Computer-Aided Drug Design in Oncology: Principles, AI Integration, and Clinical Translation

This article provides a comprehensive overview of computer-aided drug design (CADD) principles and their transformative application in oncology drug development.

Computer-Aided Drug Design in Oncology: Principles, AI Integration, and Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of computer-aided drug design (CADD) principles and their transformative application in oncology drug development. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores foundational computational methods, examines cutting-edge methodologies including AI and machine learning integration, addresses optimization challenges in clinical translation, and analyzes validation frameworks and comparative effectiveness of CADD approaches. By synthesizing current trends and technologies, this review serves as both an educational resource and strategic guide for leveraging computational approaches to accelerate cancer drug discovery, from target identification to clinical implementation.

The Computational Foundation: Core Principles of CADD in Cancer Therapeutics

The field of drug discovery has undergone a transformative shift, moving away from reliance on traditional, high-cost screening methods toward computational precision. Computer-Aided Drug Design (CADD) represents the use of computational techniques and software tools to discover, design, and optimize new drug candidates, thereby accelerating the drug discovery process, reducing costs, and improving success rates [1]. In the context of oncology research, where the complexity of cancer biology and the urgent need for targeted therapies are paramount, CADD provides a powerful framework for understanding disease mechanisms at a molecular level and designing precise interventions [2] [3]. This guide details the core principles of CADD, framing them within the critical pursuit of novel oncology therapeutics, and provides a practical toolkit for their application.

Core Methodologies in CADD

CADD methodologies are broadly classified into two complementary categories: structure-based and ligand-based approaches. The selection between them is primarily determined by the availability of structural information for the biological target.

Structure-Based Drug Design (SBDD)

Structure-Based Drug Design (SBDD) leverages the three-dimensional structural information of biological targets, typically proteins, to identify and optimize potential drug molecules [1] [3]. This approach dominated the CADD market with a share of approximately 55% in 2024 [1] [3]. It is indispensable when high-resolution structures of the target, often obtained through X-ray crystallography or Cryo-EM, are available.

The foundational technologies of SBDD include:

- Molecular Docking: This computational technique predicts the preferred orientation (posing) and binding affinity (scoring) of a small molecule (ligand) when bound to a target protein [1]. It is a primary step in virtual screening and was the dominant technology in the CADD market in 2024, holding a ~40% share [1]. Tools like AutoDock Vina are frequently used for this purpose, for instance, in targeting the RdRp enzyme for antiviral development or in oncology [3].

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations: MD simulations model the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time, providing a dynamic view of protein-ligand interactions, protein folding, and conformational changes that are missed in static structures [2]. This method is crucial for refining docking results and assessing the stability of a predicted complex under near-physiological conditions [2]. Its application was key in the design of drugs like imatinib for cancer [3].

Ligand-Based Drug Design (LBDD)

When the three-dimensional structure of the target is unknown, Ligand-Based Drug Design (LBDD) offers a powerful alternative. This approach designs novel drugs based on the known chemical properties and biological activities of existing active ligands [2] [1]. The LBDD segment is expected to grow at the fastest compound annual growth rate (CAGR) in the coming years [1] [3].

Key LBDD techniques include:

- Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR): This method builds mathematical models that correlate the chemical structure of compounds (described by molecular descriptors) with their biological activity [2]. These models can then predict the activity of new, unsynthesized compounds.

- Pharmacophore Modeling: A pharmacophore is an abstract definition of the essential steric and electronic functional groups necessary for a molecule to interact with a target and trigger its biological response [2]. Pharmacophore models are used for virtual screening to identify new chemical scaffolds that fulfill these spatial constraints.

The Role of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning

Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) have become deeply integrated throughout the CADD workflow, creating a subfield often termed AI-driven drug design (AIDD) [4]. AI/ML-based drug design is the fastest-growing technology segment in CADD [1] [3]. These technologies enhance traditional CADD by analyzing vast, complex datasets to identify patterns beyond human capability.

Specific applications include:

- Generative Models: Using variational autoencoders (VAEs) and generative adversarial networks (GANs) to design completely novel molecular structures with desired properties [2].

- Enhanced Virtual Screening: AI algorithms can pre-filter massive compound libraries or re-rank docking results to significantly improve hit rates and scaffold diversity [4].

- Predictive Modeling: ML models are used to predict key pharmacokinetic and toxicity profiles (ADMET - Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) of compounds early in the discovery process [4].

Table 1: Quantitative Overview of the CADD Market (2024 Baseline)

| Category | Dominant Segment | Market Share (2024) | Fastest-Growing Segment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Structure-Based Drug Design (SBDD) | ~55% [1] [3] | Ligand-Based Drug Design (LBDD) [1] [3] |

| Technology | Molecular Docking | ~40% [1] | AI/ML-Based Drug Design [1] [3] |

| Application | Cancer Research | ~35% [1] [3] | Infectious Diseases [1] [3] |

| End-User | Pharmaceutical & Biotech Companies | ~60% [1] | Academic & Research Institutes [1] [3] |

| Deployment | On-Premise | ~65% [1] | Cloud-Based [1] [3] |

CADD Workflows and Experimental Protocols

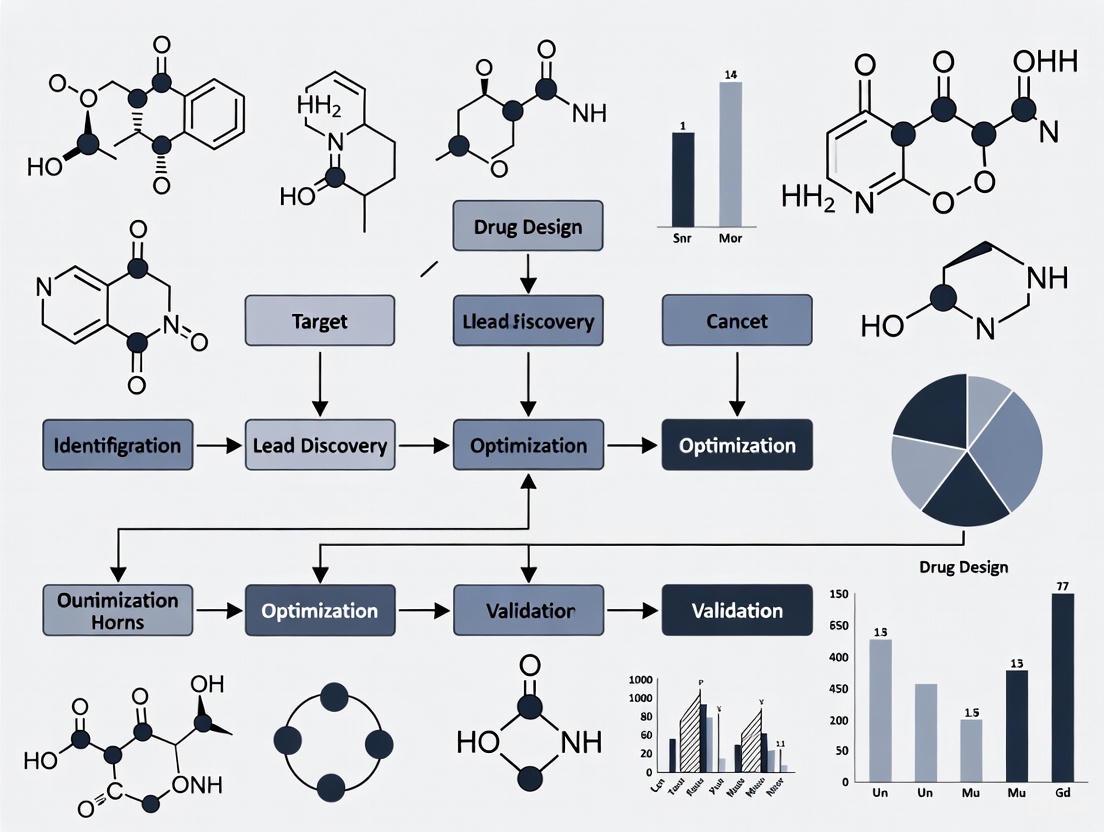

A typical CADD-driven project in oncology follows an iterative workflow that integrates computational predictions with experimental validation. The following diagram and protocol outline a standard structure-based approach for identifying a novel inhibitor for an oncology target.

