Strategies for Effective PCR Inhibitor Removal from Clinical Samples: Enhancing qPCR Reliability in Diagnostics and Research

Accurate quantitative PCR (qPCR) is foundational to modern clinical diagnostics and biomedical research, yet its reliability is frequently compromised by inhibitors present in complex clinical samples such as blood, tissues,...

Strategies for Effective PCR Inhibitor Removal from Clinical Samples: Enhancing qPCR Reliability in Diagnostics and Research

Abstract

Accurate quantitative PCR (qPCR) is foundational to modern clinical diagnostics and biomedical research, yet its reliability is frequently compromised by inhibitors present in complex clinical samples such as blood, tissues, and other biological matrices. This comprehensive article synthesizes current methodologies and best practices for identifying, removing, and mitigating the effects of these inhibitors. It explores foundational concepts of inhibition mechanisms, details practical sample preparation and direct PCR protocols, provides advanced troubleshooting and optimization strategies, and outlines rigorous validation frameworks. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this resource aims to empower readers with the knowledge to achieve robust, reproducible, and clinically actionable qPCR results, thereby enhancing the integrity of molecular data across applications.

Understanding PCR Inhibition: Sources, Mechanisms, and Impact on Clinical qPCR Accuracy

In quantitative PCR (qPCR), the reliable detection and quantification of nucleic acids can be severely compromised by the presence of specific inhibitors found in clinical samples. These substances interfere with the enzymatic amplification process, leading to delayed quantification cycle (Cq) values, reduced amplification efficiency, or even complete reaction failure [1] [2]. Understanding the origin and mechanism of these inhibitors is the first step toward developing effective countermeasures.

The table below summarizes the four common inhibitors addressed in this guide, their sample sources, and primary mechanisms of action.

Table 1: Common qPCR Inhibitors in Clinical Samples

| Inhibitor | Common Sample Sources | Primary Mechanism of Inhibition |

|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin | Whole blood, plasma, serum | Interferes with DNA polymerase activity [2] [3]. |

| Heparin | Blood and tissues (as an anticoagulant) | Chelates magnesium ions (Mg²⁺), a crucial co-factor for DNA polymerases [1] [2]. |

| Immunoglobulins (e.g., IgG) | Blood, serum, plasma | Binds to single-stranded DNA, preventing primer annealing and polymerase activity [4] [3]. |

| Lactoferrin | Blood, milk, mucosal secretions | Suppresses DNA polymerase activity; a known inhibitor in whole blood [4] [2]. |

Troubleshooting FAQs

FAQ 1: How can I detect the presence of PCR inhibitors in my qPCR assay?

Inhibition can be detected through several observable deviations in your qPCR data [1] [5]:

- Delayed Cq Values: A general shift to later Cq values across all samples, including positive controls, suggests systemic inhibition. Using an Internal PCR Control (IPC) is highly recommended; if the IPC Cq is also delayed, inhibition is likely [1].

- Poor Amplification Efficiency: Calculate your amplification efficiency from a standard curve. Efficiency outside the ideal range of 90–110% (with a slope between -3.1 and -3.6) can indicate inhibition affecting polymerase function or primer binding [1] [6].

- Abnormal Amplification Curves: Flattened curves, a lack of clear exponential phases, or inconsistent growth curves can signal interference from inhibitors [1] [5].

- Irreproducible Data: High variability between technical replicates or inconsistent results between samples can be a sign of inhibitors [5].

FAQ 2: My sample is a blood stain. Which inhibitors should I be most concerned about, and what is the best removal method?

Blood is a complex sample containing multiple potent inhibitors, primarily hemoglobin, immunoglobulin G (IgG), and lactoferrin [2]. Heparin may also be present if it was used as an anticoagulant [2]. A comparative study evaluated four methods for removing a range of inhibitors, including hematin (a component of hemoglobin). The results demonstrated that silica-based column purification methods, such as the PowerClean DNA Clean-Up kit and the DNA IQ System, were highly effective at removing these inhibitors and generating more complete genetic profiles [7] [8]. These methods are superior to simple Chelex-100 extraction or Phenol-Chloroform for this purpose [8].

FAQ 3: I am using heparinized blood samples. My qPCR fails consistently. What specific steps can I take?

Heparin is a potent inhibitor that is difficult to remove. The following strategies are recommended:

- Optimize Sample Purification: Use a heparin-resistant DNA extraction kit or perform an additional post-extraction clean-up step, such as ethanol precipitation [1].

- Adjust Reaction Chemistry: Increase the concentration of MgCl₂ in your qPCR master mix. This can help counteract heparin's Mg²⁺ chelating effect [1].

- Use Additives: Add Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) to the reaction. BSA can bind to various inhibitors, including heparin, and mitigate their effects [1] [3].

- Select a Robust Master Mix: Use a qPCR master mix specifically formulated for high inhibitor tolerance [1].

FAQ 4: Can I simply dilute my DNA extract to overcome inhibition?

Yes, dilution is a simple and often effective strategy. By diluting the DNA template, you also dilute the concentration of the inhibitor to a level that may no longer affect the reaction [1] [3]. However, this approach has a significant drawback: it also dilutes the target DNA. This can be problematic for samples with low initial target concentration, potentially pushing the Cq beyond the limit of detection. Therefore, dilution is best suited for samples with a high DNA concentration [3].

Experimental Protocols for Inhibitor Removal and Validation

Protocol: Removal of Inhibitors via Silica-Column Based Purification

This protocol is adapted from methods validated for effective inhibitor removal in forensic and clinical samples [7] [8].

Principle: Nucleic acids bind to a silica membrane in the presence of a chaotropic salt, while impurities and inhibitors are washed away. The pure nucleic acids are then eluted in a low-salt buffer.

Materials:

- PowerClean DNA Clean-Up Kit (or similar silica-column based kit)

- Clinical sample (e.g., blood, tissue lysate)

- Microcentrifuges

- Nuclease-free water

- 70% and 100% Ethanol

Procedure:

- Lysate Preparation: Process the clinical sample according to the manufacturer's instructions to create a crude lysate.

- Binding: Add the lysate to the silica column and centrifuge. Discard the flow-through.

- Washing: Add the provided wash buffer (typically containing ethanol) to the column and centrifuge. Repeat this step as directed. Critical Note: Ensure all ethanol is removed by centrifugation, as it is a PCR inhibitor [3].

- Elution: Apply nuclease-free water or a low-salt elution buffer to the center of the membrane, incubate for 1-2 minutes, and centrifuge to collect the purified DNA.

Validation: Compare the Cq values of an Internal PCR Control (IPC) or a spiked exogenous DNA target between the purified and unpurified samples. A significant decrease in Cq after purification indicates successful inhibitor removal [1].

Protocol: Direct qPCR from Whole Blood Using Heat Lysis

This protocol offers a cost-effective, direct PCR method that avoids DNA extraction, as demonstrated in recent research [4].

Principle: Osmotic pressure and heat lyse blood cells, and a subsequent dilution step reduces the concentration of intracellular inhibitors to a level tolerable for amplification.

Materials:

- EDTA-treated whole blood

- Distilled water

- Thermal block or water bath (95°C)

- Microcentrifuge

- qPCR reagents (SYBR Green master mix, primers)

Procedure:

- Lysate Preparation: Mix 400 µL of whole blood with 100 µL of distilled water (final concentration ~80%) [4].

- Heat Treatment: Incubate the mixture at 95°C for 20 minutes. Vortex the sample 2-3 times during incubation [4].

- Clarification: Centrifuge the lysate at 14,000 rpm for 5 minutes [4].

- qPCR Setup: Use the supernatant directly as a template in qPCR reactions. The study successfully used 2.5 µL of a 1:10 or 1:5 dilution of the lysate in a 10 µL reaction [4].

Validation: The method should be validated against a standard DNA extraction protocol. While PCR efficiency for some targets (e.g., ACTB, PIK3CA) may be slightly lower (~14-20% difference reported), successful amplification with a single melting peak for each primer set confirms the method's utility for applications like SNP genotyping [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Kits

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Overcoming qPCR Inhibition

| Reagent / Kit | Function / Application | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|

| PowerClean DNA Clean-Up Kit [7] [8] | DNA purification designed to remove PCR inhibitors from complex samples. | Effective removal of humic acid, hematin, bile salts, collagen, and indigo. |

| DNA IQ System [7] [8] | DNA extraction and purification using magnetic silica beads. | Effectively removes a wide range of inhibitors; suitable for automation. |

| GoTaq Endure qPCR Master Mix [1] | Ready-to-use master mix for quantitative PCR. | Formulated for high tolerance to inhibitors in blood, plant, and soil samples. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) [1] [3] | PCR additive. | Binds to inhibitors like phenolics, humic acid, and heparin, neutralizing their effects. |

| Inhibitor-Tolerant DNA Polymerases [2] [3] | Enzyme blends or engineered polymerases for direct PCR. | Higher resistance to inhibitors in blood (e.g., hemoglobin, IgG) compared to standard Taq. |

