Single-Cell Sequencing in Cancer Research: Decoding Tumor Heterogeneity for Precision Medicine

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the transformative role of single-cell sequencing (SCS) in oncology.

Single-Cell Sequencing in Cancer Research: Decoding Tumor Heterogeneity for Precision Medicine

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the transformative role of single-cell sequencing (SCS) in oncology. It explores the foundational principles that enable the dissection of cellular heterogeneity and intra-tumor diversity. The review details core methodologies and their specific applications in cancer research, from biomarker discovery to tracking clonal evolution. It addresses key technical and analytical challenges, offering insights into troubleshooting and optimizing SCS workflows. Finally, it covers validation strategies and comparative analyses that benchmark SCS against bulk sequencing, synthesizing how this technology is revolutionizing our understanding of cancer biology and paving the way for personalized therapeutic interventions.

Unraveling Cancer Complexity: How Single-Cell Sequencing Reveals Cellular Heterogeneity and the Tumor Microenvironment

The Paradigm Shift from Bulk to Single-Cell Analysis in Oncology

The field of oncology is undergoing a profound methodological transformation, moving from population-averaged measurements to high-resolution single-cell analysis. Traditional bulk RNA sequencing has provided valuable insights into cancer biology by measuring the average gene expression profile across all cells in a sample [1]. However, this approach inherently masks the cellular heterogeneity that drives critical cancer processes including tumor evolution, metastasis, and therapeutic resistance [1] [2]. The emergence of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) technologies has fundamentally altered this landscape by enabling researchers to dissect complex tumor ecosystems at individual cell resolution, revealing previously obscured cellular subtypes, states, and interactions [1] [3].

This paradigm shift is particularly significant for understanding the tumor microenvironment (TME), a complex milieu where cancer cells interact with immune cells, fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and other stromal components [4]. ScRNA-seq has demonstrated that what appeared as homogeneous tumor masses in bulk analyses are actually composed of remarkably diverse cellular communities with distinct molecular signatures and functional states [5] [4]. This technological advancement has opened new avenues for identifying rare cell populations, reconstructing developmental trajectories, and discovering novel therapeutic targets across cancer types [1] [2].

Key Technological Differences: A Comparative Analysis

Fundamental Methodological Divergence

The core distinction between bulk and single-cell RNA sequencing lies in their fundamental approach to sample processing and analysis. Bulk RNA-seq involves extracting RNA from thousands to millions of cells simultaneously, generating a composite expression profile representing the population average [1]. While this approach efficiently identifies differentially expressed genes between conditions (e.g., tumor vs. normal), it cannot determine whether expression changes occur uniformly across all cells or are driven by specific subpopulations [1].

In contrast, scRNA-seq begins with dissociating tissue into viable single-cell suspensions, followed by partitioning individual cells into reaction vessels [1] [6]. The 10x Genomics Chromium system, a leading scRNA-seq platform, accomplishes this through microfluidic partitioning that encapsulates individual cells in nanoliter-scale droplets known as Gel Bead-in-Emulsions (GEMs) [1] [3]. Within each GEM, cell-specific barcodes are incorporated into cDNA during reverse transcription, enabling subsequent computational deconvolution of pooled sequencing data back to individual cells [1] [3].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Bulk versus Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Approaches

| Feature | Bulk RNA-Seq | Single-Cell RNA-Seq |

|---|---|---|

| Resolution | Population average [1] | Individual cells [1] |

| Key Strength | Detects population-level expression changes [1] | Reveals cellular heterogeneity and rare cell types [1] |

| Heterogeneity Analysis | Masks cellular diversity [1] | Characterizes distinct cell subtypes and states [1] [5] |

| Ideal Applications | Differential expression, biomarker discovery, pathway analysis [1] | Cell atlas construction, tumor microenvironment mapping, lineage tracing [1] [2] |

| Cell Capture | N/A (population input) | Microfluidic partitioning (e.g., GEMs) [1] [3] |

| Cost Considerations | Lower per-sample cost [1] | Higher initial cost, decreasing with new technologies [1] [7] |

Practical Implementation and Technical Considerations

The practical implementation of these technologies involves markedly different workflows and considerations. Bulk RNA-seq workflows are relatively straightforward, beginning with total RNA extraction from digested tissue samples, followed by cDNA synthesis and library preparation [1]. The simpler workflow and lower data complexity make bulk sequencing more accessible for many laboratories [1].

ScRNA-seq requires more specialized sample preparation focused on generating high-quality single-cell suspensions with optimal cell viability (>85%), appropriate concentration (700-1,200 cells/μL), and minimal cellular aggregates [6] [3]. Sample dissociation protocols must be carefully optimized for different tissue types while preserving RNA integrity [6]. The 10x Genomics platform typically captures 500-5,000 genes per cell, with mRNA capture efficiency ranging from 10-50% of cellular transcripts [3]. Technical challenges include managing amplification bias, ambient RNA contamination, and maintaining low multiplet rates (<5%) through careful cell loading calculations [3].

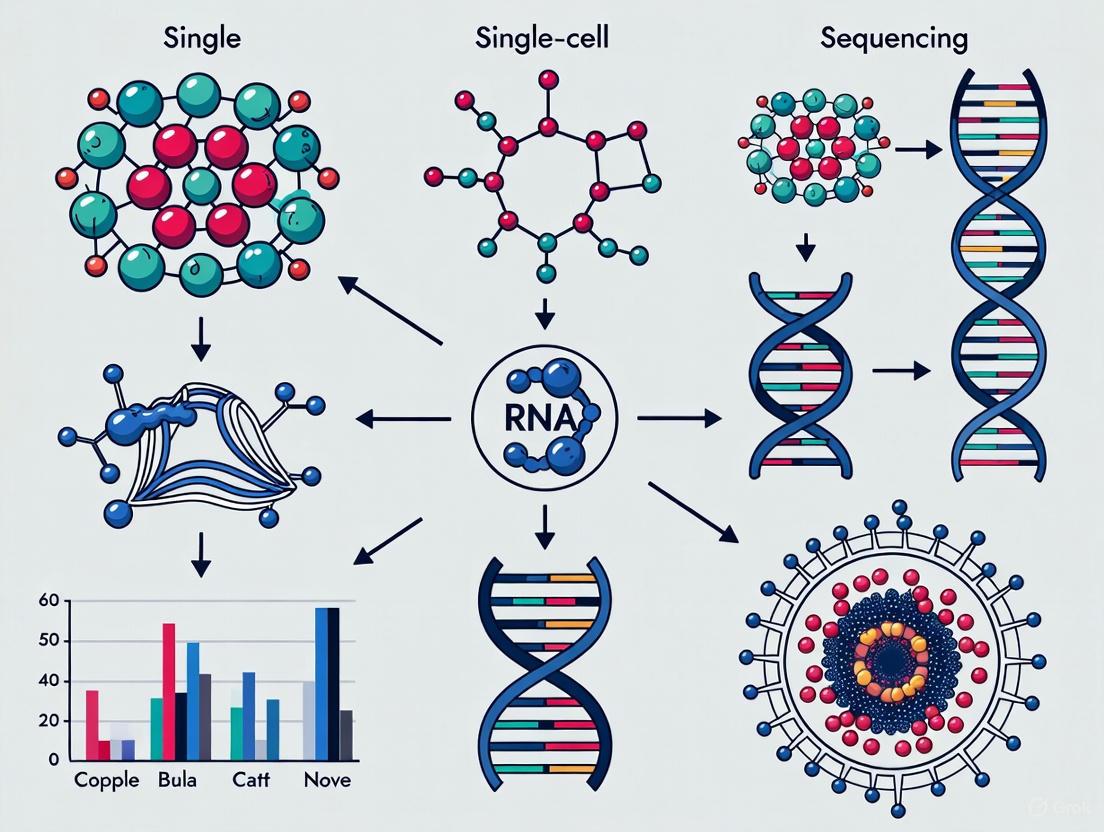

Diagram 1: Fundamental workflow differences between bulk and single-cell RNA sequencing approaches. Bulk analysis produces population averages that mask heterogeneity, while single-cell methods preserve cellular diversity through barcoding strategies.

Applications in Oncology Research

Characterizing Tumor Heterogeneity and the Microenvironment

Single-cell analysis has revolutionized our understanding of intratumoral heterogeneity across cancer types. In retinoblastoma, scRNA-seq analysis of primary tumor tissues from 10 patients revealed distinct subpopulations of cone precursor (CP) cells with varying proportions in invasive versus non-invasive tumors [5]. Researchers identified four distinct CP subpopulations (CP1-CP4), with CP4 exhibiting elevated TGF-β signaling specifically in invasive retinoblastoma [5]. Similarly, in cervical cancer, scRNA-seq has identified four distinct tumor subtypes: hypoxic, proliferative, differentiated, and immunoreactive, with epithelial cells existing in three transcriptional states (cytokeratin⁺, immune-interacting, and senescent) [4].

