Strategic Training Set Selection in Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling: A Guide for Robust Virtual Screening and Hit Identification

Ligand-based pharmacophore modeling is a cornerstone of computer-aided drug design, particularly for targets with unknown 3D structures.

Strategic Training Set Selection in Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling: A Guide for Robust Virtual Screening and Hit Identification

Abstract

Ligand-based pharmacophore modeling is a cornerstone of computer-aided drug design, particularly for targets with unknown 3D structures. The predictive power and success of these models are critically dependent on the strategic selection of the training set compounds used for their generation. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the best practices for assembling effective training sets. We explore the foundational principles of chemical diversity and feature representation, detail methodological approaches for sourcing and curating 2D and 3D ligand data, address common challenges and optimization strategies using both classical and modern machine learning techniques, and finally, outline rigorous validation and comparative analysis protocols to assess model performance. By synthesizing current methodologies and emerging trends, this guide aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to build highly predictive pharmacophore models that accelerate lead discovery.

Laying the Groundwork: Core Principles of Chemical Diversity and Feature Representation

Core Concept and Feature Definitions

What is a pharmacophore and what are its essential features?

A pharmacophore is an abstract description of molecular features necessary for molecular recognition of a ligand by a biological macromolecule. According to the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC), it is "an ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target and to trigger (or block) its biological response" [1] [2]. It does not represent a real molecule or specific functional groups, but rather the common molecular interaction capacities of a group of compounds toward their target structure [2].

The table below summarizes the essential steric and electronic features that constitute a pharmacophore model:

Table 1: Essential Pharmacophore Features and Their Descriptions

| Feature Type | Description | Chemical Groups Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Bond Acceptor (HBA) | Atom that can accept a hydrogen bond through lone pair electrons | Carboxyl, carbonyl, ether oxygen |

| Hydrogen Bond Donor (HBD) | Atom with hydrogen that can donate a bond to an acceptor | Hydroxyl, primary amine, amide NH |

| Hydrophobic (H) | Non-polar regions that favor lipid environments | Alkyl chains, cycloalkanes, steroidal skeletons |

| Aromatic (ARO) | Planar ring systems with delocalized π-electrons | Phenyl, pyridine, fused aromatic rings |

| Positively Ionizable (PI) | Groups that can carry or develop positive charge | Primary, secondary, tertiary amines |

| Negatively Ionizable (NI) | Groups that can carry or develop negative charge | Carboxylic acid, phosphate, sulfate |

| Exclusion Volumes (XVOL) | Spatial regions occupied by the receptor that ligands must avoid | Defined areas representing protein atoms |

These features ensure optimal supramolecular interactions with specific biological targets [3] [2]. A well-defined pharmacophore model includes both hydrophobic volumes and hydrogen bond vectors to represent the key interactions between a ligand and its receptor [1].

Troubleshooting Guides: Training Set Selection

FAQ: What are the common challenges in training set selection for ligand-based pharmacophore modeling?

Challenge 1: Inadequate structural diversity in training set

- Problem: Training set compounds are too structurally similar, resulting in a pharmacophore model that is too specific to recognize novel chemotypes.

- Solution: Select a structurally diverse set of molecules that will be used for developing the pharmacophore model. The set should include both active and inactive compounds to ensure the model can discriminate between molecules with and without bioactivity [1] [4].

- Validation: Use clustering methods like Butina clustering with 2D pharmacophore fingerprints to ensure representative diversity [4].

Challenge 2: Insufficient coverage of activity range

- Problem: Training set compounds have limited activity range, reducing model predictability.

- Solution: Include compounds across the entire activity spectrum (highly active, moderately active, and inactive) categorized by IC₅₀ values:

- Most active: <0.1 μM

- Active: 0.1 μM to 1.0 μM

- Moderately active: 1.0 μM to 10.0 μM

- Inactive: >10.0 μM [5]

- Validation: Ensure statistical relevance by including a maximum number of active compounds along with few moderately active and inactive compounds [5].

Challenge 3: Inconsistent biological data

- Problem: Biological activities collected from different assay conditions or cell lines introduce noise.

- Solution: Use biological data obtained from homogeneous procedures against a single biological target or cell line [5].

- Validation: Confirm all experimental inhibitory activities were collected using the same biological assays and assessment methods [5].

Challenge 4: Improper conformational sampling

- Problem: Inadequate representation of possible low-energy conformations leads to incorrect bioactive conformation identification.

- Solution: Generate a set of low energy conformations that is likely to contain the bioactive conformation for each molecule. Use algorithms that sample conformational space extensively (up to 100 conformers per molecule within a 50 kcal/mol energy window) [1] [4].

- Validation: Apply poling techniques or Monte Carlo sampling to promote conformational variation and avoid bias toward folded structures [6].

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Methodology: Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling with 3D-QSAR

This protocol outlines the generation of a quantitative pharmacophore model using the HypoGen algorithm for Topoisomerase I inhibitors, as demonstrated in published research [5].

Phase 1: Training and Test Set Preparation

- Data Compilation: Collect 62 camptothecin derivatives with experimental IC₅₀ values determined against A549 cancer cell lines under consistent assay conditions [5].

- Activity Categorization:

- Classify compounds into four activity categories based on IC₅₀ values

- Distribute compounds to ensure all chemical substitution patterns are represented

- Training Set Selection: Select 29 diverse compounds spanning the activity range (IC₅₀ 0.003 μM to 11.4 μM) representing different structural classes [5].

- Test Set Selection: Use remaining 33 compounds for model validation [5].

Phase 2: Compound Preparation and Conformational Analysis

- 2D Structure Drawing: Draw molecular structures using ChemDraw Ultra [5].

- 3D Conversion and Optimization: Convert to 3D structures using Discovery Studio and optimize with CHARMM force fields [5].

- Energy Minimization: Apply smart minimizer with 2000 steps of steepest descent followed by conjugate gradient algorithms [5].

- Conformer Generation: Generate up to 100 conformers per compound within a 50 kcal/mol energy window using an MMFF94 force field to ensure extended structures are represented [4].

Phase 3: Pharmacophore Model Generation

- Feature Mapping: Identify common pharmacophore features using HypoGen algorithm in Discovery Studio [5].

- Model Construction: Develop pharmacophore hypotheses containing 4-5 features with specific spatial relationships [4].

- Model Selection: Select the best model (Hypo1) based on statistical correlation between estimated and experimental activity (correlation coefficient: 0.917678 for training set) [5].

Phase 4: Model Validation

- Test Set Validation: Validate model with 33 test set compounds (correlation coefficient: 0.874718) [5].

- Fisher Validation: Apply Fisher's randomization test to confirm model robustness [5].

- Cost Analysis: Evaluate hypothesis cost difference between null and generated models [5].

