AI in Anticancer Drug Discovery: A Comparative Analysis of Models, Applications, and Clinical Impact

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of artificial intelligence (AI) models transforming anticancer drug discovery.

AI in Anticancer Drug Discovery: A Comparative Analysis of Models, Applications, and Clinical Impact

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of artificial intelligence (AI) models transforming anticancer drug discovery. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational AI technologies—from machine learning to generative models—and their specific methodologies in target identification, lead optimization, and biomarker discovery. The analysis critically examines real-world applications and performance metrics of leading AI-driven platforms, addresses key challenges in data quality and model interpretability, and evaluates validation strategies through clinical progress and in silico trials. By synthesizing current evidence and future directions, this review serves as a strategic guide for leveraging AI to accelerate the development of precision oncology therapeutics.

The AI Revolution in Oncology: Core Technologies and the Urgent Need for Innovation

The Global Cancer Burden and the High Cost of Traditional Drug Discovery

Cancer remains one of the most pressing public health challenges of our time. According to the Global Burden of Disease 2023 study, cancer was the second leading cause of death globally in 2023, with over 10 million deaths annually and more than 18 million new incident cases contributing to 271 million healthy life years lost [1]. Forecasts suggest a dramatic increase, with over 30 million new cases and 18 million deaths projected for 2050 – representing a 60% increase in cases and nearly 75% increase in deaths compared to 2024 figures [1]. This escalating burden disproportionately affects low- and middle-income countries, where approximately 60% of cases and deaths already occur [1].

Confronting this growing epidemic is a pharmaceutical development pipeline characterized by extraordinary costs and high failure rates. The process of bringing a new drug to market traditionally takes 10-15 years and ends successfully less than 12% of the time [2]. In oncology specifically, success rates sit well below the 10% average, with an estimated 97% of new cancer drugs failing clinical trials [3]. The financial implications are staggering, with companies spending up to $375 million on clinical trials per drug [4], and total development costs reaching billions when accounting for failures.

This article provides a comparative analysis of how artificial intelligence (AI) platforms are transforming anticancer drug discovery by addressing these dual challenges of global cancer burden and development inefficiencies.

The Global Landscape of Cancer Burden

The geographical and demographic distribution of cancer reveals significant disparities in incidence, mortality, and survivorship. In the United States, despite a 34% decline in age-adjusted overall cancer mortality between 1991 and 2023 – averting more than 4.5 million deaths – an estimated 2,041,910 new cases and 618,120 deaths occurred in 2025 [5]. The 5-year relative survival rate for all cancers combined has improved from 49% (1975-1977) to 70% (2015-2021), yet significant disparities persist among racial and ethnic minority groups and other medically underserved populations [5].

Table 1: Global Cancer Burden: Current Statistics and Projections

| Metric | 2023-2025 Figures | 2050 Projections | Key Changes |

|---|---|---|---|

| New Annual Cases | 18+ million [1] | 30+ million [1] | 60% increase |

| Annual Deaths | 10+ million [1] | 18+ million [1] | 75% increase |

| Cancer Survivors | 18.6 million in US [5] | 22+ million in US [5] | Growing survivor population |

| Disparities | NH Black individuals have highest cancer mortality rate [5] | Greater relative increase anticipated in low-middle income countries [1] | Widening inequities |

The types and distribution of cancers vary significantly by age. Childhood cancers are dominated by leukemias, lymphomas, and brain cancers, while adults experience a shift toward carcinomas such as breast, lung, and gastrointestinal cancers [1]. In 2023, breast and lung cancer represented the cancers with the greatest number of cases, while lung and colorectal cancer were the leading causes of cancer deaths [1]. The growing survivor population – now approximately 5.5% of the US population – creates new challenges for long-term care and monitoring [5].

The Traditional Drug Discovery Paradigm: Costs and Limitations

Financial and Temporal Challenges

Conventional drug discovery represents one of the most costly and time-intensive endeavors in modern science. Recent analyses reveal that the median direct R&D cost for drug development is $150 million, much lower than the mean cost of $369 million, indicating significant skewing by high-cost outliers [6]. After adjusting for capital costs and failures, the median R&D cost rises to $708 million across 38 drugs examined, with the average cost reaching $1.3 billion [6]. Notably, excluding just two high-cost outliers reduces the average from $1.3 billion to $950 million, underscoring how extreme cases distort perceptions of typical development costs [6].

The temporal dimensions are equally concerning. The traditional pipeline requires over 12 years for a drug to move from preclinical testing to final approval [4], with the discovery and preclinical phases alone typically consuming ~5 years before a candidate even enters human trials [7]. This extended timeline represents missed therapeutic opportunities for current patients and substantial financial carrying costs for developers.

Scientific and Methodological Limitations

Beyond financial metrics, traditional approaches face fundamental scientific constraints in addressing cancer complexity. The high failure rate of approximately 90% for oncology drugs during clinical development [8] stems from several factors:

- Tumor heterogeneity: Treatments effective in one patient subset often fail in others

- Resistance mechanisms: Both intrinsic and acquired resistance limit long-term efficacy

- Complex microenvironment: Drug response is influenced by immune system interactions, epigenetic factors, and stromal components

- Inadequate models: Traditional cell lines and animal models often poorly predict human responses

Conventional methodologies like high-throughput screening rely on iterative synthesis and testing – a serial process that is both slow and limited in its ability to explore chemical space comprehensively [8]. Furthermore, the compartmentalized nature of traditional research – where biology, chemistry, screening, and toxicology operate in silos – creates handoff delays and data fragmentation that impede innovation [2].

AI Platforms in Anticancer Drug Discovery: A Comparative Analysis

Artificial intelligence has progressed from experimental curiosity to clinical utility in drug discovery, with AI-designed therapeutics now in human trials across diverse therapeutic areas, including oncology [7]. Multiple AI-derived small-molecule drug candidates have reached Phase I trials in a fraction of the typical 5+ years needed for traditional discovery and preclinical work [7]. This section compares the approaches, capabilities, and validation status of leading AI platforms.

Comparative Analysis of Leading AI Platforms

Table 2: Leading AI-Driven Drug Discovery Platforms: Approaches and Capabilities

| Platform/Company | Core AI Approach | Reported Efficiency Gains | Clinical-Stage Candidates | Key Differentiators |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exscientia | Generative chemistry + "Centaur Chemist" approach [7] | ~70% faster design cycles; 10x fewer synthesized compounds [7] | 8 clinical compounds designed (including oncology candidates) [7] | Patient-derived biology integration; automated precision chemistry [7] |

| Insilico Medicine | Generative AI for target discovery and molecular design [7] | Target-to-phase I in 18 months for IPF drug [7] | ISM001-055 (TNK inhibitor) in Phase IIa for IPF [7] | End-to-end generative AI platform; novel target identification [7] |

| Recursion | Phenomics-first systems + cellular microscopy [7] | Not specified in results | Multiple candidates in clinical development [7] | Massive biological dataset (≥10PB); phenomic screening at scale [7] |

| BenevolentAI | Knowledge-graph repurposing and target discovery [7] | Not specified in results | Several candidates in clinical stages [7] | Knowledge graphs mining scientific literature and datasets [7] |

| Schrödinger | Physics-enabled + machine learning design [7] | Not specified in results | TAK-279 (TYK2 inhibitor) in Phase III [7] | Physics-based simulation combined with machine learning [7] |

Experimental Protocols and Validation

AI platforms employ distinct experimental protocols to validate their computational predictions:

Exscientia's Integrated Workflow: The platform combines algorithmic design with experimental validation through a closed-loop system. AI-designed compounds are synthesized and tested on patient-derived tumor samples through its Allcyte acquisition, ensuring translational relevance [7]. The system uses deep learning models trained on vast chemical libraries to propose structures satisfying target product profiles for potency, selectivity, and ADME properties [7].

Insilico Medicine's Generative Approach: The company reported a comprehensive case study where its platform identified a novel target and generated a preclinical candidate for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in under 18 months [7]. The approach used generative adversarial networks (GANs) and reinforcement learning to create novel molecular structures optimized for specific therapeutic properties [8].

