Advancing Anticancer Drug Discovery: A Comprehensive Guide to PLK1 Inhibitor Development Using 3D-QSAR Models

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals exploring Polo-like kinase 1 (PLK1) inhibitors through 3D-QSAR modeling.

Advancing Anticancer Drug Discovery: A Comprehensive Guide to PLK1 Inhibitor Development Using 3D-QSAR Models

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals exploring Polo-like kinase 1 (PLK1) inhibitors through 3D-QSAR modeling. It covers the foundational role of PLK1 as a validated anticancer target and systematic application of computational techniques including Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA), Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA), molecular docking, and dynamics simulations. The content addresses critical methodological considerations for model development, optimization strategies to enhance predictive power and selectivity, and robust validation protocols integrating both computational and experimental approaches. By synthesizing recent advances in the field, this guide aims to bridge computational predictions with experimental reality, supporting the rational design of novel, potent, and selective PLK1 inhibitors for cancer therapy.

PLK1 as a Therapeutic Target: Biological Rationale and SAR Fundamentals

The Oncogenic Role of PLK1 in Cell Cycle Regulation and Cancer Progression

Polo-like kinase 1 (PLK1) is a serine/threonine kinase that functions as a critical regulator of mitosis and is overexpressed in a wide range of human cancers, where it often correlates with poor clinical prognosis [1] [2]. As a key mitotic regulator, PLK1 coordinates multiple cell cycle events including centrosome maturation, spindle assembly, kinetochore-microtubule attachment, and cytokinesis [1] [3]. The unique structural characteristics of PLK1, featuring an N-terminal kinase domain and a C-terminal polo-box domain (PBD), make it an attractive target for anti-cancer drug development [1] [3]. Recent advances in computational approaches, particularly 3D-QSAR modeling, are providing new pathways for developing selective PLK1 inhibitors with improved efficacy and reduced toxicity [4]. This review examines the oncogenic functions of PLK1, its roles in cancer progression, and the current landscape of inhibitor development within the context of structure-based drug design.

Structural Biology of PLK1

Domain Architecture and Regulation

PLK1 is a 603-amino acid protein with a molecular mass of approximately 66 kDa, organized into two primary functional domains connected by an inter-domain linker [1] [3]. The N-terminal kinase domain (KD) (residues 49-310) contains all elements necessary for catalytic activity, including the critical Thr210 residue within the activation loop (T-loop) whose phosphorylation is essential for full kinase activity [1] [3]. The C-terminal polo-box domain (PBD) (residues 345-603) consists of two polo-box motifs (PB1 and PB2) that form a phosphopeptide-binding site responsible for subcellular localization and substrate recognition [1] [3].

PLK1 activity is tightly regulated through a sophisticated autoinhibitory mechanism where the PBD interacts with the KD to maintain a closed, inactive conformation during interphase [3]. Activation involves multiple steps including phosphorylation at Thr210 by upstream kinases (primarily Aurora A in complex with Bora), binding of phosphorylated substrates to the PBD, and disruption of the KD-PBD interaction, resulting in an open, active conformation [3]. Recent research has also identified that PLK1 can form different oligomeric states, including homodimers and heterodimers with PLK2, which likely play context-dependent regulatory roles during the cell cycle [3].

Structural Determinants for Drug Targeting

The kinase domain contains a deep ATP-binding pocket located at the interface between the N-lobe (predominantly β-sheets) and C-lobe (α-helices) [1]. Key residues defining this pocket include Lys82 (involved in ATP anchoring), Glu131 and Asp194 (catalytic network residues), and Cys133 and Phe58 (influencing pocket topology and inhibitor selectivity) [1]. The hinge region connecting the two lobes provides hydrogen bond donors and acceptors that interact with the adenine moiety of ATP, and these same sites are exploited by ATP-competitive inhibitors [1].

The polo-box domain offers an alternative targeting strategy with potentially greater selectivity [1] [3]. The PBD recognizes substrates through a consensus phosphopeptide motif and contains two primary binding subsites: the Ser-pThr binding interface (with key residues His538 and Lys540 engaging phosphothreonine) and a hydrophobic cryptic pocket that only becomes accessible in ligand-bound states [3]. Targeting the PBD represents a promising approach to disrupt PLK1's subcellular localization and substrate interactions without directly competing with ATP binding [1].

Table 1: Key Structural Domains of PLK1 and Their Functional Characteristics

| Domain | Residue Range | Key Structural Features | Functional Role | Key Regulatory Residues |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kinase Domain (KD) | 49-310 | N-lobe (β-sheets), C-lobe (α-helices), hinge region | Catalytic activity, ATP binding, substrate phosphorylation | Thr210 (activation loop), Lys82 (ATP anchoring), Glu131, Asp194 (catalytic machinery) |

| Polo-Box Domain (PBD) | 345-603 | Two polo-box motifs (PB1, PB2) forming β-sandwich | Substrate recognition, subcellular localization | His538, Lys540 (phosphopeptide binding), Trp414 (Ser-pThr-1 specificity) |

| Inter-Domain Linker (IDL) | 311-344 | Flexible connector | Mediates KD-PBD interactions | - |

Diagram 1: Structural domains and regulatory interactions of PLK1. The autoinhibitory interaction between the kinase domain and polo-box domain maintains PLK1 in a closed, inactive state during interphase.

Oncogenic Mechanisms of PLK1 in Cancer Progression

Cell Cycle Dysregulation and Mitotic Progression

PLK1 exerts master regulatory control over multiple aspects of cell division, with its expression peaking during G2/M phase [2] [3]. In cancer cells, PLK1 overexpression disrupts normal cell cycle checkpoints, leading to genomic instability and uncontrolled proliferation. Key mitotic functions under PLK1 regulation include:

- Centrosome Maturation: PLK1 promotes recruitment of the γ-tubulin ring complex (γ-TuRC) to centrosomes and phosphorylates key proteins including Nek9 and Eg5 to facilitate bipolar spindle formation [2].

- Spindle Assembly Checkpoint: PLK1 recruits PP2A to BubR1, enabling proper kinetochore-microtubule attachment and chromosome alignment [2] [3].

- Metaphase-to-Anaphase Transition: PLK1 is ubiquitinated by the APC/C complex upon proper chromosome attachment, facilitating mitotic exit [2].

- Cytokinesis: PLK1 regulates PRC1 and CEP55 to mediate cytoplasmic division and abscission [2].

Metabolic Reprogramming

Recent research has uncovered non-canonical functions of PLK1 in cancer metabolism, particularly through regulation of metabolic pathways that support rapid proliferation:

- Pentose Phosphate Pathway Activation: PLK1 promotes the formation of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) active dimers through direct phosphorylation, activating the pentose phosphate pathway to generate nucleotides and NADPH for biosynthetic processes [2].

- Aerobic Glycolysis: PLK1 activates the PI3K/AKT pathway, which enhances aerobic glycolysis (Warburg effect) in cancer cells [2].

- Oxidative Stress Management: PLK1-mediated metabolic reprogramming helps maintain lower intracellular ROS levels, increasing capacity to counteract oxidative stress and supporting metastasis [5].

Promotion of Metastasis and Therapeutic Resistance

PLK1 drives cancer aggressiveness through multiple mechanisms that enhance metastatic potential and confer treatment resistance:

- Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition: PLK1 is a key regulator of EMT in various cancers. In non-small cell lung cancer, PLK1 promotes invasion and metastasis by activating β-catenin/AP-1 signaling and TGF-β pathways [2]. Similar PLK1-mediated EMT regulation occurs in gastric cancer and osteosarcoma through AKT pathway modulation [2].

- Transcription Factor Stabilization: PLK1 stabilizes the transcription factor BACH1, which drives expression of genes involved in cancer metabolism and metastasis [5]. This PLK1/BACH1 axis also confers resistance to Vemurafenib in BRAF-mutant melanoma [5].

- Oncoprotein Regulation: PLK1 enhances stability of the MYC oncoprotein by phosphoryting FBW7, preventing its autoubiquitination and degradation, thereby promoting MYC-driven proliferation [2].

- Immune Evasion: Emerging evidence indicates PLK1 regulates immune checkpoint-related proteins and influences the tumor microenvironment, enabling immune evasion [2] [6].

Table 2: Key Oncogenic Signaling Pathways Regulated by PLK1

| Pathway | Molecular Mechanism | Oncogenic Outcome | Cancer Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| PI3K/AKT | Phosphorylation and inactivation of PTEN | Enhanced cell survival, aerobic glycolysis | Multiple cancers [2] |

| MYC Signaling | Phosphorylation of FBW7, preventing MYC degradation | Increased proliferation, apoptosis evasion | Various tumors [2] |

| BACH1 Regulation | Stabilization of BACH1 transcription factor | Metabolic reprogramming, metastasis | Melanoma [5] |

| β-catenin/AP-1 | Activation of Wnt/β-catenin and AP-1 signaling | EMT, invasion, metastasis | NSCLC [2] |

| TGF-β Pathway | Regulation of TGF-β signaling axis | EMT, cell motility | NSCLC, other cancers [2] |

| p53 Signaling | Regulation of p53 activity | Cell cycle arrest evasion, genomic instability | Multiple cancers [2] |

Diagram 2: Oncogenic pathways and processes driven by PLK1 overexpression in cancer. PLK1 coordinates multiple signaling networks that promote tumor progression through cell cycle dysregulation, metabolic reprogramming, metastasis, and therapeutic resistance.

