SYBR Green vs. Probe-Based Detection for Cancer Genes: A Strategic Guide for Precision Oncology Research

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of SYBR Green and probe-based (e.g., TaqMan) qPCR methods for analyzing cancer genes, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

SYBR Green vs. Probe-Based Detection for Cancer Genes: A Strategic Guide for Precision Oncology Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of SYBR Green and probe-based (e.g., TaqMan) qPCR methods for analyzing cancer genes, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers foundational principles, including the distinct chemistries of DNA-binding dyes and fluorescent probes, and their application in detecting oncogenes, tumor suppressors, and emerging biomarkers like ctDNA and miRNAs. The content delivers practical methodological protocols, troubleshooting and optimization strategies for sensitive mutation detection, and a critical validation framework for assessing sensitivity, specificity, and cost-effectiveness. By synthesizing current data and real-world applications, this guide supports informed decision-making for robust, reliable genetic analysis in cancer research and diagnostic development.

Core Principles: Understanding SYBR Green and Probe-Based qPCR Chemistries

SYBR Green I represents a fundamental tool in molecular biology, enabling the detection and quantification of nucleic acids through its unique interaction with double-stranded DNA (dsDNA). This technical guide delves into the biophysical mechanism of SYBR Green, detailing how its fluorescence is activated upon binding to the minor groove of dsDNA. We explore the structure-property relationships that govern its binding modes, including intercalation and surface binding, and how these relate to its performance in quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR). Framed within the context of cancer gene research, this review provides a comparative analysis with probe-based detection methods (e.g., TaqMan), evaluating specificity, sensitivity, and cost-effectiveness for applications in gene expression profiling and biomarker validation. The discussion is supported by experimental data, detailed protocols, and analytical workflows relevant to researchers and drug development professionals.

SYBR Green I is an unsymmetrical cyanine dye that serves as a sensitive, fluorescent stain for nucleic acid detection and quantification [1] [2]. Its core structure consists of a benzothiazolium ring system linked by a monomethine bridge to a quinolinium ring system, with a substituent containing a heteroatom [1]. Initially developed as a safer and more quantifiable alternative to ethidium bromide for agarose gel electrophoresis, its applications have expanded to include dsDNA quantification in solution, flow cytometry, and most notably, real-time PCR [2] [1]. In the context of qPCR, SYBR Green I provides a simple and cost-effective means to monitor the amplification of DNA in real-time, which is crucial for gene expression analysis, genotyping, and pathogen detection [3] [4]. When discussing gene expression analysis, particularly for cancer research, the choice of detection chemistry—dye-based versus probe-based—can significantly impact the specificity, reliability, and cost of the experimental outcomes.

The Molecular Mechanism of Fluorescence Activation

The fluorescence of SYBR Green I is critically dependent on its binding to dsDNA. In its free, unbound state in solution, the dye exhibits very low fluorescence [5] [2]. However, upon binding to the minor groove of dsDNA, its fluorescence increases by up to 1,000-fold [5] [2]. This dramatic enhancement makes the fluorescent signal directly proportional to the amount of dsDNA present in the reaction tube [5].

Biophysical studies at defined dye-to-base pair ratios (dbpr) have revealed that SYBR Green I binds to dsDNA through two primary modes:

- Intercalation: This occurs at lower dbprs, where the dye molecules insert themselves between the base pairs of the DNA double helix [1].

- Surface Binding: At dbprs above approximately 0.15, the dye undergoes surface binding, which leads to a significant increase in fluorescence [1].

It is important to note that while SYBR Green I is highly selective for dsDNA, it can also bind to double-stranded RNA and, to a much lesser extent, single-stranded DNA (ssDNA), though the fluorescence from ssDNA complexes is at least 11-fold lower than that from dsDNA complexes [1]. The binding and subsequent fluorescence are also influenced by the DNA sequence, with studies showing sequence-specific binding using poly(dA) · poly(dT) and poly(dG) · poly(dC) homopolymers, and are affected by the salt composition of the buffer [1].

The following diagram illustrates the two binding modes of SYBR Green I and the resultant fluorescence activation.

SYBR Green in qPCR: A Comparative Framework with TaqMan

In quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR), SYBR Green I is used as an intercalating dye that binds to dsDNA PCR products as they are amplified [6] [7]. The accumulation of amplicons in each cycle is measured by the increasing fluorescent signal, allowing for the quantification of the initial target DNA. The cycle at which the fluorescence crosses a predetermined threshold (the Ct value) is used for quantification [7].

Key Advantages and Disadvantages in qPCR

The use of SYBR Green I in qPCR presents a distinct set of benefits and challenges, particularly when compared to probe-based methods like TaqMan.

Table 1: Comparison of SYBR Green and TaqMan qPCR Methods

| Feature | SYBR Green | TaqMan |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanism | Binds non-specifically to any dsDNA [6] [7] | Sequence-specific hydrolysis probe [5] [7] |

| Cost | Relatively cost-effective and inexpensive [5] [4] | More expensive due to labeled probes [5] [8] |

| Experimental Design | Easy setup; requires only primer design [6] | More complex; requires design of primers and probe [6] |

| Specificity | Lower; binds to primer-dimers and non-specific products [2] [6] | High; requires specific binding of both primer and probe [5] [6] |

| Multiplexing Capability | Not possible [3] | Possible with different colored probes [3] [7] |

| Required Post-PCR Analysis | Melting curve analysis essential [2] [7] | Not required [6] |

The Critical Role of Melting Curve Analysis

A mandatory step in any SYBR Green qPCR protocol is the melting curve analysis (also called dissociation curve analysis) [6] [7]. After the amplification cycles are complete, the temperature is gradually increased while fluorescence is continuously monitored. As the DNA melts and transitions from dsDNA to ssDNA, the SYBR Green dye is released, causing a drop in fluorescence. Plotting the negative derivative of this fluorescence change against temperature results in a melting peak specific to the amplicon's melting temperature (Tm) [7]. This analysis is crucial for verifying that a single, specific PCR product was amplified and for identifying the presence of primer-dimers or other non-specific products, which would appear as additional peaks [2] [7].

Application in Cancer Research: SYBR Green vs. Probe-Based Detection

The choice between SYBR Green and TaqMan chemistries is particularly relevant in cancer gene research, where accurately measuring gene expression, gene copy number variations, and mutations is paramount.

Quantitative Performance in Gene Expression Analysis

A 2014 study directly compared SYBR Green and TaqMan methods for quantifying the expression of adenosine receptor subtypes (A1, A2A, A2B, A3) in breast cancer tissues [5]. The researchers found that with the use of high-performance primers and optimized protocols, both methods demonstrated high amplification efficiencies (>95%) and produced positively correlated, significant data (p < 0.05) [5]. This indicates that for well-optimized assays, SYBR Green can yield data quality comparable to TaqMan for gene expression analysis [5].

Table 2: Performance Metrics from a Breast Cancer Gene Expression Study [5]

| Gene | Normalized Expression (SYBR Green) | Normalized Expression (TaqMan) | Correlation (Pearson) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A1 Adenosine Receptor | 1.44 | 1.38 | Positive and Significant (P < 0.05) |

| A2A Adenosine Receptor | 2.38 | 2.43 | Positive and Significant (P < 0.05) |

| A2B Adenosine Receptor | 3.79 | 3.84 | Positive and Significant (P < 0.05) |

| A3 Adenosine Receptor | 3.55 | 3.58 | Positive and Significant (P < 0.05) |

Sensitivity and Detection Limits

However, other studies highlight scenarios where TaqMan may be superior. In the detection of residual host-cell DNA from Chinese Hamster Ovary (CHO) cells—a common production host for biopharmaceuticals including cancer therapeutics—the TaqMan assay demonstrated a lower limit of detection (LOD) of 10 fg, compared to 100 fg for the SYBR Green assay [8]. Similarly, a study on enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis (ETBF), which is associated with colorectal cancer, found that SYBR Green qPCR underperformed in clinical stool samples. It detected only 13 out of 38 positive samples, whereas TaqMan qPCR and digital PCR detected 35 and 36, respectively [9]. The copy numbers reported by TaqMan were 48-fold higher than those from SYBR Green for the same samples, underscoring TaqMan's superior sensitivity and reliability in complex sample matrices [9].

The following workflow outlines the decision process for selecting a detection chemistry in a cancer research qPCR experiment.

Experimental Protocol: SYBR Green qPCR for Gene Expression

The following protocol is adapted from a study analyzing adenosine receptor gene expression in breast cancer tissues, providing a template for cancer-related gene targets [5].

Sample Preparation and RNA Extraction

- Tissue Samples: Breast cancer tissue samples are quickly placed in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C [5].

- Homogenization and RNA Extraction: Homogenize 20-40 mg of frozen tissue (e.g., using a bead-milling method in RLT buffer). Extract total RNA using a commercial kit (e.g., RNeasy plus mini kit, Qiagen) [5].