Diagram Title: CADD Workflow for Oncology Drug Discovery.

Protocol: Structure-Based Virtual Screening for an Oncology Target

This protocol details the key computational and experimental steps for identifying a novel small-molecule inhibitor.

A. Computational Phase

Target Identification and Preparation:

- Objective: Select a validated oncology target (e.g., a mutant kinase like KRAS G12C) and obtain a high-quality 3D structure.

- Methodology:

- Retrieve a crystal structure from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) or generate a predicted structure using AlphaFold [2].

- Prepare the protein structure using molecular modeling software: remove water molecules, add hydrogen atoms, assign partial charges, and correct protonation states of key residues (e.g., Asp, Glu, His).

- Define the binding site, often based on the known location of a co-crystallized native ligand.

Library Preparation:

- Objective: Assay a large and diverse chemical space in silico.

- Methodology:

- Obtain compound libraries (e.g., ZINC, Enamine) containing millions of commercially available molecules.

- Prepare all ligands: generate plausible 3D conformations, minimize their energy, and assign correct charges.

- Filter the library based on drug-likeness rules (e.g., Lipinski's Rule of Five) and other desirable properties to create a focused screening library.

Virtual Screening and Hit Selection:

- Objective: Identify a manageable number of high-probability hits for experimental testing.

- Methodology:

- Perform High-Throughput Virtual Screening (HTVS) using molecular docking software (e.g., AutoDock Vina, Glide) to score and rank all compounds in the library by their predicted binding affinity [2] [3].

- Visually inspect the top-ranking compounds (e.g., top 1000) for sensible binding modes and key molecular interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts).

- Apply more computationally intensive methods like Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations or free-energy perturbation (FEP) calculations to a shortlist (e.g., 100-200 compounds) to refine affinity predictions and assess binding stability [2].

- Select a final, diverse set of 20-50 top-predicted compounds for purchase and experimental validation.

B. Experimental Validation Phase

In Vitro Biochemical Assay:

- Objective: Confirm the biological activity of the computational hits.

- Methodology:

- Procure the selected compounds from commercial suppliers.

- Perform a dose-response biochemical assay to measure the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of each compound against the purified target protein (e.g., the kinase). A typical assay measures the decrease in enzyme activity in the presence of the inhibitor.

- Compounds showing significant activity (e.g., IC50 < 10 µM) are considered "confirmed hits" and progress to the next stage.

Lead Optimization:

- Objective: Improve the potency and drug-like properties of the confirmed hits.

- Methodology:

- Use medicinal chemistry to synthesize analogs of the hit compound.

- Employ iterative cycles of CADD (e.g., analog docking, QSAR, FEP) to guide the design of new analogs, predicting which structural changes will improve affinity and reduce off-target effects.

- Experimentally test the new analogs, feeding the data back into the computational models to refine predictions. This loop continues until a pre-clinical candidate drug with nanomolar potency and acceptable ADMET properties is identified.

Successful application of CADD in an oncology research setting relies on a suite of computational tools, databases, and experimental reagents.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for CADD in Oncology

| Item / Resource | Type | Function in CADD |

|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold [2] | Software/Model | Accurately predicts 3D protein structures when experimental structures are unavailable, crucial for working with novel oncology targets. |

| AutoDock Vina [3] | Software | An open-source tool for molecular docking, used for virtual screening and binding pose prediction. |

| RaptorX [2] | Software/Model | Predicts protein structures and residue-residue contacts, useful for modeling mutations common in cancer. |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Database | A repository of experimentally determined 3D structures of proteins and nucleic acids, providing starting points for SBDD. |

| ZINC/Enamine Libraries | Database | Commercial and public databases of purchasable compounds used for virtual screening. |

| Purified Target Protein | Wet-lab Reagent | Essential for in vitro biochemical assays to validate computational hits (e.g., measure IC50 values). |

| Cell Lines (Cancer) | Wet-lab Reagent | Used for cellular assays to confirm compound activity and selectivity in a more physiologically relevant model. |

CADD has fundamentally reshaped the landscape of oncology drug discovery, providing a systematic and rational path from gene to candidate drug. The convergence of traditional physics-based computational methods with modern artificial intelligence is pushing the boundaries of what is possible, opening up previously "undruggable" targets and compressing development timelines [5] [4]. While challenges remain—such as the occasional gap between computational prediction and experimental result—the iterative cycle of in silico design, experimental validation, and model refinement creates a powerful engine for innovation [2]. For the modern oncology researcher, a firm grasp of CADD principles is no longer a specialty but a core component of the toolkit, essential for delivering the next generation of precise and life-saving cancer therapeutics.

Within the realm of computer-aided drug design (CADD) for oncology research, two methodological pillars have emerged as fundamental to modern discovery efforts: structure-based drug design (SBDD) and ligand-based drug design (LBDD). These computational approaches have revolutionized the identification and optimization of anticancer agents, enabling researchers to navigate complex biological systems with increasing precision [6]. The integration of these frameworks has become particularly valuable in addressing the challenges posed by cancer heterogeneity and drug resistance, ultimately accelerating the development of targeted therapies and personalized treatment strategies [7].

This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of both methodological frameworks, detailing their underlying principles, key techniques, and practical applications in oncology drug discovery. By presenting structured comparisons, experimental protocols, and visualization of workflows, we aim to equip researchers with a comprehensive understanding of how these approaches can be deployed individually and in concert to advance anticancer drug development.

Core Principles and Definitions

Structure-Based Drug Design (SBDD)

SBDD relies on the three-dimensional structural information of the target protein to design or optimize small molecule compounds that can bind to it [8]. This method is fundamentally centered on the molecular recognition principle, where drug candidates are designed to complement the physicochemical properties and spatial configuration of a target's binding site [8]. The approach requires high-resolution protein structures, typically obtained through experimental methods such as X-ray crystallography, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), or cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM), or through computationally predicted models [8] [6].

Ligand-Based Drug Design (LBDD)

LBDD utilizes information from known active small molecules (ligands) that bind to the target of interest [8]. When the three-dimensional structure of the target protein is unknown or difficult to obtain, this method predicts and designs compounds with similar activity by analyzing the chemical properties, structural features, and mechanism of action of existing ligands [8] [9]. The core assumption underpinning LBDD is that structurally similar molecules tend to exhibit similar biological activities [9].

Key Techniques and Methodologies

Structure-Based Techniques

Molecular Docking: This core SBDD technique predicts the preferred orientation and conformation of a small molecule ligand when bound to its target protein [9]. Docking algorithms perform flexible ligand docking while often treating proteins as rigid, a simplification that allows for high-throughput screening but may not fully capture binding site flexibility [9]. The resulting poses are scored and ranked based on interaction energies including hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonds, and Coulombic interactions [9].

Free Energy Perturbation (FEP): A highly accurate but computationally demanding method, FEP estimates binding free energies using thermodynamic cycles [10] [9]. It is primarily used during lead optimization to quantitatively evaluate the impact of small structural modifications on binding affinity, though it remains challenging to apply to structurally diverse compounds [10].

Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations: MD simulations model conformational changes within a ligand-target complex by tracking atomic movements over time [6]. This approach helps address target flexibility and can reveal cryptic binding pockets not evident in static structures [6]. Advanced methods like accelerated MD (aMD) smooth energy barriers to enhance conformational sampling [6].

Ligand-Based Techniques

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR): QSAR models employ mathematical relationships between chemical structures and biological activity [8]. By extracting molecular descriptors of compounds—including electronic properties, hydrophobicity, and structural parameters—QSAR can predict the biological activity of new compounds and facilitate candidate screening [8]. Modern implementations often use machine learning to improve predictive accuracy [11].

Pharmacophore Modeling: This technique identifies and models the essential structural features necessary for a molecule to interact with its target [8]. A pharmacophore model abstracts common characteristics from known active compounds, such as hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions, and charged groups, providing a template for screening new compounds [8].

