Computational Strategies for Undruggable Cancer Targets: From AI Design to Clinical Translation

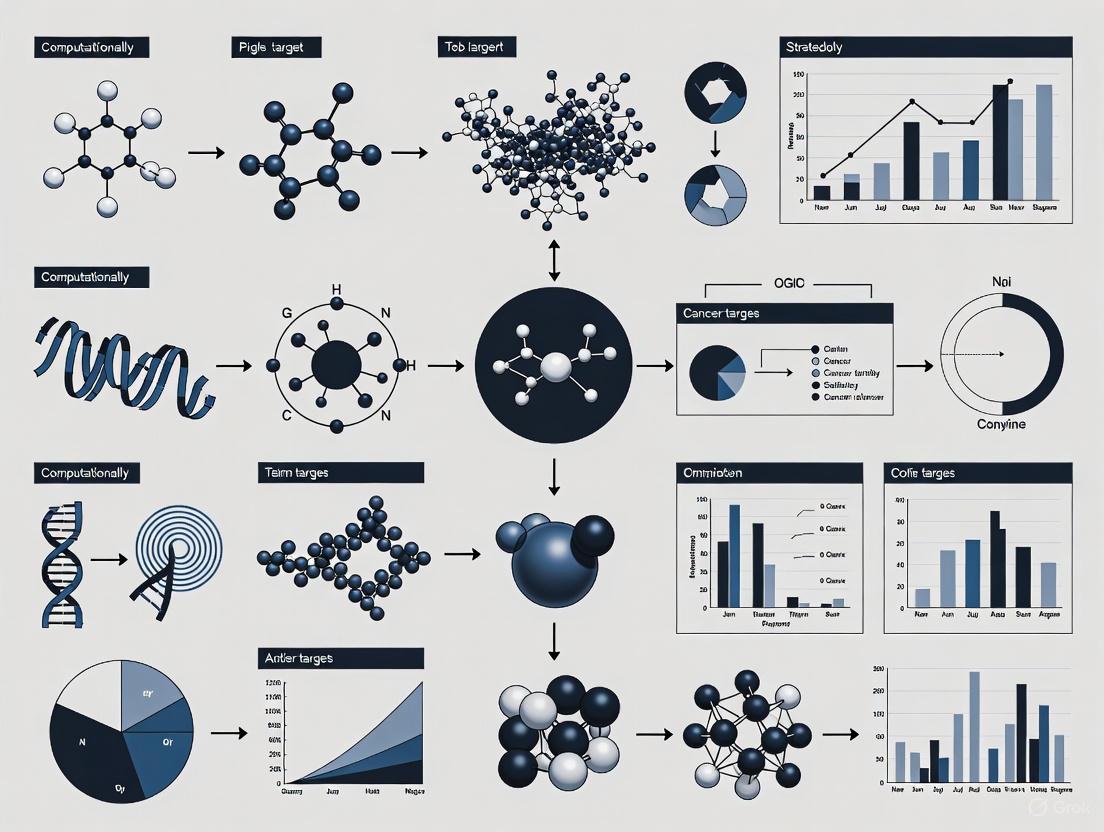

This article provides a comprehensive overview of cutting-edge computational and AI-driven strategies developed to target traditionally undruggable cancer proteins.

Computational Strategies for Undruggable Cancer Targets: From AI Design to Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of cutting-edge computational and AI-driven strategies developed to target traditionally undruggable cancer proteins. It explores the foundational biology of targets like KRAS, MYC, and p53, and details innovative methodologies, including generative AI for binder design, quantum computing-assisted screening, and allosteric inhibition. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, the content also addresses critical challenges in optimization, validation, and clinical translation, offering a comparative analysis of leading platforms and their paths toward transforming cancer therapeutics.

Deconstructing the Undruggable Problem: Target Classes and Biological Challenges

FAQ: What does "undruggable" mean in cancer research?

In cancer research, "undruggable" refers to proteins that are clinically meaningful therapeutic targets but are exceptionally difficult to drug using conventional drug design strategies [1] [2]. These targets are often characterized by a lack of defined, deep hydrophobic pockets on their surface that small-molecule drugs can bind to, making rational drug design a significant challenge [1] [3]. It is important to note that the term is evolving, with many now preferring "difficult to drug" or "yet to be drugged," as recent advances have successfully targeted some of these proteins [2].

FAQ: What are the main classes of undruggable targets?

The primary categories of undruggable targets, along with their key challenges and representative examples, are summarized in the table below [1] [3].

Table 1: Major Classes of Undruggable Cancer Targets

| Target Class | Key Druggability Challenge | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Small GTPases | Lack of pharmacologically targetable pockets; extremely high affinity for its natural substrate (GTP) [1] [3]. | KRAS, HRAS, NRAS [1] |

| Transcription Factors (TFs) | Structural heterogeneity and lack of tractable binding sites; function often relies on protein-protein interactions [1] [3]. | p53, MYC, STAT3 [1] [4] |

| Phosphatases | Highly conserved, positively charged active sites; structural similarity leads to low selectivity and potential toxicity [1] [3]. | PTPs (Protein Tyrosine Phosphatases) [1] |

| Protein-Protein Interactions (PPIs) | Large, flat, and relatively featureless interaction surfaces that are difficult for small molecules to disrupt [1] [3]. | B-cell lymphoma-2 (Bcl-2) family [1] |

FAQ: What specific characteristics make a protein "undruggable"?

The elusive nature of these targets can be distilled into four key structural and functional characteristics.

Table 2: Core Characteristics of Undruggable Proteins

| Characteristic | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Lack of Ligand-Binding Pockets | The protein surface is smooth and lacks deep, defined hydrophobic pockets or cavities that small-molecule inhibitors can bind to with high affinity [1] [3]. | KRAS was considered undruggable for decades due to its shallow, polar surface with no obvious binding sites for drugs [1]. |

| Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) Interfaces | Their biological function is mediated by large, flat surfaces that interact with other proteins. These PPI interfaces are difficult to disrupt with conventional small molecules, which are better at targeting deep pockets [3] [2]. | Transcription factors like MYC exert their function by binding to other proteins and DNA, presenting a challenging PPI interface for drug discovery [1]. |

| Highly Conserved Active Sites | The active site (e.g., for substrate or GTP binding) is highly similar among members of the same protein family, making it nearly impossible to develop a selective inhibitor that hits only one member without affecting others, leading to potential side effects [3]. | Phosphatases share a high degree of structural similarity in their active sites, hindering the development of selective drugs [1]. |

| Intrinsically Disordered Regions or Unknown 3D Structure | The protein lacks a stable, folded three-dimensional structure or its tertiary structure is unknown, which prevents structure-based drug design [3]. | Many transcription factors contain intrinsically disordered regions, making them highly dynamic and lacking stable binding cavities [1] [3]. |

The following diagram illustrates the relationship between these core characteristics and the resulting druggability challenges.

Troubleshooting Guide: My target is considered "undruggable." What computational strategies can I employ?

When faced with a seemingly undruggable target, shifting from traditional drug discovery paradigms to innovative computational strategies is crucial. The following workflow outlines a modern computational approach to this challenge.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: In Silico Workflow for Identifying Degraders or PPI Inhibitors

This protocol leverages the DrugAppy framework, an end-to-end deep learning tool that integrates multiple computational models [5].

Target Preparation:

- Obtain the 3D structure of your target protein from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) or generate a high-confidence predicted structure using AlphaFold2.

- Use computational tools to prepare the structure: add hydrogen atoms, assign partial charges, and define protonation states.

Virtual Screening & AI-Driven Molecule Generation:

- Perform High-Throughput Virtual Screening (HTVS) against the target using docking programs like SMINA or GNINA (integrated in DrugAppy) to screen millions of compounds from libraries like VirtualFlow [5] [6].

- Alternatively, or in parallel, employ a generative AI engine (e.g., Chemistry42) to design novel chemical entities from scratch. These models can be trained on custom datasets of known binders or degraders for your target family [6].

Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation:

- Take the top-ranking hits from virtual screening or AI generation and subject them to Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations using software like GROMACS (as used in DrugAppy) [5].

- Run simulations for at least 100-200 nanoseconds to assess the stability of the ligand-target complex, binding free energy, and key molecular interactions under near-physiological conditions.

AI-Based Property Prediction:

- Use publicly available or proprietary AI models to predict key parameters for the final candidate molecules. These include pharmacokinetics (absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion), selectivity, and potential in vitro activity [5].

Protocol 2: Computational Identification of Novel Allosteric Sites

This methodology is crucial for targeting proteins like KRAS, where the active site is not druggable [1] [3].

