Advanced Feature Selection Methods for High-Dimensional Oncology Data: From Foundations to Clinical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive guide to feature selection techniques tailored for high-dimensional oncology data, such as gene expression, DNA methylation, and multi-omics datasets.

Advanced Feature Selection Methods for High-Dimensional Oncology Data: From Foundations to Clinical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to feature selection techniques tailored for high-dimensional oncology data, such as gene expression, DNA methylation, and multi-omics datasets. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational challenges of data sparsity and the curse of dimensionality, explores a suite of methodological approaches from filter to advanced hybrid and AI-driven methods, addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization strategies to mitigate overfitting and enhance scalability, and concludes with robust validation and comparative frameworks to ensure biological relevance and clinical translatability. The content synthesizes the latest research to empower the development of precise, interpretable, and robust models for cancer classification and biomarker discovery.

Navigating the High-Dimensional Landscape: Core Challenges and Concepts in Oncology Data

Understanding the 'Curse of Dimensionality' in Genomics and Transcriptomics

FAQs

What is the 'Curse of Dimensionality' in the context of genomics? In genomics, the "Curse of Dimensionality" (COD) refers to the statistical and analytical problems that arise when working with data where the number of features (e.g., genes, variants) is vastly larger than the number of samples (e.g., patients, cells) [1]. Whole-genome sequencing and transcriptomics technologies routinely generate data with tens of thousands of genes for only hundreds or thousands of samples, creating high-dimensional data that complicates robust analysis [1] [2].

Why is it a significant problem in cancer research? The Curse of Dimensionality is particularly problematic in cancer research for several reasons. It can obscure the true differences between cancer subtypes, making it difficult to cluster patients accurately for diagnosis or treatment selection [3]. Furthermore, the accumulation of technical noise across thousands of genes can lead to inconsistent statistical results and impair the ability of machine learning models to identify genuine biological signals, such as interacting genetic variants that contribute to complex diseases like cancer [2] [4].

What are the common types of COD encountered in genomic data analysis? Research identifies several specific types of COD that affect single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) and other genomic data [2]:

- COD1: Loss of Closeness: Distances between samples (like Euclidean distance) become inflated and unreliable, impairing clustering.

- COD2: Inconsistency of Statistics: Key statistics, such as PCA contribution rates, become unstable and untrustworthy.

- COD3: Inconsistency of Principal Components: The principal components themselves can be distorted by technical factors like sequencing depth rather than biology.

How can I tell if my dataset is suffering from the Curse of Dimensionality? Potential signs include hierarchical clustering dendrograms with very long "legs" (distances) between clusters, principal components that are strongly correlated with technical variables (e.g., sequencing depth), and statistics like Silhouette scores that behave inconsistently as you analyze more features [2].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor Clustering of Patient Samples

Symptoms: Unsupervised clustering methods (e.g., hierarchical clustering, k-means) fail to group known cancer subtypes accurately. The resulting clusters do not align with established clinical or molecular classifications.

Solutions:

- Apply Feature Selection: Prior to clustering, use feature selection to reduce dimensionality. Do not rely solely on genes with the highest standard deviation, as this has been shown to be suboptimal [3]. Instead, consider bimodality measures like the dip-test or the bimodality index (BI), which can help identify genes with expression patterns suggestive of distinct subgroups [3].

- Utilize Specialized Algorithms: For datasets with millions of features (e.g., genomic variants), use machine learning methods designed for high-dimensional data, such as VariantSpark's Random Forest [4]. These algorithms are better equipped to handle the "wide" data and can identify interacting sets of variants associated with a phenotype.

Table: Comparison of Feature Selection Methods for Clustering Cancer Subtypes [3]

| Method Category | Example Methods | Key Idea | Reported Performance Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variability-based | Standard Deviation (SD), Interquartile Range (IQR) | Selects genes with the most variable expression across samples. | Commonly used but did not perform well in a comparative study. |

| Bimodality-based | Dip-test, Bimodality Index (BI), Bimodality Coefficient (BC) | Selects genes whose expression distribution suggests two or more distinct groups. | The dip-test (selecting 1000 genes) was overall a good performer. |

| Correlation-based | VRS, Hellwig | Searches for large sets of genes that are highly correlated across samples. | Performance varies; can be effective. |

Problem: Technical Noise is Obscuring Biological Signals

Symptoms: Principal Component Analysis (PCA) results are dominated by technical artifacts (e.g., batch effects, sequencing depth) rather than biological conditions of interest. Analysis results are not reproducible.

Solutions:

- Leverage Mutual Information: Use a method like Component Selection using Mutual Information (CSUMI) to systematically determine which principal components (PCs) are actually related to your biological covariates (e.g., tissue type, disease status) [5]. This moves beyond simply selecting the first few PCs and helps you focus on the most biologically relevant dimensions.

- Employ Noise Reduction: For single-cell RNA-seq data with unique molecular identifiers (UMIs), use a noise-reduction method like RECODE (Resolution of the Curse of Dimensionality) [2]. RECODE is designed to resolve COD by separating technical noise from true biological expression without reducing the number of genes, allowing for recovery of signals even from lowly expressed genes.

Problem: Inefficient or Failed Machine Learning Analysis

Symptoms: Standard machine learning libraries (e.g., Spark MLlib) run out of memory or fail to complete analysis on genomic-scale data. The model cannot identify known disease-associated variants.

Solutions:

- Scale with Optimized Algorithms: Use tools specifically engineered for genomic data dimensions. For example, VariantSpark implements a novel parallelization of Random Forest on Apache Spark that can handle thousands of samples with millions of features, a task where standard implementations fail [4].

- Validate with Synthetic Data: Test your analysis pipeline on a synthetic dataset with a known ground truth. For instance, create a synthetic phenotype where the outcome is based on a known, non-additive combination of a few genomic loci. A robust tool should be able to identify these key features in the correct order of importance [4].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Evaluating Feature Selection Methods for Subtype Identification

This protocol is based on a study that compared 13 feature selection methods on RNA-seq data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) [3].

- Data Acquisition and Pre-processing:

- Obtain raw RNA-seq count data (e.g., from the TCGA database).

- Perform initial filtration, between-sample normalization, and a variance-stabilizing transformation on the raw count data.

- Application of Feature Selection:

- Apply the various feature selection methods (e.g., dip-test, highest SD, BI) to the pre-processed data.

- For each method, select a pre-defined number of top-ranked genes (e.g., 1000 genes).

- Clustering and Evaluation:

- Perform hierarchical clustering (e.g., using Ward's linkage and Euclidean distance) on the dataset that includes only the selected genes.

- Compare the resulting binary sample partition to a known gold standard partition (e.g., established cancer subtypes) using the Adjusted Rand Index (ARI) to quantify clustering accuracy.

Protocol: Using CSUMI to Interpret Principal Components

This protocol describes how to use the CSUMI method to link Principal Components (PCs) to biological and technical covariates [5].

- Perform PCA: Run a standard Principal Component Analysis on your high-dimensional gene expression dataset.

- Prepare Covariate Data: Compile metadata for your samples, including both biological (e.g., tissue type, patient age) and technical (e.g., sequencing batch, RIN score) covariates.

- Calculate Mutual Information:

- For each principal component (PC) and each covariate, calculate the mutual information (MI). MI measures the amount of information shared between the PC and the covariate.

- The CSUMI statistic is calculated, which represents the percentage of information in a covariate that is contained in a given PC.

- Interpret Results:

- Identify which covariates have high CSUMI values for each PC. This reveals whether a PC captures biological signal of interest or technical noise.

- Use this information to select the most relevant PCs for downstream analysis and visualization, rather than defaulting to only the first two PCs.

Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

Feature Selection Workflow for Clustering

CSUMI Analysis for Interpreting PCs

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Key Computational Tools for Addressing Dimensionality

| Tool / Method Name | Type | Primary Function | Key Application in Genomics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dip-test [3] | Feature Selection Filter | Identifies genes with multimodal expression distributions. | Selecting features for cancer subtype identification via clustering. |

| RECODE [2] | Noise Reduction Algorithm | Resolves the Curse of Dimensionality by reducing technical noise in high-dim data. | Preprocessing scRNA-seq data with UMIs to recover true expression values. |

| CSUMI [5] | Dimensionality Analysis Statistic | Uses mutual information to link Principal Components to biological/technical covariates. | Interpreting PCA results and selecting relevant PCs for further analysis. |

| VariantSpark [4] | Machine Learning Library | Scalable Random Forest implementation for ultra-high-dimensional data. | Genome-wide association studies on WGS data; identifying interacting variants. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Data Sparsity in High-Dimensional Oncology Datasets

Problem: My predictive model for drug sensitivity is performing poorly. The dataset, built from cancer cell line screens, has many molecular features but most have zero values for any given sample.

Explanation: Data sparsity occurs when a large percentage of data points in a dataset are missing or zero [6]. In oncology, this is common with genomic features—a cell line will have mutations in only a small subset of genes. This sparsity can cause models to ignore informative but sparse features, increase storage and computational time, and lead to overfitting, where a model performs well on training data but fails to generalize to new data [7] [8].

Solution: Apply techniques to transform or reduce the sparse feature space.

- Action 1: Apply Dimensionality Reduction. Use methods like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to project the original high-dimensional, sparse data onto a lower-dimensional, dense space of principal components [7].

from sklearn.decomposition import PCA

- Action 2: Utilize Feature Hashing. Bin a large number of categorical features (e.g., gene IDs) into a predetermined number of dimensions, effectively reducing feature space sparsity [7].

- Action 3: Employ Robust Algorithms. Consider algorithms less sensitive to sparsity. For example, an entropy-weighted k-means algorithm can weight sparse but informative features more effectively than standard models [8]. The Lasso algorithm (L1 regularization) is also useful as it performs feature selection by driving some feature coefficients to zero [8].

Guide 2: Mitigating the Impact of Noisy Data in Molecular Profiling

Problem: My model for predicting breast cancer metastasis is inaccurate and unstable. I suspect noise from technical variability in the lab equipment and inconsistent sample processing is to blame.

Explanation: Noisy data contains errors, outliers, or inconsistencies that obscure underlying patterns [9]. In molecular data, noise can stem from measurement errors, sensor malfunctions, or inherent biological variability [10]. This noise can lead to misinterpretation of trends, reduced predictive accuracy, and poor generalization [10].

Solution: Implement a pipeline to identify and clean noisy data.

- Action 1: Identify Noise with Visualization and Statistics.

- Action 2: Apply Data Cleaning and Smoothing.

- Action 3: Use Automated Anomaly Detection. For large datasets, employ algorithms like Isolation Forests or DBSCAN to automatically detect and flag anomalous samples [10].

Guide 3: Preventing Model Overfitting in Prognostic Classifier Development

Problem: The prognostic classifier I developed for patient stratification shows 95% accuracy on the training data but only 60% on the validation set.

Explanation: Overfitting occurs when a model learns the detail and noise in the training data to the extent that it negatively impacts its performance on new data [11]. This is a critical risk in high-dimensional, low-sample-size (HDLSS) settings common in oncology, where you may have thousands of gene expression features but only hundreds of patient samples [12]. An overfitted model will fail to generalize to real-world clinical data.

Solution: Use regularization, cross-validation, and adjust model architecture.

- Action 1: Implement Regularization. Add a penalty to the model's loss function to discourage complexity.

- L1 (Lasso) Regularization: Adds a penalty equal to the absolute value of coefficients. This can drive some feature coefficients to zero, performing feature selection [11].

- L2 (Ridge) Regularization: Adds a penalty equal to the square of the magnitude of coefficients. This shrinks coefficients but does not zero them out [11].

- Action 2: Tune Key Hyperparameters. As identified in empirical studies, adjusting the following can significantly reduce overfitting [11]:

- Increase learning rate, decay, and batch size.

- Decrease momentum and number of training epochs.

- Action 3: Apply Rigorous Validation. Never rely on training set (apparent) accuracy [12]. Always use a held-out test set or, even better, k-fold cross-validation to get a realistic estimate of your model's performance on unseen data [9] [12].

The following workflow summarizes a robust experimental process that incorporates the solutions to these key challenges:

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between data sparsity and noisy data? A1: Data sparsity refers to a dataset where most of the values are zero or missing, which is a characteristic of the data structure common in high-dimensional biology [6]. In contrast, noisy data contains errors, outliers, or inconsistencies that deviate from the true values, often introduced during data collection or measurement [10]. Sparsity is about the absence of data, while noise is about incorrect data.

Q2: For drug sensitivity prediction, should I use a data-driven or knowledge-driven feature selection approach? A2: The best approach depends on the drug's mechanism. One systematic study found that for drugs targeting specific genes and pathways, small feature sets selected using prior knowledge of the drug's targets (a knowledge-driven approach) were highly predictive and more interpretable [13]. For drugs affecting general cellular mechanisms, models with wider, data-driven feature sets (e.g., using stability selection) often performed better [13].

Q3: I have a low-dimensional dataset (p < n). Can I still ignore the risk of overfitting? A3: No. Overfitting is not exclusive to high-dimensional data. Simulation studies have demonstrated that overfitting can be a serious problem even when the number of candidate variables (p) is much smaller than the number of observations (n), especially if the relationship between the outcome and predictors is not strong. You should always use a separate test set or cross-validation to evaluate model accuracy [12].

Q4: Are there any feature selection methods designed specifically for ultra high-dimensional, low-sample-size data? A4: Yes, novel methods are being developed to address this challenge. For example, Deep Feature Screening (DeepFS) is a two-step, non-parametric approach that uses deep neural networks to extract a low-dimensional data representation and then performs feature screening on the original input space. This method is model-free, can capture non-linear relationships, and is effective for data with a very small number of samples [14].

Experimental Protocol & Reagents

Detailed Methodology: Evaluating Hyperparameter Impact on Overfitting

This protocol is based on an empirical study of overfitting in deep learning models for breast cancer metastasis prediction using an Electronic Health Records (EHR) dataset [11].

1. Objective: To systematically quantify how each of 11 key hyperparameters influences overfitting and model performance in a Feedforward Neural Network (FNN).

2. Experimental Setup:

- Dataset: EHR data concerning breast cancer metastasis.

- Model: Deep Feedforward Neural Network (FNN).

- Evaluation Metric: Area Under the Curve (AUC) for both training and test sets. The gap between train and test AUC is a measure of overfitting.

3. Procedure:

- Grid Search: Conduct a comprehensive grid search over the 11 hyperparameters.

- Define Ranges: For each hyperparameter, define a wide range of values to test (see table below).

- Train and Evaluate: For each combination of hyperparameters in the grid, train the FNN and record the training and test AUC.

- Analyze Correlation: Calculate the correlation between each hyperparameter value and the degree of overfitting (measured by the train-test AUC gap).

4. Key Hyperparameters Analyzed [11]:

| Hyperparameter | Role & Function | Impact on Overfitting (Based on Findings) |

|---|---|---|

| Learning Rate | Controls the step size during weight updates. | Negative Correlation: Increasing it can reduce overfitting. |

| Decay | Iteration-based decay that reduces the learning rate over time. | Negative Correlation: Increasing it can reduce overfitting. |

| Batch Size | Number of samples per gradient update. | Negative Correlation: Increasing it can reduce overfitting. |

| L2 Regularization | Penalizes large weights (weight decay). | Negative Correlation: Increasing it can reduce overfitting. |

| L1 Regularization | Promotes sparsity by driving some weights to zero. | Positive Correlation: Increasing it can increase overfitting. |

| Momentum | Accelerates convergence by considering past gradients. | Positive Correlation: Increasing it can increase overfitting. |

| Training Epochs | Number of complete passes through the training data. | Positive Correlation: Increasing it drastically increases overfitting. |

| Dropout Rate | Randomly drops neurons during training to prevent co-adaptation. | Designed to reduce overfitting; optimal value must be found. |

| Number of Hidden Layers | Controls the depth and complexity of the network. | Too many layers can increase overfitting risk. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in the Context of Feature Selection & Modeling |

|---|---|

| Elastic Net | A hybrid linear regression model that combines both L1 and L2 regularization penalties. It is particularly useful for feature selection in scenarios where features are correlated, common in biological data [13]. |

| Stability Selection | A resampling-based method used in conjunction with feature selectors (like Lasso). It improves the stability and reliability of the selected features by looking at features that are consistently chosen across different data subsamples [13]. |

| Random Forest | An ensemble learning algorithm that can be used for both regression and classification. It provides a built-in measure of feature importance, which can be used for data-driven feature selection [13]. |

| Supervised Autoencoder | A type of neural network that learns to compress data (encode) and then reconstruct it (decode), with the addition of a task-specific loss (e.g., prediction error). It can be used for non-linear feature extraction and dimensionality reduction [14]. |

| Multivariate Rank Distance Correlation | A distribution-free statistical measure used in methods like DeepFS to test the dependence between a high-dimensional feature and a low-dimensional representation. It is powerful for detecting non-linear relationships during feature screening [14]. |

