Advancing Drug Resistance Prediction: Machine Learning and Genomic Approaches for Improved Accuracy

This article synthesizes current advancements in predicting antimicrobial and antitubercular drug resistance mutations, targeting researchers and drug development professionals.

Advancing Drug Resistance Prediction: Machine Learning and Genomic Approaches for Improved Accuracy

Abstract

This article synthesizes current advancements in predicting antimicrobial and antitubercular drug resistance mutations, targeting researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational understanding of resistance mechanisms, examines cutting-edge machine learning and next-generation sequencing methodologies, addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization challenges in model development, and provides frameworks for rigorous clinical validation and comparative performance analysis. By integrating genomic data with sophisticated algorithms, this review highlights pathways toward more accurate, rapid, and clinically actionable resistance prediction tools to combat the global AMR crisis.

Understanding the Genomic Landscape of Drug Resistance

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

This technical support center is designed for researchers and scientists working to improve the prediction accuracy of drug resistance mutations. The guides below address common computational and experimental challenges in this field, with a focus on drug-resistant tuberculosis (DR-TB).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Our whole-genome sequencing analysis is producing a high rate of false-positive resistance markers. How can we improve specificity?

- A: High false-positive rates often occur when analysis tools mistakenly link unrelated mutations to resistance. To address this:

- Employ advanced machine learning models that do not rely solely on pre-defined resistance mechanisms. For example, the Group Association Model (GAM) uses a bacteria's entire genetic fingerprint to identify resistance patterns, which has been shown to drastically reduce false positives [1].

- Utilize ensemble-based molecular dynamics methods, like TIES_PM, for resistance prediction in specific proteins like RNA polymerase. This method calculates binding free energy changes to provide a more reliable link between mutation and function, with results aligned to WHO classifications [2].

Q2: What are the key limitations of current phenotypic drug susceptibility testing (DST) and how can computational methods complement them?

- A: Traditional methods have significant trade-offs between speed and accuracy.

- Culture-based DST (e.g., on Lowenstein-Jensen medium) is highly specific but slow, taking 4–6 weeks for results [2].

- Molecular tests like GeneXpert are faster (under 2 hours) but can lack the ability to detect rare or novel mutations and cannot distinguish between viable and non-viable bacteria [2].

- Computational supplements can bridge this gap. Molecular dynamics simulations (e.g., with TIES_PM) can predict resistance for mutations in large protein complexes within about 5 hours, offering a rapid, accurate, and low-cost supplement to wet-lab methods [2].

Q3: Our research requires analyzing the global burden of multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB). What are the most reliable current estimates and trends?

- A: The most current data shows a persistent and evolving global challenge. The following table summarizes key burden metrics from recent studies.

Table 1: Global Burden of MDR-/RR-TB and XDR-TB

| Metric | MDR-/RR-TB (2022) [3] | MDR-TB (2021) [4] | XDR-TB (2021) [4] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Incident Cases | 410,000 (UI: 370,000–450,000) | Age-Std. Incidence Rate: 5.42 per 100,000 | Age-Std. Incidence Rate: 0.29 per 100,000 |

| Mortality | 160,000 deaths (UI: 98,000–220,000) | Data not available | Data not available |

| Notable Trends | Relatively stable 2020-2022; downward revision of estimates since 2015. | Increasing trend (1990-2021), esp. in low & low-middle SDI regions. | Increasing trend (1990-2021) across all SDI regions. |

Q4: The burden of MDR-TB in children and adolescents is poorly understood. What is the known disease burden in this demographic?

- A: Research using the GBD 2019 database has quantified this burden, revealing a significant and growing problem, particularly in younger children and lower-resource regions [5].

- In 2019, there were an estimated 67,710.82 incident cases of MDR-TB in individuals under 20 years old worldwide [5].

- The mortality and DALY rates are highest in children under 5 years (0.62 and 55.19 per 100,000, respectively) compared to older age groups, highlighting their vulnerability [5].

- The global incidence rate in this population has increased from 1990 to 2019, with the largest shares of the burden found in Southern sub-Saharan Africa, Eastern Europe, and South Asia [5].

Troubleshooting Guide: Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Predicting Rifampicin Resistance with TIES_PM Molecular Dynamics

This protocol estimates the binding affinity of Rifampicin to mutated RNA polymerase (RNAP) through free energy calculations [2].

- Objective: To accurately predict if a mutation in the rpoB gene confers resistance to Rifampicin by quantifying its impact on drug binding.

- Workflow:

- System Preparation: Obtain 3D structures of wild-type and mutant RNAP bound to Rifampicin.

- Simulation Setup: Use software like GROMACS or AMBER to set up the molecular dynamics simulation with explicit solvent and ions.

- Relative Binding Free Energy (RBFE) Calculation: Employ the TIES_PM method to perform alchemical transformation simulations, gradually changing the wild-type amino acid to the mutant.

- Energy Analysis: Calculate the difference in binding free energy (ΔΔG) between the wild-type and mutant complexes.

- Interpretation: A positive ΔΔG value indicates a mutation that destabilizes drug binding, predicting resistance. The method requires ~5 hours per mutation on high-performance computing (HPC) systems.

- Troubleshooting Tip: The ensemble-based approach of TIES_PM is crucial for statistical robustness. Ensure sufficient sampling and replica simulations to achieve reliable results.

Protocol 2: Applying a Group Association Model (GAM) for Novel Mutation Discovery

This machine learning-based method identifies genetic mutations associated with drug resistance without prior knowledge of the mechanism [1].

- Objective: To discover previously unknown genetic markers of antibiotic resistance from whole-genome sequence data.

- Workflow:

- Data Curation: Assemble a large dataset of whole-genome sequences from bacterial strains (e.g., M. tuberculosis) with known phenotypic resistance profiles.

- Model Training: Train the GAM by comparing groups of resistant and susceptible strains to find genetic changes that reliably indicate resistance to specific drugs.

- Validation: Test the model's accuracy against a held-out validation set and compare its performance to existing databases (e.g., the WHO's resistance database).

- Application: Use the trained model to screen new, uncharacterized bacterial genomes for potential resistance markers.

- Troubleshooting Tip: This model's performance is dependent on the quality and size of the input dataset. Use data from diverse geographic regions to improve the model's generalizability and ability to detect rare mutations.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Drug Resistance Prediction Research

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Whole-Genome Sequence Data (e.g., from clinical M. tuberculosis isolates) | The fundamental raw data for identifying genetic mutations and training machine learning models like GAM [1]. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Provides the computational power necessary for running complex molecular dynamics simulations and large-scale bioinformatic analyses [2]. |

| Molecular Dynamics Software (e.g., GROMACS, AMBER) | Software suites used to simulate the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time, enabling free energy calculations [2]. |

| Phenotypic Drug Susceptibility Testing (DST) Data | Serves as the gold-standard ground truth for validating predictions made by computational models [2]. |

| 3D Protein Structures (e.g., from Protein Data Bank) | Essential starting structures for molecular dynamics simulations to study drug-target interactions [2]. |

