Structure-Based vs. Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling: A Comprehensive Guide for Effective Drug Discovery

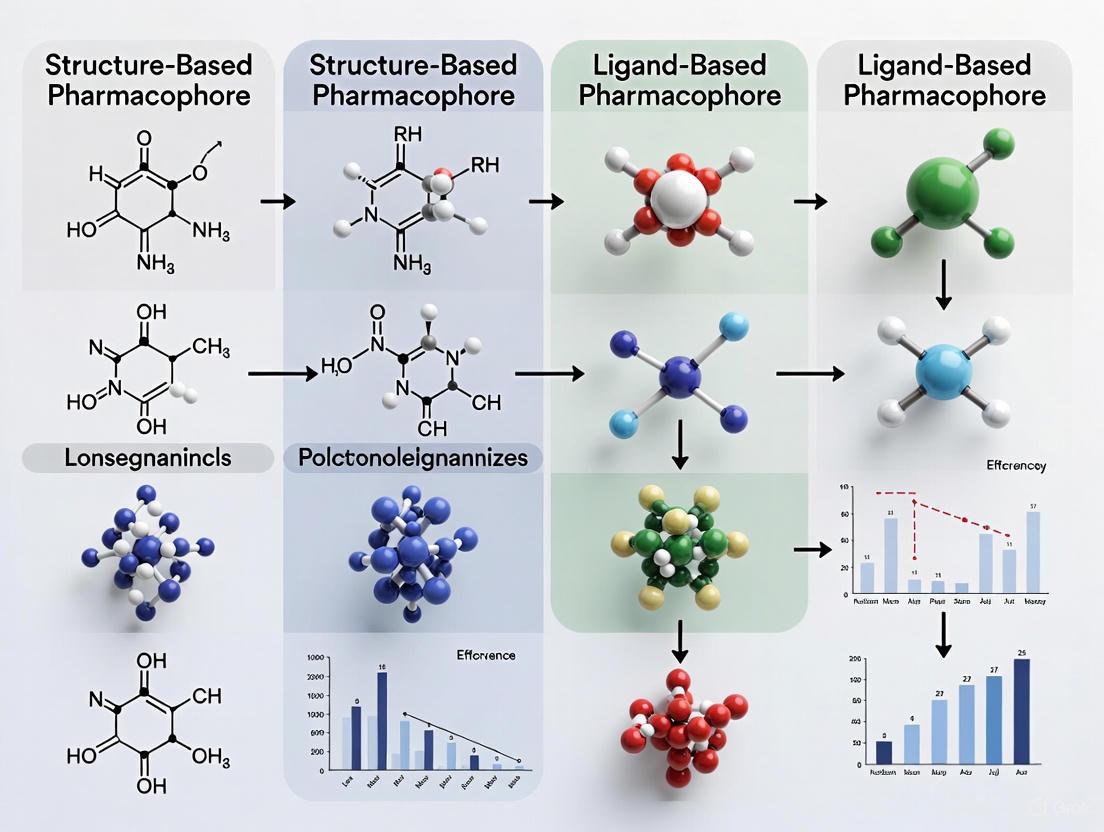

This article provides a comparative analysis of structure-based and ligand-based pharmacophore modeling, two pivotal computational strategies in modern drug discovery.

Structure-Based vs. Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling: A Comprehensive Guide for Effective Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comparative analysis of structure-based and ligand-based pharmacophore modeling, two pivotal computational strategies in modern drug discovery. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles, methodological workflows, and diverse applications of each approach. It delves into their respective limitations and offers practical troubleshooting and optimization strategies. By examining validation frameworks, performance metrics, and emerging trends like AI-integration and hybrid models, this guide serves as a resource for selecting the appropriate pharmacophore technique to accelerate the identification of novel bioactive compounds, supported by case studies and insights from recent literature.

Pharmacophore Foundations: Core Concepts and Strategic Selection Criteria

In the field of computer-aided drug design, the pharmacophore is a foundational concept that provides an abstract representation of molecular interactions. According to the official definition by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC), a pharmacophore is "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or to block) its biological response" [1]. This conceptual framework does not represent a real molecule or specific association of functional groups, but rather captures the essential molecular interaction capacities that a group of compounds must possess to interact effectively with their biological target [1]. The pharmacophore model effectively serves as the largest common denominator shared by a set of active molecules, distilling their interaction capabilities into a set of essential features and their spatial relationships [2].

The historical development of the pharmacophore concept dates back to Paul Ehrlich in the late 19th century, who first suggested that specific groups within a molecule are responsible for its biological activity [1]. The term itself was later established by Lemont Kier in 1967, and the concept has evolved significantly over time to incorporate three-dimensional structural information and advanced computational modeling techniques [3]. Modern pharmacophore modeling has become an indispensable tool in drug discovery, enabling researchers to identify novel bioactive compounds through virtual screening, guide lead optimization, and facilitate scaffold hopping to discover new chemical entities with improved properties [2].

Table 1: Core Pharmacophoric Features and Their Characteristics

| Feature Type | Chemical Groups | Role in Molecular Recognition |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Bond Acceptor | Carbonyl oxygen, ether oxygen, aromatic nitrogen | Accepts hydrogen bonds from donor groups; crucial for specificity |

| Hydrogen Bond Donor | Amino, hydroxyl, thiol groups | Donates hydrogen bonds to acceptor atoms; influences binding affinity |

| Hydrophobic Region | Alkyl chains, aromatic rings | Drives hydrophobic interactions; contributes to binding energy |

| Aromatic Ring | Benzene, pyridine, indole | Participates in π-π stacking, cation-π interactions |

| Positively Ionizable | Protonated amines, quaternary ammonium | Forms electrostatic interactions with negatively charged residues |

| Negatively Ionizable | Carboxylates, phosphates, sulfonates | Interacts with positively charged residues in binding sites |

Essential Chemical Features of Pharmacophores

Steric and Electronic Characteristics

The pharmacophore model represents key interaction points between a ligand and its biological target through a set of essential chemical features. These features include hydrogen bond acceptors (HBA) and hydrogen bond donors (HBD), which are atoms or functional groups capable of forming crucial hydrogen bonding interactions with complementary sites on the target protein [2]. Hydrogen bond donors are typically functional groups capable of donating a hydrogen atom, such as amino, hydroxyl, or thiol groups, while hydrogen bond acceptors are atoms with lone pair electrons that can accept a hydrogen bond, such as carbonyl oxygen, ether oxygen, or aromatic nitrogen atoms [2]. These directional interactions often play a critical role in determining the specificity and affinity of ligand binding.

Hydrophobic regions represent another essential pharmacophoric feature, consisting of non-polar areas of a molecule that tend to avoid interaction with water and prefer to associate with other hydrophobic regions [2]. These regions often comprise alkyl chains or aromatic rings and contribute significantly to the overall lipophilicity of a molecule. Hydrophobic interactions are particularly important for the binding of many drugs to their targets, especially in the case of enzymes and receptors with hydrophobic binding pockets [2]. Additionally, aromatic rings—cyclic, planar, conjugated structures such as benzene, pyridine, or indole—participate in various non-covalent interactions including π-π stacking and cation-π interactions, which can substantially influence binding affinity and selectivity [2].

Charged and Ionizable Groups

Cationic and anionic groups represent another category of important pharmacophoric features. Cationic groups are positively charged functional groups such as protonated amines or quaternary ammonium groups that can form strong electrostatic interactions with negatively charged residues in a target protein [2]. Conversely, anionic groups—including carboxylates, phosphates, or sulfonates—carry negative charges that interact with positively charged residues in binding sites [2]. These charged groups not only contribute to the overall polarity and solubility of a molecule but also frequently play critical roles in specific binding to biological targets through salt bridge formation and other electrostatic interactions.

The appropriate balance and spatial arrangement of these diverse features enable pharmacophore models to capture the essential interaction capabilities of bioactive molecules while allowing for significant chemical diversity among compounds that share the same pharmacophore [4]. This abstraction from specific chemical structures to functional capabilities is precisely what makes pharmacophore modeling such a powerful tool for scaffold hopping and the identification of structurally novel bioactive compounds [5].

3D Spatial Arrangements in Pharmacophore Models

The Role of Molecular Geometry

The three-dimensional spatial arrangement of pharmacophoric features is equally as important as the features themselves in determining biological activity. A pharmacophore model not only specifies which chemical features are essential for activity but also defines their relative positions and geometric relationships in three-dimensional space [1]. This spatial component is crucial because molecular recognition between a ligand and its biological target depends heavily on the complementarity of their interacting surfaces, which requires specific distances, angles, and orientations between interaction points [2]. Even if a compound possesses all the necessary chemical features, improper spatial arrangement will prevent optimal interactions with the target binding site, resulting in reduced activity or complete loss of efficacy.

The concept of molecular conformation is fundamental to understanding 3D pharmacophore models. Ligands can adopt multiple conformations through rotation around single bonds, and the specific conformation that presents the pharmacophoric features in the optimal spatial arrangement for target binding is referred to as the "bioactive conformation" [2]. This conformation may not necessarily correspond to the lowest energy state of the isolated molecule, as binding-induced conformational changes can occur [3]. Therefore, a critical aspect of pharmacophore modeling involves exploring the conformational space of active compounds to identify the common spatial arrangement of features that corresponds to the bioactive conformation [2].

Representing Spatial Relationships

In computational implementations, the spatial relationships between pharmacophoric features are typically represented as constraints on distances, angles, and sometimes torsional angles between features [2]. These constraints are often visualized as a set of spheres or ellipsoids in 3D space, with each sphere representing the allowed spatial region for a particular pharmacophoric feature [4]. The sizes of these spheres reflect the tolerance allowed for variations in the positions of the corresponding features, balancing the need for specificity with the recognition that some flexibility exists in ligand-target interactions.

More sophisticated pharmacophore models may also incorporate exclusion volumes (XVOL) to represent steric restrictions imposed by the binding site architecture [4]. These exclusion volumes define regions in space where the ligand cannot occupy due to clashes with protein atoms, thereby providing additional constraints that improve the selectivity of pharmacophore-based virtual screening [4]. The inclusion of such shape-based constraints helps account for the complementarity between the ligand and the binding site surface, going beyond specific interaction points to capture the overall steric fit required for effective binding.

Methodological Approaches: Structure-Based vs Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

Structure-based pharmacophore modeling relies on the availability of three-dimensional structural information about the target protein, typically obtained through experimental methods such as X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, or cryo-electron microscopy [6]. When a high-resolution structure of the target protein complexed with a ligand is available, this approach analyzes the specific interactions between the ligand and the binding site to identify key pharmacophoric features and their spatial arrangement [4]. The process begins with careful preparation of the protein structure, which may involve adding hydrogen atoms, correcting protonation states, and modeling missing residues or loops [7].

The next critical step involves binding site detection and characterization, which can be accomplished using various computational tools such as GRID or LUDI that analyze the protein surface to identify regions with favorable interaction properties [4]. These programs use different probes representing various functional groups to sample the binding site region and identify locations where specific interactions would be energetically favorable [4]. From this analysis, a map of potential interaction points is generated, and the most critical features for ligand binding are selected to create the pharmacophore hypothesis [4]. The quality of the input protein structure directly influences the reliability of the resulting pharmacophore model, making careful structure preparation and validation essential steps in the process [4].

Table 2: Comparison of Structure-Based vs. Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

| Aspect | Structure-Based Approach | Ligand-Based Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Required Input Data | 3D structure of target protein (from X-ray, NMR, or Cryo-EM) | Set of known active compounds with biological activities |

| Key Methodology | Analysis of protein-ligand interactions in binding site | 3D alignment and comparison of active ligands |

| When to Apply | When high-resolution protein structure is available | When target structure is unknown or uncertain |

| Advantages | Direct incorporation of target structural information; less biased by known ligands | Does not require protein structure; can leverage extensive ligand activity data |

| Limitations | Dependent on quality and relevance of protein structure | Assumes similar binding mode for all active ligands |

| Common Software Tools | LigandScout, MOE, Phase | DISCO, GASP, Catalyst, Phase |

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

Ligand-based pharmacophore modeling is employed when the three-dimensional structure of the target protein is unknown or unavailable. This approach derives the pharmacophore model exclusively from a set of known active compounds, identifying common chemical features and their spatial arrangements that are responsible for the observed biological activity [8]. The fundamental assumption underlying this method is that compounds sharing similar biological activities against the same target likely interact with it through common interaction patterns, even if their overall chemical structures differ significantly [9].

The ligand-based workflow typically begins with the selection of a training set of active compounds with diverse chemical structures but consistent biological activity against the target of interest [9]. These compounds undergo conformational analysis to generate representative sets of their possible three-dimensional structures, as the bioactive conformation may not correspond to the lowest-energy state [2]. The resulting conformers are then aligned using various algorithms that maximize the overlap of their pharmacophoric features, with the goal of identifying common spatial arrangements present across multiple active compounds [3]. From these aligned structures, the common features are extracted and used to generate one or more pharmacophore hypotheses, which are subsequently validated using test sets of known active and inactive compounds [9].

Combined and Hybrid Approaches

Recognizing the complementary strengths and limitations of structure-based and ligand-based methods, researchers have developed combined approaches that integrate information from both sources to create more robust and reliable pharmacophore models [10]. These hybrid strategies can take various forms, including sequential workflows where one method is used to pre-filter compounds before applying the other, parallel approaches where both methods are applied independently and results are combined, or truly integrated methods where pharmacophore generation simultaneously incorporates both protein structural information and ligand activity data [10].

The sequential approach typically begins with ligand-based methods for initial filtering due to their computational efficiency, followed by structure-based methods for more refined analysis of the top hits [10]. This strategy optimizes the trade-off between computational cost and model sophistication while mitigating the individual limitations of each method. For instance, the ligand-based step helps overcome challenges related to protein flexibility in docking, while the subsequent structure-based step reduces the template bias inherent in ligand-based similarity searching [10]. These integrated workflows have demonstrated improved performance in virtual screening campaigns, leading to higher hit rates and greater structural diversity among identified active compounds [10].

Experimental Protocols and Validation Methods

Structure-Based Protocol: FAK1 Kinase Inhibitors

A recent study on identification of novel FAK1 inhibitors provides a representative example of a structure-based pharmacophore modeling protocol [7]. Researchers began by obtaining the co-crystal structure of the FAK1 kinase domain in complex with a known inhibitor P4N (PDB ID: 6YOJ) from the Protein Data Bank. The structure preparation involved modeling missing residues (positions 570-583 and 687-689) using MODELLER software, with selection of the best model based on the lowest zDOPE score [7]. The prepared structure was then uploaded to the Pharmit server to generate pharmacophore models based on the critical interactions observed in the FAK1-P4N complex.

The initial analysis identified eight potential pharmacophoric features, from which six distinct pharmacophore models containing five or six features each were constructed [7]. These models were rigorously validated using a dataset of 114 known active FAK1 inhibitors and 571 decoy compounds (inactive molecules) obtained from the DUD-E database [7]. Statistical metrics including sensitivity, specificity, enrichment factor (EF), and goodness of hit (GH) were calculated to evaluate each model's performance in distinguishing active from inactive compounds [7]. The best-performing model was subsequently used for virtual screening of the ZINC database, followed by molecular docking, ADMET property prediction, and molecular dynamics simulations to identify and validate promising FAK1 inhibitor candidates [7].

Ligand-Based Protocol: Topoisomerase I Inhibitors

A comprehensive ligand-based pharmacophore modeling study for Topoisomerase I (Top1) inhibitors demonstrates the typical workflow for this approach [9]. Researchers compiled a dataset of 62 camptothecin derivatives with experimentally determined IC50 values against A549 cancer cell lines, ensuring all biological activity data were obtained from homogeneous assays under consistent conditions [9]. The compounds were divided into a training set of 29 molecules representing diverse structural classes and activity ranges (IC50 from 0.003 μM to 11.4 μM), and a test set of 33 compounds for model validation [9].

The pharmacophore model was developed using the HypoGen algorithm in Discovery Studio, which incorporates quantitative activity data to generate predictive models [9]. The process involved conformational analysis of the training set compounds, generation of common feature hypotheses, and quantitative model optimization based on the experimental IC50 values [9]. The resulting top model (Hypo1) demonstrated a strong correlation between estimated and experimental activities, with correlation coefficients of 0.918 for the training set and 0.875 for the test set [9]. This validated model was subsequently used as a 3D query for virtual screening of over one million drug-like compounds from the ZINC database, followed by successive filtering steps based on Lipinski's Rule of Five, SMART functional group filtration, and activity criteria to identify novel Top1 inhibitor candidates [9].

Diagram 1: Ligand-based pharmacophore modeling workflow

Quantitative Comparison of Method Effectiveness

Performance Metrics in Virtual Screening

The effectiveness of pharmacophore modeling approaches is typically evaluated using standardized performance metrics in virtual screening applications. Key statistical measures include sensitivity (the ability to correctly identify active compounds), specificity (the ability to reject inactive compounds), enrichment factor (EF) (the increase in hit rate compared to random selection), and goodness of hit (GH) (a composite measure balancing recall and precision) [7]. These metrics provide quantitative assessments of a pharmacophore model's ability to distinguish between active and inactive compounds, which is crucial for its practical utility in drug discovery campaigns.

For structure-based models, validation often involves screening databases containing known active compounds and decoy molecules, with calculation of these statistical parameters to select the optimal model [7]. In the FAK1 inhibitor study, the best pharmacophore model achieved a sensitivity of 85.1%, specificity of 92.3%, enrichment factor of 8.7, and goodness of hit score of 0.81, demonstrating strong performance in identifying true active compounds while minimizing false positives [7]. Ligand-based models are typically validated using test sets of compounds with known activities, with correlation coefficients between predicted and experimental activities serving as key indicators of model quality [9].

Case Study Comparisons

Direct comparison of structure-based and ligand-based approaches in practical applications reveals their respective strengths and limitations. In the Topoisomerase I inhibitor study, the ligand-based pharmacophore model (Hypo1) successfully identified three novel inhibitor candidates (ZINC68997780, ZINC15018994, and ZINC38550809) through virtual screening of over one million compounds [9]. These hits exhibited stable binding in molecular dynamics simulations and favorable toxicity profiles, demonstrating the power of ligand-based approaches when comprehensive activity data is available for diverse chemotypes [9].

Conversely, the structure-based approach for FAK1 inhibitors leveraged detailed structural information from a high-resolution crystal complex to identify four promising candidates (ZINC23845603, ZINC44851809, ZINC266691666, and ZINC20267780) with strong binding affinities and interaction patterns similar to the reference ligand P4N [7]. Molecular dynamics simulations confirmed the stability of these complexes, with ZINC23845603 emerging as a particularly promising candidate for further development [7]. This structure-based approach proved especially valuable for identifying compounds that maintain key interactions with the target protein while exploring novel chemical space beyond known active scaffolds.

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Recent Pharmacophore Applications

| Study Target | Approach | Database Screened | Hit Rate | Most Promising Candidate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FAK1 Kinase Inhibitors [7] | Structure-Based | ZINC database | Not specified | ZINC23845603 (strong binding in MD simulations) |

| Topoisomerase I Inhibitors [9] | Ligand-Based | 1,087,724 compounds from ZINC | 3 final hits from 6 candidates | ZINC68997780 (validated by MD and toxicity assessment) |

| PLK1 Inhibitors [5] | Pharmacophore-Informed Generative Model | de novo generation | 3 of 4 synthesized compounds showed submicromolar activity | IIP0943 (5.1 nM potency, novel scaffold) |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Successful implementation of pharmacophore modeling requires access to specialized software tools, compound databases, and computational resources. The field offers both commercial and open-source options catering to different aspects of pharmacophore model generation, validation, and application. Understanding the capabilities and limitations of these tools is essential for researchers designing pharmacophore-based drug discovery campaigns.

Table 4: Essential Software Tools for Pharmacophore Modeling

| Software/Resource | Type | Key Features | Approach Supported |

|---|---|---|---|

| LigandScout [8] [3] | Commercial (some features available in open-source) | Structure-based pharmacophore modeling, virtual screening | Structure-Based, Ligand-Based |

| MOE (Molecular Operating Environment) [1] [8] | Commercial | Comprehensive drug discovery suite with pharmacophore modeling | Structure-Based, Ligand-Based |

| Catalyst/HypoGen [9] [3] | Commercial | Quantitative pharmacophore modeling with activity prediction | Primarily Ligand-Based |

| Phase [1] [3] | Commercial | Flexible pharmacophore modeling, alignment, and screening | Structure-Based, Ligand-Based |

| Pharmit [8] [7] | Web-based Server | Structure-based pharmacophore modeling and virtual screening | Structure-Based |

| ZINC Database [9] [7] | Compound Library | Over 1 million drug-like molecules for virtual screening | Screening Resource |

| DUD-E Database [7] | Benchmarking Set | Curated active and decoy molecules for method validation | Validation Resource |

Commercial software packages such as LigandScout, MOE, and Discovery Studio (which includes the Catalyst/HypoGen algorithms) provide comprehensive environments for both structure-based and ligand-based pharmacophore modeling [8] [9]. These tools typically offer user-friendly interfaces, integrated workflows for model generation and validation, and efficient algorithms for virtual screening of compound databases [3]. For researchers with limited budgets, open-source alternatives and web servers such as Pharmer, Align-it, and Pharmit provide capable alternatives for specific tasks like pharmacophore-based screening and molecular alignment [8].

Essential resources for pharmacophore modeling also include compound databases such as ZINC, which contains over one million commercially available drug-like molecules suitable for virtual screening [9] [7]. For method validation, benchmark sets like the Directory of Useful Decoys - Enhanced (DUD-E) provide carefully curated collections of known active compounds and matched decoy molecules, enabling rigorous assessment of pharmacophore model performance [7]. The Protein Data Bank (PDB) remains an indispensable resource for structure-based approaches, offering thousands of high-resolution protein structures, many complexed with bioactive ligands that can serve as templates for pharmacophore model generation [4] [7].

Diagram 2: Structure-based pharmacophore modeling workflow

Emerging Trends and Future Perspectives

The field of pharmacophore modeling continues to evolve, with several emerging trends shaping its future development and application. One significant advancement is the integration of pharmacophore concepts with deep generative models for de novo molecular design [5]. Approaches like TransPharmer combine ligand-based interpretable pharmacophore fingerprints with generative pre-training transformer frameworks to create novel molecular structures that satisfy specific pharmacophoric constraints while exploring underrepresented regions of chemical space [5]. This integration has demonstrated impressive results in case studies, with generated PLK1 inhibitors showing submicromolar activities and novel scaffolds distinct from known reference compounds [5].

Another important trend is the increasing sophistication of hybrid methods that combine ligand-based and structure-based approaches in more integrated workflows rather than sequential applications [10]. These approaches aim to simultaneously leverage the complementary strengths of both methodologies, resulting in more robust models with enhanced predictive capabilities [10]. The development of standardized frameworks for combining multiple virtual screening methods, including consensus scoring schemes and machine learning-based integration, represents an active area of research that addresses the limitations of individual approaches [10].

Advances in handling molecular flexibility and accounting for binding site plasticity also represent important frontiers in pharmacophore modeling [2]. Traditional pharmacophore models often treat the protein binding site as rigid, which can limit their accuracy for targets that undergo significant conformational changes upon ligand binding [10]. New approaches that incorporate ensemble representations of both ligand and protein conformations, often derived from molecular dynamics simulations, show promise for creating more realistic models that better capture the dynamic nature of molecular recognition [10]. As these methodologies mature and integrate with artificial intelligence approaches, pharmacophore modeling is poised to remain a cornerstone of computer-aided drug discovery, enabling increasingly efficient exploration of chemical space and acceleration of therapeutic development.

Structure-based pharmacophore modeling is a computational drug design strategy that derives essential interaction features directly from the three-dimensional structure of a target protein. This method is fundamentally dependent on high-quality structural information about the biological target, typically obtained through experimental techniques like X-ray crystallography, cryo-electron microscopy (Cryo-EM), or Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy [6]. The core principle involves analyzing a protein's binding pocket—whether in its apo form (unbound) or in complex with a ligand—to identify key chemical features and their spatial arrangements that a molecule must possess to achieve effective binding and elicit a biological response [11] [7]. These features often include hydrogen bond donors and acceptors, hydrophobic regions, positively or negatively charged groups, and aromatic rings [11].

Unlike ligand-based approaches that rely on known active compounds, structure-based pharmacophore modeling serves as a powerful target-centric paradigm. It is particularly invaluable in scenarios where few or no active ligands are known, enabling de novo drug discovery by leveraging the underlying structural biology of the target [7] [12]. The effectiveness of this approach is intrinsically linked to the quality and completeness of the protein structure, as inaccuracies in side-chain positioning, missing loops, or unresolved conformational dynamics can significantly compromise the generated model [13] [6].

Core Principles and Workflow

The construction of a structure-based pharmacophore model follows a logical sequence, transforming 3D structural data into an abstract query for virtual screening. The process can be distilled into four key stages, as illustrated below.

Structure Preparation and Binding Site Identification

The initial and most critical step involves curating a high-quality protein structure. The structure, often from the Protein Data Bank (PDB), must be preprocessed to add missing hydrogen atoms, assign correct protonation states at biological pH, and rectify any structural anomalies such as missing residues or loops [7]. Tools like Chimera and MODELLER are frequently used for this purpose [7]. Subsequently, the binding site of interest must be precisely defined. This can be the known active site (e.g., the ATP-binding pocket in kinases) or a putative allosteric site. The location is often identified based on the coordinates of a co-crystallized ligand or through computational binding site detection algorithms [11].

Pharmacophore Feature Extraction and Model Generation

Within the defined binding site, critical interaction points between the protein and a potential ligand are identified and translated into pharmacophore features [7]. Software such as Pharmit automates this process by analyzing the protein-ligand complex to pinpoint features like hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic patches, and ionic interactions [11] [7]. The results is a three-dimensional set of chemical feature types and their precise spatial coordinates, which together form the pharmacophore query [11]. This model encapsulates the essential interactions a molecule must fulfill to bind effectively, serving as a template for screening.

Critical Dependence on Target Protein Structures

The fidelity of a structure-based pharmacophore model is inextricably linked to the quality and characteristics of the input protein structure. Several key factors determine the success of this dependency.

Source and Quality of the Protein Structure

The method of structure determination significantly impacts model reliability. Experimentally solved structures (X-ray, Cryo-EM, NMR) are considered the gold standard. However, the resolution of crystal structures is a crucial metric; high-resolution structures (e.g., < 2.0 Å) provide precise atomic coordinates, leading to more accurate feature placement, whereas low-resolution structures can misrepresent key interactions, especially concerning side-chain orientations [7] [6].

When experimental structures are unavailable, researchers may turn to computationally predicted models. The emergence of deep learning-based tools like AlphaFold has significantly expanded the repository of accessible protein structures [13]. However, a major limitation of standard AlphaFold models is their prediction of a single, static conformation, which often fails to capture the conformational flexibility and changes associated with ligand binding [13]. This can lead to false negatives or inaccurate pose predictions in docking and pharmacophore generation. While newer co-folding methods like AlphaFold3 show promise in generating ligand-bound structures, their performance can falter when predicting structures dissimilar to their training set or allosteric binding sites, and they generally require careful post-modeling refinement for reliable application [13].

Accounting for Protein Flexibility and Solvation

Proteins are dynamic entities, and a single static structure may not represent all relevant biological states. A model derived from a single conformation might be too rigid, potentially missing valid ligands that bind through alternative poses or to different protein conformations [12]. Advanced methods now address this limitation. Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations can be used to sample multiple protein conformations, and pharmacophore features can be extracted from these dynamic trajectories to create more robust, "ensemble" pharmacophore models [12]. Furthermore, water-based pharmacophore modeling is an emerging strategy that uses MD simulations of explicit water molecules within apo (empty) binding sites to identify consensus hydration sites. These sites represent interaction "hotspots" that can be translated into pharmacophore features, offering a ligand-independent method to account for the role of water in molecular recognition [12].

Comparative Analysis: Structure-Based vs. Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

Pharmacophore modeling strategies are broadly categorized into structure-based and ligand-based approaches, each with distinct prerequisites, strengths, and limitations. The table below provides a direct comparison.

| Aspect | Structure-Based Pharmacophore | Ligand-Based Pharmacophore |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Data Source | 3D structure of the target protein [6] | Set of known active ligands [13] [6] |

| Key Prerequisite | High-quality protein structure (experimental or high-confidence predicted) [6] | A sufficient number of structurally diverse active compounds [13] |

| Core Principle | Identifies essential interaction features from the binding pocket [7] | Extracts common chemical features shared by known actives [13] [6] |

| Advantages | • Applicable without known ligands (de novo design) [7]• Provides atomic-level insight into binding interactions [13]• Can identify novel scaffolds and allosteric sites | • Fast and computationally inexpensive [13]• No need for a protein structure [6]• Excellent for scaffold hopping and pattern recognition [13] |

| Limitations & Challenges | • Highly dependent on structure quality and completeness [13] [6]• Can struggle with protein flexibility [12]• More computationally expensive for setup | • Limited by the diversity and bias of known actives• Cannot explain the structural basis of activity [6]• Ineffective for targets with no known ligands |

The two approaches are highly complementary. A common strategy in modern drug discovery is sequential integration, where rapid ligand-based screening filters a large chemical library, followed by structure-based refinement of the most promising hits [13]. This conserves computational resources while improving the precision of hit identification. Alternatively, parallel screening with both methods, followed by consensus scoring, can increase the likelihood of recovering true active compounds and mitigate the inherent limitations of each approach [13].

Experimental Protocols and Validation

To ensure a pharmacophore model is effective and reliable, it must be rigorously validated before use in virtual screening. The following workflow, based on a study identifying novel FAK1 inhibitors, outlines a standard protocol for creation and validation [7].

Detailed Methodology: A FAK1 Inhibitor Case Study

A recent study to identify novel Focal Adhesion Kinase 1 (FAK1) inhibitors provides a robust template for structure-based pharmacophore modeling [7].

- Structure Preparation: The crystal structure of the FAK1 kinase domain in complex with a known inhibitor (P4N, PDB ID: 6YOJ) was obtained. Missing residues (positions 570–583 and 687–689) were modeled using MODELLER, and the structure with the lowest zDOPE score was selected for subsequent analysis [7].

- Pharmacophore Modeling: The prepared FAK1-P4N complex was uploaded to the web-based tool Pharmit. The software automatically identified eight critical pharmacophoric features involved in the protein-ligand interaction. From these, six distinct pharmacophore models, each containing five or six features, were constructed for evaluation [7].

- Model Validation: The generated models were statistically validated using a set of 114 known active FAK1 inhibitors and 571 inactive decoys from the DUD-E database. Each model was used to screen these libraries, and performance was assessed using metrics including Sensitivity, Specificity, Enrichment Factor (EF), and Goodness of Hit (GH) score. The model with the highest validation performance was selected for prospective virtual screening [7].

- Virtual Screening and Hit Identification: The validated pharmacophore model was used as a 3D query to screen the ZINC database, a vast commercial library of purchasable compounds. Molecules matching the pharmacophore constraints were subsequently subjected to molecular docking. Seventeen compounds with acceptable predicted pharmacokinetic properties and low toxicity were selected for more precise docking simulations, leading to the identification of four promising candidates [7].

- Advanced Validation: The stability of the FAK1 complexes with these four candidates was evaluated using Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations in GROMACS, with binding free energies calculated via the MM/PBSA method. One compound, ZINC23845603, demonstrated strong binding and interaction features similar to the known ligand P4N, marking it as a prime candidate for further experimental testing [7].

Performance Benchmarking of Modern Approaches

Recent AI-driven methods demonstrate the evolving power of structure-based approaches. The table below summarizes quantitative performance data from recent studies on generative models that integrate pharmacophore constraints.

| Model / Framework | Core Approach | Reported Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|

| PGMG [14] | Pharmacophore-guided deep learning (GNN + Transformer) | Generated molecules showed strong docking affinities with high validity, uniqueness, and novelty [14]. |

| CMD-GEN [15] | Coarse-grained pharmacophore sampling + hierarchical generation | Outperformed other methods (ORGAN, VAE, SMILES LSTM) in benchmark tests, effectively controlling drug-likeness [15]. |

| PharmacoForge [11] | Diffusion model for 3D pharmacophore generation | Surpassed other automated methods on the LIT-PCBA benchmark. Resulting ligands had lower strain energies than de novo generated ligands [11]. |

| PharmaDiff Framework [16] | Pharmacophore-guided RL balancing similarity & novelty | Generated molecules achieved high pharmacophoric fidelity (Cosine Sim: 0.94) and 100% novelty while maintaining favorable QED (0.33) and SA scores (4.64) [16]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful implementation of structure-based pharmacophore modeling relies on a suite of specialized software tools and databases.

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Database | Primary repository for experimentally determined 3D structures of proteins and nucleic acids [7]. |

| Pharmit [11] [7] | Software | Web-based tool for interactive, structure-based pharmacophore modeling and high-performance virtual screening. |

| MODELLER [7] | Software | Used for homology modeling of missing protein loops or regions in an experimental structure. |

| DUD-E Database [7] | Database | Provides sets of known active molecules and property-matched decoys for rigorous validation of virtual screening methods. |

| ZINC Database [7] | Database | A freely available commercial database of over 230 million purchasable compounds in ready-to-dock 3D formats. |

| GROMACS [7] | Software | A molecular dynamics package primarily used for simulating the physical movements of atoms and molecules under Newton's laws of motion. |

| PyRod [12] | Software | A tool that can generate pharmacophore models from MD simulation trajectories, capturing dynamic interaction features. |

Structure-based pharmacophore modeling stands as a powerful, target-driven methodology in rational drug design. Its fundamental dependency on high-quality target protein structures is both its greatest strength and most significant constraint. While challenges related to protein flexibility and the quality of predicted structures remain, advancements in MD simulations, the integration of water dynamics, and sophisticated AI-driven generative models are steadily addressing these limitations. The synergy between structure-based and ligand-based approaches, alongside the continuous improvement of structural databases and computational tools, promises to further solidify pharmacophore modeling's role in accelerating the efficient discovery of novel therapeutic agents.

Pharmacophore modeling is a foundational technique in computer-aided drug discovery that abstracts the essential steric and electronic features responsible for a molecule's biological activity. According to the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) definition, a pharmacophore represents "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supra-molecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or to block) its biological response" [4]. In the specific domain of ligand-based pharmacophore modeling, this approach relies exclusively on information derived from known active compounds, making it particularly valuable when the three-dimensional structure of the target protein is unavailable or difficult to obtain [4] [8]. This methodology operates on the fundamental principle that compounds sharing common biological activity against a specific target will possess complementary chemical functionalities arranged in a conserved three-dimensional orientation [4] [17].

Unlike structure-based methods that require protein structural data from techniques such as X-ray crystallography or NMR spectroscopy, ligand-based approaches utilize the collective chemical information embedded within a set of active ligands to deduce the critical features necessary for target interaction [8] [6]. This strategy effectively reverse-engineers the binding site requirements through comparative analysis of molecules that successfully interact with the target, positioning it as an indispensable tool in the drug discovery arsenal, especially for targets with elusive structural information such as membrane proteins or large complexes [6].

Fundamental Principles of Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

Core Components and Feature Definitions

Ligand-based pharmacophore models capture the essential chemical features shared by active molecules that enable target binding and biological activity. The most significant pharmacophoric feature types include [4] [8]:

- Hydrogen bond acceptors (HBAs): Atoms that can accept hydrogen bonds, typically oxygen or nitrogen with lone electron pairs.

- Hydrogen bond donors (HBDs): Groups containing a hydrogen atom bonded to an electronegative atom (O-H, N-H).

- Hydrophobic areas (H): Non-polar regions of the molecule that favor lipid environments.

- Positively and negatively ionizable groups (PI/NI): Functional groups that can carry positive or negative charges under physiological conditions.

- Aromatic groups (AR): Planar ring systems with delocalized π-electrons.

- Metal coordinating areas: Atoms with lone electron pairs capable of coordinating with metal ions.

These features are represented in three-dimensional space as geometric entities—spheres, planes, and vectors—that define the spatial requirements for molecular recognition [4]. The model effectively creates a three-dimensional fingerprint of the interaction capacity that a ligand must possess to elicit a biological response from a specific target.

Theoretical Foundation and Assumptions

The theoretical foundation of ligand-based pharmacophore modeling rests on several key assumptions [4] [8]:

- Commonality Principle: Structurally diverse compounds exhibiting similar biological activity against the same target must share common pharmacophoric features responsible for that activity.

- Spatial Conservation: The three-dimensional arrangement of these features is conserved across active compounds, reflecting complementary positioning to the target's binding site.

- Feature Dominance: The specific atoms and molecular scaffolds may differ, but the ensemble of chemical functionalities and their spatial relationships determines activity.

This approach is particularly powerful because it focuses on chemical functionalities rather than specific atoms or scaffolds, enabling identification of structurally divergent compounds with similar biological effects—a process known as "scaffold hopping" [4]. The methodology is inherently target-agnostic, deriving all information from ligand properties without requiring direct knowledge of the biological counterpart [17].

Methodological Workflow: From Active Ligands to Validated Models

The development of a robust ligand-based pharmacophore model follows a systematic workflow that transforms a collection of active compounds into a validated screening tool. The process, summarized in Figure 1, involves multiple stages of computational analysis and validation.

Key Experimental Steps and Protocols

Figure 1: Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling Workflow

Selection of Active Compounds: The process begins with curating a set of known active compounds (training dataset) with validated biological activity against the target of interest. These molecules should represent diverse chemical scaffolds to ensure the derived model captures essential rather than incidental features [8].

Conformational Analysis and 3D Alignment: Each active compound undergoes extensive conformational sampling to generate representative three-dimensional structures. The resulting conformers are then aligned to identify the optimal spatial overlap, typically focusing on maximizing the commonality of pharmacophoric features while allowing for scaffold diversity [8]. This step is computationally intensive and requires sophisticated algorithms to efficiently explore conformational space.

Pharmacophore Feature Identification and Hypothesis Generation: The aligned molecules are analyzed to detect conserved chemical features across the set. Software algorithms identify features that are common to all or most active compounds and generate multiple pharmacophore hypotheses representing different possible arrangements of these features [4] [8].

Model Validation Using Active and Decoy Compounds: The generated pharmacophore models must be rigorously validated before application in virtual screening. This critical step involves testing each model's ability to correctly identify known active compounds (true positives) while rejecting inactive molecules (decoys or true negatives) from a test dataset [8] [7]. Statistical metrics including sensitivity, specificity, enrichment factor, and goodness of hit (GH) scores are calculated to quantify model performance [7].

Validation Metrics and Statistical Assessment

Comprehensive validation is essential for establishing the predictive power of a pharmacophore model. The following statistical measures, derived from the confusion matrix of classification results, provide quantitative assessment of model quality [7]:

- Sensitivity (True Positive Rate): (Ha / A) × 100, where Ha is the number of active compounds correctly identified by the model, and A is the total number of active compounds in the test set.

- Specificity (True Negative Rate): (Hd / D) × 100, where Hd is the number of decoys correctly rejected, and D is the total number of decoys.

- Enrichment Factor (EF): Measures how much more likely the model is to select active compounds compared to random selection.

- Goodness of Hit (GH) Score: A composite metric that balances the model's ability to retrieve active compounds while minimizing the selection of decoys, with values closer to 1 indicating better performance.

This validation protocol ensures that only statistically robust models proceed to virtual screening applications, significantly improving the likelihood of identifying truly active compounds [7].

Comparative Analysis: Ligand-Based vs. Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

Methodological Differences and Data Requirements

Ligand-based and structure-based pharmacophore modeling represent two complementary approaches with distinct methodological foundations and data requirements, as systematically compared in Table 1.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Ligand-Based vs. Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

| Parameter | Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling | Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Data Source | Known active compounds (ligands) [4] [8] | 3D structure of target protein (with or without ligand) [4] [6] |

| Protein Structure Requirement | Not required [8] [6] | Essential (from X-ray, NMR, Cryo-EM, or homology modeling) [4] [6] |

| Key Methodology | 3D alignment of active compounds and common feature identification [8] | Analysis of binding site interactions and complementary features [4] |

| Exclusion Volumes | Not inherently included (may be added manually if binding site is known) [4] | Directly derived from binding site topography [4] |

| Handling of Protein Flexibility | Implicitly captured through diverse ligand conformations [4] | Requires additional techniques (e.g., MD simulations, multiple structures) [18] |

| Applicability Domain | Targets with known active ligands but unknown structure [17] [6] | Targets with experimentally determined or modeled structures [4] |

| Key Advantages | No need for protein structure; scaffold hopping capability [4] [17] | Direct mapping to binding site; inclusion of shape constraints [4] |

| Primary Limitations | Dependent on quality and diversity of known actives [4] [8] | Requires high-quality protein structure; sensitive to conformational changes [4] [6] |

Performance Considerations and Application Scope

The choice between ligand-based and structure-based approaches depends heavily on available data, target characteristics, and project objectives. Ligand-based methods demonstrate particular strength when [4] [6]:

- The target structure is unknown, difficult to resolve, or exhibits high flexibility.

- A diverse set of active compounds with measured activities is available.

- The project aims to identify novel chemotypes through scaffold hopping.

- Rapid screening of large compound libraries is prioritized.

Recent advances have enabled the integration of both approaches through hybrid methods. For example, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations can enhance structure-based models by incorporating protein flexibility, while hierarchical graph representations of pharmacophore models (HGPM) enable intuitive visualization and selection of pharmacophore feature sets derived from dynamic simulations [18]. Such integrative strategies leverage the complementary strengths of both paradigms, potentially overcoming their individual limitations.

Experimental Validation: Case Studies and Performance Metrics

Virtual Screening Performance and Enrichment Assessment

The ultimate validation of any pharmacophore modeling approach lies in its performance in real-world virtual screening scenarios. Table 2 summarizes quantitative performance data from published studies implementing ligand-based pharmacophore screening campaigns.

Table 2: Virtual Screening Performance of Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Models

| Study Target/Application | Model Performance Metrics | Key Outcomes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mosquito Repellent Discovery (Odorant-binding protein) | Combined ligand-based and structure-based screening of 1,633 essential oil compounds | Identified 7 natural volatiles with predicted repellent activity (e.g., thymyl isovalerate) [8] | Santana et al. [8] |

| FAK1 Kinase Inhibitor Identification | Pharmacophore model validation with 114 actives and 571 decoys; enrichment-based selection | Highest performing model used for ZINC database screening; 4 promising candidates identified [7] | Scientific Reports (2025) [7] |

| Estrogen Receptor Modulators (AI-generated compounds) | Pharmacophore similarity (Cosine: 0.83-0.94) vs. structural diversity (Tanimoto: 0.34-0.36) | Generated novel compounds with high pharmacophoric fidelity and improved drug-likeness (QED: 0.33-0.59) [16] | Podplutova et al. [16] |

| General Model Validation Framework | Sensitivity, Specificity, Yield of Actives (Recall), Enrichment Factor, Goodness of Hit (GH) | Statistical validation protocol for reliable virtual screening [7] | Bio-protocol [8] |

Impact of Model Selectivity on Screening Outcomes

A critical consideration in ligand-based pharmacophore screening is the balance between model selectivity and structural diversity. Excessively strict models, while ensuring high activity in identified hits, may eliminate valuable chemotypes and reduce structural novelty [8]. Conversely, overly permissive models retrieve larger hit sets but introduce more false positives, increasing the experimental validation burden [8]. This selectivity-diversity tradeoff must be carefully managed based on project goals—whether prioritizing highly active compounds within known chemotypes or seeking novel scaffolds with potentially unique properties.

Recent approaches incorporating machine learning and AI have demonstrated promising capabilities in navigating this tradeoff. For instance, reinforcement learning frameworks can simultaneously optimize pharmacophore similarity to reference active compounds while maximizing structural novelty in generated molecules, effectively expanding the accessible chemical space while maintaining biological relevance [16].

Research Toolkit: Essential Software and Databases

Computational Tools for Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

| Resource Name | Type | Key Functionality | Access Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| LigandScout | Software | Ligand- and structure-based pharmacophore modeling; virtual screening [8] [18] | Commercial |

| Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) | Software | Comprehensive drug discovery suite with pharmacophore modeling capabilities [8] | Commercial |

| BIOVIA Discovery Studio | Software | CATALYST pharmacophore modeling; database screening with PharmaDB [19] | Commercial |

| Pharmer | Software | Open-source ligand-based pharmacophore screening [8] | Open Source |

| Align-it | Software | Align molecules based on pharmacophore features (formerly Pharao) [8] | Open Source |

| Phase (Schrödinger) | Software | Pharmacophore modeling and screening with prepared commercial libraries [20] | Commercial |

| ZINC Database | Compound Database | Publicly accessible database of commercially available compounds for virtual screening [7] | Free Access |

| ChEMBL Database | Bioactivity Database | Manually curated database of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties [18] | Free Access |

| DUD-E Database | Benchmarking Set | Directory of useful decoys for virtual screening method evaluation [7] | Free Access |

Implementation Considerations and Best Practices

Successful implementation of ligand-based pharmacophore modeling requires careful attention to several practical aspects:

Compound Selection and Curation: The training set should include structurally diverse compounds with confirmed activity and preferably similar potency ranges. Including inactive compounds during validation helps improve model selectivity [8] [7].

Conformational Sampling: Comprehensive exploration of conformational space is essential, as the bioactive conformation may not correspond to the global energy minimum. Efficient algorithms balance computational expense with adequate coverage of accessible conformations [20].

Feature Selection and Weighting: Not all common features are equally important for binding. Some implementations incorporate feature weighting based on energetic contributions or conservation across active compounds [4].

Validation Rigor: Proper validation using separate test sets with known actives and decoys is crucial before proceeding to large-scale screening. Statistical measures should guide model selection rather than visual inspection alone [7].

Ligand-based pharmacophore modeling remains an indispensable approach in the computer-aided drug design toolkit, particularly for targets lacking structural characterization. Its exclusive reliance on known active compounds positions it as a powerful method for leveraging historical structure-activity relationship data to guide future compound design and screening. The methodology excels at identifying diverse chemotypes that share essential interaction capabilities—a capability increasingly valued in contemporary drug discovery for overcoming intellectual property constraints and optimizing drug-like properties.

When strategically integrated with structure-based approaches, machine learning technologies, and experimental validation, ligand-based pharmacophore modeling continues to deliver significant value across various applications including virtual screening, lead optimization, and drug repurposing. As compound databases expand and computational power increases, this methodology will likely evolve toward more dynamic representations and integrated workflows, further solidifying its role in efficient drug discovery pipelines.

Pharmacophore modeling is an indispensable tool in modern computer-aided drug discovery, providing an abstract representation of the steric and electronic features necessary for a molecule to interact with a biological target and trigger its biological response [4]. The concept, rooted in Emil Fisher's 19th-century "Lock & Key" principle, has evolved into two primary computational approaches: structure-based and ligand-based pharmacophore modeling [4] [8]. These methodologies differ fundamentally in their foundational principles, data prerequisites, and application domains, making the understanding of their comparative strengths and limitations crucial for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. This guide provides a direct, objective comparison of these approaches, framed within a broader thesis on evaluating their effectiveness, and is supported by current experimental data, detailed methodologies, and essential research tools.

Foundational Principles and Data Requirements

The core distinction between structure-based and ligand-based pharmacophore approaches lies in their source information and underlying principles.

Structure-based pharmacophore modeling relies on the three-dimensional structure of a macromolecular target, obtained from techniques like X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, or Cryo-EM [4] [6]. The process involves preparing the protein structure, identifying the ligand-binding site, and generating pharmacophore features directly from the interactions observed in the binding pocket [4]. This approach defines the molecular functional features required for binding by analyzing the complementarity between the ligand and the receptor's active site [4] [6]. When the structure of a protein-ligand complex is available, the model can be built with high accuracy by incorporating the ligand's bioactive conformation and spatial restrictions from the binding site shape through exclusion volumes [4].

Ligand-based pharmacophore modeling is applied when the three-dimensional structure of the target protein is unknown or difficult to obtain. This method uses the physicochemical properties and three-dimensional alignment of a set of known active ligands to deduce the common chemical functionalities and their spatial arrangement necessary for biological activity [4] [8]. The fundamental principle is that compounds sharing common chemical features and a similar spatial arrangement are likely to exhibit similar biological effects on the same target [4]. Techniques such as Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) are often used in conjunction to model the relationship between chemical structure and biological activity [6].

Table 1: Foundational Principles and Data Requirements

| Aspect | Structure-Based Pharmacophore | Ligand-Based Pharmacophore |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Molecular recognition and complementarity based on the 3D target structure [4] [6]. | Common chemical features and spatial arrangement derived from known active ligands [4] [8]. |

| Essential Data | High-resolution 3D structure of the target (e.g., from PDB) or a reliable homology model [4] [6]. | A set of known active compounds with diverse structures for training [4] [8]. |

| Target Structure Requirement | Mandatory [6]. | Not required [6]. |

| Key Advantage | Direct insight into target-ligand interactions; can design novel scaffolds [4] [6]. | Applicable when target structure is unknown; leverages existing ligand data [6]. |

| Primary Limitation | Dependent on the availability and quality of the target structure [4] [6]. | Limited by the diversity and quality of known active ligands [8]. |

Performance and Experimental Data

Experimental data and benchmark studies demonstrate the performance and effectiveness of both approaches in various drug discovery tasks, such as virtual screening and molecule generation.

Structure-Based Methods: Advanced structure-based frameworks like CMD-GEN demonstrate powerful performance in generating molecules tailored to specific protein pockets. As shown in Table 2, CMD-GEN's molecular generation module (GCPG) achieves high validity (95.8%), novelty (91.4%), and uniqueness (99.3%) [21]. This method bridges ligand-protein complexes with drug-like molecules by utilizing coarse-grained pharmacophore points sampled from a diffusion model, enriching the training data and enabling controlled generation of specific, active molecules [21]. In another study, the DiffPhore framework, which performs 3D ligand-pharmacophore mapping, surpassed traditional pharmacophore tools and several advanced docking methods in predicting binding conformations, demonstrating superior virtual screening power for lead discovery and target fishing [22].

Ligand-Based Methods: The PGMG (Pharmacophore-Guided deep learning approach for bioactive Molecule Generation) model showcases the strength of ligand-based strategies. As illustrated in Table 2, PGMG performs best in novelty (93.5%) and the ratio of available molecules (87.3%), while maintaining a high validity of 94.6% [14]. PGMG uses pharmacophore hypotheses as a bridge to connect different types of activity data and can generate molecules without requiring target structure information, making it particularly useful for novel targets with insufficient activity data [14]. Topological Pharmacophore (TP) representations, such as Sparse Pharmacophore Graphs (SPhGs), are also effective in ligand-based screening. They use topological distances on a chemical graph and have been shown to identify structurally different active compounds, facilitating scaffold hopping [23].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Deep Learning Models in Molecular Generation

| Model | Approach | Validity (%) | Novelty (%) | Uniqueness (%) | Available Molecules (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMD-GEN (GCPG Module) [21] | Structure-Based | 95.8 | 91.4 | 99.3 | 86.1 |

| PGMG [14] | Ligand-Based | 94.6 | 93.5 | 98.7 | 87.3 |

| Syntalinker [21] | Ligand-Based (Fragment Linking) | 95.7 | 91.6 | 99.4 | 81.0 |

| SMILES LSTM [21] | Ligand-Based (Unconditional) | 96.1 | 85.1 | 99.4 | 79.8 |

| VAE [21] | Ligand-Based (Unconditional) | 62.3 | 81.6 | 98.2 | 50.9 |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling Protocol

The structure-based workflow, as detailed in literature [4], involves several critical steps to ensure the generation of a high-quality pharmacophore model.

- Protein Preparation: The process begins with obtaining and critically evaluating the 3D structure of the target protein from a database like the RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB). The preparation includes adding hydrogen atoms (absent in X-ray structures), correcting protonation states of residues, and addressing any missing atoms or residues. The stereochemical and energetic parameters are assessed to ensure the general quality and biological relevance of the structure [4].

- Ligand-Binding Site Detection: The next step is identifying the ligand-binding site. This can be done manually if co-crystallized ligand information is available or by using computational tools like GRID or LUDI. These tools analyze the protein surface to locate potential binding pockets based on geometric, energetic, or evolutionary properties [4].

- Pharmacophore Feature Generation: The binding site is analyzed to generate a map of potential interactions. Software tools identify key chemical features (e.g., hydrogen bond acceptors/donors, hydrophobic areas) that a ligand would need to complement the site. If a protein-ligand complex is available, the features are derived directly from the ligand's functional groups and their interactions with the receptor [4].

- Feature Selection and Model Creation: Initially, many features are detected. The final model is refined by selecting only the features that are essential for bioactivity. This can be achieved by removing features that do not strongly contribute to binding energy or by preserving interactions with residues known to have key functions from sequence alignments or mutagenesis studies. Exclusion volumes are added to represent the shape of the binding pocket and steric constraints [4].

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling Protocol

The ligand-based approach, as outlined in protocols [8], uses information from a set of known active compounds.

- Selection of Active Compounds: A training set of active compounds, validated experimentally for their potency against the target, is curated. The compounds should be structurally diverse to ensure the resulting model is not overly specific to a single scaffold [8].

- Generation of 3D Conformations: Multiple low-energy 3D conformations are generated for each active compound in the training set to account for ligand flexibility [8].

- Structural Alignment and Hypothesis Generation: The conformers of the training set compounds are superimposed through 3D alignment to identify the common spatial arrangement of chemical features (e.g., hydrogen bond acceptors, donors, hydrophobic groups) shared by all active molecules [8].

- Model Validation: The generated pharmacophore model is validated using a testing dataset containing both active compounds (true positives) and inactive compounds (decoys or false positives). The model's ability to correctly identify active compounds and reject inactive ones is assessed to ensure its predictive power before use in virtual screening [8].

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling Workflow

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful pharmacophore modeling and virtual screening rely on a suite of computational tools, software, and data resources. The table below details key solutions and their functions in the research process.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool/Resource Name | Type/Function | Key Use in Pharmacophore Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB) [4] | Structural Database | Primary source for experimentally determined 3D structures of proteins and protein-ligand complexes, essential for structure-based approaches. |

| ChEMBL [23] [14] | Bioactivity Database | Curated database of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties, providing data on known active ligands for ligand-based modeling and model validation. |

| LigandScout [8] | Commercial Software | Used for both structure-based and ligand-based pharmacophore modeling, offering advanced features for model creation and virtual screening. |

| Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) [8] | Commercial Software Suite | Integrated software platform that includes applications for pharmacophore modeling, molecular docking, QSAR, and other computational chemistry tasks. |

| Pharmer/Pharmit [8] | Open-Source Software & Web Server | Efficient tools for pharmacophore-based virtual screening, allowing researchers to screen large compound libraries against a pharmacophore query. |

| RDKit [23] [14] | Open-Source Cheminformatics Toolkit | Provides fundamental cheminformatics functionality, including pharmacophore feature identification, molecular descriptor calculation, and handling of chemical data. |

| ZINC [22] | Commercial Compound Database | Large, publicly accessible library of commercially available compounds, typically used as a screening library in virtual screening campaigns. |

| AlphaFold2 [4] | AI-based Structure Prediction | Provides highly accurate protein structure predictions when experimental structures are unavailable, expanding the scope of structure-based methods. |

Structure-based and ligand-based pharmacophore modeling are complementary pillars of computer-aided drug design. The structure-based approach offers a direct, target-centric strategy that is powerful when a reliable 3D protein structure is available, enabling the design of novel scaffolds and providing deep insights into binding interactions. The ligand-based approach provides a viable and efficient path forward when structural data is lacking, leveraging the collective chemical information of known actives to guide the discovery of new hits. As evidenced by recent AI-driven models like CMD-GEN and PGMG, both approaches continue to evolve, demonstrating high performance in generating valid, novel, and unique molecules. The choice between them is not a matter of superiority but is dictated by the specific research context—namely, the availability and quality of target structure data versus known ligand information. A strategic integration of both methods, where possible, often represents the most robust path to accelerating drug discovery and overcoming the challenges of lead compound identification and optimization.

In the field of computer-aided drug design, pharmacophore modeling serves as a crucial computational technique for identifying novel bioactive molecules. These models represent the essential three-dimensional arrangement of chemical features—such as hydrogen bond donors, acceptors, hydrophobic regions, and charged groups—necessary for biological activity against a specific molecular target [8]. Researchers primarily employ two distinct methodologies: structure-based pharmacophore modeling, which relies on the three-dimensional structure of the target protein, and ligand-based pharmacophore modeling, which derives key features from a set of known active ligands [8]. The strategic selection between these approaches is a critical first step that can significantly impact the success of a virtual screening campaign. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these methods, enabling researchers to make an informed choice based on their specific project constraints and available data.

Core Concepts and Methodologies

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

Structure-based pharmacophore modeling requires an experimentally determined or computationally modeled three-dimensional structure of the target protein, often in complex with a ligand. This approach directly extracts the spatial and electronic interaction patterns from the ligand-protein complex [24]. The process involves analyzing the binding pocket to identify key amino acid residues and mapping complementary chemical features that a potential drug molecule must possess to bind effectively [25]. The primary sources for these structures are the Protein Data Bank (PDB), obtained through techniques like X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, or Cryo-EM [6].

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

When the three-dimensional structure of the target protein is unknown or unresolved, ligand-based pharmacophore modeling becomes the method of choice. This technique identifies common chemical features and their spatial arrangements from a set of three or more known active molecules that bind to the same target [26] [24]. The underlying principle is that compounds sharing similar biological activities likely interact with the target in a similar fashion, and thus possess a common pharmacophore [27]. This method heavily depends on the quality, diversity, and biological activity data of the known active compounds used to generate the model.

Decision Framework: Choosing the Right Approach

The following table outlines the key decision criteria for selecting between structure-based and ligand-based pharmacophore modeling approaches.

| Criterion | Structure-Based Approach | Ligand-Based Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Requirement | 3D structure of the target protein (e.g., from PDB) [6] | Set of known active ligands with confirmed biological activity [26] [27] |

| Ideal Application Scenario | Target structure is available; aiming for scaffold hopping to discover novel chemotypes [24] | Target structure is unknown; sufficient known actives are available to define common features [6] |

| Key Advantage | Directly reveals interaction points with the target; not limited by existing ligand chemotypes [28] | Does not require protein structural data; can leverage existing structure-activity relationship (SAR) data [6] |

| Main Limitation | Dependency on the quality and conformational state of the protein structure [6] | Bias towards the chemical space of known ligands; requires multiple diverse actives for robust models [10] |

| Typical Virtual Screening Hit Rate | Reported hit rates often range from 5% to 40% in successful prospective studies [24] | Performance varies significantly with the quality and diversity of the training set molecules [27] |

Experimental Workflows and Validation

Structure-Based Workflow

The typical workflow for a structure-based pharmacophore modeling campaign involves several key stages, from preparing the protein structure to the final experimental validation of hits. The diagram below illustrates this sequential process.

Detailed Methodologies for Structure-Based Approaches:

- Protein Structure Preparation: The process begins with obtaining a high-quality 3D structure (e.g., PDB ID: 6R3K for PD-L1) [29]. The protein structure is prepared by adding hydrogen atoms, assigning correct protonation states, and optimizing the hydrogen bonding network using software like Discovery Studio or MOE [25].

- Pharmacophore Model Generation: Using the prepared structure, interaction points between the protein and a co-crystallized ligand are mapped. For instance, in a study targeting XIAP, the software LigandScout was used to generate a model containing 14 features, including hydrophobics, hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, and positive ionizable features, based on the protein-ligand complex (PDB: 5OQW) [25].

- Model Validation: Before virtual screening, the model is validated for its ability to distinguish active compounds from inactive ones. This is typically done using a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. A high area under the curve (AUC) value, such as 0.98 reported in the XIAP study, indicates excellent model quality [25].

- Virtual Screening and Hit Identification: The validated model is used as a query to screen large compound databases (e.g., ZINC, Marine Natural Product libraries). Hits that match the pharmacophore features are then subjected to molecular docking to refine the selection based on binding affinity and interaction patterns [29] [25].

Ligand-Based Workflow

The ligand-based approach follows a different workflow, centered on the curation and analysis of known active compounds, as illustrated below.

Detailed Methodologies for Ligand-Based Approaches:

- Training Set Preparation: A set of known active compounds, preferably with high and well-characterized activity (e.g., IC50 < 50 nM for carbonic anhydrase IX inhibitors), is collected [26]. This set should include structurally diverse molecules to create a robust model. Inactive compounds are also valuable for validation.

- Model Generation and Feature Selection: The 3D structures of the active compounds are generated, and their conformational flexibility is sampled. The molecules are then aligned, and common chemical features are identified. For example, a model for carbonic anhydrase IX inhibitors was built using seven active compounds, resulting in a top model with two aromatic hydrophobic centers and two hydrogen bond donor/acceptors [26].

- Validation with Decoy Sets: The model is validated using an external test set containing known active molecules and decoy molecules (assumed inactives) from databases like DUD-E. This tests the model's ability to correctly identify actives (sensitivity) and reject inactives (specificity) [26] [24].

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

The table below summarizes quantitative performance metrics from published studies utilizing both approaches, providing a realistic expectation of their effectiveness.

| Study Target | Approach Used | Key Metric | Reported Result | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PD-L1 | Structure-Based | AUC (Model Validation) | 0.819 | [29] |

| PD-L1 | Structure-Based | Binding Affinity (Top Hit) | -6.5 kcal/mol | [29] |

| XIAP | Structure-Based | AUC (Model Validation) | 0.98 | [25] |

| XIAP | Structure-Based | Early Enrichment Factor (EF1%) | 10.0 | [25] |

| Carbonic Anhydrase IX | Ligand-Based | Binding Affinity (Top Hits) | -7.8 kcal/mol (Avg.) | [26] |