PLK1 Inhibitors: Development and Therapeutic Applications

ATP-Competitive Inhibitors

Most clinical-stage PLK1 inhibitors target the ATP-binding pocket within the kinase domain and effectively induce mitotic arrest and apoptosis in tumor cells [1]. Key representatives include:

- Volasertib (BI6727): A highly potent dihydropteridinone inhibitor that demonstrates strong anti-tumor activity across various cancer models. It has shown promise in combination with BRAF inhibitors for melanoma treatment [5] [1].

- Onvansertib (NMS-P937): A selective inhibitor with >5,000-fold selectivity for PLK1 over PLK2 and PLK3, currently in clinical trials for KRAS-mutant metastatic colorectal cancer in combination with FOLFIRI/bevacizumab [7].

- BI2536: One of the first potent PLK1 inhibitors tested clinically, shown to decrease proliferation, migration, and invasion in synovial sarcoma models while promoting apoptosis and G2/M cell cycle arrest [8].

Polo-Box Domain Inhibitors

The PBD represents an alternative targeting strategy with potential for greater selectivity, as this domain is structurally unique to polo-like kinases [1] [3]. PBD inhibitors disrupt protein-protein interactions critical for PLK1's subcellular localization and substrate recognition, rather than competing with ATP binding [1]. While these compounds often display lower initial potency compared to ATP-competitive inhibitors, they offer enhanced specificity and potentially reduced off-target effects [1].

Deuterated PLK1 Inhibitors

Recent innovations include deuterium-modified compounds designed to improve pharmacokinetic profiles. PR00012, a deuterated version of Onvansertib with hydrogen atoms replaced by deuterium on the piperazine ring, demonstrates enhanced metabolic stability and improved safety profile while maintaining efficacy [7]. In preclinical studies, PR00012 showed reduced toxicity and better tolerability across multiple mouse models, with no rat deaths in 14-day toxicity studies compared to one-third mortality with non-deuterated NMS-P937 [7].

Combination Therapies and Clinical Applications

PLK1 inhibitors show particular promise in combination therapies that address resistance mechanisms and enhance efficacy:

- Targeted Therapy Combinations: PLK1 inhibition synergizes with BRAF inhibitors in melanoma, overcoming Vemurafenib resistance through disruption of the PLK1/BACH1 axis [5].

- Chemotherapy Combinations: In KRAS-mutant colorectal cancer, Onvansertib combined with FOLFIRI/bevacizumab shows manageable safety and promising efficacy as second-line treatment [9] [7].

- Immunotherapy Integration: PLK1 regulates immune checkpoint proteins and influences the tumor microenvironment, suggesting potential for combination with immunotherapy agents [2] [6].

Table 3: Representative PLK1 Inhibitors in Development and Their Properties

| Inhibitor | Target Site | Key Characteristics | Clinical Status | Cancer Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Volasertib (BI6727) | ATP-binding pocket | Potent dihydropteridinone inhibitor | Phase II trials | AML, melanoma (with BRAF inhibitors) [5] [1] |

| Onvansertib (NMS-P937) | ATP-binding pocket | High selectivity (>5000-fold PLK1 vs PLK2/3) | Phase Ib/II trials | KRAS-mutant mCRC, AML [7] |

| BI2536 | ATP-binding pocket | Early potent inhibitor | Phase II trials | NSCLC, synovial sarcoma [8] |

| PR00012 | ATP-binding pocket | Deuterated Onvansertib with improved safety | Preclinical | Various cancers (preclinical) [7] |

| PBD-targeting compounds | Polo-box domain | Disrupts subcellular localization | Research phase | Experimental models [1] [3] |

3D-QSAR Modeling in PLK1 Inhibitor Development

Fundamental Principles and Methodologies

Three-dimensional Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (3D-QSAR) modeling represents a sophisticated computational approach that correlates the three-dimensional molecular properties of compounds with their biological activities, enabling predictive design of novel inhibitors [4]. For PLK1 inhibitor development, key methodologies include:

- Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA): Evaluates steric and electrostatic fields around aligned molecules to generate contour maps identifying regions where specific molecular properties enhance or diminish activity [4].

- Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA): Extends beyond CoMFA by incorporating additional fields including hydrophobic, hydrogen bond donor, and acceptor properties, providing more comprehensive molecular interaction information [4].

- Statistical Validation: Robust models require both internal validation (cross-validated correlation coefficient Q² > 0.5) and external validation (predictive correlation coefficient R²ₚᵣₑ𝒹 > 0.6) to ensure predictive capability [4].

Application to Pteridinone Derivatives as PLK1 Inhibitors

Recent 3D-QSAR studies on pteridinone derivatives have demonstrated the power of this approach in PLK1 inhibitor optimization [4]. The established models showed excellent predictive capability, with CoMFA (Q² = 0.67, R² = 0.992), CoMSIA/SHE (Q² = 0.69, R² = 0.974), and CoMSIA/SEAH (Q² = 0.66, R² = 0.975) models all demonstrating strong statistical significance [4]. Molecular docking revealed that key residues R136, R57, Y133, L69, L82, and Y139 constitute critical interaction sites within the PLK1 ATP-binding pocket (PDB: 2RKU) [4].

Integration with Molecular Dynamics and ADMET Profiling

Advanced 3D-QSAR workflows incorporate molecular dynamics simulations to validate docking results and assess ligand-protein complex stability over time (typically 50 ns simulations) [4]. Additionally, absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) profiling provides critical data on drug-like properties, enabling prioritization of candidates with optimal efficacy and safety profiles [4]. These integrated computational approaches significantly accelerate the drug discovery pipeline while reducing development costs.

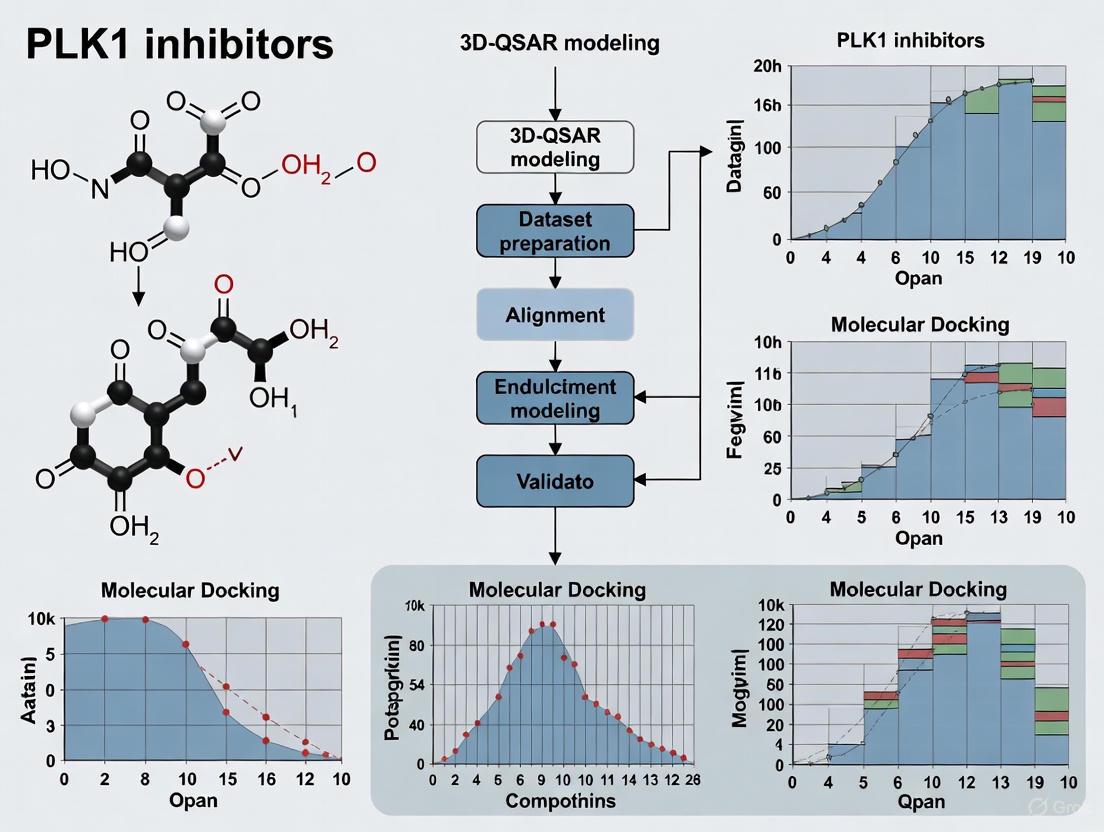

Diagram 3: Integrated computational workflow for PLK1 inhibitor development using 3D-QSAR modeling, molecular docking, dynamics simulations, and ADMET profiling. This approach enables rational design of inhibitors with optimized potency and drug-like properties.