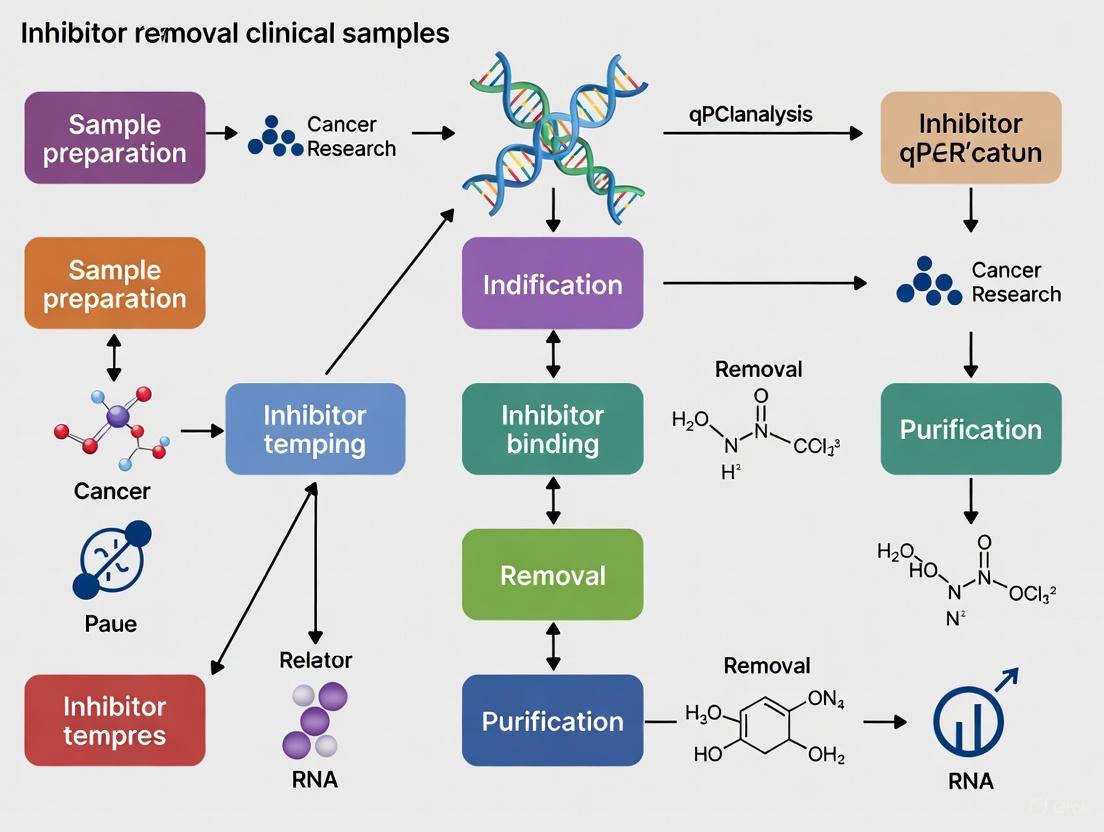

Workflow and Mechanism Diagrams

Diagram 1: Inhibitor management workflow for reliable qPCR.

Diagram 2: Molecular mechanisms of common qPCR inhibitors.

For scientists working with clinical samples, the reliability of qPCR results is paramount. A significant challenge in this context is the presence of PCR inhibitors, which are substances that originate from biological samples, environmental contaminants, or laboratory reagents and interfere with the amplification process [1]. These compounds can lead to inaccurate quantification, poor amplification efficiency, or complete reaction failure, ultimately jeopardizing data integrity and subsequent conclusions in drug development and clinical diagnostics [1]. The inhibitors exert their effects through two primary mechanisms: suppression of DNA polymerase activity and interference with fluorescent signal detection [2] [1]. Understanding these mechanisms is the first step toward developing effective countermeasures for obtaining reliable qPCR data from complex clinical matrices.

Mechanisms of PCR Inhibition

PCR inhibition occurs when substances present in a reaction interfere with the biochemical processes essential for DNA amplification and detection. The mechanisms can be broadly categorized as follows.

Suppression of DNA Polymerase Activity

Inhibitors can interfere with the DNA polymerase enzyme itself, reducing its activity or preventing it from functioning altogether. This suppression can occur through several distinct pathways:

- Enzyme Interaction: Some inhibitors, such as melanin, collagen, and humic acids, form reversible complexes with the DNA polymerase, effectively preventing the enzyme from interacting with its DNA template [2] [9].

- Cofactor Chelation: The DNA polymerase requires magnesium ions (Mg²⁺) as an essential cofactor. Inhibitors like EDTA or various metal ions compete for or chelate Mg²⁺, reducing its availability in the reaction and crippling enzymatic activity [1] [9].

- Nucleic Acid Interaction: Substances such as polysaccharides, glycolipids, and humic substances can interact directly with the template DNA. They may coat the DNA, preventing primer annealing, or cause template degradation, making the target sequence inaccessible for amplification [2] [9].

Fluorescence Interference

Given that qPCR relies on fluorescence for detection and quantification, any substance that affects the fluorescent signal can be a potent inhibitor. This interference manifests as:

- Fluorescence Quenching: Compounds like humic acids and tannins can quench the fluorescence of the dyes or probes used in qPCR [2] [1]. This quenching can occur through collisional mechanisms, where the quencher molecule collides with the excited-state fluorophore, or static mechanisms, where a non-fluorescent complex is formed [2].

- Background Fluorescence: Some inhibitors may introduce excessive background fluorescence, which reduces the signal-to-noise ratio and makes it difficult to accurately determine the quantification cycle (Cq) [1].

Common Inhibitors in Clinical and Environmental Samples

The table below summarizes common PCR inhibitors found in various sample types relevant to clinical and biomedical research.

Table 1: Common PCR Inhibitors and Their Effects

| Inhibitor Source | Example Inhibitors | Primary Mechanism of Inhibition |

|---|---|---|

| Blood, Serum, Plasma | Hemoglobin, Lactoferrin, IgG, Heparin [2] [1] [9] | Polymerase inhibition, co-factor chelation [1] |

| Tissues | Heparin (from collection) [1] | Polymerase inhibition [1] |

| Feces | Bile Salts, Urea [10] | Polymerase inhibition, template degradation |

| Urine | Urea [10] | Polymerase inhibition [9] |

| Formalin-Fixed Tissue | Formalin [10] | Polymerase inhibition, nucleic acid cross-linking |

| Soil & Environment | Humic Acids, Fulvic Acids [2] | Polymerase inhibition, fluorescence quenching, template interaction [2] |

| Plants & Food | Polysaccharides, Polyphenols, Tannins [1] | Polymerase inhibition, fluorescence interference [1] |

| Lab Reagents | Phenol, SDS, Ethanol, Salts [1] [11] [9] | Template precipitation, primer binding disruption, co-factor chelation [1] |

The following diagram illustrates the two main pathways of PCR inhibition and their impact on the qPCR reaction.

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying and Overcoming Inhibition

This section provides a structured approach to diagnose and resolve inhibition issues in your qPCR experiments.

How to Identify PCR Inhibition

Recognizing the signs of inhibition is crucial for effective troubleshooting. Key indicators include [1] [12]:

- Delayed Cq Values: A systematic increase in the quantification cycle (Cq) across all samples, including controls, suggests the presence of an inhibitor. This can be confirmed using an Internal PCR Control (IPC); if the IPC Cq is also delayed, inhibition is likely.

- Poor Amplification Efficiency: The calculated efficiency of the qPCR reaction falls outside the acceptable range of 90–110% (standard curve slope between -3.1 and -3.6) [1].

- Abnormal Amplification Curves: Flattened, inconsistent, or non-exponential amplification curves can indicate interference with enzyme activity or fluorescence detection.

- Reduced Signal Intensity: A general decrease in fluorescence signal, potentially leading to a failure to cross the detection threshold.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My qPCR results show high Cq values. Is this due to low template concentration or inhibition? This is a common dilemma. To differentiate, employ an Internal Amplification Control (IAC) [12]. Spike a known amount of non-target control DNA into your sample. If the Cq value for the IAC is significantly delayed compared to a clean control reaction, inhibition is present. If only the target Cq is high, low template concentration is the more likely cause [1] [12].

Q2: My negative control is clean, but I get smeared bands or multiple products in my sample. Is this inhibition? While smearing can sometimes be related to inhibitors, it is more commonly a sign of non-specific amplification [11] [9]. Inhibition typically reduces or eliminates amplification rather than causing smearing. To improve specificity, consider increasing the annealing temperature, using a hot-start DNA polymerase, optimizing Mg²⁺ concentration, or redesigning your primers [11].

Q3: I am using a PCR purification kit, but my samples are still inhibited. What else can I do? Purification kits are effective but not infallible, especially with challenging samples. If inhibition persists, consider these steps:

- Dilute the Template: A 10-fold dilution of your DNA extract can reduce inhibitor concentration to a level that no longer interferes, though this also dilutes the target [1] [13].

- Use an Inhibitor-Tolerant Polymerase: Switch to a DNA polymerase blend specifically engineered for high resistance to inhibitors commonly found in blood, soil, and plant tissues [2] [11].