Similarity-Based Virtual Screening: This approach identifies potential hits from large compound libraries by comparing candidate molecules against known actives using molecular fingerprints or 3D descriptors like shape and electrostatic properties [9] [12]. It excels at pattern recognition and can efficiently prioritize compounds with shared characteristics [12].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Key Techniques in SBDD and LBDD

| Technique | Methodological Basis | Primary Applications | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Docking [9] | Protein-ligand complementarity | Virtual screening, binding pose prediction | Direct visualization of interactions, rational design guidance | Protein flexibility often limited, scoring function inaccuracies |

| Free Energy Perturbation [10] | Thermodynamic cycles | Lead optimization, affinity prediction | High accuracy for small modifications | Extremely computationally intensive, limited to close analogs |

| Molecular Dynamics [6] | Atomic trajectory simulation | Binding stability, conformational sampling, cryptic pocket discovery | Accounts for full system flexibility, physiological conditions | Computationally expensive, limited timescales |

| QSAR [8] [11] | Statistical/machine learning models | Activity prediction, compound prioritization | Fast screening of large libraries, can extrapolate to novel chemotypes | Dependent on quality/quantity of training data, limited interpretability |

| Pharmacophore Modeling [8] | Essential feature abstraction | Virtual screening, scaffold hopping | Intuitive representation, target structure not required | Limited to known chemotypes, conformation-dependent |

| Similarity Screening [9] [12] | Molecular similarity metrics | Library enrichment, hit identification | Fast, scalable, identifies diverse actives | Bias toward known chemical space, may miss novel scaffolds |

Experimental Protocols in Oncology Research

Protocol 1: Structure-Based Virtual Screening for Anticancer Targets

This protocol outlines a structure-based approach for identifying potential inhibitors, exemplified by a study targeting the human αβIII tubulin isotype for cancer therapy [11].

Step 1: Target Preparation

- Obtain the three-dimensional structure of the target protein from experimental sources (PDB database) or through homology modeling if experimental structures are unavailable [11].

- For homology modeling, use tools like Modeller with a template structure of high sequence identity. Select the final model based on validation scores (e.g., DOPE score) and stereo-chemical quality (e.g., Ramachandran plot via PROCHECK) [11].

- Prepare the protein structure by adding hydrogen atoms, assigning partial charges, and defining the binding site coordinates based on known ligand binding locations.

Step 2: Compound Library Preparation

- Retrieve natural compounds or synthetic libraries from databases such as ZINC in SDF format [11].

- Convert compounds to appropriate formats (e.g., PDBQT) using tools like Open-Babel [11].

- Generate 3D conformations and optimize geometries using molecular mechanics force fields.

Step 3: High-Throughput Virtual Screening

- Perform molecular docking against the defined binding site using software such as AutoDock Vina or InstaDock [11].

- Filter compounds based on binding energy thresholds, typically selecting the top 1,000-10,000 hits for further analysis [11].

- Visually inspect top-ranking complexes to confirm sensible binding modes and interactions.

Step 4: Machine Learning Classification

- Generate molecular descriptors for both active and inactive reference compounds using tools like PaDEL-Descriptor [11].

- Train supervised machine learning classifiers (e.g., random forest, SVM) to distinguish between active and inactive molecules [11].

- Apply the trained model to the screened hits to identify compounds with the highest probability of biological activity.

Step 5: ADME-T and Toxicity Prediction

- Evaluate drug-likeness properties of selected hits using ADME-T (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) prediction tools [11].

- Filter compounds based on acceptable pharmacokinetic profiles and low predicted toxicity.

Step 6: Validation through MD Simulations

- Subject top candidates to molecular dynamics simulations (e.g., using GROMACS or AMBER) to assess complex stability [11].

- Analyze trajectories using RMSD, RMSF, Rg, and SASA to evaluate structural stability and interaction persistence [11].

- Calculate binding free energies using methods such as MM/PBSA to confirm affinity [11].

Protocol 2: Ligand-Based Design for Kinase Inhibitors in Oncology

This protocol demonstrates a ligand-based approach for designing targeted kinase inhibitors, relevant to numerous cancer pathways.

Step 1: Compound Curation and Data Preparation

- Collect a diverse set of known active compounds against the target of interest, along with their experimental activity data (e.g., IC50, Ki) [9].

- Include structurally similar but inactive compounds to define the activity landscape and avoid potential biases [9].

- Curate the dataset to ensure chemical structure standardization and consistent biological activity measurements.

Step 2: Molecular Descriptor Calculation and Feature Selection

- Compute comprehensive molecular descriptors (e.g., topological, geometrical, electronic) and fingerprints using tools like PaDEL-Descriptor [11].

- Apply feature selection techniques to identify the most relevant descriptors contributing to biological activity, reducing dimensionality and minimizing noise.

Step 3: QSAR Model Development

- Split the dataset into training and test sets using appropriate methods (e.g., random sampling, k-means clustering based on chemical space) [11].

- Develop QSAR models using machine learning algorithms such as random forest, support vector machines, or neural networks [9].

- Optimize model hyperparameters through cross-validation to prevent overfitting.

Step 4: Model Validation and Applicability Domain

- Evaluate model performance using test set predictions and statistical metrics (e.g., R², RMSE, AUC) [11].

- Define the model's applicability domain to identify compounds for which predictions are reliable, based on chemical space coverage of the training set.

Step 5: Virtual Screening and Compound Prioritization

- Apply the validated QSAR model to screen large virtual compound libraries [9].

- Rank compounds based on predicted activity and cluster structurally similar hits to ensure chemical diversity.

- Apply additional filters based on drug-likeness rules (e.g., Lipinski's Rule of Five) and synthetic accessibility.

Step 6: Pharmacophore Modeling and Scaffold Hopping

- Develop a pharmacophore model based on the alignment of known active compounds, identifying essential features for target binding [8].

- Use the pharmacophore model to screen compound libraries and identify novel scaffolds (scaffold hopping) that maintain critical interactions but offer improved properties [9].

Integrated Workflows and Synergistic Applications

The integration of SBDD and LBDD approaches creates a powerful synergistic workflow that leverages the complementary strengths of both methodologies [10] [9] [12]. Two primary integration strategies have emerged as particularly effective in oncology drug discovery.

Sequential Integration: This practical approach uses ligand-based methods as an initial filtering step before applying more computationally intensive structure-based analyses [9] [12]. Large compound libraries are first screened using fast 2D/3D similarity searches against known actives or QSAR predictions. The most promising subset then undergoes molecular docking and binding affinity predictions [12]. This sequential approach improves efficiency by applying resource-intensive methods only to pre-filtered, high-potential compounds [9].

Parallel/Hybrid Screening: Advanced pipelines employ parallel screening, running both structure-based and ligand-based methods independently but simultaneously on the same compound library [9] [12]. Each method generates its own ranking of compounds, and results are compared or combined using consensus scoring frameworks [9]. Parallel scoring selects the top n% of compounds from both similarity rankings and docking scores, increasing the likelihood of recovering potential actives [9]. Hybrid scoring multiplies scores from each method to create a unified ranking, favoring compounds ranked highly by both approaches and increasing confidence in true positives [9] [12].

