Accelerating Drug Discovery: A Comprehensive Guide to Active Learning for Virtual Screening Optimization

This article provides a detailed exploration of active learning (AL) strategies for optimizing virtual screening (VS) in early-stage drug discovery.

Accelerating Drug Discovery: A Comprehensive Guide to Active Learning for Virtual Screening Optimization

Abstract

This article provides a detailed exploration of active learning (AL) strategies for optimizing virtual screening (VS) in early-stage drug discovery. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles of AL, the transition from traditional VS methods, and the critical role of molecular representations. It then details core AL methodologies and their practical application, followed by a troubleshooting guide addressing common challenges like the cold start problem and model bias. Finally, it presents a framework for validating AL-VS campaigns through benchmarking and real-world case studies. The article synthesizes key insights to empower research teams to implement efficient, data-driven screening pipelines.

Active Learning 101: The Foundational Shift in Virtual Screening Strategy

Welcome to the Technical Support Center for Active Learning-Driven Virtual Screening (AL-VS). This resource addresses common challenges researchers face when transitioning from traditional, high-cost virtual screening to optimized, iterative AL-VS protocols.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: Our AL-VS cycle seems to have stalled. The model's predictions are no longer identifying diverse or potent hits. What could be wrong? A1: This is often a problem of "Exploration-Exploitation Imbalance."

- Check: The acquisition function parameters. A pure "expected improvement" strategy may over-exploit.

- Action: Switch to an acquisition function that balances exploration (e.g., Upper Confidence Bound - UCB) or introduce a random fraction (e.g., 10%) of samples chosen for maximum diversity in the next batch.

- Protocol: Implement a "Cycle Diagnostic":

- Plot the average predicted activity and the standard deviation of the selected compounds over consecutive cycles.

- If the standard deviation collapses while predicted activity plateaus, exploration is insufficient.

- Adjust the beta parameter in UCB (β controls exploration weight) or the epsilon in epsilon-greedy strategies.

Q2: How do we handle the "cold start" problem? Our initial labeled set (HTS data) is very small (< 100 actives). A2: A small seed set requires strategic initialization.

- Check: The chemical diversity of your initial actives.

- Action: Use unsupervised pre-training or a diverse negative set.

- Protocol: "Seed Set Augmentation with Unlabeled Data"

- Cluster your entire unlabeled library (e.g., 1M compounds) using Morgan fingerprints and k-means.

- From each of the N largest clusters, select the compound closest to the cluster centroid.

- Screen this diverse subset (size N) experimentally. This ensures the initial training data covers a broader chemical space, providing a better foundation for the first AL model.

Q3: Integration of disparate data sources (e.g., HTS, legacy bioassay data, literature IC50s) is causing model performance degradation. A3: This is a data heterogeneity issue. Do not merge labels directly.

- Check: The distribution and units of activity measurements from each source.

- Action: Use a multi-task or transfer learning framework.

- Protocol: "Multi-Task Learning for Data Integration"

- Frame each data source as a related but separate prediction task.

- Use a neural network architecture with shared hidden layers (learning common features) and task-specific output heads.

- Train initially on all available data. For the primary screening campaign, use the prediction head fine-tuned on the most reliable data source (e.g., your internal HTS).

Key Experimental Protocols Cited

Protocol 1: Standard AL-VS Cycle

- Seed: Start with a small, labeled dataset L (actives/inactives).

- Train: Train a machine learning model (e.g., Random Forest, GNN) on L to predict activity.

- Predict: Use the model to score the large, unlabeled pool U.

- Acquire: Apply an acquisition function (e.g., Expected Improvement, Thompson Sampling) to select a batch B (e.g., 50-100 compounds) from U.

- Experiment: In vitro/vitro screen batch B to obtain true labels.

- Augment: Add the newly labeled batch B to L (L = L ∪ B).

- Repeat: Return to Step 2 for a predefined number of cycles or until a performance metric is met.

Protocol 2: Evaluating AL-VS Performance vs. Traditional Screening

- Baseline: Simulate a traditional high-throughput screen (HTS) by randomly selecting compounds from the full library. Plot the cumulative number of actives found vs. total compounds screened.

- AL Simulation: Run a retrospective AL-VS simulation using historical data. On the same plot, chart the cumulative actives found by the AL model's selections.

- Metric Calculation: Calculate the Enrichment Factor (EF) at 1% of the library screened.

EF = (Hit_rate_in_top_1% / Overall_hit_rate_in_library) - Compare: The AL-VS curve should rise significantly earlier and steeper than the random baseline. A higher EF demonstrates efficiency.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Virtual Screening Strategies (Retrospective Study)

| Screening Strategy | Total Compounds Screened | Actives Identified | Enrichment Factor (EF@1%) | Estimated Wet-Lab Cost* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random HTS (Baseline) | 100,000 | 250 | 1.0 | $1,500,000 |

| Traditional Docking | 10,000 (Top Ranked) | 100 | 5.0 | $150,000 |

| Active Learning (ML-VS) | 2,500 (Iterative) | 150 | 24.0 | $37,500 |

Note: Cost estimates are illustrative, assuming ~$15 per compound for assay materials and labor.

Table 2: Common Acquisition Functions in AL-VS

| Function | Formula (Conceptual) | Pros | Cons | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expected Improvement (EI) | E[ max(0, Score - BestSoFar) ] | Focuses on potency. | Can get stuck in local maxima. | Hit optimization stages. |

| Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) | Mean Prediction + β * StdDev | Explicit exploration parameter (β). | Requires tuning of β. | Balanced exploration/exploitation. |

| Thompson Sampling | Random draw from posterior predictive distribution | Naturally balances diversity. | Computationally can be heavier. | Very small initial datasets. |

Visualizations

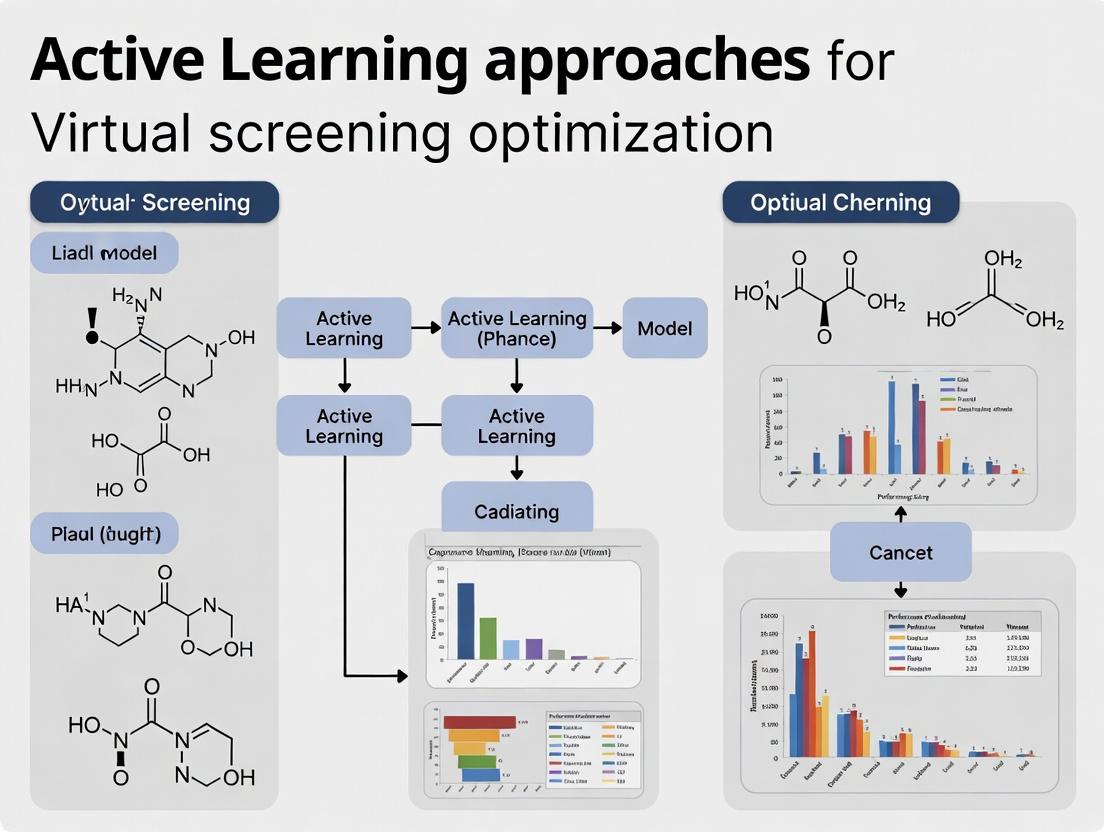

Diagram 1: Active Learning vs Traditional Screening Workflow

Diagram 2: The AL-VS Feedback Loop

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in AL-VS Context | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| High-Throughput Assay Kit | Enables rapid experimental labeling of compounds selected by the AL model. | Fluorescence- or luminescence-based biochemical assay (e.g., kinase, protease). |

| Chemical Diversity Library | The large, unlabeled pool (U) of compounds for exploration. | Commercially available libraries (e.g., Enamine REAL, ChemDiv) with 1M+ compounds. |

| ML/Docking Software Suite | Core platform for building predictive models and initial scoring. | Python/RDKit for ML; AutoDock Vina, Schrödinger Suite for docking. |

| Acquisition Function Code | Algorithmic core that decides which compounds to test next. | Custom Python scripts implementing UCB, EI, or Thompson Sampling. |

| Chemical Descriptors | Numerical representations of molecules for the ML model. | ECFP/Morgan fingerprints, RDKit descriptors, or learned graph embeddings. |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: Our Active Learning loop seems to be stuck, repeatedly selecting similar compounds from the pool without improving model performance. What could be the cause?