Experimental Protocols for PLK1 Research

Kinase Inhibition Assays

Purpose: To evaluate the inhibitory potency and selectivity of PLK1 compounds.

HTRF Assay Protocol:

- Prepare compound dilutions in DMSO using serial dilution (3- or 5-fold gradients from 10 μM starting concentration) [7].

- Transfer 50 nL of each diluted compound to 384-well detection plates using acoustic dispensing (Echo 655) [7].

- Add 2.5 μL of 2× kinase solution (in reaction buffer) to each well and incubate at 25°C for 10 minutes [7].

- Add 2.5 μL of 2× ATP/substrate solution to initiate reaction and incubate at 25°C for 40 minutes [7].

- Add 5 μL of detection reagent containing XL665 and antibody in detection buffer, incubate 1 hour at 25°C [7].

- Measure fluorescence signals at 620 nm (Cryptate) and 665 nm (XL665) using a plate reader [7].

ADP-Glo Assay Protocol:

- Transfer 40 nL of diluted compounds to 384-well plates via acoustic dispensing [7].

- Add 2 μL of 2× kinase solution, incubate 10 minutes at 25°C [7].

- Add 2 μL of 2× ATP/substrate solution, incubate 60 minutes at 25°C [7].

- Add 4 μL of ADP-Glo reagent, incubate 40 minutes at 25°C [7].

- Add 8 μL of detection solution, incubate 40 minutes at 25°C [7].

- Measure luminescence signals using a plate reader [7].

Cellular Proliferation and Viability Assays

Purpose: To assess anti-proliferative effects of PLK1 inhibitors in cancer cell lines.

CellTiter-Glo Protocol:

- Seed cells in 96-well plates at 2,000-6,000 cells/well in logarithmic growth phase [7].

- Following overnight incubation, add test compounds at various concentrations [7].

- Incubate for 72 hours at 37°C in 5% CO₂ [7].

- Add CellTiter-Glo reagent to measure ATP concentration as viability indicator [7].

- Record luminescence values using a multilabel reader [7].

Molecular Docking and 3D-QSAR Analysis

Purpose: To predict binding modes and develop quantitative activity relationship models.

Molecular Docking Protocol:

- Prepare protein structure (PLK1 PDB: 2RKU) by removing water molecules and adding hydrogens [4].

- Generate ligand structures and optimize geometry using Tripos force field with Gasteiger-Hückel charges [4].

- Define binding site based on known active site residues (R136, R57, Y133, L69, L82, Y139) [4].

- Perform docking simulations using AutoDock Vina or similar software [4].

- Analyze binding poses and interaction patterns for most active compounds [4].

3D-QSAR Model Development:

- Align molecules using rigid body alignment in SYBYL-X 2.1 software [4].

- Calculate CoMFA and CoMSIA descriptors using grid spacing of 1Å extending 4Å in all coordinates [4].

- Perform Partial Least Squares (PLS) analysis to correlate field values with biological activities [4].

- Validate models using leave-one-out (LOO) cross-validation and external test sets [4].

- Generate contour maps to visualize regions favoring/disadvantaging biological activity [4].

In Vivo Efficacy and Toxicity Evaluation

Purpose: To assess therapeutic potential and safety profile of PLK1 inhibitors in animal models.

Xenograft Tumor Model Protocol:

- Implant cancer cells subcutaneously in immunocompromised mice (M-NSG, BALB/c nude, or NOD SCID) [7].

- Randomize animals into treatment groups when tumors reach 100-200 mm³ [7].

- Administer compounds via appropriate route (oral gavage or intraperitoneal injection) [7].

- Monitor tumor dimensions 2-3 times weekly using calipers, calculate volume as (length × width²)/2 [7].

- Assess toxicity through body weight monitoring, clinical observations, and survival tracking [7].

- Terminate study at predetermined endpoint or when tumor burden exceeds ethical limits [7].

- Process tumors for immunohistochemical analysis of biomarkers (e.g., phosphorylated TCTP) [7].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for PLK1 Investigations

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Application & Function | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| PLK1 Inhibitors | BI2536, Volasertib, Onvansertib | Chemical inhibition of PLK1 kinase activity; mechanism studies | In vitro and in vivo functional studies [8] [7] |

| Cell Lines | PSN1, PANC-1, MIA PaCa-2, SW982, SYT-SSX1 | Disease models for evaluating PLK1 inhibition | Cellular proliferation, migration, invasion assays [8] [7] |

| Antibodies | PLK1, phospho-TCTP, Bax, cleaved caspase-3 | Detection of protein expression and activation states | Western blot, immunohistochemistry [8] [7] |

| Kinase Assay Systems | HTRF Kinase Kit, ADP-Glo Assay | Direct measurement of kinase inhibition | Biochemical kinase activity screening [7] |

| Cell Viability Assays | CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Assay | Quantification of cell proliferation and viability | High-throughput compound screening [7] |

| Animal Models | M-NSG, BALB/c nude, NOD SCID mice | In vivo evaluation of efficacy and toxicity | Xenograft tumor studies [7] |

| Computational Tools | SYBYL-X 2.1, AutoDock Tools, Molecular Dynamics | 3D-QSAR, docking, and simulation studies | Structure-based drug design [4] |

PLK1 represents a master regulator of oncogenic processes that extends far beyond its canonical mitotic functions to include metabolic reprogramming, metastasis promotion, and therapy resistance. The structural characterization of both kinase and polo-box domains has enabled targeted inhibitor development, while 3D-QSAR approaches provide powerful computational tools for optimizing compound selectivity and efficacy. Current research directions include developing domain-specific inhibitors, exploring combination therapy strategies, and engineering deuterated compounds with improved safety profiles. As our understanding of PLK1's diverse oncogenic functions continues to expand, so too will opportunities for therapeutic intervention across multiple cancer types. The integration of structural biology, computational modeling, and mechanistic studies will continue to drive innovation in PLK1-targeted cancer therapeutics.

Polo-like Kinase 1 (PLK1) is a crucial serine/threonine kinase that functions as a master regulator of cell division, controlling multiple aspects of mitotic progression including centrosome maturation, spindle assembly, kinetochore-microtubule attachment, and cytokinesis [1] [10]. As a highly validated oncology target, PLK1 is overexpressed in various human tumors, and its expression often correlates with poor prognosis [1] [9]. The unique domain architecture of PLK1, consisting of an N-terminal kinase domain and a C-terminal polo-box domain, provides a structural framework for its regulation and function. This architectural complexity also presents unique opportunities for targeted therapeutic intervention, particularly through computational approaches such as 3D quantitative structure-activity relationship (3D-QSAR) modeling [11]. Within the context of drug discovery, understanding the structural biology of PLK1 is fundamental for developing selective inhibitors that can exploit both traditional ATP-binding sites and alternative regulatory domains.

PLK1 is composed of 603 amino acids with an approximate molecular mass of 66 kDa [1]. Its polypeptide sequence is organized into two primary functional domains connected by an inter-domain linker (IDL): the N-terminal kinase domain (KD) and the C-terminal polo-box domain (PBD) [12]. This dual-domain architecture is characteristic of the polo-like kinase family, with the kinase domain providing catalytic function and the polo-box domain serving regulatory purposes.

Table 1: Domain Architecture of Human PLK1

| Domain | Residue Range | Primary Function | Key Structural Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kinase Domain (KD) | 49-310 [1] | Catalytic phosphorylation of substrates | Conserved kinase fold; ATP-binding pocket; T-loop with Thr210 |

| Inter-Domain Linker (IDL) | 311-366 [12] | Connects KD and PBD | Flexible region allowing domain-domain interactions |

| Polo-Box Domain (PBD) | 367-603 [12] | Substrate recognition and subcellular localization | Two polo-box motifs (PB1, PB2) forming β-sandwich |

| Polo-Cap | Precedes PB1 [12] | Structural organization | α-helical segment connecting IDL to PB1 |

The inter-domain communication between the KD and PBD is critical for PLK1 regulation. In its basal state, PLK1 exists in an autoinhibited conformation where the PBD interacts with the KD to suppress catalytic activity [12]. Activation involves relief of this autoinhibition through phosphorylation events and binding to priming phosphorylation sites on substrates.

Figure 1: Domain Architecture of PLK1. The kinase domain (residues 49-310) is connected via an inter-domain linker to the polo-box domain (residues 367-603), which contains two polo-box motifs and a polo-cap region that mediate substrate recognition and autoinhibition.

Structural Organization of the Kinase Domain

The N-terminal kinase domain of PLK1 (residues 49-310) contains all the essential elements required for catalytic activity [1]. This domain adopts a typical kinase fold that combines β-sheets and α-helices, forming an incomplete β-barrel composed of six antiparallel strands and several α-helix bundles at the C-terminal region that provide structural stability [1]. The catalytic site, where phosphorylation of serine/threonine residues on substrates occurs, is located at the interface between the N-lobe (predominantly β-sheets) and the C-lobe (rich in α-helices) [1].

