Comprehensive Pharmacophore-Based Virtual Screening Protocol for Kinase Inhibitors: From AI-Driven Design to Experimental Validation

This article provides a comprehensive guide to pharmacophore-based virtual screening (PBVS) for kinase inhibitor discovery, a critical methodology for addressing challenges like selectivity and resistance in oncology drug development.

Comprehensive Pharmacophore-Based Virtual Screening Protocol for Kinase Inhibitors: From AI-Driven Design to Experimental Validation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to pharmacophore-based virtual screening (PBVS) for kinase inhibitor discovery, a critical methodology for addressing challenges like selectivity and resistance in oncology drug development. We detail the foundational principles of pharmacophore modeling for kinases, explore established and cutting-edge AI-driven methodological workflows, and offer practical troubleshooting strategies to optimize screening performance. The protocol emphasizes rigorous validation through molecular dynamics, free energy calculations, and biological assays, showcasing successful applications against targets like c-Src and Janus kinases. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this resource synthesizes current best practices and emerging trends to accelerate the identification of novel, potent kinase inhibitors.

Understanding Pharmacophores and Kinase Targets: The Essential Foundation

In the field of computer-aided drug design (CADD), a pharmacophore is universally defined as "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or to block) its biological response" [1] [2]. This abstract model represents the essential molecular interaction capabilities of a compound, rather than a specific molecular framework or functional group. For kinase targets, this concept is particularly powerful because it facilitates the identification of novel inhibitors that share key interaction patterns without being constrained by specific chemical scaffolds, a process known as scaffold hopping [1]. The development of a kinase pharmacophore model enables researchers to postulate the "essence" of structure-activity relationships gained from studying series of active and inactive molecules, providing a critical tool for virtual screening and lead optimization in kinase drug discovery programs [1].

Kinases represent one of the major drug target classes amenable to small molecule inhibition. Most kinase inhibitors target the conserved ATP-binding site, yet achieving selectivity among the over 500 human kinase domains remains a significant challenge. Pharmacophore-based approaches address this challenge by mapping the common interaction features of diverse inhibitors across different kinase targets, providing a structural blueprint for designing selective compounds [3]. The retrospective analysis of chemical structures and scaffolds of drug molecules has led to the identification of structural motifs often associated with biological activity, sometimes called "privileged structures" [4]. However, it is crucial to distinguish these from pharmacophores; while privileged structures represent scaffolds that confer activity toward multiple targets, a pharmacophore represents the common molecular interaction features of a set of molecules toward their receptor [4].

Core Pharmacophore Features for Kinase Inhibition

Fundamental Steric and Electronic Features

Kinase pharmacophore models are built from a set of fundamental chemical features that mediate interactions between inhibitors and the kinase binding pocket. These features represent essential interaction points that a ligand must possess to bind effectively to the kinase target. The most relevant pharmacophore features for kinase inhibition include [1] [5]:

- Hydrogen Bond Acceptors (HBA): Atoms or groups that can accept hydrogen bonds, typically represented as vectors or spheres. Common examples in kinase inhibitors include carbonyl oxygen atoms and nitrogen atoms in heterocyclic rings.

- Hydrogen Bond Donors (HBD): Groups that can donate hydrogen bonds, such as amine groups and amide NH moieties.

- Hydrophobic Features (H): Non-polar regions that participate in van der Waals interactions, often represented as spheres. These include alkyl groups, alicycles, and weakly or non-polar aromatic rings.

- Aromatic Rings (AR): Planar ring systems that can engage in π-π stacking or cation-π interactions with tyrosine, phenylalanine, or histidine residues in the kinase binding site.

- Positive Ionizable Groups (PI): Features that can carry a positive charge under physiological conditions, such as protonated amines.

- Negative Ionizable Groups (NI): Features that can carry a negative charge, such as carboxylates.

Table 1: Core Pharmacophore Features for Kinase Inhibitors

| Feature Type | Geometric Representation | Interaction Types | Structural Examples in Kinase Inhibitors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Bond Acceptor (HBA) | Vector or Sphere | Hydrogen Bonding | Carbonyl oxygen, pyridine nitrogen, ether oxygen |

| Hydrogen Bond Donor (HBD) | Vector or Sphere | Hydrogen Bonding | Amine groups, amide NH, hydroxyl groups |

| Hydrophobic (H) | Sphere | Hydrophobic Contact | tert-Butyl groups, alicyclic rings, aromatic rings |

| Aromatic (AR) | Plane or Sphere | π-Stacking, Cation-π | Phenyl, pyridine, indole rings |

| Positive Ionizable (PI) | Sphere | Ionic, Cation-π | Protonated amines, ammonium ions |

| Negative Ionizable (NI) | Sphere | Ionic | Carboxylates, tetrazoles |

Kinase-Specific Interaction Patterns

Analysis of kinase-inhibitor complexes has revealed conserved interaction patterns that are critical for high-affinity binding. McGregor et al. explored the features of protein-ligand interactions for 220 kinase crystal structures from the Protein Data Bank, creating a comprehensive "pharmacophore map" that shows interactions made by all ligands with their receptors simultaneously [3]. This map provides invaluable insight for the design of kinase screening sets and combinatorial libraries. Key interaction patterns include:

- The hinge region interactions, where inhibitors form one to three hydrogen bonds with the backbone atoms of the kinase hinge region, a conserved structural element connecting the N-terminal and C-terminal lobes of the kinase domain.

- Gatekeeper residue interactions, where inhibitors form van der Waals contacts with the gatekeeper residue, which controls access to a hydrophobic pocket deep in the ATP-binding site.

- DFG-motif targeting, particularly for Type II inhibitors that bind to the inactive "DFG-out" conformation of kinases, engaging in specific interactions with the aspartate and phenylalanine residues of the DFG motif.

- Solvent-front interactions, where inhibitors contact residues on the solvent-exposed surface of the kinase, often contributing to selectivity profiles.

Quantitative Analysis of Kinase Pharmacophore Features

Feature Frequency and Spatial Distribution

Analysis of known kinase inhibitors reveals distinct patterns in the occurrence and spatial arrangement of pharmacophore features. The kinase pharmacophore map derived from 220 kinase crystal structures provides quantitative data on the prevalence of different interaction types and their geometric relationships [3]. This data enables the development of scoring algorithms that can identify inhibitor poses close to crystal structure configurations using only 2D chemical structure as input [3].

Table 2: Quantitative Analysis of Pharmacophore Features in Kinase Inhibitors

| Pharmacophore Feature | Frequency in Kinase Inhibitors (%) | Typical Distance Ranges (Å) | Key Kinase Residues Interacted With |

|---|---|---|---|

| H-bond Acceptor 1 | ~95% | 2.8-3.2 | Hinge region backbone NH |

| H-bond Acceptor 2 | ~65% | 2.9-3.3 | Hinge region backbone NH |

| H-bond Donor | ~45% | 2.7-3.1 | Hinge region backbone C=O |

| Hydrophobic Center 1 | ~85% | 3.5-4.5 | Gatekeeper residue |

| Hydrophobic Center 2 | ~75% | 4.0-5.0 | DFG-phenylalanine |

| Aromatic Center | ~70% | 3.8-5.0 | Catalytic lysine, other aromatic residues |

Selectivity-Determining Features

Achieving kinase selectivity remains a central challenge in inhibitor design. The pharmacophore map approach has identified key features that contribute to selectivity among kinase targets. Three crucial mutations within the ligand binding site create distinct microenvironments that can be exploited for selective inhibitor design: Phe208/Ile199 (MAO-A/MAO-B), Phe173/Leu164, and Ile335/Tyr326 [6]. These residue differences, combined with variations in cavity shape, provide a roadmap for discovering selective inhibitors [6].

The spatial arrangement of exclusion volumes—regions representing forbidden space where the ligand cannot occupy due to steric clashes with the receptor—also plays a critical role in determining selectivity. By incorporating shape constraints derived from specific kinase structures, pharmacophore models can effectively discriminate between closely related kinase targets [1].

Experimental Protocols for Kinase Pharmacophore Modeling

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling Protocol

Structure-based pharmacophore modeling utilizes the three-dimensional structure of kinase targets, often obtained from X-ray crystallography or homology modeling, to derive essential interaction features.

Protocol: Structure-Based Kinase Pharmacophore Generation

Protein Structure Preparation

- Obtain the 3D structure of the kinase target from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) or through homology modeling [5].

- Prepare the protein structure by adding hydrogen atoms, assigning correct protonation states, and optimizing hydrogen bonding networks using tools like MOE or Discovery Studio.

