Whole Exome Sequencing in Cancer Research: A Comprehensive Guide from Basics to Clinical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) and its transformative role in modern cancer research and therapeutic development.

Whole Exome Sequencing in Cancer Research: A Comprehensive Guide from Basics to Clinical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) and its transformative role in modern cancer research and therapeutic development. It covers foundational principles, current methodological approaches including automated workflows and kit selection, and practical guidance for troubleshooting and optimizing WES experiments. The content critically examines WES performance through validation studies and comparative analyses with alternative genomic profiling methods, highlighting its economic and clinical benefits in identifying actionable alterations and guiding targeted therapies. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this resource synthesizes the latest technological advancements and evidence-based applications to inform research design and clinical implementation strategies.

The Foundational Role of WES in Decoding Cancer Genomics

Whole exome sequencing (WES) represents a powerful methodological approach in cancer genomics, enabling comprehensive analysis of protein-coding regions to identify somatic mutations driving oncogenesis. This technical guide elucidates the core principles defining WES as "whole" through its capacity to interrogate all ~20,000 genes in a single assay, distinguishing it from targeted panels and whole-genome sequencing. We detail experimental protocols for variant calling, discuss the pivotal role of WES in identifying therapeutic targets and biomarkers like tumor mutation burden (TMB), and provide structured quantitative comparisons of sequencing methodologies. Within precision oncology frameworks, WES facilitates drug repurposing opportunities by revealing shared biomarkers across tumor types and contributes substantially to biomarker discovery in rare cancers. This work provides researchers with comprehensive methodological guidance and contextualizes WES within the evolving landscape of cancer genomics research.

The term "whole" in whole exome sequencing signifies the systematic attempt to capture and sequence all protein-coding regions of the genome, representing approximately 1-2% of the human genome yet containing an estimated 85% of known disease-causing variants [1]. This comprehensive approach distinguishes WES from targeted gene panels that investigate predetermined gene sets and from whole-genome sequencing (WGS) that encompasses both coding and non-coding regions. The fundamental premise underpinning WES in cancer research is that the exome harbors the majority of somatic mutations with direct functional consequences on protein structure and function, thereby driving tumorigenesis and offering potential therapeutic targets [2] [3].

The strategic importance of WES in cancer research stems from its balanced approach to genomic interrogation. While WGS provides a more complete genomic profile, WES offers superior cost-effectiveness and data manageability, enabling larger sample sizes for robust statistical analysis in cohort studies [4]. The methodological "wholeness" of WES manifests through several technical characteristics: its unbiased nature (interrogating all exons without prior hypothesis about specific genes), standardized target regions (using consistent capture kits across samples), and completeness of coverage (attempting to sequence all exonic regions despite technical challenges) [2] [1]. This systematic approach has positioned WES as a cornerstone technology in major cancer genomics initiatives, including The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), where it has helped characterize the mutational landscapes of numerous cancer types [5].

Technical Foundations of Whole Exome Sequencing

Core Principles and Workflow

The principle of WES centers on the selective capture and high-throughput sequencing of exonic regions from fragmented genomic DNA [1]. This process leverages the fundamental biological understanding that while exons constitute a small minority of the genome, they harbor the majority of clinically actionable mutations, making them particularly informative for cancer research [3]. The technical workflow follows a standardized series of steps that ensure comprehensive exome coverage while minimizing artifacts and biases.

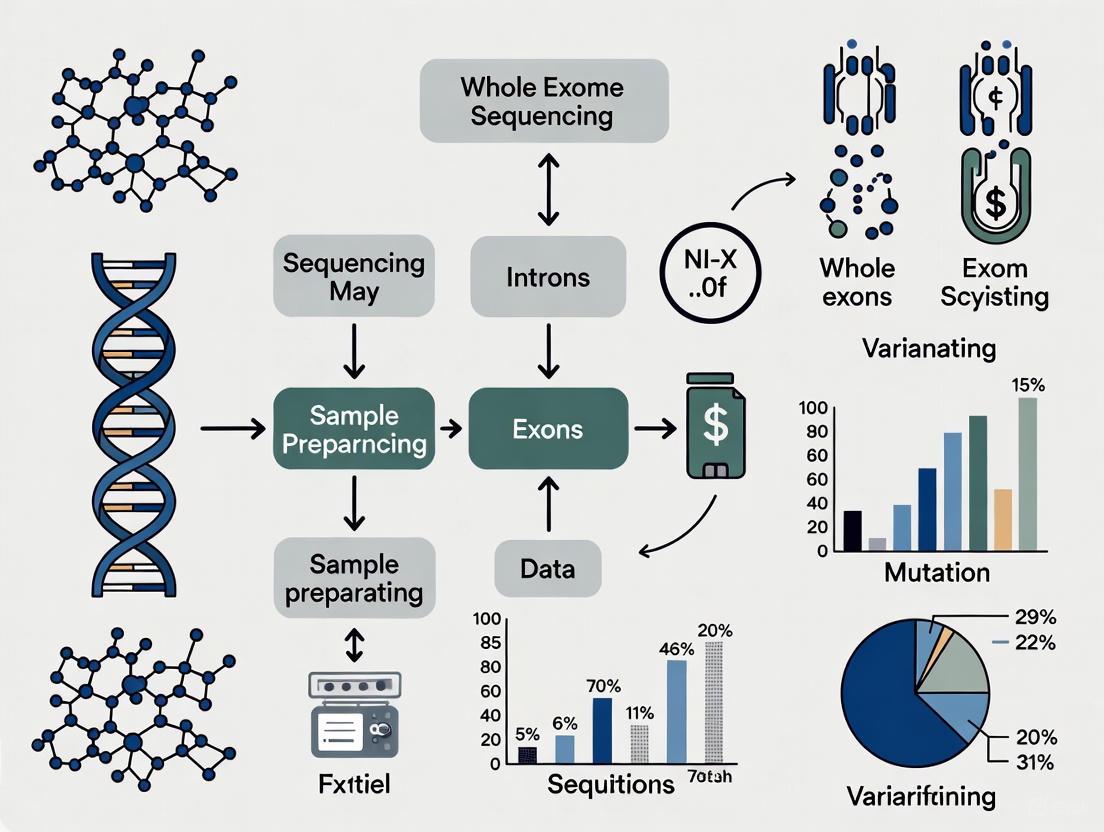

The following diagram illustrates the complete WES workflow from sample preparation through data analysis:

Experimental Protocol Details

Sample Preparation and Library Construction

The initial phase requires high-quality DNA isolated from matched tumor and normal tissues. Tumor samples should contain sufficient malignant cells (typically >70% tumor purity) to confidently call somatic variants, while normal samples (usually blood, saliva, or adjacent normal tissue) serve as germline controls [2]. DNA quality assessment via fluorometry or spectrophotometry is critical, with degradation particularly problematic in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) specimens [2]. Following extraction, DNA undergoes fragmentation (via sonication or enzymatic methods) to sizes of 150-200bp, followed by end repair, adenylation, and adapter ligation to create sequencing libraries compatible with platforms like Illumina [1].

Exome Enrichment Methods

The defining step of WES utilizes hybridization capture to isolate exonic regions from the genomic DNA library. The most common approach employs biotinylated probes (e.g., Twist Bioscience Human Core Exome Kit, Illumina TruSeq DNA Exome) that specifically bind to exonic regions [6] [1]. Key technical considerations include:

- Probe Design: Modern kits target 30-60 megabases encompassing exons, UTRs, and select non-coding RNAs

- Hybridization Conditions: Temperature and timing optimization to maximize on-target specificity

- Capture Method: Solution-based hybridization outperforms array-based methods for efficiency and uniformity [2]

The hybridized fragments are isolated using streptavidin-coated magnetic beads, while non-targeted regions are washed away. Captured DNA is then amplified via PCR to generate sufficient material for sequencing [1].

Sequencing and Data Analysis

Enriched libraries undergo massively parallel sequencing on platforms such as Illumina NovaSeq with typical read lengths of 100-150bp paired-end to ensure adequate coverage of exonic regions [7] [1]. Sequencing depth of 100-200x is recommended for tumor samples to detect subclonal populations, while germline controls typically require 30-50x coverage [2].

Bioinformatic processing involves:

- Quality Control: FastQC for sequence quality metrics

- Alignment: BWA-MEM or similar aligners to reference genome (GRCh37/hg19 or GRCh38/hg38)

- Variant Calling: Multiple algorithms for detecting different variant types (Table 1)

- Annotation: Tools like SNPeff or VEP for predicting functional consequences [7] [2]

Table 1: Common Variant Callers for Somatic Mutation Detection in Cancer WES

| Variant Type | Tool Options | Key Features | Performance Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| SNVs/Indels | MuTect2, VarScan2, Strelka | High sensitivity for low-frequency variants, contamination correction | Strelka performs well with high-coverage data; MuTect2 excels in low-frequency detection [2] |

| Copy Number Variations | ASCAT, Sequenza | Account for tumor purity, ploidy | Require sufficient coverage depth; challenging with WES due to uneven coverage [2] |

| Structural Variants | Delly, Manta | Detect translocations, inversions | Limited sensitivity with WES data; WGS preferred [8] |

WES in Cancer Research: Key Applications and Methodological Comparisons

Therapeutic Target Discovery and Biomarker Identification

WES enables systematic identification of somatic mutations across cancer types, revealing both common driver mutations and rare subtype-specific alterations. In hypopharyngeal cancer, WES of 10 patients identified 8,113 mutation sites across 5,326 genes, with 72 pathogenic mutations in 53 genes following ACMG guidelines [9]. Notably, KMT2C showed mutations in all 10 patients, while TTN, ANK3, and TP53 demonstrated high mutation frequencies consistent with TCGA data [9]. Functional annotation and pathway enrichment analyses of WES data can prioritize mutations for therapeutic development, as demonstrated by the discovery of RBM20 as a potential driver in hypopharyngeal cancer with prognostic significance [9].

WES further facilitates drug repurposing opportunities by identifying shared therapeutic biomarkers across histologically distinct cancers. Research analyzing 726 tumors across 10 cancer types revealed that "treatment biomarkers are shared across solid tumours, highlighting repurposing opportunities" [7]. For instance, BRCA1/2 mutations detected via WES can indicate PARP inhibitor sensitivity across multiple tumor types, while high tumor mutation burden (TMB) may predict immunotherapy response regardless of tissue of origin [10].

Comparison with Alternative Sequencing Approaches

The strategic selection of genomic profiling methods depends on research objectives, resources, and specific biological questions. The following table quantitatively compares WES with alternative approaches:

Table 2: Sequencing Platform Comparisons in Cancer Genomics

| Parameter | Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) | Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) | Comprehensive Gene Panel |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomic Coverage | 1-2% (30-60 Mb) | 100% (~3,000 Mb) | 0.002-2.6 Mb (targeted genes) [7] |

| Variant Detection Scope | Coding SNVs/indels; limited CNVs | All variant types including structural variants, non-coding | Targeted SNVs/indels, CNVs, fusions (panel-dependent) |

| Cost per Sample | $$ | $$$$ | $ |

| Data Volume | ~5-10 GB | ~90-100 GB | ~0.5-2 GB |

| TMB Calculation | Well-correlated with WGS but absolute values differ [7] | Gold standard | Possible but requires careful normalization [7] |

| Therapeutic Applications | Identifies ~90% of known drug targets; detects trial biomarkers [7] | Maximum biomarker discovery including non-coding | Identifies majority of approved actionable mutations [7] |

Recent direct comparisons demonstrate that WES/WGS identifies approximately 30% more therapy recommendations than large panels (median 3.5 vs. 2.5 per patient), with one-third of WES/WGS recommendations relying on biomarkers not covered by panels [10]. These additional biomarkers include mutational signatures, complex structural variants, and non-canonical fusion genes [10].

Tumor Mutation Burden and Microsatellite Instability Assessment

WES enables calculation of tumor mutation burden (TMB), defined as the total number of mutations per megabase of genome sequenced. TMB estimation varies significantly between sequencing platforms, with WES-based TMB requiring careful normalization against targeted panels [7]. Methodological considerations include:

- Mutation Inclusion: Whether to consider all mutations or only non-synonymous mutations

- Coverage Uniformity: WES capture efficiency impacts TMB accuracy

- Threshold Determination: TMB cutoffs for "high" burden are platform-specific [7]

WES also facilitates microsatellite instability (MSI) detection through tools like MSIsensor, which analyzes microsatellite regions within exonic sequences [7]. However, MSI detection sensitivity depends on the number of microsatellites captured, with WGS typically providing more comprehensive assessment than WES.

Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Cancer WES

| Category | Specific Examples | Application in WES Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Exome Capture Kits | Twist Bioscience Human Core Exome, Illumina TruSeq DNA Exome | Target enrichment of exonic regions through hybridization capture [6] |

| Library Prep Kits | Illumina DNA Prep, KAPA HyperPrep | Fragmentation, end repair, adapter ligation, and PCR amplification [3] |

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina NovaSeq 6000, Illumina HiSeq | High-throughput sequencing with paired-end reads [7] |

| Alignment Tools | BWA-MEM, Bowtie2 | Mapping sequenced reads to reference genome [7] [2] |

| Variant Callers | MuTect2 (SNVs), VarScan2 (SNVs/indels), ASCAT (CNVs) | Detecting somatic mutations from aligned BAM files [7] [2] |

| Annotation Tools | SNPeff, Variant Effect Predictor (VEP) | Predicting functional consequences of identified variants [7] [2] |

| Analysis Platforms | Galaxy, GATK | Comprehensive analysis pipelines for variant discovery [2] |

Technical Limitations and Complementary Approaches

Despite its utility, WES presents several technical limitations that researchers must acknowledge. Incomplete exome coverage results from capture inefficiencies, with some exonic regions consistently under-represented due to high GC content or repetitive sequences [8]. Detection of structural variants (including copy number variations, translocations, and inversions) remains challenging with WES data due to uneven coverage and the location of breakpoints outside captured regions [8]. Additionally, WES completely misses non-coding regulatory elements that may influence gene expression and cancer pathogenesis, such as promoters, enhancers, and non-coding RNAs [5] [8].

These limitations necessitate complementary approaches in comprehensive cancer genomics studies. RNA sequencing identifies expressed mutations, gene fusions, and aberrant splicing events missed by WES [10]. Whole genome sequencing provides complete genomic characterization, including non-coding drivers and complex structural variants [5]. Targeted panels offer ultra-deep sequencing for detecting low-frequency subclonal populations in minimal residual disease monitoring [7].

The following diagram illustrates the variant detection landscape across sequencing platforms:

Whole exome sequencing remains a cornerstone technology in cancer genomics, offering a balanced approach between comprehensive genomic assessment and practical research constraints. The "wholeness" of WES derives from its systematic interrogation of all protein-coding regions, enabling discovery of driver mutations, therapeutic biomarkers, and molecular cancer subtypes across diverse malignancies. As sequencing technologies evolve and computational methods improve, WES continues to provide critical insights into cancer biology while complementing emerging approaches like whole genome and transcriptome sequencing. For cancer researchers designing genomic studies, WES represents an efficient primary discovery tool when focused on coding regions, with subsequent targeted validation or expanded genomic characterization as needed. The ongoing integration of WES data with functional genomics and clinical outcomes will further advance precision oncology approaches across the cancer spectrum.

In the landscape of precision oncology, the choice of genomic profiling technology is pivotal, balancing comprehensiveness with practical clinical and research constraints. Whole exome sequencing (WES) has emerged as a powerful solution that strategically targets the protein-coding regions of the genome, where an estimated 85% of disease-causing mutations reside. This focused approach provides researchers and clinicians with a methodologically efficient and economically viable pathway to actionable genomic insights. While whole genome sequencing (WGS) offers a broader view of the entire genome, including non-coding regions, WES delivers targeted depth at a significantly reduced cost and computational burden, making it particularly suitable for large-scale cancer studies where budget and bioinformatics resources are limiting factors. The strategic application of WES enables comprehensive tumor profiling, identification of hereditary cancer syndromes, and discovery of novel therapeutic targets without the overhead of whole-genome analysis. This technical guide examines the core advantages of WES through the dual lenses of cost-effectiveness and targeted biological insight, providing the scientific community with a validated framework for its implementation in cancer research and drug development.

Economic Advantages: A Detailed Cost-Benefit Analysis

Comprehensive Cost Comparisons Across Sequencing Platforms

The economic argument for WES is substantiated by multiple cost-analyses across different research settings and geographical locations. A systematic review of health economic evidence found that cost estimates for a single test ranged from $555 to $5,169 for WES compared to $1,906 to $24,810 for WGS [11] [12]. This significant price differential makes WES accessible for larger cohort studies within constrained budgets.

Table 1: Cost Analysis of Genomic Sequencing Technologies in Cancer Research (2018-2020)

| Sequencing Technology | Cost Range (US$) | Key Cost Drivers | Proportion of Total Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) | $604 - $1,932 [13] | Library preparation & sequencing materials | 76.8% [13] |

| Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) | $2,006 - $3,347 [13] | Data analysis, storage, and interpretation | Higher than WES due to data volume |

| Targeted Panels | $240 - $297 [13] | Sample extraction and processing | 8.1% [13] |

A detailed micro-costing study conducted in Australia further quantified this differential, reporting per-person costs of AU$871-$2,788 (US$604-1,932) for exome sequencing compared to AU$2,895-$4,830 (US$2,006-3,347) for whole genome sequencing [13]. The study identified that library preparation and sequencing materials constituted the largest proportion (76.8%) of total costs, followed by data analysis (9.2%), sample extraction (8.1%), and data storage (2.6%) [13]. These findings highlight how WES achieves efficiency by minimizing costs in the most expensive phases of sequencing while maintaining focus on clinically relevant genomic regions.

Health Economic and Outcome Benefits in Oncology

Beyond direct sequencing costs, WES demonstrates superior cost-effectiveness through its impact on clinical decision-making and patient outcomes. A 2025 economic modeling study in advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) demonstrated that combining whole exome and whole transcriptome sequencing (WES/WTS) reduced costs by $14,602 per patient compared to sequential single-gene testing while providing minimal survival benefits [14]. When compared with no genomic testing, the WES/WTS approach reduced costs by $8,809 per patient tested while increasing median overall survival by an average of 3.9 months [14].

The economic advantage extends to testing efficiency. Comprehensive genomic profiling via WES identifies more actionable alterations than sequential single-gene approaches, particularly for fusions that require RNA sequencing for detection. The same study showed that tests incorporating both DNA and RNA sequencing increased identification of actionable alterations by 2.3%-13.0% across the range of fusion prevalence while reducing costs by $400-1,724 [14]. This demonstrates how WES-based approaches maximize diagnostic yield per healthcare dollar spent.

Infrastructure and Scalability Economic Benefits

WES generates significantly smaller datasets than WGS (approximately 5 GB vs. 100 GB per sample), resulting in substantial savings in data storage and computational processing [13]. This reduced infrastructure requirement lowers the barrier to entry for individual research laboratories and hospital systems without access to high-performance computing clusters. The efficiency extends to analytical workflows, where the focused nature of exome data accelerates variant identification and interpretation compared to the complex filtering required for whole genome datasets. This computational efficiency translates to faster turnaround times from sample to report, a critical factor in clinical oncology where treatment decisions are time-sensitive. The cumulative effect of these advantages positions WES as the optimal balancing point between comprehensiveness and practical implementability in both research and clinical settings.

Technical and Biological Advantages in Cancer Research

Enhanced Detection of Clinically Actionable Variants

The targeted nature of WES enables deeper sequencing coverage (typically 100x-200x) of exonic regions compared to the 30x-60x coverage typical of WGS in clinical practice. This enhanced depth improves detection of somatic mutations with low variant allele frequency due to tumor heterogeneity or stromal contamination. A 2025 study implementing exome-based cancer predisposition gene testing demonstrated a 9.7% diagnostic yield in individuals with multiple primary tumors, identifying pathogenic variants in cancer-associated genes including CHEK2, FANCM, NF1, POT1, and PTEN [15]. An additional 4.2% of individuals carried candidate variants in genes such as HOXB13, MAX, and RECQL4 [15]. This demonstrates the capability of WES to identify clinically relevant mutations across a broad spectrum of cancer types without prior hypothesis about specific genes.

The comprehensive nature of WES is particularly valuable for cancers with heterogeneous molecular profiles or when patients present with atypical tumor spectra that don't align with established hereditary cancer syndromes. By analyzing all ~20,000 protein-coding genes simultaneously, WES eliminates the need for iterative single-gene testing that characterized traditional genetic diagnostics. The technology successfully identifies mutations in genes not typically associated with a patient's specific cancer type, expanding understanding of genotype-phenotype correlations and revealing novel therapeutic targets [15].

Integration with Functional Genomics and Transcriptomics

Modern WES workflows increasingly incorporate complementary genomic analyses that enhance functional interpretation. The combination of WES with whole transcriptome sequencing (WTS) provides a more complete molecular portrait by connecting genomic alterations with their functional consequences at the RNA level. This integrated approach is particularly powerful for detecting gene fusions, alternative splicing events, and expression outliers that may not be evident from DNA sequencing alone [14]. The addition of transcriptomic data helps prioritize mutations of functional significance among the numerous variants identified in exome sequencing, accelerating the transition from genomic discovery to biological validation.

The focused data generation of WES also facilitates more streamlined integration with epigenetic profiling and proteomic data. Unlike the massive datasets from WGS that require extensive preprocessing, WES data can be more readily correlated with DNA methylation arrays, chromatin accessibility maps, and protein expression patterns to build multi-omics models of tumor behavior. This integrative capability positions WES as a cornerstone technology in systems biology approaches to cancer research, where understanding the functional interplay between different molecular layers is essential for deciphering complex tumor phenotypes and therapeutic resistance mechanisms.

Experimental Design and Methodological Protocols

Standardized WES Wet-Lab Workflow

The reproducibility of WES depends on strict adherence to standardized laboratory protocols. The following workflow outlines the key steps for generating high-quality exome sequencing data from tumor and matched normal samples:

Sample Preparation and Quality Control

- Extract DNA from fresh frozen or FFPE tumor tissue and matched normal (blood or saliva) using validated kits

- Assess DNA quality via fluorometry (Qubit) and fragment analysis (Bioanalyzer/TapeStation)

- Require minimum DNA quantity: 50-100ng for fresh frozen, 100-200ng for FFPE

- Require minimum DNA quality: DV200 >30% for FFPE samples, A260/A280 ratio of 1.8-2.0

Library Preparation and Target Enrichment

- Fragment DNA to 150-200bp using acoustic shearing (Covaris) or enzymatic fragmentation

- Repair DNA ends, add A-overhangs, and ligate with platform-specific adaptors

- Amplify libraries with 4-8 PCR cycles using high-fidelity polymerase

- Perform exome capture using commercial systems (e.g., Agilent SureSelect, Illumina Nextera)

- Hybridize libraries with biotinylated RNA baits covering exonic regions for 16-24 hours

- Capture bait-bound fragments using streptavidin-coated magnetic beads

- Wash to remove non-specifically bound fragments and amplify captured libraries with 8-12 PCR cycles

Sequencing

- Quantify final libraries by qPCR and pool at equimolar ratios

- Sequence on appropriate NGS platform (Illumina NovaSeq, Complete Genomics DNBSEQ-T1+, etc.)

- Target minimum coverage of 100x for tumor and normal samples

- Use paired-end sequencing (2x100bp or 2x150bp) for optimal variant calling

Bioinformatics Analysis Pipeline

The computational analysis of WES data follows a structured workflow from raw sequences to annotated variants:

Variant Prioritization Strategy for Cancer

- Filter against population databases (gnomAD) to remove common polymorphisms (MAF <0.1%)

- Retain protein-truncating variants (nonsense, frameshift, splice-site)

- Prioritize missense variants with high pathogenicity scores (CADD >20, SIFT, PolyPhen)

- Compare tumor vs. normal to identify somatic mutations

- Annotate with cancer-specific databases (COSMIC, OncoKB, CIViC)

- Filter for actionable alterations with therapeutic implications

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Platforms for WES in Oncology

| Product Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Exome Capture Kits | Agilent SureSelect, Illumina Nextera | Target enrichment of exonic regions |

| Library Prep Kits | KAPA HyperPrep, Illumina DNA Prep | NGS library construction |

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina NovaSeq, Complete Genomics DNBSEQ-T1+ | High-throughput sequencing |

| Automation Systems | Hamilton STAR, Agilent Bravo | Laboratory workflow automation |

| Analysis Software | GATK, VarScan, SNPEff | Variant calling and annotation |

The WES research ecosystem includes both established and emerging solutions. Complete Genomics highlights its DNBSEQ-T1+ system for cost-effective, scalable sequencing across applications including whole exome studies [16]. Their partnership with SOPHiA GENETICS integrates comprehensive genomic profiling assays with cloud-based analytics, delivering an end-to-end workflow for precision oncology [16]. Similarly, Illumina's TruSight Oncology Comprehensive provides FDA-approved comprehensive genomic profiling with pan-cancer companion diagnostic claims, evaluating both DNA and RNA to match cancer patients with targeted therapies [17].

Whole exome sequencing represents an optimally balanced approach in cancer genomics, offering substantial economic advantages without compromising the depth of biological insight. The technology delivers comprehensive coverage of clinically relevant genomic regions at approximately one-third to one-half the cost of whole genome sequencing, while generating more manageable datasets that accelerate analytical workflows. The focused nature of WES enables higher sequencing depth for detecting low-frequency variants in heterogeneous tumor samples, and its modularity facilitates integration with transcriptomic and epigenetic profiling. As sequencing technologies continue to evolve and costs decrease, WES maintains its strategic position through parallel advancements in capture efficiency, analytical algorithms, and functional interpretation tools. For the research and clinical communities, WES provides a cost-effective portal into the cancer genome, accelerating both fundamental discovery and translational applications in precision oncology.

Whole-exome sequencing (WES) has emerged as a powerful and cost-effective tool in precision oncology, enabling the comprehensive detection of somatic alterations that drive tumorigenesis. This technical guide details how WES identifies key actionable genomic alterations—including point mutations, insertions/deletions (indels), copy number variations (CNVs), and gene fusions—along with crucial biomarkers such as tumor mutational burden (TMB) and microsatellite instability (MSI). We explore the integration of WES with complementary technologies like RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) to enhance fusion detection and functional validation. Furthermore, we provide detailed experimental protocols and bioinformatic workflows for analyzing sequencing data, alongside a curated toolkit of essential research reagents. By bridging comprehensive genomic profiling with clinically actionable insights, WES facilitates personalized treatment strategies and expands therapeutic options for cancer patients.

Cancer is a genetic disease characterized by the accumulation of somatic alterations that confer growth and survival advantages to tumor cells. "Actionable alterations" are specific genetic changes that can be targeted by approved therapies or implicated in clinical trials. The primary classes of these alterations include single nucleotide variants (SNVs), small insertions and deletions (indels), copy number variations (CNVs), and gene fusions [18]. Beyond these, complex genomic signatures such as high tumor mutational burden (TMB-H) and microsatellite instability (MSI-H) have emerged as tissue-agnostic biomarkers for immunotherapy [19].

Whole-exome sequencing (WES) interrogates the protein-coding regions of the genome, which harbor an estimated ~85% of disease-causing mutations [20]. By focusing on this functionally rich portion, WES provides a balanced approach, offering broader coverage than targeted panels while remaining more cost-effective and analytically tractable than whole-genome sequencing (WGS) [18] [20]. In clinical oncology, WES facilitates a shift from histology-based to genotype-based treatment paradigms, enabling the identification of targetable mutations, elucidation of resistance mechanisms, and discovery of novel therapeutic targets [18] [21].

The Technical Capabilities of WES in Detecting Alterations

WES provides a versatile platform for detecting a wide spectrum of genomic alterations. The table below summarizes its core capabilities in identifying key actionable alterations.

Table 1: Types of Actionable Alterations Detected by WES

| Alteration Type | Detection Capability | Key Examples | Clinical/Research Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Point Mutations (SNVs/Indels) | High sensitivity for somatic and germline variants in exonic regions [18]. | EGFR L858R, BRAF V600E, KRAS G12C [18] [19]. | Direct targets for small-molecule inhibitors (e.g., Osimertinib for EGFR-mutant lung cancer) [22]. |

| Copy Number Variations (CNVs) | Effective detection of focal and arm-level gains/losses [23]. | ERBB2 amplification, PTEN deletion [18] [19]. | Guides use of targeted therapies (e.g., Trastuzumab for HER2-amplified cancers) [19]. |

| Gene Fusions | Possible but challenging; performance depends on coverage and bioinformatic tools [24]. | TMPRSS2-ERG (prostate cancer), PML-RARA (AML) [24] [25]. | Diagnostically and therapeutically relevant; can be targeted by TKIs (e.g., TRK inhibitors) [25]. |

| Genomic Biomarkers | Can be derived from exome-wide mutational patterns [18] [23]. | Tumor Mutational Burden (TMB), Microsatellite Instability (MSI) [18] [19]. | Tissue-agnostic biomarkers predicting response to immune checkpoint inhibitors [19]. |

Complementary Role of RNA-Seq

While WES is powerful for DNA-level alterations, RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) provides critical functional validation and enhances fusion detection. Integrated DNA/RNA sequencing assays have demonstrated superior performance, uncovering actionable alterations in up to 98% of clinical tumor samples [23]. RNA-Seq is particularly valuable for:

- Verifying fusion gene expression: Confirming that a DNA-level rearrangement produces a functional transcript [18] [23].

- Identifying fusions missed by WES: Resolving complex rearrangements or those involving large intronic regions [18] [24].

- Providing gene expression context: Informing on pathway activation and tumor microenvironment [18] [23].

Experimental Workflow for WES in Cancer Research

A robust WES workflow involves meticulous sample preparation, sequencing, and data analysis. The following diagram and protocol detail the key steps.

Figure 1: End-to-end workflow for Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) in cancer research, from sample collection to data interpretation.

Detailed Methodology

Step 1: Sample Collection and Nucleic Acid Isolation

- Sample Types: The process begins with collecting tumor samples, which can be fresh-frozen (FF) or formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE), paired with a matched normal sample (e.g., blood, saliva, or adjacent benign tissue) [21] [26] [23].

- DNA Extraction: Extract genomic DNA using commercial kits (e.g., QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit, AllPrep DNA/RNA Mini Kit). A minimum of 10-200 ng of input DNA is typically required, though recommendations vary by protocol [26] [23].

- Quality Control (QC): Assess DNA quantity and quality using a spectrophotometer (e.g., NanoDrop) and fluorometer (e.g., Qubit). For FFPE DNA, perform a PCR-based QC to confirm amplificability. Ensure tumor purity is sufficient (>10-20% is often a minimum threshold) for reliable somatic variant calling [21] [23].

Step 2: Library Preparation and Exome Capture

- Library Construction: Fragment DNA and ligate sequencing adapters to the ends of the DNA fragments. For WES, this is typically performed using kits such as the SureSelect XT HS2 (Agilent) [23].

- Exome Capture: Use biotinylated oligonucleotide probes (e.g., SureSelect Human All Exon V7) to perform solution-based hybridization and capture the protein-coding exons. This step enriches the library for the ~1-2% of the genome that is exonic [21] [20].

- Library QC: Assess the final captured library's concentration, size distribution, and quality using systems like the TapeStation 4200 (Agilent) or similar [23].

Step 3: Sequencing and Primary Data Analysis

- Sequencing: Load the libraries onto a high-throughput sequencer (e.g., Illumina NovaSeq 6000) for paired-end sequencing (e.g., 2x100 bp or 2x150 bp). A mean coverage of 75x-100x is recommended for confident somatic variant detection, with higher coverage (>75x) particularly beneficial for fusion detection from WES data [24] [21].

- Primary Analysis: Convert raw signal data (base calling) into sequence reads (FASTQ format). Perform initial QC metrics including Q-score (e.g., Q30 > 90%) and pass filter (PF) reads [23].

Bioinformatic Analysis of WES Data

The transformation of raw sequencing data into biologically and clinically meaningful results requires a multi-step bioinformatic pipeline. Key steps include:

- Alignment: Map sequencing reads (FASTQ) to a reference genome (e.g., GRCh37/hg19 or GRCh38/hg38) using aligners like BWA-MEM [26] [23].

- QC and Post-Processing: Remove PCR duplicates, perform local realignment, and recalibrate base quality scores using tools like GATK [26] [23].

- Variant Calling:

- Somatic SNVs/Indels: Use callers like GATK Mutect2 or Strelka2 on the tumor-normal pair to identify somatic point mutations and small insertions/deletions [26] [23].

- Somatic CNVs: Detect copy number alterations from WES data using tools such as GATK AllelicCNV or similar algorithms [26] [23].

- Gene Fusions: Apply specialized tools (e.g., Fuseq-WES) that use discordant reads and split reads from DNA sequencing to predict fusion events [24].

- Annotation and Prioritization: Annotate variants using tools like VEP, cross-referencing with databases (e.g., dbSNP, COSMIC, ClinVar). Filter and prioritize variants based on population frequency, predicted functional impact, and actionability in resources like CIViC or OncoKB [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful WES-based research relies on a suite of validated reagents and computational tools. The following table catalogs essential components for a typical workflow.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for WES Workflows

| Reagent/Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit, AllPrep DNA/RNA Mini Kit (Qiagen) [26] [23]. | Isolate high-quality genomic DNA from diverse sample types. The AllPrep kit allows concurrent isolation of DNA and RNA for integrated analysis. |

| Exome Capture Panels | SureSelect Human All Exon V7 (Agilent) [21] [23]. | Probes designed to hybridize and enrich for exonic regions. Critical for determining the genomic content sequenced. |

| Library Prep Kits | SureSelect XT HS2 (Agilent), TruSeq stranded mRNA kit (Illumina for RNA) [23]. | Prepare sequencing-ready libraries from extracted DNA or RNA. Incorporates adapters and indexes for multiplexing. |

| Alignment & Variant Callers | BWA (alignment), GATK Mutect2/Strelka2 (SNVs/Indels), GATK AllelicCNV (CNVs) [26] [23]. | Core bioinformatic software for transforming raw reads into called variants. Accuracy is paramount for downstream analysis. |

| Variant Annotation | Ensembl VEP, dbSNP, COSMIC, ClinVar [26]. | Databases and tools to add biological and clinical context to called variants, enabling prioritization. |

Signaling Pathways and Therapeutic Targeting

Oncogenic driver alterations identified by WES frequently converge on a core set of signaling pathways that control cell growth, survival, and proliferation. The diagram below illustrates key pathways and how targeted therapies interfere with them.

Figure 2: Core oncogenic signaling pathways (MAPK/ERK and PI3K/AKT/mTOR) targeted by therapies based on WES findings. Dashed lines indicate inhibitory actions.

Actionable mutations identified by WES often activate the MAPK/ERK and PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathways, which are central to cell proliferation and survival [18] [25]. For example:

- EGFR mutations in lung cancer constitutively activate the MAPK pathway, driving uncontrolled growth. TKIs like Osimertinib specifically bind to and inhibit mutant EGFR, blocking downstream signaling [27] [22].

- Gene fusions (e.g., EML4-ALK) function as potent oncogenic drivers, leading to ligand-independent activation of these pathways. Crizotinib targets the ALK fusion protein, inducing tumor regression in eligible patients [25].

Whole-exome sequencing stands as a cornerstone technology in modern cancer research and precision oncology. Its ability to comprehensively profile the coding genome for a wide array of actionable alterations—from simple point mutations to complex biomarkers like TMB—makes it an indispensable tool for discovering therapeutic targets, understanding resistance mechanisms, and guiding treatment decisions. While challenges remain, particularly in the consistent detection of gene fusions, the integration of WES with transcriptomic data and the continuous refinement of bioinformatic pipelines are steadily enhancing its power. As the catalog of actionable alterations grows and sequencing costs decline, WES is poised to become even more deeply embedded in the workflow of drug development and personalized cancer care.

Whole exome sequencing (WES) has emerged as a powerful genomic tool in cancer research and clinical oncology, enabling the analysis of all protein-coding regions in the human genome. This technology represents a strategic balance between comprehensive genomic assessment and cost-effectiveness, targeting the approximately 1-2% of the genome that contains an estimated 85% of known disease-causing variants, including those driving carcinogenesis [2] [28]. The growing adoption of WES is fundamentally transforming cancer research and therapeutic development by providing unprecedented insights into the molecular mechanisms of tumorigenesis, disease progression, and treatment resistance.

The positioning of WES within the broader genomics landscape is characterized by its specific focus on exonic regions, which delivers high-throughput results at a more accessible price point compared to whole genome sequencing (WGS) while offering substantially broader analysis than targeted gene panels [2]. This technical and economic balance has established WES as a pivotal technology in precision oncology, facilitating both research discoveries and clinical applications across the cancer continuum from risk assessment to therapeutic targeting.

Global Market Size and Projections

The whole exome sequencing market has demonstrated remarkable growth momentum, characterized by rapid expansion and significant financial investment. Current market valuations and future projections underscore the technology's accelerating adoption across research and clinical domains.

Table 1: Whole Exome Sequencing Market Size and Growth Projections

| Metric | 2024/2025 Value | 2029/2033 Value | CAGR | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global Market Size | $95.73 billion (2024) [29] | $158.9 billion (2029) [29] | 10.6% [29] | Precision Oncology Market Report |

| WES-Specific Market | $2.43 billion (2024) [30] | $14.02 billion (2033) [30] | 21.5% [30] | Straits Research |

| Alternative WES Projection | - | $3.7 billion growth (2025-2029) [31] | 21.1% [31] | Technavio |

This substantial growth trajectory is fueled by multiple converging factors, including the expanding application of WES in clinical diagnostics, rising demand for personalized cancer therapeutics, and continuous technological improvements that enhance both the capabilities and accessibility of genomic sequencing.

Comparative Genomic Technology Markets

The positioning of WES within the broader genomic sequencing landscape reveals its strategic role in balancing comprehensiveness with practical constraints. When compared to other sequencing approaches, WES occupies a distinctive niche that explains its growing adoption.

Table 2: Comparative Genomic Sequencing Technologies in Cancer

| Technology | Genomic Coverage | Key Advantages | Primary Applications in Cancer | Market Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) | Protein-coding regions (~1-2% of genome) [28] | Cost-effective; focused on clinically actionable regions; higher depth for price [2] [30] | Tumor mutational burden; driver mutation identification; therapy selection [2] [32] | 21.5% CAGR (2024-2033); rapid clinical adoption [30] |

| Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) | Entire genome (100%) | Comprehensive; includes non-coding regions; structural variants | Cancer germline predisposition; comprehensive biomarker discovery | 15.1% CAGR (2025-2030); higher cost per sample [33] |

| Targeted Gene Panels | Selected genes (<1% of genome) | Highest depth; lowest cost per sample; simplified analysis | Companion diagnostics; recurrence monitoring; focused biomarker testing | Expanding with pharmacogenomics; often bundled with profiling [34] |

The complementary relationship between these technologies creates a multi-layered genomic analysis ecosystem, with WES serving as a cornerstone approach for comprehensive yet cost-effective mutation profiling in cancer research and clinical practice.

Key Market Drivers and Adoption Trends

Economic and Technological Drivers

The expanding adoption of whole exome sequencing is propelled by several powerful economic and technological drivers that have transformed its feasibility and application scale.

Precipitous Decline in Sequencing Costs: The fundamental economic barrier to comprehensive genomic analysis has dramatically lowered, enabling broader implementation across research institutions and healthcare systems. Continuous innovations in sequencing chemistry, instrumentation, and workflow automation have contributed to this trend, making WES increasingly accessible [31].

Expanding Clinical and Research Applications: WES has evolved from a primarily research-focused tool to an integral component of clinical oncology, with applications spanning diagnostic characterization, therapeutic targeting, and prognostic assessment. The technology's capacity to identify clinically actionable mutations across the entire exome makes it particularly valuable for molecular tumor boards and personalized treatment planning [29] [2].

Advancements in Bioinformatics and Analytics: The development of sophisticated computational tools and machine learning algorithms has significantly enhanced the interpretation of WES data, transforming raw sequence information into clinically actionable insights. These bioinformatic advancements help address the challenge of variant interpretation, particularly for rare or novel mutations [31].

Application-Specific Adoption Trends

The implementation of WES across the oncology continuum reflects both its versatility and growing evidence base supporting its clinical utility.

Drug Discovery and Development: The pharmaceutical industry has emerged as the largest application segment for WES, utilizing the technology to identify novel therapeutic targets, validate mechanism of action, and stratify patient populations for clinical trials. WES enables comprehensive pharmacogenomic profiling that informs drug development pipelines from target identification through post-marketing surveillance [30].

Clinical Diagnostics Adoption: Hospitals and diagnostic laboratories represent the fastest-growing end-user segment, incorporating WES into routine oncologic practice for molecular classification of tumors, identification of hereditary cancer syndromes, and guidance of therapeutic decisions. This trend is particularly evident in academic medical centers and comprehensive cancer centers, where WES facilitates data-driven precision oncology [30].

Translational Research Applications: Cancer research institutions utilize WES to elucidate disease mechanisms, investigate clonal evolution, understand therapy resistance mechanisms, and identify novel biomarkers. Large-scale research initiatives like the UK Biobank, which performed WES on 454,787 participants, demonstrate the power of this approach for gene-trait association studies at unprecedented scale [35].

Analytical Frameworks: Methodologies and Technical Standards

Whole Exome Sequencing Wet-Lab Workflow

The standard analytical pipeline for WES in cancer applications involves multiple critical steps to ensure reliable and clinically relevant results.

Sample Acquisition and Quality Assessment: The initial critical step involves obtaining high-quality tumor samples, typically through surgical resection or biopsy, with careful pathological examination to ensure adequate tumor cellularity (generally >20-30% tumor content). Paired normal samples (from blood, saliva, or adjacent normal tissue) are essential for distinguishing somatic tumor mutations from germline variants [2] [32]. Sample preservation method (fresh frozen vs. FFPE) significantly impacts DNA quality and sequencing performance, with FFPE samples often exhibiting greater DNA fragmentation that requires specialized processing [2].

Library Preparation and Exome Capture: Following DNA extraction and quality control, sequencing libraries are prepared through fragmentation, end-repair, adapter ligation, and PCR amplification. Exome capture is predominantly performed using either microarray-based or magnetic bead-based hybridization approaches, with the latter being more widely adopted due to procedural simplicity and efficiency [2]. Commercially available capture platforms from Agilent (SureSelect) and Roche (NimbleGen) target approximately 39 million base pairs across the coding regions of 18,893 genes [35] [28].

Sequencing and Data Generation: Actual sequencing is primarily conducted using Illumina platforms (e.g., NovaSeq 6000), which employ sequencing-by-synthesis technology to generate high-quality short-read data. The sequencing depth required for cancer WES applications typically exceeds 100x for tumor samples and 50x for matched normal samples to ensure sensitive detection of somatic mutations present in tumor subpopulations [2] [32].

Bioinformatics Analysis Framework

The computational analysis of WES data represents a critical component of the workflow, transforming raw sequence data into biologically and clinically meaningful insights.

Variant Detection Algorithms: Multiple specialized algorithms have been developed to identify different classes of genomic alterations from WES data:

Single Nucleotide Variants (SNVs) and Insertions/Deletions (Indels): Tools such as MuTect2, VarScan2, Strelka, and FreeBayes employ distinct statistical approaches to distinguish true somatic mutations from sequencing artifacts and germline polymorphisms [2]. These tools typically require matched tumor-normal pairs to control for individual genetic background.

Copy Number Variations (CNVs): CNV detection algorithms (e.g., EXCAVATOR, CNVkit) analyze depth of coverage ratios between tumor and normal samples to identify genomic regions with significant amplifications or deletions, which are common drivers in cancer pathogenesis [2].

Variant Annotation and Prioritization: Identified variants undergo comprehensive functional annotation to predict biological consequences, including effects on protein function (e.g., missense, truncating), population allele frequency, conservation scores, and predicted pathogenicity using tools such as SIFT, PolyPhen-2, and CADD. This annotation process facilitates prioritization of likely driver mutations over passenger alterations [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Whole Exome Sequencing

| Product Category | Example Products | Key Functions | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exome Capture Kits | Agilent SureSelect Human All Exon V6; Roche NimbleGen SeqCap EZ | Hybridization-based enrichment of exonic regions; target definition | Capture efficiency; uniformity of coverage; target region specificity [2] [32] |

| Library Preparation Kits | Illumina DNA Prep; KAPA HyperPrep | Fragmentation, end-repair, adapter ligation, PCR amplification | Input DNA requirements; compatibility with FFPE samples; GC bias [32] |

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina NovaSeq 6000; Illumina HiSeq | Massively parallel sequencing; data generation | Read length; outputs; error profiles; cost per gigabase [32] |

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit; Maxwell RSC DNA FFPE Kit | DNA isolation from various sample types; quality assessment | Yield; fragment size distribution; inhibitor removal [32] |

| Target Enrichment Systems | Illumina Exome Panel; Twist Human Core Exome | Probe design for exonic region capture | Target coverage; off-target rates; hands-on time [31] |

Research Applications: Elucidating Cancer Mechanisms

Case Study: Genomic Basis of Histological Transformation in Lung Cancer

A 2025 study by Wang et al. utilized WES to investigate the genomic alterations underlying the transformation of EGFR-mutated lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) to small cell lung cancer (SCLC) following tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) therapy [32]. This transformation represents a clinically significant resistance mechanism that substantially alters disease management and patient prognosis.

Experimental Methodology: The researchers performed WES on 35 samples across three cohorts: 5 primary LUAD samples obtained before SCLC transformation, 12 transformed SCLC samples collected after EGFR-TKI resistance development, and 18 de novo SCLC samples for comparison [32]. DNA was extracted from FFPE tissue sections with tumor purity exceeding 90%, and libraries were prepared using the Agilent SureSelect Human All Exon V6 kit followed by sequencing on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform [32].

Key Findings: The analysis revealed that while TP53 mutations and RB1 loss were present in transformed SCLC (70% and 30% respectively), they were not universal, suggesting additional mechanisms facilitate this histological transformation [32]. Transformed SCLC exhibited distinctive genomic features, including mutations in COL22A1 and ALMS1 that were shared with de novo SCLC, while mutations in PTCH2, CNGB3, SPTBN5, CROCC, and MYO15A were more specific to the transformed cases [32]. Notably, transformed SCLC demonstrated significantly higher genomic instability compared to both primary LUAD and de novo SCLC, evidenced by elevated measures of homologous recombination deficiency (HRD), uniparental disomy (UPD), and loss of heterozygosity (LOH) [32].

Large-Scale Population Studies: The UK Biobank Initiative

The UK Biobank exome sequencing project represents one of the most comprehensive applications of WES in population-scale genetics, sequencing 454,787 participants and identifying 12 million coding variants [35]. This resource has enabled unprecedented analysis of gene-trait associations, including cancer-related phenotypes.

Experimental Methodology: The consortium employed a standardized WES approach achieving 95.8% of targeted bases covered at ≥20× depth, identifying 12.3 million variants across 18,893 genes [35]. Association testing between rare putative loss-of-function (pLOF) and deleterious missense variants with 3,994 health-related traits revealed 564 genes with significant trait associations, many with implications for cancer risk and biology [35].

Oncological Insights: The scale of this dataset enables detection of associations with very rare variants, exemplified by the discovery that carriers of singleton pLOF variants in RRBP1 exhibited significantly lower apolipoprotein B levels, suggesting a role in lipid metabolism that may influence cancer risk or tumor microenvironment [35]. Furthermore, genes targeted by FDA-approved drugs were 3.6-fold more common among the associated genes, highlighting the potential for therapeutic discovery through WES analysis [35].

Market Challenges and Future Directions

Analytical and Implementation Barriers

Despite rapid growth and technological advancement, several significant challenges constrain broader adoption of WES in cancer research and clinical practice.

Bioinformatics Bottleneck: The complexity of WES data analysis remains a substantial barrier, requiring specialized computational expertise, sophisticated infrastructure, and standardized analytical pipelines. Variant interpretation, particularly for rare or novel mutations, demands integration of multiple evidence sources and clinical correlation [31]. The absence of universal standards for variant classification and reporting further complicates clinical implementation.

Workforce and Infrastructure Limitations: The effective implementation of WES requires multidisciplinary expertise spanning molecular biology, bioinformatics, oncology, and genetics. The scarcity of professionals with this integrated skill set represents a significant constraint on market growth, particularly in emerging markets and resource-limited settings [30]. Additionally, the storage, management, and analysis of large WES datasets necessitate substantial computational resources that may exceed the capabilities of smaller institutions.

Evidence Generation and Reimbursement Challenges: While the clinical validity of WES is well-established, demonstrations of clinical utility in improving patient outcomes remain limited, particularly for specific cancer types and clinical scenarios [28]. This evidence gap influences reimbursement policies and institutional adoption, with payers increasingly requiring proof of improved health outcomes beyond mere technical capability or diagnostic yield.

Emerging Trends and Future Opportunities

Several emerging trends are poised to shape the future evolution of WES applications in cancer research and clinical practice.

Integration with Artificial Intelligence: Machine learning and AI approaches are increasingly being applied to WES data to enhance variant interpretation, predict functional impact, identify novel genomic signatures, and correlate mutational profiles with treatment responses [31]. These approaches hold particular promise for deciphering the clinical significance of variants of uncertain significance (VUS) and identifying complex genomic patterns that transcend individual mutations.

Expansion in Drug Development: WES is playing an increasingly central role in oncology drug development, from target identification and validation to patient stratification and clinical trial enrichment. The growing emphasis on targeted therapies and personalized treatment approaches ensures continued integration of comprehensive genomic profiling into pharmaceutical R&D pipelines [30].

Technological Convergence: The convergence of WES with complementary technologies—including transcriptomic sequencing, epigenomic profiling, and single-cell analysis—enables multi-dimensional characterization of tumor biology that extends beyond the coding genome. These integrated approaches provide more comprehensive insights into cancer mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities.

Whole exome sequencing has established itself as a cornerstone technology in modern cancer research and clinical oncology, driven by continuous technological refinement, declining costs, and expanding evidence of clinical utility. The market's robust growth trajectory reflects the fundamental value of comprehensive genomic assessment in understanding cancer biology, guiding therapeutic development, and personalizing patient management. While challenges related to data interpretation, infrastructure, and evidence generation persist, ongoing innovations in sequencing technology, analytical methodologies, and clinical integration promise to further expand the applications and impact of WES in oncology. As the field continues to evolve, WES is positioned to remain an essential component of the precision oncology toolkit, bridging the gap between targeted gene panels and whole genome sequencing in both research and clinical domains.

Methodological Advances and Translational Applications in Oncology

Whole exome sequencing (WES) has emerged as a powerful and cost-effective genomic technique for investigating the genetic underpinnings of cancer. This method focuses on sequencing the protein-coding regions of the genome, which constitute approximately 1-2% of the human genome yet harbor an estimated 85% of disease-causing variants [36]. In oncology, WES enables researchers and clinicians to uncover somatic mutations, identify inherited cancer susceptibility variants, and characterize the genomic landscape of tumors to guide personalized treatment strategies [2] [37]. The targeted nature of WES allows for deeper sequencing coverage of clinically relevant regions at a fraction of the cost and data burden of whole genome sequencing (WGS), making it particularly suitable for cancer research applications where budget and computational resources are often limiting factors [38] [36].

The analysis of cancer samples presents unique challenges in the WES workflow. Unlike germline genetic studies, cancer sequencing requires distinguishing somatic (tumor-acquired) mutations from germline (inherited) variants, which necessitates sequencing matched normal tissue from the same patient [39]. Furthermore, tumor samples often exhibit heterogeneity, variable tumor purity, and complex genomic alterations that complicate variant detection and interpretation [2] [40]. This technical guide provides a comprehensive overview of the end-to-end WES workflow specifically optimized for cancer samples, from initial DNA preparation through final variant calling and analysis.

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for whole exome sequencing, from sample preparation through data analysis.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

DNA Extraction and Quality Control

Protocol Objective: To obtain high-quality, high-molecular-weight DNA from patient samples suitable for whole exome sequencing. In cancer research, this typically involves processing tumor samples (often from FFPE tissues, frozen tissues, or liquid biopsies) and matched normal samples (commonly from blood, saliva, or T-cells) [39].

Materials Required:

- QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit (for formalin-fixed tissues)

- QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (for blood samples)

- Proteinase K

- Ethanol (96-100%)

- Nuclease-free water

- Agarose gel equipment

- Spectrophotometer (NanoDrop) or fluorometer (Qubit)

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Sample Lysis: For FFPE tissues, cut 2-3 sections of 10 μm thickness. Digest tissue with proteinase K for 3-16 hours at 56°C until completely lysed. For blood samples, mix 200 μL with 200 μL PBS and 20 μL QIAGEN Protease [2].

- DNA Binding: Add 400 μL of buffer AL to the lysate, mix thoroughly, and incubate at 70°C for 10 minutes for FFPE samples. Add 400 μL ethanol (96-100%) and mix by vortexing.

- Column Purification: Apply the mixture to QIAamp Mini spin columns and centrifuge at 6000 × g for 1 minute. Wash once with 500 μL AW1 buffer and twice with 500 μL AW2 buffer.

- DNA Elution: Elute DNA in 50-100 μL nuclease-free water or buffer AE preheated to 70°C for FFPE samples.

- Quality Assessment: Measure DNA concentration using fluorometric methods (recommended for FFPE samples). Assess DNA integrity by agarose gel electrophoresis or bioanalyzer. Acceptable samples should have A260/A280 ratio of 1.8-2.0 and show minimal fragmentation (for fresh samples) [2].

Critical Considerations for Cancer Samples:

- FFPE-derived DNA often shows fragmentation; minimum DNA fragment size should be >150 bp for library preparation.

- Tumor purity assessment through pathological review is essential before sequencing.

- For myeloid cancers, T-cells are recommended as the normal reference due to minimal risk of neoplastic contamination compared to saliva or skin biopsies [39].

DNA Fragmentation and Library Preparation

Protocol Objective: To fragment DNA to appropriate size for sequencing and attach sequencing adapters to create sequencing libraries.

Materials Required:

- Covaris S2 ultrasonicator (for mechanical shearing) or NEBNext Fragmentase (for enzymatic fragmentation)

- End Repair Module

- A-Tailing Module

- Ligation Module

- Size Selection Beads (AMPure XP)

- Library Quantification Kit

- Unique dual index adapters

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- DNA Fragmentation:

- Mechanical Shearing: Dilute 100-1000 ng DNA to 50 μL in TE buffer. Shear using Covaris S2 with following settings: Duty Cycle 10%, Intensity 5, Cycles per Burst 200, Time 45 seconds to obtain 150-200 bp fragments.

- Enzymatic Fragmentation: For 100 ng DNA, add 7 μL Fragmentase, incubate at 37°C for 15-30 minutes, then heat-inactivate at 70°C for 10 minutes [37].

End Repair:

- Combine 50 μL fragmented DNA with 7 μL End Repair Reaction Buffer and 3 μL End Repair Enzyme Mix.

- Incubate at 20°C for 30 minutes, then purify with 1.8X volume AMPure XP beads.

A-Tailing:

- Resuspend DNA in 25 μL nuclease-free water.

- Add 10 μL A-Tailing Reaction Buffer and 5 μL A-Tailing Enzyme.

- Incubate at 37°C for 30 minutes, then purify with 1.8X AMPure XP beads.

Adapter Ligation:

- Resuspend DNA in 25 μL nuclease-free water.

- Add 5 μL Ligation Buffer, 10 μL PEG 8000, 5 μL Ligation Enhancer, 2.5 μL Adapter (15 μM), and 2.5 μL DNA Ligase.

- Incubate at 20°C for 15 minutes.

- Purify with 0.8X AMPure XP beads to remove excess adapters.

Library Amplification:

- Amplify library using 8-12 cycles of PCR with indexed primers.

- Perform final purification with 0.8X AMPure XP beads to remove primers and select appropriate fragment sizes.

Library QC:

- Quantify using qPCR-based library quantification kit.

- Assess size distribution using Bioanalyzer or TapeStation (expected peak: 250-300 bp).

Exome Capture and Target Enrichment

Protocol Objective: To selectively capture and enrich exonic regions from the sequencing library using hybridization-based capture methods.

Materials Required:

- Twist Human Core Exome Kit or Agilent SureSelect Human All Exon Kit

- Streptavidin-coated magnetic beads

- Hybridization buffer

- Wash buffers

- Heated thermal mixer with lid

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Hybridization:

- Combine 200-500 ng library DNA with 5 μL Blocking Mix and 2 μL Twist Universal Adapter in nuclease-free water to total 15 μL.

- Add 15 μL Hybridization Buffer and 5 μL Exome Probe Pool (from Twist Human Core Exome Kit).

- Denature at 95°C for 2 minutes, then incubate at 58°C for 16 hours in a thermal mixer [37].

Capture with Magnetic Beads:

- Pre-wash streptavidin magnetic beads with bead wash buffer.

- Add beads to hybridization reaction and incubate at 58°C for 45 minutes with mixing.

Washing:

- Capture beads on magnet and discard supernatant.

- Wash twice with 200 μL Wash Buffer 1 at 58°C for 5 minutes.

- Wash twice with 200 μL Wash Buffer 2 at room temperature for 2 minutes.

- Perform final wash with 200 μL nuclease-free water.

Amplification of Captured Library:

- Resuspend beads in 25 μL PCR mix with 12 cycles of amplification.

- Purify with 0.8X AMPure XP beads.

- Quantify final library by qPCR and analyze size distribution by Bioanalyzer.

Critical Considerations:

- GC-rich regions may be underrepresented; consider adding GC-content balanced polymer if needed.

- For cancer research, ensure capture kit covers known cancer-associated non-coding regions (e.g., TERT promoter) if relevant to study [2].

- Use the same exome capture kit across all samples in a study to ensure consistency.

Bioinformatic Analysis Pipeline

Primary Data Processing and Quality Control

The initial phase of bioinformatic analysis focuses on assessing raw sequencing data quality and preparing it for variant discovery. This involves multiple quality control checkpoints and processing steps as illustrated below.

Key Tools and Procedures:

Initial Quality Control (FastQC):

- Assess per-base sequencing quality, GC content, adapter contamination, and overrepresented sequences.

- Critical metrics: Q30 score >80%, GC content matching expected distribution, minimal adapter contamination.

Read Trimming and Filtering (Trimmomatic, Cutadapt):

- Remove adapter sequences: ILLUMINACLIP:adapters.fa:2:30:10

- Quality trimming: LEADING:20, TRAILING:20, SLIDINGWINDOW:4:20

- Discard reads shorter than 36 bp: MINLEN:36

Alignment to Reference Genome (BWA-MEM):

Post-Alignment Processing:

- Mark duplicates:

gatk MarkDuplicates -I sorted.bam -O marked_duplicates.bam -M metrics.txt - Base quality score recalibration:

gatk BaseRecalibrator -I marked_duplicates.bam -R reference.fasta --known-sites known_sites.vcf -O recal_data.table

- Mark duplicates:

Quality Metrics for Cancer Samples:

- Minimum coverage: 100X for tumor, 60X for normal

- Uniformity of coverage: >80% of target bases at 20X coverage

- Duplication rate: <20% for fresh samples, <40% for FFPE samples

- Contamination check: VerifyBamID or similar tools

Variant Calling Methods in Cancer Genomics

Variant calling in cancer samples requires specialized approaches to distinguish somatic mutations from germline variants and account for tumor-specific characteristics such as heterogeneity and aneuploidy.

Somatic Variant Calling Workflow:

Tumor-Normal Pair Analysis:

- Process tumor and matched normal samples through the same pipeline

- Use Mutect2 for somatic SNV and indel calling:

gatk Mutect2 -R reference.fasta -I tumor.bam -I normal.bam -O somatic.vcf - Filter results:

gatk FilterMutectCalls -V somatic.vcf -O filtered_somatic.vcf

Additional Callers for Comprehensive Detection:

- VarScan2:

varscan somatic normal.pileup tumor.pileup output --min-coverage 10 --min-var-freq 0.1 --somatic-p-value 0.05 - Strelka2: Configure via

configureStrelkaSomaticWorkflow.pyfor small variant calling - For structural variants: Manta, Delly, or Lumpy

- VarScan2:

False Positive Filtering Strategies:

- Remove variants present in population databases (gnomAD, 1000 Genomes)

- Filter out artifacts using blacklist files (e.g., from GDC) [40]

- Apply panel of normals (PoN) specific to your sequencing platform and protocol

- For tumor-only analysis, implement stringent bioinformatic filtering: remove variants with VAF >0.4 or <0.1, exclude common germline polymorphisms [39]

Performance Characteristics of Variant Callers:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Selected Variant Calling Tools for Cancer WES

| Tool | Variant Types | Strengths | Optimal Use Cases | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mutect2 | SNVs, indels | High specificity, built-in filters | Standard somatic calling | May miss low-VAF variants |

| VarScan2 | SNVs, indels | Sensitive for low-frequency variants | Low-purity tumors | Higher false positive rate |

| Strelka2 | SNVs, indels | Good performance across variant sizes | High-specificity needs | Longer runtime |

| FreeBayes | SNVs, indels, MNVs | Sensitive, haplotype-aware | Research settings | High false positives without filtering |

| Manta | SVs, indels | Comprehensive structural variant calling | Chromosomal rearrangements | Limited to larger variants |

Benchmarking of No-Code Variant Calling Solutions

For laboratories without extensive bioinformatics support, several commercial variant calling solutions offer user-friendly interfaces while maintaining analytical accuracy. Recent benchmarking studies provide performance comparisons of these platforms.

Table 2: Performance Benchmarking of Commercial Variant Calling Software (GIAB Reference Data) [43]

| Software | SNV Recall (%) | SNV Precision (%) | Indel Recall (%) | Indel Precision (%) | Runtime (Minutes) | Cost Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina DRAGEN | >99 | >99 | >96 | >96 | 29-36 | Annual subscription + credits |

| CLC Genomics | 98-99 | 98-99 | 94-96 | 94-96 | 6-25 | Annual subscription |

| Varsome Clinical | 98-99 | 98-99 | 93-95 | 93-96 | 45-90 | Per sample |

| Partek Flow (GATK) | 97-98 | 97-98 | 90-93 | 90-93 | 216-1782 | Annual subscription |

| Partek Flow (Freebayes+Samtools) | 95-97 | 95-97 | 85-90 | 85-90 | 216-1782 | Annual subscription |

Key Findings from Benchmarking Studies:

- Illumina's DRAGEN Enrichment achieved the highest precision and recall scores for both SNV and indel calling at over 99% for SNVs and 96% for indels [43].

- All four benchmarked software shared 98-99% similarity in true positive variants, indicating high concordance for common variants.

- Run times varied significantly, with CLC and Illumina being the fastest (6-36 minutes), while Partek Flow took substantially longer (3.6 to 29.7 hours) [43].

- The choice between software often involves trade-offs between accuracy, runtime, and cost, with Illumina DRAGEN providing the best performance but at a premium price point.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Whole Exome Sequencing in Cancer Studies

| Category | Specific Product Examples | Key Features | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exome Capture Kits | Agilent SureSelect XT HS2, Twist Human Core Exome, Illumina Nextera Rapid Capture | Comprehensive exome coverage (39-64 Mb), optimized for FFPE DNA | Agilent SureSelect provides 60 Mb coverage with 120-mer probes; verify coverage of cancer-relevant genes |

| Library Prep Kits | Illumina DNA Prep, KAPA HyperPrep, NEBNext Ultra II FS | Compatibility with low-input DNA, FFPE-optimized protocols | For FFPE samples: use kits with uracil-tolerant enzymes and formalin-damage reversal capabilities |

| Target Enrichment Reagents | IDT xGen Universal Blockers, Twist Universal Adapter System | Reduced off-target capture, improved uniformity | Universal blockers improve performance in multiplexed sequencing |

| DNA Extraction Kits | QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit, Maxwell RSC Blood DNA Kit, QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit | High yield from challenging samples, minimal co-purification of inhibitors | For myeloid cancers: pair tumor with T-cell derived normal DNA [39] |

| Quality Control Tools | Agilent TapeStation, Qubit dsDNA HS Assay, Quant-iT PicoGreen | Accurate quantification of degraded DNA, fragment size analysis | Fluorometric quantification preferred over spectrophotometry for FFPE samples |

| Sequencing Reagents | Illumina NovaSeq 6000 S-Prime, NextSeq 1000/2000 P2 reagents | High-output sequencing, reduced error rates | Match sequencing depth to application: >100X for tumor, >60X for normal |

The end-to-end workflow for whole exome sequencing in cancer samples encompasses carefully optimized wet-lab procedures and bioinformatic analyses tailored to the unique challenges of cancer genomics. From appropriate sample selection and library preparation through sophisticated variant calling and interpretation, each step requires meticulous execution to generate clinically actionable results. The benchmarking data presented here demonstrates that both code-free commercial solutions and custom bioinformatic pipelines can achieve high accuracy when properly validated. As WES continues to evolve, standardization of protocols and rigorous validation using reference materials like GIAB will be essential for translating cancer genomic findings into improved patient outcomes.

Whole exome sequencing (WES) has emerged as a powerful clinical diagnostic tool for discovering the genetic basis of many diseases, including cancer. In the context of oncology, WES enables molecular tumor boards to identify therapeutic targets for patients with advanced cancers by sequencing the protein-coding regions of the genome [44]. While targeted panel sequencing has been widely adopted in clinical settings, evidence suggests that broader genomic analyses like WES can provide additional clinical benefit for selected patients. A study of 38 patients with advanced cancers found that WES enabled additional clinically highly actionable recommendations that would have been missed with panel sequencing alone [44]. These recommendations were often related to complex molecular biomarkers such as homologous recombination deficiency or high tumor mutational burden, with corresponding recommendations for targeted therapies like PARP inhibitors or checkpoint inhibitors.

The implementation of WES in clinical cancer research presents significant scalability challenges. Traditional manual sequencing workflows require extensive hands-on time and are prone to variability, creating bottlenecks in processing large sample volumes. For cancer patients awaiting treatment decisions, rapid turnaround times are critical—treatment initiation before comprehensive genomic profiling results are available can negatively affect patient outcomes [45]. This technical guide examines the strategies, technologies, and methodologies for automating high-throughput diagnostic workflows to achieve both scale and speed in WES-based cancer research.

Clinical Value of Whole Exome Sequencing in Oncology

Complementary Benefits of WES and Panel Sequencing

Research comparing WES to medium-size gene panels (up to 203 genes) in an all-comer real-world molecular tumor board demonstrated that WES provides measurable clinical benefits. In a cohort of 38 patients with advanced cancers, approximately two-thirds with common and one-third with rare cancers, WES enabled additional treatment recommendations that would not have been issued based on panel sequencing alone [44]. The study documented that:

- Patients received a total of 45 treatment recommendations (range 0-4), with 29 having clinical level of evidence and/or entailing feasible study enrollment

- Sixteen recommendations (seven highly actionable) were issued only on the basis of WES results

- Three of these highly actionable recommendations were related to complex molecular biomarkers

- One of eight implemented treatments was based on biomarkers derived exclusively by WES

Technical Considerations for WES in Cancer Diagnostics

A major consideration in WES is the uneven coverage of sequence reads over exome targets, which contributes to low-coverage regions that hinder accurate variant calling [46]. The distribution of sequence coverage varies both locally (coverage of a given exon across different platforms) and globally (coverage of all exons across the genome in a given platform). Research has identified that low-coverage regions encompassing functionally important genes are often associated with high GC content, repeat elements, and segmental duplications [46]. These coverage deficiencies can be quantitatively assessed using metrics such as Cohort Coverage Sparseness (CCS) and Unevenness (UE) scores, which enable detailed evaluation of read distribution [46].

Table 1: Clinical Impact of Additional WES Beyond Panel Sequencing

| Metric | Panel Sequencing Only | With Additional WES |

|---|---|---|

| Total treatment recommendations | 29 | 45 |

| Highly actionable recommendations | 22 | 29 |

| Recommendations based on complex biomarkers | Limited | 7 highly actionable |

| Therapies enabled | Standard targeted | PARP inhibitors, checkpoint inhibitors |

Automation Platforms for Scalable Sequencing Workflows

High-Throughput Library Preparation Systems