Beyond Static Models: Mastering Conformational Sampling for Advanced Pharmacophore Modeling in Drug Discovery

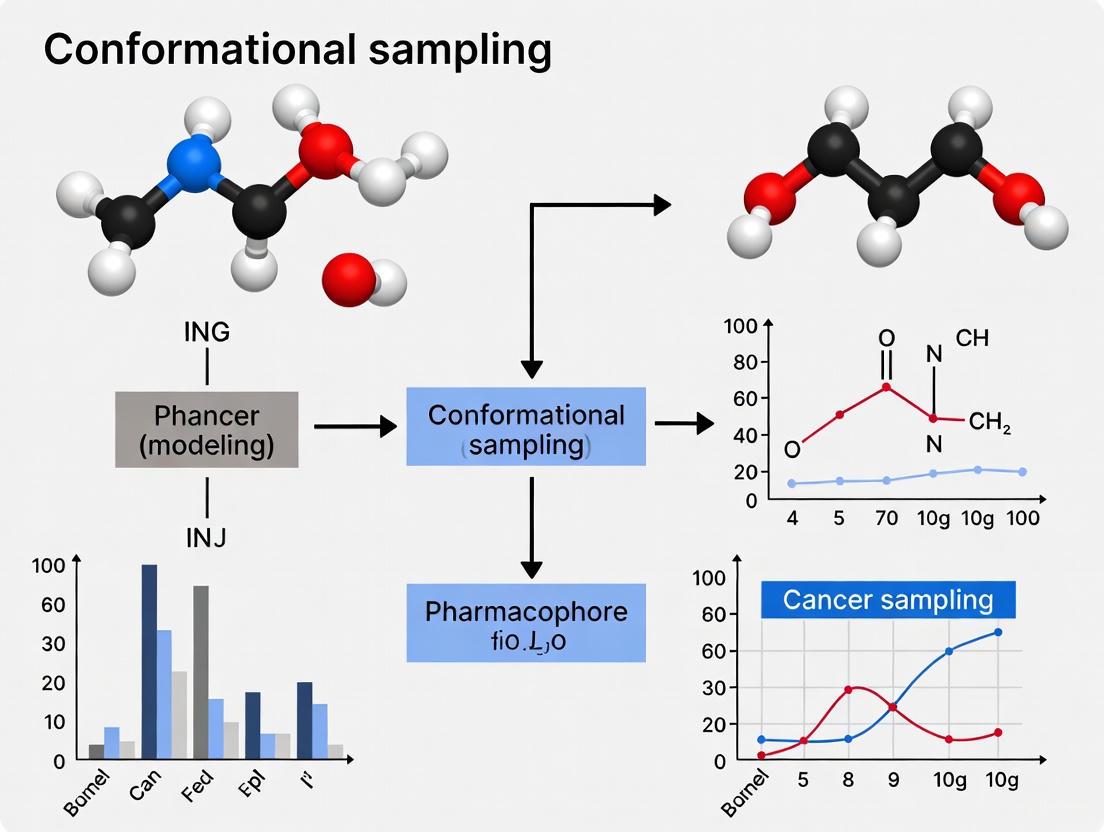

This article addresses the critical challenge of conformational sampling in pharmacophore modeling, a cornerstone of modern computer-aided drug discovery.

Beyond Static Models: Mastering Conformational Sampling for Advanced Pharmacophore Modeling in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article addresses the critical challenge of conformational sampling in pharmacophore modeling, a cornerstone of modern computer-aided drug discovery. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the fundamental importance of capturing molecular flexibility for accurate bioactivity prediction. The content delves into traditional and cutting-edge AI-driven methodological approaches, provides strategies for troubleshooting common pitfalls, and outlines rigorous validation frameworks. By synthesizing foundational knowledge with the latest advancements in dynamic and quantitative modeling, this guide serves as a comprehensive resource for developing more robust and predictive pharmacophore models to accelerate lead identification and optimization.

The Conformational Landscape: Why Flexibility is Fundamental to Pharmacophore Models

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ: Why does my pharmacophore model fail to identify known active compounds during virtual screening?

This is a common issue often rooted in the incomplete or inaccurate sampling of the ligand's bioactive conformation.

Potential Cause 1: Inadequate Conformational Sampling

- Problem: The conformer generation tool did not produce an ensemble that includes a geometry close to the bioactive conformation. A single 3D geometry may miss a pharmacophore, leading to false negative hits [1].

- Solution: Increase the thoroughness of your conformational search. Most pharmacophore methods employ sets of molecular conformations (conformational ensembles) to ensure the bioactive conformation is represented. However, balance is key, as generating too many conformations can increase computation times and false positives [1]. Consider using a multi-method approach (systematic, stochastic, knowledge-based) for better coverage.

Potential Cause 2: Overly Restrictive Model

- Problem: The pharmacophore model is too specific, potentially due to tight spatial tolerances or features derived from a single, rigid ligand. This can miss active compounds that bind in a slightly different manner [2].

- Solution: Re-evaluate the spatial constraints and feature definitions in your model. Slightly increase distance and angle tolerances based on the flexibility observed in molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of known actives [3]. Validate the model's ability to recognize a diverse set of known active compounds.

Potential Cause 3: Neglect of Protein Flexibility and Induced Fit

- Problem: The pharmacophore model is based on a single, static protein structure. Proteins are dynamic, and ligand binding can induce conformational changes (induced fit), meaning the binding site for your compound may differ from the one in your model [2].

- Solution: If possible, develop pharmacophore models using multiple protein structures (e.g., from different crystal structures or MD snapshots). For structure-based models, consider incorporating protein-derived exclusion volumes cautiously, as they can be overly restrictive if the protein's flexibility is not accounted for [2] [4].

FAQ: How can I determine if my generated conformer ensemble adequately represents the bioactive conformation?

Validating your conformational ensemble is critical before proceeding with pharmacophore modeling.

Diagnostic Step 1: RMSD Analysis

- Protocol: If the crystal structure of a ligand-bound target is available, calculate the Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD) between the generated conformers and the experimentally determined bioactive conformation. A low RMSD (often <1.0-1.5 Å) for at least one conformer indicates good coverage.

- Tools: Most molecular modeling software packages (e.g., Discovery Studio, MOE, Schrödinger) have built-in RMSD calculation tools.

Diagnostic Step 2: Pharmacophore Feature Overlay

- Protocol: Visually inspect the overlay of your generated conformers onto the pharmacophore model derived from the bioactive conformation. Check if a significant subset of conformers can satisfy all the essential steric and electronic features of the model [2].

- Tools: Software like LigandScout or Discovery Studio provides visualization for this purpose.

Diagnostic Step 3: Cross-docking Validation (for structure-based models)

- Protocol: Use multiple conformers from your ensemble as input for molecular docking into the protein's binding site. An ensemble that produces docking poses consistently close to the experimental bioactive pose is considered a high-quality ensemble [1].

FAQ: What is the most reliable method for generating conformers for pharmacophore modeling?

No single method is universally "most reliable," but best practices involve understanding the strengths of different algorithms. The table below summarizes key software technologies.

Table 1: Comparison of Conformer Generation Methods

| Software/Method | Algorithm Type | Key Characteristics | Best Use-Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| CatConf/ConFirm (Discovery Studio) [1] | Modified Systematic Search | Provides "fast" and "best" search modes; uses a fuzzy grid for atom clashes. | General-purpose, balanced between speed and coverage. |

| OMEGA [1] | Rule-based, Knowledge-guided | Builds conformers using a fragment library and torsion rules; biased toward experimental geometries. | High-throughput screening for large compound databases. |

| Random Incremental Pulse Search (RIPS) [1] | Stochastic Search | Randomly perturbs torsion angles; efficient for highly flexible molecules. | Exploring conformational space of large, flexible macrocycles. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) with Explicit Solvent [3] | Simulation-based | Samples conformations in a physically realistic environment, accounting for solvation effects. | Detailed study of a specific compound's behavior in solution; characterizing the unbound state. |

Recommended Workflow:

- For high-throughput virtual screening, use a fast, knowledge-based tool like OMEGA.

- For lead optimization or studying particularly flexible molecules, use a more thorough stochastic or systematic method.