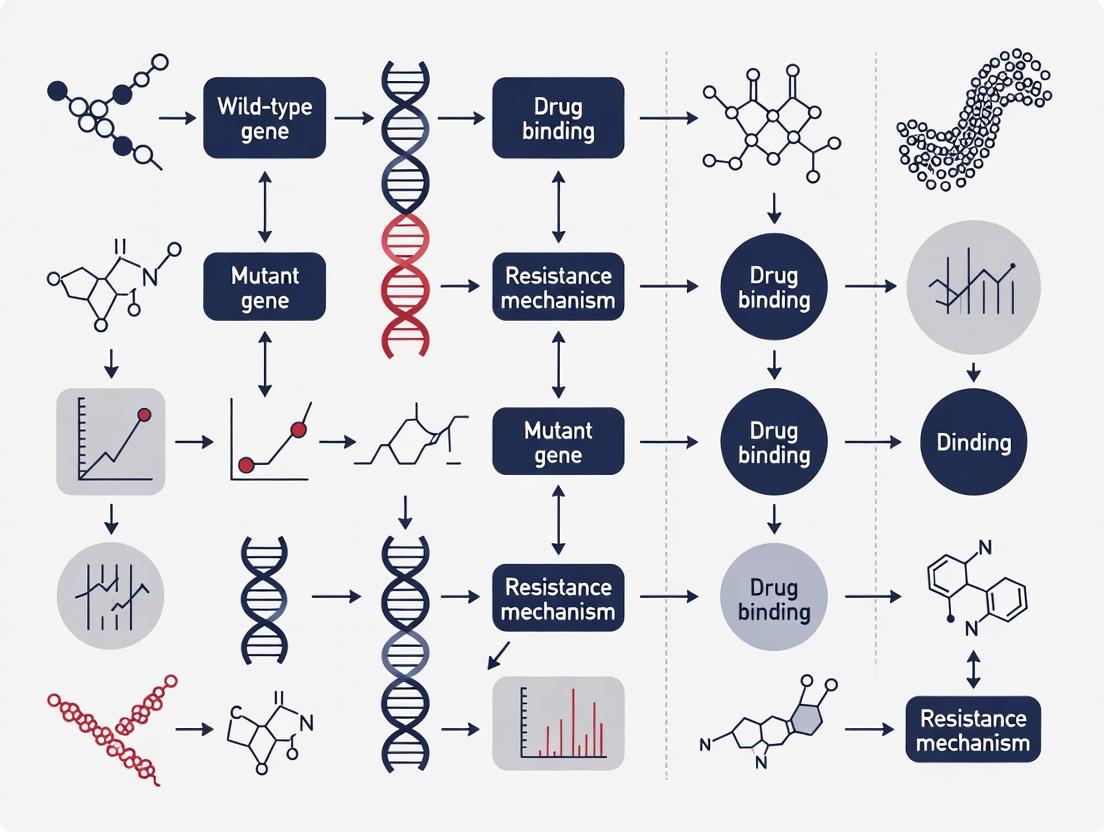

Experimental Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for a computational research project aimed at improving the prediction of drug-resistant tuberculosis.

Research Workflow for TB Resistance Prediction

This workflow shows the parallel paths of machine learning and molecular dynamics simulation, which converge to produce a validated resistance prediction.

TIES_PM Resistance Prediction Logic

### Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the current gold standard for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (AST) and why is it considered the reference method?

The gold standard for AST, as recommended by the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) and the Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI), is culture-based techniques [6]. This includes both broth dilution and agar dilution methods [7]. These methods are considered the reference because they directly measure the phenotypic response of bacteria to antibiotics, determining the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC), which is the lowest concentration of an antibiotic that prevents visible bacterial growth [7]. The MIC provides a quantitative result that is used to categorize isolates as susceptible, intermediate, or resistant, forming the basis for effective antimicrobial treatment [7].

FAQ 2: What are the primary limitations of relying on culture-based AST?

While definitive, culture-based methods have several significant drawbacks that can impact patient care and resistance research [6] [7].

- Prolonged Turnaround Time: These methods are slow, typically requiring 18–24 hours for results after the initial bacterial isolation, and can take up to 48 hours for slow-growing or fastidious bacteria [7]. This delay often forces physicians to prescribe empirical, broad-spectrum antibiotic therapies, which may be inappropriate or unnecessary [6] [8].

- Limited Functional Information: Culture-based AST confirms resistance but does not identify the specific genetic or biochemical mechanism behind it. This limits its utility for in-depth research into resistance prediction and evolution [6].

- Inability to Culture Some Pathogens: The method relies on the ability to isolate and grow the bacterial strain of interest from a complex clinical sample. It is unsuitable for non-culturable organisms or mixed infections [6].

- Labor and Resource Intensity: These techniques are laborious and require significant hands-on time from laboratory staff, especially when testing multiple antibiotics [6].

FAQ 3: How do the limitations of culture-based methods impact clinical decision-making and public health surveillance?

The slow turnaround time of culture-based AST directly contributes to the empirical overuse of antibiotics [6]. Studies estimate that 30–50% of antibiotic prescriptions are inappropriate or unnecessary [6]. Furthermore, the labor-intensive nature of these methods can delay the surveillance of emerging resistant pathogens, such as MRSA, VRE, and carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales, hindering the effectiveness of public health interventions and antimicrobial stewardship programs [7].

FAQ 4: What advanced methodologies are emerging to address these limitations?

To overcome the constraints of culture-based AST, several advanced technologies are being integrated into research and clinical practice [6] [8]:

- Whole-Genome Sequencing (WGS): WGS can rapidly identify pathogens and predict resistance profiles by detecting known resistance genes in a single assay without a culturing step. However, its limitation is that it only predicts the presence of resistance genes, which may not always be expressed into a resistance phenotype [6].

- Machine Learning (ML) and Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI): Frameworks like xAI-MTBDR use ML models to not only predict drug resistance with high accuracy but also explain the contribution of individual mutations, helping to identify new resistance markers [9].

- Multivariable Regression Models: These statistical models improve the grading of antibiotic resistance mutations by associating resistance phenotypes with variants in candidate genes, even when multiple mutations co-occur. This approach has been shown to achieve higher sensitivity than traditional univariate methods [10].

### Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Issue: Contamination or Mixed Growth in Culture Plates

Problem: A high percentage of samples, such as urine cultures, result in "mixed growth" and cannot be analyzed, drastically reducing the yield of usable AST results [11]. One study found that 35% of urine samples showed mixed growth [11].

Solution:

- Ensure Proper Sample Collection: Educate clinicians on clean-catch midstream urine collection techniques to minimize skin and genital flora contamination.

- Use Selective Media: Employ chromogenic agars or media containing inhibitors to suppress the growth of commensal bacteria and selectively isolate common uropathogens.

- Optimize Inoculation Protocol: Standardize the loop size and streaking technique to obtain well-isolated colonies.

Issue: Slow Turnaround Time Affecting Research Timelines

Problem: The 18-48 hour wait for phenotypic results is slowing down research projects, especially those screening large numbers of bacterial isolates.

Solution:

- Implement Complementary Rapid Methods:

- PCR and NAATs: Use targeted molecular assays for known resistance genes (e.g., mecA for methicillin resistance) to get results within 1–6 hours [7].

- MALDI-TOF MS: Utilize this technology for rapid pathogen identification, which can be combined with novel protocols to assess resistance mechanisms based on protein profiles [6] [8].

- Adopt Automated AST Systems: While still based on bacterial growth, these systems can provide MIC results faster (within 6–24 hours) than manual methods by using sensitive optical detection systems [7].

Issue: Detecting Resistance in Non-Culturable or Fastidious Bacteria

Problem: Some bacterial species are difficult or impossible to culture using standard techniques, creating a blind spot in resistance monitoring.

Solution:

- Utilize Direct-from-Specimen Molecular Testing:

- Line Probe Assays (LPAs): Use these for direct detection of resistance mutations from sediment samples, though be aware that their sensitivity can be lower than newer methods [12].

- Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing (tNGS): Apply tNGS workflows directly to clinical samples. This method has demonstrated higher sensitivity than LPAs for detecting resistance to key drugs like rifampicin and isoniazid in tuberculosis [12].

### Comparison of AST Methods

The following table summarizes the key characteristics of established and emerging AST methodologies.

Table 1: Comparison of Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing Methods

| Method Category | Example Techniques | Typical Turnaround Time | Key Advantages | Key Limitations / Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenotypic (Gold Standard) | Broth/Agar Dilution, Disk Diffusion [7] | 18-48 hours [7] | Direct measure of phenotypic response; low consumable cost; standardized interpretation [6] [8] | Slow; labor-intensive; cannot detect underlying genetic mechanisms [6] |

| Automated Phenotypic | Various commercial systems (e.g., VITEK, Phoenix) | 6-24 hours [7] | Faster than manual methods; reduced labor; standardized and reproducible [7] | High instrument cost; limited customization of test panels [7] |

| Molecular | PCR, NAATs, Line Probe Assays (LPAs) [7] [12] | 1-6 hours [7] | Very fast; high specificity for targeted genes; can be used directly on some samples [7] [12] | Only detects known targets; cannot differentiate between expressed and silent genes; can overestimate resistance [6] [7] |

| Sequencing-Based | Whole-Genome Sequencing (WGS), Targeted NGS (tNGS) [6] [12] | 1-3 days (library prep & sequencing) | Comprehensive; detects known and novel mutations; high-resolution strain typing [6] [13] | High cost per sample for low-throughput; complex data analysis; predictive only (genotype vs. phenotype) [6] |

| Spectrometry-Based | MALDI-TOF MS [6] [8] | Minutes after pure culture | Extremely fast identification; potential for resistance mechanism detection [6] | Generally requires pure culture; limited validated protocols for direct AST [6] |

### Experimental Workflow & Key Research Reagents

The following diagram illustrates a generalized research workflow that integrates classical and modern methods to overcome the limitations of culture-based AST, accelerating resistance mutation research.