The power of single-cell approaches extends to comprehensive tumor microenvironment (TME) characterization. Cell-cell interaction analysis in retinoblastoma revealed rewired communication networks in invasive tumors, with specifically increased fibroblast-CP interactions [5]. In cervical cancer, scRNA-seq has elucidated a complex interplay between exhausted PD-1⁺LAG3⁺TIM3⁺ T cells, immunosuppressive stromal cells (MYH9⁺ cancer-associated fibroblasts, PODXL⁺ endothelial cells), and rare but potent effector populations (FGFBP2⁺ NK cells, CXCL13⁺ tissue-resident memory T cells) [4].

Cancer Stem Cells and Drug Resistance Mechanisms

ScRNA-seq has proven particularly valuable for investigating cancer stem cells (CSCs) and their role in therapeutic resistance. In esophageal cancer (ESCA), researchers integrated scRNA-seq and bulk RNA-seq to identify unique tumor stem cells and construct prognostic markers [8]. Using CytoTRACE, a computational method that predicts cellular stemness by measuring transcriptional diversity, scientists quantified stemness potential in tumor-derived epithelial cell clusters [8]. This approach led to developing an 18-gene tumor stem cell marker signature (TSCMS) that effectively stratified patients into risk groups with distinct prognosis and drug sensitivity patterns [8].

The technology has also enabled identification of specific resistance mechanisms. In B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL), researchers leveraged both bulk and single-cell RNA-seq to identify developmental states driving resistance and sensitivity to asparaginase, a common chemotherapeutic agent [1]. Similarly, in cervical cancer, scRNA-seq has revealed resistance mechanisms including NFKB1 mutations and BCL10⁺ Treg-mediated suppression [4].

Table 2: Key Single-Cell Applications Across Cancer Types with Representative Findings

| Cancer Type | Single-Cell Application | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Retinoblastoma | Tumor heterogeneity analysis [5] | Identified 4 cone precursor subpopulations; CP4 shows elevated TGF-β signaling in invasion [5] |

| Cervical Cancer | Tumor microenvironment mapping [4] | Revealed hypoxic, proliferative, differentiated, immunoreactive subtypes; exhausted T cell states [4] |

| Esophageal Cancer | Cancer stem cell identification [8] | Developed 18-gene stemness signature (TSCMS) for prognosis and drug response prediction [8] |

| Pan-Cancer | Immunotherapy biomarker discovery [9] | EGFR-related gene signature predicts immune checkpoint inhibitor response (AUC=0.77) [9] |

| B-ALL | Chemotherapy resistance mechanisms [1] | Identified developmental states driving asparaginase resistance and sensitivity [1] |

Biomarker Discovery and Immunotherapy Applications

Single-cell technologies are accelerating biomarker discovery for precision oncology. In pan-cancer analysis of 34 scRNA-seq cohorts, researchers identified an EGFR-related gene signature (EGFR.Sig) that accurately predicts response to immune checkpoint inhibitors with an AUC of 0.77, outperforming previously established signatures [9]. This signature included 12 core genes, four of which were validated as immune resistance genes in independent CRISPR studies [9].

The technology has also enabled detailed characterization of immunosuppressive networks within tumors. In cervical cancer, scRNA-seq revealed GALNT3-mediated immunosuppression and SPP1⁺ tumor-associated macrophages as key mediators of immune evasion [4]. These findings have direct implications for developing combination immunotherapy strategies that simultaneously target multiple resistance mechanisms.

Integrated Analysis Protocols

Complementary Bulk and Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Approaches

While single-cell technologies provide unprecedented resolution, integrated analysis of both scRNA-seq and bulk RNA-seq data often delivers the most comprehensive biological insights [5] [9] [8]. This integrated approach leverages the resolution of single-cell data with the statistical power and clinical accessibility of bulk sequencing.

A representative integrated analysis protocol includes the following key steps:

Sample Processing and Data Generation: Generate scRNA-seq data from fresh tumor tissues using platforms such as 10x Genomics Chromium [5] [6]. Simultaneously, obtain bulk RNA-seq data from additional patient cohorts or public databases such as TCGA and GEO [5] [8].

Quality Control and Preprocessing: For scRNA-seq data, filter cells based on quality metrics (mitochondrial gene percentage <30%, gene counts between 200-10,000) using Seurat or similar packages [5] [8]. Normalize data using SCTransform or log-normalization methods [5].

Cell Type Annotation and Clustering: Perform dimensionality reduction (PCA, UMAP) and cluster identification [5]. Annotate cell types using established marker genes (PTPRC for immune cells, EPCAM for epithelial cells, COL1A1 for fibroblasts) [8].

Specialized Subpopulation Analysis: For tumor cells, infer copy number variations using InferCNV to distinguish malignant from non-malignant cells [5]. Estimate cellular stemness using CytoTRACE [8]. Reconstruct developmental trajectories using Monocle or similar pseudotime analysis tools [5].

Cell-Cell Communication Analysis: Identify significant ligand-receptor interactions using CellPhoneDB or NicheNet [5]. Compare interaction networks between clinical subgroups (e.g., invasive vs. non-invasive) [5].

Bulk Data Deconvolution and Validation: Use scRNA-seq findings to inform bulk data analysis. Perform consensus clustering on bulk RNA-seq data to identify molecular subtypes [5]. Develop prognostic signatures from single-cell-derived stemness genes and validate in bulk cohorts [8].

Diagram 2: Integrated analysis workflow combining single-cell and bulk RNA sequencing approaches. Both methods begin with the same tumor tissue but diverge in sample processing, eventually converging for comprehensive biological interpretation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Experiments

| Reagent/Category | Function | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Partitioning Systems | Microfluidic encapsulation of single cells | 10x Genomics Chromium X series [1]; Enables GEM formation with barcoded gel beads [3] |

| Barcoding Chemistry | Cell-specific mRNA labeling | Gel Beads containing barcoded oligonucleotides with UMIs [1] [3]; GEM-X Flex and Universal assays [1] |

| Sample Prep Kits | Tissue dissociation and cell preparation | Demonstrated Protocols for specific tissues [6]; Optimization required for sensitive samples [6] |

| Viability Stains | Assessment of cell integrity | Critical for ensuring >85% viability [3]; Exclusion of dead cells reduces background RNA [6] |

| Enzymatic Mixes | cDNA synthesis and amplification | Reverse transcription master mixes; Template-switch oligo strategies address oligo(dT) bias [3] |

| Library Prep Kits | Sequencing library construction | 3' end enrichment for cost-effectiveness; Full-length for splicing information [2] |

| Bioinformatic Tools | Data analysis and interpretation | Seurat, SCTransform for normalization [5] [8]; CellPhoneDB for cell-cell interactions [5]; CytoTRACE for stemness [8] |

The paradigm shift from bulk to single-cell analysis in oncology represents more than just a technical advancement—it constitutes a fundamental transformation in how we conceptualize and investigate cancer biology. The ability to profile individual cells within complex tumor ecosystems has revealed unprecedented heterogeneity, identified rare but functionally critical cell populations, and uncovered novel therapeutic targets [1] [2] [4]. This resolution revolution is advancing both basic cancer biology and clinical translation through improved diagnostic classifications, prognostic biomarkers, and treatment strategies [10] [9].

Future developments will likely focus on multi-omics integration, combining transcriptomic data with genomic, epigenomic, and proteomic information from the same single cells [10] [3]. The integration of spatial transcriptomics will further bridge the gap between single-cell resolution and tissue context, preserving critical spatial relationships within the tumor architecture [10] [4]. Computational advances, particularly in artificial intelligence and machine learning, will be essential for extracting meaningful biological insights from the increasingly complex and high-dimensional datasets generated by these technologies [2] [10].

As single-cell methodologies continue to evolve toward higher throughput, lower costs, and increased accessibility, they promise to deepen our understanding of cancer biology and accelerate the development of personalized therapeutic approaches [7] [3]. The ongoing paradigm shift from population-averaged to single-cell analysis ultimately moves oncology closer to the goal of precision medicine, where treatments can be tailored to the unique cellular composition and molecular characteristics of each patient's tumor [2] [10].

The transition from bulk sequencing to single-cell analysis has revolutionized our understanding of cancer biology, revealing unprecedented insights into tumor heterogeneity, microenvironment interactions, and therapeutic resistance mechanisms. Single-cell technologies now enable simultaneous profiling of multiple molecular layers—transcriptomics, epigenomics, and genomics—from the same individual cell. This multi-omic approach is particularly valuable in cancer research, where cellular heterogeneity drives disease progression and treatment response. The integration of gene expression data with epigenetic information allows researchers to reconstruct regulatory networks and identify master transcriptional regulators operating in distinct cellular subpopulations within tumors. These advances are paving the way for more precise diagnostic biomarkers and targeted therapeutic strategies in oncology.

