Advances in Molecular Dynamics Simulation Analysis for DNA Intercalators: From Binding Mechanisms to Rational Drug Design

This comprehensive review explores the evolving role of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations in characterizing DNA-intercalator interactions, a critical area for anticancer drug development.

Advances in Molecular Dynamics Simulation Analysis for DNA Intercalators: From Binding Mechanisms to Rational Drug Design

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores the evolving role of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations in characterizing DNA-intercalator interactions, a critical area for anticancer drug development. We examine foundational principles of intercalation dynamics, methodological approaches for binding energy prediction, and optimization strategies to enhance computational efficiency and accuracy. The article highlights how ensemble MD simulations provide more reproducible binding energy predictions that align with experimental values, compares force field performance and validation techniques, and discusses emerging applications in designing selective DNA-targeting agents. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this synthesis of current methodologies and validation frameworks offers practical guidance for implementing MD simulations in rational drug design pipelines targeting DNA interfaces.

Understanding DNA Intercalation: Molecular Mechanisms and Energetic Principles

Fundamental Biophysics of DNA-Drug Intercalation

Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) is not only the carrier of genetic information but also a primary target for many anticancer, antibiotic, and antiviral drugs. Understanding the fundamental biophysics of how small molecule drugs interact with DNA is crucial for rational drug design and development. Drug intercalation represents a critical binding mode in which planar aromatic molecules insert between DNA base pairs, disrupting essential cellular processes such as replication and transcription [1]. This application note examines the biophysical principles underlying DNA-drug intercalation, with emphasis on molecular dynamics simulation approaches for characterizing these interactions. We provide researchers with current methodologies, quantitative data, and protocols for investigating intercalation mechanisms, binding energetics, and structural consequences relevant to pharmaceutical development.

The intercalation process induces significant structural modifications in DNA, including helix unwinding, elongation, and local conformational changes that ultimately interfere with DNA-protein interactions and biological function [1] [2]. The neighbor exclusion principle generally applies, limiting intercalation to alternate sites along the DNA helix due to the substantial structural distortions caused by binding [1]. The binding is largely driven by π-π stacking interactions between the intercalator's aromatic rings and the flanking DNA bases, with additional stabilization from van der Waals forces, hydrogen bonding, and electrostatic interactions [1].

Quantitative Biophysical Data on DNA Intercalation

Conductivity Changes Upon Drug Intercalation

Recent investigations have revealed that drug intercalation significantly alters the electrical properties of DNA, which has implications for both molecular electronics and understanding biological charge transport mechanisms.

Table 1: Impact of Drug Intercalation on DNA Conductivity

| Drug Molecule | PDB ID | DNA Sequence | Conductivity After Intercalation | Conductivity Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAR70 | 1R68 | (CGATCG)₂ | 3.37 × 10⁻⁷ G₀ | ~140-fold decrease |

| Nogalamycin | 1D22 | (CGATCG)₂ | 2.01 × 10⁻⁵ G₀ | Slight decrease |

| Cyanomorpholinodoxorubicin | 385D | (CGATCG)₂ | 2.65 × 10⁻⁶ G₀ | ~9-fold decrease |

| Bare B-DNA (Control) | - | (CGATCG)₂ | 2.38 × 10⁻⁵ G₀ | - |

The insertion of small drug molecules into DNA generates new energy levels that alter the positions of the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO), resulting in a narrowed bandgap and consequently reduced conductivity of the complex [3]. The extent of conductivity reduction depends on both the specific drug molecule and the number of intercalated molecules, with fewer inserted molecules leading to lower conductivity [3].

Binding Energies of DNA-Intercalator Complexes

Accurate determination of binding energies is essential for quantifying intercalation strength and designing more effective therapeutics.

Table 2: Experimentally Determined and Computationally Predicted Binding Energies

| Intercalator | Experimental Binding Energy (kcal/mol) | Computational Method | Predicted Binding Energy (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Doxorubicin | -7.7 ± 0.3 to -9.9 ± 0.1 | MM/PBSA (25 replicas of 100 ns) | -7.3 ± 2.0 |

| Doxorubicin | -7.7 ± 0.3 to -9.9 ± 0.1 | MM/GBSA (25 replicas of 100 ns) | -8.9 ± 1.6 |

| Proflavine | -5.9 to -7.1 | MM/PBSA (25 replicas of 10 ns) | -5.6 ± 1.4 |

| Proflavine | -5.9 to -7.1 | MM/GBSA (25 replicas of 10 ns) | -5.3 ± 2.3 |

Recent studies demonstrate that the reproducibility and accuracy of binding energy predictions depend more on the number of simulation replicas than on simulation length alone [4] [5]. Bootstrap analyses revealed that 6 replicas of 100 ns or 8 replicas of 10 ns provide a good balance between computational efficiency and accuracy within 1.0 kcal/mol from experimental values [4].

Molecular Mechanisms of Intercalation

Structural Consequences of Intercalation

Drug intercalation induces significant structural perturbations in DNA beyond simple base pair separation. The binding mode consists of the insertion of planar aromatic rings between DNA base pairs, leading to local unwinding and elongation of the DNA helix by approximately 3.4 Å per intercalation event [1]. This unwinding reduces the helical twist and separates base pairs near the binding site to fewer than 36 per turn [1].

The intercalation process can be conceptually understood as a multi-step mechanism involving DNA deformation, ligand insertion, and complex stabilization:

Two-Step Intercalation Mechanism of Phenanthriplatin

Single-molecule force spectroscopy studies with optical tweezers have revealed detailed kinetic pathways for certain intercalators. Phenanthriplatin, a monofunctional anticancer agent, exhibits a distinct two-step binding mechanism [6]:

- Fast, reversible DNA lengthening with time constant τₒₙ,₁ = 10 ± 2 s, characterized by partial intercalation of the phenanthridine ring

- Slow, irreversible DNA elongation with time constant τₒₙ,₂ = 639 ± 90 s, involving covalent platinum-DNA bond formation

This mechanism demonstrates how reversible DNA intercalation can provide a robust transition state that is efficiently converted to an irreversible DNA-Pt bound state [6]. The geometric conformation of the complex is critical, as the stereoisomer trans-phenanthriplatin exhibits only the reversible fast DNA elongation without significant covalent binding [6].

Hydration Changes Upon Intercalation

Water molecules play an essential role in DNA structure and drug binding. Recent studies using chiral-selective vibrational sum frequency generation spectroscopy (chiral SFG) have demonstrated that drug binding disrupts chiral water structures in the DNA first hydration shell [7]. When netropsin binds to the minor groove of (dA)₁₂·(dT)₁₂ dsDNA, it preferentially displaces water molecules strongly hydrogen-bonded to thymine carbonyl groups in the DNA minor groove [7]. This water displacement reveals the roles of hydration in modulating site-specificity of drug binding to duplex DNA and offers mechanistic insights for rational drug design targeting DNA [7].

Computational Methodologies

Molecular Dynamics Simulation Protocols

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations provide powerful tools for investigating the structural, energetic, and dynamic aspects of DNA-intercalator interactions at atomic resolution.

Protocol 4.1.1: Ensemble MD Simulations for Binding Energy Prediction

Purpose: To accurately predict binding energies of DNA-intercalator complexes while addressing reproducibility limitations of single MD simulations.

Workflow Overview:

Detailed Procedures:

Initial Structure Preparation

System Setup

- Solvate the DNA-drug complex in explicit water molecules (e.g., TIP3P water model)

- Add appropriate ions to neutralize system charge and achieve physiological salt concentration (e.g., 100 mM NaCl)

- Ensure sufficient padding between periodic images (typically ≥ 10 Å)

Energy Minimization and Equilibration

- Perform steepest descent energy minimization to remove steric clashes

- Gradually heat system from 100 K to 300 K over 200 ps using Berendsen thermostat [1]

- Equilibrate system in NPT ensemble (constant number of particles, pressure, and temperature) for at least 1 ns

Production Simulation

- Run multiple independent replicas (6-25) of either short (10 ns) or long (100 ns) simulations [4]

- Use 2 fs integration time step with constraints on hydrogen bonds

- Employ particle mesh Ewald method for long-range electrostatic interactions

- Save trajectories at appropriate intervals (every 100 ps) for analysis

Binding Energy Calculation

- Apply Molecular Mechanics/Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area (MM/PBSA) or Molecular Mechanics/Generalized Born Surface Area (MM/GBSA) methods

- Include entropy corrections using normal mode analysis or quasi-harmonic approximation

- Account for deformation energy of DNA and ligand upon binding

- Average results across all replicas for statistically robust predictions [4]

Key Considerations:

- Reproducibility and accuracy depend more on the number of replicas than on simulation length [4]

- For optimal balance between computational efficiency and accuracy, use 6 replicas of 100 ns or 8 replicas of 10 ns [4]

- Include entropy and deformation energy corrections for accurate binding free energy values [4]

Protocol 4.1.2: DFT-NEGF Approach for Electronic Property Analysis

Purpose: To evaluate changes in electronic properties and charge transport through DNA after drug intercalation.