- Add PCR Enhancers: Include additives like Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) or T4 gene 32 protein (gp32) in your reaction mix. These proteins can bind to inhibitory compounds and neutralize them [13].

Q4: Are some PCR techniques less susceptible to inhibitors? Yes, digital PCR (dPCR) has been demonstrated to be more tolerant of inhibitors than qPCR [2]. This is because dPCR partitions a sample into thousands of nanoreactions, effectively diluting out inhibitors, and uses end-point measurement rather than relying on amplification kinetics, which are easily skewed by inhibitors in qPCR [2].

Experimental Protocol: Systematic Evaluation of Inhibition

This protocol provides a step-by-step method to confirm and quantify the level of inhibition in your nucleic acid extracts.

- Objective: To determine if a clinical sample extract contains substances that inhibit the qPCR reaction.

- Principle: A known quantity of a control template is added to the sample extract and amplified. Its Cq value is compared to the Cq value obtained when the same control is amplified in a clean background (e.g., water). A significant delay indicates inhibition [10] [12].

Materials:

- Test nucleic acid extracts from clinical samples.

- Control DNA template (e.g., plasmid, synthetic oligo) at a known concentration.

- qPCR master mix, primers, and probes specific to the control template.

- Real-time PCR instrument.

Procedure:

- Prepare a dilution series of your control template in nuclease-free water to create a standard curve.

- For each test sample extract, set up two reactions:

- Reaction A (Test for Inhibition): qPCR mix + test sample extract (which may contain inhibitors) + a known, moderate amount of control template.

- Reaction B (Baseline Control): qPCR mix + test sample extract + no additional control template (to check for cross-reactivity).

- Set up a reference reaction: qPCR mix + nuclease-free water + the same known amount of control template as in Reaction A.

- Run the qPCR protocol.

- Analysis: Compare the Cq value of the control template spiked into the sample extract (Reaction A) with the Cq value of the control template in water.

The workflow for this diagnostic experiment is outlined below.

Research Reagent Solutions

A selection of key reagents and methods to mitigate PCR inhibition is provided in the table below. The optimal strategy often involves a combination of these approaches.

Table 2: Key Reagents and Methods for Overcoming PCR Inhibition

| Solution Category | Specific Reagent/Method | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Inhibitor-Tolerant Enzymes | Specialty DNA Polymerase Blends (e.g., GoTaq Endure, Phusion Flash) [1] | Engineered for high resistance to inhibitors in blood, soil, and plant-derived nucleic acids. |

| Protein Additives | Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) [1] [13] | Binds to and neutralizes inhibitors such as polyphenols and humic acids; stabilizes the polymerase. |

| T4 Gene 32 Protein (gp32) [13] | A single-stranded DNA binding protein that effectively binds humic acids, improving detection and recovery of target nucleic acids. | |

| Purification Methods | Silica Column-Based Kits [2] | Efficiently purifies nucleic acids, removing many salts, proteins, and other contaminants. |

| Magnetic Bead-Based Kits [2] | Allows for automated, high-throughput purification and effective removal of PCR inhibitors. | |

| Ethanol Precipitation [11] | A traditional method to desalt and concentrate nucleic acid samples, removing some inhibitors. | |

| Physical/Dilution Methods | Template Dilution [1] [13] | Simple dilution of the nucleic acid extract to reduce inhibitor concentration below an effective threshold. |

| Direct PCR Methods [2] | Minimizes or omits DNA extraction to avoid DNA loss, relying on inhibitor-tolerant polymerases to handle background material. | |

| Alternative Techniques | Digital PCR (dPCR) [2] | Partitions the sample, diluting inhibitors, and uses end-point analysis for more accurate quantification in inhibited samples. |

In the context of clinical research and drug development, where the accuracy of qPCR data can directly impact diagnostic and therapeutic decisions, managing PCR inhibition is non-negotiable. A systematic approach—combining an understanding of inhibition mechanisms, diligent monitoring of amplification kinetics, and the strategic application of reagent solutions and optimized protocols—is essential. By implementing the troubleshooting guides and FAQs presented here, researchers can significantly enhance the reliability of their nucleic acid quantification, ensuring that results truly reflect the biological reality of the clinical samples under investigation.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the primary consequences of PCR inhibitors in clinical diagnostics? PCR inhibitors present in clinical samples can lead to false negatives, underestimation of target concentration, and reduced analytical sensitivity. They achieve this by suppressing or delaying the amplification reaction, which results in higher Cq (Quantification Cycle) values or complete amplification failure [14] [15] [4]. This can cause a missed diagnosis, inaccurate viral load monitoring, and an incorrect assessment of treatment efficacy.

2. Beyond complete failure, how can inhibitors lead to the underestimation of a target? Inhibitors often cause a partial suppression of the PCR reaction, not a complete shutdown. This manifests as a higher Cq value, suggesting a lower starting concentration of the target than is actually present [15] [16]. Even a slight shift in Cq can represent a significant underestimation of the true quantity because the relationship between Cq and concentration is exponential [15]. For example, a single nucleotide mutation in a probe-binding region was shown to cause an up to 2.3-fold underestimation of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater [17].

3. What are some common sources of PCR inhibitors in clinical samples? Common inhibitors include:

- Hemoglobin from whole blood [4]

- Immunoglobulin G (IgG) [4]

- Lactoferrin [4]

- Complex polysaccharides from tissues

- Urea and bile salts from urine

- Calcium alginate from certain swab types [14] These substances can inhibit DNA polymerases or interfere with the amplification process [14] [4].

4. How can I confirm that my qPCR results are being affected by inhibitors? The use of an internal control (e.g., amplification of a housekeeping gene) is a key strategy. If the internal control shows abnormal Cq values or failed amplification in a sample, it indicates the presence of PCR inhibitors or issues with nucleic acid quality [14]. Additionally, observing inconsistent replicate data or amplification curves that fail to reach a proper plateau can also suggest inhibition [18] [16].

5. What are the best practices for preventing false negatives and underestimation? Key practices include:

- Using an internal control to detect inhibition in each sample [14].

- Employing robust nucleic acid extraction methods designed to remove inhibitors.

- Incorporating PCR enhancers like Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) into the reaction mix to neutralize certain inhibitors [14].

- Diluting the sample template, which can dilute the inhibitor to a level where it no longer affects the reaction [4].

- Designing assays with high efficiency and validating them according to guidelines like MIQE to ensure accuracy and reliability [19] [20] [15].

Troubleshooting Guide: Resolving False Negatives and Reduced Sensitivity

Issue: No Amplification or Signal

| Possible Cause | Checks & Solutions | Underlying Principle |

|---|---|---|

| Complete PCR Inhibition | Run a positive control. If it amplifies, the issue is sample-specific. Add BSA (200-400 ng/µL) to the reaction [14]. | BSA binds to and neutralizes inhibitory compounds like phenolics and immunoglobulin G [14]. |

| Inefficient Cell Lysis / Low Template | Confirm nucleic acid concentration and quality (A260/A280 ratio). Re-extract using a validated protocol. | Inhibitors or improper technique during extraction can lead to insufficient yield or degraded nucleic acids [14]. |

| Reagent Degradation | Prepare fresh reagents and use new aliquots of enzymes/dNTPs. | Freeze-thaw cycles or improper storage can inactivate critical reaction components [16]. |

Issue: High Cq Values & Underestimation

| Possible Cause | Checks & Solutions | Underlying Principle |

|---|---|---|

| Partial PCR Inhibition | Dilute the template (e.g., 1:5, 1:10) and re-run the reaction [4]. Use an internal control to confirm. | Dilution reduces the concentration of inhibitors below a critical threshold while potentially retaining sufficient target for detection [4]. |

| Suboptimal PCR Efficiency | Calculate PCR efficiency via standard curve. It should be 90-110%. Redesign primers if efficiency is low [15]. | Cq values are highly dependent on PCR efficiency. A small drop in efficiency causes a large shift in Cq, leading to significant underestimation [15]. |

| Low-Quality Primers/Probe | Check primers for dimers and secondary structure. Ensure probes are intact and not degraded [20] [14]. | Degraded reagents reduce the effective concentration for the reaction, lowering sensitivity and increasing Cq. |

| Sequence Mismatches | If targeting highly variable regions (e.g., viruses), check for mutations in the primer/probe binding sites [17]. | Even a single nucleotide mismatch in the probe-binding region can reduce hybridization efficiency and cause significant signal drop and underestimation [17]. |

Issue: Non-Specific Amplification & False Positives

| Possible Cause | Checks & Solutions | Underlying Principle |

|---|---|---|

| Carryover Contamination | Use Uracil-DNA-Glycosylase (UNG) in the master mix. Physically separate pre- and post-PCR areas [14]. | UNG enzymatically degrades PCR products from previous runs (containing dUTP) before amplification starts, preventing re-amplification [14]. |

| Poor Primer Specificity | Increase the annealing temperature. Use "hot-start" polymerase. Perform in silico specificity checks (e.g., BLAST) [14]. | Hot-start polymerases remain inactive until a high temperature is reached, preventing non-specific amplification during reaction setup [14]. |

| Environmental Contamination | Use dedicated lab coats and gloves. Decontaminate surfaces with 10% bleach or UV light. Use nuclease-free plastics [14]. | Strict unidirectional workflow and decontamination prevent amplicons or foreign DNA from contaminating samples and reagents [14]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | PCR enhancer; mitigates inhibition by binding to contaminants like immunoglobulins and phenolic compounds [14]. |

| Uracil-DNA-Glycosylase (UNG) | Enzyme used to prevent false positives from amplicon carryover contamination; degrades uracil-containing DNA from previous PCRs [14]. |

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | A modified enzyme activated only at high temperatures; improves specificity by preventing non-specific priming during reaction setup [14]. |

| Nuclease-Free Water | A critical reagent free of nucleases that would otherwise degrade primers, probes, and templates [14]. |

| PCR Enhancer Kits | Commercial blends containing reagents like betaine, trehalose, or proprietary components that can help stabilize enzymes and improve amplification from difficult samples. |

Experimental Protocol: Assessing Inhibition via Sample Dilution

This protocol helps diagnose and overcome partial PCR inhibition, a common cause of underestimation.

