Advanced Feature Extraction Techniques for Cancer Detection: From Biomarkers to Deep Learning

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the latest feature extraction methodologies revolutionizing cancer detection and diagnosis.

Advanced Feature Extraction Techniques for Cancer Detection: From Biomarkers to Deep Learning

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the latest feature extraction methodologies revolutionizing cancer detection and diagnosis. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of identifying key biomarkers through bioinformatics and data mining. The scope extends to advanced methodological applications, including hybrid feature selection, deep learning architectures like CNNs and Vision Transformers, and the extraction of tissue-specific characteristics from medical images. It also addresses critical challenges in model optimization, data heterogeneity, and clinical integration, while providing a comparative analysis of validation frameworks and performance metrics. This resource synthesizes cutting-edge research to guide the development of robust, explainable, and clinically actionable AI tools in oncology.

The Foundation of Cancer Biomarkers: Exploring Genetic, Imaging, and Data Mining Approaches

Bioinformatics and Data Mining for Biomarker Discovery

The integration of bioinformatics and data mining has become a cornerstone of modern biomarker discovery, particularly in the field of oncology. The ability to computationally analyze high-dimensional biological data is transforming how researchers identify, validate, and translate biomarkers from laboratory findings to clinical applications [1]. This shift is enabling a move from single-marker approaches to multiparameter strategies that capture the complex biological signatures of cancer, thereby driving advancements in personalized treatment paradigms [1]. The technological renaissance in biomarker discovery is largely driven by breakthroughs in multi-omics integration, spatial biology, artificial intelligence (AI), and high-throughput analytics, which collectively offer unprecedented resolution, speed, and translational relevance [1].

A significant challenge in this domain is the inherent complexity of biological data, characterized by high dimensionality where the number of features (e.g., genes, proteins) vastly exceeds the number of available samples [2] [3]. This "p >> n problem" is further complicated by various sources of technical noise, biological variance, and potential confounding factors [3]. Success in this field, therefore, depends not only on choosing the right computational technologies but also on aligning them with specific research objectives, disease contexts, and developmental stages [1]. This application note provides a structured framework for leveraging bioinformatics and data mining techniques to overcome these challenges and advance cancer detection research through robust biomarker discovery.

Multi-Omics Data Integration and Analysis

Data Types and Technological Platforms

Multi-omics profiling represents a fundamental approach to biomarker discovery, providing a holistic view of molecular processes by integrating genomic, epigenomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic data [1]. The integration of these diverse data types can reveal novel insights into the molecular basis of diseases and drug responses, ultimately leading to the identification of new biomarkers and therapeutic targets [1]. Gene expression analysis, in particular, has emerged as a critical component for addressing fundamental challenges in cancer diagnosis and drug discovery [2].

Table 1: Primary Data Types and Platforms in Multi-Omics Biomarker Discovery

| Data Type | Description | Key Technologies | Key Applications in Biomarker Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomics | Study of an organism's complete DNA sequence. | Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS), Whole Genome Sequencing | Identification of inherited mutations and somatic variants associated with cancer risk and progression. |

| Transcriptomics | Quantitative analysis of RNA expression levels. | RNA-Sequencing (RNA-Seq), DNA Microarrays | Discovery of differentially expressed genes and expression signatures indicative of cancer presence, type, or stage [2]. |

| Proteomics | Large-scale study of proteins, including their structures and functions. | Mass Spectrometry, Multiplex Immunohistochemistry (IHC) | Identification of protein biomarkers and signaling pathway alterations; validation of transcriptional findings [1]. |

| Epigenomics | Study of chemical modifications to DNA that regulate gene activity. | ChIP-Seq, Bisulfite Sequencing | Discovery of methylation patterns and histone modifications that influence gene expression in cancer cells. |

RNA-Sequencing (RNA-Seq) has largely superseded DNA microarrays due to its greater specificity, resolution, sensitivity to differential expression, and dynamic range [2]. This NGS method involves converting RNA molecules into complementary DNA (cDNA) and determining the nucleotide sequence, allowing for comprehensive gene expression analysis and quantification [2]. The data generated from these platforms provide the foundational material for subsequent computational mining and biomarker identification.

Data Preprocessing and Quality Control

Raw biomedical data is invariably influenced by preanalytical factors, resulting in systematic biases and signal variations that must be addressed prior to analysis [3]. A rigorous preprocessing and quality control pipeline is essential for generating reliable and interpretable results.

Key Preprocessing Steps:

- Quality Control: Implement data type-specific quality metrics using established software packages (e.g., fastQC/FQC for NGS data, arrayQualityMetrics for microarray data) to assess read quality, nucleotide distribution, and potential contaminants [3].

- Filtering: Remove features with zero or near-zero variance, as they are uninformative for downstream analysis. Attributes with a large proportion of missing values (e.g., >30%) should also be considered for removal [3].

- Normalization and Transformation: Apply appropriate normalization methods to correct for technical variations (e.g., sequencing depth, batch effects). Variance stabilizing transformations are often necessary for omics data where signal variance depends on the average intensity [3].

- Imputation: For features with a limited number of missing values, apply suitable imputation methods, taking care to consider the potential mechanisms behind the missingness [3].

The successful application of these steps should be verified by conducting quality checks both before and after preprocessing to ensure issues are resolved without introducing artificial patterns [3].

Computational Methodologies for Biomarker Discovery

Feature Selection and Dimensionality Reduction

The high dimensionality of omics data presents a significant challenge for analysis. Feature selection techniques are critical for identifying the most informative subset of biomarkers from thousands of initial candidates, thereby improving model performance and interpretability [4]. These methods can be broadly classified into filter, wrapper, and embedded approaches [2].

Hybrid Sequential Feature Selection: Recent advances advocate for hybrid approaches that combine multiple feature selection methods to leverage their complementary strengths, enhancing the stability and reproducibility of the selected biomarkers [4]. A representative workflow is as follows:

- Variance Thresholding: As an initial filter, remove genes with minimal expression variation across samples, as they are unlikely to be discriminatory.

- Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE): Iteratively construct a model (e.g., using Support Vector Machines or Random Forests) and remove the weakest features until an optimal subset is identified.

- Regularization with LASSO Regression: Apply an embedded method that penalizes the absolute size of regression coefficients, effectively driving the coefficients of non-informative features to zero and performing feature selection in the process [4].

This hybrid strategy should be implemented within a nested cross-validation framework to ensure robust feature selection and prevent overoptimistic performance estimates [4].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Machine Learning Models in Biomarker Discovery

| Model Category | Specific Model | Key Advantages | Considerations for Biomarker Discovery | Reported Test Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional ML | Support Vector Machines (SVM) | Effective in high-dimensional spaces; versatile kernel functions. | Performance can be sensitive to kernel and parameter choice. | Varies; can be high with proper feature engineering [2]. |

| Conventional ML | Random Forest | Robust to noise; provides feature importance metrics. | Less interpretable than single decision trees; can be computationally expensive. | Varies; demonstrates robust performance [4]. |

| Conventional ML | Logistic Regression | Simple, interpretable, provides coefficient significance. | Requires linear relationship assumption; prone to overfitting with many features. | Used for robust classification in validation [4]. |

| Deep Learning | Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) | Can learn complex, non-linear relationships. | Prone to overfitting on small omics datasets. | Upwards of 90% with feature engineering [2]. |

| Deep Learning | Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) | Excels at identifying local spatial patterns. | Requires data transformation into image-like arrays for 2D CNNs. | Among the best-performing DL models [2]. |

| Deep Learning | Graph Neural Networks (GNN) | Models biological interactions between genes as a network. | Requires constructing a gene interaction graph. | Shows great potential for future analysis [2]. |

Machine Learning and Deep Learning Models

Machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) are indispensable for analyzing the complex, high-dimensional data generated in biomarker studies. AI is capable of pinpointing subtle biomarker patterns in multi-omic and imaging datasets that conventional methods may miss [1].

Conventional Machine Learning models like Support Vector Machines, Random Forests, and Logistic Regression are widely used and can achieve robust classification performance, especially when coupled with effective feature selection [4]. They are often less computationally intensive and can be more interpretable than deep learning models.

Deep Learning Architectures have demonstrated superior performance in identifying complex patterns. Key architectures include:

- Multi-Layer Perceptrons (MLP): The simplest form of DNNs, with full connectivity between layers [2].

- Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN): Initially designed for images, they have been adapted for omics data by transforming it into two-dimensional arrays, leveraging their ability to capture local spatial relations [2].