- Quality Control: Determine the concentration and purity of RNA by measuring UV absorption at 260/280 nm (e.g., using a NanoDrop system). Assess RNA integrity by electrophoresis on a denaturing 1% agarose gel [5].

Reverse Transcription and qPCR Setup

- cDNA Synthesis: Reverse transcribe 1 μg of total RNA into complementary DNA (cDNA) using a reverse transcription kit (e.g., Quantitect Rev. transcription kit, Qiagen) [5].

- Primer Design: Design primers to span exon-exon junctions to avoid amplification of genomic DNA. Use software (e.g., Beacon Designer) for design and ensure specificity [5].

- qPCR Reaction:

- Reaction Mixture: 25 μL total volume containing: 2 μL cDNA template, 1.5 μL each of forward and reverse primer, and 12.5 μL of SYBR Green master mix (e.g., Quantitect SYBR Green master mix, Qiagen) [5].

- Thermal Cycling Conditions (Rotor Gene 6000):

- Initial denaturation: 95°C for 10 min.

- 40 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 10 s.

- Annealing/Extension: 60°C for 20 s.

- Data Normalization: Include a reference gene (e.g., Beta-Actin, ACTB) in all runs to normalize the data and correct for variations in RNA quality and quantity. Calculate relative expression using the ΔΔCt method [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for SYBR Green qPCR

| Item | Function/Description | Example Product/Citation |

|---|---|---|

| SYBR Green Master Mix | Optimized buffer, nucleotides, polymerase, and SYBR Green dye for qPCR. | Quantitect SYBR Green Master Mix (Qiagen) [5] |

| RNA Extraction Kit | Purifies high-quality, DNA-free total RNA from tissues or cells. | RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen) [5] |

| Reverse Transcription Kit | Converts RNA template into stable cDNA for PCR amplification. | Quantitect Reverse Transcription Kit (Qiagen) [5] |

| Validated Primers | Sequence-specific oligonucleotides designed to flank the target amplicon. | Custom designed, e.g., by Beacon Designer software [5] |

| Nuclease-Free Water | Solvent free of RNases and DNases to prevent nucleic acid degradation. | Essential component of reaction mix [5] [4] |

SYBR Green I functions through a elegant mechanism of fluorescence enhancement upon binding to dsDNA, involving both intercalation and surface binding. Its utility in qPCR, especially for cancer gene research, is defined by a trade-off between cost-effectiveness and ease of use on one hand, and specificity and sensitivity on the other. While well-optimized SYBR Green assays can produce data comparable to TaqMan methods for standard gene expression analysis, probe-based methods retain a distinct advantage for applications requiring maximal specificity, sensitivity in complex samples, and multiplexing capabilities. The decision to use SYBR Green or a probe-based alternative should be guided by the specific experimental goals, the nature of the target, and the required level of precision.

In the pursuit of reliable biomarkers for cancer research, quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) stands as a fundamental technology for analyzing gene expression. While DNA-binding dye-based methods like SYBR Green provide a cost-effective solution, probe-based detection systems, with TaqMan chemistry being the most prominent, offer a critical advantage: unparalleled specificity. This specificity is paramount when accurately quantifying cancer-associated genes or identifying single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in complex biological samples such as tumor tissues. The TaqMan probe principle, first reported in 1991, relies on the 5´–3´ exonuclease activity of Taq polymerase to cleave a dual-labeled probe during hybridization, enabling fluorophore-based detection [10]. This mechanism, combined with Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET)-based quenching, forms the basis for a highly specific detection system that significantly reduces false-positive signals common in non-specific dye methods [5].

The core components of a TaqMan probe system are an unlabeled primer pair and a dual-labeled oligonucleotide probe. The probe is covalently linked to a fluorophore (reporter dye) at its 5' end and a quencher at its 3' end [10] [11]. Several fluorophores are commonly used, including 6-carboxyfluorescein (FAM) and tetrachlorofluorescein (TET), while the quencher is typically a non-fluorescent molecule such as a Black Hole Quencher (BHQ) or tetramethylrhodamine (TAMRA) [10] [12]. The physical proximity between the fluorophore and quencher when the probe is intact results in quenching of the reporter's fluorescence, primarily through FRET and/or contact quenching mechanisms [13] [12]. FRET is a quantum phenomenon where excitation is transferred from a donor fluorophore to an acceptor quencher through non-radiative dipole-dipole interaction, provided they are within 1-10 nanometers and have sufficient spectral overlap [13]. The efficiency of this energy transfer is inversely proportional to the sixth power of the distance between the donor and acceptor, making it extremely distance-dependent [13] [12].

Mechanism of TaqMan Probes and FRET Quenching

The TaqMan Workflow

The TaqMan detection process is an elegant integration of enzymatic amplification and fluorescent signaling that occurs during the PCR thermal cycling. The mechanism can be broken down into four key stages, illustrated in the diagram below.

- Denaturation: The temperature is raised (typically to 95°C) to separate the double-stranded DNA template into single strands [11].

- Annealing: The temperature is lowered to allow both the forward and reverse primers and the TaqMan probe to anneal to their specific complementary sequences on the template DNA. The probe binds downstream from one of the primers [10] [11].

- Extension and Cleavage: Taq DNA polymerase extends the primer, synthesizing a new DNA strand. When the polymerase reaches the bound TaqMan probe, its 5' to 3' exonuclease activity cleaves the probe [10] [11]. This hydrolysis step is the defining feature of the chemistry.

- Signal Detection: Cleavage of the probe separates the fluorophore from the quencher. Once physically separated, the quencher can no longer suppress the fluorescence of the reporter dye. The fluorophore is now free to emit fluorescence when excited by the real-time PCR instrument's light source [10] [11].

This process repeats in every PCR cycle, leading to an accumulation of fluorescence signal that is directly proportional to the amount of amplified product. The fluorescence is detected in real-time, and the cycle at which the fluorescence crosses a predefined threshold (Ct value) is used for quantitative analysis.

Advanced Quenching Mechanisms

While the core principle involves distance-dependent quenching, the underlying physical mechanisms are nuanced. The quenching in dual-labeled probes operates through two primary pathways, which can occur simultaneously.

- Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET): This is a "through-space" mechanism where energy is transferred from the excited-state fluorophore (donor) to the quencher (acceptor) without photon emission. Efficient FRET requires [13] [12]:

- Proximity: The donor and acceptor must be within approximately 10–100 Å.

- Spectral Overlap: The emission spectrum of the donor must overlap with the absorption spectrum of the acceptor.

- Favorable Orientation: The relative orientation of the donor and acceptor dipoles affects the transfer efficiency.

- Static Quenching (Contact Quenching): This mechanism involves the direct physical contact between the fluorophore and quencher, forming a non-fluorescent ground-state complex or intramolecular dimer. This association is driven by the tendency of hydrophobic, planar dye molecules to stack in an aqueous solution. Static quenching is highly dependent on temperature and solvent conditions [12].

The evolution of quencher technology has been critical to the performance of modern TaqMan assays. Early quenchers like TAMRA were fluorescent themselves, contributing to background noise. The development of dark quenchers like the Black Hole Quencher (BHQ) family, which have broad absorption spectra and no native fluorescence, has significantly improved the signal-to-noise ratio and enabled multiplexing experiments [12]. The following table summarizes the key distinctions between these quenching mechanisms.

Table 1: Comparison of Quenching Mechanisms in Oligonucleotide Probes

| Feature | FRET Quenching | Static Quenching |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanism | Through-space energy transfer | Direct contact and complex formation |

| Physical Contact | Not required | Required |

| Temperature Dependence | Not very temperature sensitive | Decreases with increasing temperature |

| Effect on Absorption Spectrum | Unchanged | Often distorted due to complex formation |

| Dye Pair Example | FAM and TAMRA | FAM and BHQ-1 [12] |

TaqMan vs. SYBR Green: A Quantitative Comparison for Cancer Research

Selecting the appropriate detection chemistry is a critical decision in experimental design. The choice between the probe-based TaqMan method and the dye-based SYBR Green method involves a trade-off between cost, convenience, and specificity.

SYBR Green binds non-specifically to the minor groove of all double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) generated during PCR, leading to a fluorescence increase of over 1,000-fold compared to the unbound state [5]. While this method is relatively cost-effective and easy to use, its major limitation is a lack of inherent specificity; it cannot distinguish between the desired target amplicon and any non-specific PCR products, such as primer-dimers [5]. This can lead to overestimation of the target concentration or false-positive results.

In contrast, TaqMan assays require the specific hybridization of the probe to the target sequence for a fluorescence signal to be generated. This additional layer of specificity ensures that the detected signal originates only from the intended amplicon. This is particularly crucial in cancer research for applications like SNP genotyping, determining viral load, verifying microarray results, and accurately quantifying low-abundance transcripts [10].

Empirical studies directly comparing these methods underscore the performance differences. Research comparing the detection of the enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis (ETBF) bft gene, relevant to colorectal cancer, found that while SYBR Green, TaqMan qPCR, and digital PCR (dPCR) had comparable limits of detection (<1 copy/μl) for purified bacterial DNA, their performance diverged significantly in complex clinical stool samples [9]. SYBR Green qPCR reported only 13 out of 38 samples as positive, whereas TaqMan qPCR and dPCR detected the gene in 35 and 36 samples, respectively. Furthermore, the reported bft copy numbers from TaqMan qPCR and dPCR were 48-fold and 75-fold higher than those from SYBR Green for the same samples, demonstrating SYBR Green's potential for underestimation in the presence of sample-derived inhibitors or background [9].

Another study on adenosine receptor expression in breast cancer tissues found that with high-performance primers and optimized protocols, SYBR Green could produce data comparable to TaqMan, with efficiencies above 95% and significant positive correlations between the methods [5]. This suggests that for well-optimized, single-target assays where non-specific amplification is minimal, SYBR Green can be a valid option.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of SYBR Green vs. TaqMan qPCR

| Parameter | SYBR Green | TaqMan |

|---|---|---|

| Chemistry Basis | Binds to dsDNA minor groove [5] | Sequence-specific hydrolysis probe [10] [5] |

| Specificity | Lower (detects all dsDNA) [5] | Higher (detects only target sequence) [5] [9] |

| Cost | Lower | Higher |

| Ease of Use & Design | Simpler (only primers needed) | More complex (requires probe design) |

| Multiplexing Potential | Not possible | Possible with multiple dye/quencher pairs [11] [12] |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio | Can be high with optimized primers | Typically very high due to dark quenchers [12] |

| Best Application | Single-target gene expression, initial screening | SNP detection, low-abundance targets, multiplexing [10] |

Experimental Protocols and Applications

Detailed Protocol for TaqMan Gene Expression Assay

The following protocol is adapted from methodologies used in studies of adenosine receptor gene expression in breast cancer tissues and the detection of the bft gene [5] [9].

RNA Extraction:

- Homogenize 20-40 mg of frozen tissue (e.g., breast cancer tissue) in a suitable lysis buffer.

- Extract total RNA using a commercial kit (e.g., RNeasy plus mini kit, Qiagen).

- Determine the RNA concentration and purity by measuring UV absorption at 260/280 nm (optimal ratio: ~2.0). Verify RNA integrity by denaturing agarose gel electrophoresis [5].

Reverse Transcription (cDNA Synthesis):

- Use 1 μg of total RNA for reverse transcription.

- Perform the reaction using a commercial reverse transcription kit (e.g., Quantitect Rev. transcription kit, Qiagen) with a mix of random hexamers and oligo-dT primers to ensure comprehensive cDNA representation [5].

Real-Time Quantitative PCR Setup:

- Reaction Mixture (25 μl total volume):

- For TaqMan Assay: 2 μl of cDNA template, 12.5 μl of TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (contains DNA polymerase, dNTPs, and optimized buffer), 1.5 μl of pre-designed primer and probe mix (Assays-on-Demand Gene Expression Products), and nuclease-free water to 25 μl [5] [11].

- For Custom SYBR Green Assay (Comparison): 2 μl of cDNA template, 12.5 μl of SYBR Green Master Mix (e.g., Quantitect SYBR Green master mix, Qiagen), 1.5 μl each of forward and reverse primer (final concentration typically 200-500 nM each), and nuclease-free water to 25 μl [5].

- Include a no-template control (NTC) and a positive control in each run. For absolute quantification, a standard curve of known copy numbers must be included.

- Reaction Mixture (25 μl total volume):

Thermal Cycling Conditions (TaqMan):

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 10 minutes (activates the hot-start polymerase).

- Amplification (40-50 cycles):

- Denature: 95°C for 10-15 seconds.

- Anneal/Extend: 60°C for 20-60 seconds (fluorescence data collection occurs at this step).

- The thermal profile for SYBR Green is similar but typically concludes with a melt curve analysis to check amplicon specificity [5] [9].

Data Analysis:

- The qPCR software will generate a Ct (threshold cycle) value for each reaction.

- For relative gene expression analysis, normalize the Ct of the gene of interest (GOI) to the Ct of a reference gene (e.g., Beta-actin, ACTB) using the ΔΔCt method: ΔCt = Ct(GOI) - Ct(Reference Gene). Fold-change can be calculated as 2^(-ΔΔCt) [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for TaqMan Assays

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Probe-Based Detection

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Example Products |

|---|---|---|

| TaqMan Master Mix | Provides the essential components for PCR: hot-start Taq DNA polymerase, dNTPs, MgCl₂, and optimized reaction buffer. | TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix, TaqMan Genotyping Master Mix [11] [9] |

| Assay-on-Demand | Pre-optimized, ready-to-use primer and probe sets for specific gene targets, saving time on design and validation. | Applied Biosystems TaqMan Gene Expression Assays [5] [11] |

| Custom TaqMan Assays | Tailored primer and probe sets designed for unique targets, such as specific mutations or novel transcripts. | Custom TaqMan SNP Genotyping Assays [11] |

| RNA Extraction Kit | Isolates high-quality, intact total RNA from complex starting materials like tumor tissues. | RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen) [5] [9] |

| Reverse Transcription Kit | Converts RNA template into stable complementary DNA (cDNA) for subsequent PCR amplification. | Quantitect Reverse Transcription Kit [5] |

| Non-Fluorescent Quencher (NFQ) | A dark quencher that minimizes background fluorescence, leading to a higher signal-to-noise ratio. | Minor Groove Binder (MGB)-NFQ probes [11] [12] |

Advanced Applications and Future Directions in Cancer Research

The specificity of TaqMan chemistry has enabled its adaptation for sophisticated applications beyond standard gene expression quantification, playing a critical role in advancing cancer research and molecular diagnostics.

One of the most significant applications is in SNP genotyping and mutation detection. TaqMan genotyping assays utilize two probes, each labeled with a different fluorophore (e.g., FAM and VIC) and specific for one allele of the SNP. The exonuclease activity leads to fluorescence specific to the allele present in the sample, allowing for clear discrimination [11]. This is vital for identifying somatic mutations in oncogenes and tumor suppressors. Furthermore, technologies like competitive allele-specific TaqMan (castPCR) have been developed to enhance the detection of rare mutations in a background of wild-type DNA, a common challenge in liquid biopsy analysis [11]. This method combines allele-specific qPCR with an allele-specific MGB blocker oligonucleotide to effectively suppress nonspecific amplification of the non-target allele, enabling highly sensitive and specific mutation detection [11].

The principles of nucleic acid probe-based detection continue to evolve. Enzymatic methods using CRISPR-Cas systems or Argonaute (Ago) proteins are being developed for point mutation detection with extremely high sensitivity, capable of detecting mutant alleles at frequencies as low as 0.01% [14]. For instance, the PAND (PfAgo-mediated Nucleic Acid Detection) system uses the Pyrococcus furiosus Argonaute protein to cleave target DNA guided by nucleic acids, generating a fluorescent signal and enabling the detection of SNPs in genes like BRCA1, KRAS, and EGFR [14]. Similarly, primer exchange reaction (PER)-based signal amplification strategies have demonstrated the ability to detect cancer-associated single-nucleotide mutations in circulating tumor DNAs (ctDNAs) with a limit of detection down to 27 fM, even discriminating mutant sequences in the presence of a 1000-fold excess of wild-type DNA [15].

These advanced techniques, building upon the foundational principle of probe-based specificity exemplified by TaqMan chemistry, are pushing the boundaries of cancer diagnostics towards earlier detection, minimal residual disease monitoring, and comprehensive profiling of tumor heterogeneity. The workflow below illustrates how these advanced probe-based methods integrate into a comprehensive cancer research pipeline.

Cancer is fundamentally a genetic disease driven by somatic mutations that alter the normal functioning of critical genes. These alterations are categorized into several classes, with oncogenes, tumor suppressor genes, and fusion genes representing the most critical targets for research and therapeutic development. Oncogenes, such as KRAS and EGFR, are mutated forms of normal proto-oncogenes that promote cell growth and division; their activation is typically a gain-of-function event. In contrast, tumor suppressor genes like TP53 normally function to control cell division and repair DNA damage; their inactivation through loss-of-function mutations removes crucial cellular brakes on tumorigenesis. Fusion genes, created by chromosomal rearrangements, can produce chimeric proteins with potent oncogenic activity. The detection and characterization of mutations in these genes have become central to precision oncology, enabling molecular subtyping of tumors and guiding targeted treatment strategies [16] [17].