Procedures:

- Employ Density Functional Theory (DFT) with appropriate basis sets and exchange-correlation functionals

- Combine with Non-Equilibrium Green's Function (NEGF) formalism to model charge transport [3]

- Calculate HOMO-LUMO energy levels, band gaps, and conductivity changes

- Analyze orbital interactions and charge distribution in DNA-drug complexes

Molecular Docking Protocols

Protocol 4.2.1: DNA-Intercalator Docking Using AutoDock

Purpose: To predict binding modes and affinities of small molecules to DNA targets.

Procedures:

- Receptor Preparation

Ligand Preparation

- Generate 3D structures of intercalator molecules

- Assign Gasteiger charges and define rotatable bonds

Docking Parameters

Result Analysis

Experimental Techniques for Validation

Single-Molecule Force Spectroscopy

Principle: Optical tweezers monitor DNA extension changes during intercalation at constant applied force, providing insights into binding kinetics and mechanisms [6].

Protocol:

- Attach single λ-DNA molecules (16.5 µm contour length) between streptavidin-coated polystyrene beads

- Maintain constant stretching force (e.g., 15 pN) using force-feedback system

- Introduce intercalator solution while monitoring time-dependent DNA extension

- Analyze association and dissociation kinetics from extension changes

- Fit data to multi-exponential models to extract time constants for different binding steps [6]

Electrochemical Analysis of Drug-DNA Interactions

Principle: Voltammetric methods detect changes in electrochemical signals when drugs interact with DNA, providing information on binding mode and affinity [8].

Protocol:

- Immobilize drug molecules on electrode surface via passive adsorption

- Characterize electrochemical properties using cyclic voltammetry (CV) and differential pulse voltammetry (DPV)

- Optimize parameters including pH, scan rate, immobilization time, and drug concentration

- Monitor changes in oxidation peak potential and current of guanine base after drug-DNA interaction

- Calculate toxicity effect (S%) of drug candidates on DNA based on signal changes [8]

Chiral Vibrational Sum Frequency Generation (chiral SFG)

Principle: This nonlinear spectroscopic technique probes changes in DNA hydration structures when small-molecule drugs bind, offering unique insights into water displacement from binding sites [7].

Protocol:

- Drop-cast dsDNA samples (e.g., (dA)₁₂·(dT)₁₂) on quartz substrates

- Acquire phase-resolved chiral SFG spectra using s-polarized visible beam and p-polarized infrared beam

- Detect p-polarized SFG signals in the OH stretching region of water

- Titrate with drug molecules (e.g., netropsin) at varying molar ratios

- Analyze spectral changes to determine water displacement from minor groove [7]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Computational Tools for DNA Intercalation Research

| Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Sequences | (CGATCG)₂, (TGATCA)₂, (dA)₁₂·(dT)₁₂ | Standardized sequences for reproducible intercalation studies and comparison across laboratories |

| Reference Intercalators | MAR70, Nogalamycin, Doxorubicin, Proflavine, Ethidium Bromide | Well-characterized compounds for method validation and control experiments |

| Computational Software | AutoDock 4.2, DESMOND, AMBER, GROMACS | Molecular docking, dynamics simulations, and binding energy calculations |

| Force Fields | AMBER99, OPLS2005 | Parameterization of DNA and small molecules for molecular dynamics simulations |

| Experimental Techniques | Optical Tweezers, Chiral SFG, Voltammetry, ITC, DSC | Characterization of binding kinetics, hydration changes, electronic properties, and thermodynamics |

| Analysis Methods | MM/PBSA, MM/GBSA, DFT-NEGF | Prediction of binding energies and electronic property changes |

The fundamental biophysics of DNA-drug intercalation involves complex interactions that span multiple spatial and temporal scales. Through integrated computational and experimental approaches, researchers can now characterize these interactions with unprecedented detail. Molecular dynamics simulations, particularly ensemble approaches with multiple replicas, provide reliable predictions of binding energies and mechanisms [4]. Advanced spectroscopic techniques like chiral SFG reveal the critical role of water displacement in binding specificity and affinity [7]. The protocols and methodologies outlined in this application note provide researchers with comprehensive tools for investigating DNA-intercalator interactions, supporting rational drug design efforts targeting DNA in anticancer and antimicrobial therapy development.

Key Structural Parameters and Energetic Drivers of Binding

The rational design of DNA-targeting drugs relies on a comprehensive understanding of the key structural parameters and energetic drivers that govern DNA-intercalator binding. Such binding events are central to the mechanism of action of many anticancer drugs, which function by inhibiting DNA unwinding and transcription. The immense therapeutic potential is tempered by a common challenge: low specificity, which leads to a wide array of severe side effects [9]. Overcoming this requires a deep, atomic-level knowledge of the binding landscape. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation has emerged as a powerful tool for elucidating these complex interactions, providing insights that are often difficult to obtain through experimental methods alone [10] [11]. This document details the critical structural and energetic features of DNA-intercalator complexes and provides standardized protocols for their computational analysis, framing this within the broader context of employing MD simulations for DNA intercalator research.

Key Structural Parameters of DNA-Intercalator Complexes

The binding of intercalators to DNA induces significant structural rearrangements and is characterized by specific, quantifiable parameters. These parameters are crucial for understanding binding affinity and selectivity.

Base Pair and Backbone Dynamics

Intercalation fundamentally alters local DNA geometry. Microsecond-scale MD simulations have revealed that DNA duplexes exhibit significant dynamical behavior, including rare events such as spontaneous base flipping and the formation of cross-strand intercalative stacking (XSIS) states, where nucleotides within a longitudinally sheared base pair become unstacked and restacked with nucleotides from the opposite strand [10]. Furthermore, the DNA backbone samples different conformational substates (BI/BII), and transitions between these states can be influenced by the presence of an intercalator.

Minor Groove Recognition and Multi-Ligand Binding

For minor-groove binders like distamycin A (DST) and netropsin (NET), the binding mode is highly dependent on the base sequence and the resulting groove geometry. Studies on model ligand-DNA systems show that a sequence like 5'-AAGTT-3', which has a wider or more flexible minor groove, favors a 2:1 binding mode (two DST molecules per site) across all concentration ratios. In contrast, a narrow 5'-AAAAA-3' site initially favors 1:1 binding, transitioning to a 2:1 mode only at higher DST/DNA ratios [12]. This highlights the critical role of sequence-specific minor groove width and flexibility as a structural parameter for binding.

Table 1: Key Structural Parameters in DNA-Intercalator Complexes

| Parameter | Description | Experimental/Simulation Insight |

|---|---|---|

| Base Pair Step Parameters | Changes in twist, roll, rise, and slide upon intercalation. | Quantified from MD trajectories; significant elongation and unwinding of the DNA helix are observed [9]. |

| Backbone Conformation | Sampling of BI/BII substates by the phosphodiester backbone. | MD simulations show intercalators can alter the equilibrium between BI and BII states [10]. |

| Minor Groove Width | The width of the minor groove, which dictates binder access. | A key determinant for minor-groove binders like DST; wider grooves facilitate 2:1 binding modes [12]. |

| Hydrogen Bonding | Sequence-specific H-bonds between the intercalator and DNA bases. | Critical for selectivity. Engineered polyintercalators like HASDI can form >30 H-bonds with a target 16-bp sequence [9]. |

| Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA) | The surface area of the complex accessible to solvent. | A decrease in SASA upon binding indicates hydrophobic burial, a major energetic driver [12]. |

Energetic Drivers of Binding

The formation of a DNA-intercalator complex is driven by a balance of enthalpic and entropic contributions. Thermodynamic profiling is essential to deconvolute these forces.

Thermodynamic Profiling

Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) studies on minor-groove binders reveal a diverse energetic landscape. Binding can be an enthalpy-driven process, but the entropic contribution (TΔS°) can vary significantly, being large and unfavorable, small, or even large and favorable depending on the specific ligand and DNA sequence [12]. This indicates that the overall free energy of binding (ΔG°) is a net result of compensating factors. A consistent feature is a negative change in heat capacity (ΔC°~p~), which is correlated with the burial of hydrophobic surface area upon complex formation [12].

Free Energy of Binding and the Role of Ensembles

The absolute binding free energy can be calculated from MD simulations using methods like MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA. A critical finding from recent research is that the reproducibility and accuracy of these binding energies depend more on the number of independent simulation replicas than on the length of a single simulation [5].

For instance, for the DNA-Doxorubicin complex, the MM/PBSA binding energy from 25 replicas of 100 ns each was -7.3 ± 2.0 kcal/mol, which aligns well with experimental values (-7.7 to -9.9 kcal/mol). Notably, 25 replicas of just 10 ns each yielded a statistically congruent result of -7.6 ± 2.4 kcal/mol [5]. Bootstrap analysis suggests that 6 replicas of 100 ns or 8 replicas of 10 ns provide a good balance between computational cost and accuracy within 1.0 kcal/mol of experimental values [5].