A: This is often a symptom of acquisition function collapse or poor exploration/exploitation balance.

- Check 1: Acquisition Function. If using uncertainty sampling, the model may be overconfident on a region of chemical space. Switch to a more exploratory function like Thompson Sampling or Expected Improvement, or implement a hybrid query strategy.

- Check 2: Diversity Metrics. Incorporate a diversity penalty into your selection criteria. A common fix is to use Cluster-Centric Selection: cluster the unlabeled pool and select the top-K uncertain compounds from each cluster. This ensures spatial coverage.

- Check 3: Model Decay. Retrain your primary predictor from scratch every few cycles to avoid reinforcing biases from continuously updated models.

Q2: The computational cost of iteratively retraining our deep learning model on growing datasets is becoming prohibitive. How can we optimize this?

A: Implement a multi-fidelity modeling strategy within the loop.

- Protocol: Maintain two models: a fast, less accurate surrogate (e.g., Random Forest, shallow NN) and a high-fidelity target model (e.g., Graph Neural Network).

- Step 1: Use the surrogate model to screen the entire unlabeled pool and propose a candidate set.

- Step 2: Apply the high-fidelity model only to this much smaller candidate set to make the final selection for experimental testing.

- Step 3: Retrain the surrogate model every cycle. Retrain the high-fidelity model only every 3-5 cycles.

- Expected Outcome: This can reduce total training compute time by 60-80% while maintaining >95% of the performance gain of full retraining.

Q3: How do we handle inconsistent or noisy experimental data (e.g., bioassay results) within the Active Learning cycle?

A: Noise can destabilize the learning loop. Implement a robust validation and data cleaning protocol.

- Pre-query Duplication: For selected compounds, request experimental replicates (n=3) to establish a consensus activity value.

- Post-hoc Outlier Detection: Use statistical methods (e.g., Grubbs' test) on new data points before adding them to the training set. Flag compounds where replicate variance exceeds a threshold (e.g., >30% of signal range) for retesting.

- Model Adjustment: Consider switching to probabilistic models (e.g., Gaussian Processes) or loss functions robust to label noise.

Q4: What is a practical stopping criterion for an Active Learning campaign in virtual screening?

A: Predefine quantitative metrics to avoid open-ended cycles. Common stopping criteria include:

| Criterion | Calculation | Target Threshold (Example) |

|---|---|---|

| Performance Plateau | Moving average of enrichment factor (EF₁%) over last 3 cycles | < 5% relative improvement |

| Acquisition Stability | Jaccard similarity between consecutive acquisition batches | > 0.7 |

| Maximum Yield | Number of confirmed active compounds identified | > 50 |

| Resource Exhaustion | Budget (cycles, computational cost, experimental slots) exhausted | N/A |

Q5: Our initial labeled set (seed data) is very small and potentially biased. How do we bootstrap the loop effectively?

A: A poor seed set can lead to initial divergence. Use unsupervised pre-screening.

- Methodology:

- Perform k-means or Taylor-Butina clustering on your entire compound library based on molecular fingerprints (ECFP4).

- From each of the k clusters, randomly select 1-2 compounds to create a diverse seed set of size n (where n = 2k).

- Test this diverse set experimentally to create your initial labeled data.

- Proceed with standard Active Learning.

- Key Benefit: This ensures the initial model has at least some information about the major regions of chemical space, improving early-cycle stability.

Experimental Protocol: Standard Active Learning Cycle for Virtual Screening

Title: Iterative Cycle for Lead Identification Optimization.

Objective: To efficiently identify novel active compounds from a large virtual library using an iterative, model-guided selection process.

Materials: See "The Scientist's Toolkit" below.

Procedure:

- Seed Preparation: Assemble initial labeled dataset

L_0(50-200 compounds with confirmed activity/inactivity). - Model Training: Train a machine learning model (e.g., Gradient Boosting Classifier) on

L_0to predict bioactivity. - Pool Screening: Use the trained model to predict activity probabilities for all compounds in the large unlabeled pool

U. - Acquisition: Apply the acquisition function (e.g.,

Top-Kby predicted probability +K-Meansdiversity filter) to select the next batchB(e.g., 20-50 compounds) fromU. - Experimental Assay: Test batch

Bin the relevant biological assay to obtain confirmed labels. - Data Augmentation: Remove

BfromUand add the newly labeledBto the training set:L_i = L_{i-1} + B. - Iteration: Repeat steps 2-6 until a predefined stopping criterion is met (see FAQ Q4).

- Validation: Evaluate the final model's performance on a held-out test set and confirm the activity of top-ranked novel hits from the final cycle.

Diagrams

Title: Active Learning Workflow for Virtual Screening

Title: Multi-Fidelity Model Efficiency Pipeline

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Active Learning for VS |

|---|---|

| ECFP4 / RDKit Fingerprints | Molecular representation to convert chemical structures into bit vectors for model input. |

| Scikit-learn / XGBoost | Provides robust, fast baseline models (Random Forest, GBM) for initial cycles and surrogate models. |

| DeepChem / DGL-LifeSci | Frameworks for building high-fidelity Graph Neural Network (GNN) models to capture complex structure-activity relationships. |

| ModAL (Active Learning Lib) | Python library specifically for building Active Learning loops, with built-in query strategies. |

| KNIME or Pipeline Pilot | Visual workflow tools to orchestrate data flow between modeling, database, and experimental systems. |

| High-Throughput Screening (HTS) Assay | The biological experiment providing the "oracle" labels (e.g., % inhibition, IC50) for selected compounds. |

| Compound Management System | Database (e.g., using CDD Vault, GOSTAR) to track chemical structures, batches, and experimental data across cycles. |

| Docker / Singularity | Containerization to ensure model training and evaluation environments are reproducible across cycles and team members. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: My acquisition function selects highly similar compounds in each AL cycle, reducing chemical diversity. How can I fix this? A: This indicates a potential collapse in your model's uncertainty estimates or an issue with the query strategy. Implement a hybrid query strategy that combines uncertainty sampling with a diversity metric, such as Max-Min Distance or cluster-based sampling. Pre-calculate molecular fingerprint diversity (e.g., using Tanimoto similarity on ECFP4 fingerprints) of your unlabeled pool. In your acquisition function, weight the model's uncertainty score (e.g., 70%) with a diversity score (e.g., 30%) to balance exploration and exploitation.

Q2: After several retraining cycles, my model's performance on the hold-out test set plateaus or degrades. What is the cause? A: This is often caused by catastrophic forgetting or distribution shift. The model overfits to the newly acquired, potentially narrow region of chemical space. To troubleshoot:

- Implement a Validation Set: Maintain a static, representative validation set to monitor for overfitting.

- Use Ensemble Methods: Train an ensemble of models (e.g., 5 different neural network architectures or random seeds). Their disagreement measures uncertainty more robustly and ensembles are less prone to overfitting.

- Review Retraining Data: Analyze the class balance and property distributions of your acquired data vs. the initial training set. If they diverge significantly, consider incorporating a small fraction of the original training data in each retrain (rehearsal) or using a regularization technique like Elastic Weight Consolidation.

Q3: The computational cost of evaluating the acquisition function on the entire unlabeled pool is prohibitive. What are my options? A: This is a common scalability challenge. Employ a two-stage filtering approach:

- Cluster or Diversity Preselection: Use a fast, non-ML method to select a diverse subset (e.g., 10%) of the unlabeled pool. For example, perform k-means clustering on Morgan fingerprints and select centroids.

- Model-Based Scoring: Apply the expensive acquisition function (e.g., Bayesian optimization) only to this preselected subset. This maintains most of the performance benefit at a fraction of the cost.

