Cross-Validation of QSAR Models for Cancer Cell Lines: A Foundational Guide from Development to Clinical Application

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical role of cross-validation in Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling for anticancer drug discovery.

Cross-Validation of QSAR Models for Cancer Cell Lines: A Foundational Guide from Development to Clinical Application

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical role of cross-validation in Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling for anticancer drug discovery. It covers the foundational principles of model development against diverse cancer cell lines, explores advanced machine learning methodologies and their application in rational drug design, addresses key troubleshooting and optimization strategies for robust model performance, and establishes rigorous external validation and comparative analysis frameworks. By synthesizing current best practices and emerging trends, this guide aims to enhance the reliability and predictive power of QSAR models, thereby accelerating the development of novel oncology therapeutics.

Foundations of QSAR Modeling in Oncology: From Cell Line Selection to Core Principles

The Critical Role of Cancer Cell Line Selection in QSAR Model Specificity

In the field of cancer drug discovery, Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models are indispensable computational tools for predicting the biological activity of chemical compounds. These models correlate molecular descriptors—quantitative representations of a compound's structural and chemical properties—with its biological activity, enabling the virtual screening and prioritization of potential drug candidates [1]. However, the predictive performance and applicability of these models are not universal; they are profoundly influenced by the biological context in which the activity data is generated. Among the various experimental factors, the selection of the specific cancer cell line used to generate the training data is a critical determinant of model specificity and translational relevance [2]. A model trained on one cell line may perform poorly when applied to data from another, due to the unique genomic, proteomic, and metabolic landscape of each cellular model. This article examines how variable selection of cancer cell lines impacts QSAR model performance, explores the underlying biological mechanisms, and provides a comparative guide for researchers to navigate these critical decisions.

The Impact of Cell Line Selection on Model Performance

The genetic and molecular heterogeneity between different cancer cell lines directly translates into significant variations in their response to chemical compounds. Consequently, a QSAR model is not a generic predictor of anti-cancer activity but is, in fact, a highly specific predictor of activity within a particular biological context—a context defined by the cell line used for training.

Evidence from large-scale comparative studies underscores this point. One extensive analysis developed QSAR models for 266 anti-cancer compounds tested against 29 different cancer cell lines [2]. The statistical robustness of these models, measured by the coefficient of determination (R²), varied considerably across cell lines from different cancer types. For instance, models built for nasopharyngeal cancer cell lines achieved an average R² of 0.90, while those for melanoma cell lines averaged 0.81 [2]. This demonstrates that the very reliability of a QSAR model is intrinsically linked to the cellular origin of its training data.

Furthermore, the predictive power of a model is closely tied to the variability of the response within the training data. Models built to predict dependency scores for genes with highly variable effects across cell lines (e.g., the tumor suppressor gene TP53) have been shown to achieve significantly higher accuracy (Pearson correlation ρ = 0.62) [3]. This principle extends to drug sensitivity; cell lines with diverse genetic backgrounds that cause a wide spread in IC₅₀ values for a set of compounds provide more informative data for building robust QSAR models.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of QSAR Models Across Different Cancer Cell Lines

| Cancer Type | Example Cell Line(s) | Model Performance (R²) | Key Influencing Descriptors | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasopharyngeal | KB, CNE2 | Average R² = 0.90 | Quantum chemical, electrostatic descriptors [2] | [2] |

| Melanoma | SK-MEL-5, A375, B16F1 | Average R² = 0.81 | Topological descriptors, 2D-autocorrelation descriptors [2] [4] | [2] [4] |

| Breast Cancer | MCF-7, MB-231 | Varies by compound scaffold | charge-based, valency-based descriptors [2] | [1] [2] [5] |

| Lung Cancer | A549 | Varies by compound scaffold | --- | [2] [6] |

| Hepatocellular Carcinoma | HepG2 | Good predictive performance (R: 0.89-0.97) | Polarizability, van der Waals volume, dipole moment [7] | [7] |

Underlying Biological Mechanisms Driving Model Specificity

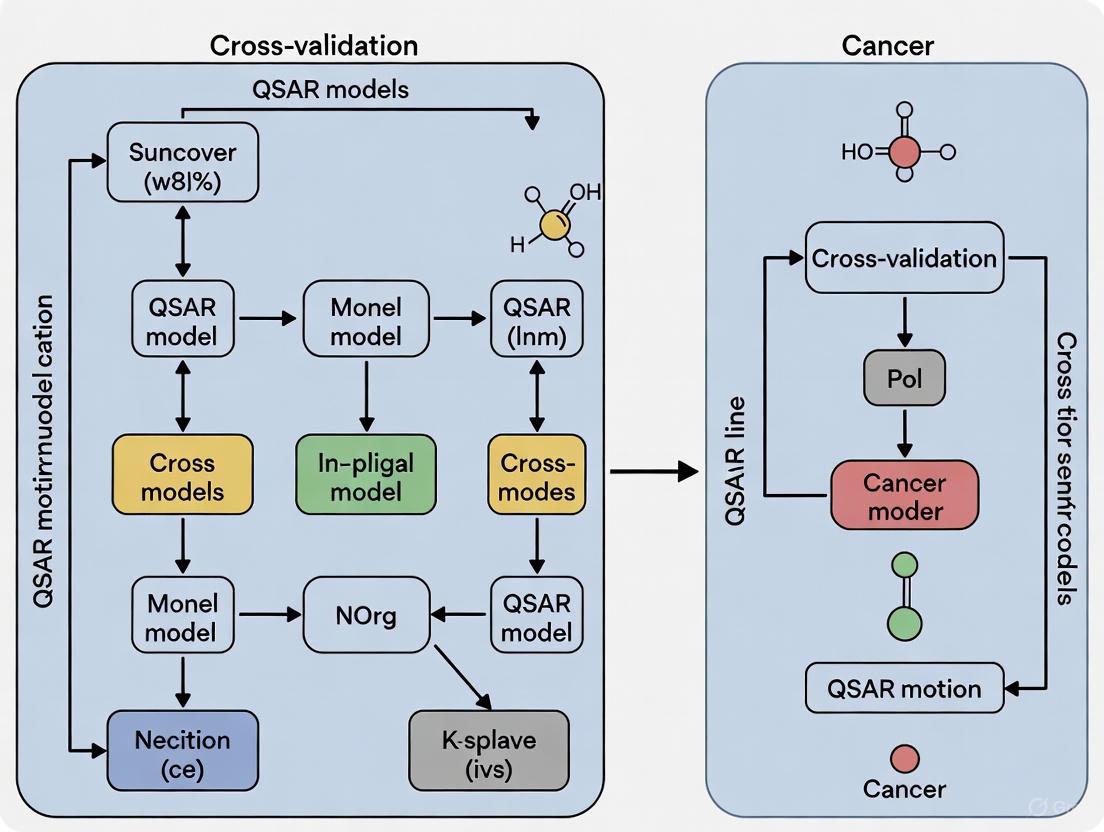

The disparity in QSAR model performance across different cell lines is not arbitrary; it is rooted in the distinct molecular pathologies of each cancer type and cell line. The following diagram illustrates the logical pathway through which fundamental cell line characteristics dictate the critical features of a resulting QSAR model.

The biological rationale behind this pathway can be broken down into two key areas:

Mutational Status and Signaling Pathways: The presence of specific driver mutations dictates which signaling pathways are critical for cell survival, making the cell line uniquely sensitive or resistant to compounds that target those pathways. For example, the SK-MEL-5 melanoma cell line harbors the B-Raf V600E mutation, which constitutively activates the MAPK signaling pathway [4]. A QSAR model trained on this cell line will inherently learn structural features of compounds that interact with this specific pathogenic context. Similarly, the search for KRAS inhibitors is specifically targeted against cell lines or tumors with KRAS mutations, a common driver in lung cancer [6]. The molecular descriptors selected in a robust QSAR model for such inhibitors will reflect the properties needed to interact with the unique topology of the mutant KRAS protein.

Lineage and Tissue of Origin: The tissue from which a cell line is derived defines its baseline gene expression program. A cell line from a hepatic origin (e.g., HepG2) will express a different set of enzymes and transporters compared to a cell line of neuronal origin, affecting drug metabolism, uptake, and overall sensitivity [7]. QSAR models for liver cancer agents, like those involving naphthoquinone derivatives, highlight the importance of descriptors related to polarizability (MATS3p), van der Waals volume (GATS5v), and dipole moment, which influence compound interaction with cellular targets specific to that environment [7].