- Recurrent Neural Networks (RNN): Suitable for capturing sequential correlations in time-series or ordered gene expression data [2].

- Graph Neural Networks (GNN): Designed to learn from graph-structured data, making them ideal for modeling gene regulatory networks and protein-protein interactions [2].

- Transformers: Utilize a self-attention mechanism to weigh the importance of different genes in a sequence, proving highly effective for capturing long-range dependencies in genomic data [2].

To address the challenge of small sample sizes, transfer learning techniques can be employed, where information is transferred from a model trained on a large, related dataset to the specific biomarker discovery task at hand [2].

Experimental Protocols and Workflow

Integrated Computational-Experimental Workflow for Biomarker Discovery and Validation

The following protocol outlines a comprehensive workflow for biomarker discovery and validation, integrating the computational and experimental techniques discussed. This protocol is designed to be implemented within the context of a broader research program on feature extraction for cancer detection.

Phase 1: Data Acquisition and Curation

- Biospecimen Collection: Obtain relevant biospecimens (e.g., tissue biopsies, blood for liquid biopsy) from well-characterized patient cohorts and matched controls. Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval and informed consent are mandatory [4].

- Multi-Omics Profiling: Perform high-throughput profiling. For transcriptomics, extract total RNA and prepare sequencing libraries for RNA-Seq on an NGS platform. Aim for sufficient sequencing depth (e.g., 30-50 million reads per sample) and technical replicates to ensure data quality [4].

- Data Quality Control and Standardization: Process raw data through type-specific quality control pipelines (e.g., fastQC for RNA-Seq). Adhere to standardized reporting guidelines (e.g., MIAME for microarrays, MINSEQE for sequencing) [3]. Curate clinical data to resolve inconsistencies and transform them into standard formats (e.g., OMOP, CDISC) [3].

Phase 2: Computational Analysis and Biomarker Identification

- Data Preprocessing: Preprocess the raw count or intensity data. This includes normalization (e.g., TPM for RNA-Seq, RMA for microarrays), log2 transformation, and batch effect correction using methods like ComBat [3].

- Hybrid Sequential Feature Selection: Implement the feature selection pipeline within a nested cross-validation framework to ensure robustness.

- Apply variance thresholding to remove the least variable genes (e.g., bottom 20%).

- Perform Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) wrapped around a Support Vector Machine (SVM) classifier to iteratively refine the feature set.

- Apply LASSO regression to the refined feature set from RFE to further select the most predictive biomarkers and shrink the coefficients of others to zero [4].

- Predictive Model Building and Evaluation: Train multiple machine learning models (e.g., Random Forest, SVM, Logistic Regression) on the selected biomarker panel. Use a strict hold-out test set or repeated k-fold cross-validation to evaluate performance metrics such as accuracy, AUC-ROC, sensitivity, and specificity [2] [4]. The results should be compared against baseline models using traditional clinical variables alone to demonstrate added value [3].

Phase 3: Experimental Validation

- Independent Technical Validation: Validate the expression patterns of the top-ranked computationally identified biomarkers using an independent technological platform. Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR) is highly recommended for its absolute quantification and high sensitivity. Design specific primers/probes for the candidate mRNA biomarkers and run samples (cases and controls) in technical replicates. Consistency between the NGS expression patterns and ddPCR results confirms technical robustness [4].

- Functional Validation (Context-Dependent): To establish biological relevance, employ advanced models that better mimic human biology.

- Organoids: Utilize patient-derived organoids to recapitulate the complex architecture and functions of human tissues. These can be used for functional biomarker screening, target validation, and exploration of resistance mechanisms [1].

- Spatial Biology Techniques: Apply multiplex immunohistochemistry (IHC) or spatial transcriptomics to validated samples to confirm the protein expression and spatial localization of biomarkers within the tumor microenvironment (TME), which can be critical for their utility [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Biomarker Discovery

| Item / Reagent | Function / Application | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Purification Kit | Isolation of high-quality total RNA from biospecimens for downstream sequencing or validation. | GeneJET RNA Purification Kit [4]. |

| RNA-Seq Library Prep Kit | Preparation of sequencing-ready libraries from purified RNA for transcriptomic profiling. | Kits from Illumina, Thermo Fisher Scientific. |

| ddPCR Supermix & Assays | Absolute quantification and validation of specific mRNA biomarker candidates with high sensitivity. | Bio-Rad's ddPCR EvaGreen Supermix or TaqMan-based assays [4]. |

| Cell Culture Media | Maintenance and expansion of cell lines, including patient-derived B-lymphocytes or organoids. | RPMI 1640 for B-cells [4]; specialized media for organoid cultures. |

| Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) | Immortalization of primary B-lymphocytes to create stable cell lines for renewable material. | B95-8 strain for transforming patient lymphocytes [4]. |

| Multiplex IHC/IF Antibody Panels | Simultaneous detection of multiple protein biomarkers in situ to study spatial relationships in the TME. | Validated antibody panels for immune cell markers and cancer markers. |

| Feature Selection Software | Computational tools for implementing filter, wrapper, and embedded feature selection methods. | Scikit-learn in Python (e.g., SelectKBest, RFE, LassoCV). |

| Machine Learning Frameworks | Platforms for building, training, and evaluating conventional and deep learning models. | Python with Scikit-learn, TensorFlow, PyTorch; R with caret and mlr [2]. |

The structured application of bioinformatics and data mining is paramount for navigating the complexities of modern biomarker discovery. By leveraging multi-omics data integration, robust computational methodologies, and rigorous validation protocols, researchers can significantly enhance the discovery and translation of biomarkers for cancer detection. The integration of AI and spatial biology technologies promises to further deepen our understanding of cancer biology, moving the field toward more personalized and effective cancer diagnostics and therapies. The workflow and protocols detailed herein provide a actionable roadmap for researchers engaged in this critical endeavor.

Within cancer detection research, feature extraction techniques are pivotal for identifying discriminative patterns from complex biological data. The integration of genomic features—such as gene expression, somatic mutations, and copy number variations (CNV)—into predictive models relies on robust and reproducible analysis pipelines [5]. This protocol details the use of two public resources, The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and the UCSC Xena platform, to acquire and analyze these genomic features, providing a foundational methodology for research framed within the broader context of feature-based cancer detection [6] [7].

Key Databases and Tools for Genomic Analysis

The following table summarizes the core public resources utilized in this protocol.

Table 1: Key Databases and Platforms for Cancer Genomics

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Key Features | URL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) [6] | Data Repository | Stores multi-omics data from large-scale cancer studies. | Provides genomic, epigenomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic data for over 20,000 primary cancer samples across 33 cancer types. | https://www.cancer.gov/ccg/research/genome-sequencing/tcga |

| UCSC Xena [8] [7] | Analysis & Visualization Platform | Enables integrated exploration and visualization of multi-omics data. | Allows users to view their own data alongside public datasets (e.g., TCGA). Features a "Visual Spreadsheet" to compare different data types. | http://xena.ucsc.edu/ |

| cBioPortal [9] | Analysis & Visualization Platform | Provides intuitive visualization and analysis for complex cancer genomics data. | Offers tools for multidimensional analysis of cancer genomics datasets, including mutation, CNA, and expression data. | http://www.cbioportal.org |

| Chinese Glioma Genome Atlas (CGGA) [9] | Data Repository | A complementary repository focusing on glioma. | Includes mRNA sequencing, DNA copy-number arrays, and clinical data for hundreds of glioma patients. | http://www.cgga.org.cn/ |

The following table lists essential materials and digital tools required for executing the analyses described in this protocol.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item Name | Category | Function/Application | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| TCGA Genomic Data | Data | The primary source of raw genomic and clinical data used for analysis. | Includes RNA-seq, DNA copy-number arrays, SNP arrays, and clinical metadata [9] [6]. |

| X-tile Software | Computational Tool | Determines optimal cut-off values for converting continuous data into categorical groups (e.g., high vs. low expression) for survival analysis [9]. | Available from: http://medicine.yale.edu/lab/rimm/research/software.aspx |

| Statistical Analysis Environment | Computational Tool | Used for performing survival analysis and other statistical tests. | R or Python with appropriate libraries (e.g., survival in R). |

| Kaplan-Meier Estimator | Statistical Method | Used to visualize and estimate survival probability over time. | The log-rank test is used to compare survival curves between groups [9]. |

Experimental Protocol: EGFR Analysis in Lung Adenocarcinoma

This section provides a detailed, step-by-step protocol for analyzing EGFR aberrations in lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) using TCGA data via the UCSC Xena platform, replicating a common analysis for correlating genomic alterations with gene expression [8].