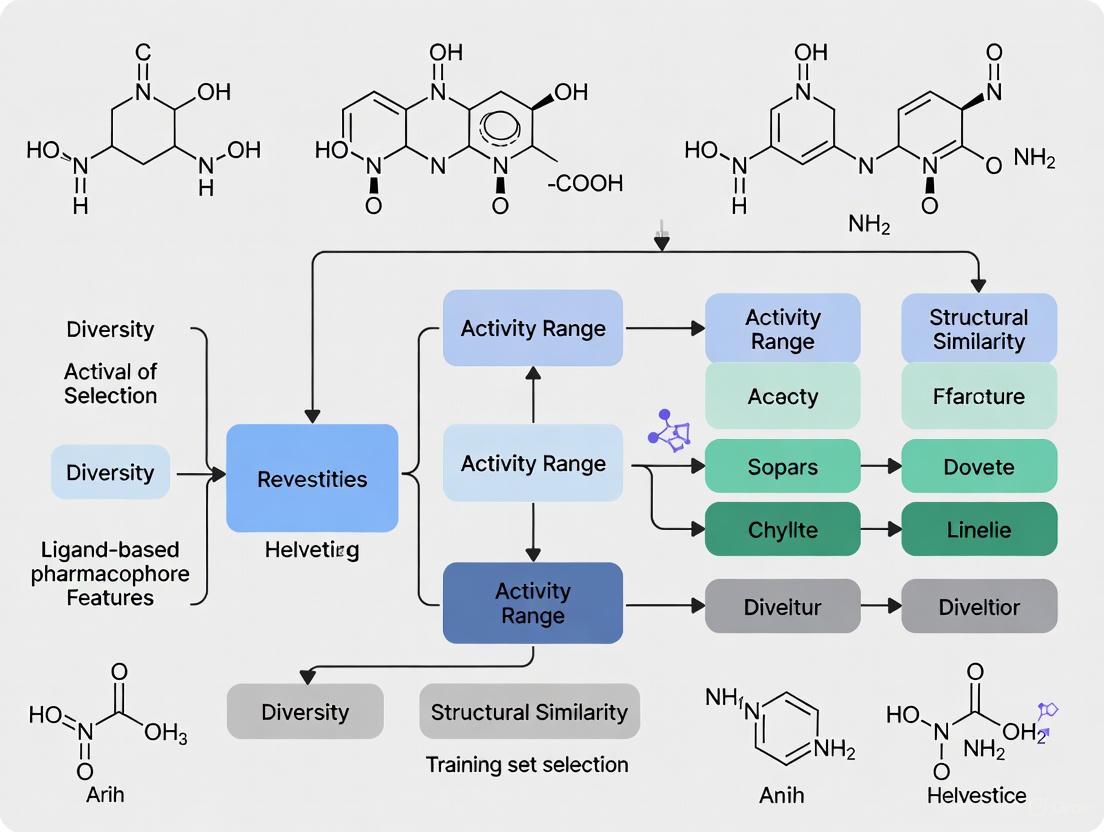

Workflow: Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

Advanced Applications and Recent Advances

FAQ: How can pharmacophore models be applied in virtual screening and what are recent advances?

Virtual Screening Applications:

- Database Filtering: Use validated pharmacophore models as 3D queries to screen large chemical databases (e.g., ZINC database with >1 million compounds) [5] [3].

- Multi-step Screening: Implement sequential filters including Lipinski's Rule of Five, SMART functional group filtration, and activity-based filtration (e.g., estimated activity <1.0 μM) [5].

- Scaffold Hopping: Identify novel chemotypes that share essential interaction features but have different molecular frameworks from known actives [6].

Recent Methodological Advances:

- Multiple Binding Pose Integration: Develop comprehensive pharmacophore maps that incorporate multiple protein-ligand complexes to account for binding pocket flexibility [6] [7].

- Dynamic Pharmacophores: Create models that represent dynamic biological space by incorporating protein flexibility and multiple receptor conformations [6].

- Complex-Based Modeling: Generate pharmacophores from structural data of multiple protein-ligand complexes rather than single structures [8].

- Hybrid Approaches: Combine ligand-based and structure-based methods, particularly for targets with high binding pocket flexibility like nuclear hormone receptors [7].

Table 2: Quantitative Virtual Screening Results from Published Study [5]

| Screening Stage | Number of Compounds | Filtering Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Initial ZINC Database | 1,087,724 | All drug-like molecules |

| After Lipinski's Rule of Five | 312,451 | MW ≤500, ClogP <10, HBD ≤8, HBA ≤10 |

| After SMART Filtration | 98,637 | Remove compounds with undesirable functionalities |

| After Activity Filtration (≤1.0 μM) | 4,218 | Estimated activity based on pharmacophore model |

| After Molecular Docking | 6 | Binding energy and interaction analysis |

| After Toxicity Assessment | 3 | TOPKAT program prediction |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Pharmacophore Modeling

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application in Training Set Selection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discovery Studio | Software Platform | 3D QSAR pharmacophore generation (HypoGen) | Training set compound selection and model validation [5] |

| Phase | Software Module | Pharmacophore perception, 3D QSAR development | Common feature identification and hypothesis generation [1] [6] |

| LigandScout | Software Application | Structure-based and ligand-based pharmacophore modeling | Feature mapping and 3D pharmacophore visualization [8] |

| RDKit | Open-Source Cheminformatics | 2D pharmacophore fingerprint calculation | Compound clustering and diverse representative selection [4] |

| ZINC Database | Compound Library | >1 million commercially available compounds | Virtual screening for novel bioactive molecules [5] |

| CHARMM/MMFF94 | Force Fields | Molecular mechanics energy minimization | Conformational analysis and geometry optimization [5] [4] |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Structural Database | Experimental 3D structures of macromolecules | Structure-based pharmacophore development [8] [3] |

Workflow: Training Set Selection Strategy

The Critical Role of Training Set Composition in Model Accuracy and Generalizability

FAQs: Troubleshooting Training Set Issues in Pharmacophore Modeling

Q1: My pharmacophore model retrieves many inactive compounds during virtual screening. What could be wrong with my training set?

This is typically a issue of specificity. Your training set likely lacks sufficient chemical diversity or does not properly distinguish features essential for binding from those that are not.

- Solution: Re-evaluate your training set composition. Incorporate structurally diverse active compounds and include confirmed inactive compounds in your model validation process. Using a decoy set like DUD-E for validation helps calculate enrichment factors and assess the model's ability to reject inactives [9] [10].

Q2: The generated model fits the training compounds perfectly but fails to identify new active scaffolds. How can I improve its generalizability?

This indicates overfitting. The model has memorized the specific patterns of your training molecules rather than learning the general interaction pattern required for activity.

- Solution: Ensure your training set includes compounds with multiple, distinct chemical scaffolds (scaffold hopping) while maintaining high biological activity. A good training set should represent the "essential features" common across different chemotypes [9] [6]. Avoid using too many highly similar compounds.

Q3: What are the critical data quality requirements for ligands in a training set?

The quality of your input data directly dictates the quality of your pharmacophore model.

- Activity Data: Use only compounds whose activity has been experimentally proven via target-specific assays (e.g., receptor binding or enzyme activity assays on isolated proteins). Avoid data from cell-based assays for model generation, as effects may be influenced by factors like permeability, which confounds the direct structure-activity relationship [9].

- Conformational Sampling: Generate a representative, energy-optimized set of conformations for each training compound to ensure the bioactive conformation is adequately sampled [10].

Experimental Protocols & Best Practices

Protocol for Designing a Robust Training Set

This protocol outlines the steps for assembling a training set for ligand-based pharmacophore generation.

Data Curation and Selection

- Source Data: Collect a set of known active compounds from reliable sources like ChEMBL [9], literature, or in-house databases.

- Activity Criteria: Define a clear activity cut-off (e.g., IC50 < 100 nM) to ensure all selected compounds are potently active [9].

- Structural Diversity: Perform clustering based on molecular fingerprints (e.g., ECFP4) [11] or Bemis-Murcko scaffolds [11] to ensure the set covers multiple chemotypes. Select representative compounds from different clusters.

Conformation Generation

- Software: Use tools like CONFGENX [12] or the Conformation Generation protocol in Discovery Studio [10].

- Parameters: Generate a comprehensive set of conformers using the "Maximum Conformations" method (e.g., 255 conformers) with a reasonable energy threshold (e.g., 20 kcal/mol above the global minimum) [10]. This ensures broad coverage of the conformational space.

Model Generation and Validation

- Hypothesis Generation: Use the generated conformers and the curated active compound set in pharmacophore generation software (e.g., HypoGen in Discovery Studio [13] [10]).

- Validation with Decoys: Validate the initial model using a database containing known active compounds and property-matched decoys (e.g., from DUD-E [9]). Calculate validation metrics like the Güner-Henry (GH) score and Enrichment Factor (EF) [14] [15].

Case Study: Workflow for a Selective CA IX Inhibitor Model

The following diagram illustrates a documented successful implementation of these principles.

Key Steps from the Case Study [14]:

- Training Set: Seven chemically diverse compounds with proven CA IX inhibition and IC50 values below 50 nM were selected.

- Model Generation: Twenty hypotheses were generated in MOE software. The top model,

Ph4.ph4, consisted of four features: two aromatic hydrophobic centers (Aro/Hyd) and two hydrogen bond donor/acceptors (Don/Acc). - Validation: The model was validated against an external decoy set from the DUD-E server, confirming its ability to distinguish active from inactive compounds (high sensitivity and specificity). This validated model was subsequently used for successful virtual screening.