Diagram 1: Method Selection Workflow in CADD - This diagram illustrates the decision process for selecting appropriate computational approaches based on available data, highlighting pathways for structure-based, ligand-based, and integrated methods.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for SBDD and LBDD

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Relevance to Oncology |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Structure Databases | PDB, AlphaFold Database | Source of experimental and predicted protein structures | Enables targeting of cancer-related proteins with unknown structures |

| Compound Libraries | ZINC, ChEMBL, REAL Database | Collections of screening compounds with chemical diversity | Provides starting points for targeting various oncology targets |

| Molecular Docking Software | AutoDock Vina, InstaDock, Glide | Predicts ligand binding modes and affinity | Critical for virtual screening against cancer drug targets |

| MD Simulation Packages | GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD | Models dynamic behavior of protein-ligand complexes | Studies drug resistance mechanisms in cancer targets |

| QSAR/Modeling Tools | PaDEL-Descriptor, QuanSA, ROCS | Generates molecular descriptors and predictive models | Enables activity prediction for compound optimization |

| Pharmacophore Modeling | Phase, MOE, Catalyst | Identifies essential structural features for activity | Supports scaffold hopping for novel cancer therapeutics |

| Cheminformatics Platforms | OpenBabel, RDKit | Handles chemical data conversion and manipulation | Preprocessing and analysis of chemical libraries |

| AI/ML Frameworks | TensorFlow, Scikit-learn, GENTRL | Builds predictive models for compound activity | Accelerates de novo design of oncology drugs |

Structure-based and ligand-based drug design represent complementary pillars of modern computational drug discovery in oncology. SBDD offers atomic-level insights into drug-target interactions when structural information is available, while LBDD provides powerful pattern recognition capabilities that can guide discovery even in the absence of structural data [8] [9]. The integration of these approaches through sequential or parallel strategies creates a synergistic workflow that enhances hit identification, improves prediction accuracy, and ultimately accelerates the discovery of novel anticancer agents [10] [9] [12].

As oncology research continues to confront challenges of tumor heterogeneity, drug resistance, and personalized treatment needs, these computational frameworks will play an increasingly vital role. Future advances in artificial intelligence, structural biology, and multi-omics integration will further enhance the precision and efficiency of both SBDD and LBDD, solidifying their position as indispensable methodologies in the development of next-generation cancer therapeutics.

The development of new therapeutics, particularly in oncology, has been transformed by computer-aided drug design (CADD) approaches. These methodologies address the fundamental challenges of traditional drug discovery—lengthy timelines, high costs, and significant attrition rates—by providing powerful computational frameworks for identifying and optimizing candidate molecules [13] [14]. Within CADD, three core techniques have emerged as essential: molecular docking, which predicts how small molecules interact with protein targets at the atomic level; Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling, which correlates chemical structures with biological activity using mathematical models; and pharmacophore modeling, which identifies the essential structural features responsible for molecular recognition [15] [16] [17]. In the complex landscape of cancer research, where disease mechanisms involve diverse phenotypes and multiple etiologies, these computational tools enable researchers to efficiently identify novel therapeutic candidates, optimize lead compounds, and elucidate mechanisms of drug action [18] [14]. The integration of these methods into drug discovery pipelines has become indispensable for advancing targeted cancer therapies, with applications spanning from initial hit identification to lead optimization stages.

Molecular Docking: Predicting Molecular Interactions

Fundamental Principles and Methodologies

Molecular docking is a computational technique that predicts the preferred orientation and binding affinity of a small molecule (ligand) when bound to a target macromolecule (receptor), typically a protein [15]. The primary goals of docking are twofold: first, to predict the ligand's binding pose (position and orientation) within the receptor's binding site, and second, to estimate the binding affinity through scoring functions [15]. This approach is grounded in molecular recognition theories, primarily the "lock-and-key" model, where complementary surfaces pre-exist, and the more sophisticated "induced fit" theory, which accounts for conformational adjustments in both ligand and receptor upon binding [15]. The docking process comprises two fundamental components: sampling algorithms that explore possible ligand conformations and orientations, and scoring functions that rank these poses based on estimated binding energy [15].

When structural information about the binding site is unavailable, blind docking approaches can be employed, which search the entire protein surface for potential binding pockets, aided by cavity detection programs such as GRID, POCKET, SurfNet, PASS, and MMC [15]. The treatment of molecular flexibility varies across docking methods, ranging from rigid-body docking (treating both ligand and receptor as rigid) to flexible ligand docking (accounting for ligand conformational flexibility while keeping the receptor rigid) and fully flexible docking (modeling flexibility in both ligand and receptor) [15].

Key Sampling Algorithms and Scoring Approaches

Various sampling algorithms have been developed to efficiently explore the vast conformational space of ligand-receptor interactions, each with distinct advantages and implementation considerations:

Table 1: Key Sampling Algorithms in Molecular Docking

| Algorithm | Characteristics | Representative Software |

|---|---|---|

| Matching Algorithms | Geometry-based, map ligands to active sites using pharmacophores; high speed suitable for virtual screening | DOCK, FLOG, LibDock, SANDOCK [15] |

| Incremental Construction | Divides ligand into fragments, docks anchor fragment first, then builds incrementally | FlexX, DOCK 4.0, Hammerhead, eHiTS [15] |

| Monte Carlo Methods | Stochastic search using random modifications; can cross energy barriers effectively | AutoDock, ICM, QXP, Affinity [15] |

| Genetic Algorithms | Evolutionary approach with mutation and crossover operations on encoded degrees of freedom | GOLD, AutoDock, DIVALI, DARWIN [15] |

| Molecular Dynamics | Simulates physical movements of atoms; effective for flexibility but computationally intensive | Used for refinement after docking [15] |

Scoring functions quantify ligand-receptor binding affinity through various physical chemistry principles and empirical data. These include force field-based methods (calculating molecular mechanics energies), empirical scoring functions (using regression-based parameters), and knowledge-based potentials (derived from statistical atom-pair distributions in known structures) [15]. The accurate treatment of receptor flexibility, especially backbone movements, remains a significant challenge, with advanced approaches like Local Move Monte Carlo (LMMC) showing promise for flexible receptor docking problems [15].

Experimental Protocol: Molecular Docking Workflow

A standardized molecular docking protocol typically involves these critical steps:

Target Preparation: Obtain the three-dimensional structure of the target protein from experimental sources (Protein Data Bank) or computational prediction tools (AlphaFold, RaptorX) [19]. Remove water molecules and cofactors unless functionally relevant. Add hydrogen atoms, assign partial charges, and define protonation states of residues appropriate for physiological conditions.

Ligand Preparation: Retrieve or draw the small molecule structure. Generate likely tautomers and protonation states. Optimize the geometry using molecular mechanics or quantum chemical methods. For flexible docking, identify rotatable bonds and generate multiple conformations.

Binding Site Definition: If the binding site is known from experimental data, define the search space around key residues. For novel targets, use cavity detection algorithms (e.g., fpocket) or blind docking approaches [15] [14].

Docking Execution: Select appropriate sampling algorithm and scoring function based on system characteristics. Perform multiple docking runs to ensure adequate sampling of conformational space. Use clustering analysis to identify representative binding poses.

Post-Docking Analysis: Visually inspect highest-ranked poses for key interactions (hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, π-stacking). Quantify interaction energies and compare across compound series. Validate docking protocol by re-docking known crystallographic ligands if available.

Refinement with Molecular Dynamics: Subject top-ranked complexes to molecular dynamics simulations to assess binding stability and incorporate full flexibility [14].

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR): Predictive Modeling of Bioactivity

Theoretical Foundations and Descriptor Systems

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling establishes mathematical relationships between the chemical structure of compounds and their biological activity through molecular descriptors [17]. This approach operates on the fundamental principle that molecular structure encodes all properties necessary for biological activity, and that structurally similar compounds likely exhibit similar biological effects [17]. The methodology formally began in the early 1960s with the seminal work of Hansch and Fujita, who developed a multiparameter approach incorporating hydrophobicity (logP), electronic properties (Hammett constants), and steric effects [17].

Molecular descriptors quantitatively characterize molecular structures across multiple dimensions of complexity:

- 1D Descriptors: Global molecular properties including molecular weight, atom counts, and bond counts [20].

- 2D Descriptors: Topological descriptors encoding molecular connectivity, such as path counts, connectivity indices, and fragment-based descriptors [20].

- 3D Descriptors: Geometrical descriptors capturing molecular shape, volume, and surface properties, along with conformation-dependent features [20].

- 4D Descriptors: Ensemble descriptors accounting for conformational flexibility through molecular dynamics trajectories or multiple conformations [20].

- Quantum Chemical Descriptors: Electronic properties derived from quantum mechanical calculations, including HOMO-LUMO energies, molecular electrostatic potentials, and partial atomic charges [20].

