Beyond Static Structures: A 2025 Guide to Mastering Protein Flexibility in Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Protein function is governed by dynamic conformational changes, not static structures, making the accurate handling of flexibility a central challenge in molecular dynamics (MD).

Beyond Static Structures: A 2025 Guide to Mastering Protein Flexibility in Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Abstract

Protein function is governed by dynamic conformational changes, not static structures, making the accurate handling of flexibility a central challenge in molecular dynamics (MD). This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals, covering the foundational principles of protein dynamics, the latest AI-enhanced and machine learning methods for simulating flexibility, strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing simulations, and rigorous techniques for validating results against experimental data. By synthesizing cutting-edge developments from 2024-2025, we offer a practical roadmap for leveraging dynamic simulations to drive discoveries in structural biology and therapeutic design.

Why Motion Matters: The Fundamental Principles of Protein Dynamics

The traditional view of proteins as static, rigid structures has been fundamentally overturned. Modern structural biology now recognizes that protein function arises from the intricate interplay of structure, dynamics, and biomolecular interactions [1] [2]. While advances in cryo-EM and AI-based structure prediction have provided high-resolution snapshots, capturing the dynamic and energetic features that govern protein function remains a significant challenge [1] [2]. This paradigm shift from analyzing single structures to characterizing dynamic ensembles is crucial for understanding biological mechanisms and accelerating drug discovery.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why is considering protein flexibility critical in modern drug design? Protein flexibility is fundamental because a protein's function is directly linked to its motion. Ligands often bind to transient, low-population states rather than the average structure seen in a single crystal. By studying dynamic ensembles, researchers can identify these functionally important intermediates, leading to more effective drugs that target specific conformational states [1] [2].

2. What experimental techniques provide data on protein dynamics? Several biophysical methods yield valuable, though often indirect, information on dynamics. Key techniques include:

- NMR: Provides atomic-resolution information on dynamics across various timescales.

- HDX-MS: Probes protein mobility by measuring hydrogen-deuterium exchange.

- SAXS: Offers low-resolution information on overall shape and flexibility in solution.

- cryo-EM: Can sometimes capture multiple conformational states.

- EPR: Used to study dynamics and distances in proteins [1] [2].

3. How do simulations integrate with experimental data to study flexibility? Integrative modeling approaches combine data from the techniques above with physics-based molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. A key method uses the maximum entropy principle to build dynamic ensembles that are consistent with all available experimental data while addressing uncertainty and bias. This reveals both stable structures and transient, functionally important intermediates [1] [2].

4. What is a common challenge when simulating ligand unbinding, and how can it be addressed? A major challenge is preventing the entire protein-ligand complex from drifting under force while allowing natural flexibility for the unbinding process. A study on Steered Molecular Dynamics (SMD) proposed an effective solution: applying a restrained potential only to the Cα atoms of the protein located more than 1.2 nm from the ligand. This method offers a more natural release of the ligand compared to fully rigid or overly flexible restraints [3].

Troubleshooting Guide: Protein Flexibility in Simulations

Problem: Unphysical Results in Ligand Unbinding Simulations

Symptoms: The ligand fails to exit the binding site, the protein structure deforms unnaturally, or the entire complex drifts in the water solvent.

| Possible Cause | Recommendation | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Overly rigid protein backbone | Avoid restraining all heavy atoms or all Cα atoms. Instead, restrain only Cα atoms beyond a specific distance (e.g., >1.2 nm) from the ligand [3]. | Allows necessary local flexibility in the binding site for a natural unbinding pathway while preventing global drift. |

| Excessively flexible protein backbone | Apply a harmonic restraint to a sufficient number of Cα atoms to anchor the protein. A too-weak restraint cannot counter the pulling force [3]. | Prevents the external force from translating the entire complex, ensuring it focuses on breaking ligand-protein interactions. |

| Suboptimal pulling direction | Choose a pulling direction based on structural analysis, such as the center of the protein's binding pocket exit tunnel [3]. | Mimics a more physiologically relevant unbinding pathway and increases simulation success. |

Problem: Difficulty in Reconciling Simulation Data with Experiments

Symptoms: Your computational ensemble does not match or explain data from biophysical experiments like HDX-MS or NMR.

| Possible Cause | Recommendation | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Sampling is insufficient | Use enhanced sampling methods to overcome energy barriers and explore a wider conformational space [1] [2]. | Captures rare events and transient states that are critical for function but poorly sampled in standard simulations. |

| Experimental data is not integrated | Employ integrative modeling and the maximum entropy principle to bias simulations toward ensembles that agree with experimental data [1] [2]. | Ensures the computational model is not only physically plausible but also consistent with real-world observational data. |

| Bias from a single static structure | Initiate simulations from multiple different conformations (if available) rather than a single PDB structure. | Helps avoid getting trapped in the local energy minimum of the starting crystal form and explores ensemble diversity. |

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Integrative Modeling for Dynamic Ensembles

Objective: To construct a dynamic ensemble of protein conformations that integrates data from multiple biophysical experiments and physics-based simulations.

- Data Collection: Gather experimental data from techniques such as NMR (chemical shifts, J-couplings, NOEs), HDX-MS (protection factors), SAXS (scattering curves), and/or cryo-EM (density maps) [1] [2].

- Simulation Setup: Initialize molecular dynamics (MD) simulations using a starting structure (e.g., from AlphaFold2 or a crystal structure).

- Ensemble Refinement: Use the maximum entropy principle to reweight the simulation trajectories. This method applies minimal bias to the simulation so that the final ensemble's averaged properties match the experimental data [1] [2].

- Validation and Analysis: Validate the ensemble against experimental data not used in the refinement. Analyze the ensemble to identify metastable states, conformational heterogeneity, and functional mechanisms.

Protocol 2: SMD for Ligand Unbinding with Optimized Restraints

Objective: To simulate the unbinding pathway of a ligand from its protein target using a rationally restrained protein backbone [3].

System Preparation:

- Obtain the protein-ligand complex structure (e.g., from PDB).

- Add hydrogen atoms, solvate the system in a water box, and add ions to neutralize the charge.

- Use an appropriate force field (e.g., Amber ff99SB-ILDN for the protein and GAFF for the ligand).

Define Restraints:

- Identify all Cα atoms in the protein.

- Calculate the distance from each Cα atom to the ligand.

- Apply a harmonic restraint potential only to those Cα atoms that are more than 1.2 nm away from the ligand [3].

SMD Simulation:

- Attach a virtual spring to the ligand.

- Pull the spring along a chosen vector (e.g., the center of the binding pocket exit tunnel) at a constant velocity.

- Record the force and displacement profiles over time.

Analysis:

- Analyze the rupture force and work profile.

- Identify key residues and interactions along the unbinding pathway.

- Monitor the protein's conformational changes during ligand release.

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| GROMACS | A versatile software package for performing molecular dynamics simulations; used for system preparation, simulation, and analysis [3]. |

| Amber ff99SB-ILDN Force Field | A highly regarded force field parameter set for proteins, providing accurate descriptions of bonded and non-bonded interactions in MD simulations [3]. |

| General Amber Force Field (GAFF) | A force field designed for parameterizing small organic molecules, like drug ligands, for use in simulations with the Amber suite [3]. |

| PyMOL | A molecular visualization system used for repairing missing residues in protein structures and for generating publication-quality images [3]. |

| NMR Spectroscopy | An experimental technique used to obtain atomic-level information on protein dynamics and structure in solution [1] [2]. |

| HDX-MS | An experimental technique that measures hydrogen-deuterium exchange to probe protein mobility and solvent accessibility [1] [2]. |

| Maximum Entropy Reweighting | A computational algorithm used to integrate experimental data with simulations, generating a statistically sound dynamic ensemble [1] [2]. |

