A Comprehensive Guide to Pharmacophore-Based Virtual Screening for Neurodegenerative Disease Targets

This article provides a comprehensive overview of pharmacophore-based virtual screening (PBVS) protocols specifically tailored for neurodegenerative disease (NDD) targets.

A Comprehensive Guide to Pharmacophore-Based Virtual Screening for Neurodegenerative Disease Targets

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of pharmacophore-based virtual screening (PBVS) protocols specifically tailored for neurodegenerative disease (NDD) targets. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles of key NDD targets like phosphorylated tau and BACE1, details step-by-step methodological workflows for virtual screening, and addresses critical troubleshooting aspects such as Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB) permeability. Furthermore, it explores validation strategies and comparative analyses with other screening methods, offering a holistic and practical guide for integrating PBVS into the early-stage drug discovery pipeline for conditions like Alzheimer's and Huntington's disease.

Understanding Neurodegenerative Disease Targets and the Pharmacophore Concept

The Urgent Need for Alternative Therapeutic Strategies in Neurodegeneration

Neurodegenerative diseases (NDDs), such as Alzheimer's disease (AD) and Parkinson's disease (PD), represent a growing global health crisis, characterized by the progressive loss of neuronal structure and function [1] [2]. With an aging worldwide population, the prevalence of these conditions is rapidly increasing, posing significant challenges to healthcare systems and society at large [3]. The complex, multifactorial pathogenesis of NDDs—involving multiple interconnected pathological pathways—has rendered traditional single-target therapeutic approaches largely ineffective [2] [4]. This document outlines application notes and detailed protocols for implementing pharmacophore-based virtual screening (PBVS), a powerful computational approach that addresses the urgent need for novel therapeutic strategies by enabling the efficient identification of multi-target directed ligands (MTDLs) for NDD treatment.

The Complex Pathophysiology of Neurodegenerative Diseases

The development of effective treatments for NDDs has been hampered by their intricate pathophysiology, which involves several simultaneous aberrant biological processes rather than a single causative factor.

Key Pathological Mechanisms and Targets

Table 1: Major Therapeutic Targets in Neurodegenerative Disease Pathogenesis

| Target Protein | Pathological Role | Associated Disease Hallmarks |

|---|---|---|

| GSK-3β (Glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta) | Hyperactivation promotes tau hyperphosphorylation and neurofibrillary tangle formation; enhances BACE1 activity [5]. | Neurofibrillary tangles, synaptic dysfunction, neuroinflammation [2] [5]. |

| BACE-1 (Beta-secretase 1) | Key enzyme in amyloidogenic processing of APP, leading to amyloid-beta plaque formation [6]. | Amyloid plaques, synaptic toxicity, neuronal death [2] [6]. |

| NMDA Receptor (N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor) | Overactivation leads to excitotoxicity, calcium influx, and neuronal death [2]. | Excitotoxicity, synaptic dysfunction, cognitive decline [2]. |

| AChE (Acetylcholinesterase) | Enzyme that breaks down acetylcholine; its inhibition is a current symptomatic therapy [3]. | Cholinergic deficit, memory impairment, cognitive dysfunction [3]. |

The blood-brain barrier (BBB) presents a further critical challenge, as it selectively restricts over 98% of small molecules from entering the central nervous system (CNS) from the bloodstream [1]. Therefore, effective neurotherapeutics must not only engage their molecular targets but also possess inherent physicochemical properties that enable BBB permeation [1].

Pharmacophore-Based Virtual Screening: A Rational Approach

Pharmacophore-based virtual screening has emerged as a pivotal computational strategy in modern drug discovery, particularly for addressing multi-factorial diseases like NDDs [7] [8]. A pharmacophore is defined by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) as "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supra-molecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or to block) its biological response" [7] [8]. In practice, a pharmacophore model abstracts the essential chemical functionalities of a bioactive molecule into a 3D arrangement of generalized features [9]. These features include:

- Hydrogen Bond Acceptors (HBA) and Donors (HBD)

- Hydrophobic areas (H)

- Positively and Negatively Ionizable groups (PI/NI)

- Aromatic rings (AR)

- Exclusion Volumes (XVOL) representing steric constraints of the binding pocket [7] [9]

Comparative Advantages of PBVS

Table 2: Comparison of Virtual Screening Methodologies for Neurodegenerative Drug Discovery

| Characteristic | Pharmacophore-Based VS (PBVS) | Docking-Based VS (DBVS) |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Basis | Matches compounds against an ensemble of essential interaction features [7] [9]. | Fits and scores compounds within a 3D protein binding site [10]. |

| Computational Speed | Generally faster, suitable for ultra-large library screening [10]. | Slower due to conformational sampling and scoring for each compound [10]. |

| Scaffold Hopping Potential | High, as it focuses on features rather than specific atoms [7] [8]. | Lower, often biased toward known ligand chemotypes. |

| Performance | Higher enrichment factors reported in benchmark studies (14 of 16 targets) [10]. | Lower hit rates in direct comparisons [10]. |

| Data Requirements | Can work with ligand structures alone or protein-ligand complexes [7] [9]. | Requires a high-quality 3D protein structure. |

| Typical Hit Rates | 5% to 40% in prospective screening campaigns [8]. | Often below 1% in high-throughput screening [8]. |

Integrated Protocol for Pharmacophore-Based Virtual Screening

The following section provides a detailed, actionable protocol for implementing PBVS in the context of neurodegenerative disease drug discovery.

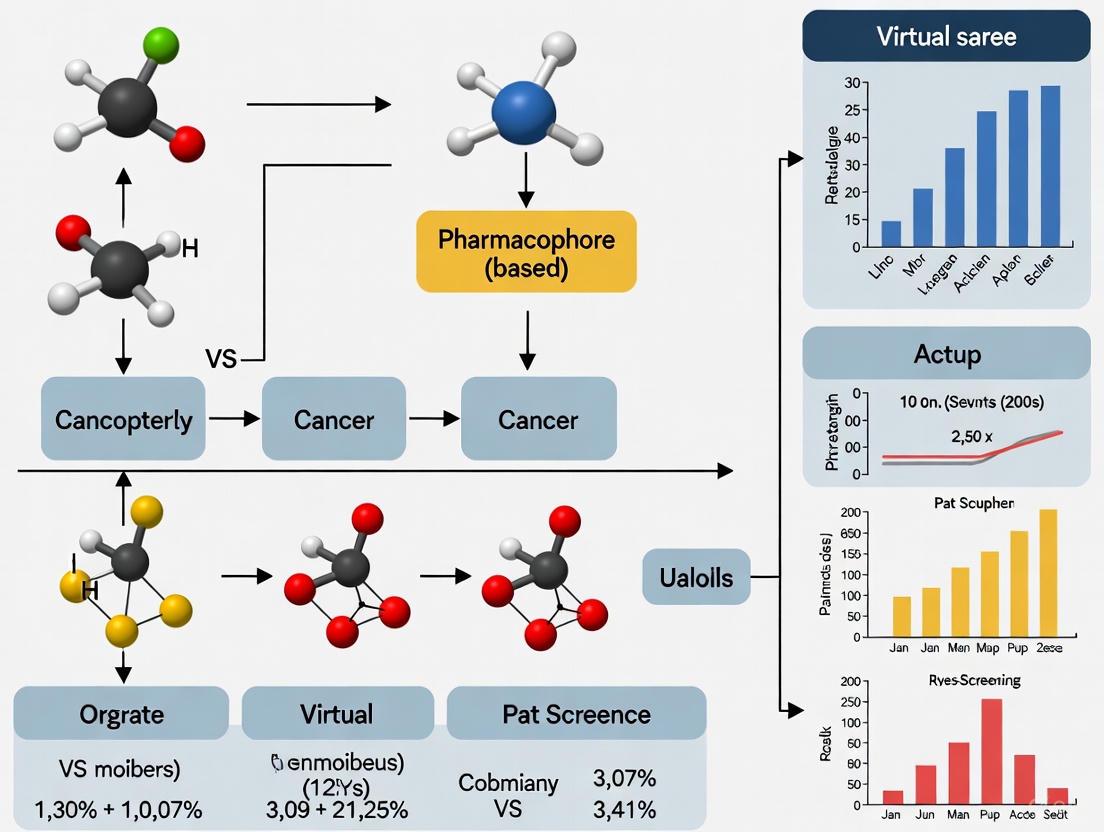

The diagram below illustrates the comprehensive workflow for a PBVS campaign, integrating both ligand-based and structure-based approaches.

Protocol 1: Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

This protocol is applicable when a three-dimensional structure of the target protein (e.g., from X-ray crystallography or homology modeling) is available [7].

Step 1: Protein Structure Preparation

- Retrieve the 3D structure of your target protein from the Protein Data Bank (PDB: www.rcsb.org) [7]. For neurodegenerative targets, relevant structures may include GSK-3β (e.g., PDB ID: 1I09), BACE-1 (e.g., PDB ID: 5HU0 [6]), or NMDA receptor complexes.

- Prepare the protein structure using molecular modeling software (e.g., Maestro [6] or Discovery Studio [8]):

- Add hydrogen atoms and correct protonation states of residues at physiological pH (7.4).

- Assign partial charges using appropriate force fields (e.g., OPLS_2005 [6]).

- Remove crystallographic water molecules unless they mediate key ligand interactions.

- Repair missing side chains or loops if necessary.

Step 2: Binding Site Characterization

- Define the ligand-binding site using one of these approaches:

- For BACE-1, the catalytic aspartic acid residues (Asp93, Asp289 [6]) are essential for defining the active site.

Step 3: Pharmacophore Feature Generation

- Extract pharmacophore features directly from protein-ligand interactions if a co-crystal structure exists [9] [8].

- Alternatively, generate features based on the binding site topology alone using programs like Discovery Studio [8] or LigandScout [10].

- Select only the most crucial features for biological activity to create a selective yet not overly restrictive hypothesis [7]. For example, a BACE-1 inhibitor pharmacophore might require features that interact with the catalytic aspartate dyad.

Step 4: Model Refinement and Validation

- Incorporate exclusion volumes (XVols) to represent the steric boundaries of the binding pocket and improve model selectivity [8].

- Validate the model by screening a test database containing known active compounds and decoys (inactive molecules with similar physicochemical properties) [8].

- Calculate quality metrics such as the Enrichment Factor (EF), Area Under the Curve of the Receiver Operating Characteristic plot (ROC-AUC), and Goodness of Hit Score (GH) to assess model performance [8].

Protocol 2: Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

This approach is used when structural information for the target protein is limited or unavailable, but a set of known active ligands is accessible [9].

Step 1: Training Set Compilation

- Curate a structurally diverse set of confirmed active molecules against your target. For neurodegenerative diseases, this might include known GSK-3β inhibitors from BindingDB [5] or AChE inhibitors from ChEMBL [8].

- Include molecules with a range of activities (e.g., IC50 values from nM to μM) to help identify features correlating with potency.

- Ensure all activity data comes from direct, target-based assays (e.g., enzyme inhibition) rather than cell-based assays, which can be confounded by pharmacokinetic effects [8].

Step 2: Conformational Analysis and Molecular Alignment

- Generate a representative set of low-energy conformers for each active molecule using algorithms such as the Poling algorithm [9] or Monte Carlo methods.

- Perform 3D structural alignment to identify common chemical features and their spatial arrangements shared by the active molecules. Software tools like Catalyst (now in Discovery Studio) or Phase can automate this process [10].

Step 3: Hypothesis Generation and Selection

- Identify conserved pharmacophore features (HBA, HBD, hydrophobic, aromatic, ionizable) across the aligned active molecules.

- Generate multiple pharmacophore hypotheses and select the best model based on its ability to:

- Retrieve known active compounds from a validation database.

- Exclude known inactive molecules or decoys.

- Correlate with quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) data if available [9].

Protocol 3: Virtual Screening and Hit Identification

Step 1: Database Preparation

- Select a compound library for screening (e.g., ZINC, PubChem, Natural Product libraries [2], or in-house collections).

- Prepare the database by generating multiple conformers for each compound and filtering for drug-like properties using Lipinski's Rule of Five [2] [5]. For CNS targets, apply additional filters for BBB permeability using tools like SwissADME [1].

- For neurodegenerative diseases, prioritize libraries containing natural products or fungal metabolites, which have shown promising neuroprotective properties [1] [2].

Step 2: Pharmacophore-Based Screening

- Screen the prepared database against your validated pharmacophore model using programs such as Pharmit [1] [9], LigandScout [10], or Phase [6].

- Use the phase screen score (a combination of volume score, RMSD, and site matching) to rank hits; a common threshold is a phase score >1.9 [6].

- For multi-target drug discovery, screen the same compound library against pharmacophore models for different NDD targets (e.g., GSK-3β, BACE-1, and NMDA receptor) to identify potential MTDLs [2].

Step 3: Post-Screening Analysis and Experimental Prioritization

- Subject the top-ranking virtual hits to molecular docking studies against all target structures to refine binding pose predictions and estimate binding affinities [2] [6].

- Perform ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, Toxicity) profiling using tools like QikProp [6] or ADMETlab 2.0 [6] to eliminate compounds with unfavorable pharmacokinetic or toxicity profiles.

- Select a final list of candidate compounds (typically 10-20) for experimental validation through in vitro assays.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for PBVS in Neurodegenerative Disease Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tools & Databases | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Structure Resources | RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB) [7], AlphaFold2 [7] | Source of experimental and predicted 3D protein structures for structure-based pharmacophore modeling. |

| Compound Libraries | ZINC15 [1], PubChem [2], ChEMBL [8], DrugBank [8], Natural Product libraries [2] | Collections of small molecules for virtual screening; source of potential hit compounds. |

| Pharmacophore Modeling Software | LigandScout [9] [10], Discovery Studio [9] [8], MOE [9], Phase [6] | Platforms for creating, visualizing, and validating pharmacophore models using both structure-based and ligand-based approaches. |

| Virtual Screening Servers | Pharmit [1] [9], PharmMapper [9] | Web-based tools for performing rapid pharmacophore-based screening of compound databases. |

| Validation & Decoy Sets | DUD-E (Directory of Useful Decoys, Enhanced) [8] [5] | Provides carefully selected decoy molecules to assess the selectivity and performance of pharmacophore models. |

| ADMET Prediction Tools | QikProp [6], SwissADME [6], ADMETlab 2.0 [6] | Predict pharmacokinetic properties, drug-likeness, and potential toxicity of virtual hits. |

Case Study: Successful Application in Neurodegenerative Disease Research

A recent study exemplifies the power of PBVS for identifying multi-target inhibitors for AD treatment [2]. Researchers screened a library of 17,544 fungal metabolites against three key AD targets: GSK-3β, the NMDA receptor, and BACE-1. The workflow proceeded as follows:

- An initial pharmacophore-based screening and drug-likeness filtering narrowed the library to 14 best hits.

- Molecular docking studies identified Bisacremine-C as the most promising multi-target ligand, showing high binding affinity for all three targets.

- Molecular dynamics simulations (100 ns) confirmed the stability of the Bisacremine-C complexes, with stable root mean square deviation (RMSD) values and key interactions maintained throughout the simulation [2].

This case demonstrates how PBVS can efficiently identify novel, naturally derived chemical scaffolds with potential multi-target activity, addressing the complex pathophysiology of AD.

The urgent need for alternative therapeutic strategies in neurodegeneration demands innovative approaches that can address the multi-factorial nature of these devastating diseases. Pharmacophore-based virtual screening represents a powerful, rational drug discovery paradigm that can significantly accelerate the identification of novel, effective therapeutic candidates. By enabling the systematic exploration of vast chemical space and the targeted discovery of multi-target directed ligands, PBVS offers a promising path forward in the challenging landscape of neurodegenerative disease drug development. The detailed protocols and resources provided in this document offer researchers a practical framework for implementing these advanced computational methods in their own neurotherapeutic discovery pipelines.

Alzheimer's disease (AD) and related tauopathies represent a significant challenge in neurodegenerative disease research, characterized by the pathological accumulation of specific proteins in the brain. The microtubule-associated protein tau (MAPT) and the β-site amyloid precursor protein cleaving enzyme 1 (BACE1) have emerged as two of the most promising therapeutic targets for disease-modifying strategies [11] [12]. In Alzheimer's disease, the pathological features include amyloid-beta (Aβ) deposits and neurofibrillary tangles composed of hyperphosphorylated tau, which lead to synaptic impairment and neuronal degeneration [11]. Tauopathies encompass a spectrum of disorders, including Pick's disease, frontotemporal dementia, corticobasal degeneration, argyrophilic grain disease, and progressive supranuclear palsy, all resulting from misprocessing and accumulation of tau within neuronal and glial cells [11]. This application note provides a comprehensive overview of these key protein targets and details experimental protocols for pharmacophore-based virtual screening, enabling researchers to identify novel therapeutic compounds targeting these critical pathways.

Key Protein Targets: Mechanisms and Pathological Significance

Tau Protein: Structure, Function, and Dysregulation

The tau protein is a neuron-enriched microtubule-associated protein encoded by the MAPT gene located on chromosome 17q21.31 [13]. Through alternative splicing of exons 2, 3, and 10, the MAPT gene generates six major tau isoforms in the human central nervous system, classified as 0N3R, 1N3R, 2N3R, 0N4R, 1N4R, and 2N4R based on the presence of N-terminal inserts (0N, 1N, 2N) and the number of microtubule-binding repeats (3R or 4R) [13] [14]. Under physiological conditions, tau stabilizes microtubules, regulates axonal transport, and participates in synaptic plasticity [13]. The normal human brain maintains a 1:1 ratio between 3R and 4R tau isoforms, with alterations in this ratio characterizing various tauopathies [11].

In pathological states, tau undergoes abnormal post-translational modifications, particularly hyperphosphorylation, which reduces its affinity for microtubules and promotes aggregation into neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) [11] [13]. These modifications are driven by an imbalance between kinase and phosphatase activities, with reduced protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) activity and increased kinase activity contributing to the hyperphosphorylated state [13]. The accumulation of pathological tau disrupts synaptic function, impairs neuronal communication, and ultimately leads to neurodegeneration [11]. The propagation of tau pathology follows a prion-like pattern, with misfolded tau spreading from neuron to neuron and seeding aggregation of endogenous tau in recipient cells [14].

Table 1: Tau Isoforms in the Human Brain and Their Characteristics

| Isoform Name | N-terminal Inserts | Microtubule-Binding Repeats | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0N3R | 0 | 3 | Lacks both N-terminal inserts; 3 repeat domains |

| 1N3R | 1 | 3 | Contains one N-terminal insert; 3 repeat domains |

| 2N3R | 2 | 3 | Contains two N-terminal inserts; 3 repeat domains |

| 0N4R | 0 | 4 | Lacks both N-terminal inserts; 4 repeat domains |

| 1N4R | 1 | 4 | Contains one N-terminal insert; 4 repeat domains |

| 2N4R | 2 | 4 | Contains two N-terminal inserts; 4 repeat domains |

BACE1: Role in Amyloid Pathology and Beyond

BACE1 is a membrane-associated aspartyl protease that initiates the cleavage of amyloid precursor protein (APP) in the amyloidogenic pathway [12]. This cleavage represents the rate-limiting step in the generation of amyloid-beta (Aβ) peptides, which aggregate to form amyloid plaques in Alzheimer's disease [15] [12]. The proteolytic pocket of BACE1 is relatively large and accommodates up to 11 residues, presenting both challenges and opportunities for inhibitor development [12]. Genetic evidence supports BACE1 inhibition as a therapeutic strategy, as germline deletion of BACE1 in mouse models abrogates Aβ production and ameliorates cognitive deficiencies [12]. Furthermore, a rare human mutation (A673T) at the BACE1 cleavage site of APP results in reduced Aβ production and decreased AD risk [12].

Recent research has revealed that BACE1 inhibition not only reduces Aβ generation but also affects downstream tau pathology. Studies in APP transgenic mice demonstrate that BACE1 inhibition prevents the age-related increase of tau in cerebrospinal fluid, suggesting a downstream effect on tau pathophysiology [16] [17]. This finding is particularly significant as it indicates that targeting the upstream amyloid pathway may also modulate tau-related pathology, providing a dual therapeutic benefit.

Experimental Protocols for Target Validation and Compound Screening

Pharmacophore-Based Virtual Screening Protocol for BACE1 Inhibitors

Objective: To identify novel BACE1 inhibitors through pharmacophore-based virtual screening of commercial compound libraries.

Materials and Software:

- Protein Data Bank (PDB ID: 6EJ3 or 5HU0 for BACE1) [18] [15]

- Schrödinger Suite (Phase module, Glide, QikProp) [18] [15]

- Commercial compound databases (VITAS-M Laboratory, ZINC, Enamine, Asinex) [18] [15]

- Hardware: Multi-core processor workstation with ≥16 GB RAM

Procedure:

Protein Preparation:

- Retrieve the crystal structure of BACE1 (PDB ID: 6EJ3) from the Protein Data Bank [18].

- Preprocess the protein by adding hydrogen atoms, assigning proper bond orders and charges.

- Remove water molecules and optimize the structure using the OPLS_2005 force field [18].

- Generate a grid box centered on the active site coordinates (x = 38.29, y = 59.94, z = 50.33) [18].

Pharmacophore Model Development:

- Develop a receptor-ligand-based pharmacophore model using the Phase tool in Schrödinger [15].

- Identify critical pharmacophore features from the co-crystal ligand interactions: two aromatic rings (R19, R20), one hydrogen bond donor (D12), and one hydrogen bond acceptor (A8) [18].

- Validate the model using known active and inactive compounds.

Database Preparation:

Virtual Screening:

Molecular Docking:

Binding Free Energy Calculations:

ADMET Prediction:

- Evaluate drug-likeness using QikProp, SwissADME, or ADMETlab 2.0 [15].

- Apply Lipinski's Rule of Five and assess toxicity parameters.

Molecular Dynamics Simulation:

- Perform MD simulations using GROMACS with GROMOS96 43a1 force field [18].

- Solvate the system with explicit SPC water model and neutralize with counterions.

- Conduct energy minimization, NVT and NPT equilibration, followed by production run (≥50 ns) [18].

- Analyze trajectories for RMSD, RMSF, and hydrogen bonding.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Resources for Tau and BACE1 Studies

| Research Reagent | Function/Application | Specifications/Examples |

|---|---|---|

| BACE1 Crystal Structure | Structure-based drug design | PDB ID: 6EJ3, 5HU0 [18] [15] |

| MAPT Gene Constructs | Study tau isoform expression and function | 0N3R, 1N3R, 2N3R, 0N4R, 1N4R, 2N4R isoforms [13] |

| Phospho-specific Tau Antibodies | Detection of pathological tau | Anti-p-tau181, Anti-p-tau217 [19] |

| Commercial Compound Databases | Virtual screening libraries | VITAS-M, ZINC, Enamine, Asinex [18] |

| ADMET Prediction Tools | Assessment of drug-likeness | QikProp, SwissADME, ADMETlab 2.0 [15] |

Experimental Validation of Tau-Targeted Compounds

Objective: To evaluate candidate compounds for modulation of tau phosphorylation and aggregation.

Cell-Based Assay Protocol:

Cell Culture:

- Maintain neuronal cell lines (e.g., SH-SY5Y, PC12) or primary neuronal cultures under standard conditions.

- Transfert cells with MAPT constructs expressing different tau isoforms as needed.

Compound Treatment:

- Apply candidate compounds at varying concentrations (1 nM-100 μM).

- Include positive controls (kinase inhibitors, e.g., GSK-3β inhibitors).

- Treat for 24-72 hours based on experimental design.

Tau Phosphorylation Analysis:

- Lyse cells and extract proteins using RIPA buffer with phosphatase and protease inhibitors.

- Perform Western blotting using phosphorylation-specific tau antibodies (p-tau181, p-tau217, etc.) [19].

- Quantify band intensities and normalize to total tau levels.

Tau Aggregation Assessment:

- Perform immunofluorescence staining for tau and observe aggregation patterns.

- Use thioflavin S or T staining to detect fibrillar tau aggregates.

- Quantify aggregate number and size using image analysis software.

Biomarker Assessment Protocol:

Sample Collection:

- Collect cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) or blood plasma samples from model systems or human subjects.

Biomarker Analysis:

Data Interpretation:

- Correlate biomarker levels with disease progression and cognitive measures.

- Evaluate treatment effects on biomarker trajectories.

Pathway Visualization and Therapeutic Strategies

The following diagrams illustrate key signaling pathways and experimental workflows for targeting tau and BACE1 in Alzheimer's disease and tauopathies.

Diagram 1: Key Pathological Pathways in Alzheimer's Disease. This diagram illustrates the amyloid pathway involving BACE1 cleavage of APP and the tau pathology pathway leading to neurofibrillary tangle formation, highlighting the interaction between these two key processes.

Diagram 2: Virtual Screening Workflow for BACE1 Inhibitors. This diagram outlines the comprehensive computational pipeline for identifying novel BACE1 inhibitors, from target identification to experimental validation of hit compounds.

The therapeutic landscape for Alzheimer's disease and tauopathies is rapidly evolving, with tau and BACE1 representing two of the most promising targets for disease modification. The experimental protocols outlined in this application note provide researchers with robust methodologies for target validation and compound screening. Pharmacophore-based virtual screening has demonstrated significant utility in identifying novel inhibitors, as evidenced by the discovery of compounds such as ZINC39592220 and 66H with potent activity against BACE1 [18] [15]. As of 2025, the therapeutic pipeline includes 170 drugs in development, with 32 candidates in clinical trials targeting tau pathology [14]. The integration of biomarker assessment, particularly p-tau217 and NfL measurements in blood, provides valuable tools for patient stratification and treatment monitoring [19]. These advanced experimental approaches will continue to drive the development of effective therapeutics for these devastating neurodegenerative disorders.

The pharmacophore, a cornerstone concept in modern drug discovery, represents the ensemble of steric and electronic features necessary for a molecule to trigger or block a biological response [20]. Its conceptual origins trace back to Paul Ehrlich in the early 20th century, who first introduced the term to describe the molecular framework carrying essential features responsible for a drug's biological activity [20]. The conceptual foundation was profoundly shaped by Emil Fischer's 1894 lock-and-key model, which used an analogy between an enzyme (the lock) and a substrate (the key) to illustrate the necessity of a matching shape for biological recognition [21]. This seminal idea established that the preference of an enzyme for given substrates is attributed to the quality of the geometric and electronic match between them.

Over the past century, the basic pharmacophore concept has retained its core meaning while expanding considerably in application and technical sophistication. The contemporary definition, as formalized by IUPAC, describes a pharmacophore as "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or to block) its biological response" [22] [7] [20]. This evolution from Fischer's rigid lock-and-key analogy has progressed through several key stages:

- Induced-Fit and Selected-Fit Models: These expanded Fischer's rigid model to account for the flexibility of both ligand and enzyme, recognizing that binding can induce conformational changes or select for pre-existing reactive conformations [21].

- Keyhole-Lock-Key Model: A more recent proposal addressing enzymes with buried active sites, this model incorporates the importance of substrate entry and product exit pathways (tunnels or "keyholes") in catalysis and discrimination [21].

- Modern 3D Pharmacophore Mapping: Today, pharmacophores are abstract representations of essential chemical interactions, represented as geometric entities in three-dimensional space for computer-aided drug design [22].

Table 1: Core Pharmacophore Feature Types and Their Interactions

| Feature Type | Geometric Representation | Complementary Feature Type(s) | Interaction Type(s) | Structural Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen-Bond Acceptor (HBA) | Vector or Sphere | HBD | Hydrogen-Bonding | Amines, Carboxylates, Ketones, Alcoholes, Fluorine Substituents |

| Hydrogen-Bond Donor (HBD) | Vector or Sphere | HBA | Hydrogen-Bonding | Amines, Amides, Alcoholes |

| Aromatic (AR) | Plane or Sphere | AR, PI | π-Stacking, Cation-π | Any Aromatic Ring |

| Positive Ionizable (PI) | Sphere | AR, NI | Ionic, Cation-π | Ammonium Ion, Metal Cations |

| Negative Ionizable (NI) | Sphere | PI | Ionic | Carboxylates |

| Hydrophobic (H) | Sphere | H | Hydrophobic Contact | Halogen Substituents, Alkyl Groups, Alicycles, weakly or non-polar aromatic Rings |

| Exclusion Volume (XVOL) | Sphere | N/A | Steric Hindrance | Representation of forbidden areas in the binding pocket |

Modern Pharmacophore Modeling Methodologies

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

Structure-based pharmacophore modeling leverages the three-dimensional structure of a macromolecular target, obtained from X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, or computational methods like homology modeling, to derive essential interaction features [7]. The quality of the input protein structure directly influences the model's reliability, necessitating careful preparation steps including protonation state assignment, hydrogen atom addition, and energy minimization [7]. When a protein-ligand complex structure is available, the process is more straightforward: the bound ligand's bioactive conformation directly guides the identification and spatial placement of pharmacophore features corresponding to its functional groups engaged in target interactions [7]. The receptor structure further enables the incorporation of shape constraints through exclusion volumes (also called exclusion spheres), which represent sterically forbidden regions of the binding pocket that ligands must avoid [22] [7].

For targets where only the unbound (apo) structure is available, the modeling becomes more challenging. In such cases, computational tools like GRID or LUDI probe the binding site to identify favorable interaction points for various chemical functional groups, generating a map of potential interaction sites [7]. This typically produces an overabundance of features, requiring careful selection based on conservation analysis, energetic contributions, or known key residues to create a refined, selective pharmacophore hypothesis [7] [20].

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

In the absence of a macromolecular target structure, ligand-based pharmacophore modeling provides a powerful alternative. This approach deduces the essential pharmacophore features by analyzing the three-dimensional structures of a set of known active ligands that bind to the same receptor site in the same orientation [22] [7]. A critical prerequisite is that these active ligands should represent a range of chemical scaffolds to ensure the identification of truly essential common features rather than scaffold-specific artifacts [20].

The process involves several technically challenging steps. First, a conformational analysis is performed for each ligand to generate a set of low-energy conformers, as the bioactive conformation is rarely known a priori [23]. Evidence suggests the energy difference between the bioactive conformation and the global minimum of the isolated molecule is generally less than 12 kJ/mol (3 kcal/mol), allowing higher-energy conformers to be filtered out [23]. Subsequently, common chemical features are identified across the active molecules, and their optimal spatial arrangement is determined through systematic or algorithmic superimposition [23]. The quality of the resulting model can be validated by ensuring it can distinguish known active compounds from inactive ones and by assessing its predictive power through statistical measures [20].

AI-Enhanced Pharmacophore Modeling

Recent advances incorporate artificial intelligence to address longstanding challenges in pharmacophore-guided drug discovery. The DiffPhore framework represents a pioneering knowledge-guided diffusion model for "on-the-fly" 3D ligand-pharmacophore mapping [24] [25]. This method leverages ligand-pharmacophore matching knowledge to guide ligand conformation generation while utilizing calibrated sampling to mitigate exposure bias in the iterative conformation search process [24].

DiffPhore comprises three main modules: a knowledge-guided ligand-pharmacophore mapping (LPM) encoder that incorporates rules for pharmacophore type and direction matching; a diffusion-based conformation generator that estimates translation, rotation, and torsion transformations for the ligand; and a calibrated conformation sampler that adjusts the perturbation strategy to narrow the discrepancy between training and inference phases [24] [25]. Trained on complementary datasets (CpxPhoreSet from experimental complexes and LigPhoreSet from diverse ligand conformations), DiffPhore has demonstrated state-of-the-art performance in predicting ligand binding conformations, surpassing traditional pharmacophore tools and several advanced docking methods [24] [25].

Application Notes: Pharmacophore-Based Virtual Screening for Neurodegenerative Targets

Case Study: Targeting BACE1 for Alzheimer's Disease

β-secretase 1 (BACE1) is a membrane-associated aspartate protease critically involved in the production of amyloid-beta peptides, whose accumulation is central to Alzheimer's disease pathology [15]. Despite extensive efforts, developing effective BACE1 inhibitors has proven challenging, creating an urgent need for novel therapeutic approaches [15]. A recent pharmacophore-based virtual screening study demonstrates a comprehensive protocol for identifying new BACE1 inhibitors [15].

The study began with receptor-ligand-based pharmacophore hypothesis development using a BACE1 co-crystal structure (PDB ID: 5HU0) and its high-activity ligand [15]. The Schrödinger Phase tool was employed to generate the pharmacophore model targeting the protein-binding pocket [15]. Subsequent virtual screening of 200,000 compounds from the VITAS-M Laboratory database identified hits using phase screen scores (a composite metric combining volume score, RMSD, and site matching), with compounds scoring >1.9 selected for further analysis [15]. This was followed by ADMET profiling using QikProp, SwissADME, and ADMETlab 2.0 to evaluate drug-likeness and toxicity parameters according to Lipinski's Rule of Five [15].

Promising candidates underwent molecular docking studies with the prepared BACE1 structure, which involved preprocessing (adding hydrogens, assigning charges), eliminating water molecules, and energy minimization using the OPLS_2005 force field [15]. The top candidate, compound 66H, showed a binding mode similar to the reference ligand, forming key hydrogen bonds with Asp93, Asp289, and Gly291, along with van der Waals and hydrophobic interactions [15]. Molecular dynamics simulations over 100 ns confirmed the stability of the 66H-BACE1 complex, with RMSD values maintaining stability between 2.5-3 Å after equilibration, comparable to the reference compound [15]. Finally, MM/GBSA analysis calculated the total binding free energies (ΔGtotal) for both complexes, providing quantitative assessment of binding affinity [15].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Pharmacophore-Based Screening

| Reagent/Resource | Category | Function in Research | Example Source/Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Structural Database | Repository for experimental 3D structures of proteins and nucleic acids; source of target structures for structure-based modeling. | RCSB PDB (https://www.rcsb.org/) [7] [15] |

| Commercial Compound Databases | Chemical Database | Curated collections of purchasable compounds for virtual screening hits identification. | VITAS-M Laboratory, ZINC20 [24] [15] |

| Schrödinger Phase | Software Module | Tool for pharmacophore model development, virtual screening, and hypothesis generation. | Commercial Software [15] |

| AncPhore | Software Tool | Anchor pharmacophore tool for generating 3D ligand-pharmacophore pairs and virtual screening. | Academic/Commercial Software [24] [25] |

| OPLS Force Fields | Computational Parameter Set | Optimized potentials for liquid simulations; used for molecular mechanics energy minimization and dynamics. | OPLS_2005 [15] |

| QikProp | Software Module | Predicts ADMET properties and drug-likeness for candidate compounds. | Commercial Software [15] |

Targeting Phosphorylated Tau in Alzheimer's and Tauopathies

Phosphorylated tau (P-tau) has emerged as a promising therapeutic target for Alzheimer's disease and other tauopathies due to its involvement in synaptic damage and neuronal dysfunction [26]. In diseased states, tau undergoes hyperphosphorylation at specific serine and threonine residues, leading to defective microtubule interactions, impaired axonal transport, and ultimately synaptic damage and neuronal death [26]. This pathological transformation creates opportunities for pharmacophore-based approaches to identify inhibitors of tau phosphorylation or compounds that disrupt abnormal P-tau interactions.

Key kinases involved in tau phosphorylation include proline-directed proteins, mitogen-activated proteins, cyclin-dependent kinases (Cdks), protein kinase A (PKA), and calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (CaMK) [26]. Hyperphosphorylation at Cdk sites (Ser235, Ser202, Ser404) promotes self-aggregation of tau filaments, while phosphorylation at Ser/Thr sites targeting PKA (Ser214, Ser324, Ser356, etc.) contributes to the pathological state [26]. Pharmacophore models targeting these kinase enzymes or designed to disrupt the aberrant interaction between P-tau and mitochondrial fission protein Drp1 (which leads to excessive mitochondrial fragmentation) represent promising strategies for therapeutic intervention [26].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling and Virtual Screening

Objective: To generate a structure-based pharmacophore model and utilize it for virtual screening against neurodegenerative disease targets.

Materials and Software:

- Protein Data Bank (https://www.rcsb.org/)

- Molecular modeling software with pharmacophore capabilities (e.g., Schrödinger Suite, MOE, Discovery Studio)

- Commercial or in-house compound database for screening

- High-performance computing resources

Procedure:

Target Identification and Structure Preparation

- Retrieve the 3D crystal structure of the target protein (e.g., BACE1 for Alzheimer's) from the PDB. Prefer structures with high resolution and co-crystallized ligands.

- Prepare the protein structure by adding hydrogen atoms, assigning appropriate protonation states at physiological pH (e.g., using PropKa), and correcting for missing residues or atoms if necessary.

- Perform energy minimization using a suitable force field (e.g., OPLS_2005) to relieve steric clashes and optimize the structure.

Binding Site Analysis and Pharmacophore Feature Generation

- Define the ligand-binding site using the coordinates of the co-crystallized ligand or through binding site detection algorithms (e.g., GRID, LUDI).

- Generate an initial set of pharmacophore features by analyzing interactions between the protein and the bound ligand (if present) or by mapping complementary chemical features in the binding site.

- Select the most relevant features for bioactivity based on conservation, energetic contribution, or known key residues. Include hydrogen bond acceptors/donors, hydrophobic areas, charged/ionizable groups, and aromatic rings as appropriate.

Exclusion Volumes and Model Validation

- Add exclusion volumes around protein atoms lining the binding pocket to represent steric constraints that ligands must avoid.

- Validate the initial model by ensuring it can successfully recognize known active compounds and reject inactive molecules from a test set.

Database Preparation and Virtual Screening

- Prepare a 3D compound database by generating multiple conformers for each molecule and filtering based on drug-likeness rules if desired.

- Screen the database against the pharmacophore model using a fitness score that accounts for feature matching and spatial alignment.

- Select top-ranking compounds (e.g., phase screen score >1.9) for subsequent analysis.

Hit Validation and Characterization

- Subject selected hits to molecular docking studies to refine binding pose predictions and assess interaction energy.

- Perform ADMET prediction to evaluate pharmacokinetic and toxicity profiles.

- Select promising candidates for experimental validation through biochemical or cell-based assays.

Protocol: Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Generation Using Multiple Active Compounds

Objective: To develop a ligand-based pharmacophore model when the 3D structure of the target protein is unavailable.

Materials and Software:

- A set of 3-20 known active compounds with diverse chemical scaffolds but similar biological activity on the same target

- Conformational analysis software (e.g., CONFGEN, OMEGA)

- Pharmacophore modeling software (e.g., Schrödinger Phase, Catalyst)

Procedure:

Training Set Selection and Conformational Analysis

- Curate a set of structurally diverse active compounds confirmed to act on the same biological target through the same mechanism.

- Generate a comprehensive set of low-energy conformers for each compound, ensuring adequate coverage of conformational space while excluding high-energy conformations (typically >10-12 kJ/mol above global minimum).

Common Feature Identification and Model Generation

- Use automated algorithms (e.g., HipHop, Common Feature Approach) to identify pharmacophoric features common to the active compounds and their spatial relationships.

- Superimpose the compounds based on these common features to identify the best alignment that maximizes molecular overlap of essential functionalities.

Model Validation and Refinement

- Validate the model using a test set of known active and inactive compounds to determine its selectivity and predictive power.

- Refine the model by adjusting feature tolerances or removing redundant features to improve its ability to distinguish actives from inactives.

Application to Virtual Screening

- Apply the validated model to screen compound databases as described in the structure-based protocol.

- Use the model for scaffold hopping to identify novel chemotypes that maintain the essential pharmacophore features.

The Rationale for Pharmacophore-Based Screening in CNS Drug Discovery

The discovery and development of therapeutics for Central Nervous System (CNS) diseases present unique challenges, primarily due to the restrictive nature of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and the complex, multifactorial pathophysiology of neurodegenerative disorders [1]. Computer-Aided Drug Discovery (CADD) techniques, particularly pharmacophore-based virtual screening, have emerged as powerful tools to reduce the time and cost associated with developing novel drugs, making them particularly valuable for addressing health emergencies and the diffusion of personalized medicine [7]. A pharmacophore is formally defined as "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or to block) its biological response" [7]. This approach abstracts molecular functionalities into geometric entities—such as hydrogen bond acceptors (HBAs), hydrogen bond donors (HBDs), hydrophobic areas (H), positively and negatively ionizable groups (PI/NI), and aromatic groups (AR)—allowing for the identification of bioactive compounds regardless of their underlying chemical scaffold [7]. This article delineates the rationale for employing pharmacophore-based screening in CNS drug discovery, detailing its fundamental principles, practical protocols, and application within a broader research framework focused on neurodegenerative disease targets.

Scientific Rationale and Advantages

The Imperative for Novel CNS Therapeutics

Neurodegenerative diseases (NDDs), such as Alzheimer's disease (AD) and Parkinson's disease (PD), represent a significant and growing global health burden. These conditions are characterized by the progressive degeneration of neurons, leading to cognitive decline, motor dysfunction, and extensive brain damage [1] [27]. The highly selective blood-brain barrier, while crucial for maintaining brain homeostasis, poses a major obstacle for drug delivery; it is estimated that only about 2% of potential therapeutic agents can cross the intact BBB to reach their targets in the brain [1]. This limitation, combined with the multifactorial nature of CNS disorders—often involving dysregulation of complex protein networks and multiple neurotransmitter systems—necessitates innovative drug discovery approaches [28].

Pharmacophore Screening in the CADD Landscape

Pharmacophore-based virtual screening (PBVS) occupies a critical space in the CADD toolkit. It serves as an efficient method for screening large libraries of compounds in silico to identify those most likely to bind to a specific target and possess desired biological activity [7]. Benchmark studies have demonstrated that PBVS often outperforms docking-based virtual screening (DBVS) in retrieving active compounds from large databases [29]. A comparative study across eight diverse protein targets revealed that in 14 out of 16 virtual screening sets, PBVS achieved higher enrichment factors than DBVS, with significantly higher average hit rates at the top 2% and 5% of ranked database compounds [29]. This superior performance, coupled with its computational efficiency, makes PBVS particularly well-suited for the initial stages of drug discovery pipelines.

Key Advantages for CNS Drug Discovery

- Scaffold Hopping Capability: By focusing on essential functional features rather than specific atomic structures, pharmacophore models can identify chemically diverse compounds that share the necessary bioactivity, potentially leading to novel chemotypes with improved properties [7].

- Multi-Target Drug Design (Polypharmacology): The complex pathophysiology of many neurodegenerative diseases often requires simultaneous modulation of multiple targets. Pharmacophore approaches facilitate the design of Multi-Target Directed Ligands (MTDLs) by identifying common pharmacophoric elements against different targets, which can be merged into a single molecule [2] [28]. This strategy can lead to improved efficacy, broader therapeutic coverage of disease symptoms, and simplified pharmacokinetic profiles [28].

- Efficient Pre-Filtering for BBB Permeability: Pharmacophore models can incorporate features predictive of BBB penetration, allowing for the early prioritization of compounds with a higher likelihood of reaching CNS targets [1] [27]. This is crucial given that CNS-active drugs must possess specific physicochemical properties, such as appropriate lipophilicity, low molecular weight, and a balanced number of hydrogen bond donors and acceptors [27].

Table 1: Key Pharmacophore Features and Their Chemical Significance

| Feature Type | Symbol | Chemical Significance | Role in CNS Drug Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Bond Acceptor | HBA | Atom capable of accepting a H-bond (e.g., O, N) | Influces solubility and specific target binding |

| Hydrogen Bond Donor | HBD | Atom with a bound hydrogen that can be donated (e.g., OH, NH) | Affects membrane permeability and BBB penetration |

| Hydrophobic Area | H | Non-polar molecular region | Promotes passive diffusion through lipid bilayers |

| Positively Ionizable | PI | Functional group that can carry a positive charge (e.g., amine) | Can facilitate interaction with negatively charged membrane surfaces |

| Aromtic Ring | AR | Planar, conjugated ring system | Promotes π-π stacking interactions with target proteins |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

The typical workflow for pharmacophore-based screening in CNS drug discovery involves sequential steps from target identification to lead validation. The following diagram illustrates this integrated process:

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling Protocol

Objective: To generate a pharmacophore model using the three-dimensional structural information of a macromolecular target.

Procedure:

- Protein Structure Preparation:

- Retrieve the 3D structure of the target protein (e.g., BACE-1, MAO-B, GSK-3β) from the RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB) [7] [15]. If an experimental structure is unavailable, employ homology modeling or machine learning-based methods like AlphaFold2 [7].

- Prepare the protein structure using molecular modeling software (e.g., Maestro, MOE). This involves adding hydrogen atoms, assigning partial charges, correcting protonation states of residues, and optimizing the structure using a force field like OPLS_2005 [7] [15].

- Critically evaluate the structure's quality, checking for missing residues or atoms and assessing stereochemical parameters [7].

Ligand-Binding Site Characterization:

- If the protein structure is co-crystallized with a ligand, the binding site is defined by the ligand's location.

- For apo structures, use bioinformatics tools like GRID or LUDI to detect potential binding pockets by analyzing the protein surface based on geometric and energetic properties [7].

Pharmacophore Feature Generation and Selection:

- Analyze the binding site to identify key interaction points. The software (e.g., Schrödinger Phase, LigandScout) maps features like HBA, HBD, hydrophobic regions, and charged groups onto the binding pocket [7] [29] [15].

- Select only the most crucial features for bioactivity to create a selective and reliable pharmacophore hypothesis. This can be done by removing features that do not contribute significantly to binding energy or by considering conserved interactions across multiple protein-ligand complexes [7] [29].

- Incorporate exclusion volumes (XVOL) to represent the steric constraints of the binding pocket, preventing the selection of compounds that would cause steric clashes [7].

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling Protocol

Objective: To develop a pharmacophore model when the 3D structure of the target protein is unknown, using a set of known active ligands.

Procedure:

- Training Set Compilation:

- Curate a set of diverse, experimentally validated active compounds against the target of interest. These can be gathered from literature or databases like ChEMBL or PubChem [27] [30].

- Include known inactive compounds if the goal is to build a quantitative model that discriminates between active and inactive molecules.

Conformational Analysis and Molecular Alignment:

- Generate a representative set of low-energy conformations for each molecule in the training set. This is typically done using algorithms that perform a systematic or stochastic search of the conformational space [30].

- Use software like PharmaGist or the Phase module in Schrödinger to align the conformations of the active molecules based on their common chemical features [27] [30].

Hypothesis Generation and Validation:

- The software identifies the common steric and electronic features shared by the aligned molecules and constructs one or more pharmacophore hypotheses [27] [30].

- Each hypothesis is scored based on how well it aligns the training set compounds and its ability to distinguish between known actives and inactives. The highest-ranked hypothesis is selected for virtual screening [27] [30].

Integrated Virtual Screening and Validation Protocol

Objective: To screen large compound libraries using the pharmacophore model and validate the resulting hits.

Procedure:

- Database Preparation:

- Select a commercial database (e.g., ZINC15, Vitas-M Laboratory, natural product libraries) or an in-house corporate library [15] [2] [31].

- Prepare the database by generating multiple low-energy 3D conformers for each compound. Generate likely ionization and tautomeric states at physiological pH (e.g., using Epik) and filter out high-energy tautomers [15].

Pharmacophore-Based Virtual Screening:

- Use the pharmacophore model as a 3D query to screen the prepared database. Software such as Catalyst, ZINCPharmer, or Phase is employed for this purpose [29] [15] [27].

- Set parameters like maximum RMSD (e.g., 1.5 Å) for fitting the compounds to the model. The screening output is typically ranked using a scoring function (e.g., Phase Screen Score) that considers factors like volume overlap, RMSD, and the number of matched features [15] [27].

- Select top-ranking compounds (e.g., those with a Phase Screen Score >1.9) for further analysis [15].

ADMET and Drug-Likeness Filtering:

- Subject the virtual hits to predictive analysis of Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties. This is a critical step for CNS drugs to ensure potential BBB permeability and minimize safety risks [1] [15] [27].

- Use tools like QikProp, SwissADME, or ADMETlab 2.0 to compute key descriptors. Filter compounds based on Lipinski's Rule of Five, CNS multiparameter optimization (MPO) scores, and the absence of toxicophores [1] [15] [27].

Molecular Docking and Dynamics Simulation:

- Perform molecular docking (using programs like Glide, GOLD, or AutoDock) to refine the binding pose of the hits within the target's active site and estimate binding affinity [29] [15] [2].

- Conduct Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations (e.g., for 50-100 ns using Desmond or GROMACS) to assess the stability of the protein-ligand complex. Analyze parameters like Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD), Root-Mean-Square Fluctuation (RMSF), Radius of Gyration (Rg), and hydrogen bonding patterns [15] [2] [31].

- Use methods like MM/GBSA (Molecular Mechanics/Generalized Born Surface Area) to calculate the binding free energy (ΔG) of the complex [15].

Table 2: Key Software Tools for Pharmacophore-Based Screening

| Software/Tool | Primary Function | Application Example | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| LigandScout | Structure-based & ligand-based pharmacophore modeling | Generating models from PDB complexes | [29] |

| Schrödinger Phase | Pharmacophore modeling, 3D-QSAR, virtual screening | Virtual screening of BACE1 inhibitors | [15] |

| ZINCPharmer | Online pharmacophore-based screening of ZINC database | Screening alkaloids and flavonoids for MAO-B inhibition | [27] |

| PharmaGist | Online ligand-based pharmacophore alignment | Aligning active molecules to create a common hypothesis | [27] |

| Pharmit | Interactive online pharmacophore screening | Screening for BBB-permeable neurotherapeutics | [1] |

| PyRx | Virtual screening and molecular docking | Screening fungal metabolites against multiple AD targets | [2] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Pharmacophore-Based Screening

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function and Utility | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target Protein Structures | RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Source of 3D structural data for structure-based modeling | [7] [15] |

| Compound Libraries | ZINC15, Vitas-M Laboratory, PubChem, CMNP (Marine Natural Products) | Large-scale collections of purchasable or natural compounds for virtual screening | [1] [15] [32] |

| Pharmacophore Modeling Software | Schrödinger Suite (Phase), MOE (Molecular Operating Environment), LigandScout | Platforms for building, visualizing, and validating structure-based and ligand-based pharmacophore models | [7] [29] [15] |

| Virtual Screening Platforms | Catalyst, ZINCPharmer, Pharmit, PyRx | Tools for performing high-throughput 3D database searches using pharmacophore queries | [29] [1] [27] |

| ADMET Prediction Tools | QikProp, SwissADME, ADMETlab 2.0, pkCSM | Prediction of pharmacokinetic, toxicity, and drug-likeness properties for hit prioritization | [15] [27] [2] |

| Molecular Dynamics Suites | Desmond (Schrödinger), GROMACS | Simulation of protein-ligand complexes to assess binding stability and dynamics over time | [15] [2] [31] |

Application in Neurodegenerative Disease Research

The following diagram illustrates key targets and strategies for Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease, highlighting the multi-target approach:

Case Studies in Alzheimer's Disease

- Targeting BACE-1: Pharmacophore-based virtual screening has been successfully applied to identify novel inhibitors of Beta-secretase 1 (BACE-1), a key enzyme in the amyloidogenic pathway of AD. For instance, screening of 200,000 compounds from the Vitas-M Laboratory database led to the identification of ligand 66H, which demonstrated stable binding in molecular dynamics simulations and favorable binding free energy calculations, highlighting its potential as a lead compound [15].