Core Technological Principles

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing (scRNA-seq)

Single-cell RNA sequencing has become the foundational technology for probing cellular heterogeneity in complex tissues. The core principle involves capturing individual cells, reverse transcribing their RNA into cDNA, amplifying the genetic material, and preparing sequencing libraries that maintain cell-of-origin information through genetic barcoding. Two primary amplification strategies dominate current methodologies: polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based amplification used in Smart-Seq2, Drop-Seq, and 10x Genomics protocols; and in vitro transcription (IVT)-based amplification employed in CEL-Seq and MARS-Seq [11]. The implementation of unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) has been crucial for mitigating PCR amplification biases, enabling truly quantitative measurement of transcript abundance [11]. Different scRNA-seq protocols offer distinct advantages—full-length transcript methods (e.g., Smart-Seq2) enable isoform usage analysis and detection of allelic expression, while 3' end counting methods (e.g., Drop-Seq, 10x Genomics) provide higher throughput and lower cost per cell, making them particularly suitable for analyzing complex tumor ecosystems [11].

Single-Cell Epigenomic Profiling

Epigenetic regulation operates through three primary mechanisms: DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNA-mediated silencing. At single-cell resolution, these marks can be mapped to specific genomic loci and correlated with transcriptional states.

DNA methylation at the C5 position of cytosine in CpG dinucleotides is detected using bisulfite conversion or enzymatic conversion methods. In cancer, hypermethylation of tumor suppressor gene promoters leads to their silencing, while global hypomethylation contributes to genomic instability [12]. The recently developed scEpi2-seq method leverages TET-assisted pyridine borane sequencing (TAPS) for DNA methylation detection, which converts methylated cytosine to uracil while leaving barcoded adaptors intact, unlike traditional bisulfite-based approaches that can damage nucleic acids [13].

Histone modifications including methylation, acetylation, phosphorylation, and ubiquitination are detected using antibody-directed strategies. The scEpi2-seq protocol tethers a protein A-micrococcal nuclease (pA-MNase) fusion protein to specific histone modifications using antibodies, enabling targeted cleavage and sequencing of nucleosome-associated DNA [13]. This approach has revealed how repressive marks like H3K27me3 and H3K9me3 associate with lower DNA methylation levels, while active marks like H3K36me3 show higher methylation in gene bodies [13].

Chromatin accessibility is typically assessed using single-cell ATAC-seq (scATAC-seq), which employs a hyperactive Tn5 transposase to integrate adapters into accessible genomic regions. A recent systematic benchmarking of eight scATAC-seq methods revealed significant differences in sequencing library complexity and tagmentation specificity, which impact cell-type annotation, peak calling, and transcription factor motif enrichment analyses [14].

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Single-Cell Multi-Omics Methods

| Method | Molecular Features Detected | Cells Profiled | Key Applications in Cancer | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| scEpi2-seq | Histone modifications (H3K9me3, H3K27me3, H3K36me3) + DNA methylation | 1,716-1,981 cells [13] | Epigenetic interactions during cell type specification; DNA methylation maintenance | Uses TAPS instead of bisulfite treatment; 50,000+ CpGs per cell; FRiP 0.72-0.88 [13] |

| scATAC-seq | Chromatin accessibility | 169,000 PBMC profiles [14] | Regulatory landscape mapping in tumor microenvironments | Varies by protocol; differences in library complexity impact cell-type annotation [14] |

| 10x Genomics Multiome | Gene expression + chromatin accessibility | Thousands of cells simultaneously | Coordinated gene regulation in tumor subpopulations | Requires viable single cells; cell diameter <30μm for droplet-based systems [11] |

| scCOOL-seq | Chromatin state, CNVs, ploidy, DNA methylation | Method-dependent | Tumor evolution and heterogeneity | Simultaneous multi-parametric profiling [2] |

Integrated Multi-Omics Workflow

The simultaneous detection of multiple epigenetic marks and gene expression patterns requires sophisticated experimental design and computational integration. The scEpi2-seq workflow exemplifies this integrated approach: after cell permeabilization, antibodies specific to histone modifications tether pA-MNase to nucleosomes. Single cells are sorted into multiwell plates, and MNase digestion is initiated by calcium addition. The resulting fragments undergo end repair, A-tailing, and adapter ligation containing cell barcodes, UMIs, and Illumina handles. The material is then subjected to TAPS conversion, followed by library preparation involving in vitro transcription, reverse transcription, and PCR amplification [13]. This elegant workflow enables simultaneous extraction of histone modification patterns (from fragment genomic locations), DNA methylation status (from C-to-T conversions), and nucleosome spacing information (from distances between sequencing read starts) from the same single cell.

For cancer researchers, proper sample preparation is critical for success. The 10x Genomics single cell protocols require a suspension of viable single cells or nuclei as input, with minimization of cellular aggregates, dead cells, and biochemical inhibitors of reverse transcription [6]. Tissue dissociation protocols must be optimized for specific tumor types, considering factors such as cellular dimensions, viability, and extracellular matrix composition. When tissue dissociation is challenging or samples are frozen, single-nuclei RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq) provides a viable alternative that also enables analysis of archived clinical specimens [2] [11].

Figure 1: Integrated Workflow for Single-Cell Multi-Omics Profiling. The experimental process begins with tumor tissue dissociation, progresses through single-cell barcoding and sequencing, and culminates in integrated analysis of multiple molecular layers.

Application Notes: Cancer Research Insights

Tumor Heterogeneity and Microenvironment

Single-cell multi-omics has dramatically advanced our understanding of the tumor ecosystem in breast cancer. A recent study comparing primary and metastatic ER+ breast tumors at single-cell resolution identified significant shifts in cellular composition and transcriptional states [15]. Metastatic lesions showed enrichment for CCL2+ macrophages with pro-tumorigenic properties, exhausted cytotoxic T cells, and FOXP3+ regulatory T cells, indicating an immunosuppressive microenvironment. Analysis of cell-cell communication highlighted markedly decreased tumor-immune cell interactions in metastatic tissues [15]. Copy number variation (CNV) analysis revealed higher genomic instability in metastatic tumor cells, with specific CNVs in chromosomal regions containing genes associated with cancer aggressiveness (ARNT, BIRC3, MSH2, MSH6, MYCN) [15].

Epigenetic Dynamics in Cancer Progression

The application of scEpi2-seq to cancer models has revealed how epigenetic modifications interact during malignant progression. In studies of mouse intestine, simultaneous profiling of H3K27me3 and DNA methylation provided insights into epigenetic interactions during cell type specification [13]. Differentially methylated regions demonstrated independent cell-type regulation in addition to H3K27me3 regulation, revealing that CpG methylation acts as an additional layer of control in facultative heterochromatin [13]. These findings have important implications for understanding how epigenetic therapies may function in cancer treatment.

Clinical Translation and Biomarker Discovery

The clinical application of scRNA-seq technology has revolutionized our capacity to study cell functions in complex tumor microenvironments [2]. Traditional transcriptomic approaches lacked the resolution to distinguish signals from heterogeneous cell populations or rare cell types, limiting their clinical utility. Single-cell approaches now enable biomarker discovery through identification of rare cell populations, characterization of drug resistance mechanisms, and mapping of cellular differentiation trajectories in response to therapy. The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning algorithms into analysis of single-cell data offers promise for overcoming analytical challenges, potentially allowing multi-omics approaches to bridge the gap in our understanding of complex biological systems and advance the development of precision medicine [2].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Single-Cell Multi-Omics

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| pA-MNase fusion protein | Tethers to histone modifications via antibodies; cleaves nucleosomal DNA | Used in scEpi2-seq for targeted histone profiling; requires Ca2+ activation [13] |

| TET-assisted pyridine borane (TAPS) | Converts 5mC to uracil for methylation detection | Gentler alternative to bisulfite treatment; preserves adapter sequences [13] |

| Cell barcodes with UMIs | Tags molecules with cell identity and unique molecular identifiers | Enables quantitative analysis and eliminates PCR amplification biases [11] |

| Feature barcoding antibodies | Labels surface proteins with oligonucleotide tags | Enables simultaneous protein and gene expression measurement (CITE-seq) |

| Chromium Single Cell Platform | Microfluidic partitioning of cells | Enables 3' mRNA, 5' mRNA, ATAC, and multiome assays [11] |

| SCANPY/SEURAT | Bioinformatics toolkit for scRNA-seq analysis | Open-source platforms for dimensionality reduction, clustering, trajectory inference [2] |

Experimental Protocol: scEpi2-seq for Simultaneous Histone and DNA Methylation Profiling

Sample Preparation and Quality Control

Begin with preparation of high-quality single-cell suspensions from tumor tissue. For solid tumors, optimize enzymatic and mechanical dissociation protocols to maximize cell viability while preserving epitopes and epigenetic marks. Filter suspensions through appropriate mesh (30-70μm) to remove aggregates and debris. Assess cell viability using trypan blue or fluorescent viability dyes, aiming for >90% viability. For frozen samples or difficult-to-dissociate tissues, consider nuclear isolation as an alternative. For clinical samples, prioritize rapid processing to minimize artifactual changes in gene expression and epigenetic marks [6] [12].

Cell Sorting and Permeabilization

Using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), sort individual cells into 384-well plates containing permeabilization buffer. Permeabilize cells with appropriate detergents (e.g., 0.1% Triton X-100) to enable antibody access to nuclear antigens while maintaining cellular integrity. Include empty wells as negative controls to assess background signal [13].

Antibody Binding and MNase Digestion

Incubate permeabilized cells with histone modification-specific antibodies (e.g., anti-H3K9me3, anti-H3K27me3, anti-H3K36me3) conjugated to pA-MNase fusion protein. After antibody binding, initiate MNase digestion by adding Ca2+ to a final concentration of 2mM. Incubate for precisely 10 minutes at 37°C, then stop the reaction with excess EDTA. The MNase will preferentially cleave nucleosomal DNA adjacent to the targeted histone modifications [13].

Fragment Processing and Adapter Ligation

Recover the cleaved fragments and perform end repair and A-tailing using standard molecular biology enzymes. Ligate adapters containing cell barcodes, unique molecular identifiers (UMIs), T7 promoter sequences, and Illumina handles. Pool material from the 384-well plate for subsequent processing steps [13].

TAPS Conversion and Library Preparation

Perform TET-assisted pyridine borane sequencing (TAPS) to convert 5-methylcytosine to uracil while preserving adapter sequences. Unlike bisulfite treatment, TAPS does not degrade DNA or damage barcoded adapters. Following conversion, prepare sequencing libraries through in vitro transcription (IVT), reverse transcription, and PCR amplification. The resulting libraries contain information about histone modifications (from genomic locations of fragments), DNA methylation (from C-to-T conversions), and nucleosome positioning (from fragment size distributions) [13].

Figure 2: scEpi2-seq Experimental Workflow. Detailed protocol for simultaneous profiling of histone modifications and DNA methylation at single-cell resolution.

Quality Control and Data Processing

After sequencing, perform comprehensive quality control assessing cell barcode retrieval rates, mappability, mismatch rates, and TAPS conversion efficiency (>95% expected). Filter low-quality cells based on unique read counts and average methylation levels per cell, typically retaining 35-80% of cells after quality control [13]. Calculate fraction of reads in peaks (FRiP) for histone modification data, with values of 0.72-0.88 indicating high specificity [13]. Process the data through specialized bioinformatic pipelines that separately extract histone modification patterns, DNA methylation status, and nucleosome positioning information before integrating these datasets for multi-omic analysis.

The integration of gene expression and epigenetic profiling at single-cell resolution represents a transformative approach in cancer research, enabling unprecedented resolution of tumor heterogeneity and regulatory mechanisms. The core principles outlined—including scRNA-seq for transcriptional profiling, scATAC-seq for chromatin accessibility mapping, and emerging multi-omic technologies like scEpi2-seq for simultaneous histone and DNA methylation analysis—provide powerful tools for deconvoluting the complex circuitry of cancer biology. As these technologies continue to evolve, with improvements in throughput, cost reduction, and analytical sophistication, they promise to uncover novel therapeutic targets, refine diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers, and ultimately advance personalized cancer medicine. The implementation of rigorous quality control standards and appropriate experimental design will be crucial for maximizing the biological insights gained from these powerful single-cell multi-omics approaches.

The tumor microenvironment (TME) is a complex and dynamic ecosystem composed of malignant cells, immune cells, and stromal cells, all embedded in an extracellular matrix [16] [17]. Understanding the precise interactions between these components is critical for deciphering tumor biology and developing novel therapeutic strategies. Single-cell sequencing technologies have revolutionized this endeavor by enabling the detailed characterization of each cellular player at unprecedented resolution [18]. Moving beyond bulk sequencing, which averages signals across all cells, single-cell approaches reveal the profound heterogeneity within and between tumors, uncovering rare cell populations and intricate cell-cell communication networks that drive cancer progression, metastasis, and therapy resistance [18] [19]. This document outlines detailed application notes and protocols for using single-cell multi-omics to map the tumor ecosystem, providing a practical framework for researchers and drug development professionals.

Experimental Workflow for Single-Cell Multi-Omics Analysis

A typical integrated single-cell multi-omics workflow involves the coordinated processing of samples for simultaneous analysis of gene expression and chromatin accessibility, followed by sophisticated bioinformatic integration.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogues essential reagents and tools used in single-cell multi-omics studies of the TME, as evidenced by recent literature.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Single-Cell TME Analysis

| Item Name | Function/Application | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 10x Genomics Chromium Next GEM Chip J | Captures single cells/nuclei into droplets for parallel processing [20]. | Part of the Chromium Next GEM Single Cell Multiome ATAC + Gene Expression Reagent Kits [20]. |

| Tn5 Transposase | Enzyme that cleaves DNA in open chromatin regions and inserts sequencing adapters for scATAC-seq [20] [19]. | Found in the 10x Genomics Multiome ATAC + Gene Expression reagent kits [20]. |

| Nuclei Buffer | Provides an isotonic environment to maintain nuclear integrity after tissue dissociation [20]. | Often supplemented with DTT and RNase Inhibitor for stability [20]. |

| Iodixanol Density Gradient | Purifies nuclei by centrifugation, separating them from cellular debris and intact cells [20]. | Nuclei are collected from the interface between 29% and 35% iodixanol solutions [20]. |

| Signac R Package | A comprehensive toolkit for the analysis of scATAC-seq data, including quality control, clustering, and integration with scRNA-seq [20]. | Version 1.6.0 used for quality control and peak-gene link network construction [20]. |

| Seurat R Package | A standard platform for the analysis and integration of single-cell data, particularly scRNA-seq [20]. | Used for clustering, visualization (UMAP/t-SNE), and differential expression analysis [20]. |

| BD Cellismo Data Visualization Tool | A no-code software for secondary analysis and visualization of single-cell multiomics data (RNA, protein, ATAC) [21]. | Enables generation of UMAP plots, heatmaps, and differential analysis without programming [21]. |

| Harmony Algorithm | Computational tool for integrating multiple single-cell datasets and removing batch effects [20]. | Used to harmonize data from different patients or studies [20]. |

Detailed Protocol: Single-Nuclei Multiome ATAC + Gene Expression Sequencing

This protocol is adapted from a recent study analyzing eight different carcinoma tissues [20].

A. Tissue Dissociation and Nuclei Isolation

- Tissue Preparation: Obtain fresh or frozen primary tumor and adjacent normal tissues (e.g., ~50 mg). Perform all steps on ice or at 4°C.

- Homogenization: Place the tissue fragment into a pre-chilled Dounce homogenizer containing 2 mL of cold 1x homogenization buffer (320 mM sucrose, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1% NP40, 5 mM CaCl2, 3 mM Mg(Ac)2, 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.8, 167 μM β-mercaptoethanol, 1x protease inhibitor cocktail, 1 U/μL RNase inhibitor). Homogenize with ~15 strokes using a loose 'A' pestle.

- Filtration and Further Homogenization: Filter the homogenate through a 70-μm nylon mesh to remove large debris. Then, homogenize the filtrate with an additional 20 strokes using a tight 'B' pestle.

- Secondary Filtration and Centrifugation: Filter the solution again through a 40-μm nylon mesh. Centrifuge the filtrate at 350 r.c.f. for 5 minutes. Carefully aspirate the supernatant.

- Nuclei Purification via Density Gradient:

- Resuspend the pellet in 400 μL of 1x homogenization buffer.

- Add an equal volume (400 μL) of 50% iodixanol to achieve a final concentration of 25% iodixanol.

- In a new centrifuge tube, carefully layer 600 μL of a 29% iodixanol solution underneath the 25% iodixanol mixture.

- Subsequently, layer 600 μL of a 35% iodixanol solution underneath the 29% layer.

- Centrifuge in a swinging-bucket rotor at 3000 r.c.f. for 35 minutes.

- After centrifugation, collect the purified nuclei, which localize at the interface between the 29% and 35% iodixanol solutions, in a volume of approximately 200 μL.

- Nuclei Wash and Count: Wash 500,000 nuclei in a wash buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 10 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 1% BSA, 0.1% Tween-20, 1 mM DTT, 1 U/μL RNase Inhibitor) by centrifuging at 500 r.c.f. for 5 minutes. Resuspend the final pellet in Diluted Nuclei Buffer and count using trypan blue.

B. Library Preparation and Sequencing

- Nuclei Loading: Aspirate 15,000 nuclei for library construction.

- Single-Cell Partitioning: Use the Chromium Next GEM Chip J and the Chromium Next GEM Single Cell Multiome ATAC + Gene Expression Reagent Kits from 10x Genomics according to the manufacturer's instructions. This step partitions individual nuclei into gel beads-in-emulsion (GEMs), where the barcoding reactions occur.

- Library Construction and Sequencing: Generate the scATAC-seq and scRNA-seq libraries from the same set of barcoded nuclei. Sequence the libraries on an Illumina Novaseq6000 platform. The recommended sequencing depth is at least 50,000 reads per cell using a paired-end 150 bp strategy.