Diagram: Integrated Research Workflow for Resistance Mutation Discovery.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Key Experimental Steps

| Research Tool / Reagent | Function in Experiment | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Selective Culture Media | Isolates target pathogen from complex samples; provides pure biomass for WGS and the gold-standard phenotypic result (MIC) [6]. | Chromogenic agars for ESKAPE pathogens; Lowenstein-Jensen medium for M. tuberculosis. |

| Broth Microdilution Plates | Determine the reference Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) for the isolated bacterial strain against a panel of antibiotics [7]. | Custom plates can be designed to include antibiotics of research interest. CLSI/EUCAST guidelines provide standard protocols. |

| DNA Extraction Kits | Prepares high-quality, pure genomic DNA for downstream sequencing applications. | Critical for minimizing inhibitors and ensuring high sequencing coverage. |

| Whole-Genome Sequencer | Generates comprehensive genomic data to identify single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), insertions/deletions (indels), and resistance genes [6] [13]. | Illumina platforms (e.g., MiSeq) for high accuracy; Oxford Nanopore (e.g., MiniON) for long reads and portability [6]. |

| Bioinformatics Databases & Tools | Annotates sequencing data and predicts resistance profiles by comparing against curated databases of known resistance elements [6]. | CARD (Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database), ResFinder, AMRFinderPlus [6]. Mykrobe and TBProfiler for M. tuberculosis [10]. |

| Machine Learning Frameworks | Builds predictive models that associate complex genetic signatures with resistance phenotypes, identifying novel markers beyond simple gene presence [10] [9]. | Frameworks like xAI-MTBDR use SHAP values to explain model predictions, revealing the contribution of individual mutations [9]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most common types of genetic mutations that cause drug resistance? Drug resistance mutations are often single nucleotide variants (SNVs) in the drug target or proteins within the same signaling pathway [14]. These can be categorized into four main functional classes [14]:

- Canonical drug resistance variants: Confer a proliferation advantage only in the presence of the drug, often by disrupting drug binding.

- Driver variants: Confer a proliferation advantage both in the presence and absence of the drug.

- Drug addiction variants: Provide an advantage in drug presence but are deleterious without it, often leading to oncogene-induced senescence when untreated.

- Drug-sensitizing variants: Are deleterious only when the drug is present.

Q2: Why do some less fit resistance mutations (like E255K in BCR-ABL) become prevalent in patient populations? The prevalence is not always determined by the fitness advantage a mutation confers. A key factor is mutational bias—the inherent likelihood of a specific nucleotide change occurring [15]. For example, the E255K mutation in BCR-ABL, which confers less resistance than the E255V mutation, is more common clinically because the DNA change required for E255K (a G>A transition) is more probable than the change for E255V (an A>T transversion) [15]. This highlights that evolutionary outcomes can be influenced by the underlying probabilities of mutations.

Q3: How can we systematically discover and validate novel drug resistance mechanisms? CRISPR base editing mutagenesis screens are a powerful, prospective method [14]. This involves:

- Library Design: Using a guide RNA (gRNA) library to install thousands of specific single-nucleotide variants in relevant cancer genes.

- Functional Screening: Introducing this library into cancer cell lines and growing them in the presence of a drug.

- Hit Identification: Sequencing the pooled cells to identify gRNAs (and thus mutations) that are enriched, indicating they confer resistance. This approach allows for the systematic functional annotation of variants of unknown significance before they are observed in the clinic [14].

Q4: What is the clinical significance of identifying "drug addiction variants"? Drug addiction variants, which are beneficial for cancer cells in the presence of a drug but harmful in its absence, suggest a potential therapeutic strategy of intermittent drug scheduling (drug holidays) [14]. By temporarily withdrawing the drug, clones harboring these variants could be selectively eliminated from the tumor population, thereby delaying or overcoming resistance [14].

Q5: Where can I find consolidated data on mutations and their impact on drug binding affinity? The MdrDB database is a comprehensive resource that integrates data on mutation-induced drug resistance [16]. It contains over 100,000 samples, including 3D structures of wild-type and mutant protein-ligand complexes, changes in binding affinity (ΔΔG), and biochemical features. It covers 240 proteins, 2,503 mutations, and 440 drugs [16].

Troubleshooting Experimental Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting In Vitro Resistance Screens

Problem: Unexpected or no resistance hits in a base editing screen.

| Step | Action | Expected Outcome & Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Verify base editor activity. Check efficiency of variant installation using targeted sequencing of control gRNAs. | Low editing efficiency will cause a weak signal. Ensure your cell line expresses the base editor effectively. |

| 2 | Confirm drug pressure. Perform a kill curve assay to establish the optimal drug concentration for screening. It should efficiently suppress wild-type cell growth. | If the concentration is too low, resistance mutations will not be enriched. If too high, no cells will survive. |

| ... | ... | ... |

Guide 2: Interpreting Variants of Unknown Significance (VUS)

Problem: A novel mutation is identified in a patient post-treatment, but its functional impact is unknown.

| Step | Action | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Classify the variant. Map the mutation to the protein's functional domains (e.g., kinase domain, ATP-binding pocket). | Refer to databases like MdrDB [16] or previous base editing screens [14] to see if similar mutations are documented. |

| 2 | Model the structural impact. Use computational tools to model the mutant protein and assess potential effects on drug binding. | A mutation in the drug-binding pocket is likely a canonical resistance variant. A distal mutation may affect allostery. |

| ... | ... | ... |

Key Experimental Data and Protocols

The following table summarizes the four classes of variants modulating drug sensitivity, as identified through large-scale base editing screens [14].

| Variant Class | Proliferation in Drug | Proliferation in No Drug | Example Mutations | Clinical/Experimental Implication |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canonical Drug Resistance | Advantage | Neutral | MEK1 L115P, EGFR S464L | Directly disrupts drug binding; classic on-target resistance. |

| Driver Variant | Advantage | Advantage | KRAS G12C, BRAF V600E | Often pre-existing or acquired activating mutations in the pathway. |

| Drug Addiction Variant | Advantage | Deleterious | KRAS Q61R, MEK2 Y134H | Suggests potential for intermittent dosing ("drug holidays"). |

| Drug-Sensitizing Variant | Deleterious | Neutral | Loss-of-function in EGFR | Reveals effective drug combinations (e.g., EGFR + BRAF inhibitors). |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Resource | Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Base Editors (CBE, ABE) | Installs precise C>T or A>G point mutations in the genome without causing double-strand breaks [14]. | Saturation mutagenesis of a kinase domain to prospectively identify resistance mutations. |

| gRNA Mutagenesis Library | A pooled library of guide RNAs designed to "tile" target genes and install specific variants [14]. | Functional screens to simultaneously test thousands of variants for their effect on drug sensitivity. |

| MdrDB Database | A comprehensive database providing 3D structures, binding affinity changes (ΔΔG), and biochemical features for mutant proteins [16]. | Benchmarking newly discovered mutations and training machine learning models for predicting ΔΔG. |

Detailed Protocol: CRISPR Base Editing Resistance Screen

Objective: Prospectively identify genetic variants that confer resistance to a targeted cancer therapy.

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Methodology [14]:

Library and Cell Line Preparation

- gRNA Library Design: Design a library that tiles the coding sequences of your target genes (e.g., 11 cancer genes in a pathway). The library should include nontargeting gRNAs and gRNAs targeting essential and nonessential genes as controls.

- Cell Line Selection: Choose a cancer cell line that is sensitive to the drug of interest and harbors a relevant oncogenic driver (e.g., a BRAF V600E mutation for a BRAF inhibitor). Generate a stable cell line expressing a doxycycline-inducible cytidine base editor (CBE) or adenine base editor (ABE).

Screen Execution

- Virus Production & Transduction: Produce lentivirus from the gRNA library and transduce the cell line at a low multiplicity of infection (MOI) to ensure most cells receive a single gRNA.

- Base Editor Induction & Drug Selection: Induce base editor expression with doxycycline. Split the transduced cells into two arms: one treated with the drug at a predetermined IC90 concentration, and a vehicle-treated control. Culture cells for several population doublings to allow for enrichment of resistant clones.