Data Presentation: Composition of Validated Training Sets from Literature

The table below summarizes the composition of training sets from published studies that led to successful pharmacophore models.

| Study / Target | Training Set Size & Composition | Key Diversity Consideration | Validation Outcome & Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Selective CA IX Inhibitors [14] | 7 compounds with IC₅₀ < 50 nM. | Chemically diverse scaffolds selected from literature. | Model validated with DUD-E decoys. Successfully applied in virtual screening to identify novel hits. |

| Akt2 Inhibitors [10] | 23 compounds for 3D-QSAR model. Activity spans 5 orders of magnitude. | Training set activity covers a wide range (5 orders of magnitude). | Model validated by test set (40 compounds) and decoy set. Used to find novel scaffolds from large databases. |

| Topoisomerase I Inhibitors [13] | 29 camptothecin derivatives as training set. | Based on a single scaffold with derivative variations. | The model (Hypo1) was used for virtual screening of over 1 million ZINC compounds, identifying novel potential inhibitors. |

| DiffPhore (General Method) [11] | Two complementary datasets: CpxPhoreSet (15,012 pairs from complexes) & LigPhoreSet (840,288 pairs from diverse ligands). | LigPhoreSet built from 280k representative ligands via scaffold filtering & clustering for maximum chemical diversity [11]. | Used for training a deep learning model. Outperformed traditional tools in binding conformation prediction and virtual screening. |

This table lists key computational tools and data resources critical for training set composition and pharmacophore modeling.

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Training Set Design |

|---|---|---|

| ChEMBL [9] | Database | Public repository of bioactive molecules with curated bioactivity data, used for sourcing potential training set compounds. |

| DUD-E [9] | Database | Directory of Useful Decoys: Enhanced; provides property-matched decoy molecules for rigorous model validation. |

| ZINC [11] [13] | Database | A large database of commercially available compounds, often used as a source for virtual screening and for building diverse ligand sets. |

| RDKit [16] | Software | Open-source cheminformatics toolkit used for fingerprint generation, molecular clustering, and descriptor calculation. |

| MOE (Molecular Operating Environment) [14] | Software | Integrated software for QSAR, pharmacophore modeling, and hypothesis generation. |

| Discovery Studio [13] [10] | Software | Software suite for biomolecular modeling, includes protocols for 3D-QSAR pharmacophore generation (HypoGen) and model validation. |

Strategies for Ensuring Broad Chemical Diversity and Representativeness

Core Concepts and Importance

Why is ensuring chemical diversity in a training set critical for pharmacophore modeling?

A training set with broad chemical diversity is fundamental to developing a robust and predictive pharmacophore model. A diverse set of active ligands helps ensure the resulting model captures the essential, shared chemical features responsible for biological activity, rather than overfitting to the specific structural motifs of a narrow compound series [4]. This improves the model's ability to identify novel active chemotypes through virtual screening, a process known as scaffold hopping [17].

Conversely, a training set with limited diversity can lead to a pharmacophore hypothesis that is too specific, causing you to miss potent compounds with different structural backbones during virtual screening [18]. Comprehensive diversity analysis typically employs multiple molecular representations—such as molecular scaffolds, structural fingerprints, and physicochemical properties—to provide a complete picture of the "global diversity" of a compound library [19].

Practical Implementation Strategies

What are the primary strategies for selecting a diverse training set?

Two main strategies for training set selection are used, depending on the assumptions about the binding modes of the active compounds.

Table 1: Training Set Selection Strategies

| Strategy | Assumption | Methodology | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strategy I: Single Binding Mode [4] | All active compounds share the same binding mode. | - Cluster active and inactive compounds separately using 2D pharmacophore fingerprints. [4]- Select cluster centroids to represent the chemical space of both actives and inactives. | Congeneric series of ligands with a common core structure. |

| Strategy II: Multiple Binding Modes [4] | Active compounds may have different binding modes. | - Cluster active and inactive compounds jointly. [4]- From each cluster, randomly select active and inactive compounds for the training set.- Create multiple training sets to account for binding mode variability. | Diverse ligand sets with potentially different binding orientations or for targets with multiple binding pockets. |

How do I measure and analyze the chemical diversity of my compound set?

You should assess diversity using multiple, complementary metrics to get a holistic view. The Consensus Diversity Plot (CDP) is a novel method that visualizes global diversity by combining several criteria into a single, two-dimensional graph [19].

Table 2: Key Metrics for Assessing Chemical Diversity

| Representation | Metric | Description | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Scaffolds [19] | Cyclic System Recovery (CSR) Curves | Plots the cumulative fraction of compounds recovered against the fraction of scaffolds used. | A steeper curve indicates lower diversity (few scaffolds account for many compounds). |

| Area Under the Curve (AUC) / F50 | AUC of the CSR curve; F50 is the fraction of scaffolds needed to recover 50% of the database. | Low AUC or High F50 indicates high scaffold diversity. [19] | |

| Scaled Shannon Entropy (SSE) | Measures the uniformity of compound distribution across different scaffolds. | Ranges from 0 (min diversity) to 1 (max diversity). [19] | |

| Structural Fingerprints [19] | Tanimoto Similarity | Calculates pairwise molecular similarity using fingerprints like MACCS keys or ECFP_4. | A lower average pairwise similarity indicates higher diversity in the overall molecular structure. |

| Physicochemical Properties [19] | Euclidean Distance in Property Space | Measures distance between compounds based on properties like Molecular Weight, logP, HBD, HBA, etc. | A wider spread of compounds in this space indicates greater diversity in drug-like properties. |

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for selecting a training set and assessing its diversity, integrating the strategies and metrics outlined above:

Troubleshooting Common Issues

What should I do if my pharmacophore model is too specific and fails to find novel scaffolds?

This is a classic sign of a training set with insufficient chemical diversity.

- Problem: The model is overfitting to specific chemical structures present in the training actives.

- Solution:

- Re-evaluate Your Training Set: Use a CDP or the metrics in Table 2 to check the scaffold and fingerprint diversity of your actives. If the AUC is high and F50 is low, your set is likely dominated by a few common scaffolds [19].

- Incorporate Structurally Diverse Actives: Seek out active compounds with different molecular frameworks from the literature or databases to broaden the chemical space represented in your training set.

- Use a Generative Model: Consider using pharmacophore-informed generative models like TransPharmer. These models can use the pharmacophore fingerprints of your actives to generate novel, structurally distinct compounds that still possess the necessary pharmacophoric features, effectively performing in silico scaffold hopping [17].

How can I avoid artificial enrichment and ensure my model distinguishes true actives from decoys?

This involves careful selection of both active and inactive compounds in your training set.

- Problem: The model appears to perform well in validation but fails in real-world screening because it is not specific enough.

- Solution:

- Use Challenging Decoys: When building your training set, include inactive compounds or decoys that are physiochemically similar to your actives but topologically different. Databases like DUD-E (Database of Useful Decoys: Enhanced) are designed for this purpose, providing decoys with similar 1D properties but different 2D topology, which helps avoid artificial enrichment during screening [20].

- Strategic Inactive Selection: When applying Training Set Strategy II, ensure that inactive compounds from joint clustering are included to better represent the chemical space of inactives and improve the model's precision [4].

Table 3: Key Software and Resources for Diversity Analysis and Pharmacophore Modeling

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function in Diversity/Pharmacophore Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| Schrödinger Phase [20] | Commercial Software Suite | Develop pharmacophore hypotheses from ligand sets; create Phase databases for virtual screening. |

| RDKit [4] | Open-Source Cheminformatics | Calculate 2D pharmacophore fingerprints; generate molecular conformers; perform clustering. |

| Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) [19] | Commercial Software Suite | Curate compound data; calculate physicochemical properties (HBD, HBA, logP, MW). |

| MEQI (Molecular Equivalent Indices) [19] | Software Tool | Conduct scaffold diversity analysis by deriving and naming molecular chemotypes. |

| MayaChemTools [19] | Open-Source Toolkit | Calculate structural fingerprints (e.g., MACCS keys) for pairwise diversity analysis. |

| ZINCPharmer [21] | Online Database/Tool | Perform pharmacophore-based virtual screening of the ZINC compound database. |

| DUD-E [20] | Database | Access decoy molecules for rigorous validation of virtual screening methods. |

Balancing Active and Inactive Compounds to Enhance Model Selectivity

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why is it critical to include inactive compounds in my training set for pharmacophore modeling?

