A Systematic Review of Machine Learning in Cancer Research: From Diagnostics to Precision Therapeutics

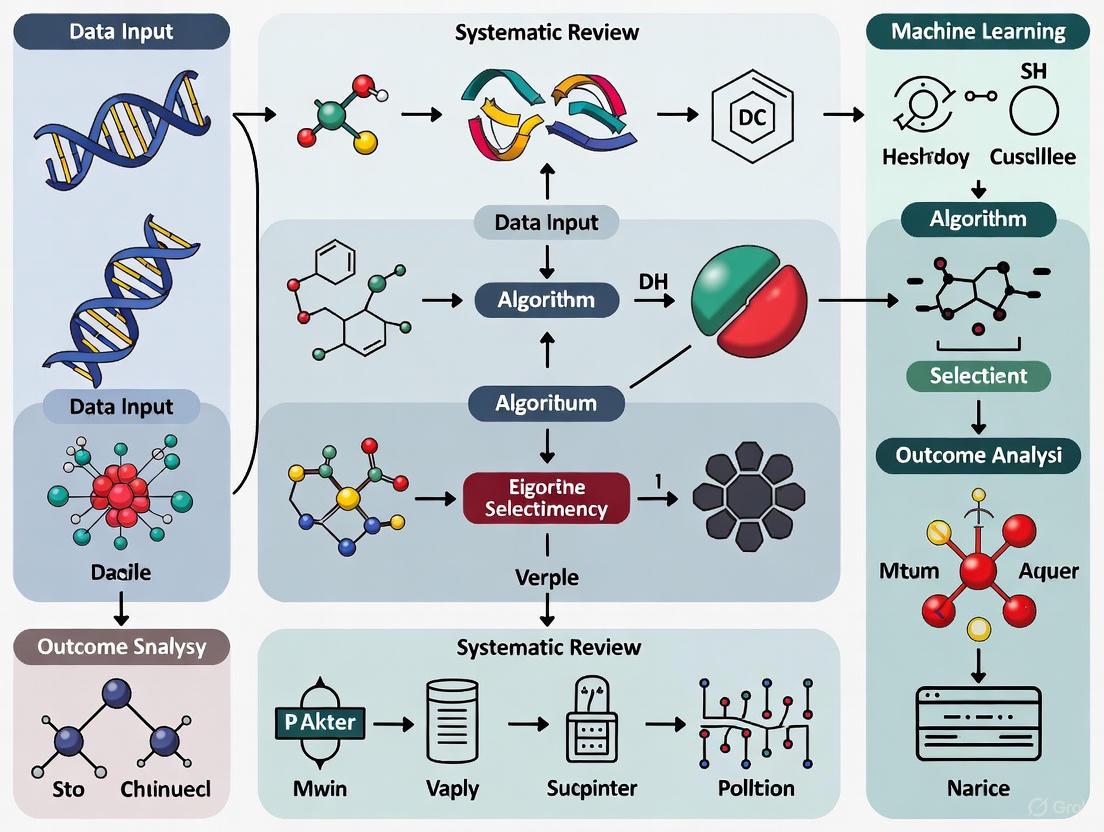

This systematic review synthesizes the current landscape of machine learning (ML) applications in oncology, addressing its transformative potential across the cancer care continuum.

A Systematic Review of Machine Learning in Cancer Research: From Diagnostics to Precision Therapeutics

Abstract

This systematic review synthesizes the current landscape of machine learning (ML) applications in oncology, addressing its transformative potential across the cancer care continuum. It explores the foundational principles of ML and the diverse data modalities, such as medical imaging, genomics, and clinical records, that fuel these applications. The review methodically catalogs ML's role in enhancing cancer screening, diagnosis, prognostic prediction, and the development of personalized treatment strategies, including drug discovery and therapy optimization. It critically examines the methodological challenges, including data heterogeneity, model interpretability, and computational demands, while providing insights into optimization techniques. Furthermore, a comparative analysis validates the performance of various ML algorithms against traditional statistical methods, highlighting contexts where ML offers superior predictive accuracy. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this article serves as a comprehensive resource on the integration of artificial intelligence to advance precision oncology and improve patient outcomes.

The AI Revolution in Oncology: Core Concepts and Data Landscapes

Artificial intelligence (AI) is rapidly revolutionizing the landscape of oncological research and the advancement of personalized clinical interventions [1]. Progress in three interconnected areas—the development of sophisticated methods and algorithms for training AI models, the evolution of specialized computing hardware, and increased access to large volumes of multimodal cancer data—has converged to create promising new applications across the cancer research spectrum [1]. This technical guide provides a systematic overview of the core components of the AI toolbox, focusing on machine learning (ML), deep learning (DL), and neural networks within the context of cancer research. We examine their fundamental principles, illustrate their applications with quantitative performance data, detail experimental methodologies, and visualize key workflows to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Core AI Concepts and Terminology

Defining the AI Landscape

In oncology, AI systems leverage diverse data modalities, including medical imaging, genomics, and clinical records, to address complex challenges from early detection to treatment optimization [1]. The selection of appropriate AI models depends fundamentally on the data type and specific clinical objective [1]. The field encompasses several interconnected disciplines:

Artificial Intelligence (AI): The broadest term, referring to machines designed to mimic cognitive functions such as learning and problem-solving. In clinical research, AI describes "intelligent agents" capable of perceiving their environment and making decisions to optimize objective achievement [2].

Machine Learning (ML): A subset of AI that enables systems to learn from data, recognize patterns, and make decisions with minimal human intervention [1]. ML algorithms often analyze structured data such as genomic biomarkers and laboratory values using classical models including logistic regression and ensemble methods for tasks like survival prediction or therapy response assessment [1].

Deep Learning (DL): A specialized subset of ML utilizing multi-layered neural networks [3]. DL has demonstrated transformative potential across diverse applications, including imaging-based diagnostics and genomic analysis, ultimately leading to improved detection and personalized cancer treatment [4]. DL architectures are particularly valuable for processing unstructured or complex data types including medical images and genomic sequences.

Neural Network Architectures in Oncology

Table 1: Key Neural Network Architectures in Cancer Research

| Architecture | Primary Data Types | Common Oncology Applications | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) [1] | Imaging data (histopathology, radiology) [1] | Tumor detection, segmentation, and grading [1] | Spatial feature extraction using convolutional layers [5] |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) [5] | Non-Euclidean data, graph structures [5] | Brain tumor classification [5] | Models relationships and dependencies between nodes [5] |

| Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) [1] | Sequential data (genomic sequences, clinical notes) [1] | Biomarker discovery, EHR mining [1] | Handles sequential dependencies through memory cells |

| Transformers & Large Language Models (LLMs) [1] | Text data, scientific literature [1] | Knowledge extraction from clinical notes, hypothesis generation [1] | Captures long-range dependencies in textual data |

| Hybrid Architectures (CNN-GNN) [5] | Imaging data represented as graphs [5] | Enhanced brain tumor classification [5] | Combines spatial feature learning with relational reasoning |

Quantitative Performance Benchmarks

The implementation of AI tools across various cancer domains has yielded substantial performance improvements in detection, classification, and prognostic tasks. The tables below summarize key quantitative benchmarks from recent studies.

Table 2: AI Performance in Cancer Detection and Diagnosis

| Cancer Type | Modality | Task | AI System | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | AUC | Accuracy (%) | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colorectal Cancer | Colonoscopy | Malignancy detection | CRCNet | 91.3 vs. 83.8 (human) | 85.3 (AI) | 0.882 | - | [1] |

| Breast Cancer | 2D Mammography | Screening detection | Ensemble DL model | +9.4% (US vs. radiologists) | +5.7% (US vs. radiologists) | 0.810 (US) | - | [1] |

| Brain Tumor | MRI | Binary classification | BCM-CNN | - | - | - | 99.98 | [3] |

| Brain Tumor | MRI | Multi-class classification | CNN-GNN | - | - | - | 95.01 | [5] |

| Multiple Cancers | Histopathology | Subtype classification | AEON + OncoTree | - | - | - | 78.0 | [6] |

Table 3: AI Performance in Liquid Biopsy and Prognostic Tasks

| Application | Method | Task | Key Performance Metrics | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liquid Biopsy | RED Algorithm | Rare cancer cell detection | Found 99% of added epithelial cancer cells; Reduced data review by 1000x | [7] |

| Tumor-Stroma Ratio Estimation | Attention U-Net | Prognostic biomarker assessment | ICC: 0.69; More consistent than human experts (DR: 0.86) | [8] |

| Immunotherapy Response Prediction | Synthetic Patient Data | Treatment response prediction | 68.3% accuracy with synthetic data vs. 67.9% with real patient data | [6] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Brain Tumor Classification Using CNN-GNN Architecture

Objective: To classify brain tumors into meningioma, pituitary, or glioma types using a hybrid Graph Convolutional Neural Network (GCNN) model that addresses non-Euclidean distances in image data [5].