The efficacy of any detection methodology is paramount, as accurately identifying these genetic alterations directly impacts diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic decisions. This technical guide explores these key genetic targets within the specific context of methodological approaches, particularly comparing SYBR Green versus probe-based detection systems in cancer gene research. Each method offers distinct advantages and limitations in sensitivity, specificity, multiplexing capability, and cost, factors that researchers must carefully balance based on their experimental objectives and resource constraints.

Oncogenes: KRAS and EGFR

KRAS: The Prevalent Oncogene

The Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (KRAS) encodes a small GTPase that functions as a molecular switch, cycling between an active GTP-bound state and an inactive GDP-bound state to regulate cell proliferation, survival, and differentiation [18]. It is the most frequently mutated oncogene in human cancers, with particularly high prevalence in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) (82.1%), colorectal cancer (CRC) (~40%), and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) (21.20%) [19]. Approximately 98% of mutations occur at codons 12, 13, and 61, with G12D (29.19%), G12V (22.17%), and G12C (13.43%) being the most common subtypes [19].

Oncogenic mutations in KRAS impair its GTPase activity or confer resistance to GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs), resulting in constitutive activation of KRAS and sustained downstream signaling through effector pathways like RAF-MEK-ERK and PI3K-AKT-mTOR [19] [18]. This leads to increased cellular survival and proliferation. The G12C mutation, which contains a unique cysteine residue, has been successfully targeted by covalent inhibitors such as sotorasib and adagrasib, approved for treating NSCLC [19] [18]. However, response rates remain around 30-40% with median progression-free survival of approximately 6 months, and resistance mechanisms frequently emerge [19]. Other mutations, like G12D and G12V, currently lack effective targeted therapies, spurring research into novel approaches including pan-KRAS inhibitors, targeted degraders, and RNA-based strategies [18].

EGFR: A Receptor Tyrosine Kinase Oncogene

The Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) is a receptor tyrosine kinase that activates downstream signaling cascades, including the MAPK and PI3K pathways, upon ligand binding. Mutations in EGFR, particularly in NSCLC, lead to constitutive, ligand-independent activation of its kinase domain, driving uncontrolled cell proliferation [20]. Common activating mutations include exon 19 deletions and the L858R point mutation in exon 21. Another critical mutation, T790M, is a major mechanism of resistance to first-generation EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) [14]. Detection of EGFR mutations is essential for initiating targeted therapy with EGFR TKIs and for monitoring the emergence of resistance.

Table 1: Prevalence of Key Oncogene Mutations in Solid Tumors

| Cancer Type | KRAS Mutation Prevalence | Common KRAS Subtypes | EGFR Mutation Prevalence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma | 82.1% | G12D (37.0%), G12V | Not a primary driver |

| Colorectal Cancer (CRC) | ~40% | G12D (12.5%), G12V (8.5%) | Less common |

| Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) | 21.20% | G12C (13.6%) | 23.2% (in Indo-Asian population) [20] |

| Cholangiocarcinoma | 12.7% | Information not specified | Information not specified |

| Uterine Endometrial Carcinoma | 14.1% | Information not specified | Information not specified |

KRAS Signaling Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the KRAS signaling pathway, showing how oncogenic mutations lead to constitutive activation of downstream effectors.

Diagram Title: KRAS Oncogenic Signaling Pathway

Tumor Suppressor Gene: TP53

The TP53 gene encodes the p53 protein, a critical tumor suppressor often dubbed "the guardian of the genome." In response to cellular stress, such as DNA damage, p53 acts as a transcription factor to activate genes that orchestrate cell cycle arrest, DNA repair, senescence, or apoptosis (programmed cell death) [16]. This prevents the propagation of damaged cells and suppresses tumor development.

TP53 is the most frequently mutated gene in human cancer, with alterations occurring in over 50% of all malignancies [20]. Most TP53 mutations are missense mutations that result in a loss of its tumor-suppressive function. Some mutations also confer a "gain-of-function" phenotype, where the mutant p53 protein acquires new oncogenic properties that promote tumor invasion, metastasis, and chemoresistance. In lung cancer, TP53 mutations are among the most common alterations, with a reported frequency of 17.7%, often co-occurring with other driver mutations like EGFR and KRAS [20]. The presence of TP53 mutations is frequently associated with more aggressive disease and poorer prognosis across multiple cancer types.

Fusion Genes in Cancer

Fusion genes are created when chromosomal rearrangements—such as translocations, deletions, or inversions—join parts of two separate genes. This results in a chimeric gene that can produce a fusion protein with oncogenic potential. These aberrant proteins often possess constitutive kinase or transcription factor activity that drives uncontrolled cell growth.

Well-known examples include the BCR-ABL1 fusion in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), the EML4-ALK fusion in a subset of NSCLC, and TMPRSS2-ERG fusions in prostate cancer. The detection of fusion genes is highly clinically relevant, as it can dictate the use of specific targeted therapies, such as ALK inhibitors for EML4-ALK positive NSCLC. Advanced sequencing technologies, particularly RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq), are highly effective for discovering and detecting these chimeric transcripts [17].

Detection Methodologies: SYBR Green vs. Probe-Based Assays

The accurate detection of mutations in genes like KRAS, EGFR, and TP53, as well as fusion genes, is foundational to cancer research and precision medicine. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) is a cornerstone technique for this purpose, primarily utilizing two detection chemistries: SYBR Green and probe-based systems (e.g., TaqMan).

SYBR Green Chemistry

SYBR Green is a fluorescent dye that intercalates non-specifically into the minor groove of double-stranded DNA (dsDNA). The fluorescence signal increases proportionally with the amount of amplified PCR product.

- Principles and Workflow: The dye binds to any dsDNA generated during PCR amplification. After each cycle, fluorescence is measured. Following amplification, a melt curve analysis is performed by gradually increasing the temperature and measuring the decrease in fluorescence. The temperature at which the dsDNA denatures (Tm) is specific to the amplicon's length, GC content, and sequence, allowing for product identification [16] [21].

- Advantages: It is cost-effective as it does not require a specific probe for each target. The same dye can be used for any assay, making it highly flexible. It is well-suited for gene expression analysis and genotyping when followed by melt curve analysis [16].

- Disadvantages: The lack of sequence specificity is a major drawback. SYBR Green will bind to any non-specific amplification product or primer-dimer, potentially leading to false-positive signals and over-quantification. Melt curve analysis adds time to the protocol and may not always adequately distinguish between amplicons with similar Tm values [16].

Probe-Based Chemistry (TaqMan Assays)

TaqMan assays utilize a sequence-specific oligonucleotide probe labeled with a fluorescent reporter dye at one end and a quencher molecule at the other.

- Principles and Workflow: The probe hybridizes to a specific sequence within the target amplicon. During PCR, the 5' to 3' exonuclease activity of the Taq polymerase cleaves the probe, separating the reporter from the quencher and generating a fluorescent signal. The fluorescence intensity is directly proportional to the amount of probe cleased, and thus, to the amount of target amplified [16].

- Advantages: This method offers superior specificity and reliability because fluorescence is generated only if the specific probe sequence is amplified. It allows for multiplexing—the simultaneous detection of multiple targets in a single reaction by using probes labeled with different reporter dyes. This is crucial for detecting single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) or multiple mutation types from a single sample [14] [16].

- Disadvantages: Probe-based assays are more expensive to design and synthesize. Each target requires a unique, optimized probe, reducing flexibility. The presence of a probe can sometimes slightly reduce amplification efficiency [16].

Comparison for Cancer Gene Detection

For detecting critical cancer mutations, the high specificity of probe-based assays makes them the preferred choice for clinical validation and diagnostic applications. Their ability to distinguish single-nucleotide changes, such as the G12D versus G12V mutation in KRAS, is essential. The multiplexing capability is also vital for efficient profiling of multiple mutation hotspots from limited patient material.

SYBR Green-based assays, while more affordable and flexible, are generally more suitable for initial screening or research applications where absolute specificity is less critical, provided that primer design is highly optimized and melt curve analysis can reliably distinguish between amplicons.

Table 2: Comparison of SYBR Green vs. Probe-Based qPCR Detection Methods

| Feature | SYBR Green | Probe-Based (e.g., TaqMan) |

|---|---|---|

| Principle | Intercalates into any dsDNA | Sequence-specific hybridization and cleavage |

| Specificity | Lower; relies on primers and melt curve | Very High; requires exact probe match [16] |

| Multiplexing | Not possible in a single tube | Yes; with different fluorescent dyes [16] |

| Cost | Lower (universal dye) | Higher (custom probe required) |

| Best For | Gene expression, initial screening, genotyping with clear Tm differences | SNP detection, mutation screening, multiplex assays [14] [16] |

| Sensitivity | Can be compromised by primer-dimers | High and more reliable [21] |

Advanced Detection Technologies and Workflows

While qPCR is a workhorse for targeted detection, advanced technologies are employed for broader genomic profiling. Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) allows for the parallel sequencing of millions of DNA fragments, providing a comprehensive view of mutations, copy number variations, and gene fusions across hundreds of genes simultaneously [17]. It is becoming the standard of care for patients with advanced solid tumors.

Emerging methods are also showing significant promise. CRISPR-Cas systems can be harnessed for mutation detection. For example, the DASH (Depletion of Abundant Sequences by Hybridization) method uses Cas9 to selectively cleave wild-type sequences, enriching mutant alleles for subsequent detection with sensitivity as low as 0.1% [14]. Similarly, Argonaute (Ago) proteins, such as PfAgo, can be programmed with guide strands to specifically cleave nucleic acids, enabling the development of highly sensitive detection platforms like PAND and NAVIGATER, the latter achieving a detection limit of 0.01% for mutations in liquid biopsies [14].

Furthermore, Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS) is being explored as a label-free method to detect epigenetic modifications like DNA methylation, which are also crucial in cancer. A 2025 study identified a SERS band at 790 cm⁻¹ that strongly correlated with 5-methylcytosine levels, demonstrating its potential for cancer diagnosis [22].

Another groundbreaking development is the use of Artificial Intelligence (AI). The SEQUOIA AI tool can predict the activity of thousands of genes, including established cancer gene signatures, directly from standard histopathology biopsy images [23]. This approach could potentially infer genetic alterations from routine images, reducing the need for costly genetic tests.

Experimental Protocol: Detection of a KRAS Point Mutation using SYBR Green qPCR with Melt Curve Analysis

The following workflow outlines a standard protocol for detecting a specific KRAS mutation, such as G12C, using SYBR Green-based qPCR.

Diagram Title: SYBR Green qPCR Workflow for Mutation Detection

Detailed Protocol Steps:

- DNA Extraction and Quantification: Extract high-quality genomic DNA from patient samples (e.g., formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue or circulating tumor DNA from blood). Precisely quantify the DNA using a spectrophotometer or fluorometer [16] [21].

- Primer Design: Design primers that flank the mutation site of interest (e.g., codon 12 of KRAS). Primers should be 18-22 bases long with a Tm of 58-60°C and a GC content of 40-60%. To ensure amplification of cDNA only (and not genomic DNA contamination), design primers to span an exon-exon junction if possible [16].

- qPCR Reaction Setup:

- Prepare a reaction mix containing: 1x SYBR Green Master Mix (containing DNA polymerase, dNTPs, Mg²⁺, and SYBR Green dye), forward and reverse primers (typically 0.2-0.5 µM each), and template DNA (10-100 ng) [21].

- Include no-template controls (NTC) to check for contamination and positive controls (wild-type and known mutant DNA) for calibration.

- Thermal Cycling: Run the qPCR protocol with the following steps:

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 5-10 minutes.

- Amplification (40-50 cycles):

- Denaturation: 95°C for 15-30 seconds.

- Annealing: 60°C (or optimized Tm) for 30-60 seconds.

- Extension: 72°C for 30-60 seconds. Fluorescence data is acquired at the end of this step.

- Melt Curve Analysis: After cycling, run the melt curve protocol:

- Gradually increase the temperature from 60°C to 95°C (e.g., 0.3°C increments) while continuously monitoring fluorescence.

- Plot the negative derivative of fluorescence versus temperature (-dF/dT vs. T) to generate distinct melt peaks.

- Data Interpretation: The cycle threshold (Ct) indicates the initial quantity of the target. The melt peak Tm is used for genotyping. A single peak at the wild-type Tm indicates a wild-type sample. A single peak at a lower Tm indicates a homozygous mutant. Two distinct peaks indicate a heterozygous sample containing both wild-type and mutant alleles [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Cancer Gene Detection Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| SYBR Green Master Mix | Provides all components for dsDNA detection in qPCR; enables melt curve analysis. | Gene expression profiling; initial screening for genetic alterations [16]. |

| TaqMan Probe Assays | Provide sequence-specific detection for SNPs and mutations in multiplex qPCR. | Differentiating between KRAS G12D and G12V mutations; EGFR T790M detection [14] [16]. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Panels | High-throughput, parallel sequencing of multiple cancer-related genes from a single sample. | Comprehensive genomic profiling of solid tumors; identifying co-mutations in TP53 and KRAS [17]. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 System (e.g., DASH) | Programmable nuclease for selective depletion of wild-type sequences to enrich mutant alleles. | Enriching low-abundance KRAS mutations in a background of wild-type DNA prior to sequencing [14]. |

| Argonaute Proteins (e.g., PfAgo, TtAgo) | Nucleic acid-guided nucleases for highly specific cleavage and detection of mutant sequences. | Ultra-sensitive detection of KRAS G12D or EGFR T790M in liquid biopsy samples [14]. |

| SERS Substrates (e.g., Silver Nanoparticles) | Plasmonic nanoparticles for label-free, enhanced spectroscopic detection of molecular structures. | Detecting global DNA methylation levels via 5-methylcytosine-associated SERS bands [22]. |

Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (qPCR) stands as a cornerstone technology in molecular biology, providing researchers with a powerful tool for quantifying nucleic acids with exceptional sensitivity and speed. In modern cancer biomarker analysis, qPCR has evolved beyond traditional gene expression studies to become an indispensable technology for liquid biopsy applications, enabling non-invasive cancer detection, prognosis, and treatment monitoring. The method's capacity to detect as little as a single copy of a target sequence makes it particularly valuable for analyzing scarce targets such as circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) and microRNAs (miRNAs) found in biological fluids [24] [25]. This technical guide explores the fundamental principles, applications, and methodological considerations of qPCR in cancer research, with particular emphasis on the critical comparison between SYBR Green and probe-based detection systems within the context of cancer gene analysis.

The integration of qPCR into liquid biopsy workflows has transformed cancer diagnostics by providing minimally invasive alternatives to traditional tissue biopsies. Liquid biopsy focuses on detecting cancer biomarkers in bodily fluids such as blood, urine, and saliva, offering real-time insights into tumor biology [26]. These biomarkers include circulating tumor cells (CTCs), ctDNA, miRNAs, and exosomes, all of which can be quantified using qPCR technologies [26]. As cancer remains a leading cause of mortality worldwide, with over 10 million deaths annually [25], the development of rapid, sensitive, and specific diagnostic tools is paramount for improving patient outcomes through early detection and personalized treatment strategies.

Fundamental Principles of qPCR Detection Chemistry

Basic qPCR Mechanism and Fluorescence Detection

qPCR operates on the principle of detecting fluorescence signals that increase proportionally with the amount of amplified DNA during PCR cycles. The process involves four distinct phases: linear ground phase, early exponential phase, linear exponential phase (log phase), and plateau phase [24]. The cycle threshold (Ct) value, determined during the early exponential phase when the fluorescence signal rises above background levels, provides the quantitative measurement used to determine initial template concentration [24]. Lower Ct values indicate higher initial target concentrations, enabling precise quantification of nucleic acid targets across a wide dynamic range.

The fundamental workflow of qPCR begins with template preparation, followed by thermal cycling that includes denaturation, annealing, and extension steps. During amplification, the fluorescence signal is monitored in real-time, generating amplification curves that can be analyzed to determine the starting quantity of the target sequence. This process requires essential components including: DNA or cDNA template, thermostable DNA polymerase, primers, dNTPs, MgCl2, buffer, and a fluorescent reporter molecule [24].

Comparison of Detection Chemistries

Table 1: Comparison of SYBR Green vs. Probe-Based qPCR Detection Methods

| Parameter | SYBR Green (Dye-Based) | Probe-Based (TaqMan) |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Mechanism | Binds nonspecifically to double-stranded DNA | Sequence-specific probe hydrolysis or hybridization |

| Specificity | Lower - detects all dsDNA including primer dimers | Higher - only detects specific target sequence |

| Multiplexing Capability | No - single target per reaction | Yes - multiple targets with different fluorophores |

| Cost Considerations | Lower cost - requires only primers | Higher cost - requires labeled probes |

| Workflow Complexity | Simple primer design and optimization | Complex probe and primer design |

| Background Fluorescence | Higher background signal | Lower background fluorescence |

| Post-PCR Verification | Requires melting curve analysis | Not required |

| Best Applications | Gene expression screening, target validation | SNP genotyping, pathogen detection, multiplex assays |

Visualization of qPCR Detection Mechanisms

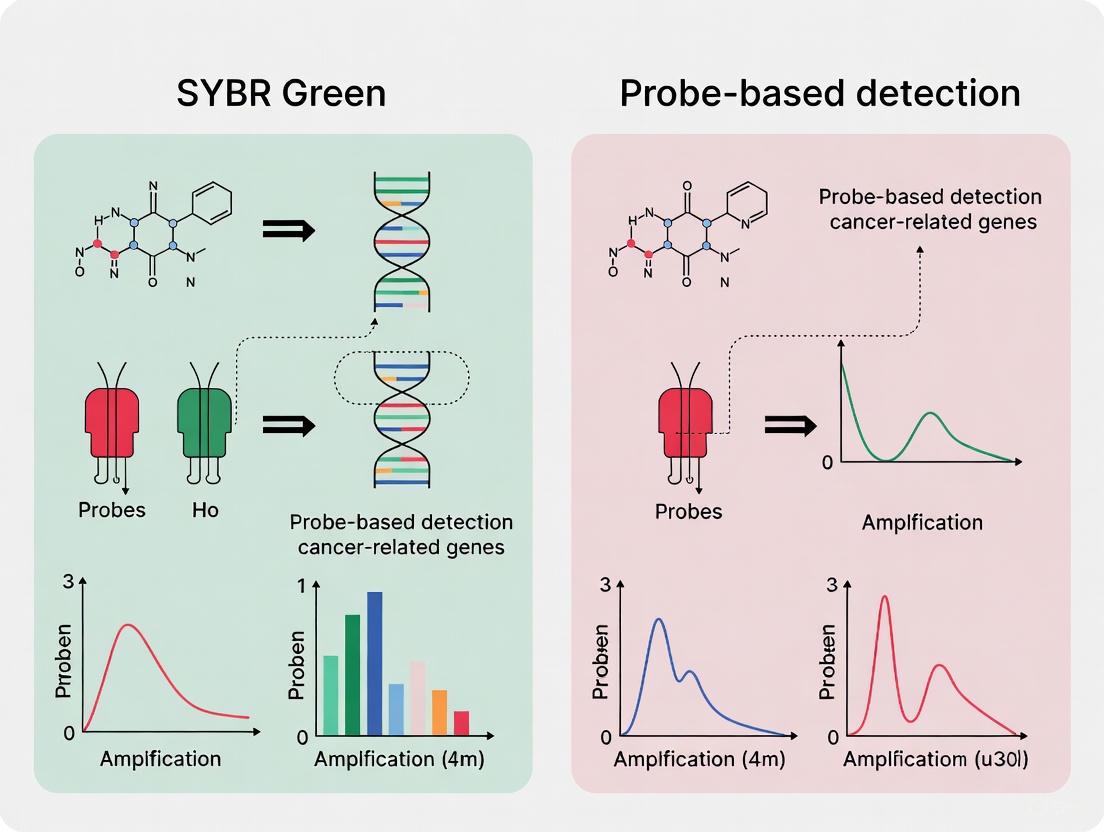

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental differences in detection mechanisms between SYBR Green and probe-based qPCR approaches:

Probe-Based qPCR Assays: Mechanisms and Applications

TaqMan Probe Chemistry and Variants

Probe-based qPCR relies on the 5'→3' exonuclease activity of Taq DNA polymerase and sequence-specific oligonucleotide probes labeled with reporter and quencher dyes [24]. The most common implementation, TaqMan technology, utilizes dual-labeled probes with a reporter dye at the 5' end and a quencher dye at the 3' end. When the probe is intact, fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) occurs, with the quencher absorbing the light emitted by the reporter [24]. During amplification, the probe binds to the template, and Taq DNA polymerase cleaves the probe via its 5'→3' exonuclease activity, separating the reporter from the quencher and resulting in fluorescence emission [24].

Advanced probe variants include TaqMan minor groove binder (MGB) probes, which incorporate a nonfluorescent quencher and MGB molecule at the 3' end that stabilizes the probe-DNA complex by folding into the minor groove of double-stranded DNA [24]. This enhancement allows for shorter probe designs and improved discrimination of single-base mismatches, particularly valuable for SNP genotyping and mutation detection in cancer research.

Key Applications in Cancer Biomarker Analysis

SNP Genotyping

Probe-based qPCR enables accurate single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) genotyping, which is crucial for identifying genetic variations associated with cancer susceptibility and treatment response. This approach utilizes allele-specific probes with different reporter dyes (e.g., FAM-labeled for allele 1 and VIC-labeled for allele 2) [24]. The assay capitalizes on the fact that probes with mismatched bases at the SNP position bind unstably and resist cleavage, preventing fluorescence emission. This permits precise allele discrimination in large population studies with high throughput, accuracy, and cost-effectiveness [24].

DNA Methylation Analysis

DNA methylation plays a critical role in gene silencing and carcinogenesis. Probe-based qPCR facilitates methylation-specific analysis after bisulfite treatment of DNA, which converts unmethylated cytosines to uracils while leaving methylated cytosines unchanged [24]. The method employs primers and probes designed to distinguish methylated from unmethylated alleles, enabling quantification of methylation status at specific genomic loci. This application has significant implications for cancer epigenetics, early detection, and monitoring of epigenetic therapies [27] [28].

miRNA Quantification

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small non-coding RNA molecules (18-28 nucleotides) that regulate gene expression and serve as promising biomarkers for cancer diagnosis and prognosis [25]. Probe-based qPCR offers superior specificity for miRNA detection compared to dye-based methods, addressing challenges related to their short length, high sequence similarity among family members, and low abundance in biological fluids [25]. Specialized stem-loop primers enhance specificity by trapping and annealing to the 3' end of mature miRNA, followed by probe binding to the stem-loop sequence [24].

Viral Detection in Cancer

Probe-based qPCR serves as a gold standard for detecting oncogenic viruses such as Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), which is associated with lymphomas, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, and gastric cancers [27]. Methylation-specific PCR assays for viral promoters (e.g., MSPCP for EBV C promoter) can distinguish latent from lytic viral states, providing diagnostic and prognostic information in virus-associated malignancies [27].

SYBR Green qPCR: Principles and Implementation

Mechanism and Workflow Considerations

SYBR Green-based qPCR utilizes an intercalating dye that binds nonspecifically to the minor groove of double-stranded DNA, experiencing a 20-100 fold increase in fluorescence upon DNA binding [24]. This method offers simplicity and cost-effectiveness, requiring only the addition of PCR primers without the need for specialized probes [29]. The straightforward design process makes it particularly suitable for initial screening applications and target validation studies in cancer research.

A critical requirement for SYBR Green assays is post-amplification melting curve analysis to distinguish specific products from nonspecific amplification such as primer dimers [29]. This verification step involves gradually increasing temperature while monitoring fluorescence to generate dissociation curves based on the melting temperature (Tm) of amplified products, with specific amplicons exhibiting characteristic Tm values distinct from artifacts.

Advantages and Limitations in Cancer Research

The primary advantage of SYBR Green chemistry is its cost-effectiveness, as it eliminates the expense of fluorescently-labeled probes [30] [29]. This makes it ideal for large-scale screening studies where multiple targets need validation across numerous samples. The simplicity of assay design and optimization also reduces development time, particularly when investigating novel cancer biomarkers with limited sequence information.

However, SYBR Green has significant limitations for complex cancer biomarker applications. Its nonspecific binding to any double-stranded DNA can lead to inaccurate quantification due to off-target amplification and primer dimer formation [29]. This reduced specificity is particularly problematic when analyzing low-abundance targets in complex biological samples like plasma or serum. Additionally, the inability to perform multiplex reactions restricts researchers to single-analyte detection per reaction, limiting throughput for comprehensive biomarker panels [29].

qPCR in Liquid Biopsy Applications

Circulating Tumor DNA (ctDNA) Analysis

Liquid biopsy represents a transformative approach in cancer diagnostics, with qPCR playing a pivotal role in detecting and quantifying ctDNA—short DNA fragments released into circulation by tumor cells [26]. ctDNA typically comprises 0.1-1.0% of total cell-free DNA (cfDNA) in cancer patients and carries tumor-specific genetic alterations including point mutations, copy number variations, and epigenetic modifications [26]. Probe-based qPCR methods like droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) offer exceptional sensitivity for detecting rare mutant alleles in background wild-type DNA, enabling applications in early cancer detection, minimal residual disease (MRD) monitoring, and therapy response assessment [31].

The VICTORI study in colorectal cancer demonstrated the clinical utility of ctDNA analysis, where 87% of recurrences were preceded by ctDNA positivity, while no ctDNA-negative patients relapsed [31]. Similarly, the TOMBOLA trial compared ddPCR and whole-genome sequencing for ctDNA detection in bladder cancer, showing 82.9% concordance between methods with ddPCR exhibiting higher sensitivity in low tumor fraction samples [31].

Advanced Methodologies in Liquid Biopsy

Table 2: qPCR Applications in Liquid Biopsy for Cancer Management

| Application Area | Specific Use Case | qPCR Methodology | Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-Cancer Early Detection | DNA methylation profiling of cfDNA | Methylation-specific probe-based qPCR | 88.2% top prediction accuracy for cancer signal origin [31] |

| Minimal Residual Disease (MRD) | Post-surgical recurrence risk stratification | ddPCR and targeted qPCR panels | 94.3% ctDNA positivity in treatment-naive colorectal cancer patients [31] |

| Treatment Response Monitoring | EGFR mutation detection in NSCLC | Probe-based qPCR (TaqMan) | Baseline EGFR detection in plasma prognostic for shorter PFS and OS [31] |

| Virus-Associated Cancers | EBV-associated lymphoma detection | Methylation-specific PCR for EBV C promoter | High methylation (94-100%) in tumors vs. low methylation in healthy controls [27] |

Workflow for Liquid Biopsy Analysis Using qPCR

The following diagram illustrates a standardized workflow for processing liquid biopsy samples using qPCR technologies:

Experimental Protocols for Key Applications

Methylation-Specific qPCR for Cancer Detection

DNA methylation analysis via qPCR provides crucial information for cancer diagnosis and prognosis. The following protocol outlines methylation-specific PCR for detecting promoter hypermethylation in cancer biomarkers:

Sample Preparation:

- Extract cell-free DNA from 1-4 mL plasma using commercial kits (e.g., QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit)

- Treat 500 ng - 1 μg DNA with sodium bisulfite using commercial conversion kits (e.g., EZ DNA Methylation Kit)

- Purify bisulfite-converted DNA and elute in 20-40 μL elution buffer

Primer and Probe Design:

- Design methylation-specific primers to amplify regions of interest with 3-5 CpG sites in binding regions

- Ensure primers specifically recognize bisulfite-converted sequences with converted Cs at non-CpG positions

- Design TaqMan probes with reporter-quencher pairs (FAM-BHQ1 for methylated alleles, VIC-BHQ2 for unmethylated alleles)

- Validate primer specificity using in silico tools and control samples

qPCR Reaction Setup:

- 10 μL TaqMan Universal Master Mix II

- 1 μL bisulfite-converted DNA template (5-10 ng/μL)

- 0.5 μL each forward and reverse primer (10 μM stock)

- 0.5 μL TaqMan probe (5 μM stock)

- Nuclease-free water to 20 μL final volume

Thermal Cycling Conditions:

- Initial denaturation: 95°C for 10 minutes

- 45 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 15 seconds

- Annealing/Extension: 60°C for 60 seconds (with fluorescence acquisition)

Data Analysis:

- Calculate ΔCt values between methylated and unmethylated signals

- Determine methylation ratios using standard curves or ΔΔCt methods

- Establish threshold values for positive methylation calls based on control samples

This protocol has been successfully applied to detect EBV C promoter methylation in Hodgkin lymphoma, showing 94-100% methylation in tumor tissues versus minimal methylation in controls [27].

miRNA Quantification Using Stem-Loop qPCR

Mature miRNA quantification requires specialized approaches due to their short length. The stem-loop RT-qPCR method provides enhanced specificity and sensitivity:

RNA Extraction:

- Extract total RNA from 200-500 μL plasma using miRNA-specific kits (e.g., miRNeasy Serum/Plasma Kit)

- Include spike-in synthetic miRNA controls for normalization

- Elute RNA in 15-30 μL nuclease-free water

Stem-Loop Reverse Transcription:

- Design stem-loop RT primers with:

- 3' portion complementary to 6-8 nucleotides at miRNA 3' end

- Stem-loop structure

- Universal sequence at 5' end

- Prepare RT reaction:

- 1-5 μL RNA template

- 1 μL stem-loop RT primer (1 μM)

- 4 μL 5× Reverse Transcription Buffer

- 0.5 μL dNTPs (100 mM)

- 1 μL Reverse Transcriptase

- Nuclease-free water to 20 μL

- Incubate at 16°C for 30 minutes, 42°C for 30 minutes, 85°C for 5 minutes

qPCR Amplification:

- Design forward primer complementary to miRNA 5' region

- Use universal reverse primer complementary to stem-loop sequence

- Utilize TaqMan probe with FAM reporter and BHQ-1 quencher

- Prepare qPCR reaction:

- 10 μL TaqMan Master Mix

- 1 μL cDNA template

- 0.5 μL forward primer (10 μM)

- 0.5 μL reverse primer (10 μM)

- 0.5 μL TaqMan probe (5 μM)

- Nuclease-free water to 20 μL

- Thermal cycling: 95°C for 10 minutes, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 seconds and 60°C for 60 seconds

This approach enables specific detection of mature miRNA forms, which is crucial given their role as regulatory molecules in cancer pathways [24] [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Technologies

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for qPCR Cancer Biomarker Analysis

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in qPCR Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent Reporters | SYBR Green I, FAM, VIC, TET, TAMRA | Detection of amplified products through fluorescence emission |

| Quenchers | BHQ (Black Hole Quencher), TAMRA | Suppress reporter fluorescence until amplification occurs |

| Specialized Probes | TaqMan dual-labeled probes, MGB probes, Molecular Beacons | Provide sequence-specific detection with enhanced specificity |

| DNA Polymerases | Hot-start Taq, Reverse Transcriptase | Catalyze DNA amplification with reduced non-specific amplification |

| Sample Preparation Kits | QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit, miRNeasy Serum/Plasma Kit | Isolate high-quality nucleic acids from complex biological samples |

| Bisulfite Conversion Kits | EZ DNA Methylation Kit, MethylEdge Bisulfite Conversion System | Convert unmethylated cytosines to uracils for methylation analysis |

| Reference Assays | RNAse P detection, Reference genes (GAPDH, ACTB) | Normalize sample input and control for extraction efficiency |

Emerging Trends and Future Perspectives

The field of qPCR in cancer biomarker analysis continues to evolve with several emerging trends shaping its future applications. Amplification-free detection technologies are gaining attention for miRNA analysis, addressing limitations of PCR-based methods including labor-intensive workflows, technical variability, and difficulties in quantifying low-abundance targets [25]. These approaches aim to enable direct miRNA interrogation without RNA extraction, reverse transcription, or amplification, potentially improving reliability and scalability for clinical applications [25].

Multiplexing capabilities are expanding through advanced probe systems and digital PCR platforms, allowing simultaneous quantification of multiple biomarkers from limited sample volumes. The development of novel CRISPR-based detection methods like MUTE-Seq (Mutation tagging by CRISPR-based Ultra-precise Targeted Elimination in Sequencing) enables ultrasensitive detection of low-frequency mutations in ctDNA by selectively eliminating wild-type DNA [31]. Such innovations significantly enhance sensitivity for minimal residual disease monitoring.

Integration of multi-analyte approaches represents another frontier, combining ctDNA mutation analysis with methylation profiling, fragmentomics, and protein biomarkers to improve diagnostic accuracy [31]. Studies demonstrate that combining tissue and liquid biopsy significantly increases detection of actionable alterations and improves survival outcomes in patients receiving tailored therapy, despite only 49% concordance between methods [31].

As these technological advances continue to mature, qPCR remains positioned as a fundamental tool in cancer biomarker research, bridging the gap between basic science discovery and clinical application through its unique combination of sensitivity, quantitative accuracy, and practical implementation across diverse laboratory settings.

Application in Oncology: Protocols for Detecting Cancer Biomarkers and Mutations

Designing Primers and Probes for Cancer-Associated SNPs and Point Mutations

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) is a cornerstone technique in molecular diagnostics and cancer research, enabling the sensitive detection and quantification of genetic alterations such as single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and point mutations. These somatic mutations can act as drivers of oncogenesis, influence therapeutic responses, and serve as biomarkers for minimal residual disease monitoring [32]. The choice between intercalating dye-based methods (e.g., SYBR Green) and probe-based methods (e.g., TaqMan) represents a critical decision point in assay design, with significant implications for specificity, cost, throughput, and robustness [5]. This guide provides an in-depth technical framework for designing primers and probes to detect cancer-associated mutations, contextualized within the comparative performance of SYBR Green and TaqMan chemistries. The principles outlined support applications in research, diagnostic assay development, and therapeutic monitoring for oncology.

SYBR Green vs. TaqMan: Core Principles and Comparative Analysis

Chemistry and Mechanism

SYBR Green is a fluorescent dye that binds non-specifically to the minor groove of double-stranded DNA (dsDNA). During qPCR, the fluorescence increases proportionally to the amount of amplified dsDNA product, allowing for quantification [5]. Its primary advantage is simplicity and cost-effectiveness, as it requires only sequence-specific primers. However, a significant limitation is its inability to distinguish between specific and non-specific amplification products (e.g., primer-dimers), which can lead to false-positive signals [5] [33]. Post-amplification melting curve analysis is, therefore, essential to verify amplicon specificity.

TaqMan Probes (Hydrolysis Probes) rely on a sequence-specific, dual-labeled oligonucleotide probe in addition to PCR primers. The probe is conjugated with a fluorescent reporter dye at the 5' end and a quencher dye at the 3' end. When intact, the quencher suppresses the reporter's fluorescence via Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET). During the amplification cycle, the 5'→3' exonuclease activity of the DNA polymerase cleaves the probe, physically separating the reporter from the quencher and resulting in a permanent fluorescent signal proportional to the target amplification [5]. This mechanism provides inherent specificity, as fluorescence is generated only upon hybridization and cleavage of the correct probe.

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The following table summarizes key performance characteristics of SYBR Green and TaqMan assays as demonstrated in various studies.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of SYBR Green and TaqMan qPCR Methods

| Parameter | SYBR Green | TaqMan | Context and Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Assay Efficiency | 94.3% - 99% [8] [34] | 96.6% - 103% [8] [34] | Efficiencies >90% are generally acceptable. Both methods can achieve high, comparable efficiency with proper optimization [5]. |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | 100 fg - 102 copies/μL [8] [34] | 10 fg - 101 copies/μL [8] [34] | TaqMan often demonstrates a 1-log improved sensitivity due to reduced background signal. |

| Specificity | High, but dependent on primer specificity and requires melting curve analysis [33]. | Very High, conferred by the sequence-specific probe [5]. | SYBR Green can detect 100% of viral sequence variants in one study, whereas TaqMan failed to detect 47% of single-nucleotide variants in its probe-binding site [33]. |

| Cost & Accessibility | Relatively low cost and easy design [5]. | More expensive due to probe synthesis [5]. | SYBR Green is economical for primer screening and assays where target sequence is highly conserved. |

| Multiplexing Potential | None. | High. Enables detection of multiple targets in a single reaction using probes with different fluorophores. | Critical for assays like internal controls or simultaneous detection of a mutation and a reference gene. |

| Impact on HER2 Gene Dose Analysis | Underestimated amplification ratio (5-fold vs. 10-fold) [35]. | Correctly estimated 10-fold amplification [35]. | For gene copy number variation (CNV) analysis, probe-based methods are generally more accurate [35]. |

Primer and Probe Design for SNP and Point Mutation Detection

The accurate detection of single-base changes demands rigorous in silico design and experimental validation.

General Design Parameters

- Amplicon Length: Shorter amplicons (80-200 bp) typically yield higher amplification efficiencies and are more robust when analyzing degraded DNA from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples [36].

- Primer Characteristics: Primers should be 18-25 nucleotides long with a melting temperature (Tm) of 50-65°C. The Tm of both primers in a pair should be within 1-2°C of each other. Avoid long runs of identical nucleotides, secondary structures, and 3'-complementarity to prevent primer-dimer formation.

- Specificity Checking: Use tools like NCBI Primer-BLAST to ensure primers are specific to the intended genomic target and do not amplify homologous sequences or pseudogenes [37].

- Exon-Junction Spanning: When detecting mRNA expression, designing at least one primer to span an exon-exon junction prevents amplification of contaminating genomic DNA [37].

Allele-Specific Primer Design for SNP Genotyping

Allele-Specific PCR (AS-PCR) differentiates alleles based on the preferential amplification by a primer whose 3'-terminal nucleotide is complementary to one allele (e.g., wild-type vs. mutant). To enhance specificity, an additional, deliberate mismatch is often introduced near the 3' end of the allele-specific primer.

Table 2: Strategy for Introducing Artificial Mismatches in Allele-Specific Primers

| SNP Type | Recommended Artificial Mismatch (Base Pair & Position) | Reported Specificity | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| A/T (or T/A) | C-A in the 3rd nucleotide from the 3' end [38]. | 81.9% [38] | This specific transversion creates a strong destabilizing effect that efficiently suppresses amplification of the non-matched template. |

| A/G (or T/C) | T-G or C-A in the 3rd position from the 3' end [38]. | Found to be effective [38]. | These transversions provide sufficient thermodynamic discrimination. |

| A/C (or T/G) | A-G (transition) in the 2nd position from the 3' end [38]. | Effective for improving specificity [38]. | Positioning the mismatch closer to the terminal base increases its discriminatory power. |

| G/C (or C/G) | Mismatch in the 2nd position from the 3' end [38]. | 43% polymorphism rate [38]. | Systematic testing of mismatch position is critical for these SNP types. |

TaqMan Probe Design for Mutation Detection

- Probe Placement: Design the probe to hybridize to the stable, conserved region of the amplicon. For SNP detection, the polymorphic site should be located centrally within the probe sequence to maximize allelic discrimination.

- Probe Characteristics: The probe should have a Tm 5-10°C higher than the primers to ensure it hybridizes before primer extension. Length is typically 15-30 nucleotides.

- Fluorophore-Quencher Selection: Choose reporter dyes (e.g., FAM, VIC) and quenchers (e.g., BHQ, TAMRA) based on the real-time PCR instrument's channels. For multiplexing, ensure the emission spectra of reporters are well-separated.

Diagram Title: Workflow for Designing qPCR Assays for Cancer Mutations

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Protocol: Assay Optimization and Efficiency Calculation

- Standard Curve Preparation: Prepare a serial dilution (e.g., 5- or 10-fold) of the target template (e.g., plasmid DNA or cDNA with known concentration) over a range of at least 5 orders of magnitude.

- qPCR Run: Perform qPCR using both the optimized primer set (for SYBR Green) and the primer-probe set (for TaqMan) with the standard curve dilutions.

- Efficiency Calculation: The qPCR software plots the Cycle Threshold (Ct) values against the logarithm of the template concentration. The slope of the resulting standard curve is used to calculate the amplification efficiency (E) using the formula:

Protocol: Analytical Validation for Diagnostic Sensitivity

- Limit of Detection (LOD) Determination: Perform qPCR on a dilution series of the target mutation in a background of wild-type DNA (e.g., cell line DNA or synthetic fragments). The LOD is the lowest concentration at which the target is detected in ≥95% of replicates [39] [36].

- Specificity Testing: Test the assay against a panel of samples with known genotypes, including wild-type, heterozygous, and homozygous mutant, to confirm that the signal is generated only from the intended allele.

- Analysis of Variant Tolerance: As demonstrated in viral studies, test the assay against known sequence variants to ensure that mismatches do not lead to false negatives, a particular advantage of the SYBR Green method for evolving targets [33].

Table 3: Key Reagents and Resources for Mutation Detection Assays

| Item | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Enzyme for accurate amplification of templates for cloning standards. | Generation of plasmid DNA for standard curves [34]. |

| Hot-Start Taq Polymerase | Reduces non-specific amplification and primer-dimer formation by requiring thermal activation. | Essential for both SYBR Green and TaqMan assays to improve specificity and sensitivity [36]. |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Molecular barcodes added to each template molecule before amplification. | Allows bioinformatic removal of PCR duplicates and errors, improving quantification accuracy in NGS-based assays [36]. |

| Nicking Enzyme Amplification Reaction (NEAR) | Isothermal amplification method for rapid target enrichment. | Used in novel methods like SPEAR for ultra-sensitive SNP detection without traditional PCR [39]. |

| CRISPR-Cas12b RNP | Ribonucleoprotein complex for sequence-specific recognition and cleavage. | Provides single-base resolution specificity in conjunction with isothermal amplification for detecting cancer SNPs [39]. |

| Panel of Normal (PON) Samples | A collection of sequencing data from normal, non-tumor samples. | Serves as a baseline reference in NGS pipelines to filter out sequencing artifacts and common germline variants [36]. |

Diagram Title: Method Selection Guide for Mutation Detection

The strategic design of primers and probes is fundamental to the success of any qPCR-based assay for cancer-associated SNPs and point mutations. The choice between SYBR Green and TaqMan methodologies is not a matter of superiority but of application-specific suitability. SYBR Green offers a cost-effective and flexible solution for gene expression studies and variant scanning, especially when the target region is prone to sequence variations that could compromise probe binding [33]. In contrast, TaqMan probes provide an unparalleled level of specificity and are the gold standard for high-fidelity diagnostic applications, multiplexing, and accurate copy number analysis [35] [32]. Emerging technologies like CRISPR-Cas-assisted methods (e.g., SPEAR) further push the boundaries of sensitivity and speed for point mutation detection [39]. By adhering to the detailed design rules, validation protocols, and selection framework outlined in this guide, researchers and clinical developers can implement robust, reliable genomic tools to advance cancer research and precision medicine.

Workflow for Absolute Quantification of Viral Loads and Gene Copy Number Variations (e.g., MYC-N amplification)

Absolute quantification is a cornerstone of molecular diagnostics, providing precise measurement of specific nucleic acid sequences within a biological sample. In the context of cancer research and virology, this capability is indispensable for assessing oncogene amplification status, such as MYC-N in neuroblastoma, or determining viral load for disease monitoring. The choice between SYBR Green and probe-based detection methods represents a critical methodological crossroads, each offering distinct advantages and limitations that significantly impact assay design, cost, specificity, and data interpretation [40] [41] [42]. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of workflows for absolute quantification of viral loads and gene copy number variations (CNVs), with particular emphasis on the comparative analytical considerations between fluorescent DNA-binding dyes and hydrolysis probes within cancer gene research frameworks.