Including inactive compounds, or decoys, is essential for validating the selectivity of your pharmacophore model. A model developed only from active compounds might identify common chemical features but cannot distinguish whether these features are truly responsible for biological activity or are merely common to the chemical scaffold. Using a set of confirmed inactive compounds or property-matched decoys during validation allows you to test and refine your model to discriminate between binders and non-binders, thereby enhancing its predictive accuracy and reducing false positives in virtual screening [22].

FAQ 2: What are the best sources for obtaining reliable decoy compounds?

Two highly recognized sources for decoy compounds are:

- DUD-E (Directory of Useful Decoys: Enhanced): This is a widely used database specifically designed for benchmarking virtual screening methods. It contains a large collection of decoys that are chemically similar but topologically different from active ligands, ensuring they are physically plausible but chemically distinct [23] [22] [12].

- ZINC Database: A curated collection of commercially available chemical compounds. It can be used to select decoys or to screen for new potential hits after you have built and validated your model [21] [22].

FAQ 3: How can I quantitatively measure the selectivity of my pharmacophore model?

The selectivity and performance of a pharmacophore model are quantitatively assessed using specific metrics derived from validation tests. Key metrics include the Enrichment Factor (EF) and the Area Under the Curve (AUC) of a Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve [23] [22].

- Enrichment Factor (EF): Measures how much more likely you are to find active compounds at the top of a ranked list compared to a random selection. A higher EF indicates better model performance [23].

- Area Under the Curve (AUC): The AUC value summarizes the model's ability to distinguish between active and inactive compounds. An AUC value of 1.0 represents a perfect model, while 0.5 represents a model with no discriminative power. An excellent model should have an AUC value close to 1.0 [22].

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics for Pharmacophore Model Validation

| Metric | Description | Ideal Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enrichment Factor (EF) | The concentration of active compounds found in a top fraction of the screening hits versus a random distribution [23]. | >1 (Higher is better) | Measures the model's efficiency in enriching true hits. |

| Area Under the Curve (AUC) | The area under the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve, which plots the true positive rate against the false positive rate [22]. | 1.0 (Perfect classifier) | Evaluates the model's overall ability to discriminate actives from inactives. |

FAQ 4: My model has high sensitivity but poor specificity. What could be the cause and how can I fix it?

This issue often arises when a model is over-fitted. It means the model is too specifically tuned to the exact features and conformations of your training actives, so it fails to recognize other legitimate active chemotypes and misclassifies many inactives as hits.

- Cause: Using a training set that is too small or lacks sufficient chemical diversity among the active compounds.

- Solution:

- Increase Diversity: Incorporate active compounds with different chemical scaffolds that are known to bind the same target [3].

- Feature Refinement: Re-evaluate the pharmacophore features. You may have included non-essential features. Try to identify and retain only the features that are critical for binding, often by analyzing the receptor-ligand complex if structural data is available [3] [24].

- Use Exclusion Volumes: Incorporate exclusion volumes (also known as forbidden volumes) into the model to represent steric hindrance in the binding pocket, which helps rule out compounds that would clash with the receptor [3] [11].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Enrichment Factor during Virtual Screening Your model retrieves many compounds, but the hit rate of true actives is not significantly better than random selection.

Potential Cause 1: Non-discriminative Pharmacophore Features The defined features (e.g., hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic areas) are too common and do not represent the unique characteristics required for binding.

Potential Cause 2: Improperly Matched Decoy Set The decoys used for validation are not well-matched to the actives, making separation trivial or impossible.

Potential Cause 3: Inadequate Model Validation The model was not rigorously tested before application.

- Solution: Always run an internal validation using a test set with known actives and inactives. Calculate the EF and AUC metrics to objectively assess the model's performance before proceeding to screen large, unknown databases [22].

Problem: Model Fails to Identify Known Active Compounds The model is too restrictive and misses compounds that are confirmed to be active.

Potential Cause 1: Overly Rigid Conformational Sampling The model does not account for the flexibility of the ligand or the necessary tolerance in feature positioning.

- Solution: Increase the conformational flexibility allowed during the screening process. Ensure the energy threshold for generated conformers is sufficient to cover potential bioactive conformations [24].

Potential Cause 2: Missing Key Pharmacophore Features The model may be lacking a critical feature that is present in the missed active compounds.

- Solution: Revisit your set of active ligands. Look for common features that were initially overlooked. Using a larger and more diverse set of active compounds for model generation can help capture all essential features [25].

Potential Cause 3: Excessive Exclusion Volumes The use of exclusion volumes might be too extensive, sterically blocking valid active compounds from fitting the model.

- Solution: Re-evaluate the placement and radius of exclusion volumes based on the 3D structure of the binding pocket. Consider using a softer scoring function for steric clashes [12].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Validating a Pharmacophore Model Using a Decoy Set

This protocol outlines the steps to assess the selectivity and predictive power of your pharmacophore model.

- Obtain a Validation Set: Compile a set of known active compounds and a set of decoy compounds (e.g., from DUD-E) [22].

- Combine and Screen: Merge the active and decoy sets into a single database. Screen this database against your pharmacophore model.

- Rank Results: Rank the screening results based on the "fit value" or how well each compound matches the model.

- Generate ROC Curve: Plot a ROC curve with the True Positive Rate (fraction of found actives) against the False Positive Rate (fraction of found decoys) across the ranked list [22].

- Calculate Metrics:

- Interpret Results: A high AUC and EF indicate a model that can successfully distinguish active from inactive compounds.

The following workflow visualizes the key steps in the pharmacophore model validation process:

Protocol 2: Building a Selective Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Model

This methodology is adapted from successful studies that identified novel inhibitors [21] [25].

- Curation of Active Ligands: Collect a set of 5-10 known active ligands with potent activity (e.g., IC50 < 50 nM). It is crucial that these ligands are structurally diverse to avoid bias and to ensure the model captures essential features and not just a single scaffold [21] [25].

- Conformational Analysis: Generate multiple low-energy conformations for each active ligand to account for flexibility.

- Pharmacophore Generation: Use software like

MOEorPharmaGistto generate multiple pharmacophore hypotheses by aligning the active conformers and identifying common steric and electronic features [23] [25]. - Hypothesis Scoring: Select the top-ranked hypothesis based on the software's scoring algorithm, which often considers the alignment of features and the volume overlap of the ligands.

- Validation with Inactives: Test the selected hypothesis using the validation protocol described above (Protocol 1) before proceeding to virtual screening.

Table 2: Checklist for Building a Selective Training Set

| Step | Action | Best Practice Tip |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Select Actives | Choose compounds with confirmed high potency. | Aim for chemical and scaffold diversity, not just high potency [25]. |

| 2. Select Inactives | Choose property-matched decoys. | Use established databases like DUD-E to ensure decoys are matched on molecular weight, logP, etc., but are topologically distinct [22]. |

| 3. Model Generation | Generate multiple hypotheses from actives. | Use a sufficient number of active compounds (e.g., 7-10) to capture core features without over-complicating the model [25]. |

| 4. Model Validation | Test the model with the active/inactive set. | Use quantitative metrics (AUC, EF) for an objective assessment. Do not proceed to screening without this step [22]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for Pharmacophore Modeling and Validation

| Tool / Reagent | Function | Example Use in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| DUD-E Database | A database of useful decoys for benchmarking virtual screening. | Serves as a source of rigorously matched inactive compounds for validating model selectivity [22] [12]. |

| ZINC Database | A public resource of commercially available compounds for virtual screening. | Used as a compound library for virtual screening after a validated pharmacophore model is obtained [21]. |

| MOE (Molecular Operating Environment) | A comprehensive software suite for molecular modeling. | Used for ligand-based pharmacophore generation, hypothesis scoring, and database searching [25]. |

| LigandScout | Software for structure- and ligand-based pharmacophore modeling. | Used to create structure-based pharmacophores from protein-ligand complexes and to perform advanced virtual screening [23] [22]. |

| ROC Curve Analysis | A graphical plot for evaluating classifier performance. | The primary method for visualizing and quantifying a model's ability to discriminate between active and inactive compounds [22]. |

Sourcing High-Quality Bioactivity Data from Public Databases (ChEMBL, PubChem)

In ligand-based pharmacophore modeling, the quality of your training set dictates the success of your entire research endeavor. Pharmacophores serve as abstractions of essential chemical interaction patterns, holding an irreplaceable position in drug discovery [26] [11]. These models rely on accurate bioactivity data and compound structures to identify the spatial arrangement of molecular features responsible for biological activity. The foundational principle is simple yet powerful: compounds sharing similar activity against a biological target likely share common pharmacophoric elements. However, this principle collapses when built upon unreliable data, leading to models that cannot distinguish true actives from inactives or accurately predict new lead compounds.