Analysis and Validation

- Genomic DNA Extraction and Sequencing: Harvest genomic DNA from both arms at the end of the screen. Amplify the integrated gRNA sequences and subject them to next-generation sequencing.

- Differential Abundance Analysis: Align sequences to the gRNA library and count reads for each gRNA. Use statistical packages to identify gRNAs that are significantly enriched in the drug-treated arm compared to the control arm.

- Hit Validation: Clone top-hit gRNAs into vectors for arrayed validation. Transduce naive cells and perform proliferation assays in the presence and absence of drug to confirm the resistance phenotype.

Signaling Pathways and Logical Diagrams

Logical Map of Drug Resistance Variant Classification

This diagram illustrates the decision process for classifying a newly identified resistance variant based on its functional impact on cell proliferation.

Simplified MAPK Signaling Pathway with Resistance Nodes

This diagram shows key nodes in the MAPK pathway where mutations can confer resistance to targeted therapies like BRAF or MEK inhibitors.

The Role of Next-Generation Sequencing in Uncovering Resistance Variants

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized the detection and analysis of genetic variants that confer resistance to therapeutic agents in cancer and infectious diseases. By enabling the simultaneous sequencing of millions of DNA fragments, NGS provides comprehensive insights into genome structure, genetic variations, and dynamic changes that occur under therapeutic pressure [17]. This high-throughput, cost-effective technology has become a fundamental tool for researchers aiming to understand the molecular mechanisms of drug resistance and to improve prediction accuracy for resistance mutations.

The versatility of NGS platforms has expanded the scope of resistance research, facilitating studies on rare genetic diseases, cancer genomics, microbiome analysis, and infectious diseases [17]. In clinical oncology, NGS has been instrumental in identifying disease-causing variants, uncovering novel drug targets, and elucidating complex biological phenomena including tumor heterogeneity and the emergence of treatment-resistant clones [17]. Similarly, in antimicrobial resistance (AMR) research, NGS provides powerful capabilities to identify low-frequency variants and genomic arrangements in pathogens that confer resistance to antimicrobial drugs [18].

Key NGS Approaches and Methodologies

Sequencing Technologies and Platforms

NGS encompasses several sequencing approaches, each with distinct advantages for specific applications in resistance research:

Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) provides the most comprehensive approach by covering the entire genome, enabling investigation of previously undescribed genomic alterations across coding and non-coding regions [19]. This method is particularly valuable for identifying novel resistance mechanisms and structural variations. Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) focuses on protein-coding regions (approximately 3% of the genome), offering a cost-effective alternative with the assumption that protein-associated alterations often have deleterious impacts on gene function and drug response [19]. Targeted Sequencing (TS) analyzes specific mutational hotspots or genes of interest with high sensitivity and depth, making it ideal for focused resistance panels and monitoring known resistance-associated variants [19] [20].

The performance characteristics of major NGS platforms vary significantly, influencing their suitability for different resistance research applications:

Table 1: Comparison of NGS Platforms for Resistance Variant Detection

| Platform | Technology | Read Length | Key Applications in Resistance Research | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina | Sequencing-by-synthesis | 36-300 bp | High-accuracy SNV and indel detection; targeted panels | May have increased error rate (up to 1%) with sample overloading [17] |

| Ion Torrent | Semiconductor sequencing | 200-400 bp | Rapid screening of known resistance hotspots | May lose signal strength with homopolymer sequences [17] |

| PacBio SMRT | Single-molecule real-time sequencing | 10,000-25,000 bp | Identifying complex structural variants and resistance gene rearrangements | Higher cost compared to other platforms [17] |

| Nanopore | Electrical impedance detection | 10,000-30,000 bp | Real-time resistance monitoring; direct RNA sequencing | Error rate can spike up to 15% [17] |

Experimental Workflows for Resistance Studies

A typical NGS workflow for resistance variant detection involves multiple critical steps, each contributing to the overall accuracy and reliability of results:

Sample Preparation and Quality Control: The initial step involves nucleic acid extraction from relevant samples (tumor tissues, blood, microbial cultures) followed by rigorous quality assessment. For solid tumors, microscopic review by a pathologist is essential to ensure sufficient tumor content and to guide macrodissection or microdissection to enrich tumor fraction [21]. DNA quality is typically assessed through fluorometric quantification and measurement of DNA Integrity Number (DIN), with most clinical assays requiring a DIN value above 2-3 [22].

Library Preparation: Two major approaches are used for targeted NGS analysis: hybrid capture-based and amplification-based methods [21]. Hybrid capture utilizes biotinylated oligonucleotide probes complementary to regions of interest, offering better tolerance for sequence variations and reduced allele dropout compared to amplification-based methods [21]. This approach is particularly valuable for detecting novel resistance mutations. The library preparation process includes DNA fragmentation, adapter ligation with unique molecular indexes (UMIs), and PCR amplification [22].

Sequencing and Data Analysis: Sequencing generates raw data in FASTQ format, which undergoes quality control using tools like FastQC [19]. Subsequent steps include read alignment to a reference genome, duplicate read removal, local realignment, and variant calling using specialized algorithms [19]. The final variants are annotated and interpreted for their potential role in resistance mechanisms.

The following diagram illustrates the complete NGS workflow for resistance variant detection:

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Pre-analytical and Experimental Issues

Q: What are the minimum DNA quantity and quality requirements for reliable resistance variant detection? A: For targeted NGS panels, most validated assays require ≥50 ng of DNA input to detect all expected mutations with appropriate variant allele frequencies. When DNA input drops to ≤25 ng, sensitivity decreases significantly, with only approximately 60% of variants detected [20]. DNA quality should be assessed through fluorometric quantification and measurement of DNA Integrity Number (DIN), with most clinical assays requiring a DIN value above 2-3 [22]. For degraded samples from FFPE tissue, optimization of extraction protocols and consideration of specialized library preparation kits designed for damaged DNA are recommended.

Q: How can we ensure adequate detection of low-frequency resistance variants? A: Several strategies enhance low-frequency variant detection: (1) Utilize unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) to distinguish true low-frequency variants from PCR artifacts and sequencing errors [22]; (2) Ensure sufficient sequencing depth—most validated clinical panels achieve median coverages of 1000-2000x [20]; (3) Establish appropriate limit of detection (LOD) thresholds, typically around 2.9-5% variant allele frequency for single nucleotide variants and indels [20]; (4) Implement duplex sequencing methods for ultra-sensitive detection when monitoring minimal residual disease or early resistance emergence.

Q: What controls should be included in each sequencing run to monitor assay performance? A: Each sequencing run should include: (1) Positive control materials with known variants at predetermined allele frequencies (e.g., HD701 reference standard containing 13 mutations) to verify detection sensitivity [20]; (2) Negative controls to identify contamination or background noise; (3) Internal quality metrics including percentage of reads with quality scores ≥Q30 (should be >85-99%), percentage of target regions with coverage ≥100x (should be >98%), and coverage uniformity (>99%) [20] [23].

Analytical and Bioinformatics Challenges

Q: How do we distinguish true resistance variants from technical artifacts? A: Implement a multi-faceted filtering approach: (1) Remove variants present in negative control samples; (2) Filter out low-quality calls based on base quality scores, mapping quality, and strand bias; (3) Exclude variants with allele frequencies below the validated LOD of the assay; (4) Compare with population databases (e.g., gnomAD) to exclude common polymorphisms; (5) Utilize orthogonal validation for clinically actionable findings using methods like digital PCR or Sanger sequencing [21] [19].

Q: What bioinformatics tools are recommended for different variant types in resistance research? A: The optimal bioinformatics pipeline depends on variant type:

Table 2: Bioinformatics Tools for Resistance Variant Detection

| Variant Type | Recommended Tools | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| SNVs/Indels | GATK Mutect2, VarScan2, LoFreq | Combine multiple callers to increase sensitivity; implement strict filtering to reduce false positives [19] |

| Copy Number Variations | CNVkit, ADTEx | Requires careful normalization against control samples; performance depends on tumor purity and panel design [22] [21] |

| Gene Fusions/Structural Variants | Arriba, STAR-Fusion, DELLY | DNA-based approaches require intronic coverage; RNA sequencing often provides more direct fusion detection [21] |

| Complex Biomarkers | MSIsensor (MSI), TMBcalc (Tumor Mutational Burden) | Require specific computational approaches and reference datasets for accurate quantification [22] [19] |

Q: How should NGS assays be validated for clinical resistance testing? A: The Association of Molecular Pathology (AMP) and College of American Pathologists (CAP) provide comprehensive guidelines for NGS validation [21]. Key requirements include: (1) Establishing accuracy, precision, sensitivity, and specificity using well-characterized reference materials; (2) Determining the limit of detection for different variant types using dilution series; (3) Assessing reproducibility through repeat testing; (4) Validating all bioinformatics steps and pipelines; (5) Establishing quality control metrics and thresholds for ongoing monitoring [21] [23]. Performance standards should demonstrate >99% sensitivity and specificity for variant detection at the established LOD [20].

