A Modern Workflow for Mathematical Modeling in Cancer Treatment Optimization: From Biological Principles to Clinical Translation

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the workflow of mathematical modeling for optimizing cancer treatment, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

A Modern Workflow for Mathematical Modeling in Cancer Treatment Optimization: From Biological Principles to Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the workflow of mathematical modeling for optimizing cancer treatment, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of mathematical oncology, detailing how mathematical models simulate tumor growth, treatment response, and the emergence of resistance. The content covers the step-by-step methodological process of model building, from conceptualization and equation selection to implementation and simulation. It further addresses critical challenges in model calibration and optimization, including parameter estimation and overcoming resistance. Finally, the article discusses the essential processes of model validation, comparative analysis of different modeling approaches, and the translation of these models into clinical trials and decision-support tools, synthesizing the latest research and clinical applications in this rapidly advancing field.

Laying the Groundwork: Core Principles and Biological Complexity in Mathematical Oncology

Defining Mathematical Oncology and Its Role in Treatment Optimization

Mathematical Oncology is a growing interdisciplinary discipline that integrates mechanistic mathematical models with experimental and clinical data to improve clinical decision-making in oncology [1]. These models are typically based on biological first principles to capture the spatial and temporal dynamics of tumors, their microenvironment, and response to treatment [1]. This approach stands in contrast to purely data-driven artificial intelligence methods, as it seeks to represent the underlying biological processes that drive cancer progression and treatment response, thereby providing a predictive framework that can simulate the complex, multi-scale, and dynamic nature of cancer [1] [2].

The field has evolved from using simple models of tumor growth and dose-response to increasingly complex frameworks that incorporate tumor heterogeneity, ecological interactions (such as tumor-immune dynamics), and evolutionary principles (including the emergence of treatment resistance) [1]. This mechanistic understanding allows researchers and clinicians to move beyond the traditional 'maximum tolerated dose' (MTD) paradigm, which often leads to disease relapse due to drug resistance, and toward more adaptive, personalized treatment strategies [1]. As such, mathematical oncology provides a quantitative foundation for predicting treatment outcomes, optimizing therapeutic strategies, and ultimately improving patient care.

Foundational Mathematical Frameworks

Mathematical oncology employs a diverse set of modeling frameworks to describe different aspects of cancer behavior and treatment response. The choice of model depends on the specific research question, the scale of investigation, and the available data. The table below summarizes the key model types and their primary applications in treatment optimization.

Table 1: Key Mathematical Modeling Frameworks in Oncology

| Model Type | Mathematical Formulation | Primary Oncology Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs) | ( \frac{dN}{dt} = rN(1-\frac{N}{K}) ) (Logistic Growth) [2] | Modeling tumor population dynamics, pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics, and competition between sensitive and resistant cell populations [1] [2]. |

| Partial Differential Equations (PDEs) | ( \frac{\partial C}{\partial t} = D\nabla^2 C + \rho C ) (Reaction-Diffusion) [3] | Simulating spatially explicit phenomena like tumor invasion, nutrient gradients, and the spatial distribution of treatment agents [2] [3]. |

| Agent-Based Models (ABMs) | Rule-based systems where individual cell behaviors (proliferation, death, migration) are simulated. | Investigating the emergence of tissue-level patterns from individual cell interactions, tumor heterogeneity, and evolutionary dynamics in a spatial context [2]. |

| Population Dynamics & Evolutionary Models | ( \frac{dN1}{dt} = r1N1(1-\frac{N1 + \alpha N2}{K1}) ) (Lotka-Volterra Competition) [2] | Modeling clonal evolution, emergence of treatment resistance, and designing evolutionary-informed therapies like adaptive therapy [1] [2]. |

These models are calibrated using preclinical or clinical data. A particular strength of mechanistic models is their ability to capture heterogeneity across different scales (e.g., between patients or tumors) by adjusting parameter sets to reflect observed variability [1]. Once calibrated, these models can simulate various treatment scenarios to predict outcomes and recommend optimal dosing, timing, and drug combinations, thereby bridging the gap between experimental insight and clinical application [1].

Clinical Applications and Trial Evidence

Mathematical models are increasingly being integrated into clinical workflows and clinical trials to personalize and optimize treatment. The following table summarizes key examples of model-informed clinical trials, demonstrating the translation of mathematical concepts into patient care.

Table 2: Examples of Mathematical Model-Informed Clinical Trials in Oncology

| Therapeutic Strategy / Model Type | Trial Identifier | Cancer Type | Intervention / Purpose | Status/Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adaptive Therapy | NCT02415621 [1] | Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer | Adaptive Abiraterone Therapy | Active, not recruiting |

| Adaptive Therapy | NCT03543969 [1] | Advanced BRAF Mutant Melanoma | Adaptive BRAF-MEK Inhibitor Therapy | Active, not recruiting |

| Adaptive Therapy | NCT05393791 [1] | Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer (mCRPC) | Adaptive vs. Continuous Abiraterone or Enzalutamide (ANZadapt) | Recruiting |

| Extinction Therapy | NCT04388839 [1] | Rhabdomyosarcoma | Evolutionary Therapy | Recruiting |

| Dynamics-based Radiotherapy | NCT03557372 [1] | Glioblastoma (GBM) | Mathematical Model-Adapted Radiation | Phase 1: Feasibility and Safety ✓ |

| Fully Personalized Treatment | NCT04343365 [1] | Multiple Cancers | Evolutionary Tumor Board (ETB) | Recruiting |

Case Study: Glioblastoma Treatment Planning

A concrete example of treatment optimization is the use of a reaction-diffusion model to simulate glioblastoma (GBM) progression for patient counseling [3]. In this approach, patient-specific MRI data (T1 post-contrast and T2/FLAIR sequences) are co-registered and manually segmented to identify enhancing tumor and edema, forming the initial conditions for the model [3]. The model, known as the "ASU-Barrow" model, then simulates tumor growth between successive scans by systematically sampling parameters to generate a range of realistic scenarios of tumor response to treatment [3].

In a validation study using 132 MRI intervals from 46 GBM patients, the model-generated scenarios for changes in tumor volumes approximated the observed ranges in the patient data with reasonable accuracy. In 86% of the imaging intervals, at least one simulated scenario agreed with the observed tumor volume to within 20% [3]. This approach, with its modest computational needs, demonstrates the potential for mathematical models to become clinically practical tools that support shared decision-making between clinicians and patients facing a poor prognosis [3].

Diagram 1: GBM Modeling Workflow

Experimental Protocols for Model Calibration and Validation

Protocol: Quantifying Drug Dose-Response for Model Input

A critical step in building predictive models is the accurate quantification of drug effects on cancer cells. This protocol outlines the standard method for determining the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (ICâ‚…â‚€), a key parameter used in pharmacodynamic models of treatment response [4].

1. Objective: To generate a concentration-response curve for a cancer therapeutic and determine its ICâ‚…â‚€ value in a relevant cellular model.

2. Materials:

- Cancer Cell Lines: (e.g., patient-derived cell lines relevant to the cancer type).

- Therapeutic Agent: The drug of interest, prepared in appropriate solvent at a high stock concentration.

- Cell Culture Reagents: Complete growth medium, trypsin-EDTA, phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

- Viability Assay Reagent: Such as CellTiter-Glo (ATP-based luminescent assay) [4].

- Equipment: Tissue culture hood, COâ‚‚ incubator, multi-channel pipettes, white-walled 96-well or 384-well assay plates, microplate reader capable of detecting luminescence.

3. Procedure: 1. Cell Seeding: Harvest exponentially growing cells and prepare a suspension in complete medium. Seed a consistent number of cells (e.g., 1,000-5,000 cells in 80-90 µL of medium per well) into each well of the assay plate. Include control wells for background (medium only). 2. Pre-incubation: Allow cells to adhere and recover for 4-24 hours in a 37°C, 5% CO₂ incubator. 3. Compound Addition: Prepare a serial dilution of the therapeutic agent (typically a 1:3 or 1:2 dilution series across 8-10 concentrations). Add 10 µL of each dilution to the assay wells, ensuring the final concentration spans a range from below to above the expected IC₅₀. Include a vehicle control (0% inhibition) and a control for 100% inhibition (e.g., a potent, non-specific cytotoxic agent). 4. Incubation: Incubate the plate for the desired treatment duration (e.g., 72 hours). 5. Viability Measurement: Equilibrate the plate to room temperature. Add a volume of CellTiter-Glo reagent equal to the volume of medium in each well. Shake the plate to induce cell lysis, then incubate for 10 minutes to stabilize the luminescent signal. Record the luminescence using the plate reader.