Materials:

- Dataset: Publicly available Brain Tumor dataset from Kaggle containing MRI images [5].

- Computational Framework: Python with deep learning libraries (e.g., PyTorch, TensorFlow).

- Hardware: GPU-accelerated computing system.

Methodology:

- Data Preprocessing:

- Convert MRI images to graph structures where pixels represent nodes and edges represent relationships.

- Generate a standard pre-computed adjacency matrix to define node connections [5].

- Normalize pixel intensities across the dataset.

Graph Convolution Operation:

- Modify node features by combining information from nearby nodes using the adjacency matrix.

- Update input graphs as the averaged sum of local neighbor nodes to capture regional tumor information [5].

- These modified graphs serve as input matrices for the subsequent CNN.

CNN Architecture:

Training Protocol:

- Utilize appropriate loss functions (e.g., cross-entropy) for multi-class classification.

- Implement backpropagation for weight optimization.

- Employ validation sets for hyperparameter tuning.

Validation:

- Perform k-fold cross-validation to ensure robustness.

- Compare performance against human radiologists and other ML benchmarks.

Brain Tumor Classification Workflow Using Hybrid CNN-GNN Architecture

Protocol: Rare Cancer Cell Detection in Liquid Biopsies

Objective: To automate detection of rare cancer cells in blood samples using the RED (Rare Event Detection) algorithm without requiring prior knowledge of cancer cell features [7].

Materials:

- Blood Samples: From patients with advanced cancer or normal blood samples spiked with cancer cells.

- Platform: Liquid biopsy workflow for cell capture and imaging.

- Algorithm: RED deep learning algorithm based on rarity ranking rather than feature identification [7].

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation:

- Collect blood samples from patients with known advanced cancer.

- Alternatively, spike normal blood samples with known quantities of epithelial and endothelial cancer cells for validation [7].

Image Acquisition:

- Process blood samples through liquid biopsy platform.

- Generate high-resolution images of cells captured from blood.

AI Analysis with RED Algorithm:

- Implement RED algorithm to identify unusual patterns among millions of normal blood cells.

- The algorithm ranks cells by rarity, causing the most unusual findings (potential cancer cells) to rise to the top [7].

- Unlike traditional approaches, RED does not require specific known features of cancer cells, instead functioning like a "one of these things is not like the others" detection system [7].

Validation:

- Compare RED performance against human expert review.

- Quantify detection rates for spiked cancer cells (epithelial and endothelial).

- Measure reduction in data requiring human review.

Application:

- Deploy validated algorithm to answer critical clinical questions: "Do I have cancer?", "Is my cancer gone or coming back?", and "What is the best next treatment for my cancer?" [7].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Materials for AI-Cancer Research

| Reagent/Material | Function in AI-Cancer Research | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Histo-AI Dataset [8] | Provides annotated whole slide images for training and validation | Tumor-Stroma Ratio estimation models |

| TCGA-BRCA Dataset [8] | Offers multi-institutional histopathology data with clinical correlates | Development of prognostic AI biomarkers |

| BRaTS 2021 Task 1 Dataset [3] | Curated brain MRI images with tumor annotations | Brain tumor segmentation and classification models |

| Figshare Brain Tumor Dataset [5] | MRI image collection for multi-class tumor classification | Benchmarking brain tumor classification algorithms |

| OncoTree Classification System [6] | Open-source cancer type classification system | Histologic subtype classification from H&E images |

| Synthetic Patient Data [6] | AI-generated clinical and pathology data | Augmenting training datasets and imputing missing data |

AI in Clinical Trials and Drug Development

AI is transforming clinical trials by dramatically reducing timelines and costs, accelerating patient-centered drug development, and creating more efficient trials [9]. Specific applications include:

Patient Recruitment: AI-powered natural language processing analyzes structured and unstructured electronic health record data to identify protocol-eligible patients three times faster with 93% accuracy [9]. Platforms like Dyania Health demonstrate 170x speed improvement in patient identification compared to manual review [9].

Protocol Optimization: More than half of AI startups in clinical development focus on patient recruitment and protocol optimization, enabling real-time intervention and continuous protocol refinement [9].

Drug Discovery: AI supports target identification, biomarker discovery, and validation of drug candidates through structure-based virtual screening (SBVS) and ligand-based virtual screening (LBVS), speeding up the identification of potential drug candidates [2].

AI Applications in Clinical Trial Workflow

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite the promising applications, integrating DL into clinical practice presents substantial challenges including limitations in data quality and standardization, ethical and regulatory concerns, and the need for model interpretability and transparency [4]. Emerging solutions include federated learning to address data privacy concerns, explainable AI (XAI) to enhance model interpretability, and synthetic data generation to augment limited datasets [4]. The future of AI in cancer research will likely involve increased interdisciplinary collaboration, integration of next-generation AI techniques, and adoption of multimodal data approaches to improve diagnostic precision and support personalized cancer treatment [4]. Establishing industry-wide ethical standards and robust safeguards is essential for the protection of human dignity, privacy, and rights as these technologies continue to evolve [2].

Cancer manifests across multiple biological scales, from molecular alterations and cellular morphology to tissue organization and clinical phenotype [10]. Predictive models relying on a single data modality fail to capture this multiscale heterogeneity, fundamentally limiting their ability to generalize across patient populations and clinical settings [11]. Multimodal data integration has emerged as a transformative approach in oncology, systematically combining complementary biological and clinical data sources to provide a multidimensional perspective of patient health [12]. The integration of diverse data streams—including genomics, medical imaging, electronic health records (EHRs), and wearable device outputs—enables a more comprehensive understanding of cancer biology, leading to more accurate diagnoses, personalized treatment plans, and improved patient outcomes [12] [10].

The rise of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) has been instrumental in advancing multimodal integration, providing sophisticated methodologies capable of handling large, complex datasets [12] [13]. Through AI-driven integration of multimodal data, health care providers can achieve a more holistic view of cancer pathology, capturing the intricate interplay between genetic predisposition, tumor microenvironment, and clinical manifestations [14] [11]. This technical guide examines the current state of multimodal data integration in cancer research, focusing on methodological frameworks, clinical applications, and implementation protocols within the broader context of a systematic review of machine learning in oncology.

Foundations of Multimodal Integration

Data Modalities in Oncology

Multimodal integration in cancer research leverages several core data types, each providing unique insights into disease mechanisms and progression:

Genomics and Multi-omics Data: This category encompasses DNA sequencing data, gene expression profiles, epigenetic markers, and proteomic data. These modalities help identify genetic mutations, molecular subtypes, and potential biomarkers for cancer diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment selection [15] [11]. Integrated genomic analysis methods can reveal dysregulation in biological functions and molecular pathways, offering new opportunities for personalized treatment and monitoring [12].

Medical Imaging: Includes data from magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT) scans, positron emission tomography (PET), and digital histopathology [12] [16]. These modalities provide detailed anatomical and functional views of the body, offering information about tumor location, size, shape, and characteristics that aid in cancer diagnosis, staging, and treatment planning [15]. Quantitative multimodal imaging technologies combine multiple functional measurements, providing comprehensive characterization of tumor phenotypes [12].

Clinical Records and EHRs: Contain a wealth of clinical information, including patient history, diagnoses, treatments, outcomes, laboratory results, and medication records, which are essential for longitudinal health monitoring [12] [17]. These data sources provide context for molecular and imaging findings and help establish clinical correlations.