Advanced Research Applications

Functional Validation of Resistance Mechanisms

While NGS can identify potential resistance variants, functional validation is essential to establish causality. Advanced approaches like CRISPR base editing enable systematic analysis of variant effects on drug sensitivity [14]. Recent studies have used base editing screens to map functional domains in cancer genes and classify resistance variants into distinct functional categories:

Drug Addiction Variants: Confer proliferation advantage in drug presence but are deleterious without drug (e.g., KRAS Q61R in BRAF-mutant cells with trametinib treatment) [14].

Canonical Drug Resistance Variants: Provide selective advantage only in drug presence, typically within drug-binding pockets (e.g., MEK1 L115P disrupting trametinib binding) [14].

Driver Variants: Confer growth advantage regardless of drug presence, often activating orthogonal signaling pathways [14].

Drug-Sensitizing Variants: Enhance drug sensitivity, representing potential synthetic lethal interactions (e.g., EGFR loss-of-function variants in BRAF-mutant colorectal cancer sensitizing to BRAF/MEK inhibitors) [14].

The following diagram illustrates how these variant classes interact with treatment response:

Case Study: NGS in Esophageal Cancer Resistance Research

A compelling example of NGS application in resistance research comes from a study of neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) in esophageal cancer (EC) [24]. Researchers performed targeted NGS on samples from 13 EC patients with different responses to platinum-based NAC, identifying missense mutations in the NOTCH1 gene associated with chemotherapy resistance [24]. Protein conformational analysis revealed that these mutations altered the NOTCH1 receptor protein's ability to bind ligands, potentially causing abnormalities in the NOTCH1 signaling pathway and conferring resistance [24].

This case study demonstrates several best practices: (1) Sequencing paired samples (pre- and post-treatment) to identify acquired resistance mutations; (2) Focusing on a targeted gene panel (295 genes) for cost-effective deep sequencing; (3) Integrating computational structural biology to elucidate functional consequences; (4) Correlating genetic findings with clinical response categories (complete response, partial response, stable disease) [24].

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for NGS-based Resistance Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Resistance Research |

|---|---|---|

| NGS Library Prep Kits | SureSelect XT HS (Agilent), Illumina DNA Prep | Convert extracted DNA into sequencing-ready libraries with unique molecular indexes for accurate variant detection [22] |

| Target Enrichment Panels | OncoScreen (295 genes), AmpliSeq for Illumina Antimicrobial Resistance Panel (478 genes), Custom panels (e.g., 61-gene oncopanel) | Enrich specific genomic regions of interest related to resistance mechanisms in cancer or pathogens [24] [22] [18] |

| Reference Standards | HD701 (Horizon Discovery), Coriell Cell Repositories | Provide known variants at predetermined allele frequencies for assay validation and quality control [22] [20] |

| DNA/RNA Extraction Kits | QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen), RecoverAll Total Nucleic Acid Isolation Kit (FFPE) | Extract high-quality nucleic acids from various sample types including challenging FFPE specimens [24] [22] |

| Bioinformatics Tools | GATK, FastQC, BCFtools, Sophia DDM | Quality control, variant calling, and annotation of sequencing data to identify resistance-associated variants [19] [20] |

| Functional Screening Tools | CRISPR base editors (CBE, ABE), gRNA libraries targeting cancer genes | Systematically test the functional impact of variants on drug resistance in high-throughput screens [14] |

Next-generation sequencing has become an indispensable tool for uncovering the genetic basis of resistance to therapeutics in cancer and infectious diseases. The integration of robust NGS methodologies with functional validation approaches enables researchers to move beyond correlation to establish causal mechanisms of resistance. As the field advances, key areas of development include the standardization of bioinformatics pipelines, implementation of quality management systems [23], and the creation of comprehensive variant-to-function maps through technologies like base editing screens [14].

The evolving landscape of NGS technologies promises enhanced accuracy, reduced costs, and improved data analysis solutions that will further advance resistance mutation research [17]. By implementing the troubleshooting guidelines, experimental protocols, and quality control measures outlined in this technical resource, researchers can enhance the accuracy and reliability of their resistance variant predictions, ultimately contributing to more effective therapeutic strategies and improved patient outcomes.

Frequently Asked Questions & Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: Why do my multidrug-resistant bacterial strains sometimes adapt faster in antibiotic-free media than single-resistant strains?

Answer: Multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacteria with high fitness costs can undergo faster compensatory evolution than single-resistant strains. This occurs because the strong negative epistasis (where the combined cost of two mutations is greater than the sum of their individual costs) in MDR strains opens alternative evolutionary paths.

- Underlying Cause: Low-fitness MDR strains can acquire compensatory mutations with larger fitness effects [25]. Furthermore, some compensatory mutations are specific to the MDR background; they are beneficial only when both resistance mutations are present and are neutral or even deleterious in sensitive or single-resistant backgrounds [25].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Monitor Competition Assays: When propagating MDR strains in permissive conditions, use competitive fitness assays against a neutral marker strain to detect rapid fitness increases.

- Check for Epistasis: Determine if the fitness cost of your MDR strain is synergistic (negative epistasis), as this creates a strong selective pressure for rapid compensation.

- Genomic Verification: Sequence evolved lineages to identify whether compensatory mutations have occurred in genes functionally linked to the epistatic interaction between the two resistance mechanisms.

FAQ 2: How can I reliably predict cross-resistance and collateral sensitivity between antibiotics?

Answer: Predicting these interactions is challenging because a single drug pair can exhibit cross-resistance (XR) or collateral sensitivity (CS) depending on the specific resistance mechanism involved [26]. Relying on a single experimental evolution lineage can be misleading.

- Underlying Cause: Different mutations conferring resistance to the same first drug can have diverse pleiotropic effects on susceptibility to a second drug [27]. One mutant may show CS to drug B, while another mutant resistant to the same drug A may show XR to drug B.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Use Diverse Lineages: Evolve multiple independent lineages against the first antibiotic to sample a broader range of resistance mechanisms.

- Mechanism-Based Stratification: Group evolved strains by their identified resistance mechanisms (e.g., via whole-genome sequencing) before testing their susceptibility to the second drug.

- Leverage Chemical Genetics Data: Consult existing chemical genetics profiles, which systematically show how the loss of each non-essential gene affects resistance, to predict XR (concordant profiles) and CS (discordant profiles) [26].

FAQ 3: My genotypic prediction of drug resistance misses some phenotypically resistant strains. How can I improve accuracy?

Answer: This is a common issue where current genotypic catalogs of resistance mutations are incomplete. The solution is to move beyond single-mutation lookups and use integrated, model-based approaches.

- Underlying Cause: Phenotypic resistance can be caused by novel mutations or complex genetic interactions not yet listed in standard mutation catalogs [28].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Employ Ensemble Models: Combine the predictions of multiple computational tools (e.g., the WHO catalog, TB-Profiler, SAM-TB, and machine learning tools like GenTB or MD-CNN) using a stacking ensemble framework. This has been shown to outperform any single tool [28].

- Incorporate Population Structure: For bacteria like E. coli, include data on population structure and gene content in machine learning models, as this can significantly boost prediction accuracy [29].

- Investigate Unexplained Resistance: For strains that are phenotypically resistant but genotypically susceptible, identify recurring mutations in your dataset that meet a minimum frequency threshold as candidates for novel resistance markers [28].

