Best Practices for Pharmacophore Model Validation: A Comprehensive Guide for Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive guide to pharmacophore model validation, a critical step in ensuring the predictive power and reliability of computer-aided drug design.

Best Practices for Pharmacophore Model Validation: A Comprehensive Guide for Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to pharmacophore model validation, a critical step in ensuring the predictive power and reliability of computer-aided drug design. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles of validation, explores established and emerging methodological protocols, offers troubleshooting strategies for common pitfalls, and details rigorous statistical and comparative evaluation techniques. By synthesizing current best practices, this guide aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to build robust, predictive pharmacophore models that can successfully accelerate lead identification and optimization.

The Pillars of Confidence: Understanding the Why and How of Pharmacophore Validation

Validation is a critical, multi-faceted process that ascertains the predictive capability, applicability, and overall robustness of any in-silico pharmacophore model [1]. Moving beyond mere model generation to establishing predictive assurance ensures that computational hypotheses translate into reliable tools for drug discovery, ultimately guiding the efficient identification of novel therapeutic candidates. This document outlines established protocols and application notes for a comprehensive validation strategy, providing researchers with a structured framework to evaluate and confidence in their pharmacophore models.

Core Validation Methodologies: Protocols and Application

A robust validation strategy integrates multiple complementary approaches. The following sections detail key experimental protocols.

Internal Validation and Test Set Prediction

Principle: Internal validation assesses the model's self-consistency and predictive power on the training data, while test set validation evaluates its ability to generalize to new, unseen compounds [1].

Protocol:

- LOO Cross-Validation: For a training set of

ncompounds, sequentially remove one compound, rebuild the model with the remainingn-1compounds, and predict the activity of the removed compound [1]. - Calculate LOO Metrics:

- Test Set Validation:

Equations:

- Equation 1 (Q²):

Q² = 1 - [Σ(Y - Yₚᵣₑd)² / Σ(Y - Ȳ)²]WhereYis the observed activity,Yₚᵣₑdis the predicted activity, andȲis the mean activity of the training set [1]. - Equation 2 (RMSE):

RMSE = √[ Σ(Y - Yₚᵣₑd)² / n ][1] - Equation 3 (R²ₚᵣₑd):

R²ₚᵣₑd = 1 - [Σ(Y₍ₜₑₛₜ₎ - Yₚᵣₑd₍ₜₑₛₜ₎)² / Σ(Y₍ₜₑₛₜ₎ - Ȳₜᵣₐᵢₙᵢₙg)²][1]

Statistical Significance Tests

Principle: These tests evaluate whether the model captured a meaningful structure-activity relationship or a mere chance correlation.

2.2.1 Cost Function Analysis Protocol:

- During model generation (e.g., in Hypogen algorithms), analyze the cost values [1].

- Compare the total hypothesis cost to the cost of the null hypothesis (a model with no features) [1].

- A difference (Δ) between the null cost and the total cost of > 60 bits indicates a model with a >90% statistical significance, not due to chance [1].

- Ensure the configuration cost is < 17, which signifies a model of acceptable complexity [1].

2.2.2 Fischer's Randomization Test Protocol:

- Randomly shuffle the biological activity data associated with the training set molecules, while keeping the structures unchanged [1].

- Generate new pharmacophore models using these randomized datasets.

- Repeat this process numerous times (e.g., 100-1000 iterations) to create a distribution of correlation coefficients from random chance.

- Calculate the statistical significance by comparing the original model's correlation coefficient to the distribution from randomized datasets. A significance level of p < 0.05 (original correlation greater than 95% of random models) confirms the model's relevance [1].

Decoy Set Validation and Güner-Henry (GH) Method

Principle: This method evaluates the model's ability to discriminate between truly active molecules and inactive decoys in a virtual screening scenario [1] [2] [3].

Protocol:

- Decoy Set Generation: Use tools like the DUD-E database generator to create a set of decoy molecules. Decoys should be physically similar to active compounds (in molecular weight, logP, etc.) but chemically distinct to avoid bias [1].

- Database Screening: Screen the combined database of known actives and decoys using the pharmacophore model as a query.

- Categorize Results: Based on the screening hits, categorize compounds into:

- Ha: Retrieved hits that are active (True Positives, TP)

- Ht: Total number of hits retrieved

- A: Total number of active compounds in the database

- D: Total number of compounds in the database

- Calculate GH Metrics: Use the following metrics to assess the model's quality [1] [3]:

- %Yield of Actives:

(Ha / Ht) * 100 - %Ratio of Actives:

(Ha / A) * 100 - Enrichment Factor (EF):

(Ha / Ht) / (A / D) - GH Score: A composite score calculated from the above values.

- %Yield of Actives:

Quantitative Data and Metrics for Validation

The table below summarizes key statistical parameters and their recommended thresholds for a validated model.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Metrics for Pharmacophore Model Validation

| Metric | Category | Description | Acceptable Threshold | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q² | Internal Validation | Cross-validation coefficient from LOO | > 0.5 | [1] |

| R²ₚᵣₑd | External Validation | Predictive correlation for test set | > 0.5 | [1] |

| Δ Cost | Statistical Significance | Difference from null hypothesis cost | > 60 | [1] |

| Configuration Cost | Statistical Significance | Model complexity metric | < 17 | [1] |

| EF (1%) | Decoy Set/ROC | Early enrichment factor | ≥ 10 (at 1% threshold) | [2] |

| AUC | Decoy Set/ROC | Area Under the ROC Curve | ≥ 0.9 (Excellent) | [2] |

A critical consideration is that no single metric is sufficient. For instance, a high R² value alone cannot indicate the validity of a model [4]. A combination of internal, external, and statistical assessments is mandatory for predictive assurance.

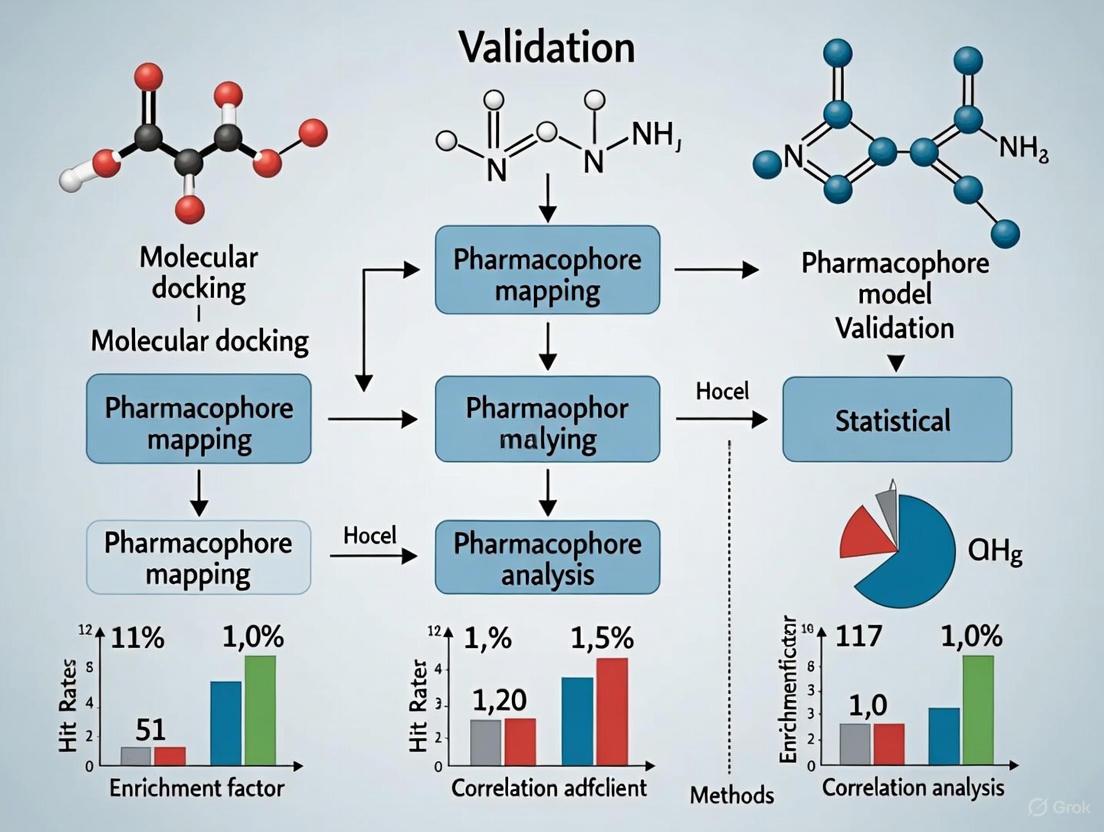

Experimental Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow integrating the various validation methodologies discussed above.

Successful pharmacophore modeling and validation rely on a suite of software tools, databases, and computational resources.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Pharmacophore Validation

| Item / Resource | Type | Function in Validation | Example / Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| LigandScout | Software | Used for structure-based and ligand-based pharmacophore generation, model optimization, and decoy set screening [5] [2]. | Inte:Ligand |

| Discovery Studio (DS) | Software | Provides protocols for Ligand Pharmacophore Mapping and validation using the Güner-Henry method [3]. | BIOVIA |

| DUD-E Database | Online Tool | Generates property-matched decoy molecules for rigorous validation of virtual screening performance [1]. | https://dude.docking.org/ |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Database | Source of 3D macromolecular structures for structure-based pharmacophore modeling and complex analysis [6] [5]. | https://www.rcsb.org/ |

| ZINC/ChEMBL | Database | Curated collections of commercially available compounds and bioactivity data for test set creation and reference [7] [2]. | Publicly Accessible |

| PHASE/Hypogen | Software Algorithm | Implements specific quantitative pharmacophore modeling and validation algorithms, including cost analysis [7]. | Schrödinger / BioVia |

| CATS Descriptors | Computational Method | Chemically Advanced Template Search descriptors used to quantify pharmacophore similarity between molecules [8]. | Integrated in various tools |

Within modern computational drug discovery, the validation of pharmacophore and Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models is paramount. This application note delineates the core statistical metrics—R²pred for external predictive power, RMSE for error magnitude, and Q² for internal robustness via Leave-One-Out (LOO) cross-validation. Framed within best practices for pharmacophore model validation, this document provides researchers and drug development professionals with explicit protocols for calculating and interpreting these metrics, ensuring model reliability, regulatory compliance, and informed decision-making for lead optimization.

The journey from a chemical structure to a predictive computational model hinges on rigorous validation. Without it, models risk being statistical artifacts, incapable of generalizing to new, unseen compounds. Validation provides the critical foundation for trust in model predictions, especially when these predictions influence costly synthetic efforts or regulatory decisions [9] [10].

The OECD principles for QSAR validation underscore the necessity of defining a model's applicability domain and establishing goodness-of-fit, robustness, and predictive power [11]. This document focuses on the quantitative metrics that operationalize these principles. While traditional metrics like the internal Q² and external R²pred are widely used, recent research advocates for supplementary, more stringent parameters like rm² and Rp² to provide a stricter test of model acceptability, particularly in regulatory contexts [9]. This note integrates both traditional and novel metrics to present a comprehensive validation protocol.

Defining the Core Statistical Metrics

R²pred (Predictive R²) for External Validation

Purpose: R²pred is the cornerstone metric for evaluating a model's predictive ability on an external test set of compounds that were not used in model construction [9] [1].

Mathematical Definition:

The formula for R²pred is given by:

R²pred = 1 - [Σ(Y_observed(test) - Y_predicted(test))² / Σ(Y_observed(test) - Ȳ(training))²] [1].

Here, Y_observed(test) and Y_predicted(test) are the observed and predicted activities of the test set compounds, respectively, and Ȳ(training) is the mean observed activity of the training set compounds.

Interpretation and Acceptance Criterion:

- An R²pred value greater than 0.5 is generally considered to indicate an acceptable and robust model [1].

- A significant advantage of R²pred is that it is independent of the training set's activity range, providing a pure measure of external predictivity [9].

RMSE (Root Mean Square Error)

Purpose: RMSE quantifies the average magnitude of the prediction errors in the units of the biological activity, providing an intuitive measure of model accuracy [1].

Mathematical Definition:

RMSE = √[ Σ(Y_observed - Y_predicted)² / n ] [1].

Here, n is the number of compounds. RMSE can be calculated for both the training set (RMSEtr) to assess goodness-of-fit and for the test set (RMSEtest) to assess predictive accuracy.

Interpretation:

- A lower RMSE indicates a more accurate model. There is no universal threshold, as it is highly dependent on the activity range and units. It is most valuable when comparing different models applied to the same dataset.

Q² (LOO Cross-Validated R²) for Internal Validation

Purpose: Q², derived from Leave-One-Out (LOO) cross-validation, assesses the internal robustness and predictive ability of a model within its training set [9] [1].

Methodology: In LOO, one compound is removed from the training set, the model is rebuilt with the remaining compounds, and the activity of the removed compound is predicted. This process is repeated for every compound in the training set.

Mathematical Definition:

Q² = 1 - [ Σ(Y_observed(tr) - Y_LOO_predicted(tr))² / Σ(Y_observed(tr) - Ȳ(training))² ] [1].

Interpretation and Acceptance Criterion:

- A Q² > 0.5 is typically considered the threshold for a robust model [12].

- It is crucial to note that a high Q² is a necessary but not sufficient condition for a predictive model; a high Q² does not always guarantee high external predictivity (R²pred) [9].

Table 1: Summary of Core Validation Metrics

| Metric | Validation Type | Formula | Interpretation & Acceptance |

|---|---|---|---|

| R²pred | External | 1 - [Σ(Y_obs(test) - Y_pred(test))² / Σ(Y_obs(test) - Ȳ_train)²] |

> 0.5 indicates acceptable external predictive ability [1]. |

| RMSE | Internal/External | √[ Σ(Y_obs - Y_pred)² / n ] |

Lower values indicate higher accuracy; no universal threshold. |

| Q² (LOO) | Internal | 1 - [ Σ(Y_obs(tr) - Y_LOO(tr))² / Σ(Y_obs(tr) - Ȳ_train)² ] |

> 0.5 indicates model robustness [12]. |

Advanced and Supplementary Validation Metrics

While R²pred and Q² are fundamental, relying on them alone can be insufficient. Stricter, novel parameters have been proposed to mitigate the risk of accepting flawed models.

The rm² Metrics: A Stricter Measure

Purpose: The rm² parameter provides a more rigorous assessment by penalizing models for large differences between observed and predicted values [9].

Variants and Calculation:

- rm²(LOO): Applied to the training set using LOO-predicted values.

- rm²(test): Applied to the external test set predictions.

- rm²(overall): A consolidated metric that uses LOO-predicted values for the training set and predicted values for the test set, providing a comprehensive view based on a larger number of compounds [9].

This metric is considered a better and more stringent indicator of predictability than R²pred or Q² alone [9].

Rp² and Randomization Test

Purpose: The Rp² metric is used in conjunction with Y-randomization (Fischer's randomization test) to ensure the model is not the result of a chance correlation [9] [1].

Methodology: The biological activity data is randomly shuffled, and new models are built using the original descriptors. This process is repeated multiple times to generate a distribution of correlation coefficients (Rr) for random models.

Calculation: Rp² penalizes the model's original squared correlation coefficient (R²) for the difference between R² and the squared mean correlation coefficient (Rr²) of the randomized models [9].

A model is considered statistically significant if the original correlation coefficient lies outside the distribution of correlation coefficients from the randomized datasets, confirming the model captures a true structure-activity relationship [1].

Experimental Protocols for Metric Calculation

Protocol 1: Standard External Validation with R²pred and RMSE

Objective: To evaluate the predictive power of a developed QSAR/pharmacophore model on an independent test set.

Materials:

- A validated QSAR/pharmacophore model.

- A curated dataset of compounds with known biological activities, split into training and test sets.

Procedure:

- Data Splitting: Randomly split the full dataset into a training set (typically 70-85%) and a test set (15-30%). Ensure both sets cover a similar range of structural diversity and biological activity [13].

- Model Training: Develop the final model using only the compounds in the training set.

- Prediction: Use the finalized model to predict the biological activities of the compounds in the test set.

- Calculation:

- Calculate R²pred using the formula in Section 2.1.

- Calculate RMSE for the test set (RMSEtest) using the formula in Section 2.2.

- Interpretation: A model with R²pred > 0.5 and a low RMSEtest relative to the activity range is considered externally predictive.

Protocol 2: Internal Validation via LOO Cross-Validation for Q²

Objective: To assess the internal robustness and predictive reliability of a model within its training set.

Materials:

- A training set of compounds with known biological activities.

Procedure:

- Model Development: Develop a model using the entire training set (Model A).

- Iterative Prediction:

- Remove one compound from the training set.

- Rebuild the model using the remaining N-1 compounds.

- Predict the activity of the removed compound.

- Return the removed compound to the training set and repeat the process for every compound in the set.

- Calculation: After all iterations, you will have a LOO-predicted value for every training set compound. Calculate Q² using the formula in Section 2.3.

- Interpretation: A Q² > 0.5 indicates the model is internally robust and stable.

Objective: To perform a stringent, consolidated validation using both internal and external predictions.

Materials:

- A QSAR model, its training set, and an external test set.

Procedure:

- Generate Predictions:

- Obtain LOO-predicted values for the training set compounds (from Protocol 2).

- Obtain predicted values for the external test set compounds (from Protocol 1).

- Combine Data: Create a combined dataset of observed vs. predicted values, where predictions for the training set are LOO-based and for the test set are from the final model.

- Calculation: Calculate the rm²(overall) statistic based on this combined dataset [9].

- Interpretation: This metric provides a single, rigorous measure of model predictivity that is less reliant on a potentially small test set and helps in model selection when traditional parameters are comparable.

The following workflow diagrams the integration of these validation protocols into a coherent model development process:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Software

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Model Validation

| Item/Software | Function/Description | Example Use in Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Cerius2, DRAGON | Software for calculating molecular descriptors (topological, structural, physicochemical) [9] [14]. | Generates independent variables for QSAR model development. |

| Schrödinger Suite | Integrated software for drug discovery, including LigandScout (pharmacophore) and Phase (3D-QSAR) [15] [16]. | Used for pharmacophore generation, model building, and performing LOO validation. |

| V-Life MDS | A software platform for molecular modeling and QSAR studies [17]. | Calculates 2D and 3D molecular descriptors and builds QSAR models with internal validation. |

| Decoy Set (from DUD-E) | A database of physically similar but chemically distinct inactive molecules used for validation [1] [15]. | Validates the pharmacophore model's ability to distinguish active from inactive compounds (enrichment assessment). |

| Test Set Compounds | A carefully selected, independent set of compounds not used in model training. | Serves as the benchmark for calculating R²pred and RMSEtest for external validation [1]. |

A robust validation strategy is non-negotiable for any pharmacophore or QSAR model intended for reliable application in drug discovery. While the classical triumvirate of Q², R²pred, and RMSE provides a foundational assessment, researchers are strongly encouraged to adopt a more comprehensive approach. Incorporating stringent metrics like rm² and Rp² offers a deeper, more reliable evaluation of model performance, aligning with the best practices for regulatory acceptance and effective lead optimization as outlined in this note. A model that successfully passes this multi-faceted validation protocol provides a trustworthy foundation for virtual screening and the rational design of novel therapeutic agents.

In the rigorous field of computer-aided drug design, the predictive power of a pharmacophore model is paramount. A pharmacophore model abstractly represents the ensemble of steric and electronic features necessary for a molecule to interact with a biological target and elicit a response [6]. However, not all generated models are created equal; some may fit the training data by mere chance rather than capturing a true underlying structure-activity relationship. Cost function analysis provides a critical, quantitative framework to ascertain the robustness and statistical significance of a pharmacophore hypothesis [1]. It is a cornerstone of model validation, ensuring that the model possesses genuine predictive capability and is not a product of overfitting or random correlation. Within this analytical framework, two specific cost parameters—the null hypothesis cost and the configuration cost—serve as fundamental indicators of model quality and reliability. This application note details the interpretation of these costs and provides a validated protocol for their use within pharmacophore model validation workflows.

Deciphering Cost Function Components

The total cost of a pharmacophore hypothesis is a composite value calculated during the model generation process, such as by the HypoGen algorithm [18]. It integrates several cost components, each providing unique insight into the model's quality. A comprehensive breakdown of these components is provided in the table below.

Table 1: Key Components of Pharmacophore Cost Function Analysis

| Cost Component | Description | Interpretation & Ideal Value |

|---|---|---|

| Total Cost | The overall cost of the developed pharmacophore hypothesis. | Should be as low as possible. |

| Fixed Cost | The ideal cost of a hypothetical "perfect" model that fits all data perfectly [19]. | A theoretical lower bound. The total cost should be close to this value. |

| Null Hypothesis Cost | The cost of a model that assumes no relationship between features and activity (i.e., the mean activity of all training set compounds is used for prediction) [1] [19]. | A baseline for comparison. A large difference from the total cost indicates a significant model. |

| Configuration Cost | A fixed cost that depends on the complexity of the hypothesis space, influenced by the number of features in the model [1]. | Should generally be < 17 [1]. A higher value suggests an overly complex model. |

| Weight Cost | Penalizes models where the feature weights deviate from the ideal value [1]. | Lower values indicate a more ideal configuration. |

| Error Cost | Represents the discrepancy between the predicted and experimentally observed activities of the training set compounds [1]. | A major driver of the total cost; lower values indicate better predictive accuracy. |

Interpreting the Null Hypothesis Cost and ΔCost

The null hypothesis cost represents the starting point of the analysis, calculating the cost of a model that has no correlation with biological activity [19]. The most critical metric derived from this is the ΔCost (cost difference), calculated as: ΔCost = Null Cost - Total Cost [19].

The ΔCost value is a direct indicator of the statistical significance of the pharmacophore model. A larger ΔCost signifies that the developed hypothesis is far from a random chance correlation. As established in validated protocols, a ΔCost of more than 60 implies that the hypothesis does not merely reflect a chance correlation and has a greater than 90% probability of representing a true correlation [1] [19]. Models with a ΔCost below this threshold should be treated with caution.

Understanding Configuration Cost

The configuration cost is a fixed value that increases with the complexity of the hypothesis space, which is directly related to the number of features used in the pharmacophore model [1]. It represents a penalty for model complexity, discouraging the creation of overly specific models that may not generalize well.

A configuration cost below 17 is considered satisfactory for a robust pharmacophore model [1]. A high configuration cost suggests that the model is too complex and may be over-fitted to the training set, reducing its utility for predicting the activity of new, diverse compounds. Therefore, the goal is to find a model with a high ΔCost while maintaining a low configuration cost.

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between these key cost components and the decision process for model acceptance.

Experimental Protocol for Cost Analysis in Model Validation

This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology for performing cost function analysis during the generation and validation of a 3D QSAR pharmacophore model, using software such as Accelrys Discovery Studio's HypoGen.

Materials and Software Requirements

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Pharmacophore Modeling & Cost Analysis

| Item Name | Function / Description | Example Tools / Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Dataset | A curated set of compounds with known biological activities (e.g., IC50, Ki) and diverse chemical structures. | ChEMBL, PubChem BioAssay [7] |

| Molecular Modeling Suite | Software for compound sketching, 3D structure generation, energy minimization, and conformational analysis. | ChemSketch, ChemBioOffice [20] [18] |

| Pharmacophore Modeling Software | Platform capable of generating 3D QSAR pharmacophore hypotheses and performing cost function analysis. | Accelrys Discovery Studio (HypoGen) [19] [18], Catalyst (Hypogen) [7], LigandScout [21] |

| Conformation Generation Algorithm | Generates a representative set of low-energy 3D conformers for each compound in the dataset. | Poling Algorithm, CHARMm force field [22] [18] |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Training Set Preparation

- Select a set of compounds (typically 15-25 molecules) with known biological activities spanning a wide range (e.g., 4-5 orders of magnitude) [18].

- Sketch the 2D structures of the training set compounds and convert them into 3D models.

- Generate multiple low-energy conformations for each compound to represent its flexibility. A common setting is a maximum of 255 conformations within an energy threshold of 20 kcal/mol above the global minimum [20] [18].

Pharmacophore Generation and Cost Calculation

- Input the training set conformations and their experimental activity values into the pharmacophore generation module (e.g., HypoGen).

- Run the hypothesis generation process. The algorithm will typically output the top 10 ranked models.

- From the results, extract the following cost values for each hypothesis: Total Cost, Fixed Cost, Null Cost, and Configuration Cost.

Cost Analysis and Model Selection

- For each hypothesis, calculate the ΔCost (Null Cost - Total Cost).

- Apply the significance criteria:

- The model with the highest ΔCost and a low Configuration Cost should be selected as the best, statistically significant pharmacophore hypothesis.

Validation and Integration with Other Methods

While cost function analysis is a powerful internal validation tool, a comprehensive validation strategy for a pharmacophore model requires its integration with other methods.

- Test Set Prediction: Use an external test set of compounds (not used in training) to evaluate the model's predictive power. Calculate metrics like the predictive correlation coefficient (R²pred) and root-mean-square error (RMSE). An R²pred greater than 0.50 is often considered acceptable [1].

- Fischer Randomization Test: This test assesses the risk of chance correlation. The activities of the training set are randomly shuffled, and new models are generated from this scrambled data. The original model's cost should be significantly lower than the costs from hundreds of randomized iterations, confirming its statistical significance [1] [20] [18].

- Decoy Set Validation: Evaluate the model's ability to discriminate active compounds from inactive ones (decoys) in a database. Metrics like the Enrichment Factor (EF) and Goodness of Hit Score (GH) are used, where a GH score above 0.7 indicates a very good model [1] [20].

Application Notes and Troubleshooting

- Low ΔCost (< 60): This indicates a model that is likely not statistically significant. To address this, re-examine the training set for diversity and a sufficient spread of activity values. Ensure conformational sampling is adequate.

- High Configuration Cost (≥ 17): This suggests an overly complex model. Try generating models with a smaller number of pharmacophoric features.

- Holistic Evaluation: Always interpret cost values in conjunction with other statistical parameters (like correlation coefficient) and validation results from test sets and Fischer randomization. A model with excellent cost parameters but poor predictive performance on a test set should not be trusted.

Cost function analysis, particularly the interpretation of the null hypothesis cost and configuration cost, provides an indispensable foundation for robust pharmacophore model validation. A ΔCost > 60 signifies a model unlikely to be a product of chance, while a configuration cost < 17 guards against overfitting. By adhering to this protocol and integrating it with other validation techniques such as Fischer randomization and decoy set validation, researchers can confidently select pharmacophore models with genuine predictive power. This rigorous approach significantly enhances the efficiency of virtual screening and the likelihood of successfully identifying novel lead compounds in drug discovery campaigns.

In pharmacophore model validation, the robustness of the test set—defined by its chemical diversity and structural variety—is a critical determinant of predictive accuracy and real-world applicability. Pharmacophore models abstract the essential steric and electronic features necessary for a ligand to interact with a biological target, forming the foundation for virtual screening in computer-aided drug design [6] [23]. However, even a perfectly conceived pharmacophore hypothesis remains functionally unvalidated without rigorous testing against a representative set of compounds that adequately captures the chemical space of interest.

A robust test set serves as the ultimate proving ground, challenging the pharmacophore model's ability to generalize beyond the training compounds and correctly identify structurally diverse active molecules while rejecting inactive ones. The composition of this test set directly impacts validation metrics such as enrichment factors and Güner-Henry scores, which measure the model's practical utility in drug discovery campaigns [3] [24]. Without careful attention to chemical diversity and structural variety, researchers risk developing models that perform well on paper but fail to identify novel scaffolds in virtual screening experiments, ultimately wasting valuable resources on false leads.

The critical importance of test set design stems from the fundamental challenges in chemoinformatics. Models derived from limited chemical space tend to exhibit poor extrapolation capabilities when confronted with structurally diverse compounds or those containing unusual functional groups [25]. Furthermore, the presence of structural outliers—compounds with unique moieties not represented in the training data—can disproportionately influence model performance if not properly accounted for in the test set [25]. Therefore, a strategically designed test set acts as a diagnostic tool, revealing potential weaknesses and ensuring the model's stability against the natural variations found in large chemical databases.

Theoretical Foundation: Why Test Set Composition Matters

The Relationship Between Chemical Space and Model Generalization

The concept of chemical space represents a fundamental framework for understanding model generalization in pharmacophore-based virtual screening. Chemical space encompasses all possible molecules and their associated properties, forming a multidimensional continuum where compounds with similar structural features and biological activities tend to cluster [25] [26]. A robust pharmacophore model must effectively navigate this space to identify novel active compounds, making comprehensive test set coverage essential for meaningful validation.

Pharmacophore models developed without adequate consideration of chemical space coverage often suffer from overfitting to the training compounds' specific structural patterns. Such models may demonstrate excellent performance for compounds similar to those in the training set but fail to identify active compounds with different scaffolds or substitution patterns [25]. This limitation directly impacts virtual screening efficiency, as evidenced by studies showing that stepwise and adaptive selection approaches with better chemical space coverage yield models with superior error performance and stability compared to traditional methods [25].

The Impact of Structural Outliers and Domain of Applicability

Structural outliers—compounds characterized by unique chemical groups or structural motifs not well-represented in the training data—present a particular challenge for pharmacophore models [25]. These compounds often reside in sparsely populated regions of the chemical space and can significantly influence model performance if not properly accounted for during validation. A test set lacking such structural diversity provides a false sense of security by not challenging the model's boundaries of applicability.

The domain of applicability defines the chemical space region where a model's predictions can be considered reliable. A well-constructed test set should systematically probe this domain by including compounds at the periphery of the chemical space, not just those near the densely populated core regions [25]. Research has shown that the property of a molecule to be a structural outlier can depend on the descriptor set used, further emphasizing the need for test sets that challenge the model from multiple representational perspectives [25].

Table 1: Types of Chemical Diversity in Robust Test Sets

| Diversity Dimension | Description | Impact on Model Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Scaffold Diversity | Variation in core molecular frameworks | Tests model's ability to recognize actives beyond training scaffolds |

| Functional Group Diversity | Inclusion of different chemical moieties | Challenges feature identification and alignment |

| Property Diversity | Range of molecular weight, logP, etc. | Ensures model works across property space |

| Complexity Diversity | Variation in molecular size and complexity | Tests feature selection and weighting |

Protocols for Constructing Robust Test Sets

Experimental Protocol: Systematic Test Set Construction with Chemical Diversity Analysis

Objective: To construct a test set with sufficient chemical diversity and structural variety to rigorously validate pharmacophore model performance and generalization capability.

Materials and Reagents:

- Compound databases (e.g., ZINC, ChEMBL, commercial collections)

- Chemical structure visualization software (e.g., ChemBioOffice)

- Computational chemistry tools (e.g., Discovery Studio, Schrödinger Suite)

- Diversity analysis scripts or software (e.g., RDKit, Canvas)

Procedure:

Define the Chemical Space Boundaries

- Compile all available active compounds for the target of interest from public databases (e.g., ChEMBL, BindingDB) and literature sources [24] [2]

- Calculate molecular descriptors (e.g., molecular weight, logP, topological polar surface area, hydrogen bond donors/acceptors) to characterize the property space

- Perform principal component analysis (PCA) on the descriptor matrix to identify the major dimensions of variation within the active compounds [25]

Select Structurally Diverse Actives

- Apply maximum dissimilarity selection algorithms (e.g., Kennard-Stone) to identify compounds that span the chemical space defined in step 1 [25]

- Ensure representation of different molecular scaffolds, not just varying side chains

- Include compounds with unusual structural features or functional groups that may challenge the pharmacophore model

- Verify that the selected compounds cover the range of bioactivity values (e.g., IC50, Ki) relevant to the project goals

Curate Decoy Compounds with Matched Properties

- Generate decoy compounds using tools such as the Database of Useful Decoys (DUDe) or similar approaches [2]

- Match decoys to active compounds based on molecular weight, logP, and other physicochemical properties but ensure topological dissimilarity

- Include decoys with similar functional groups but different spatial arrangements to test the model's geometric specificity

- Apply drug-like filters (e.g., Lipinski's Rule of Five) if relevant to the project's therapeutic context [24]

Validate Test Set Diversity

- Calculate pairwise molecular similarity metrics (e.g., Tanimoto coefficients) to verify structural diversity [25]

- Visualize the chemical space coverage using dimensionality reduction techniques (t-SNE, UMAP) to confirm that the test set adequately represents the applicable chemical space [26]

- Ensure the test set includes compounds that probe specific pharmacophore features (e.g., hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions, charged groups)

Experimental Protocol: Statistical Validation of Test Set Composition

Objective: To quantitatively assess the chemical diversity and structural variety of a test set using statistical measures and ensure its suitability for pharmacophore model validation.

Materials and Reagents:

- Pre-constructed test set (from Protocol 3.1)

- Statistical analysis software (e.g., R, Python with pandas, scikit-learn)

- Molecular fingerprint generation tools (e.g., RDKit, OpenBabel)

- Diversity metrics calculation scripts

Procedure:

Calculate Diversity Metrics

- Generate molecular fingerprints (e.g., ECFP4, FCFP6) for all test set compounds

- Compute pairwise Tanimoto similarity matrix and analyze the distribution

- Calculate internal diversity metrics: mean pairwise similarity, similarity percentile ranges

- Determine scaffold diversity using Bemis-Murcko framework analysis and count unique scaffolds

Assess Chemical Space Coverage

- Perform PCA on the fingerprint descriptor space and project training and test sets

- Calculate the coverage ratio: percentage of training set chemical space covered by the test set

- Identify coverage gaps where the test set lacks representatives from certain regions of the training set chemical space

- Use Euclidean distance histograms in the latent feature space to quantify diversity as demonstrated in MAD dataset analyses [26]

Evaluate Activity Distribution

- Ensure the test set covers the full range of bioactivity values present in the available data

- Verify that the distribution of active versus inactive compounds reflects realistic screening expectations (typically 0.1-1% actives for enrichment calculations)

- Stratify the test set by activity class (high, medium, low, inactive) and verify diversity within each stratum

Perform Cluster Analysis

- Apply clustering algorithms (e.g., k-means, hierarchical clustering) to the chemical descriptor space

- Verify that test set compounds represent multiple clusters rather than concentrating in a few chemical classes

- Ensure that each major cluster contains both active and inactive compounds to test the model's discriminative power within chemical neighborhoods

Table 2: Key Statistical Metrics for Test Set Evaluation

| Metric Category | Specific Metrics | Target Values | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Diversity | Mean pairwise Tanimoto similarity, Unique scaffolds/Total compounds | <0.5 similarity, >30% unique scaffolds | Lower similarity and higher scaffold count indicate greater diversity |

| Chemical Space Coverage | Percentage of training set PCA space covered, Gap analysis | >80% coverage, Minimal large gaps | Higher coverage ensures comprehensive testing of model applicability |

| Activity Representation | Range of pIC50/pKi values, Active/inactive ratio | Full range, 0.1-1% actives | Complete activity range tests predictive accuracy across potencies |

| Cluster Distribution | Number of clusters represented, Balance across clusters | Multiple clusters, Reasonable balance | Ensures testing across different chemical classes |

Validation Methods for Assessing Pharmacophore Model Performance

Experimental Protocol: Güner-Henry (GH) Validation Method

Objective: To validate pharmacophore model performance using the Güner-Henry method, which measures the model's ability to enrich active compounds from a test set containing both active and decoy molecules.

Materials and Reagents:

- Validated pharmacophore model (structure-based or ligand-based)

- Test set with known active compounds and decoys

- Virtual screening software (e.g., Discovery Studio, LigandScout)

- Calculation spreadsheet for GH metrics

Procedure:

Prepare the Test Database

- Combine known active compounds (A) with decoy compounds (D) to create a test database of size N

- Ensure the total number of actives (A) is known and the decoys are property-matched but chemically distinct

- For the test set, typical sizes range from 1,000 to 10,000 compounds with active compound percentages between 0.1% and 1% [3] [2]

Perform Pharmacophore-Based Screening

- Screen the entire test database against the pharmacophore model using flexible search methods

- Record the number of hits (Ht) obtained from the screening process

- From the hits, identify how many are true actives (Ha)

Calculate Güner-Henry Metrics

- Compute the enrichment factor (EF) using the formula: EF = (Ha/Ht) / (A/N)

- Calculate the GH score using the comprehensive formula that incorporates yield of actives and false positives

- Determine the percentage yield of actives: (Ha/Ht) × 100

- Calculate the percentage ratio of actives: (Ha/A) × 100 [3]

Interpret the Results

- Compare the EF value to ideal enrichment: EF = 1 indicates random performance, while higher values indicate better enrichment

- Evaluate the GH score on a scale of 0-1, where values closer to 1 indicate better model performance

- Assess the balance between sensitivity (Ha/A) and specificity (1 - false positive rate) based on the results

Experimental Protocol: Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) Analysis

Objective: To evaluate the discriminative power of a pharmacophore model using ROC analysis, which provides a comprehensive view of the model's sensitivity and specificity across all classification thresholds.

Materials and Reagents:

- Pharmacophore model with scoring function

- Test set with known active and inactive compounds

- Statistical analysis software with ROC curve capabilities

- Spreadsheet software for data recording and visualization

Procedure:

Generate Pharmacophore Fit Scores

- Screen all test set compounds (both active and inactive) against the pharmacophore model

- Record the fit score or alignment score for each compound

- For multi-conformer compounds, use the best-fitting conformation

Calculate Sensitivity and Specificity Across Thresholds

- Sort compounds by their fit scores in descending order

- Systematically vary the classification threshold from the highest to lowest fit score

- At each threshold, calculate:

- True Positives (TP): Active compounds with fit score ≥ threshold

- False Positives (FP): Inactive compounds with fit score ≥ threshold

- True Negatives (TN): Inactive compounds with fit score < threshold

- False Negatives (FN): Active compounds with fit score < threshold

- Compute sensitivity (Recall) = TP/(TP+FN)

- Compute specificity = TN/(TN+FP)

- Compute 1 - Specificity (False Positive Rate)

Generate and Interpret ROC Curve

- Plot the ROC curve with False Positive Rate (1-Specificity) on the x-axis and Sensitivity on the y-axis

- Calculate the Area Under the Curve (AUC) using numerical integration methods

- Interpret the AUC value:

- AUC = 0.5: No discriminative power (random classification)

- 0.7 ≤ AUC < 0.8: Acceptable discriminative power

- 0.8 ≤ AUC < 0.9: Excellent discriminative power

- AUC ≥ 0.9: Outstanding discriminative power [2]

Calculate Additional Performance Metrics

- Compute Precision = TP/(TP+FP)

- Calculate F1-Score = 2 × (Precision × Recall)/(Precision + Recall)

- Determine Optimal Threshold using Youden's J statistic (Sensitivity + Specificity - 1)

Case Studies and Applications

Case Study: XIAP Inhibitor Discovery with Validated Test Sets

In a comprehensive study targeting X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP) for cancer therapy, researchers demonstrated the critical importance of robust test sets in pharmacophore validation [2]. The study employed a structure-based pharmacophore model generated from a protein-ligand complex (PDB: 5OQW) containing a known inhibitor with experimentally measured IC50 value of 40.0 nM.

Test Set Design and Validation:

- The test set comprised 10 known XIAP antagonists with experimentally determined IC50 values merged with 5,199 decoy compounds obtained from the Directory of Useful Decoys (DUDe)

- This carefully designed test set with a high ratio of decoys to actives (approximately 520:1) provided a rigorous challenge for the pharmacophore model

- The chemical diversity of the test set was ensured by including compounds with varied scaffolds and functional groups, effectively representing the chemical space of potential XIAP binders

Validation Results:

- The pharmacophore model achieved an exceptional early enrichment factor (EF1%) of 10.0, indicating strong ability to identify active compounds in the early stages of virtual screening

- The area under the ROC curve (AUC) value reached 0.98 at the 1% threshold, demonstrating outstanding discriminative power between active and decoy compounds

- This high-level performance was directly attributable to the comprehensive test set that thoroughly probed the model's capabilities across diverse chemical structures

Virtual Screening Outcome:

- Subsequent virtual screening of natural product databases identified seven hit compounds, with three (Caucasicoside A, Polygalaxanthone III, and MCULE-9896837409) showing particular promise in molecular dynamics simulations

- The success in identifying novel natural product scaffolds with potential XIAP inhibitory activity underscored the value of rigorous test set validation in practical drug discovery applications

Case Study: Akt2 Inhibitor Development with Dual Pharmacophore Approach

A study focused on discovering novel Akt2 inhibitors for cancer therapy implemented a dual pharmacophore approach validated with comprehensive test sets [24]. The researchers developed both structure-based and 3D-QSAR pharmacophore models, then applied stringent validation protocols to ensure their utility in virtual screening.

Test Set Composition:

- The test set for the structure-based pharmacophore included 63 known active compounds collected from scientific literature, spanning a range of bioactivities

- For the 3D-QSAR pharmacophore, a separate test set of 40 molecules was used to validate the model's predictive accuracy

- Decoy set validation employed 2,000 molecules consisting of 1,980 compounds with unknown activity and 20 known Akt2 inhibitors

Test Set Diversity Considerations:

- The test sets included compounds with different molecular scaffolds to challenge the models' ability to recognize essential pharmacophore features across diverse chemical contexts

- Activity values spanned multiple orders of magnitude, ensuring the models could distinguish not just actives from inactives but also highly potent from moderately active compounds

- The high proportion of decoys in the validation set (99% of the total) created a realistic simulation of virtual screening conditions where active compounds are rare

Validation Outcomes:

- The structure-based pharmacophore model (PharA) contained seven pharmacophoric features and successfully identified active compounds that mapped to at least six of these features

- Both models demonstrated strong performance in test set and decoy set validation, giving confidence to proceed with virtual screening of large compound databases

- The subsequent screening of nearly 700,000 compounds from natural product and commercial databases, followed by drug-like filtering and ADMET analysis, identified seven promising hit compounds with diverse scaffolds

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Test Set Construction and Validation

| Reagent/Tool Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compound Databases | ZINC, ChEMBL, BindingDB, Coconut Database | Source of active and diverse compounds for test sets | Provides chemical structures and bioactivity data for test set construction [24] [2] [27] |

| Decoy Generation Tools | DUDe (Directory of Useful Decoys) | Generate property-matched but topologically distinct inactive compounds | Creates challenging negative controls for validation [2] |

| Diversity Analysis Software | RDKit, Canvas, Schrodinger Suite | Calculate molecular similarity, clustering, and diversity metrics | Quantifies test set diversity and chemical space coverage [25] |

| Virtual Screening Platforms | Discovery Studio, LigandScout, Phase | Perform pharmacophore-based screening and fit score calculation | Generates hit lists and scores for validation metrics [28] [24] [2] |

| Validation Metric Calculators | Custom scripts for GH scoring, ROC analysis | Compute enrichment factors, AUC values, and other validation parameters | Quantitatively assesses model performance [3] [24] |

The critical importance of robust test sets in pharmacophore model validation cannot be overstated. As demonstrated throughout this protocol, test sets characterized by extensive chemical diversity and structural variety serve as the essential proving ground for pharmacophore models, challenging their ability to generalize beyond training compounds and perform effectively in real-world virtual screening applications. The comprehensive protocols outlined for test set construction, statistical validation, and performance assessment provide researchers with practical methodologies to ensure their pharmacophore models are rigorously evaluated before deployment in resource-intensive drug discovery campaigns.

The case studies examining XIAP and Akt2 inhibitor discovery underscore how thoughtfully constructed test sets directly contribute to successful identification of novel lead compounds [24] [2]. By implementing the Güner-Henry method, ROC analysis, and chemical diversity assessments detailed in these application notes, researchers can significantly increase confidence in their pharmacophore models and improve the efficiency of subsequent virtual screening efforts. In an era where computational approaches play an increasingly central role in drug discovery, robust validation practices centered on chemically diverse test sets remain fundamental to translating in silico predictions into biologically active therapeutic agents.

The Validation Toolkit: Step-by-Step Protocols for Assessing Model Performance

The rigorous validation of computational models is a cornerstone of credible research in computer-aided drug design (CADD). Pharmacophore models, which abstract the essential steric and electronic features required for molecular recognition, are powerful tools for virtual screening [6] [29]. However, their predictive performance can be misleading if evaluated using biased benchmark datasets. The Decoy Set Method addresses this critical issue by employing carefully selected, non-binding molecules (decoys) to simulate a realistic screening scenario and provide an unbiased estimate of model effectiveness [30]. This Application Note details the implementation of this method using the DUD-E (Database of Useful Decoys: Enhanced) benchmark, providing a structured protocol for the rigorous evaluation of pharmacophore models within a best-practice framework for validation methods research [30] [31].

The DUD-E Database: A Foundation for Unbiased Benchmarking

DUD-E is a widely adopted benchmark database designed to eliminate the artificial enrichment that plagued earlier benchmarking sets. Its development was driven by the need for a rigorous and realistic platform for evaluating structure-based virtual screening (SBVS) methods [30] [31].

Core Principles and Design

The fundamental principle of DUD-E is to provide decoy molecules that are physically similar yet chemically distinct from known active molecules for a given target. This "property-matched decoy" strategy is engineered to minimize biases that could allow trivial discrimination based on simple physicochemical properties alone [30]. The design of DUD-E incorporates several key aspects:

- Physicochemical Matching: Decoys are matched to actives based on key properties such as molecular weight, calculated logP, and number of hydrogen bond donors and acceptors. This ensures that simple property-based filters cannot easily separate actives from decoys [30].

- Chemical Dissimilarity: Despite physical similarity, decoys are chemically distinct from actives to ensure they are unlikely to bind the target. This is typically assessed via topological fingerprinting, ensuring decoys do not share key functional motifs with actives [30].

- Drug-like Nature: Decoys are sourced from databases like ZINC and are selected to exhibit drug-like properties, making the virtual screening experiment more representative of a real-world drug discovery campaign [30].

The table below summarizes the quantitative scope of the DUD-E database, highlighting its extensive coverage of targets and compounds, which provides a robust foundation for statistical evaluation.

Table 1: Quantitative Summary of the DUD-E Database Scope

| Category | Description | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Target Coverage | Number of protein targets included | 102 targets [30] |

| Ligand Coverage | Number of active ligands | ~22,000 active compounds [30] |

| Decoy Ratio | Average number of decoys per active | 50 decoys per active [30] |

| Key Property | Reported average DOE score of original DUD-E decoys | 0.166 [30] |

Quantitative Evaluation Metrics and Protocol

A rigorous evaluation requires a set of quantitative metrics to assess the performance of a pharmacophore model in distinguishing actives from decoys. The following section outlines the key metrics and a standardized protocol for their calculation.

Key Performance Metrics

The performance of a virtual screening method is typically evaluated using enrichment-based metrics and statistical measures derived from the ranking of actives and decoys.

Table 2: Key Quantitative Metrics for Pharmacophore Model Evaluation

| Metric | Formula/Description | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| AUC ROC | Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve | Measures the overall ability to rank actives above decoys. A value of 0.5 indicates random performance, 1.0 indicates perfect separation [30]. |

| Enrichment Factor (EF) | (Hitssselected / Nselected) / (Hitsstotal / Ntotal) | Measures the concentration of actives in a selected top fraction of the screened database compared to a random selection [29]. |

| Recall (True Positive Rate) | TP / (TP + FN) | The fraction of all known actives that were successfully retrieved by the model [32]. |

| Precision | TP / (TP + FP) | The fraction of retrieved compounds that are actually active [32]. |

| DOE Score | Deviation from Optimal Embedding; a measure of physicochemical property matching between actives and decoys. | A lower score indicates superior property matching, reducing the risk of artificial enrichment. DeepCoy improved the average DUD-E DOE from 0.166 to 0.032 [30]. |

Experimental Validation Protocol

This protocol provides a step-by-step guide for using DUD-E to evaluate a pharmacophore model.

1. Data Acquisition and Preparation:

- Download the DUD-E dataset for your target of interest from the official website (http://dude.docking.org/).

- Prepare the ligand files (both actives and decoys) for screening. This typically involves:

- Format Conversion: Ensure all structures are in a consistent format (e.g., SDF, MOL2).

- Tautomer and Stereoisomer Enumeration: Generate possible tautomers and stereoisomers for molecules with undefined chiral centers or double bonds [32].

- Conformer Generation: For flexible molecules, generate a representative ensemble of 3D conformations. A common practice is to generate up to 100 conformers per molecule within a defined energy range (e.g., 50 kcal/mol) using a force field like MMFF94 [32].

2. Pharmacophore-Based Virtual Screening:

- Load your pharmacophore model into a suitable software platform (e.g., LigandScout [29]).

- Screen the prepared database of actives and decoys against the model.

- The screening process often involves multiple steps to enhance efficiency [32]:

- Fingerprint Pre-screening: Use pharmacophore fingerprints as a Bloom filter to quickly discard molecules that are highly unlikely to match.

- Geometric Mapping: For the remaining candidates, perform a subgraph isomorphism check to see if the pharmacophore's topology is present.

- 3D Hash Comparison: Finally, compare the 3D pharmacophore hashes of the query model and the candidate molecules to confirm a match with identical topology and stereoconfiguration.

3. Result Analysis and Metric Calculation:

- Ranking: Rank all screened compounds (actives and decoys) based on the pharmacophore fit value or scoring function.

- Calculate Metrics: Using the ranked list, calculate the performance metrics outlined in Table 2, such as AUC ROC, EF at 1% and 10%, and precision-recall curves.

- Visual Inspection: Manually inspect the top-ranked hits to validate the proposed binding mode and the rationale behind the model's selections.

Advanced Application: Generating Improved Decoys with DeepCoy

While DUD-E provides a robust baseline, recent advances in deep learning offer methods to generate even more rigorously matched decoys, further reducing potential bias.

The DeepCoy Methodology

DeepCoy is a deep learning-based approach that frames decoy generation as a multimodal graph-to-graph translation problem [30]. It uses a variational autoencoder framework with graph neural networks to generate decoys from active molecules.

Workflow Overview:

- Input: An active molecule is provided as a graph.

- Encoding: The graph is encoded into a latent representation.

- Decoding: A new molecular graph (the decoy) is generated from this representation in a "bond-by-bond" manner, guided by chemical valency rules [30].

- Output: The generated decoy matches the physicochemical properties of the input active but is structurally dissimilar, minimizing the risk of being a false negative [30].

Quantitative Performance of DeepCoy

The table below compares the performance of DeepCoy-generated decoys against the original DUD-E decoys, demonstrating a significant reduction in bias.

Table 3: Quantitative Comparison of DeepCoy vs. Original DUD-E Decoys

| Metric | Original DUD-E Decoys | DeepCoy-Generated Decoys | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average DOE Score | 0.166 [30] | 0.032 [30] | 81% decrease |

| Virtual Screening AUC (Autodock Vina) | 0.70 [30] | 0.63 [30] | Performance closer to random, indicating harder-to-distinguish decoys |

The Research Toolkit

A successful evaluation requires a suite of software tools and data resources. The following table catalogues essential reagents for implementing the DUD-E decoy set method.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Software Solutions

| Item Name | Type | Function in Protocol | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| DUD-E Database | Data Resource | Provides the benchmark set of active and property-matched decoy molecules for rigorous validation. | http://dude.docking.org/ [30] |

| DeepCoy | Software Tool | Generates deep learning-improved decoys with tighter property matching to actives, further reducing dataset bias. | https://github.com/oxpig/DeepCoy [30] |

| LigandScout | Software Tool | A comprehensive platform for structure- and ligand-based pharmacophore model creation, refinement, and virtual screening. | Commercial & Academic Licenses [29] |

| ROCS | Software Tool | Performs rapid shape and "color" (chemical feature) overlay of molecules, useful for scaffold hopping and validation. | Commercial (OpenEye) [31] |

| PLANTS | Software Tool | A molecular docking software used for flexible ligand sampling; can be integrated with pharmacophore constraints. | Academic Free License [31] |

| RDKit | Software Tool | An open-source cheminformatics toolkit used for fundamental tasks like conformer generation, fingerprinting, and molecule manipulation. | Open Source [32] |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the complete experimental workflow for the rigorous evaluation of a pharmacophore model using the DUD-E framework, from data preparation to final performance assessment.

Workflow for Pharmacophore Model Evaluation Using DUD-E

The implementation of the decoy set method using the DUD-E database represents a best practice in pharmacophore model validation. By providing a large set of property-matched decoys, DUD-E mitigates the risk of artificial enrichment and ensures that reported performance metrics reflect a model's true capacity for molecular recognition rather than its ability to exploit dataset biases. The integration of advanced tools like DeepCoy can further refine this process, generating decoys that push the boundaries of rigorous benchmarking. Adherence to the detailed protocols and quantitative evaluation frameworks outlined in this Application Note will empower researchers to deliver robust, reliable, and scientifically credible pharmacophore models, thereby strengthening the foundation of computer-aided drug discovery.

Fischer's Randomization Test is a cornerstone statistical method in pharmacophore model validation, serving as a critical safeguard against chance correlations. This protocol details the systematic application of the test within the drug discovery pipeline, providing researchers with a robust framework to distinguish meaningful structure-activity relationships from random artifacts. By implementing this methodology, scientists can enhance the predictive reliability of their pharmacophore models before proceeding to resource-intensive virtual screening and experimental validation stages.

In computational drug discovery, pharmacophore models abstract the essential steric and electronic features necessary for molecular recognition by a biological target. However, any quantitative model derived from a limited set of compounds risks capturing accidental correlations rather than genuine biological relationships. Fischer's Randomization Test (also referred to as a permutation test) addresses this fundamental validation challenge by providing a statistical framework to quantify the probability that the observed correlation occurred by random chance [1].

The test operates on a straightforward premise: if the original pharmacophore model captures a true structure-activity relationship, then randomizing the biological activity values across the training set compounds should rarely produce hypotheses with comparable or better statistical significance. By repeatedly generating pharmacophore models from these randomized datasets, researchers can construct a distribution of correlation coefficients under the null hypothesis of no true relationship, then determine where the original model's correlation falls within this distribution [1] [24]. This approach has become a standard validation component across diverse drug discovery applications, including histone deacetylase [33], Akt2 [24], and butyrylcholinesterase inhibitors [34].

Theoretical Foundation and Statistical Principles

Historical Context and Development

The randomization test was initially developed by Ronald Fisher in the 1930s as a rigorous method for assessing statistical significance without relying on strict distributional assumptions [35] [36]. Fisher's original conceptualization emerged from his famous "lady tasting tea" experiment, which demonstrated the power of randomization in testing hypotheses [36]. The method was later adapted for computational chemistry applications, particularly with the rise of pharmacophore modeling in the 1990s, where it now serves as a crucial validation step in modern drug discovery workflows.

Mathematical Basis

The test evaluates the statistical significance of a pharmacophore hypothesis through a permutation approach. The fundamental steps involve:

Calculation of the Original Test Statistic: The correlation coefficient (R) between predicted and experimental activities for the training set compounds serves as the initial test statistic [33].

Randomization Procedure: The biological activity values (e.g., IC₅₀) are randomly shuffled and reassigned to the training set compounds, thereby breaking any genuine structure-activity relationship while preserving the distribution of activity values [1].

Generation of Randomized Models: For each randomized dataset, a new pharmacophore hypothesis is generated using identical parameters and features as the original model [33] [34].

Construction of Null Distribution: The correlation coefficients from all randomized models form a distribution representing what can be expected by chance alone.

Significance Calculation: The statistical significance (p-value) is computed as the proportion of randomized models that yield a correlation coefficient equal to or better than the original model [1] [35]:

( p = \frac{\text{number of randomized models with } R{\text{random}} \geq R{\text{original}} + 1}{\text{total number of randomizations} + 1} )

Experimental Protocol and Workflow

Pre-Test Requirements

Before initiating Fischer's Randomization Test, researchers must ensure the following prerequisites are met:

- A Robust Pharmacophore Model: Generate the initial pharmacophore hypothesis using established methods (e.g., HypoGen algorithm) with a carefully curated training set [33].

- Training Set Characterization: The training set should contain compounds with biological activities (IC₅₀ values) spanning at least four orders of magnitude to ensure sufficient dynamic range for model development [33].

- Statistical Baseline: Record the correlation coefficient (R), root mean square deviation (RMSD), and total cost values for the original pharmacophore model [33] [34].

Step-by-Step Implementation Protocol

Step 1: Configuration Setup

- Set the confidence level to 95% as standard practice [33].

- Determine the number of randomizations (typically 19-999 iterations), balancing computational resources against statistical precision [1] [35].

Step 2: Activity Randomization

- Randomly shuffle the activity data (IC₅₀ values) across the training set compounds while maintaining the molecular structures unchanged [1].

- Ensure each activity value is assigned to a different compound in each randomization.

Step 3: Hypothesis Generation

- For each randomized dataset, generate new pharmacophore hypotheses using identical parameters and features as the original model [24] [34].

- Employ the same conformational generation method and cost calculation parameters as used for the original hypothesis [33].

Step 4: Statistical Comparison

- Calculate the correlation coefficient for each randomized hypothesis [1].

- Count the number of randomized hypotheses that show correlation coefficients equal to or better than the original hypothesis.

Step 5: Significance Determination

- Compute the p-value using the formula provided in Section 2.2.

- A p-value ≤ 0.05 indicates the original model is statistically significant at the 95% confidence level [33] [1].

Step 6: Results Interpretation

- Models passing the test (p ≤ 0.05) can proceed to further validation stages.

- Models failing the test (p > 0.05) should be reconsidered, as they likely represent chance correlations.

Below is a workflow diagram illustrating the complete Fischer's Randomization Test procedure:

Critical Statistical Parameters and Interpretation

Table 1: Key Statistical Parameters in Fischer's Randomization Test

| Parameter | Optimal Value | Interpretation | Clinical Research Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Confidence Level | 95% | Standard threshold for statistical significance in pharmacological studies | Equivalent to α = 0.05, balancing Type I and Type II error rates |

| Number of Randomizations | 19-999 | Fewer iterations (19) for quick screening; more for precise p-values | More randomizations provide finer p-value resolution but increase computational time |

| p-value | ≤ 0.05 | Indicates <5% probability that the original correlation occurred by chance | Standard benchmark for statistical significance in pharmacological research |

| Correlation Coefficient (R) | Varies by model | Measure of predictive ability for training set compounds | Higher values indicate stronger structure-activity relationships |

Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Pharmacophore Validation

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Application | Specifications/Requirements |

|---|---|---|

| Discovery Studio (DS) | Comprehensive platform for pharmacophore generation and validation | HypoGen algorithm for hypothesis generation; Fischer's randomization implementation [33] |

| Training Set Compounds | Molecules with experimentally determined biological activities | Ideally 20-50 compounds with IC₅₀ values spanning 4-5 orders of magnitude [33] |

| Conformational Generation Method | Creates energetically reasonable 3D conformations for each compound | FAST conformation method; maximum 255 conformers; energy threshold: 20 kcal/mol [33] |

| Cost Analysis Metrics | Evaluates statistical significance of pharmacophore hypotheses | Total cost, null cost, configuration cost; Δcost (null-total) > 60 indicates >90% significance [33] [1] |

| External Test Set | Independent validation of model predictive ability | 10-20 compounds not included in training set; diverse chemical structures and activities [33] [24] |

Integration with Comprehensive Validation Protocols

Fischer's Randomization Test represents one essential component within a comprehensive pharmacophore validation framework. To establish complete confidence in a pharmacophore model, researchers should integrate this test with additional validation methods:

Cost Analysis: Compare the total cost of the hypothesis to fixed and null costs. A difference (Δcost) greater than 60 bits between null and total costs suggests a 90% probability of true correlation [33] [1].

Test Set Prediction: Validate the model against an external test set of compounds with known activities. The predicted versus experimental activities should show strong correlation (R²pred > 0.5) [1].

Decoy Set Validation: Evaluate the model's ability to distinguish active compounds from inactive molecules using enrichment factors (EF) and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves [1] [24].

This multi-faceted validation approach ensures that pharmacophore models possess both statistical significance and practical predictive utility before deployment in virtual screening campaigns.

Troubleshooting and Quality Control

Common Issues and Solutions:

High p-value (>0.05): If the test indicates insignificance, revisit the training set composition. Ensure adequate structural diversity and activity range. Consider modifying pharmacophore features or increasing training set size.

Computational Limitations: For large training sets, complete permutation enumeration may be prohibitive. Implement random sampling of permutations (typically 4,000-10,000 subsets) to approximate p-values [35].

Configuration Cost: Verify that configuration costs remain below 17, as higher values indicate excessive model complexity [1].

Reproducibility: Maintain consistent parameters (conformational generation, feature definitions) across all randomizations to ensure valid comparisons.

Fischer's Randomization Test provides an indispensable statistical foundation for pharmacophore model validation in computational drug discovery. By rigorously testing against the null hypothesis of chance correlation, this method adds crucial confidence to models before their application in virtual screening and lead optimization. When integrated with cost analysis, test set prediction, and decoy set validation, it forms part of a robust validation framework that minimizes false positives and enhances the efficiency of drug discovery pipelines. Implementation of this protocol ensures that pharmacophore models represent genuine structure-activity relationships rather than statistical artifacts, ultimately contributing to more successful identification of novel therapeutic compounds.

Analyzing Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) Curves and Enrichment Factors (EF)

In modern computational drug discovery, pharmacophore modeling serves as a critical method for identifying novel therapeutic compounds by abstracting essential chemical features responsible for biological activity [23]. These models, whether structure-based or ligand-based, provide a framework for virtual screening of large chemical databases, significantly reducing the time and cost associated with traditional drug development approaches [37] [38]. However, the predictive accuracy and reliability of pharmacophore models depend entirely on rigorous validation methodologies, primarily employing Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves and Enrichment Factors (EF) as key statistical measures [2].

The validation process assesses a model's ability to distinguish between active compounds (true positives) and inactive compounds (true negatives) through screening experiments against carefully curated datasets containing both types of molecules [39]. ROC analysis graphically represents the trade-off between sensitivity (true positive rate) and specificity (true negative rate) across different classification thresholds, while EF quantifies the model's performance in enriching active compounds early in the screening process [38] [2]. Together, these metrics provide complementary insights into model quality and practical utility for virtual screening campaigns, forming the statistical foundation for reliable pharmacophore-based drug discovery [23].

Theoretical Foundations of ROC and EF Analysis

Key Statistical Metrics and Calculations

The validation of pharmacophore models relies on fundamental statistical metrics derived from confusion matrix analysis, which classifies screening outcomes into true positives (TP), false positives (FP), true negatives (TN), and false negatives (FN) [39]. Sensitivity, or true positive rate, measures the proportion of actual active compounds correctly identified by the model and is calculated as TP/(TP+FN) [37]. Specificity, or true negative rate, measures the proportion of inactive compounds correctly rejected and is calculated as TN/(TN+FP) [37]. These primary metrics form the basis for both ROC curve generation and enrichment factor calculation.

The ROC curve plots sensitivity against (1-specificity) across all possible classification thresholds, providing a visual representation of the model's diagnostic ability [38] [2]. The Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC) serves as a single-figure summary of overall performance, with values ranging from 0 to 1, where 0.5 indicates random discrimination and 1.0 represents perfect classification [38]. AUC values between 0.7-0.8 are considered acceptable, 0.8-0.9 excellent, and >0.9 outstanding for pharmacophore models [38].

The Enrichment Factor (EF) measures how much better a model performs at identifying active compounds compared to random selection, particularly focusing on early recognition [2]. EF is typically calculated for the top 1% of screened compounds (EF1%) but can be determined for any fraction of the screened database [2]. The maximum achievable EF depends on the ratio of actives to decoys in the screening library, making it crucial for comparative analyses between different validation studies [39].

Advanced Validation Metrics

Beyond basic ROC and EF analysis, the Güner-Henry (GH) scoring method provides a composite metric that combines measures of recall (sensitivity), precision, and enrichment in a single value ranging from 0 to 1, where higher scores indicate better model performance [39]. The GH score incorporates the percentage of known actives identified in the hit list (Ha), the percentage of hit list compounds that are known actives (Ya), the enrichment factor for early recognition (E), and the total number of compounds in the database (N) [39].

Additional statistical measures include the goodness of hit (GH) score, which provides a weighted measure considering both the yield of actives and the false positive rate [37]. Some validation protocols also employ the robust initial enhancement (RIE) metric, which offers a more statistically stable alternative to traditional enrichment factors, particularly when dealing with small sets of known active compounds [39].

Table 1: Key Statistical Metrics for Pharmacophore Model Validation

| Metric | Formula | Interpretation | Optimal Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | TP/(TP+FN) | Ability to identify true actives | >0.8 |