Data Acquisition and Initial Visualization

- Launch UCSC Xena: Navigate to the UCSC Xena website at http://xena.ucsc.edu/ and click 'Launch Xena'. This will open the Visual Spreadsheet Wizard.

- Select Dataset: In the wizard, type 'GDC TCGA Lung Adenocarcinoma (LUAD)' and select this study from the dropdown menu. Click 'To first variable' to load the dataset.

- Choose Genomic Features: Type 'EGFR' in the search bar. Select the checkboxes for Gene Expression, Copy Number, and Somatic Mutation. Click 'To second variable' [8].

The platform will generate a Visual Spreadsheet with four columns:

- Column A (Sample ID): Identifies the patient samples.

- Column B (Gene Expression): Displays the expression level of EGFR, typically color-coded (e.g., red for high expression).

- Column C (Copy Number): Shows copy number variation data for the EGFR genomic locus (e.g., red for amplification).

- Column D (Somatic Mutation): Indicates the presence of somatic mutations in EGFR (e.g., blue tick marks) [8].

Biological Interpretation: An initial observation should reveal that samples with high expression of EGFR (red in Column B) often have concurrent amplifications (red in Column C) or mutations (blue ticks in Column D) in the EGFR gene, suggesting a potential mechanism for the elevated expression [8].

Data Manipulation and Exploration

- Move Columns: To change the sorting of samples, click on the header of Column C (Copy Number) and drag it to the left, placing it as the first column after the sample ID (Column B). The Visual Spreadsheet will re-sort the samples based on the copy number values.

- Resize Columns: To view data in more detail, click and drag the handle in the lower-right corner of Column D (Somatic Mutation) to widen it.

- Zoom In on a Column: Click and drag horizontally within a data column to zoom in on a specific value range. Click the 'Zoom out' text at the top of the column to reset the view.

- Zoom In on Samples: Click and drag vertically along the sample axis to focus on a specific subset of patients. Use 'Zoom out' or 'Clear zoom' at the top of the spreadsheet to reset the view [8].

Survival Analysis Methodology

To correlate genomic features with clinical outcomes, perform a survival analysis.

- Data Preparation: Download the relevant clinical data (including overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) times and events) along with the genomic feature of interest (e.g., EGFR expression levels) from TCGA via Xena or the Genomic Data Commons.

- Dichotomization: Use X-tile software to determine the statistically optimal cut-off score to divide the patient cohort into "high" and "low" expression groups based on the continuous EGFR expression data [9].

- Generate Survival Curves: Using a statistical software environment (e.g., R), plot the OS and PFS using Kaplan-Meier survival curves for the two patient groups.

- Statistical Comparison: Compare the survival curves between the high and low expression groups using the log-rank test to determine if the observed difference in survival is statistically significant [9].

Workflow Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the complete integrated workflow for genomic feature extraction and analysis using TCGA and UCSC Xena, as described in this protocol.

This application note provides a structured protocol for leveraging TCGA and UCSC Xena to conduct mutation and expression analysis. The outlined workflow—from data access and visualization to survival analysis—enables researchers to efficiently extract and validate genomic features. Integrating these features with advanced classification models, such as the hybrid deep learning approaches noted in the broader thesis context, holds significant potential for improving the accuracy of cancer detection and prognostication.

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) represents a biologically diverse group of malignancies originating from the mucosal epithelium of the oral cavity, pharynx, larynx, and paranasal sinuses [10] [11]. As the seventh most common cancer worldwide, HNSCC accounts for approximately 660,000 new diagnoses annually, with a rising incidence particularly among younger populations [12] [11]. Despite advancements in multimodal treatment approaches encompassing surgery, radiotherapy, and systemic therapy, the five-year survival rate for advanced-stage disease remains approximately 60%, underscoring the critical need for improved early detection and personalized treatment strategies [10] [12].

The evolving paradigm of precision oncology has intensified research into molecular biomarkers that can enhance diagnostic accuracy, prognostic stratification, and treatment selection. HNSCC manifests through two primary etiological pathways: HPV-driven carcinogenesis, which conveys a more favorable prognosis, and traditional tobacco- and alcohol-associated carcinogenesis [12] [11]. This molecular heterogeneity necessitates biomarker development that captures the distinct biological behaviors of these HNSCC subtypes.

Within the broader context of feature extraction techniques for cancer detection research, biomarker discovery in HNSCC represents a compelling case study in translating multi-omics data into clinically actionable tools. This application note systematically outlines current and emerging diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers in HNSCC, provides detailed experimental protocols for their detection, and situates these methodologies within the computational framework of feature extraction and analysis.

Established and Emerging Biomarkers in HNSCC

Diagnostic Biomarkers

Diagnostic biomarkers facilitate the initial detection and confirmation of HNSCC, often through minimally invasive methods. While tissue biopsy remains the diagnostic gold standard, liquid biopsy approaches have emerged as promising alternatives for initial screening and disease monitoring [12].

Table 1: Established and Emerging Diagnostic Biomarkers in HNSCC

| Biomarker Category | Specific Biomarkers | Detection Method | Clinical Utility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Viral Markers | HPV DNA/RNA, p16INK4a | PCR, ISH, IHC | Diagnosis of HPV-driven OPSCC [12] [11] |

| Circulating Tumor Markers | ctHPV DNA (for HPV+ cases) | PCR-based liquid biopsy | Post-treatment surveillance, recurrence monitoring [11] |

| Methylation Markers | Promoter hypermethylation of multiple genes | Methylation-specific PCR | Early detection in salivary samples [10] |

| Protein Markers | Various proteins (e.g., immunoglobulins, cytokines) | Mass spectrometry, immunoassays | Distinguishing HNSCC from healthy controls [12] |

Prognostic and Predictive Biomarkers

Prognostic biomarkers provide information about disease outcomes irrespective of treatment, while predictive biomarkers forecast response to specific therapies. In HNSCC, these biomarkers guide therapeutic decisions and intensity modifications.

Table 2: Key Prognostic and Predictive Biomarkers in HNSCC

| Biomarker | Type | Detection Method | Prognostic/Predictive Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| HPV/p16 status | Prognostic/Predictive | IHC (p16), PCR/ISH (HPV) | Favorable prognosis in OPSCC; enhanced response to immunotherapy [12] [11] |

| PD-L1 CPS | Predictive | IHC | Predicts response to immune checkpoint inhibitors [13] |

| Tumor Mutational Burden (TMB) | Predictive | Next-generation sequencing | Predicts response to immunotherapy [13] |

| Chemokine Receptors (CXCR2, CXCR4, CCR7) | Prognostic | IHC, PCR | Association with lymph node metastasis and survival [10] |

| Microsatellite Instability (MSI) | Predictive | PCR, NGS | Predicts response to immunotherapy [10] [13] |

HPV status represents one of the most significant prognostic factors in HNSCC, particularly for oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC). HPV-positive OPSCC demonstrates distinctly superior treatment responses and survival outcomes compared to HPV-negative disease, leading to its recognition as a separate staging entity in the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) 8th edition guidelines [12]. The most accurate method for determining HPV status involves detection of E6/E7 mRNA transcripts, though combined p16 immunohistochemistry (as a surrogate marker) with HPV DNA PCR demonstrates similar sensitivity and specificity rates [12] [11].

Emerging liquid biopsy approaches, particularly circulating tumor HPV DNA (ctHPVDNA), show exceptional promise for post-treatment surveillance. Studies report positive and negative predictive values approaching 95-100% for detecting recurrence, potentially complementing or supplementing traditional imaging surveillance [11]. Beyond viral biomarkers, tumor-intrinsic factors including chemokine receptor expression (CXCR2, CXCR4, CCR7) correlate with metastatic potential and survival outcomes, positioning them as potential prognostic indicators [10].

Experimental Protocols for Biomarker Detection

HPV Status Determination via p16 Immunohistochemistry and HPV DNA PCR

Principle: This dual-method approach leverages the surrogate marker p16 (overexpressed in HPV-driven carcinogenesis due to E7 oncoprotein activity) with direct detection of HPV DNA for comprehensive assessment of HPV-related tumor status [12] [11].

Materials:

- Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumor tissue sections

- Primary anti-p16 antibody

- IHC detection system

- DNA extraction kit

- HPV PCR primers

- Thermal cycler

Procedure:

- p16 Immunohistochemistry:

- Cut 4-5μm sections from FFPE tissue blocks.