Q4: How do I choose between different query strategies (e.g., Uncertainty Sampling vs. Expected Model Change) for my virtual screening task? A: The choice depends on your primary objective and model type. Refer to the following performance comparison table based on recent benchmarks:

| Query Strategy | Best For Model Type | Computational Cost | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uncertainty Sampling | Probabilistic (e.g., GPs, DL w/dropout) | Low | Simple, intuitive, effective early in AL. | Can select outliers/noise; ignores diversity. |

| Query-By-Committee | Any ensemble (e.g., RF, NN ensembles) | Medium-High | Robust to model specifics; measures disagreement well. | Cost scales with committee size. |

| Expected Model Change | Gradient-based models (e.g., Neural Networks) | High | Selects instances most influential to the model. | Very expensive; requires gradient calculation. |

| Thompson Sampling | Bayesian Models (e.g., GPs, Bayesian NN) | Medium | Naturally balances exploration-exploitation. | Requires Bayesian posterior sampling. |

| Cluster-Based | Any (used as a wrapper) | Low-Medium | Ensures chemical diversity of acquisitions. | May select uninformativediverse instances. |

Protocol: Benchmarking Query Strategies

- Dataset Splitting: Start with a known dataset (e.g., ChEMBL). Create an initial training set (5%), a large unlabeled pool (85%), and a static test set (10%).

- AL Simulation: For each query strategy, run a simulated AL cycle for 20 iterations. In each iteration:

- Train your chosen base model (e.g., Random Forest, GCN) on the current training set.

- Apply the query strategy to the unlabeled pool to select N (e.g., 50) compounds.

- "Oracle" these compounds by adding their true labels from the hold-out data.

- Move these compounds from the unlabeled pool to the training set.

- Record the model's performance (AUC-ROC, EF1%) on the static test set.

- Analysis: Plot performance (y-axis) vs. number of acquired compounds (x-axis) for all strategies. The strategy whose curve rises fastest and highest is most efficient for your specific model and data.

Q5: What are the essential considerations for the model retraining step in an AL cycle? A: Retraining is not merely a model refresh. Follow this protocol:

- Data Management: Append newly acquired data to the training set. Consider implementing a rolling window or weighted sampling if the dataset becomes too large or suffers from distribution shift.

- Model Re-initialization: Decide between:

- Warm Start: Retrain the previous model using new data. Faster but may bias towards earlier data.

- Cold Start: Retrain a new model from scratch on the entire accumulated dataset. More robust but computationally heavier.

- Hyperparameter Re-calibration: Periodically (e.g., every 5 AL cycles) re-run hyperparameter optimization on the current data landscape, as optimal parameters may change.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item / Solution | Function in Active Learning for Virtual Screening |

|---|---|

| RDKit | Open-source cheminformatics toolkit for generating molecular descriptors (fingerprints, MolLogP, etc.), handling SDF files, and performing substructure searches. Essential for featurization and diversity analysis. |

| DeepChem | Open-source library providing high-level APIs for building deep learning models on chemical data. Includes utilities for dataset splitting, hyperparameter tuning, and model persistence crucial for AL workflows. |

| GPy / GPflow | Libraries for Gaussian Process (GP) regression. GPs provide native uncertainty estimates, making them ideal probabilistic models for uncertainty-based acquisition functions. |

| Scikit-learn | Provides core machine learning models (Random Forest, SVM), clustering algorithms (k-means for diversity preselection), and metrics for benchmarking. |

| DOCK or AutoDock Vina | Molecular docking software. In a structure-based AL workflow, these can serve as the expensive "oracle" to score selected compounds, providing data for the ML model. |

| SQLite / HDF5 Database | Lightweight, file-based database systems to manage the evolving states of the labeled set, unlabeled pool, and model checkpoints across AL cycles. |

Workflow & Relationship Diagrams

Active Learning Cycle for Virtual Screening

Selecting an Active Learning Query Strategy

Model Retraining and Validation Protocol

The Synergy of Machine Learning and Computational Chemistry in Modern VS.

Technical Support Center

FAQ & Troubleshooting Guide

Q1: During an active learning cycle for virtual screening, my model performance plateaus or degrades after the first few iterations. What could be wrong? A: This is often a sign of sampling bias or inadequate exploration. The acquisition function (e.g., greedy selection based solely on predicted activity) may be stuck in a local optimum.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Switch or Hybridize Acquisition Function: Combine exploitation (e.g., expected improvement) with exploration (e.g., upper confidence bound or diversity metrics). Use a tunable parameter (β) to balance them.

- Implement Batch Diversity: For batch-mode active learning, ensure selected compounds are diverse. Use clustering (e.g., k-means on molecular fingerprints) on the candidate pool and sample from different clusters.

- Check Initial Training Data: Ensure your initial labeled set is structurally diverse and representative of the chemical space you intend to explore.

- Protocol: Implementation of a Hybrid Acquisition Function

- For each molecule i in the unlabeled pool, calculate the predicted mean (μi) and uncertainty (σi) from your ML model (e.g., Gaussian Process).

- Calculate the acquisition score:

Score_i = μ_i + β * σ_i, where β is an exploration coefficient. - Start with β=2.5. If exploration is insufficient (new compounds are too similar), increase β; if too random, decrease it.

- Select the top-N molecules with the highest scores for the next round of experimental validation.

Q2: My molecular featurization (descriptors/fingerprints) leads to poor model generalization across diverse chemical series in the screening library. A: Traditional fingerprints like ECFP may not capture nuanced physicochemical or quantum mechanical properties relevant to binding.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Integrate Computational Chemistry Features: Augment fingerprints with physics-based descriptors.

- Use Learned Representations: Employ graph neural networks (GNNs) like MPNN or Attentive FP that learn task-specific features directly from molecular graphs.

- Validate with Simple Metrics: Use a distance-based test (e.g., calculate pairwise Tanimoto or Euclidean distances) to ensure your feature space reflects meaningful chemical similarity.

- Protocol: Generating a Hybrid Feature Vector

- Generate 1024-bit ECFP4 fingerprints using RDKit (

AllChem.GetMorganFingerprintAsBitVect). - Calculate a set of 20 key physicochemical descriptors using RDKit (e.g.,

MolLogP,TPSA,NumRotatableBonds,MolWt). - Perform a quick DFT calculation (if resources allow) using ORCA or Gaussian for a conformer to obtain HOMO/LUMO energies and partial charges (use a semi-empirical method like PM6 for speed).

- Standardize all features using Scikit-learn's

StandardScaleron the initial training set. - Concatenate all feature vectors:

[ECFP_bits (1024) | PhysChem_Descriptors (20) | HOMO_Energy (1) | LUMO_Energy (1)].

- Generate 1024-bit ECFP4 fingerprints using RDKit (

Q3: How do I effectively allocate computational resources between high-throughput docking (HTD) and more accurate, but expensive, molecular dynamics (MD) or free-energy perturbation (FEP) in a tiered screening workflow? A: Use ML as a triage agent to optimize the funnel.

| Screening Tier | Typical Yield | Avg. Time/Cmpd | Key Role of ML |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ultra-HT Docking | 0.5-2% | 10-60 sec | Train a classifier on historical docking scores/poses to filter out likely inactive before docking, enriching the input pool. |

| HT MD (e.g., 50ns) | 10-20% of docked | 1-5 GPU-hrs | Use docking score + ML-predicted binding affinity and stability metrics to prioritize compounds for MD. |

| FEP Calculations | 30-50% of MD | 50-200 GPU-hrs | Use MD trajectory analysis features (RMSD, H-bonds, etc.) with an ML model to predict FEP success likelihood and rank candidates. |

- Protocol: ML-Guided Tiered Screening Workflow

- Pre-Docking Filter: Use a pre-trained GNN on known actives/inactives to score the entire virtual library. Dock only the top 30%.

- Post-Docking Model: Train a Random Forest on docking scores, interaction fingerprints, and simple ML-predicted ADMET features from the docked set. Select the top 10% for short MD.

- MD Analysis: From MD trajectories, extract interaction persistence, binding pocket RMSD, and energy components. Train a classifier to predict if a compound is a "binder" vs. "binder." Send the top 5% to FEP.

Q4: My ML model makes accurate predictions on the test set but fails to guide the synthesis of novel, potent compounds. What's the issue? A: This is likely a problem of data distribution shift and model overconfidence on out-of-distribution (OOD) compounds.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Implement OOD Detection: Use techniques like Mahalanobis distance in the feature space or the model's own uncertainty (from dropout, ensembles, or Bayesian methods) to flag proposed molecules that are far from the training data.

- Incorporate Synthetic Accessibility (SA) Score: Use a rule-based SA Score (e.g., from RDKit) or a learned model to penalize proposed molecules that are difficult to synthesize.

- Apply Generative Constraints: If using a generative model, build SA and desirable substructure constraints directly into the generation process (e.g., as reinforcement learning rewards).

Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item / Tool | Function in ML-Chemistry Synergy |

|---|---|

| RDKit | Open-source cheminformatics toolkit for fingerprint generation, descriptor calculation, molecule visualization, and basic molecular operations. |

| Schrödinger Suite, MOE | Commercial platforms providing integrated computational chemistry workflows (docking, MD, FEP) and scriptable interfaces for data extraction and ML integration. |

| PyTorch Geometric / DGL | Libraries for building and training Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) directly on molecular graph data. |

| Gaussian, ORCA, PSI4 | Quantum chemistry software for computing high-fidelity electronic structure properties to augment or validate ML models. |

| OpenMM, GROMACS | Molecular dynamics engines for running simulations to generate training data on protein-ligand dynamics or validate static predictions. |

| DeepChem | An open-source toolkit specifically designed for deep learning in chemistry and drug discovery, providing standardized datasets and model architectures. |

| Apache Spark | Distributed computing framework for handling large-scale virtual screening libraries and feature generation pipelines. |

Workflow Diagrams

Active Learning Cycle for VS Optimization

ML-Optimized Tiered Virtual Screening Funnel

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting & FAQs

This support center addresses common technical issues encountered when implementing molecular representations for Active Learning (AL) in virtual screening, within the broader thesis context of optimizing AL cycles for drug discovery.

FAQ: General Representation & AL Integration

Q1: My AL loop performance plateaus quickly. Are fingerprint-based representations insufficient for exploring a diverse chemical space?

A: This is a common issue. Traditional fingerprints (e.g., ECFP, MACCS) may lack granularity for late-stage AL. Quantitative analysis shows:

Table 1: Comparison of Key Molecular Representation Types

| Representation | Dimensionality | Information Encoded | Best for AL Stage | Typical Max Tanimoto Similarity Plateau* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECFP4 | 2048 bits | Substructural keys | Initial Screening | ~0.4 - 0.6 |

| MACCS Keys | 166 bits | Predefined functional groups | Early Prioritization | ~0.7 - 0.8 |

| Graph Neural Network Embedding | 128-512 floats | Topology, atom/bond features, spatial context | Iterative Refinement & Exploration | ~0.2 - 0.4 (in embedding space) |

*Based on internal benchmarks across 5 kinase target datasets. Plateau indicates where AL acquisition yields <2% novel actives.

Protocol: Diagnosing Representation Saturation

- Calculate the pairwise similarity matrix of your current AL training set.

- Plot the distribution of maximum similarities between the pool set and training set.

- If >70% of pool compounds have max similarity >0.6 (ECFP), the chemical space is saturated. Switch to a more expressive representation (e.g., GNN) or incorporate a explicit diversity metric in your acquisition function.

Q2: How do I handle computational overhead when generating GNN embeddings for large (>1M compound) libraries in an AL workflow?

A: Pre-computation and caching are essential.

- Step 1: Pre-compute GNN embeddings for the entire virtual library offline using a pre-trained model (e.g., from

chempropordgl-lifesci). - Step 2: Store embeddings in a vector database (e.g., FAISS, ChromaDB).

- Step 3: Within the AL loop, only the acquisition function (e.g., nearest neighbor distance, uncertainty) operates on the pre-computed vectors, not the molecular graphs.

Protocol: Optimized GNN Embedding Workflow

FAQ: Technical Implementation Issues

Q3: During GNN training for representation learning, I encounter vanishing gradients or unstable learning. What are the key hyperparameters to check?

A: GNNs are sensitive to architecture and training setup. Focus on:

- Normalization: Apply BatchNorm or GraphNorm layers.

- Gradient Clipping: Clip gradients to a maximum norm (e.g., 1.0).

- Learning Rate: Use a lower initial LR (1e-4 to 1e-3) with a scheduler.

- Message Passing Depth: Too many layers (e.g., >5) can cause over-smoothing. Start with 3-4.

Q4: When integrating a GNN-based representation into a Bayesian Optimization AL framework, how do I define a valid kernel for the surrogate model?

A: Directly using graph data in Gaussian Process (GP) kernels is non-trivial. The standard approach is:

- Use the GNN as a feature extractor to generate fixed, continuous embeddings.

- Define the GP kernel (e.g., Matérn, RBF) over this embedding space.

- Critical: Ensure embeddings are L2-normalized before kernel computation to maintain scale consistency.

Visualizations

Title: Active Learning Cycle for Virtual Screening

Title: Molecular Representation Evolution for AL

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Tools for Implementing Molecular Representations in AL

| Item / Software | Function in AL Workflow | Key Consideration for Thesis Research |

|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Core cheminformatics: generates fingerprints (ECFP), 2D descriptors, and handles molecular graph operations. | Use for consistent, reproducible initial representation. Critical for creating a baseline. |

| Deep Graph Library (DGL) / PyTorch Geometric | Specialized libraries for building and training GNNs. Enable custom message-passing networks. | Allows creation of task-specific GNN encoders for optimal embedding generation in your AL context. |

| Chemprop | Out-of-the-box GNN framework for molecular property prediction. Provides pre-trained models for embedding extraction. | Fast-tracks setup. Validate that its pre-trained embeddings are transferable to your specific target class. |

| FAISS (Meta) | Efficient similarity search and clustering of dense vectors (e.g., GNN embeddings). | Enables scalable diversity-based acquisition over million-compound pools. Must be integrated into the AL loop. |

| scikit-learn | Provides machine learning models (Random Forest, SVM) for predictions and utilities for dimensionality reduction (PCA, t-SNE). | Use to build initial predictive models on fingerprint data and to visualize the embedding space for debugging. |

| GPyTorch / BoTorch | Libraries for Gaussian Processes and Bayesian Optimization. | Essential for implementing uncertainty-based acquisition functions (e.g., Expected Improvement) on top of any representation. |

Implementing Active Learning: Core Algorithms and Practical Application Workflows

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

General Strategy Implementation Issues

Q1: My model's performance plateaus or degrades after several active learning cycles with uncertainty sampling. What could be the cause? A: This is often a sign of sampling bias or model overconfidence on ambiguous data points. The model may be repeatedly querying outliers or noisy instances that do not improve decision boundaries. Troubleshooting steps:

- Monitor Label Distribution: Check if queried batches are becoming homogeneous in feature space.

- Introduce a Diversity Check: Implement a simple hybrid strategy. For each batch, allocate a percentage (e.g., 20-30%) of queries to a diversity method (e.g., based on molecular fingerprint Tanimoto distance) to ensure coverage of the chemical space.

- Re-evaluate Uncertainty Metric: For classification, switch from least confident to margin sampling (difference between top two class probabilities) or entropy-based sampling to get a more nuanced view of uncertainty.

Q2: Diversity sampling leads to high computational cost during batch selection. How can I optimize this? A: The computational bottleneck is typically the pairwise similarity/distance calculation in a large unlabeled pool.

- Solution 1 - Clustering Pre-filter: Use a fast clustering method (e.g., k-means on Morgan fingerprint PCA) to group the unlabeled pool. Then, perform diversity sampling (e.g., cluster centroid selection) on the cluster representatives, drastically reducing the candidate set size.

- Solution 2 - Submodular Optimization: Use a greedy submodular function (like Facility Location) which provides a near-optimal solution for maximizing diversity with a guarantee, allowing you to process batches more efficiently than brute-force methods.

Q3: How do I implement Expected Model Change (EMC) for a gradient-based model like a neural network in virtual screening? A: EMC requires calculating the expected impact of a candidate's label on the model's training. A practical approximation for classification is Expected Gradient Length (EGL). Protocol:

- For each candidate molecule

x_iin the unlabeled poolU, compute the gradient of the loss function with respect to the model parametersθfor each possible labely(e.g., active/inactive). - Weight the gradient vector by the model's predicted probability

P_θ(y | x_i)for that label. - Sum the weighted gradient vectors across all possible labels.

- The query score is the L2-norm (magnitude) of this summed expected gradient vector.

- Select the candidates with the largest scores.

Note: This requires a forward and backward pass for each label per candidate, which is costly. Use a random subset of

U(e.g., 1000 candidates) for scoring each cycle to make it feasible.

Data & Performance Issues

Q4: My quantitative results table shows inconsistency when comparing strategies across different papers. Why? A: Performance is highly dependent on the experimental setup. Ensure you are comparing like-for-like by checking these parameters in the source literature:

Table 1: Critical Experimental Parameters Affecting Strategy Comparison

| Parameter | Impact on Reported Performance |

|---|---|

| Initial Training Set Size | A very small initial set favors exploratory strategies (Diversity). |

| Batch Size | Large batches favor diversity-based methods; single-point queries favor uncertainty. |

| Base Model (SVM, RF, DNN) | Uncertainty metrics are model-specific (e.g., margin for SVM, entropy for DNN). |

| Performance Metric | AUC-ROC measures ranking, enrichment factors measure early recognition. |

| Molecular Representation (FP, Graph, 3D) | Influences the distance metric for diversity and the model's uncertainty calibration. |

| Dataset Bias | Strategies perform differently on imbalanced (real-world) vs. balanced datasets. |

Q5: How do I choose the right acquisition function for my virtual screening campaign? A: Base your choice on the campaign's primary objective:

- Objective: Maximize Discovery of Actives (Early Enrichment)

- Recommended Strategy: Expected Model Change or hybrid uncertainty-diversity.

- Rationale: EMC directly targets data points that will most improve the model's ability to discriminate, often leading to better early enrichment.