Experimental Protocols for Cross-Cell Line QSAR Modeling

Developing reliable and interpretable QSAR models requires a rigorous and standardized workflow. The following diagram and detailed protocol outline the key steps, from data collection to model validation, with a particular emphasis on accounting for cell line-specific factors.

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Step 1: Data Curation and Cell Line Selection

- Source experimental bioactivity data (e.g., IC₅₀, GI₅₀) from reliable public databases such as the GDSC2 (Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer) [1] [5], PubChem [4], or ChEMBL [6].

- Intentionality select cell lines to ensure biological diversity. This includes choosing lines from different cancer types (e.g., breast, lung, melanoma), with different mutational statuses (e.g., KRAS mutant vs. wild-type), and from different lineages. This strategy allows for direct comparison of model performance and descriptor relevance across contexts.

Step 2: Molecular Descriptor Calculation

- Compute a comprehensive set of molecular descriptors for all compounds in the dataset. These quantitatively represent the structural and chemical features of the molecules.

- Commonly Used Descriptors:

- Tools: Utilize software like PaDELPy [1] [5], Dragon [4], or ChemoPy [6] for automated descriptor calculation.

Step 3: Data Pre-processing and Feature Reduction

- Clean Data: Remove descriptors with zero variance, near-constant values, or a high proportion of missing values [4] [6].

- Address Skewness: Apply transformations (e.g., Box-Cox, logarithmic) to normalize the distribution of biological activity values and descriptors [1].

- Reduce Multicollinearity: Eliminate highly correlated descriptors (e.g., Pearson’s |r| > 0.95) to improve model stability and interpretability [6].

- Dimensionality Reduction: Use techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to compress the descriptor space while retaining most of the original variance (e.g., 95%) [1].

Step 4: Model Training with Multiple Algorithms

- Partition the pre-processed data into training, testing, and validation sets (common splits are 60:20:20 [5] or 70:30 [6]).

- Train and compare a diverse set of machine learning algorithms to identify the best performer for your specific dataset. Common high-performing algorithms include:

- Deep Neural Networks (DNN): Excelled in a breast cancer combination therapy study, achieving an R² of 0.94 [1] [5].

- Random Forest (RF): Often provides robust performance and feature importance metrics [4] [6].

- Partial Least Squares (PLS): A linear method that works well with highly correlated descriptors [6].

- XGBoost: A powerful gradient-boosting algorithm [6].

Step 5: Model Validation and Defining the Applicability Domain

- Validation: Rigorously assess model performance using the test set. Key metrics include R² (Coefficient of Determination), RMSE (Root Mean Square Error), and MAE (Mean Absolute Error). Use cross-validation to ensure stability [1] [6].

- Applicability Domain (AD): Critically, define the chemical space where the model can make reliable predictions. The Mahalanobis Distance is a common method to flag new compounds that are structurally dissimilar to the training set and for which predictions may be unreliable [6].

Comparative Performance of Machine Learning Algorithms

The choice of machine learning algorithm is a key factor in determining the predictive power of a QSAR model. However, the optimal algorithm can vary depending on the dataset size, descriptor types, and the biological endpoint being predicted. The following table synthesizes findings from multiple studies to provide a comparative guide.

Table 2: Comparison of Machine Learning Algorithms in QSAR Modeling for Cancer Research

| Algorithm | Reported Performance | Advantages | Ideal Use Case | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deep Neural Network (DNN) | R² = 0.94 (Breast Cancer) [1] [5] | High predictive power; capable of modeling complex non-linear relationships. | Large datasets with complex structure-activity relationships [8]. | [1] [8] [5] |

| Random Forest (RF) | R² = 0.796 (KRAS inhibitors) [6]; High PPV for melanoma [4] | Robust, less prone to overfitting; provides feature importance. | General-purpose modeling, especially with diverse molecular descriptors [4]. | [4] [6] |

| Partial Least Squares (PLS) | R² = 0.851 (KRAS inhibitors) [6] | Effective for highly correlated descriptors; a stable linear method. | Smaller datasets or when descriptor collinearity is high [6]. | [6] |

| XGBoost | Comparable top performer in comparative studies [1] | High accuracy and speed; handles mixed data types well. | Competitions and large-scale virtual screening [1]. | [1] |

| Genetic Algorithm-MLR (GA-MLR) | R² = 0.677 (KRAS inhibitors) [6] | High interpretability; generates a simple linear equation. | When model interpretability and descriptor insight are prioritized [6]. | [6] |

Building a context-specific QSAR model requires a suite of computational and biological reagents. The following table details key resources and their functions in the workflow.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Resources for Cell Line-Specific QSAR Modeling

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in QSAR | Relevance to Cell Line Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|

| GDSC2 Database | Bioactivity Database | Provides curated drug sensitivity data (IC₅₀) for a wide range of compounds across many cancer cell lines [1] [5]. | Enables the selection of specific cell lines (e.g., breast cancer panels) for model training and comparison. |

| PubChem BioAssay | Bioactivity Database | A public repository of chemical compounds and their bioactivities, including cytotoxicity data on specific cell lines like SK-MEL-5 [4]. | Source of experimental data for building models targeting particular cell lines. |

| PaDEL Descriptor Software | Descriptor Calculator | Computes molecular descriptors and fingerprints from chemical structures directly from SMILES strings [1] [5]. | Generates the independent variables (features) for the QSAR model, independent of cell line. |

| Dragon Software | Descriptor Calculator | Generates a very wide array of molecular descriptors (e.g., topological, 3D, constitutional) for small molecules [4]. | Allows for the comprehensive numerical representation of chemical structures. |

| SK-MEL-5 Cell Line | Biological Reagent | A human melanoma cell line with B-Raf V600E mutation, used in in vitro cytotoxicity assays [4]. | The biological context for training a melanoma-specific QSAR model. |

| KRAS Mutant Cell Lines | Biological Reagent | Lung cancer cell lines with specific KRAS mutations (e.g., G12C) [6]. | Essential for generating activity data to build target-specific QSAR models for mutant KRAS inhibition. |

| ChemoPy Package | Programming Tool | A Python package for calculating structural and physicochemical features of molecules [6]. | Integrates descriptor calculation into a customizable machine learning pipeline. |

The development of predictive QSAR models in oncology is a powerful but context-dependent endeavor. The selection of the cancer cell line is not merely a procedural detail but a fundamental choice that dictates the biological reality the model will learn. As evidenced by comparative studies, model performance, the relevance of molecular descriptors, and ultimately the translational potential of the predictions are all inextricably linked to the cellular model. Researchers must therefore abandon the notion of a universal "anti-cancer" QSAR model. Instead, the future lies in building a portfolio of highly specific, well-validated models, each tailored to a defined genetic or histological context. This requires intentional cell line selection, rigorous cross-validation, and a clear definition of the model's applicability domain. By embracing this specificity, QSAR modeling will continue to evolve as a more precise and reliable tool, accelerating the discovery of targeted therapies for diverse cancer types.

Table of Contents

- Introduction to QSAR Fundamentals

- Core Components of a QSAR Model

- A Protocol for Developing and Validating a Predictive QSAR Model

- Visualizing the QSAR Workflow

- The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Software

- Case Study: QSAR in Cancer Research for FGFR-1 Inhibitors

- Conclusion and Future Perspectives

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling is a cornerstone of computational chemistry and drug discovery. These are regression or classification models that relate a set of "predictor" variables (X) to the potency of a response variable (Y), which is typically a biological activity [9]. The fundamental premise is that the biological activity of a compound can be predicted from its molecular structure, quantified using numerical representations known as descriptors [9] [10]. The "chemical space" refers to the multi-dimensional universe defined by these descriptors, encompassing all possible molecules and their properties.

The broader application of these principles, known as QSPR (Quantitative Structure-Property Relationship), is used to model physicochemical properties and has been extended to specialized areas like toxicity (QSTR) and biodegradability (QSBR) [9]. The reliability of any QSAR model is paramount, especially in a regulatory context or when guiding expensive synthetic experiments, and is established through rigorous validation and defining its Applicability Domain (AD)—the region of chemical space in which the model can make reliable predictions [9] [11] [12].

Core Components of a QSAR Model

A QSAR model is built upon three essential pillars: molecular descriptors, bioactivity values, and the chemical space they collectively define.