- Deparaffinize and rehydrate through xylene and graded alcohols.

- Perform antigen retrieval using appropriate buffer.

- Incubate with primary anti-p16 antibody.

- Detect using appropriate IHC detection system.

- Counterstain, dehydrate, and mount.

- Interpret staining as positive when showing ≥70% nuclear and cytoplasmic expression.

- HPV DNA PCR:

- Extract DNA from FFPE tissue sections.

- Quantify DNA concentration and quality.

- Amplify using consensus primers for HPV.

- Perform gel electrophoresis to detect amplification.

- Confirm HPV genotype with type-specific primers.

Interpretation: Cases are considered HPV-driven if both p16 IHC and HPV DNA PCR are positive. Discordant cases require additional validation via HPV E6/E7 mRNA in situ hybridization [11].

Circulating Tumor HPV DNA Detection

Principle: This liquid biopsy technique detects tumor-derived HPV DNA fragments in plasma, serving as a minimally invasive biomarker for disease monitoring [11].

Materials:

- Blood collection tubes

- Plasma separation equipment

- DNA extraction kit

- ddPCR or NGS platform

- HPV-specific primers/probes

Procedure:

- Collect blood in EDTA tubes.

- Separate plasma via centrifugation.

- Extract cell-free DNA.

- Detect HPV DNA using:

- Droplet Digital PCR: Partition sample into droplets, amplify with HPV-specific probes, and count positive droplets for absolute quantification.

- Next-Generation Sequencing: Prepare sequencing library, capture target regions, and sequence.

- Analyze data with appropriate bioinformatics pipelines.

Interpretation: Presence of ctHPVDNA indicates active disease, while clearance during treatment correlates with response. Reappearance or rising levels suggest recurrence [11].

Feature Extraction from HNSCC Genomic Data

Principle: Machine learning approaches enable identification of prognostic gene signatures from high-dimensional genomic data through sophisticated feature extraction and selection methodologies [14] [15].

Materials:

- HNSCC transcriptomic datasets

- Computational resources

- R or Python with appropriate libraries

Procedure:

- Data Acquisition: Obtain HNSCC gene expression data from public repositories.

- Preprocessing: Normalize data, handle missing values, and perform quality control.

- Feature Selection:

- Apply univariate Cox regression to identify genes associated with survival.

- Implement hybrid filter-wrapper feature selection:

- Greedy stepwise search to identify features correlated with outcome but not with each other.

- Best-first search with logistic regression for final feature subset selection.

- Model Building:

- Develop machine learning-derived prognostic model using algorithm combinations.

- Validate model performance through time-dependent ROC curves and Kaplan-Meier analysis.

Interpretation: The resulting risk score stratifies patients into prognostic subgroups and informs therapeutic selection [14].

Visualization of Biomarker Detection Workflows

Comprehensive HNSCC Biomarker Analysis Pathway

Liquid Biopsy Biomarker Detection Workflow

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for HNSCC Biomarker Studies

| Category | Specific Reagents/Platforms | Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Detection | Anti-p16 antibody, HPV DNA/RNA probes, PCR reagents | HPV status determination | High specificity for HPV-driven cancers [11] |

| Liquid Biopsy Platforms | ddPCR systems, NGS platforms, cfDNA extraction kits | Circulating biomarker analysis | Minimal invasiveness, dynamic monitoring [11] [13] |

| Immunohistochemistry | PD-L1 IHC assays, automated staining systems | Tumor microenvironment analysis | Predictive for immunotherapy response [13] |

| Computational Tools | R/Python with survival, glmnet, and caret packages | Feature extraction and model development | Identifies prognostic signatures from high-dimensional data [14] [15] |

| Cell Surface Marker Analysis | Antibodies against CXCR2, CXCR4, CCR7 | Metastasis potential assessment | Flow cytometry or IHC applications [10] |

Discussion and Future Perspectives

The integration of feature extraction methodologies with traditional biomarker discovery represents a paradigm shift in HNSCC research. Machine learning algorithms, particularly when applied to multi-omics data, have demonstrated remarkable capability in identifying complex biomarker signatures that outperform individual biomarkers [14]. The development of a machine learning-derived prognostic model (MLDPM) incorporating 81 algorithm combinations exemplifies this approach, effectively eliminating artificial bias and achieving high prognostic accuracy [14].

Future directions in HNSCC biomarker research will likely focus on several key areas. First, the validation of liquid biopsy biomarkers for early detection and minimal residual disease monitoring holds tremendous potential for improving patient outcomes through earlier intervention [11] [13]. Second, the integration of multidimensional biomarkers—incorporating genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and clinical features—will enable more precise patient stratification [14] [16]. Finally, the application of explainable artificial intelligence techniques will be crucial for clinical adoption, providing transparency in model decisions and enhancing clinician trust [15].

The evolving landscape of HNSCC biomarkers underscores the critical importance of feature extraction techniques in translating complex biological data into clinically actionable tools. As these methodologies continue to advance, they promise to unlock new dimensions of personalized medicine for HNSCC patients, ultimately improving survival and quality of life outcomes.

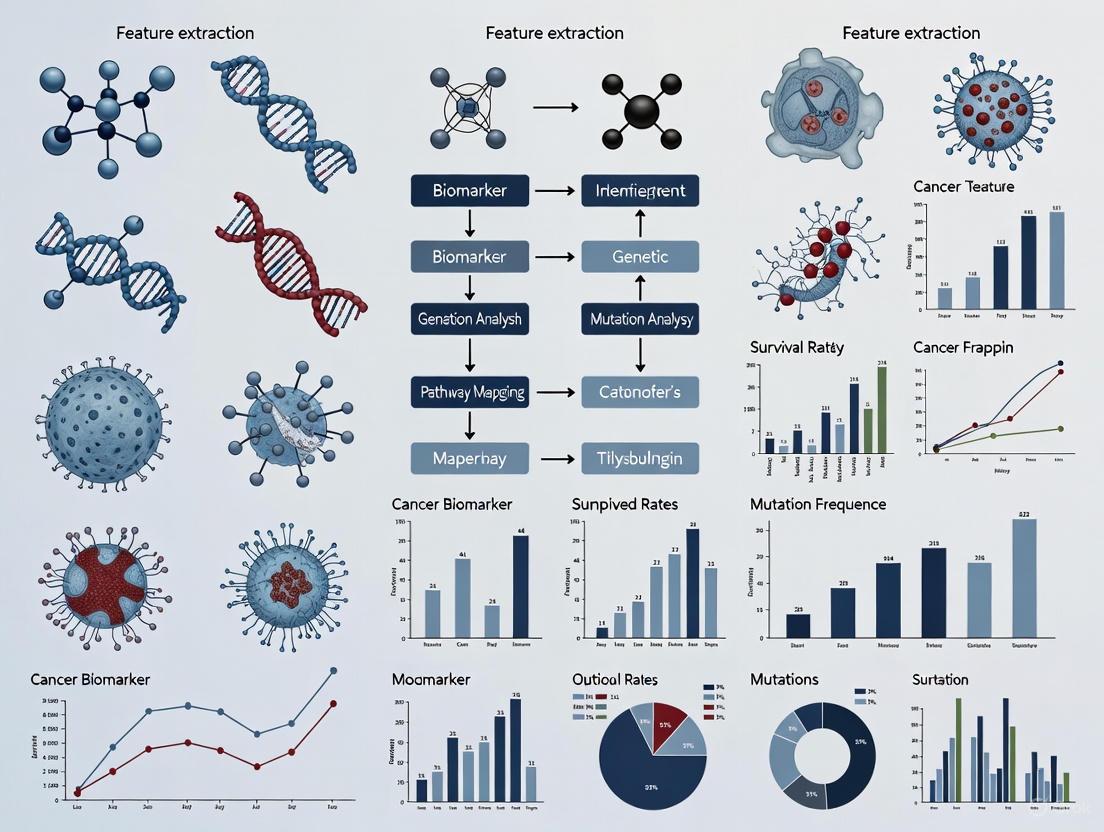

The Role of Feature Extraction in the Broader AI and Machine Learning Pipeline for Oncology

Feature extraction serves as a critical foundational step in the application of artificial intelligence (AI) to oncology, enabling the transformation of complex, high-dimensional medical data into actionable insights. This process involves identifying and isolating the most relevant patterns, textures, and statistical descriptors from raw data sources—including medical images, genomic sequences, and clinical text—to create optimized inputs for machine learning models [17] [18]. In cancer research and clinical practice, effective feature extraction bridges the gap between data acquisition and model development, allowing for more accurate detection, classification, and prognosis prediction across various cancer types [19] [20].

The growing importance of feature extraction is driven by the expanding volume and diversity of oncology data. As the field moves toward multimodal AI (MMAI) approaches that integrate histopathology, genomics, radiomics, and clinical records, the ability to extract and fuse meaningful features from these disparate sources has become increasingly vital for capturing the complex biological reality of cancer [21] [20]. This technical note examines current methodologies, applications, and experimental protocols that demonstrate how feature extraction advances oncology research and clinical care.

Current Methodologies and Applications

Hybrid Feature Extraction in Medical Imaging

Hybrid feature extraction techniques that combine handcrafted radiomic features with deep learning-based representations have demonstrated remarkable performance in cancer detection from medical images. In breast cancer research, one study implemented a comprehensive pipeline that integrated handcrafted features from multiple textual analysis methods with a deep learning classifier [17]. The methodology achieved 97.14% accuracy on the MIAS mammography dataset, outperforming benchmark models [17].

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Hybrid Feature Extraction for Breast Cancer Classification

| Metric | Result | Comparison to Benchmarks |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | 97.14% | Superior |

| Sensitivity | High (Precise value not reported) | Improved |

| Specificity | High (Precise value not reported) | Improved |

| Dataset | MIAS | Standard benchmark |

| Key Innovation | GLCM + GLRLM + 1st-order statistics + 2D BiLSTM-CNN | Outperformed single-modality approaches |

Similar approaches have been successfully applied across other cancer types. For cervical cancer detection, a framework integrating a Neural Feature Extractor based on VGG16 with an AutoInt model achieved 99.96% accuracy using a K-Nearest Neighbors classifier [22]. These results highlight how hybrid methods leverage both human expertise (through carefully designed feature extractors) and the pattern recognition capabilities of deep learning.

Multimodal Data Integration

Beyond single data modalities, feature extraction enables the fusion of heterogeneous data types to create more comprehensive disease representations. MMAI approaches integrate features derived from histopathology images, genomic profiles, clinical records, and medical imaging to capture complementary aspects of tumor biology [21]. For example, the Pathomic Fusion strategy combines histology and genomic features to improve risk stratification in glioma and clear-cell renal-cell carcinoma, outperforming the World Health Organization 2021 classification standards [21].

In translational applications, Flatiron Health research demonstrated that large language models (LLMs) could extract cancer progression events from unstructured electronic health records (EHRs) with F1 scores similar to expert human abstractors [23]. This approach enables scalable extraction of real-world progression events across multiple cancer types, producing nearly identical real-world progression-free survival estimates compared to manual abstraction [23].

Table 2: Applications of Feature Extraction Across Cancer Types

| Cancer Type | Feature Extraction Method | Application | Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Breast Cancer | GLCM, GLRLM, 1st-order statistics + 2D BiLSTM-CNN | Mammogram classification | 97.14% accuracy [17] |

| Cervical Cancer | Neural Feature Extractor (VGG16) + AutoInt | Image classification | 99.96% accuracy [22] |

| Multiple Cancers | LLM-based NLP | Progression event extraction from EHRs | F1 scores similar to human experts [23] |

| Bone Cancer | GLCM, LBP + CNN | Scan image classification | High accuracy (precise value not reported) [18] |

| Glioma & Renal Cell Carcinoma | Pathomic Fusion (histology + genomics) | Risk stratification | Outperformed WHO 2021 classification [21] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Hybrid Feature Extraction from Mammograms for Breast Cancer Classification

This protocol outlines the methodology for implementing a hybrid feature extraction and classification system for mammogram analysis, based on published research achieving 97.14% accuracy [17].

Materials and Equipment

- Dataset: Mammogram images (e.g., MIAS database)

- Processing Tools: MATLAB or Python with OpenCV/library

- Feature Extraction: Shearlet Transform toolkit, GLCM and GLRLM algorithms

- Classification Framework: Deep learning platform (e.g., TensorFlow, PyTorch) with BiLSTM-CNN implementation

Procedure

Step 1: Image Preprocessing

- Apply Shearlet Transform for image enhancement and noise reduction

- Normalize image intensity values across the dataset

- Resize images to standardized dimensions for consistent processing

Step 2: Segmentation

- Implement Improved Otsu thresholding for initial region identification

- Apply Canny edge detection to refine lesion boundaries

- Validate segmentation quality against expert annotations

Step 3: Handcrafted Feature Extraction

- Compute Gray Level Co-occurrence Matrix (GLCM) features: contrast, correlation, energy, homogeneity

- Calculate Gray Level Run Length Matrix (GLRLM) features: short-run emphasis, long-run emphasis, gray-level non-uniformity

- Extract 1st-order statistical features: mean, median, standard deviation, kurtosis, skewness of pixel intensities

- Normalize all features to zero mean and unit variance

Step 4: Deep Learning Feature Extraction and Classification

- Implement 2D BiLSTM-CNN architecture:

- CNN component: 3 convolutional layers with ReLU activation, 2 pooling layers

- BiLSTM component: 2 bidirectional LSTM layers to capture sequential patterns

- Fully connected layer with softmax activation for classification

- Train model using extracted features and corresponding labels

- Validate model performance on held-out test set

Step 5: Performance Evaluation

- Calculate accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and AUC-ROC

- Compare performance against benchmark models

- Perform statistical significance testing of improvements

Protocol 2: Multimodal Feature Integration for Cancer Subtype Classification

This protocol describes an AI architecture for cancer subtype classification from H&E-stained tissue images, based on the AEON and Paladin models that achieved 78% accuracy in subtype classification [24].

Materials and Equipment

- Dataset: Digitized H&E-stained whole slide images (WSIs)

- Annotation: OncoTree cancer classification system labels

- Computational Resources: High-performance computing cluster with GPU acceleration

- Software: Digital pathology image analysis platform (e.g., QuPath), deep learning frameworks

Procedure

Step 1: Data Preparation and Preprocessing

- Collect H&E images from approximately 80,000 tumor samples

- Apply quality control measures to exclude poor-quality images

- Perform tissue detection and segmentation to identify relevant regions

- Extract patches at multiple magnifications (e.g., 5X, 10X, 20X)

Step 2: Feature Extraction with AEON Model

- Implement AEON architecture for histologic pattern recognition

- Train model to classify cancer subtypes using OncoTree taxonomy

- Extract deep feature representations from intermediate network layers

- Generate granular subtype classifications beyond pathologist assignments

Step 3: Genomic Feature Inference with Paladin Model

- Integrate AEON-derived features with histologic images

- Train Paladin model to infer genomic variants from histologic patterns

- Identify subtype-specific genotype-phenotype relationships

- Validate inferences against molecular sequencing data

Step 4: Model Interpretation and Validation

- Apply visualization techniques to highlight histologic features driving classifications

- Compare model performance against pathologist diagnoses

- Assess clinical relevance through survival analysis of reclassified cases

- Perform external validation on independent datasets

Visualization of Methodologies

Hybrid Feature Extraction Workflow

Multimodal AI Pipeline in Oncology

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Oncology Feature Extraction

| Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function in Feature Extraction |

|---|---|---|

| Medical Imaging Datasets | MIAS (Mammography), LIDC-IDRI (Lung CT), TCIA (Multi-cancer) | Provide standardized, annotated image data for algorithm development and validation [17] [25] |

| Pathology Image Resources | The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), Camelyon Dataset | Offer whole slide images with matched clinical and genomic data for histopathology feature learning [24] [20] |

| Feature Extraction Algorithms | GLCM, GLRLM, LBP, Shearlet Transform | Generate quantitative descriptors of texture, pattern, and statistical properties from medical images [17] [18] |

| Deep Learning Architectures | 2D BiLSTM-CNN, VGG16, ResNet, Custom Transformers | Automatically learn hierarchical feature representations from raw data [17] [22] |

| Multimodal Fusion Frameworks | Pathomic Fusion, TRIDENT, ABACO | Integrate features across imaging, genomics, and clinical data modalities [21] [20] |

| Validation Frameworks | VALID Framework, Synthetic Patient Generation | Assess feature quality, model performance, and potential biases [23] [24] |

Feature extraction represents a cornerstone of the AI and machine learning pipeline in oncology, enabling the transformation of complex biomedical data into clinically actionable insights. The methodologies and protocols outlined in this technical note demonstrate how hybrid approaches—combining handcrafted radiomic features with deep learning representations—can achieve superior performance in cancer detection and classification. Furthermore, the emergence of multimodal AI systems that integrate features across diverse data types heralds a new era in precision oncology, with the potential to uncover previously inaccessible relationships between tumor characteristics, treatment responses, and patient outcomes. As these technologies continue to evolve, standardized feature extraction methodologies will play an increasingly vital role in translating algorithmic advances into improved cancer care.

Methodologies in Action: Hybrid Feature Selection, Deep Learning, and Tissue-Specific Extraction

This application note details a protocol for implementing multistage hybrid feature selection, a methodology that synergistically combines filter, wrapper, and embedded techniques to identify the most discriminative features in high-dimensional biological data. Framed within cancer detection research, this approach addresses the critical challenge of dimensionality reduction while preserving or enhancing predictive model performance. We present a validated experimental workflow that reduced feature sets from 30 to 6 for breast cancer and 15 to 8 for lung cancer data, achieving 100% accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity when coupled with a stacked generalization classifier [15] [26]. The guidelines, reagents, and visualization tools provided herein are designed to empower researchers and drug development professionals in building robust, interpretable models for early cancer detection.

In oncology, high-throughput technologies generate vast amounts of molecular and clinical data, creating a pressing need for sophisticated feature selection methods to identify the most relevant biomarkers. Hybrid feature selection methods that integrate multiple selection paradigms have demonstrated superior performance compared to individual approaches used in isolation [15]. By combining the computational efficiency of filter methods, the model-specific performance optimization of wrapper methods, and the built-in selection capabilities of embedded methods, researchers can develop minimal biomarker panels that maintain high diagnostic accuracy. This is particularly crucial for early cancer detection, where high sensitivity is required to minimize missed diagnoses and high specificity is needed to avoid unnecessary procedures [27].

Theoretical Foundation of Feature Selection Methods

Method Categories and Characteristics

Feature selection methods are broadly categorized into three distinct classes, each with unique mechanisms, advantages, and limitations, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Comparison of Feature Selection Method Categories

| Method Type | Mechanism of Action | Key Advantages | Common Techniques |

|---|---|---|---|

| Filter Methods | Selects features based on intrinsic data properties and univariate statistics [28]. |

|

|

| Wrapper Methods | Evaluates feature subsets based on classifier performance [28]. |

|

|

| Embedded Methods | Integrates feature selection directly into the model training process [28] [29]. |

|

|

The Hybrid Approach Rationale

Multistage hybrid feature selection leverages the complementary strengths of these methodologies. The typical workflow begins with filter methods for rapid, large-scale feature reduction, proceeds with wrapper methods for performance-oriented subset refinement, and concludes with embedded methods for final selection and model building. This sequential approach efficiently narrows the feature space while minimizing the risk of discarding potentially informative biomarkers [15].

Experimental Protocols

Multistage Hybrid Feature Selection Protocol for Cancer Detection

This protocol outlines the specific methodology used in a published study that achieved 100% classification performance on breast and lung cancer datasets [15] [26].

Phase 1: Initial Filter-Based Selection

Objective: Rapidly reduce feature space by identifying features highly correlated with the target class but not among themselves.

- Algorithm: Greedy stepwise search algorithm [15].

- Procedure:

- Calculate feature-class correlation for all features.

- Calculate inter-feature correlation matrix.

- Iteratively select features demonstrating:

- High correlation with the target class (e.g., cancer diagnosis)

- Low correlation with already-selected features

- Expected Outcome: Selection of 9 features from the original 30 in the Wisconsin Breast Cancer (WBC) dataset and 10 features from the Lung Cancer Prediction (LCP) dataset [15].

Phase 2: Wrapper-Based Refinement

Objective: Further refine the feature subset by optimizing for classifier performance.

- Algorithm: Best first search combined with logistic regression classifier [15].

- Procedure:

- Initialize with the feature subset from Phase 1.

- Evaluate classifier performance (e.g., accuracy, sensitivity) for all possible single-feature additions and removals.

- Greedily select the feature addition or removal that most improves performance.

- Continue until no further performance improvements are observed.

- Expected Outcome: Final selection of 6 optimal features for breast cancer detection and 8 for lung cancer detection [15].

Phase 3: Model Building with Embedded Selection

Objective: Construct a final predictive model with built-in feature selection.

- Algorithm: Stacked generalization with base classifiers (Logistic Regression, Naïve Bayes, Decision Tree) and Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) as meta-classifier [15].

- Procedure:

- Train multiple base classifiers on the refined feature subset from Phase 2.

- Use classifier predictions as input features for the meta-classifier (MLP).

- The MLP learns to optimally combine the base predictions.

- Performance Validation: Assess using data splitting (50-50, 66-34, 80-20) and 10-fold cross-validation [15].

SMAGS-LASSO Protocol for Sensitivity-Specificity Optimization

This protocol describes an embedded method designed specifically for clinical applications requiring high sensitivity at predefined specificity thresholds [27].

Objective Function and Optimization

Objective: Maximize sensitivity while maintaining a user-defined specificity threshold and performing feature selection.

- Algorithm: SMAGS-LASSO with custom loss function [27].

- Mathematical Formulation:

- Maximize: ( \sum{i=1}^{n} \hat{y}i \cdot yi / \sum{i=1}^{n} yi - \lambda \|\beta\|1 )

- Subject to: ( (1 - \mathbf{y})^T (1 - \hat{\mathbf{y}}) / (1 - \mathbf{y})^T (1 - \mathbf{y}) \geq SP )

- Where ( SP ) is the predefined specificity threshold, ( \lambda ) is the regularization parameter, and ( \|\beta\|_1 ) is the L1-norm of coefficients [27].

- Optimization Procedure:

- Initialize coefficients using standard logistic regression.

- Apply multiple optimization algorithms (Nelder-Mead, BFGS, CG, L-BFGS-B) in parallel.

- Select the model with the highest sensitivity among converged solutions [27].

Cross-Validation Framework

Objective: Select the optimal regularization parameter ( \lambda ).

- Procedure:

- Create k-fold partitions of the data (typically k=5).

- Evaluate a sequence of ( \lambda ) values on each fold.

- Measure performance using sensitivity mean squared error (MSE):

- ( MSE{sensitivity} = (1 - \sum{i=1}^{n} \hat{y}i \cdot yi / \sum{i=1}^{n} yi)^2 ) [27].

- Select the ( \lambda ) value that minimizes sensitivity MSE while maintaining the desired specificity.

Data Presentation and Performance Metrics

Quantitative Performance of Hybrid Feature Selection

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Multistage Hybrid Feature Selection on Cancer Datasets

| Dataset | Original Features | Selected Features | Accuracy | Sensitivity | Specificity | AUC | Classifier |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBC (Breast) | 30 | 6 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | Stacked (LR+NB+DT/MLP) [15] |

| LCP (Lung) | 15 | 8 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | Stacked (LR+NB+DT/MLP) [15] |

| Colorectal Cancer | 100+ | Not specified | 21.8% improvement over LASSO | 1.00 (at 99.9% specificity) | 99.9% | Significantly improved | SMAGS-LASSO [27] |

Comparative Performance Across Method Types

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Feature Selection Methods in Cancer Detection

| Method Category | Computational Cost | Model Specificity | Risk of Overfitting | Interpretability | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Filter Methods | Low | Model-agnostic | Low | High | Initial feature screening on large datasets [30] |

| Wrapper Methods | High | Model-specific | High | Medium | Final feature tuning on smaller datasets [30] |

| Embedded Methods | Medium | Model-specific | Medium | Medium | Integrated model building and selection [29] |

| Hybrid Methods | Varies by stage | Balanced approach | Low with proper validation | High with explainability tools | Critical applications like cancer detection [15] |

Visualization of Workflows

Multistage Hybrid Feature Selection Workflow

Stacked Generalization Classifier Architecture

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions for Implementation

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools and Datasets for Hybrid Feature Selection

| Resource Category | Specific Tool/Dataset | Function/Purpose | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Programming Environments | Python with scikit-learn | Primary implementation platform for feature selection algorithms and machine learning models [29]. | from sklearn.feature_selection import SelectFromModel |

| Feature Selection Algorithms | Greedy Stepwise Search (Filter) | Initial feature screening based on statistical properties [15]. | Custom implementation based on correlation thresholds |

| Best First Search (Wrapper) | Performance-based feature subset refinement [15]. | SequentialFeatureSelector from specialized libraries |

|

| LASSO Regularization (Embedded) | Integrated feature selection during linear model training [27] [29]. | LogisticRegression(penalty='l1', solver='liblinear') |

|

| Benchmark Datasets | Wisconsin Breast Cancer (WBC) | Publicly available benchmark for breast cancer classification [15]. | UCI Machine Learning Repository dataset |

| Lung Cancer Prediction (LCP) | Benchmark dataset for lung cancer detection studies [15]. | Kaggle Machine Learning repository dataset | |

| Model Interpretation Tools | SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) | Explains model predictions by quantifying feature contributions [15]. | Python SHAP library for model explainability |

| LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations) | Creates local explanations for individual predictions [15]. | Python LIME package for interpretability |

Multistage hybrid feature selection represents a powerful paradigm for biomarker discovery in cancer detection research. By systematically combining filter, wrapper, and embedded methods, researchers can navigate high-dimensional data spaces to identify minimal feature subsets that maximize diagnostic performance. The protocols and workflows presented herein have been empirically validated to achieve perfect classification metrics on benchmark cancer datasets, providing a robust methodology for researchers and drug development professionals. Future directions include adapting these approaches to multi-omics data integration and addressing emerging challenges in explainable AI for clinical adoption.

The integration of advanced deep learning architectures has significantly progressed automated feature extraction in medical image analysis, leading to enhanced capabilities in cancer detection and diagnosis. This document details the application notes and experimental protocols for utilizing Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), Vision Transformers (ViTs), and Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BiLSTM) networks within oncology research. These architectures excel at extracting complementary features: CNNs capture localized spatial patterns, ViTs model long-range contextual dependencies, and BiLSTMs learn sequential relationships in feature maps. Their standalone and hybrid implementations have demonstrated state-of-the-art performance across various cancer types, including lung, colon, breast, and skin cancers, as summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Performance Summary of Deep Learning Architectures in Cancer Detection

| Cancer Type | Architecture | Dataset | Key Performance Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lung & Colon Cancer | ViT-DCNN (Hybrid) | Lung & Colon Cancer Histopathological | Accuracy: 94.24%, Precision: 94.37%, Recall: 94.24%, F1-Score: 94.23% | [31] |

| Breast Cancer | 2D BiLSTM-CNN (Hybrid) | MIAS | Accuracy: 97.14% | [17] |

| Breast Cancer | Hybrid ViT-CNN (Federated) | Multi-institutional Risk Factors | Accuracy: 98.65% (Binary), 97.30% (Multi-class) | [32] |

| Skin Lesion | CNN-BiLSTM with Attention | ISIC, HAM10000 | Accuracy: 92.73%, Precision: 92.84%, Recall: 92.73% | [33] |

| Skin Cancer | HQCNN-BiLSTM-MobileNetV2 | Clinical Skin Cancer | Test Accuracy: 89.3%, Recall: 94.33% (Malignant) | [34] |

| Cervical Cancer | VGG16 (CNN) + ML Classifiers | Cervical Cancer Image | Accuracy: 99.96% (KNN) | [22] |

| Chest X-ray (Pneumonia) | ResNet-50 (CNN) | Chest X-ray Pneumonia | Accuracy: 98.37% | [35] |

| Brain Tumor (MRI) | DeiT-Small (ViT) | Brain Tumor MRI | Accuracy: 92.16% | [35] |

Application Notes: Architectural Strengths and Cancer-Specific Implementations

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs)

CNNs remain a foundational tool for extracting hierarchical spatial features from medical images. Their inductive bias towards processing pixel locality makes them highly effective for identifying patterns like edges, textures, and morphological structures in tissue samples.

- Key Applications: CNNs are widely used for classification and segmentation tasks across various imaging modalities, including histopathology, mammography, and dermoscopy [36] [37]. For instance, pre-trained CNNs like VGG16 and ResNet-50 are frequently employed as powerful feature extractors, with the extracted features subsequently fed into classical machine learning classifiers for cervical cancer diagnosis, achieving near-perfect accuracy [22].

- Strengths: CNNs are highly efficient at learning localized, translation-invariant features and have a proven track record of high performance on a wide range of medical image classification tasks [35].

Vision Transformers (ViTs)

ViTs process images as sequences of patches, using a self-attention mechanism to weigh the importance of different patches relative to each other. This allows them to capture global contextual information across the entire image.

- Key Applications: ViTs have shown remarkable success in classifying breast cancer from mammograms and risk factor data, as well as in histopathological image analysis [36] [32]. Their ability to model long-range dependencies is particularly beneficial for understanding complex spatial relationships in heterogeneous tumor microenvironments.

- Strengths: The self-attention mechanism provides a global receptive field from the first layer, enabling the model to integrate information from disparate image regions simultaneously. This often leads to superior performance in tasks where global context is critical [31] [35].

Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BiLSTM) Networks

BiLSTMs are a type of recurrent neural network designed to model sequential data by processing it in both forward and backward directions. This allows the network to capture temporal or spatial dependencies from both past and future contexts in a sequence.

- Key Applications: In cancer image analysis, BiLSTMs are not typically used on raw pixels but on sequences of extracted features. They are highly effective for modeling the spatial evolution of features across an image or for learning dependencies in feature vectors. They have been successfully integrated with CNNs for breast cancer detection from mammograms and skin lesion classification, where they help in capturing complex, distributed patterns [33] [17] [34].

- Strengths: BiLSTMs excel at learning long-range, bidirectional dependencies in sequential data, which, when applied to feature sequences, can improve the model's contextual understanding and classification accuracy [33].

Hybrid Architectures

Hybrid models combine the strengths of two or more architectures to overcome the limitations of individual components, often yielding state-of-the-art results.

- ViT-DCNN for Lung and Colon Cancer: This model integrates a Vision Transformer with a Deformable CNN. The ViT captures global contextual information through self-attention, while the Deformable CNN adapts its receptive field to capture fine-grained, localized spatial details in histopathological images. A Hierarchical Feature Fusion (HFF) module with a Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) block is used to effectively combine these global and local features [31].

- CNN-BiLSTM for Skin and Breast Cancer: These hybrids use a CNN as a powerful feature extractor to generate a sequence of high-level spatial feature maps. A BiLSTM then processes this sequence to capture the contextual relationships between these features, improving the model's ability to classify complex lesions in skin and breast tissues [33] [17].

- ViT-CNN for Breast Cancer Prediction: This hybrid leverages both global features from a ViT and local features from a CNN, combining them to create a more robust representation for classification. This approach has been effectively deployed within a federated learning framework to enhance data privacy [32].

Table 2: The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources

| Item Name | Function/Application | Specification Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Lung & Colon Cancer Histopathological Dataset | Model training & validation for lung/colon cancer detection | Comprises 5 classes: colon adenocarcinoma, colon normal, lung adenocarcinoma, lung normal, lung squamous cell carcinoma [31] |

| MIAS Dataset (Mammography) | Benchmark for breast cancer detection algorithm development | Contains cranio-caudal (CC) and mediolateral-oblique (MLO) view mammograms [17] |

| HAM10000 / ISIC Datasets | Training & testing for skin lesion analysis | Large collection of dermoscopic images; includes benign and malignant lesion types [33] [35] |

| Pre-trained Model Weights (e.g., ImageNet) | Transfer learning initialization | Speeds up convergence and improves performance, especially with limited data [35] |

| Shearlet Transform | Image preprocessing for enhancement | Superior to wavelets for representing edges and other singularities in mammograms [17] |

| Gray Level Co-occurrence Matrix (GLCM) | Handcrafted texture feature extraction | Captures second-order statistical texture information [17] |

| AdamW Optimizer | Model parameter optimization | Modifies weight decay for more effective training regularization [31] |

| Explainable AI (XAI) Tools (LIME, SHAP) | Model interpretability and validation | Provides post-hoc explanations for model predictions, crucial for clinical trust [38] [32] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Implementing a ViT-DCNN Hybrid for Histopathological Cancer Detection

This protocol outlines the methodology for reproducing the ViT-DCNN model for lung and colon cancer classification from histopathological images [31].

2.1.1 Workflow Overview

The diagram below illustrates the integrated experimental workflow for hybrid model development.

2.1.2 Materials and Data Preparation

- Dataset: Obtain the Lung and Colon Cancer Histopathological Images dataset, which includes five classes (e.g., colon adenocarcinoma, colon normal, lung adenocarcinoma) [31].

- Data Splitting: Partition the dataset into training (80%), validation (10%), and testing (10%) subsets using stratified sampling to maintain class distribution.

- Image Preprocessing:

- Resizing: Resize all images to 224x224 pixels using a library such as OpenCV.

- Normalization: Apply min-max normalization to scale pixel values to a range of [0, 1].

- Data Augmentation: On the training set, apply random rotations, zooming, and horizontal/vertical flipping to increase data diversity and reduce overfitting.

2.1.3 Model Architecture and Training

- ViT Path: Implement a standard Vision Transformer. Split the preprocessed image into fixed-size patches (e.g., 16x16), linearly embed them, add positional embeddings, and process them through a series of transformer encoder blocks with multi-head self-attention to extract global features [31].

- DCNN Path: Implement a Convolutional Neural Network with deformable convolutions. These convolutions learn adaptive receptive fields by adding 2D offsets to the regular grid sampling locations, allowing the model to focus on more informative and irregularly shaped regions for fine-grained feature extraction [31].

- Feature Fusion: Design a Hierarchical Feature Fusion (HFF) module to combine the global feature maps from the ViT and the local feature maps from the DCNN. Incorporate a Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) block within this module to explicitly model channel-wise dependencies and recalibrate feature responses adaptively.

- Classifier Head: Pass the fused feature vector through one or more fully connected layers with a softmax activation function to generate the final class probabilities.

- Training Configuration:

- Optimizer: Use the AdamW optimizer with a learning rate of 1e-5.

- Loss Function: Use Categorical Cross-Entropy loss.

- Regularization: Implement early stopping by monitoring the validation accuracy with a patience of 5 epochs. Train for a maximum of 50 epochs.

2.1.4 Evaluation and Analysis

- Performance Metrics: Calculate accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score on the held-out test set.

- Model Interpretation: Utilize Explainable AI (XAI) techniques such as Grad-CAM or attention visualization to highlight the image regions most influential in the model's decision-making process, thereby enhancing clinical interpretability [38].

Protocol: Implementing a CNN-BiLSTM Model with Attention for Skin Lesion Classification

This protocol details the steps for building a hybrid CNN-BiLSTM model augmented with attention mechanisms for skin lesion classification, as demonstrated in [33].

2.2.1 Workflow Overview

The following diagram outlines the sequential flow of data through the CNN-BiLSTM-Attention architecture.

2.2.2 Materials and Data Preparation

- Dataset: Utilize a publicly available skin lesion dataset such as ISIC or HAM10000.

- Data Preprocessing: Follow a similar resizing and normalization procedure as in Protocol 2.1.2, ensuring consistency with the input size expected by the chosen CNN backbone.

2.2.3 Model Architecture and Training

- CNN Feature Extraction: Use a pre-trained CNN (e.g., VGG16, InceptionResNetV2) with its classification head removed as a feature extractor. This backbone processes the input image and outputs a 3D feature map (height, width, channels).

- Sequence Formation: Flatten the spatial dimensions (height, width) of the feature map to convert it into a sequence of feature vectors. Each vector in the sequence corresponds to a specific spatial region in the original feature map.

- BiLSTM Processing: Feed this sequence of feature vectors into a BiLSTM layer. The BiLSTM processes the sequence in both forward and backward directions, capturing rich contextual relationships between different spatial regions of the feature map.

- Attention Mechanism: Implement an attention layer (spatial, channel, and/or temporal) on top of the BiLSTM's output sequence. This layer learns to assign different weights to each time step (spatial region) in the sequence, allowing the model to focus on the most discriminative parts of the feature map when making a classification decision. The output is a weighted sum of the BiLSTM hidden states, known as a context vector.

- Classification: Pass the final context vector through a fully connected layer with softmax activation to produce classification probabilities.

- Training Configuration:

- Use the Adam optimizer with a learning rate scheduler (e.g., ReduceLROnPlateau).

- Use Categorical Cross-Entropy loss.

- Employ data augmentation and dropout for regularization.

2.2.4 Evaluation

- Evaluate the model on a standard test set, reporting accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and more specialized metrics like Jaccard Index (JAC) and Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) [33].

- Visualize the attention weights to understand which regions of the lesion the model deems most important, providing valuable insights for clinicians.

Within the broader thesis on feature extraction techniques for cancer detection, this document details the application and protocols for extracting Tissue-Energy Specific Characteristic Features (TFs) from computed tomography (CT) scans. Traditional feature extraction methods in medical imaging, such as handcrafted texture features (HFs) and deep learning-based abstract features (DFs), often rely on image patterns alone [39]. In contrast, the TF extraction method is grounded in the fundamental physics of CT imaging, specifically the interactions between lesion tissues and the polyenergetic X-ray spectrum [39]. This approach aims to derive features that are directly related to the underlying tissue biology by leveraging energy-resolved CT data, thereby providing a more robust and physiologically relevant set of features for cancer detection and characterization.

Comparative Performance of Feature Extraction Techniques

Experimental evidence underscores the superior diagnostic performance of TFs compared to other feature classes. The following table summarizes the performance, as measured by the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC), of four different methodologies across three distinct lesion datasets [39].

Table 1: Comparative performance of feature extraction and classification methods for lesion diagnosis.

| Methodology | Dataset 1 AUC | Dataset 2 AUC | Dataset 3 AUC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Haralick Texture Features (HFs) + RF | 0.724 | 0.806 | 0.878 |

| Deep Learning Features (DFs) + RF | 0.652 | 0.863 | 0.965 |

| Deep Learning CNN (End-to-End) | 0.694 | 0.895 | 0.964 |

| Tissue-Energy Features (TFs) + RF | 0.985 | 0.993 | 0.996 |

The results consistently demonstrate that the extraction of tissue-energy specific characteristic features dramatically improved the AUC value, significantly outperforming both image-texture and deep-learning-based abstract features [39]. This leads to the conclusion that the feature extraction module is more critical than the classification module in a machine learning pipeline, and that extracting biologically relevant features like TFs is more important than extracting image-abstractive features [39].

Protocols for Tissue-Energy Specific Characteristic Feature (TF) Extraction

The extraction of TFs is a multi-stage process that transforms conventional CT images into virtual monoenergetic images (VMIs) and subsequently extracts tissue-specific characteristics using a biological model. The overall workflow is illustrated below.

Protocol 1: Generation of Virtual Monoenergetic Images (VMIs)

Objective: To generate a set of VMIs from a conventional CT scan at multiple discrete energy levels.

Background: Conventional CT images are reconstructed from raw data acquired from an X-ray tube emitting a wide spectrum of energies, resulting in an image that is an average across this spectrum [39]. Since tissue contrast varies with X-ray energy, VMIs are computed to simulate what the CT image would look like if the scan were performed at a single, specific X-ray energy [39]. This improves tissue characterization by providing energy-resolved data.

Materials and Reagents:

- Input Data: A non-contrast or contrast-enhanced CT scan in DICOM format.

- Software: A software platform capable of generating VMIs, often available through advanced scanner software or third-party research toolkits.

Methodology:

- Data Input: Load the raw projection data or the reconstructed CT image series with its associated sinogram data into the VMI generation software.

- Spectral Modeling: Use the known spectral profile of the CT scanner's X-ray tube and the tissue attenuation properties to create a model that decomposes the polyenergetic signal.

- Energy Level Selection: Define a range of virtual energy levels for VMI reconstruction. A typical range might be from 40 keV to 140 keV in 5-10 keV increments. Lower energies (e.g., 40-70 keV) generally provide higher soft-tissue contrast, while higher energies (e.g., 100-140 keV) reduce beam-hardening artifacts.

- Image Reconstruction: Execute the algorithm to generate a series of VMI sets, each corresponding to one of the selected discrete energy levels.

Validation:

- Qualitatively assess VMIs by ensuring expected tissue contrast changes across energy levels (e.g., iodine contrast increases at lower keV).

- Quantitatively verify the mean and standard deviation of Hounsfield Units (HU) in a region-of-interest (ROI) placed in a reference tissue (e.g., blood, water) across different VMIs.

Protocol 2: Extraction of Tissue-Energy Specific Characteristic Features

Objective: To compute quantitative TFs from the generated VMIs using a tissue biological model.

Background: This protocol uses a tissue elasticity model to compute characteristic features from each VMI [39]. The underlying principle is that the energy-dependent attenuation properties of tissues are influenced by their fundamental biological composition, which can be parameterized.

Materials and Reagents:

- Input Data: The set of VMIs generated in Protocol 1.

- Segmentation Mask: A binary mask defining the volumetric region of interest (ROI), such as a pulmonary nodule or colorectal polyp, typically derived from manual or semi-automated segmentation.