Structure Analysis:

- Analyze multiple crystal structures of the target (e.g., in different nucleotide states: GDP-bound vs. GTP-bound for KRAS) to identify conformational changes and potential cryptic pockets [1].

Pocket Detection:

- Use computational tools to detect and characterize potential binding pockets on the protein surface beyond the active site.

Consensus Allosteric Site Prediction:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools and Reagents for Targeting Undruggable Proteins

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Application | Use Case in Undruggable Targets |

|---|---|---|

| Generative AI (e.g., Chemistry42) | AI-driven de novo design of novel chemical entities targeting specific proteins [6]. | Designed novel covalent inhibitors for KRAS by screening and optimizing millions of potential molecules [6]. |

| PROTAC Molecule | Bifunctional molecule that recruits an E3 ubiquitin ligase to a target protein, leading to its degradation by the proteasome [3]. | Used to degrade oncogenic proteins like KRASG12C, effectively inhibiting downstream signaling even for proteins without a classical active site [3]. |

| Covalent Inhibitor Probe (e.g., ARS-1620) | Small molecule that forms a permanent covalent bond with a specific amino acid residue (e.g., cysteine) on the target protein [3]. | Served as a chemical probe to validate the druggability of the KRASG12C allosteric pocket and was used as a warhead for developing PROTAC degraders [3]. |

| Covalent Docking Protocols | Computational method to predict the binding mode and reactivity of covalent inhibitors [7]. | Key for the rational design of covalent drugs, such as the KRASG12C inhibitor Sotorasib, by simulating the covalent bond formation with Cys12 [1] [7]. |

| Quantum Computing Hybrid Models | Leverages quantum computing combined with AI to model complex molecular interactions beyond the reach of classical computers [6]. | Used as a proof-of-principle to identify novel molecules that interact with KRAS, showing potential to accelerate early drug discovery [6]. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

KRAS-Targeting Experiments

Q1: Our KRAS(G12C) inhibitor shows promising initial activity in cell lines, but resistance develops quickly. What are the primary mechanisms we should investigate?

Resistance to KRAS(G12C) inhibitors often occurs through reactivation of the MAPK signaling pathway or secondary KRAS mutations. The table below outlines common mechanisms and suggested experimental approaches to diagnose them [8] [9] [10].

| Resistance Mechanism | Description | Experimental Validation Methods |

|---|---|---|

| On-Target Secondary Mutations | Emergence of mutations (e.g., Y96D, R68S, H95D) that interfere with drug binding [9]. | - Use Sanger sequencing or NGS to sequence the KRAS gene after resistance emerges. |

| Bypass Signaling via RTKs | Upregulation or activation of Receptor Tyrosine Kinases (e.g., EGFR, MET) reactivates MAPK/PI3K signaling despite KRAS inhibition [10]. | Perform western blotting to assess phosphorylation levels of EGFR, MET, ERK, and AKT. |

| KRAS Amplification | Increased copy number of the mutant KRAS gene [9]. | - Use qPCR or FISH to measure KRAS gene copy number. |

| Altered KRAS Cycling | Mutations in downstream effectors (e.g., BRAF, MEK) or upstream regulators (e.g., NF1 loss) maintain pathway activity [8] [9]. | - Utilize RNA-Seq to identify transcriptomic changes in the MAPK pathway. |

Q2: For pancreatic cancer research, the predominant KRAS mutation is G12D, not G12C. What direct targeting strategies are available for KRAS(G12D)?

Your observation is correct; KRAS(G12D) dominates in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), present in approximately 40% of cases [9]. Since the G12D mutation does not create a cysteine for covalent targeting, alternative strategies are required.

- Non-Covalent Inhibitors: The most advanced research compound is MRTX1133, a non-covalent inhibitor that selectively targets the inactive, GDP-bound state of KRAS(G12D). It exhibits high potency in preclinical PDAC models [9].

- PROTAC Degraders: Proteolysis Targeting Chimeras (PROTACs) are bifunctional molecules that recruit an E3 ubiquitin ligase to the target protein, leading to its degradation by the proteasome. This strategy is being explored to degrade KRAS(G12D) entirely, not just inhibit it [3] [11].

- Immunotherapy Approaches: KRAS(G12D)-specific vaccines are under investigation. These vaccines aim to stimulate the patient's own T-cells to recognize and eliminate tumor cells presenting the G12D neoantigen [9].

Experimental Protocol: Evaluating Efficacy of a KRAS(G12D) Inhibitor In Vitro

- Cell Line Selection: Use a well-characterized PDAC cell line harboring the KRAS(G12D) mutation (e.g., Capan-2, HPAC).

- Cell Viability Assay: Treat cells with a dose range of the inhibitor (e.g., MRTX1133) for 72 hours. Assess viability using an ATP-based assay (e.g., CellTiter-Glo).

- Downstream Signaling Analysis: Harvest inhibitor-treated and control cells. Perform western blotting to analyze phosphorylation levels of key downstream effectors like ERK (p-ERK) and AKT (p-AKT). Effective inhibition should show a dose-dependent reduction in these phosphoproteins.

- Apoptosis Assay: Confirm induction of cell death via caspase-3/7 activity assay or Annexin V staining followed by flow cytometry.

Transcription Factor (MYC, p53)-Targeting Experiments

Q3: We are screening for MYC inhibitors, but its lack of a defined active site makes it challenging. What are the most promising indirect strategies?

Targeting MYC indirectly by disrupting its protein-protein interactions or stability is a primary strategy. The table below summarizes key approaches [1] [3].

| Strategy | Mechanism | Research Compounds / Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Disrupting MYC/MAX Dimerization | Prevents MYC from binding to DNA and activating transcription [1]. | - Omomyc (a dominant-negative peptide) - Small-molecule screens (e.g., 10058-F4, JKY-2-169). |

| Targeting MYC Stability | Promotes the degradation of the MYC protein itself [3]. | - PROTACs that recruit E3 ligases to MYC. |

| Targeting Co-Factors | Inhibits partners necessary for MYC's transcriptional activity, such as BRD4 [1]. | - BET inhibitors (e.g., JQ1). |

| AI-Driven Binder Design | Using generative AI to design novel proteins that bind and inhibit the intrinsically disordered regions of MYC [12] [13]. | - RFdiffusion and "logos" methods from Baker Lab. |

Experimental Protocol: Validating MYC/MAX Dimerization Inhibitors

- Co-Immunoprecipitation (Co-IP): Treat cells with the candidate inhibitor. Lyse cells and immunoprecipitate MYC using a specific antibody. Perform western blotting on the immunoprecipitate with an anti-MAX antibody. A successful inhibitor will reduce the amount of MAX co-precipitated with MYC.

- Luciferase Reporter Assay: Transfert cells with a plasmid containing a luciferase gene under the control of a MYC-responsive promoter. Treat with the inhibitor and measure luciferase activity. Inhibition of MYC transcriptional activity will result in reduced luminescence.

- qRT-PCR of MYC Target Genes: Measure mRNA expression levels of known MYC target genes (e.g., ODC1, CAD) via quantitative RT-PCR after inhibitor treatment.

Q4: How can we target mutant p53, given that it is often unstable and loses its tumor-suppressor function?

The majority of p53 mutations are missense mutations, leading to the expression of full-length but dysfunctional proteins. Strategies focus on restoring wild-type function or exploiting specific mutant vulnerabilities [1] [3].

- Reactivating Mutant p53: Compounds like PRIMA-1 (APR-246) covalently bind to mutant p53, refold it into a wild-type conformation, and restore its DNA-binding and transcriptional activity. This is a key candidate in clinical trials.

- Targeting p53 with PROTACs: Degraders can be designed to target and eliminate mutant p53 proteins, thereby removing their potential "gain-of-function" oncogenic activities [11].

- Combination with DNA-Damaging Agents: Since p53 is central to the DNA damage response, combining a p53 reactivator with chemotherapeutics like cisplatin can synergize to induce apoptosis.

Phosphatase-Targeting Experiments

Q5: We are trying to develop inhibitors for a Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase (PTP), but the active site is highly conserved and polar, leading to selectivity and bioavailability issues. What modern approaches can we use?

The challenges you describe are central to why phosphatases are considered "undruggable." The field is moving beyond active-site directed inhibitors [1].

- Allosteric Inhibition: Identify and target less conserved, often more hydrophobic, pockets outside the active site. This can induce conformational changes that inhibit enzymatic activity with greater selectivity.

- PROTAC-Mediated Degradation: As with KRAS and MYC, designing PROTACs for PTPs bypasses the need to inhibit the active site directly and instead removes the protein from the cell [11].