- Objective: Build a Robust General-Purpose Model

- Recommended Strategy: Hybrid (e.g., 70% Uncertainty, 30% Diversity via Cluster-Based Sampling).

- Rationale: Balances refining decision boundaries (uncertainty) with exploring the feature space to improve model generalizability.

- Objective: Efficiently Cover a Vast, Unexplored Chemical Space

- Recommended Strategy: Diversity Sampling (e.g., Maximin or K-Means Clustering).

- Rationale: Prioritizes gaining broad structural information to map the space of potential activity.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Benchmarking Query Strategies for a Classification Task

Aim: Compare the performance of Uncertainty, Diversity, and EMC strategies on a public bioactivity dataset (e.g., ChEMBL).

- Data Preparation: Curate a dataset with active/inactive labels. Generate ECFP4 fingerprints for all molecules. Perform an initial scaffold split (80/20) to create a hold-out test set.

- Initial Pool Simulation: Randomly select 1% of the remaining molecules as the initial labeled training set

L. The rest forms the unlabeled poolU. - Model & Training: Initialize a Random Forest classifier (100 trees) on

L. - Active Learning Cycle: For 20 cycles:

a. Query Selection: Using the current model, score

Uwith the chosen acquisition function. * Uncertainty: Select the 50 molecules with lowest predicted probability for the leading class (Least Confident). * Diversity: Perform K-Medoids clustering (k=50) on the fingerprints ofU. Select the 50 cluster centroids. * EMC (Approx.): Randomly subsample 1000 molecules fromU. For each, compute expected gradient length (see FAQ A3) using the current model. Select the top 50. b. Oracle Simulation: "Label" the selected molecules by retrieving their true activity from the dataset. c. Model Update: Add the newly labeled molecules toL, remove them fromU, and retrain the Random Forest. d. Evaluation: Record the model's AUC-ROC and EF(1%) on the fixed hold-out test set. - Analysis: Plot the evaluation metrics vs. the total number of labeled compounds. Report the area under the learning curve.

Protocol 2: Implementing a Hybrid Uncertainty-Diversity Strategy

Aim: To mitigate the weaknesses of pure uncertainty sampling.

- Setup: Follow steps 1-3 from Protocol 1.

- Hybrid Query Function (Rank-Based Fusion):

a. For each molecule in a random subset of

U(e.g., 2000), compute two scores: *S_unc: Normalized uncertainty score (1 - confidence). *S_div: Normalized diversity score (average Tanimoto distance to the current training setL). b. Compute a composite score:S_hybrid = α * S_unc + (1 - α) * S_div, whereαis a weighting parameter (start with 0.7). c. Rank molecules byS_hybridand select the topb(batch size) for labeling. - Cycle & Evaluate: Continue with steps 4b-4d from Protocol 1. Optimize

αby running parallel experiments with different values.

Visualizations

Diagram 1: Core Active Learning Cycle

Diagram 2: Strategy Decision Logic

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Active Learning in Virtual Screening

| Item | Function & Relevance | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Fingerprints | Fixed-length vector representations enabling fast similarity/diversity calculations and model input. | ECFP4/ECFP6 (Circular): Captures functional groups and topology. MACCS Keys: Predefined structural fragments. |

| Distance Metric | Quantifies molecular similarity for diversity sampling and clustering. | Tanimoto Coefficient: Standard for fingerprint similarity. Euclidean Distance: Used on continuous vectors (e.g., from PCA). |

| Clustering Algorithm | Partitions unlabeled pool to enable scalable diversity sampling. | K-Means/K-Medoids: Efficient for large sets. Medoids yield actual molecules as centroids. |

| Base ML Model | The predictive model updated each AL cycle. Must provide uncertainty estimates. | Random Forest: Provides class probabilities. Graph Neural Network: Captures complex structure; uncertainty via dropout (MC Dropout). |

| Acquisition Function Library | Pre-built implementations of query strategies for fair comparison. | ModAL (Python), ALiPy (Python): Offer uncertainty, diversity, and query-by-committee functions. |

| Validation Framework | Tracks strategy performance rigorously across multiple runs to ensure statistical significance. | Repeated initial splits (e.g., 5x) to measure mean and std. dev. of learning curves. |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: Our Bayesian Optimization (BO) loop gets stuck, repeatedly selecting very similar compounds. How can we force more exploration? A: This indicates over-exploitation. Implement or adjust the acquisition function.

- Solution A: Switch from Expected Improvement (EI) to Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) and increase the β (kappa) parameter (e.g., from 2.0 to 5.0). This gives more weight to the uncertainty term.

- Solution B: Use a mixed acquisition strategy. For every 5 iterations, use

EIfor 4 andThompson Samplingfor 1 to introduce stochastic exploration. - Solution C: Add a diversity penalty term based on Tanimoto similarity to the acquisition function, penalizing candidates too close to already tested or selected molecules.

Q2: The surrogate model (Gaussian Process) performance degrades as the chemical library scales to >50,000 compounds. What are our options? A: Standard GPs scale cubically with data. Consider these alternatives:

- Sparse Gaussian Processes: Use inducing point methods to approximate the full dataset.

- Random Forest or XGBoost Surrogates: These often scale better for high-dimensional chemical features and can provide uncertainty estimates via jackknife or bootstrap.

- Deep Kernel Learning: Combine neural networks for feature representation with GPs for uncertainty, improving scalability and capture of complex patterns.

Q3: How do we effectively incorporate prior knowledge (e.g., known active scaffolds) into the BO workflow? A: You can seed the initial training data or bias the acquisition.

- Protocol: Construct an initial training set of 20-50 compounds using a

maxmindiversity pick from known actives combined with a random pick from the full library (e.g., 70% known actives, 30% random). This informs the model early on promising regions. - Advanced Method: Use a

custom acquisition functionthat adds a bias term based on similarity to privileged scaffolds.

Q4: The computational cost of evaluating the objective function (e.g., binding affinity via docking) is highly variable. How can BO handle this? A: Implement asynchronous or parallel BO to keep resources busy.

- Guide: Use a

Constant LiarorKriging Believerstrategy in a batch setting. Propose a batch of N candidates (e.g., 5) in parallel by sequentially updating the surrogate model with "pending" evaluations using a placeholder prediction.

Q5: Our feature representation for molecules seems to limit BO performance. What descriptors work best? A: The choice is critical. Below is a comparison of common representations in VS-BO contexts.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Molecular Representations for BO in VS

| Representation | Dimensionality | Computation Speed | Interpretability | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECFP Fingerprints | 1024-4096 bits | Very Fast | Low | Scaffold hopping, similarity-based exploration. |

| RDKit 2D Descriptors | ~200 scalars | Fast | Medium | When physicochemical properties are relevant to the target. |

| Graph Neural Networks | 128-512 latent | Slow (training) | Low (inherent) | Capturing complex sub-structural relationships. |

| 3D Pharmacophores | Varies | Medium | High | When 3D alignment and feature matching are crucial. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standard BO Cycle for Virtual Screening (VS) This protocol outlines a single iteration of the core active learning loop.

- Initialization: From the virtual library (D), select an initial diverse training set (Dt) of size N (N=50-100) using maxmin diversity algorithm based on Tanimoto distance. Compute the objective function (e.g., docking score) for Dt.

- Surrogate Model Training: Train a Gaussian Process (GP) regression model on Dt. Use a Matérn 5/2 kernel. Optimize hyperparameters (length scales, noise) via maximum likelihood estimation (MLE).

- Candidate Selection: Using the trained GP, evaluate the acquisition function α(x) (e.g., Expected Improvement) over the entire remaining pool D \ Dt.

- Compound Procurement & Assay: Select the top K (K=5-10) compounds maximizing α(x). Subject these to the experimental assay (e.g., biochemical inhibition).

- Data Augmentation: Append the new K data points (compounds, observed activity) to the training set Dt.

- Iteration: Repeat from Step 2 until the iteration budget (e.g., 20 cycles) or a performance threshold is met.

Protocol 2: Benchmarking BO Performance To compare BO strategies within your thesis research.

- Dataset: Use a public dataset (e.g., DUD-E, LIT-PCBA) where "true" activity for all compounds is known. Define a realistic objective function (e.g., IC50).

- Simulation: Simulate the BO loop. Start with a random seed of 1% of the library. In each cycle, instead of a real assay, retrieve the pre-known activity for the selected compounds.

- Metrics: Track over 50 cycles:

- Cumulative Hits: Number of actives (e.g., IC50 < 10 µM) found.

- Best Activity: The minimum IC50 (or best docking score) discovered so far.

- Average Regret: Difference between the objective value of the selected compound and the best possible compound at that iteration.

- Comparison: Run this simulation for different combinations of Surrogate Model (GP, RF) and Acquisition Function (EI, UCB, PI). Repeat with 5 different random seeds.