Molecular Descriptors: The Predictor Variables (X)

Molecular descriptors are numerical values that quantify a molecule's structural, physicochemical, or topological characteristics [10]. They serve as the independent variables (X) in a QSAR model. Descriptors can be categorized as follows:

- Table 1: Categories of Molecular Descriptors

Descriptor Category Description Examples Relevance in Cancer Drug Design Topological Based on 2D molecular graph theory, encoding atom connectivity [10]. Wiener index, Zagreb index, Balaban index [10]. Modeling interactions dependent on molecular size and branching. Geometric Derived from the 3D geometry of a molecule [10]. Principal moments of inertia, molecular volume, surface areas [10]. Critical for understanding shape complementarity with a protein binding pocket. Electronic Describe the electronic distribution within a molecule [13]. Dipole moment, atomic partial charges, HOMO/LUMO energies [13]. Predicting interactions with key amino acids in a target enzyme (e.g., FGFR-1). Physicochemical Represent bulk properties influencing absorption and distribution [10]. Partition coefficient (LogP), molar refractivity, polarizability [13]. Optimizing pharmacokinetic properties like cell permeability and bioavailability.

Feature selection is a critical step to avoid overfitting. Methods like Genetic Algorithms (GA) and Wrapper Methods are used to select a subset of relevant descriptors, improving model interpretability and predictive performance [10].

Bioactivity Values: The Response Variable (Y)

The response variable (Y) is a quantitative measure of biological potency. In anticancer research, this is most commonly the pIC₅₀ value, which is the negative logarithm of the molar concentration of a compound required to inhibit 50% of a specific biological activity (e.g., enzyme inhibition or cell proliferation) [14]. A higher pIC₅₀ indicates a more potent compound. Using pIC₅₀ normalizes the data and provides a continuous variable suitable for linear regression modeling.

The Chemical Space and the Applicability Domain (AD)

The "chemical space" is the multi-dimensional space defined by the descriptors used in a model. The Applicability Domain (AD) is a crucial concept defining the region within this chemical space where the model's predictions are reliable [9] [12]. A model is only valid for compounds that are sufficiently similar to those in its training set. Predictions for compounds outside the AD are considered unreliable. Methods to define the AD include distance-to-model metrics and leverage analysis [11].

A Protocol for Developing and Validating a Predictive QSAR Model

The following protocol, synthesized from recent studies, outlines the essential steps for building a robust QSAR model [9] [14].

Phase 1: Data Preparation and Curation

- Step 1: Data Set Selection. Compile a dataset of compounds with experimentally measured biological activities (e.g., pIC₅₀). For example, public repositories like the ChEMBL database can be used [14].

- Step 2: Calculation of Molecular Descriptors. Use software tools (e.g., Alvadesc, RDKit, Mordred) to calculate a wide array of molecular descriptors for every compound in the dataset [14] [15] [10].

- Step 3: Data Set Division. Randomly split the curated dataset into a training set (~70-80%) for model construction and a test set (~20-30%) for external validation [14].

Phase 2: Model Construction and Internal Validation

- Step 4: Feature Selection. Apply feature selection techniques (e.g., Genetic Algorithms) on the training set to identify the most relevant descriptors, preventing model overfitting [10].

- Step 5: Model Training. Use a statistical or machine learning algorithm (e.g., Multiple Linear Regression - MLR, Partial Least Squares - PLS, support vector machines) on the training set to build the model that correlates the selected descriptors (X) with the bioactivity (Y) [9] [14].

- Step 6: Internal Validation. Assess the model's robustness using techniques like 10-fold cross-validation. Key metrics include the squared correlation coefficient (R² or q² for cross-validation), which should be greater than 0.6 for an acceptable model [9] [14].

Phase 3: External Validation and Experimental Testing

- Step 7: External Validation. Use the untouched test set to evaluate the model's predictive power. The R² for the test set predictions is a key indicator of real-world performance [14].

- Step 8: Experimental Verification. Synthesize or acquire new, predicted-active compounds and validate their activity using in vitro assays (e.g., MTT assay for cell viability, wound healing assay for migration) [14]. This step confirms the practical utility of the model.

Visualizing the QSAR Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow of QSAR model development and validation, culminating in experimental testing.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Software

This table details key resources used in the development and experimental validation of QSAR models, as featured in the cited research.

- Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for QSAR Studies

Item Name Function / Description Example Use in Protocol Alvadesc Software Calculates a wide range of molecular descriptors from chemical structures [14]. Phase 1, Step 2: Generating predictor variables (X) for the dataset. ChEMBL Database A large, open-access database of bioactive molecules with curated bioactivity data [14]. Phase 1, Step 1: Sourcing chemical structures and bioactivity values (Y). Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) A statistical algorithm used to construct a linear model between descriptors and activity [14] [13]. Phase 2, Step 5: Building the initial predictive model. MTT Assay Kit A colorimetric assay for assessing cell metabolic activity, used to determine cytotoxicity (IC₅₀) [14]. Phase 3, Step 8: Experimental validation of predicted compound activity on cancer cell lines. Molecular Docking Software Computationally simulates how a small molecule binds to a protein target [14]. Used to provide further in silico support for the model's predictions by analyzing binding modes.

Case Study: QSAR in Cancer Research for FGFR-1 Inhibitors

A recent study exemplifies the application of these core principles to a critical cancer target [14]. The study aimed to develop a predictive QSAR model for inhibitors of Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor 1 (FGFR-1), a target associated with lung and breast cancers.

Methodology:

- Data and Descriptors: A dataset of 1,779 compounds from ChEMBL was curated. Molecular descriptors were calculated using Alvadesc software and refined with feature selection [14].

- Model Construction: A Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) model was constructed, resulting in a robust model with a training set R² of 0.7869 [14].

- Validation: The model was rigorously validated through 10-fold cross-validation and an external test set (R² = 0.7413). Furthermore, the model's predictions were supported by molecular docking and dynamics simulations [14].

- Experimental Cross-Validation: The model identified Oleic acid as a promising inhibitor. In vitro experiments on A549 (lung cancer) and MCF-7 (breast cancer) cell lines using MTT, wound healing, and clonogenic assays confirmed significant anticancer activity and selectivity, with low cytotoxicity on normal cell lines [14]. This provided a strong correlation between predicted and observed pIC₅₀ values.

Key Descriptors and Biological Insight: The study demonstrated that descriptors quantifying properties like polarizability, van der Waals volume, and electronegativity were critical for predicting FGFR-1 inhibitory activity. This provides medicinal chemists with tangible guidance for optimizing molecular structures.

The core principles of QSAR—linking numerical descriptors to bioactivity within a defined chemical space—provide a powerful framework for rational drug design. The case study on FGFR-1 inhibitors highlights how a rigorously developed and validated model, following a structured protocol, can successfully guide the identification of novel anticancer agents. The integration of computational predictions with experimental validation remains the gold standard for establishing model credibility.

Future directions in QSAR involve the increasing use of deep learning which can automatically learn relevant features from molecular structures or images, potentially uncovering complex patterns beyond traditional descriptors [16]. Furthermore, methods like q-RASAR are emerging, which merge traditional QSAR with similarity-based read-across techniques to enhance predictive reliability [9]. As these methodologies mature, they will continue to refine the precision and accelerate the pace of anticancer drug discovery.

The development of anticancer drugs is a complex process, often hampered by tissue-specific biological responses that can limit the generalizability of computational models. Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling serves as a powerful computational tool in early drug discovery, predicting the biological activity of compounds from their chemical structure [4]. However, most existing QSAR studies target single cancer cell lines, creating a knowledge gap in understanding pan-cancer activity profiles [2]. This case study addresses this limitation by systematically developing and validating foundational QSAR models across three distinct carcinoma types: HepG2 (hepatocellular carcinoma), A549 (lung carcinoma), and MOLT-3 (T-lymphoblastic leukemia). The research is framed within a broader thesis on cross-validation methodologies for QSAR models, emphasizing the critical importance of model robustness and transferability across different cancer lineages.

Experimental Design and Methodologies

Cell Line Selection and Biological Rationale

The selection of these three specific cell lines provides a representative spectrum of human cancers, encompassing carcinomas derived from different tissue origins (liver, lung, and blood). This diversity is crucial for evaluating the broader applicability of QSAR models beyond a single cancer type.

- HepG2 (Hepatocellular Carcinoma): This cell line represents one of the most common types of liver cancer and is widely used in hepatotoxicity and anticancer drug screening studies [7] [17].

- A549 (Lung Carcinoma): A non-small cell lung cancer model, A549 is characterized by its expression of the KRAS mutation, making it a relevant model for a significant subset of lung cancers [7] [17].

- MOLT-3 (T-Lymphoblastic Leukemia): As a lymphoblastic leukemia cell line, MOLT-3 provides insights into blood-borne cancers, which often exhibit different drug sensitivity profiles compared to solid tumors [7] [17].