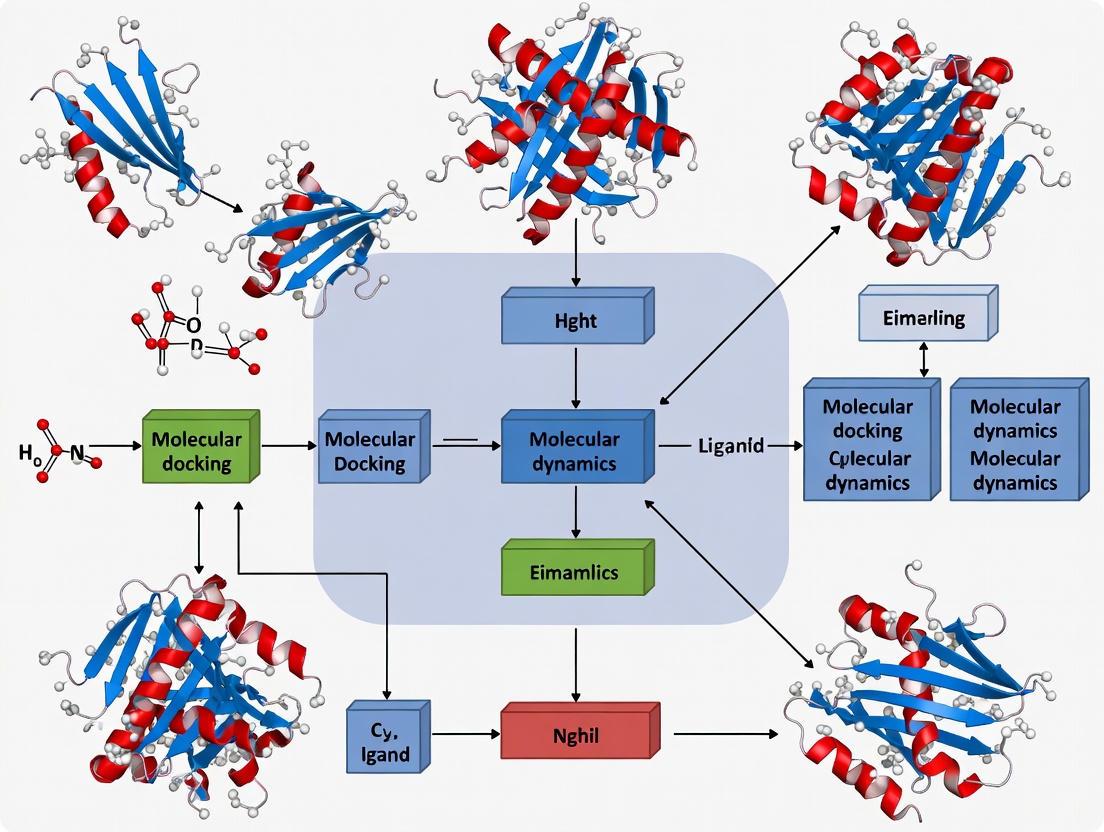

Workflow Visualizations

Diagram 1: Integrative Workflow for Dynamic Ensemble Determination.

Diagram 2: Decision Flow for Protein Restraint in SMD.

Frequently Asked Questions & Troubleshooting Guides

This technical support center addresses common challenges researchers face when handling protein flexibility in molecular dynamics simulations, providing practical solutions and methodologies.

FAQ 1: How can I account for large-scale backbone flexibility during steered molecular dynamics (SMD) simulations?

Challenge: A researcher is unable to achieve a natural ligand release pathway during SMD simulations. The ligand either gets stuck in the binding site or the entire protein-ligand complex drifts under the influence of the water bulk layer.

Solution: The restraint strategy applied to the protein backbone must balance preventing overall drift while permitting necessary local flexibility. Avoid restraining all heavy atoms or all Cα atoms, as this oversimplifies the system and fails to capture biologically relevant dynamics [3]. Instead, apply harmonic restraints only to the Cα atoms of residues located more than 1.2 nm from the ligand [3]. This method prevents global rotation and drift while allowing the protein backbone around the binding site to adapt flexibly during the ligand's egress.

Experimental Protocol: SMD with Optimized Backbone Restraints [3]

System Preparation:

- Obtain the protein-ligand complex structure (e.g., from the PDB Bank).

- Add hydrogen atoms using GROMACS (version 2020 and above) or similar software.

- Repair any missing residues using a tool like PyMol.

- Optimize the ligand's geometry and derive its electrostatic potential map using the Gaussian 16 package at the B3LYP/6-31+G(d,p) level.

- Assign atomic net charges using the RESP method and generate additional parameters with the Antechamber module of AMBER Tools and the General Amber Force Field (GAFF).

Simulation Setup:

- Solvate the system in a cubic box, ensuring a minimum distance of 0.6 nm between the protein surface and the box boundaries.

- Neutralize the system by adding Na+ or Cl− ions.

- Employ the Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) method for long-range electrostatic interactions and set periodic boundary conditions.

- Apply the SHAKE algorithm to constrain covalent bonds involving hydrogen atoms.

Defining Restraints:

- Calculate the distance between every protein Cα atom and the ligand.

- Apply a harmonic restraint potential only to Cα atoms located more than 1.2 nm from the ligand. This creates a flexible but stable simulation environment.

SMD Production:

- Apply the external pulling force to the ligand.

- Record the force-time and displacement-time profiles for analysis.

FAQ 2: My simulations are computationally expensive. Are there efficient alternatives to all-atom MD for initial flexibility screening?

Challenge: A research group needs to study the flexibility of a large protein or multiple mutants but lacks the computational resources for extensive all-atom MD.

Solution: Utilize efficient, coarse-grained simulation tools for initial screening and to gain a rapid overview of protein dynamics.

Comparison of Computational Methods for Protein Flexibility Analysis

| Method | Key Features | Typical Application | Computational Cost | Example Tools |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All-Atom MD | High accuracy, atomistic detail, uses explicit solvent [4] | Studying specific molecular interactions, ligand unbinding [3] | Very High | GROMACS [4], AMBER |

| Coarse-Grained MD | Faster than all-atom MD, simplified residue representation [5] | Rapid simulation of large systems, near-native dynamics, loop flexibility [5] | Medium | CABS-flex 3.0 [5] |

| Elastic Network Models (ENMs) | Very fast, models protein as beads and springs [6] | Predicting large-scale collective motions and low-frequency modes [6] | Low | ProDy [6] |

| Machine Learning Predictors | Fast prediction from sequence or structure, no simulation required [6] | High-throughput screening, guiding protein design [6] | Very Low | Flexpert-Seq, Flexpert-3D [6] |

Experimental Protocol: Rapid Flexibility Profiling with CABS-flex [5]

CABS-flex is a coarse-grained simulation tool useful for modeling the flexibility of globular proteins, proteins with disordered regions, and loop dynamics.

- Input Preparation: Prepare the protein structure in PDB format. The server can handle structures with missing residues.

- Job Submission: Access the CABS-flex 3.0 web server (https://lcbio.pl/cabsflex3/) and upload your structure.

- Configuration (Optional): Define the degree of flexibility for specific fragments using distance restraints if needed.

- Simulation Execution: Run the simulation. CABS-flex typically completes trajectories much faster than all-atom MD.

- Analysis: Download the resulting trajectory and analyze it for Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) and other flexibility metrics to identify dynamic regions.

FAQ 3: How can I integrate AI-predicted structures to study the energy landscapes of flexible regions?

Challenge: A scientist has used AlphaFold2 to model a protein, but the model contains unresolved flexible regions critical for function. They need to explore the conformational energy landscape of these regions.

Solution: Combine AI-based structural models with physics-based simulation methods to explore the energy landscape of flexible regions.

Experimental Protocol: Exploring Energy Landscapes with Metadynamics and AI [7]

This protocol uses metadynamics simulations to sample the energy landscape based on initial AI-generated models.

- Initial Model Generation: Use AI tools (AlphaFold2, RosettaFold, etc.) or traditional modeling (MODELER, SwissModel) to generate initial structural approximations for the flexible regions.

- System Setup: Prepare the full protein system for molecular dynamics, incorporating the AI-generated models.

- Metadynamics in Latent Space:

- Define Collective Variables (CVs) that describe the conformational changes of interest in the flexible regions.

- Perform metadynamics simulations to deliberately "fill" the energy basins with a history-dependent potential. This encourages the system to escape local minima and explore a wider conformational space.

- Landscape Reconstruction: Use the data from the metadynamics simulation to reconstruct the underlying free energy landscape as a function of the defined CVs.

- Conformation Prioritization: Identify the low-energy minima on the reconstructed landscape. These represent the stable, functionally relevant conformations of the previously unresolved region [7].

FAQ 4: How does protein flexibility influence evolution and the risk of aggregation?

Challenge: Understanding why certain functional proteins are prone to aggregation and how evolution balances function with stability.

Solution: Evolutionary pressure selects for sequences that can sample multiple conformational sub-states to enable function, not just for stability. This functional necessity inherently creates a risk of aggregation, as some of these sub-states may expose hydrophobic surfaces or aggregation-prone sequences [8].

