Bridging the Gap: A Practical Guide to Validating MD Simulations with Experimental Binding Data in Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on validating Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations against experimental binding data.

Bridging the Gap: A Practical Guide to Validating MD Simulations with Experimental Binding Data in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on validating Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations against experimental binding data. It covers the foundational importance of validation for accurate and reproducible results, explores a spectrum of methodological approaches from docking to free energy calculations, addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and offers a comparative analysis of validation techniques. By synthesizing current best practices and emerging trends, this guide aims to enhance the reliability of MD simulations, thereby streamlining the drug discovery pipeline and increasing confidence in computational predictions.

Why Validation is Non-Negotiable: The Critical Role of Experimentation in Trusting Your MD Simulations

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation serves as a "virtual microscope" for computational structural biology, providing atomistic details into the dynamic motions of proteins and other biomolecules that often remain hidden from traditional experimental techniques [1]. Unlike static structural representations, MD tracks how molecular systems evolve over time by applying principles of classical physics, thereby offering a dynamic view of biological macromolecules in flexible environments that more closely resemble realistic conditions [2]. This capability has established MD as an indispensable tool in drug discovery, where it enhances understanding of how drug candidates interact with target proteins, improves predictions of binding modes, stability, and affinity, and can reveal hidden or transient binding sites that may serve as novel therapeutic targets [2].

However, the predictive capabilities of MD face two fundamental challenges: the sampling problem, where lengthy simulations may be required to accurately describe certain dynamical properties, and the accuracy problem, where insufficient mathematical descriptions of physical and chemical forces can yield biologically meaningless results [1]. As MD simulations see increased usage by non-specialists, understanding these limitations and establishing robust validation protocols against experimental data becomes increasingly critical for the field [1]. This review examines the current state of MD methodologies, their performance across different software implementations, validation frameworks, and the emerging synergies with machine learning that together are pushing the boundaries of what this "virtual microscope" can reveal.

Performance Landscape of MD Software Packages

The MD software ecosystem comprises multiple packages, each with distinct strengths, optimization strategies, and performance characteristics. Understanding these differences is essential for researchers to select appropriate tools and maximize computational efficiency.

Performance Metrics and Benchmarking

Benchmarking studies reveal significant variation in performance across MD packages. GROMACS consistently demonstrates exceptional performance for CPU-based simulations, particularly when optimized with appropriate core counts [3]. The AMBER package offers specialized GPU-accelerated versions (pmemd.cuda) that deliver competitive performance for single GPU simulations, though its multi-GPU capabilities are primarily beneficial for enhanced sampling methods like replica exchange rather than single simulations [3]. NAMD provides robust multi-GPU support, making it suitable for large-scale parallel simulations [3].

Efficient resource allocation is crucial for optimal performance. Importantly, submitting simulations with more CPUs does not necessarily guarantee faster performance; in some cases, excessive parallelization can actually degrade performance [3]. Assessing CPU efficiency requires comparing actual speedup against theoretically optimal scaling based on single-CPU performance [3].

Table 1: Molecular Dynamics Software Performance Characteristics

| Software | Optimization Strength | GPU Support | Key Performance Features | Typical Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | Excellent CPU optimization | Single & Multi-GPU | High parallel efficiency, Fastest on CPUs | Large-scale biomolecular simulations |

| AMBER | Good CPU, Excellent GPU | Primarily Single-GPU | Specialized pmemd.cuda for GPUs |

Protein-ligand systems, NMR refinement |

| NAMD | Good parallel scaling | Multi-GPU | Strong scaling across multiple nodes | Very large systems (membranes, viral capsids) |

| OpenMM | Python-driven flexibility | Multi-GPU | High GPU utilization, Easy prototyping | Method development, Custom simulations |

Performance optimization strategies include hydrogen mass repartitioning, which allows increasing time steps to 4 fs by increasing hydrogen masses and decreasing masses of bonded atoms, maintaining total mass while improving simulation efficiency [3]. Tools like parmed in AMBER automate this process, potentially significantly accelerating simulations without sacrificing accuracy [3].

Benchmarking Tools and Methodologies

Specialized tools have emerged to streamline MD benchmarking. MDBenchmark provides a standardized approach to generate, run, and analyze benchmarks across varying computational resources [4]. This toolkit automatically creates benchmarks for different node configurations, submits jobs to queuing systems, and analyzes performance results with CSV export and plotting capabilities [4].

The benchmarking process typically involves:

- System preparation using

gmx pdb2gmxor equivalent tools - Benchmark generation across node configurations (e.g., 1-5 nodes)

- Job submission to cluster schedulers

- Performance analysis of ns/day and resource utilization [4]

Recent benchmarking frameworks have introduced more sophisticated evaluation metrics. The standardized benchmark using Weighted Ensemble sampling evaluates MD methods across 19 different metrics including structural fidelity, slow-mode accuracy, and statistical consistency [2]. This comprehensive approach enables more meaningful comparisons between simulation methods.

Experimental Validation of MD Simulations

Methodologies for Validating Simulation Results

Validation against experimental data remains the gold standard for assessing MD simulation accuracy. Multiple studies have systematically compared simulation results from different packages and force fields against experimental observables.

A comprehensive study evaluating four MD packages (AMBER, GROMACS, NAMD, and ilmm) with three force fields (AMBER ff99SB-ILDN, CHARMM36, and Levitt et al.) demonstrated that while most packages reproduced experimental observables equally well at room temperature, subtle differences emerged in underlying conformational distributions and sampling extent [1]. These differences became more pronounced when simulating larger amplitude motions, such as thermal unfolding, with some packages failing to allow proper unfolding at high temperatures or producing results inconsistent with experiment [1].

Table 2: Experimental Techniques for MD Validation

| Experimental Method | Validated MD Properties | Key Limitations | Complementary MD Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| NMR Spectroscopy | Chemical shifts, J-couplings, Relaxation rates | Ensemble averaging obscures individual states | Atomic-level trajectories, Time-dependent fluctuations |

| Small-Angle X-Ray Scattering (SAXS) | Radius of gyration, Molecular shape | Low resolution, Ensemble averaging | 3D structural ensembles, Conformational diversity |

| X-ray Crystallography | High-resolution structure | Static picture, Crystal packing artifacts | Dynamic motions, Sidechain rearrangements |

| Circular Dichroism (CD) | Secondary structure content | Limited structural resolution | Secondary structure stability, Thermal unfolding pathways |

Critical validation workflows involve comparing multiple simulation replicates against diverse experimental datasets. For instance, 200 ns simulations performed in triplicate using different packages revealed that while overall agreement with experimental data was good, the extent of conformational sampling varied significantly between force fields [1]. This underscores the importance of ensemble validation rather than single-metric comparisons.

Standardized Validation Frameworks

The development of standardized benchmarks represents a significant advancement in MD validation. The weighted ensemble (WE) sampling framework using WESTPA enables efficient exploration of protein conformational space and facilitates direct comparisons between simulation approaches [2]. This modular benchmark evaluates methods across multiple dimensions:

- Global properties: TICA energy landscapes, contact map differences, radius of gyration distributions

- Local properties: Bond lengths, angles, and dihedrals

- Quantitative divergence metrics: Wasserstein-1 and Kullback-Leibler divergences [2]

The framework includes a dataset of nine diverse proteins ranging from 10 to 224 residues, spanning various folding complexities and topologies, providing a common ground-truth for method evaluation [2]. Each protein has been extensively simulated with multiple starting points to ensure comprehensive conformational coverage.

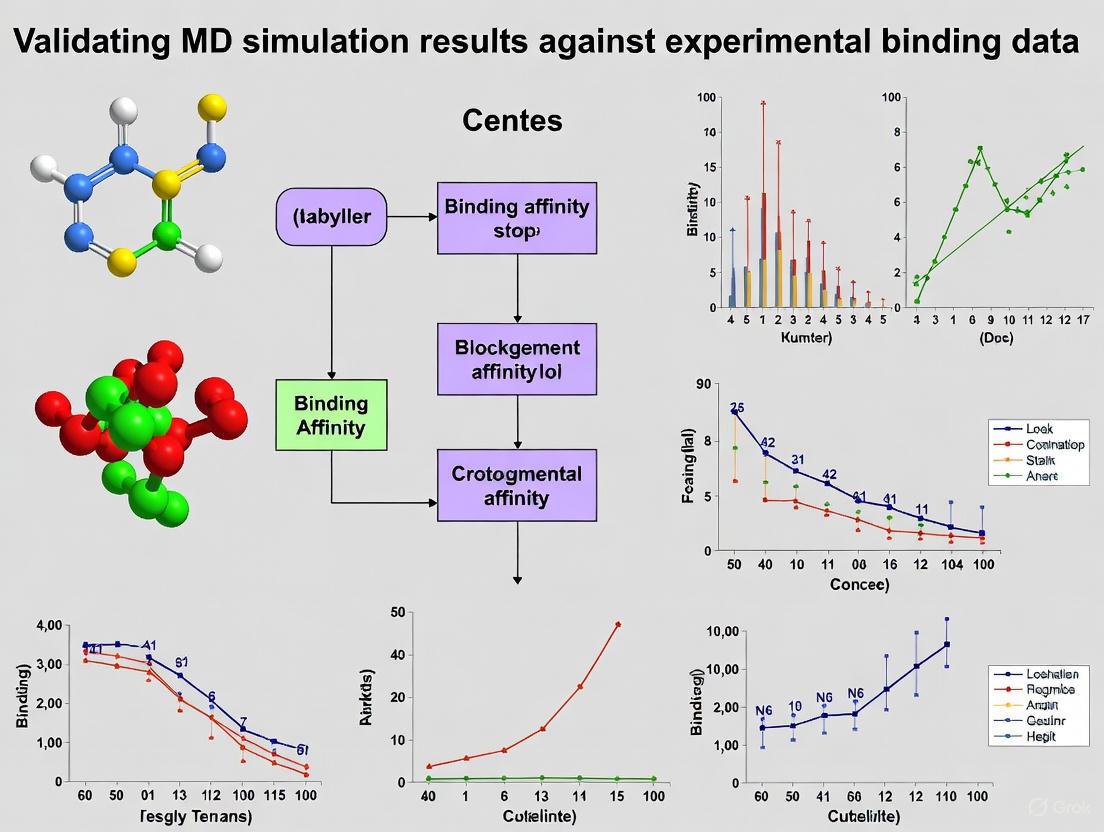

MD Validation Workflow: Integrating experimental data with simulation methodologies.

Power and Limitations in Sampling Conformational Landscapes

Challenges with Intrinsically Disordered Proteins

MD simulations face particular challenges when applied to intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs), which exist as dynamic ensembles rather than stable tertiary structures [5]. The structural plasticity of IDPs enables functional versatility but presents significant challenges for traditional MD approaches due to:

- Vast conformational space: IDPs explore extensive conformational landscapes requiring microsecond to millisecond timescales for adequate sampling [5]

- Rare transient states: Biologically relevant but transient conformations may be missed even with extensive simulation times [5]

- Force field limitations: Traditional force fields parameterized for folded proteins may not accurately capture IDP energetics [5]

Specialized MD techniques like Gaussian accelerated MD (GaMD) have shown promise for IDPs by capturing rare events such as proline isomerization in the ArkA system, revealing conformational switching that regulates binding to biological partners [5]. These advanced sampling techniques help bridge the timescale gap between simulation and biologically relevant processes.

Machine Learning and Enhanced Sampling Approaches

Artificial intelligence methods offer transformative alternatives for sampling complex conformational landscapes. Deep learning approaches leverage large-scale datasets to learn complex, non-linear, sequence-to-structure relationships, enabling efficient modeling of conformational ensembles without traditional physics-based constraints [5]. These approaches have demonstrated capabilities to outperform MD in generating diverse ensembles with comparable accuracy, particularly for IDPs [5].

Enhanced sampling strategies address timescale limitations through various approaches:

- Weighted Ensemble (WE): Runs multiple replicas with resampling based on progress coordinates to capture rare events [2]

- Metadynamics: Biases the energy landscape to escape local minima [2]

- Coarse-graining (CG): Reduces molecular complexity by grouping atoms into beads, enabling longer timescales [2]

Machine-learned molecular dynamics, particularly graph neural networks like SchNet, DimeNet, and PhysNet, learn energy landscapes and forces directly from data, showing promise for extending accessible timescales while maintaining physical consistency [2].

Synergy with Experimental Binding Data in Drug Discovery

Large-Scale MD Datasets for Binding Affinity Prediction

The integration of MD with experimental binding data has accelerated through large-scale datasets designed for machine learning applications. The PLAS-20k dataset represents a significant advancement, with 97,500 independent simulations across 19,500 protein-ligand complexes [6]. This extensive dataset enables:

- Correlation with experimental values: MD-based binding affinities show better correlation with experiment than docking scores [6]

- Classification of binders: Improved differentiation between strong and weak binders compared to docking [6]

- MMPBSA calculations: Binding affinities computed using Molecular Mechanics/Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area methods [6]

The dataset curation process involves rigorous preparation: protein structure completion, protonation at physiological pH, parameterization using AMBER ff14SB for proteins and GAFF2 for ligands, solvation in TIP3P water boxes, and production simulations using OpenMM [6]. Each complex undergoes five independent simulations with binding affinities averaged across trajectories.

Table 3: Research Toolkit for MD-Based Drug Discovery

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| PLAS-20k Dataset | MD-based binding affinities for 19.5k complexes | ML model training, Binding affinity prediction |

| MDBenchmark | Performance optimization across compute resources | Benchmarking, Resource allocation |

| StreaMD | Automated pipeline for high-throughput MD | Large-scale virtual screening |

| OpenMM | Flexible MD framework with GPU acceleration | Custom simulation protocols, Method development |

| WESTPA | Weighted ensemble sampling | Enhanced sampling of rare events |

| AMBER ff14SB | Protein force field | General protein simulations |

| GAFF2 | Small molecule force field | Ligand parameterization |

| MMPBSA/MMGBSA | Binding free energy calculations | Protein-ligand affinity estimation |

Automation Tools for High-Throughput Simulations

Automation tools have emerged to streamline MD workflows, making sophisticated simulations more accessible to non-specialists. StreaMD provides a Python-based toolkit that automates preparation, execution, and analysis of MD simulations across distributed computing environments [7]. Key features include:

- Minimal user intervention: Automated processing of proteins, ligands, and cofactors

- Support for complex systems: Cofactors, metal ions, and specialized ligands

- Integration with binding energy calculations: MM-GBSA/PBSA and interaction fingerprints

- Distributed computing: Dask-based parallelization across multiple servers [7]

Similarly, MDBenchmark simplifies performance optimization by automatically generating and testing configurations across different node counts, enabling researchers to identify optimal resource allocation for their specific systems [4].

MD-Driven Drug Discovery Pipeline: Integrating simulations with experimental binding data.

Molecular dynamics simulations have transformed from niche computational tools to essential "virtual microscopes" providing unprecedented insights into biomolecular dynamics. The power of MD lies in its ability to reveal atomic-level details and temporal evolution inaccessible to most experimental techniques, while its limitations primarily revolve around sampling completeness and force field accuracy.

The future of MD rests on several developing trends: continued refinement of force fields through integration with experimental data, increased utilization of machine learning to enhance sampling and accuracy, development of standardized benchmarking frameworks, and tighter integration with experimental structural biology in iterative validation cycles. Tools like MDBenchmark, StreaMD, and weighted ensemble sampling represent steps toward more reproducible, accessible, and reliable simulations.

As MD methodologies continue evolving alongside computational resources and machine learning approaches, the virtual microscope will provide increasingly sharp focus on biological processes, further bridging the gap between computational prediction and experimental reality in drug discovery and structural biology.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations provide atomistic insight into biological processes and material behaviors, but their predictive power is constrained by two fundamental challenges: the accuracy of the force fields and the ability to sample relevant conformational spaces. This guide objectively compares the performance of different force fields and sampling methods, validating results against experimental data to inform researchers in drug development and related fields.

Force Field Performance Across Systems

The choice of force field is critical, as its empirical parameters directly determine the accuracy of simulated physical properties. Performance varies significantly across different types of systems.