Recursion's Phenomic Screening: The platform employs high-content cellular microscopy and automated phenotyping to generate massive biological datasets, which are then analyzed using machine learning to identify novel drug-target relationships [7]. This approach aims to map how chemical perturbations affect cellular morphology across diverse disease models.

Key Research Reagent Solutions in AI-Enhanced Discovery

The implementation of AI-driven discovery relies on specialized research reagents and platforms that enable high-quality data generation and validation. The following table details essential solutions used across featured experiments and platforms.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for AI-Enhanced Drug Discovery

| Research Solution | Function | Example Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| 3D Cell Culture/Organoids | Provides human-relevant tissue models for more predictive efficacy and safety testing [9] | mo:re's MO:BOT platform automates seeding and quality control of organoids, improving reproducibility [9] |

| Automated Liquid Handling | Enables high-throughput, reproducible screening and compound management [9] | Tecan's Veya system and SPT Labtech's firefly+ platform provide walk-up automation for complex workflows [9] |

| Multi-omics Data Platforms | Integrates genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data for AI analysis [8] | Sonrai's Discovery platform layers imaging, multi-omic, and clinical data in a single analytical framework [9] |

| Sample Management Software | Manages compound and biological sample libraries with complete traceability [9] | Cenevo's Mosaic software (from Titian) provides sample management for large pharmaceutical companies [9] |

| Predictive ADMET Platforms | Uses AI to forecast absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity properties [3] | Multiple AI platforms incorporate in silico ADMET prediction to prioritize compounds with desirable drug-like properties [3] |

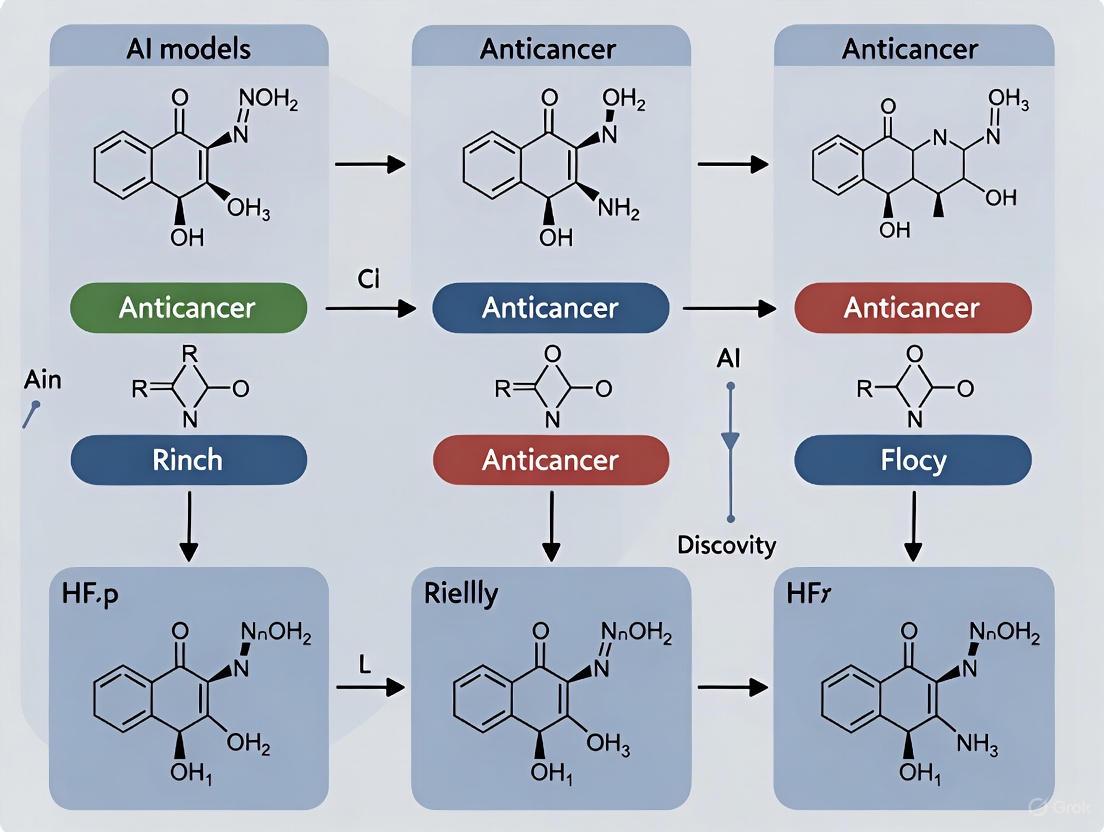

Visualization of AI-Driven Drug Discovery Workflows

AI-Driven Discovery Workflow

Traditional vs AI-Accelerated Discovery Timeline

The integration of AI into anticancer drug discovery represents a paradigm shift in how we approach one of healthcare's most complex challenges. The comparative analysis presented demonstrates that AI platforms can potentially compress discovery timelines from years to months, reduce development costs by minimizing late-stage failures, and address the biological complexity of cancer through multi-modal data integration.

While no AI-discovered drug has yet received full regulatory approval for cancer, the over 75 AI-derived molecules that had reached clinical stages by the end of 2024 signal a rapidly maturing field [7]. The diversity of approaches – from generative chemistry to phenomic screening and knowledge-graph repurposing – provides multiple pathways for innovation.

The ultimate validation of AI's promise will come when these platforms deliver approved therapies that meaningfully impact the global cancer burden. As the field progresses, success will depend on continued refinement of AI models, expansion of high-quality biological datasets, and thoughtful integration of human expertise with computational power. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding these evolving platforms is no longer optional – it is essential for contributing to the next generation of cancer breakthroughs.

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) has fundamentally transformed anticancer drug discovery, offering powerful solutions to overcome the high costs, lengthy timelines, and low success rates that have long challenged traditional approaches. With cancer projected to affect 29.9 million people annually by 2040 and drug development success rates sitting well below 10% for oncologic therapies, the pharmaceutical industry urgently requires innovative methodologies [10] [3]. AI technologies—particularly machine learning (ML), deep learning (DL), and neural networks (NN)—have emerged as transformative tools that can process vast biological datasets, identify complex patterns, and make autonomous decisions to accelerate the identification of novel therapeutic targets and drug candidates [3] [11]. This comparative analysis examines the technical capabilities, performance metrics, and specific applications of these AI subtypes within anticancer drug discovery, providing researchers with an evidence-based framework for selecting appropriate methodologies for their investigative needs.

Methodological Foundations and Definitions

Conceptual Relationships and Technical Distinctions

AI encompasses computer systems designed to perform tasks typically requiring human intelligence. Within this broad field, machine learning represents a specialized subset that enables systems to learn and improve from experience without explicit programming [3]. Deep learning operates as a further refinement of machine learning, utilizing multi-layered neural networks to process data with increasing levels of abstraction [12]. The conceptual relationship between these domains is thus hierarchical: deep learning is a specialized subset of machine learning, which in turn constitutes a subset of artificial intelligence.

Machine Learning employs statistical algorithms that can identify patterns within data and make predictions or decisions based on those patterns. These algorithms improve their performance as they are exposed to more data over time. In anticancer drug discovery, ML techniques are particularly valuable for tasks such as quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) modeling, drug-target interaction prediction, and absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) profiling [3] [10].

Deep Learning utilizes artificial neural networks with multiple processing layers (hence "deep") to learn hierarchical representations of data. Unlike traditional ML, DL algorithms can automatically discover the features needed for classification from raw data, reducing the need for manual feature engineering [12]. This capability is particularly valuable for processing complex biological structures and high-dimensional omics data in cancer research.

Neural Networks constitute the architectural foundation of deep learning, consisting of interconnected nodes organized in layers that mimic the simplified structure of biological brains. Specialized neural network architectures have been developed for specific drug discovery applications, including Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) for molecular structure analysis and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) for image-based profiling [13] [14].