Public databases like ChEMBL and PubChem contain immense volumes of bioactivity data, but this data varies significantly in quality, consistency, and applicability. The challenge for researchers is not merely accessing this data, but implementing robust methodologies to curate high-quality training sets specifically optimized for pharmacophore development. This technical support center addresses the most critical issues researchers encounter during this process and provides proven solutions to ensure your pharmacophore models stand on a foundation of rigorously validated data.

Database Fundamentals: ChEMBL and PubChem Compared

Key Characteristics and Applications

Table 1: Comparison of Major Bioactivity Databases

| Feature | ChEMBL | PubChem |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Manually curated bioactive molecules with drug-like properties [27] | Largest repository of bioactivity data from high-throughput screens [28] |

| Data Curation | Extensive manual curation with standardized data ontologies [27] [29] | Automated processing with varying levels of curation |

| Bioactivity Types | IC₅₀, Ki, EC₅₀, etc., with standardized units and relationships [30] | Diverse assay results including inhibition, activation, and phenotypic outcomes [28] |

| Target Coverage | Comprehensive protein target annotation with ChEMBL IDs [30] | Broad target coverage including gene-based assays |

| Best Applications | Lead optimization, target fishing, structured QSAR studies [26] [30] | Virtual screening, hit identification, chemical biology exploration [28] |

Data Quality Framework for Pharmacophore Modeling

The following diagram illustrates the critical pathway for transforming raw database records into a curated training set suitable for pharmacophore modeling:

Diagram 1: Data curation workflow for pharmacophore research.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Data Extraction and Query Issues

Q1: My SQL query on the local ChEMBL database is running extremely slowly when retrieving activity data for specific target classes. How can I optimize performance?

A: Implement targeted query optimization with proper indexing and query structure:

- Use Appropriate Joins: Ensure you're using efficient JOIN structures with properly indexed columns. The

molregnofield is typically well-indexed and should be used for joining tables [30]. - Filter Early: Apply filters as early as possible in your query to reduce the dataset size before complex operations.

- Leverage Local Installation: For large-scale analyses, a local installation of the ChEMBL SQL database significantly improves performance compared to web services [31].

Example Optimized Query:

Q2: I'm unable to retrieve consistent bioactivity data from PubChem for a specific assay (AID). The results seem incomplete or poorly standardized. What validation steps should I implement?

A: PubChem data requires rigorous standardization due to variations in experimental protocols and reporting formats [28]:

- Batch Processing: Use the PUG-REST API with appropriate batching to avoid retrieval limits and ensure complete data downloads [28].

- Outcome Interpretation: Carefully interpret the 'Outcome' field (1: Inactive, 2: Active, 3: Inconclusive, 4: Unspecified, 5: Probe) and filter accordingly [28].

- Unit Standardization: Pay close attention to measurement unit codes (e.g., 5: µM, 6: nM) and convert all values to consistent units before analysis [28].

- Cross-Validation: When possible, validate key findings against ChEMBL data for the same compounds and targets.

Data Standardization and Curation Challenges

Q3: How should I handle salts, mixtures, and stereochemistry when extracting compounds from ChEMBL for pharmacophore modeling?

A: Implement a multi-step standardization protocol:

- Parent Compound Identification: Use the

molecule_hierarchytable to identify parent compounds and avoid counting salts as distinct molecules [30]. - Stereochemistry Awareness: Preserve stereochemical information when available, as it critically impacts pharmacophore feature geometry.

- Salt Stripping: Remove counterions and salts to focus on the active pharmaceutical ingredient while documenting the original structure for reproducibility.

Example Salt Handling Query:

Q4: What criteria should I use to select high-confidence activity data from public databases for pharmacophore training sets?

A: Establish rigorous inclusion criteria based on measurement quality and experimental context:

- Measurement Type Preference: Prioritize direct binding measurements (Ki, IC₅₀) over functional assays (EC₅₀) for pharmacophore modeling [30].

- Relationship Filtering: Include only activities with

standard_relation = '='to avoid inequality relationships that complicate modeling [30]. - Unit Consistency: Convert all activity values to consistent units (nM recommended) before analysis.

- Threshold Application: Implement activity thresholds relevant to your research context (e.g., < 1 µM for actives, > 10 µM for inactives).

- Assay Validation: Prefer assays with clear experimental descriptions and appropriate controls.

Pharmacophore-Specific Data Preparation

Q5: How many compounds and what activity range should I include in a training set for robust pharmacophore model generation?

A: The optimal training set balances quantity, quality, and diversity:

- Compound Count: Include 20-50 well-curated compounds with measured activities spanning at least 3 orders of magnitude (e.g., 1 nM to 1 µM) [21].

- Structural Diversity: Ensure chemical diversity while maintaining common pharmacophoric features; include multiple scaffold classes when possible.

- Activity Spread: Include both high-affinity and low-affinity compounds to help distinguish essential features from optional ones.

- Reference Studies: In successful implementations like fluoroquinolone antibiotic pharmacophore modeling, researchers used 4 known antibiotics to generate a shared feature pharmacophore map, then validated against 25 hit compounds from virtual screening [21].

Q6: What molecular features should I prioritize when annotating compounds for pharmacophore modeling, and how can I extract this information efficiently?

A: Focus on chemically meaningful interaction features that directly participate in target binding:

- Core Feature Types: Hydrogen-bond donors (HBD), hydrogen-bond acceptors (HBA), hydrophobic areas (HYD), aromatic rings (AR), charged centers (POS/NEG), and specific features like halogen bond donors [26] [11].

- Automated Annotation: Use tools like RDKit or OpenBabel to automatically detect and annotate these features from compound structures.

- Directional Features: For features like HBD and HBA, capture directional preferences when possible, as these significantly impact pharmacophore quality [26].

- Exclusion Volumes: Incorporate exclusion spheres to represent steric constraints from the protein binding pocket [26] [11].

Experimental Protocols for Training Set Curation

Comprehensive Protocol for ChEMBL Data Extraction

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Data Curation

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| ChEMBL SQL Database | Local installation for fast, complex queries | Large-scale compound retrieval and filtering [31] |

| PSYCOPG2 Python Package | PostgreSQL interface for programmatic data access | Automated data curation workflows [31] |

| RDKit | Cheminformatics toolkit for molecular standardization | Structure normalization, feature detection, and validation |

| PUG-REST API | Programmatic access to PubChem data | Batch downloading and assay data retrieval [28] |

| Pharmacophore Tools (AncPhore, PHASE) | Pharmacophore feature identification and modeling | Training set validation and feature annotation [26] |

Protocol 1: Building a Target-Focused Training Set from ChEMBL

Target Identification

- Identify your target of interest and its ChEMBL ID (e.g., 'CHEMBL1827' for human PDE5) [30]

- Confirm target specificity by reviewing related targets to avoid cross-reactive compounds

Bioactivity Data Retrieval

- Execute a structured SQL query to extract compounds with specific activity types:

- Execute a structured SQL query to extract compounds with specific activity types:

Data Standardization

- Convert all activity values to nM concentrations

- Apply pCHEMBL transformation: pCHEMBL = -log10(standard_value × 10⁻⁹)

- Remove duplicates, keeping the highest quality measurement for each compound

- Standardize structures: neutralize charges, remove salts, generate canonical tautomers

Activity Thresholding

- Classify compounds as actives (< 100 nM), moderately active (100 nM - 1 µM), or inactive (> 1 µM)

- Ensure adequate representation across activity ranges for continuous pharmacophore modeling

Chemical Diversity Analysis

- Apply Bemis-Murcko scaffold analysis to identify core structures

- Ensure coverage of multiple scaffold classes while maintaining common pharmacophoric features

- Use fingerprint similarity (ECFP4) to quantify diversity [26]

Advanced Protocol: Selective Compound Extraction

Protocol 2: Retrieving Compounds Selective for One Target Over Another

This protocol is valuable for building pharmacophore models with enhanced specificity:

Define Selectivity Criteria

- Establish selectivity ratio (e.g., >10-fold preference for primary target)

- Set absolute potency thresholds for both targets

Execute Selective Query

Validate Selectivity Profile

- Cross-reference with additional bioactivity sources

- Confirm selectivity through literature validation

- Apply additional filters based on assay confidence levels

The workflow below illustrates the strategic approach to building a selective training set:

Diagram 2: Selective training set development workflow.