A critical regulatory element within the kinase domain is the activation loop (T-loop), which contains Thr210. Phosphorylation of Thr210 is an essential post-translational modification required for PLK1 to achieve full catalytic activity [1]. This phosphorylation event is primarily catalyzed by Aurora A kinase in association with its cofactor Bora [1]. The incorporation of a phosphate group at Thr210 induces a conformational change that stabilizes the active structure of PLK1, opening the catalytic cleft and enabling the kinase to recognize and phosphorylate its physiological substrates.

ATP-Binding Pocket and Key Residues

The ATP-binding pocket is a narrow cavity located at the interface between the N-lobe and C-lobe that recognizes both the adenine base and the ribose-phosphate backbone of ATP [1]. The architecture of this pocket is defined by a set of highly conserved residues that determine ATP affinity and kinase selectivity.

Table 2: Key Residues in the PLK1 Kinase Domain ATP-Binding Pocket

| Residue | Location | Functional Role | Significance for Inhibitor Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lys82 | N-lobe | ATP anchoring and orientation | Forms salt bridge with ATP α- and β-phosphates |

| Phe58 | Hinge region | Hydrophobic interactions | Contributes to selectivity sub-pocket |

| Cys133 | Catalytic loop | Shapes pocket geometry | Cysteine residue exploited for selective inhibition |

| Glu131 | Catalytic loop | Catalytic network | Positions substrates for phosphorylation |

| Asp194 | Catalytic loop | Catalytic base | Essential for phosphotransfer reaction |

| Thr210 | Activation loop | Phosphoregulation | Phosphorylation activates kinase |

The hinge region, which connects the N-lobe and C-lobe, provides donor and acceptor atoms that form hydrogen bonds with the adenine moiety of ATP. These same interaction sites are exploited by ATP-competitive inhibitors, which are designed to mimic these natural hydrogen bonding patterns [1]. Nearby residues, including Phe58 and the gatekeeper residue, contribute hydrophobic contacts that define the selectivity sub-pocket, creating opportunities for developing specific PLK1 inhibitors with reduced off-target effects against other kinases.

Co-crystallization studies with representative ATP-competitive inhibitors (BI-2536, volasertib, onvansertib, GSK461364) reveal a recurring binding pattern: these inhibitors typically form between one and three hydrogen bonds with the hinge region, while aromatic or hydrophobic fragments occupy adjacent hydrophobic pockets to enhance binding affinity and inhibitory potency [1]. Subtle variations in residue conformations, such as different rotamers of Cys133 or the positioning of Phe58, account for differences in selectivity between PLK1 and other polo-like kinase family members (PLK2 and PLK3) [1].

Structural Organization of the Polo-Box Domain

The polo-box domain (PBD) located in the C-terminal region of PLK1 (residues 345-603) constitutes a distinctive structural feature of the PLK family and is responsible for substrate recognition and subcellular localization [12] [1]. The PBD is composed of two structurally similar but sequentially distinct polo-box motifs (PB1 and PB2) that pack together to form a single functional unit [12]. Despite only 12% sequence identity between them, PB1 and PB2 adopt nearly identical folds, each consisting of a six-stranded antiparallel β-sheet and an α-helix [12] [13]. Together, they form a 12-stranded β sandwich flanked by three α-helical segments [12].

The structured region of the PBD is preceded by the polo-cap, a structural element at the end of the sequence connecting the kinase domain with the PBD [12]. The polo-cap consists of an α-helical segment, loop, and 3₁₀ helix motif that connects to the first strand of PB1 through a short linker region designated L1. The two polo boxes are connected by another partially conserved 30-residue linker, L2, which runs antiparallel to L1 and contributes to the hydrophobic core formed by conserved residues from the β-strands of both polo-boxes [12].

The PBD recognizes phosphorylated substrates through a conserved binding groove that interacts with a specific consensus motif. The optimized phosphopeptide recognition sequence (known as PoloBoxTide) is MAGPMQ-S-pT-P-LNGAKK, which contains a phosphorylated threonine residue (pThr) that serves as the primary recognition element [12]. Structural studies have revealed that this phosphopeptide binds along a shallow, positively charged groove formed at the interface where the two polo box motifs interact, separated by the L2 linker [12].

Key Binding Interactions and Cryptic Pockets

The molecular recognition of phosphopeptides by the PLK1 PBD involves specific interactions with both the phosphate moiety and adjacent residues. The phosphothreonine side chain forms critical ion pairing interactions with His538 and Lys540, with additional stabilization provided by an extensive network of bridging structural water molecules [12]. The essential nature of these interactions has been confirmed by site-directed mutagenesis, where His538Ala and Lys540Met mutations nearly completely abolish peptide binding to the PBD [12].

The PBD exhibits exquisite selectivity for serine at the pThr-1 position (immediately N-terminal to the phosphorylated threonine), which results from engagement of this residue with Trp414 and Leu491 through main chain hydrogen bonding interactions [12]. The strict conservation of Trp414 explains the serine preference at this position, and the Trp414Phe mutation eliminates both phosphopeptide binding and centrosomal localization of PLK1 [12]. In contrast, the selection for proline at the pThr+1 position is more modest, with multiple substitutions tolerated at this position, likely due to limited stabilizing interactions in the peptide-PBD interface [12].

Beyond the primary phosphopeptide binding groove, the PBD contains a cryptic hydrophobic pocket (CP) that exists as a "cryptic pocket" only in substrate or ligand-bound forms of the PBD [12]. This Tyr-lined hydrophobic pocket, composed of residues V415, Y417, Y421, L478, Y481, F482, and Y485, is located adjacent to the phosphosubstrate binding groove and plays a critical role in substrate discrimination [14]. The Tyr pocket can adopt open or closed conformations and contributes to the recognition of specific PLK1 substrates that contain complementary hydrophobic residues [14].

Figure 2: Phosphopeptide Recognition by PLK1 PBD. The PBD recognizes substrates through multiple binding subsites: the primary phosphothreonine binding site (His538/Lys540), the Ser(-1) binding pocket (Trp414/Leu491), and the cryptic Tyr pocket that engages hydrophobic residues on specific substrates.

Regulatory Mechanisms and Domain Cooperation

Autoinhibition and Activation

PLK1 activity is tightly regulated through an autoinhibitory mechanism involving domain-domain interactions between the KD and PBD [12]. In the basal state, these inter-domain interactions maintain PLK1 in a closed, autoinhibited conformation where the PBD suppresses catalytic activity. Activation of PLK1 requires relief of this autoinhibition through several mechanisms, including phosphorylation at Thr210 within the activation loop of the kinase domain and binding of the PBD to primed phosphorylation sites on substrates or regulatory proteins [12] [1].

The interaction between PLK1 and its cofactor Bora represents a key activation mechanism. This interaction, along with phosphosubstrate binding and T210 phosphorylation, can induce an open and active conformation where the domain-domain inhibitory interactions no longer dominate [12]. Recent studies have also revealed that PLK1 can undergo interchange between monomeric and dimeric forms, which may serve as additional regulatory mechanisms to inhibit or activate PLK1 during specific phases of the cell cycle [12]. Different oligomeric forms of PLK1, including homodimers and heterodimers with PLK2, have been identified and likely play context-dependent roles in regulating PLK1 function [12].

Substrate Priming Mechanisms

The PBD-dependent interaction with phosphorylated targets occurs through two distinct biochemical mechanisms: self-priming and non-self-priming [10]. In the self-priming mechanism, PLK1 itself catalyzes the priming phosphorylation that creates its own PBD-binding site on certain substrates [10]. A well-characterized example of this mechanism involves the kinetochore protein PBIP1, where PLK1 phosphorylates PBIP1 at Thr78 and then binds to the resulting pT78 motif through its PBD, thereby recruiting itself to kinetochores [10]. This self-priming and binding creates a positive feedback loop that amplifies PLK1 localization and activity at specific subcellular structures.

In the non-self-priming mechanism, the priming phosphorylation is catalyzed by kinases other than PLK1, typically proline-directed kinases such as CDK1 [10]. For example, CDK1 phosphorylates the S796 residue of the centrosomal protein hCenexin1, creating a binding site for PLK1 PBD that recruits PLK1 to centrosomes during mitosis [10]. This mechanism allows PLK1 to integrate signals from other cell cycle kinases and coordinate its activities with different phases of mitotic progression.

Experimental Approaches for PLK1 Structural Biology

Structural Determination Methods

The structural biology of PLK1 domains has been primarily elucidated through X-ray crystallography. The PBD was the first domain to be solved crystallographically through complexes with phosphopeptides [12] [13]. Initial crystallization efforts utilized limited proteolysis to identify a stable structured region encompassing residues 367-603, which was subsequently expressed and crystallized [13]. The crystal structure of the PLK1 PBD in complex with a consensus phosphothreonine-containing peptide was determined at 2.2-2.3 Å resolution, revealing the detailed molecular interactions involved in phosphopeptide recognition [13].

For the kinase domain, structural studies have often involved co-crystallization with ATP-competitive inhibitors to stabilize the domain and facilitate crystallization [1]. These studies have revealed the detailed architecture of the ATP-binding pocket and the conformational changes associated with Thr210 phosphorylation and kinase activation [1]. The complete structure of full-length PLK1 remains challenging to determine due to the flexibility of the inter-domain linker, but recent advances in cryo-electron microscopy may provide new opportunities for visualizing the autoinhibited full-length structure.