Table 2: Energetic Components of DNA-Intercalator Binding

| Energetic Component | Description | Contribution to Binding |

|---|---|---|

| Van der Waals Interactions | London dispersion forces between the intercalator and DNA base pairs. | Major favorable contribution; driven by π-π stacking of the planar ligand between base pairs. |

| Electrostatic Interactions | Interactions between charged groups on the ligand and the DNA backbone. | Can be a significant favorable contributor, especially for cationic ligands. |

| Polar Solvation (ΔG~PB~) | Cost of desolvating polar groups upon binding. | Typically unfavorable, as polar groups are stripped of their solvent shell. |

| Non-Polar Solvation (ΔG~SA~) | Favorable energy from the burial of hydrophobic surface area. | Major favorable driver; correlated with negative ΔC°~p~ [12]. |

| Conformational Entropy (-TΔS) | Entropic penalty from reduced flexibility in the ligand and DNA. | Unfavorable; the ligand and DNA binding site lose conformational freedom upon binding. |

| Deformation Energy | Energetic cost of distorting the DNA from its native conformation to accommodate the intercalator. | Unfavorable; must be overcome by favorable interaction energies [5]. |

Experimental Protocols

This section provides detailed methodologies for running and analyzing MD simulations of DNA-intercalator complexes.

Protocol 1: Ensemble MD for Binding Energy Calculation

Application: Accurate and reproducible prediction of binding free energies for a ligand-DNA complex.

Steps:

- System Preparation:

- Obtain the initial structure of the DNA duplex, either from a protein data bank or generate a canonical B-DNA structure using tools like

Avogadro[9]. - Manually dock or orient the intercalator into the proposed binding site, often between two base pairs.

- Place the complex in a simulation box (e.g., a triclinic box) with a minimum distance of 30 Å between the complex and the box edges [9].

- Solvate the system with an explicit water model (e.g., TIP3P [9]).

- Add ions to neutralize the system's charge and to achieve a physiological salt concentration (e.g., 0.156 M NaCl [9]).

- Obtain the initial structure of the DNA duplex, either from a protein data bank or generate a canonical B-DNA structure using tools like

- Equilibration:

- Perform energy minimization (e.g., using the steepest descent algorithm) until the maximum force is below a threshold (e.g., 1000 kJ/mol/nm [9]).

- Equilibrate the system first with position restraints on the heavy atoms of the DNA-ligand complex in the NVT ensemble (constant Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature) for 100 ps to reach the target temperature (e.g., 300 K).

- Continue equilibration in the NPT ensemble (constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature) for 100 ps to reach the target pressure (e.g., 1 atm) without restraints.

- Production Run and Ensemble Setup:

- Launch multiple independent, unrestrained production MD simulations (replicas) starting from the same equilibrated structure but with different random initial velocities.

- Critical: Based on bootstrap analyses, for a system like DNA-Doxorubicin, run at least 8 replicas of 10 ns or 6 replicas of 100 ns for a good balance of efficiency and accuracy [5]. Use a time step of 2 fs.

- Binding Energy Calculation:

- Use the MM/PBSA or MM/GBSA method as implemented in tools like

gmx_MMPBSA[5] [9]. - Perform the calculation on a large number of snapshots (e.g., the last 90% of frames) from each replica trajectory.

- Include corrections for configurational entropy (e.g., using the Interaction Entropy method [9]) and DNA deformation energy [5].

- Report the binding energy as the average and standard deviation across all replicas.

- Use the MM/PBSA or MM/GBSA method as implemented in tools like

Protocol 2: Assessing Binding Mode and Stability

Application: Characterizing the structural dynamics, binding mode, and stability of a DNA-intercalator complex over time.

Steps:

- System Preparation and Simulation: Follow Steps 1-3 from Protocol 1. A single long trajectory (e.g., 150 ns to 1 μs) can be used to explore rare events, though ensembles are still preferred [10] [9].

- Trajectory Analysis:

- Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD): Calculate the RMSD of the DNA backbone and the ligand to assess the overall stability of the complex. A stable complex will show an RMSD that fluctuates around a constant value without a steady increase [9].

- Hydrogen Bond Analysis: Quantify the number and occupancy of hydrogen bonds between the intercalator and the DNA bases. High-occupancy H-bonds indicate specific, stable interactions critical for selectivity [9].

- Root-Mean-Square Fluctuation (RMSF): Compute the RMSF of DNA residues to identify regions of increased flexibility or rigidity induced by intercalator binding.

- Visual Inspection: Regularly visualize the trajectory using molecular visualization software (e.g.,

PyMol) to confirm stable intercalation and observe any structural transitions, such as base flipping [10] [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools and Force Fields for DNA-Intercalator MD Studies

| Tool/Reagent | Type | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | Software Package | A high-performance molecular dynamics package used for simulating the Newtonian equations of motion for systems with hundreds to millions of particles [9]. |

| AMBER99SB | Force Field | An empirical force field for DNA and proteins; provides parameters for bonded and non-bonded interactions between DNA atoms [9]. |

| GAFF (General Amber Force Field) | Force Field | Used to parameterize organic drug-like molecules, such as intercalators, for simulation within the AMBER ecosystem [9]. |

| TIP3P | Water Model | A 3-site model for water molecules that is commonly used in explicit solvent MD simulations of biomolecules [9]. |

| gmx_MMPBSA | Analysis Tool | A tool used to compute binding free energies from MD trajectories using the MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA methods [5] [9]. |

| Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) | Algorithm | A standard method for handling long-range electrostatic interactions in periodic boundary conditions during MD simulations [9]. |

| Avogadro | Software Tool | A molecular editor used for building and energy-minimizing initial DNA and ligand structures [9]. |

Within the broader context of molecular dynamics (MD) simulation analysis for DNA intercalator research, understanding sequence-specific binding is paramount for advancing targeted therapeutic design. DNA-intercalating agents are a class of molecules, including several anticancer drugs, that insert their planar aromatic rings between DNA base pairs, disrupting essential cellular processes like replication and transcription [13] [9]. However, their clinical utility is often hampered by low specificity, leading to widespread side effects [9]. The mechanism of this sequence recognition has been extensively investigated through MD simulations, revealing how intercalator binding is influenced by local DNA structure, dynamics, and chemical environment. This Application Note details the key insights and methodologies from these computational studies, providing structured protocols and data to guide research in selective DNA-targeting drug development.

Key Quantitative Insights from MD Studies

MD simulations provide quantitative metrics—such as binding free energy, hydrogen bond count, and complex stability—to evaluate and compare intercalator binding across different DNA sequences.

Table 1: Key Findings from Sequence-Specific MD Studies of DNA Intercalators

| Intercalator / System | Preferred Sequence(s) | Key Metrics from MD Simulations | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Daunomycin [14] [15] | TC/GA | Classical energy analysis and DFT calculations indicate binding preference. | Congruent with experimental data. |

| HASDI (High-Affinity Selective DNA Intercalator) [9] | 16-bp target from EBNA1 gene | Binding free energy (MM/PBSA): -235.3 ± 7.77 kcal/mol; ~32 hydrogen bonds on average; stable RMSD (~6.5 Å). | Significant energy and stability difference compared to random sequence (KCNH2). |

| HASDI-G2 (Second Generation) [16] | 16-bp target from EBNA1 gene; BCR_ABL1 hybrid; KRAS (G12S) mutant | Improved discrimination over HASDI; even a single-nucleotide mismatch causes significant destabilization and local DNA melting. | Demonstrates ability to discriminate between highly similar sequences, including single-point mutants. |

| Doxorubicin [4] | N/A (Study focused on methodology) | MM/PBSA binding energy (25 replicas of 100 ns): -7.3 ± 2.0 kcal/mol. Entropy and deformation energy corrections were included. | Aligns with experimental range of -7.7 ± 0.3 to -9.9 ± 0.1 kcal/mol. |

Table 2: Energetic and Structural Consequences of Non-Target Binding (HASDI Example) [9]

| Parameter | Target Complex (EBNA1-50nt/HASDI) | Non-Target Complex (KCNH2-50nt/HASDI) |

|---|---|---|

| Binding Free Energy (kcal/mol) | -235.3 ± 7.77 | -193.47 ± 14.09 |

| Average Number of Hydrogen Bonds | ~32 | ~17-19 |

| Complex Stability (RMSD) | Stable, fluctuating around 6.5 Å | Less stable, chaotic changes |

| DNA Structural Integrity | Maintained | Local single-nucleotide melting observed |

Experimental Protocols from MD Studies

Protocol: Ensemble MD Simulations for Binding Energy Calculation

This protocol, derived from the doxorubicin-DNA intercalation study, emphasizes the critical role of ensemble sampling for obtaining reproducible and accurate binding energies [4].

System Setup:

- DNA Structure: Prepare a model of a B-form DNA duplex. For sequence-specific studies, select sequences based on experimental data (e.g., TC/GA for daunomycin [14] [15]).