Biomolecular Force Fields and Secondary Structure

Table 1: Comparison of Biomolecular Force Field Performance on a β-Hairpin Peptide

| Force Field | Able to Fold Native β-Hairpin at 310 K? | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Amber ff99SB-ILDN | Yes | Modification to side-chain torsion potentials of Isoleucine, Leucine, Aspartate, Asparagine [8] |

| Amber ff99SB* | Yes | Modification to backbone dihedral potentials [8] |

| Amber ff03* | Yes | Modification to backbone dihedral potentials [8] |

| GROMOS96 43a1p | Yes | United-atom force field; includes phosphorylated amino acid parameters [8] |

| GROMOS96 53a6 | Yes | United-atom force field [8] |

| CHARMM27 | Partially (at elevated temperatures) | Includes CMAP correction for backbone torsion [8] |

| OPLS-AA/L | No | Updated dihedral parameters from original distribution [8] |

A comprehensive study of 10 force fields simulating a 16-residue β-hairpin peptide from Nrf2 revealed significant differences. Despite identical starting structures and simulation parameters, outcomes varied both between force fields and between replicates of the same force field [8].

Force Fields for Liquid and Membrane Systems

Table 2: Performance of All-Atom Force Fields for Diisopropyl Ether (DIPE)

| Force Field | Density Prediction | Shear Viscosity Prediction | Suitability for Liquid Membranes |

|---|---|---|---|

| GAFF | Overestimated by ~3-5% [9] | Overestimated by ~60-130% [9] | Low |

| OPLS-AA/CM1A | Overestimated by ~3-5% [9] | Overestimated by ~60-130% [9] | Low |

| COMPASS | Accurate [9] | Accurate [9] | Medium |

| CHARMM36 | Accurate [9] | Accurate [9] | High (Recommended) |

For liquid ethers and membrane systems, force fields show clear performance differences. CHARMM36 and COMPASS accurately reproduced density and shear viscosity of Diisopropyl Ether (DIPE), while GAFF and OPLS-AA/CM1A showed significant overestimations [9]. CHARMM36 was concluded to be the most suitable for modeling ether-based liquid membranes, also accurately estimating mutual solubility with water and interfacial tension [9].

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Robust validation requires comparing simulation results with experimentally measurable quantities. The following protocols are considered best practice.

Protocol: Validating Against Experimental Structural and Mechanical Data

This protocol uses a fused data learning strategy to create highly accurate models by combining data from both simulations and experiments [10].

- Step 1: Generate Initial Training Data via DFT. Perform Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations on target system to obtain reference energies, forces, and virial stress for diverse atomic configurations (e.g., equilibrated, strained, and randomly perturbed structures) [10].

- Step 2: Pre-train a Machine Learning Potential. Train a Graph Neural Network (GNN) or other Machine Learning Force Field exclusively on the DFT data. This serves as the initial model [10].

- Step 3: Integrate Experimental Data. Incorporate experimentally measured properties (e.g., temperature-dependent elastic constants and lattice parameters of hcp titanium) into the training process. Use a method like Differentiable Trajectory Reweighting (DiffTRe) to compute gradients through the simulation without backpropagation through the entire trajectory [10].

- Step 4: Concurrent Training. Alternate optimization between the DFT data and experimental data trainers. The final model should minimize errors against the quantum mechanical data while simultaneously reproducing macroscopic experimental observables [10].

Protocol: Validating IDR Conformational Ensembles

Intrinsically Disordered Regions (IDRs) lack a fixed structure, so validation must target the ensemble's statistical properties [11].

- Step 1: Generate Conformational Ensemble. Use enhanced sampling methods like Replica Exchange Solute Tempering (REST) to sample the IDR's conformational space. Standard MD may require prohibitively long simulations to achieve convergence [11].

- Step 2: Compute Experimental Observables. Calculate ensemble-averaged experimental observables from the simulation trajectories, including:

- Step 3: Compare with Experimental Data. Quantify the agreement between computed and experimentally measured observables. The ensemble is considered valid if it reproduces these independent experimental measurements within error margins [11].

Diagram 1: Workflow for validating conformational ensembles of Intrinsically Disordered Regions (IDRs) against experimental data [11].

The Sampling Challenge and Advanced Solutions

Insufficient sampling is a major source of inaccuracy, especially for calculating binding affinities or exploring disordered landscapes.

The Conformational Sampling Problem in IDRs

For a 20-residue IDR with each residue coarsely occupying 3 conformational states, the total number of molecular conformations is ~3^20 (approximately 3.5 billion) [11]. The time required to visit each conformation just once can be on the order of milliseconds, which is computationally prohibitive. This necessitates dimensionality reduction by validating against ensemble-averaged experimental observables [11].

Advanced Sampling for Binding Affinity Estimation

Accurate binding affinity (ΔG) prediction requires sampling the bound, unbound, and transition states. Methods vary in rigor and computational cost [12].

- End-State Methods (MM/PBSA, MM/GBSA): These calculate energies from endpoint simulations (typically bound state) using implicit solvent. They are relatively fast but often neglect conformational changes and entropic contributions, leading to variable accuracy [12].

- Alchemical Methods (Free Energy Perturbation - FEP): These use non-physical pathways to "annihilate" and "de-couple" the ligand in the bound and unbound states. While rigorous, they can be sensitive to the chosen pathway and require careful handling of restraints to define the standard state [12].

- Path Sampling Methods (Umbrella Sampling - US): These use a biasing potential along a physical reaction coordinate (e.g., ligand-protein distance) to force unbinding. A potential of mean force (PMF) is reconstructed, from which ΔG is derived. Incomplete sampling of other degrees of freedom (e.g., ligand orientation) can be mitigated by adding restraints on orientation (Ω) and root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of the ligand and protein, greatly improving convergence and accuracy [12].

Diagram 2: Hierarchy of binding affinity methods based on sampling rigor and convergence, from brute-force MD to advanced restrained path sampling [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Software and Force Fields for MD Validation

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Key Application in Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| AMBER | MD Software Package | Simulate biomolecular kinetics and thermodynamics | Testing force field performance against NMR data and thermal unfolding [1] |

| GROMACS | MD Software Package | High-performance molecular dynamics | Benchmarking against experimental room-temperature observables [1] |

| CHARMM36 | All-Atom Force Field | Empirical energy function for molecules | Accurate modeling of liquid membranes and phospholipids [9] |

| Amber ff99SB-ILDN | Biomolecular Force Field | Parameter set for proteins and nucleic acids | Folding of secondary structures like β-hairpins [8] |

| Dynaformer | Deep Learning Model | Predict binding affinity from MD trajectories | Leveraging thermodynamic ensembles for improved virtual screening [13] |

| DiffTRe | Training Algorithm | Differentiable Trajectory Reweighting | Fusing experimental data directly into ML force field training [10] |

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have emerged as powerful computational microscopes, predicting the dynamic behavior of biological complexes at an atomistic level. However, their predictive power and accuracy in drug discovery are contingent upon rigorous validation against experimental data. The integration of structural techniques (crystallography and cryo-electron microscopy) with quantitative binding affinity measurements (isothermal titration calorimetry and surface plasmon resonance) creates a robust framework for validating MD simulations. This multi-faceted approach is crucial because computational methods can produce distinct pathways and conformational ensembles that may all seem equally plausible without experimental grounding [1]. For instance, simulations of villin headpiece demonstrated that while folding rates and native state structures agreed with experiment, the folding pathways and denatured state properties were force-field dependent [1]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of key experimental techniques used for MD validation, offering protocols and data integration strategies to enhance the reliability of computational predictions in drug development.