Case Study: Successful Implementation in Pharmacophore Research

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling for Fluoroquinolone Antibiotics

A recent study demonstrates proper training set selection for identifying potential antimicrobial compounds [21]:

- Training Set Composition: Researchers used four known antibiotics (Ciprofloxacin, Delafloxacin, Levofloxacin, and Ofloxacin) to generate a shared feature pharmacophore (SFP) map.

- Feature Identification: The model identified critical pharmacophore features including hydrophobic areas, hydrogen bond acceptors (HBA), hydrogen bond donors (HBD), and aromatic moieties (Ar).

- Virtual Screening: The pharmacophore model screened 160,000 compounds from ZINCPharmer, identifying 25 potential hits with fit scores ranging from 97.85 to 116 and RMSD values from 0.28 to 0.63.

- Experimental Validation: The top five compounds achieved docking scores comparable to ciprofloxacin (-7.3 to -7.4 kcal/mol vs -7.3 kcal/mol for control), with one emerging as a promising lead after drug-likeness evaluation.

This case study highlights how a focused, well-curated training set of only four high-quality compounds can generate effective pharmacophore models for successful virtual screening.

Sourcing high-quality bioactivity data from public databases requires meticulous attention to data extraction, standardization, and validation protocols. By implementing the troubleshooting guides, experimental protocols, and quality control measures outlined in this technical support center, researchers can build robust training sets that significantly enhance the predictive power of ligand-based pharmacophore models. Remember that the time invested in rigorous data curation invariably returns dividends in model quality and research outcomes, particularly in the critical early stages of drug discovery projects where pharmacophore models guide lead identification and optimization efforts.

From Data to Model: A Step-by-Step Protocol for Training Set Curation and Model Generation

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What are the primary criteria for selecting compounds for a pharmacophore model training set? The primary criteria are potency, structural diversity, and data confidence. The training set should include compounds with a wide range of experimentally determined biological activities (e.g., IC50 values), ensuring coverage from highly active to inactive molecules. Furthermore, the selected compounds should represent diverse chemical scaffolds and substitution patterns to prevent model bias and ensure it captures the essential features for binding, not just a single chemical structure. [5] [32]

Q2: How should I categorize compounds based on potency? A common and effective strategy is to categorize compounds into different activity levels according to their IC50 values. For instance:

- Most Active: IC50 < 0.1 μM

- Active: IC50 between 0.1 μM and 1.0 μM

- Moderately Active: IC50 between 1.0 μM and 10.0 μM

- Inactive: IC50 > 10.0 μM Your training set should ideally contain a maximum number of the most active and active compounds, supplemented with a few moderately active and inactive compounds to define the model's boundaries. [5]

Q3: Can I mix agonists and antagonists in the same training set? Yes. Research indicates that pharmacophore models constructed from ligands of mixed functions (e.g., agonists and antagonists) are still capable of enriching hit lists with active compounds. This approach is particularly valuable when the number of known ligands for a target is limited. However, if the goal is to discover compounds with a specific biological function, a function-specific training set is recommended. [32]

Q4: Why is my pharmacophore model performing poorly despite having high-fit compounds? This often stems from a lack of structural diversity in the training set. If all training set compounds share a similar core scaffold, the model may overfit to that specific chemical structure and fail to identify novel chemotypes. Ensure your training set includes molecules with different structural frameworks that all exhibit the desired biological activity. [32] [25]

Q5: How does assay variability impact my training set selection? Assay variability is a critical source of uncertainty in potency data. High variability can obscure true structure-activity relationships and lead to misclassification of compounds. To mitigate this, prioritize data from robust, well-controlled assays and consider the confidence intervals of potency measurements when selecting compounds for your training set. [33]

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Pharmacophore model fails to identify any active compounds during virtual screening.

- Cause 1: Overly restrictive model. The model may have been generated from a training set with insufficient structural diversity.

- Solution: Re-evaluate your training set. Incorporate compounds from multiple analogue series or chemotypes that are known to be active. A study on GPCRs recommends using a diverse training set over one based solely on high potency. [32]

- Cause 2: Incorrect potency data. The experimental biological activities used for training may be unreliable or sourced from inconsistent assay conditions.

- Solution: Curate your data meticulously. Use potency values generated from a homogeneous procedure (e.g., the same biological assay and cell line) to ensure consistency. [5]

Problem: Model retrieves active compounds but also an excessively high number of false positives.

- Cause: Lack of inactive or moderately active compounds. The model has not learned what features or spatial arrangements are not conducive to binding.

- Solution: Include carefully selected inactive or weakly active compounds in your training set. This helps the algorithm distinguish between essential and non-essential features, improving model specificity. [5]

Problem: Model performs well on the training set but poorly on new, external test compounds.

- Cause: Data leakage or overfitting. The test set may be too similar to the training set, or the model may be too complex.

Experimental Protocols & Data

Table 1: Quantitative Potency Categorization Scheme for Training Set Selection

| Activity Level | IC50 Range | Recommended Proportion in Training Set |

|---|---|---|

| Most Active | < 0.1 μM | Maximize number |

| Active | 0.1 - 1.0 μM | Include a significant number |

| Moderally Active | 1.0 - 10.0 μM | Include a few representatives |

| Inactive | > 10.0 μM | Include a few for contrast |

Source: Adapted from a study on Topoisomerase I inhibitors [5]

Detailed Methodology: Construction of a Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Model

Data Curation and Training Set Selection:

- Collect a set of known active compounds against your target of interest.

- Obtain consistent biological activity data (e.g., IC50, Ki) from a uniform assay condition. [5]

- Categorize compounds based on potency as shown in Table 1.

- Select a training set of 20-30 compounds that spans the potency range and encompasses diverse chemical structures and substituents. [5] [25]

Compound Preparation:

- Draw 2D structures and convert them into 3D formats using software like ChemDraw or MOE.

- Minimize molecular energy using a force field (e.g., CHARMM) to obtain stable 3D conformations. [5]

Pharmacophore Generation (using HypoGen algorithm in Discovery Studio as an example):

- Input the prepared training set molecules and their experimental activity values.

- The algorithm will generate multiple pharmacophore hypotheses (e.g., Hypo1, Hypo2...). These hypotheses comprise 3D arrangements of chemical features like hydrogen bond acceptors/donors (HBA/HBD), hydrophobic regions (H), and aromatic rings (AR). [5] [3]

Model Validation:

- Internal Validation: Use a test set of molecules (not used in training) to check the correlation between estimated and experimental activity. [5]

- External Decoy Set Validation: Test the model's ability to retrieve active compounds from a database spiked with known actives and decoys, calculating enrichment factors. [32] [25]

The workflow for this methodology is summarized in the following diagram:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Software for Pharmacophore Modeling

| Item | Function in Research | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) | Software suite for pharmacophore feature generation, model building, and validation. [32] [25] | Used to develop and validate a pharmacophore model for carbonic anhydrase IX inhibitors. [25] |

| Discovery Studio (DS) | Software platform providing HypoGen algorithm for 3D QSAR pharmacophore generation. [5] | Employed to build a pharmacophore model for Topoisomerase I inhibitors from 29 CPT derivatives. [5] |

| ZINC Database | A freely available public database of commercially available compounds for virtual screening. [5] [21] | Used as a source of over 1 million drug-like molecules for virtual screening with a validated pharmacophore query. [5] |

| CHEMBL | A manually curated database of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties, providing reliable potency data. [34] | Sourced as a repository of compounds with documented potency for building and testing predictive models. [34] |

| Four-Parameter Logistic (4PL) Fit | A statistical model used to analyze dose-response data from bioassays to derive accurate potency values (e.g., IC50, EC50). [33] | Fundamental for calculating the relative potency (%RP) of test samples against a reference standard in potency assays. [33] |

Visualizing Potency Data Considerations

Understanding the distribution and confidence of your potency data is crucial for selecting a reliable training set. The following diagram illustrates the relationship between assay variability and the confidence in a compound's potency measurement, which directly impacts data confidence.