Binding Assays and Functional Characterization

Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) and microscale thermophoresis (MST) are widely used to quantitatively characterize the binding affinity of PLK1 interactions with substrates and inhibitors. For example, recent studies discovering peptide inhibitors targeting the PBD used MST assays to confirm strong binding affinity, with one optimized peptide (PL-1) exhibiting a Kd of 3.11 ± 0.05 nM [15]. Kinase selectivity assays are essential for confirming the specificity of PLK1 inhibitors, typically performed against panels of related kinases to identify potential off-target effects [15].

Cellular characterization of PLK1 localization and function often involves immunofluorescence microscopy using specific antibodies against PLK1 and various mitotic markers. These studies have demonstrated that mutations affecting the phosphopeptide-binding groove (H538A/K540M) or the cryptic Tyr pocket (Y421A/L478A/Y481D) disrupt proper localization of PLK1 to kinetochores while preserving centrosomal localization, indicating distinct binding requirements for different subcellular structures [14].

Table 3: Key Experimental Methods in PLK1 Structural Biology

| Method | Application | Key Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| X-ray Crystallography | Determine high-resolution structures of KD and PBD | Revealed atomic details of ATP-binding pocket and phosphopeptide recognition |

| Microscale Thermophoresis (MST) | Quantify binding affinity of inhibitors | Measured Kd values in nanomolar range for optimized inhibitors [15] |

| Site-directed Mutagenesis | Validate functional residues | Confirmed essential role of His538, Lys540 in phosphopeptide binding [12] |

| Immunofluorescence Microscopy | Cellular localization studies | Showed distinct localization requirements for kinetochores vs centrosomes [14] |

| Molecular Dynamics Simulations | Study conformational flexibility and binding stability | Demonstrated structural stability of inhibitor complexes [15] |

Computational Approaches for PLK1 Inhibitor Design

3D-QSAR Modeling

Three-dimensional quantitative structure-activity relationship (3D-QSAR) studies have emerged as powerful computational tools for understanding the structural basis of PLK1 inhibition and guiding inhibitor optimization. Recent studies have explored the structure-activity relationship of 39 PLK1 inhibitors using both 3D-QSAR and hologram QSAR (HQSAR) approaches [11]. The topomer CoMFA model demonstrated excellent statistical parameters with a cross-validation correlation coefficient (q²) of 0.501 and a non-cross-validation correlation coefficient (r²) of 0.977, indicating both strong predictive ability and estimation stability [11].

The most effective HQSAR model was obtained with a q² value of 0.537, an r² value of 0.815, and an optimal hologram length of 199 using atoms and bonds as fragment distinctions [11]. These QSAR models provide valuable insights into the steric and electrostatic requirements for potent PLK1 inhibition, highlighting specific molecular regions where bulky substituents enhance activity and areas where particular electrostatic properties are favorable.

Structure-Based Virtual Screening

Structure-based virtual screening has proven successful for identifying novel PLK1 inhibitors, particularly those targeting the PBD. Recent studies have employed integrated virtual screening strategies combining pharmacophore modeling, molecular docking, and molecular dynamics simulations to identify potent peptide inhibitors targeting the PLK1 PBD [15]. This approach identified five peptides (PLs 1-5) with strong binding affinity for PLK1, with the most promising candidate (PL-1) exhibiting a dissociation constant of 3.11 ± 0.05 nM in MST assays [15].

Molecular docking simulations have been instrumental in understanding the binding modes of inhibitors within the PLK1 active site. These studies consistently identify key interactions with residues including LEU491, ASN533, TRP414, HIS538, and ARG557 in the PBD, providing a structural framework for rational inhibitor design [11]. For kinase domain inhibitors, docking studies reveal characteristic hydrogen bonding patterns with the hinge region and complementary hydrophobic interactions within the ATP-binding pocket.

Figure 3: Computational Workflow for PLK1 Inhibitor Design. The integrated approach combines 3D-QSAR modeling, virtual screening, and molecular docking to identify and optimize novel PLK1 inhibitors, with validation against known structural data.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for PLK1 Structural Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Expression Constructs | Human PLK1 (residues 367-603) for PBD [13] | Protein production for structural studies |

| Crystallization Tools | PoloBoxTide peptide (MAGPMQ-S-pT-P-LNGAKK) [12] | Co-crystallization with PBD to determine binding mode |

| Chemical Inhibitors | BI-2536, Volasertib, Onvansertib, GSK461364 [1] | ATP-competitive inhibitors for kinase domain studies |

| PBD-Targeting Compounds | Polotyrin [14], PL-1 peptide (Kd = 3.11 nM) [15] | Cryptic pocket binders and peptide inhibitors for PBD studies |

| Mutagenesis Systems | H538A/K540M phosphobinding mutants [12], Y421A/L478A/Y481D Tyr pocket mutants [14] | Functional validation of key binding residues |

| Cell Line Models | HeLa Flp-In T-REx inducible expression system [14] | Cellular localization and functional studies |

| Antibodies | Anti-GFP, anti-PLK1, centromere/centrosome markers [14] | Immunofluorescence localization studies |

The structural biology of PLK1 reveals a sophisticated regulatory system based on the cooperative interplay between its kinase domain and polo-box domain. The kinase domain provides catalytic function through a conserved serine/threonine kinase fold with a well-characterized ATP-binding pocket, while the polo-box domain serves as a phosphopeptide-binding module that directs subcellular localization and substrate specificity. The autoinhibitory mechanisms involving KD-PBD interactions, along with activation processes through phosphorylation and cofactor binding, create multiple layers of regulation that ensure precise spatiotemporal control of PLK1 activity during cell division.

From a therapeutic perspective, the unique structural features of both domains offer attractive opportunities for targeted inhibition. While traditional ATP-competitive inhibitors have advanced clinically, the emergence of PBD-targeted inhibitors represents a promising alternative approach with potential for enhanced selectivity. The integration of structural biology with computational methods, particularly 3D-QSAR modeling and structure-based virtual screening, continues to drive the discovery and optimization of novel PLK1 inhibitors. As our understanding of PLK1 structure-function relationships deepens, particularly regarding allosteric regulatory mechanisms and domain cooperation, new opportunities will emerge for developing innovative therapeutic strategies targeting this essential mitotic regulator in cancer.

Polo-like kinase 1 (PLK1) is a serine/threonine-protein kinase that performs a pivotal role as a regulator of cell cycle progression, with essential functions in centrosome maturation, bipolar spindle formation, chromosome segregation, and cytokinesis [16] [2]. As a recognized marker of cellular proliferation, PLK1 is overexpressed in a wide spectrum of human cancers, and its elevated expression frequently correlates with poor prognosis, positioning it as an attractive target for anticancer drug development [16] [2]. The exploration of PLK1 inhibitors represents a significant chapter in targeted cancer therapy, beginning with first-generation ATP-competitive compounds and evolving into a sophisticated field integrating structural biology, computational modeling, and combination treatment strategies. This review chronicles the historical development of PLK1 inhibitors, from the early clinical candidate BI2536 to the current pipeline of investigational agents, with particular emphasis on the growing role of quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models in guiding inhibitor design.

Early PLK1 Inhibitors and Clinical Foundations

First-Generation ATP-Competitive Inhibitors

The initial wave of PLK1 inhibitor development yielded several ATP-competitive compounds that entered clinical trials, establishing the foundational knowledge of their therapeutic potential and limitations.

BI 2536 was the first PLK1 inhibitor to enter human studies [17]. This potent small-molecule inhibitor demonstrated activity at nanomolar concentrations and became a prototype for the class [16]. Preclinical studies revealed that BI 2536 significantly reduced cell viability in various cancer models, including neuroblastoma, where it induced G2/M cell cycle arrest and apoptosis [16]. In multiple myeloma, BI 2536 exhibited potent activity against malignant plasma cells, with cell death occurring through apoptosis and endoduplication due to disrupted cytokinesis [18]. Despite these promising preclinical results, the clinical development of BI 2536 as a monotherapy was ultimately discontinued, though combination studies remained active [17].

Volasertib (BI 6727) emerged as a second-generation PLK1 inhibitor with an improved pharmacokinetic profile, enhanced safety, and superior efficacy compared to its predecessor [17]. Biophysical studies using fluorescence spectroscopy demonstrated that both BI 2536 and volasertib form stable protein-ligand complexes with PLK1, exhibiting higher binding affinity than ATP [19]. A critical finding was that the binding constant between BI 2536 and PLK1 increases approximately 100-fold in the presence of the phosphopeptide Cdc25C-p, which docks to the polo box domain and releases the kinase domain [19]. Volasertib progressed to Phase I/II clinical trials and showed notable clinical responses in a subset of patients, with response rates between 25% and 27% in randomized trials [20].

GSK461364A represented another early clinical candidate that showed potent antitumor effects, particularly in p53-mutated cancer cells in preclinical models [17]. However, clinical development faced challenges due to a high incidence of venous thrombotic emboli, necessitating coadministration with anticoagulants [17]. Similar to BI 2536 and volasertib, GSK461364 interacts with the Cys133 residue in the PLK1 ATP-binding pocket [20].

Table 1: Early Generation PLK1 Inhibitors in Clinical Development

| Inhibitor | Generation | Clinical Status | Key Characteristics | Identified Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BI 2536 | First | Monotherapy terminated; combination studies ongoing | First human study; nanomolar potency [17] | Limited efficacy as monotherapy in advanced cancers [17] |

| Volasertib (BI 6727) | Second | Phase I/II [17] | Improved PK/PD profile; enhanced safety and efficacy [17] | Variable patient response; lack of predictive biomarkers [20] |

| GSK461364A | First | Early clinical trials | Preferential activity in p53-mutated cells [17] | High incidence of venous thrombotic emboli [17] |

Mechanisms of Action and Cellular Effects

PLK1 inhibitors exert their anticancer effects through multifaceted mechanisms that disrupt normal cell cycle progression in rapidly dividing cancer cells. The primary molecular consequences of PLK1 inhibition include:

- Cell Cycle Arrest: Treatment with BI 2536 induces accumulation of cells in the G2/M phase, preventing proper mitotic entry and progression [16].

- Apoptosis Induction: PLK1 inhibition triggers programmed cell death through caspase-3 activation and modulation of Bcl-2 family proteins [16] [2].

- Mitotic Catastrophe: Disrupted chromosome segregation and cytokinesis lead to the formation of multinucleated cells and cell death [18].

- Autophagic Modulation: BI 2536 treatment in neuroblastoma cells increased LC3-II puncta formation and LC3-II expression while abrogating autophagic flux by reducing SQSTM1/p62 expression and AMPKαT172 phosphorylation [16].

- Transcriptional Reprogramming: Real-time PCR array analysis revealed that PLK1 inhibition regulates genes involved in apoptosis (BIRC7, TNFSF10) and cell survival (LGALS1, DAD1) [16].

The Rise of Structural and Computational Approaches

PLK1 Structure-Informed Drug Design

The structural characterization of PLK1 has been instrumental in advancing inhibitor design. PLK1 comprises an N-terminal catalytic kinase domain and a C-terminal polo-box domain (PBD) that regulates its subcellular localization and substrate interactions [2] [21]. The kinase domain contains approximately 252 amino acids and features an ATP-binding pocket that has been the primary target for most first-generation inhibitors [21].

Key amino acid residues critical for inhibitor binding include Cys67, Lys82, Cys133, Phe183, and Asp194 [21]. Structural analyses reveal that most ATP-competitive inhibitors, including BI2536, volasertib, and GSK461364, interact with the Cys133 residue, while others like NMS-1286937 (onvansertib) engage with both Glu131 and Cys133 [20]. These structural insights have facilitated the rational design of inhibitors with improved potency and selectivity.

Diagram 1: Structural domains of PLK1 and key binding site residues targeted by inhibitors. The kinase domain contains the ATP-binding pocket with critical residues for inhibitor interaction.

3D-QSAR and Pharmacophore Modeling

Advances in computational approaches have significantly accelerated PLK1 inhibitor optimization. A landmark QSAR study analyzed 368 known PLK1 inhibitors to elucidate the structural requirements for effective inhibition [21]. The resulting pharmacophoric hypotheses were validated through genetic function algorithm and multiple linear regression analyses, yielding a prognostic QSAR model with strong statistical criteria (r² = 0.76, r²adj = 0.76, r²pred = 0.75, Q² = 0.73) [21].

Key structural features identified for optimal PLK1 inhibition include:

- Hydrophobic Interactions: Aromatic rings positioned to engage with hydrophobic regions of the binding pocket

- Hydrogen Bond Acceptors/Donors: Capability to form conventional hydrogen bonds with key residues like Lys82 and Asp194

- Specific Steric Requirements: Optimal molecular shape and size complementarity with the ATP-binding pocket

This hybridized 3D-QSAR approach successfully guided the design and synthesis of 4-benzyloxy-1-(2-arylaminopyridin-4-yl)-1H-pyrazole-3-carboxamides as novel PLK1 inhibitors with decent potency and selectivity [22]. The model was further utilized to screen the NCI database, identifying new PLK1 inhibitory hits with IC50 values ranging from 1.49 to 6.35 μM [21].

Diagram 2: QSAR-guided pharmacophore modeling workflow for identifying novel PLK1 inhibitors. The process integrates ligand-based and structure-based drug design approaches.

Current Clinical Candidates and Emerging Directions

Contemporary PLK1 Inhibitors in Development

The clinical landscape of PLK1 inhibitors continues to evolve with next-generation candidates advancing through pipelines:

Onvansertib represents a prominent clinical-stage PLK1 inhibitor currently under investigation by Cardiff Oncology. It is being evaluated across multiple cancer types, including metastatic colorectal cancer, with a focus on combination therapies [20].

Plogosertib (CYC140) is a novel PLK1 inhibitor developed by Cyclacel Pharmaceuticals that has demonstrated promising preclinical activity and is progressing through clinical development [20].

Volasertib continues to be investigated in new clinical contexts. Notable Labs acquired global rights to volasertib and plans to utilize its predictive precision medicine platform to identify responsive patient populations for a Phase II trial [20].

Table 2: Emerging PLK1 Inhibitors in Clinical Development

| Inhibitor | Company/Developer | Clinical Status | Therapeutic Focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| Onvansertib | Cardiff Oncology | Phase II | Metastatic colorectal cancer, prostate cancer [20] |

| Volasertib (NBL-001) | Notable Labs | Phase II planned (with biomarker strategy) | Acute myeloid leukemia [20] |

| Plogosertib (CYC140) | Cyclacel Pharmaceuticals | Phase I/II | Leukemia, solid tumors [20] |

Biomarker-Driven Approaches and Combination Strategies

The variable clinical responses to PLK1 inhibitors have underscored the necessity for predictive biomarkers to identify susceptible patient populations. Research indicates that PLK1 inhibitors may exhibit enhanced efficacy in specific genetic contexts:

- p53 Mutations: Preclinical data suggests that GSK461364 shows greater sensitivity in p53-mutated cancer cells compared to p53-wild type cells [17].

- RAS Mutations: PLK1 has emerged as a synthetic lethal target in KRAS-mutant colorectal cancer, with mutant KRAS cells exhibiting particular dependence on mitotic function genes including PLK1 [9].

- PLK1 Overexpression: Tumors with elevated PLK1 expression levels may represent a population more likely to respond to PLK1-directed therapy [17].

Combination therapy approaches represent the forefront of PLK1 inhibitor clinical development. Rational combination strategies include:

- Chemotherapy Sensitization: PLK1 inhibition can enhance the efficacy of conventional chemotherapeutic agents by overcoming resistance mechanisms [2].

- Targeted Therapy Synergy: Combinations with PI3K/AKT, mTOR, or MEK inhibitors can address parallel signaling pathways and mitigate compensatory resistance mechanisms [2].

- Immunotherapy Integration: PLK1 regulates the expression of immune checkpoint-related proteins, creating opportunities for combination with immunotherapy [2]. Studies show that PLK1 expression correlates with immunophenotyping, immune cell infiltration, tumor mutational burden, and microsatellite instability across various tumors [2].

Experimental Methodologies in PLK1 Inhibitor Research

Essential Research Protocols

The evaluation of PLK1 inhibitors employs a suite of standardized experimental approaches to assess compound efficacy, mechanisms of action, and cellular responses:

Cell Viability and Proliferation Assays

- Protocol: Cells are seeded in 96-well plates and treated with serially diluted inhibitors for 24-72 hours. Viability is assessed using colorimetric assays like CCK-8, which measures metabolic activity via absorbance at 450 nm [16].

- Data Analysis: IC50 values are calculated using nonlinear regression analysis in software such as GraphPad Prism [16].

Cell Cycle Analysis

- Protocol: Cells are fixed in ethanol, permeabilized with Triton X-100, treated with RNase A, and stained with propidium iodide [16].

- Data Acquisition: DNA content is analyzed by flow cytometry, with cell cycle phases quantified using specialized software like MultiCycle AV DNA analysis [16].

Apoptosis Detection

- Protocol: Cells are stained with FITC-Annexin V and propidium iodide in binding buffer, then analyzed by flow cytometry within 1 hour [16].

- Alternative Methods: Caspase-3 activity assays measure cleavage of specific substrates spectrophotometrically at 405 nm [16].

Binding Affinity Studies

- Protocol: Fluorescence spectroscopy techniques quantify interactions between PLK1 and inhibitors, with calculations of Stern-Volmer constants to assess binding affinity [19].

- Advanced Applications: Molecular dynamics simulations complement experimental data to calculate binding free energies and identify key molecular interactions [19].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for PLK1 Inhibitor Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| PLK1 Inhibitors | BI 2536, Volasertib, GSK461364 | Mechanistic studies, dose-response assays | Target validation and efficacy assessment [17] [16] |

| Cell Lines | Neuroblastoma (SH-SY5Y, SK-N-BE(2)), Multiple Myeloma (U-266, MM.1S) | In vitro modeling | Disease-specific context for inhibitor testing [16] [18] |

| Apoptosis Detection | Annexin V-FITC/PI staining, Caspase-3 activity kits | Mechanism of action studies | Quantification of programmed cell death [16] |

| Cell Cycle Analysis | Propidium iodide, RNase A, Triton X-100 | Cell cycle profiling | Determination of mitotic arrest and DNA content [16] |

| Molecular Biology | Lentiviral particles (mRFP-GFP-LC3), Trizol for RNA extraction | Autophagy studies, gene expression analysis | Investigation of secondary cellular effects [16] |

The historical development of PLK1 inhibitors exemplifies the evolution of targeted cancer therapeutics, from initial ATP-competitive compounds to increasingly sophisticated agents designed with structural and computational guidance. While first-generation inhibitors like BI2536 established proof-of-concept for PLK1 targeting in humans, their limited efficacy as monotheracies highlighted the complexities of mitotic inhibition in advanced cancers. The subsequent integration of 3D-QSAR and pharmacophore modeling has illuminated critical structural requirements for effective PLK1 inhibition, enabling more rational inhibitor design. Contemporary research emphasizes biomarker-driven patient selection and rational combination strategies, acknowledging the intricate interplay between PLK1 and oncogenic signaling networks. As novel candidates like onvansertib and plogosertib advance through clinical development, the field continues to refine its approach to PLK1 inhibition, with computational structural biology playing an increasingly central role in developing more effective and selective therapeutic agents.

Fundamental Principles of 3D-QSAR in Kinase Inhibitor Design

Three-dimensional Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (3D-QSAR) represents a pivotal computational approach in modern drug discovery, particularly in the design of kinase inhibitors. This technical guide explores the fundamental principles of 3D-QSAR methodologies, framed within the context of Polo-like kinase 1 (PLK1) inhibitor research. As PLK1 emerges as a promising anticancer target due to its crucial role in cell cycle regulation and overexpression in various cancers, 3D-QSAR models provide invaluable insights for designing potent and selective inhibitors. This review comprehensively examines the theoretical foundations, key methodologies, practical applications, and experimental protocols underlying 3D-QSAR, along with emerging trends that integrate these approaches with complementary computational techniques to accelerate kinase inhibitor development.

Polo-like kinase 1 (PLK1) is a serine/threonine kinase that functions as a key regulator of mitotic progression, overseeing critical processes including centrosome maturation, spindle assembly, kinetochore-microtubule attachment, and cytokinesis [1]. The PLK1 structure comprises two primary functional domains: an N-terminal catalytic kinase domain (KD) responsible for enzymatic activity, and a C-terminal polo-box domain (PBD) that mediates protein-protein interactions and subcellular localization [1]. PLK1 is frequently overexpressed in various human cancers—including prostate, lung, and colon cancers—correlating with increased tumor aggressiveness and poor prognosis, thus establishing it as an attractive therapeutic target for anticancer drug development [4] [23].

The quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) paradigm operates on the fundamental principle that biological activity can be correlated with quantitative molecular descriptors derived from chemical structure. While traditional QSAR utilizes two-dimensional descriptors, 3D-QSAR advances this concept by incorporating the three-dimensional structural features of molecules, thereby providing superior capability to model steric, electrostatic, and hydrophobic interactions between ligands and their biological targets [24]. In kinase inhibitor design, 3D-QSAR has proven particularly valuable for optimizing inhibitor potency and selectivity, especially for challenging targets like PLK1 where selectivity over other PLK family members (PLK2, PLK3) is essential due to their divergent biological functions [25].

Theoretical Foundations of 3D-QSAR

Fundamental Principles and Assumptions

3D-QSAR methodologies are grounded in several key principles. First, they assume that similar molecular structures elicit similar biological responses, and that differences in biological activity correlate quantitatively with changes in molecular fields surrounding the compounds. Second, these approaches presume that the bioactive conformation can be reasonably approximated, and that ligand-receptor binding is dominated by non-covalent interactions measurable through molecular field analysis [24] [4].

The 3D-QSAR workflow typically involves multiple critical steps: (1) selection of a structurally diverse dataset of compounds with known biological activities; (2) identification of putative bioactive conformations; (3) molecular alignment based on common structural features or pharmacophores; (4) calculation of interaction fields around the aligned molecules; (5) correlation of these field values with biological activity using statistical methods like Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression; and (6) model validation using internal and external test sets [4] [26].

Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA)

CoMFA represents one of the most established 3D-QSAR techniques. It characterizes molecules based on their steric (Lennard-Jones potential) and electrostatic (Coulombic potential) fields sampled at regular grid points surrounding the aligned molecules [4] [27]. The resulting field values serve as independent variables in PLS regression to generate a predictive model. The quality of CoMFA models is typically evaluated using several statistical parameters: the cross-validated correlation coefficient (Q²) which should exceed 0.5 for a predictive model, the non-cross-validated correlation coefficient (R²), the standard error of estimate (SEE), and the predictive R² (R²pred) for an external test set [4].

A recent application of CoMFA on pteridinone-based PLK1 inhibitors demonstrated excellent predictive capability with Q² = 0.67 and R² = 0.992, while the test set validation yielded R²pred = 0.683, confirming model robustness [4]. The contour maps derived from CoMFA models visually guide medicinal chemists by identifying regions where steric bulk or specific electrostatic properties enhance or diminish biological activity.

Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA)

CoMSIA extends beyond CoMFA by incorporating additional molecular fields including hydrophobic, hydrogen bond donor, and hydrogen bond acceptor fields [4] [25]. Unlike CoMFA's potential functions, CoMSIA employs a Gaussian function to calculate similarity indices, avoiding singularities at atomic positions and providing smoother sampling of molecular fields. This approach often generates models with superior interpretative value and has been successfully applied in PLK1 inhibitor design [25].

In studies on pteridinone derivatives, CoMSIA models demonstrated impressive statistical parameters, with CoMSIA/SHE yielding Q² = 0.69 and R² = 0.974, while CoMSIA/SEAH produced Q² = 0.66 and R² = 0.975 [4]. The predictive power of these models was confirmed through external validation (R²pred = 0.758 and 0.767, respectively), underscoring their utility in PLK1 inhibitor optimization.

Self-Organizing Molecular Field Analysis (SOMFA)

SOMFA represents a simpler grid-based 3D-QSAR method that utilizes molecular shape and electrostatic potential to construct QSAR models [24]. While less computationally intensive than CoMFA or CoMSIA, SOMFA has demonstrated utility in kinase inhibitor design, as evidenced by its successful application in modeling HER2 kinase inhibitors with reasonable cross-validated q² (0.767) and non-cross-validated r² (0.815) values [24].

Table 1: Comparison of Major 3D-QSAR Methodologies in Kinase Inhibitor Design

| Method | Molecular Fields | Statistical Approach | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CoMFA | Steric, Electrostatic | PLS Regression | Well-established, easily interpretable contour maps | Sensitive to molecular alignment and orientation |

| CoMSIA | Steric, Electrostatic, Hydrophobic, H-bond Donor, H-bond Acceptor | PLS Regression | Additional field types, Gaussian function avoids singularities | More computationally intensive |

| SOMFA | Molecular shape, Electrostatic potential | PLS Regression | Computational simplicity, minimal parameters | Limited field types, less granular information |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Molecular Alignment Techniques

Molecular alignment constitutes perhaps the most critical step in 3D-QSAR model development, as the quality of alignment directly impacts model robustness [4]. Several alignment strategies are commonly employed:

Pharmacophore-based alignment utilizes common structural features or pharmacophoric elements to superimpose molecules. For example, in studies of PLK1 inhibitors, researchers often align compounds based on their core scaffold that interacts with the hinge region of the kinase domain [25] [27].

Docking-based alignment relies on conformational sampling and scoring functions to predict binding modes within the target's active site, followed by alignment of these docked conformations [24] [4]. This approach benefits from structural insights but depends on docking accuracy.

Distill rigid alignment represents another method where molecules are aligned based on maximum common substructures using algorithms implemented in molecular modeling software like SYBYL-X [4]. In a study of pteridinone derivatives, this technique involved energy minimization of all compounds using the Tripos force field with Gasteiger-Hückel atomic partial charges, followed by alignment with a defined common substructure [4].

Field Calculation and Statistical Validation

Following molecular alignment, interaction fields are calculated at grid points with typical spacing of 1-2 Å extending 4 Å beyond all aligned molecules in three-dimensional space [4]. For CoMFA, steric fields are computed using Lennard-Jones potential with a default sp³ carbon probe atom carrying a +1 charge, while electrostatic fields employ Coulombic potential with a distance-dependent dielectric constant [27]. Energy values are typically truncated at 30 kcal/mol to prevent extreme values from dominating the analysis [4].

Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression remains the standard statistical method for correlating field values with biological activity in 3D-QSAR [4]. The leave-one-out (LOO) cross-validation approach determines the optimal number of components (ONC) by systematically removing each compound, developing a model with the remaining compounds, and predicting the activity of the omitted compound. The cross-validated coefficient Q² is calculated as:

Q² = 1 - PRESS/SSY

where PRESS is the predictive sum of squares and SSY is the sum of squares of the experimental activities [4]. External validation using a test set of compounds not included in model building provides the most rigorous assessment of predictive ability, with R²pred > 0.6 generally indicating a robust model [4].

