Beyond BERT: A Comparative Analysis of Sentence Transformers for DNA Sequence Representation in Cancer Genomics

The application of Sentence Transformer models to DNA sequence analysis presents a transformative opportunity in cancer genomics.

Beyond BERT: A Comparative Analysis of Sentence Transformers for DNA Sequence Representation in Cancer Genomics

Abstract

The application of Sentence Transformer models to DNA sequence analysis presents a transformative opportunity in cancer genomics. This article provides a comprehensive exploration for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, detailing how models like SBERT and SimCSE can be fine-tuned to generate powerful DNA embeddings for tasks ranging from cancer type classification to detection of regulatory elements. We cover the foundational principles of adapting natural language models to genomic 'language,' offer a methodological guide for implementation, address common challenges in tuning and optimization, and present a rigorous comparative analysis against domain-specific models like DNABERT and the Nucleotide Transformer. The findings indicate that fine-tuned Sentence Transformers offer a compelling balance of high performance and computational efficiency, making them particularly viable for resource-constrained environments while achieving accuracy critical for biomedical research and clinical applications.

From Natural Language to Genomic Code: The Foundational Principles of Sentence Transformers for DNA

Architectural Foundations and Evolution

Sentence Transformers represent a significant evolution in how machines process human language. Unlike traditional models that process words sequentially, transformer-based models can analyze entire sentences simultaneously, leading to a deeper understanding of context and meaning. This architectural shift has proven particularly valuable in specialized domains like genomics and cancer research [1].

The core innovation enabling Sentence Transformers is the self-attention mechanism, which allows the model to dynamically weigh the importance of each word in relation to all other words in a sentence. This mechanism is mathematically implemented through Query (Q), Key (K), and Value (V) vectors, which create a dynamic understanding of sentence context. Traditional word embedding methods like Word2Vec or GloVe typically involved averaging word vectors from a sentence, but failed to capture nuanced semantic relationships due to their inability to account for word order and contextual syntax [2] [1].

The Sentence-BERT (SBERT) model, introduced by Nils Reimers and Iryna Gurevych in 2019, specifically addresses limitations in the original BERT architecture for sentence-level tasks. While BERT creates contextually rich embeddings, it requires multiple passes for sentence-pair tasks, making it computationally expensive for similarity comparisons. SBERT modifies this architecture using siamese and triplet network structures during training, specifically optimized to produce semantically meaningful sentence embeddings where similar sentences are positioned closer in the vector space [2].

Core Mechanics: How Sentence Transformers Generate Embeddings

The fundamental operation of Sentence Transformers involves converting variable-length text into fixed-length dense vector representations (embeddings) in a high-dimensional space. These embeddings possess the crucial property that semantically similar sentences are mapped to nearby points, enabling mathematical operations on textual meaning [2].

The encoding process follows these computational stages:

Input Processing: The input sentence is tokenized into subword units compatible with the pre-trained transformer model.

Contextual Encoding: The transformer encoder processes all tokens simultaneously through multiple layers of self-attention and feed-forward networks. Each layer refines the representation by allowing tokens to interact globally across the sentence.

Pooling Operation: The token-level embeddings are aggregated into a fixed-size sentence embedding, typically using mean pooling, max pooling, or utilizing the [CLS] token representation.

Similarity Calculation: The cosine similarity between embeddings is computed to measure semantic relationship:

similarity = cos(θ) = (A·B)/(||A||·||B||)[2] [3].

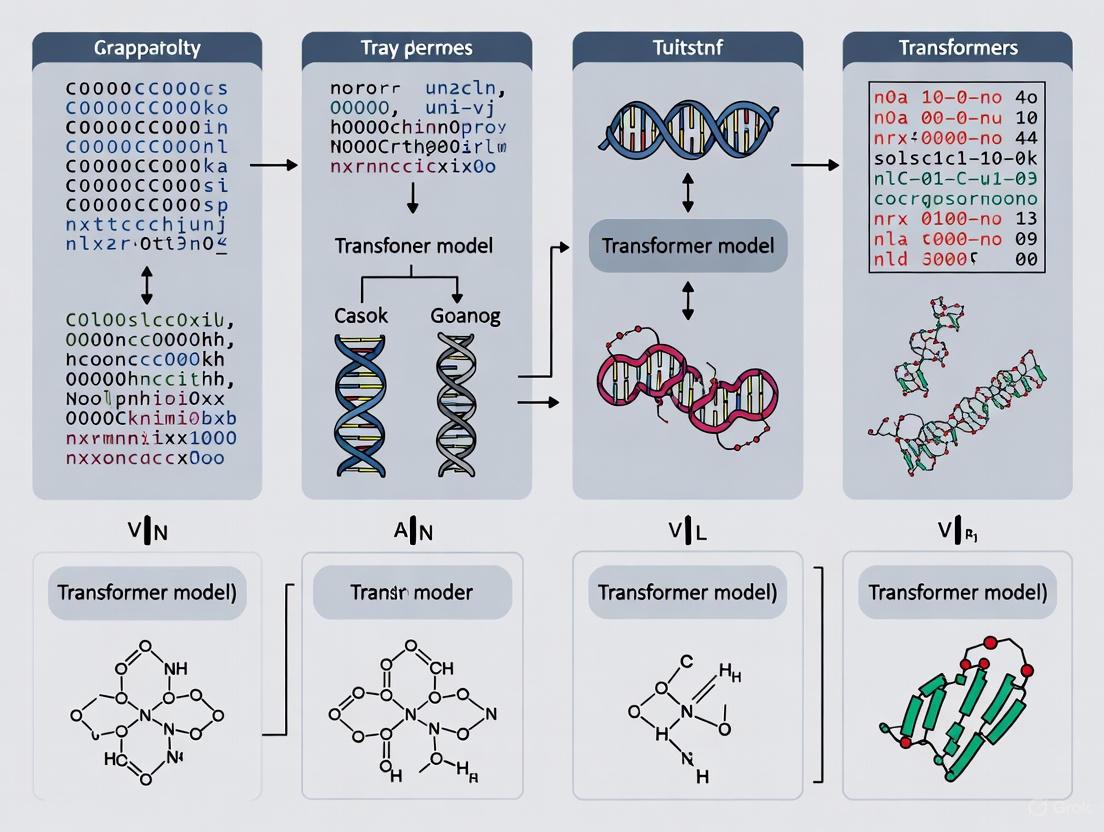

The following diagram illustrates this sentence encoding workflow:

Performance Comparison in Genomic Applications

Sentence Transformers fine-tuned for biological sequences demonstrate competitive performance against domain-specific models. Recent research has evaluated these models across multiple DNA sequence analysis tasks, with results summarized in the table below [4]:

| Model | Architecture | Training Data | Avg. Performance (MCC) | Computational Cost | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fine-tuned Sentence Transformer (SimCSE) | BERT-based, contrastive learning | 3,000 DNA sequences (6-mer tokens) | 0.705* | Low | Resource-constrained environments |

| DNABERT | Transformer, masked language modeling | Human reference genome | 0.682* | Medium | Genome annotation tasks |

| Nucleotide Transformer (500M) | Transformer, masked language modeling | 3,202 human genomes + 850 species | 0.723* | High | Maximum accuracy regardless of resources |

| BPNet (supervised baseline) | Convolutional Neural Network | Task-specific labeled data | 0.683 | Low | Task-specific applications |

Note: Performance metrics represent average Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) across multiple DNA classification tasks. MCC values range from -1 to 1, with higher values indicating better prediction accuracy [4] [5].

The fine-tuned Sentence Transformer approach demonstrates a favorable balance between performance and computational efficiency. While the Nucleotide Transformer achieves higher raw accuracy on some tasks, it requires substantially more computational resources, making it impractical for resource-constrained environments. The fine-tuned Sentence Transformer outperformed DNABERT across multiple benchmarks while maintaining lower computational requirements [4].

Experimental Protocols for DNA Sequence Analysis

Implementing Sentence Transformers for genomic analysis requires specific methodological adaptations. The following workflow outlines the fine-tuning process for DNA sequence representation [4]:

Key Experimental Steps:

DNA Sequence Preprocessing: Convert raw DNA sequences into tokens using k-mer segmentation (typically 6-mers). This approach breaks sequences into subsequences of length k, creating a vocabulary that the transformer can process.

Model Selection: Start with a pre-trained Sentence Transformer model like SimCSE, which uses contrastive learning to generate high-quality sentence embeddings.