Principle: Serially diluting a sample template can dilute PCR inhibitors to a level where they no longer significantly affect amplification efficiency. A consistent change in Cq across dilutions indicates proper reaction kinetics, while a non-linear response suggests inhibition [4].

Materials:

- Extracted nucleic acid sample

- Nuclease-free water [14]

- qPCR master mix (e.g., SYBR Green or probe-based)

- Primers and probe for the target and an internal control

- Real-time PCR instrument

Method:

- Prepare a 1:5 dilution of your extracted nucleic acid sample using nuclease-free water.

- From the 1:5 dilution, prepare a 1:25 dilution.

- Set up qPCR reactions using the undiluted, 1:5, and 1:25 sample templates. Include an internal control (e.g., a housekeeping gene) in each reaction.

- Run the qPCR under optimized cycling conditions.

- Analysis: Calculate the observed ∆Cq between the dilutions (e.g., Cqundiluted - Cq1:5). For a 1:5 dilution, the expected ∆Cq with 100% efficiency is -log₂(5) ≈ -2.32.

- If inhibition is absent: The observed ∆Cq will be close to the expected value.

- If inhibition is present: The undiluted sample will show a higher-than-expected Cq. The ∆Cq between the undiluted and 1:5 sample will be less than expected (e.g., -1.5), and the ∆Cq between the 1:5 and 1:25 dilutions will more closely match the theoretical value as the inhibitor is diluted out.

Inhibitor Impact and Solution Workflow

The diagram below illustrates how inhibitors affect the qPCR process and the corresponding solutions.

Fundamental Concepts: How Inhibitors Distort qPCR Results

What is the relationship between PCR inhibitors and amplification efficiency?

Answer: PCR efficiency is a measure of how effectively a target sequence is amplified during each cycle of the qPCR reaction. The theoretical maximum is 100%, which corresponds to a perfect doubling of amplicons every cycle [21] [22]. Inhibitors are substances present in the sample that interfere with the enzymatic reaction, leading to a reduction in this efficiency. Paradoxically, the calculation of efficiency can sometimes exceed 100% when inhibitors are present in a non-uniform manner across a dilution series. This occurs because inhibitors are more concentrated in less diluted samples, causing a flatter slope in the standard curve, which the efficiency formula interprets as an efficiency value above 100% [21].

What are the classic signatures of inhibition in qPCR data?

Answer: The three primary indicators of inhibition are shifts in the Quantification Cycle (Cq), changes in amplification efficiency, and abnormal amplification curve shapes.

- Cq Shift: Inhibited samples show a delay in Cq compared to uninhibited samples with the same starting template quantity. This means more cycles are required for the fluorescence to cross the detection threshold [23].

- Abnormal Efficiency: The calculated PCR efficiency may fall outside the acceptable range (typically 90-110%). As noted above, both lower and falsely high efficiency values can indicate inhibition [21] [24].

- Curve Abnormalities: The amplification curve may exhibit a flatter slope in the exponential phase, a lower plateau phase, or a higher fluorescence baseline [22].

The table below summarizes these key signatures and their interpretations.

Table 1: Key Signatures of qPCR Inhibition

| Parameter | Normal Indication | Sign of Potential Inhibition |

|---|---|---|

| Cq Value | As expected for a given template concentration. | Delayed Cq (higher value) in affected samples [23]. |

| Amplification Efficiency | Between 90% and 110% [25]. | Efficiency below 90% or a calculated value significantly above 110% [21]. |

| Standard Curve Slope | Approximately -3.32 [22]. | A slope significantly shallower or steeper than -3.32. |

| Amplification Curve | Smooth, S-shaped with a clear exponential phase and plateau. | Flattened exponential phase, depressed plateau, or elevated baseline [22]. |

Detection & Diagnosis: Methodologies for Identifying Inhibition

How can I experimentally test for the presence of inhibitors in my sample?

Answer: The most robust method is to use an internal or external control. Here is a detailed protocol:

Protocol: Using an External Control to Detect Inhibition

- Obtain a Control: Use a known quantity of a standardized nucleic acid. This can be a synthetic gene transcript, a plasmid, or a control RNA like Hepatitis G virus RNA [23].

- Spike the Sample: Divide your sample extract into two aliquots.

- Aliquot A (Test): Add a known amount of the control nucleic acid.

- Aliquot B (Reference): Add the same amount of control nucleic acid to a clean, inhibitor-free buffer (e.g., nuclease-free water).

- Run qPCR: Perform the qPCR assay targeting the control nucleic acid on both aliquots.

- Calculate ΔCq: Determine the difference in Cq values between the spiked sample (Aliquot A) and the spiked buffer (Aliquot B).

- Formula: ΔCq = Cqsample - Cqbuffer

- Interpretation: A significant ΔCq (e.g., > 0.5 cycles) indicates the presence of inhibitors in the sample extract. The larger the ΔCq, the stronger the inhibition [23].

How does inhibition lead to an amplification efficiency calculation of over 100%?

Answer: This artifact occurs due to the non-linear effects of inhibitors in a serial dilution experiment used to generate a standard curve [21]. The following diagram illustrates the logical process that leads to this miscalculation.

The mechanism is as follows: Inhibitors are often present in the most concentrated samples but become diluted to non-inhibitory levels in the more diluted samples [21]. This means the concentrated samples have artificially high Cq values (due to inhibition), while the diluted samples have the expected Cq values. When these points are plotted, the regression line has a shallower slope. Since the PCR efficiency (E) is calculated using the formula E = 10^(-1/slope) - 1, a shallower slope results in a calculated efficiency value that exceeds 100% [21].

What are the specific effects of reverse transcriptase (RT) on PCR inhibition?

Answer: In RT-qPCR, the reverse transcriptase enzyme itself can be a potent inhibitor of the subsequent PCR amplification, especially when low amounts of RNA are used and the RT reaction is not purified prior to PCR [26] [27]. The inhibition manifests as a global effect, impacting the amplification of various transcripts to different degrees and leading to inaccurate efficiency calculations [26]. The recommended solution is to purify the cDNA product after reverse transcription using methods like phenol-chloroform extraction followed by ethanol precipitation to remove the inhibiting RT enzyme [26].

Troubleshooting & Mitigation: Research Reagent Solutions

Answer: Clinical samples are a common source of various inhibitors. The table below lists key inhibitors found in different sample types and their mechanisms of action.

Table 2: Common Inhibitors in Clinical Samples and Their Mechanisms

| Sample Type | Common Inhibitors | Primary Mechanism of Inhibition |

|---|---|---|

| Blood / Serum / Plasma | Hemoglobin, Heparin, Immunoglobulin G (IgG), Lactoferrin [2] | IgG binds single-stranded DNA; Heparin inhibits polymerase; Hemoglobin degrades [3]. |

| Feces | Complex Polysaccharides, Bile Salts, Bacterial Debris [3] | Degrade polymerase; bind nucleic acids; deplete Mg²⁺ ions [2]. |

| Urine | Urea, Salts (NaCl) | Denatures polymerase; disrupts reaction buffer conditions [3]. |

| Tissues | Melanin, Collagen, Lipids, Polysaccharides | Binds to polymerase; interacts with template DNA [3]. |

What practical steps can I take to prevent or overcome inhibition?

Answer: A multi-pronged approach is most effective. The following workflow outlines a systematic strategy for detecting and mitigating inhibition.

1. Improve Nucleic Acid Extraction:

- Purification Kits: Use purification kits specifically designed for challenging sample types, many of which include inhibitor-removal steps [3].

- Sample Dilution: A simple and effective method. Diluting the sample extract reduces the concentration of the inhibitor, potentially below its effective threshold, though this also dilutes the target [21] [3].

- Advanced Purification: For stubborn inhibition, methods like phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (PCI) extraction followed by ethanol precipitation can effectively remove proteins and other contaminants [26].

2. Optimize the qPCR Reaction:

- Inhibitor-Tolerant Polymerases: Select DNA polymerases engineered for high resistance to common inhibitors found in blood, feces, and other complex matrices [2] [3].

- Reaction Facilitators: Add compounds like Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) or the T4 gene 32 protein (gp32), which can bind to inhibitory substances and prevent them from interfering with the polymerase [2] [3].

- Additives: Organic solvents like Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) or solutes like Betaine can help ameliorate inhibition by improving amplification specificity and efficiency [3].

What are the essential reagents for tackling qPCR inhibition?

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Inhibition Problems

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Inhibitor-Tolerant DNA Polymerase | Enzyme resistant to inhibition by substances like humic acid, heparin, and hematin [2] [3]. | Amplification from direct blood or soil samples. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | Binds to inhibitory compounds, preventing them from interfering with the polymerase [23] [3]. | Mitigating inhibition from phenolics or humic substances. |

| T4 Gene 32 Protein (gp32) | A single-stranded DNA-binding protein that stabilizes nucleic acids and relieves inhibition [27] [3]. | Improving RT-PCR efficiency and amplifying long targets. |

| External Control RNA/DNA | A known quantity of non-target nucleic acid used to spike samples and measure ΔCq for inhibition detection [23]. | Quality control for nucleic acid extracts from clinical or environmental samples. |

| Phenol-Chloroform-Isoamyl Alcohol (PCI) | Organic extraction mixture for purifying nucleic acids and removing proteins and other contaminants [26]. | Post-reverse transcription cleanup to remove inhibiting enzymes. |

The Critical Role of Sample Collection and Handling in Minimizing Pre-Analytical Inhibition

For researchers in drug development and clinical diagnostics, achieving reliable qPCR results is paramount. A significant challenge is pre-analytical inhibition, where substances introduced or concentrated during sample collection and handling can inhibit or interfere with the qPCR reaction, leading to false negatives, inaccurate quantification, and failed experiments [2] [28]. This guide details the critical steps to minimize these variables at the source, ensuring the integrity of your molecular data from collection to amplification.

Understanding Pre-Analytical Inhibition

What are PCR inhibitors? PCR inhibitors are molecules that interfere with the biochemical processes of qPCR, dPCR, or massively parallel sequencing (MPS). They can originate from the sample itself (e.g., hemoglobin from blood, humic substances from soil), the sample matrix, or reagents added during sample processing [2].

How do they affect your results? Inhibitors act through several mechanisms:

- Reducing DNA polymerase activity, leading to inefficient amplification and higher quantification cycle (Cq) values [2].

- Interacting with nucleic acids, preventing proper denaturation and primer annealing [2].

- Quenching fluorescence, which distorts the fluorescence measurements essential for qPCR and sequencing-by-synthesis technologies [2].

The following diagram outlines the journey of a sample and the potential points where inhibitors can be introduced or controlled.

Common Inhibitors & Sample-Specific Challenges

Different sample types present unique inhibitory challenges. Understanding these is the first step toward effective prevention.

Table 1: Common PCR Inhibitors by Sample Type

| Sample Type | Common Inhibitors | Impact on PCR |

|---|---|---|

| Whole Blood & Plasma | Hemoglobin, Immunoglobulin G (IgG), Lactoferrin, Heparin, EDTA [2] | Heparin is a potent inhibitor of PCR; hemoglobin and IgG can bind to DNA polymerase [2] [28]. |

| Tissues (FFPE) | Formalin-induced cross-links, Porphyrins [28] | Cross-links fragment DNA and reduce extraction efficiency; porphyrins can inhibit DNA polymerase [28]. |

| Stool & Fecal | Bilirubin, Bile Salts, Complex Polysaccharides [28] | Can interfere with the DNA polymerase and nucleic acid denaturation. |

| Soil & Environment | Humic Acid, Fulvic Acid [2] | Among the most potent inhibitors; humic acid can mimic DNA and inhibit polymerase activity [2]. |

| Plant Materials | Polysaccharides, Polyphenols [2] | Can co-precipitate with nucleic acids during extraction. |

Best Practices for Sample Collection & Handling

Mitigating pre-analytical errors requires a proactive and meticulous approach at every stage.

Sample Collection

- Use Appropriate Containers: Ensure collection tubes are compatible with your downstream application. For example, avoid heparinized tubes for blood collection as heparin is a known PCR inhibitor [2] [28].

- Minimize Contamination: Use single-use, DNA-free swabs and collection vessels. For low-biomass samples, decontaminate surfaces and equipment with DNA-degrading solutions (e.g., 10% bleach) and use personal protective equipment (PPE) to reduce human-derived contamination [29].

- Standardize Collection: Use consistent techniques to avoid introducing inhibitors from the patient's skin or the environment [29] [30].

Transport and Storage

Improper handling post-collection can degrade samples or stabilize inhibitors. Adhering to time and temperature specifications is critical for preserving nucleic acid integrity.

Table 2: Pre-analytical Storage Guidelines for Common Samples Data compiled from recommendations for optimal molecular analysis [28].

| Specimen Type | Target | Short-Term Storage | Long-Term Storage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Whole Blood | DNA | Room Temperature (RT): up to 24h; 2-8°C: up to 72h (optimal) [28] | -20°C or lower |

| Plasma | DNA | RT: 24h; 2-8°C: 5 days [28] | -20°C: >5 days; -80°C: months to years [28] |

| Plasma | RNA (e.g., HIV, HCV) | 4-8°C: up to 1 week [28] | -80°C |

| Stool | DNA | RT: ≤4h; 4°C: 24-48h [28] | -20°C: few weeks; -80°C: up to 2 years [28] |

| Swabs (in VTM) | DNA/RNA | 4°C: 3-4 days [28] | -70°C: for longer storage [28] |

| Tissues (Fresh) | DNA/RNA | Cold ischemia time should be limited (e.g., <1 hour for DNA) [28] | Snap-freezing in liquid N₂ is optimal |

Nucleic Acid Extraction

This is a critical control point for removing inhibitors.

- Choose the Right Method: Silica-based magnetic bead methods, particularly those using guanidinium thiocyanate buffers, are excellent at denaturing proteins and inactivating nucleases, leading to better inhibitor removal [31] [28].

- Optimize for Efficiency: High-yield extraction methods like the SHIFT-SP protocol can recover nearly all nucleic acids in a sample, improving the detection of low-abundance targets and diluting out residual inhibitors [31].

- Ensure Thorough Washing: Incomplete washing of beads or columns can leave behind chaotropic salts (like guanidine) and other reagents that are potent PCR inhibitors [31].

Troubleshooting FAQs

Q: My no-template control (NTC) shows amplification. What went wrong? A: Amplification in the NTC indicates contamination. This is likely due to splashing of template between wells, contaminated reagents, or primer-dimer formation. Clean your work area and pipettes with 10% bleach or 70% ethanol, prepare fresh primer dilutions, and ensure your NTC is spatially separated from sample wells on the plate [6].

Q: I have inconsistent results between biological replicates. What should I check? A: This often points to issues with sample integrity or minimal starting material. Check the concentration and quality of your nucleic acids (e.g., A260/280 ratio). RNA degradation is a common cause. You may need to repeat the extraction using a method better suited to your sample type [6].

Q: My Cq values are much later than expected, or amplification fails entirely. Is this inhibition? A: Yes, this is a classic sign of PCR inhibition. First, dilute your template DNA to see if Cq values improve, as this can dilute inhibitors. Ensure your standard curve was prepared fresh and that pipetting was accurate. Applying an inhibitor-tolerant DNA polymerase blend can also provide a more robust solution than purification alone [2] [6].

Q: For low-biomass samples, how can I be sure my signal is real? A: Always include negative controls (e.g., blank swabs, empty collection tubes, lysis buffer without sample) that undergo the entire extraction and analysis process. The microbial profile of your sample should be significantly distinct from these controls. Contamination from reagents or the environment is a major concern in low-biomass studies, and controls are essential for distinguishing signal from noise [29].

Featured Protocol: SHIFT-SP for Rapid, High-Yield NA Extraction

The Silica bead based HIgh yield Fast Tip based Sample Prep (SHIFT-SP) method is a magnetic bead-based nucleic acid extraction optimized for speed (6-7 minutes) and high efficiency [31].

Key Optimizations:

- Low pH Binding: Using a lysis binding buffer (LBB) at pH 4.1, instead of pH 8.6, reduces electrostatic repulsion between the negatively charged silica and DNA, increasing binding efficiency to >98% within 10 minutes [31].

- Tip-Based Mixing: Aspirating and dispensing the binding mix with the pipette tip for 1-2 minutes exposes beads to the sample more rapidly than orbital shaking, achieving ~85% DNA binding in 1 minute compared to ~61% with shaking [31].

- Optimized Elution: Using a low-salt elution buffer at a slightly elevated temperature (e.g., 62°C) improves the efficiency and speed of nucleic acid release from the beads [31].

Table 3: The Scientist's Toolkit - Key Reagent Solutions Based on the SHIFT-SP protocol and general best practices [31] [2] [28].

| Reagent / Material | Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Silica-coated Magnetic Beads | Solid matrix for nucleic acid binding | Bead size and surface area affect binding capacity and kinetics. |

| Lysis Binding Buffer (LBB) with Guanidine Salts | Cell lysis and nucleic acid binding to silica | A low pH (~4.1) LBB significantly enhances DNA binding efficiency [31]. |

| Wash Buffer (with Ethanol) | Removes salts, proteins, and other impurities | Incomplete washing is a major source of inhibitor carryover. |

| Nuclease-free Water or Low-Salt Elution Buffer | Elutes purified nucleic acids from beads | Using a slightly basic buffer (pH 8-9) and pre-heating can increase elution yield [31]. |

| Inhibitor-Tolerant DNA Polymerase | Enzymatic amplification of target DNA | Polymerase blends are often more resistant to common inhibitors than single enzymes [2]. |

Experimental Workflow for Validation

To systematically validate that your pre-analytical steps are effectively controlling inhibition, follow this workflow.

Key Metrics to Assess:

- Amplification Efficiency: Should be between 90-110%. Poor efficiency is a key indicator of inhibition or other assay issues [32] [19].

- DNA/RNA Yield: Compare to the expected input. Low yield can indicate poor extraction efficiency or degradation during collection/storage [31].

- Cq Values: Compare spiked samples to controls. A significant delay in Cq suggests the presence of inhibitors [2].

Practical Guide to Inhibitor Removal and Direct PCR Methods for Clinical Matrices

Robust Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits with Inhibitor Removal Technology (IRT)

FAQs: Understanding Inhibitor Removal Technology

1. What are the most common PCR inhibitors found in clinical samples? Clinical samples contain various substances that can inhibit downstream molecular assays. Common inhibitors include hemoglobin from blood, heparin from anticoagulated tissues, immunoglobulin G (IgG), and complex polysaccharides. In samples like nasopharyngeal fluids or saliva, inhibitors such as mucin and RNases are also frequently encountered [1] [33].

2. How does Inhibitor Removal Technology (IRT) work in nucleic acid extraction kits? IRT encompasses specialized chemistries and solid-phase matrices designed to selectively bind and remove inhibitory substances. Many kits use a silica matrix or magnetic silica beads. In the presence of chaotropic salts (e.g., guanidine), the silica surface facilitates the binding of nucleic acids while allowing contaminants to be washed away. Some advanced chemistries, like those in Promega's GoTaq Endure master mix, are specifically formulated for high tolerance to a wide range of inhibitors [1] [34] [35].

3. My qPCR results show delayed Cq values. Could this be due to inhibitors, and how can I confirm it? Yes, delayed Cq values are a primary indicator of potential inhibition. To confirm, you can use an internal PCR control (IPC). If the IPC also shows a delayed Cq, inhibition is likely. Another method is a spike-in test, where you add a known quantity of exogenous DNA to your sample extract and run a corresponding assay. A higher Cq in the spiked sample compared to the control indicates the presence of inhibitors [1] [34].

4. Besides using an IRT kit, what other strategies can help overcome PCR inhibition? Several post-extraction strategies can mitigate inhibition:

- Sample Dilution: A 10-fold dilution of the extracted nucleic acid can reduce inhibitor concentration below a critical threshold.

- PCR Enhancers: Adding Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) or T4 gene 32 protein (gp32) to the PCR reaction can bind to and neutralize inhibitors.

- Robust Master Mixes: Using inhibitor-tolerant master mixes, such as TaqMan Environmental Master Mix, can significantly improve resistance to inhibitors like humic acid [34] [13].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Extraction and Inhibition Issues

Problem 1: Low Nucleic Acid Yield

| Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Incomplete cell lysis | Increase lysis incubation time or agitation speed. Use a more aggressive lysing matrix or enzymatic digestion tailored to your sample type [36] [37]. |

| Inefficient binding to solid phase | Ensure the binding buffer has the correct pH and composition. For silica-based methods, a lower pH (e.g., ~4.1) can enhance nucleic acid binding. Optimize incubation time and mixing to maximize contact [36] [31]. |

| Overwhelmed binding capacity | Do not exceed the recommended sample input. For samples with high cellular content, split the sample and perform extractions separately [37] [38]. |

Problem 2: Poor Purity and Presence of Inhibitors

| Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Carryover of contaminants | Perform additional thorough washing steps with the provided wash buffers. Ensure wash buffers are completely removed before elution [36] [38]. |

| Co-purification of inhibitors | Use a dedicated IRT kit. For silica columns, extra washes with 70-80% ethanol can help remove guanidine salts. For persistent inhibitors like polysaccharides, consider a post-extraction cleanup with paramagnetic beads [34] [38]. |

| Sample-specific inhibitors | For blood samples, avoid heparin as an anticoagulant; EDTA is preferred. Remove protein precipitates by centrifugation before loading the lysate onto a spin filter [1] [37]. |

Problem 3: Inconsistent qPCR Results

| Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Incomplete inhibitor removal | Implement a quality control step to check for inhibitors using an IPC or spike-in assay. Consider switching to a more robust, inhibitor-tolerant master mix [1] [34]. |

| Nucleic acid degradation | Work quickly and on ice. Use RNase inhibitors for RNA and ensure all reagents are nuclease-free. Store extracted nucleic acids at -80°C and avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles [36] [37]. |

| Cross-contamination | Use aerosol-resistant pipette tips and process samples in a unidirectional workflow. Utilize closed-system automated extractors, like the Four E's Scientific MultiEX series, to minimize risk [36]. |

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Protocol 1: Validating Inhibitor Removal Using an Internal PCR Control (IPC)

This protocol helps detect the presence of inhibitors in your extracted nucleic acids.

- Select an IPC: This can be a synthetic DNA sequence, a plasmid, or an organism not present in your samples.

- Prepare Reactions:

- Test Reaction: Add a fixed, known amount of the IPC to your sample's nucleic acid extract.

- Control Reaction: Add the same amount of IPC to a nuclease-free water or a known inhibitor-free sample.

- Run qPCR: Perform qPCR using an assay specific to the IPC target.

- Analyze Results: A significant delay (e.g., ΔCq > 1) in the test reaction's Cq compared to the control reaction indicates the presence of inhibitors in your sample extract [34].

Protocol 2: Evaluating IRT Kit Efficiency with Spike-and-Recovery

This quantitative protocol compares the performance of different extraction methods.

- Spike Sample: Introduce a known concentration of a target organism (e.g., heat-inactivated SARS-CoV-2) into your clinical sample matrix (e.g., saliva, blood).

- Extract Nucleic Acids: Process the spiked sample using the IRT kit you are evaluating and, for comparison, a reference method (e.g., a traditional silica-column kit).

- Perform qPCR: Quantify the recovered nucleic acid from both methods using a target-specific assay.

- Calculate Recovery: Determine the nucleic acid recovery rate. A high-performance IRT kit should yield recovery rates of 90–110%, comparable to or better than the reference method, with a strong correlation (R² > 0.95) in standard samples [33].

Performance Data of Extraction Technologies

The following table summarizes key performance metrics from recent studies on various nucleic acid extraction technologies, highlighting their efficiency and speed.

Table 1: Comparison of Nucleic Acid Extraction Method Performance

| Extraction Method | Extraction Time | Nucleic Acid Recovery Rate | Key Advantages | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silica Pipette Tip Column | < 3 minutes | 90–110% | Equipment-free, rapid, cost-effective, high portability for point-of-care use. | [33] |

| Magnetic Silica Bead (SHIFT-SP) | 6–7 minutes | ~96% (at high input) | Very fast, high yield, automation compatible, efficient for both DNA and RNA. | [31] |

| Traditional Silica Column (Commercial Kit) | ~25-40 minutes | ~50% (comparative yield) | Established, reliable method; considered a gold standard in many labs. | [33] [31] |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents for Overcoming PCR Inhibition

| Reagent / Solution | Function in Inhibitor Removal | |

|---|---|---|

| Chaotropic Salts (e.g., Guanidine HCl) | Disrupts hydrogen bonding, denatures proteins, and facilitates binding of nucleic acids to silica surfaces in the presence of inhibitors. | [33] [31] |

| Inhibitor-Tolerant Master Mix (e.g., GoTaq Endure) | Specially formulated polymerases and buffer components that maintain activity in the presence of common inhibitors found in blood, soil, and plants. | [1] |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | Binds to and neutralizes a range of inhibitors, including phenols and humic acids, preventing them from interfering with the polymerase. | [1] [13] |

| T4 Gene 32 Protein (gp32) | A single-stranded DNA-binding protein that stabilizes DNA and has been shown to effectively bind inhibitors in complex matrices like wastewater. | [13] |

| M-PVA Magnetic Beads | Paramagnetic beads used in automated systems for solid-phase nucleic acid extraction, offering consistent purity and reduced cross-contamination risk. | [35] |

Workflow: Navigating Inhibitor Challenges

The diagram below outlines a logical workflow for diagnosing and addressing inhibitor-related issues in your qPCR experiments.

For researchers in clinical and drug development, obtaining reliable quantitative PCR (qPCR) results from direct samples is often hindered by co-purified inhibitors. Traditional DNA extraction, while effective at removing these substances, adds significant time, cost, and can lead to DNA loss. This guide details direct protocols using heat treatment and osmotic lysis to prepare clinical samples for qPCR, providing a robust, cost-effective alternative that integrates seamlessly into high-throughput workflows. These methods effectively lyse cells to release nucleic acids while mitigating the impact of common PCR inhibitors, enabling accurate molecular diagnostics and genetic analysis.