Experimental Evaluation Framework

To objectively compare the performance of different AI approaches in anticancer drug discovery, researchers have established standardized experimental protocols centered on key predictive tasks:

Drug Sensitivity Prediction evaluates how accurately AI models can forecast cancer cell response to therapeutic compounds. The standard methodology involves training models on databases such as the Cancer Drug Sensitivity Genomics (GDSC) or Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE), which contain drug response measurements (typically IC50 or AUC values) for hundreds of cell lines and compounds [14] [15]. Models receive molecular features of drugs (e.g., chemical structures encoded as fingerprints or graphs) and genomic features of cancer cell lines (e.g., gene expression, mutations, copy number variations), then predict sensitivity values for unseen cell line-drug pairs.

Virtual Screening assesses the capability of AI models to identify active compounds from large chemical libraries. Experimental protocols typically use known active and inactive compounds against specific cancer targets for training, then evaluate model performance on hold-out test sets using metrics like enrichment factors and area under the receiver operating characteristic curve [10].

Target Identification measures how effectively AI algorithms can pinpoint novel therapeutic targets from biological networks. Methodologies often involve constructing protein-protein interaction or gene regulatory networks, then applying network-based algorithms or ML approaches to identify crucial nodes whose perturbation would disrupt cancer pathways [16].

Table 1: Standard Experimental Datasets for AI Model Evaluation in Anticancer Drug Discovery

| Dataset | Source | Content Description | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| GDSC | https://www.cancerrxgene.org | Drug sensitivity data for ~300 cancer cell lines and ~700 compounds | Drug response prediction |

| CCLE | https://depmap.org/portal/download/all | Genomic characterization of ~1000 cancer cell lines | Multi-omics integration |

| TCGA | https://www.cancer.gov/ccg/research/genome-sequencing/tcga | Multi-omics data from ~11,000 cancer patients | Target identification |

| PubChem | https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov | Chemical information for ~100 million compounds | Virtual screening |

Comparative Performance Analysis

Quantitative Benchmarking Across AI Methodologies

Direct comparisons of AI approaches across standardized experimental frameworks reveal distinct performance advantages for specific tasks in anticancer drug discovery. The following table synthesizes performance metrics reported across multiple studies:

Table 2: Performance Comparison of AI Methodologies in Anticancer Drug Discovery Tasks

| AI Methodology | Drug Sensitivity Prediction (R²) | Virtual Screening (AUC-ROC) | Target Identification (Precision) | Interpretability | Computational Demand |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional ML | 0.62-0.71 [15] | 0.75-0.82 [10] | 0.68-0.74 [17] | Medium | Low |

| Deep Learning (CNN) | 0.69-0.76 [14] | 0.81-0.87 [10] | 0.71-0.77 [16] | Low | Medium |

| Graph Neural Networks | 0.73-0.79 [14] [13] | 0.85-0.91 [13] | 0.76-0.82 [16] | Medium-High | High |

| Interpretable DL (VNN) | 0.70-0.75 [15] | 0.79-0.84 [15] | 0.80-0.85 [15] | High | Medium |

The CatBoost algorithm (ML approach) achieved particularly high performance in classifying patients based on molecular profiles and predicting drug responses, reaching 98.6% accuracy, 0.984 specificity, and 0.979 sensitivity in colon cancer drug sensitivity prediction [17]. Similarly, the ABF-CatBoost integration demonstrated an F1-score of 0.978, outperforming traditional ML models like Support Vector Machine and Random Forest [17].

For structure-based tasks, Graph Neural Networks have shown remarkable efficacy by accurately modeling molecular structures and interactions with binding targets. GNN-driven innovations have significantly sped up drug discovery through improved predictive accuracy, reduced development costs, and fewer late-stage failures [13]. The eXplainable Graph-based Drug Response Prediction (XGDP) approach, which leverages GNNs to represent drugs as molecular graphs, has demonstrated enhanced prediction accuracy compared to pioneering works while simultaneously identifying salient functional groups of drugs and their interactions with significant cancer cell genes [14].

Task-Specific Applications and Performance

Target Identification and Validation Network-based AI algorithms excel in identifying novel anticancer targets by mapping biological networks and charting intricate molecular circuits. These approaches can pinpoint previously undiscovered interactions within cell systems, revealing new potential therapeutic targets [11] [16]. For example, AI-driven analysis of protein-protein interaction networks has identified indispensable proteins that affect network controllability, with research across 1,547 cancer patients revealing 56 indispensable genes in nine cancers—46 of which were newly associated with cancer [16].

Drug Sensitivity Prediction Deep learning models have demonstrated exceptional capability in predicting drug sensitivity and resistance across various cancer types, enabling more personalized treatment approaches [11]. The DrugGene model, which integrates gene expression, mutation, and copy number variation data with drug chemical characteristics, outperforms existing prediction methods by using a hierarchical structure of biological subsystems to form a visual neural network (VNN) [15]. This interpretable approach achieves higher accuracy while learning reaction mechanisms between anticancer drugs and cell lines.

Multi-Target Drug Discovery AI has demonstrated particular strength in designing compounds that can inhibit multiple targets simultaneously. The POLYpharmacology Generative Optimization Network (POLYGON) represents a significant advancement in this area, using deep learning to create multi-target compounds [11]. Similarly, models like Drug Ranking Using ML (DRUML) can rank drugs based on large-scale "omics" data and predict their efficacy performance across diverse cancer types [11].

Drug Repurposing AI approaches have accelerated drug repurposing by predicting new therapeutic applications for existing drugs. Advanced tools like PockDrug predict "druggable" pockets on proteins, while AlphaFold and other structural biology models refine these predictions, helping identify new applications for existing drugs in cancer treatment [11]. These approaches leverage known safety profiles of approved drugs to potentially reduce development timelines.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Graph Neural Network for Drug Response Prediction

The eXplainable Graph-based Drug Response Prediction (XGDP) protocol exemplifies a sophisticated GNN approach for predicting anticancer drug sensitivity [14]:

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

- Input Data: Drug response data (IC50 values) from GDSC database; gene expression data from CCLE; drug structures from PubChem.

- Drug Representation: Convert SMILES strings to molecular graphs using RDKit library, with atoms as nodes and chemical bonds as edges.

- Node Features: Compute using circular atomic feature algorithm incorporating seven Daylight atomic invariants: number of immediate non-hydrogen neighbors, valence minus hydrogen count, atomic number, atomic mass, atomic charge, number of attached hydrogens, and aromaticity.

- Cell Line Representation: Process gene expression profiles using a Convolutional Neural Network module, reducing dimensionality to 956 landmark genes based on LINCS L1000 research.

Model Architecture

- GNN Module: Learns latent features of drugs represented as molecular graphs using novel node and edge features adapted from Extended Connectivity Fingerprints (ECFPs).

- CNN Module: Processes gene expression data from cancer cell lines to extract relevant features.

- Cross-Attention Module: Integrates latent features from both drugs and cell lines for final response prediction.

Interpretation Methods

- Apply GNNExplainer and Integrated Gradients to identify active substructures of drugs and significant genes in cancer cells.

- Visualize attention weights to reveal mechanism of action between drugs and targets.

This protocol has demonstrated superior prediction accuracy compared to methods using SMILES strings or molecular fingerprints alone, while providing interpretable insights into drug-cell line interactions [14].

Protocol 2: Interpretable Deep Learning with Biological Subsystems

The DrugGene protocol represents an innovative approach that prioritizes model interpretability while maintaining high prediction accuracy [15]:

Data Processing Pipeline

- Data Sources: Utilize drug sensitivity data from CTRP and GDSC; genomic data from CCLE; biological process information from Gene Ontology (GO).

- Cell Line Features: Integrate gene mutation, gene expression, and copy number variation data, selecting the top 15% of genes most commonly mutated in human cancer.

- Drug Features: Encode compounds using Morgan fingerprint encoding with RDKit, representing each drug as a 2048-bit vector.

Model Architecture

- VNN Branch: Implement a hierarchical neural network structure based on 2,086 biological processes from GO ontology.

- ANN Branch: Employ a traditional artificial neural network to process drug fingerprint data.

- Integration Layer: Combine outputs from both branches through fully connected layers to generate final predictions.

Interpretability Features

- Map VNN neurons to specific biological pathways to monitor subsystem states.