The Critical Role of Feature Selection in Biomarker Discovery and Cancer Subtype Identification

FAQs: Feature Selection in High-Dimensional Oncology Data

Q1: Why is feature selection critical for biomarker discovery from high-dimensional omics data? Feature selection (FS) is a preprocessing technique that identifies the most relevant molecular features while discarding irrelevant and redundant ones. In oncology, high-dimensional data often has thousands of features (e.g., genes, proteins) but only a small number of patient samples. FS mitigates the "curse of dimensionality," reducing model complexity, decreasing training time, and enhancing the generalization capability of models to prevent overfitting. Crucially, it helps identify the most biologically informative features, which can represent candidate therapeutic targets, molecular mechanisms of disease, or biomarkers for diagnosis or surveillance of a particular cancer [15] [16] [17].

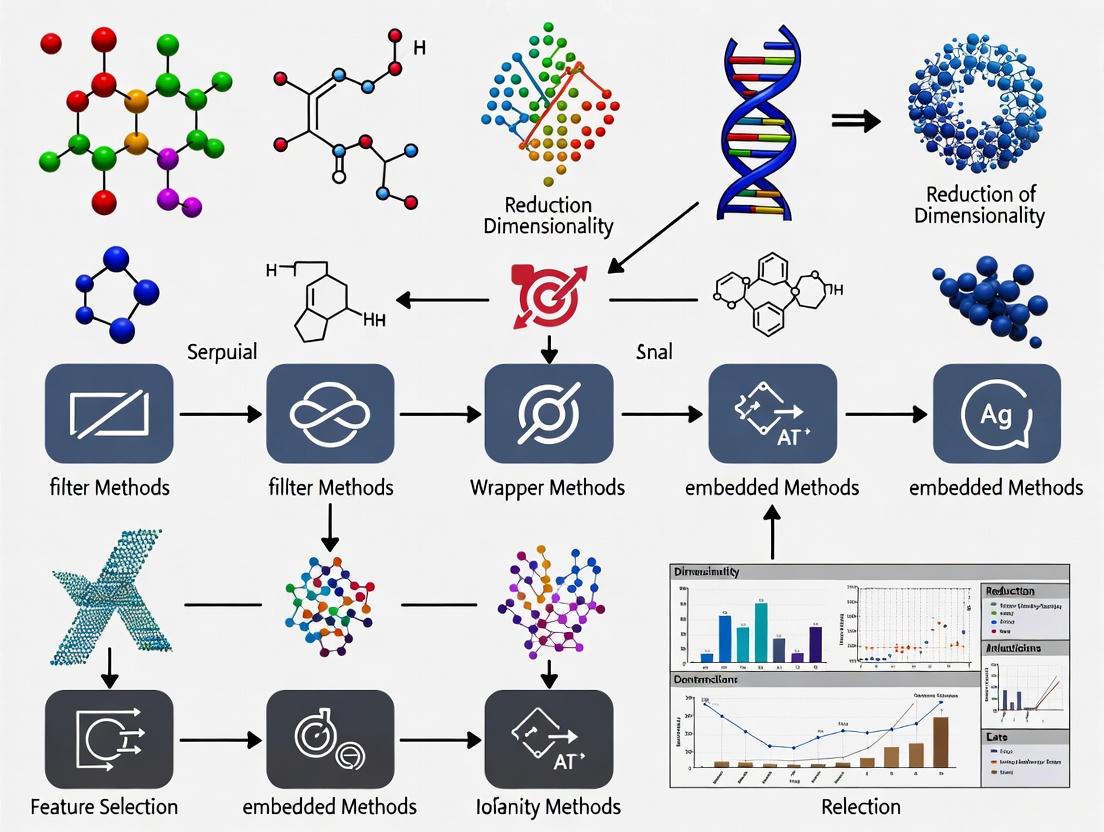

Q2: What are the main categories of feature selection methods? Feature selection methods are broadly categorized into three types [15] [17]:

- Filter Methods: These methods select features based on statistical measures (like correlation or mutual information) without involving any machine learning algorithm. They are computationally efficient and scalable but may ignore feature dependencies.

- Wrapper Methods: These methods use a specific machine learning model to evaluate the quality of feature subsets. They often yield high-performing feature sets but are computationally intensive, especially with high-dimensional data.

- Embedded Methods: These methods integrate the feature selection process directly into the model training algorithm. Examples include feature importance from Random Forests or regularization techniques like Lasso. They are computationally efficient and model-specific.

Q3: What are common challenges when performing feature selection on genomic data? Researchers often face several challenges [17] [18]:

- High Dimensionality and Small Sample Sizes: The number of features (e.g., SNPs, genes) vastly exceeds the number of samples, increasing the risk of overfitting.

- Feature Redundancy: Genomic features are often highly correlated due to linkage disequilibrium, where nearby genetic variants are inherited together.

- Feature Interaction: The effect of a feature on a phenotype may depend on interactions with other features (epistasis), which simple univariate methods can miss.

- Technical Noise: Data can contain artifacts from experimental protocols or instrumentation that must be corrected during pre-processing to avoid spurious findings [16].

Q4: How can I validate the biological relevance of selected features? After computational selection, putative biomarkers should be validated through [19]:

- Pathway Analysis: Mapping the selected molecules (e.g., genes, proteins) to known biological pathways to understand their functional context and interactions.

- Independent Cohort Validation: Evaluating the performance of the selected feature panel on a larger, independent set of patient samples to ensure robustness.

- Comparison to Known Biomarkers: Assessing how the new features relate to existing clinical biomarkers.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Model Overfitting Despite Applying Feature Selection

Problem: Your classification model performs well on training data but poorly on unseen validation data, even after reducing the number of features.

Solution:

- Cause: The feature selection process itself may have overfitted the training data, or the selected feature set is too large for the number of available samples.

- Actions:

- Nested Cross-Validation: Implement a nested cross-validation scheme where the feature selection is performed within each training fold of the outer loop. This prevents information from the validation set from leaking into the feature selection process [17].

- Apply Regularization: Use embedded FS methods like Lasso (L1 regularization) that inherently perform feature selection while penalizing model complexity [15].

- Aggregate Feature Importance: Run the feature selection method multiple times (e.g., on bootstrapped samples of the data) and aggregate the results to create a more stable list of robust features [16].

- Simplify the Model: Reduce the complexity of the final classifier and ensure the number of selected features is significantly smaller than the number of samples [18].

Issue 2: Inconsistent Feature Selection Across Repeated Experiments

Problem: The list of selected features varies greatly when the analysis is repeated on different splits of the same dataset.

Solution:

- Cause: High instability can occur when many features are weakly correlated with the outcome or highly correlated with each other (redundant).

- Actions:

- Increase Sample Size: If possible, increase the number of biological replicates to improve the statistical power.

- Use Robust FS Methods: Employ methods specifically designed for stability or ensemble FS techniques that combine results from multiple algorithms [20].

- Address Redundancy: Use FS methods that explicitly account for feature redundancy, for instance, by selecting one representative feature from a cluster of highly correlated features [17].

- Leverage Hybrid Techniques: Implement hybrid methods like the Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) combined with the robust Mood median test, which is beneficial for reducing the impact of outliers in non-normal or skewed data [21].

Issue 3: Integrating Multi-Omics Data for Subtype Identification

Problem: Difficulty in integrating heterogeneous data types (e.g., transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) to discover coherent cancer subtypes.

Solution:

- Cause: Different omics layers have distinct scales, distributions, and levels of noise, making integration non-trivial.