- For fundamental studies on the unbound state and reorganization energy, use MD simulations in explicit solvent, as they avoid the "conformational collapse" seen with in vacuo or implicit solvation models (GB) [3].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Detailed Protocol: Assessing the Intramolecular Reorganization Energy via MD Simulations

This protocol, based on the work of Foloppe et al. [3], provides a methodology for estimating the enthalpic cost a compound pays to adopt its bioactive conformation.

Objective: To estimate the enthalpic intramolecular reorganization energy (ΔHReorg) of a ligand upon binding to its biological target.

Principle: The reorganization energy is the difference in the ligand's intramolecular energy between its bound state (from a crystal structure) and its representative unbound state (sampled in solution).

Materials & Software:

- Ligand-Protein Complex: A high-resolution (e.g., X-ray) structure from the PDB.

- MD Simulation Software: Such as GROMACS, AMBER, or NAMD.

- Force Field: A suitable empirical force field (e.g., CHARMM, AMBER, OPLS).

- Solvation Model: Explicit water solvent (e.g., TIP3P water model).

Procedure:

- System Setup:

- Prepare the ligand-protein complex from the PDB file, adding missing hydrogen atoms and assigning appropriate protonation states.

- Solvate the complex in a box of explicit water molecules and add ions to neutralize the system's charge.

Simulation of the Bound State:

- Energy minimize the entire system to remove steric clashes.

- Perform an equilibration protocol, first restraining the heavy atoms of the protein and ligand, then releasing the restraints.

- Run a production MD simulation (≥50 ns is recommended for stability). From this trajectory, extract multiple snapshots of the ligand's conformation in the bound state.

Simulation of the Unbound State:

- Isolate the ligand from the crystal structure.

- Solvate the ligand alone in a box of explicit water molecules.

- Energy minimize and equilibrate the system.

- Run a long production MD simulation (≥0.5 μs is recommended for adequate sampling [3]). This trajectory represents the conformational space of the ligand free in solution.

Energy Calculation and Analysis:

- For each snapshot of the ligand from the bound state simulation, calculate its intramolecular energy (Eintra_bound) using the chosen force field. This includes bond, angle, torsion, and van der Waals/electrostatic internal terms.

- For snapshots from the unbound state simulation, calculate the intramolecular energy (Eintra_unbound).

- Calculate the average intramolecular energy for both the bound (

) and unbound ( ) states. - Compute the enthalpic reorganization energy as: ΔHReorg =

- .

Interpretation: A large positive ΔHReorg indicates the ligand must pay a significant enthalpic penalty to adopt its bound conformation, which can inform the optimization of ligand pre-organization [3].

Workflow: Integrated Pharmacophore Model Development and Validation

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for developing and validating a robust pharmacophore model, incorporating steps to address conformational sampling challenges.

Diagram Title: Pharmacophore Modeling and Validation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Conformational Analysis and Pharmacophore Modeling

| Tool Category | Specific Software / Resource | Function in Research | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Commercial Modeling Suites | Discovery Studio (Accelrys/BIOVIA), MOE (Chemical Computing Group), Schrödinger Suite | Integrated environments for conformer generation, pharmacophore model development (both ligand- and structure-based), and virtual screening. | User-friendly GUI; comprehensive functionalities; requires license. |

| Open-Source Tools | Pharmer, PharmaGist, ZINCPharmer, RDKit | Perform essential pharmacophore tasks like ligand alignment, feature identification, and model generation. | Cost-effective; may require command-line skills; highly customizable [2]. |

| Conformer Generators | OMEGA (OpenEye), CONFIRM (Discovery Studio), RDKit Conformer Generation | Automatically generate multiple, diverse 3D conformations of a molecule for analysis and screening [1]. | Balance between speed and coverage is critical; method (rule-based vs. stochastic) impacts results. |

| Molecular Dynamics Engines | GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD | Simulate the physical movement of atoms over time to study ligand conformational dynamics in explicit solvent and estimate reorganization energy [3]. | Computationally intensive; provides physically realistic sampling but requires expertise. |

| Structural Databases | RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB), Cambridge Structural Database (CSB) | Source of experimental 3D structures of proteins and small molecules for structure-based modeling and validation [4]. | Critical for structure-based approaches; data quality must be assessed (resolution, completeness). |

The Critical Role of Conformational Ensembles in Avoiding False Negatives

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why is a single protein structure insufficient for creating a reliable pharmacophore model? Proteins are flexible molecules that exist as an ensemble of conformations. A pharmacophore model derived from a single, static crystal structure may only capture one snapshot of the possible interaction patterns. This static model can miss critical, transient interaction features that are present in other biologically relevant conformations, leading to false negatives during virtual screening by failing to identify ligands that bind to these alternative states [5].

2. What is the main consequence of using an inadequate conformational ensemble for my database ligands? If the conformational sampling of your database ligands is too narrow and fails to generate the bioactive conformation, your screening will produce false negatives. This means you will miss active compounds because their 3D representation in the database cannot map to the features of your pharmacophore model. The success of a 3D pharmacophore search experiment heavily relies on the conformational diversity of the 3D structures stored in the database [1].

3. How can Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations improve my pharmacophore models? MD simulations naturally account for protein flexibility and solvation effects by sampling multiple conformations of the protein-ligand complex over time. You can generate a unique pharmacophore model from each snapshot of the simulation [6] [5]. Using an ensemble of these models for screening, or consolidating them into a single hierarchical representation, provides a more comprehensive picture of the essential interactions, reducing the risk of false negatives [7] [5].

4. What are some advanced tools for generating conformational ensembles? Several software tools are available, each with different strengths. MOE and Catalyst (now in Discovery Studio) are established commercial packages with specialized conformational sampling methods [8] [1]. The SILCS-Pharm protocol uses MD simulations with a diverse set of probe molecules to map functional group requirements, explicitly including protein flexibility and desolvation effects [7]. Modern AI-based tools like DiffPhore are also emerging for precise ligand-pharmacophore mapping [9].

5. How do I know if my conformational sampling protocol is effective? A good protocol should be able to:

- Reproduce the bioactive conformation of known ligands from experimental structures [8].

- Generate a diverse yet relevant set of conformations that cover the low-energy conformational space without being overly redundant [1].

- Achieve a balance where the number of conformations is sufficient to avoid false negatives but not so large that it causes a prohibitive increase in computational time and false positives [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: High False Negative Rate in Virtual Screening

Your pharmacophore model retrieves known actives from a test set poorly.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient ligand conformational diversity [1] | Check if known active ligands' bioactive conformations are present in your generated database ensemble. | Increase the energy cutoff or the number of output conformations in your conformer generation tool (e.g., use the "best" mode in Catalyst/Discovery Studio instead of "fast") [1]. |

| Overly rigid protein model [5] | Your model is derived from a single protein crystal structure. | Generate an ensemble of protein conformations using MD simulations and create a consensus pharmacophore model or use a common hits approach (CHA) with multiple models [5]. |

| Inadequate pharmacophore feature sampling [7] | The model lacks key hydrogen bond donor/acceptor features, or they are imprecisely defined. | Use a method like SILCS-Pharm that employs explicit probe molecules (e.g., methanol, formamide) to define clear, desolvation-aware donor and acceptor features [7]. |

| Excessive exclusion volumes | The model has too many steric constraints from the protein backbone. | Review and remove non-essential exclusion volumes, or use a smoothed representation like an exclusion shell to avoid overly restricting viable ligand poses [10]. |

Problem: Inability to Reproduce Bioactive Ligand Conformation

The conformational ensemble generated for a ligand does not include its known experimentally-determined (e.g., from PDB) bound structure.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Sampling algorithm is trapped in local minima | The generated conformers are clustered in a small region of conformational space. | Switch from a deterministic method to a stochastic search algorithm or use a poling technique that promotes conformational variation during the search [1]. |

| Incorrect force field parameters | The calculated energy of the bioactive conformation is unrealistically high. | Validate your conformational sampling method on a set of protein-bound ligands to ensure it can reproduce bioactive conformations [8]. Consider using a different force field if the problem persists. |

| Limited sampling of ring systems or torsional angles | Key ring puckering or torsional rotations in the bioactive pose are missing. | Ensure your conformer generation tool includes methods for sampling ring conformations and uses a reduced torsional barrier for rotatable bonds connected to aromatic rings [1]. |

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Generating a Dynamic Pharmacophore Ensemble from MD Simulations

This protocol uses molecular dynamics (MD) trajectories to create a comprehensive set of pharmacophore models that account for protein flexibility [6] [5].