Integrated Workflow for 3D-QSAR Model Development

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for developing and validating 3D-QSAR models in kinase inhibitor design:

Diagram 1: Comprehensive workflow for 3D-QSAR model development and validation in kinase inhibitor design.

Application to PLK1 Inhibitor Design

Case Studies and Success Stories

3D-QSAR approaches have demonstrated significant utility in the design and optimization of PLK1 inhibitors across diverse chemical scaffolds. A recent study on pteridinone derivatives exemplified the power of integrated 3D-QSAR modeling, where CoMFA and CoMSIA models successfully guided the identification of critical structural requirements for PLK1 inhibition [4]. Molecular docking complemented these findings by revealing key interactions with active site residues including R136, R57, Y133, L69, L82, and Y139—information that enriched the interpretation of 3D-QSAR contour maps [4].

In another innovative approach, researchers developed a hybridized 3D-QSAR model by combining two distinct series of PLK1 inhibitors—44 compounds of 8-amino-4,5-dihydro-1H-pyrazolo[4,3-h]quinazoline-3-carboxamides and 36 thiophene-2-carboxamide derivatives [25]. This hybrid model successfully identified a novel scaffold, 4-benzyloxy-1-(2-arylaminopyridin-4-yl)-1H-pyrazole-3-carboxamides, which exhibited decent potency and improved selectivity for PLK1 [25]. The steric and electrostatic contour maps from this hybrid CoMFA model guided rational modifications by highlighting regions where bulky substituents enhanced activity (green contours) and areas favoring electropositive or electronegative groups (blue and red contours, respectively) [25].

A QSAR-guided pharmacophore modeling study analyzed 368 known PLK1 inhibitors to extract essential structural features for PLK1 inhibition [21]. The optimal QSAR model (r² = 0.76, r²pred = 0.75, Q² = 0.73) highlighted the importance of π-interactions and conventional hydrogen bonding with key residues including Cys67, Lys82, Cys133, Phe183, and Asp194 in the PLK1 binding pocket [21]. This model successfully identified new inhibitory hits from the NCI database, with the most potent compound exhibiting an IC50 of 1.49 μM [21].

Integration with Complementary Computational Approaches

Modern 3D-QSAR implementations increasingly leverage synergistic combinations with other computational techniques to enhance predictive accuracy and mechanistic understanding:

Molecular Docking Integration: Docking provides atomic-level insights into ligand-receptor interactions that inform molecular alignment and aid contour map interpretation [4] [27]. For PLK1 inhibitors, docking studies consistently identify crucial hydrogen bond interactions with hinge region residues and hydrophobic interactions within the selectivity pocket [4] [21].

Pharmacophore Modeling Combination: Pharmacophore features derived from structural analysis or ligand-based approaches constrain conformational search spaces and guide molecular alignment in 3D-QSAR [21] [27]. A combined study utilizing pharmacophore modeling, docking, and 3D-QSAR on dihydropyrazolo-quinazoline derivatives demonstrated how this integrated approach could elucidate comprehensive structure-activity relationships for PLK1 inhibitors [27].

Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations: MD simulations validate the stability of binding poses predicted by docking and provide dynamic insights into ligand-receptor interactions [4] [23]. In studies of pteridinone derivatives, MD simulations confirmed that potent inhibitors remained stable in the PLK1 active site throughout 50 ns simulations, reinforcing design decisions based on 3D-QSAR models [4].

Table 2: Key Active Site Residues and Their Roles in PLK1 Inhibition

| Residue | Role in PLK1 Structure/Function | Interaction Type | Importance in Inhibitor Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lys82 | ATP anchoring and orientation | Hydrogen bonding, Electrostatic | Critical for inhibitor binding to kinase domain |

| Cys133 | Shapes catalytic site geometry | Hydrophobic, van der Waals | Influences inhibitor selectivity |

| Asp194 | Catalytic machinery component | Hydrogen bonding | Essential for potent inhibition |

| Phe183 | Hydrophobic pocket formation | π-π Stacking, Hydrophobic | Contributes to binding affinity |

| Leu69, Leu82 | Hydrophobic pocket formation | van der Waals, Hydrophobic | Enhances inhibitor potency |

Successful implementation of 3D-QSAR in kinase inhibitor design requires specialized software tools, databases, and experimental resources. The following table catalogues essential solutions referenced in recent PLK1 inhibitor studies:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for 3D-QSAR Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function in 3D-QSAR Workflow | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Modeling Software | SYBYL-X, MOE, Discovery Studio | Molecular optimization, alignment, field calculation, PLS analysis | CoMFA/CoMSIA model generation for pteridinone derivatives [4] |

| Docking Programs | AutoDock, AutoDock Vina, GOLD | Binding pose prediction, conformational analysis | Docking studies for quinazoline derivatives [24] |

| Descriptor Calculation | PaDEL, Mold2, QuBiLs-MAS | Molecular descriptor generation | Conformation-independent QSAR on 530 PLK1 inhibitors [28] |

| Chemical Databases | ChEMBL, ZINC, NCI Database | Source of bioactive compounds and diverse screening libraries | Virtual screening for novel PLK1 inhibitors [21] |

| Kinase Assay Kits | HTScan Kinase Assay Kit, ADP-Glo Assay | Experimental activity determination for model training/validation | Biological activity measurement for HER2 inhibitors [24] |

| MD Simulation Packages | GROMACS, AMBER, CHARMM | Validation of binding stability and interaction analysis | MD simulations of PLK1-inhibitor complexes [4] [23] |

Emerging Trends and Future Perspectives

The field of 3D-QSAR continues to evolve through integration with emerging computational approaches and expanding applications in kinase inhibitor discovery. Several promising trends are shaping future developments:

Hybrid QSAR Models: Combining 3D-QSAR with other QSAR approaches (2D, 4D) provides comprehensive insights that leverage the strengths of each methodology. The successful development of hybridized 3D-QSAR models for PLK1 inhibitors demonstrates how integrating multiple chemical series can yield more robust predictive models with broader applicability domains [25].

Machine Learning Enhancement: Incorporating machine learning algorithms for descriptor selection, non-linear relationship modeling, and activity prediction represents a natural evolution of traditional 3D-QSAR approaches. These techniques may help address current limitations in handling highly complex structure-activity relationships.

Structural Biology Integration: As structural databases expand with increasing numbers of kinase-inhibitor complexes, 3D-QSAR models benefit from more accurate bioactive conformations and alignment rules derived from experimental structures. The growing availability of PLK1-inhibitor crystal structures continues to enhance model quality and interpretability [1] [23].

Selectivity Modeling: Developing 3D-QSAR models that explicitly address kinase selectivity remains a critical challenge and active research area. Successful design of PLK1 inhibitors with reduced off-target effects against other kinases (particularly PLK2 and PLK3) requires models that capture subtle differences in binding sites across kinase families [25].

In conclusion, 3D-QSAR methodologies have established themselves as indispensable tools in the rational design of kinase inhibitors, with particular demonstrated success in PLK1 inhibitor development. As these approaches continue to evolve through integration with complementary computational techniques and expanding chemical data resources, their impact on accelerating kinase-targeted drug discovery is poised to grow significantly. The fundamental principles outlined in this technical guide provide researchers with a foundation for applying these powerful methodologies to current and future challenges in kinase inhibitor design.

Polo-like kinase 1 (PLK1) is a serine/threonine kinase recognized as a pivotal regulator of cell cycle progression, mitosis, and DNA damage response. Its overexpression is a well-established characteristic of numerous cancers, including those of the prostate, breast, lung, and colon, and is frequently associated with poor patient prognosis [29] [1]. This established link between PLK1 and oncogenesis has cemented its status as a high-value target for anticancer drug discovery. The quest for effective inhibitors has increasingly turned to computational approaches, with 3D Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (3D-QSAR) modeling emerging as a powerful tool for elucidating the essential structural features required for potency and selectivity. This whitepaper examines three key chemical scaffolds—Pteridinones, Pyrazoles, and Quinazolines—exploring their role in PLK1 inhibition within the context of 3D-QSAR-guided drug design. It provides a detailed technical overview for researchers and drug development professionals, complete with quantitative data, experimental protocols, and visualization of the critical relationships in this field.

PLK1 as a Therapeutic Target: Structure and Function

PLK1 is a 603-amino acid protein featuring two primary functional domains: an N-terminal kinase domain (KD) responsible for catalytic activity and a C-terminal polo-box domain (PBD) that mediates substrate recognition and subcellular localization [29] [1]. The kinase domain contains a conserved ATP-binding pocket, which has been the primary focus for most small-molecule inhibitor development. Key residues within this pocket, including Cys133 in the hinge region, Lys82, and Asp194, are critical for ATP binding and are frequently targeted by inhibitors to achieve competitive inhibition [29] [1]. The PBD, comprising two polo-boxes (PB1 and PB2), recognizes phosphorylated serine/threonine motifs on substrate proteins. Targeting the PBD offers an alternative strategy to disrupt PLK1's specific interactions with its substrates, potentially leading to higher selectivity over other kinases [1] [30].