Dimensionality reduction techniques such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) are routinely employed to manage descriptor redundancy and enhance model interpretability [20].

Classical and Machine Learning Approaches in QSAR

QSAR methodologies have evolved from classical statistical approaches to sophisticated machine learning algorithms:

Table 2: QSAR Modeling Techniques and Applications

| Methodology | Key Characteristics | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Classical Statistical Methods | Multiple Linear Regression (MLR), Partial Least Squares (PLS); linear, interpretable models | Preliminary screening, mechanism clarification, regulatory toxicology [20] |

| Machine Learning Approaches | Random Forests, Support Vector Machines (SVM); capture nonlinear relationships, robust with noisy data | Virtual screening, toxicity prediction, lead optimization [20] |

| Deep Learning Frameworks | Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), SMILES-based transformers; automated feature learning from raw structures | De novo drug design, large chemical space exploration [20] |

| Hybrid Models | Integration of classical and machine learning methods; balances interpretability and predictive power | ADMET prediction, multi-parameter optimization [20] |

The machine learning revolution has significantly enhanced QSAR predictive power, with algorithms like Random Forests and Support Vector Machines capable of capturing complex, nonlinear descriptor-activity relationships without prior assumptions about data distribution [20]. Modern developments focus on improving model interpretability through techniques such as SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) and LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations), which help identify descriptors most influential to predictions [20].

Experimental Protocol: QSAR Model Development and Validation

A robust QSAR modeling workflow requires meticulous execution of these steps:

Data Curation and Chemical Space Definition: Compile a structurally diverse set of compounds with consistent biological activity data. Employ Statistical Molecular Design (SMD) principles to ensure comprehensive chemical space coverage [17]. Remove duplicates and compounds with ambiguous activity measurements. Divide data into training (∼80%) and external test (∼20%) sets.

Descriptor Calculation and Preprocessing: Calculate molecular descriptors using software such as DRAGON, PaDEL, or RDKit [20]. Apply preprocessing techniques including normalization, scaling, and variance filtering. Address missing values through imputation or descriptor removal.

Feature Selection: Identify most relevant descriptors using techniques like stepwise regression, genetic algorithms, LASSO regularization, or random forest feature importance [20]. Reduce dimensionality to prevent overfitting and enhance model interpretability.

Model Building: Apply appropriate algorithms based on dataset characteristics and modeling objectives. For small datasets with suspected linear relationships, employ MLR or PLS. For complex, nonlinear relationships, implement machine learning methods like Random Forests or Support Vector Machines.

Model Validation: Assess model performance using multiple strategies:

Model Application and Interpretation: Use validated models to predict activities of new compounds. Interpret descriptor contributions to derive structure-activity insights for lead optimization.

Pharmacophore Modeling: Defining Essential Molecular Features

Core Concepts and Modeling Approaches

A pharmacophore is defined as "a set of structural features in a molecule recognized at a receptor site, responsible for the molecule's biological activity" [17]. These features include hydrogen bond donors and acceptors, charged or ionizable groups, hydrophobic regions, and aromatic rings, along with their precise three-dimensional spatial arrangement [16]. Pharmacophore modeling can be performed through two primary approaches: structure-based and ligand-based methods.

Structure-based pharmacophore modeling utilizes the three-dimensional structure of a target protein, often complexed with a ligand, to identify key interaction features within the binding site [16]. The process involves analyzing the binding pocket to determine favorable locations for specific molecular interactions, such as hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic contacts, and electrostatic interactions [16]. These features are then integrated into a pharmacophore model that represents the essential characteristics a ligand must possess for effective binding.

Ligand-based pharmacophore modeling is employed when the protein structure is unknown but information about active ligands is available [16] [17]. This approach identifies common chemical features and their spatial arrangements across a set of known active compounds, under the assumption that shared features are essential for biological activity [17]. The method must account for ligand conformational flexibility, often considering multiple low-energy conformations to ensure comprehensive feature mapping [16].

Advanced Applications and Integration with Other Methods

Pharmacophore modeling extends beyond basic virtual screening to diverse applications in drug discovery:

- Side Effect and Off-Target Prediction: Pharmacophore models can identify potential unintended targets by screening against databases of various receptors, helping predict adverse effects early in development [16].

- ADMET Modeling: Pharmacophores aid in predicting absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity properties by modeling interactions with relevant transporters, metabolizing enzymes, and toxicity targets [16].

- Scaffold Hopping: By searching for compounds with similar pharmacophores but different core structures, researchers can identify novel chemical scaffolds with maintained activity, expanding intellectual property opportunities [16].

- Multi-Target Drug Design: Integrated pharmacophore models can represent features required for activity against multiple targets, facilitating the design of polypharmacological agents [16].

The integration of pharmacophore modeling with molecular dynamics simulations has led to the development of dynamic pharmacophore models, which account for protein flexibility and evolving interaction patterns over time, providing more realistic representations of binding interactions [16]. Additionally, machine learning techniques have enhanced pharmacophore mapping algorithms, enabling more effective identification of active compounds against protein targets of interest [16].

Experimental Protocol: Pharmacophore Model Development

A comprehensive pharmacophore modeling workflow involves these critical stages:

Data Preparation: For structure-based approaches, obtain the protein structure from crystallography, NMR, or homology modeling. Prepare the structure by adding hydrogens, assigning charges, and optimizing hydrogen bonding networks. For ligand-based approaches, compile a diverse set of confirmed active compounds with measured activities. Generate multiple low-energy conformations for each ligand using systematic search, Monte Carlo, or molecular dynamics methods.

Feature Identification: Define the chemical features essential for molecular recognition. Common features include:

- Hydrogen bond donors and acceptors (represented as vectors or projected points)

- Hydrophobic and aromatic features (spheres or volumes)

- Ionizable groups (positive/negative ionizable features)

- Exclusion volumes (regions sterically forbidden by the protein) [16]

Model Generation: For structure-based models, analyze the binding site to identify locations where specific interactions would be favorable. For ligand-based models, align active conformations and identify common features with conserved spatial relationships. Select a subset of features that best explains the activity data while maintaining model specificity.

Model Validation: Assess model quality using several approaches:

- Decoy Sets: Screen databases containing known actives and inactives to evaluate retrieval rates [16].

- Statistical Measures: Calculate sensitivity (ability to identify actives) and specificity (ability to reject inactives) [16].

- External Test Sets: Use compounds not included in model generation to evaluate predictive power.

Virtual Screening and Hit Identification: Employ validated models to screen large chemical databases (e.g., ZINC, ChEMBL). Use the model as a 3D search query to identify compounds matching the pharmacophore pattern. Apply post-processing filters based on physicochemical properties, drug-likeness, and structural novelty.

Experimental Verification: Select top-ranked compounds for biological testing to validate model predictions. Iteratively refine the model based on experimental results to improve performance.

Integrated Applications in Oncology Drug Discovery

Synergistic Workflows in Cancer Therapeutics

The true power of computational drug discovery emerges when molecular docking, QSAR, and pharmacophore modeling are integrated into synergistic workflows. These integrated approaches are particularly valuable in oncology, where the complexity of cancer mechanisms demands multi-faceted strategies [18]. A representative example includes the development of Formononetin (FM) as a potential liver cancer therapeutic, where network pharmacology identified potential targets, molecular docking evaluated binding interactions, and molecular dynamics simulations confirmed binding stability—with all predictions subsequently validated through metabolomics analysis and experimental assays [18].

Another compelling application involves acute myeloid leukemia treatment, where QSAR modeling of 64 compounds targeting Mcl-1 protein identified promising candidates, followed by molecular docking to study drug-target interactions and identify SEC11C and EPPK1 as novel therapeutic targets [21]. This integrated approach significantly compressed the drug discovery timeline from years to hours while reducing costs [21].

For challenging targets like immune checkpoints (PD-1/PD-L1) and metabolic enzymes (IDO1) in cancer immunotherapy, hybrid methods have proven particularly valuable. Structure-based pharmacophore models derived from crystal structures can identify initial hits, which are then optimized using QSAR models that incorporate electronic and steric parameters crucial for disrupting these protein-protein interactions [22].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Computational Tools

Table 3: Key Software and Databases for Computational Drug Discovery

| Tool Category | Representative Resources | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Docking Software | AutoDock, GOLD, DOCK, FlexX, ICM | Binding pose prediction, virtual screening, binding affinity estimation [15] |

| QSAR Modeling Platforms | QSARINS, Build QSAR, DRAGON, PaDEL, RDKit | Descriptor calculation, model development, validation [20] |

| Pharmacophore Modeling Tools | LigandScout, Phase, MOE | Structure-based and ligand-based pharmacophore generation, virtual screening [16] |

| Protein Structure Prediction | AlphaFold, RaptorX | Target structure determination when experimental structures unavailable [19] |

| Chemical Databases | ZINC, ChEMBL, PubChem | Compound libraries for virtual screening, structural information for modeling [16] |

Workflow Visualization: Integrated Computational Approach

The following diagram illustrates a typical integrated computational workflow in oncology drug discovery, showing how molecular docking, QSAR, and pharmacophore modeling complement each other:

Molecular docking, QSAR, and pharmacophore modeling represent three foundational computational methodologies that have become indispensable in modern oncology drug discovery. While each approach offers distinct capabilities—docking for predicting atomic-level interactions, QSAR for establishing quantitative activity relationships, and pharmacophore modeling for identifying essential molecular features—their integration creates synergistic workflows that accelerate the identification and optimization of therapeutic candidates [15] [20] [16]. As cancer research continues to evolve toward personalized medicine and targeted therapies, these computational tools will play increasingly critical roles in navigating the complexity of tumor biology and designing effective, selective therapeutics. The ongoing incorporation of artificial intelligence and machine learning approaches promises to further enhance the predictive power and application scope of these established methodologies, solidifying their position as essential components of the drug discovery pipeline [22] [20].

Cancer remains one of the leading causes of mortality worldwide, with more than 19 million new cases and nearly 10 million deaths reported in 2020 [23]. The disease presents a formidable challenge due to its intrinsic complexity and heterogeneity, characteristics that necessitate innovative approaches in drug discovery and development. Tumor heterogeneity means that treatments effective in one subset of patients may fail in another, while resistance mechanisms, whether intrinsic or acquired, limit long-term efficacy [23]. Furthermore, cancer biology is heavily influenced by the tumor microenvironment (TME), immune system interactions, and epigenetic factors, making drug response prediction exceptionally complex [23].

Conventional approaches to drug discovery, which typically rely on high-throughput screening and incremental modifications of existing compounds, are poorly equipped to manage this complexity. These strategies are labor-intensive and costly, with an estimated 90% of oncology drugs failing during clinical development [23]. This staggering attrition rate underscores the urgent need for new paradigms capable of integrating vast datasets and generating predictive insights. It is within this context that computational approaches, particularly Computer-Aided Drug Design (CADD), have emerged as transformative tools. CADD enhances researchers' ability to develop cost-effective and resource-efficient solutions by leveraging advanced computational power to explore chemical spaces beyond human capabilities and predict molecular properties and biological activities with remarkable efficiency [4].

Computational Frameworks for Addressing Heterogeneity

Core CADD Methodologies in Oncology

Computer-Aided Drug Design (CADD) represents a suite of computational technologies that accelerate and optimize the drug development process by simulating the structure, function, and interactions of target molecules with ligands [2] [19]. In oncology, these approaches are particularly valuable for managing disease complexity. CADD encompasses several complementary methodologies:

Structure-Based Drug Design (SBDD): This approach leverages the three-dimensional structural information of macromolecular targets to identify key binding sites and interactions, designing drugs that can interfere with critical biological pathways [2] [19]. Techniques include molecular docking, which predicts the binding modes of small molecules to targets, and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, which refine docking results by simulating atomic motions over time to evaluate binding stability under near-physiological conditions [2] [19].

Ligand-Based Drug Design (LBDD): When structural information of the target is unavailable, LBDD guides drug optimization by studying the structure-activity relationships (SARs) of known ligands [2] [19]. Key methods include quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) modeling, which predicts the activity of new molecules based on mathematical models correlating chemical structures with biological activity [2] [19].

Virtual Screening (VS): This technique computationally filters large compound libraries to identify candidates with desired activity profiles, significantly reducing the number of compounds requiring physical testing [2] [19]. High-throughput virtual screening (HTVS) extends these approaches by combining docking, pharmacophore modeling, and free-energy calculations to enhance efficiency [2] [19].

The following diagram illustrates how these computational methods integrate into a cohesive drug discovery workflow designed to address cancer heterogeneity:

The Rise of Artificial Intelligence in Cancer Drug Discovery

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has emerged as an advanced subset within the broader CADD framework, explicitly integrating machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) into key steps of the discovery pipeline [2] [23] [4]. AI-driven drug discovery (AIDD) represents the progression from traditional computational methods toward more intelligent and adaptive paradigms capable of managing the multi-dimensional complexity of cancer biology [4].

In target identification, AI enables integration of multi-omics data—including genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics—to uncover hidden patterns and identify promising targets that might be missed by traditional methods [23]. For instance, ML algorithms can detect oncogenic drivers in large-scale cancer genome databases such as The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), while deep learning can model protein-protein interaction networks to highlight novel therapeutic vulnerabilities [23].

In drug design and lead optimization, deep generative models such as variational autoencoders (VAEs) and generative adversarial networks (GANs) can create novel chemical structures with desired pharmacological properties, significantly accelerating what has traditionally been a slow, iterative process [2] [23]. Reinforcement learning further optimizes these structures to balance potency, selectivity, solubility, and toxicity [23]. The impact is substantial: companies such as Insilico Medicine and Exscientia have reported AI-designed molecules reaching clinical trials in record times, with one preclinical candidate for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis developed in under 18 months compared to the typical 3–6 years [23].

Table 1: AI Applications in Addressing Cancer Complexity

| AI Technology | Specific Application in Oncology | Reported Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Machine Learning (ML) | Analysis of multi-omics data for target identification; Predictive modeling of drug response | Identifies novel targets and biomarker signatures from complex datasets |

| Deep Learning (DL) | Analysis of histopathology images; De novo molecular design | Reveals histomorphological features correlating with treatment response; Generates novel chemical structures |

| Natural Language Processing (NLP) | Mining unstructured biomedical literature and clinical notes | Extracts knowledge for hypothesis generation and clinical trial optimization |

| Reinforcement Learning | Optimization of chemical structures for improved drug properties | Balances potency, selectivity, and toxicity profiles |

Experimental Workflows and Research Protocols

Integrated Preclinical Screening Models

To effectively translate computational predictions into viable therapies, researchers employ a cascade of increasingly complex preclinical models that mirror tumor heterogeneity and microenvironmental influences. Each model system offers distinct advantages and limitations in recapitulating the complexity of human cancers [24].

Cell lines represent the initial high-throughput screening platform, providing reproducible and standardized testing conditions for evaluating drug candidates against multiple cancer types and diverse genetic backgrounds [24]. Applications include drug efficacy testing, high-throughput cytotoxicity screening, in vitro drug combination studies, and colony-forming assays [24]. However, their utility is limited by poor representation of tumor heterogeneity and the tumor microenvironment [24].

Organoids have emerged as a revolutionary intermediate model, described by Nature as "invaluable tools in oncology research" [24]. Grown from patient tumor samples, these 3D structures faithfully recapitulate the phenotypic and genetic features of the original tumor, offering more clinically predictive data than traditional 2D cultures [24]. In April 2025, the FDA announced that animal testing requirements for monoclonal antibodies and other drugs would be reduced, refined, or potentially replaced entirely with advanced approaches including organoids, signaling their growing importance in the regulatory landscape [24].

Patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models, created by implanting patient tumor tissue into immunodeficient mice, represent the most clinically relevant preclinical models and are considered the gold standard of preclinical research [24]. These models preserve key genetic and phenotypic characteristics of patient tumors, including aspects of the tumor microenvironment, enabling more accurate prediction of clinical responses [24].