The Role of Inactive or Decoy Molecules in Defining Pharmacophore Specificity

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is it important to include inactive compounds in a pharmacophore training set? Inactive compounds are crucial for defining the specificity of a pharmacophore model. A model developed using only active compounds might identify common chemical features but cannot distinguish which of these features are truly essential for binding versus those that are merely common to the molecular scaffold. By including inactive compounds, the model can be refined to eliminate features that are also present in non-binders, thereby reducing false positives during virtual screening and increasing the model's predictive accuracy [35] [36].

Q2: What is the difference between an inactive compound and a decoy molecule?

- Inactive Compound: A known chemical entity that has been experimentally tested against the biological target and found to lack significant activity (e.g., high IC50 value) [35] [10]. These are used during the training phase of model generation to help identify and discard non-essential pharmacophore features.

- Decoy Molecule: A compound, typically with unknown activity, used during the validation phase to test the model's ability to discriminate between potential actives and inactives. A decoy set usually contains a large number of molecules presumed to be inactive, spiked with a few known active compounds [10].

Q3: How many inactive compounds should be included in a training set? While the ideal number depends on the project, a general guideline is to include 15-20 compounds in the training set, comprising a mix of highly potent, intermediately potent, and inactive molecules [36]. For the HypoGen algorithm, the use of inactive compounds is a built-in part of its methodology for refining the pharmacophore hypothesis [35].

Q4: What are the consequences of using a training set that lacks inactive molecules? A training set without inactive molecules is likely to generate a pharmacophore model with lower specificity. This can lead to:

- Higher False Positive Rates: The model may retrieve a large number of compounds from databases that match the pharmacophore but are biologically inactive [35].

- Reduced Scaffold Hopping Utility: The model may be overly specific to the chemical scaffolds of the training set actives, missing truly novel chemotypes with the same biological function [35].

Q5: Which is more critical for pharmacophore model validation: specificity or sensitivity? The primary goal during validation should be specificity [36]. While a good model should identify true actives (sensitivity), its practical utility in virtual screening is more dependent on its ability to reject inactive compounds, as this dramatically reduces the cost and time of subsequent experimental testing.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Pharmacophore Model Retrieves Too Many False Positives

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause 1: Lack of Inactive Compounds in Training.

- Solution: Refine the initial model by incorporating a set of known inactive compounds. Software like Catalyst's HypoGen algorithm is explicitly designed for this; it uses inactive compounds to eliminate pharmacophore features that are common to the inactive set, thus refining the hypothesis [35].

Cause 2: Overly General Feature Definitions.

- Solution: Make the pharmacophore feature definitions more specific. For example, instead of a general "hydrogen bond acceptor," define a more specific vector or location based on the binding site geometry. You can also add exclusion volumes to represent steric clashes in the binding site, which helps rule out molecules that are too bulky [3].

Cause 3: Inadequate Validation with a Decoy Set.

- Solution: Always validate your model using a decoy set validation method. This involves screening a database containing known actives and many decoy molecules. Calculate the Enrichment Factor (EF) to quantitatively measure how much better your model performs than a random selection [10].

Problem: Model Fails to Identify Structurally Novel Active Compounds (Poor Scaffold Hopping)

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause 1: Training Set Lacks Chemical Diversity.

- Solution: Ensure your training set of active compounds is structurally diverse. Use clustering techniques (e.g., Butina clustering based on 2D pharmacophore fingerprints) to select representative molecules from different chemical classes [4]. A diverse training set helps create a pharmacophore that captures the essential functional features, independent of a specific scaffold.

Cause 2: Model is Over-fitted to a Single Scaffold.

- Solution: Analyze the model against a test set containing active compounds with different scaffolds. If it fails, re-generate the model using a more diverse training set and check if the inclusion of inactives has made the model too restrictive. The goal is a balance that captures essential features without being tied to a specific core structure [35].

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Protocol 1: Generating a Ligand-Based Pharmacophore with Inactive Compounds

This protocol outlines the workflow for creating a pharmacophore model using both active and inactive ligands.

1. Training Set Preparation:

- Data Collection: Gather a set of 15-20 molecules with experimentally determined activities (e.g., IC50). The set should include highly active, moderately active, and confirmed inactive compounds [36].

- Conformational Analysis: For each molecule, generate a set of low-energy conformers to represent its accessible conformational space. Common settings use an energy threshold of 20 kcal/mol above the global minimum to ensure the bioactive conformation is likely included [4].

2. Model Generation (e.g., using HypoGen in Discovery Studio):

- The algorithm first identifies common feature arrangements from the active compounds (similar to the Hip-Hop algorithm) [35].

- It then compares the best pharmacophore hypotheses from the first stage with the conformers of the inactive compounds.

- Features that are common to the inactive set are eliminated or penalized.

- The algorithm proceeds with an optimization cycle, scoring the refined hypotheses based on their ability to predict the experimental activities of all training set compounds [35].

3. Model Validation:

- Test Set: Use a set of known active and inactive compounds not used in training to test the model's predictive power.

- Decoy Set Validation: Prepare a database of 2000 molecules, spiking in 20 known Akt2 inhibitors among 1980 decoys. Screen this database with your pharmacophore model and calculate the Enrichment Factor (EF) to assess performance [10].

The following diagram illustrates this ligand-based workflow:

Quantitative Metrics for Model Validation

The table below summarizes key metrics used to validate a pharmacophore model's performance, particularly its specificity.

Table 1: Key Metrics for Pharmacophore Model Validation

| Metric | Formula / Description | Interpretation | Application in Search Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enrichment Factor (EF) | EF = (Hitssampled / Nsampled) / (Hitstotal / Ntotal) [10] | Measures how much better the model is at finding actives compared to random selection. A higher EF indicates better performance. | Used to validate a structure-based pharmacophore for Akt2 inhibitors [10]. |

| Recall (True Positive Rate) | Recall = TP / (TP + FN) [4] | The fraction of true active compounds correctly identified by the model. | A key metric for internal and external performance estimation [4]. |

| Specificity (True Negative Rate) | Specificity = TN / (TN + FP) [36] | The fraction of true inactive compounds correctly rejected by the model. Highlighted as the primary goal for validation [36]. | |

| F-Score | Fβ = (1+β²) * (Precision * Recall) / (β² * Precision + Recall) [4] | A weighted harmonic mean of precision and recall. F0.5 weights precision higher, favoring specificity. | Used as a selection criterion during automated pharmacophore model generation [4]. |

Protocol 2: Structure-Based Pharmacophore Generation with Exclusion Volumes

When the 3D structure of the target is available, specificity can be built directly into the model.

1. Protein-Ligand Complex Preparation:

- Obtain a high-quality structure from the PDB (e.g., 3E8D for Akt2) [10].

- Prepare the protein structure by adding hydrogen atoms, correcting protonation states, and treating missing residues.

2. Binding Site and Interaction Analysis:

- Define the binding site around the co-crystallized ligand.

- Use software (e.g., Discovery Studio) to generate all possible interaction points (hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions, ionic interactions) between the protein and a hypothetical ideal ligand [3] [10].

3. Feature Selection and Exclusion Volume Addition:

- Manually select the most relevant interaction features based on conserved interactions with known inhibitors or key catalytic residues.

- Add exclusion volumes (spheres that represent forbidden space) based on the protein structure to account for the shape of the binding pocket and prevent the matching of molecules that would cause steric clashes [3] [10].