- Identify molecular pathways highly correlated with predictions through transparent network structure.

- Enable mechanistic interpretation of how genotype-level changes affect drug response.

This protocol has demonstrated improved predictive performance for drug sensitivity compared to existing interpretable models like DrugCell on the same test set, while providing transparent insights into the biological mechanisms driving predictions [15].

Visualization of AI Workflows in Drug Discovery

Experimental Workflow for GNN-based Drug Response Prediction

GNN-based Drug Response Prediction Workflow

AI Model Selection Decision Pathway

AI Model Selection Decision Pathway

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The experimental protocols featured in this analysis rely on specialized computational tools and data resources that constitute the essential "research reagents" of AI-driven drug discovery:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for AI-Driven Anticancer Drug Discovery

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Function in Research | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drug Sensitivity Databases | GDSC, CTRP, CCLE | Provide curated drug response data for model training and validation | Publicly available via respective portals |

| Chemical Information Resources | PubChem, ChEMBL | Supply drug structures and bioactivity data | Publicly available online |

| Molecular Processing Tools | RDKit, OpenBabel | Convert chemical structures to machine-readable formats | Open-source software |

| Genomic Data Repositories | TCGA, GO, LINCS L1000 | Provide multi-omics data for cell lines and tumors | Publicly accessible databases |

| Deep Learning Frameworks | PyTorch, TensorFlow, DeepChem | Enable implementation of neural network architectures | Open-source platforms |

| Specialized AI Tools | AlphaFold, POLYGON, DRUML | Provide pre-trained models for specific tasks | Varied access (some public, some proprietary) |

The comparative analysis presented herein demonstrates that each AI methodology offers distinct advantages for specific aspects of anticancer drug discovery. Traditional machine learning provides interpretable models with moderate data requirements, making it suitable for preliminary investigations and resource-constrained environments. Deep learning excels in processing complex, high-dimensional data and often achieves superior predictive accuracy, albeit with greater computational demands and reduced interpretability. Graph neural networks strike an effective balance for molecular analysis tasks, naturally representing chemical structures while maintaining reasonable interpretability through attention mechanisms.

The emerging generation of interpretable deep learning models, such as visible neural networks (VNNs) that incorporate biological pathway information, represents a promising direction for the field. These approaches maintain competitive predictive performance while providing crucial mechanistic insights into drug action—a essential requirement for translational research and regulatory approval [15]. As AI methodologies continue to evolve, their integration with experimental validation will be crucial for establishing robust, clinically applicable models that can genuinely accelerate the development of novel anticancer therapies.

Future advancements will likely focus on multi-modal AI systems that seamlessly integrate diverse data types—from molecular structures and omics profiles to clinical records and medical imaging. Such integrated approaches promise to capture the full complexity of cancer biology and deliver increasingly personalized therapeutic strategies, ultimately improving success rates in oncology drug development and patient outcomes.

The application of artificial intelligence (AI) in anticancer drug discovery represents a fundamental transformation in how researchers approach the complex challenge of cancer therapeutics. Traditional drug discovery processes are notoriously time-consuming and costly, often requiring over a decade and billions of dollars to bring a single drug to market, with success rates for oncology drugs sitting well below 10% [8] [3]. AI technologies are addressing these inefficiencies by introducing unprecedented computational power and predictive capabilities across the entire drug development pipeline.

This comparative analysis examines three foundational AI concepts—generative models, natural language processing (NLP), and reinforcement learning—that are collectively reshaping anticancer drug discovery. These technologies enable researchers to navigate the immense complexity of cancer biology, which is characterized by tumor heterogeneity, resistance mechanisms, and intricate microenvironmental factors that complicate therapeutic targeting [8]. By integrating and analyzing massive, multimodal datasets—from genomic profiles and protein structures to clinical literature and trial outcomes—these AI approaches accelerate the identification of druggable targets, optimize lead compounds, and personalize therapeutic strategies [8] [10].

The following sections provide a detailed comparative examination of each AI concept's underlying principles, specific applications in oncology, experimental protocols, and performance metrics based on current research and implementation case studies.

Comparative Framework: Core AI Concepts in Oncology Drug Discovery

Table 1: Fundamental AI Concepts and Their Roles in Anticancer Drug Discovery

| AI Concept | Core Function | Primary Oncology Applications | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Generative Models | Create novel molecular structures with desired properties | de novo drug design, molecular optimization, multi-target drug discovery | Explores vast chemical spaces beyond human intuition; generates structurally diverse candidates [18] |

| Natural Language Processing (NLP) | Extract and synthesize knowledge from unstructured text | Biomedical literature mining, clinical note analysis, patent information extraction | Processes massive text corpora efficiently; identifies hidden connections across research domains [8] |

| Reinforcement Learning | Optimize decision-making through iterative reward feedback | Molecular property optimization, multi-parameter balancing, adaptive trial design | Navigates complex optimization landscapes; balances multiple competing objectives simultaneously [19] [20] |

Generative AI Models for de novo Molecular Design

Technical Foundations and Architectures

Generative AI models represent a transformative approach to molecular design by learning the underlying probability distribution of chemical structures from existing datasets and generating novel compounds with optimized properties. These models have demonstrated remarkable potential in anticancer drug discovery by enabling researchers to explore chemical spaces far beyond human intuition and existing compound libraries [18]. The most impactful architectures include Variational Autoencoders (VAEs), Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), and transformer-based models, each with distinct strengths for specific aspects of molecular generation.

VAEs operate through an encoder-decoder structure that compresses input molecules into a continuous latent space and reconstructs them, enabling smooth interpolation and generation of novel structures by sampling from this learned space [18] [20]. This architecture is particularly valuable for goal-directed generation, as the latent space can be navigated to optimize specific chemical properties. GANs employ a competitive framework with two neural networks: a generator that creates candidate molecules and a discriminator that distinguishes between real and generated compounds [19] [18]. This adversarial training process progressively improves the quality and validity of generated molecules. Transformer models, originally developed for natural language processing, have been adapted for molecular generation by treating chemical representations (such as SMILES strings) as sequences, allowing them to capture complex long-range dependencies in molecular structures [18].

Experimental Protocols and Validation

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Generative Model Architectures in Anticancer Applications

| Model Architecture | Validity Rate | Uniqueness | Novelty | Optimization Efficiency | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) | 70-92% | 60-85% | 40-80% | Moderate | Limited output diversity; challenging multi-property optimization [18] |

| Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) | 80-95% | 70-90% | 50-85% | High | Training instability; mode collapse issues [18] |

| Transformer Models | 85-98% | 75-95% | 60-90% | High | Computationally intensive; requires large datasets [18] |

| Diffusion Models | 90-99% | 80-97% | 70-95% | Moderate-High | Slow generation speed; complex training process [18] |

A typical experimental protocol for validating generative models in anticancer drug discovery follows these key stages:

Data Curation and Preprocessing: Collect and standardize large-scale chemical datasets (e.g., ChEMBL, ZINC, PubChem) comprising known bioactive molecules, cancer-relevant compounds, and approved oncology drugs. Represent molecules in appropriate formats (SMILES, SELFIES, molecular graphs, or 3D representations) and calculate molecular descriptors for property prediction [18] [20].

Model Training and Conditioning: Train generative models on the curated datasets, often incorporating conditioning vectors that encode desired anticancer properties (e.g., target affinity, selectivity, permeability). For multi-target approaches, models are conditioned on activity profiles across multiple cancer-relevant proteins [20].

Molecular Generation and Virtual Screening: Generate novel molecular structures through sampling from the trained model. Initially screen generated compounds using computational filters for drug-likeness (Lipinski's Rule of Five), synthetic accessibility, and potential toxicity [18].

In Silico Validation: Perform molecular docking against cancer targets (e.g., kinase domains, immune checkpoint proteins) to predict binding affinities and modes. Utilize quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models to predict potency against specific cancer cell lines [19] [10].

Experimental Validation: Synthesize top-ranking compounds and evaluate in vitro against relevant cancer cell models, assessing cytotoxicity, selectivity, and mechanism of action. Advance promising candidates to in vivo testing in patient-derived xenografts or genetically engineered mouse models [21].