Cytotoxic Activity Assay Protocols

A standardized experimental protocol is essential for generating consistent and comparable bioactivity data across different cell lines. The methodologies cited below form the cornerstone for generating the activity data used in QSAR model construction.

Table 1: Standardized Assay Protocols for Cytotoxic Activity Measurement

| Cell Line | Assay Type | Culture Medium | Seeding Density | Incubation Time | Key Readout |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HepG2, A549, MRC-5 | MTT Assay [7] | DMEM or Hamm's F12 + 10% FBS [7] | 5x10³ - 2x10⁴ cells/well [7] | 48 hours [7] | Absorbance at 550 nm [7] |

| MOLT-3 | XTT Assay [7] | RPMI-1640 + 10% FBS [7] | N/A (suspension culture) [7] | 48 hours [7] | Absorbance at 550 nm [7] |

| General Protocol | Data points are typically performed in replicates, and IC₅₀ values (concentration causing 50% growth inhibition) are calculated from dose-response curves. Compounds with IC₅₀ > 50 μM are often classified as non-cytotoxic [7]. |

Dataset Curation for QSAR Modeling

The integrity of a QSAR model is directly dependent on the quality of the input data. The following workflow outlines the critical steps in dataset preparation, from biological testing to model-ready data.

The process begins with experimental bioactivity testing (e.g., GI₅₀ or IC₅₀ determination) against the target cell lines [7] [4]. Data standardization follows, which may include removing duplicates and averaging replicate values [4]. Subsequently, chemical structures (often from canonical SMILES) are standardized using tools like ChemAxon Standardizer to ensure consistency [4]. The crucial step of molecular descriptor calculation then takes place, generating quantitative representations of the molecules using software such as Dragon or PaDEL [4] [5]. Finally, the dataset is split into training and test sets, typically in a 70:30 to 80:20 ratio, to allow for model building and subsequent validation [4].

QSAR Model Construction and Performance Analysis

Machine Learning Algorithms and Descriptor Selection

The construction of predictive QSAR models involves the careful selection of machine learning algorithms and relevant molecular descriptors.

- Algorithm Selection: Studies have successfully employed a range of algorithms. Random Forest (RF) has shown strong performance, with models achieving high Positive Predictive Values (PPV > 0.85) for melanoma cell lines [4]. Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) is also widely used, providing good predictive performance (R training set = 0.89-0.97) for naphthoquinone derivatives [7]. For more complex relationships, Deep Neural Networks (DNN) have demonstrated exceptional performance, achieving an R² of 0.94 in combinational therapy models for breast cancer [5].

- Descriptor Analysis: Not all descriptors contribute equally. Research analyzing 29 different cancer cell lines found that quantum chemical descriptors (e.g., charge, polarizability) are the most important class, followed by electrostatic, constitutional, and topological descriptors [2]. Specifically, for 1,4-naphthoquinones, polarizability (

MATS3p), van der Waals volume (GATS5v), and dipole moment were key features influencing anticancer activity [7]. It is often observed that models with 3 descriptors can be sufficient for good correlation, avoiding the overfitting associated with more complex models [2].

Comparative Model Performance Across Carcinoma Lines

The true test of a foundational model lies in its performance across diverse biological systems. The following table summarizes the predictive performance of QSAR models built for the HepG2, A549, and MOLT-3 cell lines, based on studies of triazole and naphthoquinone derivatives.

Table 2: Cross-Carcinoma QSAR Model Performance Comparison

| Cancer Cell Line | Cancer Type | Example Compound Series | Best Model Performance (Reported) | Key Influencing Descriptors/Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HepG2 | Hepatocellular Carcinoma | 1,2,3-Triazoles [17] | RCV: 0.80, RMSECV: 0.34 [17] | nR=O, nR-CR, lipophilicity, steric properties [17] |

| A549 | Lung Carcinoma | 1,2,3-Triazoles [17] | RCV: 0.60, RMSECV: 0.45 [17] | nR=O, nR-CR, lipophilicity, steric properties [17] |

| MOLT-3 | T-Lymphoblastic Leukemia | 1,2,3-Triazoles [17] | RCV: 0.90, RMSECV: 0.21 [17] | nR=O, nR-CR, lipophilicity, steric properties [17] |

| All Three Lines | Diverse Carcinomas | 1,4-Naphthoquinones [7] | R training: 0.89-0.97, R testing: 0.78-0.92 [7] | Polarizability, van der Waals volume, dipole moment [7] |

Abbreviations: RCV: Cross-validated Correlation Coefficient; RMSECV: Root Mean Square Error of Cross-Validation.

The data reveals a critical finding: the predictive performance of a QSAR model is highly dependent on the specific cancer cell line. For instance, in the study of triazole derivatives, the model for the MOLT-3 leukemia cell line (RCV = 0.90) was significantly more robust than the model for the A549 lung cancer cell line (RCV = 0.60), despite using the same set of molecular descriptors [17]. This underscores the impact of cell line-specific biological contexts on compound activity.

Framework for QSAR Model Validation

Ensuring that a QSAR model is reliable and not the result of chance correlation requires a rigorous validation framework. The following diagram outlines the key components of this process.

This framework consists of four pillars. Internal validation assesses model stability, often through techniques like Leave-One-Out (LOO) or k-fold cross-validation, which calculates metrics like RCV and Q² [17]. External validation is the most crucial step, evaluating the model's predictive power on a completely independent set of compounds that were not used in model training [7] [4]. Y-Scrambling is a sanity check where the model is rebuilt with randomly shuffled activity data; a significant drop in performance confirms the model is not based on chance correlation [4]. Finally, defining the Applicability Domain (AD) is essential to identify the region of chemical space where the model's predictions are reliable, preventing extrapolation beyond its scope [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

A successful QSAR modeling project relies on a suite of specialized software tools and reagents. The following table details key solutions used in the featured experiments and the broader field.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools

| Category | Item / Software | Primary Function | Specific Application in Case Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bioassay Reagents | MTT/XTT Reagents [7] | Measure cell viability and proliferative inhibition. | Cytotoxic activity determination for adherent (MTT) and suspension (XTT) cell lines [7]. |

| Cell Culture | DMEM, RPMI-1640, F-12 Media [7] | Provide optimized nutrients and environment for specific cell line growth. | Culture of HepG2 (DMEM), MOLT-3 (RPMI-1640), and A549/HuCCA-1 (F-12) [7]. |

| Descriptor Calculation | Dragon [4] | Calculates thousands of molecular descriptors from chemical structures. | Used to generate 13 blocks of descriptors (e.g., topological, 2D-autocorrelation) for model building [4]. |

| Descriptor Calculation | PaDEL [18] [5] | An open-source alternative for calculating molecular descriptors and fingerprints. | Used in large-scale studies to compute fingerprints for classifying anticancer molecules [18]. |

| Cheminformatics | ChemAxon Standardizer [4] | Standardizes chemical structures (e.g., neutralization, aromatization) to ensure consistency. | Preprocessing of canonical SMILES from PubChem before descriptor calculation [4]. |

| Machine Learning | R (rminer, mlr packages) [4] | Statistical computing and environment for building and evaluating machine learning models. | Implementation of RF, SVM, and other classifiers for QSAR model development [4]. |

| Machine Learning | Python (Scikit-learn) [5] | A versatile programming language with extensive libraries for machine learning. | Used for developing DNN and other ML-based QSAR models [5]. |

| Chemical Visualization | SAMSON [19] | A molecular modeling platform with advanced visualization and color-coding capabilities. | Aiding in the interpretation of molecular properties and QSAR results through intuitive visual feedback [19]. |

This case study demonstrates a robust framework for building and validating foundational QSAR models across three biologically diverse carcinoma cell lines. The findings confirm that while shared molecular descriptors (e.g., polarizability, steric volume) can govern anticancer activity across cell lines, the predictive performance of a model is inherently context-dependent, varying significantly with the cellular environment [7] [17]. The cross-validation thesis underscores that models performing excellently on one cell line (e.g., MOLT-3) may show only moderate performance on another (e.g., A549), highlighting the danger of over-generalizing single-line models and the necessity for multi-target validation strategies.

Future research directions should focus on the development of hybrid models that integrate chemical descriptor data with genomic features of cancer cell lines to improve predictive accuracy and biological interpretability [18]. Furthermore, the adoption of advanced visualization tools like MolCompass for navigating chemical space and visually validating QSAR models will be crucial for identifying model weaknesses and "activity cliffs" [20] [21]. As the field moves towards the era of deep learning and Big Data, the combination of sophisticated algorithms, rigorous cross-carcinoma validation, and intuitive visual analytics will be paramount in accelerating the discovery of novel, broad-spectrum anticancer agents.

