of Actives | (Number of actives found / Total hits found) * 100 |

Model-dependent, higher is better |

Protocol 2: Multi-Stage Virtual Screening of an Ultra-Large Library

Methodology:

- Stage 1: Geometric Pre-screening: Screen the entire pre-processed library using a fast, shape-based or pharmacophore-based method with low conformational sampling. Goal: Reduce library size by 99.9%.

- Stage 2: Rigorous Pharmacophore Screening: Apply the validated pharmacophore model from Protocol 1 to the output of Stage 1. Use stricter tolerances and better conformer sampling. Goal: Reduce to 0.01%-0.1% of the original library.

- Stage 3: Molecular Docking: Dock the top hits from Stage 2 into the protein's binding site using a high-accuracy docking scoring function. This adds a critical structure-based filter.

- Stage 4: Visual Inspection & Clustering: Manually inspect top-ranking docked poses for sensible interactions and cluster results by chemotype to prioritize diverse scaffolds for purchase and testing.

Visualizations

Title: Ultra-Large Library Screening Funnel

Title: Pharmacophore Model Development Cycle

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents & Software for Pharmacophore-Based Screening

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Schrödinger Suite (Phase) | Industry-standard software for pharmacophore model development, validation, and screening. |

| OpenEye Toolkits | Provides high-performance cheminformatics and conformer generation libraries (e.g., OMEGA) optimized for large-scale screening. |

| RDKit | Open-source cheminformatics toolkit essential for library pre-processing, SMILES parsing, and basic conformer generation. |

| ZINC20/Enamine REAL | Source of commercially available, pre-processed ultra-large chemical libraries for virtual screening. |

| DUD-E Database | Provides decoys for validation; contains known actives and property-matched presumed inactives for many targets. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Essential computational infrastructure for processing and screening libraries exceeding 1 billion compounds. |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Primary source for 3D protein structures used to guide pharmacophore feature placement and define excluded volumes. |

Refining and Enhancing Model Performance for Superior Outcomes

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs on Pharmacophore Model Performance

Question: My pharmacophore model has high sensitivity but poor specificity, leading to too many false positives in virtual screening. How can I improve specificity without sacrificing too much sensitivity?

Answer: This is a common challenge in model optimization. The key is to implement feature selection strategies that explicitly aim to balance these metrics.

- Strategy 1: Employ a Balance-Optimized Feature Selection Method. Research has shown that using a Support Vector Machine (SVM)-based feature selection method optimized with a "Balance Index" can effectively maintain an accurate and well-balanced result. One study achieved a sensitivity of 74.36% and a specificity of 82.42% by selecting the 6 most relevant features, resulting in a balance index of 18.64% [19].

- Strategy 2: Optimize the Classification Threshold. For models that output a continuous value (like a score or probability), do not rely on a default threshold (e.g., 0.5). Instead, determine an optimal threshold that minimizes the difference between sensitivity and specificity. Approaches like the Regression Optimal (RO) and Threshold Bayesian Optimum (BO) methods have been proven superior for selecting top performers by tuning this threshold [20].

- Strategy 3: Integrate Structure-Based Pharmacophore Analysis. Leverage machine learning to analyze pharmacophore features derived from an ensemble of protein conformations. This helps identify the key pharmacophore features uniquely associated with ligand-selective conformations, which can significantly enrich true positive hits and improve model specificity [21].

Question: When generating a model, which metrics should I prioritize—sensitivity, specificity, or others—to ensure a robust model for virtual screening?

Answer: While sensitivity and specificity are core, a single metric is insufficient. You should use a suite of metrics to assess model robustness.

- Sensitivity is crucial for correctly identifying true actives (minimizing false negatives) [20].

- Specificity is vital for correctly rejecting inactive compounds (minimizing false positives) [20].

- The Z'-factor is a key metric for assay quality that considers both the assay window and the data variability. An assay with a Z'-factor > 0.5 is considered suitable for screening. A large assay window with high noise can have a worse Z'-factor than an assay with a smaller window but low noise [22].

- The F1 Score and Kappa Coefficient are also valuable for evaluating the overall performance of a classification model, especially with imbalanced datasets [20].

Question: My virtual screening process is too slow for ultra-large libraries. Are there ways to accelerate it without compromising the quality of hits?

Answer: Yes, machine learning can drastically accelerate screening.

- Strategy: Use ML to Predict Docking Scores. You can train an ensemble machine learning model on the results of a molecular docking program to predict docking scores directly from molecular structures. This approach can be 1000 times faster than classical docking-based screening and allows you to prioritize compounds for more rigorous (but slower) investigation [23].

Experimental Protocols for Key Strategies

Protocol 1: SVM-Based Feature Selection with Balance Index

This protocol is adapted from methods used to optimize the classification of weaning trial outcomes [19].

- Data Preparation: Standardize your dataset, ensuring it is well-characterized with known active and inactive compounds.

- SVM Parameter Tuning: Select the most suitable SVM parameters (e.g., cost parameters C+ and C-, kernel parameter σ) for your specific classification task.

- Feature Selection Loop: Implement a feature selection process (e.g., recursive feature elimination) that uses the trained SVM.

- Balance Index Optimization: For each feature subset, calculate the Balance Index (B), defined as the difference in misclassification rates between classes. The goal is to select the smallest set of features that keeps B below a predefined target (e.g., 40%).

- Validation: Validate the final model with the selected features on a hold-out test set, reporting accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and the final Balance Index.

Protocol 2: Machine Learning-Accelerated Virtual Screening

This protocol is based on a methodology developed for discovering monoamine oxidase inhibitors [23].

- Generate Training Data: Perform molecular docking with your preferred software (e.g., Smina) on a diverse set of known actives and inactives to generate a dataset of compounds and their docking scores.

- Compute Molecular Descriptors: Calculate multiple types of molecular fingerprints and descriptors for all compounds in the training set.

- Train Ensemble ML Model: Train an ensemble machine learning model (e.g., using multiple algorithms like Random Forest, Gradient Boosting) to predict the docking scores based on the molecular descriptors.

- Screen Chemical Library: Apply the trained model to a large chemical database (e.g., ZINC) to predict docking scores for all compounds.

- Prioritize and Validate: Select top-ranked compounds from the ML prediction and validate their activity through experimental testing.

Table 1: Performance of Different Model Optimization Approaches

| Model/Method | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Key Performance Metric | Reported Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SVM with Balance Index [19] | 74.36 | 82.42 | Balance Index: 18.64% | Accuracy: 80% with 6 selected features. |

| Regression Optimal (RO) [20] | Best Performance | Not Specified | F1 Score, Kappa | Outperformed other models by 9.6% to 60.9% in F1 score. |

| ML-Powered VS [23] | Not Specified | Not Specified | Screening Speed | 1000x faster than classical docking-based screening. |

| Pharmacophore-ML Framework [21] | Not Specified | Not Specified | Database Enrichment | Up to 54-fold improvement over random selection. |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Tools and Reagents for Featured Experiments

| Item | Function in Experiment | Example / Context |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Docking Software (e.g., Smina) | Calculates the binding pose and affinity of a ligand to a target protein. Used to generate training data for ML models [23]. | Structure-based virtual screening. |

| Machine Learning Library (e.g., Scikit-learn, PyTorch) | Builds predictive models for docking scores or performs feature selection. | Used to create ensemble models for accelerated screening [23] and SVM for feature selection [19]. |

| Pharmacophore Modeling Software (e.g., MOE SiteFinder) | Identifies and maps key interaction features (donor, acceptor, hydrophobic, etc.) in a protein binding site [21]. | Analyzing ensembles from MD simulations to find features linked to ligand binding. |

| TR-FRET Assay Reagents | Used in biochemical assays for hit validation. The ratio of acceptor/donor signals accounts for pipetting variances and reagent variability [22]. | Critical for obtaining robust experimental data with a high Z'-factor for screening. |

Workflow Visualization

SVM Feature Selection Workflow

ML-Accelerated Screening Workflow

Balancing Sensitivity and Specificity

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the key difference between a traditional pharmacophore and an informacophore? A traditional pharmacophore is defined as "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target structure" [24]. It relies on human-defined heuristics and chemical intuition. In contrast, the informacophore extends this concept by integrating data-driven insights from computed molecular descriptors, fingerprints, and machine-learned representations of chemical structure. This fusion creates a more systematic, bias-resistant strategy for scaffold modification and optimization [25].

FAQ 2: How can machine learning models improve the specificity of E3 ligase binding predictions? Machine learning models, such as the gradient boosting model (XGBoost), can use pharmacophore fingerprints like Extended Reduced Graph (ErG) to classify compounds based on their potential to bind specific E3 ligases. One model achieved 93.8% accuracy in assigning known binders to their correct E3 ligase, demonstrating high specificity. This approach helps enrich libraries with high-probability candidates and defines geometric and interaction rules for each E3 ligase [26].

FAQ 3: My generative model produces molecules with high predicted affinity but low structural novelty. How can I improve scaffold hopping? Generative models can be constrained by their training data. Integrating interpretable, ligand-based pharmacophore fingerprints into a generative pre-training transformer (GPT) framework, as seen in the TransPharmer model, can enhance scaffold hopping. This method focuses the model on key pharmaceutical features rather than specific structural skeletons, promoting the generation of structurally distinct but pharmaceutically related compounds [27].

FAQ 4: What are the best practices for preparing a high-quality dataset for a pharmacophore-based machine learning project? The first step is to gather a robust dataset of known active ligands, which can be merged from multiple public and commercial resources to ensure breadth. It is critical to address class imbalance; one effective tactic is to group low-population classes into a common "Other" category. Finally, feature selection is important: descriptor columns showing variance lower than a set threshold (e.g., 0.2) should be removed, as constant or low-variance features do not contribute to predictive models [26].

FAQ 5: How can I validate that my informacophore model has successfully reduced intuitive bias in the design process?

Successful bias reduction is indicated by the model's ability to identify active compounds with scaffolds that are structurally novel and distinct from those in the training set. Prospective validation through wet-lab experiments is the ultimate test. For example, in one case study, a pharmacophore-informed model generated a new 4-(benzo[b]thiophen-7-yloxy)pyrimidine scaffold for PLK1, and the synthesized compound showed potent activity (5.1 nM), confirming the model moved beyond simple analogy of known actives [27].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Low Model Accuracy and Poor Generalization

Problem: Your machine learning model for predicting target binding shows high accuracy on training data but performs poorly on unseen test compounds.

Solutions:

- Check Dataset Balance and Quality: Ensure your dataset of active ligands is representative and balanced across different target classes. For under-represented targets (e.g., with less than 20 compounds), consider grouping them into a common class (e.g., "Other") to reduce the negative effect of class imbalance on model performance [26].

- Apply Variance Filtering: Remove molecular descriptor columns or fingerprint bits that show little to no variance (e.g., variance lower than 0.2). These constant features add noise and do not contribute to the model's predictive power, potentially leading to overfitting [26].

- Validate with External Libraries: Test the predictive power of your model by running it on large, commercial compound libraries (e.g., Asinex). This validates the model's ability to enrich these libraries with high-probability candidates in a real-world scenario [26].

Issue 2: Lack of Structural Novelty in Generated Compounds

Problem: Your generative model produces molecules that are highly similar to known actives, offering limited inspiration for medicinal chemists.

Solutions:

- Incorporate Pharmacophore Prompts: Use multi-scale, interpretable pharmacophore fingerprints as direct input (prompts) for your generative model. This shifts the model's focus from replicating specific molecular skeletons to capturing the essential pharmaceutical features, thereby enabling scaffold hopping [27].

- Benchmark for Novelty: Use established benchmarks like GuacaMol and MOSES to quantitatively evaluate the novelty, diversity, and uniqueness of the molecules generated by your model. Compare your model's performance against other baseline generative models to identify weaknesses [27].

- Implement a "Chemical Exploration" Mode: Configure your generative framework to include a specific mode for probing the local chemical space around a reference compound. This encourages the generation of structurally distinct analogues that maintain the core pharmacophoric features [27].

Issue 3: Difficulty in Interpreting Machine Learning Model Predictions

Problem: The "black box" nature of your complex ML model makes it difficult to understand which chemical features are driving the predictions of bioactivity.

Solutions:

- Adopt Explainable AI (XAI) Techniques: Use "transparent" machine learning models like gradient boosting (XGBoost), which provide insights into feature importance. This helps in understanding which specific pharmacophore features the model deems critical for binding to a particular target [26].