Research Reagent Solutions for Generative AI Workflows

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for AI-Driven Molecular Generation

| Reagent/Platform | Function | Application in AI Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Chemistry42 Platform (Insilico Medicine) | Generative chemistry with multi-modal reinforcement learning | Structure-based generative chemistry for cancer drug discovery; enabled discovery of CDK8 inhibitor [22] |

| AlphaFold2 | Protein structure prediction | Provides accurate 3D protein structures for structure-based generative design and molecular docking [10] |

| Centaur Chemist (Exscientia) | AI-driven small molecule design platform | Accelerated discovery of anticancer compound entering Phase 1 trials in 8 months vs. traditional 4-5 years [22] |

| MO:BOT Platform (mo:re) | Automated 3D cell culture system | Generates high-quality, reproducible organoid data for training and validating generative models on human-relevant systems [9] |

| Cenevo/Labguru | R&D data management platform | Unifies experimental data from disparate sources, creating structured datasets for training generative models [9] |

Natural Language Processing for Knowledge Extraction

Technical Foundations and Methodologies

Natural Language Processing (NLP) applies computational techniques to analyze, understand, and generate human language, enabling transformative knowledge extraction capabilities in anticancer drug discovery. NLP technologies are particularly valuable for synthesizing information from the massive and rapidly expanding biomedical literature, which contains critical insights about cancer biology, drug mechanisms, and clinical outcomes that would otherwise remain fragmented and underutilized [8]. Modern NLP systems leverage large language models (LLMs) trained on extensive scientific corpora to identify relationships between biological entities, extract drug-target interactions, and generate hypotheses for experimental validation.

Key NLP methodologies in drug discovery include named entity recognition (identifying specific biological entities such as genes, proteins, and compounds), relation extraction (detecting functional relationships between entities), text classification (categorizing documents by relevance or theme), and knowledge graph construction (creating structured networks of biological knowledge) [8]. These approaches enable researchers to connect disparate findings across thousands of publications, revealing novel therapeutic targets and repurposing opportunities. Transformer-based architectures like BERT and its biomedical variants (BioBERT, SciBERT) have significantly advanced these capabilities by providing context-aware representations of scientific text [8].

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

A standardized protocol for implementing NLP in anticancer drug discovery involves:

Corpus Collection and Preprocessing: Assemble relevant text corpora from biomedical databases (PubMed, PubMed Central, clinical trial registries), patent repositories, and internal research documents. Apply text cleaning, tokenization, and sentence segmentation to prepare data for analysis [8].

Domain-Specific Model Training or Fine-Tuning: Utilize pre-trained language models and fine-tune them on domain-specific oncology literature to improve performance on cancer-related terminology and concepts. For specialized applications, train custom models on curated datasets of cancer research publications [8].

Knowledge Extraction and Relationship Mining: Implement named entity recognition to identify cancer-relevant entities (genes, proteins, pathways, compounds). Apply relation extraction algorithms to establish connections between these entities, focusing on disease associations, drug mechanisms, and biomarker relationships [8] [10].

Hypothesis Generation and Validation: Generate novel therapeutic hypotheses based on extracted relationships, such as drug repurposing opportunities or previously unrecognized drug-target-disease associations. Validate these hypotheses through experimental testing in relevant cancer models [8].

Table 4: NLP Performance Metrics in Oncology Drug Discovery Applications

| NLP Task | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | Key Applications in Oncology |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Named Entity Recognition | 85-92% | 80-88% | 83-90% | Identifying cancer genes, biomarkers, therapeutic targets from literature [8] |

| Relation Extraction | 78-90% | 75-85% | 77-87% | Discovering drug-target interactions, pathway relationships [8] |

| Text Classification | 90-95% | 88-93% | 89-94% | Categorizing clinical trial outcomes, adverse event reports [8] |

| Knowledge Graph Construction | N/A | N/A | N/A | Integrating multimodal data for systems biology insights [10] |

Research Reagent Solutions for NLP Implementation

Table 5: Essential NLP Tools and Platforms for Oncology Research

| Tool/Platform | Function | Application in Oncology Drug Discovery |

|---|---|---|

| IBM Watson for Oncology | NLP-powered clinical decision support | Analyzes structured and unstructured patient data to identify potential treatment options [8] |

| BioBERT | Domain-specific language model | Pre-trained on biomedical literature; excels at extracting cancer-specific relationships [8] |

| Sonrai Discovery Platform | Multi-modal data integration with AI | Integrates imaging, multi-omic, and clinical data using NLP techniques for biomarker discovery [9] |

| Cenevo/Labguru AI Assistant | Intelligent search and data organization | Enhances literature review and experimental data retrieval for cancer research projects [9] |

Reinforcement Learning for Optimization and Adaptive Design

Technical Foundations and Algorithmic Approaches

Reinforcement Learning (RL) represents a powerful paradigm for sequential decision-making where an agent learns optimal behaviors through interaction with an environment and feedback received via reward signals. In anticancer drug discovery, RL algorithms excel at navigating complex optimization landscapes with multiple competing objectives, such as balancing drug potency, selectivity, and safety profiles [19] [20]. The fundamental RL framework consists of an agent that takes actions (e.g., modifying molecular structures), an environment that responds to these actions (e.g., predictive models of bioactivity), and a reward function that quantifies the desirability of outcomes (e.g., multi-parameter optimization scores).

Key RL algorithms applied in drug discovery include Deep Q-Networks (DQN), which combine Q-learning with deep neural networks to handle high-dimensional state spaces; Policy Gradient methods, which directly optimize the policy function mapping states to actions; and Actor-Critic approaches, which hybridize value-based and policy-based methods for improved stability [19] [20]. In molecular optimization, RL agents typically learn to make sequential modifications to molecular structures, receiving rewards based on improved pharmacological properties, ultimately converging on compounds with optimized multi-property profiles. For multi-target drug design, RL is particularly valuable as it can balance trade-offs between affinity at different targets while maintaining favorable drug-like properties [20].

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

The implementation of RL in anticancer drug discovery follows structured experimental protocols:

Environment Design: Define the state space (molecular representations), action space (allowable molecular modifications), and reward function (quantifying desired molecular properties). The reward function typically incorporates multiple objectives such as target affinity, selectivity, solubility, and low toxicity [20].

Agent Training: Train the RL agent through episodes of interaction with the environment. In each episode, the agent sequentially modifies molecular structures and receives rewards based on property improvements. Training continues until the agent converges on policies that reliably generate high-quality compounds [20].

Multi-Objective Optimization: Implement reward shaping techniques to balance competing objectives. For multi-target anticancer agents, this involves carefully weighting contributions from different target affinities to achieve the desired polypharmacological profile [20].

Validation and Iteration: Evaluate top-ranking compounds generated by the RL agent through in silico validation (molecular docking, ADMET prediction) and experimental testing. Use results to refine the reward function and retrain the agent in an iterative feedback loop [20].

Table 6: Reinforcement Learning Performance in Molecular Optimization

| RL Algorithm | Sample Efficiency | Optimization Performance | Multi-Objective Handling | Stability | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deep Q-Networks (DQN) | Moderate | High | Moderate | Moderate | Single-target optimization; property prediction [20] |

| Policy Gradient Methods | Low-Moderate | High | Good | Low-Moderate | De novo molecular design; scaffold hopping [20] |

| Actor-Critic Methods | Moderate-High | High | Good | High | Multi-target drug design; balanced property optimization [20] |

| Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) | High | High | Excellent | High | Complex multi-parameter optimization with constraints [20] |

Self-Improving Drug Discovery Frameworks

A particularly advanced application of RL in anticancer drug discovery is the development of self-improving frameworks that integrate RL with active learning in a closed-loop Design-Make-Test-Analyze (DMTA) cycle [20]. In these systems, RL handles the "Design" component by generating novel compounds optimized for multiple targets and properties. The "Make" and "Test" phases involve automated synthesis and screening, while "Analyze" utilizes active learning to identify the most informative compounds for subsequent testing. The results feed back into the RL system to update the reward function and policy, creating a continuous self-improvement cycle [20].