- Actions:

- Apply Data-Specific Normalization: Normalize each omics dataset individually to correct for technical variation before integration [19] [16].

- Use Multi-Omics Integration Tools: Employ computational frameworks designed for multi-omics integration, such as:

- Adopt Advanced Deep Learning: Explore transformer-based deep learning models, such as those used in a 2025 HCC study, which used recursive feature selection in conjunction with a transformer model to identify key molecules like leucine, isoleucine, and SERPINA1 more effectively than sequential methods [19].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: A Basic Workflow for Biomarker Discovery Using Filter-Based Feature Selection

This protocol outlines a standard pipeline for identifying potential biomarkers from gene expression data.

1. Data Pre-processing & Quality Control:

- Input: Raw gene expression matrix (e.g., from RNA-seq or microarrays).

- Steps:

- Normalization: Apply appropriate normalization (e.g., TPM for RNA-seq, RMA for microarrays).

- Filtering: Remove genes with low expression or low variance across samples.

- Quality Control: Check for outliers and batch effects. Use principal component analysis (PCA) to visualize sample groupings.

2. Feature Selection:

- Method: A combination of univariate statistical filters.

- Steps:

- Significance Testing: Perform a statistical test (e.g., t-test for two groups, ANOVA for multiple groups) between sample classes (e.g., tumor vs. normal) for each gene.

- Multiple Testing Correction: Apply a correction method (e.g., Benjamini-Hochberg) to control the False Discovery Rate (FDR). Retain genes with an adjusted p-value < 0.05.

- Effect Size Calculation: Calculate the fold-change in expression for each significant gene to prioritize biomarkers with large biological effects.

3. Model Building & Validation:

- Classifier Training: Train a classifier (e.g., Support Vector Machine, Random Forest) using only the selected features.

- Performance Assessment: Evaluate the model using cross-validation or an independent test set. Report metrics like accuracy, AUC, and F1-score.

4. Biological Validation:

- Pathway Enrichment: Use tools like Enrichr or GSEA to determine if the selected genes are enriched in known cancer-related pathways.

- Literature Mining: Cross-reference the top biomarkers with existing scientific literature to support their biological plausibility.

Protocol 2: Hybrid Evolutionary Algorithm for Robust Feature Selection

This protocol uses advanced optimization techniques to find a compact, discriminative set of features [20] [18].

1. Data Preparation:

- Follow the pre-processing steps from Protocol 1.

2. Feature Selection with a Hybrid Algorithm:

- Method: Two-phase Mutation Grey Wolf Optimization (TMGWO) or similar (e.g., BBPSO, ISSA).

- Steps:

- Initialization: Represent a potential feature subset as a binary vector (1=feature included, 0=excluded). Initialize a population of such vectors.

- Fitness Evaluation: Evaluate each feature subset using a fitness function that balances classification accuracy (e.g., from a KNN classifier) and the number of features selected.

- Population Update: Apply the TMGWO algorithm to update the population. The "two-phase mutation" helps balance exploration of new feature combinations and exploitation of promising ones to avoid local optima.

- Termination: Repeat for a fixed number of generations or until convergence. The best feature subset is the one with the optimal fitness score.

3. Validation:

- Use nested cross-validation to fairly assess the performance of the model built on features selected by the hybrid algorithm.

- Compare against other FS methods to demonstrate improvement.

Performance Comparison of Feature Selection Methods

Table 1: Comparative performance of different classifiers with and without hybrid feature selection (FS) on cancer datasets (adapted from [18]). Accuracy values are illustrative.

| Dataset | Classifier | Without FS (Accuracy %) | With Hybrid FS (Accuracy %) | Number of Selected Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast Cancer (Wisconsin) | SVM | 92.5 | 96.0 | 4 |

| Breast Cancer (Wisconsin) | Random Forest | 90.1 | 94.2 | 5 |

| Differentiated Thyroid Cancer | KNN | 85.8 | 91.5 | 7 |

| Sonar | Logistic Regression | 78.3 | 86.7 | 10 |

Key Biomarkers and Pathways in Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC)

Table 2: Key molecules and pathways identified through multi-omics feature selection in a 2025 HCC study [19].

| Molecule / Pathway | Type | Biological Significance / Function |

|---|---|---|

| Leucine / Isoleucine | Metabolite | Branched-chain amino acids associated with liver function and metabolism. |

| SERPINA1 | Protein | Involved in LXR/RXR Activation and Acute Phase Response signaling pathways. |

| LXR/RXR Activation | Pathway | Regulates lipid metabolism and inflammation; linked to cancer progression. |

| Acute Phase Response | Pathway | A rapid inflammatory response; chronic activation is a hallmark of cancer microenvironment. |

Visualization: Workflows and Relationships

FSS Workflow

FS Methods Taxonomy

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential materials and tools for feature selection experiments in oncology research.

| Item / Tool Name | Type | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| LC-MS/MS System | Instrumentation | Used for untargeted and targeted mass spectrometric analysis of serum/tissue samples to generate proteomics, metabolomics, and lipidomics data [19]. |

| Compound Discoverer | Software | Processes raw LC-MS/MS data for peak alignment, detection, and annotation of analytes in metabolomics and lipidomics studies [19]. |

| ColorBrewer | Tool | Provides a classic set of color palettes (qualitative, sequential, diverging) for creating accessible and effective data visualizations [22] [23]. |

| Coblis / Viz Palette | Tool | Color blindness simulators used to check that color choices in charts and diagrams are distinguishable by users with color vision deficiencies [22] [23]. |

| Multi-Omics Integration Tools (e.g., MOFA+, MOGONET) | Software/Algorithm | Computational frameworks designed to harmonize and find patterns across heterogeneous data types (e.g., transcriptomics, proteomics) for a unified analysis [19]. |

| Hybrid Evolutionary Algorithms (e.g., TMGWO, BBPSO) | Algorithm | Advanced optimization techniques used to search for an optimal subset of features by balancing model accuracy and feature set size [20] [18]. |

Core Concepts and Data Types

This section outlines the fundamental data types used in modern high-dimensional oncology research, explaining their biological significance and role in multi-omics integration.

Gene Expression Data: This data type captures the transcriptome—the complete set of RNA transcripts in a cell at a specific time. It reflects active genes and provides a dynamic view of cellular function. In oncology, analyzing gene expression helps identify differentially expressed genes in tumors, uncover novel cancer subtypes through clustering, and understand disease mechanisms. High-throughput technologies like RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) generate this data, though the high dimensionality (thousands of genes) necessitates robust feature selection to focus on biologically relevant information. [3] [24]

DNA Methylation Data: DNA methylation is an epigenetic mechanism involving the addition of a methyl group to DNA, typically to cytosine bases in CpG islands, which can regulate gene expression without altering the DNA sequence. This data type provides insights into the epigenome, revealing how gene expression is modulated. In complex diseases like cancer, aberrant DNA methylation patterns can silence tumor suppressor genes or activate oncogenes. Integrating this data with gene expression helps elucidate regulatory mechanisms and identify epigenetic drivers of disease. [25] [26]

Multi-Omic Integration: Multi-omics integration harmonizes data from various molecular layers—including genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and epigenomics—to provide a comprehensive, systems-level view of biological processes. This approach is particularly powerful for studying multifactorial diseases like cancer, cardiovascular, and neurodegenerative disorders. It addresses the limitations of single-omics analyses by uncovering interactions and patterns across different biological layers, thereby enhancing biomarker discovery, improving patient stratification, and guiding targeted therapies. [27] [26]

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

Q1: Why is feature selection critical when working with high-dimensional gene expression data, and what are the pitfalls of common selection methods?

Feature selection is essential because high-dimensional genomic data often contains many genes that are uninformative for the specific biological question. Using all features can introduce noise, reduce clustering performance, and obscure meaningful patterns. Analysis should be based on a carefully selected set of features rather than all measured genes. [3]

- Troubleshooting Guide:

- Problem: Clustering results are poor or do not align with known biological subtypes.

- Potential Cause: Use of uninformative genes or genes affected by technical artifacts or non-biological factors (e.g., age, diet).