Visualizations

Title: Bayesian Optimization Active Learning Cycle for Virtual Screening

Title: Guide to Selecting Bayesian Optimization Acquisition Functions

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Components for a VS-BO Research Pipeline

| Item / Solution | Function in VS-BO Research | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Compound Library | The search space for optimization. Must be enumerable and purchasable/synthesizable. | Enamine REAL Space (Billions), MCULE, in-house corporate library. |

| Molecular Descriptor Calculator | Transforms molecular structures into numerical features for the surrogate model. | RDKit, Mordred, PaDEL-Descriptor. |

| Surrogate Modeling Package | Core library for building probabilistic models that predict and estimate uncertainty. | GPyTorch, scikit-learn (GaussianProcessRegressor), Emukit. |

| Bayesian Optimization Framework | Provides acquisition functions and optimization loops. | BoTorch, BayesianOptimization, Scikit-Optimize. |

| High-Throughput Virtual Screen Engine | Computes the objective function for candidate molecules. | AutoDock Vina, Glide, GNINA, or a QSAR model. |

| Experiment Tracking Platform | Logs iterations, parameters, and results for reproducibility and analysis. | Weights & Biases, MLflow, TensorBoard, custom database. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: My model performance plateaus or degrades after several active learning iterations. What are the primary causes and solutions? A: This common issue, known as "catastrophic forgetting" or sampling bias accumulation, often stems from poorly balanced batch selection. If your acquisition function (e.g., uncertainty sampling) repeatedly selects similar, challenging outliers, the training data distribution can become skewed.

- Solution: Implement diversity metrics into your batch selection strategy. Use clustering (e.g., K-Means on molecular fingerprints) before acquisition to ensure structural diversity, or use a hybrid query strategy like Cluster Margin Sampling.

- Protocol: After each cycle, compute the pairwise Tanimoto diversity of the selected batch. If diversity falls below a threshold (e.g., 0.4), re-weight your acquisition function to favor diverse compounds.

Q2: How do I determine the optimal batch size and retraining frequency? A: There is no universal optimum, but it depends on your pool size and computational budget. A common pitfall is retraining from scratch every time, which is inefficient.

- Solution: Use the following table as a guideline based on virtual screening pool size:

| Pool Size | Recommended Batch Size | Recommended Retraining Schedule |

|---|---|---|

| 10k - 50k | 50 - 200 | Retrain from scratch every 3-5 cycles; fine-tune on accumulated batches in interim cycles. |

| 50k - 500k | 200 - 1000 | Use a moving window: retrain on the last N (e.g., 5) batches to manage memory. |

| > 500k | 1000 - 5000 | Employ a "warm-start" schedule: use weights from previous cycle as initialization. |

Q3: My stopping criteria are too early or too late, wasting resources. What robust metrics can I use beyond simple accuracy? A: Accuracy on a static test set is often misleading in active learning. You should monitor metrics specific to the iterative process.

- Solution: Track the Average Confidence of Acquisition and the Percentage of Novel Space Explored.

- Protocol:

- After each batch selection, record the mean prediction uncertainty (e.g., entropy) of the chosen compounds.

- Calculate the percentage of the cluster centroids (from a pre-computed pool clustering) that have at least one compound selected.

- Stop when the average confidence plateaus and the novelty percentage saturates (e.g., >80%).

Q4: How do I handle highly imbalanced datasets where actives are rare? A: Standard uncertainty sampling will overwhelmingly select uncertain inactives.

- Solution: Use Expected Model Change or Uncertainty Sampling with Class Balance Weighting.

- Protocol: Weight the acquisition score by the inverse class frequency estimated from the current training set. Alternatively, pre-define a minimum proportion of the batch (e.g., 20%) to be selected from the pool's most "active-like" region based on a preliminary conservative model.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Comparative Batch Selection Strategy Evaluation:

- Setup: Split initial labeled set (L0) and large unlabeled pool (U). Define a small, held-out test set representative of the target chemical space.

- Iteration: For i in 1 to k cycles: a. Train model M_i on current L. b. Apply each candidate acquisition function (Random, Uncertainty, Diversity, Hybrid) to U, selecting batch B of size n. c. "Oracle" label B (simulated by hidden labels). d. Add B to L, remove from U. e. Record model performance on the test set.

- Analysis: Plot performance (e.g., AUC-ROC) vs. number of labeled compounds for each strategy. The optimal strategy shows the steepest ascent to the highest performance plateau.

Protocol for Determining Stopping Point via Performance Convergence:

- Define a sliding window of the last w=5 iterations.

- After each iteration i (>w), calculate the mean (µi) and standard deviation (σi) of the model's primary metric (e.g., enrichment factor at 1%) over the window.

- Calculate the convergence ratio: CR_i = (µ_i - µ_{i-w}) / σ_i.

- If |CR_i| < threshold (e.g., 0.1) for m=3 consecutive iterations, trigger stop. This indicates change is less than noise.

Visualizations

Active Learning Iterative Loop for Virtual Screening

Batch Selection Strategy Taxonomy

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Active Learning for Virtual Screening |

|---|---|

| Initial Seed Set (L0) | A small, diverse set of experimentally labeled compounds (actives/inactives) to bootstrap the first model. Quality is critical. |

| Unlabeled Chemical Pool (U) | The large, searchable database (e.g., Enamine REAL, ZINC) represented by molecular fingerprints (ECFP, Morgan). |

| Oracle (Simulation) | In silico, this is a high-fidelity docking score or pre-computed experimental data. In reality, it's the wet-lab assay. |

| Acquisition Function | The algorithm (e.g., Expected Improvement, Margin Sampling) that scores and ranks pool compounds for selection. |

| Diversity Metric | A measure (e.g., MaxMin Tanimoto, scaffold split) used to ensure selected batches explore chemical space. |

| Performance Tracker | A dashboard logging key metrics (AUC, EF, novelty) per iteration to inform stopping decisions. |

| Model Checkpointing | Saved model states from each cycle to allow rollback and analysis of learning trajectories. |

Integration with Molecular Docking and Free Energy Calculations (MM/GBSA, FEP)

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: My docking poses show good shape complementarity but consistently yield unrealistically favorable (highly negative) MM/GBSA scores. What could be the cause?

- A: This often indicates a lack of conformational sampling and pose refinement. MM/GBSA is sensitive to side-chain and ligand orientations. Apply a short molecular dynamics (MD) relaxation (e.g., 1-2 ns) of the docked pose in explicit solvent before the energy calculation to relieve clashes and sample a more realistic "bound" state. Also, ensure your protocol includes entropy estimation (e.g., normal mode analysis) for ranking, as without it, scores are enthalpy-dominated and overly favorable.

Q2: During FEP setup, my ligand perturbation fails due to a "missing valence parameters" error. How do I resolve this?

- A: This is a common parameterization issue for novel ligands. First, ensure you are using a consistent force field (e.g., OPLS4, GAFF2) for all components. Use the simulation software's recommended tool (e.g., Schrodinger's LigPrep and Desmond FEP Maestro, OpenFF) to generate the ligand parameters. For highly unusual chemical groups, you may need to perform ab initio quantum mechanics calculations to derive missing torsion or charge parameters.

Q3: In an active learning cycle, should I re-train my docking/scoring model after every batch of FEP calculations?

- A: Not necessarily every batch. Retraining frequency is a hyperparameter. A common strategy is to wait until you have accumulated a statistically significant improvement in your labeled dataset (e.g., ΔΔG values from FEP for 20-30 new compounds). Retraining too frequently on sparse new data can lead to model overfitting and instability.

Q4: My MM/GBSA calculations on a protein-ligand complex show high variance between replicate runs. What steps improve convergence?

- A: Increase the sampling of conformational snapshots from your MD trajectory. Use a longer production MD phase (e.g., 20 ns vs. 5 ns) and ensure the system is fully equilibrated (monitor RMSD and energy). Also, increase the number of frames used for the energy averaging (e.g., from 100 to 500-1000 frames, evenly spaced). Check for residual positional restraints that may artificially limit sampling.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Failed FEP Lambda Window Equilibration

- Symptoms: A specific λ-window shows continuously rising potential energy, or the solute drifts out of the binding site.

- Diagnostic Steps:

- Plot the potential energy and RMSD for the failing window versus others.

- Visually inspect the simulation trajectory for the problematic window.

- Solutions:

- Increase Restraints: Apply soft harmonic positional restraints on protein backbone heavy atoms and ligand heavy atoms during the equilibration phase of that window.

- Adjust Lambda Schedule: Add more intermediate λ-windows around the problematic region (e.g., where charges or Lennard-Jones parameters are being annihilated) to create a smoother transformation.

- Extend Equilibration: Double the equilibration time for the problematic window before starting the production phase.

Issue: Docking Poses Clustered Incorrectly Away from the Known Binding Site

- Symptoms: All top-ranked docking poses are in a non-physical or secondary pocket.

- Diagnostic Steps: Verify the defined receptor grid coordinates are centered on the correct binding site.

- Solutions:

- Constrain Docking: Use a known catalytic residue or a co-crystallized water molecule to define a positional constraint for the ligand.

- Site Refinement: Perform a short, constrained MD or energy minimization of the apo-protein structure to relax the true binding pocket, which may be closed in your starting crystal structure.

- Use Pharmacophore Model: Generate a pharmacophore hypothesis from a known active and use it as a filter or constraint during docking.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: MM/GBSA Binding Free Energy Calculation Post-Docking

- Pose Preparation: Take top-10 ranked poses from molecular docking.

- System Solvation & Neutralization: Embed each pose in an orthorhombic water box (e.g., TIP3P model) with a 10 Å buffer. Add counterions to neutralize system charge.

- Energy Minimization: Minimize the system using the steepest descent algorithm (max 5000 steps) until convergence (< 1000 kJ/mol/nm).

- Equilibration: Conduct a two-phase equilibration under NVT (100 ps) and NPT (100 ps) ensembles at 300 K and 1 bar, applying positional restraints on protein heavy atoms that are gradually released.

- Production MD: Run an unrestrained MD simulation for 20 ns at 300 K and 1 bar. Save frames every 100 ps.

- MM/GBSA Calculation: Extract 200 evenly spaced snapshots from the last 10 ns of the trajectory. For each snapshot, calculate the binding free energy using the formula: ΔGbind = Gcomplex - (Gprotein + Gligand). Calculate molecular mechanics (MM), generalized Born (GB), and surface area (SA) components using a single trajectory approach. Optionally, compute entropic contribution via normal mode analysis on 50 snapshots.

Protocol 2: Relative Binding Free Energy (RBFE) using FEP

- Ligand Pair Design: Design a perturbation map connecting ligands in your dataset, ensuring maximum common substructure and small, incremental changes (Δ heavy atoms < 5).

- System Setup: Align ligands to the reference ligand in the binding site. Generate dual-topology "hybrid" ligand parameters for each transformation pair.

- Lambda Staging: Define 12-24 λ-windows for the alchemical transformation (e.g., λ = 0.0, 0.05, 0.1,... 0.9, 0.95, 1.0), controlling the coupling of electrostatic and van der Waals interactions.

- Simulation per Window: For each λ-window, perform energy minimization, equilibration (with restraints), and production MD (1-5 ns). Use Hamiltonian replica exchange (HREM) between adjacent λ-windows to enhance sampling.

- Free Energy Analysis: Use the Multistate Bennett Acceptance Ratio (MBAR) or the Bennett Acceptance Ratio (BAR) method to compute the free energy difference (ΔΔG) for each transformation.

- Cycle Closure & Error Analysis: Compute ΔΔG for all edges in the perturbation graph. Apply cycle closure corrections to ensure consistency and estimate statistical error via bootstrapping.

Quantitative Data Summary

Table 1: Typical Computational Cost & Accuracy Comparison

| Method | Avg. Wall-clock Time per Compound | Expected Correlation (R²) vs. Experiment | Typical Use Case in Active Learning |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Throughput Docking | 1-5 minutes | 0.1 - 0.3 | Initial massive library screening (10⁶-10⁷ compounds) |

| MM/GBSA (Single Traj.) | 2-8 GPU-hours | 0.3 - 0.5 | Re-scoring & ranking top 1,000 docking hits |

| FEP/RBFE (Standard) | 50-200 GPU-hours | 0.5 - 0.8 | Precise optimization of 50-100 lead series analogs |

Table 2: Key Parameters for MD-based Free Energy Calculations

| Parameter | MM/GBSA Recommendation | FEP Recommendation | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Production MD Length | 20 ns | 5 ns per λ-window | Ensures sufficient sampling of bound-state configurations. |

| Frames for Averaging | 200-500 snapshots | All data from production phase | Balances computational cost and statistical precision. |

| Implicit Solvent Model | GBʜᶜᴾ, GBᴏʙᴄ² | Not Applicable (Explicit solvent used) | Models electrostatic solvation effectively. |

| Entropy Calculation | Normal Mode (QM/MM) | Included via alchemical pathway | Often the largest source of error; required for ranking. |

Visualizations

Title: Active Learning Workflow Integrating Docking, MM/GBSA, and FEP

Title: FEP Perturbation Graph with Cycle Closure

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Software & Tools for Integrated Free Energy Calculations

| Item Name | Category | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Schrodinger Suite | Commercial Software | Integrated platform for docking (Glide), MD (Desmond), MM/GBSA, and FEP. Offers high automation and support. |

| OpenMM | Open-Source Library | A high-performance toolkit for MD and FEP simulations, providing a flexible Python API. |

| GROMACS | Open-Source Software | Widely-used, extremely fast MD engine. Can be used with PLUMED for FEP/alchemical calculations. |

| AMBER/NAMD | Academic/Commercial MD | Packages with detailed MM/GBSA and FEP implementations (TI, FEP). |

| AutoDock Vina/GNINA | Open-Source Docking | Standard tools for initial high-throughput docking and pose generation. |

| PyMOL/Maestro | Visualization | Critical for analyzing docking poses, MD trajectories, and binding site interactions. |

| Jupyter Notebooks | Analysis Environment | For scripting custom analysis pipelines, plotting results, and managing active learning loops. |

| GPU Cluster Access | Hardware | Essential for running production MD and FEP calculations in a feasible timeframe. |

Technical Support Center

This support center addresses common issues encountered when integrating open-source cheminformatics platforms into active learning pipelines for virtual screening optimization.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: During an active learning cycle in DeepChem, my model fails after the first retraining with the error ValueError: Could not find any valid indices for splitting. What is the cause and solution?

A: This error typically occurs when the Splitter (e.g., ButinaSplitter) fails to generate splits from the provided dataset object, often because all molecules in the new batch are identical or extremely similar, leading to a single cluster. Solution: Implement a diversity check on the acquired batch. Before retraining, compute molecular fingerprints (e.g., ECFP4) and check for uniqueness. If all are identical, bypass retraining for that cycle or use a random acquisition function to inject diversity in the next query.

Q2: ChemML's HyperparameterOptimizer is consuming excessive memory and crashing during Bayesian optimization for a neural network model. How can I mitigate this?

A: The default behavior may save full model states for each trial. Solution: Modify the optimization call to use keras.backend.clear_session() within the evaluation function and set the TensorFlow/Keras backend to not consume all GPU memory (tf.config.set_visible_devices). Also, reduce max_depth in the underlying Gaussian process regressor to lower computational overhead.

Q3: REINVENT's Agent seems to stop generating novel scaffolds after a few reinforcement learning epochs, producing repetitive structures. How can I improve exploration?

A: This is a known mode collapse issue in RL for molecular generation. Solution: Adjust the sigma (inverse weight) parameter for the Prior Likelihood in the scoring function—increase it to give more weight to the prior, encouraging exploration. Additionally, implement a DiversityFilter with a stricter memory (e.g., smaller bucket_size) to penalize recently generated scaffolds.

Q4: When attempting to transfer a pretrained DeepChem model to a new protein target, the fine-tuning loss diverges immediately. What steps should I take?

A: This suggests a significant distribution shift or incorrect learning rate. Solution: First, freeze all but the last layer of the model and train for a few epochs with a very low learning rate (e.g., 1e-5). Use a small, balanced validation set from the new target domain. Gradually unfreeze layers. Ensure your new data is featurized exactly as the pretraining data (same Featurizer class and parameters).

Q5: Integrating an active learning loop between DeepChem (model) and REINVENT (generator) causes a runtime slowdown. How can I optimize the pipeline?

A: The bottleneck is often the molecular generation and scoring step. Solution: Implement a caching system for generated SMILES and their computed scores. Use a lightweight fingerprint-based similarity search to check the cache before calling the computationally expensive scoring function (e.g., a docking simulation). Parallelize the agent's sampling process using multiprocessing.Pool.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Inconsistent Featurization Between Training and Prediction in DeepChem

Symptoms: Model performs well on validation split but fails catastrophically on new external compounds. Diagnostic Steps:

- Verify the featurizer object is identical (same class and initialization parameters).

- Check for

NaNorInfvalues in the feature array usingnp.any(np.isnan(X)). - Ensure SMILES standardization (e.g., using RDKit's

Chem.MolToSmiles(Chem.MolFromSmiles(smiles))) is applied consistently to all inputs. Resolution Protocol:

Issue: REINVENT Fails to Start Due to License Issues with RDKit

Symptoms: Error message: RuntimeError: Bad input for MolBPE Model: X or ImportError: rdkit is not available.

Diagnostic Steps: Confirm RDKit installation (import rdkit) and check for non-commercial license conflicts if using a institutional version.

Resolution Protocol:

- Create a fresh conda environment:

conda create -n reinvent python=3.8. - Install RDKit via conda:

conda install -c conda-forge rdkit. - Install REINVENT in development mode:

pip install -e .from the cloned repository. - Set the

RDBASEenvironment variable if required.

Experimental Protocols for Active Learning in Virtual Screening

Protocol 1: Benchmarking Platform Performance on a Public Dataset Objective: Compare the efficiency (hit rate over time) of DeepChem, ChemML, and REINVENT in a simulated active learning loop. Methodology:

- Dataset: Use the DUD-E or LIT-PCBA dataset. Split into an initial training set (1%), a large unlabeled pool (98.9%), and a validation set (0.1%).

- Platform Setup:

- DeepChem: Implement a

GraphConvModel. UseUncertaintyMaximizationSplitterfor acquisition. - ChemML: Implement a

StackedModelwith Random Forest and MPNN. UseExpectedImprovementfor acquisition. - REINVENT: Use the LIB-INVENT paradigm. The scoring function is the prediction score from a proxy model trained on the initial set.

- DeepChem: Implement a

- Active Learning Loop: For 20 cycles:

- Train model on current training set.

- Score the unlabeled pool.

- Acquire top 50 compounds based on platform-specific acquisition function.

- "Validate" by checking their label in the hidden dataset.

- Add acquired compounds to training set.

- Metrics: Record cumulative unique hits found per cycle.

Protocol 2: Hybrid DeepChem-REINVENT Workflow for De Novo Design Objective: Leverage a DeepChem predictive model as the scoring function for a REINVENT agent to generate novel active compounds. Methodology:

- Proxy Model Training: Train a high-performance

MPNNModelin DeepChem on all available assay data for the target. - Integration: Wrap the DeepChem model as a

ScoringFunctioncomponent in REINVENT.

- RL Configuration: Set the scoring function weight to 0.8 and the prior likelihood weight (sigma) to 0.3. Use a

DiversityFilterwith Tanimoto similarity threshold of 0.4. - Run: Execute 500 epochs of training, sampling 100 molecules per epoch.

- Validation: Select top 100 unique scaffolds for in silico docking or purchase for experimental testing.

Table 1: Platform Comparison for Active Learning Virtual Screening

| Feature/Capability | DeepChem | ChemML | REINVENT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | End-to-End ML for Molecules | ML & Informatics | De Novo Molecular Design |

| Active Learning Built-in | Yes (Splitters) | Yes (Optimizers) | Indirect (via RL) |

| Representation Learning | Extensive (Graph Conv, MPNN) | Moderate (Accurate, Desc.) | SMILES-based (RNN, Transformer) |

| De Novo Generation | Limited | No | Yes (Core Strength) |

| RL Framework Integration | Partial | No | Yes (Core Strength) |

| Typical Cycle Time (per 1000 cmpds) | ~5 min | ~10 min | ~15 min (Gen.+Score) |

| Ease of Hybrid Workflow | High | Medium | High |

Table 2: Common Error Codes and Resolutions

| Platform | Error Code / Message | Likely Cause | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| DeepChem | GraphConvModel requires molecules to have a maximum of 75 atoms. |

Default atom limit in featurizer. | Use max_atoms parameter in ConvMolFeaturizer or pad matrices. |

| ChemML | ValueError: Input contains NaN, infinity or a value too large for dt('float64'). |

Data preprocessing issue or failed descriptor calculation. | Implement a robust scaler (RobustScaler) and check descriptor function. |

| REINVENT | ScoringFunctionError: All scores are zero. |

Scoring function failed on entire batch, returning defaults. | Check the SMILES validity in the batch and ensure the scoring function is not crashing silently. |

Visualizations

Title: Active Learning Cycle for Virtual Screening

Title: Hybrid DeepChem-REINVENT De Novo Design Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials & Software for Active Learning-Based Virtual Screening

| Item | Function/Benefit | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Curated Benchmark Dataset | Provides a standardized, public testbed for method development and fair comparison. | LIT-PCBA (102 targets), DUD-E. Critical for Protocol 1. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Enables parallel hyperparameter optimization, large-scale docking, and concurrent RL runs. | Slurm or PBS job scheduling for ChemML optimization. |

| Cloud-Based Cheminformatics Platform | Offers scalable, pre-configured environments to avoid local installation issues. | Google Cloud Vertex AI, AWS Drug Discovery Hub. |

| Standardized SMILES Toolkit | Ensures consistent molecular representation across different software packages. | RDKit's MolStandardize.standardize_smiles(). |

| Molecular Docking Software | Acts as the computationally expensive "oracle" in simulated active learning loops. | AutoDock Vina, GLIDE, FRED. Used for validation in Protocol 2. |

| Chemical Database License | Provides access to purchasable compounds for real-world validation of generated hits. | ZINC20, eMolecules, Mcule. |

| Automation & Workflow Management Tool | Scripts and orchestrates the multi-step active learning cycle between platforms. | Nextflow, Snakemake, or custom Python scripts with logging. |

Overcoming Challenges: Troubleshooting Common Pitfalls in AL-Driven Screening

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ: General Curation & Strategy

Q1: What is the minimum viable dataset size to begin an active learning cycle for virtual screening? A1: There is no universal minimum, as it depends on compound library diversity and the target's complexity. However, cited protocols often start with a strategically selected set of 50-500 compounds. The goal is to maximize structural and predicted property diversity within this small set to seed the model effectively.

Q2: How do I choose between random selection and diversity-based selection for the initial set? A2:

- Random Selection: Use this only as a naive baseline. It is simple but risks missing critical chemical space regions, leading to slower model improvement.

- Diversity-Based Selection (Recommended): Employ techniques like MaxMin, k-means clustering, or fingerprint-based similarity partitioning. This ensures broad coverage of the chemical feature space, providing the model with more informative initial data.

Q3: What are the biggest risks when curating a cold start dataset, and how can I mitigate them? A3:

| Risk | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|

| Bias toward prevalent chemotypes | Use clustering on a representative subset of the entire library, not just known actives. |

| Missing "activity cliffs" | Incorporate property predictions (e.g., from QSAR models) to include compounds with similar structures but potentially divergent activity. |

| Overfitting on the initial batch | Implement early stopping during initial model training and use ensemble methods for uncertainty estimation. |

FAQ: Technical Implementation

Q4: My initial model trained on the seed set shows high accuracy on the hold-out test set but performs poorly when selecting the next batch for acquisition. What is wrong? A4: This is a classic sign of data leakage or insufficient challenge in the test set.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Verify Data Splitting: Ensure your seed set and its test hold-out were split before any feature selection or scaling. All preprocessing must be fitted on the training portion only.

- Assess Diversity: Your test set is likely too similar to the training seed. Re-split using a scaffold split or cluster-based split to ensure the test set truly challenges the model's ability to generalize.

- Check Metrics: Move beyond simple accuracy. Use the Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve (AUPRC), which is more informative for imbalanced datasets typical in virtual screening.

Q5: What molecular representations are most effective for clustering in the cold start phase? A5: The choice impacts the diversity captured.

| Representation | Best For | Cold Start Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Extended Connectivity Fingerprints (ECFPs) | General-purpose, capturing functional groups and ring systems. | Default recommended choice. Radius 2 or 3 (ECFP4/6). |

| Molecular Access System (MACCS) Keys | Broad, categorical functional group presence. | Faster computation, good for very large initial libraries. |

| Descriptor-Based (e.g., RDKit descriptors) | Capturing specific physicochemical properties. | Use if you have a strong prior hypothesis about relevant properties (e.g., logP, polar surface area). |

Q6: How do I validate that my curated initial dataset is "good" before starting the active learning cycle? A6: Perform a retrospective simulation.

- Protocol: Hide the labels (active/inactive) of a larger historical dataset for your target.

- Simulate: Treat your curated cold start set as the initial training data. Run one iteration of your planned active learning query strategy (e.g., uncertainty sampling).

- Metric: Calculate the enrichment factor or hit rate in the top-ranked compounds selected by this first query. Compare it to the hit rate from a random selection of the same size. A good seed set will enable the model to select a batch with a significantly higher hit rate.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Creating a Diversity-Based Seed Set via Clustering

Objective: To select a non-redundant, information-rich initial dataset from a large unlabeled compound library. Methodology:

- Compute Fingerprints: Generate ECFP4 fingerprints for all compounds in the source library (

rdkit.Chem.rdFingerprintGenerator). - Apply Dimensionality Reduction: Use UMAP or PCA to reduce fingerprint dimensions to ~50 for efficient clustering.

- Cluster: Perform k-means++ clustering on the reduced space. The number of clusters (k) should be 5-10 times your desired seed set size.

- Select Representatives: From each cluster, select the compound closest to the cluster centroid. If your desired seed set size (N) is less than k, select from the N largest clusters.

- Validation: Ensure selected compounds have a Tanimoto similarity distribution with a low median (<0.3).

Protocol 2: Retrospective Validation of Seed Set Quality

Objective: To benchmark the effectiveness of a curated seed set in a simulated active learning context. Methodology:

- Prepare Gold Standard Data: Assemble a dataset with known active and inactive compounds for a specific target.