- Targeting Substrate Specificity: Some PTPs have unique, adjacent binding sites for their specific protein substrates. Developing molecules that block this protein-protein interaction (PPI) interface can achieve high selectivity.

Experimental Protocol: Fragment-Based Drug Discovery (FBDD) for an Allosteric PTP Inhibitor

- Library Screening: Screen a library of small molecular fragments (~150-300 Da) against the target PTP using Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) or X-ray crystallography to identify weak binders.

- Hit Validation and Mapping: Co-crystallize fragment "hits" with the PTP to determine their precise binding location. The goal is to find fragments that bind to a novel, allosteric pocket.

- Fragment Growing and Linking: Use structure-based drug design to chemically elaborate the initial fragment, adding functional groups that increase its affinity and selectivity. If two fragments bind nearby, they can be linked together to create a higher-affinity molecule.

- Cellular Activity Assessment: Test optimized compounds in cells using a phospho-specific western blot against the PTP's known substrate to confirm target engagement and functional inhibition.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Technology | Function / Application | Key Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Covalent KRAS Inhibitors | Irreversibly bind to mutant cysteine (G12C) and lock KRAS in its inactive (GDP-bound) state [8] [1]. | Sotorasib (AMG510), Adagrasib (MRTX849) |

| PROTAC Technology | Bifunctional degraders that recruit E3 ubiquitin ligase to target proteins, leading to their proteasomal degradation [3] [11]. | KRAS(G12C) PROTACs, p53-targeting PROTACs |

| AI-Designed Binders | Generative AI software to design novel proteins that bind to intrinsically disordered targets or flat PPI interfaces [12] [13]. | RFdiffusion, "logos" method (Baker Lab) |

| Computational Docking (CADD) | Predicts the 3D binding pose and affinity of small molecules to a protein target, enabling virtual screening [14]. | Molecular docking software (AutoDock, Schrödinger) |

| SHP2 Inhibitors | Target upstream nodes; inhibit SHP2 phosphatase to block RTK-mediated RAS activation and overcome resistance [8] [9]. | TNO155, RMC-4550 |

| BET Inhibitors | Indirect transcriptional modulation; inhibit BRD4 to disrupt its co-activation of oncogenes like MYC [1]. | JQ1, OTX015 |

Visualizing Key Concepts

KRAS Signaling and Therapeutic Intervention

PROTAC Mechanism for Undruggable Targets

The Role of Protein-Protein Interactions (PPIs) and Intrinsically Disordered Regions (IDRs)

FAQs: Overcoming Experimental Challenges in PPI and IDR Research

FAQ 1: What are the biggest challenges in developing small molecule modulators for PPIs, and what strategies can overcome them?

The primary challenge is the nature of PPI interfaces, which are often large, flat, and lack deep pockets for small molecules to bind, making them seem "undruggable" [15]. Several strategies have been developed to address this:

- Fragment-Based Drug Discovery (FBDD): This approach uses low molecular weight fragments that can bind to discontinuous hot spots on the PPI interface. These fragments can then be linked or optimized into larger, more potent lead molecules [15].

- Peptidomimetics: These are molecules designed to recapitulate the secondary structure (e.g., α-helices, sheets, loops) of key peptide segments involved in the PPI, thereby disrupting the interaction [15].

- High-Throughput Screening (HTS): Using chemically diverse libraries enriched with compounds likely to target PPIs can successfully identify lead modulators, though its effectiveness can be limited for some interfaces [15].

- Computational Tools: Virtual screening (both structure-based and ligand-based) and emerging machine learning models can significantly speed up the discovery and optimization of PPI modulators [15].

FAQ 2: My PPI assay yields weak or transient signals. Which live-cell techniques are best for capturing these dynamic interactions?

Weak, transient interactions are common in signaling pathways and can be studied using sensitive fluorescence techniques in living cells:

- FRET (Förster Resonance Energy Transfer): This is the most powerful and popular approach. FRET is exquisitely sensitive to nanometer-range proximity and orientation between fluorophores tagged to your proteins of interest. It can detect both specific complex formation and random collisions, and is amenable to quantitative analysis to determine interaction kinetics and efficiencies [16].

- Bimolecular Fluorescence Complementation (BiFC): This technique uses non-fluorescent fragments of a fluorescent protein attached to two interacting proteins. If the proteins interact, the fragments refold into a fluorescing product. It excels as an end-point assay for confirming interactions, especially transient ones, though the irreversible refolding means it is less suited for studying dynamics [16].

- Fluorescence Correlation Spectroscopy (FCM) / Fluorescence Cross-Correlation Spectroscopy (FCCM): These techniques analyze fluorescence fluctuations as molecules diffuse through a small volume. They can provide information on diffusion coefficients, stoichiometry, and affinities of complexes in solution or at the membrane, making them ideal for studying the dynamics of large protein complexes at low, physiological concentrations [16].

FAQ 3: IDRs are difficult to study structurally. What methods are available for characterizing their function?

The disordered nature of IDRs makes them resistant to classical structural biology, but a combination of methods can reveal their functions:

- Computational Prediction: Tools like IUPred and PONDR use amino acid sequence to predict disorder propensity and are efficient for proteome-wide screening [17].

- Biophysical Techniques:

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy: Ideal for characterizing structural and dynamic properties of IDRs at the amino acid level, even in a disordered state [17] [18].

- Cryo-Electron Microscopy (Cryo-EM): Can be used to visualize larger complexes where IDRs are involved, often alongside structured domains. NMR and Cryo-EM provide a synergistic approach [18].

- Circular Dichroism (CD): Provides information on secondary structure content and conformational changes [17].

- Functional Assays: Since IDRs are enriched with functional sites, assays detecting post-translational modifications (e.g., phosphorylation) or protein-protein interactions (e.g., via FRET or BiFC) are crucial for linking IDR structure to function [19] [17].

FAQ 4: Why are mutations in IDRs often linked to disease, and how can we identify functionally critical IDRs?

IDRs are enriched in disease-associated mutations because they often harbor critical functional elements like molecular recognition features (MoRFs) and post-translational modification (PTM) sites [17]. Mutations can disrupt conformational plasticity, impair binding capacity, or lead to pathogenic aggregation [17]. To identify critical IDRs:

- Leverage Genetic Data: Compare the frequency of mutations in general population databases (e.g., gnomAD) versus patient-based databases (e.g., ClinVar). IDRs that are significantly depleted in population variants but enriched in pathogenic mutations are likely functionally important and intolerant to mutation [19].

- Analyze Functional Annotations: Map known functional sites from databases like UniProt onto IDR sequences. Features commonly enriched in critical IDRs include "regions of interest," binding sites, and sites for PTMs [19].

Troubleshooting Guides for Key Experiments

Guide 1: Troubleshooting FRET Experiments to Study PPIs

Table: Troubleshooting FRET Experiments

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No FRET signal | Proteins are not interacting; fluorophores are too far apart; poor fluorophore choice (low spectral overlap) | Verify interaction with another technique (e.g., co-IP); check linker length between protein and fluorophore; use recommended FP pairs (e.g., mCerulean/mVenus) [16]. |

| High FRET signal in negative control | Direct interaction between fluorophores; spectral bleed-through (crosstalk) | Include controls with fluorophores alone; use acceptor photobleaching to confirm FRET; adjust detection filters to minimize crosstalk [16]. |

| Low signal-to-noise ratio | Low expression of fusion proteins; photobleaching | Optimize transfection to increase protein expression; use FPs with high quantum yield and low photobleaching (e.g., mCitrine, mCherry) [16]. |

| Altered protein function | FP tag disrupts native folding, localization, or interaction | Tag protein at the opposite terminus; use smaller tags (e.g., tetracysteine motifs with FlAsH/ReAsH); verify function and localization of tagged protein [16]. |

Workflow for a Quantitative FRET Experiment in Living Cells: The following diagram outlines the key steps for setting up and validating a FRET experiment to study PPIs in living cells.

