Strategies for Enhancing Synthetic Accessibility in Anticancer Drug Discovery: From AI Prediction to Laboratory Synthesis

This article addresses the critical challenge of synthetic accessibility in modern anticancer drug discovery, where computationally predicted compounds often prove difficult or impractical to synthesize.

Strategies for Enhancing Synthetic Accessibility in Anticancer Drug Discovery: From AI Prediction to Laboratory Synthesis

Abstract

This article addresses the critical challenge of synthetic accessibility in modern anticancer drug discovery, where computationally predicted compounds often prove difficult or impractical to synthesize. Targeting researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we explore foundational concepts of synthetic accessibility scoring, methodological applications of machine learning and computational tools, optimization strategies for complex lead compounds, and validation frameworks for assessing synthetic feasibility. By integrating insights from recent advances in computer-assisted synthesis planning, natural product optimization, and AI-enabled virtual screening, this comprehensive review provides a practical framework for bridging the gap between computational prediction and experimental realization of novel anticancer therapeutics.

Understanding Synthetic Accessibility: Why Predicted Anticancer Compounds Often Fail in the Lab

Defining Synthetic Accessibility in Anticancer Drug Discovery

Core Concepts and Definitions

What is synthetic accessibility (SA) in the context of anticancer drug discovery?

Synthetic Accessibility (SA) refers to how easy or difficult it is to synthesize a given small molecule in the laboratory, considering practical limitations like available building blocks, feasible reaction types, and molecular complexity [1]. In anticancer drug discovery, a molecule may show promising biological activity in computer models but prove impractical if it cannot be synthesized efficiently. SA provides a practical metric to prioritize drug candidates that are not only biologically active but also feasible to produce [1].

What is the difference between synthetic accessibility and molecular complexity?

While related, these concepts are distinct. Molecular complexity typically refers to structural features such as multiple functional groups, complex ring systems, or numerous chiral centers [2]. Synthetic accessibility encompasses complexity but also considers practical synthetic factors like the availability of starting materials and known reaction pathways [2]. A structurally complex molecule might be synthetically accessible if it can be prepared from readily available precursors in few steps, whereas a simpler molecule might be hard to synthesize if it requires rare starting materials or difficult reactions [2].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Why is assessing synthetic accessibility crucial in anticancer drug discovery?

- Feasibility and Cost: Difficult-to-synthesize molecules require more time, expensive reagents, and labor, increasing development costs prohibitively [1].

- Iteration Speed: Drug discovery is cyclical (design → synthesize → test → refine). Slow synthesis creates bottlenecks that delay the entire process [1].

- Scale-Up and Manufacturability: A synthesis feasible at milligram scale for initial testing may not be viable at the kilogram scale required for manufacturing, due to issues with yield, purification, or cost of starting materials [1].

- Risk Mitigation: Early SA assessment helps avoid investing resources in biologically promising molecules that are ultimately impractical to synthesize [1].

How do computational SA scores correlate with a medicinal chemist's assessment?

Studies show a good agreement between the average scores given by groups of experienced medicinal chemists and computational predictions [3]. However, individual chemists may show significant variation based on their personal experience. Therefore, computational tools are best used to rank and prioritize compounds on a large scale, while consultation with a team of chemists is recommended for final candidate selection to avoid individual bias [3].

What are the main limitations of current computational SA prediction tools?

- Approximation, Not Guarantee: SA predictions are approximations and do not guarantee a viable synthetic route [1].

- Lagging Knowledge: Models may not incorporate the latest synthetic methodologies, so a molecule labeled "hard to synthesize" might be accessible using novel, specialized chemistry [1].

- Economic Blind Spots: Most tools do not consider the cost of starting materials, reaction yields, or challenges associated with scaling up a synthesis [1].

- Over-Pessimism: Rule-based methods might incorrectly label a molecule containing fragments not in their database as hard to synthesize, even if those fragments are available as building blocks [4].

How can I improve the synthetic accessibility of a compound predicted to be hard to make?

- Simplify the Structure: Reduce the number of stereocenters, complex ring systems (especially fused or bridged rings), and the count of different functional groups [1].

- Replace Rare Fragments: Identify and substitute molecular fragments that are flagged as rare or complex with more common, synthetically straightforward bioisosteres [4] [1].

- Incorporate Symmetry: Designing symmetric or modular molecules can simplify synthesis, as parts can be reused or assembled from simpler, common intermediates [1].

Quantitative Data and Tool Comparison

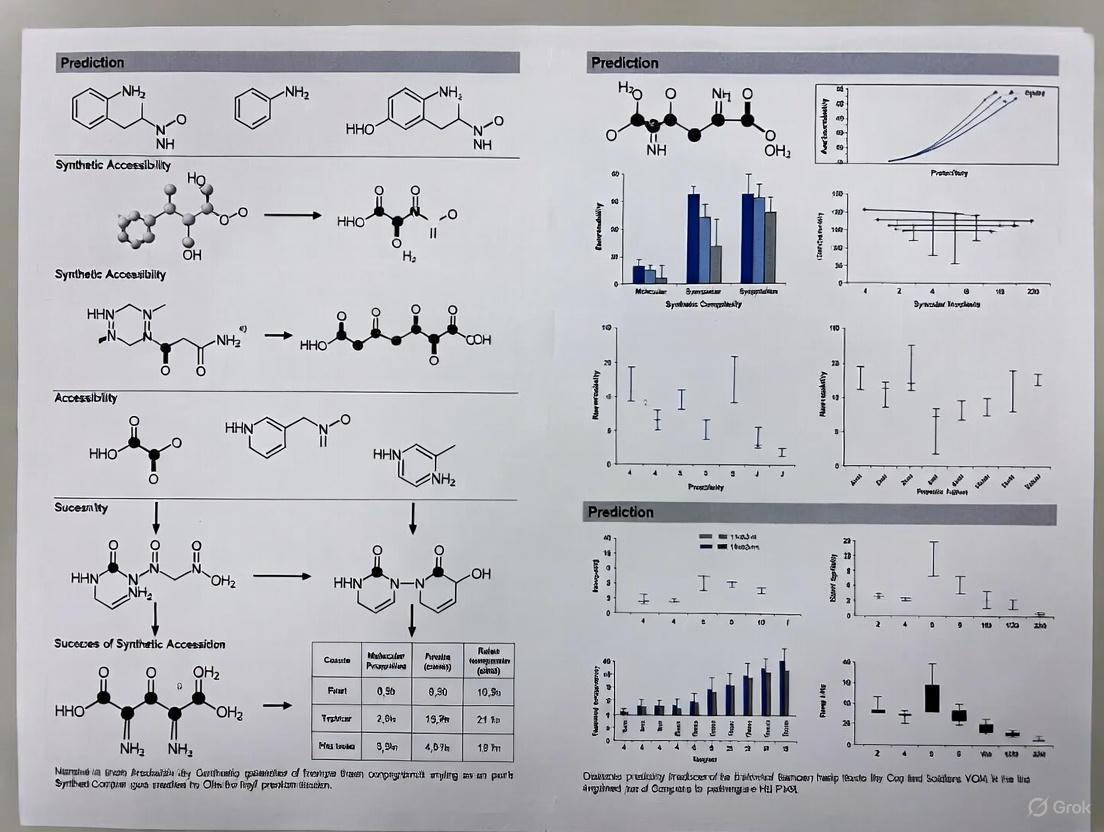

The field has both traditional rule-based methods and modern machine learning (ML)/deep learning (DL) driven approaches. The table below summarizes key SA prediction tools.