- Solution: Apply a robust feature selection method prior to clustering. Avoid relying solely on common but suboptimal methods like selecting genes with the highest standard deviation (SD). Consider using a method based on the dip-test statistic, which has been shown to be a good overall choice for identifying genes with multimodal distributions indicative of underlying subtypes. [3]

Q2: What are the primary challenges when integrating multiple omics data types, and how can they be addressed?

Integrating multi-omics data presents significant challenges due to the heterogeneity of the data. Key issues include: [27] [28] [26]

- Lack of Pre-processing Standards: Each omics data type has a unique structure, statistical distribution, measurement error, and batch effects.

- Data Heterogeneity: Different measurement units, scales, and noise profiles make data harmonization difficult.

- Bioinformatics Expertise: Handling and analyzing large, heterogeneous data matrices requires cross-disciplinary skills.

Choice of Integration Method: Selecting the most appropriate algorithm from the many available (e.g., MOFA, DIABLO, SNF) can be challenging.

Troubleshooting Guide:

- Problem: Integrated data yields misleading conclusions or poor model performance.

- Potential Causes:

- Cause 1: Inadequate data standardization and harmonization.

- Solution: Preprocess your data rigorously. This includes normalizing for differences in sample size and concentration, converting to a common scale, removing technical biases and batch effects, and filtering outliers. Use domain-specific ontologies and standardized formats to align data from different sources. Always document the preprocessing steps used. [28]

- Cause 2: Use of an inappropriate integration method for the biological question and data structure.

- Solution: Choose an integration method aligned with your goal. Consider whether your analysis is supervised (uses a known phenotype) or unsupervised. For example, DIABLO is a supervised method for biomarker discovery, while MOFA is an unsupervised method for discovering latent factors of variation. [26]

Q3: How can we improve the identification of causal genes in complex traits beyond standard transcriptome-wide association studies (TWAS)?

Standard TWAS methods often rely solely on gene expression and overlook other regulatory mechanisms, such as DNA methylation and splicing, which contribute to the genetic basis of complex traits and diseases. [25]

- Troubleshooting Guide:

- Problem: TWAS fails to identify or validate causal genes for a complex trait.

- Solution: Adopt a multi-omics integration approach. Develop models that incorporate complementary data types like gene expression, DNA methylation, and splicing data. Simulations and analyses of complex traits have shown that integrated methods achieve higher statistical power and improve the accuracy of causal gene identification compared to single-omics approaches. [25]

Experimental Protocols for Key Analyses

Protocol 1: Identifying Cancer Subtypes via Feature Selection and Clustering

This protocol outlines a workflow for detecting novel disease subtypes from high-dimensional RNA-seq data, a common task in oncology research. [3]

- Data Acquisition: Obtain raw gene-level count data from a source like The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database.

- Pre-processing: Perform initial filtration, between-sample normalization, and apply a variance-stabilizing transformation to the raw count data.

- Feature Selection: Apply a feature selection method to identify genes informative for subtype discrimination. The dip-test statistic is recommended as a robust choice. Alternative methods include bimodality measures (Bimodality Index, Bimodality Coefficient) or variability scores (Interquartile Range).

- Clustering: Perform hierarchical clustering using Ward's linkage and Euclidean distance on the selected gene set. Alternatively, k-means clustering (with k=2 for binary subtypes) can be used.

- Validation: Compare the computed cluster partition against a known gold standard partition (e.g., established clinical subtypes) using the Adjusted Rand Index (ARI) to evaluate performance.

The workflow for this analysis can be visualized as follows:

Protocol 2: Integrative Bioinformatics Analysis for Key Gene Discovery

This protocol describes a method to identify key genes and signaling pathways by integrating gene expression data with a specific biological process, such as ferroptosis in obesity. [29]

- Data Collection:

- Download RNA-Seq data from a public repository like the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO).

- Obtain a relevant gene set (e.g., Ferroptosis-Related Genes (FRGs) from the FerrDb database).

- Screening of Candidate Genes:

- Use Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) to identify modules of highly correlated genes associated with the trait (e.g., obesity).

- Identify Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs) between case and control samples.

- Cross-reference the WGCNA module genes, DEGs, and the FRGs to obtain a candidate gene list for further analysis.

- Key Gene Identification:

- Construct a Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) network using the candidate genes.

- Analyze the PPI network to identify hub nodes (key genes) with high connectivity, such as STAT3, IL6, PTGS2, and VEGFA.

- Advanced Integrative Analysis:

- Perform immune infiltration analysis to explore relationships between key genes and immune cell populations.

- Construct miRNA-mRNA and Transcription Factor (TF)-mRNA regulatory networks to understand the post-transcriptional and transcriptional regulation of the key genes.

The logical flow of this integrative screening process is shown below:

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogs key computational tools and resources essential for conducting multi-omics analyses in oncology research.

| Tool/Resource Name | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| mixOmics [28] | Data integration | R package for multivariate analysis and integration of multi-omics datasets. |

| INTEGRATE [28] | Data integration | Python-based tool for multi-omics data integration. |

| MOFA [26] | Data integration | Unsupervised Bayesian method to infer latent factors from multi-omics data. |

| DIABLO [26] | Data integration | Supervised method for biomarker discovery and multi-omics integration. |

| SNF [26] | Data integration | Network-based fusion of multiple data types into a single sample-similarity network. |

| SIMO [30] | Spatial integration | Probabilistic alignment for spatial integration of multi-omics single-cell data. |

| DAVID [31] | Functional annotation | Tool for understanding biological meaning behind large gene lists. |

| MSigDB [31] | Gene set repository | Database of annotated gene sets for enrichment analysis. |

| WebGestalt [31] | Gene set analysis | Toolkit for functional genomic, proteomic, and genetic study data. |

| TCGA [3] [26] | Data repository | Publicly available cancer genomics dataset for robust analysis. |

A Practical Toolkit: Filter, Wrapper, Embedded, and Advanced Hybrid Methods

Why are filter methods a crucial first step in high-dimensional oncology data analysis?

High-dimensional oncology data, such as genomics datasets with thousands of genes for a few hundred patients, presents the "curse of dimensionality" [32] [33]. In this context, where the number of features (p) far exceeds the number of observations (n), data becomes sparse, and models face a high risk of overfitting—learning noise instead of true biological patterns [32] [34]. Filter methods provide a fast and computationally efficient pre-screening step to mitigate these issues by drastically reducing the number of features before applying more complex models [34] [33]. This initial reduction helps to improve model performance, reduce training time, and enhance the interpretability of results, which is critical for identifying biologically relevant biomarkers [32] [35].

How do filter methods work?

Filter methods assess the relevance of features by looking at their intrinsic statistical properties, without involving a machine learning algorithm [34]. They operate by scoring each feature based on its statistical relationship with the target variable (e.g., drug sensitivity). Features are then ranked by their scores, and the top-k features are selected for the next stage of analysis. The general workflow is:

The core of this process relies on statistical measures. The table below summarizes common ones used in bioinformatics:

| Statistical Measure | Data Type (Feature → Target) | Brief Description & Application |

|---|---|---|

| t-test / ANOVA [33] | Continuous → Categorical | Tests if the mean values of a continuous feature are significantly different across groups (e.g., drug-sensitive vs. resistant cell lines). |

| Mutual Information (MI) [35] | Any → Any | Measures the mutual dependence between two variables. Captures non-linear relationships, useful for complex genomic interactions [35]. |

| Chi-square Test [33] | Categorical → Categorical | Assesses the independence between two categorical variables (e.g., mutation presence/absence and treatment outcome). |

| Correlation Coefficient [33] | Continuous → Continuous | Measures the linear relationship between a feature and a continuous target (e.g., gene expression and IC50 value). |

A sample experimental protocol

The following protocol is inspired by methodologies used in systematic assessments of feature selection for drug sensitivity prediction [35].

Objective: To identify a panel of transcriptomic features predictive of anti-cancer drug response using a filter method for pre-screening.

1. Data Preparation

- Dataset: Use a publicly available resource like the Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer (GDSC) or NCI-DREAM Challenge [36] [35].

- Input Features: Gather molecular data from cancer cell lines. This typically includes:

- Target Variable: Obtain a quantitative measure of drug response, such as IC50 or AUC (Area Under the dose-response curve), for a specific compound of interest [35].