- System Preparation: Start with a high-resolution protein-ligand complex structure. Prepare the system using standard software (e.g., CHARMM-GUI, Maestro) by adding hydrogens, assigning force field parameters (e.g., GAFF for ligands), solvating, and adding ions [5].

- Molecular Dynamics Simulation: Perform MD simulations using a package like AMBER or NAMD. After equilibration, run production simulations for a sufficient time to capture relevant motions (e.g., >100 ns). Running multiple replicates with different initial velocities is recommended [5].

- Trajectory Sampling: Extract snapshots from the trajectory at regular intervals (e.g., every 100 ps).

- Pharmacophore Generation: For each snapshot, use a structure-based pharmacophore tool (e.g., LigandScout) to automatically generate a pharmacophore model based on the protein-ligand interactions present in that frame [5].

- Consensus and Analysis: Use a method like the Hierarchical Graph Representation of Pharmacophore Models (HGPM) to analyze, cluster, and visualize the relationships between all the generated models. This helps in selecting a representative subset of models for screening [5].

Protocol 2: Using SILCS for Solvation-Aware Pharmacophore Modeling

The Site Identification by Ligand Competitive Saturation (SILCS) protocol explicitly includes desolvation effects in pharmacophore feature identification [7].

- SILCS Simulation Setup: Set up an MD simulation of the target protein in an aqueous solution of small molecule probes. Key probes include:

- Benzene (for aromatic features)

- Propane (for aliphatic features)

- Methanol, formamide, acetaldehyde (for neutral hydrogen bond donor/acceptor features)

- Methylammonium (for positive charge)

- Acetate (for negative charge)

- FragMap Calculation: From the simulation, calculate 3D probability maps of the functional group-binding patterns ("FragMaps") for each probe type. Convert these maps into Grid Free Energy (GFE) representations.

- Feature Generation: Identify voxels with favorable GFE values and cluster them to define "FragMap features."

- Pharmacophore Hypothesis Creation: Classify and convert the FragMap features into standard pharmacophore features (e.g., HBD, HBA, hydrophobic, ionic). Prioritize features based on their summed grid free energy (FGFE score) to build the final pharmacophore model for virtual screening [7].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Conformational Sampling Methods

This table summarizes how different conformational sampling approaches perform against key criteria for successful pharmacophore modeling.

| Method / Tool | Key Strength | Reproduces Bioactive Conformation? | Accounts for Protein Flexibility? | Computational Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MOE (Systematic/Stochastic) [8] | Good for high-throughput 3D library generation | Yes, performs at least as well as Catalyst | No (Ligand-only) | Medium |

| Catalyst/Discovery Studio [8] [1] | Established, validated protocols for pharmacophore modeling | Yes | No (Ligand-only) | Medium |

| MD-Based Ensembles [6] [5] | Captures true dynamics & transient states | Yes, by sampling multiple states | Yes | High |

| SILCS-Pharm [7] | Explicitly includes solvation/desolvation | Implicitly via GFE FragMaps | Yes | High |

| Shape-Focused (O-LAP) [10] | Emphasizes cavity shape complementarity | Yes, via docked active ligands | Indirectly, via input poses | Low-Medium |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Ensemble-Based Modeling

A toolkit of computational methods and resources essential for advanced conformational sampling and pharmacophore modeling.

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function in Research | Key Feature / Application |

|---|---|---|

| LigandScout [11] [5] | Generates structure- and ligand-based pharmacophore models from complexes or ligand sets. | Defines feature types like HBD, HBA, hydrophobic, aromatic, ionic, and exclusion volumes. |

| CHARMM-GUI [6] [5] | Prepares complex simulation systems for MD (membrane/protein solvation, ion addition). | Streamlines setup for MD simulations used in dynamic pharmacophore modeling. |

| SILCS Probe Molecules [7] | A set of 8 small molecules (e.g., benzene, methanol, acetate) used in competitive MD simulations. | Maps functional group affinity patterns on a target, accounting for flexibility and desolvation. |

| HGPM (Hierarchical Graph) [5] | A visualization method representing multiple pharmacophore models from an MD trajectory as a single graph. | Aids in intuitive model selection and analysis of feature hierarchy and relationships. |

| O-LAP Algorithm [10] | Generates shape-focused pharmacophore models by clustering overlapping atoms from docked active ligands. | Improves docking enrichment by focusing on cavity shape and electrostatic potential matching. |

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Dynamic Pharmacophore Development Workflow

Diagram 2: Troubleshooting False Negatives

Troubleshooting Guide: Conformational Sampling in Pharmacophore Modeling

This guide addresses common challenges researchers face during the conformational sampling stage of pharmacophore modeling, a critical step for successful virtual screening and drug discovery.

1. How do I resolve the issue of my pharmacophore model failing to retrieve active compounds during virtual screening?

This problem often stems from poor conformational coverage, meaning the bioactive conformation of your query compounds is missing from the generated ensemble.

- Problem: The conformational ensemble used for database screening does not include the bioactive conformation, leading to false negatives.

- Solution: Optimize your conformer generation parameters to ensure broad coverage of the conformational space.

- Actionable Steps:

- Increase Conformational Sampling: If using a systematic search, reduce the energy threshold and increase the maximum number of conformers. For example, one study used an energy threshold of 10 kcal/mol and a maximum of 250 conformers per molecule to ensure adequate coverage [12].

- Use a Robust Algorithm: Employ a conformer generator known for its effectiveness in reproducing bioactive conformations, such as OMEGA, which is widely cited for this purpose [13].

- Validate with a Known Bioactive Compound: Generate conformers for a molecule with a known protein-bound structure (from the PDB). Check if the generator can produce a conformation close to the experimental structure (typically with an RMSD < 1.0 Å).

2. Why is my conformer generation process computationally expensive and slow for a large compound library?

High computational cost is typically due to the generation of an excessive number of conformers or the use of overly precise, time-consuming methods.

- Problem: The computational parameters are set for exhaustive analysis rather than high-throughput screening.

- Solution: Adjust the parameters to balance computational cost with the required level of conformational coverage.

- Actionable Steps:

- Use a "Fast" Mode: Many software packages like Discovery Studio offer a "Fast" mode for conformer generation, which uses modified search algorithms to speed up the process [1].

- Limit Output Conformers: Instead of generating all possible conformers, set the software to output a diverse but limited set (e.g., 50-100 conformers) based on RMSD clustering. OMEGA, for instance, uses rule-based sampling and diverse ensemble selection for high speed (around 0.08 seconds/molecule) while maintaining quality [13].

- Pre-generate Conformational Databases: For frequently screened databases, pre-generate and store the conformational ensembles, so they do not need to be calculated on-the-fly for every new screening campaign.

3. How can I ensure my model accounts for protein flexibility and solvent effects, not just ligand energy barriers?

Traditional ligand-based sampling may miss critical interactions stabilized by the protein environment or water molecules.

- Problem: The pharmacophore model is based solely on ligand conformations in a vacuum, missing key interaction features present in the solvated protein binding site.

- Solution: Incorporate protein and solvent information into the pharmacophore generation process.

- Actionable Steps:

- Employ Water-Based Pharmacophore Modeling: Use Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations of the water-filled, ligand-free (apo) protein structure. Analyze the simulation to identify interaction hotspots where water molecules consistently bind, and convert these into pharmacophore features [14].

- Use Dynamic Pharmacophores (Dynophores): Run MD simulations of a protein-ligand complex and extract pharmacophore features across the entire trajectory. This captures the dynamic flexibility of both the ligand and the protein [14].

- Leverage Structure-Based Design: If a protein structure is available, use software like MOE to create a pharmacophore model directly from the binding site features, which inherently includes protein constraints [15].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the key software tools for conformational sampling and pharmacophore modeling, and how do they compare? Several software packages are industry standards, each with strengths in specific tasks. The table below summarizes key tools and their applications.

| Software | Primary Function | Key Features & Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| MOE (Molecular Operating Environment) [8] [15] | Comprehensive molecular modeling & simulation. | Features systematic and stochastic search methods. Useful for detailed conformational analysis and high-throughput 3D library generation. Integrates pharmacophore modeling, docking, and QSAR in one platform [8]. |

| Discovery Studio (DS) [12] [15] | Protein small-molecule modeling & simulation. | Contains the HypoGen algorithm for ligand-based pharmacophore model generation. Includes "Fast" and "Best" conformer generation modes for virtual screening [12] [1]. |

| OMEGA [13] | Conformer generation. | Specialized, high-speed tool for generating large conformer databases. Excellent at reproducing bioactive conformations. Optimal for pre-generating conformers for virtual screening with tools like ROCS or FRED [13]. |

| LigandScout [15] | Pharmacophore modeling & virtual screening. | Creates structure- and ligand-based pharmacophores with an intuitive interface. Known for advanced visualization of pharmacophore-ligand interactions [15]. |

| Schrödinger Phase [15] | Ligand-based drug design. | Specializes in ligand-based pharmacophore modeling and 3D-QSAR, helping to understand Activity Cliffs [15]. |

Q2: What are the critical parameters to validate a generated pharmacophore model? A robust pharmacophore model must be statistically validated before use in screening. The following table outlines key validation metrics and their ideal values, as demonstrated in a study on tubulin inhibitors [12].

| Validation Method | Metric | Ideal Value / Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Cost Analysis | Total Cost vs. Null Cost | A large difference (>60 bits) indicates a high probability (>90%) of a true correlation [12]. |

| Correlation Coefficient (R) | Should be close to 1 (e.g., a reported value of 0.9582) [12]. | |

| Fischer Randomization | Confidence Level | At 95% confidence, no randomized model should be significantly better than the original [12]. |

| Decoy Set / Test Set | Goodness of Hit Score (GH) | Score close to 1 (e.g., 0.81) indicates a strong ability to identify active compounds and reject inactives [12]. |

| Leave-One-Out | Correlation Stability | The model's predictive power (R) remains stable when any single training compound is omitted [12]. |

Q3: Can you outline a standard workflow for a pharmacophore-based virtual screening campaign? The diagram below illustrates a typical and validated workflow for identifying novel lead compounds using pharmacophore modeling.

Validated Workflow for Pharmacophore Screening

Q4: What essential "research reagents" are needed for a computational pharmacophore modeling study? The table below lists the key computational "materials" required to perform a typical pharmacophore modeling experiment.

| Research Reagent | Function & Description |

|---|---|

| Training Set Compounds | A set of known active (and ideally inactive) compounds with experimental activity data (e.g., IC50). Their structures and activities are used to build the model [12]. |

| 3D Compound Database | A large commercial (e.g., Specs, Maybridge) or proprietary database of small molecules to screen for new hits [12] [16]. |

| Molecular Modeling Software | A platform like MOE or Discovery Studio that provides tools for conformer generation, pharmacophore building, and visualization [12] [15]. |

| Conformer Generation Algorithm | The computational engine (e.g., within MOE, OMEGA, or Catalyst) that produces multiple 3D structures for each molecule to represent its conformational space [12] [13] [8]. |

| Protein Structure (Optional) | A 3D structure of the target (e.g., from PDB) for structure-based pharmacophore modeling or validating hits via molecular docking [12] [14]. |

Experimental Protocol: Building a Validated Quantitative Pharmacophore Model

This protocol details the methodology used in a published study to create a quantitative pharmacophore model for tubulin inhibitors, which successfully identified new active compounds against human breast cancer cells [12].

1. Data Set Preparation:

- Training Set: Select a diverse set of compounds (e.g., 26 compounds) with known biological activities (IC50) spanning a wide range (e.g., four orders of magnitude). Ensure all activity data is obtained from consistent experimental assays [12].

- Test Set: Prepare a separate set of compounds (e.g., 40 compounds) for validating the model's predictive power [12].

- Conformer Generation: For all compounds, generate multiple conformers using the "Best Conformation Generation" option in software like Discovery Studio. Use a maximum of 250 conformers and an energy threshold of 10 kcal/mol above the global minimum [12].

2. Pharmacophore Model Generation (using HypoGen in Discovery Studio):

- Input: Submit the training set compounds and their activities to the HypoGen algorithm.

- Features: Specify the chemical features to be considered, such as Hydrogen-Bond Acceptor (HBA), Hydrogen-Bond Donor (HBD), Hydrophobic (HY), and Ring Aromatic (RA) [12].

- Hypothesis Selection: The algorithm will generate multiple hypotheses (e.g., 10). Select the best model based on:

- Highest Correlation Coefficient (close to 1.0).

- Lowest Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD).

- Largest Cost Difference between the total cost and the null cost (a difference >60 bits indicates a >90% chance of being a true model) [12].

3. Pharmacophore Model Validation:

- Test Set Prediction: Use the model to predict the activities of the test set compounds. A good correlation between predicted and experimental activities indicates strong predictive ability [12].

- Fischer Randomization: Perform a randomization test at a 95% confidence level. The original hypothesis should have significantly lower costs and higher correlation than models built from randomized activity data [12].

- Decoy Set Validation: Screen a database containing known active and inactive compounds (decoys). Calculate the Goodness of Hit Score (GH), which should be close to 0.8-1.0 for a good model [12].

- Formula: ( GH = \left[\frac{Ha}{4HtA}\right] \times \left(1 - \frac{Ht - Ha}{D - A}\right) )

- Where (Ha) is the number of active hits found, (Ht) is the total hits, (A) is the number of actives in the database, and (D) is the total compounds in the database [12].

4. Virtual Screening and Hit Identification:

- Database Screening: Use the validated pharmacophore model (e.g., Hypo1) as a 3D query to screen a commercial database (e.g., Specs database).

- Drug-Like Filtering: Filter the hits based on Lipinski's Rule of Five to prioritize drug-like molecules [12].

- Molecular Docking: Further refine the hit list by docking the compounds into the target protein's binding site (e.g., the colchicine-binding site of tubulin). Select compounds with favorable binding free energies (e.g., < -4 kcal/mol) and interactions with key amino acid residues [12].

- Experimental Validation: Select top-ranking compounds for in vitro biological evaluation to confirm inhibitory activity (e.g., against MCF-7 human breast cancer cells) [12].

The concept of the pharmacophore, defined as "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or to block) its biological response," has been fundamental to drug discovery for decades [17] [4]. Traditionally, pharmacophore models were derived from static representations, either from a single protein-ligand complex structure (structure-based) or from a set of active molecules (ligand-based). However, proteins and ligands are inherently dynamic entities, constantly interacting with each other and their aqueous environment, following a specific conformation distribution known as a thermodynamic ensemble [18]. These static snapshots, often obtained from X-ray crystallography, only capture an average conformational state and neglect the dynamic patterns essential for binding [18] [19].

This technical guide frames its troubleshooting advice within the context of a broader thesis: addressing conformational sampling is the central challenge in modern pharmacophore modeling research. The field is undergoing a fundamental evolution from relying on static snapshots to embracing dynamic representations. This shift is critical because the actual binding affinities are determined by the thermodynamic ensembles of protein-ligand complexes, not single structures [18]. The following sections will provide scientists with targeted troubleshooting guidance, framed by this conceptual evolution, to navigate the practical challenges of implementing dynamic pharmacophore methods.

Core Technical Challenges & Troubleshooting FAQs

Conformational Sampling and Ensemble Generation

FAQ 1: How do I generate a biologically relevant conformational ensemble for my ligand, and why is a single structure insufficient?

A single, static 3D structure is often insufficient for pharmacophore modeling because a molecule's bioactive conformation—the shape it adopts when bound to its target—may not be its global energy minimum in solution [1]. The goal of conformational sampling is to generate a set of diverse, low-energy structures that adequately represent the conformational space a ligand can explore, ensuring the bioactive conformation is included.

- Underlying Cause: The failure to identify the bioactive conformation arises because, during binding, a ligand transitions from an unbound state in aqueous solution to a bound state exposed to directed electrostatic and steric forces from the target protein. Enthalpic and entropic contributions can stabilize a bound geometry different from the ligand's conformation in solution or a crystal [1].

- Recommended Solution: Employ a robust conformer generator that uses systematic or stochastic methods to sample rotatable bonds. The general workflow involves analyzing the input molecule, fragmenting it at rotatable bonds, applying torsion rules to assemble fragments into full 3D structures, and then optimizing and filtering the resulting conformers [20].

Troubleshooting Guide: Conformer Generation Failures

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| The generated conformer ensemble misses the known bioactive conformation (high RMSD). | Insufficient sampling of rotatable bonds; energy window too tight; algorithm uses too coarse torsion angle increments. | Increase the maximum number of conformers (e.g., from 100 to 250). Widen the energy window threshold (e.g., from 10 to 20 kcal/mol above the calculated minimum). Use a "best quality" setting that employs finer torsion angle steps [8] [20]. |

| The conformer ensemble is too large, slowing down virtual screening. | Over-sampling of similar states; insufficient clustering or redundancy filtering. | Apply a clustering algorithm based on RMSD matrices to filter out unrepresentative conformers and reduce ensemble size while maintaining coverage of conformational space [20]. |

| Poor performance in virtual screening, with many false positives. | Ensembles may contain unrealistic, high-energy conformations that are never populated. | Apply a more stringent energy cutoff and post-process generated conformers with a force field to eliminate steric clashes and high-energy strains [1]. |

Integrating Dynamics with Molecular Simulation

FAQ 2: How can I use Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations to create better, more dynamic pharmacophore models, and what are the common pitfalls?

Static crystal structures fail to capture the flexibility and collective atomic motions that define protein-ligand interactions. MD simulations provide a powerful way to approximate the thermodynamic ensemble, sampling multiple conformations that collectively contribute to binding affinity [18] [21].

- Underlying Cause: A pharmacophore model derived from a single static structure may only represent one "frame" of a dynamic binding process. Critical interactions might be transient, or alternative binding modes may exist that are not visible in the crystal [19] [21].

- Recommended Solution: Run an MD simulation of the protein-ligand complex. From the resulting trajectory, extract hundreds or thousands of snapshots. Generate a structure-based pharmacophore model from each snapshot to create a collection of models representing the dynamic interaction profile [18] [21].

Troubleshooting Guide: MD-Driven Pharmacophore Modeling

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| The number of pharmacophore models from the MD trajectory is unmanageably large. | Lack of strategy to reduce and prioritize models from thousands of simulation snapshots. | Instead of using all models, use a hierarchical graph representation (HGPM) to visualize the relationship between models and select a representative subset based on feature composition and hierarchy [21]. |

| Difficulty selecting the "best" pharmacophore model from an MD ensemble for virtual screening. | The concept of a single "best" model is flawed when dealing with dynamic systems; different interaction patterns are valid at different times. | Use a consensus scoring approach like the Common Hits Approach (CHA). Screen your compound library against the entire ensemble of models and rank compounds by how many different models they match, prioritizing versatile binders [21]. |

| MD simulation shows the ligand departing the binding site (high RMSD). | The simulated complex may be unstable, potentially indicating a low-affinity binder, or the simulation time may be too short for the system to equilibrate. | Analyze the stability. If the ligand quickly leaves, it may correlate with low experimental affinity [18]. Ensure proper system equilibration and consider longer simulation times to observe stable binding if the ligand is known to be potent. |

Virtual Screening with Dynamic Pharmacophores

FAQ 3: My virtual screening with a dynamic pharmacophore ensemble is computationally expensive and yields confusing results. How can I optimize this process?

Screening a million-compound library against 1,000 pharmacophore models means a billion individual comparisons, which is computationally prohibitive. The challenge is to leverage the dynamic information without excessive cost.

- Underlying Cause: The computational burden stems from a "brute force" approach to screening. The confusing results (e.g., a high number of hits or poorly ranking known actives) can arise from poorly selected or redundant pharmacophore models [21].

- Recommended Solution: Prioritize a diverse subset of pharmacophore models from the MD ensemble using the HGPM or clustering. Alternatively, use a pharmacophore-based scoring function within a docking workflow, which can incorporate dynamic information in a single scoring step [22].

Troubleshooting Guide: Virtual Screening Performance

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Virtual screening is too slow with a dynamic pharmacophore ensemble. | Too many models are being used in the screening process. | Use the HGPM to select a strategic, limited set of models that cover the major observed interaction patterns, drastically reducing the number of required screening runs [21]. |

| High false positive rate from screening. | Pharmacophore models may be too general or lack exclusion volumes to define the shape of the binding pocket. | Add exclusion volumes (XVOL) to your pharmacophore models to represent forbidden areas, mimicking the steric constraints of the binding site and reducing false positives [4]. |

| Known active compounds are not retrieved (high false negative rate). | The conformational ensemble of the database molecules is inadequate and misses the conformation needed to match the pharmacophore query. | For the screening database, ensure you use a high-quality conformer generator (e.g., iCon, OMEGA) with settings that produce a diverse, representative set of conformations for each molecule, ensuring the bioactive pose is present [4] [20]. |

Essential Protocols for Dynamic Pharmacophore Generation

Protocol: Generating a Dynamic Pharmacophore Ensemble from an MD Trajectory

This protocol details how to move from a single static model to a dynamic ensemble using Molecular Dynamics, as exemplified in studies on systems like human glucokinase [21].

System Preparation:

- Obtain the initial protein-ligand complex structure from the PDB.

- Use software like Maestro (Schrodinger) to prepare the protein: add hydrogen atoms, assign protonation states, and perform a brief energy minimization.

- Set up the solvated system using a tool like CHARM-GUI, adding water molecules and ions to neutralize the system.

Molecular Dynamics Simulation:

- Use a package like AMBER or GROMACS.

- Begin with an equilibration and thermalization phase (e.g., 125 ps) to relax the system.

- Run the production simulation (e.g., 100-300 ns) with a 2 fs time step at the desired temperature (e.g., 303.15 K) and pressure (1 atm). Running multiple replicates with different initial velocities is recommended for better sampling.

- Save snapshots of the trajectory at regular intervals (e.g., every 100 ps) for analysis.

Pharmacophore Model Generation:

- For each saved snapshot from the MD trajectory, use a structure-based pharmacophore modeling tool like LigandScout.

- The software will automatically detect interactions (hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, ionic interactions) between the protein and ligand in each frame and convert them into a pharmacophore model with specific features (HBA, HBD, H, PI, NI) and exclusion volumes.

Ensemble Analysis and Prioritization:

- Use the Hierarchical Graph Representation of Pharmacophore Models (HGPM) to visualize all unique models and their relationships.

- Analyze the graph to select a diverse and representative subset of models for virtual screening, based on the frequency and combination of features [21].

Protocol: Ligand-Based Conformational Sampling for Virtual Screening

This protocol is essential for preparing a high-quality 3D database for pharmacophore-based virtual screening, ensuring database molecules are represented by a realistic set of conformations [20].

Input Preparation:

- Compile your database of small molecules in SMILES format. Using a canonical SMILES string as input avoids bias from a starting 3D geometry.

Conformer Generation with iCon (or equivalent):

- Use a conformer generator like iCon in LigandScout or OMEGA.

- Key Settings for iCon:

- Set the maximum number of conformers per molecule (e.g., 100-250).

- Define an energy window (e.g., 10-20 kcal/mol) to discard high-energy conformers.

- Set an RMSD threshold for clustering to remove redundant conformers.

- The algorithm will systematically fragment the molecule, apply torsion rules, assemble conformers, and optimize them with a force field.

Database Creation and Validation:

- The output is a multi-conformer 3D database file (e.g., in .idb format for LigandScout).

- Validate the quality of the conformational ensembles by checking if they can reproduce the known bioactive conformation of a set of test ligands from the PDB, typically measured by Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

Table: Key Software Tools for Advanced Pharmacophore Modeling

| Category | Tool Name | Primary Function | Key Application in Dynamic Modeling |

|---|---|---|---|

| MD Software | AMBER, GROMACS, CHARMM | Perform molecular dynamics simulations. | Generates the thermodynamic ensemble of protein-ligand complexes by simulating atomic movements over time [18] [21]. |

| Conformer Generator | iCon, OMEGA, CAESAR | Generate multiple 3D conformations for a single small molecule. | Creates representative conformational ensembles for database molecules before virtual screening, ensuring bioactive poses are present [20]. |

| Pharmacophore Modeling | LigandScout, Catalyst | Create, visualize, and manage structure-based and ligand-based pharmacophore models. | Automatically generates a pharmacophore model from each snapshot of an MD trajectory [4] [21]. |

| Analysis & Visualization | Hierarchical Graph (HGPM) | Visualizes relationships between hundreds of pharmacophore models from an MD simulation. | Aids in the intuitive selection and prioritization of a representative subset of models for virtual screening, managing complexity [21]. |

| Virtual Screening | LigandScout, GEMDOCK | Screen large compound databases against pharmacophore models or using pharmacophore-constrained docking. | Identifies novel hit compounds by matching against dynamic pharmacophore ensembles; GEMDOCK uses a pharmacophore-based scoring function [22] [21]. |

From Theory to Practice: A Toolkit of Conformational Sampling Methods for Pharmacophores

FAQs: Core Concepts in Molecular Sampling

Q1: What is the primary goal of conformational sampling in pharmacophore modeling? The primary goal is to generate a diverse and pharmacologically relevant set of three-dimensional structures (conformational ensembles) for a molecule. This ensures that the bioactive conformation—the 3D geometry a molecule adopts when bound to its target—is included in the set, which is critical for the success of subsequent steps like 3D pharmacophore searches, molecular docking, and 3D-QSAR studies [1] [23]. Success heavily relies on the quality and conformational diversity of the 3D structures used [1].

Q2: How do systematic and stochastic sampling methods fundamentally differ?

- Systematic Search methods aim to explore the entire conformational space in an exhaustive, iterative manner by rotating torsion bonds through a grid of defined increments [1] [23]. They provide complete coverage of the defined search space but can be computationally slow for molecules with many rotatable bonds.

- Stochastic Search methods (e.g., Monte Carlo, Genetic Algorithms) use random or directed perturbations to alter a starting conformation, often guided by an energy function in a feedback loop [1] [23]. They are trajectory-based and seek to restrict the search to low-energy conformations, which can be faster but may not guarantee complete coverage.

Q3: When should I prefer a simulation-based approach like Molecular Dynamics? Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations are particularly valuable when you need to account for the flexibility and dynamic behavior of both the ligand and the protein target in a solvated environment. They capture the time-dependent evolution of the molecular system, allowing you to observe conformational changes, binding pathways, and stability of interactions that static methods might miss [24]. The integration of AI can now approximate force fields and capture conformational dynamics, enhancing their power [25].

Q4: What are the consequences of inadequate conformational coverage? Inadequate coverage can lead to two main problems:

- False Negatives: The bioactive conformation is not generated, so the molecule will be missed in a pharmacophore search or show poor predicted affinity in docking [1].

- False Positives: An overabundant or poorly diverse conformational ensemble can dramatically increase the number of false positive hits, as non-meaningful conformations may accidentally match a pharmacophore query [1].

Q5: How can AI and deep learning improve conformational sampling and pharmacophore modeling? AI, particularly deep learning, introduces powerful new paradigms. For example, deep generative models can create novel molecules that match a given pharmacophore hypothesis directly, bypassing traditional search methods [26]. Graph neural networks can encode spatially distributed pharmacophore features, and transformers can learn to generate valid molecular structures that satisfy these constraints, offering a flexible strategy for de novo drug design, especially when active molecule data is scarce [26] [25].

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Systematic Searches

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Excessive computation time | Too many rotatable bonds; overly fine angular increment. | Use a larger torsion angle increment (e.g., 60° instead of 30°); employ a fragment-based systematic search that recombines pre-computed low-energy fragments [23]. |

| Missed bioactive conformation | Conformer energy window too narrow; ring conformations not sampled. | Widen the maximum energy cutoff for retaining conformers; incorporate ring conformation sampling (e.g., via different ring templates) into the workflow [1]. |

| Too many similar conformers | Insufficient RMSD pruning; angular increment too small. | Apply a clustering algorithm (e.g., based on heavy atom RMSD) to remove redundant conformations and retain only diverse representatives [23]. |

Troubleshooting Stochastic Searches

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Non-reproducible results | Use of a random number generator without a fixed seed. | Set a fixed random seed at the beginning of the simulation to ensure the same sequence of "random" perturbations is generated each run. |

| Poor diversity in output ensemble | Insufficient number of search iterations; over-reliance on a single low-energy basin. | Increase the number of Monte Carlo steps or genetic algorithm generations; introduce a "poling" term or use a diversity-picking algorithm to ensure broad coverage [1]. |

| High-energy, unrealistic conformers | Inadequate energy minimization; poor scoring function. | Ensure every generated conformation undergoes a local energy minimization step post-perturbation. Validate the force field or scoring function for your specific molecule class [23]. |

General Sampling and Modeling Issues

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Failure to retrieve known active compounds in a pharmacophore screen | Bioactive conformation not generated; pharmacophore query is too rigid. | Verify the conformational ensemble for known actives contains a conformation close to the bioactive one (e.g., from a crystal structure). Introduce some flexibility or tolerance into the pharmacophore feature definitions [1]. |

| Low success rate in molecular docking | Generated conformers are not pre-optimized for the force field; ligand strain energy is high. | Pre-optimize generated conformers using the same force field that will be used in the docking software. Consider the strain energy of the docked pose as a post-filter [23]. |

| High false positive rate in virtual screening | Conformational ensemble is too large and contains implausible geometries. | Use a knowledge-based filter derived from databases like the CSD or PDB to remove conformations with unlikely torsion angles or steric clashes [1] [23]. |

Comparative Performance Data

Table 1: Performance Benchmarking of Various Conformational Sampling Methods on the Vernalis Dataset [23]

| Method | Recovery Rate of Bioactive Conformation (≤ 2.0 Å RMSD) | Key Characteristics | Relative Speed |

|---|---|---|---|

| BCL::Conf | 99% | Knowledge-based "rotamer" library from CSD/PDB; Monte Carlo search [23]. | Medium |

| ConfGen | >99% | Torsion-driven systematic search; comprehensive coverage [23]. | Medium |

| MOE | >99% | Offers multiple methods, including stochastic and systematic search modes [8] [23]. | Medium |

| OMEGA | >99% | Rule-based torsion drives; highly optimized for speed [23]. | Fast |

| RDKit | >99% | Open-source; uses distance geometry and knowledge-based torsion preferences [23]. | Medium |

Table 2: Key Metrics for Deep Learning-Based Molecular Generation (PGMG) Guided by Pharmacophores [26]

| Metric | Description | PGMG Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Validity | Percentage of generated strings that correspond to valid molecular structures. | >90% (Comparable to top models) |

| Uniqueness | Percentage of unique molecules among the valid generated structures. | >90% (Comparable to top models) |

| Novelty | Percentage of generated molecules not present in the training dataset. | Best in class performance |

| Available Molecules Ratio | A combined metric assessing the model's ability to generate novel, valid, and unique molecules. | Improved by 6.3% over other methods |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Knowledge-Based Conformational Sampling with BCL::Conf

This protocol outlines the steps for generating a diverse conformational ensemble using the knowledge-based and fragment-centric BCL::Conf approach [23].

- Input Preparation: Provide the small molecule of interest in a standard format (e.g., SDF, SMILES).

- Fragment Decomposition: The algorithm iteratively breaks non-ring bonds in the input molecule to generate all possible molecular fragments.

- Rotamer Library Lookup: Each generated fragment is matched against a pre-computed library of "rotamers." This library contains frequently observed conformations for these fragments, derived from structural databases (CSD and PDB), represented as sets of discrete dihedral angle bins.

- Monte Carlo Recombination: A Monte Carlo search strategy is used to recombine the low-energy conformations of the individual fragments into complete conformations of the original molecule.

- Scoring and Clustering: The resulting conformations are scored using a knowledge-based scoring function that evaluates the probability of the constituent fragment conformations and a clash score to avoid steric overlaps. Finally, conformers are clustered based on RMSD to ensure diversity in the output ensemble.

Protocol: Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling and Virtual Screening

This protocol describes a workflow for identifying hit compounds by creating a pharmacophore model from a protein-ligand complex and using it for virtual screening [27].

- Template Preparation: Obtain the 3D structure of the target protein (e.g., PD-L1, PDB ID: 6R3K) in complex with a small-molecule inhibitor. Prepare the structure by adding hydrogen atoms, assigning bond orders, and optimizing hydrogen bonds.

- Pharmacophore Feature Generation: Analyze the binding site and the interactions between the protein and the co-crystallized ligand. Define key chemical features (e.g., Hydrogen Bond Donor (HBD), Hydrogen Bond Acceptor (HBA), Hydrophobic (H), Positively/Inegatively Charged (P/N)) that are critical for the binding.

- Model Validation: Validate the generated pharmacophore model using a Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve. A high Area Under the Curve (AUC) value (e.g., >0.8) indicates a good ability to distinguish between active and inactive compounds [27].

- Virtual Screening: Use the validated pharmacophore model as a 3D query to screen a large database of compounds (e.g., a marine natural product database). Retrieve compounds that match all or most of the defined pharmacophore features.

- Post-Screening Analysis: Subject the hit compounds from the pharmacophore screen to molecular docking to refine the binding pose and predict affinity. Further filter the top candidates using ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, Toxicity) prediction and molecular dynamics simulations to assess binding stability.

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Conformational Sampling and Pharmacophore Modeling Workflow

Diagram Title: Conformational Sampling and Pharmacophore Modeling Workflow

Stochastic Search Process

Diagram Title: Stochastic Search Process

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Software Tools for Conformational Sampling and Pharmacophore Modeling

| Software/Tool | Function | Key Application in Sampling |

|---|---|---|

| MOE | Integrated drug discovery suite | Provides multiple conformational sampling methods (systematic, stochastic); used in comparative performance studies [8] [23]. |

| BCL::Conf | Open-source conformer generator | Employs a knowledge-based rotamer library from CSD/PDB and Monte Carlo search for efficient sampling [23]. |

| OMEGA | High-throughput conformer generator | Uses a rule-based, systematic torsion-driven approach, optimized for speed in virtual screening [1] [23]. |

| RDKit | Open-source cheminformatics toolkit | Provides general-purpose conformer generation using distance geometry and knowledge-based torsion angles [26] [23]. |

| AutoDock Vina | Molecular docking software | Not a sampler itself, but relies on the conformational ensemble provided to it for docking; scoring function evaluates binding affinity [27]. |

| NONMEM | Population PK/PD modeling | Used for stochastic simulation and estimation (SSE) in clinical pharmacology, not molecular conformations, but a key tool for simulation-based sampling in PK study design [28]. |

| PGMG | Deep learning model | A pharmacophore-guided deep learning approach for bioactive molecule generation, representing a new paradigm beyond traditional sampling [26]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Issues and Solutions

Problem: Inability to Recover Native Protein-Bound Ligand Conformation

- Issue: Generated conformational ensembles do not contain a conformation close (e.g., within 2Å RMSD) to the experimental protein-bound structure.

- Solutions:

- Verify Input Structure: Ensure the initial 3D conformation of your ligand is reasonable. For benchmarking, it is common practice to use input structures generated by tools like NAOMI to ensure a standardized starting point [29].

- Increase Ensemble Size: The probability of recovering the native conformation increases with the number of conformers generated. BCL::Conf has been shown to achieve high recovery rates (≥99% for a 2Å threshold in benchmark studies) with sufficiently large ensembles [23].

- Check for Unusual Fragments: The knowledge-based approach relies on fragments found in structural databases. If your ligand contains a unique or rare chemical fragment not well-represented in the rotamer library, sampling may be limited. Consult the library coverage statistics [23] [29].

Problem: Low Diversity in Generated Conformational Ensemble

- Issue: The generated conformers are too similar to each other, failing to represent the full range of accessible conformational space.

- Solutions:

- Adjust Sampling Parameters: Utilize the Monte Carlo search strategy within BCL::Conf, which is designed to explore diverse conformational states. Ensure the number of iterations is set high enough to allow adequate exploration [23].

- Review Torsional Sampling: The algorithm samples from discrete dihedral angle bins (e.g., 30° intervals) based on frequently observed rotamers. Low diversity may indicate that the ligand's torsional preferences are dominated by a few highly frequent rotamers. Manually inspecting the torsional profiles for key bonds can confirm this [23].

Problem: Excessive Computational Time or Memory Usage

- Issue: Conformer generation is slow or fails due to high resource demands.

- Solutions:

- Simplify the Molecule: For very large and flexible molecules, consider simplifying the structure or focusing on a core fragment for initial sampling.

- Fragment-Based Efficiency: The BCL::Conf method was designed for efficiency by reusing pre-computed fragment conformations. Performance issues with large molecules may be inherent to the complexity of the system. The algorithm is generally fast, with benchmarks showing rapid conformer generation rates [29].

Problem: Poor Results in Pharmacophore Screening with CSD-CrossMiner

- Issue: Searches of the CSD or PDB using a pharmacophore query return too few or irrelevant hits.

- Solutions:

- Refine Query Definition: Ensure your pharmacophore features (e.g., hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, ring centroids, hydrophobic regions) are accurately defined and positioned. Use the interactive interface in CSD-CrossMiner to adjust your hypothesis in real-time [30].

- Use Excluded Volumes: To better mimic a protein binding site and filter out unrealistic matches, add excluded volumes to your pharmacophore query. This acts as a "NOT" function to exclude hits that occupy sterically forbidden regions [30].

- Customize Feature Definitions: Take advantage of the ability to customize pharmacophore feature definitions to match the specific chemical context of your target, which can improve search granularity and result quality [30].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the key differences between the older BCL::Conf2016 and the updated BCL::Conf? The updated BCL::Conf incorporates several major improvements [29]:

- Source Database: Transitioned from a rotamer library derived from the Cambridge Structural Database (CSD), which requires a license, to one built from the open-access Crystallography Open Database (COD).

- Sampling Scope: The new version can resample bond angles and lengths from statistical distributions in the library, whereas BCL::Conf2016 primarily sampled dihedral angles and ring conformations.

- Algorithm Enhancements: The updated sampling algorithm includes more sophisticated handling of ring systems and chain dihedral bonds, and incorporates steps to resolve atomic clashes.

Q2: My research involves scaffold hopping. How can knowledge-based approaches using the CSD and PDB assist me? Tools like CSD-CrossMiner are particularly valuable for this purpose. You can build a pharmacophore query based on the essential features of your known active scaffold. Simultaneously mining the CSD and PDB with this query can identify different molecular scaffolds (new core structures) that present the same spatial arrangement of pharmacophoric features, enabling the discovery of novel lead compounds [31] [30].

Q3: Why is my structure not returning results in an RCSB PDB Structure Similarity Search? When using the Structure Similarity Search on RCSB PDB, ensure you have selected the correct options [32]:

- Search Hierarchy: Specify whether you are querying with a single polymer chain or a biological assembly. A search defined with an assembly ID will, by default, search for other assemblies.

- Matching Mode: Choose between "Strict" (fewer, more relevant matches) and "Relaxed" (more, but potentially less precise matches) modes based on your goal.

- Include CSMs: If you want to search against computed structure models from AlphaFold, etc., remember to toggle the "Include CSM" switch.

Q4: How does BCL::Conf's performance compare to other conformer generators like RDKit or Omega? Benchmarking on the Platinum diverse dataset (containing over 2800 high-quality protein-ligand structures) shows that the improved BCL::Conf performs at the state of the art. It has been demonstrated to significantly outperform the CSD conformer generation algorithm in recovering protein-bound ligand conformations across various ensemble sizes, with similarly fast generation rates [29]. Earlier versions were competitive with tools like RDKit and Frog [23].

Performance Benchmarking Data

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Conformer Generation Tools on the Platinum Diverse Dataset This table summarizes benchmark results for native conformer recovery as reported in the literature. Performance is typically measured by the percentage of ligands for which a conformer within a specified Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD) of the experimental structure is found [29].

| Tool / Algorithm | Recovery Rate (≤2.0 Å RMSD) | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| BCL::Conf (Current) | Significantly outperforms CSD Conformer Generator [29] | Knowledge-based; COD rotamer library; Monte Carlo sampling |

| CSD Conformer Generator | State-of-the-art benchmark [29] | Knowledge-based; CSD rotamer library (license required) |

| RDKit (ETKDG) | Competitive with earlier BCL::Conf [23] | Distance geometry; heuristic rules from CSD |

| OMEGA | Frequently used in comparative studies [29] | Rule-based; systematic torsion sampling |

| BCL::Conf2016 | ~99% on Vernalis benchmark (≤2.0 Å) [23] | Knowledge-based; CSD rotamer library; predecessor to current version |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Generating a Conformational Ensemble with BCL::Conf

Objective: To generate a diverse, low-energy conformational ensemble for a small molecule that includes its potential protein-bound conformation.

Methodology: Knowledge-based sampling using a fragment rotamer library [23] [29].

- Input Preparation: Provide the small molecule as a 1D representation (SMILES) or a 2D/3D structure (SDF/MOL file). For benchmarking, a 3D structure generated by a tool like NAOMI is recommended.

- Fragment Identification: The algorithm decomposes the input molecule and identifies all substructures (fragments) that map to those in its pre-computed rotamer library. This library was derived by statistically analyzing fragment conformations from thousands of crystal structures in the COD (or CSD for older versions).

- Conformer Sampling:

- A Monte Carlo algorithm is used to sample the conformational space.

- In each iteration, the algorithm randomly selects a mapped fragment and applies one of its observed rotameric conformations to the molecule, based on the frequency of that rotamer in the database.

- The process cycles through all rotatable bonds and ring systems, sampling dihedral angles, bond angles, and lengths from the statistical distributions in the library.

- Scoring and Clash Check: Each newly generated conformation is scored using a knowledge-based scoring function that evaluates the probability of the constituent fragment rotamers. Conformations with severe atomic clashes are rejected or minimized.

- Ensemble Output: The final output is a set of diverse, low-clash 3D conformers. The user can specify the desired number of conformers in the final ensemble.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the BCL::Conf conformational sampling process:

Protocol 2: Conducting a Pharmacophore Search with CSD-CrossMiner

Objective: To identify potential hit compounds or bioisosteres by searching structural databases for molecules matching a defined pharmacophore model.

Methodology: 3D pharmacophore-based virtual screening [30] [33].

- Query Definition:

- Launch CSD-CrossMiner and load a reference structure (e.g., a ligand from a PDB complex or your lead compound).

- Define the critical pharmacophore features directly from the 3D structure. Core features include:

- Hydrogen Bond Donor (Blue)

- Hydrogen Bond Acceptor (Red)

- Hydrophobic Region (Yellow)

- Ring Plane (Green)

- (Optional) Add excluded volumes to represent steric constraints of the binding pocket.

- Database Selection: Select the target databases to search. CSD-CrossMiner allows simultaneous searching of the Cambridge Structural Database (CSD), the Protein Data Bank (PDB), and in-house proprietary databases.

- Interactive Search and Refinement: Execute the search. The interface allows for real-time refinement of the pharmacophore query. You can adjust feature positions, add/remove features, or modify excluded volumes based on the initial results to improve hit relevance.

- Analysis of Results: Review the matching structures. The software allows you to visualize how the hit molecules align with your pharmacophore query. Results can be filtered and sorted to identify the most promising scaffolds or fragments for further investigation.

Table 2: Key Databases and Software for Knowledge-Based Drug Discovery

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Key Application in Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cambridge Structural Database (CSD) | Database | Curated repository of experimentally determined small-molecule organic crystal structures. | Source of empirical data on small molecule geometry, torsional preferences, and intermolecular interactions for rotamer libraries and pharmacophore validation [23] [31]. |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Database | Global archive for 3D structural data of proteins, nucleic acids, and their complexes with ligands [34]. | Source of protein-ligand bound conformations for benchmarking conformer generators and understanding bioactive conformations [23] [35]. |

| Crystallography Open Database (COD) | Database | Open-access collection of crystal structures of organic, inorganic, and metal-organic compounds. | An open-source alternative to the CSD for deriving knowledge-based rotamer libraries in tools like BCL::Conf [29]. |

| BCL::Conf | Software | Knowledge-based conformer generation algorithm. | Rapidly generates diverse conformational ensembles for small molecules by leveraging a fragment rotamer library, crucial for docking and pharmacophore modeling [23] [29]. |

| CSD-CrossMiner | Software | Pharmacophore-based search and data mining tool. | Enables scaffold hopping and bioisostere replacement by searching structural databases with 3D pharmacophore queries [30] [33]. |

| RCSB PDB Structure Similarity Search | Web Tool | Searches the PDB archive using 3D shape similarity. | Identifies proteins or complexes with similar 3D shapes, which may suggest similar function despite low sequence similarity [32]. |

The following diagram illustrates the relationships and data flow between these key resources in a typical knowledge-based research workflow:

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is DiffPhore and how does it fundamentally differ from traditional pharmacophore tools? DiffPhore is a knowledge-guided diffusion framework designed for "on-the-fly" 3D ligand-pharmacophore mapping (LPM). Unlike traditional tools that often rely on rigid matching algorithms, DiffPhore leverages a deep learning-based generative approach. It consists of three core modules: a knowledge-guided LPM encoder that captures pharmacophore type and direction matching rules, a diffusion-based conformation generator that iteratively denoises ligand poses, and a calibrated conformation sampler that reduces exposure bias during inference. This allows it to generate ligand conformations that maximally align with a given pharmacophore model, significantly enhancing performance in binding pose prediction and virtual screening [9] [36].

Q2: What are the CpxPhoreSet and LigPhoreSet datasets, and why are both important for training? DiffPhore is trained on two complementary, self-established datasets. LigPhoreSet contains over 840,000 ligand-pharmacophore pairs generated from energetically favorable ligand conformations, featuring perfect-matching pairs and broad chemical diversity, making it ideal for learning generalizable LPM patterns. CpxPhoreSet contains approximately 15,000 pairs derived from experimental protein-ligand complex structures, which often contain imperfect, "real-world" matches with an average fitness score of 0.967. Using both datasets—LigPhoreSet for initial warm-up training and CpxPhoreSet for subsequent refinement—enables the model to understand both ideal matching principles and the induced-fit effects present in actual binding environments [9] [36].

Q3: My DiffPhore virtual screening results contain poses with high fitness scores but chemically unrealistic geometries. How can I address this? This issue often relates to the sampling process. DiffPhore incorporates a calibrated conformation sampler specifically designed to mitigate the exposure bias inherent in iterative diffusion processes, which can lead to such artifacts. We recommend:

- Increasing the number of inference steps: Use the

--inference_stepsparameter (default is 20) to allow for a more refined, step-wise denoising process. - Adjusting the batch size and samples: Use the

--sample_per_complexparameter to generate multiple poses per pair and the--batch_sizeparameter to ensure stable computation. - Validating with the provided fitness scores: The output includes multiple fitness scores (DfScore1-5). Experiment with these different scoring metrics to rank poses, as DfScore1 is the default, while others may be more specific to tasks like target fishing [37].

Q4: Can DiffPhore be used for target fishing, and if so, how?

Yes, DiffPhore has demonstrated superior power in target fishing, which involves identifying potential protein targets for a given small molecule. The methodology involves screening a ligand's conformation against a library of pharmacophore models from different targets. You can perform this by using the --phore_ligand_csv option to specify a CSV file that pairs your ligand with multiple pharmacophore files. Using target fishing-specific fitness scores (e.g., via --fitness DfScore5 or --target_fishing True) during ranking helps prioritize poses most likely to interact with various biological targets [9] [37].

Q5: What specific pharmacophore feature types can DiffPhore handle? DiffPhore supports a comprehensive set of 10 pharmacophore feature types and exclusion spheres (EX) to represent steric constraints. The features are: Hydrogen-bond donor (HD), Hydrogen-bond acceptor (HA), Metal coordination (MB), Aromatic ring (AR), Positively-charged center (PO), Negatively-charged center (NE), Hydrophobic (HY), Covalent bond (CV), Cation-π interaction (CR), and Halogen bond (XB) [9] [36].

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Errors and Solutions

| Error Message / Issue | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| "Pharmacophore feature not recognized" during input processing | The pharmacophore file format is incorrect or contains unsupported feature types. | Ensure the pharmacophore file is generated by a supported tool like AncPhore. Verify the feature types against the list of 10 supported types [9] [37]. |

| Low fitness scores for known active ligands | The generated ligand conformations are not adequately mapping to the pharmacophore features. | Increase the --sample_per_complex value to generate more candidate conformations. Check the pharmacophore model's validity and ensure the ligand's chemical features are compatible. |

| Long runtimes during virtual screening of large libraries | The process is computationally intensive, especially with large batch sizes and multiple samples. | Adjust the --batch_size and --num_workers parameters based on your available CPU/GPU resources. For ultra-large libraries, consider a tiered screening approach. |

| Inconsistent results between consecutive runs | Stochastic nature of the diffusion sampling process. | Use a fixed random seed in the code for reproducibility. Increase the number of samples (--sample_per_complex) to achieve more statistically robust results. |

Performance Optimization Checklist

- Data Preprocessing: Ensure input ligands are in correct MOL/SDF format or as SMILES strings. For SMILES, 3D conformers are generated internally, but pre-generating reasonable 3D conformations can sometimes improve performance.

- Pharmacophore Model Quality: The accuracy of the input pharmacophore model is critical. Use a reliable tool like AncPhore for generation and visually inspect the model for logical feature placement.

- Parameter Tuning: For virtual screening, start with a lower