These self-improving systems demonstrate remarkable efficiency gains. Case studies show that RL-driven platforms can reduce the number of synthesis and testing cycles needed to identify high-quality lead compounds by 3-5x compared to traditional approaches [20]. Furthermore, multi-target agents discovered through these frameworks show improved therapeutic efficacy in complex cancer models where single-target agents often fail due to compensatory pathways and resistance mechanisms [20].

Research Reagent Solutions for RL Implementation

Table 7: Essential Platforms and Tools for Reinforcement Learning in Drug Discovery

| Tool/Platform | Function | Application in Oncology |

|---|---|---|

| MolDQN | Deep Q-network for molecular optimization | Modifies molecules iteratively using multi-property reward functions [18] |

| Graph Convolutional Policy Network (GCPN) | RL with graph neural networks | Generates novel molecular graphs with targeted properties for cancer-relevant targets [18] |

| DeepGraphMolGen | Multi-objective RL for molecular generation | Designed molecules with strong binding affinity to dopamine transporters while minimizing off-target effects [18] |

| Chemistry42 (Insilico Medicine) | Multi-modal generative RL platform | Used generative reinforcement learning to discover CDK8 inhibitor for cancer treatment [22] |

Integrated Applications and Comparative Performance

Case Studies in Anticancer Drug Discovery

The true potential of AI in anticancer drug discovery emerges when generative models, NLP, and reinforcement learning are integrated into cohesive workflows. Several case studies demonstrate this synergistic potential:

Exscientia's AI-designed molecule DSP-1181, developed for psychiatric indications, entered human trials in just 12 months compared to the typical 4-5 years, demonstrating the acceleration possible with AI-driven approaches [8]. Similar platforms are now being applied to oncology projects, with Exscientia and Evotec announcing a Phase 1 clinical trial for a novel anticancer compound developed using AI in just 8 months [22].

Insilico Medicine utilized a structure-based generative chemistry approach combining generative models with reinforcement learning to discover a potent, selective small molecule inhibitor of CDK8 for cancer treatment [22]. The company's Chemistry42 platform employs multi-modal generative reinforcement learning to optimize multiple chemical properties simultaneously, significantly accelerating the hit-to-lead optimization process.

In multi-target drug design, deep generative models empowered by reinforcement learning have demonstrated the capability to generate novel compounds with balanced activity across multiple cancer-relevant targets [20]. This approach is particularly valuable in oncology, where network redundancy and pathway compensation often limit the efficacy of single-target agents. RL-driven multi-target optimization can identify compounds that simultaneously modulate several key pathways in cancer cells, potentially overcoming resistance mechanisms and improving therapeutic outcomes [20].

Comparative Performance Analysis

Table 8: Integrated AI Approaches in Anticancer Drug Discovery

| AI Technology | Time Savings | Success Rate Improvement | Key Advantages | Implementation Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generative Models | 3-5x acceleration in early discovery | 2-4x increase in lead compound identification | Explores vast chemical spaces; generates novel scaffolds | Requires large, high-quality datasets; limited interpretability [18] |

| Natural Language Processing | 5-10x faster literature review | Identifies 30-50% more relevant connections | Uncovers hidden relationships; integrates disparate knowledge sources | Domain-specific tuning required; vocabulary limitations [8] |

| Reinforcement Learning | 2-3x faster optimization cycles | 20-40% improvement in multi-parameter optimization | Excellent for balancing competing objectives; adaptive learning | Complex reward engineering; computationally intensive [20] |

| Integrated AI Platforms | 5-15x acceleration overall | 3-5x higher clinical candidate success | Synergistic benefits; end-to-end optimization | Significant infrastructure investment; interdisciplinary expertise needed [22] |

The comparative analysis of generative models, natural language processing, and reinforcement learning in anticancer drug discovery reveals a rapidly evolving landscape where AI technologies are transitioning from supplemental tools to core components of the drug development pipeline. Each approach brings distinctive capabilities: generative models for exploring chemical space, NLP for synthesizing knowledge, and reinforcement learning for complex optimization. However, the most significant advances emerge from integrated implementations that leverage the complementary strengths of these technologies.

Future directions in AI for anticancer drug discovery include the development of more sophisticated multi-modal models that seamlessly integrate structural, genomic, and clinical data; increased emphasis on explainable AI to build trust and provide mechanistic insights; and the expansion of self-improving closed-loop systems that continuously refine their performance based on experimental feedback [20] [9]. As these technologies mature, they promise to significantly reduce the time and cost of bringing new cancer therapies to market while improving success rates and enabling more personalized treatment approaches.

For research organizations implementing these technologies, success depends on addressing key challenges including data quality and standardization, computational infrastructure requirements, and the need for interdisciplinary teams combining AI expertise with deep domain knowledge in cancer biology and medicinal chemistry [9]. Organizations that effectively navigate these challenges and strategically integrate AI technologies throughout their drug discovery pipelines stand to gain significant competitive advantages in the increasingly complex landscape of oncology therapeutics development.

The traditional drug discovery pipeline, particularly in oncology, is characterized by immense costs, extended timelines, and high failure rates. It typically takes 10–15 years and costs approximately $2.6 billion to bring a new drug to market, with a success rate of less than 10% for oncology therapies [3] [23]. This inefficiency presents a critical bottleneck in delivering new cancer treatments to patients. Artificial Intelligence (AI) has emerged as a transformative force, promising to address these challenges by radically accelerating discovery timelines and improving clinical success rates. This guide provides a comparative analysis of AI's performance against traditional methods, focusing on its validated impact in anticancer drug discovery and development for a professional audience of researchers and drug development scientists.

Quantitative Performance: AI vs. Traditional Methods

The value proposition of AI is quantitatively demonstrated through key performance indicators comparing AI-driven workflows to traditional drug discovery processes.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of AI vs. Traditional Drug Discovery

| Performance Metric | Traditional Drug Discovery | AI-Driven Drug Discovery | Data Source & Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discovery to Preclinical Timeline | ~5 years | 1.5 - 2 years | Insilico Medicine (IPF drug: 18 months) [7] |

| Phase I Clinical Trial Success Rate | 40-65% (historical average) | 80-90% (AI-discovered molecules) | Analysis of AI-native Biotech pipelines [24] [25] [26] |

| Phase II Clinical Trial Success Rate | ~40% (historical average) | ~40% (based on limited data) | Analysis of AI-native Biotech pipelines [24] [26] |

| Lead Optimization Efficiency | Industry standard cycles | ~70% faster cycles, 10x fewer compounds synthesized | Exscientia's reported platform data [7] |

| Overall Attrition Rate | >90% failure from early clinical to market | Early data shows significantly lower failure in Phase I | [3] [23] |

Analysis of Leading AI Platforms and Methodologies

The accelerated performance of AI-driven discovery is enabled by distinct technological approaches implemented by leading platforms. The following section compares the core methodologies, experimental protocols, and clinical progress of five major AI-native companies.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Leading AI-Driven Drug Discovery Platforms

| AI Platform (Company) | Core AI Methodology | Key Technical Differentiator | Representative Clinical Asset & Status | Reported Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exscientia | Generative AI; "Centaur Chemist" | End-to-end platform integrating patient-derived biology (ex vivo screening on patient tumor samples) | CDK7 inhibitor (GTAEXS-617) - Phase I/II in solid tumors | First AI-designed drug (DSP-1181) entered trials; design cycles ~70% faster [7] |

| Insilico Medicine | Generative AI; Target-to-Design Pipeline | Generative reinforcement learning for novel molecular structure generation | ISM001-055 (TNK inhibitor for IPF) - Phase IIa with positive results | Target to Phase I in 18 months for IPF drug; similar approaches in oncology [7] |

| Recursion | Phenomics-First Systems | High-content cellular imaging & phenotypic screening integrated with AI analysis | Pipeline from merged platform post-Exscientia acquisition | Generates massive, proprietary biological datasets for target discovery [7] |

| BenevolentAI | Knowledge-Graph Repurposing | AI mines vast repositories of scientific literature and trial data for novel target insights | Baricitinib identified for COVID-19; novel glioblastoma targets | Uncovers hidden target-disease relationships from unstructured data [8] [27] |

| Schrödinger | Physics-Plus-ML Design | Combines first-principles physics-based simulations with machine learning | Zasocitinib (TYK2 inhibitor) - Phase III | Enables high-accuracy prediction of binding affinity and molecular properties [7] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

The performance gains reported by these platforms are underpinned by rigorous, AI-enhanced experimental workflows. Below are detailed methodologies for two critical processes: virtual screening and AI-driven clinical trial design.

Protocol 1: AI-Driven Virtual Screening for Hit Identification

This protocol is exemplified by benchmarks like the DO Challenge, which tasks AI systems with identifying top drug candidates from a library of one million molecules [28].

- Data Curation & Featurization: A library of 1 million unique molecular conformations is assembled. Each molecule is represented computationally using features that capture 3D structural information, ensuring descriptors are position non-invariant (sensitive to translation and rotation) to preserve critical spatial relationships [28].

- Strategic Sampling & Active Learning: Given a constrained budget (e.g., access to true "DO Score" labels for only 10% of the library), the AI agent implements an active learning strategy. It iteratively selects the most informative molecules for labeling to maximize the efficiency of resource use [28].

- Predictive Model Training: The agent develops and trains specialized neural networks, such as Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) or 3D Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), designed to learn the complex relationships between molecular structures and the target property (e.g., binding affinity, DO Score) [28].

- Candidate Selection & Iterative Refinement: The trained model predicts scores for all molecules in the library. The top candidates are selected for submission. High-performing strategies leverage multiple submission attempts, using outcomes from prior rounds to refine model predictions and subsequent selections [28].

Protocol 2: AI-Optimized Clinical Trial Design

AI's impact extends from discovery into clinical development, optimizing trials for speed and success [23] [25].

- Patient Recruitment & Cohort Optimization: Natural Language Processing (NLP) models, such as the NIH's TrialGPT, mine electronic health records (EHRs) and clinical literature to identify eligible patients and match them to relevant trials more efficiently. AI can also optimize inclusion/exclusion criteria to double the number of eligible patients without compromising scientific validity [25].

- Synthetic Control Arm Generation: Instead of enrolling all patients in a traditional control arm, AI generates a synthetic control arm using real-world data from various sources. This data is statistically adjusted to match the demographics and disease characteristics of the treatment arm, reducing recruitment needs and ethical concerns [23] [25].

- Digital Twin Simulation: For a more advanced approach, a digital twin of individual patients can be created. These are virtual representations that model disease trajectory and potential treatment response, allowing for in-silico testing of thousands of drug candidates or combinations before actual clinical enrollment [25].

- Adaptive Trial Management: AI algorithms analyze interim trial data in real-time. Using reinforcement learning or adaptive designs, the system can adjust parameters such as dosage, sample size, or patient stratification to identify effective treatments faster and raise potential safety issues earlier [25].

AI vs Traditional Drug Development Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Solutions

The effective implementation of AI in drug discovery relies on a suite of computational and data resources that function as essential "research reagents" for modern scientists.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for AI-Driven Drug Discovery

| Research Reagent / Solution | Function in AI-Driven Discovery | Example Platforms / Tools |

|---|---|---|

| Multi-omics Datasets | Provides integrated genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data for AI models to identify novel therapeutic targets and biomarkers. | The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) [8] |

| Predictive Protein Structure Models | Provides highly accurate 3D protein structures for druggability assessment and structure-based drug design when experimental structures are unavailable. | AlphaFold [23] [27] |

| Generative Chemistry AI | Acts as a virtual reagent library, generating novel, optimized molecular structures with desired pharmacological properties from scratch (de novo design). | Insilico Medicine GENTRL [7]; Exscientia Generative Models [7] |

| Knowledge Graphs | Semantically links fragmented biological, chemical, and clinical data from public and proprietary sources to uncover hidden target-disease relationships and support drug repurposing. | BenevolentAI Knowledge Graph [8] [7] |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | Computational models that learn from graph-structured data, essential for predicting molecular properties and interactions by modeling atoms and bonds as nodes and edges. | Deep Thought Agentic System [28] |

| Synthetic Control Arms | A regulatory-qualified solution that uses real-world data to create virtual control arms for clinical trials, reducing enrollment needs and accelerating timelines. | Unlearn.AI Digital Twins Platform [25] |

The comparative data is clear: the AI value proposition in anticancer drug discovery is delivering on its promise of accelerated timelines and enhanced success rates. The markedly higher Phase I success rate of 80-90% for AI-discovered molecules, compared to the historical average, is a powerful early indicator that AI algorithms are highly capable of generating molecules with superior drug-like properties [24] [25] [26]. This performance, combined with the compression of discovery timelines from years to months as demonstrated by companies like Insilico Medicine and Exscientia, signals a definitive paradigm shift [7]. For researchers and drug development professionals, the integration of AI platforms and the "reagents" of the digital age—from multi-omics datasets to generative models—is no longer a speculative future but a present-day necessity for driving pharmaceutical innovation and delivering effective cancer therapies to patients faster.

AI in Action: Comparative Methodologies of Leading Drug Discovery Platforms

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into oncology drug discovery is fundamentally reshaping how researchers identify and validate novel therapeutic targets. Target identification represents the critical first step in the drug development pipeline, where biological entities such as proteins, genes, or pathways are identified as potential sites for therapeutic intervention [21]. Traditional drug discovery methods, which often rely on time-intensive experimental screening and linear hypothesis testing, typically span over a decade with costs exceeding $2 billion per approved drug, accompanied by failure rates approaching 90% [23]. These inefficiencies are particularly pronounced in oncology, where disease complexity, tumor heterogeneity, and the challenge of target druggability create significant barriers to successful therapeutic development [23].

AI-driven approaches are overcoming these limitations by leveraging machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) algorithms to analyze massive, multi-dimensional datasets that capture the complex biological underpinnings of cancer. By integrating diverse multi-omics data (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) within the contextual framework of network biology, AI models can uncover hidden patterns and relationships that would remain undetectable through conventional analytical methods [29] [23]. This paradigm shift enables researchers to move beyond reductionist, single-target approaches toward a more holistic understanding of cancer as a complex network disease, ultimately accelerating the identification of novel oncogenic vulnerabilities and more effective therapeutic strategies [29].

Comparative Analysis of AI Methodologies

The application of AI in target identification encompasses a diverse ecosystem of computational approaches, each with distinct strengths, limitations, and optimal use cases. The table below provides a systematic comparison of the primary AI methodologies employed in anticancer drug discovery.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of AI Methodologies for Target Identification in Anticancer Drug Discovery

| Method Category | Key Algorithms | Primary Applications in Target ID | Strengths | Limitations | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Network-Based Integration Methods | Network propagation/diffusion, Similarity-based approaches, Graph neural networks (GNNs), Network inference models [29] | Drug target identification, Drug repurposing, Prioritizing targets from multi-omics data [29] | Captures complex biomolecular interactions, Integrates heterogeneous data types, Reflects biological system organization [29] | Computational scalability challenges, Complex biological interpretation, Requires high-quality network data [29] | GNNs show 15-30% improvement over traditional ML in predicting drug-target interactions [29] |

| Supervised Machine Learning | Support Vector Machines (SVM), Random Forests (RF), Logistic Regression (LR) [30] [31] | Classification of cancer types, Prediction of treatment outcomes, Target prioritization based on historical data [30] | High interpretability, Effective with structured data, Robust to noise with ensemble methods [30] [31] | Limited with unstructured data, Requires extensive feature engineering, Prone to bias with imbalanced datasets [31] | RF and SVM achieve 80-90% accuracy in cancer type classification from genomic data [30] |

| Deep Learning | Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), Vision Transformers, Deep neural networks (DNNs) [30] [31] | Tumor detection from imaging, Feature extraction from histopathology slides, Predicting protein structures [30] [31] | Automatic feature extraction, Superior with image/data-rich sources, Handles complex nonlinear relationships [31] | "Black box" interpretability challenges, Requires large training datasets, Computationally intensive [30] [31] | CNN-based models achieve >85% accuracy in predicting drug resistance from histopathology images [31] |

| Generative AI & Foundation Models | Generative adversarial networks (GANs), Transformer models, AlphaFold [32] [21] [23] | De novo drug design, Protein structure prediction, Identifying novel drug-target interactions [32] [23] | Creates novel molecular structures, Predicts 3D protein structures with high accuracy, Accelerates discovery of first-in-class drugs [32] [23] | High computational resource requirements, Limited transparency in generated outputs, Validation challenges for novel structures [21] [23] | AlphaFold predicts protein structures with accuracy comparable to experimental methods [23] |

Key Insights from Comparative Analysis

The comparative analysis reveals that method selection should be guided by specific research objectives and data characteristics. Network-based approaches particularly excel in leveraging the inherent connectivity of biological systems, with graph neural networks demonstrating superior performance for target identification tasks that benefit from relationship mapping between biological entities [29]. These methods enable researchers to contextualize multi-omics findings within established biological pathways, revealing previously unrecognized network vulnerabilities in cancer cells [29].