2. Feature Pre-screening with a Filter Method

- Choose a Statistical Measure: For a continuous target like IC50, use the correlation coefficient. For a categorical target (e.g., sensitive/resistant, binarized from IC50), use a t-test or Mutual Information.

- Apply the Filter: Calculate the statistical score for every feature (gene) in the dataset against the drug response.

- Rank and Select: Rank all features based on their scores in descending order (higher score = more relevant). Select the top k features (e.g., 500-1000) for the next step. This number can be based on a pre-defined p-value threshold or a fixed percentage.

3. Model Building and Validation

- Use Reduced Feature Set: Train a predictive model (e.g., Elastic Net, Random Forest, or SVR) using only the pre-screened features [35].

- Validate Performance: Evaluate the model's performance using robust cross-validation techniques. The primary metric could be the correlation between observed and predicted drug response or the Relative Root Mean Squared Error (RelRMSE) on a held-out test set [35].

- Compare to Baseline: Compare the performance against a baseline model that uses all genome-wide features or features selected by other methods (e.g., wrapper or knowledge-driven) [35].

4. Interpretation and Biological Validation

- Analyze Selected Features: The final list of features from the model (which may be further reduced by the model's own selection, like in Lasso) constitutes the candidate predictive biomarkers.

- Pathway Enrichment Analysis: Use bioinformatics tools to investigate if the selected genes are enriched in specific biological pathways, which can provide mechanistic insights into the drug's action and resistance [33].

- External Validation: The ultimate test is to validate the biomarker panel on an independent patient cohort or clinical trial data.

The scientist's toolkit: Research reagents & solutions

| Item / Solution | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| GDSC / NCI-DREAM Dataset | Provides the foundational data linking molecular profiles of cancer cell lines to quantitative drug response measurements for model training and testing [36] [35]. |

| Statistical Software (R, Python) | The computational environment for performing statistical calculations (t-test, MI), data manipulation, and implementation of the feature selection workflow [35]. |

| Scikit-learn (Python Library) | Offers built-in functions for various statistical tests, feature selection algorithms, and machine learning models, streamlining the entire analysis pipeline [34]. |

| Bioinformatics Databases (e.g., KEGG, GO) | Used for the biological interpretation of the final selected feature set via pathway and gene ontology enrichment analysis [33]. |

Troubleshooting common issues

Problem: My final model is overfitting, even after pre-screening.

- Cause: The pre-screened feature set might still be too large relative to the sample size, or it may contain correlated features that together inflate model complexity.

- Solution: Consider a hybrid approach. Use the filter method for aggressive initial pre-screening (e.g., select only the top 100 features), then apply a second-stage feature selection method like Lasso (L1 regularization) or Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) that is embedded within the model training process to further reduce redundancy [34] [33].

Problem: The selected features are biologically implausible or fail to validate.

- Cause: Purely data-driven filter methods can select spurious correlations, especially in high-dimensional settings where chance correlations are likely.

- Solution: Integrate prior biological knowledge. Before or after pre-screening, restrict your feature set to genes known to be in the drug's target pathway or related to cancer hallmarks. This creates a more interpretable and biologically grounded model [35].

Problem: The filter method selects different features when using a slightly different dataset.

- Cause: Instability in feature selection is common in high-dimensional data due to data sparsity and noise.

- Solution: Implement stability selection. Repeat the pre-screening process on multiple bootstrapped samples of your data. The most robust and important features are those that are consistently selected across the majority of these iterations [35].

Key considerations for a robust analysis

The following diagram summarizes the core principles for designing an effective filtering strategy:

- Combine with Other Methods: Filter methods are best used as a pre-processing step. For a highly refined and optimal feature set, combine them with wrapper or embedded methods in a hybrid workflow [34].

- Stability is Key: A good feature set is not just predictive but also stable. Assess the reliability of your selected features across different data subsamples [35].

- Interpretability Matters: The goal in translational research is often to generate testable hypotheses. A smaller, biologically interpretable set of features is frequently more valuable than a slightly more accurate "black box" model with thousands of features [35].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary advantage of using a wrapper method over a filter method for high-dimensional oncology data?

Wrapper methods evaluate feature subsets based on their actual performance with a specific classification model, unlike filter methods that use general statistical metrics. This often leads to superior predictive accuracy because the feature selection is tailored to the learning algorithm. For instance, in breast cancer classification, a hybrid wrapper method combining scatter search with SVM (SSHSVMFS) demonstrated better performance than other contemporary approaches [18].

Q2: My wrapper method is consistently getting stuck in local optima. What strategies can help?

This is a common challenge with wrapper methods like sequential searches or basic evolutionary algorithms. A highly effective strategy is to implement a heuristic tribrid search (HTS) that combines multiple phases. This involves a forward search to add features, a "consolation match" phase that attempts to swap single features between selected and unselected pools to escape local optima, and a final backward elimination to remove redundant features [38]. This approach balances exploration and exploitation in the search space.

Q3: How can I manage the extreme computational cost of wrapper methods on high-dimensional, low-sample-size (HDLSS) genomic data?

A proven methodology is to adopt a two-stage hybrid approach. The first stage uses a fast filter method for pre-processing to drastically reduce the feature space. The second stage employs a wrapper method on this reduced subset. For example, one can use Gradual Permutation Filtering (GPF) to remove irrelevant features based on their importance scores before applying a more computationally intensive wrapper search [38]. This balances efficiency with performance.

Q4: Are there wrapper techniques that provide more stable feature subsets?

Yes, techniques like Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) can be stabilized by using robust algorithms as the core estimator. In esophageal cancer grading research, XGBoost with RFE was successfully used and identified as a top-performing model, demonstrating the practical application and stability of this wrapper method in a high-dimensional clinical data context [39].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Model Performance Decreases After Feature Selection

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Overfitting to the Training Set. Wrapper methods can overfit, especially with small sample sizes.

- Cause: Elimination of Informative but Weakly Relevant Features. Some features may contribute predictive power only in combination with others.

- Solution: Implement ensemble or hybrid methods that consider feature interactions. Methods like the heuristic tribrid search (HTS) are designed to capture these interactions during the search process [38].

Problem: Inconsistent Feature Subsets Across Different Runs

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: High Variance in the Search Algorithm.

- Solution: For stochastic algorithms like Evolutionary Algorithms (EA), increase the number of iterations or the population size. Use a fixed random seed for reproducibility during development. For deterministic methods like RFE, ensure the underlying model (e.g., SVM, Random Forest) is properly regularized [18].

- Cause: High Correlation Between Features (Multicollinearity). The algorithm might see multiple, equally good subsets.

- Solution: Introduce a penalty for the number of features in the performance metric used to guide the wrapper. For example, the Log Comprehensive Metric (LCM) balances classification performance with the number of selected features, favoring smaller, more robust subsets [38].

Performance Comparison of Wrapper and Hybrid Methods

The following table summarizes the performance of various wrapper and hybrid feature selection methods as reported in recent studies on biomedical datasets.

Table 1: Performance of Wrapper and Hybrid Feature Selection Methods in Oncology Data Classification

| Feature Selection Method | Core Search Strategy | Classifier Used | Dataset(s) | Key Performance Metric (Result) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TMGWO (Two-phase Mutation Grey Wolf Optimization) [18] | Hybrid (Evolutionary Algorithm) | Support Vector Machine (SVM) | Wisconsin Breast Cancer | Accuracy: 96% (using only 4 features) |

| SSHSVMFS (Scatter Search Hybrid SVM with FS) [18] | Hybrid (Scatter Search) | Support Vector Machine (SVM) | Colon, Leukemia, Lymphoma | Outperformed other existing methods |

| XGBoost with RFE [39] | Wrapper (Recursive Feature Elimination) | XGBoost | Esophageal Cancer (CT Radiomics) | AUC: 91.36% |

| Heuristic Tribrid Search (HTS) [38] | Hybrid (Forward Search, Consolation, Backward Elimination) | Not Specified | High-Dimensional & Low Sample Size | Prediction model performance improved from 0.855 to 0.927 |

| BBPSO (Binary Black Particle Swarm Optimization) [18] | Hybrid (Evolutionary Algorithm) | Multiple Classifiers | Multiple Datasets | Superior discriminative feature selection and classification performance |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) with a Tree-Based Classifier

This protocol is ideal for high-dimensional data where non-linear relationships are suspected.