- Intercalator Parameterization: Generate force field parameters for the intercalator molecule using tools like

ACPYPEwith theGAFFforce field and the Gasteiger charge method [9] [16]. - Solvation and Neutralization: Place the DNA-intercalator complex in a triclinic simulation box, solvate with an explicit solvent model (e.g., TIP3P), and add ions (e.g., NaCl) to a physiological concentration (e.g., 0.156 M). Neutralize the system's total charge [9] [16].

Simulation Execution:

- Energy Minimization: Perform energy minimization using an algorithm like the steepest descent until the system energy is below a threshold (e.g., 1000 kJ/mol/nm) [9].

- Equilibration:

- Production Run: Launch multiple independent simulation replicas (e.g., 25). The study found that 6 replicas of 100 ns or 8 replicas of 10 ns can provide a good balance between accuracy and computational cost [4]. Use a 2 fs time step and conduct simulations for the desired length (e.g., 150 ns [9]).

Trajectory Analysis:

- Binding Energy Calculation: Use the

gmx_MMPBSApackage to compute the binding free energy via the MM/PBSA or MM/GBSA method. It is recommended to use the last 90% of the trajectory frames for analysis and to calculate the entropy contribution using methods like Interaction Entropy (IE) [9]. - Hydrogen Bond Analysis: Calculate the number and persistence of hydrogen bonds between the intercalator and DNA using built-in tools in

GROMACS(e.g.,gmx hbond), with a typical donor-acceptor cutoff distance of 3.0 Å [9]. - Stability and Fluctuation: Analyze the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of the ligand and the root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF) of DNA atoms using

GROMACSutilities (gmx rms,gmx rmsf) orMDAnalysisin Python [17] [9].

- Binding Energy Calculation: Use the

Protocol: Iterative Design of a Selective Polyintercalator

This protocol outlines the iterative in silico development of a sequence-specific polyintercalator, as demonstrated with HASDI and HASDI-G2 [9] [16].

Initial Complex Modeling:

- Target Selection: Identify a target genomic sequence (e.g., a 16-bp segment from the EBNA1 gene).

- DNA Duplex Generation: Create a classical Watson-Crick duplex from the sequence using a molecular editor (e.g., Avogadro).

- Manual Intercalation: Manually intercalate the core aromatic rings (e.g., phenazine or indazole) between the base pairs of the target DNA fragment.

- Geometry Optimization: Perform a brief energy minimization on the complex using the built-in functionality of the molecular editor (e.g., UFF force field, Steepest algorithm) [9] [16].

Molecular Dynamics Evaluation:

- Run an MD simulation of the complex (e.g., 150 ns) following the steps in Protocol 3.1.

- Analyze the stability (RMSD), interaction energy (

gmx_MMPBSA), and number of specific contacts (hydrogen bonds) [9].

Linker Modification and Specificity Screening:

- Modify Linker: Based on the analysis, modify the structure of the aliphatic linker connecting the intercalating rings. The goal is to optimize its ability to form specific hydrogen bonds with hydrogen bond donors or acceptors in the major groove of the target base pair [9].

- Screen Against Non-Target DNA: Test the modified ligand against a non-target DNA sequence (e.g., a random sequence from the KCNH2 gene) [9] or against sequences with single-nucleotide mutations [16].

- Compare Energetics and Stability: The selective agent should show significantly higher binding free energy and a greater number of hydrogen bonds with the target sequence compared to non-target sequences. A drop in energy gain and local DNA melting in non-target complexes are indicators of successful discrimination [9] [16].

Iteration and Extension:

- Repeat steps 2 and 3 until a sufficient level of selectivity is achieved.

- To recognize a longer sequence, additional intercalating rings with their optimized linkers can be attached to extend the structure to the required size [9].

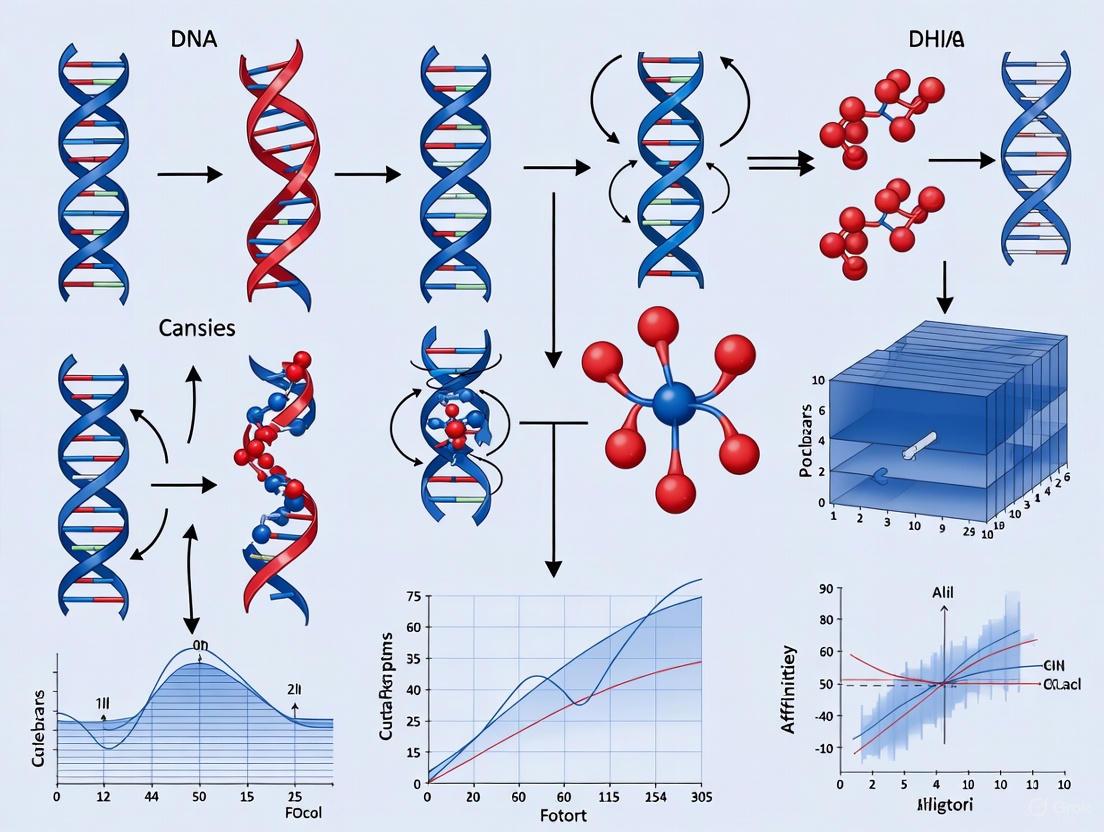

Visualization of Workflows and Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for employing molecular dynamics simulations in the study and design of sequence-specific DNA intercalators, integrating the key protocols outlined above.

Diagram 1: MD Simulation Workflow for Intercalator Research. This chart outlines the iterative process of using MD simulations to study and design selective DNA intercalators, from initial system setup to final analysis and redesign.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Software and Tools for MD Studies of DNA Intercalators

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Application | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Simulation Software | Engine for running MD simulations. | GROMACS [9] [16], NAMD [17]. |

| Force Fields | Defines potential energy functions for atoms. | AMBER99SB (DNA/Proteins) [9] [16], CHARMM (DNA) [17], GAFF (Ligands) [9] [16]. |

| Analysis Tools | Processing simulation trajectories and calculating properties. | Built-in GROMACS utilities (gmx rms, gmx hbond) [9], MDAnalysis (Python) [17], gmx_MMPBSA (binding energies) [9] [16]. |

| Visualization Software | Visual inspection of structures and trajectories. | VMD [17], PyMol [9] [16]. |

| Molecular Editor | Building and modifying initial molecular structures. | Avogadro (for creating DNA duplexes and ligand intercalation) [9] [16]. |

| Water Model | Represents solvent water molecules in the simulation. | TIP3P is commonly used [9] [16]. |

Characterizing DNA Deformation and Conformational Changes Upon Binding

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations are a powerful tool for providing atomistic insight into the binding mechanisms of DNA-intercalating compounds, a process crucial in drug development for conditions like cancer and amyloidosis [18]. However, a significant challenge in the field has been the non-reproducibility of results from single MD simulations, which often deviate from experimental values, undermining the reliability of the predictions [4]. This application note frames these methodologies within the broader context of a thesis on MD simulation analysis for DNA intercalators research. We detail an ensemble-based simulation protocol, validated against experimental data, which overcomes sampling limitations and ensures statistically robust characterization of DNA deformation and binding energetics. The guidelines presented align with recent checklists for improving the reliability and reproducibility of MD simulations [19].

Core Concept: The Ensemble Approach to Reliable Binding Energy Prediction

Traditional reliance on single, long MD simulations for predicting binding energies faces a fundamental sampling problem, where results can vary significantly based on initial conditions [4] [20]. This variability occurs because functional states of biomolecules are separated by rugged free energy landscapes, and single simulations can become kinetically trapped in metastable states [19].