Key Experimental Data

Table 1: Dynamics of Compensatory Evolution in Single vs. Double ResistantE. coli

Data derived from experimental evolution in antibiotic-free media, tracking the pace of adaptation [25].

| Resistant Background | Fitness Cost (Initial) | Time to First Adaptive Signature (Days) | Fitness Increase per Day (Day 0-5) | Presence of Epistasis-Specific Compensatory Mutations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rifampicin (RifR) Single | 0.06 ± 0.001 | 8-10 (in minority of populations) | Lower than double-resistant | No |

| Streptomycin (StrR) Single | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 8-10 (in minority of populations) | Lower than double-resistant | No |

| RifR StrR Double | 0.27 ± 0.01 (Strong Negative Epistasis) | 4 (in all populations) | 0.048 ± 0.003 | Yes |

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Genotypic Drug Susceptibility Testing (DST) Tools forM. tuberculosis

Evaluation of five tools on a global dataset of 36,385 isolates shows that ensemble models achieve the highest accuracy [28].

| Prediction Tool / Method | Overall AUC (%) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Key Characteristic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WHO Mutation Catalog (2023) | Not the highest | 79.5 | 97.3 | Highest specificity; catalog-based |

| TB Profiler | High | 79.5 | Not the highest | Best sensitivity; catalog-based |

| MD-CNN | 92.1 | Not the highest | Not the highest | Best overall AUC; deep learning-based |

| Ensemble Model (Stacking) | 93.4 | 84.1 | 95.4 | Combines all five tools; outperforms individual methods |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Tracking Compensatory Evolution via Neutral Marker Competition

Objective: To quantify the pace and dynamics of compensatory adaptation in resistant bacterial strains [25].

- Strain Preparation: Construct isogenic resistant clones (e.g., single RifR, single StrR, and double RifR StrR) each carrying two different neutral markers, such as genes for Cyan (CFP) and Yellow (YFP) fluorescent proteins.

- Experimental Evolution:

- Initiate independent evolving populations by mixing CFP and YFP variants of the same resistant genotype at a 1:1 ratio.

- Propagate populations in antibiotic-free liquid medium for ~180 generations (e.g., 22 days), performing daily dilutions to maintain a large population size and allow for clonal interference.

- Frequency Monitoring: Regularly sample populations and use flow cytometry to track the frequencies of the CFP and YFP markers.

- Data Interpretation:

- A rapid and steep change in marker frequency indicates a selective sweep by a beneficial (compensatory) mutation.

- Strong fluctuations in both markers suggest clonal interference, where multiple beneficial mutations arise and compete.

- Fitness Validation: Periodically perform head-to-head competition assays between evolved populations and a non-fluorescent sensitive ancestor to directly measure the increase in competitive fitness.

Protocol 2: Systematically Mapping Cross-Resistance and Collateral Sensitivity

Objective: To identify and validate drug-pair interactions using a chemical genetics-informed approach [26].

- Data Acquisition: Obtain chemical genetics data (e.g., s-score profiles) for a library of gene knockout mutants exposed to your antibiotics of interest.

- Metric Calculation: For each drug pair (A, B), calculate the Outlier Concordance-Discordance Metric (OCDM). This metric emphasizes extreme scores:

- Concordance: Mutants with significantly negative s-scores for both drugs suggest a shared resistance mechanism (predicts Cross-Resistance, XR).

- Discordance: Mutants with significantly negative s-scores for drug A but positive for drug B (or vice versa) suggest a trade-off (predicts Collateral Sensitivity, CS).

- Experimental Evolution for Validation:

- Evolve multiple independent lineages against a first drug (Drug A).

- Measure the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) of the evolved lineages against both Drug A and a second drug (Drug B).

- Interaction Calling: For each evolved lineage, classify the interaction with Drug B as XR (increased MIC), CS (decreased MIC), or neutral (no change in MIC).

- Mechanism Deconvolution: Sequence evolved lineages and correlate the identified resistance mutations with their specific XR/CS profiles to understand the underlying mechanisms.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for Studying Resistance Evolution

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Barcoded Strain Libraries | Enables high-resolution tracking of numerous adaptive lineages in evolution experiments, capturing a fuller spectrum of beneficial mutations [27]. | Used in yeast to identify hundreds of unique fluconazole-resistant mutants and group them by fitness trade-offs. |

| Neutral Fluorescent Markers (CFP/YFP) | Allows real-time monitoring of selective sweeps and clonal interference during experimental evolution in a single flask [25]. | |

| Chemical Genetics Profiles | Pre-compiled datasets showing fitness of genome-wide mutants under drug treatment; used to predict XR/CS [26]. | E. coli Keio collection s-scores for 40 antibiotics. |

| Ensemble Prediction Models | A computational framework that combines multiple genotypic DST tools to improve resistance prediction accuracy [28]. | A stacking model with a decision tree meta-classifier outperformed individual tools for TB resistance prediction. |

| Deep Learning Models (e.g., LSTM) | Analyzes complex genetic data (e.g., WGS SNPs) to predict multi-drug resistance status from sequencing data [29]. | aiGeneR 3.0 model for E. coli UTI pathogens. |

Experimental Workflow & Conceptual Diagrams

Compensatory Evolution in MDR Strains

Predicting XR/CS from Chemical Genetics

Ensemble Model for Genotypic DST

Leveraging Machine Learning and AI for Predictive Modeling

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the primary genomic data sources used in drug resistance research? Large-scale public databases are fundamental. Research often utilizes genomic data (including gene expression profiles, mutational landscapes, and copy number variations) from resources such as the Dependency Map (DepMap) project database, the Cancer Therapeutic Response Portal (CTRP v2), and the Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer (GDSC) database, which encompass hundreds of cancer cell lines [30].

2. How can gene expression data be standardized for robust predictive modeling? To improve compatibility across datasets, employ preprocessing strategies such as log transformation and scaling of gene expression values to a uniform range. Dimensionality reduction techniques, like autoencoders, can further extract key features and minimize data source-specific variability, enhancing model generalizability [30].

3. Why might the most clinically abundant resistance mutation not be the one that confers the highest resistance? Evolutionary outcomes are not determined by fitness (resistance level) alone. A mutation that provides slightly less resistance may become more prevalent if its underlying nucleotide change is more likely to occur (e.g., a transition like G>A versus a transversion like A>T). Quantitative models must account for this mutational bias to accurately predict epidemiological abundance [15].

4. What is the advantage of integrating transcriptomic profiles with genomic data? While genomics identifies potential resistance mutations, transcriptomics reveals the functional expression of genes driving resistance mechanisms. Integrating both provides a more complete picture, helping to elucidate how mutations actually impact cellular pathways and drug response [30].

5. When should spatial transcriptomics be considered over single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq)? Spatial transcriptomics is preferred when preserving the spatial context of cells within intact tissue is critical, such as for studying the tumor microenvironment, cell-cell interactions, or localized disease mechanisms. It is also invaluable for studying cell types that are difficult to isolate viable for scRNA-seq, like neurons [31].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Inconsistent Drug Response Predictions Across Datasets

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Batch effects from different data sources. | Perform Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to see if samples cluster by dataset source rather than biological type. | Apply robust scaling and normalization (e.g., log transformation). Use batch correction algorithms or autoencoders to extract source-invariant features [30]. |

| Incompatible data normalization methods. | Check the original literature or database documentation for the processing pipelines used on each dataset. | Re-process raw data from different sources through a unified, standardized pipeline before integration and analysis [30]. |

| High variability in control data. | Review the coefficient of variation (CV) for control samples or replicate assays within the original datasets. | During data curation, exclude assay data that shows considerable variability within biologically homogeneous clusters for the same drugs [30]. |

Issue 2: Failure to Replicate Clinically Observed Resistance Mutations in Models

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Over-reliance on fitness (resistance level) as the sole predictive variable. | Compare the nucleotide substitution pathways required for candidate mutations (e.g., transition vs. transversion). | Incorporate mutational bias and codon usage into stochastic, first-principle evolutionary models to better forecast which variants will arise in patient populations [15]. |

| Lack of tumor microenvironment in cell line models. | Validate findings from cell lines using patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models or clinical trial data. | Integrate spatial transcriptomic data from intact tissue sections to understand how the tissue context influences resistance evolution [31]. |

| Insufficient model complexity. | Test if a model parameterized on a large in vitro dataset can accurately predict epidemiological abundance in clinical trials. | Develop multi-scale models that are parameterized on large in vitro datasets and can bridge to clinical population outcomes [15]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol 1: Building a Deep Learning Model for Drug Response Prediction

This protocol outlines the methodology for constructing a model like "DrugS" to predict IC50 values from genomic features [30].

Data Acquisition and Curation:

- Input Features: Obtain gene expression data (e.g., for 20,000 protein-coding genes) and drug chemical data (e.g., SMILES strings) from public repositories like DepMap and GDSC.