Emerging Data Sources: Include wearable device outputs that continuously monitor physiological parameters, providing real-time data on a patient's health status [12], as well as spatial transcriptomics and immunological profiles that capture tumor microenvironment dynamics [11].

The Integration Imperative

Each data modality provides valuable but incomplete insights into patient health when considered in isolation [12]. For example, genomic data may reveal targetable mutations but lack spatial context, while imaging provides structural information but limited molecular characterization. Multimodal integration addresses these limitations by fusing complementary sources for a holistic view of cancer, selectively prioritizing disease-relevant modalities to minimize noise and capture cross-scale dependencies [11].

Evidence indicates that selective integration—limiting analysis to 3–5 core modalities—often yields better predictive performance, with AUC improvements of 10–15% over unimodal baselines in oncology applications [11]. The integration of these diverse data sources enables more nuanced tumor characterization, enhanced prognostic accuracy, and personalized treatment strategies that account for the complex, multifactorial nature of cancer biology [12] [14].

Methodological Frameworks and Techniques

Machine Learning Approaches

Multimodal data integration employs diverse machine learning strategies, each with distinct advantages for handling heterogeneous oncology data:

Table 1: Machine Learning Approaches for Multimodal Data Integration in Cancer Research

| Method Category | Key Techniques | Applications in Oncology | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional ML | Random Forests, Gradient Boosting, Support Vector Machines | Cancer subtype classification, risk stratification | Handles structured data well; interpretable results |

| Deep Learning | Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), Transformers | Histopathology image analysis, genomic sequence prediction, temporal data modeling | Automatically learns relevant features from complex data; handles unstructured data |

| Multimodal Fusion | Early fusion, late fusion, hybrid approaches, attention mechanisms | Integrative prognosis, treatment response prediction | Captures cross-modal interactions; flexible architecture |

| Emerging Architectures | Graph Neural Networks, Deep Latent Variable Models, Foundation Models | Pan-cancer analysis, biomarker discovery, drug response prediction | Models complex relationships; transfers knowledge across domains |

Fusion Strategies

The integration of multimodal data can be implemented through several technical approaches:

Early Fusion: Combines raw data from multiple modalities at the input level before feature extraction. This approach can capture fine-grained interactions but requires careful data alignment and may amplify noise or dimensionality issues [11].

Late Fusion: Processes each modality independently through separate models and combines the outputs at the decision level. This strategy offers robustness against missing data and modality-specific processing but may overlook important cross-modal interactions [11].

Intermediate/Hybrid Fusion: Incorporates cross-modal interactions at intermediate processing stages using attention mechanisms, tensor fusion, or other joint representation learning techniques. Approaches like Deep Latent Variable Path Modelling (DLVPM) combine the representational power of deep learning with the capacity of path modelling to identify relationships between interacting elements in a complex system [14].

Cross-Modal Learning: Leverages information from one modality to enhance learning in another, such as predicting genetic alterations from histology images or generating synthetic medical images from clinical data [14] [10].

Advanced Integration Framework: Deep Latent Variable Path Modelling

Deep Latent Variable Path Modelling (DLVPM) represents a cutting-edge approach that combines the flexibility of deep neural networks with the interpretability and structure of path modelling [14]. This framework enables researchers to map complex dependencies between different data types relevant to cancer biology.

In DLVPM, a collection of submodels (measurement models) is defined for each data type:

Where Ȳ_i is the network output (a set of deep latent variables or DLVs), X_i is the data input, U_i is the set of parameters up to the penultimate network layer, and W_i corresponds to the network weights on the final layer [14].

The DLVPM algorithm is trained to construct DLVs from each measurement model that are optimized to be maximally associated with DLVs from other measurement models connected by the path model, with the optimization criteria:

Where c_ij represents the association matrix input from data type i to data type j, and tr denotes the matrix trace [14]. This approach has demonstrated superior performance in mapping associations between data types compared with classical path modelling, particularly in identifying histologic-transcriptional associations using spatial transcriptomic data [14].

Diagram: DLVPM Framework for Multimodal Data Integration. This architecture shows how DLVPM creates a joint embedding space from diverse data modalities using measurement models and path modelling.

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Standardized Workflow for Multimodal Integration

Implementing a robust multimodal integration system requires a systematic approach to data processing, model development, and validation:

Diagram: Multimodal Integration Workflow. This flowchart outlines the key stages in developing and deploying multimodal AI systems in oncology.

Protocol 1: Data Preprocessing and Harmonization

Objective: Standardize heterogeneous data sources to enable meaningful integration.

Materials and Methods:

- Data Collection: Acquire multi-omics data (genomics, transcriptomics, epigenetics), medical images (histopathology, radiology), and clinical records from sources such as The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) or institutional databases [14] [15].

- Quality Control: Implement modality-specific quality metrics. For genomic data: sequence quality scores, mapping rates. For imaging: signal-to-noise ratios, contrast measurements. For clinical data: completeness, consistency checks [16] [17].

- Normalization: Apply batch effect correction methods like ComBat or cross-modal harmonization techniques to account for technical variability across datasets [11].

- Feature Extraction: Utilize automated feature extraction for images (CNNs), sequence embedding for genomic data, and structured feature engineering for clinical variables [16] [15].

Validation: Assess data quality through dimensionality reduction (PCA, t-SNE) and cluster consistency metrics to ensure biological signals are preserved while technical artifacts are minimized.

Protocol 2: Multimodal Model Development with DLVPM

Objective: Implement the DLVPM framework to integrate genomic, histopathological, and clinical data for cancer outcome prediction.

Materials and Methods:

- Architecture Specification: Define measurement models for each modality:

- Genomic data: Fully connected neural networks with embedding layers

- Histopathology images: Convolutional Neural Networks (e.g., ResNet variants)

- Clinical data: Tabular neural networks or gradient boosting machines [14]

- Path Model Definition: Specify the hypothesized relationships between modalities based on cancer biology (e.g., genomic alterations → transcriptomic changes → histologic manifestations → clinical outcomes) [14].

- Model Training: Implement orthogonalization constraints to ensure DLVs capture complementary information:

where

Iis the identity matrix [14]. - Optimization: Use stochastic gradient descent with adaptive learning rates to maximize the association between connected modalities as defined in the path model.

Validation: Perform k-fold cross-validation and external validation on held-out datasets. Compare performance against unimodal baselines and alternative multimodal approaches using time-dependent AUC for survival prediction or standard AUC for classification tasks.

Protocol 3: Explainability and Biological Interpretation

Objective: Ensure model predictions are interpretable and biologically plausible.

Materials and Methods:

- Explainable AI Techniques: Implement SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations), LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations), and attention mechanisms to attribute predictions to input features [11] [17].

- Biological Validation: Correlate model-derived features with established cancer biomarkers and pathways. Perform gene set enrichment analysis on important genomic features identified by the model [11].

- Clinical Correlation: Assess whether model attention aligns with regions of interest identified by pathologists or radiologists through spatial correlation analysis [11].

Validation: Quantify explanation stability across similar patients and assess inter-rater reliability between model explanations and clinician annotations.

