Beyond the Genome: Integrating NGS with Multi-Omics to Power Next-Generation Precision Oncology

The molecular complexity of cancer demands a systems-level approach that moves beyond single-omics analyses.

Beyond the Genome: Integrating NGS with Multi-Omics to Power Next-Generation Precision Oncology

Abstract

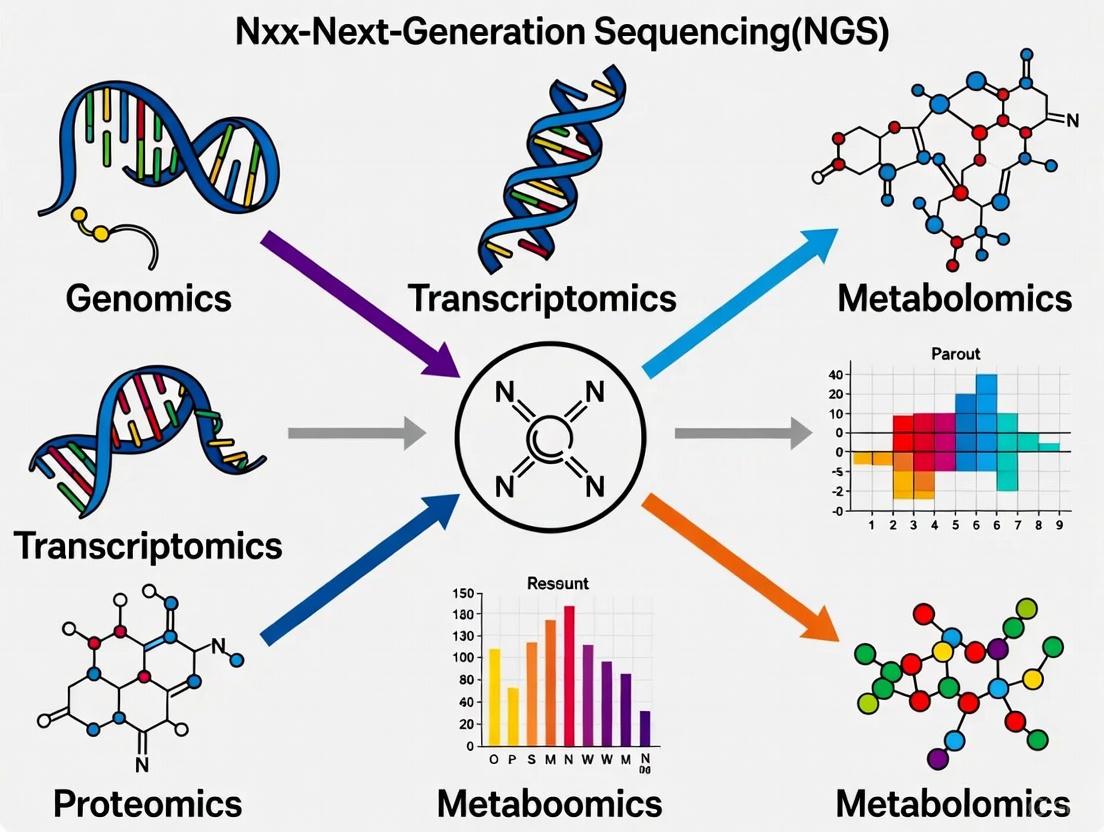

The molecular complexity of cancer demands a systems-level approach that moves beyond single-omics analyses. This article explores the integration of Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) with complementary omics layers—including transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and epigenomics—to build a holistic view of tumor biology. We examine the foundational principles of multi-omics, detail cutting-edge AI and machine learning methodologies for data integration, address critical challenges in data harmonization and clinical implementation, and validate these approaches through real-world applications in therapy selection, resistance monitoring, and clinical trial stratification. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes how integrated multi-omics is transforming oncology from a reactive to a proactive, personalized discipline.

Decoding Cancer Complexity: The Foundational Role of NGS in a Multi-Omics Framework

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized oncology research by providing an unprecedented window into the genomic landscape of cancer [1]. This massively parallel sequencing technology can process millions of DNA fragments simultaneously, dramatically reducing the cost and time required for genetic analysis compared to first-generation Sanger sequencing [2]. In clinical oncology, NGS has become the workhorse for identifying driver mutations, characterizing tumor mutational burden, and deciphering mutational signatures that reveal the historical activity of carcinogenic processes [1].

However, cancer is not merely a genetic disease—it operates through complex, interconnected molecular layers that extend beyond the genome. The fundamental limitation of a single-omics approach relying exclusively on NGS lies in its inability to capture the dynamic flow of biological information from DNA to RNA to proteins and functional phenotypes [3]. While NGS excels at identifying genomic variants, it cannot determine how these variants functionally influence cellular processes, treatment responses, and disease progression without integration with other molecular data types [4]. This application note delineates the specific constraints of NGS as a standalone technology and provides frameworks for its integration with multi-omics approaches to achieve a more comprehensive understanding of cancer biology.

Key Limitations of Single-Omics NGS Approaches

Inability to Capture Functional Molecular Dynamics

NGS provides a static snapshot of the genetic code but fails to reveal how this code is dynamically executed within cancer cells.

- Transcriptomic Regulation: DNA-level mutations identified by NGS may not consistently correlate with gene expression levels due to complex regulatory mechanisms. Transcriptomics is required to understand which mutations actually influence messenger RNA (mRNA) production [3] [5].

- Protein-Level Expression and Modification: The presence of an mRNA transcript does not guarantee its translation into functional protein, and protein activity is further modulated by post-translational modifications invisible to genomic analysis [6]. Proteomic technologies are necessary to quantify actual protein expression and functional states [3].

- Metabolic Reprogramming: Cancer cells undergo significant metabolic alterations (e.g., Warburg effect) that support rapid proliferation. These biochemical changes can only be profiled through metabolomics, representing a critical functional layer beyond genomic alterations [4] [3].

Obscuring of Cellular Heterogeneity

Traditional bulk NGS approaches average molecular signals across thousands to millions of cells, effectively masking critical cellular subpopulations that drive disease progression and therapeutic resistance [7] [5].

Table: Limitations of Bulk NGS in Resolving Cellular Heterogeneity

| Aspect of Heterogeneity | Impact of Bulk NGS | Biological Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Rare subclones | Obscured by dominant populations | Missed drivers of resistance |

| Tumor evolution | Inferred rather than directly observed | Incomplete evolutionary history |

| Tumor microenvironment | Stromal and immune signals averaged | Missed cell-cell interactions |

| Metastatic potential | Subclones with invasive properties masked | Limited prediction of spread |

Technical and Analytical Constraints

NGS technologies introduce specific technical artifacts and analytical challenges that can confound biological interpretation.

- Sequencing Biases and Artifacts: Different NGS platforms have inherent sequencing biases specific to their library preparation protocols and sequencing chemistry. These technical artifacts can impact the reliable discovery of true biological signatures, particularly when examining mutational processes [1].

- Variant Interpretation Challenges: NGS identifies numerous genetic variants, but distinguishing pathogenic driver mutations from benign passenger mutations remains challenging. Variants of Unknown Significance (VUS) represent a particular interpretive hurdle with limited clinical actionability [8].

- Incomplete Functional Context: While NGS can identify mutations in DNA repair pathways (e.g., homologous recombination deficiency), it cannot directly quantify the functional consequences of these defects, requiring additional functional assays for validation [1].

Multi-Omics Integration: Overcoming NGS Limitations

Multi-Omics Technologies and Their Value Proposition

Integrating NGS with other omics technologies creates a synergistic framework that overcomes the limitations of single-layer analysis.

Table: Multi-Omics Technologies Complementing NGS in Oncology

| Omics Layer | Technology Platforms | Complementary Value to NGS | Clinical/Research Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transcriptomics | RNA-seq, Single-cell RNA-seq | Links DNA variants to gene expression | Gene fusions, expression subtypes, immune signatures |

| Proteomics | Mass spectrometry, Multiplexed immunoassays | Quantifies functional effectors | Drug target engagement, signaling networks |

| Metabolomics | LC-MS, NMR spectroscopy | Reveals biochemical endpoints | Metabolic vulnerabilities, therapy response |

| Epigenomics | ChIP-seq, ATAC-seq, Methylation arrays | Identifies regulatory mechanisms | Biomarker discovery, therapy resistance |

| Single-cell Multi-omics | CITE-seq, SPRI-te | Resolves cellular heterogeneity | Tumor microenvironments, rare cell detection |

Single-Cell Multi-Omics: A Paradigm Shift

Single-cell multi-omics technologies represent a transformative approach that simultaneously profiles multiple molecular layers (genome, transcriptome, proteome, epigenome) within individual cells [7] [5]. This enables:

- Direct Observation of Genotype-Phenotype Relationships: Simultaneous measurement of DNA mutations, RNA expression, and protein abundance in the same cell moves beyond statistical correlation to establish causal relationships [5].