- Data Preparation: Split data into training, validation, and test sets. Preprocess (normalize, handle missing values) the training set and apply the same transformations to the validation and test sets.

- Model and RFE Setup: Select a base estimator capable of providing feature importance scores (e.g., Random Forest, XGBoost). Initialize the RFE object, specifying the estimator and the number of features to select. Alternatively, use

RFECVfor automatic selection of the optimal number of features via cross-validation. - Feature Selection: Fit the RFE model on the training data only. The RFE algorithm will:

- Train the model and rank features by importance.

- Prune the least important feature(s).

- Repeat the process with the reduced subset until the desired number of features is reached.

- Model Training & Evaluation: Train a final model on the training data, using only the features selected by RFE. Evaluate its performance on the held-out test set [39].

Protocol 2: A Hybrid Permutation Importance and Heuristic Search Workflow

This protocol is designed for HDLSS datasets to improve robustness and avoid local optima.

- Phase 1: Gradual Permutation Filtering (GPF)

- Aim: Filter out obviously irrelevant features.

- Steps: Calculate permutation importance for each feature multiple times (e.g., 50 trials) on the training set. Iteratively remove features with importance scores near or below zero, recalculating importance after each removal to account for dependencies. This results in a ranked list of candidate features [38].

- Phase 2: Heuristic Tribrid Search (HTS)

- Aim: Find a near-optimal subset from the candidate list.

- Steps:

- Forward Search: Start with a "first-choice feature" from the GPF ranking. Iteratively add the next feature that most improves the model's performance (evaluated via cross-validation).

- Consolation Match: When performance plateaus, try swapping a single feature from the selected set with one from the unselected pool. If performance improves, return to the forward search phase.

- Backward Elimination: Finally, iteratively remove features one-by-one if their exclusion does not harm performance.

- Performance Metric: Use a metric like the Log Comprehensive Metric (LCM) that balances model accuracy with the number of selected features [38].

Workflow Visualization

Hybrid Feature Selection for HDLSS Data

Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) Process

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Wrapper-Based Feature Selection

| Tool / Algorithm | Type / Function | Brief Explanation & Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) | Wrapper Method | Iteratively removes the least important features based on a model's coefficients or feature importance. Highly effective with linear models (SVM) and tree-based classifiers (Random Forest, XGBoost) [39]. |

| Evolutionary Algorithms (EA)(e.g., TMGWO, BBPSO) | Metaheuristic Wrapper | Uses population-based search inspired by natural evolution. Excellent for exploring large, complex feature spaces and avoiding local optima, though computationally intensive [18]. |

| Scatter Search | Metaheuristic Wrapper | A deterministic-evolutionary algorithm that combines solution subsets to generate new ones. Effective for generating high-quality solutions, as demonstrated in SSHSVMFS for medical datasets [18]. |

| Permutation Importance | Filter-based Evaluator | Used to score features by randomly shuffling each feature and measuring the drop in model performance. Often used as a pre-processing step (filter) in hybrid frameworks to reduce the search space for a subsequent wrapper method [38]. |

| Heuristic Tribrid Search (HTS) | Hybrid Search Strategy | A custom search strategy combining forward selection, feature swapping ("consolation match"), and backward elimination. Designed specifically for HDLSS data to find small, high-performing feature subsets [38]. |

| Log Comprehensive Metric (LCM) | Performance Metric | A custom evaluation function that balances classification performance with the number of selected features. Crucial for guiding wrapper methods in HDLSS contexts to prevent overfitting and favor parsimonious models [38]. |

In high-dimensional oncology data research, such as genomic profiling and transcriptomic analysis, feature selection is not a luxury but a necessity. The curse of dimensionality, where the number of features (e.g., genes) vastly exceeds the number of samples (e.g., patients), can severely compromise the performance and interpretability of predictive models for cancer subtype classification or drug response prediction [40]. Embedded feature selection methods offer a powerful solution by integrating the selection process directly into the model training algorithm. This approach efficiently identifies the most biologically relevant features while building a predictive model, ensuring both computational efficiency and robust performance [41] [42]. This guide provides practical troubleshooting advice for implementing these methods in your research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are embedded feature selection methods and why are they preferred for high-dimensional oncology data? Embedded methods perform feature selection as an integral part of the model training process [41] [43]. They are particularly suited for oncology data because they are computationally more efficient than wrapper methods and often achieve better predictive accuracy than simple filter methods by accounting for feature interactions [42]. For instance, tree-based models like Random Forests naturally rank features by their importance during training [41].

2. My Lasso regression model is returning a null model with zero features. How can I fix this? This occurs when the regularization strength (alpha) is set too high, forcing all feature coefficients to zero.

- Solution: Systematically decrease the value of the

alpha(orC=1/alpha) parameter. Use a cross-validated grid search (e.g.,LassoCVin scikit-learn) to find the optimal value that minimizes the prediction error without overshrinking the coefficients. Ensure your target variable is appropriately scaled.

3. Why does my Elastic Net model fail to select a sparse feature set, even with high regularization? Elastic Net combines L1 (Lasso) and L2 (Ridge) penalties. If the L1 ratio is set too low, the model behaves more like Ridge regression, which never shrinks coefficients to zero.

- Solution: Increase the

l1_ratioparameter closer to 1.0 to enforce a stronger L1 penalty for sparsity. A grid search over bothalphaandl1_ratiois recommended for optimal performance [40].

4. How can I stabilize the feature importance scores from a tree-based model like Random Forest? Feature importance from tree-based models can be unstable due to randomness in the bootstrapping and feature splitting.

- Solution:

- Increase the number of trees (

n_estimators). - Use a fixed random seed (

random_state) for reproducibility. - Employ a technique like the TreeEM model, which uses an ensemble of trees combined with feature selection to enhance stability and prediction ability [44].

- Run the model multiple times with different seeds and average the importance scores.

- Increase the number of trees (

5. How do I validate that the selected features are biologically relevant and not spurious correlations? This is a critical step for translational research.

- Solution: Perform robustness checks and causal analysis. A promising approach is to use causal feature selection algorithms like CausalDRIFT, which estimate the Average Treatment Effect (ATE) of each feature on the outcome, helping to prioritize causally relevant variables over merely correlated ones [40]. Furthermore, always validate your findings against known biological pathways and literature.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Model Generalization After Feature Selection

Symptoms: High performance on training data but significantly lower performance on validation or test sets.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Data Leakage | Ensure the feature selection process is fitted only on the training data. | Use a pipeline (e.g., sklearn.pipeline.Pipeline) to encapsulate feature selection and model training. |

| Overfitting to Noise | Plot the model's performance vs. the number of features selected. | Use stricter regularization (higher alpha for Lasso) or a lower number of selected features (max_features in trees). |

| Ignoring Feature Interactions | Check if your model can capture non-linear relationships. | Switch to or add tree-based models (e.g., Random Forest, XGBoost) that naturally handle interactions [44] [43]. |

Issue 2: Inconsistent Selected Feature Subsets

Symptoms: Different runs of the feature selection algorithm on the same dataset yield different feature subsets.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| High Model Variance | Assess the stability of feature importance scores across multiple runs with different random seeds. | For tree-based models, increase n_estimators. For all models, use more data if possible. |

| Highly Correlated Features | Calculate the correlation matrix of the top features. | Use Elastic Net, which can handle correlated features better than Lasso, or apply a clustering step before selection [40]. |

| Unstable Algorithm | N/A | Use algorithms designed for stability. For example, the CEFS+ method uses a rank technique to overcome instability on some datasets [43]. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Benchmarking Embedded Feature Selection Methods

This protocol outlines how to compare the performance of different embedded methods on a high-dimensional oncology dataset (e.g., RNA-seq data from TCGA).

1. Objective: To evaluate and compare the performance of Lasso, Elastic Net, and Tree-based models for feature selection and cancer subtype classification.

2. Materials/Reagents:

- Dataset: A labeled high-dimensional oncology dataset (e.g., TCGA-BRCA [44]).

- Computing Environment: Python with scikit-learn, XGBoost, and pandas libraries.

- Evaluation Metrics: Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-Score [40].