- Resolve any missing residues or atoms through loop modeling or energy minimization.

Binding Site Characterization

- Identify the ligand-binding site using methods such as GRID or LUDI, which detect potential interaction sites based on energetic, geometric, or evolutionary properties [5].

- For kinases, the ATP-binding site is typically the primary target, but allosteric sites may also be considered.

Interaction Feature Generation

- Analyze the binding site to identify regions complementary to pharmacophore features using software such as LigandScout or Phase.

- Generate potential features including hydrogen bond acceptors/donors, hydrophobic areas, and charged/aromatic interaction sites.

- For complexes with bound ligands, derive features directly from observed protein-ligand interactions.

Feature Selection and Model Refinement

- Select features most critical for ligand binding by considering conserved interactions across multiple kinase structures.

- Incorporate exclusion volumes to represent steric constraints of the binding pocket.

- Validate the model by screening known active and inactive compounds to optimize selectivity.

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling Protocol

When 3D structures of the kinase target are unavailable, ligand-based approaches can generate pharmacophore models using known active compounds.

Protocol: Ligand-Based Kinase Pharmacophore Generation

Compound Selection and Conformational Analysis

- Curate a diverse set of known active kinase inhibitors with measured activity data (IC₅₀ or Kᵢ values) from databases like ChEMBL [7].

- Include inactive compounds to enhance model selectivity.

- Generate representative conformational ensembles for each compound using systematic or stochastic methods.

Common Pharmacophore Identification

- Identify common spatial arrangements of pharmacophore features across active compounds using algorithms such as HipHop or HypoGen [2].

- Use software tools like Phase or MOE to generate multiple pharmacophore hypotheses.

Model Validation and Optimization

- Validate models by screening against test sets of active and inactive compounds.

- Optimize model parameters to maximize enrichment of active compounds.

- Select the best model based on statistical metrics and chemical intuition.

Machine Learning-Accelerated Pharmacophore Screening

Modern approaches integrate machine learning with pharmacophore-based screening to accelerate virtual screening of large compound libraries.

Protocol: ML-Enhanced Pharmacophore Screening

Training Data Generation

- Perform molecular docking of a diverse compound set against the kinase target to generate docking scores.

- Calculate molecular descriptors and fingerprints for all compounds.

Model Training and Validation

- Train machine learning models (e.g., random forest, neural networks) to predict docking scores from molecular descriptors.

- Validate model performance using cross-validation and external test sets.

Pharmacophore-Constrained Screening

- Apply pharmacophore filters to large compound libraries (e.g., ZINC) to create focused subsets.

- Use trained ML models to rapidly predict docking scores for pharmacophore-matched compounds.

- Select top-ranking compounds for synthesis and experimental validation.

This approach has been shown to accelerate binding energy predictions by up to 1000 times compared to classical docking-based screening while maintaining high accuracy [6].

Research Reagent Solutions for Kinase Pharmacophore Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Software Tools

| Tool/Reagent | Type/Category | Primary Function | Application in Kinase Pharmacophore Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| LigandScout | Software | Structure-based & ligand-based pharmacophore modeling | Advanced pharmacophore model generation with intuitive visualization [8] |

| MOE | Software | Molecular modeling suite | Comprehensive pharmacophore modeling, docking, and QSAR analysis [2] |

| Phase | Software | Pharmacophore modeling platform | Ligand-based pharmacophore generation and virtual screening [2] [8] |

| ELIXIR-A | Software | Pharmacophore refinement tool | Alignment and refinement of pharmacophore models from multiple ligands/receptors [8] |

| ZINC Database | Compound Library | Database of commercially available compounds | Source of compounds for virtual screening [6] |

| ChEMBL Database | Bioactivity Database | Database of bioactive molecules | Source of activity data for ligand-based modeling [7] |

| Protein Data Bank | Structure Database | Repository of 3D protein structures | Source of kinase structures for structure-based modeling [5] |

| Smina | Software | Molecular docking | Docking scoring function for structure-based pharmacophore validation [6] |

Implementation in Virtual Screening Workflow

The integration of pharmacophore modeling into a comprehensive virtual screening workflow for kinase inhibitors involves multiple stages that combine both structure-based and ligand-based approaches.

Integrated Virtual Screening Protocol

Target Analysis and Data Collection

- Gather 3D structures of the kinase target from PDB or through homology modeling.

- Collect known active and inactive compounds from databases like ChEMBL.

Multi-Method Pharmacophore Model Generation

- Develop both structure-based and ligand-based pharmacophore models.

- Use tools like ELIXIR-A to align and refine models from different sources [8].

Hierarchical Screening Approach

- Apply pharmacophore filters as a first rapid screening step to reduce library size.

- Use machine learning models to predict docking scores for pharmacophore-matched compounds [6].

- Perform molecular docking on top-ranking compounds for detailed binding pose analysis.

Experimental Validation

- Select top compounds for synthesis and biochemical testing.

- Iteratively refine pharmacophore models based on experimental results.

This integrated approach leverages the strengths of pharmacophore modeling for rapid screening while incorporating machine learning and docking for enhanced prediction accuracy, creating an efficient pipeline for identifying novel kinase inhibitors [6].

Protein kinases constitute one of the largest protein families in the human genome, with approximately 518 members identified to date [9]. These enzymes catalyze the transfer of phosphate groups from adenosine triphosphate (ATP) to specific substrates, thereby regulating critical cellular processes including signal transduction, cell cycle progression, differentiation, metabolism, and apoptosis [9] [10]. The precise control of kinase activity is crucial for cellular homeostasis, and dysregulation due to mutations, overexpression, or abnormal signaling contributes to a range of human diseases, particularly cancer [10]. Nearly 30 tumor suppressor genes and over 100 oncogenes are protein kinases, underscoring their pivotal roles in cancer biology [10].

The development of kinase-targeted therapeutics represents a landmark achievement in molecular medicine. Since the approval of imatinib in 2001, the first molecular-targeted drug for cancer treatment, kinase inhibitors have transformed oncology treatment paradigms [11]. Over the past two decades, the FDA has approved more than 70 small molecule kinase inhibitors, with numerous others in various stages of clinical development [11] [9]. Despite these successes, developing selective kinase inhibitors remains challenging due to structural conservation within the kinase family and the evolution of resistance mechanisms [11] [10].

Structural Basis of Kinase Inhibition Challenges

Conserved Architecture of the Kinase Domain

The high degree of structural conservation among protein kinases presents the fundamental challenge for selective inhibitor design. The characteristic architecture of the kinase catalytic domain consists of a small amino-terminal N-lobe and a large carboxy-terminal C-lobe connected by a hinge region [9] [10]. Table 1 summarizes the key structural elements and their functional roles.

Table 1: Key Structural Elements of the Kinase Catalytic Domain

| Structural Element | Location | Functional Role | Conservation Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hinge Region | Connects N-lobe and C-lobe | Mediates hydrogen bonding with ATP adenine ring | High sequence conservation limits selectivity |

| Glycine-rich Loop (P-loop) | N-lobe (between β1-β2) | Folds over nucleotide; contacts phosphate groups | GxGxxG motif highly conserved across kinases |

| Catalytic Loop | C-lobe | Contains HRD motif essential for phosphotransfer | HRD motif nearly universal in protein kinases |

| Activation Loop | C-lobe | Begins with DFG motif; regulates kinase activity | DFG motif present in most protein kinases |

| αC-Helix | N-lobe | Adopts "in" or "out" conformation for activation | Structural flexibility complicates drug design |

The ATP-binding pocket, where the majority of kinase inhibitors bind, is particularly conserved across the kinome [11] [9]. This pocket contains a hydrophobic region that accommodates the adenine ring of ATP, with key hydrogen bonds forming between the adenine and the hinge region backbone [10]. The structural similarity of ATP-binding pockets among human kinases has forced drug developers to search for alternative strategies for developing selective inhibitors [10].

Classification of Kinase Inhibitor Binding Modes

Kinase inhibitors are categorized based on their binding mechanisms and interaction sites within the kinase domain. Table 2 outlines the primary classes of kinase inhibitors and their characteristics.

Table 2: Classification of Kinase Inhibitors by Binding Mechanism

| Inhibitor Type | Binding Site | Mechanism of Action | Selectivity Profile | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type I | ATP-binding pocket (active conformation) | Competes directly with ATP; targets active DFG-in conformation | Lower selectivity due to conserved ATP pocket | Imatinib, Gefitinib |

| Type II | ATP-binding pocket (inactive conformation) | Binds adjacent hydrophobic pocket; targets inactive DFG-out conformation | Moderate selectivity from unique inactive states | Sorafenib, Ponatinib |

| Type III (Allosteric) | Site distal to ATP pocket | Induces conformational changes; non-competitive with ATP | Higher selectivity through targeting unique regions | Trametinib |

| Type IV (Substrate-competitive) | Substrate binding site | Competes with protein substrate rather than ATP | Potentially high selectivity | Under investigation |

| Covalent Inhibitors | ATP pocket with cysteine targeting | Forms irreversible covalent bond with nucleophilic cysteine | High selectivity if cysteine unique to target | Ibrutinib |

The pursuit of Type III and IV inhibitors, along with covalent inhibition strategies, represents promising approaches to overcome the selectivity challenges inherent to ATP-competitive compounds [11] [10]. Allosteric inhibitors that bind to sites other than the ATP pocket can achieve greater specificity by exploiting structural differences outside the conserved catalytic cleft [10].

Computational Approaches for Selective Kinase Inhibitor Design

Pharmacophore-Based Virtual Screening Protocol

Pharmacophore-based virtual screening (PBVS) has emerged as a powerful ligand-based strategy for identifying novel kinase inhibitors with enhanced selectivity profiles [12] [13]. This approach defines the essential molecular features necessary for biological activity, providing a template for screening compound libraries. The following protocol outlines a comprehensive PBVS workflow for kinase inhibitor discovery.

Protocol 1: Pharmacophore-Based Virtual Screening for Kinase Inhibitors

Step 1: Pharmacophore Model Generation

- Reference Ligand Selection: Identify high-affinity, selective kinase inhibitors with known binding modes from structural biology data or literature. For Src kinase, bosutinib or dasatinib may serve as reference compounds [11] [12].

- Feature Definition: Map critical chemical features including hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions, aromatic rings, and ionizable groups based on the reference ligand's interaction with the kinase binding pocket [14] [12].

- Model Validation: Validate the pharmacophore model using a set of known active and inactive compounds to ensure discrimination capability. Aim for enrichment factors >3 and high early recovery rates of actives [13].

Step 2: Virtual Screening Implementation

- Compound Library Preparation: Curate a diverse chemical library (e.g., ZINC15, ChemBridge) with drug-like properties. Apply appropriate ionization states and generate conformational ensembles for each compound [15] [12].

- Pharmacophore Screening: Screen the entire library against the pharmacophore model using software such as Catalyst or ZINCPharmer. This step typically reduces the library size by 90-99% by eliminating compounds that don't match the essential features [14] [12].

- Selectivity Filtering: Apply kinase-specific filters to prioritize compounds with potential selectivity, such as exclusion of pan-kinase inhibitor features or inclusion of features targeting unique subpockets [11].

Step 3: Molecular Docking and Binding Affinity Assessment

- Protein Structure Preparation: Obtain the target kinase structure from PDB (e.g., 3U4W for c-Src). Add hydrogen atoms, assign partial charges, and optimize side-chain orientations using molecular mechanics force fields [12].

- Focused Docking: Perform molecular docking of pharmacophore-matched compounds against the target kinase using programs such as AutoDock, GOLD, or Glide. Define the binding site with a grid centered on the ATP-binding pocket [12].

- Binding Mode Analysis: Visually inspect top-ranking poses to ensure critical ligand-protein interactions (e.g., hinge region hydrogen bonds, specific interactions with selectivity residues) are maintained [12].

Step 4: Selectivity Assessment and Hit Prioritization

- Cross-Kinase Screening: Dock top candidates against structurally related kinases (e.g., Src family kinases) to assess potential selectivity. Prioritize compounds showing significant binding energy differences (>2 kcal/mol) [11].

- ADMET Prediction: Evaluate pharmacokinetic properties using QSAR models, including permeability, metabolic stability, and potential toxicity. Apply filters such as Lipinski's Rule of Five and PAINS exclusion [15] [12].

- Final Hit Selection: Select 10-20 compounds for experimental validation based on comprehensive assessment of binding energy, interaction quality, selectivity potential, and drug-like properties [12].

Benchmark Comparison of Virtual Screening Methods

Comparative studies have demonstrated that PBVS frequently outperforms docking-based virtual screening (DBVS) in retrieval of active compounds from large chemical libraries [13]. In a comprehensive benchmark against eight diverse targets, PBVS achieved higher enrichment factors in fourteen of sixteen virtual screening scenarios [13]. The average hit rates at 2% and 5% of the highest ranks of entire databases were significantly higher for PBVS compared to DBVS methods [13]. This superior performance is attributed to PBVS's ability to capture essential interaction features while accommodating some structural flexibility.

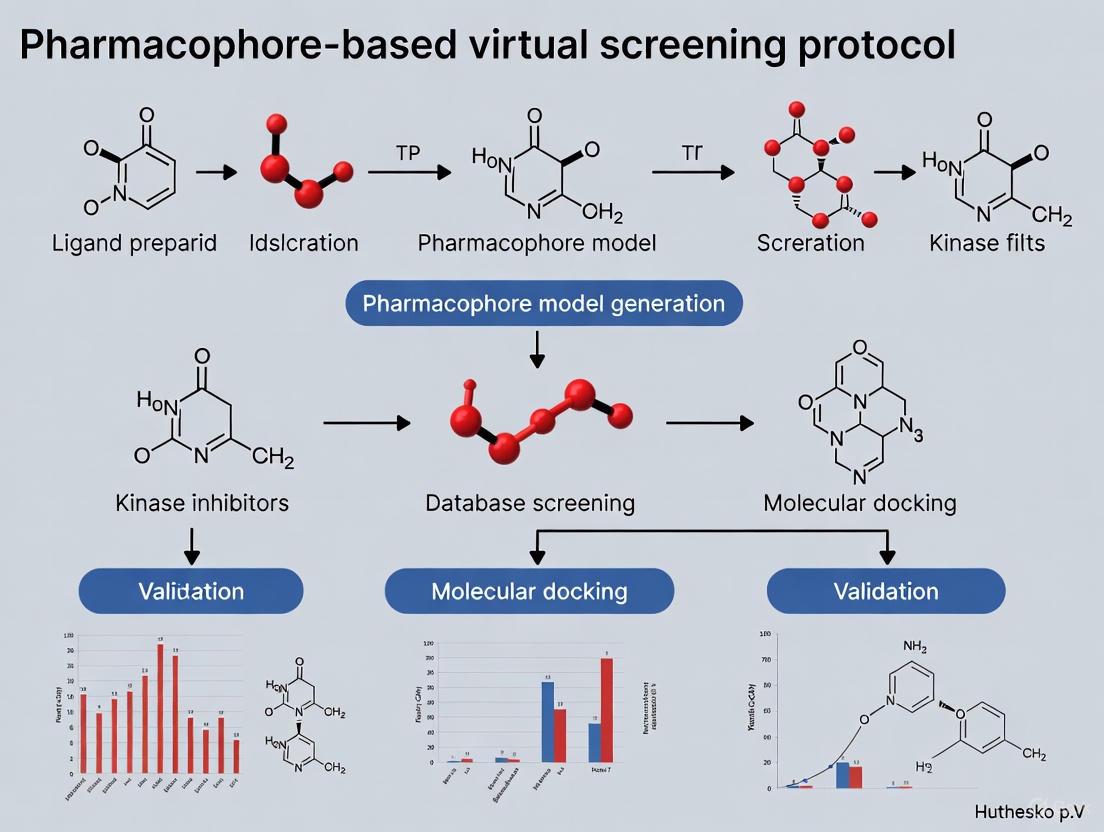

Figure 1: Pharmacophore-Based Virtual Screening Workflow for Kinase Inhibitor Discovery

Case Study: Application to Src Kinase Inhibitor Discovery

Src Kinase as a Challenging Selectivity Target

Src kinase, a non-receptor tyrosine kinase, exemplifies the challenges of selective kinase inhibitor development [11]. As the prototypical member of the Src kinase family (SFK), which includes nine additional structurally similar kinases, Src displays high conservation in its ATP-binding pocket [11]. Despite decades of research, no Src-selective kinase inhibitors have entered clinical use, highlighting the difficulties in achieving selectivity among closely related kinases [11].

In a recent study, researchers implemented a comprehensive virtual screening approach to identify novel c-Src kinase inhibitors with improved selectivity profiles [12]. The protocol screened 500,000 small molecules from the ChemBridge commercial library using pharmacophore-based virtual screening followed by molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulations [12]. This integrated approach identified several promising candidates, with the top hit (compound 71736582) demonstrating potent inhibition of c-Src-mediated kinase activity (IC50: 517 nM) compared to the positive control bosutinib (IC50: 408 nM) [12].

Experimental Validation of Computational Predictions

The transition from computational prediction to experimental validation represents a critical phase in kinase inhibitor development. The following protocol outlines a rigorous experimental framework for validating computational predictions of kinase inhibitor activity and selectivity.

Protocol 2: Experimental Validation of Kinase Inhibitor Selectivity

Step 1: Biochemical Kinase Activity Profiling

- Kinase Assay Selection: Implement biochemical kinase assays (e.g., mobility shift, FRET, or radiometric assays) to measure compound potency against the target kinase [12] [16].

- Initial Potency Assessment: Determine IC50 values for top computational hits across a concentration range (typically 0.1 nM to 10 μM) using recombinant kinase protein [12].

- Selectivity Profiling: Utilize kinase profiling services (e.g., DiscoverX, Millipore) to screen compounds against a panel of 50-100 diverse kinases at a single concentration (e.g., 1 μM) [16].

- Selectivity Score Calculation: Calculate selectivity scores (S(1μM) or S(10μM)) based on the percentage of kinases inhibited beyond a specific threshold (typically >90% inhibition) [16].

Step 2: Cellular Target Engagement Assessment

- Cell Line Selection: Choose relevant cancer cell lines with documented expression of the target kinase and pathway activation (e.g., MDA-MB-231 for Src kinase) [12].

- Cellular Potency Determination: Assess compound effects on cell viability using MTT, MTS, or CellTiter-Glo assays. Calculate GI50 values following 72-hour exposure [12].

- Pathway Modulation Analysis: Evaluate target engagement in cells via Western blotting for phosphorylation of direct kinase substrates and downstream pathway components [12].

- Phenotypic Response Characterization: Assess functional responses to kinase inhibition, such as effects on migration, invasion, or cell cycle progression, using appropriate assays [11].

Step 3: Binding Mode Confirmation

- X-ray Crystallography: Pursue co-crystal structures of lead compounds with the target kinase to verify predicted binding modes and interactions [11].

- Cellular Target Engagement Probes: Utilize techniques such as cellular thermal shift assays (CETSA) to confirm direct target engagement in intact cells [16].

Step 4: Resistance Profiling

- Mutation Analysis: Evaluate compound activity against clinically relevant kinase mutants to assess resistance potential [11].

- Bypass Pathway Assessment: Investigate compensatory pathway activation following prolonged inhibitor treatment through phosphoproteomic analysis [11].

Research Reagent Solutions for Kinase Inhibitor Development

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Kinase Inhibitor Screening and Validation

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Application Purpose | Key Features & Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kinase Assay Systems | ADP-Glo, LanthaScreen, Caliper Mobility Shift | Biochemical activity screening | Homogeneous format, suitable for HTS, kinetic capability |

| Recombinant Kinases | Active Src, Abl, EGFR, CDK2 | Target-based screening | Catalytic domain vs. full-length, activation status |

| Kinase Profiling Services | DiscoverX KinomeScan, Eurofins KinaseProfiler | Selectivity assessment | Broad kinome coverage, standardized conditions |

| Cell Line Models | MDA-MB-231, A549, HCT-116, Ba/F3 | Cellular activity evaluation | Target relevance, pathway activation, genetic background |

| Pathway Antibodies | Phospho-Src (Tyr416), Phospho-FAK (Tyr397) | Cellular target engagement | Specificity validation, application-appropriate |

| Chemical Libraries | ChemBridge, ZINC15, Selleckchem FDA-approved | Compound sourcing for screening | Diversity, drug-like properties, known bioactives |

| Structural Biology Resources | Kinase expression constructs, Crystallization screens | Binding mode determination | High-yield expression, crystallization conditions |

Emerging Technologies and Future Perspectives

The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning with traditional structure-based drug design is accelerating the development of next-generation kinase inhibitors with enhanced selectivity profiles [11] [17]. Deep learning-enhanced QSAR models are demonstrating remarkable capability in automating feature extraction and capturing complex structure-activity relationships that surpass traditional QSAR approaches [17]. These methods are particularly valuable for predicting kinome-wide selectivity profiles and optimizing chemical scaffolds to minimize off-target interactions [17].

Novel therapeutic modalities beyond conventional ATP-competitive inhibition are also emerging as promising strategies to overcome selectivity challenges. Targeted protein degradation technologies, such as proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs), are being explored to achieve enhanced selectivity through cooperative binding events that require simultaneous engagement of both the kinase and E3 ubiquitin ligase [11] [10]. Allosteric inhibition approaches continue to advance, with several compounds in clinical development that exploit unique structural features outside the conserved ATP-binding pocket [11].

Figure 2: Challenges and Innovative Solutions in Selective Kinase Inhibitor Design

The future of selective kinase inhibitor design will likely involve increasingly sophisticated computational-experimental feedback loops, where machine learning models trained on large-scale kinase profiling data inform the design of novel chemical scaffolds, which in turn generate new data to refine predictive models [17] [16]. This iterative approach, combined with structural insights and emerging therapeutic modalities, holds significant promise for addressing the persistent challenge of achieving selectivity in kinase drug discovery.

A pharmacophore is an abstract model that defines the ensemble of steric and electronic features essential for a molecule to interact with a biological target and trigger its biological response [2]. In the context of kinase inhibitor research, pharmacophore models serve as powerful tools for identifying and optimizing compounds that can selectively target the ATP-binding site or allosteric pockets of kinases. These models capture the critical supramolecular interactions necessary for high-affinity binding, providing a blueprint for virtual screening and rational drug design [2]. The core features—hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions, and aromatic interactions—represent the fundamental language of molecular recognition between kinase inhibitors and their protein targets. This application note details the core components of pharmacophore models and provides established protocols for their application in virtual screening campaigns for kinase inhibitors, with a specific focus on practical implementation for research scientists.

Core Components of a Pharmacophore Model

Quantitative Definition of Pharmacophore Features

Table 1: Core Pharmacophore Features and Their Characteristics

| Feature Type | Electronic/Steric Role | Complementary Protein Environment | Typical Kinase Interactions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Bond Acceptor | Electron-rich atom (e.g., O, N) capable of accepting a hydrogen bond [2] | Hydrogen bond donor (e.g., backbone NH from hinge region) [18] | Hinge region binding (e.g., Val/Met/Gly-rich loop) |

| Hydrogen Bond Donor | Hydrogen atom attached to an electronegative atom (e.g., N-H, O-H) [2] | Hydrogen bond acceptor (e.g., backbone carbonyl oxygen) [18] | Hinge region binding; interaction with catalytic lysine |

| Hydrophobic Region | Region of low polarity; often aliphatic or aromatic carbon chains [2] | Hydrophobic subpocket (e.g., gatekeeper residue region, DFG motif vicinity) [18] | Interaction with hydrophobic back pocket and gatekeeper residue |

| Aromatic Interaction | Electron-rich π-system (e.g., phenyl, heteroaryl rings) [19] | Cationic residues (Lys, Arg), other π-systems (π-π stacking) [18] | Cation-π interaction with catalytic lysine; π-stacking with His/Phe/Tyr |

Detailed Feature Analysis and Kinase Relevance

Hydrogen Bond Donors and Acceptors form the cornerstone of specificity in kinase inhibitor design. These features are typically directional interactions that precisely align the inhibitor within the kinase's hinge region, a segment that connects the N- and C-terminal lobes of the kinase domain. The hydrogen-bonding pattern between the inhibitor and the hinge region's backbone atoms often determines the base level of binding affinity. In pharmacophore modeling, these features are defined not only by their chemical identity but also by their vector directionality and optimal distance ranges to complementary protein features [18]. In a study targeting c-Src kinase, specific hydrogen-bonding interactions at the kinase binding site were critical for identifying potent inhibitors through pharmacophore-based virtual screening [20] [12].

Hydrophobic Regions contribute significantly to the binding affinity through entropy-driven processes and van der Waals interactions. In kinases, these features typically map to the adenine-binding pocket, the hydrophobic back pocket near the gatekeeper residue, and the region associated with the DFG (Asp-Phe-Gly) motif. The spatial placement of hydrophobic features in a pharmacophore model helps exploit these conserved yet structurally distinct pockets, offering opportunities for achieving selectivity among kinase family members. Generation of hydrophobic pharmacophore elements often involves computational methods like k-means clustering of grid points with favorable hydrophobic scores within the binding site [18].

Aromatic Interactions, including π-π stacking and cation-π interactions, provide substantial binding energy and can be crucial for anchoring inhibitors in specific orientations. The catalytic lysine residue, which is highly conserved across the kinase family, often participates in cation-π interactions with aromatic ring systems of inhibitors. Aromatic features in a pharmacophore can be derived from the spatial orientation of protein aromatic rings or from known ligand interactions, and are often represented as ring centroids or normal vectors [18] [19].

Experimental Protocols for Pharmacophore Modeling

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Generation Protocol

This protocol generates a pharmacophore model directly from a protein structure with a defined binding site, without prior ligand information. It is particularly valuable for kinase targets where few active ligands are known.

Workflow: Structure-Based Pharmacophore Generation

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Protein Structure Preparation

- Obtain a high-resolution crystal structure of the kinase target from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). For kinases, structures in the DFG-in conformation are often preferred for Type I inhibitors.

- Prepare the protein structure by adding hydrogen atoms, assigning correct protonation states for residues (especially catalytic Asp and Glu), and optimizing hydrogen bonding networks. The

PDBbinddatabase provides pre-processed structures suitable for this purpose [18].

Binding Site Definition and Grid Generation

- Define the binding site of interest. For kinase ATP-site inhibitors, the centroid of a co-crystallized ligand or the conserved hinge region serves as an appropriate center.

- Project a 3D grid with 0.4 Å spacing into the binding site. The grid should extend at least 4-6 Å beyond the expected dimensions of a typical ligand [18].

Molecular Interaction Field (MIF) Calculation

- Compute interaction potentials between protein atoms and molecular probes placed at each grid point. Use scoring functions such as a continuous form of the ChemScore to evaluate hydrogen-bonding and hydrophobic potentials [18].

- Employ specific probes: hydrogen-bond donor, hydrogen-bond acceptor, hydrophobic, aromatic, and ionic probes. The interaction energy at each grid point indicates the favorability of that specific interaction type.

Pharmacophore Feature Identification

- Hydrophobic Features: Apply k-means clustering over all grid points with favorable hydrophobic scores. The number of clusters (k) is adjusted until the minimum distance between cluster centers reaches a predefined cutoff (e.g., 2.0 Å). The hydrophobic pharmacophore element is the energy-weighted geometric center of each cluster [18].

- Hydrogen-Bonding, Aromatic, and Ionic Features: For these specific interactions, group grid points associated with the same nearest functional group (e.g., a specific backbone carbonyl). Perform k-means clustering within this group or calculate a single energy-weighted geometric center using the formula:

c = Σ(x_i · ε_i), wherex_iandε_iare the coordinates and interaction potential of grid pointi, respectively [18]. - Introduce distance restraints, the Interaction Range for Pharmacophore Generation (IRFPG), to the scoring function to ensure pharmacophore elements are placed at biologically relevant distances from protein atoms [18].

Feature Selection and Model Validation

- Select the most critical features to create a pharmacophore hypothesis. A typical kinase ATP-site pharmacophore includes 3-5 key features.

- Validate the model by screening a small set of known active and inactive compounds. Assess the model's ability to enrich active compounds and its discriminatory power.

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Generation Protocol

This protocol is used when several active kinase inhibitors are known but a protein structure may be unavailable.

Workflow: Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Generation

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Ligand Dataset Curation

- Compile a set of 20-30 structurally diverse kinase inhibitors with confirmed activity. Include potency data (IC₅₀ or Kᵢ values) if available for quantitative model development.

- Prepare all ligand structures by generating plausible 3D conformations, optimizing geometry, and assigning correct ionization states at physiological pH.

Conformational Analysis and Feature Annotation

- Perform a comprehensive conformational analysis for each ligand to sample the low-energy 3D space. Tools like RDKit or CONFGEN can generate multiple conformers [21].

- Annotate all potential pharmacophore features (hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions, aromatic rings, ionizable groups) on each conformer using software such as LigandScout or Phase [2].

Multi-Ligand Alignment and Common Feature Identification

- Align the active molecules based on their pharmacophore features rather than chemical structure. This identifies the maximum common pharmacophore shared by all active compounds.

- Develop a pharmacophore hypothesis that includes the essential features common to the aligned active molecules. The hypothesis should explain the observed activity data.

Model Validation and Refinement

- Validate the model using statistical methods (e.g., Fischer's randomization) and by screening a test set of active and decoy molecules.

- Refine the model by adjusting feature definitions and tolerances based on validation results.

Application in Virtual Screening for Kinase Inhibitors

Implementation in a Screening Pipeline

The validated pharmacophore model serves as a 3D query to screen large chemical libraries. The screening process identifies molecules that match the spatial arrangement of the defined features.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool/Resource Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Pharmacophore Modeling Software | LigandScout [2], Phase [2], MOE, Catalyst/Discovery Studio [2] | Model building, visualization, and virtual screening |

| Docking Software | PLANTS [21] | Flexible ligand docking and pose generation |

| Chemical Libraries | ChemBridge Library [20] [12], National Cancer Institute (NCI) Library [22], ZINC database | Source of compounds for virtual screening |

| Protein Structure Resources | Protein Data Bank (PDB) [21], PDBbind database [18] | Source of experimentally determined structures for structure-based modeling |

| Conformer Generation | RDKit [21] [19], CONFGEN [21] | Generation of multiple 3D conformations for ligands |

Case Study: c-Src Kinase Inhibitor Discovery

A recent study demonstrated the successful application of pharmacophore-based virtual screening to identify novel c-Src kinase inhibitors [20] [12]. Researchers screened 500,000 small molecules from the ChemBridge library using a pharmacophore model. This process identified 29 top-ranked molecules, which were further refined to 4 lead compounds through visual inspection of protein-ligand interactions. Molecular dynamics simulations (200 ns) confirmed the stability of two inhibitors at the c-Src kinase binding site. The top hit, compound 71736582, exhibited excellent anticancer potential against various cancer cell lines and inhibited c-Src-mediated kinase activity (IC₅₀: 517 nM), comparable to the positive control bosutinib (IC₅₀: 408 nM) [20] [12].

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

Recent advances integrate pharmacophore modeling with deep learning approaches. For instance, PharmRL uses a deep geometric reinforcement learning algorithm to select optimal subsets of interaction points to form a pharmacophore, demonstrating superior performance in virtual screening [19]. Another method, PGMG (Pharmacophore-Guided deep learning approach for bioactive Molecule Generation), uses pharmacophore hypotheses as input to generate novel bioactive molecules with high validity, uniqueness, and novelty [23].

Shape-focused pharmacophore models like those generated by the O-LAP algorithm represent another advancement. O-LAP creates cavity-filling models by clustering overlapping atomic content from docked active ligands, then uses these models to rescore docking poses, significantly improving enrichment rates in virtual screening [21].

In the targeted search for kinase inhibitors, pharmacophore-based virtual screening stands as a pivotal technique for efficiently identifying novel hit compounds. A pharmacophore is defined as "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target and to trigger (or block) its biological response" [5]. For kinase targets, which often present highly conserved ATP-binding sites, the strategic choice between ligand-based and structure-based pharmacophore modeling approaches can significantly impact the success and efficiency of a drug discovery campaign [24] [25]. This application note provides a detailed comparative analysis of these two fundamental methodologies, offering structured protocols and decision-making frameworks to guide researchers in selecting and implementing the optimal strategy for their specific kinase project.

Technical Comparison: Core Methodologies

The two primary approaches to pharmacophore modeling differ fundamentally in their starting information and generation processes, each with distinct advantages and implementation requirements.

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

Ligand-based approaches derive pharmacophore models exclusively from the structural and chemical properties of known active compounds, without requiring 3D target structure information [5] [26]. The underlying principle posits that compounds sharing common chemical functionalities in a similar spatial arrangement likely exhibit similar biological activity against the same target [5] [25].

- Key Techniques: The workflow typically involves generating multiple 3D conformations of known active ligands, performing structural alignment, and identifying common chemical features critical for molecular recognition and activity [26]. These features are translated into a 3D pharmacophore hypothesis containing hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic areas, aromatic rings, and ionizable groups [5].

- Validation Methods: Generated models are rigorously validated using datasets containing both active compounds and inactive decoys to assess their ability to distinguish true positives from false positives [26] [27]. Statistical metrics including sensitivity, specificity, enrichment factor, and goodness of hit scores quantify model performance [27].

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

Structure-based methods generate pharmacophore models directly from the 3D structure of the target protein, typically derived from X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, or cryo-electron microscopy [5] [28]. For kinase targets, this often involves analyzing protein-ligand co-crystal structures to identify key interaction points.

- Key Techniques: The process begins with critical protein structure preparation, including protonation state assignment and missing residue modeling [5] [27]. The binding site is then analyzed to map potential interaction features complementary to the protein's functional groups [5]. Exclusion volumes are incorporated to represent spatial restrictions of the binding pocket shape [5].

- Implementation Considerations: When a protein-ligand complex structure is available, feature selection can be guided by the ligand's bioactive conformation, resulting in higher-quality models [5]. In the absence of bound ligand, all possible interaction points in the binding site are detected, often requiring manual refinement to select the most biologically relevant features [5].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Pharmacophore Modeling Approaches for Kinase Targets

| Parameter | Ligand-Based Approach | Structure-Based Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Required Input Data | Set of known active compounds [26] | 3D protein structure (X-ray, NMR, Cryo-EM) [5] [28] |

| Feature Generation | Derived from ligand alignment and common chemical features [26] | Mapped from protein binding site or protein-ligand interactions [5] |

| Scaffold Hopping Potential | Moderate to high (depends on model flexibility) [5] | High (focuses on complementary interactions) [5] |

| Handling Protein Flexibility | Limited (implicit in diverse ligand conformations) | Can be addressed through multiple structures or MD simulations [27] |

| Key Advantages | No protein structure required; Directly captures ligand activity data [28] | Direct structural insights; Can identify novel binding motifs [28] |

| Primary Limitations | Dependent on known chemotypes; May miss novel interaction patterns | Requires high-quality structure; Sensitive to binding site conformation [28] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling for Kinase Inhibitors

This protocol outlines the steps for developing a ligand-based pharmacophore model to identify novel kinase inhibitors, adapted from successful implementations for EGFR/VEGFR2 and JAK kinase inhibitors [24] [25].

Compound Selection and Preparation:

- Curate a diverse set of 20-30 confirmed active compounds with measured IC₅₀ or Ki values against your kinase target from literature or databases like ChEMBL [24].

- Prepare 3D structures of all compounds using molecular modeling software (e.g., MOE). Generate multiple low-energy conformers for each compound to account for flexibility [29].

Pharmacophore Model Generation:

- Perform 3D alignment of the generated conformers using flexible alignment algorithms [26].

- Identify common chemical features (hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic areas, ionizable groups, aromatic rings) shared across the aligned active compounds [26] [24].

- Generate initial pharmacophore hypotheses using software such LigandScout, MOE, or open-source tools like Phramer [26].

Model Validation and Refinement:

- Validate generated models using a separate test set of known active compounds and decoy molecules (inactive or random compounds) [26] [27].

- Calculate statistical metrics (sensitivity, specificity, enrichment factor) to quantify model performance [27].

- Select the best-performing model based on validation statistics for virtual screening [24].

Protocol 2: Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling for Kinase Targets

This protocol details structure-based pharmacophore generation, exemplified by studies on FAK1 and c-Src kinases [20] [27].

Protein Structure Preparation:

- Obtain the 3D structure of your kinase target from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). Prioritize high-resolution structures (<2.2 Å) co-crystallized with an inhibitor [27].

- Prepare the protein structure by adding hydrogen atoms, assigning protonation states, and correcting any missing residues or atoms using modeling software [5] [27].

- For structures with missing loops or regions, employ homology modeling with tools like MODELLER [27].

Binding Site Analysis and Feature Mapping:

- Define the binding site around the co-crystallized ligand or known catalytic region (e.g., ATP-binding site for kinases) [5].

- Identify key interaction features (hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic patches, charged interactions) between the protein and a reference ligand [5] [27].

- Use software such as Pharmit or LigandScout to automatically detect and map pharmacophore features from the protein-ligand complex [27].

Model Generation and Optimization:

- Generate an initial structure-based pharmacophore model containing 5-7 key features [27].

- Incorporate exclusion volumes to represent steric constraints of the binding pocket [5].

- Refine the model by selecting features most critical for binding affinity, potentially removing redundant or less contributive features to enhance model selectivity [5].

Diagram 1: Workflow for ligand-based and structure-based pharmacophore modeling.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Pharmacophore Modeling Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Tools & Databases | Key Functionality | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Structure Databases | RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB) [5] [27] | Repository of experimentally determined 3D protein structures | Source of kinase structures for structure-based modeling |

| Chemical Databases | ZINC [27] [6], ChEMBL [6] | Libraries of commercially available compounds & bioactivity data | Virtual screening compound sources & training set curation |

| Modeling Software | Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) [29] [26], LigandScout [26] | Integrated computational chemistry software for model generation | Ligand-based & structure-based pharmacophore development |

| Web Servers | Pharmit [26] [27], PharmMapper [26] | Online platforms for pharmacophore screening & modeling | Structure-based model creation & virtual screening |

| Validation Resources | DUD-E [27] | Database of useful decoys for virtual screening evaluation | Pharmacophore model validation with active/inactive compounds |

Application Case Studies in Kinase Research

Dual EGFR and VEGFR2 Kinase Inhibitors (Ligand-Based Approach)

A ligand-based pharmacophore modeling study successfully identified dual inhibitors of EGFR and VEGFR2 tyrosine kinases [24]. Researchers developed separate pharmacophore models for each target using known inhibitors (erlotinib for EGFR and axitinib for VEGFR2) [24]. These models were used to screen the ZINC database, followed by molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulations. The workflow identified two promising compounds (ZINC16525481 and ZINC38484632) that demonstrated stable binding interactions with both kinase targets, illustrating the power of ligand-based approaches for multi-target inhibitor design [24].

FAK1 Kinase Inhibitors (Structure-Based Approach)

In a structure-based study targeting Focal Adhesion Kinase 1 (FAK1), researchers developed pharmacophore models from the FAK1-P4N co-crystal structure (PDB ID: 6YOJ) [27]. After validating models using active compounds and decoys from the DUD-E database, virtual screening of the ZINC database identified several promising hits [27]. Molecular dynamics simulations and MM/PBSA binding free energy calculations confirmed that candidate ZINC23845603 showed strong binding affinity and interaction features similar to the known inhibitor P4N, demonstrating the utility of structure-based approaches for identifying novel kinase inhibitors with confirmed binding stability [27].

c-Src Kinase Inhibitors (Integrated Approach)

A comprehensive virtual screening campaign for c-Src kinase inhibitors employed structure-based pharmacophore modeling followed by high-throughput virtual screening of 500,000 compounds from the ChemBridge library [20]. The integrated approach included ADME analysis, molecular docking, and molecular dynamics simulations, ultimately identifying four promising candidates [20]. Biological validation confirmed that the top hit (compound 71736582) exhibited excellent anticancer potential against various cancer cell lines and inhibited c-Src-mediated kinase activity with an IC₅₀ of 517 nM, comparable to the positive control bosutinib [20].

Table 3: Decision Matrix for Approach Selection in Kinase Projects

| Project Scenario | Recommended Approach | Rationale | Implementation Tips |

|---|---|---|---|

| Novel Kinase Target with Limited Structural Data | Ligand-Based | Leverages known actives when 3D structures are unavailable [28] | Use diverse chemotypes in training set to maximize feature diversity |

| High-Resolution Co-Crystal Structure Available | Structure-Based | Directly exploits atomic-level binding site information [5] [27] | Include water-mediated interactions if structurally conserved |

| Selectivity Campaign Across Kinase Family | Integrated Approach | Combines advantages of both methods for selectivity challenges [20] | Develop models for multiple kinases to identify selectivity features |

| Scaffold Hopping for Patent Expansion | Ligand-Based | Identifies novel chemotypes maintaining key interactions [5] | Use less restrictive models to maximize structural diversity |

| Allosteric or Novel Site Inhibitor Discovery | Structure-Based | Reveals unique interaction patterns in unconventional sites [27] | Focus on unique subpockets distinct from conserved ATP site |

The strategic selection between ligand-based and structure-based pharmacophore modeling is pivotal for efficient kinase inhibitor discovery. Ligand-based approaches provide a powerful solution when structural data is limited but knowledge of active compounds exists, while structure-based methods offer atomic-level insights when high-quality protein structures are available. For challenging kinase targets, particularly those requiring high selectivity across conserved kinase families, an integrated approach that combines both methodologies may offer the most robust path to identifying novel, potent inhibitors. As computational methods continue to advance, including machine learning acceleration for virtual screening [6], pharmacophore modeling remains an indispensable component of the modern kinase drug discovery toolkit.

Leveraging Publicly Available Kinase Structures and Bioactivity Data (e.g., PDB, ChEMBL) for Model Development

Kinases represent a prime target family in drug discovery for diseases such as cancer and inflammatory disorders [30]. The high conservation of their binding sites, particularly the ATP-binding pocket, presents a challenge for achieving selective inhibition and underscores the risk of promiscuous binding and off-target effects [30] [31]. Publicly available resources, including the Protein Data Bank (PDB) for structural data and ChEMBL for bioactivity data, provide a foundational data source for computational approaches like pharmacophore modeling and machine learning. These methods are crucial for navigating the kinase inhibitor chemical space in a cost- and time-effective manner [5] [6]. This application note details protocols for developing robust computational models within the context of a pharmacophore-based virtual screening protocol for kinase inhibitor research.

A successful modeling workflow hinges on the integration of data from multiple public resources. The table below summarizes the core databases utilized in kinase inhibitor discovery.

Table 1: Key Public Data Resources for Kinase Research

| Resource Name | Data Type | Key Features & Utility | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| RCSB PDB | Protein-ligand structures | Primary source for 3D structures of kinase-ligand complexes; essential for structure-based pharmacophore modeling and molecular docking. | [5] [6] |

| ChEMBL | Bioactivity data | Manually curated database of bioactive molecules with quantitative properties (e.g., IC₅₀, Kᵢ); vital for ligand-based modeling and model validation. | [6] [32] |

| KLIFS | Kinase-focused structures | Specialized database providing curated structural data of kinase ligand-binding sites, including DFG and αC-helix conformations. | [30] [33] |

| UniProt | Protein sequence & function | Provides comprehensive information on kinase sequences, functional domains, and annotated mutations. | [30] |

Kinase-Specific Structural Concepts

Kinase structures are highly dynamic. Successful model development requires attention to key conformational states:

- DFG Motif: The Asp-Phe-Gly motif can adopt "DFG-in" (active) or "DFG-out" (inactive) conformations, which is a primary classifier for kinase inhibitor types (e.g., Type I vs. Type II) [34].

- αC-Helix: This helix can also adopt "in" or "out" conformations, which, combined with the DFG state, defines the kinase's catalytic status and the shape of the binding pocket [34].

- Hinge Region: A critical area for forming hydrogen bonds with ATP-competitive inhibitors [30].

Researchers should note that AI-based structural prediction tools like AlphaFold2 have a demonstrated bias toward generating structures in the active, DFG-in conformation prevalent in the PDB. Using lower multiple sequence alignment (MSA) depths during AlphaFold2 prediction can help explore a wider range of inactive conformations for drug discovery [34].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

The following diagram illustrates a comprehensive protocol integrating public data and computational models for kinase inhibitor discovery.

Diagram 1: Integrated kinase inhibitor discovery workflow.

Protocol 1: Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

This protocol generates a pharmacophore model directly from the 3D structure of a kinase target.

Procedure:

Protein Structure Preparation

- Obtain the 3D structure of your kinase target of interest from the PDB (e.g., PDB ID: 2Z5Y for MAO-A) [6]. If an experimental structure is unavailable, a high-quality model from AlphaFold2 (with caution for conformational bias) or a homology model can be used [5] [34].

- Prepare the protein structure using standard molecular modeling software (e.g., Maestro's Protein Preparation Wizard). This involves adding hydrogen atoms, assigning bond orders, correcting protonation states (e.g., using PropKa at pH 7), and optimizing hydrogen-bonding networks [35].

- Perform energy minimization using a force field such as OPLS_2005 to relieve steric clashes [35].

Binding Site Detection and Analysis

- Define the ligand-binding site. If the structure is a complex with a ligand, the binding site is defined by the co-crystallized ligand. For apo structures, use tools like GRID or LUDI to identify potential binding pockets by analyzing the protein surface for regions with favorable interaction energies [5].

- For kinases, specialized resources like KLIFS provide a standardized definition of the binding pocket, which includes 85 key residues [30] [31].

Pharmacophore Feature Generation

- Analyze the prepared binding site to generate a set of chemical features that a ligand must possess to bind effectively. Standard features include [5]:

- Hydrogen Bond Donor (HBD)

- Hydrogen Bond Acceptor (HBA)

- Hydrophobic (H)

- Positively/Negatively Ionizable (PI/NI)

- Aromatic Ring (AR)

- The features can be derived from interactions made by a bound ligand (in a holo structure) or from complementary interaction points calculated for the protein alone (in an apo structure) [5].

- To increase model selectivity, incorporate Exclusion Volumes (XVOL). These are spheres placed in the 3D space where the presence of ligand atoms would cause steric clashes with the protein, thereby defining the shape of the binding cavity [5].

- Analyze the prepared binding site to generate a set of chemical features that a ligand must possess to bind effectively. Standard features include [5]:

Model Refinement and Validation

- Not all generated features are equally important. Manually select features that are critical for bioactivity, such as those involved in conserved interactions (e.g., hinge region hydrogen bonds in kinases) or interactions with key residues identified from mutagenesis studies [5].

- Validate the model by assessing its ability to retrieve known active compounds from a database of decoys before proceeding to virtual screening.

Protocol 2: Developing a Machine Learning Bioactivity Predictor

This protocol leverages large-scale bioactivity data from ChEMBL to train a model that predicts compound-kinase interactions, dramatically accelerating virtual screening [6] [32].

Procedure:

Data Curation from ChEMBL

- Download kinase bioactivity data from ChEMBL (e.g., Ki, IC₅₀ values for MAO-A and MAO-B) [6].

- Filter the data to ensure quality. Retain only compounds with definitive activity values (e.g., IC₅₀). Exclude compounds with molecular weight >700 Da and highly flexible structures to reduce noise [6].

- Convert IC₅₀ values to pIC₅₀ (pIC₅₀ = -log₁₀(IC₅₀)) to create a more normally distributed value for modeling [6].

Data Splitting Strategy

- Split the dataset into training, validation, and test sets (e.g., 70/15/15). To rigorously test the model's ability to generalize to novel chemical scaffolds, use Bemis-Murcko scaffold-based splitting. This ensures that compounds in the training and test sets are structurally distinct, providing a more realistic performance estimate for prospective screening [6].

Feature Generation (Featurization)

- Compound Representation: Encode compounds using molecular fingerprints such as ECFP4 (Extended Connectivity Fingerprints) or other descriptors (e.g., RDKit fingerprints) [32].

- Kinase Representation: Encode kinases using features derived from their amino acid sequence. This can include the 85-residue binding pocket sequence from KLIFS or embeddings from a pretrained protein language model like ProtBert [32].

Model Training and Ensemble Construction

- Train multiple machine learning algorithms, which may include Random Forest, Kernel Ridge Regression, or deep learning methods like ConPLex [32].

- Construct an ensemble model that combines predictions from multiple individual models (e.g., using different fingerprint types or algorithms). This ensemble approach reduces prediction errors and delivers more precise and robust activity predictions [6].

Model Validation and Application

- Evaluate the model on the held-out test set using metrics like Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) and Spearman rank correlation.

- Use the trained model to predict the activity of millions of compounds from commercial databases (e.g., ZINC), prioritizing compounds with predicted high activity for further experimental testing [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| RCSB PDB & KLIFS | Database | Provides validated 3D structures of kinase targets for structure-based modeling and analysis of binding site motifs. |

| ChEMBL | Database | Supplies curated bioactivity data for training and validating ligand-based and machine learning models. |

| UniChem | Web Service | Cross-references compound identifiers between databases (e.g., from ChEMBL ID to PDB ligand ID) [36]. |

| AlphaFold2 DB | Database | Offers protein structure predictions for targets lacking experimental structures; requires conformational bias assessment [34]. |

| ECFP4 Fingerprints | Computational Descriptor | Encodes molecular structure for machine learning models, enabling the prediction of bioactivity from chemical features [32]. |

| Smina | Software | Performs molecular docking to generate binding poses and scores for virtual screening; can be used as a source of data for ML model training [6]. |

| Schrödinger Phase | Software | Facilitates the development and application of structure-based and ligand-based pharmacophore models for virtual screening [35]. |

Building and Executing Your Screening Protocol: A Step-by-Step Workflow

Pharmacophore modeling represents a foundational step in structure-based drug discovery, providing an abstract definition of the structural and chemical features essential for a small molecule to bind a biological target. Within kinase drug discovery, this approach is particularly valuable for identifying novel chemotypes and addressing challenges of selectivity and resistance. This protocol details the generation and validation of pharmacophore models targeted specifically at kinase binding pockets, serving as the critical first step in a comprehensive pharmacophore-based virtual screening workflow for kinase inhibitor identification.

Key Pharmacophore Features for Kinase Binding Pockets

Kinase binding pockets share conserved structural elements that inform pharmacophore feature definition. The table below summarizes the critical pharmacophore features relevant for kinase inhibitor design, particularly for Type II inhibitors that target the inactive (DFG-out) conformation.

Table 1: Essential Pharmacophore Features for Kinase Binding Pockets

| Feature Type | Structural Role in Kinase Binding | Target Kinase Residues |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Bond Acceptor | Binds to hinge region backbone amide | Cys919 (VEGFR-2), Ala539 (FGFR-1), Cys531 (BRAF) [37] |

| Hydrogen Bond Donor | Binds to hinge region backbone carbonyl | Gate area and hinge region [37] |

| Hydrophobic Group | Interacts with hydrophobic back pocket | Phe1047 (VEGFR-2), Phe537 (FGFR-1), Phe583 (BRAF) [37] |

| Aromatic Ring | Engages in π-π or cation-π interactions | Often with Phe residues in the DFG motif [38] |

| Negative Ionizable | Interacts with cationic Lys/Glu pair | Glu885 (VEGFR-2), Glu562 (FGFR-1) [39] [37] |

| Hydrophobic Atom | Occupies hydrophobic regions I/II | Val916, Leu1035 (VEGFR-2), Ala564, Leu484 (FGFR-1) [38] [40] |

Methodological Approaches

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

Structure-based pharmacophore models are derived from the 3D structure of the target kinase, typically in complex with an inhibitor.

Protocol: Structure-Based Model Generation using MOE

- Protein Preparation: Obtain the crystal structure of the kinase-inhibitor complex from the PDB (e.g., PDB ID: 3E8D for Akt2). Remove water molecules and co-crystallized ligands. Add hydrogen atoms and assign correct protonation states at pH 7.4.

- Binding Site Analysis: Define the binding site using the co-crystallized ligand as a reference, creating a sphere within a 7 Å radius from the original ligand [40].

- Feature Generation: Use the "Interaction Generation" protocol to map potential interaction points (hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic patches, aromatic centers, ionic groups) between the protein and a putative ligand [38] [40].

- Feature Selection and Clustering: Manually edit and cluster the generated features to eliminate redundancies. Retain only the features with catalytic importance. A typical model may comprise 6-7 key features [40].

- Exclusion Volume Addition: Define exclusion volumes (spheres) around protein atoms in the binding site to represent steric constraints, ensuring generated molecules have compatible shapes [40].

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

When structural data is limited or to incorporate known structure-activity relationships (SAR), ligand-based models are constructed from a set of active compounds.

Protocol: Ligand-Based Model Generation with Catalyst/HipHop

- Training Set Compilation: Select 4-6 known kinase inhibitors with activity spanning a wide potency range (e.g., nanomolar to micromolar). Assign priority levels based on potency [39].

- Conformational Analysis: For each training set compound, generate a representative set of low-energy conformations using the "Generate Conformations" protocol (Best Energy Threshold: 20 kcal/mol) [40].

- Hypothesis Generation: Use the HipHopRefine algorithm to identify common chemical features from the aligned conformations of the most active compounds [39].

- Model Refinement: Use medium- and low-activity compounds to validate and refine the hypothesis, discarding models that assign high fit values to inactive compounds [39].

Emerging Methods: Water-Based and AI-Enhanced Pharmacophores

Recent advances incorporate explicit water molecules and machine learning to improve model accuracy and novelty.

- Water-Based Pharmacophores: Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of water molecules in the empty, solvated kinase binding pocket are performed. The conserved hydration sites are then translated into complementary pharmacophore features (e.g., hydrogen bond donors/acceptors), offering a ligand-free strategy for novel chemotype identification [41].

- AI-Enhanced Models: Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) can be applied to ensembles of 3D pharmacophores to enhance virtual kinase profiling. This approach integrates multiple protein-ligand interaction patterns, significantly improving prediction accuracy for kinase inhibitor activity and selectivity [42].

Model Validation Protocols

Rigorous validation is crucial to ensure the model's utility for virtual screening.

Table 2: Pharmacophore Model Validation Methods and Metrics

| Validation Method | Procedure | Interpretation of Results |

|---|---|---|

| Decoy Set Validation | Screen a database of known actives and decoys. Calculate Enrichment Factor (EF) and Goodness of Hit Score (GH). | EF > 10 and GH > 0.7 indicate a high-quality model. A GH of 0.72 is considered very good [40]. |

| Test Set Validation | Challenge the model with a set of known active inhibitors not used in training and confirmed inactive compounds. | The model should retrieve a high percentage of actives (e.g., 20-100%) and correctly reject most inactives [39] [40]. |

| Fischer's Validation | Assess the statistical significance of the hypothesis against a null model that assumes no discriminating power. | A confidence level of >95% indicates the model did not arise by chance [40]. |

Validation Protocol: Decoy Set Testing

- Prepare a Decoy Set: Compile a database of ~2000 molecules, including ~20 known active kinase inhibitors and 1980 pharmaceutically relevant but presumably inactive decoy molecules with similar physical properties [40].

- Perform Virtual Screening: Use the pharmacophore model as a 3D query to screen the decoy set.

- Calculate Metrics:

- Enrichment Factor (EF):

EF = (Ht / Ht) / (A / D), whereHtis the number of actives found,Hais the number of actives in the database, andDis the total molecules in the database [40]. - Goodness of Hit Score (GH):

GH = [ (Ht / (4 * Ha * D)) ^ (1/2) ] * [ ( (Ha - Ht) / (Ha - Ht) ) + 1 ]. A score closer to 1.0 is ideal [40].

- Enrichment Factor (EF):

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Software for Pharmacophore Modeling

| Item Name | Function/Application | Examples/References |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) | Software for structure-based pharmacophore generation, molecular docking, and simulations. | Used for creating complex-based pharmacophore models and analyzing binding interactions [38]. |

| Accelrys Discovery Studio | Platform for generating and validating 3D-QSAR pharmacophore models and performing virtual screening. | Employed for hypothesis generation using the HipHop algorithm and Fischer's validation [40]. |

| Pharmit Server | Online tool for ligand-based virtual screening using pharmacophore queries. | Used for screening chemical databases based on pharmacophoric features of a co-crystal ligand [43]. |

| RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Repository for 3D structural data of proteins and nucleic acids, essential for structure-based design. | Source of kinase crystal structures (e.g., 3F3V for Src kinase, 7AEI for EGFR) [38] [43]. |

| Kinase-Targeted Compound Libraries | Curated sets of known kinase inhibitors and drug-like molecules for validation and screening. | Databases like ZINC, PubChem, ChemBridge, NCI, and commercial libraries from Enamine and ChemDiv [12] [43]. |

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) Models | Machine learning architecture for enhancing kinase profiling accuracy using 3D pharmacophore ensembles. | Applied to a curated database of 75 kinases to predict inhibitor selectivity [42]. |

Workflow Visualization

Kinase Pharmacophore Modeling Workflow

Application in Kinase Drug Discovery

Validated pharmacophore models are deployed as 3D search queries to screen large chemical databases (e.g., ZINC, PubChem) [43]. This virtual screening process efficiently prioritizes compounds that match the essential feature map of the kinase binding pocket. Successful applications have identified novel, potent inhibitors for diverse kinase targets, including:

- c-Src kinase: A pharmacophore-based high-throughput virtual screening of 500,000 compounds identified specific inhibitors with anticancer activity and kinase IC~50~ values comparable to the control drug bosutinib [12].

- VEGFR-2, FGFR-1, and BRAF: A multi-kinase pharmacophore model facilitated the discovery of a benzimidazole-based compound (8u) with potent inhibitory activity (IC~50~ values of 0.93 µM, 3.74 µM, and 0.25 µM, respectively) and lethal effects on various NCI cancer cell lines [37].

- PLK1: The TransPharmer generative model, guided by pharmacophore fingerprints, designed a novel inhibitor (IIP0943) with 5.1 nM potency and a new 4-(benzo[b]thiophen-7-yloxy)pyrimidine scaffold, demonstrating successful scaffold hopping [44].