- Output Variable: Collect corresponding half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values and apply a natural log transformation (LN IC50) to create the target variable for regression.

Data Preprocessing:

- Gene Expression: Log-transform and scale expression values to a uniform range to mitigate outlier influence.

- Drug Features: Convert SMILES strings into a numerical feature vector (e.g., 2048 dimensions) representing molecular structure.

- Data Filtering: Use clustering (e.g., TSNE) to identify and exclude outlier assay data with high variability within homogeneous cell line clusters.

Dimensionality Reduction:

- Employ an autoencoder to compress the high-dimensional gene expression data (e.g., from 20,000 to 30 features) to capture intrinsic structure.

Model Architecture and Training:

- Construct a Deep Neural Network (DNN) with an input layer that concatenates the reduced gene expression features and the drug fingerprint features.

- Include dropout layers in the network to prevent overfitting.

- Train the model using the concatenated features to predict the LN IC50 value.

Model Validation:

- Rigorously test the model's predictive performance on independent datasets (e.g., CTRPv2, NCI-60).

- Correlate predictions with drug response data from Patient-Derived Xenograft (PDX) models to assess clinical relevance.

Protocol 2: Utilizing Spatial Transcriptomics to Map Resistance Niches

This protocol describes how to apply spatial transcriptomics to identify localized drug resistance mechanisms in intact tumor tissue [31].

Tissue Preparation:

- Preserve fresh frozen or fixed-frozen (FF) tissue samples in Optimal Cutting Temperature (OCT) compound.

- Cryosection tissue at a recommended thickness (e.g., 10 µm) and mount onto specific gene expression slides compatible with the chosen platform (e.g., Visium from 10x Genomics).

Spatial Library Construction:

- Permeabilize the tissue section to allow mRNA release.

- Perform reverse transcription using barcoded primers that contain spatial coordinate information.

- Synthesize cDNA, then amplify and construct sequencing libraries following the manufacturer's instructions.

Sequencing and Data Generation:

- Sequence the libraries on a high-throughput platform (e.g., Illumina).

- Using the platform's software, align the sequence reads to a reference genome and assign them to specific spatial barcodes, generating a gene expression matrix mapped to tissue positions.

Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Pre-processing: Filter genes and spots, and normalize expression data.

- Integration: If possible, integrate the spatial data with existing scRNA-seq data to assist in cell type annotation.

- Spatial Analysis: Identify spatially variable genes and distinct transcriptional domains. Use specialized algorithms to infer cell-cell communication and interactions within the tumor microenvironment that may foster resistance.

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Diagram 1: Multi-scale Prediction of Resistance Epidemiology

Diagram 2: Spatial Transcriptomics Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| BaF3 Cells | A common murine pro-B cell line model used to express wild-type or mutant oncogenes (e.g., BCR-ABL) for in vitro drug sensitivity and resistance assays [15]. |

| 10x Genomics Visium | A commercial spatial transcriptomics platform that enables genome-wide mRNA expression profiling while retaining the two-dimensional spatial context of intact tissue sections [31]. |

| Cancer Cell Lines (DepMap) | A curated collection of hundreds of human cancer cell lines with extensive genomic and transcriptomic characterization, serving as a primary resource for in vitro drug screening and model development [30]. |

| Autoencoder (Computational) | A deep learning tool used for non-linear dimensionality reduction of high-dimensional genomic data (e.g., 20,000 genes), creating a lower-dimensional feature set that improves model robustness and cross-dataset compatibility [30]. |

| Nucleotide Substitution Bias Data | Information on the relative likelihood of different mutation types (e.g., transitions vs. transversions), which is a critical parameter for evolutionary models predicting the clinical frequency of specific resistance mutations [15]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is feature selection critical in genomic studies for drug resistance prediction?

Feature selection is essential because genomic data, such as transcriptomic profiles from RNA sequencing or DNA microarrays, is characteristically high-dimensional, often containing expression levels for thousands of genes from a relatively small number of samples [32]. This creates a high risk of overfitting, where a model learns noise instead of true biological signals. Feature selection mitigates this by identifying a minimal set of genes that are most predictive of the outcome, such as antibiotic resistance [33] [32]. This leads to models with higher accuracy, improved generalizability, faster training times, and better interpretability, which is crucial for understanding biological mechanisms and developing clinical diagnostics [34].

Q2: My model performs well on training data but poorly on validation sets. What feature selection issue might be the cause?

This is a classic sign of overfitting. It can occur if the feature selection process itself was not properly validated. If you perform feature selection on your entire dataset before splitting it into training and validation sets, information from the validation set "leaks" into the training process, making the model seem more accurate than it is [35]. To resolve this, always perform feature selection within each fold of cross-validation during the model training phase. This ensures that the feature set is selected based only on the training data, providing a realistic assessment of its performance on unseen data [35].

Q3: I found a minimal gene signature, but many genes are not known resistance markers. Does this invalidate the signature?

Not necessarily. In fact, this is a common and valuable finding. Many machine learning studies identify minimal gene signatures with high predictive accuracy that include a substantial number of genes not annotated in established resistance databases like the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD) [33]. For example, one study on Pseudomonas aeruginosa found that only 2-10% of the predictive genes overlapped with known CARD markers [33]. These "unknown" genes may be part of underexplored regulatory networks, metabolic pathways, or stress responses that contribute to the resistance phenotype. This discovery can reveal novel biological mechanisms and highlight gaps in current understanding [33].

Q4: How do I choose between Filter, Wrapper, and Embedded feature selection methods?

The choice depends on your specific goals, computational resources, and need for interpretability. The table below summarizes the core differences:

Table 1: Comparison of Feature Selection Method Types

| Method Type | Core Principle | Common Techniques | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Filter Methods [34] | Selects features based on statistical measures of correlation with the target variable. | Chi-square, Correlation, Mutual Information [36] [34]. | Fast, computationally efficient, and model-agnostic [34]. | Ignores feature interactions and the model context. |

| Wrapper Methods [34] | Uses the model's performance as the objective to evaluate different feature subsets. | Genetic Algorithms (GA), Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) [33] [34]. | Considers feature interactions; can yield high-performing subsets [33]. | Computationally expensive and has a higher risk of overfitting [34]. |

| Embedded Methods [34] | Performs feature selection as an integral part of the model training process. | LASSO regression, Ridge regression, and tree-based importance [37] [38] [34]. | Efficient balance of performance and computation; model-specific [34]. | Can be less interpretable than filter methods [34]. |

Q5: What are the best practices for validating a minimal gene signature's prognostic power?

To robustly validate a gene signature, follow these steps:

- Independent Validation: Test the signature's performance on one or more completely independent datasets that were not used during the signature's discovery or model training [38].

- Assess Incremental Value: Demonstrate that the gene signature provides prognostic information beyond established clinical and pathological factors. This can be done by showing a statistically significant improvement in model performance (e.g., using a likelihood ratio test) when the signature is added to a baseline model containing only clinical variables [39].

- Evaluate Clinical Utility: Determine if the signature's predictions are sufficient to change recommended treatment decisions and, ultimately, if its use improves patient outcomes in a prospective clinical trial [39].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol: Identification of a Prognostic Gene Signature using LASSO Cox Regression

This protocol is widely used in cancer prognosis research [38] and can be adapted for drug resistance studies.

1. Objective: To construct a minimal gene signature that predicts patient survival (or time-to-treatment-failure) from high-dimensional gene expression data.

2. Materials & Reagents:

- Dataset: A cohort of samples with gene expression data (e.g., from RNA-seq or microarrays) and corresponding survival data (overall survival, progression-free survival). Example: The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database [36] [38].

- Software: R or Python programming environment.

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Data Pre-processing. Normalize raw gene expression counts (e.g., using variance stabilizing transformation or Box-Cox normalization) to reduce technical batch effects [36].

- Step 2: Identify Potential Prognostic Genes. Perform a univariate analysis (e.g., univariate Cox regression) on all genes to identify those individually associated with survival (e.g., p-value < 0.05) [38].

- Step 3: Apply LASSO Cox Regression. Input the expression data of the potential prognostic genes from Step 2 into a LASSO (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator) Cox regression model. LASSO applies a penalty that shrinks the coefficients of less important genes to zero, effectively performing feature selection [38].

- Step 4: Determine the Optimal Penalty (Lambda). Use 10-fold cross-validation to find the value of lambda that minimizes the cross-validation error. The genes with non-zero coefficients at this optimal lambda constitute the final gene signature [38].