3. Methodology:

1. Data Preprocessing: Handle missing values, standardize continuous features (crucial for Lasso/Elastic Net), and partition data into training (70%), validation (15%), and test (15%) sets.

2. Model Training & Selection:

* For Lasso, perform a cross-validated grid search on the alpha parameter.

* For Elastic Net, perform a cross-validated grid search over alpha and l1_ratio.

* For Tree-based (e.g., Random Forest), perform a search on n_estimators and max_depth.

3. Feature Extraction: Extract the non-zero coefficients from Lasso/Elastic Net or the top-k features based on Gini importance from the tree-based model.

4. Validation: Train a final classifier (e.g., XGBoost [40]) on the training set using only the selected features and evaluate its performance on the held-out test set.

4. Expected Output: A table comparing the performance metrics and the number of features selected by each method.

Protocol 2: A Causal Feature Selection Workflow for Robust Biomarker Discovery

This protocol uses a causal inference approach to move beyond correlation and identify features with potential causal influence.

1. Objective: To identify causally relevant biomarkers from high-dimensional genetic data using the CausalDRIFT algorithm [40].

2. Materials/Reagents:

- Dataset: A clinical dataset with genetic features and a clear outcome (e.g., survival, treatment response).

- Computing Environment: Python with the CausalDRIFT package and Double Machine Learning libraries.

- Evaluation Metrics: Average Treatment Effect (ATE), model consistency (standard deviation of metrics) [40].

3. Methodology: 1. Data Preparation: Prepare the feature matrix and outcome vector. Define potential confounders. 2. ATE Estimation: For each feature, CausalDRIFT uses Double Machine Learning to estimate its ATE on the outcome, adjusting for all other features as potential confounders. 3. Feature Ranking: Rank features based on the absolute value of their estimated ATEs. 4. Validation: Assess the robustness and generalizability of the selected feature set by examining the consistency of the ATE estimates and the model's performance across different data splits.

4. Expected Output: A ranked list of features based on their ATE, providing a more interpretable and potentially clinically actionable set of biomarkers.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for selecting and applying an embedded feature selection method, as described in the experimental protocols.

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below summarizes key computational "reagents" – algorithms and tools – essential for experiments in embedded feature selection.

| Research Reagent | Function & Application in Oncology Research |

|---|---|

| Lasso (L1 Regularization) | Linear model that performs feature selection by shrinking less important feature coefficients to zero. Useful for creating sparse, interpretable models from thousands of genomic features [41] [42]. |

| Elastic Net | A hybrid of Lasso and Ridge regression that can handle groups of correlated features, which is common in genetic data due to co-expression [40]. |

| Tree-Based Models (Random Forest, XGBoost) | Provide native feature importance scores based on how much a feature decreases impurity across all trees. Effective at capturing complex, non-linear interactions between biomarkers [44] [41]. |

| CausalDRIFT Algorithm | A causal dimensionality reduction tool that estimates the Average Treatment Effect of each feature, helping to distinguish causally relevant biomarkers from spurious correlations in observational clinical data [40]. |

| Max-Relevance and Min-Redundancy (MRMR) | A feature selection criterion often used in conjunction with ensemble models (e.g., TreeEM) to select features that are highly relevant to the target while being minimally redundant with each other [44]. |

Swarm and Evolutionary Algorithms (bABER, HybridGWOSPEA2ABC) for Complex Optimization

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental principle behind the bABER method for root-finding in high-dimensional data analysis? The bABER (presumably based on the Aberth method) is a root-finding algorithm designed for the simultaneous approximation of all roots of a univariate polynomial. It uses an electrostatic analogy, modeling approximated zeros as negative point charges that repel each other while being attracted to the true, fixed positive roots. This prevents multiple starting points from incorrectly converging to the same root, a common issue with naive Newton-type methods. The method is known for its cubic convergence rate, which is faster than the quadratic convergence of methods like Durand–Kerner, though it converges linearly at multiple zeros [45].

Q2: How does the HybridGWOSPEA2ABC algorithm enhance feature selection for cancer classification? The HybridGWOSPEA2ABC algorithm integrates the Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO), Strength Pareto Evolutionary Algorithm 2 (SPEA2), and Artificial Bee Colony (ABC) to enhance feature selection. This hybrid approach leverages swarm intelligence and evolutionary computation to maintain solution diversity, improve convergence efficiency, and balance exploration and exploitation within the high-dimensional search space of gene expression data. It has demonstrated superior performance in identifying relevant cancer biomarkers compared to conventional bio-inspired algorithms [46].

Q3: My bABER iteration is not converging. What could be the cause? Non-convergence in bABER can stem from several sources:

- Poor Initial Approximations: The choice of starting points is critical. Initial approximations should be selected within known bounds of the roots, which can be computed from the polynomial's coefficients [45].

- Ill-Conditioned Polynomials: Polynomials with multiple or closely clustered roots can cause linear convergence or instability [45].

- Numerical Precision Issues: The computation of

p(z_k)andp'(z_k)can be prone to floating-point errors, especially for high-degree polynomials. Using higher precision arithmetic can mitigate this.

Q4: When using HybridGWOSPEA2ABC, the algorithm gets stuck in local optima. How can this be improved? The ABC component is primarily responsible for exploration. If the algorithm is getting stuck, consider adjusting the parameters controlling the ABC phase, specifically those related to the "scout bee" behavior, which is designed to abandon poor solutions and search for new ones. Ensuring a proper balance between the intensification (exploitation) driven by GWO and the diversification (exploration) from ABC and SPEA2 is key [46].

Q5: How do I handle very high-degree polynomials with the bABER method to avoid computational bottlenecks?

For high-degree polynomials, the simultaneous update of all roots can be computationally expensive. Implement an efficient method to compute p(z_k) and p'(z_k) for all approximations simultaneously, such as Horner's method or leveraging polynomial evaluation techniques. The iteration can be performed in a Jacobi-like (all updates simultaneous) or Gauss–Seidel-like (using new approximations immediately) manner, with the latter sometimes offering faster convergence [45].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Slow or Non-Convergence in bABER Method

Symptoms: The root approximations oscillate, diverge, or the change between iterations remains unacceptably high after many steps.

Diagnosis and Resolution:

| Step | Action | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Verify Initial Points | Ensure initial approximations are not clustered. Use known root bounds derived from polynomial coefficients to generate well-spread starting values [45]. |

| 2 | Check for Multiple Roots | The method converges linearly at multiple zeros. If suspected, consider implementing a deflation technique or shifting to a method better suited for multiple roots [45]. |

| 3 | Profile Computational Load | The calculation of the sum over j≠k 1/(z_k - z_j) is O(n²). For large n, verify this is the performance bottleneck and optimize the code, potentially using parallelization [45]. |

Issue 2: Poor Feature Selection Performance with HybridGWOSPEA2ABC

Symptoms: The selected gene subsets yield consistently low classification accuracy across multiple classifiers, or the algorithm fails to reduce the feature set meaningfully.

Diagnosis and Resolution:

| Step | Action | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tune Hyperparameters | The performance is highly sensitive to parameters like population size and the balance between GWO, SPEA2, and ABC operators. Use a systematic approach like grid search for optimization [46]. |

| 2 | Validate Fitness Function | The fitness function must balance two objectives: classification accuracy and the number of selected features. Review the multi-objective selection mechanism from SPEA2 to ensure it is not biased [46]. |

| 3 | Compare with Benchmarks | Test the algorithm on standard cancer datasets and compare its performance with other bio-inspired algorithms to isolate if the issue is with the implementation or the method itself [46]. |

Issue 3: Numerical Instability in Polynomial Evaluation

Symptoms: Unusual jumps in root approximations, or NaN/Inf values appearing during the bABER iteration.

Diagnosis and Resolution:

| Step | Action | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Use Robust Evaluation | Employ numerically stable algorithms for polynomial and derivative evaluation to prevent catastrophic cancellation or overflow, especially with large coefficients [45]. |

| 2 | Implement Safeguards | Add code to check for exceptionally small denominators or large corrections w_k that could lead to instability and trigger a restart with different initial points if necessary. |

| 3 | Increase Precision | Switch from single to double or arbitrary-precision arithmetic to manage rounding errors inherent in the calculations [45]. |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies