Automated Tumor Segmentation with Deep Learning: Current Approaches, Clinical Applications, and Future Directions

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of automated tumor segmentation using deep learning, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Automated Tumor Segmentation with Deep Learning: Current Approaches, Clinical Applications, and Future Directions

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of automated tumor segmentation using deep learning, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of AI in medical imaging, examines state-of-the-art methodologies including CNN and Transformer architectures, and addresses critical optimization challenges such as data efficiency and model generalization. The content synthesizes performance validation across multiple datasets and clinical applications, offering insights into the integration of these technologies in biomedical research and therapeutic development.

The Evolution of AI in Tumor Segmentation: From Basic Concepts to Current Landscape

Medical image segmentation, a fundamental process of dividing medical images into distinct regions of interest, has undergone remarkable transformations with the emergence of deep learning (DL) techniques [1]. This technology serves as a critical bridge between medical imaging and clinical applications by enabling precise delineation of anatomical structures and pathological findings. In oncology, automated tumor segmentation using deep learning represents a paradigm shift, offering solutions to labor-intensive manual contouring while addressing significant inter-observer variability among clinicians [2]. The clinical significance of accurate segmentation extends across diagnostic interpretation, treatment planning, intervention guidance, and therapy response monitoring, forming an essential component of modern precision medicine initiatives.

The evolution from traditional segmentation methods to deep learning-based approaches has coincided with growing demands for diagnostic excellence in clinical settings [3]. As healthcare systems worldwide face mounting pressures from increasing image complexity and volume, deep learning technologies have demonstrated potential to enhance workflow efficiency, reduce cognitive burden on clinicians, and ultimately improve patient outcomes through more consistent and quantitative image analysis.

Technical Approaches in Medical Image Segmentation

Deep Learning Architectures

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) represent the foundational architecture for most medical image segmentation tasks. These networks employ a series of convolutional layers that automatically and adaptively learn spatial hierarchies of features from medical images [3] [4]. The U-Net architecture, with its encoder-decoder structure and skip connections, has become particularly prominent in medical imaging, enabling precise localization while leveraging contextual information [3]. For tumor segmentation in radiotherapy, 3D U-Net models have demonstrated robust performance in capturing volumetric information from CT scans [2].

Beyond CNNs, several specialized architectures have emerged. Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) facilitate analysis of temporal sequences, making them suitable for 4D imaging data that captures organ motion [3]. Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) contribute to data augmentation and image synthesis, helping address limited dataset sizes [3]. More recently, Vision Transformers (ViTs) have shown promise in capturing long-range dependencies through self-attention mechanisms, while hybrid models that integrate multiple architectural concepts offer enhanced performance for complex segmentation tasks [3].

Loss Functions for Medical Imaging

The choice of loss function significantly influences segmentation performance, particularly for class-imbalanced medical data where target regions often occupy minimal image area. The Dice Loss function directly optimizes for the Dice Similarity Coefficient, a standard overlap metric in medical imaging [5]. To address class imbalance, the Generalized Dice Loss incorporates weighting terms that account for region size [5]. For clinical applications where boundary accuracy is crucial, such as tumor segmentation, Hausdorff distance-based losses like the Generalized Surface Loss provide enhanced performance by minimizing the maximum segmentation error [5]. In practice, composite loss functions that combine multiple objectives, such as Dice-CE loss (Dice plus Cross-Entropy), often yield superior results by balancing overlap accuracy with probabilistic calibration [5].

Table 1: Common Loss Functions in Medical Image Segmentation

| Loss Function | Mathematical Formulation | Advantages | Clinical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dice Loss (DL) | 1 - (2∑TₖPₖ + ε)/(∑Tₖ² + ∑Pₖ² + ε) | Optimizes directly for overlap metric; handles class imbalance | General organ and tumor segmentation |

| Generalized Dice Loss (GDL) | 1 - 2(∑wₖ∑TₖPₖ)/(∑wₖ∑(Tₖ² + Pₖ²)) | Weighted for multi-class imbalance; improved consistency | Multi-class segmentation problems |

| Generalized Surface Loss | Weighted distance transform-based | Minimizes Hausdorff distance; better boundary alignment | Tumor segmentation where boundary accuracy is critical |

| Dice-CE Loss | ℒ_dice - α(∑∑Tₖlog(Pₖ)) | Combines overlap and probabilistic calibration | General purpose with enhanced training stability |

Performance Metrics and Quantitative Evaluation

Traditional Geometric Metrics

The evaluation of medical image segmentation algorithms relies on well-established geometric metrics that quantify spatial agreement between automated results and reference standards. The Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC) measures volume overlap, ranging from 0 (no overlap) to 1 (perfect overlap), with values exceeding 0.7 typically indicating clinically acceptable performance [2]. The Hausdorff Distance (HD) quantifies the largest segmentation error by measuring the maximum distance between surfaces, making it particularly sensitive to boundary outliers [5]. In practice, the 95th percentile HD (HD95) is often used instead of the maximum to reduce sensitivity to single-point outliers [2].

For radiotherapy applications, where tumor segmentation directly influences treatment efficacy, these metrics provide essential quality assurance. In a multicenter study of automated lung tumor segmentation for radiotherapy, a 3D U-Net model achieved median DSC of 0.73 (IQR: 0.62-0.80) on internal validation and 0.70-0.71 on external cohorts, demonstrating performance comparable to human inter-observer variability [2]. This level of agreement suggests clinical viability for automated approaches in complex oncology applications.

Advanced Evaluation Approaches

While traditional metrics provide valuable geometric insights, they may not fully capture clinically relevant segmentation characteristics. Radiomics features have emerged as a superior evaluation framework that quantifies segmentation quality through tumor characteristics beyond simple shape overlap [6]. These features can detect subtle variations in segmentation that might be missed by DSC and HD metrics alone [6].

The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of radiomics features demonstrates greater sensitivity to segmentation changes than geometric metrics, with specific wavelet-transformed features (e.g., wavelet-LLL first order Maximum, wavelet-LLL glcm MCC) showing ICC values ranging from 0.130 to 0.997 compared to DSC values consistently above 0.778 for the same segmentations [6]. This enhanced sensitivity makes radiomics particularly valuable for evaluating segmentation algorithms intended for quantitative imaging biomarkers in oncology clinical trials and drug development studies.

Table 2: Performance Metrics for Medical Image Segmentation Evaluation

| Metric Category | Specific Metrics | Interpretation | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overlap Metrics | Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC) | 0-1 scale; higher values indicate better overlap | Intuitive; widely used in literature | Insensitive to boundary differences; treats all errors equally |

| Distance Metrics | Hausdorff Distance (HD), Average Surface Distance (ASD) | Distance in mm; lower values indicate better boundary alignment | Sensitive to boundary errors; clinically relevant | HD is sensitive to outliers; requires surface computation |

| Statistical Metrics | Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) of Radiomics Features | 0-1 scale; higher values indicate better feature reproducibility | Captures texture and intensity characteristics; more sensitive to subtle variations | Computationally complex; requires specialized extraction |

| Clinical Metrics | False Positive Voxel Rate, Target Coverage | Relationship to patient outcomes | Direct clinical relevance; predictive of efficacy | Requires outcome data; complex statistical analysis |

Experimental Protocols for Automated Tumor Segmentation

Dataset Curation and Preprocessing

Comprehensive dataset collection forms the foundation of robust segmentation models. Major public repositories include The Cancer Imaging Archive (TCIA), which maintains extensive cancer-specific image collections, and institution-specific resources like the Stanford AIMI collections, which provide large-scale annotated imaging data (e.g., CheXpert Plus with 223,462 chest X-ray pairs) [7]. The LiTS (Liver Tumor Segmentation) and BraTS (Brain Tumor Segmentation) datasets serve as benchmark resources for specific tumor types [5]. For multicenter validation, datasets should encompass diverse imaging protocols, scanner manufacturers, and patient populations to ensure generalizability [2].

Essential preprocessing steps include: (1) image resampling to uniform voxel spacing (typically 1-2mm isotropic) to ensure consistent spatial resolution [6]; (2) intensity normalization to address scanner-specific variations; (3) data augmentation through geometric transformations (rotation, scaling, elastic deformations) and intensity variations to increase dataset diversity and improve model robustness [3]; and (4) expert annotation with board-certified radiologists or radiation oncologists following established contouring guidelines, with multiple annotators where feasible to quantify inter-observer variability [2].