Core Principles: How Direct Lysis Works

Direct protocols bypass conventional DNA extraction kits by using physical and chemical means to lyse cells and make nucleic acids accessible for amplification.

- Osmotic Lysis: Cells are suspended in a hypotonic solution, such as distilled water. The lower solute concentration outside the cell causes water to rush inward by osmosis, leading to cellular swelling and eventual rupture of the cell membrane [39].

- Heat Treatment: Applying high heat (e.g., 95°C) disrupts cellular membranes and denatures proteins, facilitating the release of genomic DNA. Heat also helps to inactivate nucleases and some inhibitors [4] [40].

- Combined Effect: The sequential application of osmotic pressure and heat creates a synergistic lysis effect. The osmotic shock weakens the cell structure, making it more susceptible to disruption by subsequent heat treatment.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: GG-RT PCR for Whole Blood

This "Greater temperature, Greater speed" Real-Time PCR method is designed for EDTA-treated whole blood [4] [40].

- Step 1: Sample Preparation

- Mix 400 µL of whole blood with 100 µL of distilled water. This creates an approximate 20% dilution, establishing a hypotonic environment for osmotic lysis.

- Step 2: Heat-Induced Lysis

- Incubate the diluted blood sample at 95°C for 20 minutes.

- During incubation, vortex the sample 2-3 times to ensure uniform heating and lysis.

- Step 3: Clarification

- Centrifuge the heated sample at 14,000 rpm for 5 minutes. This pellets cell debris and denatured proteins.

- Step 4: Template Preparation

- Carefully collect the supernatant. This clear lysate contains the released DNA and is used directly as a PCR template.

- For optimal results in real-time PCR, dilute the lysate 1:5 or 1:10 with nuclease-free water before adding it to the reaction mix. This dilution further reduces the concentration of potential PCR inhibitors.

- Step 5: Real-Time PCR

- Use 2.5 µL of the diluted lysate per 10 µL PCR reaction.

- Standard SYBR Green-based real-time PCR protocols can be used. The method has been successfully tested with annealing temperatures of 60°C and 61°C [4].

Protocol 2: Troubleshooting and Enhancement Strategies

If the basic protocol yields suboptimal amplification, consider these enhancements informed by research on complex samples [13] [1].

- Add PCR Enhancers:

- Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA): Add to a final concentration of 0.1-0.5 µg/µL. BSA binds to inhibitors like humic acids and heparin, preventing them from interfering with the polymerase [13] [41].

- T4 Gene 32 Protein (gp32): Add to a final concentration of 0.2 µg/µL. This protein stabilizes single-stranded DNA and has been shown to be highly effective at overcoming inhibition in complex matrices [13].

- Optimize Reaction Conditions:

- Use a hot-start polymerase to improve specificity and reduce primer-dimer formation.

- Consider using a commercial master mix specifically formulated for inhibitor tolerance [1].

The following workflow summarizes the core GG-RT PCR protocol and key troubleshooting pathways:

Performance Data and Validation

The GG-RT PCR method has been quantitatively validated. The table below summarizes qPCR performance metrics comparing the direct lysate method against traditional DNA isolation [4].

Table 1: qPCR Efficiency Comparison Between Traditional DNA Isolation and Direct GG-RT PCR

| Target Gene | Amplicon Size (bp) | DNA Sample PCR Efficiency | GG-RT PCR Efficiency (1:10 Lysate) | Efficiency Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACTB | 112 | 95% | 75% | 20% |

| PIK3CA | 114 | 92% | 78% | 14% |

| All 9 Tested Genes | 100 - 268 | Successful amplification | Successful amplification at 60°C & 61°C | All genes amplified successfully |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the main advantages of using this direct lysis method over commercial DNA extraction kits? The primary advantages are significant cost reduction by eliminating expensive kits, faster processing time by removing multiple purification steps, and the prevention of DNA loss associated with extraction columns, which can be crucial for samples with low cellularity [4] [40].

Q2: Why is dilution of the blood lysate necessary before qPCR? Dilution reduces the concentration of PCR inhibitors inherent in whole blood, such as hemoglobin, immunoglobulins, and lactoferrin, which can suppress polymerase activity. A 1:5 or 1:10 dilution optimizes the balance between template DNA concentration and inhibitor levels [4] [1].

Q3: Can this protocol be used with other sample types, like tissue or saliva? While optimized for whole blood, the core principles can be adapted. Tissues may require initial mechanical disruption (e.g., grinding). Saliva, which contains different inhibitors, might need optimization of the lysis buffer or dilution factor. Empirical validation is recommended for new sample matrices.

Q4: What are the signs of PCR inhibition in my results, and how can I confirm it? Key indicators include delayed quantification cycle (Cq) values, poor amplification efficiency (outside 90-110%), abnormal amplification curves, or reaction failure. Running an internal PCR control (IPC) is the best way to confirm inhibition; a delayed IPC Cq confirms inhibitors are affecting the reaction [1].

Q5: The protocol mentions EDTA-treated blood. Can other anticoagulants be used? The original study used EDTA. Other anticoagulants like heparin are strong PCR inhibitors and are not recommended unless a specific enhancement step (e.g., addition of heparinase or a potent enhancer like gp32) is included [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents and Their Functions in Direct Lysis Protocols

| Reagent/Solution | Function in the Protocol | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Distilled Water | Creates a hypotonic solution for osmotic cell swelling and lysis. | Must be nuclease-free to prevent DNA degradation. |

| EDTA (Anticoagulant) | Prevents blood coagulation and chelates Mg²⁺, which can be a cofactor for nucleases. | Preferred over heparin, which is a known PCR inhibitor. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | PCR enhancer; binds to inhibitors like humic acids and immunoglobulins, neutralizing their effects. | Typical final concentration ranges from 0.1 to 0.5 µg/µL [13] [41]. |

| T4 Gene 32 Protein (gp32) | PCR enhancer; stabilizes single-stranded DNA and is highly effective at countering various inhibitors. | A final concentration of 0.2 µg/µL was found to be highly effective in wastewater studies [13]. |

| SYBR Green Master Mix | For real-time PCR detection; contains DNA polymerase, dNTPs, buffer, and fluorescent dye. | Use a robust, inhibitor-tolerant master mix for better performance with complex lysates [1]. |

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) inhibition is a significant challenge in molecular diagnostics and environmental testing, leading to false-negative results and underestimated target concentrations. Inhibitors commonly found in clinical and environmental samples—such as humic acids, polyphenols, metal ions, and complex polysaccharides—can co-extract with nucleic acids and interfere with polymerase activity [41] [42]. Effective removal of these contaminants is therefore a critical prerequisite for reliable quantitative PCR (qPCR) and reverse transcription qPCR (RT-qPCR) results, particularly in complex matrices like blood-stained soil, wastewater, and clinical specimens [43] [42]. This technical resource center provides validated protocols and troubleshooting guidance for using chemical and polymeric adsorbents to overcome PCR inhibition, supporting robust and reproducible molecular research.

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

DAX-8 Protocol for Humic Acid Removal

Principle: Supelite DAX-8 is a polymeric adsorbent that selectively binds and permanently removes humic acids from nucleic acid extracts, significantly improving qPCR amplification efficiency [41] [44].

Materials:

- Supelite DAX-8 resin

- Concentrated environmental water sample or nucleic acid extract

- Centrifuge and appropriate tubes

- QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (or equivalent)

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: After the sample reconcentration step, take a 100-500 µL aliquot of the concentrate.

- Adsorbent Addition: Add DAX-8 resin to the sample at a concentration of 5% (w/v) [41]. For example, add 50 mg of DAX-8 to 1 mL of sample.

- Mixing: Mix the sample and resin thoroughly for 15 minutes at room temperature to ensure sufficient contact between the inhibitors and the adsorbent [41].

- Separation: Centrifuge the mixture at 8,000 rpm for 5 minutes at 4°C to pellet the insoluble DAX-8 polymer [41].

- Supernatant Collection: Carefully transfer the supernatant to a fresh tube. This supernatant contains the inhibitor-free nucleic acids and is ready for downstream extraction or analysis.

- Validation: It is recommended to verify the removal of inhibitors by spiking a sample with a known quantity of a control virus (e.g., Murine Norovirus) and comparing qPCR cycle threshold (Ct) values before and after treatment [41].

Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) Pre-treatment Protocol

Principle: PVP forms hydrogen bonds with phenolic compounds, including humic acids, effectively precipitating them from solution. This pre-treatment is particularly useful for forensic samples like blood-stained soil [42].

Materials:

- Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP)

- Sample (e.g., blood-stained soil suspension)

- Centrifuge

Procedure:

- Stock Solution Preparation: Prepare a 10% (w/v) stock solution of PVP in distilled, deionized water (ddH₂O) and store at 4°C [41].

- Pre-treatment: Add the PVP stock solution to the sample. For soil samples, a common ratio is 250 µL of PVP stock per 1 mL of sample [41] [42].

