The Invisible Backpack: How Ultrafine Hydrogel Nanoparticles are Revolutionizing Medicine

Delivering Life-Saving Drugs with Pinpoint Precision

Imagine a world where a powerful cancer drug travels directly to a tumor, bypassing healthy cells entirely. It doesn't release its toxic cargo until it's inside the cancerous cell, eliminating side effects and supercharging treatment. This isn't science fiction; it's the promise of ultrafine hydrogel nanoparticles—tiny, gel-based sponges that are changing the way we think about medicine.

For decades, one of the biggest challenges in treating diseases like cancer has been the collateral damage. Chemotherapy drugs are potent but imprecise, attacking healthy and diseased cells alike. The solution? A microscopic delivery vehicle that can navigate the bloodstream, find the right address, and deliver its package safely. Thanks to groundbreaking research, ultrafine hydrogel nanoparticles are emerging as that perfect vehicle, offering a new era of targeted, intelligent therapy.

What Exactly Are These "Invisible Backpacks"?

To understand the breakthrough, let's break down the name:

Ultrafine

These particles are incredibly small, typically between 1 and 100 nanometers. To put that in perspective, a single human hair is about 80,000-100,000 nanometers wide. Their minuscule size allows them to travel through the bloodstream and even slip inside individual cells.

Hydrogel

Think of a super-absorbent, water-filled jelly. Hydrogels are networks of polymer chains that can soak up huge amounts of water, just like a kitchen sponge. This gives them a flexible, soft structure.

Nanoparticle

A microscopic particle engineered to have specific properties.

Key Insight

Put it all together, and you have a tiny, squishy, water-filled sponge that can be loaded with therapeutic cargo like drugs, genes, or imaging agents. Their gel-like nature is key—it's biocompatible (not harmful to living tissue) and can be designed to respond to its environment.

The "Smart" Sponge: How They Work

The true genius of these nanoparticles lies in their "smart" design. Scientists can engineer them to be responsive to specific biological triggers:

Thermo-responsive

They shrink or swell with changes in temperature. A slight fever around a tumor could trigger drug release.

pH-responsive

The environment inside a tumor or within a cell's digestive compartment is more acidic. The nanoparticles burst open only in this acidic environment.

Enzyme-responsive

They can be built to be broken down only by specific enzymes that are overproduced at a disease site.

This intelligence ensures the "invisible backpack" only drops its load when and where it's needed most.

"The ability to design nanoparticles that respond to specific biological cues represents a paradigm shift in drug delivery."

A Closer Look: The Experiment That Proved It Works

To move from theory to reality, scientists must prove these nanoparticles can function inside the complex environment of a living cell. Let's dive into a key experiment that did just that.

The Mission: Deliver a Drug and Watch it Work in Real-Time

The objective was straightforward but ambitious:

- Create ultrafine, pH-responsive hydrogel nanoparticles.

- Load them with a model drug (a fluorescent dye that stands in for a real cancer drug).

- Introduce them to human cancer cells in a lab.

- Visually confirm that the particles enter the cells and release their cargo in response to the cell's natural acidity.

The Step-by-Step Methodology

The researchers followed a meticulous process:

Synthesis

Using a controlled chemical process called precipitation polymerization, they created a batch of ultrafine hydrogel nanoparticles. The polymer chains were designed to be stable at neutral pH (like in blood) but fall apart in acidic conditions.

Loading

The newly synthesized nanoparticles were soaked in a solution containing a fluorescent dye. The gel-like network absorbed the dye, trapping it inside.

Characterization

Using powerful tools like Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)—thanks to experts like Dr. Kei Sun—they confirmed the particles' size, shape, and uniformity. They were perfectly spherical and under 50 nanometers in diameter .

Cell Incubation

Human liver cancer cells (HepG2) were grown in a lab dish. The loaded nanoparticles were added to the dish and left for several hours, allowing the cells to naturally ingest them.

Imaging and Analysis

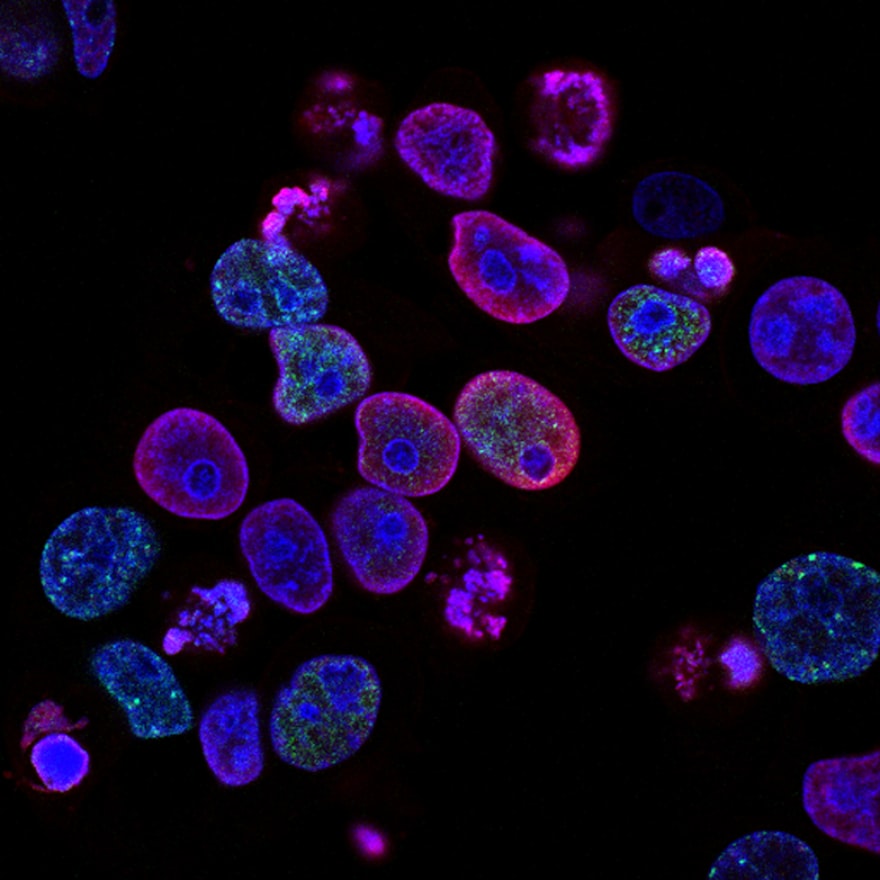

Using a confocal laser scanning microscope, the scientists took high-resolution, time-lapse images of the cells. This allowed them to see the fluorescent signal from the nanoparticles and track their location inside the living cells .

Results and Analysis: A Successful Delivery

The results were clear and compelling:

The microscope images showed that the cancer cells had readily engulfed the nanoparticles through a process called endocytosis. The particles were now inside the cells, contained within small pockets called endosomes.

As expected, the endosomes became more acidic over time. This drop in pH caused the hydrogel nanoparticles to swell and rapidly disassemble, releasing the fluorescent dye into the main body of the cell (the cytoplasm). The entire cell began to glow with fluorescence, proving the "drug" had been successfully delivered.

Scientific Importance

This experiment was a critical proof-of-concept. It demonstrated that these synthetic particles could not only survive in a biological environment but also perform their intended function—responding to a specific cellular trigger to release a payload. It bridges the gap between material science and practical medicine.

The Data Behind the Discovery

Quantitative analysis confirmed the effectiveness of the ultrafine hydrogel nanoparticles in drug delivery.

Nanoparticle Characterization

This table shows the key physical properties of the nanoparticles, confirming they are the right size and carry a significant payload.

| Property | Empty Nanoparticles | Drug-Loaded Nanoparticles |

|---|---|---|

| Average Diameter (nm) | 42 ± 5 nm | 48 ± 6 nm |

| Zeta Potential (mV) | -15.2 mV | -11.8 mV |

| Drug Loading Capacity | N/A | 22.5% |

| Polydispersity Index | 0.08 | 0.12 |

Cellular Uptake Efficiency

This data quantifies how quickly and efficiently the cells internalize the nanoparticles.

| Incubation Time | Percentage of Cells with Nanoparticles | Average Particles per Cell |

|---|---|---|

| 1 hour | 25% | 45 |

| 3 hours | 78% | 210 |

| 6 hours | >95% | 550 |

Drug Release Profile

This data proves the "smart" release mechanism, showing a much faster release in acidic conditions that mimic a cell's interior.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Creating and testing these nanoparticles requires a specialized toolkit. Here are some of the essential components used in the featured experiment and the wider field.

| Reagent/Material | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| N-Isopropylacrylamide (NIPAM) | The main building block (monomer) for creating the temperature- and pH-responsive hydrogel polymer. |

| Acrylic Acid (AAc) | A co-monomer that introduces pH-sensitivity into the polymer network, allowing it to respond to acidity. |

| Cross-linker (e.g., BIS) | Acts like a molecular staple, linking the polymer chains together to form the 3D gel network. |

| Fluorescent Dye (e.g., Doxorubicin) | Serves as a model drug. Doxorubicin is both a real chemotherapy drug and naturally fluorescent, making it perfect for tracking. |

| HepG2 Cell Line | A standardized line of human liver cancer cells used as a model to test the therapeutic effect in a lab setting. |

| Buffer Solutions (pH 7.4 & 5.0) | Used to mimic the physiological environment of the bloodstream (neutral pH) and the inside of a cell's endosome (acidic pH). |

Conclusion: A Bright Future for Personalized Medicine

The journey of ultrafine hydrogel nanoparticles from a synthetic concept to a functional therapeutic inside living cells marks a monumental leap forward. This technology holds the key to a future of precision medicine, where treatments are not a one-size-fits-all blast, but a targeted strike against disease.

While challenges remain—such as scaling up production and ensuring long-term safety in the human body—the foundation is solid. The "invisible backpack" is no longer invisible to science, and its potential to carry hope and healing directly to the source of our most daunting diseases has never been clearer.

This work demonstrates the tremendous potential of responsive nanomaterials to transform how we deliver therapeutics.

This work was supported by National Cancer Institute UIP contract N01-CO-37123.