Guide 2: Troubleshooting IDR Functional Analysis

Table: Troubleshooting IDR-Related Experiments

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| IDR expression leads to protein aggregation | High hydrophobicity in specific regions; lack of solubility tags | Use fusion solubility tags (e.g., GST, MBP) during purification; optimize expression conditions (lower temperature, shorter time) [17]. |

| Cannot obtain structural data on IDR | IDR is highly flexible and dynamic, resistant to crystallization | Use solution-based methods like NMR spectroscopy; employ Small-Angle X-ray Scattering (SAXS) to study ensemble conformations [17] [18]. |

| Difficulty identifying functional motifs within a long IDR | Functional motifs (e.g., MoRFs) are short and transient | Use phylogenetic conservation analysis to pinpoint constrained segments; perform peptide scanning or phage display to find binding regions; look for enrichment of PTM sites [19] [17]. |

| Unexpected order in crystal structure of an IDR | IDR underwent "coupled folding and binding" during crystallization | The function may rely on this induced folding. Validate the physiological relevance of the bound conformation using mutagenesis and functional assays in cells [20]. |

Workflow for Characterizing a Putative Cancer-Associated IDR: This workflow provides a logical pathway for moving from a genetic variant in an IDR to understanding its potential functional impact in cancer.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents and Tools for PPI and IDR Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent Proteins (FPs) [16] | Tagging proteins for live-cell imaging (FRET, BiFC). | Use monomeric FPs (e.g., mCerulean, mVenus) to prevent oligomerization artifacts. Consider spectral properties for multiplexing. |

| Tetracysteine Motif & Biarsenical Dyes (FlAsH/ReAsH) [16] | Small, genetic tags for fluorescent labeling, minimizing tag bulkiness. | Improved selectivity with optimized motifs; requires specific labeling conditions in living cells. |

| siRNAs / shRNAs [21] | Selective gene silencing to validate target function in disease models. | Critical for studying "undruggable" targets like KRAS and MYC; inverted RNAi designs enable co-silencing. |

| Computational Predictors (IUPred, PONDR) [17] | Predicting intrinsic disorder from amino acid sequence. | Fast, proteome-wide screening to prioritize experimental work on disordered regions. |

| Machine Learning Models [15] [22] | Predicting PPIs, identifying druggable pockets, and patient stratification from multimodal data. | Requires high-quality training data; used for forecasting disease trajectories and identifying novel therapeutic vulnerabilities. |

| Selective Autophagy Receptor LIR Motifs [23] | Tools to study or manipulate selective autophagy pathways. | LIR motifs (e.g., from p62) bind ATG8/LC3 proteins; useful as peptides or in constructs to probe autophagy. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying and Overcoming Common Experimental Challenges

FAQ 1: Why can't my small molecule inhibitor bind to the flat, shallow surface of my target protein?

Problem: Your target protein lacks deep, hydrophobic pockets, resulting in a flat and featureless interaction surface that prevents effective small molecule binding.

Explanation: Traditional small molecule drugs typically function by occupying well-defined, deep pockets on a protein's surface, much like a key fits into a lock. However, many cancer-related targets, including transcription factors, phosphatases, and small GTPases, possess relatively flat interaction interfaces with minimal topological features for small molecules to engage with effectively [1]. These proteins often perform their biological functions through large, continuous protein-protein interactions (PPIs) that span extensive surface areas without deep crevices [1].

Solution: Implement a multi-pronged computational and experimental strategy:

Table: Computational Approaches for Flat Surface Targeting

| Approach | Methodology | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Covalent Inhibition | Design compounds with mildly reactive functional groups that form covalent bonds with specific amino acid residues [1]. | KRASG12C inhibitors (sotorasib) target the previously "undruggable" KRAS by covalently binding to cysteine residues [1]. |

| Allosteric Inhibition | Identify and target alternative binding sites that indirectly modulate the protein's active site [1]. | Identify cryptic pockets through molecular dynamics simulations that appear only under specific conformational states [24]. |

| PROTAC Technology | Develop proteolysis-targeting chimeras that recruit cellular machinery to degrade the target protein [25]. | Design molecules that bind to target protein on one end and E3 ubiquitin ligase on the other, enabling targeted degradation [25]. |

Experimental Protocol:

- Run extended molecular dynamics (MD) simulations (≥1000 ns) to identify transient pockets [24].

- Perform fragment-based screening using X-ray crystallography or NMR to identify small fragments that bind to weak sites [1].

- Use covalent docking screens to identify potential cysteine-reactive compounds if applicable [1].

- Validate hits using surface plasmon resonance (SPR) to confirm binding, even if weak.

- Optimize confirmed hits using structure-based drug design, focusing on improving affinity.

FAQ 2: How do I address the high conservation of my target across protein families, which leads to off-target toxicity?

Problem: Your target protein shares significant structural similarity with other proteins in its family, resulting in poor selectivity and potential toxicity.

Explanation: High sequence and structural conservation across protein family members, particularly in active sites, makes selective inhibition extremely challenging. This is particularly problematic for phosphatases and small GTPases, where active sites are often structurally similar among family members [1]. When multiple proteins share nearly identical binding pockets, a drug designed for one target will likely bind to others, causing undesirable off-target effects.

Solution: Leverage computational tools to identify and exploit subtle structural differences:

Table: Strategies for Targeting Conserved Proteins

| Strategy | Mechanism | Tools/Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Context-Specific Targeting | Exploit cellular context and pathway-level effects beyond direct binding interactions [26]. | DeepTarget tool uses genetic and drug screening data across cell lines to identify context-specific vulnerabilities [26]. |

| Peripheral Site Targeting | Target areas adjacent to the active site that show greater structural variation [1]. | Molecular dynamics with Markov state models to identify allosteric networks [24]. |

| Mutation-Specific Targeting | Design compounds that specifically target mutant forms over wild-type proteins [26]. | DeepTarget can predict drugs with preferential effects on mutated vs. non-mutated target proteins [26] [27]. |

Experimental Protocol:

- Perform comparative structural analysis of your target against its closest homologs using PDB structures.

- Use molecular dynamics simulations to identify dynamic differences between family members.

- Screen compound libraries against multiple family members in parallel using computational docking.

- Apply machine learning models like DeepTarget to predict mutation-specific effects [26].

- Validate selectivity in cellular models expressing different family members.

FAQ 3: My small molecules show promising biochemical activity but fail in cellular assays. What could be happening?

Problem: Compounds that demonstrate excellent binding in purified biochemical assays show no efficacy in cellular or tissue contexts.

Explanation: This discrepancy often occurs because the cellular environment introduces additional complexities not present in simplified biochemical systems. Your target may function differently in various cellular contexts, or the compound may fail to reach the target due to permeability issues, off-target binding, or context-specific protein interactions [26]. The same protein can have different functions and interaction partners in different cell types, dramatically affecting drug response.

Solution: Implement context-aware screening and validation:

Experimental Protocol:

- Employ context-specific computational tools like DeepTarget that integrate large-scale genetic and drug screening data across hundreds of cell lines [26].

- Perform pathway-level analysis to understand how inhibition affects broader cellular networks rather than isolated targets.

- Use multi-omics integration (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics) to identify biomarkers of response.

- Validate predictions in multiple cell line models with different genetic backgrounds.

- Test compound activity in 3D culture systems or organoids that better mimic tissue context.

Case Study Example: Ibrutinib, an FDA-approved drug for blood cancers, was found to be effective in some solid tumors despite the absence of its primary target (BTK) in those tissues. DeepTarget analysis revealed that in solid tumors with EGFR mutations, Ibrutinib effectively kills cancer cells by acting on EGFR as a secondary target, demonstrating how cellular context dramatically alters drug mechanism [26] [27].

Key Experimental Workflows and Signaling Pathways

Computational Drug Discovery Workflow for Undruggable Targets

Targeting KRAS Signaling Pathway: From Undruggable to Druggable

Research Reagent Solutions for Targeting Undruggable Proteins

Table: Essential Computational Tools and Resources

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application in Undruggable Targets |

|---|---|---|

| DeepTarget | Predicts primary and secondary targets using genetic and drug screening data [26] | Identifies context-specific targets and repurposing opportunities [26] [27] |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) | Simulates protein dynamics and conformational changes [24] [28] | Identifies transient pockets and allosteric sites [24] |

| BioGPS | Detects ligandable protein pockets on 3D structures [25] | Maps druggable sites on protein-protein interaction networks [25] |

| ProtBERT/ESM | Protein language models for sequence analysis [29] | Predicts conserved vs. variable regions across protein families |

| DrugAppy | End-to-end deep learning framework for drug discovery [5] | Designs novel inhibitors through AI-driven workflow [5] |

| QM/MM Methods | Hybrid quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics simulations [28] | Studies enzyme catalysis and reaction mechanisms for covalent drugs [1] |

| PDB | Protein Data Bank - repository of 3D structures [29] [25] | Source of structural information for comparative analysis |

| DepMap | Dependency Map consortium data [26] | Provides cancer vulnerability data for context-specific targeting [26] |

Advanced Computational Methodologies

Multi-Target Drug Discovery Using Machine Learning

Rationale: Complex diseases like cancer involve dysregulation of multiple molecular pathways, making single-target approaches often insufficient [29]. Machine learning (ML) enables the systematic discovery of compounds that modulate multiple targets simultaneously, addressing disease complexity more effectively.