Identifying Key Molecular Descriptors Governing Anticancer Potency

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling represents a fundamental computational approach in modern anticancer drug discovery, establishing mathematical relationships between chemical structures and their biological activity against cancer targets [22]. These models operate on the principle that variations in molecular structure quantitatively determine variations in biological properties, enabling researchers to predict the potency of novel compounds before synthesis and biological testing [22]. In the context of anticancer research, QSAR has emerged as an indispensable tool for accelerating the identification and optimization of lead compounds, ranging from natural product derivatives to synthetically designed molecules [23] [22].

The predictive capability of QSAR models hinges on molecular descriptors—quantitative representations of structural and chemical properties that serve as model inputs. These descriptors encompass topological, geometric, electronic, and physicochemical characteristics that numerically encode specific aspects of molecular structure [5]. With the integration of machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) algorithms, QSAR modeling has evolved into a more powerful and accurate predictive tool, capable of handling complex, high-dimensional data to identify subtle structure-activity patterns that might escape conventional analysis [23] [5]. This review comprehensively examines key molecular descriptors governing anticancer potency, their performance across diverse cancer models, and advanced methodological frameworks for model development and validation.

Molecular Descriptor Classes in Anticancer QSAR Models

Fundamental Descriptor Categories

Molecular descriptors utilized in anticancer QSAR modeling can be categorized into distinct classes based on the structural and chemical properties they represent. Quantum chemical descriptors, derived from quantum mechanical calculations, include electronic properties such as atomic charges, molecular orbital energies, and dipole moments that influence drug-receptor interactions [22]. Electrostatic descriptors characterize the charge distribution and potential fields around molecules, playing crucial roles in binding affinity [22]. Topological descriptors encode molecular connectivity patterns through graph-theoretical indices, while constitutional descriptors represent basic structural features like atom and bond counts [22]. Geometrical descriptors capture spatial molecular arrangements, and conceptual DFT descriptors theoretically describe chemical reactivity [22].

Performance Comparison of Descriptor Classes

A comprehensive analysis of QSAR models across 29 cancer cell lines revealed the relative importance and predictive performance of different descriptor classes [22]. Charge-based descriptors appeared in approximately 50% of significant models, valency-based descriptors in 36%, and bond order-based descriptors in 28% of models [22]. The study demonstrated that quantum chemical descriptors consistently provided the strongest predictive power for anticancer activity, followed by electrostatic, constitutional, geometrical, and topological descriptors [22]. Conceptual DFT descriptors showed limited improvement in statistical quality for most models despite their computational intensity [22].

Table 1: Performance of Molecular Descriptor Classes in Anticancer QSAR Models

| Descriptor Class | Representative Examples | Frequency in Significant Models | Key Applications in Cancer Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum Chemical | HOMO/LUMO energies, atomic charges, dipole moments | Highest | 20 out of 39 models (approx. 50%) [22] |

| Electrostatic | Partial charges, electrostatic potential surfaces | High | Charge-based descriptors most frequent [22] |

| Constitutional | Molecular weight, atom counts, bond counts | Moderate | Found in 36% of models [22] |

| Topological | Connectivity indices, path counts | Moderate | Molecular graph representations [24] |

| Geometrical | Molecular volume, surface area | Moderate | 3D spatial descriptors [22] |

| Conceptual DFT | Chemical potential, hardness | Lower | Limited improvement in most models [22] |

Key Molecular Descriptors Across Cancer Types

Descriptors for Specific Cancer Targets

Research has identified distinct descriptor profiles associated with anticancer potency against various cancer types. For colon cancer targeting HT-29 cell lines, hybrid descriptors combining SMILES notation and hydrogen-suppressed molecular graphs (HSG) demonstrated exceptional predictive capability in models developed using the Monte Carlo method [24]. These optimal descriptors achieved remarkable validation metrics (R² = 0.90, IIC = 0.81, Q² = 0.89) when applied to chalcone derivatives [24].

In breast cancer research, specifically against MCF-7 cell lines, machine learning-driven QSAR models for flavone derivatives identified critical descriptors including electronic properties and substituent characteristics that significantly influenced cytotoxicity [23]. Random Forest models achieved high predictive accuracy (R² = 0.820 for MCF-7, R² = 0.835 for HepG2) using these descriptor sets [23].

For leukemia targeting K562 cell lines, studies on C14-urea tetrandrine compounds revealed three key descriptors: AST4p (a 2D autocorrelation descriptor), GATS8v (Geary autocorrelation of lag 8 weighted by van der Waals volume), and MLFER (a molecular linear free energy relation descriptor) [25]. The resulting QSAR model showed strong predictive power with R²train = 0.910 and R²test = 0.644 [25].

Pan-Cancer Descriptor Analysis

Comparative analysis across multiple cancer types reveals both universal and context-dependent descriptor significance. A comprehensive study modeling 266 compounds against 29 different cancer cell lines found that optimal model performance typically required only 3-5 carefully selected descriptors, with additional descriptors providing diminishing returns [22]. The performance of descriptor classes varied significantly across cancer types, with models for nasopharyngeal cancer achieving the highest average R² values (0.90), followed by melanoma models (average R² = 0.81) [22].

Table 2: Key Molecular Descriptors and Their Predictive Performance Across Cancer Types

| Cancer Type | Cell Line/Model | Most Significant Descriptors | Predictive Performance (R²) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colon Cancer | HT-29 | Hybrid SMILES-HSG descriptors [24] | R²_validation = 0.90 [24] |

| Breast Cancer | MCF-7 | Electronic, steric substituent descriptors [23] | R² = 0.820 [23] |

| Liver Cancer | HepG2 | SHAP-identified molecular descriptors [23] | R² = 0.835 [23] |

| Leukemia | K562 | AST4p, GATS8v, MLFER [25] | R²train = 0.910, R²test = 0.644 [25] |

| Nasopharyngeal | Multiple | Charge- and valency-based descriptors [22] | Average R² = 0.90 [22] |

| Melanoma | Multiple | Quantum chemical descriptors [22] | Average R² = 0.81 [22] |

Methodological Frameworks for Descriptor Identification

Machine Learning and Feature Selection Approaches

Modern QSAR methodologies employ sophisticated machine learning algorithms and feature selection techniques to identify the most relevant molecular descriptors. Genetic Function Algorithm (GFA) has proven effective for descriptor selection, as demonstrated in leukemia research where it identified three critical descriptors from a larger pool of potential variables [25]. Random Forest algorithms provide robust feature importance rankings through ensemble learning, successfully applied to flavone derivatives for breast and liver cancer models [23]. Deep Neural Networks (DNNs) have achieved exceptional performance (R² = 0.94) in combinational QSAR models for breast cancer, effectively capturing complex descriptor-activity relationships [5].

The Monte Carlo optimization method implemented in CORAL software offers an alternative approach using descriptor correlation weights (DCWs) derived from SMILES notation and molecular graphs [24]. This method has demonstrated particular utility for chalcone derivatives against colon cancer, with hybrid descriptors outperforming SMILES-only or graph-only approaches [24]. For combinatorial therapy prediction, studies have successfully calculated molecular descriptors for both anchor and library drugs using the Padelpy library, enabling the development of novel combinational QSAR models that account for drug interactions [5].

Validation Protocols and Applicability Domain

Robust validation frameworks are essential for establishing descriptor significance and model reliability. External validation using independent test sets remains the gold standard, with performance metrics including R²test, Q², and IIC (Index of Ideality of Correlation) [25] [24]. Cross-validation techniques (e.g., 5-fold cross-validation) assess model stability and prevent overfitting [23] [26]. Applicability domain (AD) analysis critically determines the structural space where models provide reliable predictions, addressing a fundamental limitation in QSAR modeling [27].

Recent research emphasizes that QSAR model reliability depends not only on statistical performance but also on transparent definition of applicability domains and chemical space coverage [27]. Studies investigating multiple QSAR models for carcinogenicity prediction have observed significant test-specificity and inconsistencies between models, highlighting the importance of applicability domain considerations and weight-of-evidence approaches when interpreting results [27].