The following workflow illustrates how these models integrate into a comprehensive drug discovery pipeline:

Biomarker Discovery Through Integrated Approaches

The early identification and validation of biomarkers is crucial to addressing cancer heterogeneity in drug development, as biomarkers help identify patients with targetable biological features, track drug efficacy, and detect early indicators of treatment response [24]. An integrated, multi-stage approach leveraging different model systems provides a structured framework for biomarker discovery:

Hypothesis Generation with PDX-Derived Cell Lines: Researchers use PDX-derived cell lines for large-scale screening to identify potential correlations between genetic mutations and drug responses, generating initial sensitivity or resistance biomarker hypotheses [24].

Hypothesis Refinement with Organoids: During organoid testing, biomarker hypotheses are refined and validated using these more complex 3D tumor models. Multiomics approaches—including genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics—help identify more robust biomarker signatures [24].

Preclinical Validation with PDX Models: PDX models provide the final preclinical validation of biomarker hypotheses before clinical trials. Their preservation of tumor architecture and heterogeneity gives researchers a deeper understanding of biomarker distribution within heterogeneous tumor environments [24].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Oncology Drug Discovery

| Research Tool | Function and Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Line Panels | Initial high-throughput drug screening; Drug combination studies | 500+ genomically diverse cancer cell lines; Well-characterized collections available |

| Organoid Biobanks | Drug response investigation; Immunotherapy evaluation; Predictive biomarker identification | Faithfully recapitulate original tumor genetics and phenotype; FDA-recognized model |

| PDX Model Collections | Biomarker discovery and validation; Clinical stratification; Drug combination strategies | Preserve tumor architecture and TME; Considered gold standard for preclinical research |

| Multiomics Platforms | Genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic analysis for biomarker signature identification | Integrates diverse data types to identify robust biomarker signatures |

Clinical Translation and Regulatory Landscape

Recent FDA Approvals and Trends

The first half of 2025 provided compelling evidence of progress in addressing cancer complexity through targeted approaches. The FDA's Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) approved 16 novel drugs, with half (8 drugs) targeting various cancers [24]. These approvals reflect important innovations in cancer therapy, demonstrating an increased focus on targeted therapies, immunologically driven approaches, and personalized oncology strategies [24].

Notable approvals included new antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) for solid tumors, small molecule targeted therapies, and biomarker-guided approaches representing significant advances in precision medicine [24]. Several therapeutics addressing rare cancers also gained approval, including the first treatment for KRAS-mutated ovarian cancer and a non-surgical treatment option for patients with neurofibromatosis type 1 [24].

Table 3: Selected FDA Novel Cancer Drug Approvals in H1 2025

| Drug Name | Approval Date | Indication | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Avmapki Fakzynja Co-Pack (avutometinib and defactinib) | 5/8/2025 | KRAS-mutated recurrent low-grade serous ovarian cancer (LGSOC) | First treatment for KRAS-mutated ovarian cancer |

| Gomekli (mirdametinib) | 2/11/2025 | Neurofibromatosis type 1 with symptomatic plexiform neurofibromas | Non-surgical treatment option |

| Emrelis (telisotuzumab vedotin-tllv) | 5/14/2025 | Non-squamous NSCLC with high c-Met protein overexpression | Targets specific protein overexpression |

| Ibtrozi (taletrectinib) | 6/11/2025 | Locally advanced or metastatic ROS1-positive non-small cell lung cancer | Targets specific genetic driver (ROS1) |

AI and CADD in Clinical Trial Optimization

Clinical trials represent one of the most expensive and time-consuming phases of drug development, with patient recruitment remaining a significant bottleneck—up to 80% of trials fail to meet enrollment timelines [23]. AI and CADD approaches are increasingly deployed to optimize this critical phase:

Patient Identification: AI algorithms can mine electronic health records (EHRs) and real-world data to identify eligible patients, significantly accelerating recruitment [23].

Trial Outcome Prediction: Predictive models can simulate trial outcomes, optimizing design by selecting appropriate endpoints, stratifying patients, and reducing required sample sizes [23].

Adaptive Trial Designs: AI-driven real-time analytics enable modifications in dosing, stratification, or drug combinations during the trial based on accumulating data [23].

Natural language processing (NLP) tools further enhance clinical trial efficiency by matching trial protocols with institutional patient databases, creating a more seamless integration between computational prediction and clinical execution [23].

The oncology imperative demands sophisticated strategies that directly address the fundamental challenges of cancer complexity and heterogeneity. Computational approaches, particularly CADD and its advanced subset AIDD, provide powerful frameworks for managing this complexity across the entire drug discovery and development pipeline. From initial target identification through clinical trial optimization, these technologies leverage increasing computational power and algorithmic sophistication to explore chemical and biological spaces beyond human capabilities [4].

The continued evolution of these fields promises even greater integration of computational and experimental approaches. Advances in multi-modal AI—capable of integrating genomic, imaging, and clinical data—promise more holistic insights into cancer biology [23]. Federated learning approaches, which train models across multiple institutions without sharing raw data, can overcome privacy barriers while enhancing data diversity [23]. The emerging concept of digital twins—virtual patient simulations—may eventually allow for in silico testing of drug responses before actual clinical trials [23].

Despite these promising developments, challenges remain in data quality, model interpretability, and regulatory acceptance. The translation of computational predictions into successful wet-lab experiments often proves more complex than anticipated, and the "black box" nature of some AI algorithms continues to limit mechanistic insights [23] [4]. However, the successes achieved to date, combined with the urgent unmet need in oncology, signal an irreversible paradigm shift toward computational-aided approaches in cancer drug discovery. As these technologies mature, their integration throughout the drug development pipeline will likely become standard practice, ultimately benefiting cancer patients worldwide through earlier access to safer, more effective, and highly personalized therapies.

The field of oncology drug discovery has undergone a profound transformation, evolving from reliance on rudimentary computer-assisted models to sophisticated artificial intelligence (AI)-driven platforms. This evolution represents a fundamental paradigm shift from serendipitous discovery and labor-intensive trial-and-error approaches to a precision engineering science powered by computational intelligence [23]. The journey began with early computer-aided drug design (CADD) systems that provided foundational tools for molecular modeling, and has now advanced to integrated AI platforms capable of de novo molecule design, dramatically accelerating the development of targeted cancer therapies [25] [26]. This whitepaper chronicles this technological evolution, examining the historical context, key transitional phases, and current state of AI-enhanced platforms that are reshaping the basic principles of computer-aided drug design in oncology research. The integration of AI has cultivated a strong interest in developing and validating clinical utilities of computer-aided diagnostic models, creating new possibilities for personalized cancer treatment [27]. Within oncology specifically, AI is redefining the traditional drug discovery pipeline by accelerating discovery, optimizing drug efficacy, and minimizing toxicity through groundbreaking advancements in molecular modeling, simulation techniques, and identification of novel compounds [28].

The Early Era: Foundation of Computer-Aided Drug Design

The historical foundation of computer-aided approaches in medical applications began in the mid-1950s with early discussions about using computers for analyzing radiographic abnormalities [29]. However, the limited computational power and primitive image digitization equipment of that era constrained widespread implementation. The 1960s marked a pivotal turning point with the introduction of Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models, which represented the first systematic approach to computer-based drug development [25]. These early models established mathematical relationships between a compound's chemical structure and its biological activity, enabling rudimentary predictions of pharmacological properties.

The 1980s witnessed significant advancement with the emergence of physics-based Computer-Aided Drug Design (CADD), which incorporated principles of molecular mechanics and quantum chemistry to simulate drug-target interactions [25]. This period saw the development of sophisticated simulation techniques that could model the three-dimensional structure of target proteins and predict how potential drug molecules might bind to them. By the 1990s, these technologies had matured sufficiently to support commercial CADD platforms like Schrödinger, which began to see broader adoption across the pharmaceutical industry [25] [30].