The following diagram illustrates this structure-based workflow:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

Table 2: Key Resources for Pharmacophore Modeling with Specificity

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Relation to Specificity |

|---|---|---|

| Catalyst/HypoGen [35] | Software Algorithm | Explicitly uses inactive compounds in its algorithm to refine pharmacophore features and improve model specificity. |

| Exclusion Volumes [3] | Software Feature | Represent forbidden areas in the binding site, preventing the selection of molecules that would cause steric clashes. |

| Decoy Set (e.g., DUD-E) | Validation Database | A collection of pharmaceutically relevant molecules used to test a model's ability to discriminate actives from inactives. |

| ZINC Database [13] [10] | Compound Library | A large, publicly accessible database of commercially available compounds used for virtual screening to test pharmacophore models. |

| Discovery Studio [13] [10] | Software Suite | A comprehensive commercial software package that includes tools for both structure-based and ligand-based pharmacophore modeling, validation, and virtual screening. |

| ROCS (Rapid Overlay of Chemical Structures) | Software Tool | Performs shape-based and feature-based molecular superimposition, helping to identify common pharmacophores from a set of active ligands. |

FAQ: Troubleshooting Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

Q1: Why does my pharmacophore model perform poorly in virtual screening, despite using known active compounds?

Poor performance often stems from an unrepresentative training set or inadequate handling of ligand flexibility [4] [7]. If your training set assumes all active compounds share a single binding mode, but they actually bind in multiple ways, the generated model will be inaccurate [4]. Furthermore, if the conformational ensemble used for model generation does not include the true bioactive conformation, the essential chemical features will be misrepresented.

- Solution: Implement a robust training set selection strategy. For targets with suspected multiple binding modes, use Strategy II for training set creation. This involves jointly clustering active and inactive compounds and building multiple models from different training sets to account for binding variability [4]. Ensure your conformer generation protocol samples a wide energy range (e.g., up to 50 kcal/mol) to capture extended and flexible structures, not just the most stable conformers [4].

Q2: How can I generate a bioactive conformation when the protein structure is unknown or highly flexible?

When the protein structure is unavailable (e.g., for GPCRs) or the binding pocket is highly flexible (like LXRβ), a ligand-based pharmacophore approach is your primary tool [3] [7]. The key is to use a diverse set of known active ligands to infer the essential binding features.

- Solution: Employ a multi-ligand alignment strategy. Generate multiple conformers for each known active compound and align them to identify common chemical features and their spatial arrangements [7]. For highly flexible targets, generating models based on a combination of multiple ligand alignments and, if available, information from several ligand-bound crystal structures yields the most reliable results [7]. Advanced AI tools like DiffPhore can also predict binding conformations by learning from 3D ligand-pharmacophore pairs, even without a protein structure [11].

Q3: What is the recommended protocol for generating conformers for a training set?

A detailed, computationally feasible protocol is as follows [4]:

- Stereoisomer Enumeration: Enumerate all possible stereoisomers for molecules with undefined chiral centers or double-bond geometry. Treat each stereoisomer as a separate parent compound.

- Conformer Generation: For each compound/stereoisomer, generate a large ensemble of conformers (e.g., up to 100) within a wide energy window (e.g., 50 kcal/mol after minimization using a force field like MMFF94). This ensures the sampling of extended structures for flexible molecules.

- Energy Minimization: Minimize the energy of all generated conformers using the same force field to ensure geometric realism.

Q4: My model identifies too many false positives during virtual screening. How can I improve its precision?

A high false positive rate (FPR) often indicates a model that is too promiscuous or lacks critical steric constraints [4].

- Solution:

- Incorporate Inactive Compounds: The most effective method is to include known inactive compounds in your training set. During model development, select for pharmacophore hypotheses that occur predominantly in active compounds and are absent in inactives [4].

- Post-Processing: Remove overly simplistic models that have three or fewer distinct spatial feature coordinates, as these can be non-specific [4].

- Add Exclusion Volumes: If you have some structural information about the target, adding exclusion volumes (XVOL) to your pharmacophore model can represent forbidden areas in the binding pocket, drastically reducing false positives by sterically filtering out unsuitable compounds [3] [11].

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Table 1: Key Parameters for Conformational Sampling in Pharmacophore Modeling This table summarizes critical settings for generating comprehensive conformational ensembles, a prerequisite for successful model building [4].

| Parameter | Recommended Setting | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Force Field | MMFF94 | Provides energy minimization and conformational optimization for realistic 3D geometries. |

| Energy Cutoff | 50 kcal/mol | A wide energy window ensures sampling of extended and flexible structures, not just low-energy folded conformers. |

| Max Conformers per Compound | 100 | Balances computational cost with the need for comprehensive conformational coverage. |

| Convergence Criteria | Root Mean Square (RMS) gradient | Standard criterion (e.g., 0.001) for energy minimization termination. |

Methodology: Training Set Selection Strategies

The choice of training set is critical and depends on the assumed binding behavior of the active compounds [4].

Strategy I: Single Binding Mode Assumption

- Use Case: When all active compounds are presumed to share the same binding mode.

- Protocol:

- Calculate 2D pharmacophore fingerprints for all active and inactive compounds.

- Cluster actives and inactives separately using a method like Butina clustering.

- Select the centroid (most representative compound) of each cluster containing at least 5 compounds for the training set.

- All remaining compounds form the test set for external validation.

Strategy II: Multiple Binding Mode Assumption

- Use Case: For targets where active compounds may bind in different ways.

- Protocol:

- Calculate 2D pharmacophore fingerprints for all compounds.

- Cluster active and inactive compounds jointly.

- From each resulting cluster, randomly select 5 active and 5 inactive compounds for the training set. (Ignore clusters with fewer than 5 actives).

- Add centroids from clusters of only inactive compounds to better represent negative examples.

- This process creates multiple training sets, all of which are used for model development. Each model is validated against its complementary test set.

The workflow for generating a pharmacophore model from a prepared training set is as follows:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Software Tools for Pharmacophore Modeling and Conformation Generation

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function in this Context |

|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Open-source Cheminformatics | Used for 2D pharmacophore fingerprint calculation, clustering of training sets, and conformer generation with the MMFF94 force field [4]. |

| DiffPhore | AI-based Diffusion Model | A deep learning framework for "on-the-fly" 3D ligand-pharmacophore mapping; predicts ligand binding conformations that match a given pharmacophore model [11]. |

| PHASE | Commercial Software | Provides a comprehensive environment for both ligand- and structure-based pharmacophore model development, hypothesis generation, and virtual screening [3] [37]. |

| MOE (Molecular Operating Environment) | Commercial Modeling Suite | Contains integrated workflows for pharmacophore query creation, molecular docking, and conformational analysis [38]. |

| AncPhore | Pharmacophore Tool | Used to detect pharmacophore features and generate 3D ligand-pharmacophore pairs for dataset creation and analysis [11]. |

The following diagram illustrates the core conceptual workflow for addressing ligand flexibility and alignment to arrive at a bioactive conformation, integrating both traditional and AI-powered paths.

Utilizing Software Tools for Feature Extraction and Pharmacophore Generation (e.g., LigandScout, MOE, ConPhar)

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting & FAQs

This support center addresses common issues encountered during feature extraction and pharmacophore generation, with an emphasis on how these challenges relate to the integrity of your initial training set—a critical factor for successful ligand-based pharmacophore modeling.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why does my generated pharmacophore model fail to retrieve active compounds during virtual screening?

- A: This is often a training set issue. The model may be over-fitted to the specific chemical scaffolds in your training set. Ensure your training set contains structurally diverse active compounds that share the same mechanism of action. Incorporate known inactive compounds to help the software distinguish relevant features from molecular noise.

Q2: What is the recommended number of ligands for a training set in ligand-based pharmacophore generation?

- A: While there is no fixed number, the consensus from recent literature suggests a minimum of 15-20 diverse, high-affinity active compounds. A larger, well-curated set (30+) generally leads to more robust and predictive models. See Table 1 for a summary.

Q3: My protein-ligand complex has a co-crystallized water molecule. Should I include it as a feature in LigandScout?

- A: This is a critical decision. If the water molecule is known to be a crucial bridging element in ligand binding (a "structural water"), including it as a feature can significantly improve model selectivity. However, if its role is ambiguous, it can introduce false positives. Consult biochemical data or run simulations to determine the water's stability.

Q4: In MOE, what is the difference between the "Pharmacophore Query" and "Shape Query" and when should I use them?