The ensemble approach addresses this by performing multiple independent simulation replicas starting from different, equally plausible initial conditions [4] [20]. Statistical analysis of this ensemble provides a mean value for properties of interest (like binding energy) and, crucially, a measure of its variability. This method demonstrates that reproducibility and accuracy depend more on the number of replicas than on the length of individual simulations [4].

For instance, bootstrap analysis for the DNA-Doxorubicin system revealed that a practical balance of computational efficiency and accuracy (within 1.0 kcal/mol of experiment) is achieved with 6 replicas of 100 ns or 8 replicas of 10 ns [4].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the comparative process between traditional single-run and ensemble MD simulation approaches for characterizing DNA-intercalator binding.

Quantitative Data on Ensemble Simulation Performance

Performance of Ensemble Simulations for DNA-Intercalator Binding

Table 1: Binding energy predictions (kcal/mol) for DNA-Doxorubicin complex using ensemble MD simulations. [4]

| Simulation Protocol | Method | Binding Energy (kcal/mol) | Experimental Range (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 25 replicas of 100 ns | MM/PBSA | -7.3 ± 2.0 | -7.7 ± 0.3 to -9.9 ± 0.1 |

| 25 replicas of 100 ns | MM/GBSA | -8.9 ± 1.6 | -7.7 ± 0.3 to -9.9 ± 0.1 |

| 25 replicas of 10 ns | MM/PBSA | -7.6 ± 2.4 | -7.7 ± 0.3 to -9.9 ± 0.1 |

| 25 replicas of 10 ns | MM/GBSA | -8.3 ± 2.9 | -7.7 ± 0.3 to -9.9 ± 0.1 |

Table 2: Binding energy predictions (kcal/mol) for DNA-Proflavine complex using an ensemble of 25 replicas of 10 ns. [4]

| System | Method | Binding Energy (kcal/mol) | Experimental Range (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA-Proflavine | MM/PBSA | -5.6 ± 1.4 | -5.9 to -7.1 |

| DNA-Proflavine | MM/GBSA | -5.3 ± 2.3 | -5.9 to -7.1 |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Ensemble MD Simulations for Binding Energy Prediction

This protocol is adapted from studies on DNA-intercalator complexes like doxorubicin and proflavine [4].

1. System Setup

- Initial Coordinates: Obtain the starting structure of the DNA-intercalator complex from docking studies or experimental structures (e.g., PDB).

- Solvation: Solvate the complex in a cubic TIP3P water box, ensuring a minimum buffer of 10 Å between the solute and the box edge.

- Neutralization: Add neutralizing ions (e.g., Na⁺, Cl⁻) to mimic physiological ionic strength (~0.15 M).

2. Simulation Parameters

- Force Field: Use appropriate DNA (e.g., parmbsc1) and small molecule (e.g., GAFF) force fields.

- Electrostatics: Employ the Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) method for long-range electrostatics.

- Temperature & Pressure: Maintain system temperature at 300 K using a Langevin thermostat and pressure at 1 atm using a Berendsen or Nosé-Hoover Langevin barostat.

- Constraint Algorithm: Use the SHAKE algorithm to constrain bonds involving hydrogen atoms.

- Integration Time Step: Use a 2 fs time step.

3. Ensemble Production

- Energy Minimization: Minimize the system energy for 10,000 steps to remove bad contacts.

- Equilibration: Equilibrate the system in two phases:

- NVT Ensemble: Heat the system to 300 K over 100 ps with positional restraints on solute atoms.

- NPT Ensemble: Equilibrate for 1 ns with weak restraints, then 1 ns without restraints.

- Generate Replicas: Create N independent simulation replicas (N ≥ 6 for 100 ns or N ≥ 8 for 10 ns) by assigning different random seeds for initial velocities [4].

- Production Run: Run unrestrained MD production for each replica for the desired duration (e.g., 10 ns or 100 ns).

4. Analysis of Binding Energetics

- Trajectory Processing: Ensure trajectories are stable (no large drifts in RMSD) before analysis.

- MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA: Use the Molecular Mechanics/Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area and Generalized Born Surface Area methods to calculate binding free energies. Extract snapshots evenly from the stable portion of each trajectory.

- Entropy & Deformation: Include entropy corrections (e.g., via normal mode analysis) and deformation energy of the DNA upon binding for accurate results [4].

- Statistical Reporting: Calculate and report the mean and standard deviation of the binding energy across all N replicas.

Protocol 2: Experimental Validation via Spectroscopy and Viscosity

This protocol outlines the experimental methods used to validate computational findings, as demonstrated in studies of drugs like tafamidis [18].

1. UV-Visible Spectroscopy for Binding Constant

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a constant concentration of ct-DNA (e.g., 30 µM) in Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4). Prepare a stock solution of the intercalator (e.g., 1 mM) in a suitable solvent like ethanol.

- Titration: Gradually add increasing volumes of the intercalator stock solution to the DNA solution. For a blank, prepare identical solutions without DNA.

- Measurement: Record UV-Vis spectra after each addition in the 200-400 nm range. Monitor the change in absorbance (hypochromism or hyperchromism) at a specific wavelength (e.g., 260 nm).

- Data Analysis: Determine the binding constant (K) using established methods like the Benesi-Hildebrand plot.

2. Fluorescence Quenching for Binding Mode

- Sample Preparation: Prepare DNA and intercalator solutions as above. If the intercalator is fluorescent, perform a direct titration. Alternatively, use a fluorescent probe like Ethidium Bromide (EB) in a competitive assay.

- Direct Titration: Titrate DNA into a fixed concentration of the intercalator. Measure the fluorescence emission spectrum after each addition.

- Competitive Displacement (EB assay):

- Create a DNA-EB complex by mixing them at an optimal ratio.

- Titrate the intercalator into the DNA-EB complex.

- Record the fluorescence quenching. A groove binder will show little effect, while an intercalator will significantly displace EB and quench fluorescence [18].

- Data Analysis: Analyze fluorescence quenching data using the Stern-Volmer equation to determine the quenching constant and infer the binding mode.

3. Viscosity Measurements for Binding Mode Confirmation

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a series of solutions with a fixed concentration of ct-DNA (e.g., 30 µM) and varying concentrations of the intercalator (e.g., 0-15 µM).

- Measurement: Use an Oswald viscometer thermostated at 298 K. Measure the flow time of each solution in triplicate.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the relative specific viscosity as (η/η₀)¹/³, where η and η₀ are the specific viscosities of the DNA-intercalator complex and pure DNA, respectively. Plot this value against the binding ratio ([intercalator]/[DNA]). A significant increase in viscosity suggests intercalation, while a slight change or decrease suggests groove binding [18].

The following diagram illustrates the key steps and decision points in the statistical analysis of ensemble simulation data.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key research reagent solutions and materials for studying DNA-intercalator binding. [4] [18]

| Item | Function / Description | Example Usage |

|---|---|---|

| Calf Thymus DNA (ct-DNA) | High-molecular-weight double-stranded DNA used as a standard model for in vitro binding studies. | Primary substrate for spectroscopic and viscosity experiments to determine binding constant and mode [18]. |

| Tris-HCl Buffer (pH 7.4) | Provides a stable, physiologically relevant pH environment for biochemical experiments. | Standard buffer for preparing DNA and drug solutions in spectroscopic and thermodynamic studies [18]. |

| Ethidium Bromide (EB) | A classic fluorescent intercalator probe used in competitive displacement assays. | Used to determine if a new compound binds via intercalation (displaces EB) or groove binding (no displacement) [18]. |

| Molecular Dynamics Software | Software suites (e.g., AMBER, GROMACS, NAMD) for running all-atom simulations. | Used to perform energy minimization, equilibration, and production MD simulations of the DNA-drug complex [4]. |

| MM/PBSA & MM/GBSA Scripts | Computational tools integrated within MD packages for endpoint free energy calculation. | Used on snapshots from MD trajectories to predict the absolute binding free energy of the intercalator [4]. |

| Force Fields (e.g., parmbsc1, GAFF) | Parameter sets defining potential energy functions for DNA and organic molecules in MD simulations. | Essential for accurate simulation of DNA dynamics and drug-DNA interactions; parmbsc1 corrects DNA backbone inaccuracies [4]. |

Practical Implementation: MD Simulation Protocols for DNA-Intercalator Systems

Force Field Selection and Parameterization for Nucleic Acid-Ligand Complexes

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation serves as a critical theoretical tool for elucidating the structure-function relationships of nucleic acids and their complexes with ligands, a research area of paramount importance in drug development and molecular biology. The reliability of these simulations, however, is fundamentally contingent upon the accurate representation of atomic interactions through a well-validated and balanced force field. This application note provides a structured overview of available force fields, summarizes their performance through quantitative benchmarks, and outlines detailed protocols for their application in the study of nucleic acid-ligand complexes, with a specific focus on DNA intercalators within the context of anticancer drug research.

Several all-atom force fields are commonly employed for the simulation of nucleic acids and their complexes. The selection of a force field requires careful consideration of the specific system and properties of interest. The table below summarizes key force fields, their characteristics, and primary applications.

Table 1: Key Force Fields for Nucleic Acid Simulations

| Force Field | Class | Key Features & Improvements | Recommended Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| AMBER (parmbsc1, OL15) [21] | Classical, Non-polarizable | Refinements of α/γ torsional terms; improved description of DNA backbone [21]. | Standard B-DNA simulations; general nucleic acid-ligand systems. |

| CHARMM27/CHARMM36 [22] [23] | Classical, Non-polarizable | Optimized to correct A/B-DNA equilibrium; balanced for protein-nucleic acid complexes [22] [23]. | Protein-DNA/RNA complexes; simulations requiring a balanced protein-nucleic acid force field. |

| Drude2017 [21] | Polarizable | Incorporates electronic polarization via Drude oscillators; superior for ion channel stability and Hoogsteen hydrogen bonds [21]. | G-quadruplexes; systems where polarization effects are critical (e.g., ion-nucleic acid interactions). |

| AMOEBA [21] | Polarizable | Uses a multipole approach for electrostatics; includes polarization and charge penetration effects. | Systems requiring high-fidelity electrostatics; can be computationally demanding. |

| BMS [22] | Classical, Non-polarizable | Derived from CHARMM22 and AMBER; backbone parameters from quantum mechanics [22]. | DNA duplexes (historical context). |

Quantitative Benchmarking of Force Field Performance

Selecting a force field requires an understanding of its quantitative performance. The following table summarizes key metrics from systematic benchmarks, particularly for non-canonical DNA structures like G-quadruplexes (GQs), which are sensitive to force field inaccuracies.

Table 2: Benchmarking Force Field Performance on DNA G-Quadruplexes (GQs) [21]

| Force Field | Backbone RMSD (Å) | Channel Ion Stability | Hoogsteen H-Bond Fidelity | Overall Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| parmbsc0 | Moderate (~1.5-2.5) | Poor (rapid ion escape) | Moderate (bifurcated H-bonds observed) | Not recommended for GQs |

| parmbsc1 | Moderate (~1.5-2.5) | Poor to Moderate | Moderate (bifurcated H-bonds observed) | Not recommended for GQs |

| OL15 | Low (< 2.0) | Poor (rapid ion escape) | Moderate (bifurcated H-bonds observed) | Not recommended for GQs |

| AMOEBA | High (> 2.5) | Poor (ion escape observed) | Not Specified | Not recommended for GQs |

| Drude2017 | Lowest (< 2.0) | Excellent (ions stable in channel) | Best (preserves canonical bonds) | Recommended for GQs |

The data indicates that while non-polarizable force fields like OL15 can maintain stable overall structures, they fail to properly stabilize key interactions, such as ions within G-quadruplex channels. The explicit inclusion of electronic polarization in the Drude2017 force field is critical for accurately modeling such sensitive electrostatic environments [21].

For standard B-DNA, earlier comparisons of CHARMM22 and CHARMM27 revealed that CHARMM22 over-stabilized the A-form of DNA, an imbalance that was corrected in the CHARMM27 force field, enabling accurate simulation of the B-form in solution [22].

Experimental Protocols for DNA-Ligand Binding Studies

Protocol: Ensemble MD for Binding Energy Calculation

Accurate prediction of binding free energies for DNA-intercalator complexes can be achieved through ensemble MD simulations, which prioritize multiple replicas over single long simulations [5].

1. System Setup:

- Initial Coordinates: Obtain the DNA-ligand complex structure from crystallography, NMR, or molecular docking.

- Solvation: Place the complex in a triclinic water box (e.g., TIP3P water model) with a minimum 10 Å distance between the solute and box edge [9].

- Neutralization: Add monovalent ions (e.g., Na⁺, Cl⁻) to achieve a physiological concentration (e.g., 0.156 M) and neutralize the system net charge [9].

2. Simulation Parameters:

- Force Fields: Use AMBER99SB or CHARMM36 for DNA. Parameterize the ligand with GAFF (Generalized Amber Force Field) using tools like ACPYPE, assigning charges with the Gasteiger method [9].

- Electrostatics: Treat long-range interactions with the Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) method [22] [9]. A real-space cutoff of 9-12 Å is typical.

- Temperature & Pressure: Maintain constant temperature (300 K) and pressure (1 atm) using coupling algorithms like Berendsen or Parrinello-Rahman during equilibration [9].

3. Production Run and Analysis:

- Simulation Ensemble: Execute multiple independent simulation replicas (e.g., 25 replicas). Research shows that 6 replicas of 100 ns or 8 replicas of 10 ns can provide a good balance between accuracy and computational cost [5].

- Binding Energy Calculation: Use the MM/PBSA or MM/GBSA methods via tools like

gmx_MMPBSA. The dielectric constants are typically set to 2 (internal) and 80 (external). Include entropy contributions, calculated via the Interaction Entropy (IE) method [9]. - Structural Analysis: Monitor stability using root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of the DNA backbone and ligand. Analyze specific interactions, such as hydrogen bonding (average number and occupancy) and intercalation stability [9].

The following workflow diagram illustrates this multi-replica approach:

Protocol: Iterative Design of a Selective DNA Intercalator

Molecular dynamics simulations can also be used iteratively to design DNA-binding agents with high sequence specificity, as demonstrated with the HASDI (High-Affinity Selective DNA Intercalator) molecule [9].

1. Initial Docking and Simulation:

- Target Sequence: Select a target DNA sequence (e.g., from the EBNA1 gene).

- Ligand Docking: Manually intercalate the core ligand rings (e.g., phenazine) between base pairs and minimize the energy using a molecular editor (e.g., Avogadro) with the UFF force field [9].

2. Iterative Optimization Cycle:

- Run MD Simulation: Simulate the DNA/ligand complex (e.g., 150 ns) using a chosen force field (e.g., AMBER99SB) [9].

- Analyze Interactions: Critically analyze the simulation trajectory. Identify potential hydrogen bond donors or acceptors on the nucleobases in the major groove that are not engaged in Watson-Crick pairing.

- Modify Linker: Chemically modify the aliphatic linkers connecting the intercalator rings to include functional groups capable of forming specific hydrogen bonds with the identified base-pair features.

- Energy Minimization: Perform a short energy minimization session on the modified complex to relieve steric clashes.

- Repeat: Iterate the cycle of simulation, analysis, and linker modification until a sufficient level of selectivity and binding affinity is achieved computationally [9].

3. Validation Against Non-Target DNA:

- Control Simulation: Simulate the final designed molecule (e.g., HASDI) in complex with a non-target DNA sequence (e.g., from the KCNH2 gene).

- Compare Energetics and Stability: Calculate and compare the binding free energy, number of hydrogen bonds, and structural stability (RMSD) between the target and non-target complexes. A selective agent will show significantly more favorable binding energy and a stable complex only with the target sequence [9].

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Simulating Nucleic Acid-Ligand Complexes

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS/NAMD | High-performance MD simulation packages. | Simulating the dynamics of a DNA-intercalator complex in explicit solvent [9]. |

| AMBER/CHARMM | MD software suites with associated force fields. | Parameterizing and simulating nucleic acid systems with specific, optimized force fields [22] [21]. |

| GAFF (Generalized Amber Force Field) | Provides parameters for organic molecules, including ligands. | Parameterizing a novel intercalator (e.g., HASDI, doxorubicin) for simulation with AMBER force fields [5] [9]. |

| MM/PBSA & MM/GBSA | End-state methods for calculating binding free energies from MD trajectories. | Calculating the binding affinity of an intercalator to its target DNA sequence [5] [9]. |

| Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) | Algorithm for accurate treatment of long-range electrostatic interactions. | Essential for maintaining structural integrity of nucleic acids during simulation [22] [23] [9]. |

| Avogadro | Molecular editor and visualizer. | Building and manually docking an intercalator into a DNA duplex [9]. |

The selection and application of an appropriate force field is a foundational step in the molecular dynamics analysis of nucleic acid-ligand complexes. For standard B-DNA systems, refined classical force fields like CHARMM27/36 or the AMBER parmbsc1/OL15 variants are reliable choices. However, for complexes where accurate electrostatics are paramount—such as those involving G-quadruplexes, metal ions, or highly polarized interfaces—polarizable force fields like Drude2017 demonstrate superior performance. The presented protocols for ensemble binding energy calculation and iterative ligand design provide a robust framework for researchers to generate reproducible and quantitatively accurate data, thereby accelerating the rational design of nucleic acid-targeted therapeutics.