Computational Analysis Pipeline

- Primary Data Processing:

- scRNA-seq: Use the

Cell Rangerpipeline (10x Genomics) for demultiplexing, alignment, and generation of a gene count matrix. Subsequent processing (quality control, normalization, clustering) is performed inSeurat[20]. - scATAC-seq: Use

Signacfor quality control, peak calling, and generation of a chromatin accessibility matrix [20].

- scRNA-seq: Use the

- Data Integration and Cell Annotation: Integrate the scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq datasets using tools like

Signac. Annotate cell types by comparing gene expression and chromatin accessibility patterns to known marker genes (e.g., EPCAM for tumor cells, CD247 for T cells, PDGFRA for fibroblasts) [20]. - Downstream Analysis:

- Gene Regulatory Networks (GRNs): Construct peak-gene link networks to identify candidate cis-regulatory elements (cCREs) and their target genes [20].

- Transcription Factor (TF) Activity: Infer TF activity by analyzing motif enrichment in accessible chromatin regions [20].

- Cell-Cell Communication: Use tools to analyze ligand-receptor interactions and infer communication pathways between malignant, immune, and stromal cells [19].

Key Findings and Data Synthesis from Single-Cell TME Studies

Single-cell analyses have yielded quantitative insights into the cellular composition and regulatory programs of various carcinomas.

Cellular Composition and Dynamics

Table 2: Cellular States in Primary vs. Metastatic ER+ Breast Cancer (scRNA-seq) Based on analysis of 23 patients [22]

| Cell Type | State / Subtype | Primary Tumor | Metastatic Lesion | Functional Implication |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Macrophages | CCL2+ macrophages | Lower abundance | Higher abundance | Contributes to a pro-tumorigenic microenvironment [22]. |

| Cytotoxic T Cells | Exhausted state | Lower abundance | Higher abundance | Loss of effector function, immune evasion [22]. |

| Regulatory T Cells | FOXP3+ T cells | Lower abundance | Higher abundance | Suppresses anti-tumor immunity [22]. |

| Tumor-Immune Interactions | Overall level | Increased | Markedly decreased | Contributes to an immunosuppressive ecosystem in metastasis [22]. |

| Signaling Pathway | TNF-α via NF-kB | Increased activation | - | Identified as a potential therapeutic target in primary disease [22]. |

Table 3: Tumor-Specific Transcription Factors in Colon Cancer (scATAC-seq & scRNA-seq) Identified as more highly activated in tumor vs. normal epithelial cells [20]

| Transcription Factor | Role in Malignant Transcriptional Programs | Validation |

|---|---|---|

| CEBPG | Pivotal in driving malignant programs; potential therapeutic target [20]. | Corroborated by multi-source data and in vitro experiments [20]. |

| LEF1 | Pivotal in driving malignant programs; potential therapeutic target [20]. | Corroborated by multi-source data and in vitro experiments [20]. |

| SOX4 | Pivotal in driving malignant programs; potential therapeutic target [20]. | Corroborated by multi-source data and in vitro experiments [20]. |

| TCF7 | Pivotal in driving malignant programs; potential therapeutic target [20]. | Corroborated by multi-source data and in vitro experiments [20]. |

| TEAD4 | Pivotal in driving malignant programs; potential therapeutic target [20]. | Corroborated by multi-source data and in vitro experiments [20]. |

| TEAD Family | Widely controls cancer-related signaling pathways in tumor cells [20]. | Conserved epigenetic regulation across multiple carcinoma types [20]. |

Stromal-Immune Cell Interactions in the TME

Stromal cells, particularly Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts (CAFs), are not passive bystanders but active participants in shaping an immunosuppressive TME. The diagram and table below summarize key pro-tumorigenic interactions.

Table 4: Key Pro-Tumorigenic Stromal-Immune Cell Interactions

| Stromal Cell | Immune Cell Partner | Mechanism of Interaction | Outcome in TME |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts (CAFs) | Myeloid-derived immune cells (e.g., Macrophages) | Secretion of cytokines and chemokines (e.g., IL-6, LIF, CXCL1) [16] [17]. | Enhanced tumorigenesis and immune evasion [16]. |

| CAFs | CD8+ T Cells | Induction of T cell exhaustion via undefined secreted factors [17]. | Suppression of anti-tumor cytotoxicity, promoting immune evasion [17]. |

| CAFs (CD10+/GPR77+ subtype) | General Immune Microenvironment | Enhances tumor cell survival and chemoresistance [17]. | Contributes to treatment resistance and poor patient outcome. |

| Tumor Endothelial Cells (TECs) | T Cells | Expression of PD-L1 and other immunomodulatory molecules [16]. | Facilitates immune evasion by inhibiting T-cell function [16]. |

The application of single-cell multi-omics technologies provides an unparalleled, high-resolution map of the tumor ecosystem. The detailed protocols and synthesized data presented here underscore the power of these approaches to dissect the cellular heterogeneity, identify critical regulatory nodes in malignant cells (such as the transcription factors CEBPG and TEAD4), and decode the complex pro-tumorigenic crosstalk between stromal and immune cells. These insights are rapidly translating into a new generation of biomarkers for patient stratification and novel therapeutic targets. As these technologies become more accessible and standardized, they will undoubtedly play a central role in guiding precise clinical decision-making and developing more effective, personalized cancer treatments.

Single-cell sequencing (SCS) has revolutionized cancer research by enabling high-resolution dissection of the cellular mosaic that constitutes a tumor. This Application Note details how SCS technologies provide unprecedented access to two fundamental hallmarks of cancer: intra-tumor heterogeneity (ITH) and clonal evolution. These processes underlie critical clinical challenges including therapy resistance, metastasis, and disease relapse [23] [24]. We frame these concepts within the practical context of experimental workflows, data analysis pipelines, and therapeutic applications, providing researchers and drug development professionals with actionable methodologies for interrogating tumor complexity at single-cell resolution.

Core Hallmarks Accessible via Single-Cell Sequencing

Intra-Tumor Heterogeneity (ITH)

ITH describes the coexistence of multiple genetically distinct subclones within an individual tumor [25]. Bulk sequencing approaches average signals across thousands of cells, obscuring this diversity, whereas SCS resolves it by profiling individual cells.

- Genetic Heterogeneity: SCS reveals diversity in DNA-level alterations. Single-cell DNA sequencing (scDNA-seq) can identify subclonal somatic copy-number alterations (SCNAs) and single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) that are missed by bulk sequencing [25]. For instance, in core-binding factor acute myeloid leukemia (CBF AML), integrated analysis of bulk and single-cell DNA sequencing revealed complex clonal architectures with 3-11 distinct AML clones per patient at diagnosis [25].

- Transcriptomic Heterogeneity: Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) captures diverse gene expression states among cancer cells, identifying functional subpopulations with varying metastatic potential, metabolic activities, and drug sensitivities [2] [23]. Analysis of melanomas via scRNA-seq revealed spatial and functional heterogeneity in both tumor and T cells, demonstrating a range of T-cell activation, clonal expansion, and exhaustion programs within the same tumor [23].

- Epigenetic Heterogeneity: Techniques like single-cell ATAC-seq (scATAC-seq) map variability in chromatin accessibility, linking regulatory element activity to cell states and gene expression patterns [23]. The integration of epigenomics with transcriptomics enables the construction of gene regulatory networks, helping to reveal the epigenetic status of tumor and immune cells, and thus assessing their resistance mechanisms to therapy [24].

Table 1: Single-Cell Technologies for Resolving Intra-Tumor Heterogeneity

| Omics Layer | Technology | Measured Features | Contribution to ITH Understanding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomic | scDNA-seq, scWGS | SCNAs, SNVs, Structural Variants | Reveals subclonal genomic architectures and mutation orders [26] [25]. |

| Transcriptomic | scRNA-seq | Gene expression, Splicing variants | Identifies functional cell states, phenotypic diversity, and rare cell populations [27] [2]. |

| Epigenomic | scATAC-seq, scBS-seq | Chromatin accessibility, DNA methylation | Uncovers regulatory heterogeneity and cell fate trajectories [23] [24]. |

| Multi-omics | SDR-seq [28], scTrio-seq [23] | Combined DNA & RNA profiles | Links genotype to phenotype within the same cell [28]. |

Clonal Evolution

Clonal evolution is the process by which tumor cells acquire genetic alterations, leading to the selection and expansion of fitter subclones [23]. SCS enables the direct reconstruction of phylogenetic trees and tracking of clonal dynamics over time and in response to therapeutic pressure.

- Inferring Phylogenies: Computational methods like MEDICC2 and COMPASS are used with scDNA-seq data to reconstruct phylogenetic trees based on allele-specific copy-number alterations and SNVs, defining evolutionary relationships between clones [26] [25].