4. Data Analysis: 1. Calculate the average luminescence for replicates at each concentration. 2. Normalize the data: % Inhibition = 100 × [1 - (Luminescencesample - Luminescence100%inhibition) / (Luminescencevehiclecontrol - Luminescence100%inhibition)]. 3. Fit the normalized data to a 4-parameter logistic (4PL) nonlinear regression model: ( Y = Bottom + \frac{(Top - Bottom)}{(1 + 10^{((LogIC{50} - X) × HillSlope)})} ) where Y is the % inhibition and X is the logâ‚â‚€ of the compound concentration. 4. The ICâ‚…â‚€ is the concentration (X) at which Y = 50.

5. Key Considerations for Model Integration:

- Use a minimum of 8-10 concentration points with at least three biological replicates each [4].

- Ensure the curve has well-defined top (maximum inhibition) and bottom (minimum inhibition) plateaus.

- The final ICâ‚…â‚€ value should be reported with its confidence interval from the curve fit. This parameter can be directly incorporated into differential equation models of tumor cell kill in response to drug concentration [2] [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Mathematical Oncology Research

| Research Reagent / Material | Function and Application |

|---|---|

| Patient-Derived Cell Lines | Provides a physiologically relevant in vitro model system for quantifying drug response parameters (e.g., ICâ‚…â‚€) and validating model predictions [4]. |

| Cell Viability Assays (e.g., CellTiter-Glo) | Measures ATP levels as a proxy for the number of viable cells, generating the primary data for dose-response curves and model calibration [4]. |

| High-Throughput Screening (HTS) Platforms | Enables rapid testing of numerous drug compounds and concentrations across multiple cell models, generating large-scale data for model parameterization [4]. |

| Clinical Imaging Data (MRI, CT) | Provides in vivo spatial and temporal data on tumor size and morphology for initializing and validating spatial models (e.g., reaction-diffusion models for GBM) [3]. |

| Image Analysis Software (e.g., 3D Slicer) | Used to manually or semi-automatically segment clinical images, defining regions of interest (e.g., enhancing tumor, edema) that serve as initial conditions for spatial models [3]. |

| Iodol | Iodol, CAS:87-58-1, MF:C4HI4N, MW:570.68 g/mol |

| Retra | Retra, CAS:1173023-52-3, MF:C11H12ClNO3S2, MW:305.8 g/mol |

Integrated Workflow for Treatment Optimization

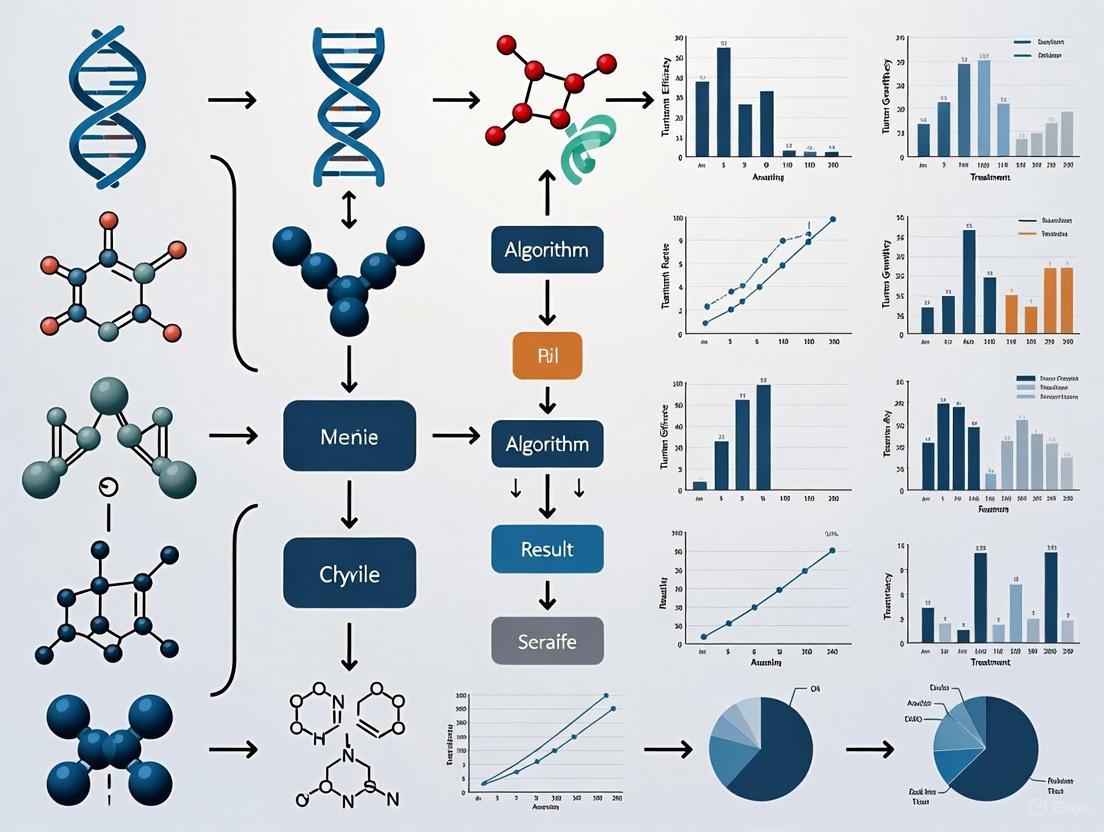

The full potential of mathematical oncology is realized when modeling is integrated into a cohesive workflow that connects basic research with clinical application. The following diagram and description outline this iterative process.

Diagram 2: Treatment Optimization Workflow

1. Data Acquisition: The workflow begins with the collection of high-quality data from various sources. This includes clinical data (e.g., imaging, treatment history), genomic data, and preclinical data from in vitro or in vivo models, such as dose-response curves [3] [4]. This data provides the foundation for building and calibrating models.

2. Model Construction & Calibration: A mechanistic mathematical model is selected and constructed based on the biological question. The model is then calibrated using the acquired data, a process that involves adjusting model parameters so that the model output closely matches the observed experimental or clinical data [1] [2]. This creates a "virtual patient" or "digital twin" representation.

3. Generate Predictions & Scenarios: The calibrated model is used in silico to simulate different treatment scenarios. This can involve testing various dosing schedules, drug combinations, or treatment sequences to identify strategies that maximize tumor control while minimizing toxicity or the emergence of resistance [1] [2].

4. Clinical Decision & Intervention: The model-derived treatment recommendations inform clinical decision-making. This could involve selecting a personalized therapy for an individual patient or designing a clinical trial for a specific patient population [1]. The chosen intervention is then administered.

5. Outcome Validation & Model Refinement: Patient outcomes are meticulously tracked. These real-world results are used to validate the model's predictions. Discrepancies between predicted and observed outcomes provide valuable information that is fed back into the workflow to refine and improve the model, creating a continuous cycle of learning and optimization [1] [3]. This integrated, iterative process is key to advancing personalized cancer therapy.

This document provides application notes and detailed protocols for researchers investigating the core biological processes of cancer, with a specific focus on informing the development of mathematical models for treatment optimization. A deep understanding of tumor growth dynamics, angiogenesis, and the tumor microenvironment (TME) is paramount for building in silico frameworks that can accurately simulate cancer progression and predict therapeutic efficacy [1] [2]. This guide synthesizes current knowledge on these processes, presents quantitative data for model parameterization, and outlines experimental methodologies for validating key model components.

Quantitative Data on Tumor Angiogenesis

Key Signaling Pathways in Tumor Angiogenesis

The process of angiogenesis is regulated by a complex interplay of multiple growth factors and their associated signaling pathways. The quantitative dynamics of these pathways are critical inputs for mechanistic mathematical models.

Table 1: Key Pro-Angiogenic Signaling Pathways and Their Functions.

| Signaling Pathway | Key Ligands/Receptors | Primary Cellular Functions | Selected Downstream Effectors |

|---|---|---|---|

| VEGF/VEGFR [5] [6] | VEGFA, VEGFR2 | Endothelial cell proliferation, migration, survival; Vascular permeability | PLCγ-PKC-MEK-ERK; PI3K-Akt; Src-FAK [6] |

| FGF/FGFR [5] [6] | FGF2 (bFGF), FGFR | EC proliferation and differentiation | Ras-Raf1-MAPK; PI3K-AKT; JAK-STAT [6] |

| PDGF/PDGFR [5] [6] | PDGFB, PDGFRβ | Pericyte recruitment; Vascular maturation | MAPK/ERK; PI3K/AKT; JNK [6] |

| ANG/Tie [6] | ANG1, ANG2, TIE2 | Vessel stabilization and maturation; Opposing roles in regulation | Akt/survivin pathway [6] |

Mechanisms of Tumor Vascularization

Tumors utilize a variety of mechanisms to secure a blood supply, extending beyond classical sprouting angiogenesis. These alternative mechanisms can pose significant challenges to anti-angiogenic therapies and must be accounted for in comprehensive models.

Table 2: Mechanisms of Tumor Vascularization and Their Characteristics.

| Mechanism | Description | Key Molecular Mediators | Implication for Therapy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sprouting Angiogenesis [5] | New vessels sprout from pre-existing ones via endothelial tip cell migration. | VEGF, Notch signaling [5] | Primary target of anti-VEGF therapies. |

| Intussusceptive Angiogenesis [5] [6] | Existing vessels split into two by the insertion of tissue pillars. | VEGF (induced) [5] | A rapid, efficient process; mechanisms less understood. |

| Vasculogenesis [5] | Recruitment and in situ differentiation of endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs). | VEGFA, SDF-1 [5] | Contributes to neovascularization; potential cellular target. |

| Vascular Mimicry (VM) [5] [6] | Tumor cells form fluid-conducting, vessel-like channels. | Hypoxia, EMT factors [5] | Not attached to ECs; associated with drug resistance. |

| Vessel Co-option [5] [6] | Tumor cells migrate along and hijack pre-existing vessels. | Not specified in search results | Mechanism of resistance to anti-angiogenic therapy. |

Diagram 1: The Cyclic Drive of Tumor Angiogenesis.

Experimental Protocols for Key Analyses

Protocol: In Vitro Analysis of Endothelial Cell Sprouting Angiogenesis

This protocol details the use of a 3D fibrin gel bead assay to quantitatively assess the sprouting and tube-forming capacity of endothelial cells in response to pro-angiogenic factors or their inhibition.

1.0 Application Note: This assay is a cornerstone for validating the core logic of agent-based models (ABMs) that simulate tip cell selection, stalk cell proliferation, and sprout extension [2] [7]. It provides high-content, quantifiable data on sprout number, length, and branching complexity.

2.0 Materials

- Research Reagent Solutions:

- Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVECs): Primary cells for studying endothelial biology.

- Cytodex Microcarrier Beads: Serve as a 3D scaffold for endothelial cell attachment and sprout initiation.

- Fibrinogen and Thrombin: To form the 3D fibrin gel matrix.

- VEGF and bFGF: Key pro-angiogenic growth factors to stimulate sprouting.

- Fibroblast Growth Medium: Conditioned medium from fibroblasts provides a source of additional angiogenic factors.

3.0 Procedure

- Cell Seeding on Beads: Culture HUVECs with Cytodex beads for 4-6 hours, allowing cells to adhere to the bead surface.

- Gel Polymerization: Transfer the cell-coated beads into a solution of fibrinogen and thrombin in a culture well. Incubate at 37°C to form a solid 3D fibrin gel.

- Application of Stimuli: Overlay the polymerized gel with endothelial growth medium supplemented with VEGF (50 ng/mL), bFGF (50 ng/mL), and 25% fibroblast-conditioned medium.

- Inhibitor Testing (Optional): To test anti-angiogenic compounds, include them in the overlay medium at desired concentrations.

- Incubation and Imaging: Culture the assay for 5-7 days, refreshing the medium every other day. Image sprouts daily using an inverted phase-contrast microscope.

- Quantitative Analysis: Use image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ) to quantify total sprout length, number of sprouts per bead, and number of branch points.

Protocol: In Vivo Validation of Anti-Angiogenic Therapy and Vascular Normalization

This protocol describes a pre-clinical murine model to evaluate the efficacy of anti-angiogenic therapy and its downstream effects on tumor growth and the immune microenvironment, crucial for calibrating hybrid mathematical models [7].

1.0 Application Note: Data from this protocol is essential for parameterizing models that link vascular normalization to improved perfusion, drug delivery, and immune cell infiltration [7]. It helps define the "normalization window," a critical time-dependent variable for combination therapy scheduling.

2.0 Materials

- Research Reagent Solutions:

- Syngeneic Cancer Cell Line: (e.g., murine glioma GL261 for orthotopic models, or MC38 for subcutaneous models).

- Anti-VEGF Monoclonal Antibody: (e.g., B20-4.1.1 for murine models). The key therapeutic agent.

- Isolectin or Anti-CD31 Antibody: For fluorescent staining of perfused and total vessels, respectively.

- Flow Cytometry Antibody Panel: For immune profiling (e.g., anti-CD45, CD3, CD8, CD4, F4/80).

3.0 Procedure

- Tumor Implantation: Implant cancer cells subcutaneously or orthotopically into immunocompetent mice.

- Treatment Initiation: Randomize mice into control and treatment groups once tumors reach a palpable size (~50 mm³). Administer anti-VEGF therapy (e.g., 5 mg/kg, i.p., twice weekly) or an isotype control.

- Tumor Growth Monitoring: Measure tumor dimensions 2-3 times per week using calipers. Calculate tumor volume using the formula: V = (length × width²) / 2.

- Tissue Harvest: Euthanize cohorts of mice at predetermined timepoints (e.g., day 3, 7, and 14 of treatment).

- Perfusion and Vessel Analysis: Inject fluorescently-labeled lectin intravenously 10 minutes before sacrifice to label perfused vessels. Excise tumors, section, and stain with an antibody against CD31 (pan-endothelial marker). Use confocal microscopy to quantify:

- Total Vessel Density: (CD31+ area).

- Perfused Vessel Fraction: (Lectin+ area / CD31+ area).

- Vessel Normalization Index: A composite metric including perfusion, pericyte coverage (via α-SMA staining), and basement membrane thickness.

- Immune Cell Infiltration Analysis: Digest a portion of the tumor to create a single-cell suspension. Stain with the antibody panel and analyze by flow cytometry to quantify the infiltration of CD8+ T cells, Tregs, and TAMs.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Studying Tumor Angiogenesis and Microenvironment.

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant Growth Factors | Stimulate angiogenesis in in vitro assays; used to create pro-angiogenic conditions. | VEGF-A, FGF2 (bFGF), PDGF-BB [5] [6] |

| Neutralizing Antibodies | Inhibit specific signaling pathways to validate their role in angiogenesis; used for in vitro and in vivo therapy. | Anti-VEGF (Bevacizumab), Anti-VEGFR2 [5] [8] |

| Small Molecule Inhibitors | Oral tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) that block intracellular signaling of pro-angiogenic receptors. | Sorafenib, Lenvatinib, Vorolanib (multi-targeted) [5] |

| Endothelial Cell Markers | Identify and quantify blood vessels in tissue sections (IHC/IF) or isolate ECs (FACS). | CD31 (PECAM-1), VE-cadherin, VEGFR2 [6] |

| Immune Cell Markers | Profile the immune contexture of the TME via flow cytometry or IHC. | CD45 (pan-immune), CD3 (T cells), CD8 (cytotoxic T), CD68/CD206 (TAMs), FoxP3 (Tregs) [8] |

| WSP-1 | WSP-1, MF:C33H21NO6S2, MW:591.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| DAz-1 | DAz-1, MF:C10H14N4O3, MW:238.24 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Mathematical Modeling Workflow Integration

The biological data and experimental outputs generated using the above protocols are directly integrated into mathematical modeling workflows for cancer treatment optimization. The following diagram illustrates this iterative, interdisciplinary process.

Diagram 2: Integrating Biology and Mathematical Modeling.

This integrated approach allows for the exploration of complex treatment strategies that would be prohibitively time-consuming or expensive to test empirically. Models can simulate the effects of various anti-angiogenic agents (e.g., VEGF inhibitors [5]), their scheduling (e.g., metronomic vs. MTD [9]), and their combination with other modalities like immunotherapy [7] [8] or chemotherapy across virtual patient cohorts [10]. The predictions generated, such as the existence of a vascular "normalization window" [7], can then be prospectively tested in the lab, creating a powerful feedback loop for therapeutic discovery.

The relentless and uncontrolled proliferation of cancer cells is a defining hallmark of the disease, driven by complex dynamic processes that operate across multiple biological scales. Mathematical modeling provides a powerful, quantitative framework to capture these dynamics, transforming a qualitative understanding of cancer into a predictive science. The journey from simple exponential growth models to more biologically realistic, saturating growth laws like the Gompertz model represents a cornerstone in mathematical oncology. These models do not merely describe data; they encode fundamental principles of tumor biology, such as competition for space and nutrients, the carrying capacity of the microenvironment, and the deceleration of growth as tumors enlarge. This Application Note details the practical implementation of these models, with a focus on the Gompertz framework, to study tumor growth kinetics. The protocols herein are designed to be integrated into a broader workflow for optimizing cancer treatment research, enabling scientists to calibrate models to experimental and clinical data for improved therapeutic strategy design.

Theoretical Foundations: From Exponential to Gompertz Growth

The evolution of tumor growth modeling reflects an increasing appreciation for the complex constraints of the in vivo environment. The table below summarizes the defining characteristics, equations, and limitations of three foundational models.

Table 1: Foundational Mathematical Models of Tumor Growth

| Model Name | Core Principle | Differential Equation | Integrated Solution | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exponential [11] | Constant, unbounded growth rate; all cells proliferate. | dN/dt = r · N |

N(t) = N₀ · e^(r·t) |

Unrealistic for large tumors; predicts infinite growth. |

| Logistic [11] | Density-dependent growth slowdown; linear decay of growth rate. | dN/dt = r · N · (1 - N/K) |

N(t) = (K · N₀) / (N₀ + (K - N₀)·e^(-r·t)) |

Inflection point is fixed at 50% of carrying capacity (K). |

| Gompertz [12] [13] [11] | Time-dependent exponential decay of growth rate; asymmetric sigmoid shape. | dN/dt = α · N · ln(K / N) |

N(t) = K · exp[ ln(N₀/K) · exp(-α·t) ] |

Proliferation rate is unbounded for very small populations. |

The Gompertz model has proven particularly effective in describing experimental and clinical tumor growth data. Its superiority stems from its ability to capture the rapid initial growth followed by a gradual slowdown and plateau as the tumor approaches a theoretical maximum size, or carrying capacity (K) [12] [14]. This decelerating pattern is consistent with the concept of spatial and nutrient constraints within the tumor microenvironment. The inflection point of the Gompertz curve, where growth is fastest, occurs when the tumor size is at 37% of K, providing more flexibility than the logistic model [13].

Experimental Protocols for Model Calibration

A critical step in utilizing these models is calibrating them to observed data. The following protocol outlines a standardized workflow for obtaining model parameters from longitudinal tumor volume measurements.

Protocol: Fitting Tumor Growth Models to Volumetric Data

Objective: To determine the best-fit parameters (e.g., growth rate α, carrying capacity K) for exponential, logistic, and Gompertz models based on a time-series of tumor volume measurements.

Materials and Reagents:

- In vivo tumor model (e.g., murine model with subcutaneous xenografts)

- Calipers or in vivo imaging system (e.g., MRI, CT)

- Software for nonlinear regression (e.g., R, Python with SciPy, MATLAB)

Procedure:

- Data Collection:

- Initiate tumors in your experimental model (e.g., via cell injection).

- Beginning from a baseline measurement, record tumor volumes at regular, frequent intervals (e.g., 2-3 times per week) over a timeframe sufficient to observe substantial growth and potential plateauing. A minimum of three time points is required, but more are strongly recommended for reliable fitting [12].

- Calculate tumor volume (V) using the formula for an ellipsoid: ( V = \frac{4}{3}π · (\frac{L}{2}) · (\frac{W}{2}) · (\frac{H}{2}) ), where L, W, and H are the three perpendicular diameters [15].

Data Preprocessing:

- Define the smallest detectable difference in volume (e.g., a 10% change) to account for measurement noise [12].

- Format data as a table with columns:

Time (t),Observed Volume (V_obs).

Model Fitting via Nonlinear Regression:

- Using your chosen software, employ a nonlinear least-squares regression algorithm to fit the integrated form of each growth model to the

(t, V_obs)data. - For the Gompertz model, fit the equation: ( V(t) = K · \exp\left( \ln(V_0/K) · \exp(-α·t) \right) ), where

V_0(initial volume),K(carrying capacity), andα(growth rate) are the parameters to be estimated. - Provide reasonable initial guesses for the parameters to ensure algorithm convergence.

- Using your chosen software, employ a nonlinear least-squares regression algorithm to fit the integrated form of each growth model to the

Model Selection and Validation:

- Calculate goodness-of-fit statistics for each model, including the coefficient of determination (R²) and the root-mean-squared error (RMSE) [12].

- Use statistical tests like the Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA with post-hoc tests to determine if there are significant differences in the goodness of fit between the models [12].

- Visually inspect the fitted curves overlaid on the raw data. The model that provides a high R², low RMSE, and a biologically plausible growth curve should be selected.

Troubleshooting Tip: If the Gompertz model fails to converge, try fitting the simpler logistic and exponential models first and use their parameters to inform initial guesses for the Gompertz fit (e.g., K from logistic, initial growth rate from exponential).

Advanced Application: The Reduced Gompertz Model and Bayesian Calibration

For cases with limited data points, a simplified "Reduced Gompertz" model can be employed, which leverages a known strong correlation between the parameters α and K [15] [14]. This correlation allows the two-parameter model to be reduced to a single individual parameter, drastically improving predictive power when data is scarce.

Objective: To estimate the time of tumor initiation (tâ‚€) from a limited number of late-stage tumor volume measurements.

Procedure:

- Establish a Population Prior: Using a historical dataset of fully observed tumor growth curves from the same cancer type and model system, fit the full Gompertz model and quantify the correlation between parameters α and K. Use this to derive the population-level parameter for the reduced model [14].

- Incorporate Sparse Individual Data: For a new subject, collect 2-3 tumor volume measurements.

- Bayesian Inference: Use Bayesian statistical methods (e.g., Markov Chain Monte Carlo) to compute the posterior distribution for the individual's growth parameter and the unobserved time of origin (tâ‚€), using the population parameter as a prior [14].

- Prediction: The posterior distribution provides an estimate for the tumor's initiation time, along with a credible interval quantifying the uncertainty of the prediction.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Tumor Growth Modeling

| Reagent / Resource | Function in Experimental Workflow | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cancer Cell Lines | Provides a genetically defined population for in vivo growth studies. | Human LM2-4LUC+ breast carcinoma cells [15]; Murine Lewis Lung Carcinoma (LLC) cells [14]. |

| Immunodeficient Mice | Host for xenograft studies using human cell lines. | SCID mice; allows engraftment and growth of human tumors [15]. |

| In Vivo Imaging System | Non-invasive, precise longitudinal measurement of tumor volume. | MRI, CT, or fluorescence imaging (e.g., IVIS); superior accuracy to calipers for deep or irregular tumors [12] [16]. |

| Digital Caliper | Standard tool for measuring subcutaneous tumor dimensions. | Used with the ellipsoid volume formula; cost-effective but less accurate for non-palpable tumors [15]. |

| Mathematical Software | Platform for performing nonlinear regression and model fitting. | Python (SciPy, NumPy), R, MATLAB; essential for parameter estimation and simulation [14]. |

Application in Treatment Optimization Workflow

Mathematical growth models are not merely descriptive; they are foundational for designing and optimizing cancer therapies. The Gompertz model, for instance, directly informed the Norton-Simon hypothesis, which posits that chemotherapy-induced tumor regression is proportional to the rate of tumor growth [9]. This principle led to the clinical development of dose-dense chemotherapy, where the same total dose is administered more frequently, thereby minimizing tumor regrowth between cycles and improving outcomes in cancers like breast cancer [9].

Furthermore, these models are integrated into larger therapeutic optimization frameworks. For example, the Gompertz differential equation can be coupled with terms representing drug effect to simulate and predict treatment response. This allows for in silico testing of different treatment schedules, such as adaptive therapy, which aims to maintain a stable tumor population by strategically cycling therapy to exploit competition between drug-sensitive and resistant cells [9] [2]. The diagram below illustrates how a foundational growth model integrates into a comprehensive treatment optimization workflow.

Therapeutic resistance represents a fundamental challenge in oncology, directly contributing to treatment failure, disease relapse, and poor patient outcomes. Current estimates indicate that approximately 90% of chemotherapy failures and more than 50% of failures in targeted therapy or immunotherapy are directly attributable to drug resistance [17]. This resistance manifests as either intrinsic (primary) resistance, where mechanisms pre-exist before treatment begins, or acquired (secondary) resistance, which develops during or after therapy [17]. The remarkable phenotypic plasticity of tumor cells enables continuous adaptation under therapeutic pressure, leading to the selection and enrichment of resistant subpopulations that often exhibit dormancy and stem cell-like properties [17].

The limitations of the traditional Maximum Tolerated Dose (MTD) paradigm are increasingly evident. Developed during the era of cytotoxic drugs, this approach often leads to disease relapse due to the emergence of drug resistance, particularly as newer therapeutics like targeted therapies and immunotherapies have different modes of action where dose efficacy can saturate, resulting in additional toxicity without significant efficacy gains [1]. Mathematical oncology has emerged as a critical discipline for addressing these challenges through mechanistic models that capture the spatial and temporal dynamics of tumor response to treatment [1].

Molecular Mechanisms of Treatment Resistance

Genetic and Epigenetic Drivers of Resistance

Tumor cells evade therapeutic killing through multiple interconnected biological pathways. Key mechanisms include activating drug efflux pumps, inducing target mutations, and activating alternative signaling pathways [17]. The influence of the microbiome has also emerged as a significant determinant of therapeutic response through immune modulation and metabolic cross-talk [17].

Table 1: Key Molecular Mechanisms of Cancer Treatment Resistance

| Resistance Category | Specific Mechanisms | Exemplary Clinical Manifestations |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Alterations | - Target gene mutations (e.g., T790M, C797S in EGFR)- Activation of bypass signaling pathways- Gene amplification | - Resistance to EGFR-TKIs in NSCLC [17] |

| Epigenetic Reprogramming | - DNA methylation changes- Histone modifications- Chromatin remodeling | - Altered gene expression profiles supporting survival [17] |

| Post-Translational Modifications | - Phosphorylation/dephosphorylation- Ubiquitination- Protein acetylation | - Modulation of protein activity and stability [17] |

| Non-Coding RNA Networks | - miRNA, siRNA, lncRNA regulatory circuits- Competing endogenous RNA networks | - Fine-tuning of resistance phenotypes [17] |

| Metabolic Reprogramming | - Altered energy metabolism- Nutrient scavenging pathways- Metabolic cross-talk with microenvironment | - Adaptation to metabolic stress induced by therapy [17] |

Microenvironment-Mediated Resistance

The tumor microenvironment plays a pivotal role in fostering resistance through multiple mechanisms. In pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), the acellular matrix can constitute up to 90% of tumor volume, creating extensive fibrosis that elevates interstitial fluid pressure, impairs vascularization, and creates a physical barrier to drug delivery [17]. This significantly limits the penetration of agents like gemcitabine and is associated with poor prognosis [17]. Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) are key drivers of this fibrotic microenvironment [17].

In glioblastoma, vascular abnormalities may disrupt the blood-brain barrier (BBB) unevenly, while overexpression of efflux pumps further reduces drug concentrations, diminishing therapeutic efficacy [17]. Hematological malignancies, while not impeded by physical barriers, depend on specialized mechanisms such as stem cell dormancy and bone marrow niche dynamics, as evidenced in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) and multiple myeloma (MM) [17].

Mathematical Modeling Frameworks for Resistance Dynamics

Foundational Modeling Approaches

Mathematical models in oncology use equations to represent underlying biological processes rather than just inputs and outputs, capturing quantities of interest over time such as tumor size dynamics or drug concentrations [1]. These models can incorporate treatment dynamics, including dose-response of systemic drugs or radiotherapy, and eco-evolutionary principles such as ecological interactions of cell-based immunotherapies or evolutionary dynamics due to the emergence of resistance [1].

A general treatment-agnostic formulation for tumor volume dynamics uses ordinary differential equations such as:

$$\frac{dN}{dt}=rN\left(1-\frac{N}{K}\right)-N\sum{i = 1}^{n}{\alpha}{i}{e}^{-\beta(t-{\tau}{i})}H(t-{\tau}{i})$$

where N(t) is the tumor volume at time t, r represents the proliferation rate, K is the carrying capacity, αi represents the death rate due to the ith treatment dose, τi is the time of administration, β is the decay rate of treatment effect, and H(t - τi) is the Heaviside step function [18].

Clinical Translation and Trial Applications

Recent clinical trials demonstrate the translation of mathematical models into therapeutic strategies, particularly those moving beyond the MTD paradigm.

Table 2: Model-Informed Clinical Trials in Oncology (Adapted from [1])

| Model Type | Trial ID/Name | Cancer Type | Intervention | Status/Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Evolution-based: Adaptive Therapy | NCT02415621 | Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer | Adaptive Abiraterone Therapy | Active, not recruiting |

| Evolution-based: Adaptive Therapy | NCT03543969 | Advanced BRAF Mutant Melanoma | Adaptive BRAF-MEK Inhibitor Therapy | Active, not recruiting |

| Evolution-based: Adaptive Therapy | NCT05080556 (ACTOv) | Ovarian Cancer | Adaptive Chemotherapy | Recruiting (Phase 2) |

| Evolution-based: Extinction Therapy | NCT04388839 | Rhabdomyosarcoma | Evolutionary Therapy | Recruiting (Phase 2) |

| Fully Personalized Treatment | NCT04343365 (ETB) | Multiple Cancers | Evolutionary Tumor Board | Recruiting (Observational) |

| Dynamics-based Radiotherapy | NCT03557372 | Glioblastoma | Mathematical Model-Adapted Radiation | Feasibility and Safety ✓ |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Parameter Estimation Workflow for Tumor Dynamic Models

Protocol Objective: To establish a hierarchical framework for simulating and predicting pancreatic tumor response to combination treatment regimens involving chemotherapy (NGC regimen: mNab-paclitaxel, gemcitabine, cisplatin), stromal-targeting drugs (calcipotriol, losartan), and immunotherapy (anti-PD-L1) [18].

Materials and Equipment:

- Genetically engineered mouse model of pancreatic cancer (KrasLSL-G12D; Trp53LSL-R172H; Pdx1-Cre)

- Calipers or imaging system for tumor volume measurement

- Therapeutic agents: chemotherapeutics, stromal-targeting drugs, immunotherapies

- Computational resources for Bayesian parameter estimation

Procedure:

- Experimental Data Collection: Obtain longitudinal tumor volume measurements over a 14-day period with at least three measurement time points [18].

- Control Group Parameter Estimation:

- Employ prior distributions for proliferation rate (r), carrying capacity (K), and initial condition (Nâ‚€) based on prior predictive checks

- Estimate population-specific K and mouse-specific r and Nâ‚€ using Bayesian methods

- Validate model fit using concordance correlation coefficient (CCC) and mean absolute percent error (MAPE) [18]

- Treatment Model Parameter Estimation:

- Fix carrying capacity (K) to values obtained from control group analysis

- Estimate treatment-specific parameters (death rate α, decay rate β) for each mouse

- Compare Linear Treatment Model (β=0) versus Exponential Decay Treatment Model (estimated β) [18]

- Model Validation:

- Perform leave-one-out predictions to assess robustness

- Conduct mouse-specific predictions using individualized parameters

- Implement hybrid, group-informed, mouse-specific predictions [18]

Quality Control Metrics:

- Target concordance correlation coefficient (CCC) >0.70 for predictive accuracy [18]

- Calculate Pearson correlation coefficient (PCC) and mean absolute percent error (MAPE)

- Use coverage metrics to verify biological plausibility of parameter combinations [18]

Comparison of Methods Experiment for Biomarker Validation

Protocol Objective: To estimate systematic error or inaccuracy when comparing new analytical methods to reference methods for biomarker quantification [19].

Materials:

- Minimum 40 different patient specimens covering entire working range

- Reference method or well-characterized comparative method

- Statistical analysis software (R, Python, or specialized packages)

Procedure:

- Sample Selection: Select 40+ patient specimens representing the spectrum of diseases expected in routine application, carefully selected based on observed concentrations to ensure a wide range of test results [19].

- Experimental Timeline: Conduct analyses over multiple runs with a minimum of 5 different days to minimize systematic errors that might occur in a single run [19].

- Sample Analysis: Analyze specimens within two hours of each other by test and comparative methods to prevent specimen degradation from impacting results [19].

- Data Analysis:

- Graph data using difference plots (test minus comparative results vs. comparative result)

- Visually inspect for outliers and systematic patterns

- Calculate linear regression statistics (slope, y-intercept, standard deviation about the line) for wide analytical ranges

- Compute average difference (bias) for narrow analytical ranges [19]

- Interpretation:

- Estimate systematic error at medically important decision concentrations

- Determine constant or proportional nature of error from regression parameters [19]

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Resistance Modeling Studies

| Reagent/Material | Specification/Example | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Genetically Engineered Mouse Models | KrasLSL-G12D; Trp53LSL-R172H; Pdx1-Cre (KPC) | Pancreatic cancer modeling with defined genetic drivers [18] |

| Chemotherapeutic Agents | NGC regimen: mNab-paclitaxel, gemcitabine, cisplatin | Standard chemotherapy combination for pancreatic cancer [18] |

| Stromal-Targeting Drugs | Calcipotriol (vitamin D analog), Losartan (angiotensin inhibitor) | Modify tumor microenvironment to enhance drug delivery [18] |

| Immunotherapeutic Agents | Anti-PD-L1 immune checkpoint inhibitors | Modulate immune response within tumor microenvironment [18] |

| Longitudinal Measurement Tools | Calipers, ultrasound, or molecular imaging systems | Tumor volume tracking for model parameter estimation [18] |

| Computational Resources | Bayesian estimation algorithms, ODE solvers | Parameter estimation and model simulation [18] |

Future Directions and Integrative Technologies

The field of mathematical oncology is increasingly leveraging advanced technologies to enhance predictive capabilities. Single-cell and spatial omics, liquid biopsy, and artificial intelligence are emerging as transformative tools for early detection and real-time prediction of resistance evolution [17]. Integration of mathematical models with 'virtual patient' frameworks, including 'digital twins', represents a promising approach for advancing mechanistic complexity and decision support capabilities [1].

The synthesis of novel therapeutic strategies that convert resistance mechanisms into therapeutic vulnerabilities represents a paradigm shift. These include synthetic lethality approaches, metabolic targeting, and disruption of stem cell and stromal niches [17]. By bridging mechanistic understanding with adaptive clinical design, these integrated approaches provide a roadmap for overcoming therapeutic resistance and achieving sustained, long-term cancer control.

Integrating Patient-Specific Data for Personalized Medicine Approaches

The paradigm of cancer treatment is shifting from a one-size-fits-all approach to highly personalized strategies that account for individual patient variability. This transformation is driven by the integration of diverse patient-specific data streams with advanced mathematical modeling techniques. By creating dynamic, computational representations of cancer progression and treatment response at individual patient levels, researchers and clinicians can now optimize therapeutic strategies while minimizing adverse effects. This protocol details methodological frameworks for constructing patient-specific cancer models, focusing on the integration of multi-scale data, mathematical formalization of treatment dynamics, and clinical translation of model-derived insights. We emphasize practical implementation through standardized workflows, computational tools, and validation approaches suitable for research and drug development applications.

The foundation of personalized cancer medicine lies in comprehensive data integration from multiple biological scales and temporal dimensions. Patient-specific modeling requires harmonization of diverse data types, including genomic profiles, longitudinal imaging, clinical parameters, and treatment history. Digital twin technology represents a cutting-edge framework for creating dynamic virtual representations of individual patients' cancer biology, enabling in silico testing of treatment strategies before clinical implementation [20] [21]. These computational constructs integrate real-time patient data with mechanistic biological knowledge to simulate disease progression and therapeutic response.

The mathematical oncology discipline provides the conceptual bridge between raw patient data and clinically actionable insights [1] [22]. By employing mechanistic models grounded in biological first principles, researchers can move beyond correlative associations to establish causal relationships within cancer systems. This approach captures the spatial and temporal dynamics of tumor growth, interaction with the microenvironment, and evolution of treatment resistance [1]. The workflow transforms heterogeneous patient data into calibrated mathematical models that can predict individual treatment outcomes and optimize therapeutic schedules.

Table 1: Data Types for Patient-Specific Modeling in Oncology

| Data Category | Specific Data Types | Role in Model Development |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical Parameters | Tumor size, histology, stage, performance status | Define initial conditions and clinical constraints |

| Imaging Data | CT, MRI, PET scans; radiomic features | Spatial characterization; treatment response assessment |

| Molecular Profiling | Genomic sequencing, transcriptomics, proteomics | Parameterize mechanistic models; identify therapeutic targets |

| Treatment History | Drug types, doses, schedules, toxicities | Inform model calibration; predict resistance mechanisms |

| Longitudinal Monitoring | Circulating tumor DNA, lab values, patient-reported outcomes | Enable model updating and validation over time |

Protocols for Patient-Specific Model Development

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing Protocol

Objective: Standardize the collection and processing of multi-source patient data for mathematical model development.

Materials and Equipment:

- Institutional review board approval

- Secure data storage infrastructure (HIPAA/GDPR compliant)

- Clinical data extraction tools (e.g., EHR APIs)

- Genomic sequencing platform

- Image processing software (e.g., 3D Slicer, ITK-SNAP)

- Data harmonization pipeline

Procedure:

Clinical Data Extraction

- Extract demographic information, cancer diagnosis, stage, histology, and prior treatment history from electronic health records

- Compile laboratory values including complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, and cancer biomarkers

- Document performance status (ECOG/Karnofsky) and comorbid conditions

Molecular Profiling

- Perform whole exome or targeted sequencing of tumor tissue and matched normal sample

- Conduct RNA sequencing for gene expression profiling

- Process using standardized bioinformatics pipelines for variant calling and expression quantification

Medical Image Processing

- Acquire DICOM images from relevant modalities (CT, MRI, PET)

- Perform manual or automated tumor segmentation to define regions of interest

- Extract radiomic features using standardized pyradiomics or similar packages

- Register serial images to assess temporal changes

Data Integration and Harmonization

- Establish common patient identifiers across all data sources

- Normalize continuous variables using z-score or min-max scaling

- Handle missing data through appropriate imputation methods

- Create structured data matrix for model input

Troubleshooting Tips:

- Inconsistent imaging protocols across timepoints may affect segmentation accuracy; employ intensity normalization techniques

- Sample quality issues in molecular profiling may require additional wet-lab validation

- Temporal misalignment between data types can be addressed through temporal interpolation

Mathematical Model Implementation Protocol

Objective: Implement mechanistic mathematical models that can be personalized using patient-specific data.

Materials and Equipment:

- Computational environment (Python, R, or MATLAB)

- Differential equation solvers (e.g., ODE45, SUNDIALS)

- High-performance computing resources for parameter estimation

- Bayesian inference tools (e.g., Stan, PyMC3)

- Model visualization libraries

Procedure:

Model Selection Framework

- For tumor growth dynamics: Implement Gompertz growth model:

dV/dt = rV × ln(K/V)where V is tumor volume, r is growth rate, and K is carrying capacity [2] - For drug pharmacokinetics: Implement one-compartment model:

dC/dt = -k × Cwhere C is drug concentration and k is elimination rate - For dose-response relationships: Implement Hill equation:

E = (Emax × C^n)/(EC50^n + C^n)where E is effect, Emax is maximum effect, C is concentration, EC50 is half-maximal effective concentration, and n is Hill coefficient [2] - For resistance evolution: Implement Lotka-Volterra competition models between sensitive and resistant populations [2]

- For tumor growth dynamics: Implement Gompertz growth model:

Parameter Estimation

- Define prior distributions for model parameters based on population studies

- Implement Bayesian calibration using Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods

- Incorporate hierarchical modeling to share information across patient subgroups

- Validate parameter identifiability using profile likelihood or similar approaches

Model Personalization

- Initialize model state variables using patient-specific baseline measurements

- Calibrate growth parameters using longitudinal tumor size measurements

- Estimate drug sensitivity parameters from prior treatment responses when available

- Incorporate genomic alterations as modifiers of specific model parameters

Model Validation

- Perform cross-validation using temporal hold-out of later timepoints

- Quantify prediction accuracy using concordance index, mean absolute error, or similar metrics

- Compare against null models or standard clinical prediction rules

- Establish clinical validity through correlation with observed outcomes

Troubleshooting Tips:

- Poor model identifiability may require simplification of model structure or incorporation of additional data types

- Computational bottlenecks in parameter estimation can be addressed through approximate Bayesian computation or surrogate modeling

- Discrepancies between predicted and observed outcomes may indicate missing biological mechanisms

Diagram 1: Workflow for developing personalized cancer treatment models

Mathematical Modeling Approaches

Formal Mathematical Foundations

Personalized cancer treatment models are built upon established mathematical formalisms that capture critical biological processes. The core framework integrates tumor growth dynamics, drug pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics (PK/PD), and evolutionary dynamics of resistance [2] [1].

Tumor Growth Dynamics:

The Gompertz model effectively captures the decelerating growth pattern observed in many clinical tumors:

dV/dt = rV × ln(K/V)

where V represents tumor volume, r is the intrinsic growth rate, and K is the carrying capacity representing environmental limitations [2]. This equation can be personalized by estimating r and K from longitudinal imaging data for individual patients.

Drug Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics:

A one-compartment model provides a simplified representation of drug distribution and elimination:

dC/dt = -k × C

where C is drug concentration and k is the elimination rate constant [2]. The relationship between drug concentration and effect is commonly modeled using the Hill equation:

E = (Emax × C^n)/(EC50^n + C^n)

where E is the treatment effect, Emax is the maximum possible effect, EC50 is the concentration producing half-maximal effect, and n determines the steepness of the response curve.

Evolutionary Dynamics of Resistance:

The emergence of treatment resistance can be modeled using competitive Lotka-Volterra equations:

dS/dt = rS × S × (1 - (S + αR)/K)

dR/dt = rR × R × (1 - (R + βS)/K)

where S and R represent sensitive and resistant cell populations, rS and rR their respective growth rates, and α and β quantify competitive interactions [2].

Digital Twin Implementation Framework

Digital twin technology creates virtual replicas of individual patients that update in real-time as new data becomes available [20] [21]. The implementation involves three core components:

- Physical Entity: The actual patient with their unique cancer biology and clinical characteristics

- Virtual Replica: The computational model personalized to the patient's data

- Data Connectivity: Bidirectional information flow between physical and virtual entities

Key enabling technologies for digital twins include:

- Internet of Things (IoT) for continuous data streaming from wearable sensors and medical devices

- Artificial intelligence and machine learning for pattern recognition and model optimization

- Cloud computing for scalable computational infrastructure

- Blockchain for secure data management and sharing [20]

Table 2: Mathematical Model Types in Personalized Oncology

| Model Category | Key Equations | Clinical Applications | Data Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor Growth Models | dV/dt = rV × ln(K/V) (Gompertz) | Predicting natural progression; sizing adjuvant therapy windows | Longitudinal tumor measurements (imaging) |

| Pharmacokinetic Models | dC/dt = -k × C (one-compartment) | Optimizing drug dosing and scheduling | Drug concentration measurements; physiological parameters |

| Dose-Response Models | E = (Emax × C^n)/(EC50^n + C^n) (Hill equation) | Personalizing drug selection and combination strategies | Pre- and post-treatment tumor response data |

| Evolutionary Dynamics Models | dS/dt = rS × S × (1 - (S + αR)/K) | Designing strategies to suppress resistance emergence | Repeat biopsies showing clonal composition changes |

Experimental Validation and Clinical Translation

Model Validation Protocol

Objective: Establish rigorous validation procedures to ensure model predictions are clinically reliable.

Materials and Equipment:

- Independent validation dataset (temporal or cohort-based)

- Statistical analysis software

- Clinical outcome data (response, progression, survival)

- Benchmarking against established clinical rules

Procedure:

Temporal Validation

- Reserve the most recent timepoints for validation after model calibration on earlier data

- Compare predicted vs. observed tumor trajectories using concordance correlation coefficient

- Assess prediction error growth over increasing time horizons

Cohort-Based Validation

- Apply models developed on one patient cohort to an independent cohort

- Evaluate discrimination performance using time-dependent ROC analysis

- Assess calibration using observed vs. expected outcome plots

Clinical Benchmarking

- Compare model predictions against standard response criteria (RECIST)

- Evaluate whether model-based recommendations would have improved actual outcomes

- Assess potential clinical utility using decision curve analysis

Sensitivity and Uncertainty Analysis

- Perform global sensitivity analysis to identify most influential parameters

- Quantify prediction uncertainty using Bayesian credible intervals

- Evaluate robustness to data perturbations and missingness

Troubleshooting Tips:

- Poor temporal validation performance may indicate overfitting or missing key biological mechanisms

- Systematic prediction errors across cohorts may reflect unaccounted population differences

- Excessive prediction uncertainty may require additional data collection to inform critical parameters

Clinical Implementation Protocol

Objective: Translate validated models into clinical decision support tools for treatment personalization.

Materials and Equipment:

- Regulatory-compliant software platform

- EHR integration capabilities

- Clinical decision support interface

- Model updating infrastructure

Procedure:

Treatment Optimization

- Define objective function balancing efficacy and toxicity

- Implement optimization algorithms to identify optimal drug schedules

- Incorporate clinical constraints (dose limitations, administration logistics)

- Generate personalized dosing recommendations

Clinical Decision Support

- Develop intuitive visualization of model predictions and uncertainties

- Present alternative scenarios with estimated outcomes

- Integrate with molecular tumor board workflows

- Document model assumptions and limitations

Adaptive Updating

- Establish protocols for model recalibration as new data arrives

- Implement trigger points for model review based on prediction discordance

- Create feedback mechanisms to improve population models from individual experiences

Outcome Tracking

- Monitor concordance between predicted and actual outcomes

- Document clinical decisions influenced by model predictions

- Assess impact on treatment response, toxicity, and survival endpoints

Troubleshooting Tips:

- Physician reluctance to adopt model-based recommendations may be addressed through education and interpretable visualizations

- Regulatory concerns can be mitigated through rigorous validation and clear description of intended use

- Computational burden in clinical settings may require development of simplified surrogate models

Diagram 2: Clinical translation pathway for personalized treatment optimization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for Personalized Cancer Modeling Research

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Data Generation Platforms | Whole exome sequencing (Illumina); RNA sequencing (10x Genomics); Mass cytometry (Fluidigm) | Generate molecular profiling data for model parameterization |

| Computational Environments | Python (SciPy, NumPy); R (deSolve, brms); MATLAB (SimBiology); Stan (probabilistic programming) | Implement and calibrate mathematical models |

| Clinical Data Management | EHR APIs (FHIR standards); REDCap; i2b2 tranSMART | Structured collection and integration of clinical parameters |

| Image Analysis Tools | 3D Slicer; ITK-SNAP; PyRadiomics; QuPath | Extract quantitative imaging features for spatial modeling |

| Model Personalization Algorithms | Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC); Approximate Bayesian Computation (ABC); Particle Filtering | Estimate patient-specific parameters from observed data |

| Validation Frameworks | Scikit-learn; survivalROC; rms (R Package); Model-specific metrics | Assess prediction accuracy and clinical utility |

| Digital Twin Platforms | DTwins (emerging standards); NVIDIA Clara; Custom architectures | Implement continuous patient-specific model updating |

| Namie | Namie (Ethanone Bridged JWH 070) | Namie is a synthetic research chemical for analytical and pharmacological study. This product is For Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Pti-1 | Pti-1, CAS:1400742-46-2, MF:C21H29N3S, MW:355.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The integration of patient-specific data with mathematical modeling frameworks represents a transformative approach to personalized cancer medicine. The protocols outlined provide a comprehensive roadmap for developing, validating, and implementing these models in both research and clinical settings. As digital twin technologies mature and multi-scale data becomes more accessible, these approaches will increasingly enable truly personalized treatment optimization [20] [21]. The field of mathematical oncology continues to develop more sophisticated models that capture the dynamic, evolutionary nature of cancer, moving beyond static genomic snapshots to embrace the temporal dynamics of treatment response and resistance emergence [1] [22]. Through continued refinement of these protocols and their application in clinical trials, we anticipate substantial advances in our ability to personalize cancer therapy for improved patient outcomes.

The Modeler's Toolkit: A Step-by-Step Guide from Concept to Clinical Application

The initial step in developing a mathematical model for cancer treatment optimization is the precise identification of a clinical oncology problem that can be addressed through computational approaches. This requires recognizing a significant challenge in current treatment paradigms where mathematical modeling can provide meaningful insights. A primary problem identified in contemporary oncology is the failure of the traditional Maximum Tolerated Dose (MTD) paradigm, which involves uniformly and continuously administering the highest possible dose that patients can tolerate. This approach often leads to treatment resistance and disease relapse because it fails to account for the dynamic, heterogeneous, and evolutionary nature of cancer, particularly in metastatic settings [1].

The limitations of the MTD approach are especially pronounced with newer therapeutic modalities such as targeted therapies and immunotherapies, where dose efficacy can saturate, resulting in increased toxicity without corresponding improvements in treatment outcomes [1]. Mathematical oncology addresses these limitations by providing a framework to move beyond static dosing regimens toward dynamic treatment strategies that can adapt to tumor evolution and patient-specific characteristics.

Key Problems in Cancer Treatment

Table 1: Primary Clinical Problems Addressable by Mathematical Modeling

| Problem Category | Specific Clinical Challenge | Consequence of Current Approaches |

|---|---|---|

| Treatment Resistance | Emergence of drug-resistant cell populations during therapy [2] | Treatment failure and disease progression [1] |

| Tumor Heterogeneity | Spatial and temporal variations in tumor cell composition [1] | Inconsistent treatment response across tumor sites |

| Dynamic Tumor Evolution | Cancer cell adaptation to selective pressures of treatment [2] | Limited long-term efficacy of therapeutic agents |

| Dosing Optimization | Saturation of dose efficacy with newer therapeutics [1] | Increased toxicity without therapeutic benefit |

| Personalization Gap | One-size-fits-all dosing regimens [2] | Suboptimal outcomes for individual patients |

| Etrumadenant | Etrumadenant, CAS:2239273-34-6, MF:C23H22N8O, MW:426.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| chd-5 | chd-5, CAS:289494-16-2, MF:C19H17N3O2, MW:319.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Framework for Biological System Simplification

Once a clinical problem is identified, the next critical step is to simplify the complex biological system into core components that can be mathematically represented. This process involves:

- Defining System Boundaries: Determining which biological elements are essential to include for addressing the specific problem

- Identifying Key Variables: Selecting the most critical factors that drive system dynamics

- Establishing Relationships: Defining how these variables interact through mathematical relationships

For example, when modeling treatment resistance, the complex biological reality of countless cellular interactions and molecular pathways must be reduced to essential components such as sensitive and resistant cell populations, their growth dynamics, and competitive interactions [2].

Table 2: Biological Complexity and Corresponding Simplifications for Mathematical Modeling

| Biological Complexity | Simplified Mathematical Representation | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Tumor-immune interactions | System of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) for immune and cancer cell populations [23] | Quantitative Cancer-Immunity Cycle (QCIC) model for mCRC [23] |

| Spatial tumor heterogeneity | Reaction-diffusion equations with diffusion coefficients [3] | Glioblastoma growth simulation using ASU-Barrow model [3] |

| Clonal evolution and competition | Lotka-Volterra competition models or evolutionary game theory [2] | Adaptive therapy for castration-resistant prostate cancer [1] |

| Drug pharmacokinetics | Compartmental models (e.g., one-compartment: dC/dt = -k×C) [2] | Optimization of chemotherapeutic dosing schedules [2] |

| Multi-scale processes | Multi-compartment models (e.g., lymph node, blood, tumor microenvironment) [23] | Prediction of metastatic colorectal cancer progression [23] |

Experimental Protocols for Initial Data Collection

Protocol 1: Tumor Growth Dynamics Parameterization

Purpose: To quantify baseline tumor growth kinetics for model initialization.

Materials:

- Longitudinal medical imaging data (MRI, CT, or PET)

- Image analysis software (e.g., 3D-Slicer [3])

- Tumor segmentation tools

- Computational environment for parameter estimation

Methodology:

- Image Acquisition and Preprocessing: Collect serial imaging studies from patient cohorts. For glioblastoma modeling, this includes T1 post-contrast and T2/FLAIR MRI sequences acquired at typical clinical intervals (e.g., 2-3 months) [3].

- Tumor Segmentation: Manually or automatically delineate tumor boundaries across all imaging time points. For GBMs, segment enhancing tumor, necrotic core, and edema regions [3].

- Volume Calculation: Compute tumor volumes from segmented regions across all time points.

- Growth Curve Fitting: Fit appropriate mathematical models (e.g., exponential, Gompertz, logistic) to the longitudinal volume data to estimate growth parameters.

- Parameter Estimation: Use statistical methods (e.g., maximum likelihood estimation, Bayesian inference) to derive patient-specific growth parameters.

Data Analysis:

- Calculate growth rates (r) and carrying capacities (K) for population growth models

- Estimate diffusion coefficients (D) for spatial models using invasion patterns

- Quantify inter-patient variability in growth parameters

Protocol 2: Treatment Response Assessment for Model Calibration

Purpose: To quantify tumor response to various treatment modalities for model calibration.

Materials:

- Clinical trial data or retrospective patient cohorts with treatment records

- Standardized response criteria (e.g., RECIST criteria)

- Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic assay capabilities

Methodology:

- Treatment Documentation: Record precise drug regimens, including dosing schedules, amounts, and durations.

- Response Monitoring: Document tumor size changes following treatment initiation using the same imaging modalities and segmentation approaches as in Protocol 1.

- Resistance Identification: Note emergence of resistance through regrowth during continued treatment.

- PK/PD Data Collection: Where available, collect drug concentration data over time and correlate with tumor response.

Data Analysis:

- Fit dose-response relationships using Hill equations: ( E = \frac{E{max} \times C^n}{EC{50}^n + C^n} ) where ( E ) is effect, ( E{max} ) is maximum effect, ( C ) is drug concentration, ( EC{50} ) is half-maximal effective concentration, and ( n ) is the Hill coefficient [2]

- Estimate resistant cell fractions from regrowth kinetics

- Calculate response rates and progression-free survival

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Mathematical Oncology

| Resource Category | Specific Tool/Reagent | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Tools | Ordinary Differential Equation (ODE) solvers | Simulating population dynamics of tumor and immune cells [2] [23] |

| Image Analysis Software | 3D-Slicer platform [3] | Manual segmentation of tumor regions from medical images |

| Data Processing Tools | SPM-12 [3] | Co-registration of serial MRI scans and brain domain segmentation |

| Parameter Estimation | Maximum likelihood methods; Bayesian inference [23] | Calibrating model parameters to individual patient data |

| Clinical Data Sources | Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program [24] | Access to population-based cancer incidence and survival data |

| Model Validation Frameworks | Digital twin methodologies [1] | Creating virtual patient representations for testing treatment strategies |

Workflow Visualization

Figure 1: Workflow for Problem Identification and Biological System Simplification in Mathematical Oncology

Multi-Compartment Modeling Framework

Figure 2: Multi-Compartment Framework for Quantitative Cancer-Immunity Cycle Modeling

Defining model components is a critical step in constructing a predictive mathematical model for cancer treatment optimization. This process involves formally specifying the biological entities, their properties, and their interactions through a structured framework of compartments, variables, and parameters. In translational cancer research, these components quantitatively represent tumor biology, drug pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics (PK/PD), and the emergence of treatment resistance [2] [1]. A well-defined model serves as a formal hypothesis about the cancer system, enabling researchers and drug development professionals to simulate treatment scenarios, predict patient-specific outcomes, and optimize therapeutic strategies beyond the maximum tolerated dose paradigm [1]. This document outlines a standardized protocol for defining these core elements, framed within a broader modeling workflow.

Core Definitions and Theoretical Framework

Fundamental Component Types

Mathematical models in oncology abstract a complex, dynamic biological system into a set of interrelated mathematical constructs.

- Compartments: These represent distinct biological populations or spatial domains. A compartment is typically modeled as a container whose size changes over time. Examples include populations of sensitive cancer cells, resistant cancer cells, immune effector cells like CAR-T cells, or nutrient concentrations in the tumor microenvironment [2] [25].

- Variables (State Variables): These are time-dependent quantities that describe the state of the system. The primary state variables are often the sizes of the compartments (e.g., tumor volume, CAR-T cell count). Their evolution over time is what the model seeks to describe through differential equations [2].

- Parameters: These are constants that define the properties and interaction rules of the system. Parameters are not time-dependent and must be estimated from experimental or clinical data. Examples include the maximal growth rate of a tumor, the carrying capacity of the environment, or the killing efficacy of a drug [2] [1].

Relationship to Model Equations

The components are integrated via mathematical equations, most commonly ordinary differential equations (ODEs). The general form for a compartment model is:

d(Compartment)/dt = Inflows - Outflows

The inflows and outflows are functions of the current state variables, the model parameters, and any external forcing functions like treatment dosage [2].

Structured Classification of Model Components

The following tables provide a standardized classification of common compartments, variables, and parameters used in mathematical models of cancer treatment, synthesizing information from multiple modeling paradigms [2] [1] [25].

Table 1: Common Compartments and State Variables in Cancer Treatment Models

| Component Name | Symbol | Type | Biological/Clinical Meaning | Typical Units |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor Volume | V, N | State Variable | Total number or volume of cancer cells. | mm³, cell count |

| Sensitive Cell Population | S, Ns | State Variable (Compartment) | Sub-population of cancer cells vulnerable to a specific treatment. | cell count |

| Resistant Cell Population | R, Nr | State Variable (Compartment) | Sub-population of cancer cells that survive treatment. | cell count |

| CAR-T Cell Population | C, TCAR | State Variable (Compartment) | Concentration of administered or expanded CAR-T cells in the body or tumor site [25]. | cells/μL |

| Serum Drug Concentration | Cdrug | State Variable | Concentration of a chemotherapeutic or targeted agent in the plasma. | mg/L, μM |

| Immune Effector Cells | E, I | State Variable (Compartment) | Population of native immune cells (e.g., NK cells, T cells) with anti-tumor activity. | cell count |

Table 2: Common Parameters in Cancer Treatment Models

| Parameter Name | Symbol | Biological/Clinical Meaning | Estimation Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maximal Growth Rate | r, λ | The intrinsic rate of tumor cell proliferation in the absence of constraints. | In vivo growth data, longitudinal imaging (e.g., CBCT [26]) |

| Carrying Capacity | K, θ | The maximum tumor size sustainable by the local environment and resources. | Maximum observed tumor volume in patients or animal models |

| Drug-Induced Death Rate | kd, δdrug | The rate at which a drug kills sensitive cancer cells; often a function of drug concentration. | In vitro dose-response assays, PK/PD modeling [2] |

| Drug Clearance Rate | kcl, γ | The rate at which a drug is eliminated from the body (e.g., dC/dt = -k<sub>cl</sub> × C [2]). |

Pharmacokinetic studies |

| Mutation Rate | μ, m | The probability of a sensitive cell acquiring a resistance mutation upon division. | Genomic sequencing of pre- and post-treatment samples [2] |

| CAR-T Proliferation Rate | Ï, p | The rate of CAR-T cell expansion upon antigen engagement. | In vitro co-culture assays, patient PK data [25] |

| CAR-T Killing Efficacy | kkill, η | The potency of a single CAR-T cell in eliminating tumor targets. | In vitro cytotoxicity assays, model fitting to clinical response [25] |

| Half-Maximal Effect Concentration | EC50 | The drug concentration that produces 50% of the maximal effect (Emax) in a dose-response model (e.g., Hill equation [2]). | In vitro dose-response curves |

Experimental Protocols for Parameter Estimation