Beyond Static Snapshots: Validating Pharmacophore Models with Molecular Dynamics Simulations for Robust Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on integrating Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations into the pharmacophore model validation pipeline.

Beyond Static Snapshots: Validating Pharmacophore Models with Molecular Dynamics Simulations for Robust Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on integrating Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations into the pharmacophore model validation pipeline. It explores the foundational rationale for moving beyond static structures, detailing how MD simulations capture essential protein-ligand dynamics and conformational flexibility that are often missed. The piece offers a detailed methodological framework for implementing MD-driven validation, covering system setup, trajectory analysis, and dynamic pharmacophore generation. It further addresses common troubleshooting scenarios and provides optimization strategies to enhance model reliability. Finally, the article establishes rigorous validation protocols and comparative metrics, including enrichment calculations and ROC curve analysis, to quantify model performance and predictive power, ultimately bridging the gap between computational prediction and experimental success.

Why Static Models Fall Short: The Foundational Role of Dynamics in Pharmacophore Validation

Defining the Pharmacophore and the Critical Need for Validation

A pharmacophore is an abstract definition of the essential structural features and their spatial arrangements that a molecule must possess to elicit a specific biological response [1]. In practical terms, it represents the key molecular interactions—such as hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic contacts, and ionic interactions—that facilitate binding between a ligand and its biological target. The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) defines a pharmacophore as "an ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target and to trigger (or block) its biological response" [1]. In modern computational drug design, pharmacophores serve as versatile templates for navigating vast chemical spaces, enabling researchers to identify novel hit compounds through virtual screening and to guide the de novo design of molecules with desired biological activities.

The critical importance of pharmacophore validation stems from the model's foundational role in downstream decision-making. An unvalidated pharmacophore model can lead to false positives during virtual screening, misdirected synthetic efforts, and ultimately, costly experimental failures. Proper validation determines a model's predictive capability, applicability domain, and overall robustness, transforming it from a theoretical hypothesis into a reliable tool for drug discovery [2]. This article examines the methodologies for establishing pharmacophore validity and demonstrates how molecular dynamics simulations have become indispensable for confirming model robustness in structure-based drug design.

Essential Pharmacophore Features and Their Chemical Significance

Pharmacophore models are constructed from distinct chemical features that represent crucial interaction points between a ligand and its target protein. These features are derived from either known active ligands (ligand-based approaches) or protein-ligand complex structures (structure-based approaches) [1]. The table below summarizes the core pharmacophore features and their roles in molecular recognition.

Table 1: Fundamental Pharmacophore Features and Their Functional Roles

| Feature Type | Symbol | Chemical Groups | Role in Molecular Recognition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Bond Acceptor | HA | Carbonyl oxygen, Nitrogens in heterocycles | Accepts hydrogen bonds from donor groups (e.g., OH, NH) |

| Hydrogen Bond Donor | HD | Hydroxyl, Amine, Amide NH | Donates hydrogen bonds to acceptor groups |

| Hydrophobic | HY | Alkyl chains, Aromatic rings | Participates in van der Waals interactions with hydrophobic pockets |

| Positively Ionizable | PI | Primary amines, Guanidines | Forms salt bridges with negatively charged residues (e.g., Asp, Glu) |

| Negatively Ionizable | NI | Carboxylic acids, Phosphates, Tetrazoles | Forms salt bridges with positively charged residues (e.g., Arg, Lys, His) |

| Aromatic Ring | AR | Phenyl, Pyridine, Heterocycles | Engages in π-π stacking or cation-π interactions |

| Exclusion Volume | EV | N/A | Represents sterically forbidden regions of the binding site |

Beyond these standard features, more specialized interactions include metal coordination (e.g., with Zn²⁺ in metalloenzymes), cation-π interactions (between electron-rich aromatics and positively charged groups), and halogen bonds (where polarized halogens act as electrophiles) [3]. The spatial arrangement of these features—defined by distances and angles—creates a unique fingerprint that distinguishes active from inactive compounds. For directional features like hydrogen bond donors and acceptors, the geometry is often represented as vectors within a cone (for sp² hybridized atoms) or a torus (for sp³ hybridized atoms) to account for directional flexibility [1].

The Critical Imperative for Pharmacophore Validation

Pharmacophore model validation is not merely an optional step but a crucial process that determines the model's reliability for practical application. Without rigorous validation, researchers risk pursuing false leads, misallocating resources, and ultimately failing to identify genuine active compounds [2]. The validation process answers fundamental questions about the model: Can it distinguish known active compounds from inactive ones? Does it generalize to new chemical scaffolds? Are its predictions statistically significant, or could they arise by chance?

A properly validated pharmacophore model must demonstrate several key characteristics. It must exhibit high sensitivity (the ability to correctly identify active compounds) and high specificity (the ability to reject inactive compounds) [4]. The model should also show statistical significance, proving that its performance is not due to random chance, and predictive power, enabling the identification of novel active compounds not used in the model's construction [2]. Additionally, the model must display robustness across different chemical classes and experimental conditions. Failure to validate a pharmacophore model adequately can lead to several critical pitfalls, including enrichment of false positives in virtual screening, wasted synthetic chemistry resources on inactive compounds, and incorrect structure-activity relationship interpretations that misdirect lead optimization efforts [2] [4].

Comprehensive Pharmacophore Validation Methodologies

Statistical Validation Protocols

Statistical validation methods provide quantitative assessments of a pharmacophore model's ability to discriminate between active and inactive compounds. These methods employ carefully designed test sets and statistical metrics to evaluate model performance objectively [2].

Table 2: Key Metrics for Statistical Validation of Pharmacophore Models

| Metric | Calculation Formula | Interpretation | Threshold for Reliability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enrichment Factor (EF) | ( EF = \frac{Ha \times D}{Ht \times A} ) | Measures the model's ability to enrich active compounds from a database | >2.0 [5] [6] |

| Goodness of Hit (GH) | ( GH = \left( \frac{Ha}{4HtA} \right) \times (3A + H_t) ) | Combined metric of yield and enrichment | 0.6-0.8 (Excellent) |

| Sensitivity (Recall) | ( Sensitivity = \frac{H_a}{A} \times 100 ) | Percentage of actives correctly identified | Higher values preferred |

| Specificity | ( Specificity = \frac{TN}{TN + FP} \times 100 ) | Percentage of inactives correctly rejected | Higher values preferred |

| Area Under Curve (AUC) | Area under ROC curve | Overall discrimination power | >0.7 [5] [6] |

Where: (H_a) = number of active compounds retrieved (true positives); (H_t) = total number of hits retrieved; (A) = total number of active compounds in database; (D) = total number of compounds in database; (TN) = true negatives; (FP) = false positives.

The Fischer randomization test is another crucial validation step that assesses the statistical significance of a pharmacophore model [2]. In this test, the biological activity data for the training set compounds are randomly shuffled, and new pharmacophore models are generated from this randomized data. This process is repeated multiple times (typically 50-100 iterations) to create a distribution of randomized models. If the original model's performance metrics (e.g., correlation coefficient) fall within the extreme tails of the randomized distribution (e.g., p < 0.05), it indicates that the original model captures a meaningful structure-activity relationship rather than a chance correlation [2].

The decoys set validation approach evaluates a model's ability to distinguish known active compounds from physically similar but chemically distinct inactive molecules (decoys) [2]. Decoys are generated to match the physical properties (e.g., molecular weight, logP, hydrogen bond donors/acceptors) of active compounds while differing in chemical structure to avoid actual activity. The model's performance is then assessed using metrics such as the enrichment factor and the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC-ROC) [5] [6]. A reliable pharmacophore model should retrieve a significantly higher proportion of active compounds compared to decoys, demonstrating its specificity for biologically relevant features.

Experimental Workflow for Pharmacophore Validation

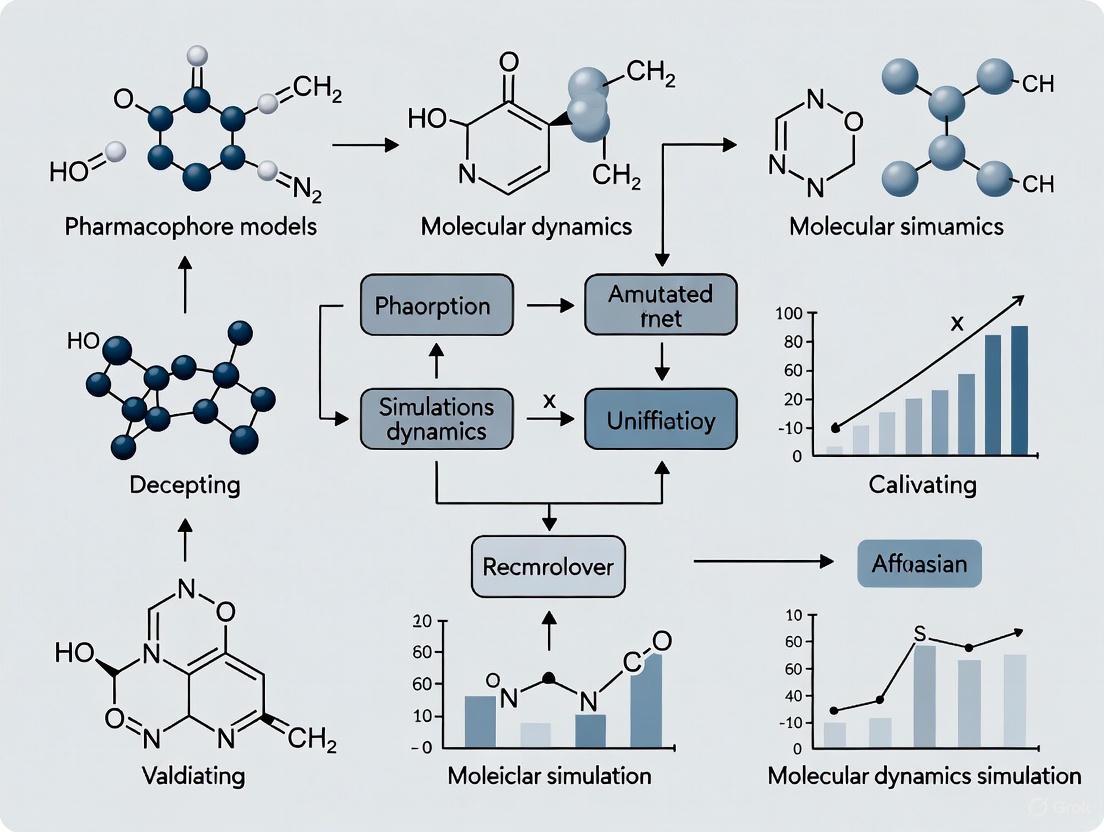

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for developing and validating a pharmacophore model, integrating both computational and experimental approaches:

Molecular Dynamics Simulations as a Validation Tool

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have emerged as a powerful method for pharmacophore validation, providing atomic-level insights into the stability and dynamics of protein-ligand interactions over time. Unlike static structure-based approaches, MD simulations capture the flexible nature of both the receptor and ligand, revealing conformational changes and interaction patterns that may be missed in single crystal structures [4] [7].

In recent studies, MD simulations have proven particularly valuable for validating pharmacophore models by demonstrating that predicted interactions remain stable under dynamic conditions. For instance, in a study targeting Focal Adhesion Kinase 1 (FAK1), researchers used 100 ns MD simulations to validate the stability of four potential inhibitor complexes identified through pharmacophore screening [4]. Similarly, in the identification of VEGFR-2/c-Met dual inhibitors, MD simulations confirmed that hit compounds maintained stable interactions with both targets throughout 100 ns simulation periods [6]. These simulations provide critical validation that the pharmacophore features represent genuine, persistent interactions rather than transient contacts.

The integration of MD with Molecular Mechanics/Generalized Born Surface Area (MM/GBSA) or Molecular Mechanics/Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area (MM/PBSA) calculations enables the quantification of binding free energies, offering a more reliable assessment of binding affinity than docking scores alone [4] [6]. For example, in the FAK1 study, MM/PBSA calculations revealed that candidate ZINC23845603 exhibited strong binding free energies and interaction features similar to the known ligand P4N, providing strong validation for the pharmacophore model used to identify it [4].

Recent advancements have further enhanced the role of MD in validation workflows. The development of active learning frameworks that combine MD with machine learning has dramatically improved the efficiency of virtual screening, reducing the number of compounds requiring experimental testing while maintaining high accuracy [7]. Additionally, the use of receptor ensembles derived from MD simulations accounts for protein flexibility, enabling more comprehensive validation of pharmacophore models against multiple receptor conformations [7].

Comparative Analysis of Validation Approaches

The table below provides a comparative analysis of different pharmacophore validation approaches, highlighting their respective strengths, limitations, and appropriate use cases:

Table 3: Comparative Analysis of Pharmacophore Validation Methods

| Validation Method | Key Metrics | Advantages | Limitations | Case Study Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical Validation | EF, GH, AUC [5] | Fast, quantitative, does not require experimental resources | May overfit to training set chemistry; depends on quality of test sets | EF>2.0, AUC>0.7 for reliable VEGFR-2/c-Met models [6] |

| Fischer Randomization | p-value <0.05 [2] | Tests statistical significance; avoids chance correlations | Computationally intensive for large datasets | 95% confidence level for significant FAK1 model [4] |

| Decoy Set Validation | EF, ROC curves [2] | Uses physically similar but inactive compounds; realistic assessment | Decoy quality affects results; may miss false negatives | Successful identification of true actives from DUD-E database [4] |

| Molecular Dynamics | RMSD, RMSF, H-bonds, binding free energy [4] | Accounts for flexibility; provides dynamic interaction profile | Computationally expensive; requires significant expertise | 100 ns simulations confirmed stability of FAK1 inhibitors [4] |

| Experimental Testing | IC₅₀, Ki, functional activity | Ultimate validation; provides biological confirmation | Resource-intensive; requires compound synthesis/purchase | Identified BMS-262084 as potent TMPRSS2 inhibitor (IC₅₀=1.82 nM) [7] |

The integration of multiple validation methods provides the most robust assessment of pharmacophore quality. For example, in the identification of novel FAK1 inhibitors, researchers employed a comprehensive strategy that included cost function analysis, Fischer randomization, decoy set validation, and finally MD simulations with MM/PBSA calculations [4]. This multi-stage approach ensured that the pharmacophore model was statistically sound, capable of discriminating actives from inactives, and produced stable binding interactions confirmed by dynamic simulations.

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Successful pharmacophore development and validation requires a suite of specialized software tools and research reagents. The table below summarizes key resources used in contemporary pharmacophore studies:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Pharmacophore Studies

| Tool Category | Specific Tools | Primary Function | Application in Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmacophore Modeling | Discovery Studio [6], PHASE [3], Pharmit [4] | Model generation and hypothesis testing | Create and refine pharmacophore hypotheses based on structural data |

| Virtual Screening | ZINC [4], ChemDiv [6], DUD-E [4] | Compound libraries for screening | Provide active/decoy compounds for model validation |

| Molecular Docking | AutoDock Vina [4], SwissDock [4] | Binding pose prediction | Generate initial complexes for MD simulations |

| Dynamics & Analysis | GROMACS [4], AMBER [1] | MD simulations and trajectory analysis | Assess complex stability and interaction persistence |

| Binding Energy | MM/PBSA, MM/GBSA [4] [6] | Free energy calculations | Quantify binding affinities for validation |

| AI-Enhanced Tools | DiffPhore [3], PGMG [8], Active Learning [7] | Deep learning approaches | Improve screening efficiency and pose prediction |

Specialized databases play a crucial role in pharmacophore validation. The Directory of Useful Decoys: Enhanced (DUD-E) provides carefully curated decoy molecules that match the physical properties of active compounds while differing chemically, enabling rigorous validation of model specificity [4]. The PDBbind database offers experimental protein-ligand complex structures with associated binding affinity data, serving as a valuable benchmark for validating computational methods [3]. For large-scale virtual screening, commercial databases such as ChemDiv and public repositories like ZINC provide extensive compound libraries for testing pharmacophore models [4] [6].

Integrated Validation Workflow: A Case Study Approach

The following diagram illustrates how molecular dynamics simulations integrate with other validation methods in a comprehensive workflow, using the identification of novel FAK1 inhibitors as a case study [4]:

This integrated approach demonstrates how MD simulations serve as a crucial bridge between computational prediction and experimental validation. In the FAK1 case study, this workflow led to the identification of ZINC23845603 as a promising candidate with strong binding free energy (-68.4 kcal/mol) and interaction features similar to the known ligand P4N [4]. The compound maintained stable interactions throughout the 100 ns simulation, with key pharmacophore features consistently engaged with the target binding site.

The validation of pharmacophore models requires a multifaceted approach that combines statistical, computational, and experimental methods. Through comprehensive case studies and emerging methodologies, several best practices have emerged. Employ multiple validation methods rather than relying on a single metric, as each approach provides complementary information about model quality. Integrate molecular dynamics simulations to assess the stability of predicted interactions under dynamic conditions, as this provides critical insights beyond static docking poses. Utilize rigorous statistical testing including Fischer randomization and decoy set validation to ensure model significance and specificity. Correlate computational predictions with experimental data whenever possible, as biological activity remains the ultimate validation of any pharmacophore model.

The field continues to evolve with the integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning methods. Approaches like DiffPhore for 3D ligand-pharmacophore mapping [3] and active learning frameworks that combine MD with efficient screening [7] represent the next generation of pharmacophore tools. These advancements promise to enhance both the accuracy and efficiency of pharmacophore validation, further solidifying its role as a cornerstone of modern structure-based drug design. As these methodologies mature, the comprehensive validation paradigm presented here will remain essential for distinguishing robust, predictive pharmacophore models from those that merely fit training data without genuine predictive power.

In structure-based drug design, the traditional approach has often relied on static protein structures, typically obtained from X-ray crystallography, to visualize drug targets and predict how potential therapeutics might bind. However, proteins and ligands are not static entities; they exhibit constant motion, fluctuating between different conformational states in solution. These inherent dynamics are crucial for understanding protein function and facilitating drug discovery, as the therapeutic effect of drug molecules arises from their specific binding to only some conformations of the target proteins, thereby modulating essential biological activities by altering the conformational landscape [9]. Despite the widespread recognition of the importance of protein dynamics, traditional computational methods frequently treat proteins as rigid or only partially flexible to manage computational costs, leading to potentially inaccurate predictions [9].

The limitations of static structures become particularly evident when using AlphaFold-predicted structures of apoproteins as inputs for docking, as this often yields ligand pose predictions that do not align well with ligand-bound co-crystallized holo-structures [9]. The AlphaFold-predicted structures often do not present the most favorable side-chain rotamer configurations for ligand binding, making relevant binding pockets appear inaccessible since the apoprotein adopts a conformation substantially different from the holo state. This review comprehensively compares computational approaches that address molecular flexibility, highlighting how integrating dynamic simulations validates and enhances traditional methods, with particular focus on experimental data demonstrating performance advantages of dynamic approaches.

Theoretical Framework: From Static Snapshots to Dynamic Ensembles

The Thermodynamic Basis of Binding

Theoretical principles explain why flexibility profoundly impacts molecular recognition and binding. A thermodynamic ensemble of a protein-ligand system represents a distribution of complex conformations in equilibrium, with varying probabilities of occurrence that collectively depict the free energy state of the system [10]. The binding affinity (Kᵢ) is determined by the Gibbs free energy change (ΔG) of the binding process, which can be defined as: -RTlnKᵢ = ΔG = ΔGgas + ΔGsolv, where R represents the molar gas constant, T represents the temperature, ΔGgas stands for the binding free energy between the pair of protein and ligand in the gas phase, and ΔGsolv stands for the solvation free energy difference [10]. Both ΔGgas and ΔGsolv can be represented by the ensemble-averaged energy terms related to the atomic features derived from each snapshot in a dynamic simulation.

Static structures represent merely single snapshots of this complex energetic landscape, potentially missing crucial conformational states that contribute significantly to the binding process. Molecular dynamics simulations can approximate such thermodynamic ensembles by sampling multiple conformations, thereby providing a more complete picture of the free energy state of ligand binding [10]. Analysis of MD trajectories has revealed that conformations exhibit varying stability levels, and ligand stabilities roughly inversely correlate with binding affinities, with the upper bound for the mean RMSD of the ligand decreasing as binding affinity increases [10].

Pharmacophore Models: Incorporating Flexibility

Pharmacophore modeling represents another approach to address molecular flexibility, defined as "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target and to trigger (or block) its biological response" [11]. While pharmacophore models can be derived from static structures, they fundamentally represent abstract patterns of features rather than fixed chemical groups, allowing for some inherent flexibility in ligand recognition.

The two primary methods for pharmacophore modeling are ligand-based and structure-based approaches. Ligand-based pharmacophore modeling relies on the common features of a set of active ligands, while structure-based pharmacophore modeling uses the 3D structure of a protein to identify potential ligands [12]. Hybrid pharmacophore modeling combines the advantages of both approaches, making it a powerful tool for drug discovery [12]. Recently, MD-derived pharmacophore modeling has emerged as an advanced technique that captures dynamic interaction patterns from simulation trajectories rather than single static structures [13].

Performance Comparison: Rigid Versus Flexible Approaches

Docking and Virtual Screening Performance

To quantitatively assess the impact of incorporating flexibility, we compared several computational approaches using standardized benchmarks. The following table summarizes key performance metrics across different methods:

Table 1: Performance comparison of structure-based drug design methods on standardized benchmarks

| Method | Approach to Flexibility | Ligand RMSD <2Å (%) | Ligand RMSD <5Å (%) | Success Rate (RMSD<2Å & Clash<0.35) | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DynamicBind [9] | Full flexibility (equivariant geometric diffusion) | 33-39% | 65-68% | 33% | Accommodates large conformational changes, identifies cryptic pockets |

| Traditional Docking [9] | Rigid or partially flexible | Not reported | Not reported | ~19% (best baseline) | Fast computation, high throughput |

| MD-Derived Pharmacophore [13] | MD ensemble-based | Qualitative improvement in binding mode prediction | N/A | N/A | Captures realistic interaction patterns, improves selectivity prediction |

| Dynaformer [10] | MD ensemble-based affinity prediction | N/A | Superior ranking power on CASF-2016 | N/A | State-of-the-art binding affinity prediction |

DynamicBind demonstrates particularly notable advantages in recovering ligand-specific conformations from unbound protein structures without needing holo-structures or extensive sampling [9]. It employs equivariant geometric diffusion networks to construct a smooth energy landscape that promotes efficient transitions between different equilibrium states, accurately accommodating a wide range of large protein conformational changes, such as the well-known DFG-in to DFG-out transition in kinase proteins [9].

Virtual Screening and Binding Affinity Prediction

For binding affinity prediction and virtual screening, methods incorporating dynamics consistently outperform static approaches:

Table 2: Performance in virtual screening and affinity prediction

| Method | Basis | CASF-2016 Ranking Power | Hit Rate Experimental Validation | Key Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dynaformer [10] | MD trajectories + graph transformer | State-of-the-art | 12 hits (2 submicromolar) for HSP90 | Binding affinity prediction |

| Structure-Based Pharmacophore [14] | Static structure + docking | N/A | Identified novel inhibitors for W. chondrophila | Target identification and inhibition |

| MD-Derived Pharmacophore [13] | MD trajectories | Enabled understanding of KV10.1/hERG selectivity | Explained structure-activity relationships | Binding mode analysis, selectivity |

In a virtual screening application for heat shock protein 90 (HSP90) inhibitors, Dynaformer identified 20 candidates whose binding affinities were experimentally validated, revealing 12 hit compounds including two in the submicromolar range and several novel scaffolds [10]. This demonstrates the practical utility of dynamic approaches in real-world drug discovery campaigns.

Methodological Approaches and Experimental Protocols

Molecular Dynamics-Derived Pharmacophore Modeling

The protocol for MD-derived pharmacophore modeling involves multiple steps that combine simulation with feature extraction [13]:

System Preparation: Begin with a protein-ligand complex structure, preferably from experimental data or high-quality homology models. For membrane proteins like KV10.1, use membrane builder tools such as CHARMM-GUI to incorporate appropriate lipid bilayers.

Molecular Dynamics Simulation: Perform MD simulations using software such as NAMD with the CHARMM36 force field. Typical production runs may extend to 100 nanoseconds or longer, with coordinates saved at regular intervals (e.g., every 100ps).

Trajectory Analysis: Using tools like LigandScout, analyze the MD trajectories to identify persistent interactions between the ligand and protein. Key interactions include hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, ionic interactions, and aromatic π-stacking.

Pharmacophore Feature Extraction: Derive pharmacophore features from the predominant interaction patterns observed throughout the simulation. The resulting model represents the essential interactions maintained during the dynamic binding process.

Model Validation: Validate the pharmacophore model by screening known active and inactive compounds, assessing its ability to discriminate true binders from non-binders.

In the KV10.1 potassium channel study, this approach revealed how non-selective inhibitors disrupt the π-π network of aromatic residues F359, Y464, and F468, explaining why targeting the channel pore results in undesired hERG inhibition and providing guidance for developing selective anticancer agents [13].

Deep Learning Approaches for Dynamic Docking

DynamicBind implements a sophisticated deep learning workflow for dynamic docking that differs substantially from traditional methods [9]:

Input Preparation: Accept apo-like structures (AlphaFold-predicted conformations) and small-molecule ligands in SMILES or SDF format.

Initial Placement: Randomly place the ligand, with seed conformation generated using RDKit, around the protein.

Iterative Refinement: Through 20 iterations with progressively smaller time steps, the model gradually translates and rotates the ligand while adjusting its internal torsional angles. After the initial five steps where only ligand conformation changes, the model simultaneously translates and rotates protein residues while modifying side-chain chi angles.

Equivariant Processing: At each step, features and coordinates are processed through an SE(3)-equivariant interaction module, with protein and readout modules generating predicted translation, rotation, and dihedral updates.

Conformation Selection: Generate diverse conformations and employ a contact-LDDT (cLDDT) scoring module, inspired by AlphaFold's LDDT score, to select the most suitable complex structure from predicted outputs.

This approach creates a funneled energy landscape that minimizes frustration between biologically relevant states, enabling efficient sampling of large conformational changes that would be prohibitively expensive with conventional MD [9].

Integrated Workflow for Dynamic Structure-Based Drug Design

The following workflow diagram illustrates how molecular dynamics simulations integrate with pharmacophore modeling and docking to create a comprehensive drug design pipeline:

Diagram 1: Integrated workflow for dynamic structure-based drug design

Successful implementation of dynamic approaches in drug discovery requires specific computational tools and resources:

Table 3: Essential research reagents and computational resources

| Resource Category | Specific Tools | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| MD Simulation Software | NAMD [13], GROMACS, CHARMM [13] | Atomistic molecular dynamics simulations | Sampling conformational ensembles, binding pathway analysis |

| Analysis Tools | LigandScout [13], VMD, MDAnalysis | Trajectory analysis and pharmacophore feature extraction | Identifying persistent interactions, binding pocket dynamics |

| Docking Software | MOE [15], Schrödinger Glide [13], AutoDock Vina | Molecular docking with various scoring functions | Pose prediction, virtual screening |

| Force Fields | CHARMM36 [13], AMBER, OPLS-AA | Molecular mechanics parameters | Energy calculations during MD simulations |

| Deep Learning Frameworks | PyTorch, TensorFlow | Implementing geometric deep learning models | DynamicBind, Dynaformer [9] [10] |

| Benchmark Datasets | PDBbind [9] [10] [15], CASF [15] | Standardized performance assessment | Method validation and comparison |

Case Studies: Practical Applications and Validation

Cryptic Pocket Identification in Unseen Targets

DynamicBind has demonstrated remarkable capability in identifying cryptic pockets in unseen protein targets [9]. In one case study, the method accommodated large conformational changes that revealed binding pockets not apparent in the initial AlphaFold-predicted structures. This capability is particularly valuable for targeting previously undruggable proteins, as cryptic pockets often represent alternative binding sites that can be exploited for therapeutic intervention. The method's generative approach enables exploration of conformational space beyond local minima, effectively predicting ligand-bound states from apo-like starting structures.

Selective Kinase Inhibitor Design

The MD-derived pharmacophore approach applied to KV10.1 potassium channels provided critical insights for selective kinase inhibitor design [13]. By analyzing molecular dynamics trajectories, researchers discovered that non-selective inhibitors disrupted the conserved π-π network of aromatic residues in the channel pore, a mechanism shared with the cardiac hERG channel. This understanding guided the design of compounds targeting alternative sites, improving selectivity and reducing cardiotoxicity risks. The pharmacophore model derived from MD simulations captured essential features for KV10.1 inhibition while highlighting similarities with hERG pharmacophores, enabling rational design of selective anticancer agents.

Natural Product Inhibitor Discovery

An integrated approach combining pharmacophore modeling, molecular docking, and MD simulations identified novel natural product inhibitors for Apoptosis Signal-Regulating Kinase 1 (ASK1) [16]. Compounds SN0030543, SN035314, and SN0330056 exhibited superior docking scores (-14.240 kcal/mol, -12.00 kcal/mol, and -11.054 kcal/mol, respectively) compared to the bound ligand (-10.785 kcal/mol). Subsequent 100-nanosecond MD simulations confirmed stable binding interactions, and MMGBSA calculations corroborated significant binding affinities. This case study demonstrates how dynamic simulations validate and refine initial hits from virtual screening, prioritizing compounds for experimental validation.

The limitations of static structures in capturing protein-ligand interactions are effectively addressed by incorporating molecular flexibility through advanced computational methods. Quantitative comparisons demonstrate that dynamic approaches consistently outperform rigid docking in pose prediction accuracy, virtual screening hit rates, and binding affinity prediction. Molecular dynamics-derived pharmacophore models provide more realistic representations of interaction patterns, while deep learning methods like DynamicBind and Dynaformer enable efficient sampling of conformational space beyond the capabilities of traditional MD.

The integration of these dynamic methods creates a powerful framework for structure-based drug design, moving beyond single static snapshots to embrace the ensemble nature of molecular recognition. As these methodologies continue to evolve, they promise to expand the druggable genome by targeting cryptic pockets and addressing previously undruggable targets, ultimately accelerating the discovery of novel therapeutics for challenging disease targets.

Molecular Dynamics as a Tool for Sampling Biological Reality

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have emerged as a crucial computational technique that moves beyond static structural images to sample the dynamic reality of biological systems. By solving Newton's equations of motion for all atoms in a system, MD simulations provide trajectories that reveal how proteins and ligands "jiggle and wiggle" over time—capturing essential motions that govern biological function and molecular recognition [17]. This capability is particularly valuable in structure-based drug design, where traditional methods often rely on single, static crystal structures that may not represent the physiological flexibility of protein targets [18].

The integration of MD with pharmacophore modeling represents a significant advancement in computational drug discovery. Traditional pharmacophore models derived from static crystal structures can be limited by structural artifacts from crystallography and their inability to account for protein flexibility [18]. MD-refined pharmacophore models address these limitations by sampling multiple conformational states, leading to improved performance in virtual screening and a more realistic representation of the dynamic interaction patterns between drugs and their targets [19]. This guide examines how MD simulations serve as a tool for sampling biological reality, comparing methodological approaches and providing experimental validation of their utility in pharmacophore model development.

MD-Refined vs. Static Pharmacophore Models: A Performance Comparison

Quantitative Evidence of Enhanced Performance

Multiple studies have directly compared the performance of MD-refined pharmacophore models against those derived from static crystal structures. The quantitative metrics consistently demonstrate the superiority of dynamics-informed approaches.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Static vs. MD-Refined Pharmacophore Models

| Study System | Static Model Performance (AUC/EF) | MD-Refined Model Performance (AUC/EF) | Key Improvement Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CDK-2 Inhibitors | ROC₅% = 0.89-0.94 | ROC₅% = 0.98-0.99 | ~10% increase in early enrichment | [19] |

| Multiple Kinase Systems | Varies by system | Significant improvement in 4/6 systems | Better feature definition and retention | [18] |

| XIAP Protein | Not applicable | EF₁% = 10.0, AUC = 0.98 | Excellent early enrichment | [20] |

| Common Hit Approach (CHA) | Baseline | ROC₅% = 0.99 with multiple complexes | Optimal with multiple target-ligand complexes | [19] |

In a comprehensive study of six protein-ligand systems, researchers found that pharmacophore models built from the final frames of MD simulations differed significantly from those derived from initial crystal structures in both feature number and feature type [18]. These structural differences translated into improved functional performance, with MD-refined models demonstrating superior ability to distinguish between active and decoy compounds in virtual screening [18].

Methodological Basis for Performance Improvements

The enhanced performance of MD-refined pharmacophore models stems from their ability to address fundamental limitations of static structures. Molecular dynamics simulations resolve uncertainties in crystal structures, including potential errors in ligand fidelity and non-physiological crystal contacts [18]. By simulating the system in solution under physiological conditions, MD provides a more realistic representation of the protein-ligand interaction patterns that occur in biological systems.

Additionally, MD simulations enable the identification of persistent interactions that remain stable throughout the simulation trajectory, distinguishing them from transient contacts that may be less critical for binding [19]. This temporal dimension allows researchers to weight pharmacophore features according to their stability and frequency, creating models that better reflect the essential interactions required for biological activity.

Experimental Protocols for MD-Enhanced Pharmacophore Modeling

Standard Workflow for MD-Refined Pharmacophore Development

The general methodology for developing MD-refined pharmacophore models follows a systematic workflow that integrates simulation with feature analysis.

Diagram 1: Workflow for MD-Refined Pharmacophore Model Development

Detailed Methodological Specifications

System Preparation and Force Field Selection

- Structure Source: Initial coordinates are typically obtained from the Protein Data Bank (PDB), with careful attention to resolution quality and completeness [4] [20].

- Missing Residues: Gaps in crystal structures must be modeled using tools like MODELLER, with selection based on lowest zDOPE scores [4].

- Protonation States: Histidine protonation and other ambiguous residues are determined using tools like PDB2PQR at physiological pH [21].

- Force Fields: Common choices include AMBER-ff19SB for proteins [21] and GAFF2 for small molecules [21], with CHARMM [17] and GROMOS [17] also representing well-validated alternatives.

Molecular Dynamics Simulation Parameters

- Solvation: Systems are solvated in explicit water models (typically TIP3P) with a 10Å water layer from the protein surface [21].

- Neutralization: Counterions (Na+/Cl-) are added to achieve system neutrality [21].

- Minimization and Equilibration: Systems undergo steepest descent/conjugate gradient minimization followed by gradual heating to 300K with positional restraints [21].

- Production Run: Unrestrained simulations in isothermal-isobaric ensemble (NPT) at 300K and 1 bar pressure [21].

Trajectory Analysis and Pharmacophore Generation

- Snapshot Extraction: Configurations are saved at regular intervals (typically 1-100ps) throughout the simulation [19].

- Feature Mapping: Interaction patterns are analyzed using specialized software (LigandScout, Pharmit) to identify persistent pharmacophore features [18] [20].

- Model Selection: Multiple pharmacophore hypotheses may be generated and validated to select the most statistically reliable model [4].

Advanced Methodologies: Beyond Basic MD Refinement

Water-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

An emerging approach utilizes MD simulations of apo protein structures to generate pharmacophore models based on the dynamics of explicit water molecules within water-filled binding sites [21]. This method involves:

- Running MD simulations of ligand-free, solvated protein structures

- Generating dynamic molecular interaction fields (dMIFs) from water molecule properties

- Converting these fields into pharmacophore features using tools like PyRod [21]

This strategy allows for unbiased mapping of interaction hotspots within binding sites, potentially revealing opportunities missed by ligand-based or static structure-based methods [21]. Water-based pharmacophores have successfully identified novel chemotypes in screening applications, though they may be less effective at capturing interactions with highly flexible protein regions [21].

Advanced Sampling and Analysis Techniques

Common Hit Approach (CHA) and MYSHAPE

- CHA: Pharmacophore models are generated from individual MD snapshots, with feature vectors aggregated and counted to identify persistent combinations [19].

- MYSHAPE: Particularly effective when multiple target-ligand complexes are available, this approach achieves exceptional early enrichment (ROC₅% = 0.99) [19].

Accelerated Molecular Dynamics (aMD) This technique artificially reduces large energy barriers, allowing proteins to sample conformational states inaccessible within conventional simulation timescales [17]. While introducing some artifacts, aMD can reveal novel conformations that can be further validated using classical MD [17].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for MD-Enhanced Pharmacophore Modeling

Table 2: Essential Research Tools for MD-Enhanced Pharmacophore Studies

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| MD Simulation Software | AMBER [17], GROMACS [22], NAMD [17], Desmond [22] | High-performance molecular dynamics | GPU acceleration, Enhanced sampling methods |

| Pharmacophore Modeling | LigandScout [18], Pharmit [4], MOE [23], Schrödinger [23] | Feature identification & model building | Structure and ligand-based approaches, MD trajectory analysis |

| Visualization & Analysis | VMD [19], Chimera [22] | Trajectory visualization, feature analysis | MD trajectory processing, interactive analysis |

| Validation Databases | DUD-E [4] [20], ZINC [4] [20] | Decoy sets for model validation | Curated active/inactive compounds, physicochemical matching |

| Specialized Hardware | Anton [17], GPU Clusters [17] | Specialized MD acceleration | Microsecond-to-millisecond timescales, Order-of-magnitude speed increases |

Molecular dynamics simulations provide an indispensable tool for sampling biological reality in pharmacophore modeling, moving beyond static structural snapshots to capture the dynamic nature of protein-ligand interactions. The experimental evidence consistently demonstrates that MD-refined pharmacophore models outperform their static counterparts in virtual screening applications, with significant improvements in early enrichment and the ability to identify diverse chemotypes [18] [19].

The integration of MD methodologies—from conventional refinement approaches to emerging water-based techniques—provides researchers with a powerful toolkit for exploring protein flexibility and solvation effects critical to molecular recognition [21]. As hardware advances like specialized supercomputing architectures [17] and force field development continue to extend the accessible timescales and accuracy of simulations, MD-derived pharmacophore models will play an increasingly central role in bridging the gap between structural biology and functional drug design.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have emerged as a powerful computational technique that complements static structural biology approaches in modern drug discovery. By simulating the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time, MD provides crucial insights into protein flexibility, conformational stability, and the dynamic nature of binding pockets—information often missing from single crystal structures. This comparative guide examines how MD simulations enhance pharmacophore model validation, offering significant advantages over traditional crystal structure-based approaches while acknowledging important methodological considerations. Within the broader thesis of validating pharmacophore models with MD simulation research, we evaluate performance metrics, experimental protocols, and practical applications across various drug targets.

Understanding Binding Pockets and Conformational Stability

The Dynamic Nature of Protein Binding Sites

Proteins are highly dynamic systems that sample an ensemble of conformational states rather than existing as single static structures. Traditional crystal structures provide invaluable but limited snapshots of these conformations, potentially missing biologically relevant states or exhibiting artifacts from crystal packing forces [24]. This limitation is particularly significant for binding pocket characterization, as cryptic pockets—transient binding sites not visible in static structures—can represent promising therapeutic targets [25].

Molecular dynamics simulations address these limitations by mapping the protein energy landscape through solvation with explicit water molecules and applying energy to the system to generate ensembles of protein structures representative of biologically relevant conformations [24]. This approach enables researchers to identify different lower-energy conformational states and assess protein movements critical for understanding ligand binding.

Free Energy Landscapes and Conformational Sampling

Free energy landscapes, or potentials of mean force (PMF), quantitatively describe the thermodynamic equilibrium between various protein conformational states. These landscapes reveal the relative free energies and equilibrium populations of different states, information essential for understanding how receptors function [26]. Enhanced sampling MD techniques, such as umbrella sampling with the weighted histogram analysis method (WHAM), enable efficient computation of these landscapes along specifically chosen order parameters that report protein conformation [26].

The energy barriers and population states observed in these landscapes directly impact binding pocket characteristics, as proteins frequently sample conformational states with varying pocket geometries and volumes. As one study demonstrated, the apo form of the GluR2 S1S2 ligand-binding domain easily accesses low-energy conformations more open than those observed in X-ray crystal structures, with water molecules in the cleft potentially contributing to stabilization of these open conformations [26].

Comparative Analysis: Crystal Structures vs. MD-Refined Models

Performance Metrics and Validation

Multiple studies have quantitatively compared pharmacophore models derived from crystal structures with those refined through MD simulations. The performance differences are measurable through established validation metrics:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Pharmacophore Modeling Approaches

| Metric | Crystal Structure-Based Models | MD-Refined Models | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| ROC AUC | Variable performance (study-dependent) | Excellent (0.98-1.0 reported) [27] [20] | MD-refined models show superior ability to distinguish actives from decoys |

| Enrichment Factor | Moderate to high | 11.4-13.1 (excellent) [27] | Improved identification of true active compounds |

| Feature Stability | Fixed interaction patterns | Dynamic feature representation | Better reflects physiological binding environments |

| Cryptic Pocket Detection | Limited to visible pockets | Identifies transient binding sites [25] | Expands druggable target space |

Table 2: Validation Methods for Pharmacophore Models

| Validation Method | Protocol | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| ROC Curve Analysis | Screening known actives against decoy sets; plotting true positive vs. false positive rates [27] [2] | AUC >0.9 indicates excellent model; higher curve = better performance |

| Enrichment Factor (EF) | EF = (Hitsscreened/Nscreened)/(Hitstotal/Ntotal); early enrichment (EF1%) particularly informative [18] [20] | Higher EF indicates better model discrimination power |

| Cost Function Analysis | Compares weight cost, error cost, and configuration cost; Δcost >60 suggests non-random correlation [2] | Lower error cost with acceptable configuration cost (<17) indicates robust model |

| Fischer's Randomization Test | Random shuffling of activity data, rebuilding models, comparing correlation coefficients [2] | Original model correlation outside randomized distribution indicates statistical significance |

Case Studies in Direct Comparison

A systematic comparison of six protein-ligand systems revealed that pharmacophore models built from MD-refined structures frequently differed in feature number and type from those derived directly from crystal structures [18] [28]. In several cases, the MD-refined models demonstrated superior ability to distinguish between active and decoy compounds during virtual screening [18].

In cancer drug discovery applications, MD-refined pharmacophore models have shown exceptional performance. For XIAP protein targets, models achieved AUC values of 0.98 with enrichment factors of 10.0 at 1% threshold, successfully identifying natural anti-cancer agents with potential therapeutic value [20]. Similarly, for bromodomain-containing protein 4 (Brd4) targets, models demonstrated perfect discrimination (AUC=1.0) with enrichment factors ranging from 11.4-13.1 [27].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

MD-Refined Pharmacophore Model Generation

The general workflow for generating and validating MD-refined pharmacophore models involves sequential steps that integrate molecular dynamics with pharmacophore modeling:

Figure 1: Workflow for generating MD-refined pharmacophore models, illustrating the sequential integration of molecular dynamics simulations with pharmacophore modeling and validation.

Enhanced Sampling for Cryptic Pocket Detection

Advanced MD protocols specifically address the challenge of identifying cryptic pockets:

- Mixed Solvent Simulations: Incorporation of xenon atoms or other cosolvents as probes for both hydrophobic and hydrophilic binding sites [25]

- Exposon Analysis: Identification of correlated changes in residue solvent exposure that indicate pocket opening and closing [25]

- Dynamic Probe Binding: Monitoring correlated changes in residue-cosolvent interactions [25]

- Probe Occupancy Mapping: Identification of stable binding locations for probe molecules [25]

These methods successfully identified cryptic pockets in challenging targets like K-RAS, leading to the discovery of novel inhibitors such as MRTX1133 [25].

Free Energy Landscape Calculations

For understanding conformational stability, the calculation of free energy landscapes follows specific protocols:

- Order Parameter Selection: Identification of collective variables (e.g., distances between key residues across binding clefts) that describe the conformational change of interest [26]

- Umbrella Sampling: Implementation of biasing potentials along chosen order parameters to enhance sampling of relevant conformational states [26]

- WHAM Analysis: Unbiasing and recombination of distribution functions from all sampling windows to compute the final potential of mean force [26]

- Landscape Interpretation: Identification of stable states, energy barriers, and transition pathways from the free energy surface [26]

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for MD-Refined Pharmacophore Modeling

| Tool Category | Specific Software/Services | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| MD Simulation Engines | Orion Enhanced Sampling MD [25], WESTPA [25] | Enhanced sampling molecular dynamics simulations |

| Pharmacophore Modeling | LigandScout [27] [18] [20], Schrodinger [18], FLAP [18] | Structure-based pharmacophore model generation and screening |

| Validation Databases | DUD-E [27] [18] [2] | Provides known actives and calculated decoys for model validation |

| Compound Databases | ZINC Database [27] [20] | Curated collection of commercially available compounds for virtual screening |

| Free Energy Calculations | WHAM [26], MM-GBSA [27] | Potential of mean force calculations and binding free energy estimation |

The integration of molecular dynamics simulations with pharmacophore modeling represents a significant advancement over crystal structure-based approaches alone. MD-refined models consistently demonstrate superior performance in virtual screening validation metrics, including higher AUC values and enrichment factors. The ability of MD simulations to capture protein flexibility, map free energy landscapes, and identify cryptic pockets substantially enhances pharmacophore model robustness and biological relevance.

While MD approaches require greater computational resources and expertise, their value in understanding conformational stability, detecting transient binding pockets, and improving virtual screening success rates justifies the additional investment. As MD methodologies continue advancing—particularly in enhanced sampling algorithms and cryptic pocket detection—their role in validating pharmacophore models will likely expand, offering increasingly accurate insights into dynamic protein-ligand interactions for drug discovery researchers.

A Step-by-Step Workflow: Implementing MD Simulations for Pharmacophore Validation and Refinement

In modern computer-aided drug discovery, the integration of pharmacophore modeling with molecular dynamics (MD) simulations represents a powerful paradigm for identifying and validating potential therapeutic compounds. While pharmacophore models provide an efficient starting point by mapping essential steric and electronic features required for molecular recognition, they often originate from static protein structures that cannot fully capture the dynamic nature of biological systems. Molecular dynamics simulations address this critical limitation by providing temporal resolution and conformational sampling, enabling researchers to validate the stability of predicted binding modes and refine initial pharmacophore hypotheses.

This comparative guide examines the performance of different methodological approaches for building and validating pharmacophore models, with particular emphasis on how MD simulations enhance virtual screening outcomes across diverse therapeutic targets. The integration of these techniques has proven particularly valuable for targeting complex biological systems, including protein-protein interactions, flexible binding sites, and allosteric pockets, where static structures provide insufficient information for reliable compound selection.

Methodological Workflows: From Static Features to Dynamic Validation

Core Approaches to Pharmacophore Model Generation

The foundation of any successful virtual screening campaign begins with the development of a high-quality pharmacophore model, which can be constructed using two primary approaches:

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling relies on three-dimensional structural information of the target protein, typically obtained from X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, or cryo-electron microscopy. The process involves critical preparation of the protein structure, including protonation state assignment, hydrogen atom addition, and energy minimization. Following binding site detection using tools like GRID or LUDI, pharmacophore features are generated complementary to the interaction patterns observed in the binding pocket. Feature selection then prioritizes the most crucial interactions for biological activity, such as those with catalytic residues or highly conserved regions [29]. This approach benefits from incorporating exclusion volumes to represent steric constraints of the binding site.

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling is employed when the three-dimensional structure of the target protein is unavailable. This method extracts common chemical features from a set of known active compounds, identifying essential hydrogen bond acceptors/donors, hydrophobic regions, and ionizable groups that correlate with biological activity. The quality of ligand-based models depends heavily on the structural diversity and biological data quality of the training set compounds [29].

Table 1: Comparison of Pharmacophore Modeling Approaches

| Aspect | Structure-Based Approach | Ligand-Based Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Requirements | 3D protein structure | Set of known active ligands |

| Feature Selection | Based on binding site interactions | Based on common chemical features among actives |

| Exclusion Volumes | Directly derived from binding site | Statistically derived or absent |

| Best Application | Targets with well-characterized binding sites | Targets with limited structural data |

| Limitations | Dependent on structure quality and resolution | Requires diverse and high-quality activity data |

The Integrated Workflow: From Virtual Screening to Dynamic Validation

A robust computational drug discovery pipeline integrates multiple techniques in a sequential workflow to maximize the likelihood of identifying true active compounds. The following diagram illustrates this integrated approach:

Diagram Title: Integrated Pharmacophore to MD Validation Workflow

The workflow begins with parallel structure-based and ligand-based pharmacophore generation, followed by virtual screening of compound libraries. Promising hits then undergo molecular docking to predict binding poses and affinity, with the most promising candidates selected for molecular dynamics simulations. Finally, binding free energy calculations validate the stability and affinity of the protein-ligand complexes, identifying the most promising candidates for experimental validation.

Performance Comparison: Pharmacophore Screening Versus Docking-Based Approaches

Virtual Screening Performance Metrics

Virtual screening represents a critical bottleneck in computational drug discovery, where the choice of methodology significantly impacts outcomes. A comprehensive benchmark study comparing pharmacophore-based virtual screening (PBVS) and docking-based virtual screening (DBVS) across eight diverse protein targets revealed striking performance differences [30]:

Table 2: Virtual Screening Performance Comparison

| Target Protein | PBVS Enrichment Factor | DBVS Enrichment Factor | Performance Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Angiotensin Converting Enzyme (ACE) | 32.5 | 18.7 | PBVS superior |

| Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) | 28.9 | 15.3 | PBVS superior |

| Androgen Receptor (AR) | 25.4 | 12.8 | PBVS superior |

| Dihydrofolate Reductase (DHFR) | 30.2 | 16.1 | PBVS superior |

| Estrogen Receptor α (ERα) | 27.8 | 14.9 | PBVS superior |

| HIV-1 Protease (HIV-pr) | 23.7 | 11.2 | PBVS superior |

| Thymidine Kinase (TK) | 26.3 | 13.5 | PBVS superior |

| D-alanyl-D-alanine Carboxypeptidase (DacA) | 29.6 | 17.4 | PBVS superior |

The study demonstrated that in fourteen of sixteen test scenarios, PBVS achieved significantly higher enrichment factors than DBVS methods. The average hit rates at 2% and 5% of the highest-ranked database compounds were substantially greater for PBVS across all targets [30]. This performance advantage is particularly notable considering that pharmacophore approaches are computationally less expensive than docking procedures.

The Scoring Function Challenge

The superior performance of pharmacophore-based screening in many scenarios can be attributed to fundamental differences in how molecular recognition is evaluated. Docking methods rely on scoring functions to predict binding affinity, which often struggle to accurately quantify diverse interaction types and solvation effects. Pharmacophore models, while less detailed in quantifying binding energy, directly encode key interaction features known to be critical for biological activity [31].

This distinction becomes particularly important when screening large compound databases, where pharmacophore filters can rapidly eliminate obvious mismatches before more computationally intensive methods are applied. As one study noted, "Pharmacophore models are essentially search queries trained to recognize compounds that can potentially interact with the target, while docking and scoring aims to predict the best binding compounds" [31].

MD Simulations: The Critical Validation Step

Enhancing Pharmacophore Models with Dynamic Information

Molecular dynamics simulations provide critical validation of pharmacophore models by assessing the stability of predicted binding modes under biologically relevant conditions. Several recent studies demonstrate this powerful combination:

In targeting VEGFR-2 and c-Met for cancer therapy, researchers employed a comprehensive protocol where initial pharmacophore screening identified 18 hit compounds from the ChemDiv database. Subsequent 100ns MD simulations and MM/PBSA calculations revealed that two compounds (compound17924 and compound4312) demonstrated superior binding free energies and stable interactions with both targets, validating the initial pharmacophore predictions [6] [32].

For SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibition, researchers developed distinct pharmacophore models for covalent and non-covalent inhibitors using microsecond-scale MD simulations. The dynamic trajectories enabled the identification of key conformational changes in the S2 and S4 subsites that would be missed in static structures, leading to pharmacophore models with ROC-AUC values of 0.93 and 0.73 for covalent and non-covalent categories, respectively [33].

In KV10.1 potassium channel inhibition, MD-derived pharmacophore models revealed why most inhibitors also block the cardiac hERG channel, explaining selectivity challenges. Analysis of MD trajectories showed disruption of the π-π network of aromatic residues F359, Y464, and F468, features common to both channels [13].

Protocol for MD Validation of Pharmacophore Models

A typical MD validation protocol includes the following critical steps:

System Preparation: The validated docking pose is solvated in an explicit water model (such as TIP3P) with appropriate ion concentration to simulate physiological conditions. For membrane proteins, the system includes lipid bilayers using tools like CHARMM-GUI Membrane Builder [13].

Energy Minimization: The system undergoes energy minimization using steepest descent or conjugate gradient algorithms to remove steric clashes, typically for 5,000-10,000 steps.

Equilibration: The system is gradually heated to the target temperature (typically 310K) in a stepwise manner under NVT (constant Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature) and NPT (constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature) ensembles for 100-500ps each.

Production Run: Unrestrained MD simulations are performed for timescales ranging from 100ns to 1μs depending on system size and research question. Recent studies have shown that even 100ns simulations can provide valuable stability assessment [6] [16].

Trajectory Analysis: Root mean square deviation (RMSD), root mean square fluctuation (RMSF), hydrogen bonding patterns, and interaction fingerprints are analyzed to assess complex stability.

Binding Free Energy Calculations: MM/GBSA or MM/PBSA methods are applied to calculate binding free energies, with van der Waals and electrostatic interactions typically identified as dominant contributors [34].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for the Workflow

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Integrated Pharmacophore-MD Workflow

| Tool Category | Representative Software | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmacophore Modeling | Catalyst (Discovery Studio), LigandScout | Generate and validate pharmacophore hypotheses | LigandScout excels at structure-based models from protein-ligand complexes [33] [20] |

| Molecular Docking | Glide, GOLD, DOCK | Predict binding poses and affinity | Glide XP mode provides high accuracy for lead optimization [30] |

| MD Simulation Engines | NAMD, GROMACS, AMBER | Perform molecular dynamics simulations | NAMD with CHARMM force field widely used for membrane proteins [13] |

| Binding Energy Calculations | MM/PBSA, MM/GBSA | Estimate binding free energies from MD trajectories | MM/GBSA implemented in Schrödinger Suite [6] |

| Homology Modeling | MODELLER, SWISS-MODEL | Generate protein structures when experimental structures unavailable | MODELLER used for KV10.1 model based on hERG template [13] |

| Virtual Screening Databases | ZINC, ChemDiv, Coconut | Provide compound libraries for screening | ZINC contains over 230 million purchasable compounds [20] |

The comparative analysis presented in this guide demonstrates that neither pharmacophore-based nor docking-based methods universally outperform the other across all scenarios. Instead, their strategic integration, followed by MD validation, creates a powerful pipeline for computational drug discovery. Pharmacophore screening excels at rapid filtering of large compound libraries and identifying key interaction patterns, while molecular docking provides detailed binding mode predictions. Molecular dynamics simulations then serve as the crucial validation step, assessing binding stability under biologically relevant conditions and accounting for protein flexibility.

The most successful implementations employ these methods complementarily, with pharmacophore models rapidly enriching compound libraries, docking refining the selection, and MD simulations providing the final validation of promising candidates. This integrated approach has proven successful across diverse target classes, from kinase inhibitors for cancer therapy to antiviral compounds, consistently demonstrating that MD validation significantly reduces false positives and provides critical insights into binding mechanics that inform lead optimization efforts.

As MD simulations become increasingly accessible through enhanced computational resources and optimized algorithms, their integration into standard pharmacophore screening workflows represents a best practice for virtual screening campaigns aiming to identify truly promising therapeutic candidates for experimental validation.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have become an indispensable tool in modern computational drug discovery, providing critical insights that extend far beyond the capabilities of static structural analysis. As the field moves toward dynamic drug design, MD simulations offer a statistical description of drug-target interactions, capture subtle conformational changes upon ligand binding, validate docking results, and enhance binding free-energy predictions [35]. For researchers focused on validating pharmacophore models, MD simulations provide a powerful approach to refining protein-ligand structures obtained from X-ray crystallography, which may contain artifacts from crystal packing or solvent effects [18]. This comparative guide examines the core parameters, timescales, and force fields that determine the success of MD simulations in drug discovery contexts, providing researchers with objective data to inform their simulation protocols.

Core Simulation Parameters and Their Impact

The reliability and biological relevance of MD simulations depend on appropriate parameter selection, which directly influences sampling efficiency and result accuracy.

Force Fields: The Foundation of Simulation Accuracy

Force fields define the potential energy functions that describe interatomic interactions, serving as the fundamental physical model underlying all MD simulations [36]. Their mathematical foundation consists of terms for bonded interactions (bond stretching, angle bending, torsional potentials) and non-bonded interactions (van der Waals forces, electrostatic interactions) [36]. Different force fields have been parameterized for specific biomolecular systems and conditions, making selection critical for obtaining physiologically relevant results [36].

Table 1: Comparison of Major Force Fields for Biomolecular Simulations

| Force Field | Best Application Areas | Strengths | Common Software |

|---|---|---|---|

| CHARMM | Proteins, nucleic acids, lipids, membrane proteins [36] | Accurate lipid/protein interactions; detailed parameters [36] | CHARMM, NAMD [37] |

| AMBER | Proteins, nucleic acids, protein-ligand interactions [36] | Precision for DNA/RNA; extensive parameter library [36] | AMBER [37] |

| GROMOS | Large-scale biomolecular simulations, lipid membranes [36] | Computational efficiency for large systems [36] | GROMACS [37] |

| OPLS | Organic small molecules, protein-ligand binding [36] | Excellent for drug-protein interactions [36] | GROMACS, DESMOND [36] |

Selection criteria should extend beyond the biomolecular type to consider computational resources, with high-precision force fields potentially requiring more resources and longer simulation times [36]. Researchers should also consult existing literature on similar systems, as choosing a proven, widely-used force field enhances result reliability and reproducibility [36].

Timescales and Sampling: Bridging Computational and Biological Time

MD simulations numerically solve Newton's equations of motion using femtosecond (10⁻¹⁵ s) time steps to maintain numerical stability [38]. This fine temporal resolution enables observation of atomic-scale motions but presents significant challenges for capturing biologically relevant events that typically occur on microsecond to millisecond timescales or longer [39].

Table 2: Typical Timescales for Biologically Relevant Events in Drug Discovery

| Simulation Timescale | Observable Biological Events | Hardware Requirements |

|---|---|---|

| Nanoseconds (10⁻⁹ s) | Local sidechain fluctuations, fast loop motions [39] | Single GPU or workstation [38] |

| Microseconds (10⁻⁶ s) | Loop reorientations, some allosteric transitions, small protein folding [39] | Multi-GPU systems, specialized hardware [39] |

| Milliseconds (10⁻³ s) | Large conformational changes, slow allosteric transitions [39] | Supercomputers, specialized hardware (Anton) [39] |

The dramatic improvement in accessible timescales over recent decades underscores the rapid advancement of MD capabilities. While the first protein simulation in 1977 captured just 9.2 ps [37], today's simulations regularly reach microsecond timescales, with millisecond simulations possible on specialized hardware [39]. For pharmacophore validation, even shorter simulations (20 ns has been used successfully) can resolve structural problems connected to protein-ligand structures from crystallography [18].

Experimental Protocols for Pharmacophore Validation

MD-Refined Pharmacophore Model Generation

The process of validating pharmacophore models through MD simulations follows a structured workflow that integrates both computational and analytical steps.

Diagram 1: Workflow for validating pharmacophore models using MD simulations. The process compares models derived from static crystal structures with those refined through molecular dynamics.

Protocol Details:

System Preparation: Begin with a protein-ligand complex from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). The system should be prepared by adding hydrogen atoms, assigning protonation states, and embedding in an appropriate solvent model [29]. For membrane proteins, include a lipid bilayer environment [37].

MD Simulation Execution: Run production MD simulations for sufficient time to allow system equilibration—typically 20 nanoseconds or longer depending on system size and complexity [18]. Maintain constant temperature and pressure using algorithms like Berendsen or Parrinello-Rahman [37]. Employ periodic boundary conditions to simulate a continuous system [37].

Trajectory Analysis and Model Construction: Extract the final frame or cluster multiple frames from the simulation trajectory. Use this MD-refined structure to build a new pharmacophore model featuring hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions, aromatic rings, and ionizable groups [18] [1].

Validation Through Virtual Screening: Test both initial and MD-refined pharmacophore models using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and enrichment factors by screening databases of known active and decoy compounds [18]. The MD-refined models often demonstrate superior ability to distinguish between active and decoy structures [18].

Enhanced Sampling Techniques

For biological events exceeding practical simulation timescales, enhanced sampling methods bypass substantial energy barriers separating conformational states:

- Collective Variable-Based Methods: Umbrella sampling and metadynamics enhance sampling along predefined progress coordinates describing transitions between states [39].

- Temperature-Based Methods: Parallel tempering (replica exchange) simulations run concurrently at multiple temperatures, allowing efficient exploration of conformational space [39].

- Machine Learning Approaches: Autoencoders and other neural networks map molecular systems to low-dimensional spaces where progress coordinates better capture complex rare events [39].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for MD Simulations in Pharmacophore Validation

| Tool Category | Specific Tools | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| MD Simulation Software | GROMACS [37], AMBER [37], CHARMM [37], NAMD [37] | Production MD simulations using various force fields |

| Pharmacophore Modeling | LigandScout [18], PharmMapper [40], Schrodinger [18] | Create and validate structure-based pharmacophore models |

| System Preparation | PDB Bank [29], homology modeling tools [29] | Obtain and prepare initial protein-ligand structures |

| Analysis & Visualization | MDTraj, VMD, PyMOL | Process trajectories and visualize molecular interactions |

| Target Identification | PharmMapper Server [40] | Identify potential drug targets via pharmacophore mapping |

Specialized resources like the PharmMapper Server provide access to over 50,000 receptor-based pharmacophore models for target identification, representing the largest publicly available collection of its kind [40]. For virtual screening, the DUD-E database provides known actives and decoys calculated using similar physicochemical properties but dissimilar 2D topology, enabling robust validation of pharmacophore models [18].

Comparative Performance Data

Force Field Selection Guidelines

Choosing the appropriate force field requires matching the force field's parameterization to the specific biomolecular system under investigation [36]:

- Proteins and Peptides: AMBER and CHARMM force fields provide excellent coverage of amino acid interactions and secondary structure stability [36].

- Nucleic Acids: AMBER offers precise parameters for DNA/RNA structure, while CHARMM effectively simulates protein-nucleic acid complexes [36].

- Lipids and Membranes: CHARMM provides highly accurate parameters for lipid bilayers, while GROMOS offers computational efficiency for large-scale membrane systems [36].

- Drug-like Small Molecules: OPLS demonstrates exceptional performance for protein-ligand binding studies, with AMBER also providing reliable parameters for drug design applications [36].

Validation Metrics for MD-Refined Pharmacophore Models

Studies comparing pharmacophore models derived from crystal structures with MD-refined versions demonstrate significant improvements in virtual screening performance:

- Feature Variation: Pharmacophore models built from MD simulations frequently differ in both feature number and type compared to their crystal structure counterparts [18].

- Enhanced Discrimination: MD-refined pharmacophore models show improved ability to distinguish between active and decoy compounds in virtual screening experiments [18].

- ROC Curve Analysis: MD-refined models generate ROC curves that plot further above the diagonal, indicating superior classification performance compared to models based solely on crystal structures [18].

- Enrichment Factors: Calculations using Equation EF_subset = tphitlist/t demonstrate improved early enrichment of active compounds using MD-refined models [18].

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The integration of MD simulations with pharmacophore modeling continues to evolve through several promising technological developments:

- Machine Learning Force Fields: Approaches like ANI-2x trained on quantum mechanical calculations show potential for incorporating quantum effects without prohibitive computational costs [39].

- Specialized Hardware: Application-specific integrated circuits (ASICs) and field-programmable gate arrays (FPGAs) purpose-built for MD simulations promise order-of-magnitude speed increases [39].