Key Concepts Table

| Concept | Description | Implication for MD Research |

|---|---|---|

| Functional Sub-states | Distinct conformational states within a protein's ensemble that are relevant to its biological function [9]. | Simulations should be long enough to sample these rare but critical states. |

| Rough Energy Landscape | A landscape with multiple energy minima, allowing a protein to sample various conformations [8]. | Explains conformational heterogeneity observed in long-timescale simulations. |

| Aggregation Risk | The inherent danger that functionally required conformational states may expose aggregation-prone motifs [8]. | Simulations can help identify these risky states by analyzing surface exposure of hydrophobic residues. |

| Conformational Ensemble | The collection of all structures a protein adopts under specific conditions [9]. | Analysis should focus on the ensemble, not just a single static structure. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Resources for Studying Protein Flexibility

| Item | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| ATLAS Database | A database of standardized all-atom MD simulations for a representative set of proteins [4]. | Benchmarking your simulation results against a standardized dataset. |

| Flexpert Predictors | Machine learning tools (Flexpert-Seq, Flexpert-3D) that predict protein flexibility from sequence or structure [6]. | Quickly estimating flexibility for high-throughput design projects. |

| LoopGrafter | A web tool for in silico transplantation of dynamic loops between proteins to engineer flexibility [6]. | Designing chimeric proteins to test the role of specific flexible loops. |

| AGGRESCAN3D (A3D) | A server that predicts aggregation properties of protein structures, which can incorporate flexibility data from CABS-flex [5]. | Assessing how protein dynamics might influence aggregation propensity. |

Appendix: Conceptual Diagrams

Energy Landscape Diagram

SMD Restraint Methodology

Conceptual Foundations: Understanding Flexibility Drivers

Protein flexibility is not a single entity but a spectrum of dynamic behaviors driven by a protein's innate sequence and modulated by its external environment. Understanding this distinction is crucial for designing accurate simulations.

What are the fundamental differences between intrinsic and extrinsic flexibility?

- Intrinsic Flexibility is encoded within the protein's amino acid sequence. Certain sequences have a natural propensity for disorder or high mobility, often because they lack the hydrophobic residues needed to form a stable core and are enriched in charged and polar amino acids [10]. This includes Intrinsically Disordered Regions (IDRs) and flexible loops or linkers that remain dynamic even in the protein's native, folded state.

- Extrinsic Flexibility arises from a protein's interactions with its environment. This includes:

- Ligand Binding: The presence of a small molecule, substrate, or inhibitor can induce structural changes, a phenomenon known as "induced fit" [11].

- Protein-Protein Interactions: Binding to another biomolecule can stabilize or destabilize certain conformations, altering flexibility.

- Solvent and Ions: The composition of the surrounding solution (e.g., pH, ion concentration) can affect electrostatic interactions and protein dynamics [4].

How do B-factors from crystallography relate to MD-derived flexibility metrics?

Both measure flexibility but in different contexts. The B-factor (or temperature factor) from X-ray crystallography reflects the smearing of electron density around an atom's average position, reporting on uncertainty that can stem from thermal vibration or static disorder [10]. In contrast, Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) from Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations is a direct measure of the deviation of an atom's position from its average over time, providing a explicit, atomistic view of dynamics [4]. While often correlated, they are not identical. A 2025 study notes that AlphaFold's pLDDT can sometimes correlate better with MD-derived RMSF than with B-factors from isolated crystal structures [11].

Can AlphaFold2's pLDDT score reliably predict protein flexibility?

This is an area of active research and requires careful interpretation. The pLDDT score is primarily a confidence metric indicating how well the predicted structure agrees with co-evolutionary and structural data. While very low pLDDT scores (<50-70) are strong indicators of intrinsic disorder or high flexibility, the score's utility for assessing flexibility in well-folded, globular regions is more limited [11]. A key limitation is that standard AlphaFold2 predictions often do not capture the flexibility changes induced by extrinsic factors like ligand binding, as they are typically generated for the protein in isolation [11]. Therefore, pLDDT should be used as a preliminary guide, not a definitive measure of flexibility.

Why do different experimental structures of the same protein show conformational variation?

This variation is a direct observation of protein flexibility and can be driven by both intrinsic and extrinsic factors. Different crystallization conditions (e.g., pH, ligands, crystal packing) can trap the protein in distinct conformational states. A 2024 analysis found that for 27.7% of distinct protein folds, at least one experimental structure deviated from the AlphaFold2 prediction by over 2.5Å RMSD, demonstrating that this flexibility is widespread and biologically relevant, especially in proteins regulating immune response and metabolism [12].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Scenarios and Solutions

My simulation system becomes unstable shortly after energy minimization. What could be wrong?

Instability often stems from problems in the initial system setup.

- Problem: Missing atoms in the initial structure. GROMACS's

pdb2gmxwill fail with errors like "atom X in residue Y not found" or "long bonds and/or missing atoms" [13]. Running a simulation with missing atoms is not recommended and will lead to crashes. - Solution: Use external modeling software like Chimera with MODELLER, Swiss PDB Viewer, or AlphaFold2 to reconstruct any missing atoms or loops in your protein structure before proceeding with topology generation [13] [14].

- Problem: Incorrect parameters for non-standard residues. Using parameters from one force field for a molecule parametrized in another will cause unphysical behavior [14].

- Solution: Parametrize the non-standard residue (e.g., a ligand) yourself according to the methodology of your chosen force field, or find a topology file that is specifically designed for it [14].

My protein's flexible regions are not sampling the correct conformational space during MD. How can I improve this?

This indicates a sampling problem, which is common for slow-moving loops or domain motions.

- Problem: Insufficient simulation time. The timescale of the motion you wish to observe may be longer than your simulation.

- Solution: Consider using enhanced sampling methods. Tools like GENESIS support advanced algorithms such as Replica-Exchange MD (REMD) and Gaussian accelerated MD (GaMD) which can greatly improve the sampling of conformational states [15].

- Problem: Over-restraining the system. Applying overly tight position restraints can artificially suppress the natural flexibility you are trying to study.

- Solution: Use position restraints judiciously, typically only during initial equilibration, and release them for the production simulation. Ensure restraint files are included in the correct order in your topology [13].

AlphaFold2 predicts my protein with a high-confidence (pLDDT) rigid structure, but experimental data suggests a flexible region. Who should I trust?

Trust the experimental data. AlphaFold2 has a known tendency to predict a single, static conformation.

- Problem: AF2 does not ensemble functional states. It often predicts one high-accuracy conformation but may miss alternative biologically relevant states captured by experiments [12].

- Solution: Use the AF2 model as a starting point. If experimental data (like NMR, HDX-MS, or cryo-EM) indicates flexibility, use MD simulations to explore the conformational landscape around the AF2-predicted structure. The ATLAS database provides standardized MD trajectories for many proteins, which can serve as a useful reference for expected dynamic behavior [4].

I see "bonds" appearing and disappearing when I visualize my simulation trajectory. Is this an error?

This is almost always a visualization artifact, not a problem with your simulation data.

- Problem: Visualization software uses distance-based bonding. Most visualization tools determine bonds based on predefined distances between atoms, which can change as the protein moves.

- Solution: The true bonding information is defined in your topology file. If your visualization software can read the GROMACS

.tprfile, it will display the correct, unchanging bonding pattern [14].

Experimental Protocols for Flexibility Analysis

Protocol 1: Quantifying Flexibility from Molecular Dynamics Simulations

This protocol outlines how to derive protein flexibility metrics from an all-atom MD simulation, based on methodologies used in large-scale datasets like ATLAS [4].

1. System Preparation and Simulation

- Force Field: Use the CHARMM36m force field, which provides balanced sampling for both folded and disordered states [4].

- Solvation: Solvate the protein in a triclinic box with TIP3P water molecules.

- Neutralization: Add Na⁺/Cl⁻ ions to a physiological concentration of 150 mM.

- Equilibration: Perform step-wise equilibration:

- Energy minimization using the steepest descent algorithm.

- NVT ensemble equilibration for 200 ps.

- NPT ensemble equilibration for 1 ns with position restraints on protein heavy atoms.

- Production Run: Run multiple (e.g., 3) independent replicates of unrestrained production simulation for at least 100 ns each, saving coordinates every 10 ps [4].

2. Trajectory Analysis

- RMSF Calculation: After aligning the trajectory to a reference structure to remove global rotation/translation, calculate the RMSF for each Cα atom using the formula:

RMSFᵢ = √( (1/T) * Σₜ₌₁ᵀ (rᵢ(t) - ⟨rᵢ⟩)² )

where

rᵢ(t)is the position of Cα atom i at time t,⟨rᵢ⟩is its average position, and T is the total number of frames [4] [11]. - Other Metrics: Analyze the trajectory for other flexibility indicators, such as the variation in solvent accessible surface area (SASA) or the number of distinct protein blocks (a structural alphabet) sampled per residue [11].

Protocol 2: Correlating AF2 Prediction with Experimental Flexibility

This protocol provides a framework for critically evaluating AlphaFold2 outputs against experimental flexibility data [12] [11].

1. Generate the AF2 Model

- Use ColabFold (a streamlined version of AF2) or the local AlphaFold2 software to generate a structural model of your protein of interest.

- Extract the per-residue pLDDT scores from the output.

2. Acquire Experimental Flexibility Data

- B-factors: If available, download B-factors from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) for crystallographic structures of your protein or homologs.

- NMR Ensembles: For proteins with NMR structures, use the ensemble of models to calculate per-residue RMSF.

- HDX-MS Data: If available, Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange Mass Spectrometry data can serve as a proxy for backbone flexibility and solvent exposure.

3. Comparative Analysis

- Plot the pLDDT score, experimental B-factors (or NMR RMSF), and any MD-derived RMSF on the same graph for visual comparison.

- Calculate correlation coefficients (e.g., Pearson's) between pLDDT and the experimental metrics.

- Key Interpretation: A strong correlation suggests the predicted flexibility is reliable. A weak correlation, especially in regions known to interact with partners, indicates that extrinsic factors may be dominating the flexibility profile, and MD simulations may be necessary for a fuller picture [11].

Reference Tables and Data

Table 1: Amino Acid Propensities in Flexible and Ordered Regions

This table summarizes the enrichment and depletion of amino acids in different flexibility categories, based on a comparative analysis of crystal structures [10]. Positive values indicate enrichment in that category, negative values indicate depletion.

| Amino Acid | Low B-factor (Ordered) | High B-factor (Flexible Ordered) | Short Disordered Regions | Long Disordered Regions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tryptophan (W) | Enriched | Depleted | Depleted | Depleted |

| Phenylalanine (F) | Enriched | Depleted | Depleted | Depleted |

| Glutamic Acid (E) | Depleted | Enriched | Enriched | Enriched |

| Lysine (K) | Depleted | Enriched | Enriched | Enriched |

| Asparagine (N) | Slightly Depleted | Highly Enriched | Slightly Enriched | Depleted |

| Glycine (G) | - | Enriched | Enriched | Not Enriched |

| Proline (P) | - | Not Enriched | Not Enriched | Enriched |

Table 2: Comparison of Methods for Assessing Protein Flexibility

This table provides a high-level comparison of common techniques used in the field.

| Method | Type | What It Measures | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| X-ray B-factor | Experimental | Uncertainty in atom position from crystal lattice. | Direct experimental readout; high resolution. | Confounds thermal motion and static disorder; crystal packing can suppress dynamics [10] [11]. |

| NMR Ensemble | Experimental | Ensemble of conformations in solution. | Directly visualizes an ensemble of states in near-native conditions. | Limited to smaller proteins; can be cost and time-prohibitive. |

| HDX-MS | Experimental | Rate of hydrogen/deuterium exchange on backbone amides. | Probes solvent exposure and dynamics; works on large complexes. | Indirect measure of flexibility; lower resolution. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) | Computational | Time-based fluctuation of atomic positions (e.g., RMSF). | Provides atomistic detail and time evolution; can simulate any condition. | Computationally expensive; sampling and force field accuracy are concerns [4] [16]. |

| AlphaFold2 pLDDT | Computational | Confidence in local structure prediction. | Very fast; no simulation required. | A confidence metric, not a direct flexibility measure; poor at capturing extrinsic flexibility [11]. |

| Elastic Network Models (ENM) | Computational | Low-frequency collective motions of a structure. | Extremely fast; good for large-scale motions. | Coarse-grained; lacks atomic detail and chemical specificity [6]. |

Visualization of Concepts and Workflows

Protein Flexibility Analysis Workflow

This diagram outlines a logical workflow for integrating computational and experimental data to analyze protein flexibility.

Relationship Between Flexibility Drivers and Metrics

This diagram illustrates how intrinsic and extrinsic factors influence different flexibility metrics.

| Resource Name | Type | Function / Utility |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | MD Software Suite | A versatile package for performing MD simulations, energy minimization, and trajectory analysis. Highly optimized for performance [4] [13]. |

| CHARMM36m Force Field | Force Field Parameters | A set of parameters for MD simulations optimized for a balanced description of folded and disordered protein states [4]. |

| ATLAS Database | Database | A resource of standardized, all-atom MD simulations for a large, representative set of proteins, providing pre-computed flexibility metrics for comparison [4]. |

| AlphaFold2 / ColabFold | Structure Prediction Tool | Provides high-accuracy protein structure models and pLDDT confidence scores, useful for generating starting structures and initial flexibility estimates [12] [11]. |

| GENESIS | MD Software Suite | A simulation package specializing in enhanced sampling methods like REMD and GaMD, which are critical for studying complex conformational changes [15]. |

| Modeller / Chimera | Modeling Software | Tools for homology modeling and filling in missing atoms or loops in experimental protein structures, a critical step in preparing simulation inputs [4] [14]. |

The Direct Link Between Dynamics, Misfolding Diseases, and Drug Action

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Unphysical Ligand Unbinding in Steered Molecular Dynamics (SMD)

Problem: During SMD simulations, the ligand fails to exit the binding site cleanly or the entire protein-ligand complex drifts in the water solvent.

Explanation: A perfectly rigid protein backbone can force the ligand along an unnatural exit path, while an overly flexible protein allows the system to drift, preventing proper study of the unbinding event [3]. The goal is to apply restraints that mimic the natural context where the protein is embedded in a cellular environment.

Solution: Apply a harmonic restraint potential to the Cα atoms of the protein backbone that are more than 1.2 nm from the ligand [3]. This method provides a balance between a fully rigid protein and one that is too flexible.

- Steps:

- Identify Restraint Atoms: Calculate the distance from the ligand's center of mass to each Cα atom in the protein.

- Apply Restraints: Apply a harmonic restraint potential (e.g., using a force constant of 1000 kJ/mol/nm², as commonly used in equilibration protocols [4]) to all Cα atoms located more than 1.2 nm from the ligand.

- Run Simulation: Proceed with the SMD simulation. This setup is expected to lead to a more natural release of the ligand [3].

Guide 2: Handling System Instability During Molecular Dynamics Equilibration

Problem: The molecular system experiences large forces, crashes, or exhibits unnatural geometry during the initial equilibration phase of a simulation.

Explanation: Initial structures, especially those from modeling where side chains or loops have been added, can have atomic clashes or strained bonds. The equilibration phase allows the system to relax into a stable, energetically favorable state before data collection (production run).

Solution: A phased equilibration approach with positional restraints on the protein heavy atoms, which are gradually relaxed [4].

- Steps:

- Energy Minimization: Run an energy minimization (e.g., using the steepest descent algorithm for 5000 steps) to remove any bad van der Waals contacts [4].

- NVT Equilibration with Restraints: Equilibrate the system at constant volume and temperature (NVT ensemble) for 200 ps. During this phase, apply strong positional restraints (e.g., 1000 kJ/mol/nm²) on the protein's heavy atoms to allow the solvent to settle around the protein without the protein structure collapsing [4].

- NPT Equilibration with Restraints: Equilibrate the system at constant pressure and temperature (NPT ensemble) for 1 ns. Maintain the heavy atom restraints to allow the solvent density to stabilize [4].

- Production without Restraints: Release all positional restraints on the protein and run the production simulation.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why is protein flexibility so important in molecular dynamics studies related to drug design?

Protein flexibility is crucial because proteins are dynamic entities whose function often depends on conformational changes. For drug design, understanding how a ligand unbinds from its target, the residence time, and the dissociation rate is critical information that static structures cannot fully provide [3]. Flexibility allows for induced-fit binding, allosteric regulation, and is a key factor in diseases like misfolding disorders, where improper dynamics can lead to aggregation [6].

FAQ 2: My SMD simulation shows the ligand "smacking" into the wall of the binding site. What is the likely cause?

This is a known issue that can occur when the protein backbone is made too rigid, typically by restraining all heavy atoms or all Cα atoms. This excessive restraint prevents the protein from undergoing the natural, small-scale conformational adjustments that accompany ligand unbinding, forcing the ligand into an unnatural pathway [3].

FAQ 3: What are some reliable methods for quantifying protein flexibility from a simulation trajectory?

The most common metric is the Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) per residue, calculated from a Molecular Dynamics (MD) trajectory [6]. Other computational methods include Elastic Network Models (ENMs) like ProDy, which are faster than full MD and can predict large-scale collective motions [6]. Experimentally, X-ray crystallography B-factors can provide information on atomic mobility [4] [6].

FAQ 4: Where can I find standardized MD simulation data for a broad set of proteins to compare against my work?

The ATLAS database is a resource that provides standardized all-atom molecular dynamics simulations for a large, representative set of proteins [4]. It contains trajectories and analyses for over 1390 non-redundant protein domains, allowing for systematic comparison of protein dynamic properties [4].

Quantitative Data for Simulation Planning

The following table summarizes key parameters from established simulation protocols to assist in experimental design.

Table 1: Standardized Equilibration and Production MD Parameters

| Parameter | Equilibration (NVT) | Equilibration (NPT) | Production (NPT) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ensemble | Constant Volume, Temperature | Constant Pressure, Temperature | Constant Pressure, Temperature |

| Duration | 200 ps [4] | 1 ns [4] | 100 ns (per replicate) [4] |

| Time Step | 1 fs [4] | 2 fs [4] | 2 fs [4] |

| Temperature Coupling | Nosé-Hoover thermostat (300 K, τT = 1 ps) [4] | Nosé-Hoover thermostat (300 K, τT = 1 ps) [4] | Nosé-Hoover thermostat (300 K, τT = 1 ps) [4] |

| Pressure Coupling | Not Applicable | Parrinello-Rahman barostat (1 bar, τp = 5 ps) [4] | Parrinello-Rahman barostat (1 bar, τp = 5 ps) [4] |

| Positional Restraints | Heavy atoms (1000 kJ/mol/nm²) [4] | Heavy atoms (1000 kJ/mol/nm²) [4] | None [4] |

Experimental Protocol: Standard All-Atom MD Simulation

This protocol outlines the steps for setting up and running a standard all-atom molecular dynamics simulation, based on the methodology used for the ATLAS database [4].

Objective: To generate a trajectory of a protein's motion in a solvated, neutralized environment for analysis of its flexibility and dynamics.

Workflow:

Methodology:

System Preparation

- Protein Setup: Remove crystallographic water and ligands. Add missing hydrogen atoms and model any missing loops (using tools like MODELLER or AlphaFold2) [4].

- Force Field: Assign parameters using a force field like CHARMM36m or Amber ff99SB-ILDN [4] [3].

- Solvation: Place the protein in a periodic box (e.g., triclinic) with a minimum distance of 1.0 nm between the protein and box edge. Solvate with water molecules (e.g., TIP3P model) [4].

- Neutralization: Add ions (e.g., Na⁺/Cl⁻) to neutralize the system's net charge and then additional ions to achieve a physiological concentration (e.g., 150 mM) [4].

Energy Minimization

- Algorithm: Use the steepest descent algorithm for 5000 steps [4].

- Goal: Relieve any atomic clashes and high-energy configurations introduced during the setup process.

NVT Equilibration

NPT Equilibration

Production MD

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Resource | Category | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS [3] [4] | Software | A versatile and high-performance package for performing MD simulations. |

| CHARMM36m [4] | Force Field | A force field providing balanced sampling for folded and disordered proteins. |

| Amber ff99SB-ILDN [3] | Force Field | A widely used force field for protein simulations, particularly with the AMBER software. |

| GAFF (General Amber Force Field) [3] | Force Field | Used to derive parameters for small molecules (ligands) in simulations. |

| ATLAS [4] | Database | A database of standardized MD simulations for a large set of proteins, useful for comparison and benchmarking. |

| ProDy [6] | Software | An API and toolkit for performing Elastic Network Models and Normal Mode Analysis to predict protein dynamics. |

| Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) [3] | Algorithm | A standard method for handling long-range electrostatic interactions in MD simulations. |

| SHAKE [3] | Algorithm | A constraint algorithm used to "freeze" the bonds of hydrogen atoms, allowing for a longer simulation time step (e.g., 2 fs). |

The Modern Simulation Toolkit: AI, ML, and Advanced Sampling Techniques

The study of protein flexibility is fundamental to understanding biological functions, yet capturing these dynamic conformational changes computationally has remained a formidable challenge. Classical molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, while efficient, lack the chemical accuracy needed for precise mechanistic insights, while quantum mechanical methods like Density Functional Theory (DFT) provide accuracy but are computationally prohibitive for large biomolecules [17] [18]. The AI2BMD (AI-based ab initio biomolecular dynamics) system bridges this critical gap, enabling efficient simulation of full-atom large biomolecules with ab initio accuracy [17].

AI2BMD addresses the fundamental generalization problem in machine learning force fields (MLFFs) through a novel protein fragmentation scheme, breaking down proteins into manageable dipeptide units. This approach, combined with the ViSNet machine learning potential trained on 20.88 million DFT-level samples, allows the system to achieve accurate energy and force calculations for proteins exceeding 10,000 atoms while reducing computational time by several orders of magnitude compared to traditional DFT methods [17] [19]. For researchers investigating protein flexibility, this technological advancement enables the precise characterization of folding and unfolding processes, accurate free-energy calculations, and exploration of conformational spaces that were previously inaccessible [17] [18].

Core Architecture and Workflow

The AI2BMD framework employs a sophisticated computational pipeline that integrates physical fragmentation principles with deep learning architectures. The system's core innovation lies in its generalizable approach to handling proteins of varying sizes and complexities while maintaining quantum-mechanical accuracy.

Table: AI2BMD System Components and Functions

| Component | Function | Technical Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Fragmentation | Divides proteins into manageable units | Sliding window dipeptide fragmentation with ACE/NME capping |

| Machine Learning Potential (ViSNet) | Calculates energy and atomic forces | Geometry-enhanced graph neural network with linear time complexity |

| Solvent Handling | Models explicit solvent environment | Polarizable AMOEBA force field integration |

| Simulation Engine | Performs molecular dynamics simulations | Cloud-compatible AI-driven simulation program with GPU acceleration |

AI2BMD Simulation Workflow

Performance Metrics & Validation

Accuracy Assessment Against Reference Methods

AI2BMD demonstrates remarkable accuracy in both energy and force calculations when validated against DFT reference methods. The system substantially outperforms conventional molecular mechanics approaches across diverse protein systems.

Table: Accuracy Comparison of AI2BMD vs. Molecular Mechanics (MM)

| Protein System | Atoms | Method | Energy MAE (kcal/mol/atom) | Force MAE (kcal/mol/Å) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chignolin | 175 | AI2BMD | 0.038 | 1.974 |

| MM | 0.200 | 8.094 | ||

| Trp-cage | 281 | AI2BMD | 0.038 | 1.974 |

| MM | 0.200 | 8.094 | ||

| Albumin-binding domain | 746 | AI2BMD | 0.038 | 1.974 |

| MM | 0.200 | 8.094 | ||

| PACSIN3 | 1,040 | AI2BMD | 0.038 | 1.974 |

| MM | 0.200 | 8.094 | ||

| SSO0941 | 2,450 | AI2BMD | 0.0072 | 1.056 |

| MM | 0.214 | 8.392 |

Computational Efficiency Benchmarks

The computational efficiency of AI2BMD represents one of its most significant advantages, enabling previously impossible simulations of large biomolecular systems.

Table: Simulation Speed Comparison: AI2BMD vs. DFT

| Protein | Atoms | AI2BMD Time/Step (s) | DFT Time/Step | Speedup Factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trp-cage | 281 | 0.072 | 21 minutes | ~17,500x |

| Albumin-binding domain | 746 | 0.125 | 92 minutes | ~44,160x |

| Aminopeptidase N | 13,728 | 2.610 | >254 days | >8,000,000x |

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources for AI2BMD

| Resource/Reagent | Function/Purpose | Specifications/Requirements |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Unit Dataset | Training data for ML potential | 20.88 million dipeptide conformations with DFT-level energies/forces |

| ViSNet Model | Machine learning force field | Geometry-enhanced graph neural network for energy/force prediction |

| AIMD-Chig Dataset | Validation dataset | 2 million Chignolin conformations with DFT reference calculations |

| GPU Acceleration | Computational hardware | CUDA-enabled GPU (A100, V100, RTX A6000, Titan RTX) with 8+ GB memory |

| Docker Environment | Software containerization | Pre-configured runtime environment for consistent execution |

| AMOEBA Force Field | Polarizable solvent model | Explicit solvent handling for biomolecular simulations |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protein Preparation Protocol

Objective: Prepare protein structures compatible with AI2BMD simulation requirements.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Initial Structure Loading: Load your protein PDB file into PyMOL using command:

cmd.load("your_protein.pdb", "molecule") - Hydrogen Addition: Add missing hydrogen atoms with command:

cmd.h_add("molecule") - N-terminal Capping: Utilize PyMOL's mutagenesis wizard for ACE capping:

- C-terminal Capping: Apply NME capping similarly:

- Atom Name Standardization: Process with AmberTools' pdb4amber utility:

pdb4amber -i your_protein.pdb -o processed_protein.pdb - Structure Validation: Ensure the final PDB file:

- Contains no TER separators within the protein chain

- Has residue numbering starting from 1 without gaps

- Includes properly named ACE (C, O, CH3, H1, H2, H3) and NME (N, CH3, H, HH31, HH32, HH33) atoms [20]

Critical Notes: Currently, the machine learning potential does not optimally support proteins with disulfide bonds. Avoid structures with intrachain disulfide bridges until this limitation is addressed in future updates [20].

System Setup and Preprocessing Workflow

Objective: Establish solvated simulation system with proper equilibration.

Implementation Notes:

- FF19SB Method: Comprehensive protocol requiring AMBER software packages for optimal parallel CPU/GPU performance

- AMOEBA Method: Simplified approach with recommendation for additional pre-equilibrium simulations to ensure proper system relaxation

- Method Selection: Choose based on available computational resources and desired level of system preparation

Production Simulation Execution

Objective: Execute ab initio accuracy molecular dynamics simulations.

Command Line Implementation:

Critical Parameters:

--sim-steps: Number of simulation steps (adjust based on system size and simulation goals)--record-per-steps: Trajectory recording frequency--preprocess-dir: Directory containing preprocessed and solvated structure files

Simulation Modes:

- Fragment Mode (Default): Proteins fragmented into dipeptides with ML potential calculation at each step

- ViSNet Mode: Whole-protein energy/force calculation using custom-trained ViSNet models (requires

--ckpt-typeargument)

Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the specific terminal cap requirements for protein structures in AI2BMD?

AI2BMD requires neutral terminal caps with specific atom naming conventions. The N-terminus must be capped with an ACE (acetyl) group containing atoms named: C, O, CH3, H1, H2, H3. The C-terminus requires an NME (N-methyl) group with atoms named: N, CH3, H, HH31, HH32, HH33. These specifications ensure compatibility with the fragmentation algorithm and force field parameters. Use AmberTools' pdb4amber utility for atom name standardization after capping in PyMOL [20].

Q2: What hardware resources are essential for running AI2BMD simulations effectively?

The system requires x86-64 GNU/Linux systems with CUDA-enabled GPUs (8+ GB memory). Recommended GPUs include A100, V100, RTX A6000, or Titan RTX. For optimal performance, systems should have 8+ CPU cores and 32+ GB RAM. The program has been tested on Ubuntu 20.04 (Docker 27.1+) and ArchLinux (Docker 26.1+) environments. GPU memory requirements scale with protein size, with 13,728-atom systems successfully demonstrated on RTX A6000 (48 GB memory) [20].

Q3: How does AI2BMD handle proteins with disulfide bonds or non-standard residues?

Currently, the machine learning potential does not optimally support proteins with disulfide bonds. Researchers working with such proteins should await future updates addressing this limitation. For non-standard residues or modifications, the ViSNet mode with custom-trained models may offer a solution, though this requires generating appropriate training data and model retraining [20].

Q4: What is the significance of the fragmentation approach in achieving generalizability?

The protein fragmentation strategy decomposes proteins into 21 types of dipeptide units, creating a universal representation that applies to all proteins regardless of size or sequence. This approach enables the ML potential to learn local interactions comprehensively while avoiding the need for protein-specific training. The fragmentation handles inter-unit interactions through overlapping regions and systematic reassembly, ensuring accurate whole-protein energy and force calculations [17] [19].

Troubleshooting Guide

Table: Common AI2BMD Issues and Resolution Strategies

| Issue | Possible Causes | Resolution Steps |

|---|---|---|

| Simulation Collapse | Incorrect atom naming in terminal caps | Verify ACE/NME atom names using pdb4amber utility |

| GPU Memory Errors | Protein size exceeding available memory | Reduce system size or upgrade to higher memory GPU |

| Poor Performance | Insufficient CPU cores or outdated Docker | Ensure 8+ CPU cores and update Docker to latest version |

| Preprocess Failure | Missing hydrogen atoms or chain breaks | Use PyMOL to add hydrogens and ensure continuous chain |

| Generalization Errors | Unsupported residues or modifications | Stick to standard amino acids or train custom ViSNet model |

Installation Verification Protocol:

- Validate Docker installation:

docker --versionanddocker run hello-world - Confirm GPU accessibility within Docker environment

- Test with provided Chignolin example before moving to custom systems

- Verify output trajectory files in

Logs-[protein_name]directory

Applications in Protein Flexibility Research

AI2BMD enables unprecedented investigation of protein dynamic conformations, which are crucial for understanding biological function and dysfunction. The system can simulate folding and unfolding processes, capture intermediate states, and accurately compute thermodynamic properties that match experimental data [17] [18]. For drug discovery researchers, this capability is particularly valuable for studying conformational changes during drug-target binding, enzyme catalysis, and allosteric regulation [18].

The system's ability to explore diverse conformational spaces beyond what conventional MD can detect opens new opportunities for investigating intrinsically disordered proteins, multi-state proteins, and functional conformational transitions. Validation studies demonstrate AI2BMD's superior agreement with experimental measurements including J-coupling constants, folding free energies, melting temperatures, and pKa values [17] [18] [19]. This accuracy profile makes it particularly suitable for research requiring precise characterization of protein energy landscapes and dynamic behavior.

TECHNICAL SUPPORT CENTER: CGSchNet TROUBLESHOOTING

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My CGSchNet simulation fails to fold proteins to their native state. What could be wrong? A: This issue often stems from an under-trained model or insufficient conformational sampling. CGSchNet relies on a diverse training set of all-atom protein simulations to learn effective interactions. If the model was trained on an insufficient dataset or for too few epochs, it may not have learned the complex multi-body terms necessary for correct folding. Furthermore, for larger proteins, enhanced sampling techniques may be required to overcome free energy barriers. We recommend:

- Validate Training Data: Ensure the model was trained on a diverse set of proteins, including those with similar secondary structure elements to your target.

- Extended Sampling: Use advanced sampling techniques like parallel-tempering or the Weighted Ensemble (WE) method to improve exploration of conformational space [21] [22].

- Check Prior Energy: Control simulations with only the prior energy term should visit the unfolded state; if not, there may be an issue with the prior energy formulation [21].

Q2: How transferable is the CGSchNet force field, and can I use it on a protein with low sequence similarity to my training set? A: CGSchNet is designed for chemical transferability, meaning it can extrapolate to new sequences not used during parameterization. The model has been demonstrated to successfully simulate proteins with low (16–40%) sequence similarity to those in its training and validation datasets [21]. For example, it correctly predicted metastable states for proteins like chignolin, TRPcage, and the villin headpiece, which were not part of the initial training [21]. However, performance may vary for proteins with very distinct topological features. It is advisable to start with a benchmark on a known system to validate the model's performance for your specific protein class.

Q3: The fluctuations in my intrinsically disordered protein (IDP) simulation do not match experimental data. How can I improve this? A: Accurately simulating IDPs is a stringent test for any force field. CGSchNet has shown promise in predicting the fluctuations of intrinsically disordered proteins [23]. If discrepancies arise, consider:

- Training Set Composition: The model's accuracy for IDPs depends on the representation of disordered states in its training data. Ensure the original training set included sufficient conformational diversity, including unfolded and disordered states.

- Comparison Metric: Use multiple metrics for validation. Beyond root-mean-square fluctuation (r.m.s.f.), compare against experimental data from techniques like NMR or SAXS that are sensitive to disordered ensembles.

- Force-Matching Objective: The bottom-up training via force-matching aims to reproduce the all-atom equilibrium distribution; any systematic error in the reference atomistic data will be learned by the CG model [24].

Q4: My simulation is running slower than expected. What factors affect the computational performance of CGSchNet? A: While CGSchNet is several orders of magnitude faster than all-atom molecular dynamics [21], its performance is influenced by:

- Network Architecture: The underlying graph neural network (GNN) has a computational cost that scales with the number of particles and interactions.

- System Size: The efficiency gain over all-atom simulations becomes more pronounced for larger systems, as the cost of evaluating the neural network is amortized.

- Hardware: Utilizing GPUs that accelerate deep learning operations is crucial for optimal performance. The specialized SchNet architecture, with its continuous-filter convolutions, is designed for efficient evaluation [25].

Q5: How does CGSchNet ensure physical meaningfulness in its forces and prevent unphysical simulations? A: CGSchNet incorporates physics into its architecture and training in several ways:

- Equivariance: The network is built to be E(3)-equivariant, meaning its force predictions transform correctly under translation and rotation, a fundamental physical law [26].

- Prior Energy: A "regularized CGnet" includes a prior energy term based on physical knowledge (e.g., harmonic bonds, repulsive non-bonded terms). This ensures that for configurations far from the training data, the energy approaches infinity, producing a restoring force toward physical states and preventing catastrophic failures [24].

- Force-Matching: The model is trained using a variational force-matching objective, which ensures it learns a thermodynamically consistent potential of mean force (PMF) that reproduces the equilibrium distribution of the reference all-atom system [24] [25].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Inaccurate Free Energy Differences for Protein Mutants

Problem: The model predicts incorrect relative folding free energies (ΔΔG) for mutants, a key metric in protein engineering and drug discovery.

Investigation & Solutions:

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient sampling of folded and unfolded states. | Calculate the free energy landscape as a function of RMSD and fraction of native contacts (Q). Check for convergence. | Employ enhanced sampling (e.g., Parallel Tempering, WE) to ensure adequate sampling of all relevant basins [21] [22]. |

| Systematic error in the learned multi-body interactions for specific residue types. | Compare per-residue root-mean-square fluctuations (RMSF) against a reference all-atom simulation or experimental data (e.g., NMR). | Fine-tune the model on a small set of high-quality, target-specific all-atom simulations, if available. |

| Limitation of the CG representation in capturing atomic-level details of a mutation. | This is an inherent challenge of a Cα-based model. | Interpret results with caution for mutations that involve subtle changes in side-chain packing or electrostatic interactions. |

Issue: Simulation Instability (Energy Blow-Up)

Problem: The simulation crashes due to unphysically high energies, often manifested as atoms flying apart.

Investigation & Solutions:

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Extrapolation into unphysical regions of conformational space not seen during training. | Analyze the trajectory leading to the crash. Look for highly distorted bonds, angles, or steric clashes. | Utilize the regularized CGnet framework, which includes a physics-based prior energy that dominates and provides restoring forces for unphysical states [24]. |

| Numerical instabilities in the neural network or integrator. | Check for NaN or infinite values in force outputs. Validate the integration time step. | Reduce the simulation time step. Ensure stable training of the neural network force field by monitoring the loss function on a validation set. |

Issue: Poor Reproduction of Experimental Metastable States

Problem: The simulation fails to identify a known intermediate or misfolded state (e.g., a state relevant to amyloid formation).

Investigation & Solutions:

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| The free energy barrier to the metastable state is too high for spontaneous transitions in simulation time. | Use a collective variable (CV) that describes the transition to monitor sampling. | Integrate with Weighted Ensemble (WE) sampling. Define a progress coordinate (e.g., from TICA) and use WESTPA to efficiently sample rare transitions [22]. |

| The reference all-atom data used for training did not adequately sample these states. | Inspect the training data and the model's force-matching error in regions corresponding to the metastable state. | Retrain or fine-tune the model using a training set that includes enhanced sampling of the relevant intermediate states. |

QUANTITATIVE PERFORMANCE DATA

Table 1: CGSchNet Performance on Benchmark Protein Systems

This table summarizes key quantitative results from CGSchNet simulations, demonstrating its ability to predict folded states and dynamics across a range of proteins [21] [22].

| Protein (PDB ID) | Residues | Fold Type | CG Folded State Cα RMSD (nm) | CG Fraction of Native Contacts (Q) | Comparison to Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chignolin (2RVD) | 10 | β-hairpin | Low (~0.1-0.2) | ~1.0 | Correctly predicts folded basin and a misfolded state. |

| TRP-cage (2JOF) | 20 | α-helix | Low | ~1.0 | Folding/unfolding transitions match all-atom MD. |

| BBA (1FME) | 28 | ββα | ~0.3-0.5 | ~0.7-0.8 | Native state is a local minimum, performance less accurate. |

| Villin Headpiece (1ENH) | 35 | 3-helix | ~0.5 | ~0.75 | Similar terminal flexibility to all-atom MD; slightly higher fluctuations. |

| Homeodomain (1ENH) | 54 | 3-helix bundle | ~0.5 | ~0.75 | Similar folded state and terminal flexibility to all-atom MD. |

| alpha3D (2A3D) | 73 | 3-helix bundle | - | - | Folds to native structure; captures flexibility at termini and between helices. |

Table 2: Key Metrics for Benchmarking Machine-Learned Coarse-Grained Models

A standardized benchmark proposes over 19 metrics for rigorous evaluation. The following are critical for assessing performance [22].

| Metric Category | Specific Metrics | Description and Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Structural Fidelity | Contact Map Differences, Radius of Gyration (RoG) Distribution | Measures how well the model's equilibrium structures match the reference data. |

| Slow-Mode Accuracy | Time-lagged Independent Component Analysis (TICA) landscape, Markov State Model (MSM) timescales | Evaluates if the model captures the correct long-timescale dynamics and state-to-state transitions. |

| Statistical Consistency | Wasserstein-1 Distance, Kullback-Leibler (KL) Divergence for bonds, angles, dihedrals | Quantifies the statistical difference between the simulated and reference distributions of structural elements. |

| Thermodynamic Accuracy | Relative Folding Free Energy (ΔΔG) of mutants | A key test for applications in protein engineering and drug discovery. |

EXPERIMENTAL PROTOCOLS & METHODOLOGIES

Protocol 1: Bottom-Up Training of a CGSchNet Force Field

Objective: To learn a transferable coarse-grained force field from all-atom molecular dynamics data.

Methodology:

- Generate Reference Data: Run a large and diverse set of all-atom, explicit-solvent MD simulations of proteins. This dataset should include folded, unfolded, and intermediate states to ensure a representative sample of the free energy landscape [21] [24].

- Define Coarse-Grained Mapping: Map the all-atom configurations to a lower-resolution representation. A common choice is a Cα-only model, where each amino acid is represented by a single bead located at its Cα atom [24].

- Instantaneous Force Projection: For each all-atom configuration, project the instantaneous forces acting on all atoms onto the CG beads using a linear mapping operator, Ξ. This produces the "instantaneous coarse-grained force" or local mean force [25].

- Neural Network Training: Train a SchNet-based graph neural network (CGSchNet) to predict the CG forces. The network takes the CG coordinates as input and outputs a potential energy. The forces are derived as the negative gradient of this energy.

- Loss Function: The network is trained by minimizing the force-matching loss (mean squared error) between the forces predicted by the network and the instantaneous coarse-grained forces from the reference all-atom simulation [25]. This procedure variationally approximates the thermodynamically consistent potential of mean force (PMF).

Protocol 2: Enhanced Sampling with the Weighted Ensemble (WE) Method

Objective: To efficiently sample rare events (like folding/unfolding) and converge free energy estimates when using CGSchNet or other simulation engines [22].

Methodology:

- Define Progress Coordinate: Identify one or more collective variables (CVs) that describe the transition of interest (e.g., fraction of native contacts Q, Cα RMSD, or a TICA component).

- Initialize Walkers: Start multiple simulation trajectories ("walkers") from different regions of the conformational space. Each walker is assigned a statistical weight.

- Run Propagation Cycles:

- Propagate: Run each walker for a fixed, short simulation time using your dynamics engine (e.g., CGSchNet integrator).

- Checkpoint and Resample: Periodically, the progress of all walkers is assessed. Walkers in undersampled regions are split into multiple copies, while those in oversampled regions are pruned. Their weights are adjusted accordingly to maintain a unbiased representation.

- Continue: Repeat the propagation and resampling steps. This process adaptively allocates computational resources to regions that are difficult to sample, leading to rapid exploration of conformational space.

- Analysis: Analyze the entire ensemble of weighted trajectories to compute observables like free energies, transition rates, and pathways.

THE SCIENTIST'S TOOLKIT

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents & Computational Tools

| Item Name | Function / Relevance in CGSchNet Research |

|---|---|

| All-Atom MD Dataset | A diverse set of protein simulation data used as the ground truth for training the CG model via force-matching [21]. |

| CGSchNet Software | The graph neural network architecture that learns the many-body CG force field; provides E(3)-equivariance and transferability [21] [25]. |

| Weighted Ensemble Software (WESTPA) | An open-source package for performing WE simulations, crucial for benchmarking and enhancing sampling of rare events [22]. |

| OpenMM | A high-performance toolkit for molecular simulation, often used to generate reference all-atom data and sometimes as a backend propagator [22]. |

| Benchmark Protein Set | A standardized set of proteins (e.g., Chignolin, BBA, WW domain, λ-repressor) for consistent evaluation of simulation methods [22]. |

WORKFLOW DIAGRAMS

Figure 1: CGSchNet Development and Simulation Workflow

Figure 2: Weighted Ensemble Enhanced Sampling Cycle

Understanding protein dynamics is crucial for modern drug development, as proteins exist as ensembles of interconverting conformers, not single static structures [27]. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation serves as a "computational microscope" for observing these dynamic processes, but its effectiveness depends on both accuracy and efficiency [17]. Enhanced sampling techniques like metadynamics address a fundamental challenge: simulating rare biological events that occur on timescales beyond what conventional MD can practically achieve. These methods rely on identifying collective variables (CVs)—low-dimensional representations of complex system dynamics—to accelerate sampling of important conformational changes [28]. The integration of artificial intelligence has revolutionized this field by automating CV discovery and improving the efficiency of free energy calculations, particularly for studying protein flexibility and conformational plasticity [29].

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What are the most common signs of poorly chosen collective variables in metadynamics simulations?

Poor CV selection manifests through several observable symptoms in your simulations:

- Lack of convergence: The free energy estimate continues to drift significantly even after extended simulation time without stabilizing [30].

- Incomplete state sampling: The simulation fails to visit all relevant conformational states known from experimental data or previous simulations [29].

- Low reproducibility: Independent simulations using the same CVs produce substantially different free energy surfaces [31].

- High variance in CV space: The system exhibits unusually large fluctuations along the biased CVs without transitioning between states [28].

Q2: How can researchers validate that AI-discovered collective variables are physically meaningful?

Validation of AI-discovered CVs requires multiple complementary approaches:

- Experimental correlation: Compare simulation results with experimental observables such as NMR chemical shifts or J-couplings [17].

- Committor analysis: Test if the CV effectively predicts transition states by analyzing the probability of reaching different basins [32].

- Physical interpretability: Ensure the CV correlates with physically understandable features like dihedral angles, contact distances, or solvation parameters [29].

- Predictive performance: Validate that the CV can guide simulations to discover new conformational states that align with experimental evidence [29].

Q3: What troubleshooting steps should be taken when metadynamics simulations show poor convergence?

When facing convergence issues, systematically address these potential causes:

- Adjust metadynamics parameters: Reduce Gaussian height or increase pace (deposition frequency) to ensure slower, more adiabatic bias deposition [30].

- Extend simulation time: Some systems require significantly longer sampling, particularly for proteins with complex energy landscapes [31].

- Check CV suitability: Reevaluate whether your CVs adequately capture the true reaction coordinate using committor analysis or other validation methods [30].

- Implement well-tempered metadynamics: This variant reduces the bias deposition over time, improving convergence properties compared to standard metadynamics [30].

- Use multiple walkers: Parallel independent simulations can improve sampling efficiency and provide better error estimation [28].

Q4: How can researchers handle high-dimensional CV spaces without overwhelming computational cost?

Several strategies manage dimensionality in CV spaces:

- Dimensionality reduction: Employ techniques like variational autoencoders, principal component analysis, or deep learning encoders to project structural data into lower-dimensional latent spaces [29].

- Multi-step protocols: First identify important features through unbiased MD or short exploratory metadynamics, then focus enhanced sampling on the most relevant degrees of freedom [32].

- Sparse sampling: Use algorithms that automatically identify the most informative regions of CV space to prioritize sampling efforts [29].

- Linear combinations: Construct CVs as optimized linear combinations of simpler descriptors to reduce dimensionality while maintaining physical relevance [28].

Q5: What are the best practices for integrating AI-predicted protein structures with enhanced sampling methods?

When combining AI predictions with enhanced sampling:

- Treat as initial models: Use AI-generated structures (from AlphaFold, RosettaFold, etc.) as starting points, not final conformations [29].

- Account for uncertainty: Focus enhanced sampling on regions with low prediction confidence scores, as these often correspond to flexible, functionally important regions [29].

- Validate with physics: Use physics-based simulations to refine and validate AI-generated structures, particularly for flexible loops and active sites [29].

- Transfer learning: Fine-tune AI models on simulation data to improve predictions for specific protein families or conformational states [17].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Implementing Well-Tempered Metadynamics for Protein Conformational Sampling

This protocol provides a framework for applying well-tempered metadynamics to study protein conformational changes using commonly available MD software with PLUMED integration [30]:

Step 1: CV Selection and Definition

- Identify relevant collective variables through preliminary unbiased simulations and literature review

- Define CVs in the PLUMED input file, commonly using backbone dihedrals for protein folding studies:

Step 2: Metadynamics Parameters Setup

- Configure well-tempered metadynamics with appropriate parameters:

Step 3: Production Simulation

- Run extended simulation (typically 100-1000 ns depending on system complexity)

- Monitor convergence through free energy estimate stability

- Use multiple walkers for improved sampling and error estimation [28]

Step 4: Free Energy Analysis

- Reconstruct free energy surface from deposited Gaussians

- Perform block analysis to estimate statistical errors [31]

- Validate with experimental data where available

Table 1: Recommended Metadynamics Parameters for Different Protein Systems

| System Type | PACE (steps) | Initial HEIGHT (kJ/mol) | BIASFACTOR | Typical Simulation Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small peptide (e.g., dipeptide) | 500 | 1.2 | 8 | 50-100 ns |

| Medium protein domain | 500-1000 | 0.5-1.0 | 10-15 | 100-500 ns |

| Protein-ligand complex | 500-1000 | 0.5-1.0 | 10-15 | 200-1000 ns |

| Multi-domain protein | 1000-2000 | 0.3-0.8 | 15-20 | 500-2000 ns |

Protocol 2: Automated Collective Variable Discovery Using Variational Autoencoders

This methodology describes how to implement AI-driven CV discovery using neural networks, particularly useful when little prior knowledge exists about the system's dynamics [29]:

Step 1: Data Generation and Feature Selection

- Run short unbiased MD simulations (50-200 ns) to generate diverse conformational samples

- Extract relevant structural features (dihedral angles, distances, contacts) as input features

- Standardize and preprocess features for neural network training

Step 2: Neural Network Architecture Setup

- Implement a variational autoencoder with hyperspherical latent space

- Use appropriate architecture sizes based on input feature dimension:

Step 3: Model Training and Validation

- Train using combined reconstruction loss and KL-divergence regularization

- Validate through reconstruction accuracy and latent space interpretability

- Monitor training to prevent overfitting through early stopping

Step 4: CV Extraction and Implementation

- Use the latent space dimensions as collective variables in metadynamics

- Map latent space coordinates back to structural features for interpretation

- Validate CV quality through committor analysis and state discrimination

Table 2: Hyperparameter Recommendations for CV Discovery Networks

| Hyperparameter | Small System (<100 atoms) | Medium System (100-1000 atoms) | Large System (>1000 atoms) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Training Data Size | 10-50 ns trajectory | 50-200 ns trajectory | 200-500 ns trajectory |

| Input Features | 50-200 features | 200-1000 features | 1000-5000 features |

| Latent Space Dimension | 2-5 dimensions | 3-10 dimensions | 5-15 dimensions |

| Training Epochs | 100-500 | 200-1000 | 500-2000 |

| Batch Size | 64-128 | 128-512 | 256-1024 |

Workflow Visualization

AI-Enhanced Metadynamics Workflow for Protein Flexibility Studies

Table 3: Essential Software Tools for AI-Enhanced Metadynamics

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Application Context | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| PLUMED | Enhanced sampling & CV analysis | General biomolecular systems | Metadynamics, ABF, path metadynamics, extensive CV library [30] |

| Colvars Module | Collective variables & biasing | GROMACS-integrated simulations | Distance, angles, coordination numbers, RMSD, custom functions [28] |

| VAMPNet | Deep learning for molecular kinetics | Markov state model construction | Neural networks for slow CV discovery, state identification [29] |

| Deep-TICA | Nonlinear CV discovery | Rare event acceleration | Time-lagged autoencoders, slow feature analysis [29] |

| AI2BMD | AI-driven ab initio MD | Quantum-accurate protein simulations | Machine learning force fields, fragmentation approach [17] |

| MDAnalysis | Trajectory analysis & processing | Python-based analysis pipeline | Feature extraction, measurements, visualization [33] |

| VMD | Molecular visualization & analysis | Trajectory inspection & scripting | TCL scripting, structural alignment, measurement tools [33] |

Table 4: Key Machine Learning Frameworks for CV Discovery

| Framework/Method | ML Approach | Best For | Implementation Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variational Autoencoder (VAE) | Unsupervised dimensionality reduction | Learning low-dimensional manifolds from structural data [29] | Medium |