Comparative Analysis of Key Experimental Techniques

Technical Specifications and Performance Metrics

Table 1: Comparison of key experimental techniques for MD simulation validation

| Technique | Structural Resolution | Binding Affinity Range | Sample Consumption | Throughput | Key Output Parameters | Primary Applications in MD Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X-ray Crystallography | Atomic (1-3 Å) | N/A | Medium (mg) | Low | Atomic coordinates, B-factors | Validation of force fields against static structural benchmarks [14] |

| Cryo-EM | Near-atomic to atomic (3-5 Å) | N/A | Low (μg) | Medium | 3D density maps, conformational states | Capturing multiple conformational states for validating MD ensembles [14] [15] |

| ITC | N/A | nM-mM | High (mg) | Low | KD, ΔG, ΔH, ΔS, n (stoichiometry) | Direct experimental measurement of binding thermodynamics [16] |

| SPR | N/A | pM-mM | Low (μg) | High | KD, ka (association rate), kd (dissociation rate) | High-throughput screening of binding kinetics and affinities [16] |

Quantitative Correlation with Computational Methods

Table 2: Reported correlation performance between computational methods and experimental techniques

| Computational Method | Experimental Correlation | Target Systems | Performance Notes | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BAR (Bennett Acceptance Ratio) | R² = 0.7893 with experimental pKD [17] | GPCRs (β1AR) | Strong correlation with agonist-bound states | Requires extensive sampling, high computational cost |

| Jensen-Shannon Divergence Approach | R = 0.88 (BRD4), R = 0.70 (PTP1B) with experimental ΔG [18] | BRD4, PTP1B, JNK1 | Reduced computational cost vs. deep learning methods | Polarity of PC1-ΔG correlation requires estimation |

| MM/PBSA | Variable (highly system-dependent) | Soluble proteins | Faster than alchemical methods | Limited accuracy with implicit solvent models [17] |

| Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) | Potentially high with sufficient sampling | Various | Considered gold standard for accuracy | Extremely high computational cost, complex setup [18] [17] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Structural Techniques: From Sample to Atomic Coordinates

X-ray Crystallography Workflow

Protein crystallization remains a critical step requiring extensive optimization of conditions including pH, temperature, and precipitant concentration. For MD validation studies, the process typically involves:

- Crystal Formation: Commercial screening kits (e.g., Hampton Research) systematically explore chemical space to identify initial crystallization conditions. For membrane proteins, lipidic cubic phase methods are often employed [17].

- Cryo-cooling: Crystals are flash-cooled in liquid nitrogen with cryoprotectants (e.g., glycerol, ethylene glycol) to minimize radiation damage during data collection.

- Data Collection: Synchrotron sources provide high-intensity X-rays for diffraction data collection, with resolutions better than 3Å required for detailed MD validation [14].

- Structure Solution: Molecular replacement with known homologous structures or experimental phasing (MAD/SAD) methods generate electron density maps, followed by iterative model building and refinement.

The resulting atomic coordinates serve as critical benchmarks for validating MD-predicted binding poses and protein-ligand interactions, particularly for assessing complementarity-determining region (CDR) conformations in nanobody-antigen complexes [14].

Cryo-Electron Microscopy Protocol

Cryo-EM has emerged as a powerful technique for structural biology, particularly for complexes challenging to crystallize. The standard workflow includes:

- Grid Preparation: Ultrathin carbon films on 300-mesh gold grids are glow-discharged to increase hydrophilicity.

- Vitrification: 3-4 μL sample is applied to grids, blotted with filter paper for 3-6 seconds, and plunge-frozen in liquid ethane cooled by liquid nitrogen.

- Data Collection: Automated imaging collects thousands of micrographs at defocus values of -1.5 to -3.5 μm using direct electron detectors.

- Image Processing: Motion correction, particle picking, 2D classification, and 3D reconstruction generate density maps, with resolutions of 3-4Å now achievable for many complexes.

For MD validation, cryo-EM is particularly valuable for capturing multiple conformational states that can be used to validate simulated ensembles [15]. This is crucial for understanding mechanisms like the dynamic conformational changes of the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein [16].

Binding Affinity Measurements: Kinetic and Thermodynamic Profiling

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) Methodology

SPR provides real-time, label-free monitoring of molecular interactions through detection of refractive index changes near a sensor surface. A typical SPR experiment for validating MD predictions includes:

- Surface Functionalization: CMS sensor chips are activated with a 1:1 mixture of 0.4 M EDC and 0.1 M NHS for 7 minutes to generate reactive esters.

- Ligand Immobilization: The target protein (e.g., KpACE with 6×His tag) is diluted in appropriate buffer (e.g., acetate pH 5.0) and injected over specific flow cells to achieve desired immobilization level (typically 5-15 kRU) [16].

- Blocking: Remaining reactive groups are quenched with 1 M ethanolamine-HCl (pH 8.5) for 7 minutes.

- Analyte Binding: Serial dilutions of analyte (e.g., capsular polysaccharides) are injected in PBS-P+ running buffer using a contact time of 60-120 seconds and dissociation time of 120-300 seconds at a flow rate of 30 μL/min.

- Regeneration: Sensor surface is regenerated with 10-50 mM glycine-HCl (pH 2.0-3.0) for 30-60 seconds between cycles.

- Data Analysis: Double-referenced sensorgrams are fitted to 1:1 binding models using evaluation software to extract kinetic parameters (ka, kd) and calculate equilibrium constants (KD = kd/ka).

SPR's capability to measure both kinetics and affinity with minimal sample consumption makes it ideal for validating MD-predicted binding strengths, particularly for carbohydrate-protein interactions that pose challenges for other techniques [16].

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) Protocol

ITC directly measures heat changes during molecular interactions, providing complete thermodynamic profiles. The standard procedure involves:

- Sample Preparation: Both ligand and analyte are dialyzed into identical buffer (e.g., PBS, Tris-HCl) to minimize heats of dilution.

- Experimental Setup: The cell (typically 200 μL) is filled with target molecule at 10-100 μM concentration, while the syringe is loaded with ligand at 10-20 times higher concentration.

- Titration: A typical experiment consists of 15-25 injections of 1-10 μL ligand solution spaced 120-180 seconds apart to ensure return to baseline.

- Data Analysis: Integrated heat peaks are fitted to appropriate binding models to extract KD, ΔH, ΔS, and stoichiometry (n).

ITC-derived thermodynamic parameters provide critical validation for MD-predicted energy landscapes, with the enthalpy-entropy compensation offering insights into binding mechanisms [16].

Integration Framework: Connecting Experimental Data with MD Simulations

Conceptual Workflow for Experimental Validation

This framework illustrates the iterative process where MD simulations generate testable predictions that are validated against experimental data, leading to refined force fields and improved computational models [1] [15]. The bidirectional flow of information ensures that experiments guide computational improvements while simulations provide molecular insights that may be inaccessible to experiments alone.

Practical Implementation Strategies

Several strategies have emerged for effectively integrating experimental data with MD simulations:

Force Field Selection and Validation: Experimental data, particularly from NMR and SAXS, can be used to assess different force fields and identify the most trustworthy parameters for specific systems [15]. For example, NMR data on tetranucleotides and hexanucleotides have been used to compare force field performance for RNA simulations [15].

Ensemble Refinement Methods: Experimental data can improve simulated ensembles through either qualitative methods (using data to generate initial models or restrain simulations) or quantitative methods (maximum parsimony or maximum entropy approaches) [15]. The maximum entropy principle has been successfully applied to reweight simulated ensembles of RNA tetraloops to match NMR data [15].

Experimental Restraints in Sampling: Techniques like replica-exchange MD can incorporate experimental restraints to encourage but not enforce specific conformations, preserving natural dynamics while guiding sampling toward experimentally-consistent states [15]. This approach has been used with secondary structure information from chemical probing or NMR data.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key reagents and materials for experimental studies

| Reagent/Material | Specifications | Application | Function | Example Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPR Sensor Chips | CMS chip (carboxymethylated dextran) | SPR binding studies | Immobilization platform for ligands | Cytiva [16] |

| Amine Coupling Kit | EDC, NHS, ethanolamine-HCl | SPR surface chemistry | Covalent immobilization of ligands | Cytiva (BR100050) [16] |

| Crystallization Screens | 96-condition sparse matrix | X-ray crystallography | Initial crystal condition screening | Hampton Research |

| Cryo-EM Grids | 300-mesh gold grids with ultrathin carbon | Cryo-EM sample preparation | Support film for vitrified samples | Quantifoil, Thermo Fisher |

| His-Tag Purification Resins | Ni-NTA or Co-TALON | Protein purification | Affinity purification of recombinant proteins | Cytiva, Qiagen |

| Size Exclusion Columns | Superdex 200 Increase, S200 | Protein purification | Final polishing step for monodisperse samples | Cytiva |

The integration of structural biology (crystallography and cryo-EM) with biophysical binding assays (ITC and SPR) creates a powerful validation framework for MD simulations in drug discovery. Each technique contributes complementary information—atomic-resolution snapshots, conformational ensembles, thermodynamic parameters, and kinetic rates—that together provide a comprehensive benchmark for computational predictions. As recent studies demonstrate [17] [18], the correlation between computational binding affinity predictions and experimental measurements continues to improve, with methods like BAR and Jensen-Shannon divergence approaches showing particular promise. However, discrepancies between force fields [1] and the influence of simulation parameters beyond the force field itself highlight the ongoing need for rigorous experimental validation. By adopting the integrated workflows and comparative frameworks presented in this guide, researchers can enhance the reliability of MD simulations and accelerate the development of novel therapeutics.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have become indispensable "virtual molecular microscopes" for investigating protein dynamics, providing atomistic details that often remain hidden from traditional biophysical techniques [1]. However, a fundamental challenge persists: while experimental data typically represent spatial and temporal averages, the true functional properties of proteins emerge from their heterogeneous conformational ensembles—the entire collection of structures a protein samples over time [1] [19]. This discrepancy creates a critical validation gap for MD simulations, as multiple diverse conformational ensembles can produce averages consistent with experimental measurements, making it difficult to distinguish accurate from inaccurate models [1] [20].

The problem extends beyond force field accuracy alone. While improved force fields have dramatically enhanced simulation quality, other factors including water models, integration algorithms, constraint methods, and simulation ensemble choices significantly influence outcomes [1]. This complexity means that benchmarking simulations requires careful consideration of multiple interdependent factors, not merely selection of an appropriate force field. For researchers in drug discovery, where accurate prediction of binding affinities and mechanisms depends on understanding conformational heterogeneity, this challenge is particularly acute [17].

The Validation Challenge: When Agreement with Experiment Is Not Enough

The Ambiguity of Experimental Averages

The core challenge in validating conformational ensembles lies in the nature of experimental data interpretation. Most experimental techniques provide measurements that represent averages over both space and time, obscuring the underlying distributions and timescales [1]. For example:

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy provides data such as chemical shifts and J-couplings that are ensemble-averaged properties [20] [21].

- Small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) yields a scattering profile that represents an average over all conformations present in solution [20] [15].

- X-ray crystallography may be affected by crystal packing forces that restrict natural dynamics [15].

This averaging creates inherent ambiguity, as strikingly different conformational distributions can yield identical experimental averages [1]. Consequently, correspondence between simulation and experiment does not necessarily validate the underlying conformational ensemble produced by MD [1].

Evidence from Comparative Simulation Studies

Comprehensive studies demonstrate this validation challenge directly. Research comparing four MD simulation packages (AMBER, GROMACS, NAMD, and ilmm) with three different force fields revealed that while overall reproduction of experimental observables was similar for two globular proteins at room temperature, subtle differences in conformational distributions and sampling extent were evident [1]. This ambiguity makes it difficult to determine which results are correct when experiment cannot provide the necessary detailed information to distinguish between underlying ensembles [1].

The divergence becomes more pronounced when studying larger amplitude motions, such as thermal unfolding. Some simulation packages failed to allow proteins to unfold at high temperature or produced results inconsistent with experiment, despite using similar force fields [1]. This indicates that factors beyond the force field itself—including water models, algorithms constraining motion, treatment of atomic interactions, and simulation ensemble—significantly influence outcomes [1].

Table 1: Key Experimental Observables for Validating Conformational Ensembles

| Experimental Technique | Primary Observables | Structural Information Provided | Limitations for Ensemble Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| NMR Spectroscopy | Chemical shifts, J-couplings, RDCs, relaxation parameters [20] [21] | Local atomic environment, dihedral angles, global orientation, dynamics on various timescales [21] | Challenging to interpret; sensitive to multiple structural properties; sparse data [20] |

| SAXS/WAXS | Scattering intensity profile [20] [15] | Overall shape, radius of gyration, molecular size and compactness [15] | Low resolution; represents ensemble average; multiple ensembles can fit data [20] |

| Single-molecule FRET | Energy transfer efficiency [15] | Inter-dye distances and distributions, population of conformational states [15] | Dye labeling effects; limited structural resolution; interpretation requires models [15] |

| Cryo-EM | Electron density maps [15] | 3D density at intermediate resolution, large-scale conformational features [15] | Potential restriction of dynamics; limited resolution for flexible regions [15] |

Quantitative Comparisons: Benchmarking Force Fields and Simulation Methods

Performance Variations Across Force Fields

Recent systematic benchmarking efforts reveal how different force fields perform in reproducing the conformational ensembles of intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs). One comprehensive study assessed three state-of-the-art protein force field and water model combinations (a99SB-disp, Charmm22*, and Charmm36m) by comparing against extensive NMR and SAXS datasets [20]. The findings demonstrated that:

- In favorable cases where IDP ensembles from different force fields showed reasonable initial agreement with experimental data, reweighted ensembles converged to highly similar conformational distributions [20].

- For three of the five IDPs studied (Aβ40, ACTR, and PaaA2), reweighted ensembles became highly similar across force fields, suggesting force-field independent approximations of the true solution ensembles [20].

- For two IDPs (drkN SH3 and α-synuclein), unbiased MD simulations with different force fields sampled distinctly different regions of conformational space, with the reweighting procedure clearly identifying the most accurate ensemble [20].

These results highlight both the progress and persistent challenges in force field development, showing that while modern force fields have improved significantly, notable differences remain in their ability to sample biologically relevant conformational states [20].

Table 2: Force Field Performance in Reproducing IDP Conformational Ensembles

| Force Field & Water Model | Representative Strengths | Limitations | Convergence After Reweighting |

|---|---|---|---|

| a99SB-disp with a99SB-disp water [20] | Good performance for IDPs; balanced interactions [20] | Specific parameterization challenges | Converged with other force fields for 3/5 IDPs [20] |

| Charmm22* with TIP3P water [20] | Established benchmark; extensive validation [20] | Less accurate for certain IDP sequences | Converged with other force fields for 3/5 IDPs [20] |

| Charmm36m with TIP3P water [20] | Improved torsion potentials; better IDP behavior [20] | Occasional over-compaction in specific regions | Converged with other force fields for 3/5 IDPs [20] |

Binding Affinity Predictions: A Critical Test for Drug Discovery

For MD applications in drug discovery, accurate prediction of binding affinities represents a crucial validation test. Recent research on G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) demonstrates both capabilities and limitations:

- Binding free energy calculations using the re-engineered Bennett acceptance ratio (BAR) method showed significant correlation (R² = 0.7893) with experimental pK₃ values for β₁ adrenergic receptor agonists [17].

- The method successfully captured pharmacologically relevant state selectivity, with full agonists showing larger free energy differences between inactive and active states compared to weak partial agonists [17].

- However, technical challenges remain, including the high computational cost of explicit membrane models and the need for extensive equilibration to ensure system stability [17].

These results highlight how comparing computational results with experimental binding data provides essential validation for simulations aimed at drug discovery applications.

Methodological Solutions: Protocols for Improved Ensemble Validation

Maximum Entropy Reweighting: A Path to Force-Field Independent Ensembles

The maximum entropy principle has emerged as a powerful framework for integrating experimental data with MD simulations to determine accurate conformational ensembles [20] [19]. This approach:

- Seeks to introduce the minimal perturbation to a computational model required to match experimental data [20].

- Provides a statistically sound mechanism for combining experimental data with molecular dynamics simulations [19].

- Can produce force-field independent ensembles when sufficient experimental data is available [20].

A recently developed automated maximum entropy reweighting procedure uses a single adjustable parameter—the desired number of conformations in the calculated ensemble—to effectively combine restraints from multiple experimental datasets [20]. This approach automatically balances restraint strengths based on the effective ensemble size, avoiding the need for manually tuning restraint strengths that can strongly influence results [20].

Diagram 1: Maximum entropy reweighting workflow for determining accurate conformational ensembles

Enhanced Sampling and Free Energy Calculations

For binding affinity predictions and other pharmaceutically relevant applications, enhanced sampling methods play a crucial role in obtaining converged results:

- Alchemical methods such as free energy perturbation (FEP), thermodynamic integration (TI), and the Bennett acceptance ratio (BAR) can improve correlations with experimental binding affinities [17].

- Replica-exchange approaches help overcome kinetic traps and sample relevant conformational states [15] [19].

- Metadynamics and umbrella sampling address high energy barriers between states [17] [19].

These methods are particularly important for studying complex biomolecular systems such as membrane proteins, intrinsically disordered proteins, and nucleic acids, where relevant biological timescales may extend beyond conventional MD capabilities [22].

Best Practices and Reproducibility Framework

Essential Protocols for Reliable Simulations

To ensure reliability and reproducibility in MD simulations, researchers should adopt established best practices:

- Perform multiple independent simulations: At least three independent simulations starting from different configurations with statistical analysis help detect lack of convergence [22].

- Validate with multiple experimental data types: Using diverse experimental observables (NMR, SAXS, FRET) provides more rigorous validation than reliance on a single data type [20] [15].

- Report simulation details comprehensively: Include force field versions, water models, simulation length, integration algorithms, and constraint methods [1] [22].

- Assess convergence rigorously: Use time-course analysis and multiple metrics to evaluate whether simulated properties have stabilized [22].

- Provide input files and parameters: Deposit simulation input files and final coordinate files in public repositories to enable reproduction [22].

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Resources for Ensemble Validation

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| MD Simulation Software | AMBER, GROMACS, NAMD, CHARMM [1] | Molecular dynamics engine | Running production simulations with different algorithms and force fields |

| Force Fields | AMBER ff99SB-ILDN, CHARMM36, a99SB-disp, Charmm36m [1] [20] | Mathematical description of atomic interactions | Determining accuracy of physical model in simulations |

| Water Models | TIP3P, TIP4P-EW, a99SB-disp water [1] [20] | Solvent representation | Critical influence on solute behavior and dynamics |

| Experimental Data Sources | NMR chemical shifts, SAXS profiles, FRET efficiencies [20] [21] [15] | Experimental restraints for validation | Providing experimental basis for benchmarking simulations |

| Reweighting Algorithms | Maximum entropy methods, Bayesian inference [20] [19] | Integrating simulation and experiment | Refining ensembles to match experimental data |

| Validation Metrics | Kish ratio, χ² values, ensemble similarity measures [20] | Quantifying agreement and convergence | Assessing quality of conformational ensembles |

Diagram 2: Decision framework for validating conformational ensembles

The challenge of reproducing underlying conformational ensembles beyond simple averages remains substantial but increasingly tractable with modern methodologies. The key insights for researchers validating MD simulations with experimental data include:

- Agreement with experimental averages is necessary but insufficient for validating conformational ensembles, as multiple distributions can yield identical averages [1].

- Integrative approaches combining MD simulations with experimental data through maximum entropy reweighting can yield force-field independent ensembles in favorable cases [20].

- Multiple types of experimental data provide more rigorous validation than any single technique alone [20] [15].

- Comprehensive reporting of simulation parameters and protocols is essential for reproducibility and reliability [22].

As force fields continue to improve and integrative methods become more sophisticated, the field appears to be maturing from assessing disparate computational models toward genuine atomic-resolution integrative structural biology [20]. For drug discovery researchers, these advances promise more reliable predictions of binding affinities and mechanisms, ultimately supporting more efficient development of therapeutic interventions.

From Theory to Practice: A Toolkit of Methods for MD Simulation Validation

In modern computational drug discovery, predicting the binding affinity between a protein and a ligand is a cornerstone for efficient lead optimization. The choice of computational method involves a critical trade-off between computational cost and predictive accuracy. Molecular docking, MM/GB(PB)SA, and Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) represent a spectrum of approaches, from fast, approximate screening to highly accurate, physics-based calculation. This guide objectively compares the performance of these methods against experimental binding data, providing a framework for researchers to select the appropriate tool based on their project's stage and requirements.

Comparative Performance Analysis

The table below summarizes the key characteristics and typical performance metrics of each method, providing a high-level overview for researchers.

Table 1: Key Characteristics and Performance of Computational Methods

| Method | Theoretical Basis | Speed | Accuracy (MAD vs. Experiment) | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Docking | Empirical/Knowledge-based scoring functions | Very Fast (seconds to minutes) | Low (Poor correlation with experiment) [23] | High-throughput virtual screening |

| MM/GB(PB)SA | End-point free energy method | Medium (hours to days) | Moderate (Competitive with FEP in some benchmarks) [24] [25] | Post-docking refinement, affinity ranking for congeneric series |

| Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) | Alchemical pathway method | Slow (days to weeks) | High (MAD often < 1.0 kcal/mol, ~2.0 kcal/mol in scaffold hopping) [23] [26] | Lead optimization for congeneric compounds, RBFE calculations |

Quantitative Accuracy Benchmarks

Rigorous benchmarking against experimental data is crucial for evaluating predictive performance. The following table consolidates quantitative results from systematic studies across various protein targets.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Benchmarks Against Experimental Data

| Study & System | Method | Key Performance Metric | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| PLK1 Inhibitors (20 compounds) [23] | FEP | Spearman's rank coefficient (rs) | 0.854 |

| MM-GBSA (SLMDmbondi2PM6igb5) | Spearman's rank coefficient (rs) | 0.767 | |

| Docking (ChemPLP) | Spearman's rank coefficient (rs) | Poor correlation | |

| PDE5 Inhibitors (Scaffold Hopping) [26] | FEP | Mean Absolute Deviation (MAD) | < 2.0 kcal/mol |

| MM-PBSA/MM-GBSA | Mean Absolute Deviation (MAD) | > 2.0 kcal/mol | |

| 6 Soluble & 3 Membrane Proteins (140 & 37 ligands) [24] [25] | MM/PB(GB)SA | Overall Accuracy | Competitive with FEP |

| FEP | Overall Accuracy | Competitive with MM/PB(GB)SA | |

| Docking | Overall Accuracy | Worst outcome |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Free Energy Perturbation (FEP)

FEP is a pathway method that calculates the free energy difference between two states by gradually perturbing one ligand into another within the binding site. Its high accuracy comes from extensive sampling of configurations with explicit solvent [27] [28].

- System Setup: A pre-docked protein-ligand complex is solvated in an explicit water box (e.g., TIP3P) with ions for neutralization. OPLS or similar force fields are standard [23] [26].

- Simulation Protocol: The transformation from ligand A to ligand B is divided into multiple intermediate "λ windows". In each window, a molecular dynamics (MD) simulation is run (e.g., 5 ns per window). The Hamiltonian of the system is gradually changed from describing ligand A to describing ligand B across these windows [23].

- Analysis: The free energy change (ΔΔG) is computed by combining the results from all λ windows, often using the Bennet Acceptance Ratio (BAR) method. The entire process can require 60 ns of cumulative simulation time per perturbation [23] [26].

MM/GB(PB)SA

MM/GB(PB)SA is an end-point method, meaning it uses only the initial (unbound) and final (bound) states to calculate binding free energy, offering a balance between speed and accuracy [24] [25].

- System Setup: A single MD simulation of the protein-ligand complex in explicit solvent is performed to generate an ensemble of snapshots.

- Free Energy Calculation: The binding free energy for each snapshot is calculated as:

ΔG_bind = ΔE_MM + ΔG_solv - TΔSwhere:ΔE_MMis the gas-phase molecular mechanics energy (electrostatic + van der Waals).ΔG_solvis the solvation free energy, decomposed into polar (ΔG_GB/PB) and non-polar (ΔG_SA) components. The polar term is calculated by Generalized Born (GB) or Poisson-Boltzmann (PB) models, while the non-polar term is estimated from the solvent-accessible surface area (SASA) [24] [25].-TΔSis the entropic contribution, often omitted due to its high computational cost and large error [24].

- Critical Parameters: Performance is highly case-specific. Key parameters that require benchmarking for each system include the GB model, internal dielectric constant, and for membrane proteins, the membrane dielectric constant [24] [25].

Molecular Docking

Docking rapidly predicts the binding pose and affinity of a ligand by searching its orientation and conformation within the protein's binding site and scoring the resulting complexes.

- Workflow: The ligand and protein are prepared (e.g., assignment of partial charges, protonation states). The ligand is then systematically posed in the binding site, and a scoring function evaluates the quality of each pose [24].

- Scoring Functions: These are simplified mathematical functions to predict affinity. They can be:

- Force Field-based: Calculate energies based on van der Waals, electrostatic, and bond deformation terms. One study found them more suitable for ranking congeneric compounds [23].

- Empirical: Use parameters derived from experimental binding data.

- Knowledge-based: Based on statistical atom-pair potentials observed in known structures.

Diagram Title: Workflow Comparison of Docking, MM/GB(PB)SA, and FEP

Successful application of these computational methods relies on a suite of software tools and force fields.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Category | Item | Function | Example Software/Force Fields |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Simulation Engines | Molecular Dynamics (MD) Engine | Simulates the motion of atoms over time under a force field. | Desmond [23], GROMACS |

| Free Energy Calculation Tool | Performs alchemical FEP calculations. | FEP+ (Schrödinger) [28], GROMACS with plugins | |

| Analysis Utilities | MM/GB(PB)SA Analysis Tool | Calculates binding free energies from MD trajectories. | gmx_MMPBSA [24], MMPBSA.py [24] |

| Force Fields | Biomolecular Force Field | Defines potential energy functions for proteins, nucleic acids, etc. | OPLS [23], AMBER, CHARMM |

| Small Molecule Force Field | Defines parameters for drug-like molecules. | OPLS [23], GAFF [26], CGenFF [24] | |

| System Preparation | Ligand Parametrization Tool | Assigns partial charges and force field parameters to ligands. | CGenFF program [24], antechamber (AMBER) |

| Water Model | Represents solvent water molecules in simulations. | TIP3P [23], SPC, TIP4P |

Integrating Ensemble-Based Simulations for Robust and Reproducible Free Energy Calculations

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have become an indispensable tool in computational biophysics and structure-based drug design, with free energy simulations (FES) standing as a particularly valuable methodology for predicting binding affinities, solvation free energies, and other essential thermodynamic properties [29]. However, the reliability of these simulations has historically been limited by two fundamental challenges: the inherent chaotic nature of MD simulations that leads to non-reproducible results, and the accuracy of the computational methods employed [29] [30]. The field has increasingly recognized that ensemble-based approaches—running multiple replicas of simulations with different initial conditions—provide the most robust solution to these challenges, enabling researchers to quantify uncertainties and achieve statistically meaningful results [30].

The necessity for ensemble approaches stems from the probabilistic nature of MD simulations, where quantities of interest (QoIs) exhibit significant variability between single runs due to the complex energy landscapes of biomolecular systems [30]. Recent systematic studies have demonstrated that binding free energy calculations often produce non-Gaussian distributions, with notable skewness, kurtosis, and occasionally multimodal characteristics [30]. This fundamental insight has transformed best practices in the field, shifting the focus from single long simulations to ensembles of shorter replicas that collectively provide more reliable estimation of thermodynamic properties and their associated uncertainties.

Comparative Analysis of Ensemble-Based Free Energy Protocols

Several specialized protocols have been developed to implement ensemble-based free energy calculations, each with distinct advantages and applications. The ESMACS (Enhanced Sampling of Molecular Dynamics with Approximation of Continuum Solvent) protocol employs an end-point approach based on the molecular mechanics Poisson-Boltzmann surface area (MMPBSA) method, utilizing ensembles of replicas to obtain reproducible binding affinity estimates with robust uncertainty quantification [31]. In contrast, the TIES (Thermodynamic Integration with Enhanced Sampling) protocol implements an alchemical approach centered on thermodynamic integration, similarly employing ensemble methodologies to enhance reliability [31]. Both methods are typically implemented through automated pipelines such as the Binding Affinity Calculator (BAC), which handles the complex process of running ensemble calculations [31].

Alchemical free energy methods, including free energy perturbation (FEP) and thermodynamic integration (TI), work by constructing a pathway of intermediate states between the physical states of interest [32]. The Multistate Bennett Acceptance Ratio (MBAR) method provides a statistically optimal approach for analyzing data from these simulations, estimating free energy changes between different states and thermodynamic averages from simulation trajectory data [33]. MBAR serves as an extension of Bennett's acceptance ratio method to multiple states and can be interpreted as the limit of infinitesimal bin size in the weighted histogram analysis method (WHAM) [33].

Performance Comparison of Protocol Types

Table 1: Comparison of Ensemble-Based Free Energy Calculation Protocols

| Protocol | Methodology | Applications | Strengths | Computational Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESMACS | End-point (MMPBSA/MMGBSA) | Absolute binding free energies | High throughput, good for ranking compounds | Moderate (ensemble of short simulations) |

| TIES | Alchemical (Thermodynamic Integration) | Relative binding free energies | High precision, excellent correlation with experiment | High (requires multiple λ windows) |

| MBAR/FEP | Alchemical (Free Energy Perturbation) | Solvation free energies, relative binding | Statistically optimal, minimal variance | High (requires overlap between states) |

| Umbrella Sampling | Pathway-dependent (Potential of Mean Force) | Binding pathways, conformational changes | Provides mechanistic insights | Very high (requires reaction coordinate) |

In practical applications, these protocols have demonstrated remarkable performance in blind challenges and validation studies. For instance, the TIES protocol achieved an exceptional Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.90 between calculated and experimental activities for a set of compounds binding to ROS1 kinase, despite an unexplained systematic overestimation [31]. Similarly, ESMACS simulations have shown good correlations with experimental data for subsets of compounds, enabling reliable ranking of binding affinities [31].

The performance of these methods depends critically on proper implementation of ensemble approaches. A study on DNA-intercalator binding energies demonstrated that results from 25 replicas of 10 ns simulations closely matched those from 25 replicas of 100 ns simulations for the Doxorubicin-DNA system, with MM/PBSA binding energies of -7.6 ± 2.4 kcal/mol (10 ns) versus -7.3 ± 2.0 kcal/mol (100 ns), both aligning well with the experimental range of -7.7 ± 0.3 to -9.9 ± 0.1 kcal/mol [34]. This highlights that reproducibility and accuracy depend more on the number of replicas than on individual simulation length, provided sufficient sampling of essential configurations is achieved.

Implementation Frameworks and Workflows

Optimal Ensemble Design Strategies

Determining the optimal balance between the number of replicas and simulation length represents a crucial consideration in designing efficient free energy calculations. Systematic investigations have revealed that when computational resources are fixed, running more shorter simulations generally provides better statistical reliability than fewer longer simulations [30]. For instance, with a fixed computational budget of 60 ns per compound, protocols using 30 × 2 ns or 20 × 3 ns replicas typically yield smaller error bars and more reliable free energy estimates compared to 12 × 5 ns or 6 × 10 ns approaches [30].

Bootstrap analyses for DNA-intercalator systems further refined these recommendations, suggesting that 6 replicas of 100 ns or 8 replicas of 10 ns provide a good balance between computational efficiency and accuracy within 1.0 kcal/mol from experimental values [34]. This general principle, however, requires modification for systems with complex conformational landscapes where longer simulations may be necessary to sample relevant states [30].

Table 2: Recommended Ensemble Configurations for Different Scenarios

| System Type | Recommended Protocol | Typical Ensemble Size | Simulation Length per Replica | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rigid protein-small molecule | ESMACS/TIES | 20-30 replicas | 2-5 ns | Good for congeneric series |

| Flexible binding sites | TIES/MBAR | 25+ replicas | 5-10 ns | Requires more sampling |

| Membrane proteins | Alchemical FEP | 20+ replicas | 10-20 ns | Additional complexity from lipids |

| DNA/RNA complexes | ESMACS/MMPBSA | 25+ replicas | 5-15 ns | Account for charged backbone |

Workflow Integration and Automation

Robust implementation of ensemble-based free energy calculations requires specialized software tools and automated workflows. Several automated pipelines have been developed to streamline this process, including commercial options like FEP+ and Molecular Operating Environment (MOE), as well as non-commercial alternatives like Amber free energy workflow (FEW), FESetup, FEPrepare, and CHARMM-GUI FEP calculator [31]. The Binding Affinity Calculator (BAC) represents one such comprehensive pipeline designed to automate the end-to-end execution of free energy calculations, with specific capabilities for handling ensemble calculations [31].

These automated workflows typically encompass several critical stages: system preparation and parameterization using force fields such as ff14SB for proteins and GAFF2 for small molecules; solvation and electrostatic neutralization; generation of multiple replicas with different initial velocities; production simulation with appropriate λ-scheduling for alchemical methods; and finally analysis with uncertainty quantification [31]. The availability of these automated tools has significantly increased the accessibility and reproducibility of ensemble-based free energy methods for non-expert users.

Diagram 1: Ensemble Free Energy Calculation Workflow. This diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for ensemble-based free energy calculations, highlighting the critical step of generating multiple replicas and subsequent statistical analysis.

Experimental Validation and Force Field Considerations

Correlation with Experimental Data

The ultimate validation of any computational free energy method lies in its correlation with experimental measurements. Ensemble-based approaches have demonstrated remarkable success in this regard across diverse biological systems. In the case of ROS1 kinase inhibitors, the TIES protocol achieved exceptional ranking of binding affinities with a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.90 between calculated and experimental activities [31]. Similarly, for DNA-intercalator systems, ensemble-based MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA calculations produced binding energies that closely matched experimental ranges, with the Doxorubicin-DNA system showing calculated values of -7.3 ± 2.0 kcal/mol (MM/PBSA) and -8.9 ± 1.6 kcal/mol (MM/GBSA) compared to the experimental range of -7.7 ± 0.3 to -9.9 ± 0.1 kcal/mol [34].

The integration of experimental data with simulations extends beyond simple validation, enabling refinement of both structural ensembles and force field parameters. Experimental techniques such as NMR, cryo-electron microscopy, SAXS/WAXS, chemical probing, and single-molecule FRET provide ensemble averages over accessible structures that can be used to improve simulated ensembles through methods like maximum entropy reweighting or maximum parsimony approaches [15]. This integrative strategy is particularly valuable for RNA systems, where force field accuracy remains challenging, but has broad applicability across biomolecular systems [15].

Force Field Selection and Validation

The accuracy of free energy calculations depends critically on the force field employed, with recent years showing significant improvements in both protein and nucleic acid parameters. Systematic validations of protein force fields against experimental data have demonstrated that modern force fields such as Amber ff99SB-ILDN, ff99SB-ILDN, ff03, CHARMM22*, and others provide reasonably accurate descriptions of protein structure and dynamics [35]. These validations typically involve comparisons with NMR data for folded proteins, quantification of potential biases toward different secondary structure types using small peptides, and testing the ability to fold small proteins [35].

For membrane proteins and peptides, specialized considerations apply, including proper treatment of lipid-protein interactions and careful setup of membrane environments [36]. Similarly, RNA simulations present unique challenges due to the complex electrostatic and conformational properties of nucleic acids, often requiring specific parameter adjustments and enhanced sampling techniques [15]. The combination of quantum mechanical/molecular mechanical (QM/MM) approaches with free energy calculations represents a promising direction for improving accuracy, though these methods remain computationally demanding [29].

Diagram 2: Experimental Validation Cycle. This diagram illustrates the iterative process of validating simulation ensembles against experimental data and refining either force field parameters or structural ensembles based on discrepancies.

Computational Tools and Force Fields

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| MD Engines | GROMACS, AMBER, OpenMM, NAMD | Molecular dynamics simulations | Performance, algorithm implementation |

| Free Energy Analysis | MBAR, Bennett Acceptance Ratio | Free energy estimation | Statistical optimality, minimal variance |

| Force Fields | Amber ff19SB, CHARMM36, GAFF2 | Molecular mechanics parameters | Accuracy for specific biomolecules |

| Automation Workflows | BAC, FESetup, CHARMM-GUI FEP | Automated setup and analysis | Reproducibility, high-throughput capability |

| Enhanced Sampling | PLUMED, WESTPA | Accelerated configuration space exploration | Efficient barrier crossing |

Practical Implementation Recommendations

Successful implementation of ensemble-based free energy calculations requires attention to several practical considerations. First, proper system preparation is essential, including careful parameterization of small molecules using appropriate methods (AM1-BCC has been suggested to be preferable to RESP for charge generation) [31]. Solvation should use sufficiently large water boxes with a minimum extension from the protein of 14 Å, with counterions added to neutralize the system [31].

For alchemical free energy calculations, the choice of λ values and soft-core parameters significantly impacts convergence. While simultaneous transformation of both electrostatic and van der Waals interactions can be performed for simplicity, best practice typically involves separating these stages for higher accuracy [32]. The number of λ points should be sufficient to ensure phase space overlap between adjacent states, typically ranging from 12-24 windows for complex transformations [33].

Statistical analysis should always include uncertainty quantification, accounting for both stochastic uncertainties within replicas and potential systematic errors. The MBAR method not only provides optimal free energy estimates but also enables calculation of statistical uncertainties, which is crucial for assessing the reliability of predictions [33]. Additionally, researchers should be aware of potential non-Gaussian distributions in binding free energies and ensure sufficient replica numbers to characterize these distributions adequately [30].

Ensemble-based approaches have fundamentally transformed the reliability and reproducibility of free energy calculations in molecular simulations. By explicitly addressing the chaotic nature of MD simulations through multiple replicas, these methods enable robust statistical analysis and uncertainty quantification that was impossible with single simulations. The development of automated workflows like ESMACS and TIES, coupled with advanced statistical methods like MBAR, has made these approaches increasingly accessible to the broader research community.

The integration of experimental data with simulation ensembles represents a particularly promising direction, enabling not only validation of computational methods but also refinement of force fields and structural ensembles. As force fields continue to improve and computational resources expand, ensemble-based free energy calculations will play an increasingly central role in drug discovery and biomolecular engineering. The demonstrated success of these methods in accurately predicting binding affinities for pharmaceutically relevant targets underscores their growing importance in rational drug design.

Future developments will likely focus on increasing computational efficiency through optimized ensemble designs, improved force fields with better treatment of polarization and charge transfer, and more sophisticated machine learning approaches for analyzing high-dimensional simulation data. The continued integration of experimental data with simulations will further enhance the predictive power of these methods, ultimately enabling more reliable and efficient drug discovery pipelines.

Leveraging Machine Learning and AI to Augment and Refine Physics-Based Predictions

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations provide atomistic insights into biological processes, such as protein-ligand binding, which is crucial for drug discovery. However, the accuracy of purely physics-based predictions can be limited by insufficient sampling and high computational costs [17]. Machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) are now transforming this field by augmenting and refining these physics-based predictions. By integrating data-driven models with physical principles, researchers can achieve more robust and efficient predictions of molecular behavior, creating a powerful synergy where ML models overcome the sampling limitations of MD, and physics ensures the predictions are scientifically plausible [37] [38]. This guide compares the performance of various integrated approaches, detailing their methodologies, experimental validation, and implementation requirements to aid researchers in selecting the optimal strategy for their projects.

Comparative Methodologies and Workflows

Different strategies have emerged for combining ML and MD simulations, ranging from analysis of MD trajectories to generative AI for molecular design. The table below compares four prominent methodologies.

Table 1: Comparison of Integrated ML and Physics-Based Methodologies

| Methodology | Core ML Technique | Physics Integration | Primary Application | Reported Correlation (R²) with Experiment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ML-Augmented MD Analysis [39] | Logistic Regression, Random Forest, Multilayer Perceptron | MD Simulation Trajectories | Identify key residues for binding affinity from MD | Varies by system and model |

| Generative AI with Active Learning [40] | Variational Autoencoder (VAE) | Docking Scores, Molecular Dynamics | De novo design of drug-like molecules | 8 out of 9 synthesized molecules showed in vitro activity for CDK2 |

| NucleusDiff for Drug Design [37] | Denoising Diffusion Model | Manifold constraints to prevent atomic collisions | Structure-based drug design | Increased accuracy and reduced atomic collisions by up to two-thirds |

| JS-Divergence on Trajectories [18] | Jensen-Shannon Divergence | MD Simulation Trajectories | Protein-ligand binding affinity prediction | 0.88 for BRD4, 0.70 for PTP1B |

Workflow: Generative AI with Active Learning for Drug Design

A leading approach for de novo molecular design involves a Variational Autoencoder (VAE) nested within active learning (AL) cycles [40]. This workflow generates novel, synthesizable molecules with high predicted affinity.

Workflow: ML Analysis of MD Trajectories for Binding Affinity

For predicting protein-ligand binding affinity, a robust method involves using MD trajectories to train ML models or compute efficient similarity metrics [39] [18].

Performance Benchmarking and Experimental Validation

Quantitative Binding Affinity Predictions

Validating these integrated approaches against experimental data is crucial. The following table summarizes the performance of several methods on established biological targets.

Table 2: Experimental Validation of Binding Affinity Prediction Methods

| Target Protein | Method | Experimental Correlation | Key Performance Metric |

|---|---|---|---|

| BRD4 [18] | JS-Divergence on MD Trajectories | R = 0.88 with experimental ΔG | Halved required MD simulation time vs. prior method |

| PTP1B [18] | JS-Divergence on MD Trajectories | R = 0.70 with experimental ΔG | Eliminated need for deep learning in similarity estimation |

| β1AR (GPCR) [17] | Re-engineered BAR Method | R² = 0.7893 with experimental pK𝐷 | Demonstrated efficacy on membrane protein targets |