Table 1: Comparison of Synthetic Accessibility Prediction Methods

| Tool Name | Underlying Approach | Key Features | Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| SAScore [4] [2] [1] | Rule-based/Fragment Frequency | Scores molecules based on fragment commonness in PubChem and a complexity penalty. Fast calculation. | Score (typically 1-10) |

| SYBA [5] [2] | Machine Learning (Bayesian Classifier) | Classifies molecules as easy- or hard-to-synthesize based on fragments from purchasable (ZINC) and generated (Nonpher) databases. | ES/HS Classification & Probability |

| SCScore [5] [2] | Deep Learning (Neural Network) | Trained on reactant-product pairs from Reaxys. Correlates score with the number of reaction steps. | Score (1-5) |

| RAscore [5] [4] | Machine Learning (Neural Network) | Predicts the likelihood that a synthesis route can be found by the synthesis planning program AiZynthFinder. | Classification Score |

| GASA [5] | Deep Learning (Graph Neural Network) | Uses graph attention mechanisms to capture the local atomic environment and bond features of a molecule. | ES/HS Classification |

| DeepSA [5] | Deep Learning (Chemical Language Model) | A model trained on SMILES strings using NLP algorithms. Reported high accuracy (AUROC: 89.6%) in discriminating HS molecules. | ES/HS Classification & Probability |

| BR-SAScore [4] | Rule-based/Reaction-Aware | An enhancement of SAScore that explicitly uses known building block and reaction information from synthesis planners. | Score |

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Various Models on Independent Test Sets (Based on AUROC) [5]

| Model | TS1 | TS2 | TS3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| DeepSA | 0.927 | 0.896 | 0.764 |

| GASA | 0.899 | 0.858 | 0.789 |

| SYBA | 0.866 | 0.799 | 0.697 |

| RAscore | 0.822 | 0.783 | 0.668 |

| SCScore | 0.703 | 0.699 | 0.623 |

| SAScore | 0.688 | 0.666 | 0.614 |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol 1: Implementing a Standard SA Assessment Workflow Using Multiple Tools

This protocol describes a consensus approach to evaluate the synthetic accessibility of a set of candidate anticancer molecules.

I. Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for SA Assessment

| Resource / Reagent | Function / Description | Example / Source |

|---|---|---|

| Compound Structures | The input for all SA assessments. | Provided in a standardized format (e.g., SMILES strings, SDF files). |

| SA Prediction Software/Tool | Executes the core calculation. | RDKit (for SAScore), Standalone implementations of SYBA, SCScore, DeepSA, etc. [5] [1]. |

| Scripting Environment | Automates the process of running multiple tools and aggregating results. | Python (with libraries like RDKit, Pandas, NumPy) or a Knime workflow. |

| Visualization Software | Helps interpret results, especially for fragment-based or explainable AI methods. | CheS-Mapper, RDKit, or in-house dashboards. |

II. Step-by-Step Procedure

- Input Preparation: Compile the structures (SMILES) of the candidate molecules into a single, clean file (e.g., .smi or .sdf).

- Tool Selection and Execution: Run the input file through a panel of SA tools. A recommended panel includes:

- One fast, rule-based method (e.g., SAScore or BR-SAScore).

- One ML/DL-based classifier (e.g., DeepSA or SYBA).

- One retrosynthesis-based method if computational resources and time allow (e.g., RAscore).

- Data Aggregation: Collect all outputs (scores, classifications, probabilities) into a single spreadsheet or database table.

- Consensus Analysis: Rank the molecules based on the consensus from the different tools. For example, prioritize molecules that are consistently labeled "ES" or have favorable scores across all tools.

- Visual Inspection and Interpretation: For molecules flagged as "HS" or with poor scores, use interpretable tools (like SYBA or BR-SAScore) to identify the problematic fragments or structural features contributing to the low score [4] [1].

- Reporting: Document the results, including the final ranked list and a summary of the structural features that make certain compounds hard to synthesize.

The following diagram illustrates this workflow:

SA Assessment Workflow

Protocol 2: Methodology for Training a Deep Learning-Based SA Predictor (DeepSA)

This protocol summarizes the method used to develop the DeepSA model, a state-of-the-art predictor for synthetic accessibility [5].

I. Research Reagent Solutions

- Training Dataset: A curated set of 800,000 molecules, with labels (ES/HS) assigned by the retrosynthetic planning algorithm Retro* and from the SYBA dataset [5].

- Software Framework: Deep learning frameworks like PyTorch or TensorFlow for implementing Natural Language Processing (NLP) algorithms.

- Representation: Molecules are represented as SMILES strings, which are treated as sentences for the chemical language model.

- Independent Test Sets: Three distinct test sets (TS1, TS2, TS3) from previously published works to evaluate model generalizability [5].

II. Step-by-Step Procedure

- Data Collection and Labeling:

- Collect a large dataset of molecules (e.g., 3.5 million for pre-training).

- Label molecules as Easy-to-Synthesize (ES) if they require ≤10 synthetic steps (as predicted by Retro*), or as Hard-to-Synthesize (HS) if they require >10 steps or if no route is found [5].

- Data Preprocessing and Augmentation:

- Convert all molecular structures to canonical SMILES strings.

- Apply advanced sampling by generating different SMILES representations for the same molecule to augment the dataset and improve model robustness [5].

- Model Training:

- Train a chemical language model (e.g., based on LSTM or Transformer architectures) on the pre-training dataset to learn the grammar of chemistry.

- Fine-tune the model on the labeled ES/HS dataset (800,000 molecules), treating the task as a binary classification problem.

- Model Evaluation:

- Test the model's performance on the held-out test set and independent test sets (TS1-TS3).

- Use metrics such as Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F-score, and Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUROC) to benchmark against other methods [5].

The workflow for building a model like DeepSA is shown below:

DeepSA Model Training

In modern anti-cancer drug discovery, computer-aided drug design (CADD) employs sophisticated computational approaches to predict the efficacy of potential drug compounds and identify the most promising candidates for development [6]. Techniques such as molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulations, and QSAR analysis have become essential tools, reducing research costs and accelerating development [7]. Despite these advancements, a critical bottleneck persists: the transition from in silico prediction to successful laboratory synthesis. This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help researchers navigate and overcome these synthesis challenges, enhancing the synthetic accessibility of predicted anti-cancer compounds.

FAQs: Navigating Synthesis Challenges

1. What is synthetic accessibility (SA) and why is it a bottleneck in anti-cancer drug discovery? Synthetic Accessibility (SA) is a formal molecular property that estimates how easily a molecule can be synthesized under real laboratory conditions [8]. It is a more abstract but critical consideration than many chemoinformatics descriptors. The bottleneck exists because virtually designed molecules, despite promising predicted biological activity, often present significant practical challenges to synthesize, delaying the development of new anti-cancer therapies [4] [8].

2. What computational methods are available to predict synthetic accessibility? SA prediction methods generally fall into three categories [8]:

- Complexity-Based Methods: These fast-scoring methods use molecular descriptors (e.g., ring complexity, stereocenters) to estimate synthetic difficulty. A common model is SAScore, which combines fragment popularity from databases like PubChem with a complexity penalty [4] [8].

- Retrosynthetic Analysis-Based Methods: These use chemical knowledge to deconstruct a target molecule into available precursors. While considered highly accurate by medicinal chemists, they are computationally intensive and slow, making them impractical for high-throughput screening [8].

- Starting Materials-Based Methods: These evaluate SA by assessing the overlap between the target compound and available starting material libraries [8]. Newer approaches like BR-SAScore enhance traditional methods by integrating specific building block information and reaction knowledge directly into the scoring process, offering more chemically interpretable results [4].

3. A generative model proposed a novel compound with excellent predicted activity against PLK1, but it has a high synthetic accessibility (SA) score, indicating it is hard to make. What should I do? A high SA score suggests structural complexity that may be difficult to achieve in the lab. Recommended actions include:

- Scaffold Simplification: Use bioisosteric replacements or scaffold hopping to replace complex, synthetically challenging fragments with simpler, more common isosteres that maintain the desired binding interactions [7].

- Analogue Screening: Screen the generated chemical space for analogues or precursors with similar predicted activity but lower SA scores. A molecule with slightly lower computed potency but significantly higher synthetic accessibility is often a more viable drug candidate.

- Retrosynthetic Analysis: Run the structure through a dedicated synthesis planning program (e.g., AizynthFinder, Retro*) to identify the specific structural motif causing the synthesis failure and target that for modification [4].

4. My molecular dynamics simulations show a candidate binds well to the PD-L1 protein, but our chemists say the macrocyclic core is synthetically inaccessible. How can we resolve this? This is a common disconnect between prediction and synthesis. To bridge this gap:

- Utilize SA Filters: Integrate a fast, rule-based SA score (like SAScore or BR-SAScore) early in your virtual screening workflow to filter out molecules with obvious red flags like large macrocycles, many stereocenters, or complex bridged ring systems [4] [8].

- Ligand-Based Design: If a known active macrocyclic compound exists, use ligand-based techniques like molecular morphing to generate a virtual library of compounds that are structurally similar but synthetically more feasible [8].

- Focus on Fragments: Consider developing smaller, synthetically accessible fragments that target the key interaction sites (hot spot residues) of the PD-L1/PD-1 interaction, which can later be optimized into larger compounds [7].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: High Synthetic Complexity Score

Symptoms:

- Computational SA tools (e.g., SAScore, Ambit-SA) flag the molecule with a high complexity penalty [8].