- Step 5: Calculate Risk Score. For each patient, calculate a risk score using the formula:

Risk Score = (Expression of Gene 1 * Coefficient 1) + (Expression of Gene 2 * Coefficient 2) + ...[38]. - Step 6: Validate the Signature. Divide patients into high-risk and low-risk groups based on the median risk score. Use Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and log-rank tests in both the training and independent validation cohorts to confirm that the groups have significantly different survival outcomes [38].

The workflow below illustrates this process.

Protocol: Building a Classifier with Genetic Algorithm-based Feature Selection

This protocol uses a wrapper method to find a minimal gene set for classifying resistant vs. susceptible isolates [33].

1. Objective: To identify a minimal set of ~35-40 genes that can accurately classify antibiotic resistance in bacterial pathogens using transcriptomic data.

2. Materials & Reagents:

- Dataset: Transcriptomic data (e.g., RNA-seq) from clinical isolates with confirmed resistant/susceptible phenotypes [33].

- Software: Python/R with ML libraries (e.g., scikit-learn) and optimization tools.

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Initialize Population. Generate a starting population of random gene subsets, each containing a fixed number of genes (e.g., 40) [33].

- Step 2: Evaluate Fitness. For each gene subset in the population, train a classifier (e.g., Support Vector Machine or Logistic Regression) and evaluate its performance using a metric like ROC-AUC or F1-score. This performance score is the subset's "fitness" [33].

- Step 3: Select, Cross Over, and Mutate.

- Select: Preferentially retain the gene subsets with the highest fitness scores.

- Cross Over: Create new "child" subsets by combining parts of two "parent" subsets.

- Mutate: Randomly introduce small changes (e.g., add or remove a gene) to some subsets to maintain diversity [33].

- Step 4: Iterate. Repeat Steps 2 and 3 for hundreds of generations. Over time, the population evolves toward subsets with higher fitness [33].

- Step 5: Form a Consensus. After many independent runs, rank all genes by how frequently they appeared in high-performing subsets. The top-ranked genes form a robust, consensus signature for the final classifier [33].

The workflow below illustrates the genetic algorithm cycle.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents & Computational Solutions

Table 2: Essential Tools for Feature Selection in Genomic Studies

| Tool / Reagent | Type | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| TCGA/ICGC Databases [36] [38] | Data Source | Public repositories providing large-scale genomic, transcriptomic, and clinical data for cancer research, often used as training and validation cohorts. |

| CARD (Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database) [33] | Data Source | A curated database of known antimicrobial resistance genes, used to benchmark and validate newly discovered gene signatures. |

R glmnet Package [38] |

Software Library | Widely used to perform LASSO, Ridge, and Elastic-Net regression for embedded feature selection. |

| Python scikit-learn [35] [34] | Software Library | Provides a comprehensive suite of tools for filter methods (SelectKBest), wrapper methods (RFE), and model training. |

| gSELECT Python Library [40] | Software Library | A specialized tool for evaluating the classification performance of pre-defined or automatically ranked gene sets prior to full analysis. |

| Genetic Algorithm (GA) [33] | Algorithm | An optimization technique used as a wrapper method to evolve high-performing, minimal gene subsets. |

| ABESS (Algorithm for Best-Subset Selection) [37] | Algorithm | A statistical method for selecting the best subset of features, shown to be effective in GWAS for drug resistance in M. tuberculosis. |

| mRMR (Min-Redundancy Max-Relevance) [36] | Algorithm | A filter method that selects features that are highly correlated with the target (relevance) but uncorrelated with each other (redundancy). |

The ultimate test of a minimal gene signature is its predictive performance. The table below summarizes key quantitative results from recent studies in different disease contexts.

Table 3: Performance Summary of Minimal Gene Signatures from Recent Studies

| Study Context (Organism) | Feature Selection Method | Signature Size | Key Performance Result | Validation Cohort |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antibiotic Resistance in P. aeruginosa [33] | Genetic Algorithm + AutoML | ~35-40 genes | 96% - 99% accuracy on test data | Hold-out test set from 414 isolates |

| Prognosis in Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma [36] | mRMR (Ensemble Method) | 13 genes | ROC AUC: 0.82 | ICGC-RECA (n=91) |

| Prognosis in Osteosarcoma [38] | LASSO Cox Regression | 17 genes | Significant stratification of high/low risk (Kaplan-Meier) | GEO: GSE21257 (n=53) |

| Drug Resistance in M. tuberculosis [37] | ABESS | N/A (Mutation sets) | Selected more relevant mutations vs. other methods | Cross-validation |

Accurately predicting drug resistance mutations is a critical challenge in modern therapeutic development, particularly in areas like oncology and infectious disease management. The selection of an appropriate machine learning algorithm significantly influences the predictive performance, interpretability, and clinical applicability of these models. This guide provides a structured comparison of three prominent algorithmic approaches—Logistic Regression, Random Forest, and Deep Learning—to assist researchers in selecting the optimal methodology for their specific drug resistance research.

Algorithm Comparison at a Glance

The table below summarizes the key characteristics, strengths, and limitations of each algorithm to guide your initial selection.

Table 1: Algorithm Comparison for Drug Resistance Prediction

| Algorithm | Best Use Cases | Key Strengths | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Logistic Regression (LR) | - Initial baseline models- High interpretability requirements- Scenarios with well-understood, additive variant effects [41] | - Highly interpretable; provides effect sizes (odds ratios) for mutations [41]- Efficient with smaller sample sizes- Less prone to overfitting with proper regularization | - Assumes linear, additive effects; cannot capture complex epistasis- Performance depends heavily on feature engineering |

| Random Forest (RF) | - Datasets with complex, non-linear interactions between mutations [42]- Multi-drug resistance prediction (using Multi-Label RF) [42] | - Robust performance on complex, non-linear data without intensive feature engineering [43]- Provides native feature importance rankings [42] | - Lower interpretability than LR ("black-box" nature)- Can be computationally intensive with very high-dimensional data |

| Deep Learning (DL) | - Very large datasets (>>10,000 samples) [44]- Whole-genome mutation analysis without pre-filtering [44]- Discovering novel, unknown resistance mechanisms | - Superior accuracy with sufficient data and tuning [44]- Capable of automatic feature representation from raw data | - Highest computational resource requirements- "Black-box" model with extreme interpretability challenges- High risk of overfitting on small datasets |

Experimental Protocols for Algorithm Implementation

Protocol for Multivariable Logistic Regression

Multivariable Logistic Regression extends univariate analysis by modeling the joint effect of multiple mutations on resistance.

- Data Preparation: Encode genetic variants as binary variables (0 = absent, 1 = present). Use a sparse matrix representation for efficiency with high-dimensional genetic data [41].

- Model Training: Train a single-drug model using a penalized regression approach (e.g., L1 or L2 regularization) to handle correlated features and prevent overfitting. The model estimates the probability of phenotypic resistance based on the presence of mutation combinations [41].

- Output Interpretation: Extract the odds ratio (OR) for each mutation. An OR > 1 indicates the mutation is associated with increased probability of resistance, conditional on the other mutations in the model [41].

Protocol for (Multi-Label) Random Forest

Random Forest is an ensemble method that can be adapted for single- or multi-drug resistance prediction.

- Feature Representation: Represent each isolate by a binary vector indicating the presence/absence of variants across candidate genes or the whole genome [42].

- Model Training:

- Single-Label RF (SLRF): Train one independent model for each drug's resistance profile [42].

- Multi-Label RF (MLRF): Train a single model that predicts resistance labels for all considered drugs simultaneously. This leverages correlations in resistance co-occurrence (e.g., MDR-TB) to improve predictive power [42].

- Feature Analysis: Use the built-in feature importance metric of the RF to rank mutations by their contribution to predicting resistance across all drugs [42].

Protocol for Deep Learning (MLP-Based Model)

Deep Learning models, such as Multi-Layer Perceptrons (MLPs), can learn complex mappings from genomic data to resistance phenotypes.

- Input Data Construction: Use variant calling on whole-genome sequencing data. The input is a high-dimensional binary vector representing mutations across the entire genome, avoiding reliance on a pre-defined set of known resistance loci [44].

- Model Architecture & Training: Implement an MLP architecture within a modular framework (e.g., TensorFlow). The model typically consists of multiple fully connected (dense) layers with non-linear activation functions [44].