Implementation Protocol:

- Data Collection: Gather drug-target interaction data from databases like ChEMBL, BindingDB, and DrugBank [29].

- Feature Representation: Encode molecules using molecular fingerprints, graph representations, or SMILES strings; represent proteins using sequence or structure-based descriptors [29].

- Model Training: Implement multi-task learning architectures that predict activity against multiple targets simultaneously.

- Validation: Test predicted multi-target profiles in diverse cellular contexts to confirm polypharmacology.

- Optimization: Use reinforcement learning to refine compounds for desired multi-target profiles while maintaining drug-like properties.

Key ML Techniques:

- Graph Neural Networks (GNNs): Model molecules as graphs to capture structural topology [29].

- Transformer Models: Process biological sequences and capture long-range dependencies [29].

- Multi-task Learning: Simultaneously predict activities against multiple targets, leveraging shared representations [29].

- Attention Mechanisms: Identify important molecular substructures and protein regions contributing to binding [29].

The Computational Toolkit: AI, Quantum Computing, and Generative Design in Action

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: AI Model Generizes Chemically Invalid or Unstable Structures

- Problem: The generative chemistry platform produces molecules with incorrect valences, unstable rings, or reactive functional groups.

- Solution:

- Apply Medicinal Chemistry Filters (MCFs): Implement filters to automatically exclude Pan-Assay Interference Compounds (PAINS) and other undesirable structural motifs [30].

- Validate Synthetic Accessibility: Use tools like the Retrosynthesis Related Synthetic Accessibility (ReRSA) score, which assesses feasibility based on commercially available building blocks, to prioritize molecules that are practical to synthesize [30].

- Review Training Data: Ensure the generative model was trained on a high-quality, curated chemical library to reduce the learning of invalid patterns.

Issue 2: Generated Molecules Have Poor Predicted ADMET Properties

- Problem: Candidates from the AI show unfavorable pharmacokinetic or toxicity profiles in silico, hindering progression.

- Solution:

- Integrate Multi-Parameter Optimization: Use platforms that allow you to set constraints for absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) properties during the generative process, not just afterward [31] [30].

- Fine-Tune on Proprietary Data: Retrain the platform's AI predictors using your in-house experimental data to improve the accuracy of property predictions for your specific chemical series [30].

- Leverage Hybrid Physics-AI Models: Combine AI with physics-based simulations for more accurate binding affinity and free energy predictions [30].

Issue 3: Difficulty Prioritizing AI-Generated Targets for "Undruggable" Oncology Targets

- Problem: The biological AI platform identifies numerous potential targets, but it is challenging to rank them for targets with no known active sites or binders.

- Solution:

- Utilize Composite LLM Scores: Employ large language model (LLM)-based scores that evaluate targets based on confidence, commercial tractability, druggability, and mechanism clarity to aid decision-making [30] [32].

- Analyze Multi-Omics Data: Use the platform's integrated transcriptomics, proteomics, and epigenetics data to triangulate evidence for a target's role in cancer progression [30] [33].

- Inspect AI Transparency Maps: Use heat-maps that show which data layers (e.g., specific omics datasets, literature) contributed most to a target's high ranking to build scientific trust and validate the hypothesis [30].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the key differences between the AI approaches of Exscientia and Insilico Medicine? A1: While both use generative AI, their core strategies differ. Exscientia pioneered a "Centaur Chemist" model, deeply integrating automated generative chemistry with high-content phenotypic screening on patient-derived samples [31]. Following its 2024 merger with Recursion, its approach has further integrated with massive phenomic screening data [31]. Insilico Medicine operates an end-to-end platform with highly specialized, interconnected modules: PandaOmics for target discovery, Chemistry42 for small-molecule design, and Generative Biologics for designing peptides and antibodies [30] [32].

Q2: How can I assess the novelty of an AI-generated molecule to avoid IP conflicts? A2: Platforms incorporate specific metrics for this. For example, Insilico's Chemistry42 uses the Medicinal Chemistry Evolution (MCE-18) score, which assesses molecular novelty based on sp³ complexity and other parameters [30]. Furthermore, a core strength of generative AI is scaffold hopping—creating novel molecular frameworks that are not covered by existing patents while maintaining activity against the target [34].

Q3: Our experimental validation shows that an AI-prioritized target does not modulate the disease phenotype. What could have gone wrong? A3: This can stem from several issues in the AI workflow:

- Data Bias: The AI model may have been trained on biased or non-representative omics data, leading to spurious target-disease associations [35] [36].

- Lack of Causal Evidence: The AI may have identified a target that is merely correlated with the disease state rather than being a causal driver. It is crucial to use platforms that integrate genetic evidence (e.g., from genome-wide association studies) to support causality [33].

- Insufficient Context: The target's role may be highly context-dependent (e.g., specific cancer subtype, tumor microenvironment). Validate that your experimental models accurately reflect this biological context.

Performance Data and Case Studies

The table below summarizes key performance metrics and case studies from leading companies in AI-driven drug discovery.

| Company / Platform | AI Approach & Key Features | Reported Efficiency Gains | Key Oncology/Other Case Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exscientia [31] | - "Centaur Chemist" generative chemistry- Integrated target-to-design pipeline- Patient-derived biology & phenomics | - Design cycles ~70% faster- 10x fewer compounds synthesized than industry norms | - CDK7 inhibitor (GTAEXS-617): In Phase I/II trials for solid tumors [31]. |

| Insilico Medicine [31] [30] | - End-to-end generative AI (PandaOmics, Chemistry42)- Hybrid AI + physics-based methods- Multi-parameter optimization | - ISM001-055: Target to Phase I trials in 18 months for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis [31] [30].- Platform can generate >2,400 candidates in dozens of hours [30]. | - QPCTL inhibitors: Identified for tumor immune evasion [33]. |

| Schrödinger [31] | - Physics-enabled (computational) + ML design | - N/A | - Zasocitinib (TAK-279): A TYK2 inhibitor originating from its platform advanced to Phase III trials [31]. |

Experimental Protocols for De Novo Design

Protocol 1: AI-Driven Hit Identification for a Novel Oncology Target

Target Identification & Validation:

- Tool: PandaOmics or similar target discovery platform.

- Method: Input multi-omics data (e.g., from TCGA) and use the AI to rank potential targets based on novelty, confidence, druggability, and linkage to the cancer pathway. Use integrated knowledge graphs and literature mining to build biological rationale [30] [33].

De Novo Molecular Generation:

- Tool: Chemistry42, Exscientia's Centaur Chemist, or similar generative chemistry platform.

- Method: Define the Target Product Profile (TPP), including binding affinity, selectivity, and key ADMET properties. Use an ensemble of generative models (VAEs, GANs, Transformers) to create novel molecular structures satisfying these constraints [30] [34].

In Silico Prioritization:

- Method:

- Apply >460 Medicinal Chemistry Filters to remove undesirable compounds [30].

- Score molecules using AI-based affinity predictors and physics-based methods like molecular dynamics (MD) simulations for binding stability (using tools like MDFlow) [30] [32].

- Predict synthetic routes via AI-powered retrosynthesis analysis [30].

- Method:

Experimental Validation:

- Method: Synthesize the top 10-50 prioritized compounds and test them in biochemical and cell-based assays to confirm activity and selectivity against the oncology target.

Protocol 2: Designing a Therapeutic Peptide for an "Undruggable" Protein-Protein Interface

Scaffold Generation:

- Tool: Generative Biologics or similar platform.

- Method: Input target protein structure or sequence. Use diffusion models and graph neural networks (GNNs) to generate thousands of novel peptide sequences predicted to bind the target site [30].

Affinity and Developability Optimization:

- Method: Use AI predictors to score generated peptides for affinity, solubility, and liability. Retrain models on internal data if available. In an internal case, this process generated over 5,000 novel peptides for GLP1R in 72 hours, with 14 out of 20 tested showing biological activity [30].

Experimental Validation:

- Method: Synthesize top candidates and test using surface plasmon resonance (SPR) for binding affinity and cell-based assays for functional activity.

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key computational and experimental resources used in AI-driven de novo molecular design.

| Reagent / Tool | Type | Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| PandaOmics [30] [32] | Software Platform | AI-powered biology platform for target and biomarker discovery; integrates multi-omics data and literature mining. |

| Chemistry42 [30] [32] | Software Platform | A comprehensive AI suite for de novo small molecule design, optimization, and property prediction. |

| Generative Biologics [30] [32] | Software Platform | AI engine for designing and optimizing novel biologics, including peptides and antibodies. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation (e.g., MDFlow) [30] [32] | Software Tool | Provides physics-based simulation of protein-ligand interactions to assess binding stability and mechanism. |

| AlphaFold [35] | Software Tool | Predicts 3D protein structures from amino acid sequences, providing critical structural data for targets with unknown structures. |

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

AI-Driven Discovery Workflow

Computational Targeting Strategy

FAQs: Understanding IDPs and AI-Designed Binders

What are Intrinsically Disordered Proteins (IDPs) and why are they important therapeutic targets? Intrinsically Disordered Proteins (IDPs) and regions (IDRs) are proteins that do not fold into a stable, consistent 3D shape but remain highly flexible. They make up nearly half of the human proteome and drive key cellular signaling, stress responses, and disease progression, particularly in cancer and neurodegenerative diseases. Their inherent flexibility has made them historically very challenging to target with conventional drugs, which typically require a well-defined binding pocket [12] [13].

How do AI-designed binders overcome the challenge of targeting disordered regions? Generative AI methods, such as RFdiffusion and the 'logos' strategy, can now design proteins that bind these highly flexible targets with atomic precision. Instead of requiring a pre-existing structure, these AI tools can create binders that either wrap around targets with some secondary structure or assemble from pre-made parts to bind sequences lacking any regular structure, achieving high affinity and specificity that wasn't possible before [12] [13] [37].

What proof-of-concept results validate this approach? Initial designed binders have shown promising functional results in cell-based tests, including:

- Blocking pain signaling by targeting the opioid peptide dynorphin [12] [13].

- Dismantling toxic amyloid fibrils linked to type 2 diabetes [12] [13].

- Disabling pathogenic prion seeds [12].

Are these designed binders specific to their intended targets? Yes. The AI design processes, particularly the 'logos' method, have been validated through all-by-all binding tests, confirming that the binders exhibit high selectivity for their intended targets and do not cross-react with non-targets [37].

What is the main difference between the 'logos' and 'RFdiffusion' design strategies? These are complementary strategies. The RFdiffusion-based method excels at designing binders to targets that possess some helical and strand secondary structure. The 'logos' method, which assembles binders from a library of ~1,000 pre-made parts, works best for targets completely lacking regular secondary structure [12] [13].

Troubleshooting Guide: Experimental Issues and Solutions

| Problem Area | Specific Issue | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Binder Affinity | Low binding affinity in assays | Poor complementarity with dynamic target; binder rigidity. | Re-optimize using a different AI approach (e.g., switch from logos to RFdiffusion if target has some structure). Use longer molecular dynamics simulations to assess flexibility. |

| Binder Expression & Solubility | Low yield or aggregation in expression | Hydrophobic surface exposure; unstable fold. | Incorporate surface point mutations to improve solubility; fuse with solubility-enhancing tags (e.g., SUMO, GST) during initial testing. |

| Target Specificity | Off-target binding in cellular models | Binder recognizes a common, short peptide motif present in multiple proteins. | Analyze the binder's target sequence for homology to other human peptides; re-design using the AI pipeline with explicit negative design against these off-target sequences. |

| Functional Efficacy | Binder binds target but no phenotypic effect in cells | Binding site is not critical for the target's pathological function. | Re-prioritize the target region; design binders against different functional epitopes (e.g., regions known for critical protein-protein interactions). |

| Validation | Discrepancy between computational prediction and experimental binding | AI model inaccuracy; force field limitations. | Use AlphaFold3 or RoseTTAFold to independently predict the binder-target complex structure as a validation step before experimental testing [38]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol 1: De Novo Binder Design Using the 'Logos' Pipeline

This protocol is designed for creating binders to targets that lack any regular secondary structure [12] [37].

Materials:

- Software: Custom 'logos' pipeline software (publicly available).

- Input: Amino acid sequence of the disordered target region.

- Library: Pre-computed library of ~1,000 protein parts or pockets.

Method:

- Target Analysis: Input the target peptide sequence. The algorithm scans for short, recognizable motifs.

- Pocket Selection: The pipeline selects complementary pre-made protein pockets from its library that are predicted to fit the target motifs.

- Binder Assembly: The selected pockets are assembled into a single, continuous protein scaffold. This step involves computational optimization to ensure stable folding of the binder itself.

- Affinity Optimization: The assembled binder is refined to maximize predicted binding energy with the flexible target.

- In Silico Validation: The final designed binder sequence is evaluated with protein structure prediction tools like AlphaFold to verify the intended binding mode.

Protocol 2: Binder Design and Validation Using RFdiffusion

This protocol is suitable for targets that have some propensity for helical or strand secondary structure [12] [38].

Materials:

- Software: RFdiffusion tool.

- Input: Structure of the target (if a transient structure exists) or its sequence.

- Hardware: High-performance computing cluster with GPUs.

Method:

- Target Specification: Define the target protein and the general region for binding.

- Generative Design: Run the RFdiffusion network, which uses a diffusion model to generate entirely new protein structures that "wrap around" the specified target region.

- Sequence Design: Using a tool like ProteinMPNN, generate an amino acid sequence that will fold into the designed protein structure from step 2.

- Validation Round 1 (Computational): Predict the structure of the designed binder complexed with the target using AlphaFold2 or RoseTTAFold. Analyze the predicted interface and binding energy.

- Validation Round 2 (Experimental):

- Expression: Clone the DNA sequence of the validated design into an expression vector (e.g., pET series) and express in E. coli.

- Purification: Purify the binder protein using affinity and size-exclusion chromatography (SEC).

- Binding Assay: Measure affinity using Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) or Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC). Expect high-affinity binders in the nanomolar to picomolar range [12] [37].

- Specificity Test: Validate specificity using techniques like yeast display or BLI against a panel of related protein targets.

Protocol 3: Functional Cellular Assay for a Pain-Signaling Blocker

This protocol is based on the successful blockade of dynorphin signaling [12].

Materials:

- Cell line expressing the target GPCR (e.g., opioid receptor).

- Designed binder specific to the disordered peptide ligand (e.g., dynorphin).

- Assay kits for measuring intracellular calcium or cAMP.

Method:

- Pre-incubation: Pre-treat cells with the purified designed binder for a set time (e.g., 30-60 minutes).

- Stimulation: Activate the signaling pathway by adding the native disordered peptide ligand (dynorphin).

- Signal Measurement: Quantify the downstream signaling output (e.g., calcium release or cAMP inhibition).

- Analysis: Compare the signaling output in binder-treated cells versus untreated controls. A successful binder will significantly reduce the signaling response upon ligand addition.

Key Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and computational tools essential for research in this field.

| Tool / Reagent | Type | Function in Research | Example / Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| RFdiffusion | Software | Generative AI model for de novo protein design that creates binders by wrapping around target structures. | Baker Lab / Publicly Available [12] [38] |

| Logos Pipeline | Software | Computational method for designing binders by assembling pre-made protein parts to target disordered sequences. | Baker Lab / Publicly Available [12] [37] |

| AlphaFold2/3 | Software | Protein structure prediction tool used for independent validation of designed binder-target complexes. | DeepMind / Publicly Available [38] |

| ProteinMPNN | Software | Neural network that designs amino acid sequences for a given protein backbone structure. | Baker Lab / Publicly Available [38] |

| pET Expression Vector | Molecular Biology Reagent | Standard plasmid for high-level expression of designed binder proteins in E. coli. | Commercial Vendors |

| SPR / BLI Instruments | Analytical Instrument | Measures real-time binding kinetics (affinity, on/off rates) between the designed binder and its target. | Commercial Vendors (e.g., Cytiva, Sartorius) |

The Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (KRAS) is one of the most frequently mutated oncogenes in human cancers, found in approximately 25% of all tumors, including pancreatic, colorectal, and non-small cell lung carcinomas [39] [40]. For decades, KRAS was considered "undruggable" due to its smooth surface structure with no deep hydrophobic pockets for small molecules to bind effectively, and its picomolar affinity for GTP which makes developing competitive inhibitors exceptionally challenging [39] [40]. The emergence of quantum-classical hybrid models represents a transformative approach to overcome these historical challenges by leveraging the unique capabilities of quantum computing to navigate the vast chemical space of potential drug candidates.

Quantum-classical hybrid models integrate parameterized quantum circuits with classical deep learning architectures, creating systems that can theoretically leverage quantum effects such as superposition and entanglement to explore molecular distributions more efficiently than purely classical systems [41] [42]. For challenging targets like KRAS, these models offer a promising path to identify novel inhibitor scaffolds that might evade classical discovery approaches. Recent experimental validations have demonstrated that quantum-classical generative models can produce biologically active KRAS inhibitors, marking a significant milestone in computational drug discovery [41] [43] [44].