- Incubation: Incubate the mixture for a specified time (e.g., 30 minutes) at room temperature, with gentle mixing.

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge the sample to pellet the PVP-inhibitor complex.

- Supernatant Transfer: Transfer the cleared supernatant to a new tube for subsequent DNA extraction using a standard method, such as a proteinase K digestion followed by silica magnetic bead purification [42].

Silica Membrane-Based DNA Purification

Principle: Silica membranes bind DNA in the presence of high-salt chaotropic agents, allowing inhibitors to be washed away. This method is highly effective for a wide range of clinical specimens [43].

Materials:

- Commercial silica membrane kit (e.g., QIAamp DNA Mini Kit)

- Clinical sample (respiratory, non-respiratory)

Procedure:

- Sample Lysis: Mix the sample with the provided lysis buffer. This step disrupts cells and releases nucleic acids.

- Binding: Apply the lysate to the silica membrane column. DNA binds to the membrane under high-salt conditions while inhibitors remain in solution.

- Washing: Perform two wash steps with provided wash buffers to remove residual contaminants and salts.

- Elution: Elute the purified DNA in a low-salt buffer or nuclease-free water.

- Efficiency: This protocol reduced PCR inhibition rates from 12.5% to 1.1% in a study of 655 clinical samples, demonstrating high effectiveness across respiratory and non-respiratory specimens [43].

Comparative Data of Inhibitor Removal Methods

Table 1: Performance comparison of different PCR inhibitor removal methods.

| Method | Mechanism of Action | Key Applications | Reported Efficacy/Outcome | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DAX-8 Resin | Selective adsorption of humic acids [44] | Environmental water samples [41] | Increased MNV qPCR concentrations; permanent removal of humic acids [41] | Potential for some DNA loss; requires centrifugation separation [41] |

| PVP Pre-treatment | Hydrogen bonding with phenolic compounds [42] | Blood-stained soil, plant extracts, environmental DNA [42] | Improved human DNA profile generation from forensic samples [42] | Acts as a pre-treatment; requires subsequent DNA extraction |

| Silica Membranes | Selective DNA binding in chaotropic salts [43] | Clinical specimens (respiratory, CSF, urine) [43] | Reduced inhibition from 12.5% to 1.1% in clinical samples [43] | Integrated into commercial kits; suitable for automation |

| PowerClean Kit | Not specified in detail | Forensic samples with various inhibitors [7] | Effective removal of 8 common inhibitors; more complete STR profiles [7] | Commercial kit |

| Sample Dilution | Reduces inhibitor concentration | General purpose [41] | Can achieve maximum amplification [41] | Also dilutes the target DNA; optimal factor requires optimization [41] |

Troubleshooting & Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My samples still show PCR inhibition after using a commercial cleanup kit. What are more robust alternatives? Commercial inhibitor removal kits may not adequately remove all PCR inhibitors, particularly complex organics like humic acids [41]. Consider these alternatives:

- Use DAX-8: For environmental waters, implementing a 5% (w/v) DAX-8 treatment has been shown to outperform some commercial kits by permanently eliminating humic acids, leading to a significant increase in qPCR target concentrations [41] [44].

- Combine Methods: For challenging samples like blood-stained soil, a PVP pre-treatment prior to a standard silica-based purification has been proven to significantly improve the success rate of obtaining a reportable DNA profile [42].

Q2: How much DNA is lost when using adsorbents like DAX-8 or PVP? All adsorption methods carry a risk of co-adsorbing and losing some target nucleic acid.

- DAX-8: One study reported no significant change in the mean cycle threshold (ΔCt) for the target organism despite some DNA loss, indicating that the benefit of inhibitor removal outweighs the minor loss [44].

- General Best Practice: Always include a control (e.g., a known quantity of a surrogate virus or DNA) to quantify the loss and validate the recovery efficiency of your specific protocol [41].

Q3: Which method is best for removing humic acids from soil samples?

- Forensic/Human DNA from Soil: A PVP pre-treatment is highly recommended. Research shows that adding a PVP step before a proteinase K extraction and silica bead purification is the most effective method for generating human DNA profiles from blood-stained soil [42].

- Environmental Water Samples: DAX-8 resin is particularly effective for removing humic acids from water samples, leading to improved qPCR efficiency [41] [44].

Q4: Are silica membranes sufficient for all clinical sample types? While silica membranes are highly effective for most clinical samples, reducing inhibition to as low as 1.1% overall, some sample types remain challenging [43]. For example, lymph node specimens initially showed an inhibition rate of 51%, which was significantly reduced by the silica membrane protocol. If inhibition persists, consider combining silica purification with an additional pre-treatment or using a different adsorbent like PVP [43] [42].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential reagents for PCR inhibitor removal protocols.

| Reagent | Function/Principle | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|

| Supelite DAX-8 | Polymeric adsorbent that selectively and permanently binds humic acids [41] [44] | Environmental water sample cleanup for qPCR [41] |

| Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) | Forms hydrogen bonds with phenolic compounds (e.g., humic acids) to precipitate them [42] | Pre-treatment for forensic (blood-soil) and environmental samples [42] |

| Silica Membranes/Columns | Bind DNA under high-salt conditions, allowing inhibitors to be washed away [43] | Standardized DNA purification from clinical and complex samples [43] |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | qPCR additive that binds to inhibitors, reducing their interference with the polymerase [41] [44] | Added directly to the PCR master mix to mitigate residual inhibition |

| Proteinase K | Enzyme that digests proteins and inactivates nucleases [42] | Standard part of lysis buffer in many DNA extraction protocols |

Experimental Workflow Visualization

Diagram Title: Inhibitor Removal Workflow Selection

Diagram Title: DAX-8 Treatment Protocol

FAQ: Troubleshooting Dilution in Clinical qPCR

Q: My qPCR assay has confirmed inhibition, but when I dilute my sample, I get no signal. What should I do? A: A complete loss of signal after dilution suggests that the target concentration was very low to begin with. Dilution may have reduced the inhibitors, but also dropped the target below the detection limit. Prior to dilution, use spectrophotometric analysis (e.g., A260/A280 and A260/A230 ratios) to check for contaminants like phenol or carbohydrates that can indicate inhibition [45]. Consider using a more robust, inhibitor-tolerant master mix [1] or implementing a pre-dilution DNA cleanup step with a kit designed to remove inhibitors without significant DNA loss [46].

Q: How can I definitively confirm that inhibition is the problem and not just low target concentration? A: Use an Internal Amplification Control (IPC). Spike a known, non-target DNA sequence into your reaction master mix. If inhibitors are present, the Cq value for the IPC will be significantly delayed in the test sample compared to a clean control reaction [1] [34]. Alternatively, you can spike a control plasmid or synthetic DNA into your sample DNA and run a corresponding assay; a higher Cq in the spiked sample indicates inhibition [34].

Q: Are some sample types more prone to inhibitors that require dilution? A: Yes, clinical samples like blood, feces, and tissues are common sources of inhibitors [1]. Blood can contain hemoglobin, heparin, and immunoglobulins [1] [45]. Feces can contain bile salts and complex organics [45]. The table below summarizes common inhibitors and their effects.

| Inhibitor Source | Example Inhibitors | Effect on qPCR |

|---|---|---|

| Blood | Hemoglobin, Heparin, Immunoglobulins (IgG) | Polymerase inhibition, co-factor chelation, binding to single-stranded DNA [1] [45] |

| Tissues | Heparin, Collagen | Polymerase inhibition, disruption of primer binding [1] [45] |

| Feces | Bile Salts, Urea | Interference with enzyme activity [45] |

| Laboratory Reagents | Phenol, EDTA, SDS, Ethanol | Mg2+ chelation, template precipitation, primer binding disruption [1] [47] [45] |

Q: What is a safe starting point for dilution to avoid losing sensitivity? A: A 10-fold dilution is a common and effective starting point for mitigating inhibitors [34]. This often reduces inhibitor concentration below a critical threshold while retaining sufficient target DNA for detection. For targets with very low concentration, a 2-fold or 5-fold dilution may be a more prudent first step. The optimal dilution factor must be determined empirically for each sample type and assay.

Experimental Protocol: Establishing an Optimal Dilution Factor

This protocol outlines a systematic approach to determine the best dilution factor for your clinical sample to balance inhibitor reduction and assay sensitivity.

1. Sample Preparation:

- Extract DNA from your clinical sample using your standard method.

- Prepare a series of dilutions (e.g., 1:2, 1:5, 1:10, 1:20) of the extracted DNA using nuclease-free water or TE buffer [45]. Using the same matrix (e.g., water) for all dilutions is critical for consistency.

2. qPCR Setup:

- Include the undiluted sample and a no-template control (NTC) in the run.

- Use an IPC in every reaction to monitor for residual inhibition at each dilution level [1].

- Run all samples and controls in duplicate or triplicate for statistical robustness.

3. Data Analysis:

- Plot Cq vs. Dilution Factor: For the target assay, graph the average Cq value against the log of the dilution factor.

- Identify the Inflection Point: The optimal dilution is often where the Cq value shifts linearly with the dilution factor, indicating that the inhibitory effect has been minimized and the assay is behaving predictably.