Model Training and Validation Framework

The nnU-Net framework provides a standardized approach for biomedical image segmentation, automatically configuring network architecture and preprocessing based on dataset characteristics [5]. For tumor segmentation, 3D U-Net architectures typically outperform 2D counterparts by capturing volumetric context [2]. Training should employ k-fold cross-validation (typically 5-fold) to maximize data utilization and provide robust performance estimates [2].

Implementation details should include: (1) patch-based training to manage memory constraints while maintaining spatial context; (2) balanced sampling strategies to address class imbalance between foreground and background voxels; (3) composite loss functions combining region-based (e.g., Dice) and boundary-based (e.g., Generalized Surface Loss) terms [5]; (4) optimization with adaptive methods (Adam, SGD with momentum) with learning rate scheduling; and (5) extensive data augmentation including random rotations, scaling, brightness/contrast adjustments, and simulated artifacts [3].

Validation must occur across multiple cohorts, including internal hold-out test sets and external datasets from different institutions to assess generalizability [2]. Model performance should be compared against human inter-observer variability to establish clinical relevance, with statistical testing (e.g., Wilcoxon signed-rank tests) to determine significant differences [2]. For radiotherapy applications, segmentation models should additionally generate saliency maps via integrated gradients to interpret feature contributions and identify potential failure modes [2].

Public Datasets and Annotated Collections

Access to high-quality annotated medical imaging data is fundamental for developing and validating segmentation algorithms. The Cancer Imaging Archive (TCIA) represents one of the largest cancer-focused resources, providing de-identified images accessible for public download [7]. OpenNeuro offers extensive neuroimaging data, hosting over 1,240 public datasets with information from more than 51,000 participants across multiple modalities (MRI, PET, MEG, EEG) [7]. The NIH Chest X-Ray Dataset contains over 100,000 anonymized chest X-ray images from more than 30,000 patients, serving as a cornerstone for thoracic imaging research [7]. Specialized collections like MedPix provide educational and research resources with approximately 59,000 images across 9,000 topics [7], while MIDRC maintains COVID-19-specific imaging data collected from diverse clinical settings [7].

Software Frameworks and Computational Tools

The technical implementation of segmentation algorithms relies on robust software frameworks. PyRadiomics enables standardized extraction of radiomics features from medical images, supporting quantitative analysis of segmentation results [6]. The nnU-Net framework provides out-of-the-box solutions for biomedical image segmentation, automatically adapting to dataset characteristics [5]. 3D Slicer offers a comprehensive platform for medical image visualization and analysis, incorporating segmentation capabilities and metric calculation [6]. Collective Minds Research represents an integrated platform for managing large-scale imaging datasets while maintaining security and compliance, facilitating collaborative research across institutions [7].

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for Medical Image Segmentation

| Resource Category | Specific Resources | Key Features | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Public Datasets | TCIA, OpenNeuro, NIH Chest X-Ray | Curated collections; multiple modalities; annotated cases | Algorithm training; benchmarking; validation |

| Annotation Platforms | 3D Slicer, ITK-SNAP, Collective Minds | Expert annotation tools; quality control; collaborative features | Ground truth generation; dataset creation |

| Software Frameworks | nnU-Net, PyRadiomics, MONAI | Pre-built architectures; standardized processing; reproducibility | Model development; feature extraction; deployment |

| Evaluation Tools | 3D Slicer, Custom Python Scripts | Metric calculation; statistical analysis; visualization | Performance validation; comparative studies |

Clinical Translation and Applications

Radiotherapy Planning and Treatment

Automated tumor segmentation has found particularly valuable applications in radiotherapy planning, where accurate target delineation directly influences treatment efficacy and toxicity. The iSeg neural network for lung tumor segmentation demonstrates how deep learning can streamline the radiotherapy workflow by automatically generating gross tumor volumes (GTVs) across 4D CT images to create internal target volumes (ITVs) that account for respiratory motion [2]. Notably, machine-generated ITVs were significantly smaller (by 30% on average) than physician-delineated contours while maintaining target coverage, suggesting potential for normal tissue sparing without compromising tumor control [2].

Beyond time savings, automated segmentation addresses the significant inter-observer variability that plagues manual contouring in radiotherapy. Studies comparing iSeg performance against expert recontouring demonstrated that the algorithm closely approximated inter-physician concordance limits (DSC 0.75 vs. 0.80 for human observers) [2]. Perhaps most importantly, clinical outcome correlations revealed that higher false positive voxel rates (regions segmented by the machine but not humans) were associated with increased local failure (HR: 1.01 per voxel, p=0.03), suggesting that machine-human discordance may identify clinically relevant regions that warrant additional scrutiny [2].

Integration with Clinical Workflows

Successful implementation of automated segmentation requires thoughtful integration with existing clinical workflows and electronic health record (EHR) systems. Emerging visualization dashboards like AWARE are designed to integrate within existing EHR systems, providing clinical decision support through enhanced data presentation that reduces cognitive load on clinicians [8]. These systems transform complex medical data into interpretable visual formats, allowing providers to quickly grasp essential information while maintaining access to automated segmentation results [8].

The future clinical integration of these technologies will likely involve hybrid human-AI collaboration, where algorithms provide initial segmentations that clinicians efficiently review and refine. This approach leverages the consistency and quantitative capabilities of automated systems while retaining clinician oversight for complex cases and unusual anatomies. As these technologies mature, they hold potential not only to improve efficiency but also to enhance standardization across institutions and support clinical trial quality assurance through more consistent implementation of segmentation protocols.

The evolution of tumor segmentation in medical imaging represents a paradigm shift from manual, subjective analysis toward automated, AI-driven diagnostics. Traditional methods, reliant on clinicians' visual assessments and rudimentary image processing techniques, have long been plagued by subjectivity, inter-observer variability, and inefficiency [9]. The advent of deep learning, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and U-Net architectures, has fundamentally transformed this landscape, enabling precise, automated, and reproducible tumor delineation. This transition is critically important in neuro-oncology, where accurate tumor boundary definition directly impacts surgical planning, treatment monitoring, and survival prediction [10] [11]. The integration of these technologies into clinical workflows marks a significant advancement in precision medicine, offering enhanced diagnostic accuracy and standardized analysis across healthcare institutions.

The Traditional Paradigm: Manual Segmentation and Rule-Based Systems

Core Methodologies and Limitations

Traditional brain tumor analysis relied heavily on manual radiologic assessment and classical image processing techniques. These methods required neuroradiologists to visually inspect magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans and manually delineate tumor boundaries—a labor-intensive process prone to significant inter-observer variation [9]. Rule-based computational approaches included thresholding, edge detection, region growing, and morphological processing. These techniques operated on low-level image features such as intensity gradients and texture patterns but lacked the adaptability to handle the complex morphological heterogeneity inherent in brain tumors [9] [10].

The fundamental limitation of these traditional systems was their dependence on hand-crafted features, which failed to capture the extensive spatial and contextual diversity of gliomas, meningiomas, and other intracranial tumors across different patients and imaging protocols [9]. Furthermore, these methods demonstrated poor robustness to imaging artifacts, noise, and intensity variations commonly encountered in clinical settings.

Quantitative Performance of Traditional Approaches

The table below summarizes the characteristic performance metrics of traditional tumor segmentation methodologies compared to early deep learning approaches:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Traditional vs. Early Deep Learning Methods

| Method Category | Representative Techniques | Typical Dice Score | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Manual Segmentation | Radiologist visual assessment | 0.65-0.75 (inter-observer variation) | Time-consuming (45+ minutes/case), high inter-observer variability [2] |

| Traditional Image Processing | Thresholding, region growing, edge detection | 0.60-0.70 | Sensitive to noise and intensity variations; poor generalization [9] |

| Classical Machine Learning | Support Vector Machines (SVM), Random Forests with hand-crafted features | 0.70-0.75 | Limited feature representation; requires expert feature engineering [10] |

| Early Deep Learning | Basic CNN architectures | 0.80-0.85 | Required large datasets; computationally intensive [10] |

The Deep Learning Revolution: Architectural Innovations and Performance Gains

Convolutional Neural Networks and U-Net Architectures

The introduction of deep learning, particularly CNNs, marked a turning point in medical image analysis. Unlike traditional methods, CNNs automatically learn hierarchical feature representations directly from image data, eliminating the need for manual feature engineering [9]. The U-Net architecture, with its symmetric encoder-decoder structure and skip connections, emerged as a particularly transformative innovation, enabling precise pixel-level segmentation while preserving spatial context [10].