Technical Foundations: How Quantum-Classical Hybrid Models Work

Core Architectural Components

Hybrid quantum-classical models for drug discovery typically combine several computational components into an integrated workflow:

Quantum Circuit Born Machines (QCBMs): Quantum generative models that employ parameterized quantum circuits to learn complex probability distributions of molecular structures. These circuits leverage quantum superposition to explore multiple molecular configurations simultaneously [41] [43].

Classical Deep Learning Networks: Typically Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks or Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) that handle sequential data processing and molecular graph representations [41] [43].

Reward Networks: Classical networks that predict desirable chemical properties and provide feedback signals to guide the generative process toward drug-like molecules [42].

The quantum component typically serves as a prior distribution generator, while classical networks refine these suggestions and ensure chemical validity. This division of labor allows the model to leverage quantum advantages while working within the constraints of current noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) hardware [42].

KRAS Biological Context

To effectively target KRAS, researchers must understand its biological behavior. KRAS functions as a molecular switch, cycling between active GTP-bound and inactive GDP-bound states [39]. Oncogenic mutations (most commonly at codons 12, 13, and 61) lock KRAS in its active conformation, leading to continuous signaling through pathways like RAF-MEK-ERK and PI3K-AKT-mTOR that drive cell proliferation and survival [39] [40]. The switch I and switch II regions of KRAS undergo conformational changes during activation and represent key areas for therapeutic intervention [39].

KRAS Signaling Pathway: This diagram illustrates the core KRAS signaling cascade that becomes constitutively active in cancer cells due to mutations, driving uncontrolled proliferation and survival.

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

End-to-End Hybrid Workflow for KRAS Inhibitor Discovery

The following workflow represents an integrated quantum-classical approach that has successfully generated experimentally validated KRAS inhibitors [41] [43]:

Hybrid Model Workflow: Integrated quantum-classical pipeline for KRAS inhibitor discovery, from data preparation to experimental validation.

Step-by-Step Protocol: Implementing a Quantum-Classical Hybrid Model

Phase 1: Training Data Preparation

- Curate Known Actives: Compile approximately 650 experimentally confirmed KRAS inhibitors from literature sources [41] [43].

- Virtual Screening Enhancement: Use VirtualFlow 2.0 to screen 100 million molecules from Enamine's REAL library, selecting the top 250,000 compounds with best docking scores [41] [43].

- Chemical Space Exploration: Apply the STONED-SELFIES algorithm to known inhibitors to generate 850,000 structurally similar compounds with maintained synthesizability [43].

- Dataset Assembly: Combine all sources into a unified training dataset of approximately 1.1 million molecules [41].

Phase 2: Model Training & Configuration

- Quantum Component Setup: Implement a Quantum Circuit Born Machine (QCBM) using a 16-qubit quantum processor. Critical parameters include:

Classical Component Configuration: Implement an LSTM network with:

Hybrid Integration: Connect QCBM and LSTM such that the quantum component generates prior distributions in each training epoch, which are then refined by the classical network [41].

Phase 3: Molecule Generation & Validation

- Generative Process: Sample 1 million candidate molecules from the trained model [41].

- Multi-Stage Filtering:

- Experimental Validation:

- Synthesize top 15-20 candidates

- Evaluate binding via surface plasmon resonance (SPR)

- Assess functional activity in cell-based assays (e.g., MaMTH-DS) [41]

Success Metrics and Validation

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics for Hybrid Quantum-Classical Models

| Metric | Target Value | Measurement Method |

|---|---|---|

| Success Rate | >21.5% improvement vs classical | Proportion of generated molecules passing filters [41] |

| Fréchet Distance | <12.5 | Distribution similarity to real molecules [42] |

| QED Score | >0.6 | Quantitative Estimate of Drug-likeness [42] |

| Synthetic Accessibility | >0.7 | Synthetic accessibility score [42] |

| Binding Affinity | <10 μM | Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) [41] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Quantum-Classical KRAS Drug Discovery

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Example Sources/Formats |

|---|---|---|

| Known KRAS Inhibitors | Training data foundation | ~650 compounds from literature [41] |

| Enamine REAL Library | Virtual screening source | 100+ million synthesizable compounds [41] [43] |

| STONED-SELFIES Algorithm | Chemical space expansion | Python implementation for molecular mutation [43] |

| Chemistry42 Platform | Structure-based validation | Commercial software for drug design [41] [43] |

| VirtualFlow 2.0 | Large-scale virtual screening | Open-source docking pipeline [41] |

| QCBM Framework | Quantum prior generation | 16-qubit IBM quantum processor [41] [43] |

| LSTM Network | Classical sequence refinement | TensorFlow/PyTorch implementation [41] |

| MaMTH-DS Assay | Functional validation | Cell-based KRAS signaling assay [41] |

| SPR Platform | Binding affinity measurement | Biacore or similar instruments [41] |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Common Implementation Challenges & Solutions

Problem: Low Success Rate in Molecule Generation Symptoms: Generated molecules fail synthesizability filters or show poor drug-likeness scores. Solutions:

- Increase training dataset diversity using STONED-SELFIES augmentation [41] [43]

- Adjust reward function weights in hybrid model to prioritize synthesizability and QED [42]

- Verify quantum circuit depth (4-8 layers optimal) and qubit count (higher generally better) [42]

Problem: Poor Energy Conservation in Dynamics Simulations Symptoms: Numerical instability in molecular dynamics trajectories. Solutions:

- Implement smaller time steps (0.5-2.0 fs) for QM/MM regions [45]

- Apply particle mesh Ewald (PME) treatment for long-range electrostatics [45]

- Verify Link Atom implementation for QM-MM boundary regions [45]

Problem: Model Training Instability Symptoms: Oscillating loss values or failure to converge. Solutions:

- Implement gradient clipping with norm value of 1.0 [42]

- Use warm-up/constant/decay learning rate scheduler [42]

- Adjust balance parameter (λ) between adversarial and reward losses [42]

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: What quantum hardware specifications are needed for effective KRAS inhibitor discovery? A: Current successful implementations use 16-qubit processors, with performance scaling approximately linearly with qubit count. Circuit depths of 4-8 layers with ring entanglement topologies have proven effective [41] [42].

Q: How does hybrid quantum-classical performance compare to purely classical approaches? A: In benchmark studies, the QCBM-LSTM hybrid demonstrated a 21.5% improvement in success rate for generating synthesizable, drug-like molecules compared to vanilla LSTM alone [41].

Q: What experimental validation is essential for computationally discovered KRAS inhibitors? A: A two-stage validation process is recommended: (1) Binding confirmation via surface plasmon resonance (SPR) to measure direct target engagement, and (2) Functional assessment in cell-based assays like MaMTH-DS to verify inhibition of KRAS signaling pathways [41].

Q: How critical is training data quality and quantity for success? A: Extremely critical. The successfully demonstrated workflow utilized ~1.1 million data points combining known actives, virtual screening hits, and algorithmically augmented compounds. For targets with less available data, transfer learning or data augmentation strategies are essential [41] [44].

Q: What are the most common architectural mistakes in hybrid model implementation? A: Key pitfalls include: (1) Insufficient quantum circuit depth (<4 layers), (2) Poorly designed quantum-classical interface, and (3) Inadequate reward function design. Optimal architectures typically layer multiple (3-4) shallow quantum circuits sequentially [42].

The integration of quantum-classical hybrid models into KRAS drug discovery represents a paradigm shift in targeting previously "undruggable" oncoproteins. The experimental validation of two novel KRAS inhibitors (ISM061-018-2 and ISM061-022) generated by a QCBM-LSTM hybrid model demonstrates the practical potential of this approach [41] [44]. ISM061-018-2 functions as a broad-spectrum KRAS inhibitor with binding affinity of 1.4 μM to KRAS-G12D, while ISM061-022 shows mutant-selective activity, particularly against KRAS-G12R and KRAS-Q61H [41].

As quantum hardware continues to evolve, with increasing qubit counts and improved error correction, the advantages of quantum-classical hybrid models are expected to become more pronounced. Future developments will likely focus on more sophisticated integration of structural information during the generation process, improved reward functions that better capture molecular interactions with dynamic protein targets, and expansion to other challenging therapeutic targets beyond KRAS. For researchers implementing these methods, careful attention to dataset quality, model architecture optimization, and robust experimental validation will remain critical success factors.