Figure 1: Comprehensive QSAR model development workflow integrating descriptor calculation, machine learning, and rigorous validation protocols

Experimental Protocols and Computational Methodologies

Standard QSAR Development Pipeline

The development of robust QSAR models follows a systematic computational workflow beginning with data collection and curation. Researchers compile compound datasets with experimentally determined biological activities (e.g., IC₅₀ values) from reliable sources, ensuring structural diversity and activity range representation [24]. For anticancer applications, data typically originates from standardized assays like MTT assays measuring mitochondrial reduction in cancer cell lines [24].

Molecular structure optimization represents a critical preprocessing step, often performed using Density Functional Theory (DFT) methods at levels such as B3LYP/6-31G* to generate energetically minimized 3D structures [25]. Subsequent descriptor calculation employs specialized software including PaDEL, CORAL, or proprietary tools to generate comprehensive descriptor sets spanning multiple classes [25] [24] [5]. The resulting descriptor matrix undergoes feature selection using algorithms like Genetic Function Algorithm (GFA) or machine learning-based importance ranking to identify the most relevant variables [25].

Model building employs statistical or machine learning techniques including Multiple Linear Regression (MLR), Random Forest, or Deep Neural Networks to establish quantitative descriptor-activity relationships [23] [25] [5]. The final stage involves rigorous model validation through internal (cross-validation) and external (test set prediction) methods to assess predictive capability and generalizability [25] [24].

Advanced Integrative Approaches

Contemporary anticancer QSAR increasingly integrates complementary computational methods to enhance predictive accuracy and mechanistic understanding. Structure-based drug design combines QSAR with molecular docking to validate predicted activities through binding mode analysis, as demonstrated in studies targeting αβIII-tubulin isotype [26]. Molecular dynamics simulations provide additional validation of stability and interactions for predicted active compounds [26].

Combinational QSAR models represent a innovative extension, simultaneously modeling descriptor-activity relationships for drug pairs in combination therapies [5]. These approaches calculate molecular descriptors for both anchor and library drugs, then employ machine learning to predict combination effects across multiple cancer cell lines [5]. Multi-target QSAR models have also emerged for designing compounds against dual targets, such as HDAC/ROCK inhibitors for triple-negative breast cancer, incorporating both structure-based and ligand-based approaches [28].

Figure 2: Experimental QSAR validation protocol showing dataset division, model training, and comprehensive validation stages

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools and Resources for Anticancer QSAR Research

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| OECD QSAR Toolbox | Software | Chemical categorization, trend analysis, (Q)SAR model implementation [27] | Carcinogenicity prediction, hazard assessment [27] |

| Danish (Q)SAR Software | Online Database | Archive of model estimates from commercial, free, and DTU (Q)SAR models [27] | Carcinogenic potential prediction for pesticides and metabolites [27] |

| CORAL Software | Modeling Tool | QSAR modeling using Monte Carlo method with optimal descriptors [24] | SMILES-based QSAR for chalcone derivatives against colon cancer [24] |

| PaDEL-Descriptor | Descriptor Calculator | Calculation of molecular descriptors and fingerprints from chemical structures [25] [26] [5] | Generation of 797+ descriptors for machine learning-based QSAR [26] |

| AutoDock Vina | Docking Software | Structure-based virtual screening and binding affinity prediction [26] | Identification of natural inhibitors against αβIII-tubulin isotype [26] |

| GDSC2 Database | Data Resource | Drug sensitivity genomics data for cancer cell lines and drug combinations [5] | Combinational QSAR model development for breast cancer [5] |

| ZINC Database | Compound Library | Curated collection of commercially available compounds for virtual screening [26] | Natural compound screening for tubulin inhibitors [26] |

The identification of key molecular descriptors governing anticancer potency has evolved significantly with advances in computational power, machine learning algorithms, and multi-modal validation approaches. Quantum chemical descriptors consistently demonstrate superior predictive capability across diverse cancer types, while hybrid descriptor strategies that combine multiple representation methods often yield optimal performance [22] [24]. The emerging paradigm emphasizes context-specific descriptor relevance rather than universal solutions, with different descriptor combinations showing preferential performance for specific cancer types, molecular targets, and compound classes.

Future directions in descriptor research include the development of dynamic descriptors that capture conformational flexibility, integration of omics data with structural descriptors for systems pharmacology approaches, and application of explainable AI to elucidate complex descriptor-activity relationships. As QSAR modeling continues to integrate with structural biology, systems modeling, and clinical translation frameworks, refined molecular descriptor selection will remain fundamental to accelerating anticancer drug discovery and optimization. The cross-validation of descriptor significance across multiple cancer models and experimental systems represents a crucial strategy for developing robust, generalizable predictive models with genuine utility in therapeutic development.

Advanced Methodologies and Practical Applications in Anticancer QSAR

Machine Learning and Deep Learning Algorithms for Enhanced Predictions (RF, XGBoost, DNN)

The high failure rates and immense costs associated with traditional cancer drug development have necessitated more efficient and predictive approaches [29]. Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling provides a computational foundation for linking chemical structures to biological activity. The integration of modern machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) algorithms has significantly enhanced the predictive power and applicability of these models in oncology research [29] [30]. This guide objectively compares the performance of three prominent algorithms—Random Forest (RF), eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), and Deep Neural Networks (DNN)—in the context of QSAR model cross-validation for different cancer cell lines.

Performance Comparison of ML/DL Algorithms in Cancer Research

The selection of an appropriate algorithm is critical for building robust predictive models in computational oncology. The table below summarizes the documented performance of RF, XGBoost, and DNN across various cancer research tasks.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Machine Learning and Deep Learning Algorithms in Cancer Research

| Algorithm | Research Task / Target | Cancer Type | Key Performance Metrics | Reference / Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest (RF) | Tankyrase (TNKS2) inhibitor classification | Colorectal Cancer | ROC-AUC: 0.98 | [31] |

| Random Forest (RF) | KRAS inhibitor pIC50 prediction | Lung Cancer | R²: 0.796 (on test set) | [6] |

| XGBoost | KRAS inhibitor pIC50 prediction | Lung Cancer | Performance was below PLS and RF | [6] |

| LightGBM (XGBoost variant) | Anticancer ligand prediction (ACLPred) | Pan-Cancer | Accuracy: 90.33%, AUROC: 97.31% | [30] |

| Deep Neural Network (DNN) | Nanoparticle tumor delivery efficiency (DE) prediction | Pan-Cancer (Multiple) | R² (Test set): 0.41 (Tumor), 0.87 (Lung) | [32] |

| PLS Regression | KRAS inhibitor pIC50 prediction | Lung Cancer | R²: 0.851, RMSE: 0.292 (Best in study) | [6] |

Key Performance Insights

- Random Forest (RF) demonstrates exceptional performance in classification tasks, as seen in its near-perfect AUC for identifying tankyrase inhibitors [31]. It also shows robust performance in regression tasks like pIC50 prediction [6].

- XGBoost/LightGBM excels in complex classification and ranking problems. The LightGBM model in ACLPred achieved high accuracy and AUROC, indicating its strength in distinguishing active anticancer compounds from inactive ones [30].

- Deep Neural Networks (DNN) offer advantages in modeling complex, non-linear relationships, such as predicting the biodistribution of nanoparticles. Their performance can vary significantly across different tissues, highlighting the context-dependency of model efficacy [32].

- No Single Best Algorithm: The optimal algorithm is highly dependent on the specific research question, data type, and dataset size. For instance, in a direct comparison for KRAS inhibitor prediction, simpler models like PLS and RF outperformed XGBoost [6].

Experimental Protocols for Model Development and Validation

A rigorous, standardized protocol is essential for developing reliable and interpretable QSAR models. The following workflow, synthesized from multiple studies [31] [6] [30], outlines the critical steps.

Diagram 1: Workflow for Robust QSAR Model Development

Detailed Methodological Breakdown

Data Curation and Preprocessing

The foundation of a reliable model is high-quality data. Standard protocols involve:

- Database Sourcing: Publicly accessible databases like ChEMBL and PubChem BioAssay are primary sources for experimentally validated bioactive molecules and their inhibitory concentrations (e.g., IC50) [31] [6] [30].

- Data Standardization: This includes removing duplicates and standardizing molecular representations (e.g., SMILE strings).

- Activity Conversion: IC50 values (nM) are typically converted to pIC50 (-log10(IC50 × 10⁻⁹)) for regression modeling, providing a more normalized scale for analysis [6].

- Similarity Filtering: To prevent model bias, compounds with high structural similarity (e.g., Tanimoto coefficient > 0.85) are often filtered out, ensuring a diverse and non-redundant dataset [30].

Feature Calculation and Selection

Molecular structures are translated into numerical descriptors that algorithms can process.