- High-Resolution Cellular Cartography: Identification of rare cell populations (e.g., cancer stem cells, drug-resistant subclones) that drive disease progression but are undetectable by bulk NGS [7].

- Characterization of Tumor Microenvironment: Unbiased dissection of cellular ecosystems within tumors, including immune cell composition and stromal interactions [7].

Single-cell multi-omics reveals tumor heterogeneity

Experimental Protocols for Multi-Omics Integration

Protocol 1: Integrated Genomic-Transcriptomic Analysis for Cancer Subtyping

This protocol outlines a standardized workflow for integrating DNA and RNA sequencing data to identify molecular subtypes with distinct clinical outcomes and therapeutic vulnerabilities.

Materials and Reagents:

- Fresh-frozen or FFPE tumor tissue with matched normal sample

- DNA extraction kit (e.g., QIAamp DNA Mini Kit)

- RNA extraction kit (e.g., RNeasy Mini Kit) with DNase treatment

- Illumina TruSight Oncology 500 or similar targeted sequencing panel

- Illumina TruSeq RNA Exome or similar RNA sequencing library prep kit

- Illumina sequencing platform (NovaSeq 6000, MiSeq, or NextSeq)

Procedure:

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Co-extract high-quality DNA and RNA from the same tumor sample, ensuring minimal degradation (RNA Integrity Number >7.0).

- DNA Library Preparation: Prepare sequencing libraries using 50-100ng of DNA according to targeted panel specifications. Include unique molecular identifiers to minimize sequencing artifacts.

- RNA Library Preparation: Prepare RNA sequencing libraries using 100ng-1μg of total RNA. Perform ribosomal RNA depletion rather than poly-A selection to capture non-coding transcripts.

- Sequencing: Sequence DNA libraries to a minimum depth of 500x and RNA libraries to a minimum of 50 million reads per sample.

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Process DNA sequencing data through established variant calling pipelines (e.g., GATK Best Practices)

- Analyze RNA sequencing data using alignment-based (STAR) or alignment-free (Salmon) approaches

- Integrate datasets to identify:

- Somatic mutations with corresponding expression changes

- Gene fusions validated at both DNA and RNA levels

- Mutational signatures correlated with transcriptional programs

Quality Control Metrics:

- DNA sequencing: >80% of targets covered at 100x

- RNA sequencing: >70% of reads uniquely mapped

- Cross-validation: >90% concordance for fusion variants detected by both assays

Protocol 2: Single-Cell Multi-Omics for Tumor Heterogeneity Mapping

This protocol describes a comprehensive approach for simultaneous profiling of DNA mutations, RNA expression, and protein markers in individual cells from tumor specimens.

Materials and Reagents:

- Fresh tumor tissue dissociated into single-cell suspension

- Viability stain (e.g., DAPI or propidium iodide)

- Single-cell multi-omics platform (10x Genomics Multiome, Mission Bio Tapestri, or similar)

- Feature barcoding antibodies (TotalSeq or similar)

- Cell hashing antibodies for sample multiplexing

- Appropriate single-cell library preparation reagents

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Dissociate tumor tissue to single cells, ensuring >90% viability. Count cells and adjust concentration to platform-specific requirements.

- Cell Staining: Incubate cells with feature barcoding antibodies for surface protein detection and cell hashing antibodies for sample multiplexing.

- Single-Cell Partitioning: Load cells onto appropriate microfluidic device according to manufacturer specifications.

- Library Preparation: Perform simultaneous DNA barcoding, RNA reverse transcription, and protein barcode tagging in partitioned droplets or wells.

- Sequencing: Sequence libraries on appropriate Illumina platform with read parameters adjusted for each data type.

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Process data using integrated pipelines (Cell Ranger, Seurat, Signac)

- Perform quality control to remove doublets and low-quality cells

- Integrate modalities to:

- Associate copy number variations with gene expression programs

- Link surface protein expression with transcriptional states

- Identify subclones with distinct genotype-phenotype relationships

Quality Control Metrics:

- Cell recovery: >5,000 high-quality cells per sample

- Doublet rate: <5% of captured cells

- Gene detection: >1,000 genes per cell (RNA)

- SNP concordance: >95% with bulk sequencing

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table: Key Research Reagents for Multi-Omics Experiments

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| DNase/RNase-free magnetic beads | Nucleic acid purification and size selection | Enable simultaneous DNA/RNA extraction; critical for preserving labile RNA species |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Tagging individual molecules to reduce PCR duplicates | Essential for accurate quantification in both DNA and RNA sequencing |

| Multiplexed barcoding antibodies | Tagging cells for protein detection alongside transcriptomics | Enable CITE-seq approaches; require titration for optimal signal-to-noise |

| Cell hashing antibodies | Sample multiplexing in single-cell experiments | Allow pooling of multiple samples; reduce batch effects and costs |

| Template switching oligos | Full-length cDNA synthesis in single-cell RNA-seq | Critical for capturing 5' end information and improving transcript coverage |

| Chromatin crosslinking reagents | Preserving protein-DNA interactions for epigenomics | Enable ChIP-seq and related assays; require optimization of crosslinking time |

| Viability dyes | Distinguishing live/dead cells in single-cell assays | Critical for ensuring high-quality data; must be compatible with downstream library prep |

| Nucleic acid stability reagents | Preserving samples during storage and transport | Essential for clinical samples with delayed processing; maintain RNA integrity |

The limitations of single-omics NGS approaches necessitate a fundamental shift toward integrated multi-omics frameworks in oncology research. While NGS provides an essential foundation for understanding cancer genetics, it cannot fully capture the complex, dynamic molecular interactions that drive tumor behavior, therapeutic response, and resistance mechanisms. The experimental protocols and methodologies outlined in this application note provide a roadmap for researchers to transcend these limitations through systematic integration of genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and epigenomic data layers.

Emerging technologies—particularly single-cell multi-omics and artificial intelligence-driven integration platforms—are poised to further accelerate this paradigm shift [4] [7]. As these approaches mature and become more accessible, they will increasingly enable researchers to move from correlative observations to causal understandings of cancer biology, ultimately supporting the development of more effective, personalized cancer therapies.

The advent of large-scale molecular profiling methods has fundamentally transformed cancer research, shifting the paradigm from single-omics investigations to integrative multi-omics analyses [3]. Biological systems operate through complex, interconnected layers—including the genome, transcriptome, proteome, and metabolome—through which genetic information flows to shape observable traits [3]. While single-omics approaches have provided valuable insights, they inherently fail to capture the complex interactions between different molecular layers that drive cancer pathogenesis [9] [10]. Integrative multi-omics frameworks now provide a holistic view of the molecular landscape of cancer, offering deeper insights into tumor biology, disease mechanisms, and therapeutic opportunities [3] [11].

The integration of next-generation sequencing (NGS) with other omics technologies has become particularly transformative in oncology [12]. NGS enables comprehensive genomic and transcriptomic profiling, identifying driver mutations, structural variations, and gene expression patterns across cancer types [12]. When combined with proteomic and metabolomic data, these technologies facilitate the construction of detailed models that connect genetic alterations to functional consequences, thereby refining cancer classification, prognostic stratification, and therapeutic decision-making [11] [9]. This Application Note provides a structured framework for designing, executing, and interpreting multi-omics studies in oncology research, with specific protocols and analytical workflows for integrating NGS with complementary omics platforms.

Omics Technologies: Core Components and Applications

Each omics layer provides distinct yet complementary insights into tumor biology. The table below summarizes the core components, technological platforms, and applications of the four major omics fields in cancer research.

Table 1: Core Omics Technologies in Cancer Research

| Omics Layer | Analytical Focus | Key Technologies | Primary Applications in Oncology | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genomics | DNA sequences and variations | Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS), Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) [11] | Identification of driver mutations, copy number variations (CNVs), structural variants [3] | Comprehensive view of genetic variation; foundation for personalized medicine [3] | Does not account for gene expression or environmental influences [3] |

| Transcriptomics | RNA expression and regulation | RNA sequencing, single-cell RNA-seq, microarrays [11] | Gene expression profiling, pathway activity analysis, biomarker discovery [3] [11] | Captures dynamic gene expression changes; reveals regulatory mechanisms [3] | RNA instability; snapshot view not reflecting long-term changes [3] |

| Proteomics | Protein abundance, modifications, interactions | Mass spectrometry, liquid chromatography-MS (LC-MS), reverse-phase protein arrays [11] [13] | Biomarker discovery, drug target identification, signaling pathway analysis [3] [13] | Directly measures functional effectors; identifies post-translational modifications [3] | Complex structures and dynamic ranges; difficult quantification [3] |

| Metabolomics | Small molecule metabolites and metabolic pathways | LC-MS, gas chromatography-MS, mass spectrometry imaging [11] | Disease diagnosis, metabolic pathway analysis, treatment response monitoring [3] | Direct link to phenotype; captures real-time physiological status [3] | Highly dynamic; limited reference databases; technical variability [3] |

Quantitative Proteomics Technologies

Within integrated workflows, proteomics requires specific methodological considerations for quantitative accuracy. The table below compares major quantitative proteomics approaches.

Table 2: Quantitative Proteomics Methodologies

| Method | Principle | Throughput | Quantitative Accuracy | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SILAC (Stable Isotope Labeling with Amino acids in Cell culture) [13] | Metabolic labeling with stable isotopes during cell culture | Medium | High (minimizes experimental variability) | Cell line studies; protein turnover experiments |

| TMT (Tandem Mass Tagging) [13] | Isobaric chemical labeling of peptides | High | High in MS2 mode | Multi-sample comparisons; phosphoproteomics |

| Label-Free Quantification [13] | Comparison of peptide signal intensities or spectral counts | High | Medium (requires rigorous normalization) | Large cohort studies; clinical samples |

| MRM (Multiple Reaction Monitoring) [13] | Targeted detection of specific peptides | Low | High | Validation of candidate biomarkers |

Integrated Experimental Design and Workflows

Multi-Omics Integration Strategies

The strategic integration of omics data can be implemented through different computational approaches, each with distinct advantages and considerations:

- Horizontal Integration (P-integration): Combines multiple studies of the same molecular level to increase sample size and statistical power [14]. This approach is particularly valuable for meta-analyses across different patient cohorts or research centers.

- Vertical Integration (N-integration): Incorporates different omics layers from the same biological samples to build comprehensive models of biological flow from genotype to phenotype [14] [9]. This approach is ideal for connecting genomic alterations to their functional consequences through transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic profiling.

- Temporal Integration: Analyzes omics data collected across multiple timepoints to capture dynamic changes during disease progression or therapeutic intervention [9].

The following diagram illustrates the strategic workflow for vertical integration of multi-omics data in oncology research:

Protocol: Integrated Multi-Omics Analysis for Tumor Biomarker Discovery

Objective: Identify molecular subtypes and biomarkers in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) through integrated genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic profiling.

Sample Requirements:

- Fresh frozen tumor tissue (≥100mg) and matched normal adjacent tissue

- Blood samples (for germline DNA control)

- Minimum sample size: 30 patients per cohort for statistical power

Experimental Workflow:

Step 1: Nucleic Acid Extraction

- Extract DNA using magnetic bead-based kits (e.g., QIAamp DNA Mini Kit)

- Extract total RNA with column-based purification (e.g., RNeasy Mini Kit)

- Quality control: DNA integrity number (DIN) ≥7.0, RNA integrity number (RIN) ≥8.0

Step 2: Next-Generation Sequencing

- Whole Exome Sequencing: Fragment DNA (150-200bp), hybrid capture using Illumina Nextera Flex, sequence on Illumina NovaSeq (150bp paired-end, 100x coverage)

- RNA Sequencing: Poly-A selection, library preparation with strand specificity, sequence on Illumina platform (50M reads/sample)

Step 3: Proteomic Profiling

- Protein extraction using urea/thiourea buffer

- Trypsin digestion with filter-aided sample preparation (FASP)

- TMT 16-plex labeling for quantitative comparison

- LC-MS/MS analysis on Orbitrap Eclipse mass spectrometer

Step 4: Data Processing and Quality Control

- Genomics: BWA-MEM alignment, GATK variant calling, MutSigCV for mutation significance

- Transcriptomics: STAR alignment, DESeq2 for differential expression

- Proteomics: MaxQuant search, normalization using median centering

Analytical Frameworks and Computational Tools

Data Integration Methodologies

The successful integration of multi-omics data requires sophisticated computational approaches that can handle high-dimensional, heterogeneous datasets:

- Statistical and Correlation-Based Methods: Pearson's or Spearman's correlation analysis to assess relationships between omics datasets; Weighted Gene Correlation Network Analysis (WGCNA) to identify clusters of co-expressed genes [15].

- Multivariate Methods: Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression; Multi-Omics Factor Analysis (MOFA) to infer latent factors that capture shared and specific sources of variability across omics layers [15] [10].

- Machine Learning and AI: Regularized methods (LASSO, elastic net) for feature selection; graph neural networks for patient stratification; deep learning models for subtype classification [11] [14] [10].

The following diagram illustrates the analytical framework for multi-omics data integration:

Protocol: Computational Analysis of Integrated Omics Data

Objective: Implement a comprehensive analytical pipeline for multi-omics data integration and biomarker identification.

Software Requirements:

- R Statistical Environment (v4.2+) with packages: moIntegrate, mixOmics, WGCNA, iCluster

- Python (v3.9+) with scikit-learn, PyTorch, and Scanpy

- Bioinformatics tools: BWA, GATK, STAR, MaxQuant

Analytical Procedure:

Step 1: Data Preprocessing and Quality Control

- Perform platform-specific normalization: RPKM for transcriptomics, median centering for proteomics

- Apply batch correction using ComBat or remove unwanted variation (RUV) methods

- Filter low-quality features: Remove genes with <10 reads in >90% samples; remove proteins with >20% missing values

Step 2: Horizontal Integration within Omics Layers

- Use Similarity Network Fusion (SNF) to combine multiple genomic features (mutations, CNVs)

- Apply multi-block PLS to integrate different proteomic datasets (global proteome, phosphoproteome)

Step 3: Vertical Integration across Omics Layers

- Implement MOFA+ to decompose multi-omics variation into latent factors

- Build association networks using xMWAS with correlation threshold |r| > 0.8 and FDR < 0.05

- Perform multi-omics clustering using iCluster with k=3-5 molecular subtypes

Step 4: Biomarker Identification and Validation

- Apply LASSO-Cox regression for survival-associated feature selection

- Validate biomarkers in independent datasets (e.g., TCGA, CPTAC)

- Perform functional enrichment analysis using GSEA and pathway databases (KEGG, Reactome)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Successful multi-omics studies require carefully selected reagents, platforms, and computational resources. The following table details essential components for establishing a robust multi-omics workflow.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Multi-Omics Studies

| Category | Product/Platform | Specific Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction | QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen) | High-quality DNA for WGS/WES | Magnetic bead-based purification; DIN ≥7.0 |

| RNA Isolation | RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) | Intact RNA for transcriptomics | Column-based purification; RIN ≥8.0 |

| NGS Library Prep | Illumina DNA Prep | Whole genome/exome sequencing | Hybrid capture-based; compatible with FFPE |

| NGS Platform | Illumina NovaSeq 6000 | High-throughput sequencing | 150bp paired-end; 100x coverage for WES |

| Proteomics Sample Prep | TMTpro 16-plex (Thermo) | Multiplexed quantitative proteomics | 16-sample multiplexing; reduces batch effects |

| Mass Spectrometry | Orbitrap Eclipse (Thermo) | High-resolution proteomics | Tribrid architecture; TMT quantification |

| Chromatography | Vanquish UHPLC (Thermo) | Peptide separation pre-MS | Nanoflow capabilities; minimal carryover |

| Data Analysis | IntegrAO | Multi-omics data integration | Graph neural networks; handles missing data |

| Visualization | Cytoscape | Biological network visualization | Plugin architecture; multi-omics extensions |

Concluding Remarks

Integrative multi-omics approaches have fundamentally transformed oncology research by providing unprecedented insights into the molecular intricacies of cancer [3]. The strategic combination of NGS with proteomic and metabolomic technologies enables the construction of comprehensive models that connect genetic alterations to functional consequences and phenotypic manifestations [11] [9]. While significant challenges remain in data integration, standardization, and interpretation, continued development of computational frameworks and analytical pipelines is rapidly advancing the field [14] [15].

The protocols and frameworks outlined in this Application Note provide a structured approach for implementing multi-omics studies in cancer research. As these technologies continue to evolve—particularly with the emergence of single-cell and spatial omics platforms—they hold unprecedented potential to unravel the complex molecular architecture of tumors, identify novel therapeutic targets, and ultimately advance personalized cancer treatment [11] [16] [9]. By adopting standardized workflows and robust analytical practices, researchers can maximize the biological insights gained from these powerful technologies and accelerate progress in precision oncology.

In modern oncology research, the journey from a static genetic blueprint to a dynamic functional phenotype is governed by the complex interplay of multiple molecular layers. The central dogma of biology, which posits a linear flow of information from DNA to RNA to protein, is insufficient to capture the intricate regulatory networks that underlie cancer biology [17]. Instead, a multi-omics approach that integrates genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, epigenomics, and metabolomics provides a holistic framework for understanding how these layers interconnect to drive oncogenesis, tumor progression, and treatment response [3] [18].

The transition in perspective from a "genetic blueprint" to a dynamic genotype-phenotype mapping concept represents a fundamental shift in biological understanding. Traditional metaphors of genetic programs have been replaced with algorithmic approaches that recognize the complex, non-linear relationships between genetic information and phenotypic expression [17]. In oncology, this paradigm shift is particularly crucial, as tumors represent complex ecosystems where genomic alterations manifest through dysregulated molecular networks across multiple biological layers [3] [19].

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies serve as the foundational engine for dissecting these complex relationships, generating massive datasets that capture molecular information at unprecedented resolution and scale [20]. However, the true power of NGS emerges only when these data are integrated with other omics layers to map the complete pathway from genetic variant to functional consequence in cancer biology [18] [19].

The Multi-Omics Landscape in Oncology

Defining the Omics Layers

Biological systems operate through complex, interconnected layers including the genome, transcriptome, proteome, metabolome, microbiome, and lipidome. Genetic information flows through these layers to shape observable traits, and elucidating the genetic basis of complex phenotypes demands an analytical framework that captures these dynamic, multi-layered interactions [3]. Each omics layer provides distinct yet complementary insights into tumor biology, collectively enabling researchers to reconstruct the complete molecular circuitry of cancer.

Table 1: The Multi-Omics Components and Their Applications in Oncology

| Omics Component | Description | Key Applications in Oncology | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomics | Study of the complete set of DNA, including all genes, focusing on sequencing, structure, function, and evolution [3]. | Identification of driver mutations, copy number variations, and single-nucleotide polymorphisms; cancer risk assessment; pharmacogenomics [3]. | Does not account for gene expression or environmental influence; large data volume and complexity; ethical concerns regarding genetic data [3]. |

| Transcriptomics | Analysis of RNA transcripts produced by the genome under specific circumstances or in specific cells [3]. | Gene expression profiling; biomarker discovery; understanding drug response mechanisms; tumor subtyping [3] [19]. | RNA is less stable than DNA; provides snapshot view, not long-term; requires complex bioinformatics tools [3]. |

| Proteomics | Study of the structure and function of proteins, the main functional products of gene expression [3]. | Direct measurement of protein levels and modifications; drug target identification; linking genotype to phenotype [3] [19]. | Proteins have complex structures and dynamic ranges; proteome is much larger than genome; difficult quantification and standardization [3]. |

| Epigenomics | Study of heritable changes in gene expression not involving changes to the underlying DNA sequence [3]. | Understanding gene regulation beyond DNA sequence; identifying epigenetic therapy targets; connecting environment and gene expression [3]. | Epigenetic changes are tissue-specific and dynamic; complex data interpretation; influenced by external factors [3]. |

| Metabolomics | Comprehensive analysis of metabolites within a biological sample, reflecting the biochemical activity and state [3]. | Provides insight into metabolic pathways and their regulation; direct link to phenotype; captures real-time physiological status [3]. | Metabolome is highly dynamic and influenced by many factors; limited reference databases; technical variability issues [3]. |

From Genetic Variation to Phenotypic Manifestation

In cancer systems, genetic variations serve as the initial blueprint but do not determine phenotypic outcomes in isolation. These variations operate through hierarchical biological layers that ultimately manifest as clinical phenotypes:

Genetic Variations in Cancer:

- Driver mutations provide growth advantage and are directly involved in oncogenesis, typically occurring in genes regulating cell growth, apoptosis, and DNA repair [3]. For example, TP53 mutations occur in approximately 50% of all human cancers [3].

- Copy number variations (CNVs) involve duplications or deletions of DNA regions, altering gene dosage. HER2 amplification in approximately 20% of breast cancers leads to protein overexpression associated with aggressive tumor behavior [3].

- Single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) can affect cancer susceptibility and drug response. SNPs in BRCA1 and BRCA2 significantly increase breast and ovarian cancer risk, while SNPs in drug metabolism enzymes influence chemotherapy efficacy and toxicity [3].

The transition from these genetic variants to phenotypic expression involves complex, non-linear interactions across omics layers. Alberch's concept of genotype-phenotype (G→P) mapping provides a framework for understanding these relationships, emphasizing that the same phenotype may arise from different genetic combinations, and that phenotypic stability depends on a population's position in the developmental parameter space [17].

Methodological Framework for Multi-Omics Integration

Experimental Design and Data Generation

Robust multi-omics studies in oncology require careful experimental design to ensure data quality and integration potential. The following protocols outline standardized approaches for generating and integrating multi-omics data from cancer specimens:

Protocol 3.1.1: Sample Preparation for Multi-Omics Analysis

- Tissue Collection and Processing: Obtain tumor tissue specimens via biopsy or surgical resection. For solid tumors, use formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues or fresh frozen specimens based on analytical requirements [21].

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Isolate genomic DNA using validated kits (e.g., QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue kit). Ensure DNA concentration of at least 20 ng with A260/A280 ratio between 1.7-2.2 for library generation [21].

- Quality Control: Assess DNA purity using NanoDrop Spectrophotometer and library size/quantity using Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer system. Acceptable library characteristics: 250-400 bp size, concentration ≥ 2nμ [21].

Protocol 3.1.2: Next-Generation Sequencing Workflow

- Library Preparation: Use hybrid capture method for DNA library preparation and target enrichment according to Illumina's standard protocol with Agilent SureSelectXT Target Enrichment Kit [21].

- Sequencing: Perform sequencing on platforms such as Illumina NextSeq 550Dx or NovaSeq X. For targeted panels (e.g., 544-gene cancer panels), ensure minimum coverage of 100x with average depth >500x [20] [21].

- Automation Integration: Implement automated NGS workflows using systems like Biomek i3 Benchtop Liquid Handler to enhance reproducibility and throughput for targeted sequencing assays including Archer FUSIONPlex and VARIANTPlex panels [22].

Protocol 3.1.3: Multi-Omics Data Generation

- Transcriptomics: Conduct RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) using Illumina platforms. For single-cell analyses, employ 10× Genomics Chromium system [19] [20].

- Proteomics: Perform mass spectrometry-based profiling using time-of-flight (TOF) or Orbitrap instruments. Prepare samples using tryptic digestion and label-free or TMT labeling approaches [19].

- Metabolomics: Utilize nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy or mass spectrometry with liquid or gas chromatography for metabolite profiling [19].

Computational Integration Strategies

The complexity and volume of multi-omics data necessitate sophisticated computational approaches for integration and interpretation. The following protocols detail established methodologies for multi-omics data integration:

Protocol 3.2.1: Data Preprocessing and Normalization

- Genomic Data Processing: Align sequencing reads to reference genome (hg19/GRCh38) using BWA or STAR aligners. Perform variant calling with Mutect2 for SNVs/indels and CNVkit for copy number variations [21].

- RNA-Seq Analysis: Process transcriptomic data using Ensembl or Galaxy pipelines. Normalize expression data using TPM or FPKM methods [19].

- Proteomics Data Processing: Analyze mass spectrometry data with MaxQuant. Normalize protein abundances using variance-stabilizing normalization [19].

- Batch Effect Correction: Implement ComBat or removeUnwantedVariation (RUV) methods to address technical variability across batches [19].

Protocol 3.2.2: Multi-Omics Integration Algorithms

- Similarity-Based Integration: Identify common patterns across omics datasets using:

- Correlation analysis to evaluate relationships between different omics levels

- Clustering algorithms (hierarchical clustering, k-means) to group similar data points

- Similarity Network Fusion (SNF) to construct integrated similarity networks [19]

- Difference-Based Integration: Detect unique features across omics layers using:

- Differential expression analysis (DESeq2, limma) to identify significant changes between conditions

- Variance decomposition to partition variance components attributable to different omics types

- Feature selection methods (LASSO, Random Forests) to select most relevant features [19]

- Multi-Omics Factor Analysis (MOFA): Apply this unsupervised Bayesian factor analysis to identify latent factors responsible for variation across multiple omics datasets [19].

- Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA): Implement sparse CCA to identify linear relationships between two or more omics datasets [19].

Protocol 3.2.3: Network Biology and Pathway Analysis

- Network Construction: Build molecular interaction networks using OmicsNet or NetworkAnalyst, integrating genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics data [19].

- Pathway Enrichment: Perform functional enrichment analysis using KEGG, Reactome, or GO databases to identify significantly altered pathways [3].

- Regulatory Network Inference: Reconstruct gene regulatory networks by integrating transcription factor binding data (from ChIP-Seq) with transcriptomic profiles [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Successful multi-omics studies require carefully selected reagents, platforms, and computational tools. The following table catalogs essential solutions for oncology-focused multi-omics research:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Multi-Omics Oncology Studies

| Category | Product/Platform | Specific Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| NGS Assays | Archer FUSIONPlex | Targeted RNA sequencing for gene fusion detection | Identifies known and novel fusion transcripts; optimized for FFPE samples [22] |

| VARIANTPlex | Targeted DNA sequencing for variant detection | Comprehensive coverage of cancer-related genes; enables somatic and germline variant calling [22] | |

| xGen Hybrid Capture | Whole exome and custom target enrichment | High uniformity and coverage; compatible with low-input samples [22] | |

| Automation Platforms | Biomek i3 Benchtop Liquid Handler | Automated NGS library preparation | Compact footprint; on-deck thermocycling; rapid protocol development [22] |

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina NovaSeq X | High-throughput sequencing | Unmatched speed and data output for large-scale projects [20] |

| Oxford Nanopore Technologies | Long-read sequencing | Extended read length; real-time, portable sequencing [20] | |

| Computational Tools | Ensembl | Genomic annotation and analysis | Comprehensive genomic data; genome assembly and variant calling [19] |

| Galaxy | Bioinformatics workflows | User-friendly platform for multi-omics analysis [19] | |

| OmicsNet | Multi-omics network visualization | Integration of genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics data [19] | |

| NetworkAnalyst | Network-based visual analysis | Data filtering, normalization, statistical analysis, and network visualization [19] | |

| AI/Machine Learning | DeepVariant | Variant calling | Deep learning-based variant identification with high accuracy [20] |

| MOFA | Multi-omics factor analysis | Unsupervised integration of multiple omics datasets [19] |

Case Study: Clinical Implementation of Multi-Omics in Oncology

Real-World Clinical NGS Implementation

A recent study demonstrates the successful implementation of NGS-based tumor profiling in routine clinical practice. The following protocol and results highlight the practical application of multi-omics approaches in oncology:

Protocol 5.1.1: Clinical NGS Testing Workflow

- Patient Selection and Sample Collection: Include patients with advanced solid tumors. Use stored FFPE tumor specimens with proper tumor cellularity [21].

- NGS Testing: Implement targeted sequencing panels (e.g., SNUBH Pan-Cancer v2.0 covering 544 genes). Sequence on Illumina NextSeq 550Dx platform [21].

- Variant Classification: Tier variants according to Association for Molecular Pathology guidelines:

- Tier I: Variants of strong clinical significance (FDA-approved or guideline-recommended therapies)

- Tier II: Variants of potential clinical significance (investigational therapies) [21]

- Therapeutic Matching: Identify genomically-matched therapies based on novel information from NGS testing, excluding alterations identifiable through conventional molecular tests [21].

Results and Clinical Outcomes:

- Detection Rate: Among 990 patients with advanced solid tumors, 26.0% harbored tier I variants with strong clinical significance, while 86.8% carried tier II variants with potential clinical significance [21].

- Therapeutic Impact: 13.7% of patients with tier I variants received NGS-based therapy, with particularly high implementation in thyroid cancer (28.6%), skin cancer (25.0%), gynecologic cancer (10.8%), and lung cancer (10.7%) [21].

- Treatment Response: Among 32 patients with measurable lesions who received NGS-based therapy, 37.5% achieved partial response and 34.4% achieved stable disease, demonstrating the clinical utility of molecular profiling-guided therapy [21].

Integrative Multi-Omics Analysis in Cancer Research

Protocol 5.2.1: Comprehensive Multi-Omics Tumor Profiling

- Sample Collection and Processing: Collect matched tumor and normal tissues from cancer patients. Process for parallel genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and epigenomic analyses [3] [19].

- Data Generation:

- Data Integration: Apply multi-omics factor analysis (MOFA) to identify latent factors that drive variation across omics layers [19].

- Network Biology Analysis: Construct integrated molecular networks using tools like OmicsNet to identify key regulatory hubs and dysregulated pathways [19].

Key Insights from Integrative Analyses:

- Regulatory Cascades: Multi-omics approaches reveal how genomic alterations (e.g., TP53 mutations) propagate through transcriptomic and proteomic layers to activate specific oncogenic pathways [3].

- Therapeutic Resistance Mechanisms: Integrated analyses identify compensatory mechanisms across omics layers that mediate resistance to targeted therapies, enabling development of combination strategies [3] [19].

- Tumor Heterogeneity: Single-cell multi-omics technologies resolve intra-tumor heterogeneity by simultaneously profiling genomic, transcriptomic, and epigenomic features of individual cells [20] [23].

Future Perspectives and Concluding Remarks

The integration of NGS with multi-omics data represents the forefront of oncology research, transforming our understanding of cancer biology and accelerating precision medicine. The field is rapidly evolving with several emerging trends:

Emerging Technologies and Approaches:

- Single-Cell Multi-Omics: Technologies enabling simultaneous measurement of genomic, transcriptomic, epigenomic, and proteomic features at single-cell resolution are revealing unprecedented insights into tumor heterogeneity and cellular ecosystems [20] [23].

- Spatial Omics: Methods that preserve spatial context in tissue specimens are mapping molecular features within tumor architecture, connecting cellular positioning to functional phenotypes [20].

- Artificial Intelligence Integration: Advanced machine learning and deep learning approaches are enhancing our ability to extract biologically meaningful patterns from complex multi-omics datasets, enabling predictive modeling of therapeutic response and resistance [20] [24].

- Longitudinal Monitoring: Multi-omics profiling of liquid biopsies enables dynamic monitoring of tumor evolution and treatment response through non-invasive approaches [18].

The journey from genetic blueprint to functional phenotype in oncology requires navigating the complex interplay between multiple molecular layers. Through integrated multi-omics approaches, researchers can now reconstruct the complete molecular circuitry of cancer, revealing how genomic alterations manifest as functional phenotypes through dysregulated networks across transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic layers. As these technologies continue to mature and computational integration strategies become more sophisticated, multi-omics approaches will increasingly guide clinical decision-making and therapeutic development, ultimately improving outcomes for cancer patients.

The molecular complexity of cancer is driven by a spectrum of genomic alterations that disrupt critical cellular signaling pathways. Single nucleotide variants (SNVs), copy number variations (CNVs), and gene fusions represent three fundamental classes of such drivers, each contributing uniquely to oncogenesis, therapeutic response, and resistance mechanisms. The integration of next-generation sequencing (NGS) with other omics data—including transcriptomics, proteomics, and epigenomics—has revolutionized our ability to detect these alterations and understand their functional consequences within the broader context of cellular systems [4]. This multi-omics approach moves beyond single-layer analysis to capture the interconnected biological networks that drive cancer progression, enabling more precise diagnostic stratification and targeted therapeutic intervention [11].

In contemporary precision oncology, identifying these genomic drivers is not merely descriptive but foundational for treatment decisions. For instance, specific SNVs can dictate sensitivity to targeted inhibitors, CNVs can amplify oncogenes or delete tumor suppressors, and gene fusions can create constitutively active kinases that become primary therapeutic targets [4] [25]. The functional characterization of these variants, therefore, becomes a critical step in translating genomic findings into clinical action. This document provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols for the study of SNVs, CNVs, and fusions, framed within the integrative framework of modern multi-omics oncology research.

Single Nucleotide Variants (SNVs)

Functional Impact and Predictive Algorithms

Single nucleotide variants (SNVs), particularly missense mutations that result in amino acid substitutions, can significantly alter protein function and drive oncogenesis. Prioritizing which SNVs have genuine functional impact is a central challenge in cancer genomics. Computational prediction methods have been developed to address this, leveraging features such as sequence conservation, allele frequency, and structural parameters [26].

The Disease-related Variant Annotation (DVA) method represents a recent advancement in this field. It employs a comprehensive feature set, including sequence conservation, allele frequency in different populations, and protein-protein interaction (PPI) network features transformed via graph embedding [26]. This feature set is used to train a random forest model, which has demonstrated superior performance compared to existing tools. As shown in Table 1, DVA achieved an Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUROC) of 0.979 on a dataset of somatic cancer missense variants, substantially outperforming 14 other state-of-the-art methods, including ClinPred (AUROC: 0.84) and REVEL (AUROC: 0.915) [26].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of SNV Functional Impact Prediction Tools on Somatic Cancer Variants

| Prediction Method | AUROC | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DVA | 0.979 | 0.941 | 0.957 | 0.924 | 0.940 |

| ClinPred | 0.840 | 0.772 | 0.799 | 0.724 | 0.759 |

| REVEL | 0.915 | 0.843 | 0.869 | 0.808 | 0.837 |

| CADD | 0.851 | 0.782 | 0.811 | 0.736 | 0.772 |

| FATHMM-MKL | 0.777 | 0.709 | 0.743 | 0.641 | 0.688 |

| SIFT | 0.821 | 0.753 | 0.788 | 0.692 | 0.737 |

Application Note: Deep Mutational Scanning for CHEK2

For high-throughput functional assessment of SNVs, Deep Mutational Scanning (DMS) provides an empirical approach. A seminal study applied DMS to the checkpoint kinase gene CHEK2, a gene in which loss-of-function mutations are associated with increased risk of breast and other cancers [27]. Researchers tested nearly all of the 4,887 possible SNVs in the CHEK2 open reading frame for their ability to complement the function of the yeast ortholog, RAD53 [27].

The protocol involved:

- Generation of a Saturation Mutagenesis Library: Creating a comprehensive library of CHEK2 variants.

- Functional Complementation in Yeast: Introducing the variant library into RAD53-deficient yeast strains.

- Selection and Sequencing: Applying selective pressure and using high-throughput sequencing to quantify the relative abundance of each variant before and after selection.

- Functional Scoring: Calculating enrichment scores to classify variants as functionally "tolerated" or "damaging."

This study successfully classified 770 non-synonymous changes as damaging to protein function and 2,417 as tolerated, providing a critical resource for interpreting variants of uncertain significance (VUS) found in clinical screenings [27].

Figure 1: DMS Workflow for CHEK2 SNV Functional Characterization

Research Reagent Solutions for SNV Analysis

Table 2: Key Reagents for SNV Functional Studies

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Application | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Saturation Mutagenesis Library | Provides comprehensive coverage of SNVs for a target gene. | CHEK2 ORF library of 4,887 SNVs [27]. |

| Yeast Complementation System | In vivo functional assay for genes with yeast orthologs. | RAD53-deficient S. cerevisiae for CHEK2 testing [27]. |

| Prediction Software (DVA) | Computationally predicts pathogenicity of missense variants. | Integrates conservation, allele frequency, and PPI features [26]. |

| dbNSFP Database | Aggregates scores from multiple prediction algorithms. | Facilitates comparison and meta-analysis of SNV impact [26]. |

Copy Number Variations (CNVs)

Biology and Analytical Frameworks

Copy number variations (CNVs) are a form of structural variation resulting in the gain or loss of genomic DNA, which can lead to the amplification of oncogenes or deletion of tumor suppressor genes [28]. In cancer research, CNV analysis is crucial for identifying driver alterations, understanding tumor evolution, and identifying therapeutic targets.

The analytical process of CNV calling involves comparing sequencing data from a sample to a reference genome to identify regions with statistically significant differences in read depth [28]. Key considerations for CNV analysis include:

- Sequencing Platform and Coverage: Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) typically provides more uniform coverage and superior sensitivity/specificity compared to whole-exome sequencing (WES) or targeted panels [28].

- Sample Purity and Ploidy: Tumor purity (the proportion of cancer cells in a sample) and genome ploidy (the number of chromosome sets) significantly impact the accuracy of CNV calls and must be accounted for in analytical models [28].

- Algorithm Selection: Multiple algorithms exist, each with strengths and weaknesses. A benchmarking study highlighted several common CNV callers, which are summarized in Table 3 [28].

Table 3: Common CNV Calling Algorithms for NGS Data in Cancer Research

| Algorithm | Primary Application | Key Features / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| ASCAT-NGS | WGS | Allele-specific copy number analysis of tumors; used in NCI's GDC platform [28]. |

| CNVkit | WES, WGS | Uses a hybrid capture-based approach to model biases and smooth data [28]. |

| FACETS | WGS, WES, Panels | Estimates fraction and allele-specific copy numbers, robust for tumor-normal pairs [28]. |

| DRAGEN | WGS, WES | Scalable, hardware-accelerated platform for rapid variant calling [28]. |

| HATCHet | Multi-sample WGS | Jointly analyzes multiple tumor samples to infer allele-specific copy numbers [28]. |

Application Note: CNVs in Pediatric Cancers with Birth Defects

CNVs play a significant role in the development of pediatric cancers, particularly in children with serious birth defects (BDs). A study performing whole-genome sequencing (WGS) on 1,556 individuals revealed that roughly half of the children with both a BD and cancer possessed CNVs that were not identified in BD-only or healthy individuals [29]. These CNVs were heterogenous but showed functional enrichment in specific biological pathways, such as deletions affecting genes with neurological functions and duplications of immune response genes [29]. This highlights the importance of CNV analysis in uncovering the underlying genetic mechanisms linking developmental disorders and cancer.

The recommended protocol for such an investigation includes:

- Sample Collection: Blood-derived DNA from well-phenotyped cohorts (e.g., BD with cancer, BD-only, healthy controls).

- Whole-Genome Sequencing: Conduct high-coverage WGS to ensure uniform coverage for sensitive CNV detection.

- CNV Calling and Filtering: Utilize a consensus approach with multiple callers (e.g., those in Table 3) to increase confidence. Focus on rare, high-impact variants.

- Functional Enrichment Analysis: Annotate genes within recurrent CNV regions and perform pathway analysis (e.g., GO, KEGG) to identify disrupted biological processes.

- Phenotype Clustering: Correlate specific CNV signatures with clinical phenotypes, such as the enrichment of non-coding RNA regulator variations in sarcoma patients [29].

Figure 2: CNV Analysis Workflow for Pediatric Cancer with Birth Defects

Gene Fusions

Biology, Detection, and Clinical Significance

Oncogenic gene fusions are hybrid genes formed through chromosomal rearrangements such as translocations, inversions, deletions, or tandem duplications [25] [30]. These events can produce chimeric proteins with novel or constitutively active functions, such as aberrant tyrosine kinases or transcription factors, which act as powerful oncogenic drivers [25].

Fusions are defining features of many cancers, such as BCR-ABL1 in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) and EML4-ALK in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [25] [30]. Their detection is critical for diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment selection, as fusion-driven cancers often exhibit "oncogene addiction" and respond exceptionally well to targeted therapies [25]. Table 4 summarizes several key oncogenic fusions and their clinical relevance.

Table 4: Key Oncogenic Gene Fusions and Their Clinical Significance

| Gene Fusion | Disease | Functional Consequence | Therapeutic Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| BCR-ABL1 | Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML) | Constitutively active tyrosine kinase. | Targetable with tyrosine kinase inhibitors (e.g., imatinib) [25] [30]. |

| EML4-ALK | Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) | Constitutively active kinase activating PI3K/AKT, JAK/STAT, and RAS/MAPK pathways [30]. | Targetable with ALK inhibitors (e.g., crizotinib) [30]. |

| PML-RARA | Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia (APL) | Impairs differentiation and promotes proliferation of leukemic cells [30]. | Treatment with all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) and arsenic trioxide [30]. |

| TMPRSS2-ERG | Prostate Cancer | Overexpression of ERG transcription factor, altering cell proliferation and microenvironment [30]. | Active investigation for targeted therapies; informs prognosis [30]. |

| NTRK Fusions | Multiple solid tumors (e.g., secretory carcinoma, infantile fibrosarcoma) | Constitutively active TRK kinase signaling [25]. | Targetable with tumor-agnostic TRK inhibitors (e.g., larotrectinib) [25]. |

Detection Methodologies and Protocol

A variety of technologies exist for fusion gene detection, ranging from traditional methods to modern NGS-based approaches [30]. RNA-based next-generation sequencing (RNA-seq) is particularly effective as it directly identifies expressed fusion transcripts and is capable of discovering novel fusion partners [25] [30].

A comprehensive fusion detection protocol should integrate multiple omics layers:

- DNA/RNA Co-extraction: Isolate high-quality DNA and RNA from tumor tissue (fresh-frozen or FFPE) or liquid biopsy (circulating tumor DNA/RNA).

- Targeted NGS Panel Sequencing: Use anchored multiplex PCR (AMP)-based or hybrid capture-based panels designed to target intronic and exonic regions of known fusion driver genes (e.g., ALK, ROS1, RET, NTRK1/2/3) from both DNA and RNA.

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Utilize specialized fusion-finding tools (e.g., STAR-Fusion, Arriba, FusionCatcher) that align sequencing reads and detect chimeric transcripts with high confidence.

- Multi-omics Integration:

- Correlate fusion calls with transcriptomics data (e.g., outlier expression of the 3' gene) and phosphoproteomics data to confirm downstream pathway activation (e.g., elevated MAPK or PI3K signaling) [4].

- In EML4-ALK fusion-positive NSCLC, the fusion protein drives oncogenesis by sustaining activated tyrosine kinase activity, which hyperactivates the JAK/STAT, PI3K/AKT, and RAS/MAPK signaling pathways to promote cell growth and survival [30].

Figure 3: Key Signaling Pathways Activated by Kinase Fusion Proteins

Research Reagent Solutions for Fusion Analysis

Table 5: Key Reagents and Kits for Fusion Gene Detection

| Reagent / Kit | Function / Application | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| FFPE DNA/RNA Extraction Kits | Nucleic acid isolation from archival clinical samples. | Critical for leveraging large biobanks; requires protocols for degraded samples. |

| Anchored Multiplex PCR (AMP) | Targeted RNA-seq library preparation for fusion detection. | Effective for detecting fusions with unknown partners (e.g., ArcherDX). |

| Hybrid Capture Panels | Targeted DNA/RNA-seq focusing on cancer genes. | Comprehensive panels (e.g., MSK-IMPACT) can detect fusions, SNVs, and CNVs [11]. |

| Liquid Biopsy Kits | Isolation of ctDNA/ctRNA from plasma. | Enables non-invasive detection and monitoring of fusion status [30]. |

The individual analysis of SNVs, CNVs, and fusions provides powerful, yet incomplete, insights into cancer biology. The future of precision oncology lies in the AI-driven integration of multi-omics data [4]. Artificial intelligence (AI), particularly machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL), excels at identifying non-linear patterns across high-dimensional spaces, making it uniquely suited to integrate genomic data with transcriptomic, proteomic, and epigenomic layers [4] [11] [10]. For example, graph neural networks (GNNs) can model how a somatic mutation (SNV) perturbs protein-protein interaction networks, while multi-modal transformers can fuse MRI radiomics with transcriptomic data to predict tumor progression [4].

Framing the analysis of key drivers and variations within this multi-omics context transforms them from isolated biomarkers into interconnected nodes of a complex biological network. This holistic view is essential for uncovering robust biomarkers, understanding therapeutic resistance, and ultimately delivering on the promise of personalized, proactive cancer care [4] [11].

From Data to Decisions: AI-Driven Methodologies and Clinical Applications

Cancer's staggering molecular heterogeneity demands a move beyond traditional single-omics approaches to a more comprehensive, integrative perspective [4]. The simultaneous analysis of multiple molecular layers—genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, epigenomics, and metabolomics—through multi-omics integration provides a powerful framework for understanding the complex biological underpinnings of cancer [31]. However, this integration faces formidable computational challenges due to the high dimensionality, technical variability, and fundamental structural differences between datasets [4] [14]. Artificial intelligence (AI), particularly deep learning and graph neural networks (GNNs), has emerged as the essential computational scaffold that enables non-linear, scalable integration of these disparate data layers into clinically actionable insights for precision oncology [4] [32]. These technologies are transforming oncology from reactive, population-based approaches to proactive, individualized cancer management [4].

AI and Multi-Omics Data: Core Concepts and Definitions

The Multi-Omics Data Landscape

Multi-omics data in oncology spans multiple functional levels of biological organization, each providing distinct but interconnected insights into tumor biology [4]. Genomics identifies DNA-level alterations including single-nucleotide variants (SNVs), copy number variations (CNVs), and structural rearrangements that drive oncogenesis [4]. Transcriptomics reveals gene expression dynamics through RNA sequencing (RNA-seq), quantifying mRNA isoforms, non-coding RNAs, and fusion transcripts that reflect active transcriptional programs within tumors [4]. Epigenomics characterizes heritable changes in gene expression not encoded within the DNA sequence itself, including DNA methylation patterns and histone modifications [4]. Proteomics catalogs the functional effectors of cellular processes, identifying post-translational modifications, protein-protein interactions, and signaling pathway activities [4]. Finally, metabolomics profiles small-molecule metabolites, the biochemical endpoints of cellular processes, exposing metabolic reprogramming in tumors [4].

Artificial Intelligence Approaches for Multi-Omics Integration

Artificial intelligence provides a sophisticated computational framework for multi-omics integration that surpasses the capabilities of traditional statistical methods [4] [33]. Machine learning (ML) encompasses classical algorithms like logistic regression and ensemble methods that are often applied to structured omics data for tasks such as survival prediction or therapy response [33]. Deep learning (DL), a subset of ML, uses neural networks with multiple layers to model complex, non-linear relationships in high-dimensional data [4] [34]. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) are particularly adept at processing image-based data, including histopathology slides and radiomics features [4] [33]. Graph neural networks (GNNs) represent a specialized class of deep learning algorithms designed to operate on graph-structured data, making them ideally suited for modeling biological networks and patient similarity graphs [34] [35]. Transformers and large language models (LLMs) are increasingly applied to model long-range dependencies in sequential data and extract knowledge from scientific literature and clinical notes [4] [33].

Deep Learning Architectures for Multi-Omics Data Fusion

Data Integration Strategies and Methodologies

The integration of multi-omics data can be conceptualized through different methodological approaches based on the timing and nature of integration [14]. Early integration involves concatenating raw or preprocessed features from multiple omics layers into a single combined dataset before model training, though this approach risks disregarding heterogeneity between platforms [14]. Intermediate integration employs methods that transform each omics dataset separately while modeling their relationships, respecting platform diversity while capturing some cross-modal interactions [14]. Late integration trains separate models on each omics dataset and combines their predictions, ignoring potential synergies between molecular layers but offering implementation simplicity [14].

In the context of these integration approaches, two distinct analytical paradigms emerge: Vertical integration (N-integration) incorporates different omics data from the same samples, enabling the study of concurrent observations across different functional levels [14]. Horizontal integration (P-integration) combines data of the same molecular type from different subjects to increase statistical power and sample size [14].

Table 1: Multi-Omics Data Integration Strategies

| Integration Type | Description | Advantages | Limitations | Common Algorithms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early Integration | Concatenates raw features from multiple omics before analysis | Captures cross-omics interactions; single model | Disregards data heterogeneity; sensitive to normalization | LASSO, Elastic Net, Deep Neural Networks |

| Intermediate Integration | Transforms omics data separately while modeling relationships | Respects platform diversity; captures some interactions | Complex implementation; model interpretation challenges | Multi-Kernel Learning, MOFA, Cross-modal Autoencoders |

| Late Integration | Combines predictions from separate omics models | Simple implementation; robust to technical variability | Ignores inter-omics synergies; suboptimal performance | Stacking, Ensemble Methods, Cluster-of-Clusters |

| Vertical (N-Integration) | Integrates different omics from the same samples | Studies biological continuum across molecular layers | Requires complete multi-omics profiling | Multi-View Algorithms, Graph Neural Networks |

| Horizontal (P-Integration) | Combines same omics data from different cohorts | Increases sample size; enhances statistical power | Batch effect challenges; cross-study heterogeneity | Meta-analysis, Federated Learning |

Graph Neural Networks for Biological Network Analysis

Graph Neural Networks represent a particularly powerful framework for multi-omics integration because they can natively model the complex relational structures inherent in biological systems [35]. In this paradigm, molecular entities (genes, proteins, metabolites) are represented as nodes, while their functional, physical, or regulatory interactions are represented as edges [34] [35]. The core innovation of GNNs is their ability to learn from both node features and graph structure through message-passing mechanisms, where each node aggregates information from its neighbors to compute updated representations [34].

Several specialized GNN architectures have been developed with distinct advantages for biological data analysis. Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) extend convolutional operations from regular grids to graph-structured data, propagating information throughout the graph and aggregating it to update node representations [34]. In a breast cancer study predicting axillary lymph node metastasis, a GCN model achieved an AUC of 0.77, demonstrating clinical utility for non-invasive detection [34]. Graph Attention Networks (GATs) incorporate attention mechanisms to differentially weigh the importance of neighboring nodes, allowing the model to focus on the most relevant molecular interactions [34]. Graph Isomorphism Networks (GINs) utilize a sum aggregation function and multi-layer perceptron to analyze node characteristics, providing enhanced discriminative power for graph classification tasks [34].

Diagram 1: GNN Architecture for Multi-Omics Integration. This workflow illustrates how heterogeneous omics data is structured as a graph and processed through multiple GNN layers with attention mechanisms to generate predictive outputs for precision oncology.

Application Notes: AI-Driven Multi-Omics in Precision Oncology

Cancer Subtype Classification and Patient Stratification

Multi-omics integration through AI has demonstrated remarkable success in refining cancer molecular subtyping and patient stratification beyond conventional histopathological classifications [4] [31]. For example, in glioma and clear-cell renal-cell carcinoma, the Pathomic Fusion model integrated histology and genomics data to outperform the World Health Organization 2021 classification system for risk stratification [32]. A pan-tumor analysis of 15,726 patients combined multimodal real-world data with explainable AI to identify 114 key markers across 38 solid tumors, which were subsequently validated in an external lung cancer cohort [32]. These approaches leverage the complementary nature of different data modalities—where genomics provides information about driver alterations, transcriptomics reveals activated pathways, and proteomics captures functional effectors—to create more robust and biologically meaningful patient classifications [4].

Therapy Response Prediction and Treatment Selection

AI-powered multi-omics models are increasingly guiding therapeutic decisions by predicting treatment response and resistance mechanisms [4] [32]. The TRIDENT machine learning model integrates radiomics, digital pathology, and genomics data from the Phase 3 POSEIDON study in metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) to identify patient subgroups most likely to benefit from specific treatment strategies [32]. This approach demonstrated significant hazard ratio reductions (0.88–0.56 in non-squamous histology population) compared to standard stratification methods [32]. Similarly, the DREAM drug sensitivity prediction challenge revealed that multimodal approaches consistently outperform unimodal ones in predicting therapeutic outcomes across breast cancer cell lines [32]. These models can capture the complex interplay between genomic alterations, signaling pathway activities, and tumor microenvironment features that collectively determine therapeutic efficacy [4].

Table 2: Performance Metrics of AI-Based Multi-Omics Models in Oncology Applications

| Application Domain | AI Model | Cancer Type | Data Modalities | Performance Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early Detection | Multi-modal AI | Multiple Cancers | ctDNA methylation, fragmentomics | 78% sensitivity, 99% specificity for 75 cancer types | [36] |

| Lymph Node Metastasis Prediction | Graph Convolutional Network | Breast Cancer | Ultrasound, clinical, histopathologic data | AUC: 0.77 (95% CI: 0.69–0.84) | [34] |

| Risk Stratification | Pathomic Fusion | Glioma, Renal Cell Carcinoma | Histology, genomics | Outperformed WHO 2021 classification | [32] |

| Therapy Response Prediction | TRIDENT | NSCLC (Metastatic) | Radiomics, digital pathology, genomics | HR reduction: 0.88–0.56 (non-squamous population) | [32] |

| Drug Sensitivity Prediction | Multimodal DL | Breast Cancer | Multi-omics cell line data | Consistently outperformed unimodal approaches | [32] |

| Relapse Prediction | MUSK Transformer | Melanoma | Multimodal clinical data | AUC: 0.833 for 5-year relapse | [32] |

Multi-Cancer Early Detection and Risk Stratification

Multimodal AI approaches are revolutionizing cancer screening through multi-cancer early detection (MCED) tests that analyze circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) in blood samples [32] [36]. The SPOT-MAS test utilizes multi-omics data including DNA fragments, methylation patterns, copy number aberrations, and genetic mutations, combined with multi-modal AI algorithms to detect ctDNA signals and identify their tissue of origin [36]. This approach can screen for up to 75 cancer types and subtypes with 78% sensitivity and 99% specificity from a single blood draw [36]. Similarly, the Sybil AI model demonstrated exceptional performance in predicting lung cancer risk from low-dose computed tomography (CT) scans with up to 0.92 ROC–AUC, enabling effective integration into existing screening programs [32]. These technologies represent a paradigm shift from organ-specific to pan-cancer screening approaches with significant potential for population-level impact.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Graph Neural Network for Multi-Omics Integration

Objective: Implement a GNN framework to integrate genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic data for cancer subtype classification.

Materials and Reagents:

- Next-Generation Sequencing Data: Whole exome/genome sequencing (DNA), RNA sequencing (RNA)

- Proteomic Profiling Data: Mass spectrometry or RPPA data

- Computational Environment: Python 3.8+, PyTorch Geometric 2.0+, PyTorch 1.10+

Procedure:

Data Preprocessing and Normalization

- Perform quality control on each omics dataset using platform-specific methods (e.g., DESeq2 for RNA-seq, ComBat for batch correction)

- Normalize each omics dataset using variance-stabilizing transformations

- Handle missing values using k-nearest neighbors imputation (k=10)

Graph Construction

- Represent each patient as a separate graph where nodes represent molecular entities (genes, proteins)

- Create edges based on:

- Protein-protein interactions from STRING database (confidence score > 0.7)

- Gene co-expression networks (top 5% of correlations)

- Pathway interactions from KEGG and Reactome

- Initialize node features using z-score normalized expression/mutation values

GNN Model Architecture

Model Training and Validation

- Implement 5-fold cross-validation with stratified sampling

- Use Adam optimizer with learning rate of 0.001 and weight decay of 5e-4

- Train for maximum of 500 epochs with early stopping (patience=30)

- Employ class-weighted cross-entropy loss to handle imbalanced datasets

Model Interpretation

- Apply GNNExplainer to identify important subgraph structures

- Use saliency maps to highlight influential molecular features

- Perform pathway enrichment analysis on top-ranked features

Validation Metrics: Accuracy, F1-score, AUC-ROC, Precision-Recall curves

Protocol: Multimodal Deep Learning for Therapy Response Prediction

Objective: Develop a multimodal deep learning model to predict immunotherapy response in melanoma patients.

Materials and Reagents:

- Multi-omics Data: Whole exome sequencing, RNA-seq, multiplex immunohistochemistry

- Clinical Data: Treatment history, response criteria (RECIST), survival outcomes

- Software Libraries: TensorFlow 2.8+, Scikit-learn 1.0+, NumPy 1.21+

Procedure:

Data Preprocessing

- Genomic features: Encode mutations as binary indicators, CNVs as continuous values

- Transcriptomic features: Select top 5,000 most variable genes, TPM normalization

- Image features: Extract deep features from histopathology slides using pretrained ResNet-50

- Clinical features: Normalize continuous variables, one-hot encode categorical variables

Multimodal Fusion Architecture

- Implement separate encoding branches for each modality:

- Genomic branch: 2 fully-connected layers (512, 256 units) with ReLU activation

- Transcriptomic branch: 1D convolutional layers with attention mechanism

- Image branch: Pretrained CNN with fine-tuning, global average pooling

- Clinical branch: 2 fully-connected layers (128, 64 units)

- Apply cross-modal attention to model interactions between modalities

- Implement late fusion with weighted averaging based on modality reliability

- Implement separate encoding branches for each modality:

Model Training

- Use balanced mini-batch sampling (batch size=32)

- Optimize with AdamW optimizer (learning rate=0.0001, weight decay=0.01)

- Apply gradient clipping (max norm=1.0) and learning rate scheduling

- Regularize with dropout (rate=0.5) and label smoothing (epsilon=0.1)

Model Interpretation

- Compute Shapley values to quantify feature importance

- Generate partial dependence plots for key features

- Visualize cross-modal attention weights

Validation: Time-dependent ROC analysis, Kaplan-Meier survival curves, Concordance index

Diagram 2: Multi-Omics AI Integration Workflow. This end-to-end experimental protocol outlines the key stages in developing and validating AI models for multi-omics data integration, from preprocessing to clinical application.

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for AI-Driven Multi-Omics Integration

| Category | Tool/Resource | Function | Application in Multi-Omics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Generation | Next-Generation Sequencing | Genomic, transcriptomic, epigenomic profiling | Foundation for molecular characterization of tumors [4] |

| Data Generation | Mass Spectrometry | Proteomic, metabolomic quantification | Functional profiling of proteins and metabolites [4] |

| Data Generation | Multiplex Immunohistochemistry | Spatial protein expression analysis | Tumor microenvironment characterization [4] |

| Computational Framework | PyTorch Geometric | GNN library extension for PyTorch | Implementation of graph neural networks [34] |

| Computational Framework | MONAI (Medical Open Network for AI) | Open-source PyTorch-based framework | AI tools and pre-trained models for medical imaging [32] |

| Biological Databases | STRING, KEGG, Reactome | Protein-protein interactions, pathways | Prior biological knowledge for graph construction [35] |

| Bioinformatics Tools | DESeq2, ComBat | RNA-seq normalization, batch correction | Data preprocessing and quality control [4] |

| Model Interpretation | SHAP, GNNExplainer | Explainable AI techniques | Model interpretability and biomarker discovery [4] |

| Cloud Platforms | DNAnexus, Galaxy | Cloud-based data analysis | Scalable processing of petabyte-scale datasets [4] |