Throughout this early era, cancer research relied heavily on traditional experimental models including cancer cell lines, patient-derived xenografts (PDXs), and genetically engineered mouse models (GEMMs) [31]. These models formed the essential laboratory foundation for validating computational predictions, though each came with significant limitations in accurately recapitulating human tumor biology and drug response. The workflow during this period remained largely sequential, with computational methods serving as supplemental tools rather than driving the discovery process.

The Transition: Rise of Machine Learning and Data-Driven Approaches

The 2010s marked a critical transitional phase with the rise of deep learning and the emergence of specialized AI drug discovery startups [25]. This period was characterized by the convergence of three key enabling factors: the exponential growth of biological data, advances in machine learning algorithms, and increased computational power through cloud computing and graphics processing units (GPUs). Traditional drug discovery pipelines were constrained by high attrition rates, particularly in oncology, where tumor heterogeneity, resistance mechanisms, and complex microenvironmental factors made effective targeting especially challenging [23].

Machine learning approaches began to demonstrate significant value across multiple aspects of the drug discovery pipeline. Supervised learning algorithms, including support vector machines (SVMs) and random forests, were applied to quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) modeling, toxicity prediction, and virtual screening [22]. Unsupervised learning techniques such as k-means clustering and principal component analysis (PCA) enabled exploratory analysis of chemical spaces and identification of novel compound classes [22]. The integration of these data-driven methods with established physics-based CADD approaches created powerful hybrid systems that leveraged the strengths of both methodologies [25].

This transitional period also saw the emergence of early deep learning architectures, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and recurrent neural networks (RNNs), which demonstrated superior capabilities in processing complex structural and sequential data [22]. These technologies began to outperform traditional methods in predicting molecular properties and binding affinities. A landmark achievement during this era was Insilico Medicine's demonstration in 2019, advancing an AI-designed treatment for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis into Phase 2 clinical trials [25]. This achievement provided compelling validation of AI's potential to accelerate the entire drug development process.

The Current Era: AI-Enhanced Platforms and Integrated Workflows

By 2025, AI-driven drug discovery has firmly established itself as a cornerstone of the biotech industry, with large-scale projects emerging rapidly across the globe [25]. The current era is characterized by fully integrated AI platforms that leverage multiple complementary technologies to streamline the entire drug discovery pipeline. The core AI architectures that define this modern approach include generative models, predictive algorithms, and sophisticated data integration systems.

Leading AI Platforms and Technologies

Table 1: Leading AI-Driven Drug Discovery Platforms in 2025

| Platform/Company | Core AI Approach | Key Oncology Applications | Clinical Stage Achievements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exscientia | Generative AI + Automated Precision Chemistry | Immuno-oncology, CDK7 inhibitors, LSD1 inhibitors | First AI-designed drug (DSP-1181) entered Phase I trials in 2020; Multiple clinical compounds designed [30] |

| Insilico Medicine | Generative AI + Target Identification | Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, Oncology targets | Phase IIa results for ISM001-055; Target-to-clinic in 18 months for IPF program [30] |

| Recursion | Phenomics-First AI + High-Content Screening | Various oncology indications | Merger with Exscientia creating integrated AI platform; Extensive phenomics database [30] |

| Schrödinger | Physics-Based ML + Molecular Simulation | TYK2 inhibitors, Kinase targets | Zasocitinib (TAK-279) advanced to Phase III trials [30] |

| BenevolentAI | Knowledge-Graph + Target Discovery | Glioblastoma, Oncology targets | AI-predicted novel targets in glioblastoma [23] [30] |

The current AI toolkit encompasses several specialized technologies that work in concert across the drug discovery pipeline. Generative models including variational autoencoders (VAEs) and generative adversarial networks (GANs) enable de novo molecular design by learning the underlying patterns and features of known drug-like molecules [22]. These systems can create novel chemical structures with optimized properties for specific therapeutic targets. Predictive algorithms leverage deep learning to forecast absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) properties, enabling virtual screening of millions of compounds before synthesis [22] [32]. Large language models (LLMs) adapted for chemical and biological data can process scientific literature, predict protein structures, and suggest molecular modifications [32].

The integration of these technologies has created unprecedented efficiencies in oncology drug discovery. AI-driven platforms can now evaluate millions of virtual compounds in hours rather than years, with reported discovery timelines reduced from 10+ years to potentially 3-6 years [32]. Success rates in Phase I trials have shown remarkable improvement, with AI-designed drugs demonstrating 80-90% success rates compared to 40-65% for traditional approaches [32]. Companies like Exscientia report in silico design cycles approximately 70% faster and requiring 10x fewer synthesized compounds than industry norms [30].

AI-Driven Workflow in Modern Oncology Drug Discovery

The following diagram illustrates the integrated, AI-driven workflow that characterizes modern oncology drug discovery:

Diagram 1: AI-Driven Drug Discovery Workflow

This workflow demonstrates how modern AI platforms seamlessly integrate multiple data modalities and AI approaches to create an efficient, iterative discovery process. The foundation models, including protein and chemical language models, serve as the underlying infrastructure that powers specific discovery tasks from target identification through clinical trial optimization.

Technical Methodologies: AI Approaches and Experimental Protocols

Core AI Architectures and Their Applications

Table 2: Core AI Architectures in Modern Drug Discovery

| AI Architecture | Mechanism | Oncology Applications | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) | Generator creates molecules; Discriminator evaluates authenticity | De novo design of kinase inhibitors, immune checkpoint modulators | Generates novel chemical structures with optimized properties [22] |

| Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) | Encoder-decoder architecture learning compressed molecular representation | Scaffold hopping for improved selectivity, multi-parameter optimization | Continuous latent space enables smooth molecular interpolation [22] |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | Message passing between atomic nodes in molecular graphs | Property prediction, binding affinity estimation, reaction prediction | Naturally represents molecular structure and bonding relationships [22] [32] |

| Reinforcement Learning (RL) | Agent receives rewards for desired molecular properties | Multi-objective optimization balancing potency, selectivity, ADMET | Optimizes compounds toward complex, multi-parameter goals [23] [22] |

| Transformers & Large Language Models (LLMs) | Self-attention mechanisms processing sequential data | Protein structure prediction, molecular generation via SMILES, literature mining | Captures long-range dependencies in sequences and structures [32] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol for AI-Driven Discovery

A standardized protocol for AI-driven oncology drug discovery has emerged, incorporating both computational and experimental components:

Phase 1: Target Identification and Validation

- Multi-omic Data Integration: Collect and harmonize genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and epigenomic data from public repositories (TCGA, DepMap) and proprietary sources [23] [28].

- Causal AI Analysis: Apply causal machine learning models to distinguish driver mutations from passenger mutations in cancer pathways [32].

- Network Medicine Approaches: Construct protein-protein interaction networks and disease modules to identify novel therapeutic targets [23].

- Experimental Validation: Confirm target druggability using CRISPR screens, patient-derived organoids (PDOs), and patient-derived xenografts (PDXs) [31].

Phase 2: Generative Molecular Design

- Define Target Product Profile: Establish desired properties including potency, selectivity, permeability, and metabolic stability [30] [22].

- Generative Chemical Design: Implement conditional VAEs or GANs to explore chemical space constrained by target properties [22].

- Multi-parameter Optimization: Use reinforcement learning with reward functions balancing multiple property objectives [22].

- Synthetic Accessibility Assessment: Apply retrosynthesis tools (e.g., AIZYNTH, Molecular Transformer) to evaluate synthetic feasibility [30].

Phase 3: Virtual Screening and Prioritization

- Physics-Based Docking: Employ molecular docking simulations (e.g., Schrödinger Glide, AutoDock) for binding pose prediction [30].

- Deep Learning Scoring Functions: Implement CNN-based or GNN-based scoring functions trained on structural interaction data [22].

- ADMET Prediction: Utilize deep learning models (e.g., Random Forest, XGBoost) for in silico prediction of pharmacokinetics and toxicity [22] [32].

- Compound Prioritization: Apply ensemble methods to rank compounds based on integrated assessment of multiple criteria [30].

Phase 4: Experimental Testing and Iteration

- Automated Synthesis: Utilize robotic synthesis platforms (e.g., Exscientia's AutomationStudio) for high-throughput compound production [30].