Fine-tuning Protocol:

- Architecture: Employ siamese network structures with contrastive learning

- Training Data: 3,000 DNA sequences sufficient for effective adaptation

- Epochs: 1 epoch often provides substantial improvement

- Batch Size: 16 sequences balanced for stability and efficiency

- Sequence Length: Maximum of 312 tokens to handle typical genomic regions

Evaluation Framework: Assess embedding quality across 8 benchmark tasks including:

- Colorectal cancer case detection (APC and TP53 genes)

- Promoter region identification

- Transcription factor binding site prediction

- Enhancer element classification [4]

This methodology demonstrates that natural language-based transformers, when properly fine-tuned, can effectively capture biological semantics from DNA sequences despite their origin in textual processing.

Research Reagent Solutions for Genomic Sentence Transformer Applications

The following table details essential computational "reagents" required for implementing Sentence Transformers in genomic cancer research:

| Research Reagent | Specifications | Function in Experimental Pipeline |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-trained Sentence Transformer Model | SimCSE (BERT/RoBERTa base) or all-MiniLM-L6-v2 | Provides foundation for transfer learning, already understands linguistic patterns |

| Genomic Sequence Tokenizer | k-mer segmentation (k=6 recommended) | Converts DNA sequences into tokenized format compatible with transformer models |

| Fine-tuning Framework | Sentence Transformers library (Python) | Implements siamese networks and contrastive loss for domain adaptation |

| Genomic Benchmark Datasets | 8 classification tasks (e.g., APC, TP53 cancer genes) | Standardized evaluation of embedding quality for biological sequences |

| Embedding Similarity Metrics | Cosine similarity, Euclidean distance | Quantifies semantic relationship between DNA sequences in vector space |

| Domain-Specific Validation | Cross-validation on held-out cancer datasets | Ensures model robustness and generalizability across genomic contexts |

Advantages and Limitations in Cancer Research Applications

Sentence Transformers offer several distinct advantages for cancer genomics research. Their ability to capture semantic similarity enables researchers to find functionally related DNA sequences that may not have high sequence homology. This is particularly valuable for identifying regulatory elements with similar functions but divergent sequences. Additionally, the fixed-length embeddings generated by these models can be efficiently stored and queried, enabling rapid similarity search across large genomic databases [2] [4].

However, these approaches face significant limitations. Computational requirements for training and fine-tuning can be substantial, though less than domain-specific models like Nucleotide Transformer. There's also inherent domain shift when applying natural language models to biological sequences, though fine-tuning mitigates this concern. Performance in low-resource languages (or less-studied organisms) may be limited due to training data constraints, and models can potentially amplify biases present in training data [2] [4].

For cancer research specifically, fine-tuned Sentence Transformers show promise in tasks such as classifying cancer-related genetic variants, identifying regulatory elements involved in oncogenesis, and grouping functionally similar sequences across different cancer types. The comparative efficiency of these models makes them particularly suitable for research environments with limited computational resources, including clinical settings in developing regions [4] [6].

As transformer architectures continue to evolve, their application to genomic medicine represents a promising frontier in computational biology, potentially enabling more accurate diagnosis and personalized treatment strategies based on a deeper understanding of the language of DNA.

The analogy of DNA as a language, complete with a 4-letter alphabet (A, T, C, G), has evolved from a philosophical metaphor to a practical framework driving computational genomics research. This perspective has become increasingly relevant in cancer research, where precise interpretation of genomic "text" can reveal critical mutations driving oncogenesis. The foundational premise that DNA sequences exhibit core linguistic features—including redundancy and contextual meaning—has enabled researchers to apply sophisticated Natural Language Processing (NLP) methods to genomic data [7]. This approach is particularly valuable in oncology, where distinguishing meaningful mutations from background noise remains a fundamental challenge.

The application of transformer-based models, specifically designed to handle sequential data, has created new paradigms for analyzing DNA sequences in cancer contexts. These models treat DNA sequences as sentences to be interpreted, with k-mers (contiguous subsequences of length k) acting as words or tokens [4]. By leveraging this linguistic framework, researchers can identify patterns indicative of cancer drivers, predict functional consequences of non-coding variants, and potentially uncover novel therapeutic targets through large-scale genomic analysis.

Comparative Analysis of DNA Sequence Representation Models

Performance Benchmarking Across Genomic Tasks

Different approaches to DNA sequence representation yield varying results across benchmark tasks relevant to cancer research. The table below summarizes the performance of three prominent models across multiple genomic prediction tasks, measured by Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC), where higher values indicate better performance.

| Model | Model Size (Parameters) | Pre-training Data | Average MCC (18 tasks) | Splice Site Prediction | Promoter Prediction | Enhancer Prediction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleotide Transformer (Multispecies 2.5B) [5] | 2.5 billion | 850 species genomes | 0.683 (fine-tuned) | High | High | High |

| Nucleotide Transformer (Human ref 500M) [5] | 500 million | Human reference genome | 0.665 (fine-tuned) | Medium | Medium | Medium |

| DNABERT [4] | ~100 million | Human reference genome | Not fully reported | Medium | Medium | Medium |

| Fine-tuned Sentence Transformer (SimCSE) [4] | Not specified | 3000 DNA sequences | Competitive with DNABERT | Outperformed DNABERT on multiple tasks | Outperformed DNABERT on multiple tasks | Outperformed DNABERT on multiple tasks |

The Nucleotide Transformer (NT) models represent the current state-of-the-art, with the multispecies 2.5B parameter model achieving superior performance across most tasks [5]. However, the fine-tuned Sentence Transformer presents an interesting alternative, offering competitive performance with potentially lower computational requirements [4]. This balance is particularly relevant for resource-constrained environments, including research institutions in low- and middle-income countries.

Computational Efficiency and Resource Requirements

Beyond raw prediction accuracy, computational efficiency presents critical practical considerations for cancer research applications.

| Model | Training Resources | Inference Speed | Parameter Efficiency | Accessibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleotide Transformer [5] | Extensive (days/weeks on multiple GPUs) | Moderate to Slow | Lower (requires large models for best performance) | Limited without significant computational resources |

| DNABERT [4] | Significant (~25 days pretraining) [4] | Moderate | Medium | Moderate |

| Fine-tuned Sentence Transformer [4] | Moderate (1 epoch on limited data) | Fast | Higher (effective with fewer parameters) | High |

| LOGO (ALBERT-based) [4] | Efficient (significantly faster than DNABERT) | Fast | High (~1M parameters) | High |

The fine-tuned Sentence Transformer approach demonstrates that effective DNA sequence representations for cancer research need not always require massive parameter counts [4]. This model achieved competitive performance while being computationally efficient, highlighting the potential of transfer learning from general-language models to genomic domains.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Model Architecture and Training Specifications

Nucleotide Transformer Methodology

The Nucleotide Transformer models employ a standard transformer architecture with several genomic adaptations. The pretraining utilizes Masked Language Modeling (MLM) on 6-kb sequence chunks, where the model learns by predicting randomly masked nucleotides in sequences [5]. For downstream tasks in cancer research, two primary approaches are employed:

- Probing: Fixed embeddings from intermediate transformer layers are used as features for simple classifiers (logistic regression or small MLPs). This approach tests the intrinsic information captured during pretraining [5].

- Fine-tuning: The entire model (or subsets thereof) is further trained on specific tasks using parameter-efficient methods like adapters, which require only 0.1% of total parameters to be updated [5].

The multispecies model was pretrained on 850 diverse genomes, providing broad evolutionary context that improves performance on human genomic tasks, including those relevant to cancer variant interpretation [5].

Sentence Transformer Fine-tuning Protocol

The Sentence Transformer approach adapts existing language models to DNA sequences through a structured process:

- Sequence Tokenization: DNA sequences are split into k-mer tokens of size 6 (overlapping 6-base segments) [4].

- Model Adaptation: A pretrained SimCSE model (originally for natural language) is fine-tuned on 3000 DNA sequences [4].

- Training Configuration: The model is trained for 1 epoch with a batch size of 16 and maximum sequence length of 312 tokens [4].

- Embedding Generation: The fine-tuned model produces dense vector representations (embeddings) that capture semantic similarities between DNA sequences.

This approach leverages transfer learning from general language to genomic sequences, capitalizing on the structural similarities between natural language and DNA [4] [7].

Benchmarking Framework for Cancer Research Applications

Evaluation of these models utilizes standardized genomic tasks relevant to cancer mechanisms:

- Splice Site Prediction: Identifying exon-intron boundaries, crucial for understanding how mutations affect RNA processing in cancer [5].

- Promoter Prediction: Detecting transcription start sites, important for characterizing regulatory mutations in oncogenes and tumor suppressors [5].

- Enhancer Prediction: Locating regulatory elements that control gene expression patterns altered in cancer [5].

- Transcription Factor Binding Site Prediction: Identifying protein-DNA interactions disrupted in oncogenesis [4].

Models are evaluated using rigorous 5-fold or 10-fold cross-validation to ensure statistical reliability of performance estimates [4] [5]. Performance metrics include AUC-ROC, accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC), with MCC being particularly valuable for imbalanced genomic datasets [5].

Visualizing Model Architectures and Workflows

DNA Sentence Transformer Fine-tuning Workflow

Nucleotide Transformer Architecture Comparison

For researchers implementing DNA language models in cancer studies, the following resources and computational tools are essential:

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Datasets | Application in Cancer Research | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pretrained Models | Nucleotide Transformer (InstaDeepAI) [5] | Foundation for variant effect prediction | Multiple sizes (50M-2.5B parameters), multispecies training |

| DNABERT [4] | Promoter, enhancer, and splice site prediction | BERT architecture adapted for DNA, k-mer tokenization | |

| Sentence Transformers (fine-tuned) [4] | Efficient DNA sequence representation | Transfer learning from natural language, lower computational requirements | |

| Training Data | Human reference genome [5] | Baseline for human cancer genomics | Standard reference for mutation comparison |

| 1000 Genomes Project [5] | Population variant context | 3,202 diverse human genomes, population frequency data | |

| Multi-species genomes [5] | Evolutionary constraint analysis | 850 species for comparative genomics | |

| Evaluation Benchmarks | ENCODE datasets [5] | Regulatory element prediction | Histone modifications, chromatin accessibility in cancer cell lines |

| GENCODE annotations [5] | Splice site and gene structure evaluation | Comprehensive transcriptome annotation | |

| EPD promoter database [5] | Promoter usage in cancer | Eukaryotic Promoter Database for transcription start sites | |

| Implementation Libraries | Transformers (Hugging Face) [4] | Model deployment and fine-tuning | Standardized interface for transformer models |

| Sentence Transformers [4] | Semantic similarity computation | Efficient sentence embedding generation |

The conceptualization of DNA as a language with a 4-letter alphabet has matured from metaphor to practical methodology, enabling significant advances in cancer genomics. Our comparative analysis reveals that while large foundational models like the Nucleotide Transformer currently achieve state-of-the-art performance, efficient alternatives like fine-tuned Sentence Transformers offer compelling trade-offs for resource-constrained environments [4] [5].

The linguistic properties of DNA—particularly redundancy and contextual meaning—provide a powerful framework for interpreting genomic variants in cancer [7]. As these models continue to evolve, their ability to decipher the "grammar" of oncogenic mutations will potentially accelerate biomarker discovery, therapeutic target identification, and personalized cancer treatment strategies. The ongoing challenge remains balancing model complexity with interpretability, ensuring that predictions generated by these sophisticated systems can be validated biologically and translated clinically.

The field of genomics is increasingly leveraging advances in natural language processing (NLP), particularly transformer-based models, to decipher the complex "language" of DNA sequences. Sentence transformer models, specifically designed to generate meaningful sentence embeddings, have shown remarkable adaptability for genomic tasks. These models create dense vector representations where semantically similar texts are located close together in the embedding space, a property that translates well to DNA sequences where functional similarities often correlate with sequence patterns. Among these, SBERT (Sentence-BERT) and SimCSE (Simple Contrastive Learning of Sentence Embeddings) represent two influential approaches that have been adapted for genomic sequence analysis. Their application is particularly impactful in cancer research, where accurately interpreting DNA sequences can lead to better detection, understanding, and treatment of various malignancies.

The fundamental advantage of these models lies in their ability to create context-aware representations of nucleotide sequences, capturing biological semantics that traditional bioinformatics methods might miss. This capability is crucial for tasks such as identifying promoter regions, transcription factor binding sites, and distinguishing between healthy and cancerous sequences. As research progresses, these adapted sentence transformers are demonstrating competitive performance against specialized genomic models while offering computational efficiencies that make them accessible for resource-constrained environments.

Model Fundamentals and Technical Architecture

SBERT (Sentence-BERT)

SBERT is a modification of the standard BERT architecture that uses siamese and triplet network structures to derive semantically meaningful sentence embeddings. Unlike BERT, which requires both sentences to be processed together for similarity tasks, SBERT processes sentences independently, enabling efficient semantic similarity computation through cosine similarity between embeddings. This architectural innovation addresses BERT's computational inefficiency for semantic similarity tasks, where comparing 10,000 sentences would require approximately 49 million inference computations. For genomic applications, SBERT has been adapted to process DNA sequences instead of natural language sentences, typically by first converting sequences into k-mer tokens (overlapping subsequences of length k) that are treated analogously to words in a sentence.

SimCSE (Simple Contrastive Learning of Sentence Embeddings)

SimCSE employs contrastive learning to enhance sentence embedding quality through two distinct approaches. In unsupervised SimCSE, the model learns by predicting the input sentence itself using dropout as noise - the same input sentence is passed twice through the encoder with different dropout masks, producing positive embedding pairs, while other sentences in the same mini-batch serve as negative examples. The model is trained to maximize similarity between the positive pairs while minimizing similarity with negatives. For supervised SimCSE, natural language inference datasets provide explicit positive (entailment) and negative (contradiction) sentence pairs for contrastive learning. When adapted for genomics, DNA sequences replace natural language sentences, and the model learns to place functionally similar sequences closer in the embedding space while pushing dissimilar sequences apart.

Table: Core Technical Specifications of Sentence Transformer Models

| Model | Architecture Base | Learning Approach | Key Innovation | Genomic Adaptation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SBERT | BERT with siamese/triplet networks | Supervised fine-tuning | Enables efficient independent sentence encoding | DNA sequences tokenized into k-mers as model input |

| SimCSE | BERT/RoBERTa encoder | Contrastive learning (supervised & unsupervised) | Uses dropout as noise for positive pairs in unsupervised learning | DNA sequences used as inputs for contrastive learning |

DNA Adaptation Workflow

The process of adapting sentence transformers for genomic analysis follows a systematic workflow that transforms raw DNA sequences into meaningful numerical representations suitable for machine learning. The following diagram illustrates this process from sequence preparation to final embedding generation:

Methodological Approaches for Genomic Applications

DNA Sequence Preprocessing and Tokenization

Adapting sentence transformers for genomic analysis requires careful sequence preprocessing to convert raw DNA nucleotides into a format compatible with NLP models. The most common approach involves k-mer tokenization, where DNA sequences are broken down into overlapping subsequences of length k (typically 3-6 nucleotides). For example, a sequence "ATCGGA" with k=3 would become tokens: "ATC", "TCG", "CGG", "GGA". This approach effectively creates a "vocabulary" of k-mers that the transformer model can process similarly to words in natural language. Studies have shown that 6-mer tokens often provide an optimal balance between specificity and computational efficiency for many genomic tasks. After tokenization, these k-mers are fed into the sentence transformer models, which generate dense vector representations that capture functional and evolutionary patterns within the sequences.

Fine-tuning Strategies for Genomic Tasks

Fine-tuning sentence transformers for genomic applications follows two primary paradigms. In the unsupervised adaptation approach, models like SimCSE are further trained on large corpora of unlabeled DNA sequences using their inherent contrastive learning objectives. This helps the model learn general representations of genomic sequences without task-specific labels. For supervised fine-tuning, models are trained on labeled genomic datasets for specific prediction tasks such as promoter region identification, cancer classification, or exon-intron boundary detection. Research has demonstrated that even a single epoch of training on limited DNA sequence data (e.g., 3,000 sequences) can produce embeddings that effectively capture biologically relevant features for downstream tasks. Parameter-efficient fine-tuning techniques, which require as little as 0.1% of total model parameters, have proven particularly valuable given the computational demands of genomic sequences.

Experimental Benchmarking Methodologies

Rigorous evaluation of sentence transformers in genomic contexts typically involves cross-validation on curated benchmark datasets and comparison against domain-specific models. Standard evaluation protocols involve multiple genomic prediction tasks such as splice site identification, promoter detection, enhancer prediction, and cancer sequence classification. Performance is measured using metrics including accuracy, Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC), F1-score, and mean average precision (MAP). In these benchmarks, embeddings generated by sentence transformers are fed to simple classifiers (e.g., logistic regression, random forests, or small multilayer perceptrons) to assess their quality, or the entire model is fine-tuned for specific tasks. This approach allows for isolating the representation quality from the complexity of downstream models.

Performance Comparison with Domain-Specific Genomic Models

Benchmarking Against Specialized DNA Models

When compared to specialized genomic transformers like DNABERT and Nucleotide Transformer, adapted sentence transformers demonstrate a compelling balance between performance and computational efficiency. DNABERT, a BERT variant pretrained on the human reference genome using masked language modeling on k-mer tokens, has set strong benchmarks for tasks like promoter identification and transcription factor binding site prediction. The larger Nucleotide Transformer models (ranging from 500 million to 2.5 billion parameters) pretrained on diverse genomic datasets typically achieve higher raw accuracy but with substantially greater computational requirements. In direct comparisons, fine-tuned sentence transformers have been shown to outperform DNABERT on several tasks while approaching the performance of Nucleotide Transformer models at a fraction of the computational cost.

Table: Performance Comparison of DNA Sequence Models on Classification Tasks

| Model | Model Type | Pretraining Data | Accuracy Range | Computational Demand | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SBERT (adapted) | General-purpose sentence transformer | Natural language + DNA fine-tuning | 73-89%* | Low to moderate | Balanced performance, efficient inference |

| SimCSE (adapted) | General-purpose sentence transformer | Natural language + DNA fine-tuning | 75-88%* | Low to moderate | Strong contrastive learning, good embeddings |

| DNABERT | Domain-specific DNA transformer | Human reference genome | Varies by task | Moderate | DNA-specific optimization, interpretability |

| Nucleotide Transformer | Domain-specific DNA transformer | 3,202 human genomes + 850 species | Highest in benchmarks | Very high | State-of-the-art accuracy, extensive pretraining |

Note: Accuracy ranges shown for SBERT and SimCSE are based on reported results for specific tasks such as cancer detection [8] and exon-intron classification [9]. Performance varies significantly based on task complexity and dataset size.

Cancer Detection Performance

In practical cancer research applications, sentence transformers have demonstrated strong performance. A 2023 study applied SBERT and SimCSE to raw DNA sequences of matched tumor/normal pairs for colorectal cancer detection. The models generated sequence embeddings that were subsequently classified using machine learning algorithms including XGBoost, Random Forest, and LightGBM. The results showed that XGBoost achieved 73% accuracy with SBERT embeddings and 75% accuracy with SimCSE embeddings, demonstrating that SimCSE's contrastive learning approach provided marginally superior representations for this critical cancer detection task. This performance is particularly notable given that the models relied solely on raw DNA sequences without additional clinical or phenotypic data.

Another study focusing on exon and intron region classification for BCR-ABL and MEFV genes achieved 88.88% accuracy using a hybrid approach combining SBERT embeddings with Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System (ANFIS). In this methodology, DNA sequences were clustered using SBERT pretrained models with K-Means and Agglomerative Clustering, followed by frequency calculations of 64 different codons that constitute genetic code. This demonstrates how sentence transformers can be effectively integrated into larger bioinformatics pipelines for precise genomic region identification.

Computational Efficiency Considerations

Beyond raw accuracy, computational efficiency is a crucial factor in practical genomic applications, particularly in resource-constrained environments. Specialized genomic models like the Nucleotide Transformer with 2.5 billion parameters require substantial computational resources for both training and inference. In contrast, adapted sentence transformers typically have smaller footprints (e.g., SBERT and SimCSE models often range from 100-400 million parameters) while maintaining competitive performance. This efficiency advantage extends to embedding extraction time, where sentence transformers often demonstrate faster processing compared to bulkier domain-specific models. The reduced computational demand makes these adapted models particularly valuable for rapid prototyping and deployment in settings with limited computational resources.

Implementation Toolkit for Genomic Research

Successful implementation of sentence transformers for genomic analysis requires both computational resources and biological data components. The following table outlines the key "research reagents" and their functions in adapting these models for DNA sequence analysis:

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Genomic Sentence Transformer Implementation

| Component | Type | Function | Example Sources/Implementations |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Sequences | Biological Data | Raw genetic material for analysis | NCBI, Ensemble databases [9] |

| k-mer Tokenizer | Computational Tool | Segments DNA into model-compatible units | Custom Python implementations |

| Pretrained Sentence Transformers | Model Architecture | Base model for sequence embedding | SBERT, SimCSE from sbert.net [10] [11] |

| Genomic Benchmarks | Evaluation Datasets | Standardized tasks for model validation | Promoter detection, splice site prediction, cancer classification [8] [4] |

| Sequence Embedding Libraries | Computational Tool | Generation and management of DNA embeddings | Sentence Transformers Python library [11] |

Implementation Workflow for Cancer Genomics

Implementing sentence transformers for cancer genomics follows a structured pipeline that transforms raw sequences into actionable insights. The following diagram outlines the key stages from data collection to clinical insights:

Applications in Cancer Research and Genomics

The adaptation of sentence transformers for genomic analysis has enabled significant advances in multiple domains of cancer research. In cancer detection and classification, models like SBERT and SimCSE have been successfully applied to distinguish between cancerous and healthy sequences using only raw DNA inputs, providing a valuable approach for early diagnosis. For regulatory element discovery, these models help identify promoter regions, enhancers, and transcription factor binding sites that are frequently dysregulated in cancer, contributing to our understanding of oncogenic mechanisms.

In variant interpretation, sentence transformers can assess the functional impact of genetic mutations by comparing embedding similarities between reference and mutated sequences, helping prioritize clinically significant variants in cancer genomes. Additionally, these models have shown utility in cancer subtype stratification by clustering tumor sequences based on their embedding similarities, potentially revealing molecular subtypes with distinct clinical behaviors and treatment responses.

The representation learning capabilities of sentence transformers also facilitate multi-omics integration, where DNA sequence embeddings can be combined with transcriptomic, epigenetic, and proteomic data to build more comprehensive models of cancer biology. This integrated approach is particularly valuable for understanding complex cancer phenotypes and identifying novel therapeutic targets.

Sentence transformers like SBERT and SimCSE represent powerful tools for genomic analysis, particularly in cancer research where interpreting DNA sequence semantics is crucial. While specialized genomic models like Nucleotide Transformer may achieve marginally higher accuracy on some benchmarks, adapted sentence transformers offer an excellent balance of performance, computational efficiency, and implementation simplicity. The demonstrated success of these models in tasks ranging from cancer detection to functional element identification highlights their versatility and biological relevance.

Future developments will likely focus on multimodal architectures that combine sequence understanding with structural and functional genomic data, as well as transfer learning approaches that leverage models pretrained on massive genomic datasets. As the field advances, the integration of these transformer approaches with emerging single-cell and spatial genomics technologies will further enhance our ability to decipher the complex language of cancer genomics, ultimately leading to improved diagnostics and therapeutics.

In the burgeoning field of genomic artificial intelligence, DNA language models (DLMs) are revolutionizing how researchers interpret the vast complexity of genetic sequences. Similar to natural language processing (NLP), where text is broken down into interpretable units, DLMs require effective strategies to convert raw DNA sequences (comprising nucleotides A, C, G, T) into discrete tokens that machine learning models can process. Tokenization serves as the critical first step in this pipeline, fundamentally shaping the model's ability to capture biological semantics, syntax, and long-range dependencies within genomic data. Within cancer research, where precise sequence interpretation can reveal mutations, regulatory elements, and disease mechanisms, the choice of tokenization strategy directly impacts model performance in tasks such as classifying tumor/normal pairs or predicting pathogenic variants. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of the dominant K-mer tokenization strategy against emerging alternatives, evaluating their performance characteristics, computational trade-offs, and suitability for different research applications in genomics and drug development.

Understanding Tokenization Strategies for DNA Sequences

K-mer Tokenization: The Established Approach

K-mer tokenization is a widely adopted method for processing DNA sequences. It involves splitting a sequence into overlapping substrings of a fixed length, k. For example, the sequence "ATGGCT" can be tokenized into 3-mers as ["ATG," "TGG," "GGC," "GCT"] or into 5-mers as ["ATGGC," "TGGCT"] [12]. This approach effectively captures local sequential structures and short-range patterns within the DNA, making it biologically intuitive for recognizing motifs like transcription factor binding sites. Models such as DNABERT and Nucleotide Transformer (NT) have successfully employed this method [12].

However, traditional K-mer tokenization faces several significant challenges. It often results in a large vocabulary size (all possible 4^k permutations), which can lead to uneven token distribution and a rare word problem where infrequent K-mers provide insufficient training signal [12]. Furthermore, because the model primarily processes these fixed-length segments, its ability to understand broader sequence context and long-range genomic interactions is limited. The overlapping nature of K-mers, while preserving local context, also increases computational and memory demands due to longer tokenized sequence lengths [12].

Alternative Tokenization Methods

Byte Pair Encoding (BPE)

Byte Pair Encoding (BPE), successfully implemented in DNABERT2 and GROVER, addresses several K-mer limitations [12]. Originally a compression algorithm adapted for NLP, BPE starts with individual nucleotides and iteratively merges the most frequent adjacent pairs to form new vocabulary tokens. This data-driven approach creates a variable-length vocabulary that reflects actual sequence statistics, effectively mitigating the rare token problem by decomposing uncommon patterns into more frequent sub-units [12]. BPE demonstrates superior efficiency in capturing global contextual information and produces more balanced token distributions, though it may sometimes prioritize frequency over biologically meaningful units.

Hybrid Tokenization Approaches

Recent innovations have combined the strengths of multiple methods. A notable hybrid tokenization strategy merges unique 6-mer tokens with optimally selected BPE tokens generated through 600 BPE cycles (BPE-600) [12]. This approach aims to balance the local structural preservation of K-mers with the contextual flexibility of BPE, creating a more robust vocabulary that captures both short and long-range genomic patterns [12]. Experimental results indicate that models trained on this hybrid vocabulary achieve superior performance on next-K-mer prediction tasks compared to those using either method alone [12].

Single-Nucleotide and Other Methods

HyenaDNA processes sequences at the single-nucleotide level (1-mers), using the standard DNA bases (A, G, C, T) and N for unknown bases [12]. This method avoids predefined token combinations entirely, relying on the model's architecture to learn relevant patterns from the most fundamental units. While this approach offers maximal resolution and avoids vocabulary biases, it requires sophisticated model architectures to capture meaningful genomic features that naturally occur over multiple nucleotides. Other specialized methods include VQDNA, which uses a convolutional encoder with a vector-quantized codebook to learn optimal token representations directly from data [12].

Table 1: Comparative Overview of DNA Tokenization Strategies

| Tokenization Method | Mechanism | Vocabulary Characteristics | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| K-mer | Splits sequence into overlapping substrings of fixed length k | Fixed size (4^k); can be large and imbalanced | Captures local structure; biologically intuitive for motifs | Limited global context; rare token problems |

| Byte Pair Encoding (BPE) | Iteratively merges most frequent nucleotide pairs | Variable size; data-driven and balanced | Addresses rare token issue; captures broader context | May overlook biologically meaningful K-mer units |

| Hybrid (K-mer + BPE) | Combines unique K-mers with frequent BPE tokens | Balanced; preserves both local and global patterns | Improved performance on various tasks | Increased implementation complexity |

| Single-Nucleotide | Treats each nucleotide as separate token | Minimal (4-5 tokens); uniform distribution | Maximum resolution; simple vocabulary | Requires advanced architecture for pattern recognition |

Comparative Performance Analysis

Experimental Framework and Benchmarking

Objective evaluation of tokenization strategies requires standardized tasks that reflect real-world genomic analysis challenges. A primary benchmark is next-K-mer prediction, where a model is fine-tuned to predict subsequent K-mers in a sequence, testing its understanding of genomic syntax and contextual relationships [12]. This task directly measures how effectively a tokenization scheme preserves sequential dependencies crucial for understanding regulatory logic and sequence evolution.

For cancer research applications, classification performance on matched tumor/normal pairs provides particularly relevant metrics. Studies applying sentence transformers like SBERT and SimCSE to generate DNA sequence representations have achieved accuracies of 73-75% in cancer detection tasks using raw DNA sequences, with XGBoost classifiers built on these embeddings demonstrating the effectiveness of the underlying representations [8]. Additional functional benchmarks include promoter identification, protein-DNA binding prediction, and enhancer-gene linking evaluated against CRISPR screening data, which test the biological relevance of the learned representations beyond statistical metrics [13].

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Models Using Different Tokenization Strategies

| Model | Tokenization Strategy | Next-K-mer Prediction Accuracy | Cancer Classification | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Foundation DLM (Hybrid) | Hybrid (6-mer + BPE-600) | 3-mer: 10.78%4-mer: 10.1%5-mer: 4.12% | Not Reported | Foundation model for downstream genomic tasks |

| GROVER | BPE-600 | Lower than hybrid approach [12] | Not Reported | Promoter identification, protein-DNA binding |

| DNABERT2 | BPE | Not Reported | Not Reported | General-purpose genome modeling |

| Nucleotide Transformer | K-mer | Lower than hybrid approach [12] | Not Reported | Large-scale genomic pre-training |

| SBERT + XGBoost | Not Specified | Not Applicable | 73 ± 0.13% | Cancer detection from raw DNA sequences |

| SimCSE + XGBoost | Not Specified | Not Applicable | 75 ± 0.12% | Cancer detection from raw DNA sequences |

The experimental data reveals that the hybrid tokenization approach (combining 6-mer and BPE-600 tokens) achieves superior performance on next-K-mer prediction tasks, outperforming established models like NT, DNABERT2, and GROVER that use single-method tokenization [12]. This performance advantage demonstrates that balanced vocabularies preserving both local sequence structure and global contextual information enhance model capabilities.

In applied cancer research contexts, transformer-based embeddings (SBERT and SimCSE) paired with traditional classifiers have shown promising results, with SimCSE embeddings providing a marginal but consistent performance improvement [8]. This suggests that advanced representation learning methods can effectively capture biologically relevant features from DNA sequences for discrimination tasks.

Implementation Guide

Workflow for DNA Sequence Tokenization and Modeling

The process of converting raw DNA sequences into model inputs involves multiple stages with critical decision points that influence downstream performance. The following workflow diagram illustrates a standardized pipeline for DNA tokenization and model training, particularly relevant for cancer research applications:

Table 3: Essential Resources for Implementing DNA Tokenization and Modeling

| Resource Category | Specific Tools & Reagents | Function in Research | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tokenization Libraries | DNABERT2 tokenizer, Hugging Face Tokenizers, BioTokenizer | Convert raw DNA sequences to token IDs | BPE implementations available in DNABERT2; K-mer functions in NT codebase |

| Genomic Datasets | 1000 Genomes Project, TCGA cancer genomes, ENCODE CRISPR screens [13] | Provide training data and benchmarking standards | CRISPR enhancer screens particularly valuable for validation [13] |

| Model Architectures | BERT, GPT, HyenaDNA, XGBoost, Random Forest | Learn sequence representations and make predictions | Transformers for context; ensemble methods for classification [8] |

| Evaluation Frameworks | Next-K-mer prediction tasks, CRISPR benchmark workflows [13], sklearn metrics | Quantify model performance on biological tasks | Use multiple metrics for comprehensive evaluation |

| Sequence Representations | SBERT, SimCSE embeddings, K-mer frequency vectors | Create numerical features from tokenized sequences | Sentence transformers show promise for DNA [8] |

The comparative analysis reveals that no single tokenization strategy dominates all scenarios, underscoring the importance of selection aligned with specific research objectives. For investigations prioritizing local motif discovery—such as identifying transcription factor binding sites or characterizing short conserved domains—traditional K-mer tokenization (k=4-6) remains a principled choice due to its direct alignment with biological units of function. However, for projects requiring understanding of long-range genomic interactions—including enhancer-promoter communication or chromatin domain characterization—BPE or hybrid approaches offer superior contextual awareness.

In clinical and translational research settings, particularly cancer detection and classification, hybrid tokenization methods or transformer-based embeddings (SBERT, SimCSE) paired with robust classifiers like XGBoost have demonstrated compelling performance [8]. The marginal superiority of SimCSE over SBERT in cancer classification tasks suggests that contemporary representation learning techniques can capture biologically meaningful features from DNA sequences when appropriately adapted [8].

As genomic language models continue to evolve, the integration of tokenization strategies with emerging architectures—such as HyenaDNA's long-context capabilities or Caduceus's reverse complementarity equivariance—will likely yield further advances. Researchers should consider establishing modular tokenization pipelines that permit strategy ablation studies during model development, ensuring that this foundational preprocessing step receives appropriate optimization alongside model architecture and training methodology.

The application of transformer-based models to genomic sequences has revolutionized the ability to decode the complex regulatory language of DNA, a pursuit of paramount importance in cancer research. Foundation models, pre-trained on vast unlabeled genomic datasets, provide powerful sequence representations that can be fine-tuned for specific predictive tasks with limited labeled data. Among these, several architectural approaches have emerged: dedicated DNA-specific models like DNABERT, Nucleotide Transformer, and HyenaDNA, and an alternative approach that involves adapting sentence transformers from natural language processing (NLP) for genomic use. Understanding the comparative performance, computational requirements, and optimal use cases for each model is essential for researchers aiming to predict oncogenic drivers, regulatory elements, and therapeutic targets. This guide provides an objective comparison of these approaches, focusing on their mechanistic differences, benchmark performance, and practical implementation for genomic discovery.

Model Architectures and Technical Foundations

The DNA foundation models discussed herein share a common goal—learning informative representations of DNA sequences—but diverge significantly in their architectural choices, tokenization strategies, and training objectives.

DNA-Specific Foundation Models

DNABERT leverages the classic BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers) architecture, pre-trained using a masked language modeling (MLM) objective on the human reference genome [14] [15]. Its key innovation lies in tokenizing DNA sequences into k-mers (contiguous subsequences of length k, typically 3-6), which are then processed by the transformer to capture nucleotide context [4] [15]. DNABERT-2, an enhanced version, incorporates Attention with Linear Biases (ALiBi) and uses Byte Pair Encoding (BPE) for more efficient tokenization, and is pre-trained on genomes from 135 species [16].

Nucleotide Transformer (NT) also employs a BERT-style architecture but is distinguished by its massive scale and training data diversity [5]. Models range from 50 million to 2.5 billion parameters and are pre-trained on datasets including the human reference genome, 3,202 diverse human genomes, and 850 genomes from various species [16] [5]. NT uses 6-mer tokenization and replaces learned positional embeddings with rotary embeddings, reducing computational cost [16]. Its primary pre-training objective is also masked language modeling [5].

HyenaDNA represents a architectural departure by eschewing the attention mechanism in favor of a decoder-based design centered on Hyena operators [17] [18]. These operators integrate long convolutions with implicit parameterization and data-controlled gating, enabling sub-quadratic scaling with sequence length [16] [17]. This allows HyenaDNA to process sequences of up to 1 million tokens at single-nucleotide resolution (a vocabulary of just 4 characters: A, C, G, T), a dramatic increase over previous models [17] [18]. It is pre-trained on the human reference genome using a next-nucleotide prediction task [17].

The Sentence Transformer Approach

Instead of a model designed specifically for DNA, this approach involves fine-tuning a sentence transformer model originally developed for natural language on DNA sequences [4]. The specific model used in the identified study was SimCSE, which utilizes contrastive learning to generate high-quality sentence embeddings [4]. The model is adapted to DNA by fine-tuning it on DNA sequences split into 6-mer tokens, teaching it to generate semantically useful embeddings for genomic regions [4]. The hypothesis is that a general-purpose representation model, when sufficiently adapted, can compete with or even outperform domain-specific models [4].

The diagram below illustrates the fundamental workflow for adapting a sentence transformer for DNA, contrasting it with the pre-training process of dedicated DNA models.

Experimental Protocols and Benchmarking Methodologies

Objective comparison of these models requires standardized evaluation across diverse genomic tasks. The following section details the experimental designs and key metrics used in comparative studies.

Fine-Tuning a Sentence Transformer for DNA

A direct comparative study fine-tuned the SimCSE sentence transformer model on 3,000 DNA sequences for 1 epoch [4]. The DNA sequences were tokenized into 6-mers. The model was then evaluated by generating sentence embeddings for eight classification tasks and comparing its performance against DNABERT-6 and the Nucleotide Transformer (500M parameter version) [4].

Zero-Shot Embedding Benchmark

An independent large-scale benchmarking study evaluated model performance based on the inherent quality of their zero-shot embeddings (the last hidden states of the pre-trained models, without fine-tuning) [16]. This approach eliminates biases introduced by different fine-tuning procedures. The study employed a supervised learning approach with efficient tree-based models on 57 datasets across tasks like regulatory element prediction and epigenetic modification detection [16]. A key finding was that using mean token embeddings consistently outperformed the default sentence-level summary token embedding for all models [16].

Task-Specific Fine-Tuning and Probing

The Nucleotide Transformer study established a rigorous benchmark of 18 genomic datasets, including splice site prediction, promoter identification, and enhancer tasks [5]. Models were evaluated via:

- Probing: Using frozen model embeddings as input features for simple classifiers (e.g., logistic regression).

- Fine-tuning: Using parameter-efficient methods to update a small subset (0.1%) of model parameters for the specific task, which was found to be faster and more robust than probing [5].

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below catalogues the essential computational tools and resources required for working with these DNA foundation models.

Table 1: Key Research Reagents for DNA Foundation Models

| Reagent / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Accessibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNABERT / DNABERT-2 [14] [15] | Pre-trained Model | Sequence classification, motif discovery, variant effect prediction | GitHub, Hugging Face |

| Nucleotide Transformer [5] | Pre-trained Model | Multi-species sequence understanding, phenotype prediction | Hugging Face |

| HyenaDNA [17] [18] | Pre-trained Model | Ultra-long sequence analysis, in-context learning | GitHub, Hugging Face |

| Sentence Transformers (e.g., SimCSE) [4] | NLP Library & Models | Generating sentence-level embeddings, adaptable to DNA | Python Package |

| GenomicBenchmarks [17] | Dataset Collection | Standardized tasks for model evaluation (e.g., enhancer prediction) | GitHub |

| Hugging Face Transformers [18] [15] | Python Library | Provides unified interface to load and use pre-trained models | Python Package |

Performance Comparison Across Genomic Tasks

Synthesizing results from multiple benchmarks reveals a nuanced performance landscape where the optimal model choice is heavily dependent on the specific task, available computational resources, and data constraints.

The following table consolidates quantitative performance data from the cited studies.

Table 2: Comparative Model Performance on Genomic Tasks

| Model | Architecture & Scale | Representative Performance Findings | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fine-tuned Sentence Transformer (SimCSE) | Adapted NLP model (exact size not specified) | Exceeded DNABERT performance on multiple tasks; did not surpass NT in raw classification accuracy [4]. | Balances performance and computational cost; viable for resource-constrained environments [4]. |

| DNABERT-2 | BERT-based (~117M parameters) | Most consistent performance across human genome-related tasks in zero-shot benchmark [16]. | Proven accuracy on human regulatory tasks; more parameter-efficient than larger models [16]. |

| Nucleotide Transformer (NT) | BERT-based (500M - 2.5B parameters) | Excelled in epigenetic modification detection [16]; matched or surpassed supervised baseline in 12/18 tasks after fine-tuning [5]. | High raw accuracy, especially on classification; benefits from multi-species training [16] [5]. |

| HyenaDNA | Hyena operator-based (~30M parameters) | Set new SotA on 23 downstream tasks; superior on long-range context tasks [17]. | Unparalleled context length (1M tokens); single-nucleotide resolution; fast inference [16] [17]. |

Computational Efficiency and Resource Requirements

Beyond raw accuracy, practical deployment in research settings depends heavily on computational cost.

- HyenaDNA is notable for its runtime efficiency and ability to handle extremely long sequences with a relatively small number of parameters (e.g., 30M), making it accessible for academic labs [16] [17].

- The Nucleotide Transformer, especially its billion-parameter versions, incurs "significant computing expenses, rendering it impractical for resource-constrained environments" [4].

- The fine-tuned Sentence Transformer was positioned as a middle-ground option, offering a favorable balance between performance and accuracy without the extreme computational demands of the largest models [4].

- DNABERT-2 provides a robust balance, offering strong performance without the massive parameter count of the largest NT models [16].

Implications for Cancer Research

The unique strengths of each model can be leveraged to address different challenges in oncology.

- Fine-tuned Sentence Transformers offer a compelling, computationally efficient path for labs with strong NLP expertise to quickly apply existing infrastructure to genomic data, particularly for tasks like classifying coding vs. non-coding regions or predicting promoter status in candidate oncogenes [4].

- DNABERT and Nucleotide Transformer are well-suited for detailed analysis of regulatory elements (promoters, enhancers) and variant effect prediction, tasks central to understanding non-coding driver mutations and personalizing cancer risk [14] [5].

- HyenaDNA opens new possibilities for analyzing long-range genomic interactions, such as the effect of structural variations, distant enhancer-promoter looping in gene dysregulation, and the integration of multi-modal data across large genomic loci [17] [18]. Its in-context learning capability also suggests potential for few-shot learning on rare cancer subtypes with limited data [17].

The following workflow outlines a potential strategy for integrating these models into a cancer genomics research pipeline.

The landscape of DNA foundation models offers multiple paths for cancer researchers. DNA-specific models like DNABERT-2 and Nucleotide Transformer provide robust, high-performance tools for a wide array of classification tasks, with the latter achieving top-tier accuracy at a higher computational cost. HyenaDNA breaks new ground with its ability to process ultralong sequences at single-nucleotide resolution, enabling the study of long-range interactions previously out of reach. Interestingly, the adaptation of general-purpose sentence transformers presents a viable and efficient alternative, demonstrating that fine-tuned natural language models can compete with, and in some settings surpass, the performance of dedicated genomic models. The choice of model should therefore be guided by the specific biological question, the scale of the sequences involved, and the computational resources available to the research team.

A Practical Guide to Implementing Sentence Transformers for Cancer Genomics Tasks

The application of sentence transformer models to DNA sequence data represents a paradigm shift in computational genomics, particularly for cancer research. These models generate dense numerical representations (embeddings) that capture complex biological semantics, enabling more accurate prediction of molecular phenotypes from raw genomic data. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of embedding approaches—from general-purpose sentence transformers to specialized DNA models—framed within a practical pipeline that progresses from FASTA file processing to the generation of fine-tuned embeddings for cancer detection applications.

The Complete Embedding Generation Workflow

The transformation of raw DNA sequences into actionable embeddings follows a systematic, multi-stage pipeline. The workflow below illustrates the complete process from data acquisition through to model evaluation in cancer research applications.

Comparative Analysis of DNA Embedding Approaches

Different embedding strategies offer distinct trade-offs between computational efficiency, biological accuracy, and specialization for genomic tasks. The table below summarizes the performance characteristics of prominent approaches when applied to DNA sequence data.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Embedding Approaches for DNA Sequences

| Model Category | Representative Models | Key Strengths | DNA-Specific Limitations | Reported Accuracy in Cancer Tasks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Sentence Transformers | SBERT, SimCSE | Effective transfer learning, good performance with limited labeled data [4] [19] | Not optimized for nucleotide patterns | 73-75% (XGBoost classifier) [19] |

| DNA-Specific Foundation Models | Nucleotide Transformer, DNABERT | State-of-the-art on genomic tasks, context-aware representations [4] [5] | Computationally intensive, requires significant resources [4] | Matches/exceeds supervised baselines in 12/18 tasks [5] |

| Protein Language Models | Microsoft Dayhoff Embeddings | Captures evolutionary relationships, useful for protein sequences [20] | Limited direct application to raw DNA | High-quality novel protein generation [20] |

| Optimized Production Models | Quantized BGE variants | Fast inference, CPU-compatible, efficient for large-scale deployment [21] | Potential minor accuracy trade-offs (<1.5%) [21] | Not specifically reported for DNA tasks |

Experimental Protocols for Embedding Evaluation

Benchmarking Methodology for DNA Sequence Classification

Robust evaluation protocols are essential for comparing embedding performance across different DNA analysis tasks. The following workflow details the standard methodology employed in comparative studies.

The standardized evaluation framework employs two primary techniques for assessing embedding quality:

Probing Analysis: Fixed embeddings from pre-trained models are used as input features to simple classifiers (logistic regression or small MLPs) to evaluate the intrinsic information captured during pre-training [5].

Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning: Only 0.1% of model parameters are updated during task adaptation, significantly reducing computational requirements while maintaining performance competitive with full fine-tuning [5].

Cancer Detection Experimental Protocol

For cancer-specific applications, studies typically employ the following methodology:

- Input Data: Raw DNA sequences from matched tumor/normal pairs, particularly for colorectal cancer [19]

- Embedding Generation: Sequences are processed using sentence transformers (SBERT, SimCSE) to produce fixed-dimensional representations

- Classification: Embeddings are fed into machine learning classifiers (XGBoost, Random Forest, CNN) for binary classification of cancer status

- Evaluation: Performance assessed via accuracy, precision, and recall metrics with cross-validation

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Components for DNA Embedding Pipelines

Table 2: Essential Tools and Resources for DNA Embedding Implementation

| Tool/Resource | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| FASTA File Parser | Processes raw DNA sequences from standard genomic files | Biopython's SeqIO module [22] |

| k-mer Tokenizer | Splits DNA sequences into overlapping subsequences for transformer input | 6-mer tokenization with 312 max length [4] |

| Transformer Backbone | Base architecture for generating sequence embeddings | BERT, RoBERTa, or custom DNA transformer architectures [4] [5] |

| Embedding Extraction | Generates fixed-dimensional vectors from model outputs | [CLS] token representation or mean pooling of hidden states [21] |

| Evaluation Framework | Standardized benchmarking of embedding quality | MTEB-inspired protocols with domain-specific adaptations [5] [23] |

| Optimization Libraries | Accelerates inference on CPU/GPU hardware | Optimum Intel, IPEX for quantization and performance optimization [21] |

Performance Optimization Strategies

Deploying embedding models in production research environments requires careful attention to computational efficiency:

Quantization Techniques: Post-training static quantization reduces model precision from 32-bit to 8-bit integers with minimal accuracy impact (typically <1.5% performance degradation) while significantly improving inference speed [21].

Hardware Acceleration: Leveraging Intel Advanced Matrix Extensions (AMX) on Xeon CPUs can substantially boost throughput for embedding generation, particularly important for large-scale genomic datasets [21].

The choice of embedding strategy depends critically on research constraints and objectives. For resource-constrained environments or preliminary investigations, fine-tuned general sentence transformers (SimCSE, SBERT) offer compelling performance with minimal computational investment. For state-of-the-art results on specialized genomic tasks, DNA-specific foundation models (Nucleotide Transformer) deliver superior accuracy at the cost of significant computational resources. Protein-focused applications benefit from evolutionary-aware embeddings like Microsoft Dayhoff, while production systems requiring high throughput may prioritize optimized variants of efficient models like quantized BGE. As the field advances, the integration of these embedding approaches into standardized bioinformatics pipelines will increasingly empower cancer researchers to extract deeper insights from genomic sequence data.

The application of natural language processing (NLP) techniques to genomic sequences represents a paradigm shift in computational biology, particularly for cancer research. Sentence transformer models, originally developed for semantic textual similarity tasks in natural language, are now being adapted to decode the complex "language" of DNA. These models generate dense numerical representations (embeddings) for DNA sequences that capture functional and structural properties essential for distinguishing cancer-related genomic alterations. Within this emerging field, SimCSE (Simple Contrastive Learning of Sentence Embeddings) has emerged as a particularly powerful framework for creating high-quality sentence embeddings through contrastive learning objectives [24]. When fine-tuned on DNA sequences, SimCSE generates semantically meaningful embeddings that place functionally similar DNA sequences closer together in the embedding space, enabling more accurate cancer classification, promoter region identification, and transcription factor binding site prediction [4] [25]. This comparative guide examines the performance of fine-tuned SimCSE against other DNA-specialized transformer models, providing researchers with experimental data and methodologies for implementing these approaches in cancer genomics workflows.

Performance Comparison: SimCSE vs. Domain-Specific DNA Transformers

Quantitative Performance Across Benchmark Tasks

Table 1: Accuracy Comparison Across DNA Classification Tasks

| Model | Embedding Method | T1: APC Gene | T3: Enhancer Sites | T5: Splice Sites | T8: TP53 Gene |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SimCSE-DNA (Proposed) | Pooler Output | 0.65 ± 0.01 | 0.85 ± 0.01 | 0.80 ± 0.0 | 0.70 ± 0.01 |

| DNABERT-6 | [CLS] Token | 0.62 ± 0.01 | 0.84 ± 0.04 | 0.85 ± 0.01 | 0.60 ± 0.01 |

| Nucleotide Transformer (500M) | Contextual | 0.66 ± 0.0 | 0.84 ± 0.01 | 0.85 ± 0.01 | 0.99 ± 0.0 |

Note: Performance measured using Logistic Regression classifier; values represent mean accuracy ± 95% confidence intervals across 8 benchmark tasks (T1-T8). Complete results available in [26].

Table 2: F1-Score Comparison for Cancer Detection Tasks

| Model | Embedding Method | T1: APC Gene | T3: Enhancer Sites | T5: Splice Sites | T8: TP53 Gene |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SimCSE-DNA (Proposed) | Pooler Output | 0.78 ± 0.0 | 0.20 ± 0.05 | 0.79 ± 0.0 | 0.70 ± 0.01 |

| DNABERT-6 | [CLS] Token | 0.75 ± 0.01 | 0.47 ± 0.09 | 0.84 ± 0.01 | 0.59 ± 0.01 |

| Nucleotide Transformer (500M) | Contextual | 0.56 ± 0.01 | 0.78 ± 0.01 | 0.85 ± 0.01 | 0.99 ± 0.0 |

Note: F1-scores (with 95% confidence intervals) demonstrate variable performance across tasks depending on the embedding method and classifier combination. Complete results available in [26].

Computational Efficiency and Resource Requirements

Table 3: Computational Requirements and Efficiency Metrics

| Model | Parameters | Pretraining Data | Inference Speed | Resource Demands |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SimCSE-DNA | ~110M | 3,000 DNA sequences (6-mer tokenized) | Fast | Suitable for resource-constrained environments |

| DNABERT-6 | ~100M | Human reference genome | Moderate | Medium resource requirements |

| Nucleotide Transformer | 500M-2.5B | Human reference genome + 850 species | Slow | Significant computing expenses |

Note: SimCSE-DNA achieves a favorable balance between performance and computational efficiency, making it particularly suitable for low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) with limited computational resources [4].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

SimCSE Fine-Tuning Protocol for DNA Sequences

The fine-tuning process for adapting SimCSE to DNA sequences involves several critical steps that transform raw DNA sequences into semantically meaningful embeddings optimized for cancer research applications:

Step 1: DNA Sequence Preprocessing and K-mer Tokenization

- Input DNA sequences are segmented into overlapping k-mers of size 6 (6 consecutive nucleotides)

- This tokenization approach converts continuous DNA sequences into discrete tokens that resemble words in natural language

- For example, the DNA sequence "ATCGTA" would become tokens: "ATCGTAC", "TCGTACG", "CGTACGT" etc.

- The k-mer size of 6 was determined empirically to balance contextual information and computational efficiency [4]

Step 2: Contrastive Learning Framework Implementation

- The unsupervised SimCSE approach uses dropout as minimal data augmentation

- Each input DNA sequence is passed twice through the transformer encoder with different dropout masks

- The resulting embeddings (positive pairs: z, zⁱ) are trained to be similar while embeddings from other sequences in the same mini-batch serve as negative examples

- The model learns to predict the positive pair among the negative examples using contrastive loss [24]

- For supervised SimCSE, entailment pairs from Natural Language Inference (NLI) datasets serve as positives while contradiction pairs serve as hard negatives [27]

Step 3: Fine-Tuning Parameters and Training Regimen

- The model was trained for 1 epoch using a batch size of 16

- Maximum sequence length was set to 312 tokens

- Learning rate was optimized for DNA sequence characteristics

- Training was performed on 3,000 DNA sequences from the human reference genome

- The original SimCSE checkpoint ("princeton-nlp/sup-simcse-bert-base-uncased") was used as the starting point [4]

Step 4: Embedding Extraction and Downstream Application

- After fine-tuning, sentence embeddings are generated for DNA sequences

- The [CLS] token representation or mean pooling of all token representations can be used

- These embeddings serve as input to traditional machine learning classifiers (XGBoost, Random Forest, etc.) for cancer detection tasks [25]

Comparative Model Training Protocols

DNABERT Implementation:

- DNABERT employs Masked Language Modeling (MLM) objective similar to BERT

- Pretrained on the human reference genome using fixed k-mer sizes (3, 4, 5, or 6)

- Comprises 12 transformer layers and 12 attention heads

- Evaluated on promoter prediction, enhancer identification, and splice site detection [4]

Nucleotide Transformer Implementation:

- Uses Masked Language Modeling (MLM) to predict masked nucleotides represented as 6-mer tokens

- Available in multiple parameter sizes (500 million, 2.5 billion parameters)

- Pretrained on diverse datasets including human reference genome, 3202 diverse human genomes, and 850 genomes across species

- For this comparison, the "InstaDeepAI/nucleotide-transformer-500m-human-ref" variant was used [4]

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials for Implementation

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Resource | Type | Function | Availability |

|---|---|---|---|

| SimCSE-DNA Model | Pre-trained Model | Generate DNA sequence embeddings | Hugging Face: "dsfsi/simcse-dna" [26] |

| DNABERT | Pre-trained Model | Domain-specific DNA embeddings | Original implementation [4] |

| Nucleotide Transformer | Pre-trained Model | Large-scale genomic embeddings | Hugging Face: "InstaDeepAI/nucleotide-transformer-500m-human-ref" [4] |

| Human Reference Genome | Dataset | Pretraining and fine-tuning data | Public genomic databases |

| 3,000 DNA Sequences | Fine-tuning Dataset | Adapt SimCSE to DNA domain | Custom dataset from human reference genome [4] |

| CRC Tumor/Normal Pairs | Evaluation Dataset | Cancer detection benchmarking | Controlled access repositories [25] |

Workflow Visualization: SimCSE for DNA Sequence Analysis

Diagram 1: SimCSE-DNA Fine-Tuning and Classification Workflow - This diagram illustrates the complete pipeline from raw DNA sequences to cancer predictions, highlighting the key stages of k-mer tokenization, contrastive learning, and classification.

Diagram 2: Model Selection Trade-offs - This diagram visualizes the performance-efficiency trade-offs between different DNA transformer models, highlighting SimCSE's balanced approach compared to more specialized alternatives.

Based on the comprehensive performance analysis and experimental protocols detailed in this guide, SimCSE fine-tuned on DNA sequences presents a compelling option for cancer research applications, particularly when balancing predictive accuracy with computational efficiency. The model demonstrates competitive performance across multiple genomic tasks while maintaining significantly lower resource requirements compared to larger domain-specific transformers like the Nucleotide Transformer. For research teams with limited computational resources or those working in screening applications where speed is critical, SimCSE-DNA offers a practical solution without substantial performance sacrifices. For maximum accuracy in well-resourced environments, the Nucleotide Transformer remains superior, while DNABERT provides a middle ground for projects requiring domain specialization without extreme computational demands. The fine-tuning protocols and reagent specifications provided herein enable research teams to implement these approaches effectively in diverse cancer genomics workflows.

Pan-Cancer Classification (e.g., BRCA, LUAD, COAD) using Generated Embeddings

The application of sentence transformers to generate embeddings from DNA sequences represents a paradigm shift in computational oncology. By converting nucleotide sequences into numerical vectors that capture semantic and functional similarities, these models enable powerful downstream analysis of complex genomic data. This guide provides a comparative analysis of transformer-based embedding techniques for pan-cancer classification, focusing on their performance in distinguishing cancer types such as Breast Invasive Carcinoma (BRCA), Lung Adenocarcinoma (LUAD), and Colon Adenocarcinoma (COAD). We evaluate specialized DNA models against fine-tuned natural language transformers, examining their accuracy, computational efficiency, and practical applicability for researchers and clinicians.

Comparative Performance of DNA Embedding Methods

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Table 1: Performance comparison of embedding methods for DNA sequence classification tasks.

| Embedding Method | Architecture | Classification Accuracy | Computational Requirements | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fine-tuned SimCSE (DNA) | Sentence Transformer | 75 ± 0.12% (XGBoost) [25] | Moderate | Balance of performance and efficiency |

| DNABERT | BERT-based | Outperformed by SimCSE on multiple tasks [4] | High | Domain-specific pretraining |

| Nucleotide Transformer | Transformer (500M params) | Highest raw accuracy [4] | Very High | State-of-the-art performance |

| SBERT (DNA) | Sentence Transformer | 73 ± 0.13% (XGBoost) [25] | Moderate | Slightly lower than SimCSE |

Task-Specific Performance Insights