Solvation Models and Boundary Conditions in DNA Simulations

Accurate molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of DNA and its interactions with ligands, such as intercalators, are fundamental to modern drug development and biochemical research. The realistic modeling of the solvent environment is a cornerstone of such simulations, directly influencing the predictive power of calculated properties like binding affinities, conformational dynamics, and mechanism of action. Researchers must navigate a critical choice between two primary solvation approaches: explicit solvent models, which treat individual solvent molecules as discrete entities, and implicit solvent models, which represent the solvent as a continuous dielectric medium [24]. For highly charged biomolecules like DNA, this decision is paramount, as the ion atmosphere governs structure, dynamics, and interactions with ligands [25]. This application note, framed within a broader thesis on MD simulation analysis for DNA intercalators, provides a detailed comparison of these models and outlines standardized protocols to guide researchers and drug development professionals in selecting and implementing the most appropriate and computationally efficient methodologies.

The choice of solvation model dictates the balance between computational cost and physical accuracy in a simulation. Implicit solvent models, such as the Generalized Born (GB) model used in MM/GBSA (Molecular Mechanics/Generalized Born Surface Area) calculations, offer significant computational advantages [4] [24]. They provide lower computational costs and faster conformational sampling by eliminating the viscous drag of explicit solvent molecules. These models estimate solvation energy as a perturbation to the gas-phase Hamiltonian, incorporating both electrostatic processes and non-electrostatic contributions like cavity formation [26] [24]. However, a major limitation is their inability to capture specific, localized intermolecular interactions, such as hydrogen bonding and dispersion forces, which are critical for systems with extensive solvent interactions [26] [25]. This can lead to significant inaccuracies; for instance, in calculating the reduction potential of the carbonate radical, implicit solvation methods predicted only one-third of the measured value [26].

In contrast, explicit solvent models include individual solvent molecules, allowing for the direct simulation of key interactions like hydrogen bonding and charge transfer [26]. While this approach is computationally expensive, it is often essential for accuracy. The development of hybrid models, such as the explicit ions/implicit water generalized Born model, seeks a middle ground. This model treats ions explicitly while keeping water implicit, enabling a more accurate description of the ion atmosphere around nucleic acids without the full cost of explicit solvent [25]. This is particularly valuable for studying multivalent ions, where mean-field implicit models fail to capture ion-ion correlations and ion desolvation effects [25].

Table 1: Comparison of Implicit and Explicit Solvation Models for DNA Simulations

| Feature | Implicit Solvent Models | Explicit Solvent Models |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Cost | Lower; faster sampling and better parallel scaling [24] | High; prohibitive for large systems or long timescales [24] [25] |

| Treatment of Solvent | Dielectric continuum [24] | Discrete molecules (e.g., water, ions) [26] |

| Key Advantages | Efficient free energy estimates, faster conformational search [24] | Captures specific interactions (H-bonding, dispersion) [26] |

| Key Limitations | Misses specific intermolecular interactions [26] | High computational cost; slowed conformational transitions [24] |

| Best-Suited Applications | High-throughput binding affinity screening (MM/GBSA/PBSA) [4], rapid conformational sampling [24] | Studying specific solvent interactions, ion atmosphere effects, and redox properties [26] [25] |

Quantitative Data and Performance Benchmarks

Recent studies provide quantitative benchmarks for the performance of different simulation protocols, particularly for predicting DNA-ligand binding energies. Ensemble MD simulations have emerged as a powerful strategy to achieve reproducible and accurate results. A key finding is that for DNA-intercalator complexes, the reproducibility and accuracy of binding energies depend more on the number of simulation replicas than on the length of individual simulations [4] [5].

For the Doxorubicin-DNA complex, using 25 replicas of 100 ns simulations yielded MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA binding energies of -7.3 ± 2.0 kcal/mol and -8.9 ± 1.6 kcal/mol, respectively. Crucially, these values were closely reproduced using 25 shorter replicas of 10 ns, which gave values of -7.6 ± 2.4 kcal/mol (MM/PBSA) and -8.3 ± 2.9 kcal/mol (MM/GBSA). Both results align well with the experimental range of -7.7 ± 0.3 to -9.9 ± 0.1 kcal/mol [4] [5]. Bootstrap analysis further revealed that a balance between efficiency and accuracy (within 1.0 kcal/mol of experiment) can be achieved with 6 replicas of 100 ns or 8 replicas of 10 ns [4].

The performance of implicit solvation is highly system-dependent. In DNA intercalation studies, MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA methods can perform well when averaged over an ensemble [4]. However, for systems with strong, specific solvent interactions—such as the aqueous carbonate radical—implicit models alone can fail dramatically, underscoring the necessity of explicit solvation for such cases [26].

Table 2: Performance Benchmarks for DNA-Intercalator Binding Energy Prediction [4] [5]

| System | Simulation Protocol | Binding Energy (MM/PBSA) | Binding Energy (MM/GBSA) | Experimental Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doxorubicin-DNA | 25 replicas of 100 ns | -7.3 ± 2.0 kcal/mol | -8.9 ± 1.6 kcal/mol | -7.7 to -9.9 kcal/mol |

| Doxorubicin-DNA | 25 replicas of 10 ns | -7.6 ± 2.4 kcal/mol | -8.3 ± 2.9 kcal/mol | -7.7 to -9.9 kcal/mol |

| Proflavine-DNA | 25 replicas of 10 ns | -5.6 ± 1.4 kcal/mol | -5.3 ± 2.3 kcal/mol | -5.9 to -7.1 kcal/mol |

| Recommended for <1.0 kcal/mol error | 6 replicas of 100 ns or 8 replicas of 10 ns | - | - | - |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Ensemble MD for DNA-Intercalator Binding Affinity

This protocol is designed for the accurate prediction of binding energies using an ensemble approach, based on the methodology validated in recent literature [4] [5].

System Preparation:

- Obtain the initial structure of the DNA-intercalator complex. A reliable starting configuration is crucial.

- Solvate the complex in a suitable explicit solvent box (e.g., TIP3P water) and add ions to neutralize the system and achieve the desired physiological ionic concentration.

Equilibration:

- Energy minimize the system to remove bad contacts.

- Perform equilibration MD simulations with positional restraints on the DNA and ligand heavy atoms, gradually releasing the restraints while bringing the system to the target temperature (e.g., 310 K) and pressure (1 atm).

Production Ensemble Simulation:

- Generate multiple independent simulation replicas (e.g., 8-25) from different initial atomic velocities.

- Run production MD simulations for each replica. Based on bootstrap analysis, a simulation length of 10-100 ns per replica can be sufficient [4].

- Ensure proper sampling by saving trajectory frames at regular intervals.

Binding Energy Calculation (MM/GBSA or MM/PBSA):

- Extract snapshots evenly from the combined trajectories of all replicas.

- For each snapshot, calculate the binding free energy using the MM/GBSA or MM/PBSA method. This involves separating the complex into DNA and ligand components and computing the gas-phase energy, solvation free energy, and often entropy corrections.

- Include corrections for entropy and deformation energy as required [4].

- Average the results over all snapshots from all replicas to obtain the final binding energy and its standard deviation.

Protocol 2: Explicit Solvation for Systems with Strong Solvent Interactions

This protocol should be employed when simulating systems where specific solvent-solute interactions (e.g., strong hydrogen bonding) are critical, such as in electron transfer reactions or with kosmotropic ions [26].

System Setup with Explicit Solvent:

- Start with the solute (e.g., DNA or ion) in a gas-phase optimized geometry.

- Manually place explicit solvent molecules (e.g., water) around the solute to ensure they form key intermolecular interactions, such as hydrogen bonds. Avoid geometries where solvent molecules primarily interact with themselves [26].

- For charged systems, create multiple replicates (e.g., 3) with the same number of solvent molecules but varying their positions and angles to sample the conformational space [26].

- Employ a hybrid solvation approach by activating an implicit solvation model (e.g., SMD) in addition to the explicit molecules to account for bulk solvent effects [26].

Geometry Optimization and Validation:

- Optimize the geometry of each replicate using Density Functional Theory (DFT) or the chosen level of theory.

- Confirm that all optimized structures are at a minimum energy level by verifying the absence of imaginary vibrational frequencies.

- Ensure the solute maintains strong interactions with the solvent cage in each replicate.

Energy Calculation and Averaging:

- Calculate the single-point energy for the optimized geometry of each replicate.

- Compute the target property (e.g., reduction potential) for each replicate.

- Report the final value as the average of the replicates, with the standard deviation representing the error.