Performance Metrics and Comparative Analysis

Multimodal integration approaches have demonstrated significant improvements across various cancer types and clinical applications. The following tables summarize key performance metrics from recent studies:

Table 2: Performance of Multimodal AI in Cancer Diagnosis and Prognosis

| Cancer Type | Application | Data Modalities | Performance Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lung Cancer | Diagnosis | CT imaging, clinical data | Sensitivity: 0.86, Specificity: 0.86, AUC: 0.92 | [16] |

| Lung Cancer | Prognosis | Imaging, genomics, clinical | HR for OS: 2.53, HR for PFS: 2.80 | [16] |

| Breast Cancer | Treatment Response | Radiology, pathology, clinical | AUC: 0.91 for anti-HER2 therapy response | [12] |

| Multiple Cancers | Classification | Genomics, histopathology, clinical | 10-15% AUC improvement over unimodal baselines | [11] |

| Melanoma | Relapse Prediction | Histopathology, genomics, clinical | 5-year relapse prediction AUC: 0.833 | [10] |

Table 3: Comparison of Machine Learning Approaches for Cancer Research

| Method | Best For | Advantages | Limitations | Typical Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional ML | Structured data, limited samples | Interpretable, computationally efficient | Limited capacity for complex patterns | AUC: 0.76-0.84 [17] |

| Deep Learning | Unstructured data, large datasets | Automatic feature extraction, high accuracy | Data hunger, computational intensity | AUC: 0.87-0.94 [16] |

| Multimodal DL | Heterogeneous data integration | Captures cross-modal interactions, improved performance | Complex implementation, interpretability challenges | AUC: 0.89-0.94 [16] [10] |

| Foundation Models | Transfer learning, few-shot applications | Generalizable, scalable | Massive data requirements, specialization needed | Emerging evidence [13] |

Successful implementation of multimodal integration in cancer research requires leveraging specialized tools, datasets, and computational resources:

Table 4: Essential Resources for Multimodal Cancer Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Datasets | Key Features | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Public Datasets | The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) | Multi-omics, histopathology, clinical data across 33 cancer types | Model training, benchmarking, validation [14] |

| Public Datasets | UK Biobank | Multi-modal data from 500,000 participants, including imaging, genomics, health records | Epidemiological modeling, risk prediction [10] |

| Computational Frameworks | MONAI (Medical Open Network for AI) | PyTorch-based framework with pre-trained models for medical imaging | Image processing, model development [10] |

| Computational Frameworks | Deep Latent Variable Path Modelling | Combines deep learning with path modeling for multimodal integration | Mapping dependencies between data types [14] |

| Explainability Tools | SHAP, LIME | Model-agnostic interpretation methods for complex models | Feature importance analysis, model debugging [11] [17] |

| Clinical Data Tools | Electronic Health Record systems | Structured and unstructured clinical data | Patient stratification, outcome prediction [17] |

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite considerable progress, multimodal data integration in oncology faces several significant challenges:

Data Standardization and Harmonization: Heterogeneous data formats, batch effects, and platform-specific technical variations complicate integration efforts [12] [11]. Emerging solutions include adaptive normalization methods and reference-based harmonization protocols.

Computational Complexity: Processing and integrating large-scale multimodal datasets requires substantial computational resources and efficient algorithms [12] [13]. Distributed computing and specialized hardware acceleration offer promising pathways forward.

Interpretability and Trust: The "black box" nature of complex multimodal models hinders clinical adoption [11]. Explainable AI techniques that provide transparent, biologically plausible explanations are essential for building clinician trust and facilitating regulatory approval.

Data Privacy and Governance: Multimodal integration often requires pooling data from multiple institutions, raising concerns about patient privacy and data security [12]. Federated learning approaches that train models across decentralized data sources without sharing raw data represent a promising solution [11].

Future directions in multimodal integration include the development of large-scale foundation models pretrained on diverse cancer datasets [13], the incorporation of causal inference methods to move beyond correlations to mechanistic understanding [11], and the creation of "digital twins" that simulate cancer progression and treatment response for individual patients [11]. As these technologies mature, multimodal integration is poised to fundamentally transform oncology research and clinical practice, enabling truly personalized cancer care tailored to the unique biological characteristics of each patient and their disease.

Multimodal data integration represents a paradigm shift in cancer research, moving beyond single-modality analysis to a holistic approach that captures the complex, multi-scale nature of cancer biology. By leveraging advanced machine learning techniques to integrate genomic, imaging, and clinical data, researchers can achieve more accurate diagnosis, prognostication, and treatment selection than possible with any single data type alone. Frameworks like Deep Latent Variable Path Modelling provide powerful methodologies for mapping the complex dependencies between different data modalities, yielding insights into cancer mechanisms and improving patient outcomes.

While challenges remain in data standardization, computational complexity, and clinical interpretation, the rapid pace of innovation in multimodal AI suggests these barriers will be addressed in the coming years. As these technologies mature and validate in prospective clinical studies, multimodal integration is poised to become a cornerstone of precision oncology, enabling more personalized, effective, and timely cancer care. The continued development of robust, interpretable, and clinically actionable multimodal integration systems represents one of the most promising frontiers in the ongoing battle against cancer.

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) in cancer research represents a fundamental transformation in how we diagnose, treat, and understand cancer. This evolution has progressed from early neural networks capable of identifying simple patterns to contemporary large language models (LLMs) that can interpret the complex "language" of cancer biology. The field has matured from proof-of-concept demonstrations to clinically validated tools that are beginning to impact patient care. Early machine learning applications in oncology focused primarily on structured data analysis and basic image classification, but contemporary approaches now tackle multimodal data integration, survival prediction, and personalized treatment planning with increasing sophistication. This systematic review examines the architectural innovations, methodological refinements, and expanding applications that have characterized this journey, highlighting how each technological advance has addressed specific challenges in cancer research and clinical oncology.

The Early Era: Artificial Neural Networks in Oncology

Fundamental Architecture and Learning Principles

Early artificial neural networks (ANNs) represented the first practical implementation of brain-inspired computational models in medicine. These statistical models reproduced the biological organization of neural cells to simulate the learning dynamics of the brain through interconnected layers of logical units (perceptrons). A typical feedforward network contained at least three layers: an input layer that received datasets related to research questions, one or more hidden layers that synthesized this data through nonlinear transformations, and an output layer that generated answers to research questions [18].

The unique properties of ANNs included robust performance with noisy or incomplete input patterns, high fault tolerance, and the ability to generalize from training data. Unlike conventional programming, ANNs could solve problems without algorithmic solutions or where existing solutions were excessively complex. They could recognize linear patterns, non-linear patterns with threshold impacts, categorical, step-wise linear, and contingency effects without requiring initial hypotheses or a priori identification of key variables [18]. This capability proved particularly valuable in oncology, where prognostic factors might exist within masses of datasets but could have been overlooked in prior analyses.

Methodological Considerations and Implementation Challenges

Successful implementation of ANNs in early cancer research required careful attention to methodological details to avoid common pitfalls:

Overfitting Prevention: ANNs with excessive hidden layers or neurons could perfectly reconstruct input-target relationships in training data but failed to generalize to new samples. Researchers maintained parsimony by preferring small networks with single hidden layers, which mathematically could approximate any continuous function [18].

Data-to-Parameter Ratio: The number of ANN free parameters (connection weights) needed to be at least one order of magnitude less than the number of input-target patterns, preferably two orders of magnitude less, to ensure reliable model performance [18].

Training Validation: Independent data splits were essential, with separate samples for training, validation, and testing. The validation set determined when to stop training (e.g., when performance on validation data began decreasing), while the test set evaluated performance on completely independent data [18].

Ensemble Modeling: Due to variability from random initial weight choices, researchers conducted multiple runs with different initial weights, either selecting the best-performing ANN or averaging outputs to minimize variability [18].

Early Applications in Cancer Research

Initial ANN applications demonstrated promising results across various oncology domains, particularly in lung cancer research. Early systems focused on discrete tasks such as improving diagnostic efficacy for small cell lung cancer (SCLC) and predicting survival time in advanced cases [18]. Despite their potential, systematic assessments revealed that ANN implementations in medical literature often contained methodological inaccuracies, highlighting the need for closer cooperation between physicians and biostatisticians to determine and resolve these errors [18].

Table 1: Early ANN Applications in Lung Cancer Research

| Study Focus | Architecture | Key Outcome | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| SCLC Diagnosis | Feedforward ANN with backpropagation | Higher accuracy compared to conventional models | Limited dataset size |

| Advanced Lung Cancer Survival Prediction | Not specified | Accurate prediction of survival time | Single-institution data |

| Lung Cancer Detection | Multi-layer perceptron | Improved detection efficacy | Lack of external validation |

The Deep Learning Revolution: Convolutional Neural Networks in Cancer Imaging

Architectural Innovations and Technical Advantages

The advent of convolutional neural networks (CNNs) marked a revolutionary advance in cancer image analysis, particularly for histopathological imaging and radiological interpretation. CNNs demonstrated remarkable capability in automatically learning hierarchical feature representations directly from pixel data without relying on manual feature engineering [19]. This represented a significant departure from traditional machine learning approaches that depended on hand-crafted features whose performance was limited by feature selection and extraction methods [19].