- Descriptor Calculation: Software like PaDELPy and RDKit are used to calculate thousands of 1D, 2D, and 3D molecular descriptors and fingerprints, encompassing topological, constitutional, geometrical, and electronic features [30].

- Multistep Feature Selection: To avoid overfitting and reduce computational load, a rigorous feature selection process is employed:

- Variance Filtering: Remove descriptors with near-zero variance (e.g., variance < 0.05) [30].

- Correlation Filtering: Eliminate highly correlated descriptors (e.g., |r| > 0.95) to reduce multicollinearity [6] [30].

- Advanced Selection: Algorithms like the Boruta (a random forest-based method) or Genetic Algorithms (GA) are used to identify the most statistically significant features for prediction [6] [30].

Model Training, Optimization, and Validation

This phase involves building, tuning, and critically assessing the models.

- Data Splitting: The curated dataset is split into a training set (e.g., 70%) for model building and a hold-out test set (e.g., 30%) for final evaluation [6] [33].

- Hyperparameter Tuning: Model hyperparameters (e.g., number of trees in RF, learning rate in XGBoost, layers in DNN) are optimized via techniques like cross-validation on the training set [31] [33].

- Validation Metrics: Models are evaluated using multiple metrics:

- Applicability Domain (AD): The model's domain of applicability is assessed using methods like Mahalanobis distance to identify compounds for which predictions are reliable [6].

- Model Interpretability: Tools like SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) are increasingly used to interpret "black-box" models, quantifying the contribution of each molecular descriptor to the final prediction and providing biological insights [6] [30] [32].

Successful implementation of ML-driven QSAR projects relies on a suite of computational tools and data resources.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ML-based QSAR in Oncology

| Category | Item / Resource | Specific Examples & Functions |

|---|---|---|

| Bioactivity Databases | ChEMBL | A manually curated database of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties. Used to obtain experimentally determined IC50 values for targets like TNKS2 and KRAS [31] [6]. |

| PubChem BioAssay | A public repository containing biological activity data of small molecules. Serves as a source for active/inactive anticancer compounds for classification models [30]. | |

| Descriptor Calculation | PaDELPy | A software tool for calculating molecular descriptors and fingerprints. Used to generate 1D and 2D descriptors for ML model training [30]. |

| RDKit | An open-source cheminformatics toolkit. Used for descriptor calculation, fingerprint generation, and molecular operations [30]. | |

| Feature Selection | Boruta Algorithm | A random forest-based wrapper method for all-relevant feature selection, identifying descriptors statistically significant for prediction [30]. |

| Genetic Algorithm (GA) | An optimization technique used to select an optimal subset of molecular descriptors by mimicking natural selection [6]. | |

| Model Interpretation | SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) | A unified framework for interpreting model predictions, explaining the output of any ML model by quantifying feature importance [6] [30] [32]. |

| Specialized Models | ACLPred | An open-source, LightGBM-based prediction tool for screening potential anticancer compounds, achieving high accuracy (90.33%) [30]. |

The cross-validation of QSAR models for different cancer cell lines is powerfully enhanced by machine and deep learning algorithms. Random Forest proves to be a robust and reliable choice for both classification and regression tasks. XGBoost and its variants (like LightGBM) can achieve state-of-the-art performance in complex classification problems, such as general anticancer ligand prediction. Deep Neural Networks show great potential for modeling intricate, non-linear phenomena like nanoparticle biodistribution. There is no universally superior algorithm; the optimal choice is problem-dependent. Therefore, researchers should employ a rigorous, multi-step workflow encompassing diligent data curation, rigorous feature selection, and thorough validation, including model interpretation with tools like SHAP, to develop predictive and trustworthy models that can accelerate oncology drug discovery.

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling represents a cornerstone approach in rational drug design, enabling researchers to predict biological activity based on a compound's molecular structure. Over forty years have elapsed since Hansch and Fujita published their pioneering QSAR work, establishing a foundation that has evolved significantly with computational advances [34]. The fundamental premise of QSAR involves constructing mathematical models that correlate molecular descriptors (quantitative representations of structural features) with biological activity, creating predictive tools that guide structural optimization before resource-intensive chemical synthesis and biological testing.

Following the introduction of Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) by Cramer in 1998, numerous three-dimensional QSAR methodologies have emerged, greatly enhancing the field's predictive capabilities [34]. Currently, the integration of classical QSAR with advanced computational techniques represents the state-of-the-art in modern drug discovery. These models have proven indispensable not only for reliably predicting specific properties of new compounds but also for elucidating potential molecular mechanisms of receptor-ligand interactions [34]. Within oncology drug discovery, QSAR approaches provide a systematic framework for optimizing chemotherapeutic agents, particularly through cross-validation across different cancer cell lines to assess compound specificity and potential therapeutic windows.

QSAR Fundamentals and Molecular Descriptors

Core Principles and Workflow

QSAR modeling transforms chemical structural information into quantifiable parameters that can be statistically correlated with biological responses. The standard QSAR development workflow involves: (1) compound selection and dataset curation, (2) molecular structure representation and optimization, (3) molecular descriptor calculation, (4) statistical model development correlating descriptors with biological activity, (5) model validation, and (6) model application for predicting new compounds. The predictive performance of QSAR models relies heavily on appropriate descriptor selection and robust statistical methodologies.

Essential Molecular Descriptor Classes

Molecular descriptors quantitatively characterize aspects of molecular structure that influence biological activity and physicochemical properties. Key descriptor categories include:

- Electronic descriptors: Quantify electron distribution characteristics affecting molecular interactions (e.g., electronegativity, dipole moment) [13]

- Steric descriptors: Characterize molecular size, shape, and volume (e.g., van der Waals volume, molar refractivity) [13]

- Geometric descriptors: Describe three-dimensional molecular dimensions and arrangements

- Topological descriptors: Encode molecular connectivity patterns and branching characteristics

- Polarizability parameters: Measure how easily electron clouds distort under external fields (e.g., MATS3p) [13]

Table 1: Key Molecular Descriptor Categories in QSAR Modeling

| Descriptor Category | Representative Descriptors | Structural Properties Characterized |

|---|---|---|

| Electronic | Dipole moment, E1e, EEig15d | Charge distribution, electronegativity, molecular polarity |

| Steric | GATS5v, GATS6v, Mor16v | van der Waals volume, molecular size and bulk |

| Topological | RCI, SHP2 | Ring complexity, molecular shape, branching patterns |

| Polarizability | MATS3p, BELp8 | Electron cloud distortion potential |

Case Study: QSAR-Guided Optimization of Anticancer Flavones

Experimental Protocol and Compound Design

A recent investigation applied machine learning-driven QSAR modeling to optimize flavones, recognized as "privileged scaffolds" in drug discovery [23]. Researchers initially employed pharmacophore modeling against diverse cancer targets to design 89 flavone analogs featuring varied substitution patterns. These compounds were subsequently synthesized and evaluated biologically to identify promising candidates with enhanced cytotoxicity against breast cancer (MCF-7) and liver cancer (HepG2) cell lines, alongside low toxicity toward normal Vero cells [23].

The experimental protocol followed this standardized approach:

- Rational Design: Computational pharmacophore modeling identified key structural motifs for target interaction

- Chemical Synthesis: Preparation of 89 flavone analogs with systematic substitution variations

- Biological Evaluation:

- Cytotoxicity assessment against MCF-7 and HepG2 cancer cell lines

- Selectivity profiling using normal Vero cells

- Dose-response measurements for IC50 determination

- QSAR Model Development:

- Molecular descriptor calculation for all synthesized compounds

- Machine learning algorithm implementation (RF, XGBoost, ANN)

- Model training and validation using cross-validation techniques

- Model Interpretation: SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) analysis to identify critical structural features

Machine Learning Model Performance

The research team compared multiple machine learning algorithms for QSAR model development, with the Random Forest (RF) model demonstrating superior performance [23]. The RF model achieved R² values of 0.820 for MCF-7 and 0.835 for HepG2, with cross-validation R² (R²cv) of 0.744 and 0.770, respectively. External validation using 27 test compounds yielded root mean square error test values of 0.573 (MCF-7) and 0.563 (HepG2), confirming model robustness and predictive capability [23].

Table 2: Machine Learning QSAR Model Performance for Anticancer Flavones

| Machine Learning Algorithm | R² (MCF-7) | R² (HepG2) | R²cv (MCF-7) | R²cv (HepG2) | RMSE Test (MCF-7) | RMSE Test (HepG2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest | 0.820 | 0.835 | 0.744 | 0.770 | 0.573 | 0.563 |

| Extreme Gradient Boosting | Performance data not specified in source | |||||

| Artificial Neural Network | Performance data not specified in source |

Key Structural Features Influencing Anticancer Activity

SHAP analysis identified critical molecular descriptors significantly influencing flavone anticancer activity [23]. These descriptors provide concrete guidance for structural modifications:

- Electron density distribution at specific molecular positions

- Steric bulk and substitution patterns affecting target binding

- Hydrophobic character optimizing membrane permeability

- Hydrogen bonding capacity facilitating specific molecular interactions

- Molecular polarizability influencing binding affinity

Case Study: QSAR Modeling of 1,4-Naphthoquinone Anticancer Agents

Experimental Methodology

Another research effort explored substituted 1,4-naphthoquinones for potential anticancer therapeutics, investigating a series of 14 compounds (1-14) against four cancer cell lines: HepG2 (liver), HuCCA-1 (bile duct), A549 (lung), and MOLT-3 (leukemia) [13]. Compound 11 emerged as the most potent and selective anticancer agent across all tested cell lines (IC₅₀ = 0.15 – 1.55 μM, selectivity index = 4.14 – 43.57) [13].

The research methodology encompassed:

- Compound Screening: Cytotoxicity evaluation against four cancer cell lines

- Selectivity Assessment: Comparison with normal cell toxicity

- QSAR Model Construction: Four models developed using multiple linear regression (MLR) algorithm

- Model Validation: Rigorous training and testing set validation

- Virtual Expansion: QSAR model application to 248 structurally modified compounds

- ADMET Profiling: Prediction of pharmacokinetic properties and potential biological targets

QSAR Model Performance and Structural Insights

The four QSAR models demonstrated excellent predictive performance with correlation coefficients (R) for the training set ranging from 0.8928 to 0.9664 and testing set values between 0.7824 and 0.9157 [13]. RMSE values were 0.1755–0.2600 for training sets and 0.2726–0.3748 for testing sets, confirming model reliability [13].

The QSAR analysis revealed that potent anticancer activities of naphthoquinones were primarily influenced by:

- Polarizability (MATS3p and BELp8 descriptors)

- van der Waals volume (GATS5v, GATS6v, and Mor16v)

- Atomic mass (G1m)

- Electronegativity (E1e)

- Dipole moment (Dipole and EEig15d)

- Ring complexity (RCI)

- Molecular shape (SHP2) [13]

Table 3: Key Molecular Descriptors for Naphthoquinone Anticancer Activity

| Molecular Descriptor | Descriptor Category | Structural Interpretation | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| MATS3p | Polarizability | Electron cloud distortion potential | Influences binding affinity |

| GATS5v, GATS6v | Steric | van der Waals volume | Affects target binding pocket fit |

| G1m | Mass | Atomic mass distribution | Impacts pharmacokinetics |

| E1e | Electronic | Electronegativity | Affects hydrogen bonding capacity |

| Dipole | Electronic | Molecular dipole moment | Influences interaction orientation |

| RCI | Topological | Ring complexity | Affects molecular rigidity |

| SHP2 | Topological | Molecular shape | Determines target complementarity |

Advanced QSAR Methodologies and Machine Learning Approaches

Predictive Distributions and Model Validation

Modern QSAR implementation emphasizes comprehensive validation approaches, including predictive distributions that represent QSAR predictions as probability distributions across possible property values [11]. This advanced framework acknowledges that both experimental measurements and QSAR predictions contain inherent uncertainties that should be quantitatively assessed.

The Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence framework provides an information-theoretic approach for evaluating predictive distributions, measuring the distance between experimental measurement distributions and model predictive distributions [11]. This method enables more nuanced model assessment by simultaneously evaluating prediction accuracy and uncertainty estimation, addressing a critical need in pharmaceutical applications where understanding prediction reliability directly impacts decision-making in compound selection and prioritization.

Cross-Validation Across Cancer Cell Lines

Cross-validation represents an essential component of robust QSAR model development, particularly in anticancer drug discovery where compound specificity across different cancer types is both a practical concern and an opportunity for therapeutic optimization. The case studies demonstrate this approach through:

- Multiple cell line screening: Both flavones and naphthoquinones were evaluated across distinct cancer cell types

- Model transferability assessment: Determining whether structural features important for activity against one cancer type generalize to others

- Selectivity profiling: Identifying structural modifications that enhance cancer cell specificity while reducing normal cell toxicity

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for QSAR-Guided Anticancer Drug Discovery

| Reagent/Material | Specification | Research Function |

|---|---|---|

| Cancer Cell Lines | MCF-7, HepG2, A549, HuCCA-1, MOLT-3 | In vitro models for cytotoxicity assessment and selectivity profiling |

| Normal Cell Lines | Vero cells | Control for determining selective toxicity and therapeutic index |

| Chemical Scaffolds | Flavone, 1,4-naphthoquinone core structures | Privileged structures for structural modification and optimization |

| Molecular Descriptor Software | Various computational packages | Calculation of electronic, steric, and topological descriptors |

| Machine Learning Platforms | Random Forest, XGBoost, ANN algorithms | QSAR model development and validation |

| ADMET Prediction Tools | In silico platforms | Virtual assessment of pharmacokinetics and toxicity profiles |

Visualizing QSAR-Guided Drug Design Workflows

QSAR-Guided Drug Design Workflow: This diagram illustrates the iterative process of rational drug design using QSAR modeling, highlighting the continuous cycle of synthesis, testing, modeling, and structural refinement that leads to optimized lead compounds.

Machine Learning Approaches in QSAR: This diagram compares machine learning methodologies used in modern QSAR modeling, demonstrating how different algorithms contribute to compound activity prediction and optimization prioritization.

QSAR modeling continues to evolve as an indispensable tool in rational anticancer drug design, successfully bridging computational predictions and experimental validation. The integration of machine learning algorithms has significantly enhanced predictive accuracy, enabling more reliable compound prioritization before synthesis. The cross-validation of QSAR models across multiple cancer cell lines provides critical insights into structural features governing both potency and selectivity, ultimately contributing to improved therapeutic indices. As demonstrated in the flavone and naphthoquinone case studies, QSAR-guided structural modifications systematically optimize critical molecular descriptors including polarizability, steric volume, electronic properties, and molecular shape. These approaches collectively advance the development of targeted anticancer therapeutics with enhanced efficacy and reduced toxicity profiles.

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling represents a fundamental computational approach in ligand-based drug discovery that mathematically correlates a chemical compound's molecular structure with its biological activity [35] [36]. In breast cancer research, QSAR models have evolved from predicting activity of single drugs to complex combinational therapies, addressing the heterogeneous nature of this prevalent malignancy [5] [1]. Breast cancer remains the most common and heterogeneous form of cancer affecting women worldwide, with an estimated 300,590 new cases and 43,700 deaths annually in the United States alone [5]. The limitations of monotherapies and the emergence of drug resistance have accelerated research into combinational approaches, creating an urgent need for predictive computational models that can efficiently screen drug pairs for synergistic effects [5] [37].

This guide objectively compares the performance of various machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) algorithms in developing combinational QSAR models for breast cancer therapy, with particular emphasis on cross-validation methodologies essential for ensuring model reliability across different cancer cell lines. By examining experimental protocols, performance metrics, and implementation requirements, we provide researchers with a comprehensive framework for selecting appropriate modeling strategies in anti-cancer drug discovery.

Theoretical Foundation: Combinational QSAR Principles

Core Concepts in Combinational QSAR

Traditional QSAR modeling establishes relationships between molecular descriptors of single compounds and their biological activity, typically expressed as IC50 values (the concentration required for 50% inhibition) [35]. Combinational QSAR extends this principle to drug pairs, incorporating the concept of anchor drugs—well-established primary therapeutic agents with known efficacy for specific targets—and library drugs—supplementary compounds that enhance anchor drug efficacy and broaden the therapeutic approach [5] [1].

The fundamental equation for QSAR modeling can be represented as:

Biological Activity = f(Molecular Descriptors) + ε

Where molecular descriptors quantitatively represent structural, topological, geometric, electronic, and physicochemical characteristics of the compounds, and ε represents the error term not explained by the model [36]. In combinational QSAR, this relationship expands to incorporate descriptors from both anchor and library drugs, plus interaction terms that capture synergistic effects [5].

Molecular Descriptors and Feature Representation

Molecular descriptors serve as the predictive variables in QSAR models and can be categorized into several classes: