Cross-Validation Strategies for Genomic Cancer Classifiers: A Guide for Robust Model Development

This article provides a comprehensive guide to cross-validation (CV) strategies for developing and validating machine learning models in genomic cancer classification.

Cross-Validation Strategies for Genomic Cancer Classifiers: A Guide for Robust Model Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to cross-validation (CV) strategies for developing and validating machine learning models in genomic cancer classification. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles of CV, including its critical role in preventing overoptimistic performance estimates in high-dimensional genomic data. The content explores methodological applications of various CV techniques, from k-fold to nested designs, specifically within cancer genomics contexts. It addresses common pitfalls and optimization strategies for handling dataset shift and class imbalance, and concludes with frameworks for rigorous model validation and comparative analysis to ensure clinical translatability, ultimately supporting the development of reliable diagnostic and prognostic tools in precision oncology.

Why Cross-Validation is Non-Negotiable in Genomic Cancer Classification

The Problem of Overfitting in High-Dimensional Genomic Data

In the field of genomic cancer research, high-dimensional data presents both unprecedented opportunities and significant analytical challenges. Advances in high-throughput technologies like RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) now enable researchers to generate massive biological datasets containing tens of thousands of gene expression features [1]. While these datasets offer unprecedented opportunities for cancer subtype classification and biomarker discovery, their high dimensionality, redundancy, and the presence of irrelevant features pose significant challenges for computational analysis and predictive modeling [1]. The fundamental problem lies in the "p >> n" scenario, where the number of features (genes) vastly exceeds the number of samples (patients), creating conditions where models can easily memorize noise rather than learning biologically meaningful signals [2].

This overfitting problem is particularly acute in cancer genomics, where sample sizes are often limited due to the difficulty and cost of collecting clinical specimens, yet each sample may contain expression data for over 20,000 genes [3]. The consequences of overfitting are severe: models that appear highly accurate during training may fail completely when applied to new patient data, potentially leading to incorrect biological conclusions and flawed clinical predictions. Thus, developing robust strategies to mitigate overfitting is not merely a statistical concern but an essential prerequisite for reliable genomic cancer classification.

Comparative Analysis of Anti-Overfitting Strategies

Internal Validation Methods

Internal validation strategies are crucial for obtaining realistic performance estimates and mitigating optimism bias in high-dimensional genomic models. A recent simulation study specifically addressed this challenge by comparing various internal validation methods for Cox penalized regression models in transcriptomic data from head and neck tumors [4]. The researchers simulated datasets with clinical variables and 15,000 transcripts across various sample sizes (50-1000 patients) with 100 replicates each, then evaluated multiple validation approaches.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Internal Validation Methods for Genomic Data

| Validation Method | Stability with Small Samples (n=50-100) | Performance with Larger Samples (n=500-1000) | Risk of Optimism Bias | Recommended Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Train-Test Split (70/30) | Unstable performance | Moderate stability | High | Preliminary exploration only |

| Conventional Bootstrap | Overly optimistic | Still optimistic | Very high | Not recommended |

| 0.632+ Bootstrap | Overly pessimistic | Becomes more accurate | Low (but pessimistic) | Specialized applications |

| k-Fold Cross-Validation | Moderate stability | High stability and reliability | Low | Recommended standard |

| Nested Cross-Validation | Moderate stability (varies with regularization) | High stability (with careful tuning) | Very low | Recommended for final models |

The findings demonstrated that train-test validation showed unstable performance, while conventional bootstrap was over-optimistic [4]. The 0.632+ bootstrap method, though less optimistic, was found to be overly pessimistic, particularly with small samples (n = 50 to n = 100) [4]. Both k-fold cross-validation and nested cross-validation showed improved performance with larger sample sizes, with k-fold cross-validation demonstrating greater stability across simulations [4]. Based on these comprehensive simulations, k-fold cross-validation and nested cross-validation are recommended for internal validation of high-dimensional time-to-event models in genomics [4].

Feature Selection Techniques

Feature selection represents another powerful strategy for combating overfitting by reducing dimensionality before model training. By selecting only the most informative genes, researchers can eliminate noise and redundancy while improving model interpretability [1].

Nature-Inspired Feature Selection Algorithms: The Dung Beetle Optimizer (DBO) is a recent nature-inspired metaheuristic algorithm that has shown promise for feature selection in high-dimensional gene expression datasets [1]. DBO simulates dung beetles' foraging, rolling, obstacle avoidance, stealing, and breeding behaviors to effectively identify informative and non-redundant subsets of genes [1]. When integrated with Support Vector Machines (SVM) for classification, this DBO-SVM framework achieved 97.4-98.0% accuracy on binary cancer datasets and 84-88% accuracy on multiclass datasets, demonstrating how feature selection can enhance performance while reducing computational cost [1].

Regularization-Based Feature Selection: Penalized regression methods like Lasso (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator) and Ridge Regression provide embedded feature selection capabilities [3]. Lasso incorporates L1 regularization that drives some coefficients exactly to zero, effectively performing automatic feature selection, while Ridge Regression uses L2 regularization to shrink coefficients without eliminating them entirely [3]. These methods are particularly valuable for RNA-seq data characterized by high dimensionality, gene-gene correlations, and significant noise [3].

Table 2: Comparison of Feature Selection Methods for Genomic Data

| Method | Mechanism | Key Advantages | Performance on Cancer Data | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dung Beetle Optimizer (DBO) | Nature-inspired metaheuristic search | Balances exploration and exploitation; avoids local optima | 97.4-98.0% accuracy (binary), 84-88% (multiclass) [1] | Requires parameter tuning; computationally intensive |

| Lasso (L1) Regression | Shrinks coefficients to zero via L1 penalty | Automatic feature selection; produces sparse models | Identifies compact gene subsets with high discriminative power [3] | Sensitive to correlated features; may select arbitrarily from correlated groups |

| Ridge (L2) Regression | Shrinks coefficients without eliminating via L2 penalty | Handles multicollinearity well; more stable than Lasso | Provides stable feature weighting but doesn't reduce dimensionality [3] | All features remain in model; less interpretable for high-dimensional data |

| Random Forest | Feature importance scoring | Robust to noise; handles non-linear relationships | Effective for identifying biomarker candidates [3] | Computationally intensive for very high dimensions; importance measures can be biased |

Data Balancing and Augmentation

Cancer datasets frequently exhibit class imbalance, where certain cancer subtypes are significantly underrepresented [2]. This imbalance can further exacerbate overfitting, as models may become biased toward majority classes. The synthetic minority oversampling technique (SMOTE) algorithm has been successfully applied to address this challenge by artificially synthesizing new samples for minority classes [2]. The basic SMOTE approach analyzes minority class samples and generates synthetic examples along line segments connecting each minority class sample to its k-nearest neighbors [2]. When combined with deep learning architectures, this approach has demonstrated improved classification performance for imbalanced cancer subtype datasets [2].

Experimental Protocols for Robust Genomic Classification

Protocol 1: DBO-SVM Framework for Cancer Classification

The Dung Beetle Optimizer with Support Vector Machines represents a sophisticated wrapper approach to feature selection and classification [1]:

Step 1: Problem Formulation - For a dataset with D features, feature selection is formulated as finding a subset S ⊆ {1,...,D} that minimizes classification error while keeping |S| small. Each candidate solution (dung beetle) is represented by a binary vector x = (x₁, x₂, ..., xD) where xj = 1 indicates feature j is selected [1].

Step 2: Fitness Evaluation - The quality of each candidate solution is evaluated using a fitness function that combines classification error and subset size: Fitness(x) = α·C(x) + (1-α)·|x|/D, where C(x) denotes the classification error on a validation set, |x| is the number of selected features, and α ∈ [0.7,0.95] balances accuracy versus compactness [1].

Step 3: DBO Optimization - The population of candidate solutions evolves through simulated foraging, rolling, breeding, and stealing behaviors, which balance exploration (global search) and exploitation (local refinement) [1].

Step 4: Classification - The optimal feature subset identified by DBO is used to train an SVM classifier with Radial Basis Function (RBF) kernels, which provide robust decision boundaries even in high-dimensional spaces [1].

Validation: The entire process should be embedded within a nested cross-validation framework to ensure reliable performance estimates [4].

Protocol 2: Deep Learning with Data Balancing

For deep learning approaches applied to genomic cancer classification, a specific protocol addresses both dimensionality and class imbalance:

Step 1: Data Balancing - Apply SMOTE to equalize cancer subtype class distributions. For each sample xi in minority classes, calculate Euclidean distance to all samples in the minority class set to find k-nearest neighbors, then construct synthetic samples using: xnew = xi + (xn - xi) × rand(0,1), where xn is a randomly selected nearest neighbor [2].

Step 2: Feature Normalization - Standardize gene expression data using Z-score normalization: X' = (x - u)/σ, where u is the feature mean and σ is the standard deviation, ensuring all features have zero mean and unit variance [2].

Step 3: Deep Learning Architecture - Implement a hybrid neural network such as DCGN that combines convolutional neural networks (CNN) for local feature extraction with bidirectional gated recurrent units (BiGRU) for capturing long-range dependencies in genomic data [2].

Step 4: Regularized Training - Incorporate dropout layers and L2 weight regularization during training to prevent overfitting, with careful monitoring of validation performance for early stopping [2].

Validation: Use stratified k-fold cross-validation to maintain class proportions across splits and obtain reliable performance estimates [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Implementing robust genomic cancer classifiers requires both computational tools and carefully curated data resources. The following table outlines key solutions available to researchers:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Genomic Cancer Classification

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Key Features | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| genomic-benchmarks | Python Package | Standardized datasets for genomic sequence classification | Curated regulatory elements; interface for PyTorch/TensorFlow [5] | https://github.com/ML-Bioinfo-CEITEC/genomic_benchmarks |

| TraitGym | Benchmark Dataset | Causal variant prediction for Mendelian and complex traits | 113 Mendelian and 83 complex traits with carefully constructed controls [6] | https://huggingface.co/datasets/songlab/TraitGym |

| DNALONGBENCH | Benchmark Suite | Long-range DNA dependency tasks | Five genomics tasks considering dependencies up to 1 million base pairs [7] | Available via research publication [7] |

| TCGA RNA-seq Data | Genomic Data | Cancer gene expression analysis | 801 samples across 5 cancer types; 20,531 genes [3] | UCI Machine Learning Repository |

| SCANDARE Cohort | Clinical Genomic Data | Head and neck cancer prognosis | 76 patients with clinical variables and transcriptomic data [4] | NCT03017573 |

The problem of overfitting in high-dimensional genomic data remains a significant challenge in cancer research, but methodological advances in validation strategies, feature selection, and data balancing provide powerful countermeasures. The experimental evidence consistently demonstrates that approaches combining rigorous internal validation like k-fold cross-validation [4] with sophisticated feature selection [1] and appropriate data preprocessing [2] yield more reliable and generalizable cancer classifiers.

As the field progresses, standardized benchmark datasets [6] [5] and comprehensive validation protocols will be essential for comparing methods and ensuring reproducible research. By adopting these robust strategies, researchers can develop genomic cancer classifiers that not only achieve high accuracy on training data but, more importantly, maintain their predictive power when applied to new patient populations, ultimately accelerating progress toward precision oncology.

Defining Generalization Performance for Clinical Trust

In translational oncology, the transition of machine learning models from research tools to clinical assets hinges on their generalization performance—the ability to maintain diagnostic accuracy across diverse patient populations, sequencing platforms, and healthcare institutions. This capability forms the cornerstone of clinical trust, particularly for genomic cancer classifiers that must operate reliably in the complex, heterogeneous landscape of human cancers. Within cross-validation strategies for genomic cancer classifier research, generalization performance transcends conventional performance metrics to encompass model robustness, institutional transferability, and demographic stability.

The clinical imperative for generalization is most acute in cancers of unknown primary (CUP), where accurate tissue-of-origin identification directly determines therapeutic pathways and significantly impacts patient survival outcomes. Current molecular classifiers face substantial challenges in achieving true generalization due to technical variability in genomic sequencing platforms, institutional biases in training datasets, and the inherent biological heterogeneity of malignancies across patient populations. This comparative analysis examines the generalization performance of three prominent genomic cancer classifiers—OncoChat, GraphVar, and CancerDet-Net—through the lens of their architectural innovations, validation methodologies, and clinical applicability.

Comparative Performance Analysis of Genomic Classifiers

Table 1: Generalization Performance Metrics Across Cancer Classifiers

| Classifier | Architecture | Cancer Types | Sample Size | Accuracy | F1-Score | Validation Framework | Clinical Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OncoChat | Large Language Model (Genomic alterations) | 69 | 158,836 tumors | 0.774 | 0.756 | Multi-institutional (AACR GENIE) | 26 confirmed CUP cases (22 correct) |

| GraphVar | Multi-representation Deep Learning (Variant maps + numeric features) | 33 | 10,112 patients | 0.998 | 0.998 | TCGA holdout validation | Pathway enrichment analysis |

| CancerDet-Net | Vision Transformer + CNN (Histopathology images) | 9 | 7,078 images | 0.985 | N/R | Cross-dataset (LC25000, ISIC 2019, BreakHis) | Web and mobile deployment |

Performance metrics compiled from respective validation studies [8] [9] [10]

The generalization performance of OncoChat is particularly notable for its validation across 19 institutions within the AACR GENIE consortium, demonstrating consistent performance with a precision-recall area under the curve (PRAUC) of 0.810 (95% CI, 0.803-0.816) across diverse sequencing panels and demographic groups [8]. This institutional robustness suggests a lower likelihood of performance degradation when deployed across heterogeneous clinical settings—a critical consideration for clinical trust.

GraphVar exemplifies exceptional classification performance on TCGA data, achieving remarkable accuracy (99.82%) across 33 cancer types through its innovative multi-representation learning framework that integrates both image-based variant maps and numeric genomic features [10]. However, its generalization to non-TCGA datasets remains to be established, highlighting the fundamental tension between single-source optimization and multi-institutional applicability.

CancerDet-Net addresses generalization through a different modality, employing cross-scale feature fusion to maintain performance across diverse histopathology imaging platforms and staining protocols [9]. Its reported 98.51% accuracy across four major cancer types using vision transformers with local-window sparse self-attention demonstrates the potential of computer vision approaches for multi-cancer classification, though its applicability to genomic data is limited.

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Frameworks

OncoChat: Multi-Institutional Validation Protocol

The experimental protocol for OncoChat's validation exemplifies contemporary best practices for establishing generalization performance in genomic classifiers:

Data Curation and Partitioning

- Data Source: 163,585 targeted panel sequencing samples from AACR Project GENIE spanning 19 institutions [8]

- Cohort Composition: 158,836 cancers with known primary (CKP) across 69 tumor types + 4,749 CUP cases

- Preprocessing: Genomic alterations (SNVs, CNVs, SVs) formatted into instruction-tuning compatible dialogues for LLM integration

- Dataset Partitioning: Random split of CKP dataset into training/testing sets with rigorous separation to prevent data leakage

- External Validation: Three independent CUP datasets (n=26, n=719, n=158) with subsequent type confirmation and survival outcomes

Model Architecture and Training

- Foundation: Large language model architecture adapted for genomic alteration sequences

- Input Representation: Diverse genomic alterations encoded as structured textual dialogues

- Integration: Combined SNVs, copy number variations, and structural variants in a flexible representation schema

- Comparative Baseline: Performance benchmarked against OncoNPC and GDD-ENS using identical test sets

This multi-institutional framework with independent CUP validation provides compelling evidence for real-world generalization, particularly the survival outcome correlations in larger CUP cohorts, which substantiate clinical relevance beyond mere classification accuracy [8].

GraphVar: Multi-Representation Learning Framework

GraphVar's methodology introduces a novel approach to feature representation that enhances model performance:

Data Preparation and Transformation

- Data Source: 10,112 patient samples from TCGA across 33 cancer types [10]

- Variant Map Construction: Somatic variants encoded into N×N matrices with pixel intensities representing variant categories (SNPs=blue, insertions=green, deletions=red)

- Numeric Feature Extraction: 36-dimensional feature matrix derived from allele frequencies and somatic variant spectra

- Data Partitioning: 70% training, 10% validation, 20% testing with patient-level separation and stratified sampling

Dual-Stream Architecture

- Image Processing Branch: ResNet-18 backbone for spatial feature extraction from variant maps

- Numeric Processing Branch: Transformer encoder for contextual pattern recognition in feature matrices

- Feature Fusion: Concatenated representations processed through fully connected classification head

- Implementation: Python/PyTorch framework with scikit-learn for metric computation

The multi-representation approach demonstrates how integrating complementary data modalities can enhance feature richness and potentially improve generalization, though the exclusive reliance on TCGA data limits cross-institutional validation [10].

Cross-Validation Strategies for Generalization Assessment

Each classifier employed distinct cross-validation strategies reflective of their clinical aspirations:

OncoChat: Institutional hold-out validation assessing performance consistency across MSK, DFCI, and DUKE cancer centers, with specific evaluation of metastatic vs. primary tumor classification performance [8]

GraphVar: Standardized TCGA hold-out validation with stratified sampling to maintain class balance, complemented by Grad-CAM interpretability analysis and KEGG pathway enrichment for biological validation [10]

CancerDet-Net: Cross-dataset validation using LC25000, ISIC 2019, and BreakHis datasets individually and in combined multi-cancer configurations to assess domain adaptation capabilities [9]

These methodological approaches highlight the evolving understanding of generalization in genomic cancer classification, where traditional train-test splits are increasingly supplemented with institutional, demographic, and technological variability assessments.

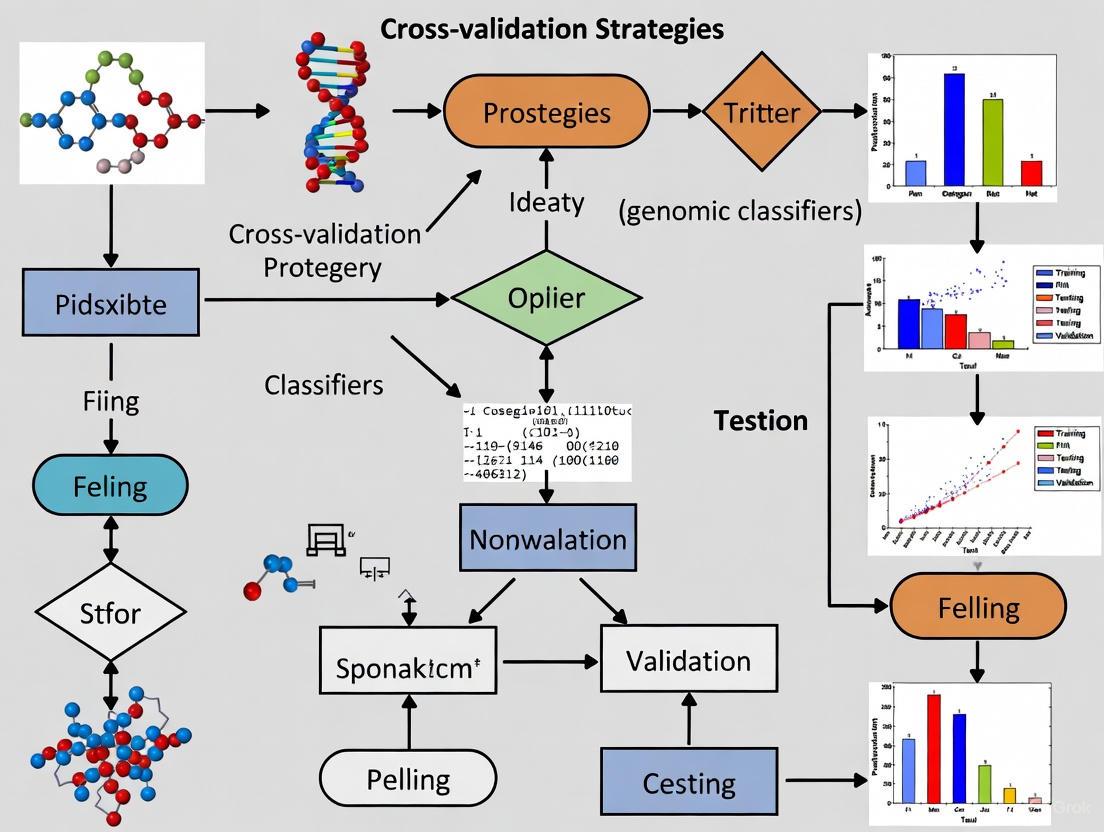

Visualization of Experimental Workflows

OncoChat Validation Framework

OncoChat employs a comprehensive multi-stage validation framework emphasizing real-world CUP cases.

GraphVar Multi-Representation Architecture

GraphVar's dual-stream architecture processes complementary genomic representations for enhanced feature learning.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Experimental Resources for Genomic Classifier Development

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Function in Research | Exemplary Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomic Datasets | AACR GENIE, TCGA, LC25000, ISIC 2019, BreakHis | Provide standardized, annotated multi-cancer genomic and histopathology data for training and validation | OncoChat: 158,836 GENIE tumors [8]; GraphVar: 10,112 TCGA samples [10] |

| Sequencing Platforms | Targeted panels (MSK-IMPACT), NGS, WGS, WES | Generate genomic alteration profiles (SNVs, CNVs, SVs) from tumor samples | OncoChat: Targeted cancer gene panels [8]; Market shift from Sanger to NGS [11] |

| Machine Learning Frameworks | PyTorch, TensorFlow, scikit-learn | Provide algorithms, neural architectures, and training utilities for model development | GraphVar: PyTorch implementation [10]; General ML tools [12] [13] [14] |

| Interpretability Tools | Grad-CAM, LIME, pathway enrichment analysis | Enable model transparency and biological validation of predictions | GraphVar: Grad-CAM + KEGG pathways [10]; CancerDet-Net: LIME + Grad-CAM [9] |

| Clinical Validation Resources | CUP cohorts with confirmed primaries, survival outcomes, treatment response | Establish clinical relevance and prognostic value of classifier predictions | OncoChat: 26 CUP cases with subsequent confirmation [8] |

The evolving landscape of genomic cancer diagnostics reflects increasing integration of automated platforms like the Idylla system, which enables rapid biomarker assessment with turnaround times under 3 hours, and liquid biopsy technologies that facilitate non-invasive monitoring through ctDNA analysis [11]. These technological advances expand the potential application domains for genomic classifiers while introducing additional dimensions of generalization across specimen types and temporal sampling.

The comparative analysis of OncoChat, GraphVar, and CancerDet-Net reveals that generalization performance in genomic cancer classifiers is multidimensional, encompassing technical robustness across sequencing platforms, institutional stability across healthcare systems, and biological relevance across cancer subtypes. While each approach demonstrates distinctive strengths—OncoChat in real-world CUP validation, GraphVar in multi-representation feature learning, and CancerDet-Net in histopathology cross-dataset adaptation—their collective progress underscores several fundamental principles for building clinical trust.

First, scale and diversity of training data correlate strongly with generalization capability, as evidenced by OncoChat's performance across 19 institutions. Second, architectural innovations that capture complementary representations of genomic information, such as GraphVar's dual-stream approach, can enhance classification accuracy. Third, rigorous clinical validation with prospective cohorts and outcome correlations remains indispensable for establishing true clinical utility beyond technical performance metrics.

For researchers and drug development professionals, these findings emphasize that generalization performance must be designed into genomic classifiers from their inception, through multi-institutional data collection, comprehensive cross-validation strategies that extend beyond random splits to include institutional and demographic hold-outs, and purposeful clinical validation frameworks. As the field advances toward increasingly sophisticated multi-modal approaches integrating genomic, histopathological, and clinical data, the definition of generalization performance will continue to evolve, but its central role in building clinical trust will remain paramount for translating computational innovations into improved cancer patient outcomes.

In the field of genomic cancer research, the development of robust classifiers is fundamentally constrained by the high-dimensional nature of omics data, where the number of features (e.g., genes) vastly exceeds the number of biological samples [15] [16]. This reality makes the choice of data partitioning strategy and the management of the bias-variance tradeoff not merely theoretical considerations but critical determinants of a model's clinical utility. Bias-variance tradeoff describes the inverse relationship between a model's simplicity and its stability when faced with new data [17] [18]. Proper data partitioning through validation strategies is the primary methodological tool for navigating this tradeoff, providing realistic estimates of how a classifier will perform on independent datasets [15] [19].

The central thesis of this guide is that while simple hold-out validation is sufficient for low-dimensional data, the complexity and scale of genomic data necessitate more sophisticated strategies like k-fold and nested cross-validation to produce reliable, clinically actionable models. This article objectively compares these partitioning methods, providing experimental data from genomic studies to guide researchers and drug development professionals in selecting the optimal validation framework for their cancer classifiers.

Theoretical Foundations: The Bias-Variance Tradeoff

Decomposing Prediction Error

In machine learning, the error a model makes on unseen data can be systematically broken down into three components: bias, variance, and irreducible error. This decomposition is formalized for a squared error loss function as follows [17]:

E[(y - ŷ)²] = (Bias[ŷ])² + Var[ŷ] + σ²

- Bias is the error stemming from overly simplistic assumptions made by a model. A high-bias model fails to capture complex patterns in the data, leading to underfitting. This is characterized by consistently poor performance on both training and test data [17] [18] [20].

- Variance is the error due to a model's excessive sensitivity to small fluctuations in the training set. A high-variance model learns the training data too closely, including its noise, leading to overfitting. Such a model typically shows a large performance gap between high training accuracy and low testing accuracy [17] [18].

- Irreducible Error is the inherent noise in the data itself, which cannot be reduced by any model [17].

The tradeoff arises because reducing bias (by increasing model complexity) typically increases variance, and reducing variance (by simplifying the model) typically increases bias [17] [20]. The goal is to find a balance where the total of these two errors is minimized.

Impact of Model Complexity

The relationship between model complexity and the bias-variance tradeoff is fundamental. The following conceptual diagram illustrates how bias, variance, and total error change as a model grows more complex, highlighting the optimal zone for model performance.

- Underfitting Region (High Bias, Low Variance): This occurs with overly simple models, such as linear regression applied to a complex, non-linear genomic phenomenon. These models make strong assumptions, cannot capture important patterns, and perform poorly on both training and test data [18] [21].

- Overfitting Region (Low Bias, High Variance): This occurs with overly complex models, such as deep decision trees or high-degree polynomials trained on limited genomic samples. They model the noise in the training data and fail to generalize to new data, showing high training accuracy but low test accuracy [18] [20].

- Optimal Region: The point of minimum total error represents the best balance, where the model is complex enough to capture the true underlying biological signals but simple enough to remain stable across different datasets [18] [21].

Data Partitioning Strategies for Validation

Data partitioning strategies are practical implementations of the bias-variance tradeoff principle, designed to estimate a model's true performance on unseen data.

Common Validation Methods

The table below summarizes the core data partitioning methods used in model validation.

| Method | Core Principle | Key Characteristics | Typical Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hold-Out (Train-Test Split) | Data is randomly partitioned into a single training set and a single test set [19]. | Simple and fast; performance can be highly variable and dependent on a single, arbitrary data split [16] [19]. | Initial model prototyping with large datasets. |

| K-Fold Cross-Validation | Data is divided into K equal-sized folds. The model is trained K times, each time using K-1 folds for training and the remaining fold for testing [19]. | Reduces the variance of the performance estimate compared to hold-out; makes efficient use of all data [16] [19]. | Standard for model selection and evaluation with moderate-sized datasets. |

| Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation (LOOCV) | A special case of K-Fold where K equals the number of samples. Each sample is used once as a single-item test set [22]. | Nearly unbiased estimate; computationally expensive and can have high variance in its estimate [15] [22]. | Very small datasets where maximizing training data is critical. |

| Nested Cross-Validation | Uses two layers of CV: an outer loop for performance estimation and an inner loop exclusively for model/hyperparameter tuning [15] [19]. | Provides an almost unbiased estimate of true error; computationally very intensive [15] [16]. | Final evaluation of a modeling process that involves tuning, especially with small, high-dimensional data. |

| Bootstrap Validation | Creates multiple training sets by sampling from the original data with replacement; the out-of-bag samples are used for testing [16]. | Useful for estimating statistics like model parameter confidence; the simple bootstrap can be optimistic [16]. | Methods like Random Forest, and for estimating sampling distributions. |

Workflow for Model Development and Validation

A robust machine learning pipeline involves sequential steps that must be properly integrated with the chosen validation strategy. The following diagram outlines a generalized workflow for developing a genomic classifier, highlighting where different data partitioning strategies are applied.

Comparative Analysis of Partitioning Strategies in Genomic Studies

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Empirical evidence from healthcare and genomic simulation studies demonstrates the relative performance of different validation strategies. The table below summarizes findings from key studies, highlighting the impact of each method on performance estimation.

| Source | Experimental Context | Validation Methods Compared | Key Finding on Performance Estimation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Varma et al. (2006) [15] | "Null" and "non-null" datasets using Shrunken Centroids and SVM classifiers. | Standard CV with tuning, Nested CV, and evaluation on an independent test set. | Standard CV with parameter tuning outside the loop gave substantially biased (optimistic) error estimates. Nested CV gave an estimate very close to the independent test set error. |

| Lemoine et al. (2025) [16] | Simulation of high-dimensional transcriptomic data (15,000 genes) with time-to-event outcomes. Sample sizes from 50 to 1000. | Train-test, Bootstrap, 0.632+ Bootstrap, 5-Fold CV, Nested CV (5x5). | Train-test was unstable. Bootstrap was over-optimistic. 0.632+ Bootstrap was overly pessimistic for small n. K-fold CV and Nested CV were recommended for stability and reliability. |

| Wilimitis & Walsh (2023) [19] | Tutorial using MIMIC-III clinical data for classification and regression tasks. | Hold-out validation vs. various Cross-Validation methods. | Nested cross-validation reduces optimistic bias but comes with additional computational challenges. Cross-validation is generally favored over hold-out for smaller healthcare datasets. |

Case Study: Bias in Cross-Validation for Classifier Tuning

A critical study by Varma et al. [15] illustrates a common pitfall in validation. The researchers created "null" datasets where no real difference existed between sample classes. They then used CV to find classifier parameters that minimized the CV error. This process alone produced deceptively low error estimates (<30% on 38% of "null" datasets for SVM), even though the classifier's performance on a true independent test set was no better than chance. This demonstrates that using the same data for both tuning and performance estimation introduces significant optimism bias. The nested CV procedure, where tuning is performed inside each fold of the outer validation loop, successfully corrected this bias.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Building and validating a genomic cancer classifier requires a suite of computational and data resources. The following table details key components of the research pipeline.

| Item | Function in Genomic Classifier Research |

|---|---|

| High-Dimensional Omics Data | The foundational input for model training. Public repositories like The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) provide large-scale, well-annotated genomic (e.g., RNA-seq), epigenomic, and clinical data [3] [22]. |

| Programming Environment (Python/R) | Provides the ecosystem for data manipulation, analysis, and modeling. Key libraries (e.g., scikit-learn in Python, caret in R) implement cross-validation, machine learning algorithms, and performance metrics [3] [19]. |

| Feature Selection Algorithms | Critical for reducing data dimensionality and mitigating overfitting. Methods like Lasso (L1 regularization) and Ridge (L2 regularization) regression are commonly used to identify a subset of predictive genes from thousands of candidates [16] [3]. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) | Essential for computationally intensive tasks like nested cross-validation on large genomic datasets or training complex ensemble models, significantly reducing computation time [22] [21]. |

| Stratified Cross-Validation | A specific technique that preserves the percentage of samples for each class (e.g., cancer type) in every fold. This is crucial for handling class imbalance often found in biomedical datasets and for obtaining realistic performance estimates [19] [23]. |

The selection of a data partitioning strategy is a direct application of the bias-variance tradeoff principle. For genomic cancer classification, where high-dimensional data and small sample sizes are the norm, simple hold-out validation is often inadequate and can be misleading.

Evidence from multiple studies consistently shows that k-fold cross-validation offers a stable and reliable balance between bias and variance for general model evaluation [16]. When the modeling process involves parameter tuning or feature selection, nested cross-validation is the gold standard for obtaining an almost unbiased estimate of the true error, preventing optimistic bias from creeping into performance reports [15] [19]. By rigorously applying these advanced partitioning strategies, researchers and drug developers can build more generalizable and trustworthy genomic classifiers, ultimately accelerating the path to clinical impact.

In the pursuit of precision oncology, genomic classifiers have emerged as powerful tools for cancer diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment selection. These molecular classifiers, developed from high-throughput genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic data, promise to tailor cancer care to the unique biological characteristics of each patient's tumor [24]. However, the development of classifiers from high-dimensional data presents a complex analytical challenge fraught with potential methodological pitfalls that may result in spuriously high performance estimates [25]. The stakes for proper validation are exceptionally high in this domain, as erroneous classifiers can lead to misdiagnosis, inappropriate treatment selections, and ultimately, patient harm.

Cross-validation (CV) has become a cornerstone methodology for assessing the performance and generalizability of genomic classifiers, particularly when limited samples are available. This technique provides a framework for estimating how well a classifier will perform on unseen data, simulating its behavior in real-world clinical settings. Yet, not all cross-validation approaches are created equal, and inappropriate application can generate misleadingly optimistic performance estimates [25] [26]. This guide examines current cross-validation strategies, compares their methodological rigor, and provides experimental protocols to ensure reliable assessment of genomic classifiers in oncology applications.

The Validation Gap: Empirical Evidence of Performance Inflation

Substantial empirical evidence demonstrates that common cross-validation practices can significantly overestimate the true performance of genomic classifiers. A comprehensive assessment of molecular classifier validation practices revealed that most studies employ cross-validation methods likely to overestimate performance, with marked discrepancies between internal validation and independent external validation results [25].

Table 1: Performance Discrepancy Between Cross-Validation and Independent Validation

| Performance Metric | Cross-Validation Median | Independent Validation Median | Relative Diagnostic Odds Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 94% | 88% | 3.26 (95% CI 2.04-5.21) |

| Specificity | 98% | 81% |

This validation gap stems from multiple methodological challenges. Simple resubstitution analysis of training sets is well-known to produce biased performance estimates, but even more sophisticated internal validation methods like k-fold cross-validation and leave-one-out cross-validation can yield inflated accuracy when inappropriately applied [25]. Specific sources of bias include population selection bias, incomplete cross-validation, optimization bias, reporting bias, and parameter selection bias [25].

The computational intensity of proper validation presents another challenge, particularly for complex classifiers. Standard implementations of leave-one-out cross-validation require training a model m times for m instances, while leave-pair-out methods require O(m²) training rounds [27]. These computational demands can become prohibitive with larger datasets, creating pressure to adopt less rigorous but more computationally efficient validation approaches.

Cross-Validation Techniques: A Comparative Analysis

Standard Cross-Validation Approaches

Random Cross-Validation (RCV) represents the most common approach, where samples are randomly partitioned into k folds. While theoretically sound, RCV can produce over-optimistic performance estimates when test samples are highly similar to training samples, as often occurs with biological replicates in genomic datasets [26]. This approach assumes that randomly selected test sets well-represent unseen data, an assumption that may not hold when samples come from different experimental conditions or biological contexts [26].

Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation (LOO) provides an almost unbiased estimate of performance but suffers from high variance, particularly with small sample sizes [27]. For AUC estimation, LOO can demonstrate substantial negative bias in small-sample settings [27].

Leave-Pair-Out Cross-Validation (LPO) has been proposed specifically for AUC estimation, as it is almost unbiased and maintains deviation variance as low as the best alternative approaches [27]. In this method, all possible pairs of positive and negative instances are left out for testing, making it computationally intensive but statistically favorable for AUC-based evaluations.

Advanced Approaches for Genomic Data

Clustering-Based Cross-Validation (CCV) addresses a critical flaw in RCV by first clustering experimental conditions and including entire clusters of similar conditions as one CV fold [26]. This approach tests a method's ability to predict gene expression in entirely new regulatory contexts rather than similar conditions, providing a more realistic estimate of generalizability.

Simulated Annealing Cross-Validation (SACV) represents a more controlled approach that constructs partitions spanning a spectrum of distinctness scores [26]. This enables researchers to evaluate classifier performance across varying degrees of training-test similarity, offering insights into how methods will perform when applied to datasets with different relationships to the training data.

Table 2: Comparison of Cross-Validation Techniques for Genomic Classifiers

| Technique | Key Principles | Strengths | Limitations | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random CV (RCV) | Random partitioning into k folds | Simple implementation; Widely understood | May overestimate performance; Sensitive to sample similarity | Initial model assessment; Large, diverse datasets |

| Leave-One-Out CV | Each sample alone as test set | Low bias; Uses maximum training data | High variance; Computationally intensive | Very small datasets; Nearly unbiased estimation needed |

| Leave-Pair-Out CV | All positive-negative pairs left out | Excellent for AUC estimation; Low bias | Extremely computationally intensive (O(m²)) | Small datasets where AUC is primary metric |

| Clustering-Based CV | Entire clusters as folds | Tests generalizability across contexts; More realistic performance estimates | Dependent on clustering algorithm and parameters | Assessing biological generalizability; Context-shift evaluation |

| Simulated Annealing CV | Partitions with controlled distinctness | Enables performance spectrum analysis; Controlled distinctness | Complex implementation; Computationally intensive | Comprehensive method comparison; Distinctness-impact analysis |

Experimental Protocols for Robust Validation

Protocol 1: Distinctness-Based Cross-Validation

The distinctness of test sets from training sets significantly impacts performance estimation [26]. This protocol provides a methodological framework for assessing this relationship:

Compute Distinctness Score: For each potential test experimental condition, calculate its distinctness from a given set of training conditions using only predictor variables (e.g., transcription factor expression values), independent of the target gene expression values.

Construct Partitions: Use simulated annealing to generate multiple partitions with gradually increasing distinctness scores, creating a spectrum from highly similar to highly distinct test-training set pairs.

Evaluate Performance: Train and test classifiers across these partitions, measuring performance metrics (sensitivity, specificity, AUC) at each distinctness level.

Analyze Trends: Plot performance against distinctness scores to evaluate how classifier accuracy degrades as test sets become increasingly distinct from training data.

This approach enables comparison of classifiers not merely based on average performance, but on their robustness to increasing dissimilarity between training and application contexts [26].

Protocol 2: Cross-Condition Validation for GRN Inference

For gene regulatory network (GRN) inference, standard CV may not adequately assess generalizability across biological conditions:

Cluster Conditions: Perform clustering on experimental conditions based on TF expression profiles to identify groups of similar regulatory contexts.

Form Folds: Assign entire clusters to cross-validation folds rather than individual samples.

Train and Test: Iteratively leave out each cluster-fold, train GRN inference methods on remaining data, and test prediction accuracy on the held-out cluster.

Compare to RCV: Execute standard random CV on the same dataset for comparative analysis.

Studies implementing this approach have demonstrated that RCV typically produces more optimistic performance estimates than CCV, with the discrepancy revealing the degree to which performance depends on similarity between training and test conditions [26].

Visualization of Cross-Validation Strategies

Figure 1: Cross-Validation Workflow Comparison. This diagram illustrates the key differences between standard Random Cross-Validation (RCV) and Clustering-Based Cross-Validation (CCV) approaches, highlighting how CCV tests generalizability across distinct experimental contexts.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Solutions for Validation

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Cross-Validation Experiments

| Solution Category | Specific Tools/Frameworks | Function in Validation | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical Computing | R, Python (scikit-learn) | Provides base CV implementations | Customization needed for genomic specificities |

| Machine Learning Frameworks | TensorFlow, PyTorch | Enable custom classifier development | Computational efficiency for large-scale CV |

| Specialized CV Algorithms | Leave-Pair-Out, SACV | Address specific biases in performance estimation | Implementation complexity; Computational demands |

| Clustering Methods | k-means, hierarchical clustering | Enables CCV implementation | Sensitivity to parameters; Distance metrics |

| Distinctness Scoring | Custom implementations | Quantifies test-training dissimilarity | Must use only predictor variables, not outcomes |

| Performance Metrics | AUC, sensitivity, specificity | Standardized performance assessment | AUC particularly important for class imbalance |

The development of genomic classifiers for cancer diagnostics carries tremendous responsibility, as these tools directly impact patient care decisions. The evidence clearly demonstrates that standard cross-validation approaches often yield optimistic performance estimates that do not translate to independent validation [25]. This validation gap represents a significant concern for clinical translation, potentially leading to the implementation of classifiers that underperform in real-world settings.

Moving forward, the field requires a shift toward more rigorous validation practices that explicitly account for the distinctness between training and test conditions. Clustering-based cross-validation and distinctness-controlled approaches like SACV provide promising frameworks for more realistic performance estimation [26]. Additionally, researchers should prioritize external validation in independent datasets whenever possible, as this remains the gold standard for establishing generalizability [25].

The computational burden of rigorous validation remains a challenge, particularly for complex classifiers and large genomic datasets. However, the stakes are too high to accept methodological shortcuts that compromise the reliability of performance estimates. By adopting more stringent cross-validation practices and transparently reporting validation methodologies, the research community can enhance the development of genomic classifiers that truly deliver on the promise of precision oncology.

A Practical Toolkit of Cross-Validation Methods for Cancer Genomics

In genomic cancer classifier research, where models are built on high-dimensional molecular data to predict phenotypes like cancer subtypes or survival outcomes, robust model evaluation is paramount. Cross-validation provides an essential framework for assessing how well a predictive model will generalize to independent datasets, thereby flagging problems like overfitting to the limited samples typically available in biomedical studies [28]. Among various techniques, K-Fold Cross-Validation has emerged as a widely adopted standard, striking a practical balance between computational feasibility and reliable performance estimation [29]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the parameters and alternatives to K-Fold is crucial for developing classifiers that can reliably inform biological hypothesis generation and potential clinical applications [30] [31]. This guide provides an objective comparison of K-Fold's performance against other cross-validation strategies, with a specific focus on evidence from genomic and cancer classification studies.

Understanding the K-Fold Cross-Validation Algorithm

K-Fold Cross-Validation is a resampling procedure used to evaluate machine learning models on a limited data sample. The method's core premise involves dividing the entire dataset into 'K' equally sized folds or segments. For each unique group, the algorithm treats it as a test set while using the remaining groups as a training set. This process repeats 'K' times, with each fold used exactly once as the testing set. The 'K' results are then averaged to produce a single estimation of model performance [32] [33].

The following diagram illustrates the workflow and data flow in a standard 5-fold cross-validation process:

The brilliance of K-Fold Cross-Validation lies in its ability to mitigate the bias associated with random shuffling of data into training and test sets. It ensures that every observation from the original dataset has the opportunity to appear in both training and test sets, which is crucial for models sensitive to specific data partitions [33]. This is particularly important in genomic studies where sample sizes may be limited, and each data point represents valuable biological information.

Comparative Analysis of Cross-Validation Techniques

Performance Comparison Across Methods

Different cross-validation techniques offer varying trade-offs between bias, variance, and computational requirements. The table below summarizes a comparative analysis of three common methods based on experimental data from model evaluation studies:

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Cross-Validation Techniques on Balanced and Imbalanced Datasets

| Cross-Validation Method | Best Performing Model (Imbalanced Data) | Sensitivity | Balanced Accuracy | Best Performing Model (Balanced Data) | Sensitivity | Balanced Accuracy | Computational Time (Seconds) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K-Fold Cross-Validation | Random Forest | 0.784 | 0.884 | Support Vector Machine | 0.878 | 0.892 | 21.480 (SVM) |

| Repeated K-Fold | Support Vector Machine | 0.541 | 0.764 | Support Vector Machine | 0.886 | 0.894 | ~1986.570 (RF) |

| Leave-One-Out (LOOCV) | Random Forest/Bagging | 0.787/0.784 | 0.883/0.881 | Support Vector Machine | 0.893 | 0.891 | High (Model Dependent) |

Data adapted from comparative analysis by Lumumba et al. (2024) [29]

Key Trade-Offs and Characteristics

Each cross-validation method carries distinct advantages and limitations that researchers must consider within their specific genomic context:

K-Fold Cross-Validation (typically with K=5 or K=10) generally offers a balanced compromise between computational efficiency and reliable performance estimation. It demonstrates strong performance across various models while maintaining reasonable computation times, making it suitable for medium to large genomic datasets [29] [34].

Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation (LOOCV), an exhaustive method where the number of folds equals the number of instances, provides nearly unbiased error estimation but suffers from higher variance and computational cost, particularly with large datasets. In biomedical contexts with small sample sizes, LOOCV is sometimes preferred as it maximizes the training data in each iteration [31] [28].

Repeated K-Fold Cross-Validation enhances reliability by averaging results from multiple K-fold runs with different random partitions, effectively reducing variance. However, this comes at a significant computational cost, as evidenced by processing times nearly 100 times longer than standard K-fold in some experimental comparisons [29].

Stratified K-Fold Cross-Validation preserves the class distribution in each fold, making it particularly valuable for imbalanced genomic datasets, such as those comparing cancer subtypes with unequal representation [23] [34].

Experimental Protocols in Genomic Studies

Case Study: Genomic Prediction Models in Plant Science (with Implications for Cancer Research)

Frontiers in Plant Science published a comprehensive methodological comparison of genomic prediction models using K-fold cross-validation, with protocols directly transferable to genomic cancer classifier development [30]. The experimental methodology proceeded as follows:

Dataset Preparation: Public datasets from wheat, rice, and maize were utilized, comprising 599 wheat lines with 1,279 DArT markers, 1,946 rice lines from the 3,000 Rice Genomes Project, and maize lines from the "282" Association Panel. These genomic datasets mirror the high-dimensional characteristics of cancer genomic data.

Model Selection: The study evaluated a variety of statistical models from the "Bayesian alphabet" (e.g., BayesA, BayesB, BayesC) and genomic relationship matrix models (e.g., G-BLUP, EG-BLUP), representing common approaches in genomic prediction.

Cross-Validation Protocol: The researchers implemented paired K-fold cross-validation to compare model performances. The key innovation was the use of statistical tests based on equivalence margins borrowed from clinical research to identify differences in model performance with practical relevance.

Hyperparameter Tuning: The study assessed how hyperparameters (parameters not directly estimated from data) affect predictive accuracy across models, using cross-validation to guide selection.

Performance Assessment: Predictive accuracy was evaluated through the cross-validation process, with emphasis on identifying statistically significant differences between models that would impact genetic gain - analogous to clinical utility in cancer diagnostics.

This experimental design highlights how K-fold cross-validation enables robust model comparison in high-dimensional biological data contexts, providing a template for cancer genomic classifier development.

Case Study: Bivariate Monotonic Classifiers for Biomarker Discovery

A 2025 study in BMC Bioinformatics addresses genome-scale discovery of bivariate monotonic classifiers (BMCs), with direct implications for cancer biomarker identification [31]. The research team developed the fastBMC algorithm to efficiently identify pairs of features with high predictive performance, using leave-one-out cross-validation as an integral component of their methodology:

Classifier Design: BMCs are based on pairs of input features (e.g., gene pairs) that capture nonlinear patterns while maintaining interpretability - a crucial consideration for biological hypothesis generation.

Validation Approach: The original naïveBMC algorithm used leave-one-out cross-validation to estimate classifier performance, requiring this computation for each possible pair of features. With high-dimensional genomic data, this becomes computationally prohibitive.

Computational Optimization: The fastBMC algorithm introduced a mathematical bound for the LOOCV performance estimate, dramatically speeding up computation by a factor of at least 15 while maintaining optimality.

Biological Validation: The approach was applied to a glioblastoma survival predictor, identifying a biomarker pair (SDC4/NDUFA4L2) that demonstrates the method's utility for generating testable biological hypotheses with potential therapeutic implications.

This case study illustrates how specialized cross-validation approaches can enable biomarker discovery in cancer genomics while balancing computational constraints with statistical rigor.

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Cross-Validation in Genomic Research

| Tool/Resource | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| scikit-learn Cross-Validation Module | Provides comprehensive cross-validation functionality | from sklearn.model_selection import KFold, cross_val_score |

| Stratified K-Fold | Preserves class distribution in imbalanced datasets | StratifiedKFold(n_splits=5) |

| Repeated K-Fold | Reduces variance through multiple iterations | RepeatedStratifiedKFold(n_splits=5, n_repeats=10) |

| Bivariate Monotonic Classifier (BMC) | Identifies interpretable feature pairs for biomarker discovery | Python implementation available at github.com/oceanefrqt/fastBMC [31] |

| Pipeline Construction | Ensures proper data preprocessing without data leakage | make_pipeline(StandardScaler(), SVM(C=1)) |

| Multiple Metric Evaluation | Enables comprehensive model assessment | cross_validate(..., scoring=['precision_macro', 'recall_macro']) |

Parameter Optimization in K-Fold Cross-Validation

Selecting the Optimal K Value

The choice of K in K-fold cross-validation represents a critical decision point that balances statistical properties with computational practicality:

K=5 or K=10: These values have been empirically shown to yield test error rate estimates that suffer neither from excessively high bias nor from very high variance, making them recommended defaults for many applications [32] [29].

Lower K values (2-3): May lead to higher variance in performance estimates because the training data size is substantially reduced in each iteration.

Higher K values (approaching n): Increase the training data size in each fold, potentially reducing variance but increasing computational burden and potentially introducing higher bias [33].

Stratified Variants: For classification problems with imbalanced classes, such as rare cancer subtypes, stratified K-fold ensures each fold preserves the percentage of samples for each class, providing more reliable performance estimates [23] [35].

The following decision diagram guides researchers in selecting appropriate cross-validation parameters based on their dataset characteristics and research goals:

Integration with Hyperparameter Tuning

In genomic cancer classifier development, K-fold cross-validation is frequently integrated with hyperparameter optimization through techniques such as grid search or random search. The proper implementation requires nesting the cross-validation procedures:

- Inner Loop: Used for hyperparameter tuning and model selection

- Outer Loop: Used for performance assessment of the final selected model

This nested approach prevents optimistic bias in performance estimates that occurs when the same cross-validation split is used for both parameter tuning and final evaluation [35]. For example, when optimizing the C parameter in Support Vector Machines or the number of trees in Random Forests, the inner cross-validation loop systematically evaluates different parameter combinations across the training folds, while the outer loop provides an unbiased estimate of how well the selected model will generalize.

K-Fold Cross-Validation remains the go-to standard for model evaluation in genomic cancer classifier development due to its optimal balance between statistical reliability and computational efficiency. As evidenced by comparative studies, K=5 or K=10 generally provide the most practical defaults, though researchers working with specialized classifiers or particularly challenging data structures may benefit from variations like stratified or repeated K-fold. The experimental protocols and toolkit presented here offer researchers a foundation for implementing these methods in their genomic studies, with appropriate attention to the unique characteristics of high-dimensional biomedical data. As cross-validation methodologies continue to evolve, including recent developments like irredundant K-fold cross-validation [36], the fundamental importance of robust validation practices in translating genomic discoveries to clinical applications remains undiminished.

In the field of genomic cancer classification, the problem of class imbalance presents a fundamental challenge that can severely compromise the validity of machine learning models. Cancer datasets frequently exhibit significant skewness, where the number of samples from one class (e.g., healthy patients or a common cancer subtype) vastly outnumbers others (e.g., rare cancer subtypes or metastatic cases) [37]. This imbalance is particularly pronounced in genomic studies characterized by high-dimensional feature spaces and limited sample sizes [37]. Traditional cross-validation approaches, which randomly split data into training and testing sets, risk creating folds that poorly represent the minority class, leading to overly optimistic performance estimates and models that fail to generalize to real-world clinical scenarios [38] [39].

Stratified K-Fold Cross-Validation has emerged as a critical methodological solution to this problem. It is a variation of standard K-Fold cross-validation that ensures each fold preserves the same percentage of samples for each class as the complete dataset [40]. This preservation of class distribution is not merely a technical refinement but a statistical necessity for generating reliable performance estimates in genomic cancer research, where accurately identifying minority classes (such as rare malignancies) can be of paramount clinical importance. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of Stratified K-Fold against alternative validation strategies, supported by experimental data from cancer classification studies.

Experimental Comparisons of Cross-Validation Strategies

Performance Comparison on Imbalanced Biomedical Datasets

The table below summarizes findings from a large-scale study comparing Stratified Cross-Validation (SCV) and Distribution Optimally Balanced SCV (DOB-SCV) across 420 datasets, involving several sampling methods and classifiers including Decision Trees, k-NN, SVM, and Multi-layer Perceptron [38].

| Validation Method | Key Principle | Reported Advantage | Classifier Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stratified K-Fold (SCV) | Ensures each fold has same class proportion as full dataset [40] [38]. | Provides a more reliable estimate of model performance on imbalanced data; avoids folds with missing classes [38] [39]. | Foundation for robust evaluation; often combined with sampling techniques [38]. |

| DOB-SCV | Places nearest neighbors of the same class into different folds to better maintain original distribution [38]. | Can provide slightly higher F1 and AUC values when combined with sampling [38]. | Performance gain is often smaller than the impact of selecting the right sampler-classifier pair [38]. |

The core finding was that while DOB-SCV can sometimes offer marginal improvements, the choice between SCV and DOB-SCV is generally less critical than the selection of an effective sampler-classifier combination [38]. This underscores that Stratified K-Fold provides a sufficiently robust foundation for model evaluation, upon which other techniques for handling imbalance can be built.

Efficacy of Ensemble Classifiers with Stratified K-Fold

Stratified K-Fold is frequently used to validate powerful ensemble classifiers in cancer diagnostics. The following table synthesizes results from multiple studies on breast cancer classification that utilized Stratified K-Fold validation, demonstrating state-of-the-art performance [23] [41].

| Study Focus | Classifier/Method | Key Performance Metric(s) | Stratified Validation Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Breast Cancer Classification [23] | Majority-Voting Ensemble (LR, SVM, CART) | 99.3% Accuracy [23] | Ensured reliable performance estimate on imbalanced Wisconsin Diagnostic Breast Cancer dataset. |

| Breast Cancer Classification [41] | Ensembles (AdaBoost, GBM, RGF) | 99.5% Accuracy [41] | Used alongside Stratified Shuffle Split to validate performance and ensure class representation. |

| Multi-Cancer Prediction [42] | Stacking Ensemble (12 base learners) | 99.28% Accuracy, 97.56% Recall, 99.55% Precision (average across 3 cancers) [42] | Critical for fair evaluation across lung, breast, and cervical cancer datasets with different imbalance levels. |

These results highlight a consistent trend: combining Stratified K-Fold validation with ensemble methods produces exceptionally high and, more importantly, reliable performance metrics, making them a gold standard for imbalanced cancer classification tasks.

Methodologies and Protocols

Standardized Workflow for Genomic Classifier Validation

The following diagram illustrates a recommended experimental workflow that integrates Stratified K-Fold at its core, ensuring that class imbalance is addressed at both the data and validation levels.

This workflow emphasizes two critical best practices. First, resampling techniques like SMOTE or KDE must be applied exclusively to the training folds after the split to prevent data leakage from the test set, which would invalidate the performance estimate [37] [43]. Second, the final model performance is derived from the aggregated results across all test folds, providing a robust measure of how the model will generalize to new, unseen data [39] [44].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

The table below catalogues key computational "reagents" and their functions essential for implementing Stratified K-Fold validation in genomic cancer studies.

| Research Reagent / Solution | Function / Purpose | Example / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| StratifiedKFold (scikit-learn) | Core cross-validator; splits data into K folds while preserving class distribution [40]. | from sklearn.model_selection import StratifiedKFold Essential for initial, reliable data splitting [39]. |

| Resampling Algorithms (e.g., SMOTE, KDE) | Balances class distribution within the training set by generating synthetic minority samples [37] [43]. | SMOTE: Generates samples via interpolation [43]. KDE: Resamples from estimated probability density; can outperform SMOTE on genomic data [37]. |

| High-Performance Ensemble Classifiers | Combines multiple models to improve predictive accuracy and robustness [23] [42]. | XGBoost, Random Forest, and Majority-Voting ensembles have shown >99% accuracy in stratified validation [23] [42]. |

| Imbalance-Robust Metrics | Provides a truthful evaluation of model performance on imbalanced data beyond simple accuracy [37] [43]. | AUC, F1-Score, Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC), Precision-Recall AUC [42] [43]. |

The consistent theme across comparative studies is that Stratified K-Fold Cross-Validation is a non-negotiable starting point for reliable model evaluation on imbalanced cancer datasets. While alternative methods like DOB-SCV can offer minor enhancements, the primary gain in performance and robustness comes from coupling Stratified K-Fold with appropriate ensemble classifiers and data-level resampling techniques like SMOTE or KDE [23] [38].

For researchers and clinicians developing genomic cancer classifiers, the evidence strongly supports a standardized protocol: using Stratified K-Fold as the validation backbone to ensure fair class representation, then systematically exploring combinations of modern resampling methods and powerful ensemble models like XGBoost or stacking ensembles to achieve state-of-the-art performance. This rigorous approach ensures that predictive models are not only accurate in a technical sense but also generalizable and trustworthy in high-stakes clinical environments.

In genomic cancer research, accurately estimating a classifier's real-world performance is paramount for clinical translation. Cross-validation (CV) serves as the standard for assessing model generalization, yet common practices introduce a subtle but critical flaw: optimistic bias caused by data leakage during hyperparameter tuning [45]. When the same data informs both parameter tuning and performance estimation, the test set is no longer "statistically pure," leading to inflated performance metrics and models that fail in production [45]. This problem is particularly acute in genomic studies, where datasets are often characterized by high dimensionality (thousands of genes) and small sample sizes, amplifying the risk of overfitting.

Nested cross-validation (NCV) provides a robust solution to this problem. It is a disciplined validation strategy that strictly separates the model selection process from the model assessment process [46]. By employing two layers of data folding, NCV delivers a realistic and unbiased estimate of how a model, with its tuned hyperparameters, will perform on unseen data. For researchers developing genomic cancer classifiers, adopting NCV is not merely a technical refinement but a foundational practice for building trustworthy and reliable predictive models.

Understanding Nested Cross-Validation: Architecture and Workflow

The Core Principle: Separation of Model Selection and Evaluation

The fundamental strength of nested cross-validation lies in its clear separation of duties [46]. It consists of two distinct loops, an outer loop for performance estimation and an inner loop for model and hyperparameter selection, which operate independently to prevent information leakage.

- Outer Loop (Performance Estimation): The dataset is split into ( K ) folds. Sequentially, each fold serves as a test set, while the remaining ( K-1 ) folds constitute the development set. The key is that this test set is never used for any decision-making during the model building process for that split [47].

- Inner Loop (Model Tuning): For each development set from the outer loop, a second, independent cross-validation process is performed. This inner loop is used to train models with different hyperparameters and select the best-performing set. The outer loop's test set is completely untouched during this phase [46] [45].

This hierarchical structure ensures that the final performance score reported from the outer loop is a true estimate of generalization error, as it is derived from data that played no role in selecting the model's configuration [48].

Workflow Diagram of Nested Cross-Validation

The following diagram illustrates the two-layer structure of the nested cross-validation process.

Comparative Analysis: Nested vs. Non-Nested Cross-Validation

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Empirical studies across various domains, including healthcare and genomics, consistently demonstrate that non-nested cross-validation produces optimistically biased performance estimates. The following table summarizes key findings from the literature.

Table 1: Empirical Comparison of Nested and Non-Nested Cross-Validation Performance

| Study / Domain | Metric | Non-Nested CV Performance | Nested CV Performance | Bias Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tougui et al. (2021) [46] | AUROC | Higher estimate | Realistic estimate | 1% to 2% |

| Area Under Precision-Recall (AUPR) | Higher estimate | Realistic estimate | 5% to 9% | |

| Wilimitis et al. (2023) [49] | Generalization Error | Over-optimistic, biased | Lower, more realistic | Significant |

| Ghasemzadeh et al. (2024) [46] | Statistical Power & Confidence | Lower | Up to 4x higher confidence | Notable |

| Usher Syndrome miRNA Study [50] | Classification Accuracy | Prone to overfitting | 97.7% (validated) | Critical for robustness |

Procedural and Conceptual Differences

The quantitative differences stem from fundamental methodological flaws in the non-nested approach.

Table 2: Conceptual and Practical Differences Between Validation Methods

| Aspect | Non-Nested Cross-Validation | Nested Cross-Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Core Procedure | Single data split for both tuning and evaluation. | Two separate, layered loops for tuning and evaluation. |

| Information Leakage | High risk; test data influences hyperparameter choice. | Prevented by design; outer test set is completely hidden from tuning. |

| Performance Estimate | Optimistically biased, unreliable for generalization. | Nearly unbiased, realistic estimate of true performance [46]. |

| Computational Cost | Lower. | Significantly higher (e.g., K x L models for K outer and L inner folds). |

| Model Selection | Vulnerable to selection bias, overfits the test set. | Robust model selection; identifies models that generalize better. |

| Suitability for Small Datasets | Poor, high variance and bias. | Recommended, makes efficient and rigorous use of limited data [50]. |

Implementing Nested Cross-Validation in Genomic Cancer Research

Experimental Protocol for Genomic Classifiers

Implementing NCV for a genomic cancer classifier involves a sequence of critical steps to ensure biological relevance and statistical rigor.

Dataset Preparation and Partitioning:

- Subject-Wise Splitting: Given the correlated nature of genomic measurements from the same patient, splits must be performed subject-wise (or patient-wise) rather than record-wise. This ensures all samples from a single patient are contained within either the training or test set of a given fold, preventing inflated performance due to patient re-identification [49].

- Stratification: For classification tasks, it is crucial to use stratified k-fold in both the inner and outer loops. This preserves the percentage of samples for each class (e.g., cancer vs. normal) across all folds, which is especially important for imbalanced genomic datasets [49].

Inner Loop Workflow (Hyperparameter Tuning):

- The development set from the outer loop is used for an inner ( L )-fold cross-validation.

- A predefined hyperparameter search space (e.g., using GridSearchCV or RandomizedSearchCV) is explored. For a Random Forest classifier, this might include

max_depth,n_estimators, andmax_features. - A model is trained for each hyperparameter combination on the inner training folds and evaluated on the inner validation folds.

- The set of hyperparameters that yields the best average performance across the inner folds is selected.

Outer Loop Workflow (Performance Evaluation):

- Using the optimal hyperparameters found in the inner loop, a final model is trained on the entire development set.

- This model is then evaluated on the held-out outer test fold, which has not been used in any way during the tuning process. A performance metric (e.g., AUC, Accuracy) is recorded.

- This process repeats for each of the ( K ) outer folds.

Final Model and Reporting:

- The final output of NCV is not a single model, but a distribution of ( K ) performance scores. The mean and standard deviation of these scores provide a robust estimate of the model's generalization capability and its uncertainty [48].

- To deploy a model, one can refit it on the entire dataset using the hyperparameters that performed best on average during the NCV process.

Data Partitioning Strategy Diagram

The following diagram details the data partitioning strategy for a single outer fold, highlighting the strict separation of training, validation, and test data.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Successfully implementing nested cross-validation in genomic research requires a combination of computational tools and rigorous statistical practices.

Table 3: Essential Tools and Practices for Rigorous Genomic Classifier Validation

| Tool / Practice | Category | Function in Nested CV | Example Technologies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stratified K-Fold | Data Partitioning | Ensures class ratios are preserved in all training/test splits, critical for imbalanced cancer datasets. | StratifiedKFold (scikit-learn) |

| Group K-Fold | Data Partitioning | Enforces subject-wise splitting by grouping all samples from the same patient to prevent data leakage. | GroupKFold (scikit-learn) |

| Hyperparameter Optimizer | Model Tuning | Automates the search for optimal model parameters within the inner loop. | GridSearchCV, RandomizedSearchCV (scikit-learn), Optuna |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) | Infrastructure | Manages the high computational cost of NCV through parallelization across multiple CPUs/GPUs. | SLURM, Multi-GPU frameworks, Cloud computing [48] |

| Nested CV Code Framework | Software | Provides a reusable, scalable structure for implementing the complex nested validation process. | NACHOS framework [48], custom scripts in Python/R |