Visualization of Workflows and Relationships

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Reagents for DNA Simulation Studies

| Research Reagent | Function and Application Note |

|---|---|

| MM/GBSA & MM/PBSA | End-point methods to calculate binding free energies from MD trajectories. Ideal for high-throughput screening of DNA intercalators when used with an ensemble simulation approach [4]. |

| Generalized Born (GB) Model | An implicit solvent model that approximates the electrostatic solvation energy. Provides a good balance of speed and accuracy for biomolecular simulations but may fail for systems with strong, specific solvent interactions [26] [24]. |

| SMD Solvation Model | A continuum solvation model that estimates solvation energy based on solute electron density interacting with a dielectric continuum. Useful for initial screening but may require augmentation with explicit solvent for accuracy [26]. |

| Explicit Ions/Implicit Water GB | A hybrid model that treats ions as explicit particles while keeping water as an implicit dielectric. Essential for accurately simulating the ion atmosphere around highly charged DNA and RNA, especially with multivalent ions [25]. |

| Ensemble MD Replicas | Multiple independent simulations starting from different initial conditions. Proven to be more critical than long simulation times for achieving reproducible and accurate binding energies for DNA-intercalator complexes [4] [5]. |

Molecular mechanics Poisson-Boltzmann surface area (MM/PBSA) and molecular mechanics generalized Born surface area (MM/GBSA) are established computational approaches for estimating binding free energies in biomolecular systems [27] [28]. As end-point methods, they offer a balance between computational efficiency and theoretical rigor, positioning them between fast docking algorithms and computationally intensive alchemical free energy methods [27]. These methods have found broad application in drug discovery and molecular recognition studies, including the investigation of DNA-intercalator complexes central to anticancer drug development [4] [5].

In the context of DNA intercalator research, accurate binding free energy predictions provide crucial insights for rational drug design. MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA enable researchers to quantify how strongly potential drug molecules bind to DNA, helping prioritize candidates for further experimental validation [29]. This application note details standardized protocols for applying these methods to DNA-intercalator systems, supported by recent methodological advances and validation studies.

Theoretical Background

Fundamental Equations

The MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA methods estimate the binding free energy (ΔGbind) using the following thermodynamic cycle and master equation [27] [28]:

ΔGbind = ΔEMM + ΔGsolv - TΔS

Where:

- ΔEMM represents the gas-phase molecular mechanical energy change upon binding, comprising internal (bond, angle, torsion), electrostatic, and van der Waals components

- ΔGsolv denotes the change in solvation free energy upon binding

- -TΔS accounts for the conformational entropy change at absolute temperature T

The solvation term is further decomposed into polar and non-polar contributions: ΔGsolv = ΔGpolar + ΔGnon-polar

In MM/PBSA, the polar solvation component (ΔGpolar) is computed by solving the Poisson-Boltzmann equation, while MM/GBSA employs the Generalized Born approximation [28]. The non-polar component (ΔGnon-polar) is typically estimated from solvent-accessible surface area (SASA) in both methods [27].

DNA Intercalation and Energetics

DNA intercalators are small molecules, typically containing planar aromatic systems, that insert between DNA base pairs, often unwinding and elongating the DNA duplex [29]. This binding mode is employed by several anticancer drugs (e.g., Doxorubicin, Proflavine) that interfere with DNA replication and transcription [4] [29]. Accurate prediction of intercalator binding energies helps optimize their therapeutic properties while minimizing off-target effects.

Computational Protocols

Ensemble MD Simulations for DNA-Intercalator Systems

Recent studies demonstrate that ensemble MD simulations significantly improve the reproducibility and accuracy of binding energy predictions for DNA-intercalator complexes [4] [5]. The following protocol outlines the recommended approach:

System Preparation

- Obtain DNA-intercalator complex structure from crystallography, NMR, or docking

- Parameterize DNA using appropriate force fields (e.g., AMBER DNA force fields)

- Parameterize ligands using GAFF with AM1-BCC partial charges

- Solvate the complex in explicit water boxes with neutralizing ions

Ensemble Simulation Setup

- Generate multiple independent starting structures (6-25 replicas) through random velocity assignment [4] [5]

- For each replica, perform energy minimization and gradual heating to target temperature

- Equilibrate systems with positional restraints on DNA and ligand heavy atoms

Production Simulations

- Conduct unrestrained MD simulations for each replica

- Recommended simulation lengths: 8 replicas of 10 ns or 6 replicas of 100 ns per system [4] [5]

- Maintain constant temperature and pressure using standard thermostats and barostats

- Save trajectory frames at regular intervals (e.g., every 100 ps) for subsequent analysis

MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA Calculations

Single-Trajectory Approach

For DNA-intercalator systems, the single-trajectory approach is typically employed [4]:

- Use snapshots from the complex simulation only

- Generate receptor (DNA) and ligand (intercalator) trajectories by extracting relevant coordinates from complex trajectories

- This approach assumes minimal conformational change in unbound states and improves statistical precision through error cancellation [27]

Free Energy Calculation

For each trajectory snapshot:

- Remove solvent molecules and counterions

- Calculate molecular mechanics energy (ΔEMM) using the same force field as in MD simulations

- Compute polar solvation free energy (ΔGpolar) using:

- PB solver for MM/PBSA

- GB model for MM/GBSA

- Estimate non-polar solvation free energy (ΔGnon-polar) from SASA using linear relation: ΔGnon-polar = γ × SASA + b

Entropy and Deformation Corrections

For DNA-intercalator systems, include:

- Entropy estimation: Use normal mode or quasi-harmonic analysis on selected snapshots [4]

- Deformation energy: Account for DNA conformational changes upon intercalator binding [4] [5]

Performance Assessment and Validation

Quantitative Comparison for DNA-Intercalator Systems

Table 1: MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA Binding Energy Predictions for DNA-Intercalator Complexes

| Intercalator | Method | Simulation Protocol | Predicted ΔG (kcal/mol) | Experimental ΔG (kcal/mol) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doxorubicin | MM/PBSA | 25×100 ns replicas | -7.3 ± 2.0 | -7.7 to -9.9 | [4] |

| Doxorubicin | MM/GBSA | 25×100 ns replicas | -8.9 ± 1.6 | -7.7 to -9.9 | [4] |

| Doxorubicin | MM/PBSA | 25×10 ns replicas | -7.6 ± 2.4 | -7.7 to -9.9 | [4] |

| Doxorubicin | MM/GBSA | 25×10 ns replicas | -8.3 ± 2.9 | -7.7 to -9.9 | [4] |

| Proflavine | MM/PBSA | 25×10 ns replicas | -5.6 ± 1.4 | -5.9 to -7.1 | [4] [5] |

| Proflavine | MM/GBSA | 25×10 ns replicas | -5.3 ± 2.3 | -5.9 to -7.1 | [4] [5] |

Key Findings for DNA-Intercalator Studies

- Ensemble vs. single simulations: Ensemble approaches with multiple replicas provide more reproducible results than single long simulations [4] [5]

- Simulation length trade-offs: Multiple shorter replicas (10 ns) often outperform fewer longer simulations in computational efficiency while maintaining accuracy [4]

- Entropy importance: Conformational entropy and deformation energy corrections significantly improve agreement with experimental data for DNA-intercalator systems [4]

- Method selection: MM/GBSA generally shows similar or slightly better performance than MM/PBSA for DNA complexes, with lower computational cost [4]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for DNA-Intercalator MM/PBSA Studies

| Tool/Software | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| AMBER | MD simulation and free energy calculations | Includes specialized DNA force fields; MMPBSA.py for automated calculations [30] |

| GROMACS | MD simulation engine | High-performance MD with MM/PBSA compatibility via g_mmpbsa |

| CHARMM-GUI | Membrane system preparation | Useful for membrane protein-DNA intercalator studies [30] |

| PyMOL | Molecular visualization | Structure analysis and figure generation |

| CPPTRAJ | Trajectory analysis | Processing MD trajectories for MM/PBSA calculations [30] |

| MDAnalysis | Python trajectory analysis | Custom analysis scripts for DNA-intercalator systems |

Advanced Applications and Methodological Extensions

Membrane Protein-DNA Intercalator Systems

Recent extensions enable MM/PBSA application to membrane protein systems relevant to DNA-intercalator research [30]:

High-Throughput Screening of DNA Intercalators

MM/GBSA implementations in tools like Flare enable virtual screening of intercalator libraries [31]:

- Single-conformation MM/GBSA for rapid ranking of compound series

- Dynamics-based MM/GBSA for refined binding affinity estimates

- Integration with docking workflows for structure-based drug design

Troubleshooting and Best Practices

Common Issues and Solutions

- Poor convergence: Implement ensemble simulations with multiple replicas rather than extending single simulation length [4]

- Entropy overestimation: Use truncated normal mode analysis focusing on relevant degrees of freedom [30]

- Membrane system inaccuracies: Employ recently developed implicit membrane models with automated parameterization [30]

- DNA deformation effects: Include deformation energy corrections for intercalator binding [4]

Validation Recommendations

- Compare predictions with experimental binding data for known DNA intercalators

- Validate force field selection through comparison with experimental structural data

- Perform sensitivity analysis on key parameters (e.g., dielectric constant, entropy estimation method)

- Use bootstrap analysis to determine optimal number of replicas (≥6 for 100 ns, ≥8 for 10 ns) [4]

MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA methods provide valuable tools for investigating DNA-intercalator binding energetics when applied with appropriate protocols. The ensemble simulation approach with multiple replicas significantly enhances reproducibility and accuracy for these systems. Recent methodological extensions, including membrane modeling capabilities and improved entropy treatments, continue to expand the applicability of these methods in DNA-targeted drug discovery research.

Advanced Sampling Techniques for Enhanced Conformational Sampling