- The molecule contains multiple stereocenters, bridged or spiro ring systems, or a macrocycle [8].

Diagnosis and Resolution:

| Step | Action | Methodology & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Calculate Complexity | Use a tool like Ambit-SA to calculate the components of the SA score. The formula is often SA = f(SRC, Sμ, SWSC, SCM), where SRC is Ring Complexity, Sμ is Cyclomatic number, SWSC is Stereochemical Complexity, and SCM is Molecular Complexity [8]. |

| 2 | Identify Structural Alerts | Analyze which component contributes most to the high score. A high SWSC indicates too many chiral centers; a high SRC indicates fused or bridged ring systems [8]. |

| 3 | Apply Structural Simplification | Perform scaffold hopping or bioisosteric replacement. For example, Crocetti et al. successfully used this ligand-based technique to develop more synthetically accessible FABP4 inhibitors by starting from a known pyrimidine ligand [7]. |

| 4 | Re-evaluate | Re-calculate the SA score and re-run the activity prediction (e.g., molecular docking) for the simplified analogue to ensure potency is retained. |

Problem: Unavailable or Exotic Building Blocks

Symptoms:

- Retrosynthetic analysis software cannot find a route from available commercial building blocks.

- The molecule contains uncommon or proprietary molecular fragments not listed in major chemical supplier databases.

Diagnosis and Resolution:

| Step | Action | Methodology & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Fragment Analysis | Deconstruct the molecule into its core fragments. Tools like BR-SAScore can help differentiate fragments inherent in building blocks (BFrags) from those formed by reactions (RFrags) [4]. |

| 2 | Database Search | Screen the identified uncommon fragments against databases of available starting materials (e.g., ZINC, PubChem) [8]. |

| 3 | Fragment Replacement | Replace the inaccessible fragment with a functionally similar and commercially available bioisostere. The key is to maintain similar electronic and steric properties. |

| 4 | Virtual Screening | Use the modified, accessible fragment as a query for a similarity-based virtual screen of a compound library (e.g., FDA-approved drugs for repurposing) to find existing compounds with the desired motif [7]. |

Problem: Inefficient Multi-Step Synthesis

Symptoms:

- Computer-Aided Synthesis Planning (CASP) proposes a synthesis route with >10 steps.

- The reported overall yield for the synthesis is very low (<1%).

Diagnosis and Resolution:

| Step | Action | Methodology & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Route Analysis | Use a synthesis planning program (e.g., AizynthFinder, Retro*) to generate multiple possible synthetic routes [4]. |

| 2 | Identify Strategic Bonds | Analyze the routes to find the "strategic bonds" where the molecule is split. Software like SYLVIA can assess these bonds to suggest simpler disconnections [8]. |

| 3 | Prioritize Convergent Synthesis | Redesign the route to be convergent rather than linear. A convergent synthesis, where complex fragments are built separately and combined late, typically has a higher overall yield than a long linear sequence. |

| 4 | Validate & Optimize | Use the "follow-the-path" approach to trace the synthesis path, isolate, and optimize the lowest-yielding step[suppressed:citation:3]. |

Experimental Protocols & Data

Quantitative Comparison of SA Prediction Methods

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of different synthetic accessibility prediction approaches, helping you select the right tool for your project.

| Method | Approach | Speed | Key Features | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAScore [8] | Complexity & Fragment-Based | Very Fast | Combines fragment frequency from PubChem with complexity penalty (rings, stereocenters). | Initial, high-throughput filtering of large virtual libraries. |

| BR-SAScore [4] | Building Block & Reaction-Aware | Fast | Enhances SAScore by integrating known building blocks (B) and reaction (R) knowledge from synthesis planners. | Screening with a specific set of available starting materials in mind. |

| Ambit-SA [8] | Descriptor-Based | Fast | Uses an additive scheme of 4 weighted molecular descriptors: Ring Complexity, Cyclomatic Number, Stereochemical Complexity, and Molecular Complexity. | Getting a quick, interpretable score and complexity breakdown. |

| RAScore [4] | Machine Learning | Moderate | A machine learning model trained on outcomes from a synthesis planner (AizynthFinder). | Predicting the likelihood that a synthesis planner can find a route. |

| Retrosynthetic Analysis (e.g., Retro* [4]) | Reaction-Based | Slow (minutes/hours per molecule) | Uses chemical knowledge to find actual synthetic routes; considered the gold standard for feasibility. | Final-stage validation of synthesis routes for a few top candidates. |

Key Workflow: Integrating SA into Anti-Cancer Drug Design

This workflow diagram illustrates how to embed synthetic accessibility assessment at key stages of the anti-cancer drug design process to mitigate the prediction-synthesis bottleneck.

Diagram: The SA Scoring Logic of a Rule-Based Method

The following diagram details the internal logic of a typical rule-based synthetic accessibility scoring function, such as SAScore or Ambit-SA.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Resource | Function in Research | Example in Anti-Cancer Drug Design |

|---|---|---|

| Computer-Aided Synthesis Planning (CASP) | Software to predict viable synthetic routes for a target molecule. | AizynthFinder or Retro* can be used to plan the synthesis of a novel HDAC3 or PLK1 inhibitor identified by virtual screening [4]. |

| Synthetic Accessibility (SA) Prediction Tools | Fast computational filters to estimate the ease of synthesis. | Using SAScore or BR-SAScore to prioritize flavonoid-based MEK1 inhibitors that are not only potent but also synthetically tractable [7] [4]. |

| Building Block Libraries | Databases of commercially available chemical starting materials. | Screening a library of FDA-approved drugs (as a source of accessible building blocks) for drug repurposing, as done to identify Etravirine as a CK1ε inhibitor [7]. |

| Molecular Dynamics Software | Simulates the dynamic behavior of molecules over time to assess stability. | Used to confirm the stable binding mode of a designed PD-L1 small molecule binder over a 100 ns simulation, validating the docking prediction before synthesis [7]. |

| Retrosynthetic Analysis Algorithms | Core logic in CASP that recursively breaks down a target molecule into simpler precursors. | Essential for deconstructing a complex FABP4 inhibitor candidate to identify if its core scaffold can be built from known precursors using known reactions [8]. |

In modern anticancer drug discovery, molecular complexity is a fundamental property that influences synthetic accessibility, biological activity, and the success of lead optimization campaigns. Quantifying complexity is a long-standing challenge in chemistry, largely based on intuitive perception and lacking a standardized numerical measure [9]. However, the ability to capture human-assessed molecular complexity is increasingly valuable in medicinal chemistry, where drug-like molecules tend to have more complex structures [9]. This technical support center provides practical guidance for researchers navigating the intricate relationship between molecular complexity and synthetic accessibility in predicted anticancer compounds.

Quantifying Molecular Complexity: A Machine Learning Framework

Core Quantitative Descriptors

Recent advances have enabled the digitization of molecular complexity using machine learning approaches. The table below summarizes key molecular descriptors identified as major contributors to complexity assessments by expert chemists [9].

Table 1: Key Molecular Descriptors for Complexity Assessment

| Molecular Descriptor | Impact on Complexity | Measurement Method |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Weight | Highest impact feature; correlates with size and structural intricacy | Mass calculation from atomic constituents |

| Number of Aromatic Rings | Second most important feature; indicates conjugation and planarity | Count of aromatic cycles in structure |

| Topological Polar Surface Area (TPSA) | Third most significant descriptor; reflects polarity and potential hydrogen bonding | Calculation based on polar atom contributions |

| SCScore | Synthetic complexity score; quantifies synthetic accessibility | Machine learning-based algorithm |

Experimental Workflow for Complexity Quantification

The machine learning framework for molecular complexity quantification employs a Learning to Rank approach trained on approximately 300,000 data points across diverse chemical structures [9]. This methodology captures the complex decision rules that researchers intuitively use when assessing molecular complexity.

Diagram 1: Complexity Quantification Workflow

Troubleshooting Guides: Managing Complexity in Synthesis

FAQ: Ring System Complexity

Q: How do ring systems specifically contribute to molecular complexity? A: Ring systems significantly increase molecular complexity by introducing conformational constraints, potential for stereoisomers, and increased synthetic steps. Machine learning models identify the number of aromatic cycles as the second most important feature affecting expert complexity assessments, following only molecular weight [9]. In anticancer compounds like Taxol, complex ring systems are fundamental to biological activity but present substantial synthetic challenges [10].

Q: What strategies can simplify complex ring system assembly? A: Employ convergent synthetic approaches that assemble pre-formed ring fragments rather than constructing rings linearly. This strategy was successfully implemented in the total synthesis of Taxol, where multiple fragments containing complex ring systems were assembled via a series of complex reactions [10].

FAQ: Stereochemical Complexity

Q: How does stereochemistry impact synthetic planning? A: Each stereocenter potentially doubles the number of possible stereoisomers, exponentially increasing synthetic challenges. Controlling stereochemistry requires specialized strategies including chiral starting materials, auxiliaries, and stereoselective reactions such as asymmetric hydrogenation or aldol reactions [10].

Q: What methods effectively control stereochemistry in complex molecules? A: Three primary strategies have proven effective:

- Use of chiral catalysts or ligands for enantioselective synthesis

- Diastereoselective reactions using substrate-controlled induction

- Conformationally restricted intermediates to guide stereochemical outcomes [10]

FAQ: Functional Group Management

Q: How do functional groups contribute to overall molecular complexity? A: Beyond their chemical reactivity, functional groups influence complexity through stereoelectronic effects, polarity, hydrogen bonding capacity, and potential for protecting group strategies. The Topological Polar Surface Area (TPSA), which quantifies polar atom contributions, ranks as the third most important complexity descriptor in expert assessments [9].

Q: What protecting group strategies best manage functional group complexity? A: Optimal protecting group strategies prioritize:

- Orthogonality (independent deprotection without affecting other groups)

- Stability under reaction conditions

- Ease of installation and removal

- Minimal impact on molecular properties during synthesis

Strategic Approaches to Complexity Management

Synthetic Planning Methodologies

Effective management of molecular complexity requires strategic synthetic planning. The following diagram illustrates key decision points in developing synthetic routes for complex anticancer targets.

Diagram 2: Synthetic Planning Decision Tree

Research Reagent Solutions for Complexity Management

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Managing Molecular Complexity

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Complexity Management |

|---|---|---|

| Chiral Catalysts | Bisphosphine ligands, BINOL derivatives | Enable stereoselective synthesis of complex stereocenters |

| Cross-Coupling Catalysts | Palladium complexes (Suzuki, Heck, Sonogashira) | Facilitate key C-C bond formations in ring systems |

| Protecting Groups | TBPS, Boc, Fmoc, Acetal groups | Temporarily mask reactive functional groups during synthesis |

| Stereoselective Reagents | CBS catalyst, Sharpless epoxidation reagents | Control absolute stereochemistry in complex molecule synthesis |

Case Study: Complexity Management in Anticancer Pyrimidine Derivatives

The development of 2-thiopyrimidine-5-carbonitrile derivatives as thymidylate synthase inhibitors exemplifies practical complexity management in anticancer research [11]. These compounds incorporate multiple complexity elements:

Structural Features:

- Heteroaromatic ring system (pyrimidine core)

- Multiple nitrogen heteroatoms

- Thiocarbonyl and nitrile functional groups

- Varied substitution patterns

Synthetic Strategy: The synthesis employed functional group interconversions and protecting group strategies to manage reactivity while constructing the complex heterocyclic framework [11]. This approach enabled efficient production of compounds with remarkable antiproliferative activity against MCF-7, A549, and HepG2 cell lines.

Molecular complexity remains an intrinsic property of every organic molecule with profound implications for anticancer drug development [9]. By understanding and quantifying the impact of ring systems, stereocenters, and functional groups, researchers can make informed decisions that balance complexity with synthetic accessibility. The frameworks, troubleshooting guides, and strategic approaches presented here provide practical support for enhancing synthetic accessibility in predicted anticancer compounds research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: How can historical synthetic data from databases like PubChem accelerate my anticancer drug discovery research?

Leveraging historical synthetic data can prevent redundant efforts and provide a wealth of starting points for new compounds. Analyzing existing structures and their synthetic pathways can reveal under-explored chemical space and promising scaffolds with known anticancer activity [12]. For instance, natural products and their synthetic analogs have long been a primary source of anticancer drugs, with over 60% of synthetic drugs derived from natural sources [13]. By studying these known entities, researchers can design novel compounds with improved properties.

FAQ 2: A synthesized natural product analog shows poor bioavailability in initial tests. What are common strategic modifications to address this?

Simple chemical modifications to the parent molecule can significantly enhance its pharmacological profile. Common strategies include:

- Ketalization/Acetalation: Can improve metabolic stability.

- Esterification (Acetylation): Often used to create prodrugs with better absorption.

- Silylation: Installing silyl ether groups can alter the compound's lipophilicity and stability [14]. These approaches have been successfully demonstrated with cardiac glycosides like proscillaridin A, where analogs bearing acetate esters, dimethyl ketals, or silyl ethers were synthesized and showed retained or enhanced in vitro anticancer potency [14].

FAQ 3: When exploring new chemical space for anticancer agents, what do the fragment statistics in PubChem suggest about the potential for novelty?

The exponential growth in chemistry is reflected in the vast number of unique chemical fragments. An analysis of PubChem identified 28,462,319 unique atom environments (fragments) across 46 million structures [12]. However, a key finding is that nearly half of these fragments are "singletons," meaning they appear in only a single chemical structure. This, coupled with the observation that larger fragments are often novel combinations of smaller, common fragments, indicates there is substantial opportunity for chemists to create novel compounds by connecting known fragments in new ways [12].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

| Issue | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Antiproliferative Activity in Novel Synthetic Compound | The new molecular scaffold may not interact with the intended biological target. | Utilize historical data to incorporate fragments from compounds with known activity against your target. Consider employing innovative synthetic methodologies like C-H activation or multicomponent reactions to efficiently generate diverse analogs for structure-activity relationship (SAR) study [15]. |

| Inconsistent Biological Replication | Inefficient or low-yielding synthetic pathway leading to impurities or insufficient material. | Consult databases for established high-yield reactions or analogous synthetic pathways. Modern cross-coupling reactions are pivotal for efficiently constructing complex aromatic systems often found in bioactive molecules [15]. |

| Poor Aqueous Solubility of Lead Compound | High lipophilicity (logP) of the synthetic molecule. | Refer to strategies used for known natural products. Synthetic modification of the glycan or core structure with polar functional groups can be explored, similar to the glycosylation of cardiac glycosides or the creation of more soluble prodrugs [15] [14]. |

Key Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Protocol: Evaluating Antiproliferative Activity of Synthetic Analogs

This methodology is used to assess the in vitro potency of newly synthesized compounds against cancer cell lines.

Detailed Methodology:

- Cell Culture: Maintain human cancer cell lines (e.g., HCT-116 colorectal carcinoma, SK-OV-3 ovarian adenocarcinoma) in appropriate media under standard conditions (37°C, 5% CO₂) [14].

- Compound Treatment: Seed cells in multi-well plates. The following day, treat the cells with a range of concentrations of the test compounds, including the parent natural product (e.g., proscillaridin A) and its novel synthetic analogs (e.g., ketals, silyl ethers). Include a vehicle control (e.g., DMSO) [14].

- Viability Assay: After a set incubation period (e.g., 24, 48, and 72 hours), measure cell viability using a standard assay like MTT or WST-1. These assays measure the activity of mitochondrial enzymes, which correlates with the number of viable cells.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the percentage of viable cells for each treatment compared to the vehicle control. Plot dose-response curves and determine the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC₅₀) value for each compound, which represents the concentration required to inhibit cell proliferation by 50% [14].

Quantitative Data from Proscillaridin A Analog Study (72h Treatment) [14]:

Table 1: In vitro antiproliferative activity (IC₅₀ in μM) of proscillaridin A and its synthetic analogs.

| Compound | Modification Type | HCT-116 (Colorectal) | HT-29 (Colorectal) | SK-OV-3 (Ovarian) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proscillaridin A (Parent) | - | Data not specified in excerpt | Data not specified in excerpt | Data not specified in excerpt |

| Triacetate 4 | Acetylation | 0.132 μM | 1.230 μM | 0.001 μM |

| Acetonide 5 | Ketalization | 0.004 μM | 0.026 μM | 0.003 μM |

| Acetyl Acetonide 6 | Ketalization & Acetylation | 0.443 μM | 0.096 μM | Data not specified in excerpt |

| Digoxin (Control) | - | Data not specified in excerpt | Data not specified in excerpt | Data not specified in excerpt |

Workflow: Utilizing PubChem for Synthetic Planning

The following diagram outlines a logical workflow for leveraging PubChem data in the design of new synthetic anticancer compounds.

Diagram: Strategic Modification of a Natural Product Lead

This diagram illustrates the specific synthetic modifications applied to the natural product proscillaridin A to generate novel analogs for biological testing [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key reagents and materials for the synthesis and evaluation of anticancer natural product analogs.

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Example from Context |

|---|---|---|

| Acetic Anhydride | Acetylation agent for installing acetate ester groups on hydroxyl moieties to alter bioavailability and metabolic stability. | Used to synthesize Triacetate 4 from proscillaridin A [14]. |

| 2,2-Dimethoxypropane | Ketalization agent used to protect diols, forming a cyclic acetonide, which can improve metabolic stability. | Used with catalytic PPTS to synthesize Acetonide 5 from proscillaridin A [14]. |

| Tert-Butyldimethylsilyl Chloride (TBSCl) | Silylating agent used to create silyl ethers, protecting alcohol groups and significantly increasing compound lipophilicity (logP). | Used to create silylated analogs (Siloxy Acetonide 7, Bis-Siloxy 8) of proscillaridin A [14]. |

| Transition Metal Catalysts (Rh, Pd) | Catalyze innovative C-H activation/functionalization reactions, enabling direct modification of complex molecules without the need for pre-functionalization. | Pivotal for the cleavage and transformation of C-H bonds in the synthesis of natural products and pharmaceuticals [15]. |

| Cancer Cell Line Panel | In vitro model system for initial high-throughput screening of compound antiproliferative activity across different tissue types. | Used to evaluate synthesized analogs on colorectal (HCT-116, HT-29), ovarian (SK-OV-3), and liver (HepG2) cancer cells [14]. |

| PubChem / Chemical Databases | Open archives of chemical structures and biological activities used for structure searching, fragment analysis, and leveraging historical synthetic knowledge. | Source for analyzing 28+ million unique atom environments to guide novel compound design [12]. |

Economic and Practical Implications of Poor Synthetic Accessibility

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is synthetic accessibility and why is it a critical parameter in anticancer drug discovery? Synthetic accessibility refers to the ease and feasibility with which a chemical compound can be synthesized in the laboratory. In anticancer drug discovery, a molecule's promising biological activity is irrelevant if it cannot be practically and economically synthesized for testing and development [16]. Poor synthetic accessibility can halt promising research projects, as the compound cannot be produced to validate its anticancer properties or to scale up for preclinical and clinical studies.

2. What are the common structural features that make an anticancer compound difficult to synthesize? Complex natural product scaffolds often present significant challenges. These molecules typically possess intricate architectures with multiple stereocenters and fused ring systems, making their total synthesis low-yielding and economically unviable [17]. For instance, natural products often have more rings and chiral centers, higher molecular weights, and complex oxygen-containing functional groups compared to synthetic compounds [17].

3. How can I quickly assess if my newly designed compound is synthetically accessible? You can use computational synthesizability scores for an initial rapid assessment. The table below compares four key metrics used to evaluate synthetic accessibility:

Table 1: Comparison of Computational Synthesizability Scores

| Score Name | Full Name | Score Range | Interpretation (Higher Score =) | Basis of Calculation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RScore [16] | Retro-Score | 0 - 1 | More synthesizable | Full retrosynthetic analysis via Spaya API |

| RA Score [16] | Retrosynthetic Accessibility Score | 0 - 1 | More synthesizable | Predictor of AiZynthFinder output |

| SC Score [16] | Synthetic Complexity Score | 1 - 5 | Less synthesizable (lower is better) | Neural network trained on reaction corpus |

| SA Score [16] | Synthetic Accessibility Score | 1 - 10 | Less complex/more feasible (lower is better) | Heuristic based on molecular complexity & fragments |

4. My compound has a poor synthesizability score. What are my options? You have several strategic options:

- Lead Optimization: Systematically modify the lead structure to simplify it while retaining anticancer activity. This can involve functional group manipulation, alteration of ring systems, and bio-isosteric replacements [17].

- Utilize Innovative Synthetic Methodologies: Explore modern reactions like C-H activation, multicomponent reactions, or photocatalysis, which can provide more efficient routes to complex molecules [15] [18].

- Investigate Retrosynthetic Pathways: Use AI-based retrosynthetic tools (e.g., Spaya, IBM RXN, ASKCOS) to identify viable synthetic routes and potential starting materials from commercial catalogs [19] [16].

5. Are there specific steps I can take during the molecular design phase to improve synthetic accessibility? Yes, integrating synthetic constraints early in the design process is key. When using AI-based molecular generators, you can apply the RScore or RSPred as a constraint during the generation itself. This guides the algorithm to explore chemical spaces where molecules are more synthesizable, leading to proposed structures that are both bioactive and synthetically tractable [16].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Complex Natural Product Lead

Scenario: Your team has isolated a novel natural product with potent in vitro anticancer activity. However, its complex structure makes total synthesis impractical, and the natural source does not provide enough material for further development.

Solution: Implement a Pharmacophore-Oriented Optimization Strategy

- Step 1: Identify the Pharmacophore. Determine the essential structural features (pharmacophore) responsible for the anticancer activity. Use techniques like SAR studies, molecular docking, and co-crystallization if the target is known [17] [6].

- Step 2: Design Simplified Analogues. Create synthetic analogues that retain the core pharmacophore but feature synthetically simplified scaffolds. Techniques like "scaffold hopping" can be useful here [17].

- Step 3: Employ Efficient Synthetic Routes. Utilize efficient synthetic methodologies, such as cyclization reactions or cross-coupling reactions, to construct the simplified core structure [15].

- Step 4: Validate Bioactivity. Test the synthesized analogues in your biological assays to confirm retained or improved anticancer activity.

Problem: AI-Designed Compound with No Viable Synthesis Route

Scenario: A generative AI model has proposed a novel compound with excellent predicted binding affinity for an oncology target. However, a preliminary retrosynthetic analysis using software like Spaya or IBM RXN fails to find a plausible route, or the route is too long and complex.

Solution: Integrate Retrosynthetic Analysis into the Design Loop

- Step 1: Score and Prioritize. Calculate the RScore for all AI-generated hits to prioritize compounds with high synthesizability potential [16].

- Step 2: Analyze the Retrosynthetic Pathway. For a top candidate with a medium-to-low RScore, run a detailed retrosynthetic analysis. Identify the specific step(s) causing complexity (e.g., a stereospecific transformation, a hard-to-form ring system) [19] [16].

- Step 3: Design a Replaceable Substructure. Based on the analysis, pinpoint the problematic substructure. Use medicinal chemistry knowledge to design a bioisostere or simplified fragment that replaces it [17].

- Step 4: Re-run the Generator with Constraints. Feed the synthesizability constraint (e.g., a minimum RSPred score) back into the AI generator and re-run the experiment to get new, more tractable molecule proposals [16].

Scenario: The synthesis of your lead anticancer compound involves 12 linear steps with an overall yield of less than 0.5%, making it impossible to produce the quantities needed for advanced testing.

Solution: Apply Strategies to Improve Synthetic Efficiency

- Step 1: Explore Convergent Synthesis. Redesign the synthetic route from a linear to a convergent strategy, where key fragments are synthesized in parallel and coupled late in the sequence. This dramatically improves overall yield [15].

- Step 2: Incorporate Catalytic Reactions. Replace stoichiometric reactions with more efficient catalytic ones. For example, use transition metal-catalyzed C-H activation or cross-coupling reactions to reduce steps and functional group manipulations [15] [18].

- Step 3: Utilize Multicomponent Reactions (MCRs). Where possible, implement MCRs, which assemble three or more reactants into a complex product in a single step, offering high atom economy and bond-forming efficiency [15].

- Step 4: Implement Process Optimization. For the final route, optimize reaction conditions (catalyst loading, solvent, temperature) to maximize yield and minimize purification for each step.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Synthetic Optimization

| Reagent/Category | Function in Optimization | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Transition Metal Catalysts (Pd, Rh) | Enable key bond-forming reactions (e.g., C-C, C-N) that are not possible with traditional chemistry. Essential for convergent synthesis and C-H activation [15]. | Palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling to join two complex fragments. |

| Chiral Catalysts/Ligands | Control stereochemistry in asymmetric synthesis, which is critical for building chiral centers found in many natural product-derived drugs [17]. | Synthesis of a specific enantiomer of a chiral anticancer lead to avoid inactive or toxic isomers. |

| Photocatalysts (e.g., Ru, Ir complexes) | Facilitate reactions driven by light, accessing unique reactive intermediates and enabling novel disconnections under mild conditions [15] [18]. | Creating complex cyclic structures via energy transfer mechanisms. |

| Commercial Building Blocks | Pre-synthesized, complex starting materials available from chemical suppliers (e.g., Spaya's catalog of 60M compounds) can shortcut several synthetic steps [16]. | Using a commercially available chiral synthon instead of a 5-step synthesis to make it. |

Computational Tools and Machine Learning Approaches for Synthetic Accessibility Assessment

Synthetic accessibility (SA) scoring systems are computational tools that estimate how easily a given molecule can be synthesized in a laboratory. These scores are crucial in computer-aided drug design, particularly in virtual screening and generative molecular design, where they help prioritize compounds that are not only biologically active but also practically manufacturable. Without such tools, researchers risk investing resources in molecules that may be theoretically promising but synthetically intractable [20] [1].

These scoring methods generally fall into two categories: structure-based approaches that analyze molecular fragments and complexity, and reaction-based approaches that incorporate knowledge from chemical reactions and synthesis pathways [20]. In the context of anticancer compound research, accurately predicting synthetic accessibility is especially valuable as it accelerates the transition from in silico designs to synthetically feasible lead compounds available for biological testing.

Comparative Analysis of Scoring Systems

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of four major synthetic accessibility scoring systems.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Synthetic Accessibility Scores

| Score | Underlying Principle | Molecular Representation | Score Range | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAscore | Fragment contribution statistics from PubChem combined with complexity penalties [20] [21] | Pipeline Pilot ECFP4 / RDKit Morgan FP (radius 2) [20] | 1 to 10 [20] | 1 = Easy to synthesize; 10 = Hard to synthesize [20] |

| SYBA | Bernoulli naïve Bayes classifier trained on easy-to-synthesize (ZINC15) and hard-to-synthesize (Nonpher-generated) molecules [20] [21] | RDKit Morgan FP (radius 2) [20] | Continuous (log-odds) [21] | Higher score = Easier to synthesize [21] |

| SCScore | Neural network trained on reaction databases (Reaxys) under the premise that products are more complex than reactants [20] [21] | RDKit Morgan FP (radius 2) [20] | 1 to 5 [20] | 1 = Simple molecule; 5 = Complex molecule [20] |

| RAscore | Machine learning classifier (Neural Network or GBM) trained on outcomes of the AiZynthFinder retrosynthesis tool [20] [22] | RDKit Morgan FP (radius 2) [20] | 0 to 1 [22] | Probability that a synthesis route can be found by the CASP tool [22] |

Table 2: Performance and Implementation Details

| Score | Training Data | Key Advantages | Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| SAscore | ~1 million molecules from PubChem [20] [21] | Fast calculation, easily interpretable scale [20] | Publicly available in RDKit [20] |

| SYBA | ES: ZINC15; HS: Nonpher-generated molecules [20] [21] | Explicitly trained on both easy and hard-to-synthesize compounds [21] | Conda package or GitHub [20] |

| SCScore | 12 million reactions from Reaxys [20] | Correlates with number of synthetic steps [20] | GitHub repository [20] |

| RAscore | 200,000+ molecules from ChEMBL labeled by AiZynthFinder [20] [22] | Directly mimics a specific CASP tool; extremely fast (~4500x faster than AiZynthFinder) [22] | GitHub repository [20] [22] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Which synthetic accessibility score is the most accurate for drug-like molecules, particularly in anticancer research?

No single score is universally superior. Each has distinct strengths depending on context [20]. For preliminary, high-throughput screening of large compound libraries (e.g., from virtual screening), SAscore and SYBA offer excellent speed. For a more synthesis-aware assessment, SCScore or RAscore are more appropriate [20]. For the highest accuracy in predicting the output of a specific synthesis planner, RAscore is trained directly on such data [22]. A consensus approach, where multiple scores are consulted, often provides the most robust assessment for critical decisions in anticancer compound prioritization.

Q2: Why does a molecule with a complex ring system receive a poor (high) SAscore?

SAscore incorporates a "complexity penalty" that specifically penalizes structural features known to challenge synthetic chemists [20] [1]. This penalty increases with:

- Ring Complexity: The presence of bridgehead and spiro atoms, which are common in fused or polycyclic systems often found in natural product-derived anticancer agents [20] [23].

- Macrocycle Complexity: Rings larger than 8 atoms, which often require specialized synthetic strategies [20] [23].

- Stereo Complexity: A high number of stereocenters, which complicates synthesis and purification [20] [23]. These features directly contribute to the final score, making complex molecules rank as harder to synthesize.

Q3: How can I use SYBA to understand which part of my candidate anticancer compound is making it hard to synthesize?

SYBA is uniquely suited for this task because it is a fragment-based method. Its final score is a simple sum of contributions from individual molecular fragments [21]. To identify problematic substructures:

- Compute the SYBA score for your molecule.

- Access the individual fragment contributions from the software's output.

- Fragments with large negative contributions are those that are statistically more common in hard-to-synthesize molecules and are therefore the primary culprits increasing the synthetic complexity [21]. This provides an interpretable roadmap for medicinal chemists to suggest simplifications or fragment replacements.

Q4: My RAscore indicates my molecule is synthesizable, but our chemists disagree. What could be the reason?

This discrepancy often arises from the inherent limitations of the training data. RAscore is trained to predict the outcome of a specific CASP tool (AiZynthFinder), which itself has limitations [22]. Key reasons include:

- Building Block Availability: AiZynthFinder (and thus RAscore) relies on a predefined database of commercially available building blocks. Your chemist may be considering internal inventory or cost of bespoke intermediates not in this database [22].

- Reaction Knowledge: The tool's knowledge is restricted to reaction rules extracted from its training data (e.g., USPTO patents). It may lack rules for novel or specialized reactions your chemist is considering, or it may propose routes with regio- or stereoselectivity issues that are not penalized in the score [22]. Therefore, treat a positive RAscore as a promising indication, not a guarantee, and always combine it with expert judgment.

Troubleshooting Common Technical Issues

Handling Invalid Molecule Errors

Problem: The SA scoring function returns an error or a null value when processing a SMILES string.

Solution:

- Validate Input SMILES: Ensure the SMILES string represents a valid, sensible molecule. Check for errors like hypervalent atoms, incomplete rings, or improper protonation of aromatic atoms [24].

- Pre-process Molecules: For multi-fragment molecules (e.g., salts), it is often necessary to split them into individual components and score the main organic fragment. Standardize tautomers and remove explicit hydrogens to ensure consistency [24].

- Check for Unsupported Elements: Confirm that the scoring function can handle all atoms and bond types present in your molecule. Some tools may not support less common elements or certain coordination bonds.

Dealing with Scores Outside the Applicability Domain

Problem: A molecule receives a synthetic accessibility score that contradicts expert chemical intuition.

Solution:

- Understand the Applicability Domain: Every SA score is trained on a specific dataset (e.g., SAscore on PubChem, SYBA on ZINC/Nonpher). Molecules with fragments or scaffolds not well-represented in these training sets will produce unreliable predictions [24]. This is a common issue with very novel scaffolds designed by generative AI.

- Perform a Consensus Check: If one score is an extreme outlier, calculate several different SA scores. If most scores agree and one disagrees, the consensus is likely more reliable.

- Consult a CASP Tool: For critical molecules where scores are conflicting or untrustworthy, use a full computer-aided synthesis planning (CASP) tool like AiZynthFinder or ASKCOS. While computationally expensive, these provide a more rigorous assessment based on actual reaction pathways [20] [22].

Performance and Integration Issues

Problem: The computation of scores is too slow for high-throughput screening of large virtual libraries.

Solution:

- Leverage RAscore for Speed: RAscore is designed specifically for this scenario, computing ~4500 times faster than running the underlying AiZynthFinder tool [22]. It is ideal for pre-screening millions of compounds.

- Use Rule-Based Scores for Initial Pass: For initial filtering of extremely large libraries (e.g., billions of molecules), the fastest scores are the fragment- and rule-based ones like SAscore and SYBA [20].

- Consider Cloud APIs: Commercial tools like the SYNTHIA SAS API are built for high-throughput, offering to process up to 100,000 molecules per hour [24] [25].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Standard Protocol for Benchmarking SA Scores

Objective: To evaluate and validate the performance of different synthetic accessibility scores against a known set of easy- and hard-to-synthesize molecules.

Materials:

- Test Sets: Curated molecular datasets with reliable synthesizability labels. Common examples include:

- Software: RDKit (for SAscore), SYBA package, SCScore implementation, RAscore package.

Methodology:

- Data Preparation: Standardize all molecules in the test set (e.g., neutralization, tautomer standardization).

- Score Calculation:

- For each molecule in the test set, compute the SAscore, SYBA, SCScore, and RAscore using their respective tools and default parameters.

- Performance Evaluation:

- For scores with built-in thresholds (e.g., SYBA), apply them to classify molecules as Easy or Hard.

- For continuous scores (e.g., SAscore), determine the optimal classification threshold using a Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve.

- Calculate performance metrics: Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC-ROC) to compare the scores' ability to discriminate between easy- and hard-to-synthesize molecules [20] [21].

Workflow for SA-Guided Optimization of Anticancer Compounds

The following diagram illustrates a typical workflow for using synthetic accessibility scores to optimize a hit compound in anticancer research.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

Table 3: Key Software and Resources for Synthetic Accessibility Assessment

| Item Name | Type | Function/Brief Explanation | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Software | Open-source toolkit used to compute molecular descriptors and fingerprints; includes an implementation of SAscore [20]. | https://www.rdkit.org |

| AiZynthFinder | CASP Tool | Open-source retrosynthesis planning tool used to generate training data for RAscore and for rigorous route validation [20] [22]. | https://github.com/MolecularAI/AiZynthFinder |

| ZINC15 | Chemical Database | Public database of commercially available compounds, often used as a source of "easy-to-synthesize" molecules for training (e.g., in SYBA) [21]. | https://zinc15.docking.org |

| ChEMBL | Chemical Database | Manually curated database of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties, commonly used for benchmarking and training [20] [22]. | https://www.ebi.ac.uk/chembl |

| SYNTHIA SAS API | Commercial API | High-throughput service that provides synthetic accessibility scores based on a model trained on SYNTHIA's retrosynthetic engine [24] [25]. | https://www.synthiaonline.com |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ: Core Concepts and Setup

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between structure-based and ligand-based virtual screening? Structure-based virtual screening (SBVS) uses the 3D structure of a protein target to dock and score compounds from a library, prioritizing those with favorable binding interactions [26]. Ligand-based virtual screening (LBVS) uses known active compounds as a reference to find structurally or pharmacophorically similar molecules in a database, which is particularly useful when a protein structure is unavailable [26].

Q2: Why is integrating synthetic accessibility early in the AI-VS workflow so crucial for anticancer drug discovery? Many hits from virtual screening can be complex natural products or synthetically challenging compounds, which hampers their development into viable lead candidates for timely cancer therapy [13]. Early integration ensures that prioritized compounds are not only potent but also can be practically synthesized and optimized using modern synthetic methodologies, accelerating the entire discovery pipeline [15].

Q3: What are the common technical causes for the failure of an AI-VS campaign to identify any viable hits?

- Inadequate Protein Structure Preparation: Issues like incorrect protonation states of key residues in the binding pocket can prevent accurate docking.

- Poor Chemical Library Curation: Libraries containing molecules with undesirable chemical properties or poor drug-likeness can lead to useless results.

- Insufficient Sampling: Overly restrictive docking search parameters can miss the correct binding pose for valid hit compounds.

- Scoring Function Limitations: The scoring function may fail to accurately predict the binding affinity for a novel chemotype, causing true binders to be ranked poorly [27] [26].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: High False Positive Rate in Initial Screening A significant number of top-ranked compounds from virtual screening show no activity in subsequent biological assays.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Over-reliance on a single scoring function. | Re-score the top hits and decoys using 2-3 different scoring functions. Check for consensus. | Implement a consensus scoring strategy. Use a more advanced, physics-based method like RosettaGenFF-VS for final ranking [27]. |

| Ligand bias in the screening library. | Analyze the physicochemical properties (e.g., molecular weight, logP) of the top hits for unrealistic profiles. | Apply stricter drug-like filters (e.g., Lipinski's Rule of Five) during library preparation. Use a diverse library to avoid a narrow chemical space [28]. |

| Inadequate handling of receptor flexibility. | Visually inspect if top hits are clashing with side-chains in the rigid protein structure. | Use a docking protocol that allows for side-chain and limited backbone flexibility, which is critical for certain targets [27]. |

Problem: Successfully Identified Hit is Synthetically Inaccessible A confirmed active compound is deemed too difficult or expensive to synthesize for analog development and lead optimization.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Synthetic complexity not evaluated during screening. | Calculate synthetic accessibility scores (e.g., SAScore) retrospectively for the hit list. | Integrate a synthetic accessibility score filter directly into the AI-VS workflow to triage compounds early [15]. |

| Presence of complex or unstable structural motifs. | Perform a retrosynthetic analysis of the hit compound using software or expert consultation. | Employ a bespoke chemical library enriched with synthetically tractable scaffolds. Use the hit as a model for designing simpler analogs with medicinal chemistry [13] [15]. |

Quantitative Performance Benchmarks

Table 1: Performance of the RosettaVS method on standard benchmarks. This data demonstrates the state-of-the-art capability of the method in accurately identifying true binders [27].

| Benchmark (CASF-2016) | Metric | RosettaGenFF-VS Performance | Next Best Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Docking Power | Success Rate (Top Ranked Pose) | Leading Performance | Lower |

| Screening Power | Enrichment Factor at 1% (EF1%) | 16.72 | 11.9 |

| Screening Power | Success Rate (Find best binder in top 1%) | Superior Performance | Lower |

Table 2: Experimental validation results from two independent AI-VS campaigns, showcasing high hit rates. The hit rates and binding affinities confirm the practical effectiveness of the described AI-VS platform [27] [28].

| Target Protein | Library Size Screened | Number of Experimental Hits | Hit Rate | Reported Binding Affinity (IC50/Kd) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KLHDC2 (Ubiquitin Ligase) | Multi-billion compounds | 7 | 14% | Single-digit µM [27] |

| NaV1.7 (Sodium Channel) | Multi-billion compounds | 4 | 44% | Single-digit µM [27] |

| GluN1/GluN3A (NMDA Receptor) | 18 million compounds | 2 | N/A | <10 µM (Potent candidate: 5.31 µM) [28] |

Detailed Methodologies for Key Experiments

Protocol 1: AI-Accelerated Multi-Stage Virtual Screening Workflow This protocol describes a hybrid approach that combines speed and accuracy for screening ultra-large libraries, completed in less than seven days for a multi-billion compound library [27] [28].

- Library Preparation: Standardize and filter a commercial or in-house compound library. Apply basic filters for drug-likeness and pan-assay interference compounds (PAINS).

- AI-Powered Prescreening (VSX Mode):

- Use a fast, initial docking algorithm (e.g., RosettaVS Virtual Screening Express) to rapidly screen the entire library.

- Simultaneously, employ an active learning framework where a target-specific neural network is trained on-the-fly to predict docking scores. This model triages and selects the most promising compounds for subsequent, more expensive docking calculations.

- High-Precision Docking (VSH Mode): Subject the top candidates from the previous stage (e.g., 1-5% of the library) to a more computationally intensive docking protocol. This protocol, such as RosettaVS Virtual Screening High-Precision, incorporates full receptor flexibility (side-chains and limited backbone) for more accurate pose and affinity prediction [27].

- Consensus Ranking & Synthetic Accessibility Filtering: Rank the finalists using a consensus of scores. Critically, at this stage, apply a synthetic accessibility score filter to prioritize compounds that are not only strong binders but also amenable to practical synthesis and future analog development [15].

- Experimental Validation: Select the top-ranked and synthetically accessible compounds for purchase or synthesis and validate their activity and binding through biochemical and biophysical assays.

Protocol 2: Validating a Predicted Binding Pose with X-ray Crystallography This is the gold-standard method for confirming the accuracy of the docking pose prediction from the virtual screen [27].

- Protein and Ligand Complex Formation: Co-crystallize the target protein with the validated hit compound. This involves incubating the purified protein with a high concentration of the ligand to facilitate binding.

- Crystallization: Grow a high-quality crystal of the protein-ligand complex using standard techniques like vapor diffusion.

- X-ray Diffraction Data Collection: Flash-free the crystal and expose it to a high-energy X-ray beam at a synchrotron source. Collect the resulting diffraction patterns.

- Structure Determination and Refinement: Use molecular replacement to solve the phase problem and calculate an electron density map. Iteratively refine the atomic model of the protein with the ligand into the electron density.

- Model Validation and Analysis: Examine the electron density around the binding pocket. A clear, well-defined density that matches the predicted pose of the docked ligand provides unambiguous validation of the virtual screening method.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key research reagents and computational tools for AI-enhanced virtual screening in anticancer drug discovery.

| Item Name | Function/Application | Relevant Context in AI-VS |

|---|---|---|

| RosettaVS Software Suite | An open-source, physics-based virtual screening platform for predicting docking poses and binding affinities. | The core docking engine; allows for receptor flexibility and has demonstrated state-of-the-art performance in identifying hits for difficult targets [27]. |

| Ultra-Large Chemical Libraries | Commercially or publicly available databases containing billions of purchasable or synthetically accessible compounds. | Provides the chemical space for discovery; enables the identification of novel scaffolds for anticancer targets [27]. |

| Synthetic Accessibility (SA) Score Calculator | A computational tool that estimates the ease of synthesis for a given organic molecule. | Integrated early in the workflow to prioritize hit compounds that are practical for medicinal chemistry optimization, enhancing project throughput [15]. |

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) Models | A class of AI models that operate on graph-structured data, ideal for representing molecules. | Used to enhance docking accuracy and for active learning during prescreening to efficiently triage compounds in ultra-large libraries [28]. |

| Structured Anticancer Compound Databases | Curated databases of known anticancer agents (e.g., natural products like Paclitaxel, synthetic analogs) [13]. | Provides reference active compounds for ligand-based screening and validates the biological relevance of the screening target and identified hits. |

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

AI-VS Workflow with SA Filter

Enhancing SA in Anticancer Research

Computer-Assisted Synthesis Planning (CASP) with Tools like AiZynthFinder

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Installation and Setup

Q: What are the prerequisites for installing AiZynthFinder?

A: AiZynthFinder requires Linux, Windows, or macOS with Python 3.9 to 3.11 installed, typically managed via Anaconda or Miniconda. The tool is installed via pip with the command python -m pip install aizynthfinder[all] for the full-featured version [29].

Q: I encounter a ValueError when initializing AiZynthApp in a Jupyter notebook. How can I resolve this?

A: This error often originates from an incorrect configuration file path or content [30]. The steps to resolve it are:

- Verify Config Path: Ensure the path to your

config.ymlfile is correct and accessible. - Check Policy Files: The configuration file must correctly point to your expansion policy model (a

.onnxor.hdf5file) and its corresponding template library (a.csv.gzor.hdf5file) [31]. - Validate Stock File: Confirm the stock file (e.g., in HDF5 format) is specified and formatted correctly, containing pre-computed InChi keys of purchasable building blocks [31].

- Use Public Data: You can download pre-trained models and stock files from the official figshare repository using the

download_public_datacommand to ensure you have a working baseline configuration [29].

Configuration and Execution

Q: What is the basic structure of a configuration file (config.yml)?

A: A minimal configuration file requires expansion and stock sections [31].

Q: How can I adjust the search algorithm to find solutions faster or more exhaustively?

A: You can tune parameters in the search section of your config.yml file [31]. The table below summarizes key parameters and their effects.

Table 1: Key Search Algorithm Parameters in AiZynthFinder

| Parameter | Default Value | Description | Use-Case Guidance |

|---|---|---|---|

algorithm |

mcts |

The core search algorithm. | Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) is the default and well-tested algorithm [32]. |

iteration_limit |

100 |

Maximum number of tree search iterations. | Increase for a more exhaustive search on complex targets. |

time_limit |

120 |

Maximum search time in seconds. | Increase to allow more time for difficult problems; decrease for high-throughput screening. |

max_transforms |

6 |

Maximum depth (steps) of the retrosynthetic tree. | Increase for longer synthetic routes; decrease to find shorter, more direct routes. |

C (in algorithm_config) |

1.4 |

Balances exploration vs. exploitation in MCTS. | A higher value encourages exploration of less-tried paths [31]. |

prune_cycles_in_search |

True |

Prevents the search from recreating previously seen molecules. | Set to True to improve efficiency and avoid circular routes [31]. |

Q: What are expansion and filter policies, and how are they configured? A:

- Expansion Policy: Guides the tree search by suggesting possible reaction templates to apply to a target molecule. It is configured by specifying a model file and a template file [32] [31]. Key parameters include

cutoff_number(maximum templates returned, default 50) andcutoff_cumulative(cumulative probability threshold, default 0.995) [31]. - Filter Policy (Optional): A trained neural network that removes unrealistic reactions proposed by the expansion policy, improving route quality. It requires a single model file in the

filtersection of the config [32].

Analysis and Output

Q: How can I assess the synthetic accessibility of thousands of virtual compounds from a virtual screen? A: Running AiZynthFinder on millions of compounds is computationally prohibitive. For large-scale pre-screening, use a machine learning-based Retrosynthetic Accessibility score (RAscore). RAscore is a binary classifier trained on AiZynthFinder outcomes that estimates synthetic feasibility ~4500 times faster than full retrosynthetic analysis [33]. This allows you to rapidly filter virtual compound libraries for synthesizability before committing to a full CASP analysis [33].

Q: What are the latest advancements to make AiZynthFinder faster for high-throughput workflows? A: Recent research focuses on accelerating the single-step retrosynthesis models within the CASP framework. Speculative Beam Search (SBS) combined with a drafting strategy like Medusa can significantly reduce the latency of transformer-based expansion policies. This method has been shown to allow AiZynthFinder to solve 26% to 86% more molecules under the same time constraints of a few seconds, making it more suitable for high-throughput synthesizability screening [34].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Components for a CASP Workflow with AiZynthFinder

| Item | Function | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Expansion Policy Model | Neural network that recommends retrosynthetic transformations. | A trained Keras model (e.g., uspto_expansion.onnx) based on a reaction database like USPTO [31]. |

| Reaction Template Library | Database of known chemical transformations applied by the expansion policy. | A compressed file (e.g., uspto_templates.csv.gz) matched to the expansion model [31]. |

| Stock | Collection of available starting materials; the "leaves" of the retrosynthetic tree. | An HDF5 file containing InChi keys of purchasable compounds (e.g., from ZINC, Enamine, or internal databases) [31] [33]. |

| Filter Policy Model | (Optional) Neural network that filters out infeasible reactions post-expansion. | A trained model (e.g., uspto_filter.hdf5) that improves route quality by removing unrealistic suggestions [32]. |

| Retrosynthetic Accessibility (RAscore) Model | For large-scale synthesizability screening of virtual compound libraries. | A pre-trained XGBoost or Neural Network classifier that approximates AiZynthFinder's result much faster [33]. |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Workflow 1: Single-Target Retrosynthetic Analysis

This protocol is designed for finding synthetic routes for a specific target molecule, such as a predicted anticancer compound.

- Input Target: Define the target molecule using its SMILES string.

- Software Initialization: Initialize

AiZynthAppin a Python script or Jupyter notebook, providing the path to a validconfig.ymlfile [30]. - Tree Search Execution: Execute the tree search using the

appobject. The search will run until it meets the stopping criteria defined in the configuration (e.g., time limit, iteration limit, or finding the first solution) [31]. - Route Extraction and Analysis: After the search, extract the top routes. These routes can be scored, clustered, and visualized for further analysis [32].

Workflow 2: High-Throughput Synthesizability Screening for Virtual Anticancer Compounds

This protocol uses the RAscore to efficiently pre-filter large virtual compound libraries generated during de novo drug design.

- Virtual Library Generation: Obtain a library of candidate molecules from a generative model or database enumeration.

- RAscore Calculation: Process the entire library through the RAscore model to obtain a rapid synthesizability estimate for each compound [33].

- Filtering: Apply a threshold to the RAscore to retain only the top-ranking compounds deemed most likely to be synthesizable.

- In-Depth Analysis: Subject the filtered subset of compounds to a full retrosynthetic analysis using AiZynthFinder for detailed route planning.

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: AiZynthFinder Core Workflow

Diagram 2: High-Throughput Screening Workflow

Structure-Based Simplification Strategies for Complex Natural Product Leads

Natural products are an indispensable source of molecular and mechanistic diversity for anticancer drug discovery [17]. Historically, they have provided a significant proportion of all approved anticancer agents, with approximately 79.8% of anticancer drugs approved between 1981 and 2010 being derived from or inspired by natural products [17]. However, these complex molecules often serve as initial leads rather than final drugs due to challenges including synthetic inaccessibility, unfavorable pharmacokinetic profiles, and suboptimal drug-likeness [17] [35]. Structural simplification has emerged as a powerful strategy to overcome these limitations by systematically truncating unnecessary substructures from complex natural templates while retaining or enhancing their core biological activity [35] [36]. This approach aligns with the broader thesis of enhancing synthetic accessibility in anticancer compound research, enabling more efficient exploration of structure-activity relationships (SAR) and accelerating the development of clinically viable therapeutics.

Core Principles of Structural Simplification