Recent architectural evolution has focused on hybrid models that combine the strengths of multiple paradigms. Transformer-enhanced U-Nets incorporating self-attention mechanisms have demonstrated remarkable improvements in capturing long-range dependencies in medical images. In 2025, models such as MWG-UNet++ achieved Dice similarity coefficients of 0.8965 on brain tumor segmentation tasks, representing a 12.3% improvement over traditional U-Nets [12]. Similarly, the integration of Vision Mamba layers in architectures like CM-UNet has improved inference speed by 40% while maintaining competitive segmentation accuracy [12].

Quantitative Advancements in Tumor Segmentation

The performance leap enabled by deep learning is quantitatively demonstrated through standardized benchmarks like the BraTS (Brain Tumor Segmentation) challenge. The table below summarizes the state-of-the-art performance achieved by various deep learning models:

Table 2: Performance of Advanced Deep Learning Models on Brain Tumor Segmentation (BraTS Dataset)

| Model Architecture | Whole Tumor Dice | Tumor Core Dice | Enhancing Tumor Dice | Key Innovations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DSNet (2025) | 0.959 | 0.975 | 0.947 | 3D Dynamic CNN, adversarial learning, attention mechanisms [11] |

| Transformer-enhanced U-Net (2025) | 0.917 (average) | - | - | Axial attention mechanisms, residual path reconstruction [12] |

| Hybrid CNN (2024) | 0.937 (mean) | - | - | RGB multichannel fusion (T1w, T2w, average) [13] |

| 3D U-Net with Attention | 0.92-0.94 | 0.91-0.93 | 0.88-0.90 | Integrated attention gates; volumetric context [10] |

| iSeg (3D U-Net for Lung Tumors) | 0.73 (median) | - | - | Multicenter validation; motion-resolved segmentation [2] |

Beyond segmentation accuracy, deep learning models have demonstrated exceptional performance in tumor classification tasks. A 2025 meta-analysis of meningioma grading reported pooled sensitivity of 92.31% and specificity of 95.3% across 27 studies involving 13,130 patients, with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.97 [14]. For multi-class brain tumor classification, hybrid deep learning approaches have achieved accuracies exceeding 98-99% on benchmark datasets [15] [16] [17].

Experimental Protocols for Deep Learning-Based Tumor Segmentation

Protocol 1: 3D Brain Tumor Segmentation Using DSNet

Application: Precise volumetric segmentation of gliomas from multimodal MRI data for surgical planning and treatment monitoring.

Materials and Reagents:

- Multimodal MRI scans (T1-weighted, T1ce, T2-weighted, FLAIR) in DICOM format

- High-performance computing infrastructure with GPU acceleration (NVIDIA RTX 3090 or equivalent)

- Python 3.8+ with PyTorch or TensorFlow deep learning frameworks

- BraTS dataset for model training and validation

Methodology:

- Data Preprocessing: Co-register all multimodal MRI sequences to a common spatial coordinate system. Apply N4ITK bias field correction to address intensity inhomogeneities. Normalize intensity values to zero mean and unit variance across the entire dataset [11].

- Patch Extraction: Extract overlapping 3D patches (128×128×128 voxels) from the preprocessed volumes to manage memory constraints while preserving spatial context.

- Network Architecture: Implement the DSNet framework comprising:

- A 3D dynamic convolutional neural network (DCNN) backbone with residual connections

- Multi-scale feature aggregation modules to capture contextual information at different resolutions

- Attention gates to emphasize tumor-relevant regions

- Adversarial training components to refine boundary delineation

- Training Protocol: Train the model for 1000 epochs with a batch size of 8 using a combination of Dice and cross-entropy loss functions. Utilize the Adam optimizer with an initial learning rate of 1e-4, reduced by half when validation performance plateaus for 50 consecutive epochs.

- Inference and Post-processing: Apply the trained model to full MRI volumes using a sliding window approach. Use connected component analysis to remove false positive predictions outside the brain parenchyma [11].

Validation: Evaluate performance on the BraTS 2020 validation set using Dice Similarity Coefficient, Hausdorff Distance, and Sensitivity metrics. Compare results against ground truth annotations from expert neuroradiologists.

Protocol 2: Multi-Class Brain Tumor Classification Using Ensemble Learning

Application: Automated discrimination of meningioma, glioma, pituitary tumors, and normal cases from MRI scans.

Materials and Reagents:

- Curated dataset of brain MRI images (e.g., Figshare, Kaggle datasets)

- Image preprocessing tools for sharpening and noise reduction (mean filtering)

- Feature selection algorithms (correlation-based feature selection)

- Machine learning libraries (Weka, Scikit-learn) and deep learning frameworks

Methodology:

- Data Preprocessing: Convert DICOM images to 512×512 pixel digital format. Apply sharpening algorithms to enhance edges and mean filtering for noise reduction [16].

- Tumor Segmentation: Implement Edge-Refined Binary Histogram Segmentation (ER-BHS) to isolate tumor regions:

- Calculate optimal threshold by maximizing inter-class variance between foreground and background pixels

- Apply morphological operations to refine tumor boundaries

- Feature Extraction: Extract a comprehensive set of 66 hybrid features from each segmented tumor region, including:

- First-order histogram features (mean, standard deviation, skewness, energy, entropy)

- Second-order texture features from gray-level co-occurrence matrices (energy, correlation, entropy, inverse difference, inertia)

- Spectral and wavelet features for texture analysis

- Feature Optimization: Apply correlation-based feature selection with best-first search to identify the most discriminative features, reducing the feature set to 11 key dimensions [16] [17].

- Model Training and Evaluation: Train multiple classifiers (Random Committee, Random Forest, J48, Neural Networks) using 10-fold cross-validation. Employ patient-level data splitting to prevent information leakage.

Validation: Assess performance using accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score. The Random Committee classifier has demonstrated 98.61% accuracy on optimized hybrid feature sets [16].

Visualization of Methodological Evolution

Workflow Transition: Traditional to Deep Learning Approaches

U-Net Architectural Evolution and Hybridization

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for Deep Learning-Based Tumor Analysis

| Resource Category | Specific Tools & Platforms | Application in Tumor Analysis | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medical Imaging Datasets | BraTS (2018-2025), Kaggle Brain MRI, Figshare | Model training, validation, and benchmarking | Multimodal MRI (T1, T1ce, T2, FLAIR), expert annotations, standardized evaluation [10] |

| Deep Learning Frameworks | PyTorch, TensorFlow, MONAI | Model development and implementation | GPU acceleration, pre-built layers, medical imaging specialization [11] |

| Network Architectures | 3D U-Net, DSNet, Transformer-Enhanced U-Net | Tumor segmentation, boundary delineation | Volumetric processing, attention mechanisms, multi-scale analysis [12] [11] |

| Preprocessing Tools | N4ITK, SimpleITK, intensity normalization | Image quality enhancement, artifact reduction | Bias field correction, intensity standardization, data augmentation [9] |

| Evaluation Metrics | Dice Similarity Coefficient, Hausdorff Distance, Sensitivity/Specificity | Performance quantification | Volumetric overlap, boundary accuracy, clinical relevance assessment [2] [11] |

| Visualization Tools | Grad-CAM, attention maps, saliency maps | Model interpretability, clinical trust | Region importance visualization, decision process explanation [15] |

The historical transition from traditional methods to deep learning approaches in tumor segmentation represents one of the most significant advancements in medical image analysis. This evolution has moved the field from subjective, time-consuming manual delineation toward automated, precise, and reproducible segmentation systems that approach—and in some cases surpass—human-level performance. The integration of transformer architectures, attention mechanisms, and adversarial training has addressed fundamental challenges in handling tumor heterogeneity, morphological complexity, and imaging protocol variations. As these technologies continue to mature, their clinical translation promises to standardize diagnostic workflows, enhance quantitative tumor assessment, and ultimately improve patient care through more accurate treatment planning and monitoring. Future research directions will likely focus on enhancing model interpretability, enabling federated learning for privacy-preserving multi-institutional collaboration, and developing lightweight architectures for real-time clinical deployment.

Accurate tumor segmentation from medical images is a cornerstone of modern oncology, directly impacting diagnosis, treatment planning, and therapy response monitoring. While deep learning has revolutionized this field, achieving robust, clinical-grade performance remains challenging due to significant obstacles, including inter-observer variability, imaging noise and artifacts, and the inherent biological complexity of tumors themselves. This application note dissects these core challenges, provides a quantitative analysis of current methodologies, and offers detailed protocols to guide researchers in developing and validating more reliable segmentation tools. The content is framed within the broader objective of advancing automated tumor segmentation for both clinical and research applications, such as streamlining workflows in drug development and enabling precise volumetric analysis for clinical trials.

Quantitative Analysis of Segmentation Performance

The performance of segmentation models varies significantly across tumor types, anatomical sites, and imaging protocols. The following tables summarize key quantitative metrics from recent studies to benchmark current capabilities and highlight performance variations.

Table 1: Performance of Deep Learning Models for Brain Tumor Segmentation on BraTS Datasets

| Model / Study | Tumor Subregion | Dice Score (DSC) | Key MRI Sequences Used | Dataset |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3D U-Net [18] | Enhancing Tumor (ET) | 0.867 | T1C + FLAIR | BraTS 2018/2021 |

| 3D U-Net [18] | Tumor Core (TC) | 0.926 | T1C + FLAIR | BraTS 2018/2021 |

| MM-MSCA-AF [19] | Necrotic Tumor | 0.8158 | T1, T1C, T2, FLAIR | BraTS 2020 |

| MM-MSCA-AF [19] | Whole Tumor | 0.8589 | T1, T1C, T2, FLAIR | BraTS 2020 |

| BSAU-Net [20] | Whole Tumor | 0.7556 | Multi-modal | BraTS 2021 |

| ARU-Net [21] | Multi-class | 0.981 | T1, T1C, T2 | BTMRII |

Table 2: Performance and Variability in Multi-Site and Multi-Organ Segmentation

| Study Context | Anatomical Site / OAR | Median Dice (DSC) | Key Finding / Variability |

|---|---|---|---|

| iSeg Model [2] | Lung (GTV) | 0.73 (IQR: 0.62-0.80) | Matched human inter-observer variability; robust across institutions. |

| AI Software Evaluation [22] | Cervical Esophagus | DSC: 0.41 (Range) | Exhibited the largest intersoftware variation among 31 OARs. |

| AI Software Evaluation [22] | Spinal Cord | DSC: 0.13 (Range) | Significant intersoftware performance variation. |

| AI Software Evaluation [22] | Heart, Liver | DSC: >0.90 | High accuracy, consistent across multiple software platforms. |

Deconstructing the Key Challenges

Inter-Observer and Inter-Software Variability

The "ground truth" used to train deep learning models is often defined by human experts, whose segmentations are prone to inconsistency. This inter-observer variability presents a major challenge for model training and validation. Studies have shown that the agreement between different physicians, as measured by the Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC), can be as low as ~0.80 for certain tasks, establishing a performance ceiling for automated systems [2]. Furthermore, this variability is not just a human issue. A comprehensive evaluation of eight commercial AI-based segmentation software platforms revealed significant intersoftware variability, particularly for complex organs-at-risk (OARs) like the cervical esophagus (DSC variation of 0.41) and spinal cord (DSC variation of 0.13) [22]. This indicates that the choice of software alone can introduce substantial inconsistency in segmentation outputs, potentially affecting downstream treatment plans and multi-center trial results.

Data Heterogeneity, Noise, and Protocol Dependency

Medical imaging data is inherently heterogeneous. Models must be robust to variations in scanner protocols, image resolution, contrast, and noise across different institutions [22]. A prominent challenge in clinical deployment is the dependency on complete, multi-sequence MRI protocols. Relying on a full set of sequences (T1, T1C, T2, FLAIR) creates a barrier to widespread adoption, as incomplete data is common in real-world settings [23]. Research has shown that the absence of key sequences drastically impacts performance; for instance, using FLAIR-only sequences resulted in exceptionally low Dice scores for enhancing tumor (ET: 0.056) [18]. Conversely, studies have demonstrated that robust performance can be maintained with minimized data. The combination of T1-weighted contrast-enhanced (T1C) and T2-FLAIR sequences has been identified as a core, efficient protocol capable of delivering segmentation accuracy for whole tumor and enhancing tumor that is comparable to, and sometimes better than, using all four sequences [18] [23].

Tumor Biological Complexity and Class Imbalance

The biological nature of tumors introduces fundamental segmentation difficulties. High spatial and structural variability, diffuse infiltration (especially in gliomas), and the presence of multiple subregions within a single tumor pose significant hurdles [18]. Models must simultaneously delineate the necrotic core, enhancing tumor, and surrounding edema, each with distinct imaging characteristics [19]. This task is further complicated by class imbalance, where voxels belonging to tumor subregions are vastly outnumbered by healthy tissue voxels. This imbalance can cause models to become biased toward the majority class, leading to poor segmentation of small but critical tumor areas [20]. Attention mechanisms and tailored loss functions have been developed to address this, forcing the model to focus on under-represented yet clinically vital regions.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Evaluating MRI Sequence Dependencies for Glioma Segmentation

This protocol is designed to identify the minimal set of MRI sequences required for robust glioma segmentation, enhancing model generalizability and clinical applicability.

1. Research Question: Which combination of standard MRI sequences provides optimal segmentation accuracy for glioma subregions while minimizing data requirements?

2. Experimental Design:

- Dataset: Utilize a publicly available, curated dataset such as the BraTS 2021 dataset, which contains multi-institutional MRI data with expert-annotated ground truth for tumor subregions [23].

- Input Configurations: Systematically train and evaluate models on all clinically relevant combinations of the four core sequences: T1-native (T1n), T1-contrast enhanced (T1c), T2-weighted (T2w), and T2-FLAIR (T2f). Key combinations to test include T1c-only, T2f-only, T1c+T2f, and the full set T1n+T1c+T2w+T2f [18] [23].

- Model Architecture: Employ a standard 3D U-Net, a proven and widely used architecture for medical image segmentation, to isolate the effect of input sequences from architectural innovations [18].

3. Methodology:

- Pre-processing: Apply standard pre-processing steps to all data, including co-registration to a common template, interpolation to a uniform resolution, and intensity normalization.

- Training: Use 5-fold cross-validation on the training cohort to ensure robust performance estimation.

- Validation: Evaluate the trained models on a held-out test set that was not used during training or cross-validation.

4. Key Output Metrics:

- Primary Metric: Dice Similarity Coefficient for Enhancing Tumor, Tumor Core, and Whole Tumor.

- Secondary Metrics: Sensitivity, Specificity, and 95th percentile Hausdorff Distance.

- Statistical Analysis: Perform Wilcoxon signed-rank tests with multiple-hypothesis correction to determine if volumetric differences between simplified protocols and the full-protocol ground truth are statistically significant [23].

5. Interpretation: A simplified protocol is considered clinically viable if it achieves DSC scores that are not statistically inferior to the full protocol and produces tumor volumes that are not significantly different from the expert reference standard.

Protocol: Benchmarking Model Robustness Against Inter-Observer Variability

This protocol assesses whether an automated segmentation model performs within the bounds of human inter-observer variability.

1. Research Question: Does the automated segmentation model's performance fall within the range of variation observed between different human experts?

2. Experimental Design:

- Ground Truth: Establish a reference set of medical images with tumor volumes delineated by multiple board-certified experts.

- Comparison Groups: Calculate agreement metrics between: a) different human experts, and b) the model prediction and each expert's delineation.

3. Methodology:

- Segmentation Task: Apply the model to the test set to generate automated segmentations.

- Metric Calculation: For every case in the test set, compute the DSC for the following pairings:

- Expert 1 vs. Expert 2

- Model vs. Expert 1

- Model vs. Expert 2

4. Key Output Metrics:

- Primary Metric: Dice Similarity Coefficient.

- Statistical Analysis: Compare the distributions of DSC values using statistical tests. A model is considered to have passed this benchmark if its agreement with experts is not significantly worse than the inter-observer agreement between the experts themselves [2].

Protocol: Assessing Multi-Site Generalizability

This protocol validates the performance of a segmentation model on external, independent datasets to ensure generalizability.

1. Research Question: How well does a model trained on data from one institution perform on data acquired from different institutions with varying scanners and protocols?

2. Experimental Design:

- Internal Cohort: Use a dataset from one or multiple institutions for model training and initial validation.

- External Cohorts: Acquire at least two independent test datasets from separate hospital systems that were not represented in the training data.

3. Methodology:

- Model Training: Train the model on the internal cohort.

- Model Testing: Apply the trained model directly to the external cohorts without fine-tuning.

- Performance Comparison: Quantify performance on all cohorts using consistent metrics.

4. Key Output Metrics:

- Primary Metric: Median Dice Similarity Coefficient and its interquartile range.

- Analysis: The model demonstrates strong generalizability if performance on external cohorts is comparable to that on the internal cohort [2].

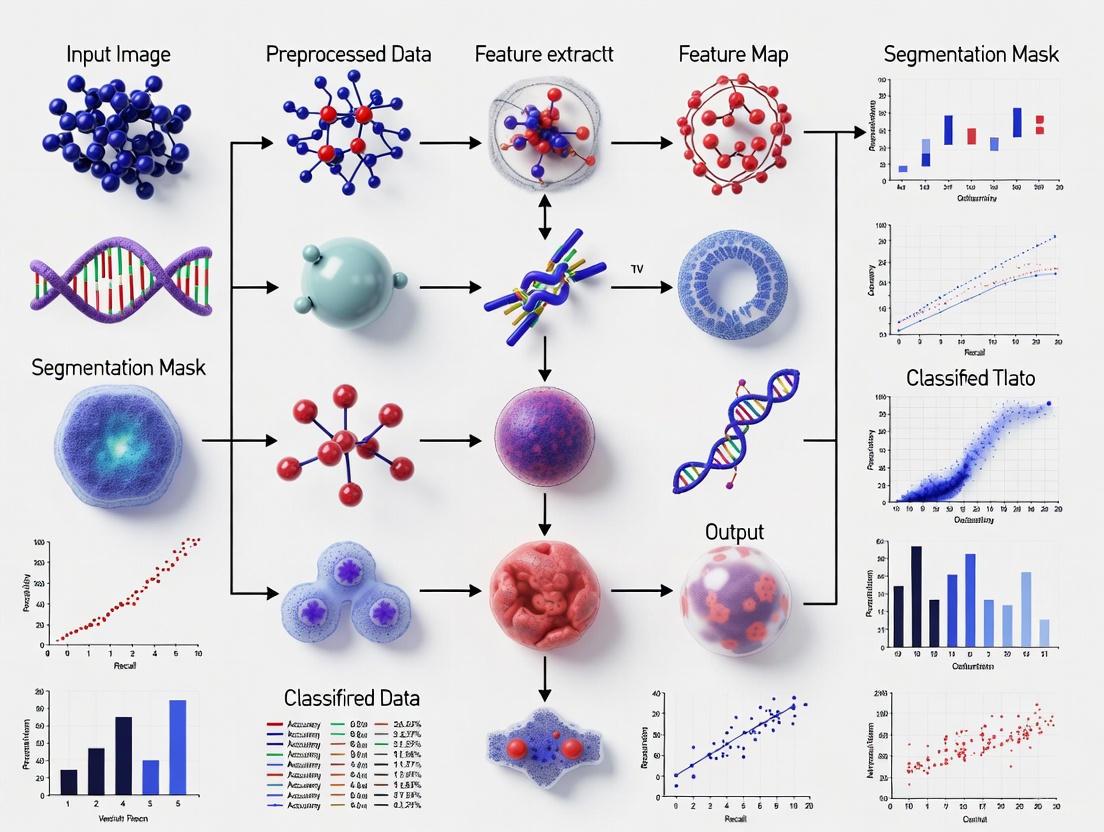

Visualizing the Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow of a robust model development and validation protocol, as described in the previous sections.

Figure 1: Workflow for developing and validating a robust segmentation model, from data curation through to deployment, emphasizing critical validation steps.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for Tumor Segmentation Research

| Resource Category | Specific Example / Tool | Function & Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Benchmark Datasets | BraTS (Brain Tumor Segmentation) Dataset [18] [19] [23] | Provides multi-institutional, multi-modal MRI with expert-annotated ground truth for training and benchmarking models. |

| Core Model Architectures | 3D U-Net [18] [2] | A standard, highly effective convolutional network backbone for volumetric medical image segmentation. |

| Advanced Architectures | MM-MSCA-AF [19], ARU-Net [21], BSAU-Net [20] | Incorporate attention mechanisms and multi-scale feature aggregation to handle complexity and improve edge accuracy. |

| Performance Metrics | Dice Similarity Coefficient, Hausdorff Distance [18] [2] [22] | Quantify spatial overlap and boundary accuracy of segmentations compared to ground truth. |

| Validation Frameworks | 5-Fold Cross-Validation, External Test Cohorts [18] [2] | Ensure reliable performance estimation and test for model generalizability across unseen data. |

| Statistical Analysis | Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test [23] | Determine the statistical significance of performance differences between models or protocols. |

Public benchmarks, such as the Brain Tumor Segmentation (BraTS) dataset and the associated challenges organized by the Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention (MICCAI) conference, have become foundational pillars in the field of automated tumor segmentation using deep learning. These community-driven initiatives provide the essential infrastructure for standardized evaluation, enabling researchers to benchmark their algorithms against a common baseline using high-quality, expert-annotated data. By offering a transparent and fair platform for comparison, they significantly accelerate the translation of algorithmic innovations into tools with genuine clinical potential. Furthermore, the iterative nature of these annual challenges, with progressively evolving datasets and tasks, directly fuels technical advancements, pushing the community to develop more accurate, robust, and generalizable models. This application note details the role of these public resources, providing researchers with a structured overview of the BraTS dataset's evolution, the framework of MICCAI challenges, and practical protocols for engaging with these critical tools.

The BraTS Dataset: Evolution and Impact

The Brain Tumor Segmentation (BraTS) challenge has curated and expanded a multi-institutional dataset annually since 2012, establishing it as the premier benchmark for evaluating state-of-the-art brain tumor segmentation algorithms [24]. The dataset's evolution is characterized by a deliberate increase in size, diversity, and annotation complexity, directly reflecting the community's growing understanding of the clinical problem.

Historical Progression and Key Features

The following table summarizes the quantitative and qualitative progression of the BraTS dataset, highlighting its expansion in scale and clinical relevance.

Table 1: Evolution of the BraTS Dataset (2012-2025)

| Challenge Year | Key Features and Advancements | Dataset Size & Composition | Clinical & Technical Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2012-2014 (Early Years) | Establishment of core multi-parametric MRI protocol (T1, T1Gd, T2, FLAIR); Initial focus on glioblastoma (GBM) sub-region segmentation. | Limited cases (∼30-50 glioma scans) from a few institutions. | Created a standardized benchmarking foundation; catalyzed research into automated segmentation. |

| 2015-2020 (Rapid Growth) | significant dataset expansion; inclusion of lower-grade gliomas; introduction of pre-processing standards (co-registration, skull-stripping). | Growth to hundreds, then thousands of subjects from multiple international centers. | Enabled training of more complex deep learning models (e.g., U-Net, nnU-Net); improved generalizability. |

| 2021-2024 (Maturation) | Integration of extensive metadata (clinical, molecular); focus on synthetic data generation (BraSyn) for missing modalities; enhanced annotation protocols. | Thousands of subjects from the RSNA-ASNR-MICCAI collaboration; largest multi-institutional mpMRI dataset of brain tumors. | Facilitated development of algorithms robust to real-world clinical challenges like missing sequences and domain shift [25]. |

| 2025 (Current/Future) | Designated a MICCAI Lighthouse Challenge; expanded focus on longitudinal response assessment, underrepresented populations, and further clinical needs [26] [24]. | Continues to grow with new data; includes pre- and post-treatment follow-up imaging for dynamic assessment. | Aims to drive innovations in predictive and prognostic modeling for precision medicine. |

Data Composition and Annotation Standardization

A critical strength of the BraTS dataset is its standardized composition and rigorous annotation protocol. Each subject typically includes four essential MRI sequences: native T1-weighted (T1), post-contrast T1-weighted (T1Gd), T2-weighted (T2), and T2-FLAIR (Fluid Attenuated Inversion Recovery) [24] [25]. These sequences provide complementary information crucial for delineating different tumor sub-compartments. The ground truth segmentation labels are generated through a robust process involving both automated fusion of top-performing algorithms (e.g., nnU-Net, DeepScan) and meticulous manual refinement and approval by expert neuro-radiologists [25]. The annotated sub-regions are:

- Enhancing Tumor (ET): The gadolinium-enhancing portion of the tumor, indicating active, vascularized regions.

- Necrotic Core (NCR): The central non-enhancing area of the tumor composed of dead tissue.

- Peritumoral Edema (ED): The surrounding swollen brain tissue, which includes both vasogenic edema and infiltrating tumor cells.

This consistent, multi-region annotation strategy has been instrumental in moving the field beyond simple whole-tumor segmentation towards more clinically relevant, fine-grained analysis.

The MICCAI Challenges Framework

The MICCAI challenges provide a structured, competitive environment for benchmarking algorithmic solutions to well-defined problems in medical image computing. The BraTS challenge is a prominent example within this ecosystem.

Organizational Structure and Quality Assurance

MICCAI has implemented a rigorous process to ensure the quality and impact of its challenges. A key innovation is the challenge registration system, where the complete design of an accepted challenge must be published online before it begins, promoting transparency and thoughtful design [26] [27]. Recent initiatives like the "Lighthouse Challenges" further incentivize quality by spotlighting challenges that demonstrate excellence in design, data quality, and strong clinical collaboration [26] [28]. The BraTS 2025 challenge has been selected for this prestigious status, underscoring its high impact and quality [26].

BraTS Challenge Tasks and Evaluation

The BraTS challenge has evolved to include multiple tasks that address critical clinical problems. The core task remains the segmentation of the three intra-tumoral sub-regions (ET, NCR, ED) from the four standard MRI inputs. However, ancillary tasks like the Brain MR Image Synthesis Benchmark (BraSyn) have been introduced to address practical issues such as missing MRI sequences in clinical practice [25]. The evaluation of submitted algorithms is comprehensive and employs a suite of well-established metrics:

- Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC): A spatial overlap index, the primary metric for segmentation accuracy.

- Hausdorff Distance (HD): A boundary distance metric, evaluating the precision of segmentation contours.

- Sensitivity and Specificity: Measuring the true positive and true negative rates, respectively.

- Structural Similarity Index Measure (SSIM): Used in synthesis tasks to evaluate the perceptual quality of generated images [25].

Ranking is typically based on a weighted aggregate of these metrics, ensuring a balanced assessment of different aspects of performance.

Experimental Protocols for Benchmark Participation

Engaging with the BraTS benchmark requires a systematic approach. The following workflow and protocol outline the key steps for effective participation.

Diagram 1: BraTS benchmark participation workflow

Protocol: Model Development and Evaluation on BraTS

Objective: To train and validate a deep learning model for brain tumor sub-region segmentation using the official BraTS dataset and evaluation framework.

Materials:

- Hardware: A high-performance computing workstation with one or more modern GPUs (e.g., NVIDIA A100, RTX 4090) with at least 16GB VRAM.

- Software: Python (v3.8+), PyTorch or TensorFlow, and libraries for medical image processing (e.g., NiBabel, SimpleITK).

Procedure:

Data Acquisition and Licensing:

- Access the BraTS dataset via its official platform (e.g., The Cancer Imaging Archive - TCIA). Complete any required registration or data usage agreements.

- For BraTS 2023-2025, the dataset includes multi-parametric MRI scans and ground truth annotations for training and validation.

Data Preprocessing:

- The BraTS data is already pre-processed, including co-registration to the SRI24 template, resampling to 1 mm³ isotropic resolution, and skull-stripping [25].

- Perform additional intensity normalization (e.g., z-score normalization per modality or whole-volume normalization) to ensure consistent input scales.

- Implement data augmentation techniques to improve model robustness. Common strategies include random rotations (±10°), flipping, scaling (0.9-1.1x), and elastic deformations.

Model Selection and Training:

- Architecture Choice: Select a proven backbone architecture. The nnU-Net framework, which automatically configures a U-Net-based pipeline, has consistently emerged as a top performer in BraTS challenges and is highly recommended as a strong baseline [29]. Other advanced architectures include ensemble models integrating transformers and attention mechanisms (e.g., GAME-Net) [30].

- Implementation: Configure the model to accept four input channels (T1, T1Gd, T2, FLAIR) and output three segmentation maps (ET, NCR, ED).

- Loss Function: Use a combination of Dice loss and cross-entropy loss to handle class imbalance.

- Training: Train the model using the official BraTS training set. Utilize 5-fold cross-validation to robustly assess performance and prevent overfitting. Monitor the loss on a held-out validation split.

Model Validation and Evaluation:

- Use the official BraTS validation set (if available for the challenge year) to generate predictions.

- Evaluate the predictions locally using the challenge's metrics (Dice, HD95) before submitting to the official server.

- Analyze failure cases, such as poor performance on small lesions or tumors adjacent to brain boundaries, to guide model refinement.

Submission and Benchmarking:

- Submit the segmentation results for the held-out test set to the official BraTS evaluation platform (e.g., via the Codabench or Grand Challenge platforms).

- The platform will compute the final ranking metrics against the private ground truth, providing a place on the public leaderboard.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Engaging with public benchmarks like BraTS requires a suite of software tools and data resources. The following table details the key components of the modern computational scientist's toolkit for automated tumor segmentation research.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for BraTS-based Segmentation Research

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to BraTS Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| BraTS Dataset | Data | Provides standardized, annotated multi-parametric MRI brain tumor data. | The fundamental benchmark for training, validation, and testing of segmentation models [24] [25]. |

| nnU-Net | Software Framework | Self-configuring deep learning framework for medical image segmentation. | The leading baseline and winning methodology in multiple BraTS challenges; provides an out-of-the-box solution [29]. |

| PyTorch / TensorFlow | Software Library | Open-source libraries for building and training deep learning models. | The foundational computing environment for implementing and experimenting with custom model architectures. |

| NiBabel / SimpleITK | Software Library | Libraries for reading, writing, and processing medical images (NIfTI format). | Essential for handling the 3D volumetric data provided by the BraTS dataset. |

| FeTS Tool / CaPTk | Software Platform | Open-source platforms for federated learning and quantitative radiomics analysis. | Useful for pre-processing and analyzing BraTS-compatible data; FeTS is used in the challenge evaluation [25]. |

| Generative Autoencoders & Attention Mechanisms | Algorithmic Component | Advanced DL components for feature learning and context aggregation. | Used in state-of-the-art models (e.g., GAME-Net) to boost segmentation accuracy beyond standard CNNs [30]. |

The BraTS dataset and MICCAI challenges exemplify the transformative power of public benchmarks in accelerating research in automated tumor segmentation. By providing a standardized, high-quality, and ever-evolving platform for evaluation, they have not only driven the performance of deep learning models to near-human levels but have also steered the community towards solving clinically relevant problems, such as handling missing data and ensuring generalizability. The structured protocols and toolkit provided here offer a pathway for researchers to engage with these resources effectively. As these benchmarks continue to evolve—embracing longitudinal data, diverse populations, and predictive tasks—they will undoubtedly remain at the forefront of translating algorithmic advances into tangible tools for precision medicine.

Current Research Trends and Gap Analysis in Automated Segmentation

Automated tumor segmentation using deep learning (DL) has emerged as a transformative technology in medical imaging, significantly impacting diagnosis, treatment planning, and therapeutic development. Current research demonstrates a rapid evolution from conventional convolutional neural networks (CNNs) toward sophisticated architectures incorporating attention mechanisms, transformer modules, and hybrid designs [31]. These advancements address critical clinical challenges including tumor heterogeneity, ambiguous boundaries, and the imperative for real-time processing in clinical workflows. The integration of these technologies into drug development pipelines enables more precise target volume delineation for radiotherapy, objective treatment response assessment, and quantitative biomarker extraction for clinical trials [29] [2]. This analysis examines the current state of automated segmentation research, providing structured comparisons of methodological approaches, quantitative performance benchmarks, detailed experimental protocols, and identification of persistent gaps requiring further investigation to achieve widespread clinical adoption.

Quantitative Analysis of Current Models and Performance

Performance Benchmarks Across Tumor Types

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Deep Learning Models for Tumor Segmentation

| Tumor Type | Model Architecture | Dataset | Key Metric | Performance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brain Tumor (13 types) | Darknet53 (Classification) | Institutional (203 subjects) | Accuracy | 98.3% | [13] |

| Brain Tumor | ResNet50 (Segmentation) | Institutional (203 subjects) | Mean Dice Score | 0.937 | [13] |

| Glioma | Various CNN/Transformer Hybrids | BraTS | Dice Score (Enhancing Tumor) | 0.82-0.90 | [32] [31] |

| Glioma | 2D-VNET++ with CBF | BraTS | Dice Score | 99.287 | [33] |

| Glioblastoma | nnU-Net | BraTS | Dice Score | >0.89 | [29] |

| Lung Cancer | 3D U-Net (iSeg) | Multicenter (1002 CTs) | Median Dice Score | 0.73 [IQR: 0.62-0.80] | [2] |

| Skin Cancer | Improved DeepLabV3+ with ResNet20 | ISIC-2018 | Dice Score | 94.63% | [34] |

Architectural Efficiency Analysis

Table 2: Model Complexity and Hardware Considerations

| Model Category | Representative Architectures | Parameter Efficiency | Computational Demand | Clinical Deployment Suitability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNN-Based | 3D U-Net, V-Net, SegNet | Moderate | Moderate | High (Well-established) |

| Pure Transformer | ViT, Swin Transformer | Low (High parameters) | Very High | Low (Resource-intensive) |

| Hybrid CNN-Transformer | TransUNet, UNet++ with Attention | Moderate to High | High | Medium (Emerging) |

| Lightweight CNN | Improved ResNet20, Light U-Net | High | Low | High (Edge devices) |

| Self-Configuring | nnU-Net | Adaptive | Adaptive | High (Multi-site) |

Recent comprehensive reviews evaluating over 80 state-of-the-art DL models reveal that while pure transformer architectures capture superior global context, they require substantial computational resources, creating deployment challenges in clinical environments with limited hardware capabilities [31]. Hybrid CNN-Transformer models strike a balance, leveraging convolutional layers for spatial feature extraction and self-attention mechanisms for long-range dependencies. The nnU-Net framework demonstrates particular clinical promise through its self-configuring capabilities that adapt to varying imaging protocols and institutional specifications [29].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Multi-Channel MRI Fusion Protocol for Brain Tumor Segmentation

Objective: To implement a DL pipeline for simultaneous brain tumor classification and segmentation using non-contrast T1-weighted (T1w) and T2-weighted (T2w) MRI sequences fused via RGB transformation.

Materials and Reagents:

- MRI datasets (e.g., BraTS 2012-2025 challenges, institutional datasets)

- Python 3.8+ with PyTorch/TensorFlow frameworks

- GPU acceleration (NVIDIA RTX 3000+ series recommended)

- Data augmentation libraries (Albumentations, TorchIO)

Methodology:

- Data Preprocessing:

- Convert DICOM images to NIfTI format for standardized processing

- Apply N4 bias field correction to address intensity inhomogeneity

- Normalize intensity values to zero mean and unit variance

- Coregister all sequences to a common spatial alignment

Multi-Channel Fusion:

- Stack T1w, T2w, and their linear average (T1w + T2w)/2 into three-channel RGB format

- This fusion enriches feature representation while maintaining non-contrast protocol compatibility [13]

Model Training Configuration:

- For classification: Implement Darknet53 with pretrained weights

- For segmentation: Utilize ResNet50-based FCN with deep supervision

- Loss function: Combined Dice and Cross-Entropy loss

- Optimizer: AdamW with learning rate 1e-4, weight decay 1e-5

- Batch size: 16 (adjusted based on GPU memory)

- Training duration: 200-300 epochs with early stopping

Performance Validation:

- Apply five-fold cross-validation to ensure robustness

- Evaluate using DSC, HD95, Sensitivity, and Specificity

- Compare against ground truth manual segmentation by expert radiologists

This protocol achieved a top classification accuracy of 98.3% and segmentation Dice score of 0.937, demonstrating the efficacy of multichannel fusion for non-contrast MRI analysis [13].

nnU-Net Framework for Glioblastoma Auto-Contouring in Radiotherapy

Objective: To automate the segmentation of glioblastoma (GBM) target volumes for radiotherapy treatment planning using the self-configuring nnU-Net framework.

Materials:

- Multimodal MRI: T1, T1-CE, T2, FLAIR sequences

- Radiotherapy contouring workstations

- Approved software: NeuroQuant or Raidionics for clinical validation

Methodology:

- Data Preparation and Preprocessing:

- Acquire multi-parametric MRI (mpMRI) according to BraTS protocol specifications

- Manually contour ground truth volumes (GTV, CTV, PTV) following RTOG guidelines

- Convert all images to 1mm³ isotropic resolution using spline interpolation

- Apply intensity normalization through z-score transformation

nnU-Net Configuration:

- Implement both 2D and 3D nnU-Net configurations

- Enable automatic preprocessing configuration and patch size optimization

- Utilize default training parameters with five-fold cross-validation

- Employ Dice loss for optimization with exponential learning rate decay

Training Protocol:

- Training duration: 1000 epochs per fold

- Batch size: Automatically determined based on GPU memory

- Data augmentation: Rigid transformations, elastic deformations, gamma corrections

- Implement extensive online augmentation to improve model generalizability

Clinical Validation:

- Quantitative analysis: Compute DSC, HD95, and relative volume difference

- Qualitative assessment: Independent review by ≥2 radiation oncologists

- Statistical comparison against inter-observer variability among clinicians

This approach has demonstrated superior segmentation accuracy for GBM target volumes, with nnU-Net emerging as the strongest architecture due to its self-configuring capabilities and adaptability to different imaging modalities [29].

Visualization of Research Workflows

Multi-Channel MRI Segmentation Pipeline

(Multi-Channel MRI Segmentation Workflow)

nnU-Net Self-Configuring Framework

(nnU-Net Self-Configuring Framework)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for Automated Segmentation Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Solutions | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Public Datasets | BraTS (2012-2025) | Benchmarking glioma segmentation | Algorithm validation across institutions |

| ISIC (2018-2020) | Skin lesion analysis | Dermatological segmentation development | |

| Software Frameworks | PyTorch, TensorFlow | DL model development | Flexible research prototyping |

| nnU-Net | Automated configuration | Baseline model establishment | |

| Clinical Validation Tools | NeuroQuant, Raidionics | Clinical segmentation assessment | Translational research bridge |

| ITK-SNAP, 3D Slicer | Manual annotation & visualization | Ground truth generation | |

| Hardware Accelerators | NVIDIA GPUs (RTX 3000/4000+) | Training acceleration | High-throughput experimentation |

| Google TPUs | Transformer model optimization | Large-scale model training |

Current Challenges and Research Gaps

Despite significant advances, automated tumor segmentation faces several persistent challenges that limit clinical adoption. Technical limitations include inadequate performance on boundary delineation, with encoder-decoder architectures sometimes producing jagged or inaccurate boundaries despite high overall Dice scores [33]. Class imbalance remains problematic, as models frequently prioritize dominant classes like tumor cores while underperforming on smaller but clinically critical regions like infiltrating edges. Clinical translation barriers include insufficient model interpretability, with "black box" predictions creating clinician skepticism [31]. Limited generalizability across diverse patient populations, imaging protocols, and institutional equipment presents additional hurdles. Computational constraints are particularly relevant for transformer-based architectures, which require substantial resources that may be unavailable in resource-limited clinical settings [31].

Promising research directions include the development of explainable AI (XAI) techniques like integrated gradients and class activation mapping to enhance model transparency [2]. Weakly supervised approaches that reduce annotation burden through partial labeling and innovative loss functions show potential for addressing data scarcity. Federated learning frameworks enable multi-institutional collaboration while preserving data privacy, crucial for developing robust models without sharing sensitive patient information [13]. Continued refinement of attention mechanisms and transformer modules will likely further improve segmentation accuracy, particularly for heterogeneous tumor subregions.

Automated tumor segmentation has progressed dramatically from basic CNN architectures to sophisticated frameworks incorporating multi-modal fusion, self-configuration, and attention mechanisms. Current models demonstrate performance approaching or exceeding human inter-observer variability for well-defined segmentation tasks, with top-performing approaches achieving Dice scores exceeding 0.95 in controlled conditions. The integration of these technologies into drug development pipelines offers unprecedented opportunities for objective treatment response assessment and personalized therapy planning. However, bridging the gap between technical performance and clinical utility requires addressing persistent challenges in interpretability, generalizability, and computational efficiency. Future research prioritizing these translational considerations will accelerate the adoption of automated segmentation tools, ultimately enhancing precision medicine across oncology applications.

Deep Learning Architectures for Tumor Segmentation: Implementations and Real-World Applications

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have become a cornerstone in the field of medical image analysis, particularly for the critical task of automated tumor segmentation. In neuro-oncology and beyond, precise delineation of tumor boundaries from medical images such as Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) and Computed Tomography (CT) is essential for diagnosis, treatment planning, and monitoring disease progression [35] [36]. CNN-based models address the significant limitations of manual segmentation, which is time-consuming, subject to inter-observer variability, and impractical for large-scale studies [36]. These deep learning models leverage their ability to automatically learn hierarchical features directly from image data, capturing complex patterns and textures that distinguish pathological tissues from healthy structures [35] [37]. This document examines the predominant CNN architectures deployed for tumor segmentation, evaluates their respective strengths and limitations, and provides detailed experimental protocols for researchers implementing these methodologies within the context of a broader thesis on automated tumor segmentation using deep learning.

Core CNN Architectures for Tumor Segmentation

Predominant Model Architectures

The landscape of CNN-based tumor segmentation is dominated by several key architectures, each with distinct structural characteristics and applications.

U-Net and its Variants: The U-Net architecture, introduced by Ronneberger et al., has emerged as arguably the most influential CNN architecture for biomedical image segmentation [37]. Its symmetrical encoder-decoder structure with skip connections allows it to capture both context and precise localization, making it exceptionally suitable for tumor segmentation where boundary delineation is critical [35] [38]. The encoder path progressively downsamples the input image, extracting increasingly abstract feature representations, while the decoder path upsamples these features to reconstruct the segmentation map at the original input resolution. The skip connections bridge corresponding layers in the encoder and decoder, preserving spatial information that would otherwise be lost during downsampling [37]. This architecture has spawned numerous variants including nnU-Net, which introduces self-configuring capabilities that automatically adapt to specific dataset properties, and has demonstrated superior segmentation accuracy in benchmarks like the Brain Tumor Segmentation (BraTS) challenge [38].

ResNet (Residual Neural Network): ResNet addresses the degradation problem that occurs in very deep networks through the use of residual blocks and skip connections [39]. These connections enable the network to learn identity functions, allowing gradients to flow directly through the network and facilitating the training of substantially deeper architectures. In tumor segmentation, ResNet is often utilized as the encoder backbone within more complex segmentation frameworks, where its depth and representational power excel at feature extraction [35] [39].

V-Net: Extending the U-Net concept to volumetric data, V-Net employs 3D convolutional operations throughout its architecture, making it particularly effective for segmenting tumors in 3D medical image volumes such as MRI and CT scans [35]. By processing entire volumetric contexts simultaneously, V-Net can capture spatial relationships in all three dimensions, which is crucial for accurately assessing tumor morphology and volume.

Attention-Enhanced CNNs: Recent architectural innovations incorporate attention mechanisms to enhance model performance. The Global Attention Mechanism (GAM) simultaneously captures cross-dimensional interactions across channel, spatial width, and spatial height dimensions, enabling the model to focus on diagnostically relevant regions while suppressing less informative features [40]. Similarly, the Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) sequentially infers attention maps along both channel and spatial dimensions, and has been successfully integrated into architectures like YOLOv7 for improved brain tumor detection [41].

Architectural Comparison

Table 1: Comparison of Key CNN Architectures for Tumor Segmentation

| Architecture | Core Innovation | Dimensionality | Key Strength | Common Tumor Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| U-Net | Skip connections in encoder-decoder structure | 2D/3D | Excellent balance between context capture and localization precision | Brain tumors (gliomas, glioblastoma), various abdominal tumors |

| ResNet | Residual blocks with skip connections | 2D/3D | Enables training of very deep networks without degradation; powerful feature extraction | Often used as encoder in segmentation networks; classification tasks |

| V-Net | Volumetric convolution with residual connections | 3D | Native handling of 3D spatial context; improved volumetric consistency | Prostate cancer, brain tumors, liver tumors |

| nnU-Net | Self-configuring framework | 2D/3D | Automatically adapts to dataset characteristics; state-of-the-art performance | Multiple cancer types; winner of various medical segmentation challenges |

| Attention CNNs (e.g., GAM, CBAM) | Cross-dimensional attention mechanisms | 2D/3D | Enhanced focus on salient regions; improved feature representation | Brain tumors, oral squamous cell carcinoma, small tumor detection |

Performance Analysis and Quantitative Comparison

Segmentation Accuracy Across Architectures

CNN-based models have demonstrated remarkable performance in tumor segmentation tasks across various cancer types and imaging modalities. Evaluation metrics such as the Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC), Intersection over Union (IoU), and accuracy provide standardized measures for comparing model effectiveness.

Brain Tumor Segmentation: For glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) and other glioma types, CNN architectures have achieved exceptional segmentation accuracy. U-Net and its variants consistently achieve DSC scores exceeding 0.90 on benchmark datasets like BraTS [35]. The nnU-Net architecture has emerged as particularly powerful, offering superior segmentation accuracy due to its self-configuring capabilities and adaptability to different imaging modalities [38]. In practical clinical applications for radiotherapy planning, models like SegNet have reported DSC values of 89.60% with Hausdorff Distance of 1.49 mm when segmenting GBM using multimodal MRI data from the BraTS 2019 dataset [38]. Mask R-CNN, another CNN variant, has demonstrated promise for real-time tumor monitoring during radiotherapy, achieving DSC values of 0.8 for tumor volume delineation from daily MR images [38].

Beyond Brain Tumors: CNN performance remains strong across diverse cancer types. For oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC), novel architectures like gamUnet that integrate Global Attention Mechanisms have significantly outperformed conventional models in segmentation accuracy [40]. In classification tasks, specialized networks like CNN-TumorNet have achieved remarkable accuracy rates up to 99% in distinguishing tumor from non-tumor MRI scans [42].

Table 2: Performance Metrics of CNN Models Across Cancer Types

| Cancer Type | Architecture | Dataset | Key Metric | Performance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brain Tumors (GBM) | U-Net variants | BraTS | Dice Score | >0.90 | [35] |

| Brain Tumors (GBM) | SegNet | BraTS 2019 | Dice Score | 89.60% | [38] |

| Brain Tumors (GBM) | Mask R-CNN | Clinical daily MRI | Dice Score | 0.80 | [38] |

| Brain Tumors | nnU-Net | BraTS | Dice Score | Superior to benchmarks | [38] |

| Brain Tumors | YOLOv7 with CBAM | Curated dataset | Accuracy | 99.5% | [41] |

| Oral Cancer (OSCC) | gamUnet (GAM-enhanced) | Public datasets | Accuracy | Significant improvement over baselines | [40] |

| Various Cancers | CNN-TumorNet | Brain tumor MRI | Classification Accuracy | 99% | [42] |

Limitations and Challenges

Despite their impressive performance, CNN-based tumor segmentation approaches face several significant limitations:

Data Dependency and Annotation Costs: CNNs typically require large volumes of high-quality annotated images for effective training [39]. The process of medical image annotation is particularly costly and time-consuming, requiring specialized expertise from radiologists or pathologists [39]. This challenge is exacerbated for rare tumor types where collecting sufficient training data is difficult.

Computational Demands: Especially for 3D architectures like V-Net and processing high-resolution medical images, CNNs require substantial computational resources and memory [35]. This can limit their practical deployment in clinical settings with resource constraints or requirements for real-time processing.

Generalization Across Domains: Models trained on data from specific scanners, protocols, or institutions often experience performance degradation when applied to images from different sources [35] [43]. This lack of robustness to domain shifts remains a significant barrier to widespread clinical adoption.

Interpretability and Trust: The "black-box" nature of deep CNN decisions complicates clinical acceptance, as healthcare professionals require understanding of the rationale behind segmentation results [42]. While explainable AI approaches like LIME are being explored to address this, interpretability remains an active research challenge.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized Training Pipeline

Implementing CNN models for tumor segmentation requires a systematic approach to data preparation, model configuration, and training. The following protocol outlines a standardized pipeline adaptable to various tumor types and imaging modalities.

Data Preprocessing:

- Image Resizing: Standardize all input images to uniform dimensions compatible with the network architecture. For 2D CNNs, resize to square dimensions (e.g., 256×256 or 512×512 pixels); for 3D CNNs, use isotropic voxel sizes or standard volumetric dimensions [42].

- Intensity Normalization: Apply z-score normalization to scale intensity values across all images, reducing scanner-specific variations. Calculate mean and standard deviation from the training set and apply identical transformation to validation and test sets.

- Data Augmentation: Generate synthetic training examples through real-time augmentation during training. Recommended transformations include: random rotations (±15°), random scaling (0.85-1.15x), random flipping (horizontal/vertical), elastic deformations, and brightness/contrast adjustments [36].

- Patch Extraction: For large images or memory constraints, extract random patches during training (e.g., 128×128×128 for 3D volumes). Ensure adequate sampling of both tumor and non-tumor regions through class-balanced sampling.

Model Configuration:

- Architecture Selection: Choose base architecture based on task requirements: U-Net for general segmentation, V-Net for 3D volumes, ResNet-based encoders for transfer learning, or attention-enhanced variants for complex boundaries.

- Loss Function: Utilize Dice loss or a combination of Dice loss and cross-entropy loss to handle class imbalance between tumor and background pixels [37]. The Dice loss function is defined as: $DL = 1 - \frac{2 \times |X \cap Y| + \epsilon}{|X| + |Y| + \epsilon}$ where X is the predicted segmentation, Y is the ground truth, and ε is a smoothing factor.

- Optimizer: Employ Adam optimizer with initial learning rate of 1e-4, β₁=0.9, and β₂=0.999. Implement learning rate reduction on plateau with factor of 0.5 and patience of 10 epochs.