Allosteric Inhibition and Covalent Drug Design Computationally Guided

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the key advantages of combining allosteric and covalent inhibition strategies?

Combining allostery with covalent inhibition creates Covalent-Allosteric Inhibitors (CAIs), which aim to harness the benefits of both strategies. Allosteric inhibitors bind to sites distinct from the active (orthosteric) site, often leading to higher selectivity because allosteric sites are less conserved across protein families compared to orthosteric sites [46] [47]. Covalent inhibitors form a permanent bond with their target, typically through a reactive "warhead," leading to prolonged duration of action and increased potency [46] [1]. CAIs therefore can achieve long-lasting effects, reduced potential for drug resistance, enhanced specificity, and potentially lower toxicity [46] [3].

FAQ 2: Which kinetic parameters are critical for characterizing covalent-allosteric inhibitors, and why is a fast reaction not always better?

The potency of covalent inhibitors is best described by the second-order rate constant ( k{inact}/KI ), which characterizes the efficiency of the covalent inhibition in a time-independent manner [46]. The parameter ( KI ) (the inactivation constant) is derived from ( (k{off} + k{inact}) / k{on} ) and differs from the simple dissociation constant ( K_i ) used for reversible inhibitors [46].

While a faster inactivation efficiency rate generally correlates with greater cellular potency, recent research indicates this relationship plateaus. Beyond a certain point, a faster rate does not lead to increased potency, and relying solely on this metric can fail to distinguish the best drug candidates. Prioritizing compounds requires a balance between inactivation speed and other parameters, especially target selectivity, which measures how well a drug binds to its intended target over off-target proteins [48].

FAQ 3: What are the major computational challenges in discovering allosteric sites for drug design?

Identifying and validating allosteric sites presents several unique challenges:

- Transient and Cryptic Pockets: Many allosteric sites are not visible in static protein structures from X-ray crystallography or cryo-EM. They often exist only in specific, less populated conformational states of the protein [46] [47].

- Conformational Flexibility: Proteins are dynamic, and allosteric regulation is inherently linked to this flexibility. Capturing the full range of motions to find these sites is computationally expensive [47] [49].

- Low Evolutionary Conservation: While beneficial for selectivity, the low conservation of allosteric sites makes it difficult to use homology-based prediction methods that work well for orthosteric sites [47].

- Lack of General Rules: The structure-activity relationships and the principles of how ligand binding at an allosteric site impacts protein function are less understood than for orthosteric sites [46].

FAQ 4: Can you provide examples of successfully targeted "undruggable" proteins using these strategies?

Yes, several targets once considered "undruggable" have been successfully targeted.

- KRAS G12C: The KRAS oncogene was undruggable for decades due to its smooth surface and picomolar affinity for GTP/GDP. The discovery of a cryptic allosteric pocket adjacent to the mutated cysteine 12 (G12C) enabled the development of covalent inhibitors like Sotorasib (AMG510) and Adagrasib (MRTX849). These drugs bind covalently to the mutant cysteine and trap KRAS in its inactive state [1] [3].

- PTP1B: Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase 1B, a target for diabetes and obesity, has a highly conserved active site, making selective inhibition difficult. The discovery of an allosteric site near Cys121 allowed for the design of covalent-allosteric inhibitors like ABDF, which modulates activity by restricting the movement of the WPD loop [46].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: My virtual screening of a large compound library fails to identify hits for a known allosteric site.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: The protein structure used for docking is in a conformational state where the allosteric pocket is closed or absent.

- Solution: Use molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to sample conformational ensembles and identify structures where the pocket is open. Advanced sampling algorithms can reveal these transient states [47]. Alternatively, use a known allosteric ligand (if available) in a co-crystal structure as your receptor model.

- Cause: Standard docking programs may not be optimized for the specific geometry or flexibility of allosteric pockets.

- Solution: Employ more flexible docking protocols or use specialized tools designed for cryptic site detection. For covalent docking, use benchmarks like CovDocker that account for the formation of covalent bonds and associated structural changes [50].

- Cause: The chemical library may not contain fragments or compounds suitable for binding to the unique chemophysical environment of the allosteric site.

Problem 2: My covalent-allosteric inhibitor candidate shows high potency but also high toxicity in cellular assays.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: The warhead is too reactive, leading to off-target binding and modification of proteins with similar nucleophilic residues (e.g., other cysteines).

- Solution: Tune the warhead's reactivity. A less reactive warhead can improve selectivity by allowing for more specific recognition by the target protein before covalent bond formation occurs [52]. Use kinetic analyses to find an optimal balance between efficiency and selectivity [48].

- Solution: Perform proteome-wide profiling to identify off-targets. Techniques like activity-based protein profiling (ABPP) can directly quantify the selectivity of your covalent inhibitor across the proteome [46] [52].

- Cause: The non-covalent "scaffold" part of the molecule has inherent off-target activity.

- Solution: Re-optimize the scaffold for selectivity using structure-based design. Ensure that it has minimal affinity for unrelated proteins, as the covalent warhead will amplify any binding, however weak [48].

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Standard activity assays cannot distinguish between orthosteric and allosteric inhibition.

- Cause: Difficulty in obtaining a co-crystal structure of the inhibitor bound to the protein.

- Solution: Use orthogonal biophysical methods. Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange Mass Spectrometry (HDX-MS) can detect changes in protein dynamics and solvent accessibility upon inhibitor binding, helping to map the binding site [49]. Covalent binding can be confirmed through mass spectrometry to detect the expected mass shift [46].

- Cause: For covalent inhibitors, it is unclear which specific residue is modified.

- Solution: Use tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) after tryptic digestion of the protein-inhibitor complex to pinpoint the exact site of covalent modification [46].

Essential Data and Protocols

Key Kinetic Parameters for Covalent Inhibitor Characterization

The following parameters are crucial for the proper evaluation and comparison of covalent inhibitors [46] [52].

| Parameter | Description | Significance in Drug Discovery |

|---|---|---|

| ( k{inact}/KI ) | Second-order rate constant for covalent inactivation | Gold-standard measure of covalent inhibitor potency; time-independent [46]. |

| ( k_{inact} ) | First-order rate constant for the covalent modification step | Describes the maximum rate of covalent bond formation [46]. |

| ( K_I ) | Inactivation constant | Apparent concentration for half-maximal rate of inactivation; incorporates ( k{on} ), ( k{off} ), and ( k_{inact} ) [46]. |

| Residence Time | Duration for which the inhibitor remains bound to the target | Governs duration of pharmacological effect; prolonged for covalent inhibitors [52]. |

| Target Selectivity | Measure of binding to intended vs. unintended targets | Critical for differentiating promising candidates once potency plateaus; reduces toxicity [48]. |

Computational Tools for Allosteric and Covalent Drug Discovery

A summary of computational methods streamlining the discovery of allosteric and covalent drugs.

| Method Category | Key Function | Example Tools/Approaches |

|---|---|---|

| Machine Learning (ML) | Identifies potential allosteric sites from protein sequence and structure data [47]. | ML models trained on evolutionary, structural, and dynamic features; AlphaFold2 for structure prediction [47] [53]. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) | Reveals transient allosteric pockets and communication pathways via atomic-level simulation [47] [49]. | Enhanced sampling algorithms; GPCRmd database for specialized simulations [47]. |

| Network Analysis | Maps allosteric communication pathways to pinpoint critical regulatory residues [47]. | Methods based on residue-residue co-evolution and correlation [47]. |

| Covalent Docking | Predicts binding mode and orientation of covalent inhibitors. | CovDocker benchmark; methods accounting for covalent bond formation and structural changes [50]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Nucleophilic Amino Acids (Cysteine, Lysine, etc.) | Targets for covalent warhead binding. Cysteine is the most common, but new chemistries are targeting other residues [46]. |

| Covalent Warhead Libraries | Collections of electrophilic groups (e.g., acrylamides, aldehydes) with varying reactivity used to screen for optimal covalent bond formation with a target nucleophile [52] [48]. |

| DNA-Encoded Libraries (DELs) | Vast collections of small molecules, each tagged with a DNA barcode, enabling highly efficient screening for binders against immobilized protein targets [1]. |

| Stable Isotope Labels (e.g., for HDX-MS) | Used to label proteins in Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange experiments to study protein dynamics and map ligand-binding sites [49]. |

| Ultra-Large Virtual Compound Libraries (e.g., ZINC20) | Databases of billions of readily available or easily synthesizable compounds for virtual screening to discover novel chemical starting points [51]. |

Experimental Workflows and Signaling Pathways

Covalent-Allosteric Inhibition Mechanism