CNN architectures effectively captured both local features and global context information through convolution and pooling operations [19]. This architectural superiority enabled CNNs to identify complex histopathological features in cancer diagnostics, including nuclear pleomorphism, nuclear-to-cytoplasm ratio, degree of cell arrangement disorder, and stromal response [19]. The capacity to learn these discriminative patterns directly from data positioned CNNs as the foundational technology for digital pathology and cancer image analysis.

Performance Benchmarks Across Cancer Types

CNN-based models have demonstrated exceptional performance across multiple cancer types, with particular success in breast cancer and gastrointestinal cancers.

Table 2: CNN Performance in Cancer Image Classification

| Cancer Type | Dataset | Model Architecture | Key Performance Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast Cancer | BreakHis v1 (Binary Classification) | ResNet50 | AUC: 0.999 | [20] |

| Breast Cancer | BreakHis v1 (Binary Classification) | RegNet | AUC: 0.999 | [20] |

| Breast Cancer | BreakHis v1 (Binary Classification) | ConvNeXT | Accuracy: 99.2%, Specificity: 99.6%, F1-score: 99.1%, AUC: 0.999 | [20] |

| Colorectal Cancer | MECC & TCGA | Custom CNN with Attention | F1-Score: 0.96, MCC: 0.92, AUC: 0.99 | [21] |

| Gastric Cancer | Multiple Datasets | Various CNNs | Accuracy up to 95% in detection tasks | [19] |

In breast cancer histopathological image classification, CNNs demonstrated near-perfect performance in binary classification tasks due to their relatively low complexity [20]. The best overall performance was achieved by ConvNeXT, which attained an accuracy of 99.2% (95% CI: 98.3%-1), a specificity of 99.6% (95% CI: 99.1%-1), an F1-score of 99.1% (95% CI: 98.0-1%), and an AUC of 0.999 (95% CI: 0.999-1) [20]. Similarly, in colorectal cancer detection, CNNs combining attention mechanisms with image downsampling achieved an F1-Score of 0.96, Matthews correlation coefficient of 0.92, and AUC of 0.99 on test datasets from The Cancer Genome Atlas [21].

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Standards

The implementation of CNNs in cancer research established new methodological standards that addressed the unique challenges of medical image analysis:

Whole Slide Image Processing: CNNs employed multiple instance learning (MIL) frameworks to handle gigapixel whole slide images (WSIs). The standard approach divided WSIs into smaller tiles (e.g., 256×256 pixels) for processing, then aggregated predictions at the patient level [21].

Resolution Optimization Studies: Systematic investigations evaluated the impact of image resolution on classification accuracy. Studies compared performance at different resolution levels (2 μm/pix, 4 μm/pix, 8 μm/pix, and 16 μm/pix) to balance computational constraints with diagnostic performance [21]. Optimal results for colorectal cancer detection were achieved at 4 μm/pix, demonstrating that computational costs could be significantly reduced while maintaining high performance standards [21].

Artefact Management and Bias Mitigation: Comprehensive analyses identified and quantified image artefacts (blurred areas, air bubbles, black regions, folds, pen marks) and assessed their distribution across tumor and normal classes to prevent algorithmic bias [21]. Statistical tests (Z-tests with Bonferroni correction) ensured that artefact distributions didn't significantly differ between classes, preventing models from relying on confounding features [21].

Diagram 1: CNN Histopathology Analysis Workflow

The Transformer Revolution: Attention Mechanisms in Cancer Data

Architectural Fundamentals and Technical Innovations

The introduction of transformer architectures with self-attention mechanisms represented another paradigm shift in cancer AI applications. Unlike CNNs that processed images through hierarchical feature extraction, transformers utilized self-attention mechanisms to weigh the importance of different elements in input data when making predictions [22]. This architecture proved particularly adept at capturing long-range dependencies and contextual relationships within complex datasets.

The core innovation of transformers lay in their attention mechanisms, which allowed models to dynamically focus on the most relevant parts of the input sequence regardless of their positional relationships. This capability translated exceptionally well to cancer genomics and transcriptomics, where understanding interactions between distant genetic elements proved crucial for interpreting regulatory patterns and functional genomics [23].

Transformer Applications in Cancer Genomics

Transformers spawned a new class of genome large language models (Gene-LLMs) capable of interpreting nucleotide sequences at unprecedented scale and resolution [23]. These models treated DNA and RNA sequences as biological language, using self-supervised pretraining to decipher complex regulatory grammars hidden within the genome.

Gene-LLMs employed specialized tokenization strategies, typically using k-mer tokenization to segment long DNA and RNA sequences into overlapping fragments of length K (e.g., "ATGCGA") [23]. This approach, analogous to subword tokenization in natural language processing, enabled models to capture contextual relationships between nucleotides and identify functional genomic elements. Applications included enhancer and promoter identification, chromatin state modeling, RNA-protein interaction prediction, and synthetic sequence generation [23].

Performance in Histopathological Image Classification

In breast cancer histopathology, transformer-based foundation models demonstrated remarkable capabilities, particularly in complex multi-class classification scenarios. In the challenging eight-class classification task on the BreakHis dataset, the fine-tuned foundation model UNI achieved accuracy of 95.5% (95% CI: 94.4-96.6%), specificity of 95.6% (95% CI: 94.2-96.9%), F1-score of 95.0% (95% CI: 93.9-96.1%), and AUC of 0.998 (95% CI: 0.997-0.999) [20].

A critical finding was that foundation model encoders performed poorly without task-specific fine-tuning, but with simple adaptation, they quickly achieved excellent results [20]. This demonstrated that with minimal customization, foundation models could become valuable tools in digital pathology, especially for complex diagnostic scenarios requiring nuanced differentiation between multiple cancer subtypes.

Table 3: Transformer vs. CNN Performance in Breast Cancer Classification

| Model Type | Best Performing Model | Binary Classification AUC | Multi-class Classification Accuracy | Computational Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNN-based | ConvNeXT | 0.999 | Not reported | High |

| Transformer-based | UNI (fine-tuned) | 0.999 | 95.5% | Moderate |

| Foundation Models | UNI (zero-shot) | Limited performance | Limited performance | Variable |

Contemporary Landscape: Large Language Models and Foundation Models

Definition and Technical Capabilities

Large language models (LLMs) and foundation models represent the most recent evolution in cancer AI, leveraging massive pretraining on diverse datasets to develop broad capabilities that can be adapted to specialized oncology tasks through fine-tuning. Foundation models are "pretrained" on vast amounts of data from disparate sources, learning to identify objects from input data. Through "transfer learning," their recognition capacities can be fine-tuned for specific downstream tasks, such as recognizing cancer cells from whole slide images [22].

These models support "self-supervised" learning, where pretraining tasks are derived automatically from unannotated data - a particularly promising feature for oncology datasets where expert annotations are scarce and expensive to obtain [22]. Critically, foundation models can accommodate multiple data types (text, imaging, pathology, molecular biology), incorporating them into multimodal analyses that have profound implications for clinical decision-making in oncology [22].

Multimodal Integration and Clinical Applications

Contemporary foundation models excel at integrating diverse data modalities that are essential for comprehensive cancer analysis:

Genomic Sequencing Data: Gene-LLMs process raw nucleotide sequences, gene expression data, and multi-omic annotations to decipher complex biological relationships [23].

Histopathological Images: Vision transformers analyze whole slide images, identifying subtle morphological patterns that may escape human detection [20] [22].

Clinical Text and EHR Data: NLP transformers extract relevant information from clinical notes, pathology reports, and scientific literature to provide clinical context [22].

Molecular Profiling Data: Multimodal transformers integrate proteomic, metabolomic, and spatial transcriptomic data to build comprehensive molecular portraits of tumors [22].

This multimodal capability enables applications in precision immuno-oncology, where AI/ML analyzes complex 'omics data alongside clinical, pathological, treatment, and outcome information to optimize biomarker development and treatment selection for patients [22].

Implementation in Cancer Drug Discovery and Clinical Trials

LLMs are revolutionizing cancer drug discovery and clinical trial methodologies through several mechanisms:

Synthetic Data Generation: Foundation models can generate synthetic patient data, including digital twins, to provide necessary information for designing or expediting clinical trials [22].

Trial Optimization: AI systems streamline trial design, analysis, and participant recruitment, potentially creating exponential impacts on therapeutic development [24].

Literature Mining: LLMs such as GPT variants enhance knowledge extraction from scientific literature and clinical text, accelerating hypothesis generation in cancer research [1].

Protein Structure Prediction: Tools like AlphaFold2, utilizing deep learning, enhance speed and precision in drug target identification through breakthroughs in understanding protein structure [24].

Diagram 2: Foundation Model Multimodal Integration

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources in Cancer AI

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Public Cancer Datasets | BreakHis v1, TCGA, MECC | Provide annotated histopathological images for model training and validation | BreakHis: 7,909 images; TCGA: 1,349 WSIs; MECC: ~1,317 WSIs [20] [21] |

| Genomic Data Repositories | CAGI5, GenBench, NT-Bench, BEACON | Benchmarking and validation of genomic AI models | Standardized datasets for model performance evaluation [23] |

| Deep Learning Frameworks | TensorFlow, PyTorch | Model development and training infrastructure | Support for CNN, transformer, and foundation model architectures |

| Computational Infrastructure | High-performance GPUs | Accelerate model training and inference | Essential for processing large WSIs and genomic sequences [21] |

| Whole Slide Imaging Systems | Digital slide scanners | Digitize histopathological specimens for computational analysis | 40x magnification, 0.25 μm/pix resolution [21] |

| Tokenization Tools | K-mer tokenizers | Segment genomic sequences for transformer processing | Convert DNA/RNA sequences to model-readable tokens [23] |

| Multiple Instance Learning Frameworks | Custom MIL implementations | Handle gigapixel whole slide images | Enable patient-level predictions from image tiles [21] |

Comparative Performance Analysis and Clinical Validation

Cross-Architecture Performance Benchmarking

Systematic comparisons of multiple architectures across standardized datasets provide critical insights for model selection in cancer research applications. A comprehensive evaluation of 14 deep learning models on breast cancer histopathological images revealed distinct performance patterns across architectural paradigms [20].

In binary classification tasks, where diagnostic decision-making is most straightforward, both CNN-based models (ResNet50, RegNet, ConvNeXT) and transformer-based foundation models (UNI) achieved exceptional performance with AUC scores of 0.999 [20]. However, in more complex eight-class classification tasks requiring nuanced differentiation between cancer subtypes, performance disparities became more pronounced, with the fine-tuned foundation model UNI achieving superior performance (95.5% accuracy) compared to other architectures [20].

Clinical Workflow Integration and Validation

Successful implementation of AI models in cancer research requires rigorous validation within clinical workflows:

External Validation: Models must demonstrate generalizability across independent datasets from different institutions. For example, colorectal cancer detection models trained on the MECC dataset were validated on TCGA datasets to ensure robustness [21].

Artefact Robustness: Real-world clinical images contain various artefacts (blurred areas, air bubbles, pen marks, folds). Comprehensive analyses quantify artefact distributions across classes to prevent algorithmic bias [21].

Resolution Optimization: Systematic studies evaluate performance across resolution levels (2 μm/pix to 16 μm/pix) to balance computational efficiency with diagnostic accuracy [21].

Clinical Workflow Integration: AI systems must integrate seamlessly with existing clinical protocols, combining different paradigms to produce transparent reasoning structures that can be evaluated in real clinical environments [18].

The historical evolution from early neural networks to contemporary LLMs has fundamentally transformed the landscape of cancer research. Early ANNs established the foundation for nonlinear pattern recognition in oncology data but faced limitations in handling complex image data and genomic sequences. The convolutional neural network revolution enabled automated feature learning from histopathological images, achieving diagnostic performance comparable to human experts in controlled settings. The subsequent transformer revolution introduced attention mechanisms that excelled at capturing long-range dependencies in both image and genomic data. Finally, contemporary foundation models and LLMs now enable multimodal integration across diverse data types, creating unprecedented opportunities for comprehensive tumor characterization and personalized treatment optimization.

Future research directions include federated learning approaches to leverage distributed data while maintaining privacy, enhanced multimodal modeling that seamlessly integrates genomic, image, and clinical data, improved interpretability methods to build clinical trust, and specialized adaptation for rare cancer variants where data scarcity presents particular challenges [23]. As these technologies continue to mature, their thoughtful integration into clinical workflows holds immense promise for advancing cancer diagnosis, treatment selection, and ultimately patient outcomes.

Cancer remains a principal cause of mortality worldwide, with projections estimating approximately 35 million cases by 2050 [1]. This alarming rise highlights the imperative to accelerate progress in cancer research and therapeutic development. Traditional approaches in oncology face significant challenges: drug discovery pipelines are time-intensive and resource-heavy, often requiring over a decade and billions of dollars to bring a single drug to market, with an estimated 90% of oncology drugs failing during clinical development [25]. Simultaneously, diagnostic and prognostic methods often lack the precision needed for personalized care, particularly in complex malignancies like lung cancer [16].

Artificial intelligence is rapidly revolutionizing the landscape of oncological research and personalized clinical interventions [1]. Progress in three interconnected areas—development of methods and algorithms for training AI models, evolution of specialized computing hardware, and increased access to large volumes of cancer data (imaging, genomics, clinical information)—has converged to create promising new applications across the cancer care continuum [1] [26]. When applied ethically and scientifically, these AI-driven approaches hold promise for accelerating progress in cancer research and ultimately fostering improved health outcomes for all populations [1].

Quantitative Evidence of AI Performance in Oncology

Empirical studies and meta-analyses demonstrate AI's robust performance across diagnostic and prognostic tasks in oncology. The following tables summarize key quantitative findings from recent research.

Table 1: Performance of AI Systems in Cancer Detection and Diagnosis

| Cancer Type | Modality | Task | AI System | Sensitivity | Specificity | AUC | Evidence Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colorectal | Colonoscopy | Malignancy detection | CRCNet | 91.3% (vs. 83.8% human) | 85.3% | 0.882 | Retrospective multicohort with external validation [1] |

| Colorectal | Colonoscopy/Histopathology | Histological classification | Real-time image recognition | 95.9% | 93.3% | NR | Prospective diagnostic accuracy [1] |

| Breast | 2D Mammography | Screening detection | Ensemble of 3 DL models | +2.7% to +9.4% vs. radiologists | +1.2% to +5.7% vs. radiologists | 0.810-0.889 | Diagnostic case-control [1] |

| Lung | CT Imaging | Diagnosis (Multiple studies) | Various AI algorithms | 0.86 (0.84-0.87) | 0.86 (0.84-0.87) | 0.92 (0.90-0.94) | Meta-analysis of 209 studies [16] |

Table 2: AI Performance in Prognostic Prediction and Molecular Profiling

| Domain | Cancer Types | Task | AI System | Performance | Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survival Prediction | Multiple (17 institutions) | Distinguishing short-term vs. long-term survival | CHIEF | Outperformed other models by 8-10% | 32 datasets from 24 hospitals [27] |

| Risk Stratification | Lung | Predicting high vs. low risk (OS) | Various AI models | HR: 2.53 (2.22-2.89) | Meta-analysis of 44 datasets [16] |

| Molecular Profiling | Multiple (19 types) | Predicting 54 gene mutations | CHIEF | >70% accuracy (96% for EZH2 in DLBCL) | Cross-hospital validation [27] |

| Treatment Response | Multiple | Identifying immunotherapy responders | CHIEF | High accuracy for key mutations | International cohorts [27] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Frameworks

Foundation Model Development: The CHIEF Framework

The Clinical Histopathology Imaging Evaluation Foundation (CHIEF) represents a versatile, ChatGPT-like AI model capable of performing multiple diagnostic tasks across cancer types [27]. Its development protocol exemplifies rigorous AI methodology:

Data Curation and Preprocessing:

- Training on 15 million unlabeled images chunked into sections of interest

- Further training on 60,000 whole-slide images from 19 cancer types

- Samples included lung, breast, prostate, colorectal, gastric, and other major cancers

- Integration of data from multiple acquisition methods (biopsy, surgical excision) and digitization techniques

Architecture and Training:

- Holistic image interpretation combining specific regions with overall context

- Training to relate specific changes in one region to broader contextual patterns

- Validation on more than 19,400 whole-slide images from 32 independent datasets

- Testing across 24 hospitals and patient cohorts globally

Performance Validation:

- Cancer detection: 94% accuracy across 15 datasets with 11 cancer types

- Biopsy specimens: 96% accuracy across esophageal, gastric, colon, and prostate cancers

- Surgical specimens: >90% accuracy for colon, lung, breast, endometrial, and cervical tumors

- Molecular profile prediction: >70% accuracy for 54 commonly mutated cancer genes

This protocol demonstrates the comprehensive approach required for developing robust AI systems in oncology, emphasizing multi-site validation and diverse data integration [27].

Meta-Analysis Protocol for Lung Cancer AI Assessment

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis established rigorous methodology for evaluating AI's role in lung cancer management [16]:

Literature Search and Screening:

- Initial identification of 18,905 records from major databases

- Exclusion of 8,130 duplicates followed by title/abstract screening of 10,775 records

- Full-text assessment of 1,312 articles

- Final inclusion of 315 articles meeting quality criteria

Quality Assessment:

- Application of QUADAS-AI tool for diagnostic accuracy studies

- Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for prognostic studies (scores 5-9, median 8)

- Evaluation of risk of bias across patient selection, reference standard, and flow/timing

- Exclusion of studies presenting only training performance without validation

Data Extraction and Analysis:

- Extraction of sensitivity, specificity, and AUC values from 209 diagnostic studies

- Hazard ratio extraction from 53 prognostic studies for overall survival, progression-free survival, disease-free survival, and recurrence-free survival

- Subgroup analyses based on study objectives, AI algorithms, validation cohorts, and imaging quality control

- Statistical synthesis using random-effects models to account for heterogeneity

This protocol provides a template for rigorous evidence synthesis in AI oncology applications, emphasizing transparency, quality assessment, and comprehensive performance evaluation [16].

Visualization of AI Workflows in Oncology

AI Model Development and Validation Pipeline

Multi-Scale AI Analysis in Cancer Pathology

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Resources for AI Oncology

| Resource Type | Specific Examples | Function in AI Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Public Datasets | The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) | Provides multi-omics data for target identification and model training | Pan-cancer analysis, biomarker discovery [25] |

| Imaging Databases | National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) | LDCT images for lung cancer detection algorithm development | Screening and early detection models [26] |

| AI Frameworks | TensorFlow, PyTorch | Deep learning model development and training | Custom architecture implementation [1] |

| Validation Cohorts | Independent hospital datasets | External validation of model generalizability | Performance benchmarking [16] |

| Pathology Resources | Whole slide images (WSI) | Digital pathology analysis and feature extraction | Diagnostic classification, outcome prediction [27] |

| Genomic Tools | Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) data | Liquid biopsy analysis for monitoring and biomarker discovery | Minimal residual disease detection [25] |

| Clinical Data | Electronic Health Records (EHR) | Real-world evidence generation and outcome correlation | Predictive model validation [26] |

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite promising results, several challenges impede widespread clinical integration of AI in oncology. Data quality and availability remain fundamental constraints, as AI models are only as robust as the data they're trained on [25]. The "black box" nature of many deep learning algorithms creates interpretability challenges, limiting mechanistic insight and clinical trust [25] [4]. Model generalizability across diverse populations and healthcare settings requires further validation, with most current studies exhibiting retrospective designs [16]. Ethical considerations around data privacy, algorithmic bias, and regulatory compliance must be addressed through frameworks like federated learning and explainable AI (XAI) techniques [4].

Future progress depends on advancing multi-modal AI integration, combining genomic, imaging, and clinical data for more holistic insights [4]. Digital twins—virtual patient simulations—may enable virtual drug testing before clinical trials [25]. Federated learning approaches can enhance data diversity while preserving privacy [25]. Prospective multicenter validation studies and randomized controlled trials are essential to demonstrate real-world clinical utility and patient benefit [26]. As these technologies mature, their integration throughout the oncology pipeline promises to accelerate progress against cancer, ultimately delivering more personalized, effective care to patients globally.

ML in Action: Transforming Cancer Diagnosis, Prognosis, and Treatment

The integration of deep learning (DL) into medical imaging represents a paradigm shift in oncology, enhancing the precision of tumor detection, diagnosis, and treatment planning. This transformation is critical within a broader research context where machine learning is systematically reviewed for its impact on cancer outcomes. Deep learning techniques, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and transformer models, are now capable of analyzing complex imaging data from computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and histopathology with a level of speed and accuracy that augments human expertise [28]. These technologies have demonstrated significant utility across the cancer care continuum, from automated lesion detection and segmentation in radiology to prognostic assessments and molecular subtype prediction in digital pathology [28] [29]. Framed within a systematic review of machine learning in cancer research, this technical guide synthesizes current advancements, evaluates methodological frameworks, and details the experimental protocols that are establishing new benchmarks in oncologic imaging. The following sections provide a comprehensive examination of the core architectures, quantitative performance, and practical implementation requirements driving this field forward.

Core Deep Learning Architectures and Their Technical Implementation

The application of deep learning in medical imaging for tumor detection is underpinned by several sophisticated neural network architectures, each chosen for its specific strengths in handling high-dimensional image data. The foundational architecture is the Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), which excels at extracting hierarchical spatial features through its convolutional and pooling layers. CNNs have become the dominant technology in medical image processing, enabling the automated identification of complex imaging patterns and improving diagnostic precision [28]. Specific variants like U-Net and DeepLabV3+ have been successfully applied to tumor boundary recognition and organ segmentation in MRI and CT images, achieving high accuracy in brain tumor, lung lesion, liver cancer, and prostate cancer imaging [28].

More recently, Vision Transformers (ViTs) have emerged as powerful alternatives or complements to CNNs, particularly due to their ability to capture global contextual relationships within an image through self-attention mechanisms. While CNNs prioritize pixel-level information, transformers analyze the entire image at once and identify long-range dependencies between features, making them ideal for tasks requiring a comprehensive understanding of histopathological images [30]. However, pure transformer architectures can struggle with extracting fine-grained details, leading to the development of hybrid models that leverage the strengths of both approaches.

A notable example is a hybrid 2D-3D CNN-Transformer architecture proposed for brain tumor grading. In this framework, 3D CNN processes multi-scale stain decompositions to capture spatial-spectral patterns, while the Transformer focuses on diagnostically critical regions via self-attention. This synergy enables precise, interpretable grading while maintaining computational efficiency [30]. Another advanced implementation is the MBTC-Net framework for multimodal brain tumor classification, which leverages EfficientNetV2B0 for extracting high-dimensional feature maps, followed by reshaping into sequences and applying multi-head attention to capture contextual dependencies [31].

For whole-slide image (WSI) analysis in digital pathology, multiple-instance learning (MIL) approaches have gained prominence. These models address the challenge of gigapixel-sized images by processing numerous small patches and using attention mechanisms to combine features without requiring detailed pixel-level annotations. The SMMILe (Superpatch-based Measurable Multiple Instance Learning) algorithm exemplifies this approach, enabling precise spatial quantification of tumor tissue on digital pathology images using only slide-level labels for training [32].

Table 1: Core Deep Learning Architectures in Oncologic Imaging

| Architecture | Key Strengths | Common Applications | Notable Implementations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) | Local feature extraction, hierarchical pattern recognition | Lesion detection, tumor segmentation, image classification | U-Net, DeepLabV3+, EfficientNetV2B0 [28] [31] |

| Vision Transformers (ViTs) | Global context understanding, long-range dependency modeling | Whole-slide image analysis, tumor grading | Pure ViT architectures for molecular marker prediction [30] |

| Hybrid CNN-Transformer | Combines local feature extraction with global context | Brain tumor grading, multimodal classification | 2D-3D CNN-Transformer with stacking classifiers [30] |

| Multiple-Instance Learning (MIL) | Handles gigapixel images with weak supervision | Spatial quantification in digital pathology | SMMILe framework for tumor microenvironment analysis [32] |

Diagram 1: Hybrid CNN-Transformer workflow for tumor detection (76 characters)

Quantitative Performance Analysis Across Imaging Modalities

Rigorous evaluation of deep learning models across various cancer types and imaging modalities has demonstrated consistently high performance, though with notable variations in sensitivity and specificity across applications. The quantitative evidence supporting DL implementation comes primarily from retrospective studies and meta-analyses comparing algorithm performance against clinical standards and radiologist interpretations.

In digital pathology, DL algorithms show remarkable capability in predicting molecular alterations directly from hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained whole-slide images. A meta-analysis of deep learning for detecting microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) in colorectal cancer comprising 33,383 samples reported a pooled sensitivity of 0.88 and specificity of 0.86 in internal validation, with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.94 [29]. Performance remained strong in external validation, though specificity decreased to 0.71, indicating challenges with generalizability. For brain tumor grading, a hybrid 2D-3D CNN-Transformer model combined with stacking classifiers achieved exceptional performance, reaching an average accuracy of 97.1%, precision of 97.1%, and specificity of 97.0% on the TCGA dataset [30].

In radiology applications, DL models have demonstrated particular strength in thyroid cancer detection. A systematic review and meta-analysis of 41 studies found that for thyroid nodule detection tasks, DL algorithms achieved a pooled sensitivity of 91%, specificity of 89%, and AUC of 0.96 [33]. Segmentation tasks for thyroid nodules showed slightly lower sensitivity (82%) but higher specificity (95%) [33]. The application of transfer learning was identified as a significant factor contributing to improved model performance across studies.

For breast cancer screening, research indicates that DL models can achieve high sensitivity (93%) in digital breast tomosynthesis (DBT)-based AI systems, with the additional benefit that AI scores may serve as imaging biomarkers associated with histologic grade and lymph node status [34]. However, studies have highlighted a critical limitation: most DL models for breast cancer detection are trained predominantly on Caucasian datasets, creating significant performance limitations when applied to Asian populations due to demographic differences in breast density and imaging characteristics [35].

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Deep Learning Models Across Cancer Types

| Cancer Type | Imaging Modality | Sensitivity (Pooled) | Specificity (Pooled) | AUC | Sample Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colorectal Cancer (MSI-H) | Histopathology (WSI) | 0.88 (Internal) 0.93 (External) | 0.86 (Internal) 0.71 (External) | 0.94 (Internal) | 33,383 samples [29] |

| Thyroid Cancer | Ultrasound | 0.91 (Detection) 0.82 (Segmentation) | 0.89 (Detection) 0.95 (Segmentation) | 0.96 (Detection) | 41 studies [33] |

| Brain Tumor | Histopathology (WSI) | N/R | N/R | N/R | TCGA Dataset [30] |

| Breast Cancer | Digital Breast Tomosynthesis | 0.93 | N/R | N/R | Multiple studies [34] [35] |

N/R: Not Reported in the aggregated data

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Whole-Slide Image Analysis for Molecular Phenotype Prediction

The prediction of molecular phenotypes from routine histopathology images represents one of the most significant advances in computational pathology. The following protocol outlines the methodology for developing a DL model to detect microsatellite instability (MSI) status in colorectal cancer from H&E-stained whole-slide images (WSIs), based on approaches validated in large-scale studies [29]:

Data Curation and Preprocessing:

- Collect formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) H&E-stained WSIs from colorectal cancer resection specimens, with corresponding MSI status determined by PCR or immunohistochemistry (IHC).

- Exclude slides with poor staining quality, extensive necrosis, or insufficient tumor content (<10% tumor cellularity).

- Perform quality control through pathologist review to annotate tumor regions, either through detailed segmentation or rough bounding boxes.

- Split data into training, validation, and test sets at the patient level to prevent data leakage, ensuring slides from the same patient remain in the same split.

Image Processing and Patch Extraction:

- Load WSIs at multiple magnification levels (typically 5×, 10×, 20×) using openslide or similar libraries.

- Extract patches of size 256×256 or 512×512 pixels from tumor-rich regions identified through annotations or automated tumor detection.

- Apply stain normalization (e.g., Macenko method) to minimize inter-institutional staining variation.

- Implement data augmentation techniques including rotation, flipping, color jittering, and elastic transformations during training.

Model Architecture and Training:

- Employ a multiple-instance learning (MIL) framework where each WSI is treated as a "bag" of patches (instances).

- Utilize a pre-trained CNN (e.g., ResNet50) as a feature extractor for each patch, followed by an attention mechanism to weight the importance of different patches.

- Aggregate patch-level features into a slide-level representation using an attention-based pooling mechanism.

- Implement a final classification layer with sigmoid activation for MSI-H vs. MSS prediction.

- Train with weighted binary cross-entropy loss to address class imbalance, using Adam optimizer with an initial learning rate of 1e-4 and early stopping based on validation loss.

Validation and Interpretation:

- Perform internal validation on held-out test sets from the same institution and external validation on completely independent cohorts from different institutions.

- Generate attention maps to visualize which regions of the slide contributed most to the prediction, enabling pathological correlation.

- Calculate performance metrics including AUC, sensitivity, specificity, and precision-recall curves.

This protocol has demonstrated robust performance in multiple studies, with one meta-analysis reporting a pooled sensitivity of 0.88 and specificity of 0.86 in internal validation [29].

Multimodal Fusion for Brain Tumor Classification

The integration of multiple imaging modalities significantly enhances tumor characterization, as demonstrated by the MBTC-Net framework for multimodal brain tumor classification from CT and MRI scans [31]:

Multimodal Data Registration and Preprocessing:

- Collect paired CT and MRI scans (T1-weighted, T1 Contrast-Enhanced, T2-weighted) from patients with brain tumors.

- Perform rigid or non-rigid registration to align different modalities to a common coordinate space.

- Apply skull-stripping, intensity normalization, and bias field correction to standardize images across patients.

- Resample all images to isotropic resolution (e.g., 1mm³) and crop or pad to uniform dimensions.

Multimodal Feature Extraction:

- Implement a dual-stream architecture with shared-weight EfficientNetV2B0 backbones for each modality.

- Extract high-dimensional feature maps from each modality separately in parallel streams.

- Reshape 2D feature maps into sequence representations suitable for attention mechanisms.

- Apply multi-head attention to capture contextual dependencies within and across modalities.

Feature Fusion and Classification:

- Concatenate features from all modalities into a unified representation.

- Reintroduce the attention output into a spatial structure and perform global average pooling.

- Pass through dense layers with batch normalization and dropout (rate=0.5) for regularization.

- Use Adamax optimizer and softmax activation for final tumor classification.

- Implement stratified 5-fold cross-validation to ensure robust performance estimation.

This protocol achieved accuracies of 97.54% (15-class), 97.97% (6-class), and 99.34% (2-class) on open-access multimodal brain tumor datasets [31].

Diagram 2: Multimodal fusion for brain tumor classification (76 characters)

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials and Computational Tools

The implementation of deep learning frameworks for tumor detection requires both computational resources and specialized data sources. The following table details key components of the research toolkit for developing and validating these systems.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Category | Specific Resource | Application/Function | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Public Datasets | The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) | Whole-slide images with molecular data for multiple cancer types | Provides paired histopathology and genomic data [29] [30] |

| DeepHisto | Brain tumor histopathology images for grading | Used for cross-dataset validation [30] | |

| Kaggle Brain Tumor Datasets | Multimodal MRI and CT scans | Includes T1, T1-CE, T2 sequences [31] | |

| Software Libraries | PyTorch / TensorFlow | Deep learning framework for model development | Enables custom architecture implementation [31] [30] |

| OpenSlide | Whole-slide image processing and patch extraction | Handles gigapixel digital pathology files [32] | |

| Computational Infrastructure | GPU Clusters (NVIDIA) | Model training and inference acceleration | Essential for processing 3D volumes and WSIs [28] |

| Pre-trained Models | ImageNet Pre-trained CNNs | Transfer learning for medical image analysis | Improves performance with limited medical data [28] [33] |

| Validation Frameworks | QUADAS-AI / QUADAS-2 | Quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies | Standardized evaluation of model performance [29] [33] |

Challenges and Future Research Directions