- Multi-Target Screening for AD: A study screened a library of 17,544 fungal metabolites against three AD targets (GSK-3β, NMDA receptor, and BACE-1). Pharmacophore-based screening filtered 14 best hits, with Bisacremine-C emerging as the most promising multi-target inhibitor. It showed significantly higher binding affinity than native ligands for all three targets and formed stable complexes in MD simulations, as confirmed by parameters like RMSD, RMSF, Rg, and SASA [2].

Case Studies in Parkinson's Disease

- Inhibition of MAO-B: The search for new inhibitors of Monoamine Oxidase B (MAO-B), a key target in PD, has leveraged pharmacophore screening on natural products. A virtual screening of alkaloids and flavonoids, followed by ADMET and docking analysis, identified palmatine and genistein as promising candidates with potential inhibitory activity against MAO-B, suggesting their potential for further development as antiparkinsonian agents [27].

Pharmacophore-based virtual screening represents a rational and powerful strategy for addressing the formidable challenges of CNS drug discovery. Its ability to abstract molecular recognition into essential functional features enables the efficient identification of novel, scaffold-diverse lead compounds from vast chemical libraries. The integration of this approach with robust protocols for ADMET prediction, molecular docking, and dynamics simulation creates a comprehensive framework for prioritizing candidates with a high probability of success. Furthermore, its inherent suitability for designing multi-target directed ligands aligns perfectly with the complex pathophysiology of neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer's and Parkinson's. As computational power and methodologies continue to advance, pharmacophore-based screening will undoubtedly remain a cornerstone in the ongoing effort to develop effective therapeutics for disorders of the central nervous system.

Building and Executing a PBVS Protocol: A Step-by-Step Guide

Pharmacophore modeling is a foundational technique in computer-aided drug design, defined as the ensemble of steric and electronic features necessary to ensure optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target and to trigger (or block) its biological response [33]. In the context of neurodegenerative disease research, where targets often include GPCRs, enzymes like MAO-B, and other neuronal proteins, pharmacophore models provide a powerful approach for virtual screening when experimental structures may be limited [34] [1]. These models abstract critical chemical interactions into features including hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, aromatic rings, hydrophobic regions, and charged centers, providing a concise representation of binding requirements that enables identification of novel therapeutic candidates through virtual screening [24] [33].

The generation of pharmacophore models primarily follows two distinct methodologies: structure-based approaches that utilize protein-ligand complex information, and ligand-based approaches that derive common features from sets of known active compounds [33]. This application note details established protocols for both methodologies, emphasizing their application to neurodegenerative disease targets, with specific case studies relevant to Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease research. The selection between these approaches depends largely on available structural and ligand data, with structure-based methods requiring known protein structures and ligand-based methods depending on collections of confirmed active compounds.

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

Structure-based pharmacophore modeling derives features directly from analysis of three-dimensional protein-ligand complexes, capturing essential interaction patterns observed in crystallographic or modeled structures [33]. This approach is particularly valuable for neurodegenerative disease targets where limited chemical starting points are available, as it identifies interaction features directly from the binding site architecture.

Protocol: Structure-Based Pharmacophore Generation for GPCR Targets

Background: G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) represent important targets for neurodegenerative diseases but often lack extensive ligand libraries or high-resolution structures. The following protocol utilizes fragment-based sampling to generate high-performing pharmacophore models, even with modeled receptor structures [34].

Step 1: Target Structure Preparation

- Obtain experimentally determined or homology-modeled GPCR structure.

- Prepare protein structure: add hydrogen atoms, assign partial charges, and define binding site region.

- For homology models, validate structure quality using geometric verification tools.

Step 2: Fragment Placement with MCSS

- Perform Multiple Copy Simultaneous Search (MCSS) to place functional groups in the binding site.

- Use diverse fragment library representing key pharmacophoric elements.

- Energy-minimize placed fragments to optimize interactions with the protein.

Step 3: Feature Extraction and Model Generation

- Map optimal fragment positions to pharmacophore features: hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic areas, aromatic rings, and charged centers.

- Define spatial constraints and tolerances based on fragment distribution.

- Generate multiple candidate pharmacophore models scoring interaction compatibility.

Step 4: Model Selection via Machine Learning

- Apply cluster-then-predict machine learning workflow to classify model performance.

- Select models with highest enrichment factors using known active ligands as benchmarks.

- Validate model robustness against decoy sets containing inactive compounds.

Application Note: This protocol has been successfully applied to 13 class A GPCR targets, resulting in pharmacophore models with high enrichment factors when screening databases containing 569 known class A GPCR ligands. The machine learning classifier achieved positive predictive values of 0.88 for experimentally determined structures and 0.76 for modeled structures [34].

Protocol: Consensus Pharmacophore Generation with ConPhar

Background: For targets with extensive structural data, consensus pharmacophore modeling integrates features from multiple ligand-bound complexes to create robust models with reduced bias. This approach is particularly valuable for well-studied neurodegenerative disease targets like MAO-B [35] [36].

Step 1: Complex Preparation and Alignment

- Curate set of protein-ligand complex structures (e.g., from PDB) for the target.

- Align all complexes using structural superposition tools like PyMOL [36].

- Extract each aligned ligand conformer and save in SDF format.

Step 2: Individual Pharmacophore Generation

- Upload each ligand structure to Pharmit or similar pharmacophore generation tool [36].

- Generate pharmacophore features for each ligand-protein complex.

- Export individual pharmacophore models in JSON format.

Step 3: Feature Clustering and Consensus Building

- Install ConPhar package in Python environment.

- Load all individual pharmacophore JSON files.

- Parse and consolidate pharmacophoric features into a unified DataFrame.

- Cluster similar features across multiple complexes based on type and spatial location.

- Generate consensus model representing most conserved interaction patterns.

Step 4: Model Refinement and Validation

- Refine feature distances and tolerances based on clustering results.

- Validate model against known active and inactive compounds.

- Export final consensus pharmacophore for virtual screening applications.

Application Note: Applied to SARS-CoV-2 Mpro using 100 non-covalent inhibitor complexes, this protocol successfully captured key interaction features in the catalytic region and enabled identification of novel potential ligands [36]. The methodology is directly transferable to neurodegenerative disease targets with sufficient structural data.

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

Ligand-based pharmacophore modeling identifies common chemical features from a set of known active ligands when the protein structure is unavailable. This approach is widely used in neurodegenerative disease research for targets like monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B) where multiple active compounds are known [27] [33].

Protocol: Ensemble Pharmacophore Generation for Neurodegenerative Disease Targets

Background: This protocol generates an ensemble pharmacophore from multiple known active ligands, capturing essential features shared across chemically diverse compounds with activity against neurodegenerative disease targets [33].

Step 1: Ligand Set Curation and Preparation

- Compile known active ligands from literature or databases (e.g., ChEMBL, PubChem).

- For Parkinson's disease MAO-B inhibitors, this may include alkaloids and flavonoids with demonstrated activity [27].

- Optimize ligand geometries using molecular mechanics (e.g., RM1 method) and correct partial charges.

Step 2: Molecular Alignment and Feature Extraction

- Align all ligand structures using flexible superposition methods.

- Submit aligned molecules to PharmaGist server or similar tool for common feature identification.

- Configure feature weights: aromatic ring = 3.0; hydrophobic = 3.0; hydrogen bond donor/acceptor = 1.5; charge = 1.0 [27].

- Extract pharmacophore features and their 3D coordinates for each ligand.

Step 3: Feature Clustering and Ensemble Pharmacophore Building

- Collect coordinates of each feature type (donors, acceptors, hydrophobic) across all ligands.

- Apply k-means clustering to group similar features in 3D space.

- Select cluster centroids representing most conserved feature positions.

- Define ensemble pharmacophore using selected cluster coordinates.

Step 4: Model Validation and Virtual Screening

Application Note: This approach successfully identified MAO-B inhibitors from alkaloid and flavonoid classes, with palmatine and genistein showing superior performance in subsequent docking studies and pharmacological profiling [27]. The method is particularly valuable for exploring natural products for neurodegenerative diseases.

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Pharmacophore Modeling

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmit [36] | Web Server | Pharmacophore feature generation and virtual screening | Generates pharmacophore JSON files from ligand structures; used in consensus modeling |

| ConPhar [36] | Python Package | Consensus pharmacophore generation | Clusters features from multiple complexes; open-source tool |

| MCSS [34] | Computational Method | Multiple Copy Simultaneous Search | Places functional fragments in binding sites for structure-based pharmacophores |

| PharmaGist [27] | Web Server | Ligand-based pharmacophore alignment | Identifies common features from multiple active ligands |

| ZINCPharmer [27] | Web Server | Pharmacophore-based screening | Screens compound databases using pharmacophore queries |

| PyMOL [36] | Software | Molecular visualization and analysis | Aligns protein-ligand complexes for structure-based approaches |

| RDKit [33] | Cheminformatics Library | Molecular processing and feature detection | Extracts pharmacophore features and handles molecular formats |

| ChemDes [1] | Web Platform | Molecular descriptor calculation | Computes descriptors for BBB permeability and CNS activity prediction |

Workflow Visualization

Workflow for Structure-Based and Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Generation

Advanced Applications in Neurodegenerative Disease Research

Blood-Brain Barrier Permeability Considerations

For neurodegenerative disease targets, effective therapeutics must cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB). Integrative protocols combining pharmacophore modeling with BBB permeability prediction are essential [1]. Screening pipelines should incorporate:

- Computational BBB permeability models using molecular descriptors from tools like ChemDes [1].

- CNS activity prediction based on brain-to-blood ratio calculations.

- ADME profiling to assess drug-likeness for CNS targets.

Application of this integrated approach to 2,127 small molecules identified 582 BBB-permeable compounds, with 112 showing optimal CNS activity and pharmacokinetic properties for neurodegenerative disease applications [1].

AI-Enhanced Pharmacophore Methods

Recent advances in artificial intelligence are transforming pharmacophore modeling for neurodegenerative disease research:

- DiffPhore: A knowledge-guided diffusion framework for 3D ligand-pharmacophore mapping that outperforms traditional methods in predicting binding conformations and virtual screening [24].

- TransPharmer: A generative model integrating pharmacophore fingerprints with GPT-based architecture for de novo molecule generation, successfully applied to identify novel PLK1 inhibitors with submicromolar activity [37].

- Pharmacophore-guided generative design: Frameworks that balance pharmacophore similarity to reference compounds with structural diversity, demonstrating strong potential for generating novel bioactive scaffolds for complex targets [38].

These AI-enhanced methods represent the next generation of pharmacophore-based approaches, particularly valuable for addressing challenging neurodegenerative disease targets with limited traditional chemical starting points.

Structure-based and ligand-based pharmacophore modeling provide complementary approaches for initiating virtual screening campaigns against neurodegenerative disease targets. The protocols detailed in this application note offer robust methodologies for generating high-quality pharmacophore models, with specific considerations for CNS drug discovery. The integration of these approaches with BBB permeability prediction and emerging AI technologies creates powerful frameworks for identifying novel therapeutic candidates for Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, and other neurodegenerative conditions. As computational methods continue to advance, pharmacophore modeling remains an essential component of the rational drug design toolkit for neurodegenerative disease research.

The success of any virtual screening (VS) campaign is fundamentally dependent on the quality and composition of the initial compound library. [29] This section details the protocols for curating databases and preparing a specialized compound library for pharmacophore-based virtual screening (PBVS) targeting neurodegenerative diseases. A well-prepared library, characterized by appropriate molecular complexity, diversity, and drug-like properties, significantly enhances the probability of identifying novel, developable hit compounds. [39] [40] The procedures outlined below are adapted from established computational drug discovery workflows and have been successfully applied in recent research to identify multi-target agents for conditions like Alzheimer's disease. [40] [2]

Database Selection and Acquisition

The first step involves selecting and acquiring high-quality, chemically diverse databases. Both commercial and public databases can be utilized, with a growing emphasis on natural product libraries due to their structural complexity and novelty. [39] [40]

Table 1: Representative Databases for Library Construction

| Database Name | Type | Key Features | Relevance to Neurodegenerative Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) [39] | Natural Product | Contains compounds from Chinese medicinal plants. | High structural diversity; source of neuroactive compounds. |

| AfroDb [39] | Natural Product | African Medicinal Plants database. | Unexplored chemical space; potential for novel scaffolds. |

| NuBBE [39] | Natural Product | Nuclei of Bioassays, Biosynthesis, and Ecophysiology of Natural Products. | Biologically validated and diverse South American natural products. |

| UEFS [39] | Natural Product | Universidade Estadual de Feira de Santana database. | Complementary chemical space from Brazilian biodiversity. |

| PubChem [40] [2] | Public Repository | Massive collection of bioactive molecules and metabolites. | Source for specialized libraries (e.g., fungal metabolites); over 17,000 compounds screened in recent studies. [40] |

| Fungal Metabolites [40] [2] | Specialized Natural Product | Library of compounds derived from fungi. | A source of promising multi-target inhibitors for AD, such as Bisacremine-C. [40] |

Compound Processing and Fragmentation

To access a wider range of chemical space, particularly for fragment-based drug design (FBDD), selected compounds can be subjected to in silico fragmentation.

Protocol: Retrosynthetic Combinatorial Analysis Procedure (RECAP)

The RECAP technique is a standard method for generating fragment libraries by cleaving bonds based on chemically sensible rules. [39]

- Objective: To deconstruct large, complex molecules (like natural products) into smaller, synthetically accessible fragments while retaining key functional groups.

Method:

- Input: Prepare a database of parent compounds (e.g., from Table 1) in a suitable molecular file format (e.g., SDF).

- Cleavage: Apply RECAP rules, which cleave bonds adjacent to specific chemical functionalities (e.g., amide, ester, ether linkages). [39]

- Generation of Fragment Types:

- Extensive (Leaf) Fragments: Exhaustive cleavage to generate the smallest possible fragments. This approach can lead to simpler, but sometimes overly repetitive, chemical entities. [39]

- Non-Extensive (Non-Leaf) Fragments: Systematic cleavage that generates all possible "intermediate" scaffolds. This method produces larger, more complex fragments that cover a broader and less repetitive chemical space. [39]

- Output: Two separate fragment libraries: one containing extensive NPDFs and the other containing non-extensive NPDFs.

Application Note: Research has demonstrated that non-extensive fragmentation of natural products yields fragments with higher pharmacophore fit scores, greater diversity, and better developability potential compared to both their extensively fragmented counterparts and the original parent compounds. [39]

Library Filtering and Preparation for Screening

The raw or fragmented compound collection must be filtered and processed to create a screening-ready library.

Protocol: Drug-Likeness and Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB) Penetration Filtering

This protocol is critical for neurodegenerative disease targets, where compounds often need to reach the central nervous system. [40]

- Objective: To filter out compounds with undesirable properties and enrich the library for molecules capable of crossing the BBB.

Method:

- Standard Drug-Likeness Filters: Apply rules such as Lipinski's Rule of Five to filter the library. Calculate key physicochemical properties:

- Molecular Weight (MW): Typically < 500 Da for drug-like molecules.

- Lipophilicity (LogP): Typically < 5.

- Hydrogen Bond Donors (HBD): ≤ 5.

- Hydrogen Bond Acceptors (HBA): ≤ 10. [40]

- BBB Permeability Prediction: Use computational models (e.g., in software like Schrodinger's QikProp or open-source tools) to predict passive blood-brain barrier penetration. Retain compounds predicted to be BBB-positive. [40]

- Structural Filtering: Remove compounds with reactive functional groups or pan-assay interference compounds (PAINS) that can cause false-positive results in biological assays.

- Standard Drug-Likeness Filters: Apply rules such as Lipinski's Rule of Five to filter the library. Calculate key physicochemical properties:

Application Note: In a study screening fungal metabolites for Alzheimer's disease, a drug-likeness and BBB-positive filter was employed, reducing a library of 17,544 compounds to 14 best hits for further investigation. [40]

Protocol: 3D Conformer Generation and Energy Minimization

Pharmacophore screening requires compounds to be in a three-dimensional (3D) format. [41]

- Objective: To generate low-energy 3D conformations for each compound in the filtered library.

- Method:

- Input: The filtered 2D compound library (e.g., in SDF or SMILES format).

- 3D Conversion: Use tools like Open Babel (integrated in platforms like PyRx) or CORINA to generate initial 3D coordinates. [40]