- Tracking Evolution in Real-Time: Clone-specific genomic alterations, particularly structural variants (SVs), serve as highly specific endogenous markers to track the abundance of individual clones over time in cell-free DNA (cfDNA) from patient blood samples. The CloneSeq-SV assay, which combines single-cell whole-genome sequencing (scWGS) with targeted deep sequencing of clone-specific SVs in cfDNA, enables monitoring of clonal population dynamics throughout treatment [26].

- Evolution Under Therapy: SCS studies across cancer types have shown that drug resistance frequently arises from the selective expansion of a minor, pre-existing clone present at diagnosis that harbors resistance mechanisms. At relapse, this often leads to reduced clonal complexity compared to the diagnostic sample [26] [25]. In HGSOC, drug-resistant clones frequently show distinctive genomic features like chromothripsis and whole-genome doubling [26].

Diagram 1: Clonal Evolution Model. A phylogenetic tree showing tumor evolution from a normal cell, through branching evolution creating heterogeneity, culminating in therapy-driven selection of a resistant clone.

Experimental Protocols

This section provides detailed methodologies for profiling ITH and clonal evolution using single-cell approaches.

Protocol: Spatially Annotated scRNA-seq for Profiling ITH in vitro

This protocol combines live-cell imaging with scRNA-seq to link cellular spatial information with transcriptomic heterogeneity in tumor models [29].

- Summary: Identify regions of interest (ROIs) in an in vitro tumor model using live-cell imaging, label selected cells with photoactivatable dyes, and isolate them for deep scRNA-seq.

- Applications: Spatially profile intratumor heterogeneity; investigate the relationship between tumor microenvironments and cell states.

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Sample Preparation: Culture the tumor model (e.g., 3D spheroid or monolayer) in a dish compatible with high-resolution live-cell imaging.

- Live-Cell Imaging and ROI Selection:

- Acquire time-lapse images of the live tumor model to document growth dynamics and morphological heterogeneity.

- Based on imaging data, select up to three distinct ROIs for profiling (e.g., hypoxic core, invasive edge, proliferative region) [29].

- Photoactivation and Cell Labeling:

- Introduce a photoactivatable fluorescent dye (e.g., PA-GFP) into the culture medium.

- Use a photopatterning illumination system to selectively activate the dye only within the predefined ROIs, thereby fluorescently labeling the cells of interest.

- Cell Isolation via FACS:

- Dissociate the tumor model into a single-cell suspension.

- Use Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) to isolate the photoactivated (fluorescently labeled) cells from the non-labeled cells based on their fluorescence signal.

- scRNA-seq Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Process the isolated single cells using a standard scRNA-seq platform (e.g., 10x Genomics).

- Generate barcoded cDNA libraries and perform high-throughput sequencing.

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Perform standard scRNA-seq analysis (quality control, normalization, clustering, differential expression).

- Integrate transcriptional clusters with their spatial ROIs of origin to identify location-associated gene expression programs.

Diagram 2: Spatially Annotated scRNA-seq Workflow. The process from live imaging of a tumor model to the isolation and transcriptional profiling of cells from specific spatial regions.

Protocol: Tracking Clonal Evolution with CloneSeq-SV

This protocol uses single-cell whole-genome sequencing and patient-specific cfDNA profiling to monitor the evolutionary dynamics of cancer clones during treatment [26].

- Summary: Perform scWGS on a pretreatment tumor sample to identify clone-specific structural variants (SVs). Design bespoke cfDNA assays to track these SVs as endogenous biomarkers in serial blood draws.

- Applications: Monitor therapy response and relapse; identify the clonal origins of drug resistance in patients.

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Pretreatment Tissue Processing and scWGS:

- Obtain a fresh tumor sample from a primary debulking surgery or biopsy and dissociate it into a single-cell suspension.

- Perform single-cell whole-genome sequencing (e.g., using the DLP+ platform) on thousands of tumor cells to achieve low-coverage coverage across the genome [26].

- Clonal Decomposition and Marker Identification:

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Infer clonal composition and phylogenetic trees from scWGS data using tools like MEDICC2, based on allele-specific copy-number alterations [26].

- Call SVs: Identify somatic structural variants (translocations, inversions, deletions) from pseudobulk data.

- Genotype SVs in Single Cells: Determine the cellular prevalence of each SV to distinguish truncal (shared by all clones) from clone-specific SVs.

- Probe Design and cfDNA Assay:

- Design a patient-specific hybrid-capture panel targeting the breakpoint sequences of ~50-100 high-confidence, clone-specific SVs.

- Apply this panel to deep, duplex sequencing of cell-free DNA extracted from serial plasma samples collected throughout the patient's treatment course.

- Evolutionary Tracking and Modeling:

- Quantify the variant allele frequency (VAF) of each clone-specific SV in every cfDNA time point.

- Use the VAF dynamics as a proxy for the relative abundance of each clone, modeling the evolutionary trajectory of the tumor under therapeutic selection.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Featured Protocols

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Photoactivatable Dyes | Labels cells in specific spatial regions for subsequent isolation and sequencing. | PA-GFP [29] |

| Hybrid-Capture Probes | Enriches specific genomic loci (e.g., SV breakpoints) from complex DNA mixtures for sensitive detection in cfDNA. | Patient-specific SV panels [26] |

| Multiplexed PCR Panels | Amplifies a targeted set of genomic DNA loci and RNA transcripts from thousands of single cells. | SDR-seq panels [28] |

| Cell Barcoding Beads | Labels nucleic acids from individual cells with a unique barcode during droplet-based sequencing. | 10x Genomics Barcoded Beads [2] |

Data Analysis and Computational Methods

The power of SCS is realized through sophisticated computational pipelines that transform raw sequencing data into biological insights.

- Inferring CNAs from scRNA-seq: A key step in identifying malignant cells from scRNA-seq data is the inference of copy-number alterations (CNAs). Tools like InferCNV, CopyKAT, and CaSpER calculate smoothed expression of genes along chromosomal coordinates and compare this profile to a reference of diploid cells (e.g., immune cells) to predict regions of amplification or deletion [27]. Methods that exploit allelic shift signals (Numbat, CaSpER) show superior performance, while CopyKAT is recommended when only expression matrices are available [27].

- Constructing Phylogenies from scDNA-seq: Tools like COMPASS and MEDICC2 use single-cell genomic data to reconstruct phylogenetic trees. COMPASS utilizes reference and alternative allele counts from targeted scDNA-seq to build trees, while MEDICC2 performs phylogeny inference based on whole-genome copy-number profiles, enabling the visualization of clonal relationships and evolutionary trajectories [26] [25].

- Multi-Omic Integration: Advanced computational methods are essential for integrating data across omics layers. The sciCAR algorithm jointly profiles chromatin accessibility and gene expression to link cis-regulatory sites to their target genes, while REAP-Seq and CITE-Seq enable the simultaneous analysis of cellular protein markers and the transcriptome [23].

Applications in Drug Discovery and Development

Understanding ITH and clonal evolution through SCS directly informs and enhances drug discovery and development pipelines [30] [24].

- Identifying Biomarkers of Response and Resistance: scRNA-seq of tumor biopsies taken before, during, and after treatment can reveal transcriptional programs associated with drug sensitivity or resistance. For example, in melanoma patients treated with checkpoint inhibitors, scRNA-seq identified a T cell state similar to stem-cell-like memory CD8 T cells that was enriched in responders, and a dysfunctional/exhausted T cell state common in resistant tumors [23] [24].

- Uncovering Mechanisms of Resistance: SCS can pinpoint pre-existing or acquired genomic and non-genomic mechanisms of resistance. In a study of HGSOC, CloneSeq-SV revealed that resistant clones frequently had pre-existing interpretable genomic features (e.g., CCNE1 amplification) and phenotypic states (e.g., upregulation of EMT pathways) present at diagnosis [26].

- Guading Personalized Combination Therapies: By identifying the specific drivers of a dominant resistant clone, SCS can inform rational combination therapies. In one notable case of HGSOC, the discovery of clone-specific ERBB2 amplification guided the use of a secondary targeted therapy, leading to a positive patient outcome [26]. Tracking clonal dynamics in cfDNA also opens the possibility for evolution-informed adaptive treatment regimens to preempt or ablate resistance [26].

Single-cell sequencing provides an indispensable toolkit for dissecting the fundamental hallmarks of intra-tumor heterogeneity and clonal evolution. The protocols and applications detailed herein empower researchers and drug developers to move beyond bulk tissue averages and confront the complex, dynamic nature of cancer. By integrating these high-resolution approaches into preclinical and clinical studies, the field can accelerate the development of targeted strategies that anticipate and overcome tumor evolution, ultimately improving outcomes for cancer patients.

From Bench to Bioinformatics: Core SCS Technologies and Their Translational Applications in Cancer

In the field of cancer research, single-cell sequencing has emerged as a transformative technology for dissecting tumor heterogeneity, understanding the tumor microenvironment, and identifying rare cell populations such as cancer stem cells. The journey from a complex tumor tissue to actionable sequencing data requires a meticulously planned and executed workflow. This application note provides a detailed breakdown of the essential steps, from initial cell capture using technologies like 10x Genomics and Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS), through library preparation, to final sequencing. A robust single-cell workflow enables researchers to profile gene expression, identify clonal evolution, and characterize tumor-immune cell interactions at unprecedented resolution, ultimately accelerating drug discovery and development of personalized cancer therapies.

Core Single-Cell Sequencing Workflow

The standard single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) workflow involves a series of interconnected steps where sample quality at each stage is paramount to the success of the final data output. The following diagram illustrates the key stages from sample collection to data analysis.

Sample Preparation and Cell Capture

Initial Cell Preparation

The foundation of a successful single-cell experiment is a high-quality single-cell suspension. For tumor samples, this often involves mechanical dissociation and enzymatic digestion to break down the extracellular matrix while preserving cell viability [6] [31]. Key considerations include:

- Viability and Quality: Ideal cell suspensions have >90% viability, minimal debris, and no aggregates [32] [33]. For challenging tumor samples with inherent RNase activity (e.g., pancreatic cancer), include an RNase inhibitor (0.4-1U/μl) in all wash and resuspension buffers [33] [31].

- Buffer Composition: Use calcium- and magnesium-free PBS with 0.04% BSA for final resuspension. Avoid reagents that inhibit reverse transcription, such as high EDTA concentrations (>0.1 mM) or detergents [32] [31].

- Handling: Pipette gently using wide-bore tips to minimize shear forces that can lyse cells and increase background mRNA [33] [31]. Keep samples on ice and use nuclease-free consumables to preserve RNA integrity.

Cell Capture Technologies

Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS)

FACS enables enrichment of specific cell populations from complex tumor samples using fluorescent antibodies or labels, which is particularly valuable for isolating rare cancer stem cells or specific immune populations from the tumor microenvironment [34] [35].

- Applications: Pre-enrichment of target populations (e.g., CD45+ immune cells, EpCAM+ epithelial cells); removal of dead cells using viability dyes (DAPI, 7-AAD) [34] [31].

- Best Practices: Use larger nozzle sizes (e.g., 100 μm) to minimize shear stress; sort directly into collection tubes containing RNase-free buffer with RNase inhibitor; keep sorted samples on ice and process as quickly as possible to maintain RNA integrity [34] [31].

- Limitations: Subjects cells to shear forces, potentially reducing viability; requires a large number of cells as initial input; fluorescent staining can introduce biases [35].

10x Genomics Chromium Platform

The 10x Genomics Chromium system uses droplet-based microfluidics to encapsulate single cells in gel beads-in-emulsion (GEMs), where each gel bead contains oligonucleotides with unique cell barcodes, Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs), and poly(dT) sequences for mRNA capture [32] [36].

- Workflow: Single cells are combined with barcoded gel beads and partitioning oil to form GEMs. Within each GEM, cells are lysed, and mRNA transcripts are barcoded during reverse transcription [32].

- Throughput: The Chromium X can generate hundreds of thousands of single-cell partitions, making it suitable for profiling heterogeneous tumor ecosystems [36].

- Input Requirements: Ideal input is 100,000-150,000 cells at a concentration of 1,000-1,600 cells/μL [32] [31].

Table 1: Comparison of Cell Capture Methods for Single-Cell RNA Sequencing

| Parameter | FACS | 10x Genomics Chromium | Precision Microdispensing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Throughput | Medium to High | Very High (hundreds of thousands of cells) | Scalable (hundreds to thousands of genomes) [35] |

| Cell Input Requirements | High [35] | 100,000-150,000 cells recommended [32] | Low sample volumes (~3 μL) [35] |

| Viability Impact | Reduced viability due to shear forces [35] | Minimal when starting with healthy suspension | Gentle handling maintains viability [35] |

| Sorting Capability | Yes, based on fluorescence | No, random encapsulation | Yes, image-based with optional fluorescence [35] |

| Best For | Pre-enrichment of rare populations, dead cell removal [34] | Large-scale profiling of heterogeneous samples | Rare cells, low input samples, minimizing reagent costs [35] |

Library Preparation Strategies

10x Genomics Library Chemistry

10x Genomics offers different library preparation kits tailored to specific research questions in cancer biology. The choice between 3' and 5' gene expression kits depends on the biological questions being addressed.

Table 2: 10x Genomics Single-Cell Kits for Cancer Research Applications

| Kit Type | Capture Method | Key Applications in Cancer Research | Special Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single Cell 3' Gene Expression | PolyA-based capture at 3' end | Differential gene expression analysis, tumor heterogeneity studies [32] | "Feature barcoding" for cell surface protein (CITE-seq) and sample multiplexing [32] |

| Single Cell 5' Gene Expression/ Immune Profiling | Template-switching reverse transcription at 5' end | Immune repertoire profiling, T-cell/B-cell receptor sequencing in tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes [32] | Add-on module for V(D)J sequencing; CRISPR screening [32] |

| Single Nucleus Multiome ATAC + Gene Expression | Simultaneous capture of mRNA polyA tails and transposed DNA | Parallel analysis of gene expression and chromatin accessibility in tumor nuclei [32] | Reveals regulatory mechanisms driving cancer phenotypes [32] |

Library Construction Fundamentals

The library preparation process converts captured RNA into sequencer-compatible libraries through several key steps:

- Reverse Transcription: Within each GEM, polyadenylated mRNA is reverse-transcribed using barcoded primers, creating cDNA tagged with cell barcodes and UMIs [32].

- cDNA Amplification: The cDNA is amplified by PCR to generate sufficient material for library construction [32].

- Library Construction: Fragmentation and addition of Illumina adapter sequences (P5/P7) and sample indexes (i5/i7) are performed [32]. For 5' gene expression kits, template switching enables capture of the 5' end of transcripts, which is crucial for immune repertoire analysis [32].

The following diagram details the structure of a final sequencing library, highlighting the functional elements added during preparation.

Sequencing and Data Analysis

Sequencing Platform Considerations

The choice of sequencing platform depends on the research goals, with key considerations including:

- Short-Read vs. Long-Read Sequencing: Short-read sequencing (Illumina) is highly accurate for base-calling, making it suitable for single-nucleotide variant detection and gene expression quantification. Long-read sequencing (PacBio) is more effective for identifying structural variants, fusion genes, and full-length immune receptor sequences [35].

- Sequencing Depth: For 10x Genomics 3' gene expression, a sequencing depth of 20,000-50,000 reads per cell is typically recommended, though this varies based on project scope and cell type complexity [36].

- Quality Control: An initial QC run on instruments like the Element AVITI verifies the number of targeted single cells before full-scale sequencing [36].

Bioinformatic Analysis and Experimental Design

The initial data processing for 10x Genomics datasets typically uses the Cell Ranger Count pipeline, which performs sample demultiplexing, barcode processing, and UMI counting to generate a gene-cell expression matrix [36]. A critical consideration for cancer research studies is proper experimental design with biological replicates. Treating individual cells as replicates constitutes a statistical error called "pseudoreplication," which dramatically increases false positive rates in differential expression analysis [32]. Instead, researchers should employ "pseudobulking" approaches that account for between-sample variation by performing traditional differential expression testing on summed or averaged read counts within samples for each cell type [32].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Single-Cell RNA Sequencing

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| PBS with 0.04% BSA | Cell resuspension buffer | Recommended by 10X Genomics for final cell resuspension; calcium- and magnesium-free to prevent inhibition of reverse transcription [32] [31] |

| RNase Inhibitor | Protects RNA integrity | Critical for RNase-rich tissues (e.g., pancreas, spleen) and nuclei preparations; use at 0.4-1U/μl in buffers [33] [31] |

| Viability Dyes (DAPI, 7-AAD) | Dead cell exclusion | Used during FACS to remove dead cells which can increase background RNA [31] |

| Dead Cell Removal Kit | Viability enrichment | Magnetic bead-based cleanup (e.g., Miltenyi) for samples with low viability after thawing cryopreserved cells [31] |

| Flowmi Tip Strainers (40 μm) | Debris and aggregate removal | Filters cell suspensions before loading; minimizes clogging of microfluidic chips [31] |

| 10x Genomics Barcoded Gel Beads | Cell barcoding and mRNA capture | Contains cell barcode, UMI, and poly(dT) for transcript capture in GEMs [32] |

| Single Cell 3' or 5' Kit | Library preparation | Choice depends on research focus: 3' for gene expression, 5' for immune profiling [32] |

| Chromium X Chip | Microfluidic partitioning | Creates GEMs for single-cell barcoding [36] |

Troubleshooting and Quality Control

Common challenges in single-cell workflows include poor cell viability, low capture efficiency, and high background signal. To address these:

- Low Viability: For samples with viability below 90%, implement dead cell removal strategies using magnetic bead-based kits or FACS sorting with viability dyes [31].

- Cell Aggregation: Filter suspensions through 40 μm Flowmi tip strainers before loading; avoid excessive centrifugation and resuspend pellets thoroughly but gently [31].

- Inhibitor Contamination: Ensure thorough washing of cell suspensions to remove reagents that inhibit reverse transcription (e.g., EDTA, detergents) [6] [33].

- Nuclei Preparations: For frozen tumor samples where cell viability is compromised, nuclei isolation is a robust alternative. Always include RNase inhibitor in nuclei preparations and verify quality by microscopy [31].

A robust single-cell sequencing workflow from cell capture to library preparation is essential for generating high-quality data in cancer research. By carefully selecting appropriate capture methods (FACS for enrichment, 10x Genomics for large-scale profiling), optimizing sample preparation, and following best practices for library construction, researchers can successfully navigate the complexities of tumor heterogeneity. This detailed protocol provides the foundation for reliable single-cell studies that can uncover novel biological insights into cancer biology, with potential applications in biomarker discovery, drug development, and personalized medicine approaches.

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized our understanding of tumor ecosystems by revealing their profound cellular heterogeneity [27] [37]. A pivotal challenge in the analysis of scRNA-seq data from tumor samples is the accurate distinction of malignant cells from the diverse non-malignant immune and stromal cells in the tumor microenvironment (TME), and particularly from normal cells of the same lineage [27]. This precise identification is a critical prerequisite for downstream analyses aimed at understanding tumor biology, metastasis, and therapy resistance [37]. Two cornerstone strategies for identifying malignant cells are the use of cell-of-origin (COO) marker genes and the computational inference of copy number alterations (CNAs) from transcriptomic data [27]. This Application Note details integrated experimental and computational protocols for robust malignant cell identification, framed within the context of a broader thesis on single-cell sequencing in cancer research. It is designed to provide researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a practical framework for implementing these strategies in their own work.

Core Principles and Hallmarks of Malignant Cells

Malignant cells are defined by a set of molecular aberrations that manifest as observable transcriptional phenotypes [27]. The two primary features leveraged for their identification are:

- Cell-of-Origin Markers: The "cell of origin" refers to the normal cell type that underwent malignant transformation (e.g., epithelial cells for carcinomas) [27]. Expression of marker genes specific to this lineage (e.g., EPCAM for epithelial cells, MZB1 for plasma cells) is a first-line approach to isolate the broad cellular compartment from which the tumor arose [27]. However, this method alone is insufficient, as tumors often contain non-malignant cells of the same lineage, and cancer cells may undergo epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), downregulating typical epithelial markers [27].

- Somatic Copy Number Alterations (CNAs): CNAs, including the gain or loss of genomic DNA segments, are a hallmark of cancer, present in an estimated 90% of solid tumors [27] [38]. These alterations can amplify oncogenes or silence tumor suppressor genes. The fundamental premise for their inference from scRNA-seq data is that genes located in amplified genomic regions tend to show elevated expression, while genes in deleted regions show reduced expression, relative to a diploid baseline [38]. This creates detectable patterns of expression variation across chromosomes that can be computationally deciphered.

The most robust strategy involves a sequential application of these two principles: first, using COO markers to isolate the lineage-specific compartment, and second, applying CNA inference tools to that compartment to distinguish malignant from non-malignant cells [27].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for integrating these strategies to identify malignant cells from a complex tumor sample.

Computational Toolkit for CNA Inference

Several computational methods have been developed to infer CNAs from scRNA-seq data. These tools can be broadly categorized into those that use only gene expression information and those that integrate allelic frequency information from single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) for more robust calls [38]. The table below summarizes the key features of popular tools.

Table 1: Benchmarking of scRNA-seq CNA Inference Tools

| Tool | Primary Algorithm | Data Input | Key Features | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| InferCNV [27] | Hidden Markov Model (HMM) | Gene Expression | Compares smoothed expression against a reference; widely used for subclone identification [39]. | Good subclone identification; performance highly dependent on reference quality [39]. |

| CopyKAT [27] [38] | Gaussian Mixture Model & Segmentation | Gene Expression | Automatically identifies "confident normal" cells to set a baseline; good for aneuploid tumors [27]. | Among the best overall performers for expression-only methods; good sensitivity/specificity [38] [39]. |

| SCEVAN [27] [38] | Joint Segmentation Algorithm | Gene Expression | Automatically classifies malignant and non-malignant cells based on CNA profiles [40]. | High specificity reported in some studies [41]. |

| CaSpER [27] [38] | HMM & Signal Processing | Gene Expression + Allelic Shift | Integrates expression with allelic imbalance signals for improved accuracy [27]. | Robust performance in large datasets; superior with allelic information [38] [39]. |

| Numbat [27] [38] | HMM | Gene Expression + Haplotype | Leverages haplotype phasing and allelic imbalance to support CNA calls [27]. | High performance with allelic information; requires higher runtime [38]. |

Recent independent benchmarking studies, which evaluated tools on datasets with orthogonal ground truth from whole-genome or whole-exome sequencing, have found that methods integrating allelic information (e.g., CaSpER, Numbat) generally perform more robustly, particularly for large droplet-based datasets [38] [39]. When only gene expression matrices are available, CopyKAT is often the recommended method [38]. It is critical to note that these tools can exhibit significant discordance, and their performance is not universal but depends on factors like sequencing platform, data quality, and cancer type [40] [41].

Detailed Application Protocol

This section provides a step-by-step protocol for identifying malignant cells in a carcinoma sample, integrating both COO markers and CNA inference.

Experimental Workflow and Reagent Solutions

The following diagram outlines the comprehensive workflow, from wet-lab sample processing to computational analysis.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

| Item | Function/Application | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Tissue Dissociation Kit | Enzymatic and mechanical dissociation of solid tumor tissue into single-cell suspensions. | Commercial kits (e.g., Miltenyi Biotec Tumor Dissociation Kits); optimize enzymes (collagenase, hyaluronidase) for tissue type [41]. |

| Viability Stain | Distinguish live cells for sequencing. | Propidium Iodide (PI) or DAPI for exclusion; Fluorescent dyes for FACS. |

| scRNA-seq Platform | High-throughput single-cell transcriptome profiling. | 10x Genomics Chromium (high throughput), Fluidigm C1 (full-length), Smart-seq2 (plate-based, high sensitivity) [37]. |

| Cell Annotation Tool | Computational classification of cell types from scRNA-seq data. | SingleR [40], Seurat, Scanny; uses reference atlases (e.g., HumanPrimaryCellAtlasData). |

| COO Marker Gene Panel | Identify the lineage-specific cell compartment. | EPCAM, KRTs (epithelial/carcinoma); MZB1, SDC1 (plasma/myeloma); COL1A1 (mesenchymal/sarcoma) [27]. |

| CNA Inference Software | Detect copy number alterations from scRNA-seq expression matrices. | See Table 1. Reference cells (e.g., immune cells from the same sample) are a critical input [27] [38]. |

| Orthogonal Validation Assay | Confirm predicted CNAs and malignant cells. | Paired bulk or single-cell Whole Genome/Exome Sequencing (WGS/WES) [27] [39]. |

Step-by-Step Computational Protocol

Step 1: Data Pre-processing and Quality Control

- Process raw sequencing data (BCL files) using the platform-specific software (e.g., Cell Ranger for 10x Genomics) to generate a gene expression count matrix [40] [41].

- Import the matrix into an analysis environment (e.g., R/Python). Perform rigorous QC: filter out cells with low unique gene counts (<200-500 genes) or high mitochondrial gene content (>10-20%), which indicates dead or dying cells [40].

- Normalize the data to account for sequencing depth and scale for dimensional reduction.

- Perform clustering (e.g., Louvain) and visualization (e.g., UMAP) to get an initial view of cellular heterogeneity.

Step 2: Initial Cell Annotation and COO Compartment Isolation

- Annotate broad cell types using a reference-based classifier (e.g., SingleR) and/or canonical marker genes:

- Subset the dataset to create a new object containing only the cells expressing the relevant COO markers (e.g., the epithelial compartment for a carcinoma). This step removes most immune and stromal cells, simplifying the subsequent CNA analysis.

Step 3: Inference of Copy Number Alterations

- Select a CNA inference tool (see Table 1) based on your data and needs. For this protocol, we will use InferCNV as a widely adopted example.

- Prepare Inputs:

- Query Matrix: The gene expression matrix of the COO+ compartment.

- Reference Cells: A set of cells known to be diploid. The best practice is to use confident normal cells from the same sample, such as annotated immune cells (e.g., T cells, B cells) [27] [38]. If unavailable, an external dataset of matching normal cells can be used, though this may introduce noise.

- Gene Annotation File: A file mapping genes to their chromosomal positions.

- Run InferCNV:

- The algorithm will smooth expression values across genomic windows for each cell and compare them to the reference.

- It uses an HMM to predict states of loss, gain, or neutral copy number across the genome [27].

- Use the default or recommended parameters for the initial run (e.g.,

cutoff=0.1for defining CNA gains/losses).