For well-structured classification tasks with clearly defined features, traditional supervised learning algorithms like Random Forests and Support Vector Machines remain highly competitive, offering the advantage of model interpretability alongside robust performance [30] [31]. However, with the increasing availability of high-dimensional data from sources such as whole-slide imaging and transcriptomic profiling, deep learning approaches are demonstrating remarkable capabilities in extracting biologically relevant features directly from complex data structures without extensive manual feature engineering [31].

The emergence of generative AI and foundation models represents a transformative development, particularly through tools like AlphaFold that accurately predict protein structures, thereby enabling target assessment for previously "undruggable" proteins that lack experimentally determined structures [23]. This capability significantly expands the universe of potential therapeutic targets in oncology.

Experimental Protocols for AI-Driven Target Identification

Network-Based Multi-Omics Integration Protocol

Objective: To identify novel therapeutic targets by integrating multi-omics data within biological network frameworks.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Network-Based Multi-Omics Integration

| Research Reagent | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) Networks [29] | Framework for integrating multi-omics data and identifying key network nodes | Provides physical interaction context; databases include STRING, BioGRID |

| Gene Regulatory Networks (GRNs) [29] | Mapping regulatory relationships between genes and potential targets | Reveals transcriptional regulatory cascades important in cancer |

| Drug-Target Interaction (DTI) Networks [29] | Predicting novel drug-target relationships and repurposing opportunities | Integrates chemical and biological space for polypharmacology predictions |

| Multi-omics Datasets (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) [29] [23] | Providing molecular profiling data for integration | Reveals complementary biological insights across molecular layers |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Screening Data [23] | Functional validation of target essentiality in specific cancer contexts | Provides experimental evidence for gene essentiality |

Workflow:

- Data Collection and Curation: Acquire multi-omics data including genomic mutations, transcriptomic profiles, proteomic measurements, and metabolomic readings from relevant cancer models or patient samples [29] [23]. Simultaneously, gather established biological network data from protein-protein interaction databases, gene regulatory networks, and metabolic pathways [29].

- Data Preprocessing and Normalization: Perform quality control, missing value imputation, batch effect correction, and normalization across all omics datasets to ensure technical consistency [31]. Transform heterogeneous data types into compatible formats for network integration.

- Network Integration and Analysis: Implement graph-based algorithms such as network propagation, graph neural networks, or similarity-based approaches to map multi-omics data onto biological networks [29]. Identify significantly altered network modules, central nodes (hubs), and bottleneck proteins that demonstrate both topological importance and molecular dysregulation.

- Target Prioritization: Apply machine learning classifiers (Random Forests, SVM) or deep learning architectures to rank candidate targets based on integrated scores incorporating network centrality, functional essentiality, dysregulation significance, and druggability predictions [29] [23].

- Experimental Validation: Validate top-ranked targets through CRISPR-Cas9 knockout screens, RNA interference, or small molecule inhibition in relevant cancer cell lines or patient-derived organoids [23]. Assess impact on cell viability, proliferation, and relevant pathway modulation.

AI-Driven Drug Target Discovery Case Study

Exemplar Protocol: AI-guided discovery of Z29077885 as a novel anticancer agent targeting STK33 [21].

Background: This study exemplifies a complete AI-driven workflow from target identification to experimental validation, resulting in the discovery of a novel small molecule inhibitor with demonstrated efficacy in cancer models.

Methodology:

- Target Identification: Implemented an AI-driven screening strategy analyzing a large-scale database integrating public repositories and manually curated information describing therapeutic patterns between compounds and diseases [21]. The system prioritized STK33 (serine/threonine kinase 33) as a potential vulnerability in cancer cells.

- Compound Screening: Screened compound libraries using ML models trained on chemical and biological features to identify Z29077885 as a putative STK33 inhibitor [21].

- Mechanistic Investigation: Conducted in vitro analyses demonstrating that Z29077885 induces apoptosis through deactivation of the STAT3 signaling pathway and causes cell cycle arrest at the S phase [21].

- In Vivo Validation: Performed animal studies confirming that treatment with Z29077885 significantly decreased tumor size and induced necrotic areas in tumor models [21].

Significance: This case study demonstrates a fully integrated AI-driven approach that successfully bridged computational prediction with experimental validation, resulting in the identification of a novel anticancer agent with a defined mechanism of action [21].

Implementation Considerations and Best Practices

Data Quality and Preprocessing

The performance of AI models in target identification is fundamentally constrained by data quality. High-quality, curated datasets with comprehensive metadata are essential for training robust models [9] [23]. Best practices include:

- Implementing rigorous data normalization across technical replicates and batches to minimize non-biological variance [31].

- Addressing missing data through appropriate imputation methods or strategic exclusion to prevent algorithmic bias [31].

- Applying feature selection techniques to reduce dimensionality while preserving biologically relevant signals [31].

- Ensuring balanced representation across biological conditions to prevent model skewing toward overrepresented classes [23].

Model Interpretability and Transparency

The "black box" nature of complex AI algorithms presents significant challenges for biological interpretation and clinical adoption. Strategies to enhance interpretability include:

- Implementing model explanation frameworks such as SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) to quantify feature importance and identify key biological drivers of predictions [31].

- Incorporating attention mechanisms in deep learning models to highlight relevant input regions, particularly for imaging or genomic data [31].

- Utilizing network visualization tools to contextualize predictions within established biological pathways and interactions [29].

- Maintaining comprehensive model documentation including training data characteristics, hyperparameters, and performance benchmarks [33].

Validation Frameworks

Rigorous validation is essential to establish model reliability and translational potential:

- Employ cross-validation strategies (k-fold, leave-one-out) to assess model stability and prevent overfitting [31].

- Implement external validation using completely independent datasets to evaluate generalizability across different patient populations or experimental conditions [31].

- Include experimental validation through molecular biology techniques (e.g., CRISPR screening, Western blot, IHC) to confirm biological mechanisms [31].

- Establish clinical correlation by linking model predictions to relevant patient outcomes such as treatment response or survival [31].

The integration of AI-driven approaches with multi-omics data and network biology is fundamentally advancing target identification in anticancer drug discovery. The comparative analysis presented in this guide demonstrates that while each methodological approach offers distinct advantages, their complementary application within integrated workflows yields the most robust results. Network-based methods excel at contextualizing findings within biological systems, supervised learning provides interpretable classification, deep learning extracts complex patterns from high-dimensional data, and generative models enable exploration of novel chemical and biological space [30] [29] [23].

Future developments in this field will likely focus on several key areas: enhancing model interpretability through more sophisticated explanation architectures, improving data integration capabilities to incorporate emerging data types such as spatial transcriptomics and single-cell multi-omics, and developing temporal modeling approaches to capture the dynamic evolution of cancer networks under therapeutic pressure [29] [31]. Additionally, the establishment of standardized benchmarking frameworks will be crucial for objectively evaluating methodological performance across diverse cancer contexts and enabling systematic comparison of emerging approaches [29].