RT-qPCR in Liquid Biopsy: A Comprehensive Guide for Cancer Detection and Monitoring

This article provides a detailed examination of Reverse Transcription Quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) for liquid biopsy applications in oncology, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

RT-qPCR in Liquid Biopsy: A Comprehensive Guide for Cancer Detection and Monitoring

Abstract

This article provides a detailed examination of Reverse Transcription Quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) for liquid biopsy applications in oncology, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of detecting circulating biomarkers like mRNA and microRNA in blood and bone marrow. The content delves into advanced methodological workflows, from sample collection to data analysis, and addresses key troubleshooting and optimization challenges for sensitive minimal residual disease (MRD) detection. Finally, it critically validates RT-qPCR performance against other technologies and through large-scale clinical studies, offering a roadmap for its integration into precision medicine and future cancer diagnostics.

The Foundation of RT-qPCR in Liquid Biopsy: Principles and Biomarker Discovery

Liquid biopsy has emerged as a transformative approach in oncology, providing a minimally invasive alternative to traditional tissue biopsies for cancer detection, monitoring, and treatment selection. This technical guide explores the core components of liquid biopsy—including circulating tumor cells (CTCs), circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), and extracellular vesicles (EVs)—and their applications within cancer research and clinical practice. By enabling real-time monitoring of tumor dynamics and overcoming the limitations of tissue biopsy, liquid biopsy represents a paradigm shift in cancer management. Particular emphasis is placed on the role of RT-qPCR methodologies in advancing liquid biopsy applications, with detailed experimental protocols and reagent solutions provided for research implementation.

Liquid biopsy represents a minimally invasive approach for analyzing tumor-derived components from peripheral blood or other bodily fluids. Unlike traditional tissue biopsy, which remains the gold standard for tumor diagnosis due to high laboratory standardization and accuracy, liquid biopsy provides distinct advantages including non-invasive sampling, capability for repeated monitoring, and comprehensive representation of tumor heterogeneity [1]. The concept has evolved through four distinct developmental phases: the period of scientific exploration (before the 1990s), scientific development (1990s), industrial growth (2000-2010), and industrial outbreak (2010-present) [1].

The foundational discoveries underlying liquid biopsy date back to 1869 when Australian physician Thomas Ashworth first observed cells resembling tumor cells in the blood of a deceased cancer patient [1]. In 1948, Mandel and Metais made the groundbreaking discovery of cell-free nucleic acids in plasma, followed by Leon et al.'s 1977 observation that plasma-free DNA levels were significantly elevated in cancer patients compared to healthy individuals [1]. The modern era of liquid biopsy began with the first isolation of CTCs from blood in 1998, demonstrating correlation with pathological staging, and the 1994 identification of KRAS mutations in pancreatic cancer patients' blood cfDNA that matched tumor tissue findings [1]. The field has since accelerated rapidly, with regulatory approvals including the 2014 EMA authorization of ctDNA for EGFR mutation detection in non-small cell lung cancer and the 2018 incorporation of CTC testing into AJCC guidelines for breast cancer prognostic assessment [1].

Key Biomarkers in Liquid Biopsy

Circulating Tumor Cells (CTCs)

CTCs are cells released from primary and metastatic tumors that enter the bloodstream or lymphatic circulation [1]. Although extremely rare in peripheral blood (approximately 1 CTC per 1 million leukocytes), with most surviving only 1-2.5 hours in circulation, CTCs provide vital information about cancer biology and metastatic potential [1]. The detection and analysis of CTCs face significant technical challenges due to their scarcity, requiring highly sensitive capture methodologies including density gradient centrifugation, immunomagnetic separation (such as the FDA-approved CellSearch system), and microfluidic devices targeting surface markers like epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM), vimentin, and N-cadherin [1]. Clinically, CTC enumeration has demonstrated prognostic value, with higher counts correlating with reduced progression-free survival and overall survival in multiple cancer types [1].

Circulating Tumor DNA (ctDNA)

CtDNA comprises tumor-derived fragmented DNA circulating in bloodstream, typically representing 0.1-1.0% of total cell-free DNA (cfDNA) [1]. Unlike cfDNA from normal leukocytes and stromal cells, ctDNA fragments are shorter (approximately 20-50 base pairs) and exhibit a shorter half-life, enabling real-time monitoring of tumor dynamics [1]. CtDNA can be isolated from various sources including blood, ascites, pleural fluid, urine, and cerebrospinal fluid, providing flexibility in sampling approaches [1]. The detection of tumor-specific genetic alterations in ctDNA, such as mutations in APC, KRAS, TP53, and PIK3CA genes, allows for monitoring of treatment response and disease progression, as demonstrated in studies of colorectal cancer patients where ctDNA mutation rates correlated with therapeutic response [1].

Extracellular Vesicles (EVs) and Other Biomarkers

Extracellular vesicles, including exosomes, represent membrane-bound particles released by cells that carry molecular cargo including proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids [1]. First observed in 1967 and characterized as exosomes in 1983, EVs have demonstrated biological activity including antigen presentation capabilities [1]. Beyond CTCs, ctDNA, and EVs, the liquid biopsy biomarker landscape includes microRNAs, circulating free RNA (cfRNA), tumor-educated platelets (TEPs), and tumor endothelial cells, creating a multi-parametric approach to cancer detection and monitoring [2]. Each biomarker class offers complementary information, with integrated approaches demonstrating enhanced sensitivity and specificity for disease monitoring [2].

Table 1: Comparison of Major Liquid Biopsy Biomarkers

| Biomarker | Composition | Primary Sources | Key Features | Research Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTCs | Intact tumor cells | Peripheral blood | Rare population (1 per 10^6 WBCs), short half-life (1-2.5 hours) | Prognostic assessment, metastasis research, drug response monitoring |

| ctDNA | Tumor-derived DNA fragments | Blood, urine, CSF, ascites | Short fragments (20-50 bp), 0.1-1.0% of total cfDNA | Mutation detection, treatment response monitoring, MRD assessment |

| EVs/Exosomes | Membrane-bound vesicles with molecular cargo | Blood, urine | Stable in circulation, carry proteins, RNA, DNA | Biomarker discovery, intercellular communication studies |

| cfRNA | Cell-free RNA including mRNA, miRNA | Blood, urine | Reflects gene expression patterns | Gene expression profiling, treatment response biomarkers |

Current Applications and Recent Advances

Liquid biopsy applications span the cancer care continuum, from early detection to monitoring treatment response and disease recurrence. Recent research presented at the AACR Annual Meeting 2025 highlights significant advancements in three primary areas: screening/detection, minimal residual disease (MRD) monitoring, and prediction/prognostication [3].

Screening, Detection, and Diagnosis

Multi-cancer early detection (MCED) platforms represent one of the most promising applications of liquid biopsy. The Vanguard Study, part of the NCI Cancer Screening Research Network, demonstrated feasibility of implementing MCED tests in real-world settings, enrolling over 6,200 participants with high adherence across diverse populations [3]. Technological advances include methylation-based approaches, with one hybrid-capture methylation assay demonstrating 98.5% specificity and 59.7% overall sensitivity (increasing to 84.2% in late-stage tumors) [3]. Fragmentomics approaches using low-coverage whole genomic sequencing have shown remarkable accuracy in detecting liver conditions, distinguishing cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma from healthy states with an AUC of 0.92 in a 724-person cohort [3]. Additionally, proteomic analyses within the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) cohort identified 19 circulating plasma proteins associated with premenopausal breast cancer risk and three proteins (LEG1, CST6, SAR1B) with postmenopausal risk, enabling improved risk stratification [3].

Minimal Residual Disease (MRD) Monitoring

MRD detection through liquid biopsy provides critical insights into treatment efficacy and early recurrence detection. In colorectal cancer, the VICTORI study demonstrated that 87% of recurrences were preceded by ctDNA positivity, while no ctDNA-negative patients relapsed [3]. In bladder cancer, the TOMBOLA trial compared ddPCR and whole-genome sequencing for ctDNA detection in 1,282 paired plasma samples, revealing 82.9% concordance between methods, with ddPCR showing higher sensitivity in low tumor fraction samples [3]. Novel technologies such as MUTE-Seq (Mutation tagging by CRISPR-based Ultra-precise Targeted Elimination in Sequencing) enable ultrasensitive detection of low-frequency mutations in cfDNA through engineered advanced-fidelity FnCas9, significantly improving sensitivity for MRD evaluation in NSCLC and pancreatic cancer [3].

Prediction and Prognostication

Liquid biopsy biomarkers demonstrate significant utility for predicting treatment response and patient prognosis. In metastatic prostate cancer, morphological evaluation of chromosomal instability in CTCs (CTC-CIN) from the CARD trial showed that high baseline CTC-CIN counts were significantly associated with worse overall survival, while low CTC-CIN predicted greater benefit from cabazitaxel treatment [3]. Combined tissue and liquid biopsy approaches have demonstrated improved outcomes, with an exploratory analysis of the ROME trial showing that despite only 49% concordance between modalities, combining both significantly increased detection of actionable alterations and improved survival outcomes in patients receiving tailored therapy [3]. In NSCLC, baseline detection of EGFR mutations in plasma, particularly at variant allele frequency >0.5%, was prognostic for significantly shorter PFS and OS in patients treated with osimertinib [3].

Table 2: Recent Advancements in Liquid Biopsy Applications (AACR 2025 Highlights)

| Application Area | Study/Technology | Cancer Type | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early Detection | Vanguard Study | Multi-cancer | Established feasibility in 6,200 participants; high adherence across diverse populations |

| Early Detection | MCED Methylation Assay | Multi-cancer | 98.5% specificity, 59.7% overall sensitivity (84.2% in late-stage tumors) |

| MRD Monitoring | VICTORI Study | Colorectal Cancer | 87% of recurrences preceded by ctDNA positivity; no ctDNA-negative patients relapsed |

| MRD Monitoring | MUTE-Seq | NSCLC, Pancreatic | Ultrasensitive detection of low-frequency mutations via engineered FnCas9 |

| Prediction/Prognosis | CTC-CIN Analysis | Metastatic Prostate | High CTC chromosomal instability associated with worse OS; predicts taxane benefit |

| Prediction/Prognosis | ROME Trial Analysis | Advanced Solid Tumors | Combined tissue/liquid biopsy increased actionable alterations detection and improved survival |

RT-qPCR Methodologies in Liquid Biopsy Analysis

Experimental Workflow for Multi-Parametric Liquid Biopsy Analysis

Reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) represents a cornerstone technology for analyzing gene expression patterns in liquid biopsy components, particularly CTCs and EVs. A comprehensive protocol for longitudinal multi-parametric liquid biopsy analysis involves blood collection, component separation, nucleic acid isolation, and molecular analysis [2].

Sample Collection and Processing: Approximately 18mL of blood is collected in EDTA tubes and stored briefly at 4°C before processing. CTCs are isolated via positive immunomagnetic selection targeting surface markers including EpCAM, EGFR, and HER2. The remaining blood undergoes centrifugation at 1841× g for 8 minutes to obtain plasma, which is stored at -80°C. EVs are isolated from 4mL of prefiltered (0.8µm pore size) plasma using affinity-based binding to spin columns. Cell-free DNA is isolated from plasma using affinity-based binding to magnetic beads, with quantification performed via chip-based systems assessing fragments between 100-700bp [2].

RNA Isolation and cDNA Synthesis: Total RNA is isolated from EVs using commercial kits, while mRNA is isolated from CTC lysates and vesicular RNA eluates using Oligo(dT)25 beads followed by reverse transcription to generate cDNA [2].

RT-qPCR Analysis: Multi-marker RT-qPCR is performed using customized panels targeting cancer-relevant transcripts (e.g., AKT2, ALK, AR, AURKA, BRCA1, EGFR, ERCC1, ERBB2, ERBB3, KIT, KRT5, MET, MTOR, NOTCH1, PARP1, PIK3CA, SRC). The process involves transcript-specific multiplex pre-amplification followed by SYBR green-based qPCR in single-plex reactions. Melting curve analysis ensures amplicon specificity, with controls for PCR inhibition and contamination. Data evaluation normalizes transcripts not exclusively expressed in CTCs to the leukocyte-specific CD45 transcript, with expression data normalized to healthy donor controls and analyzed binarily (overexpression yes/no) [2].

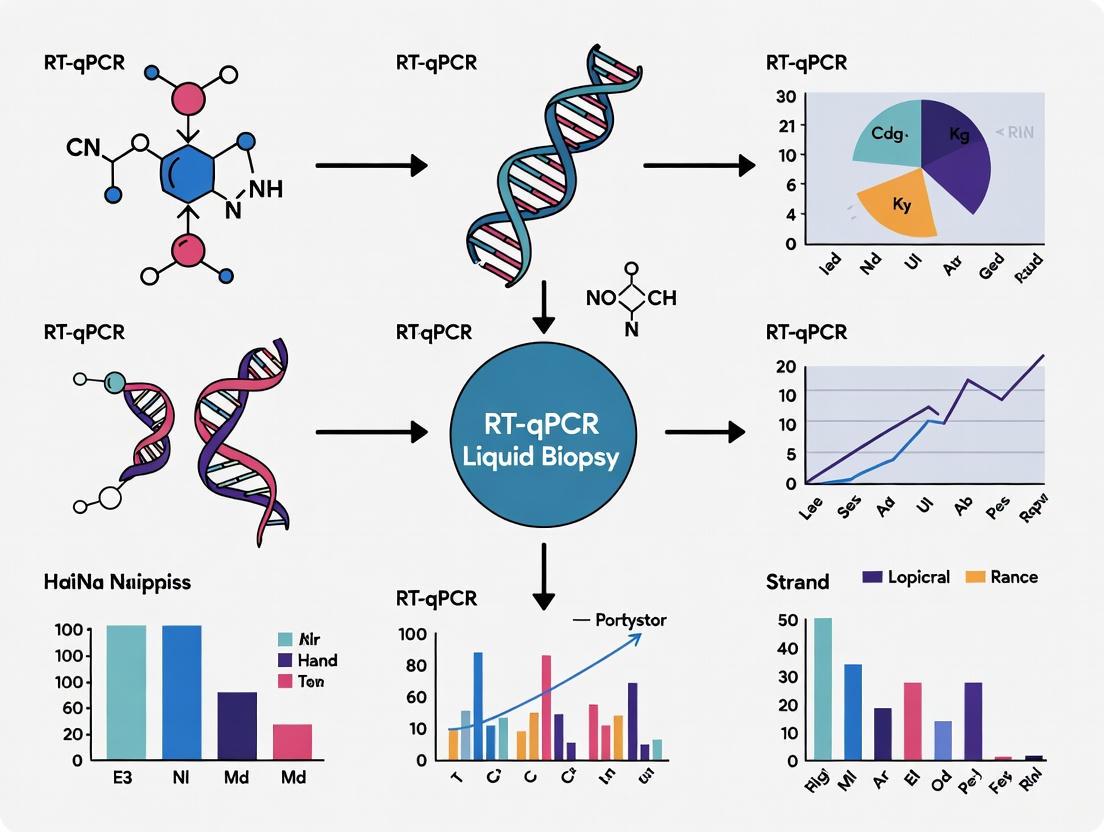

Diagram 1: Multi-Parametric Liquid Biopsy Workflow

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Liquid Biopsy RT-qPCR Analysis

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blood Collection Tubes | EDTA tubes | Prevents coagulation and preserves blood components | Process within 4 hours of collection; store at 4°C |

| CTC Isolation Kits | AdnaTest EMT-2/StemCell Select | Immunomagnetic selection targeting EpCAM, EGFR, HER2 | Enriches tumor cells while depleting hematopoietic cells |

| EV Isolation Kits | exoRNeasy Kit | Affinity-based binding to spin columns | Prefiltration (0.8µm) removes larger particles; preserves EV integrity |

| RNA Extraction Kits | exoRNeasy Kit, QIAamp MinElute | Isolation and purification of nucleic acids | Oligo(dT)25 beads for mRNA selection from CTCs and EVs |

| Reverse Transcription Kits | AdnaTest EMT-2/StemCell Detect | cDNA synthesis from mRNA templates | Includes necessary controls for reaction efficiency |

| qPCR Master Mixes | SYBR green-based systems | Amplification and detection of target sequences | Enables melting curve analysis for amplicon verification |

| Gene Expression Panels | AdnaTest TNBC Panel prototype | Multi-marker analysis of cancer-relevant transcripts | Analyzes 17+ transcripts including AKT2, ALK, AR, AURKA, BRCA1, EGFR |

| Quality Controls | Artificial RNA spikes, negative controls | Monitoring PCR inhibition and contamination | Essential for validating assay performance and specificity |

Data Analysis and Interpretation

For CTC and EV mRNA profiling, data evaluation follows established protocols where transcripts not exclusively expressed in CTCs are normalized to the leukocyte-specific CD45 transcript. Patient expression data is normalized to matched healthy donor controls, with signals analyzed binarily (overexpression present/absent) [2]. In cfDNA analysis, targeted next-generation sequencing panels assess mutational status in key cancer genes, with variant allele frequency (VAF) dynamics providing insights into treatment response and resistance mechanisms [2]. A longitudinal study in metastatic breast cancer demonstrated that fluctuations in EV ERCC1 signals correlated with progressive disease (97% specificity), while allele frequency developments of ESR1 and PIK3CA variants predicted therapy success and could guide treatment decisions [2].

Diagram 2: Liquid Biopsy Data Analysis Pathway

Liquid biopsy has fundamentally expanded the diagnostic and monitoring capabilities in oncology, offering solutions to longstanding limitations of tissue biopsy. The multi-analyte approach—encompassing CTCs, ctDNA, EVs, and other biomarkers—provides complementary information that enables comprehensive assessment of tumor dynamics. RT-qPCR methodologies represent robust, accessible tools for implementing liquid biopsy analyses in research settings, particularly for gene expression profiling in CTCs and EVs. As technological innovations continue to enhance the sensitivity and specificity of liquid biopsy platforms, and as standardized protocols emerge for clinical implementation, these approaches promise to further transform cancer management through personalized, dynamic monitoring of disease progression and treatment response.

Reverse Transcription Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-qPCR) is a cornerstone molecular technique that enables the sensitive, specific, and quantitative detection of RNA targets. This guide details the core principles of RT-qPCR, from its fundamental workflow and chemistry to its critical data analysis methods. Framed within the context of liquid biopsy for cancer research, we explore how this powerful technique is employed to detect and quantify minute amounts of tumor-derived nucleic acids, such as circulating tumor RNA, facilitating advancements in cancer diagnosis, monitoring, and personalized therapy.

Reverse Transcription Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-qPCR) is a powerful molecular technique that combines the reverse transcription of RNA into complementary DNA (cDNA) with the simultaneous amplification and quantification of a specific DNA target [4] [5]. It has become an indispensable tool in molecular biology and clinical diagnostics, particularly in the field of cancer research using liquid biopsies.

The process begins with RNA extracted from a biological sample, such as blood plasma in a liquid biopsy. This RNA, which may include circulating tumor RNA or other cancer-associated transcripts, is first converted into stable cDNA using the enzyme reverse transcriptase [4]. The cDNA then serves as the template for the qPCR step, where a target sequence is amplified exponentially and monitored in real-time using fluorescent reporter molecules [6]. The ability to focus on the exponential phase of the PCR reaction, where amplification is most efficient and consistent, is a key reason for the technique's precision and wide dynamic range [6].

In liquid biopsy-based cancer research, RT-qPCR's exceptional sensitivity allows for the detection of rare RNA biomarkers present in complex biological fluids at low concentrations. Its specificity enables the discrimination of closely related transcripts, such as different splice variants or mutant alleles, while its quantitative nature permits researchers to monitor changes in gene expression or pathogen load over time, providing critical insights into tumor dynamics and treatment response [5] [6].

Core Principles and Workflow

The sensitivity of RT-qPCR stems from the synergistic combination of its two core components: reverse transcription and quantitative PCR. The entire process converts a single RNA molecule into a measurable fluorescent signal.

The Reverse Transcription (RT) Step

The foundational first step is the conversion of RNA into complementary DNA (cDNA). This process requires several key reagents [5]:

- Reverse Transcriptase: The enzyme that synthesizes a DNA strand from an RNA template.

- Primers: Short DNA oligonucleotides that provide a starting point for synthesis. The choice of primer dictates which RNA populations are converted to cDNA and can influence sensitivity and specificity [4].

- dNTPs: The building blocks (deoxynucleoside triphosphates) for the nascent cDNA strand.

- MgCl₂: Provides magnesium ions, an essential cofactor for reverse transcriptase activity.

- RNase Inhibitors: Protect the often scarce and fragile RNA templates from degradation.

The RT reaction involves a defined series of steps to ensure complete and accurate cDNA synthesis, outlined in the diagram below.

Priming Strategies for cDNA Synthesis

The method used to prime the reverse transcription reaction is a critical factor influencing the scope and specificity of the resulting cDNA pool, which is especially important when analyzing diverse RNA populations from liquid biopsies [4]. The common priming strategies are:

- Oligo(dT) Primers: These primers, consisting of a stretch of thymine residues, anneal to the poly(A) tail of messenger RNAs (mRNAs). They are ideal for generating a cDNA library enriched for full-length protein-coding transcripts, making them suitable for gene expression studies of mRNA biomarkers [4] [5].

- Random Primers: These are short (6-9 base) oligonucleotides that anneal at multiple points along any RNA transcript. This allows for the reverse transcription of a broad range of RNAs, including non-coding RNAs, degraded RNA, and transcripts without a poly(A) tail, thereby capturing a more comprehensive snapshot of the transcriptome from a liquid biopsy sample [4] [5].

- Gene-Specific Primers: These custom-designed primers target a specific mRNA sequence of interest. This method provides the highest sensitivity and specificity for the target gene and is often used in one-step RT-qPCR protocols. However, it is limited to pre-selected targets [4] [5].

The Quantitative PCR (qPCR) Step

Following cDNA synthesis, the qPCR step amplifies a specific target sequence and monitors its accumulation in real-time. The reaction mixture contains cDNA template, DNA polymerase, sequence-specific primers, dNTPs, and a fluorescent detection system [5]. The process involves thermal cycling, typically consisting of three steps per cycle: denaturation (to separate DNA strands), annealing (to allow primers to bind), and extension (where DNA polymerase synthesizes new strands) [5]. Fluorescence is measured during each cycle, generating an amplification curve.

The core quantitative output of RT-qPCR is the Cycle Threshold (Ct) value. The Ct is the PCR cycle number at which the fluorescent signal crosses a predefined threshold, which is set above the baseline background fluorescence but within the exponential phase of amplification [7] [6]. The Ct value is inversely proportional to the starting quantity of the target: a low Ct value indicates a high initial amount of target RNA, while a high Ct value indicates a low initial amount [5] [7].

One-Step vs. Two-Step RT-qPCR

RT-qPCR can be performed using either a one-step or a two-step approach, each with distinct advantages and applications, particularly in a diagnostic or high-throughput setting.

- One-Step RT-qPCR: The reverse transcription and qPCR reactions are performed sequentially in a single tube. This approach is faster, reduces pipetting steps and the associated risk of contamination, and is ideal for processing large numbers of samples for a limited number of targets [4] [6].

- Two-Step RT-qPCR: The RT and qPCR reactions are performed in separate tubes with individually optimized reaction buffers. The key advantage is flexibility; the stable cDNA product generated in the first step can be stored and used to analyze multiple different targets over time [4] [6]. This is beneficial when studying the expression of many genes from a single, precious liquid biopsy sample.

Table 1: Comparison of One-Step and Two-Step RT-qPCR Methods

| Feature | One-Step RT-qPCR | Two-Step RT-qPCR |

|---|---|---|

| Workflow | RT and qPCR in a single tube | RT and qPCR in separate tubes |

| Throughput | Suitable for high-throughput | Less suitable for high-throughput |

| Flexibility | Low; cDNA cannot be stored/re-used | High; cDNA can be used for multiple assays |

| Risk of Contamination | Lower | Higher |

| Optimization | Compromise conditions for both steps | Individual optimization for each step |

| Ideal For | Screening a few targets in many samples | Analyzing many targets from a single sample |

Detection Chemistries and Their Mechanisms

The real-time quantification in qPCR relies on fluorescent chemistries that report the accumulation of amplified DNA. The choice of chemistry involves a trade-off between specificity, cost, and multiplexing capability.

DNA-Binding Dyes

The simplest and most cost-effective chemistry involves fluorescent dyes that bind non-specifically to double-stranded DNA (dsDNA). SYBR Green is the most common example; it emits minimal fluorescence when free in solution but exhibits a strong fluorescent signal upon binding to the minor groove of dsDNA [5] [6]. The fluorescence increases as the amount of PCR product increases with each cycle.

- Advantage: Inexpensive and easy to use; no need for a specific probe.

- Disadvantage: Lack of inherent specificity; the dye will bind to any dsDNA, including non-specific amplification products and primer-dimers, which can lead to false-positive signals [6]. This necessitates the use of a melt curve analysis post-amplification to verify the identity of the PCR product.

Sequence-Specific Probes

These chemistries provide a higher level of specificity by using an oligonucleotide probe that is complementary to the target sequence. The TaqMan Probe system is the gold standard.

- Mechanism: A TaqMan probe is labeled with a fluorescent reporter dye at one end and a quencher molecule at the other. When intact, the quencher suppresses the reporter's fluorescence via Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET). During the PCR extension phase, the DNA polymerase's 5' to 3' exonuclease activity cleaves the probe, separating the reporter from the quencher and resulting in a permanent increase in fluorescence that is proportional to the target amplification [8] [6].

- Advantage: High specificity, as fluorescence requires both correct primer binding and probe hybridization. Enables multiplexing—the detection of multiple targets in a single reaction by using probes labeled with different colored fluorophores [6].

Table 2: Key Detection Chemistries for qPCR

| Chemistry | Mechanism of Action | Specificity | Multiplexing Potential |

|---|---|---|---|

| SYBR Green | Binds non-specifically to dsDNA | Low | None |

| TaqMan Probe | Relies on probe hydrolysis by DNA polymerase | High | High (with different dyes) |

Achieving Sensitivity: Key Experimental Considerations

The renowned sensitivity of RT-qPCR is not automatic; it is achieved through meticulous optimization of several experimental parameters.

Primer and Probe Design

Proper design of primers and probes is paramount for specific and efficient amplification. Key principles include [4] [5]:

- Exon-Exon Spanning: Primers should be designed to span an exon-exon junction. This ensures that the cDNA amplicon is shorter than any potential genomic DNA contaminant, preventing false positives from gDNA [4].

- Amplicon Length: Optimal amplicon length is typically between 70-200 base pairs. Shorter amplicons amplify with higher efficiency, which is critical for detecting low-abundance targets [5].

- GC Content and Secondary Structure: Primers should have a GC content of 40-60% and be checked to avoid self-complementarity or stable secondary structures that can hinder annealing and reduce efficiency [5].

- PCR Efficiency: This is a measure of how perfectly the reaction proceeds, with 100% efficiency representing a perfect doubling every cycle. The efficiency of an assay should ideally be between 90-110% [7] [6]. Efficiency can be calculated from a standard curve generated using a dilution series, using the formula: Efficiency (%) = (10^(-1/slope) - 1) x 100 [7].

Controls and Normalization

Robust experimental design requires appropriate controls to ensure data integrity.

- No-RT Control: A control reaction that includes all components except the reverse transcriptase. This is essential for identifying false-positive signals caused by contaminating genomic DNA in the RNA sample [4].

- Normalization with Reference Genes: To account for variations in RNA input, quality, and cDNA synthesis efficiency, the expression of the target gene must be normalized to that of stable, constitutively expressed reference genes (e.g., GAPDH, ACTB). This allows for meaningful comparisons between different samples [7] [6].

Application in Liquid Biopsy for Cancer Research

Liquid biopsy—the analysis of tumor-derived components in bodily fluids like blood—has emerged as a transformative, non-invasive approach in oncology. RT-qPCR plays a vital role in detecting and quantifying RNA-based biomarkers in these samples.

Liquid biopsies encompass a range of analytes, including circulating tumor cells (CTCs), circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), and extracellular vesicles (EVs), which carry nucleic acids including RNA [1] [9]. RT-qPCR is exquisitely suited to analyze the RNA content from these sources. For example, it can be used to:

- Detect circulating microRNAs (miRNAs) that are dysregulated in cancer [1].

- Quantify the expression of drug target genes or resistance markers from circulating EVs or CTCs [9].

- Monitor minimal Residual Disease (MRD) by detecting transcripts specific to a particular cancer type after treatment [10].

The following diagram illustrates how RT-qPCR is integrated into a typical liquid biopsy research workflow for cancer biomarker analysis.

The technique's high sensitivity is crucial here, as it allows for the detection of extremely rare RNA molecules shed by tumors into the bloodstream against a high background of normal cellular RNA. Furthermore, the quantitative nature of RT-qPCR enables researchers to track dynamic changes in these biomarker levels over time, providing a real-time view of tumor response to therapy or the emergence of resistance [1] [9].

Advanced Multiplexing Strategies

The need to analyze multiple biomarkers simultaneously from a limited liquid biopsy sample has driven the development of advanced multiplexing strategies. While traditional multiplex qPCR is limited by the number of distinct fluorescent channels available on the instrument, novel approaches are pushing these boundaries.

One innovative method is Amplitude Modulation. This technique allows for the detection of multiple targets in a single fluorescent channel by assigning each target a unique concentration of its respective TaqMan probe. Because the final fluorescent intensity is proportional to the probe concentration, each combination of present targets generates a distinct endpoint fluorescence "signature." This method has been demonstrated to accurately detect up to nine different targets across three color channels, significantly expanding the multiplexing capacity of standard RT-qPCR instruments without requiring new hardware or chemistry [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for RT-qPCR in Liquid Biopsy Research

| Reagent / Material | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Reverse Transcriptase | Enzyme that synthesizes cDNA from an RNA template. | Choose enzymes with high thermal stability for GC-rich transcripts or those with secondary structure [4]. |

| DNA Polymerase | Enzyme that amplifies the cDNA target during qPCR. | Hot-start enzymes are preferred to reduce non-specific amplification [5]. |

| Fluorescent Probes (TaqMan) | Provide sequence-specific detection of the amplified target. | Essential for multiplexing; requires individual optimization of probe concentrations [8] [6]. |

| Fluorescent Dyes (SYBR Green) | Bind non-specifically to double-stranded DNA. | Cost-effective; requires post-amplification melt curve analysis to verify specificity [6]. |

| Sequence-Specific Primers | Define the region of the cDNA to be amplified. | Must be designed for high specificity and efficiency (90-110%); should span exon-exon junctions where possible [4] [5]. |

| dNTPs | Nucleotide building blocks for cDNA and new DNA strands. | |

| RNase Inhibitors | Protect RNA templates from degradation during the RT reaction. | Critical for working with low-input or degraded samples from liquid biopsies [5]. |

| Reference Gene Assays | Used to normalize target gene expression to a stably expressed gene. | Vital for accurate quantification; stability of reference genes must be validated for the sample type under investigation [6]. |

Liquid biopsy has emerged as a revolutionary, non-invasive approach for cancer detection and monitoring, presenting a compelling alternative to traditional tissue biopsies. By analyzing tumor-derived components circulating in various bodily fluids such as blood, this technique provides a dynamic window into tumor biology and heterogeneity [1] [11]. Among these components, RNA biomarkers—particularly messenger RNA (mRNA), microRNA (miRNA), and other forms of circulating RNA—have gained significant prominence due to their stability in extracellular environments and the rich biological information they encode [12] [13]. Their detection and quantification via Reverse Transcription Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-qPCR) offer a highly sensitive, specific, and accessible method for researchers and clinicians engaged in cancer diagnostics and therapeutic monitoring.

The application of RT-qPCR in profiling these RNA biomarkers facilitates early cancer detection, real-time monitoring of treatment efficacy, assessment of emerging drug resistance, and detection of minimal residual disease [14] [15] [12]. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of the core RNA biomarkers used in RT-qPCR-based liquid biopsy analyses, detailing their characteristics, methodological protocols, and practical applications within oncological research and drug development.

microRNA (miRNA) as Biomarkers

Biology and Significance

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are short, non-coding RNA molecules typically 18–25 nucleotides in length that play a fundamental role in the post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression [14] [13]. They function by binding to complementary sequences in the 3' or 5' untranslated regions (UTRs) of target messenger RNAs (mRNAs), leading to mRNA degradation or translational repression [14]. The discovery of the first miRNA, Lin-4, in Caenorhabditis elegans in 1993 by Victor Ambros and colleagues reshaped the scientific understanding of gene regulation [14]. This was followed by the identification of Let-7, which is evolutionarily conserved across species, including humans [14]. The significance of miRNAs in cancer biology was firmly established by a pioneering study revealing that miR-15a and miR-16-1 are often deleted or down-regulated in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL), leading to increased expression of the anti-apoptotic protein BCL-2 [14].

The exceptional stability of circulating miRNAs in biofluids, despite the presence of endogenous RNases, makes them particularly attractive as biomarkers [14] [12]. This stability is conferred through their association with various carriers that protect them from degradation. These carriers include extracellular vesicles (EVs) such as exosomes and microvesicles; protein complexes with Argonaute 2 (AGO2) or nucleophosmin 1 (NPM1); and lipoproteins such as high-density lipoprotein (HDL) [12] [13]. This robust stability, coupled with their disease-specific expression patterns, underpins their utility as sensitive and reliable biomarkers in liquid biopsy [12].

Experimental Protocol for miRNA Analysis

Workflow: RT-qPCR Analysis of Circulating miRNA

The analysis of circulating miRNAs via RT-qPCR requires meticulous sample handling and specialized reagents to accurately quantify these small RNA molecules. The protocol begins with sample collection and stabilization. Blood samples should be collected in EDTA or citrate tubes (heparin is avoided as it can inhibit PCR) and processed within 2 hours of collection to minimize cellular RNA contamination and miRNA degradation [12]. Plasma or serum is obtained via centrifugation, typically at 1,500-2,000 × g for 10 minutes to remove cells, followed by a higher-speed centrifugation (e.g., 12,000-16,000 × g for 15 minutes) to eliminate residual platelets and cell debris [12]. The resulting supernatant (plasma/serum) should be aliquoted and stored at -80°C. The inclusion of RNase inhibitors at this stage is recommended to preserve RNA integrity.

RNA extraction is most commonly performed using phenol-chloroform-based methods (e.g., TRIzol LS) followed by purification with silica-based columns specifically designed for small RNA isolation. These columns typically have pore sizes that retain small RNAs below 200 nucleotides. Commercially available kits such as the miRNeasy Serum/Plasma Kit (Qiagen) or the miRCURY RNA Isolation Kit (Bio-Rad) are optimized for this purpose. To account for extraction efficiency variations, the introduction of a non-human synthetic spike-in control (e.g., C. elegans miR-39) is essential and should be added to the lysis buffer at the beginning of the extraction process [12].

For the reverse transcription step, stem-loop RT primers are the gold standard for miRNA analysis. These primers have a short region that binds to the 3' end of the mature miRNA and a universal stem-loop structure. This design creates a longer, extended cDNA product that provides a more specific template for the subsequent qPCR, overcoming the challenge posed by the short length of mature miRNAs. The reaction utilizes reverse transcriptase enzymes with high processivity and the ability to reverse transcribe structured RNA.

The qPCR amplification can be performed using specific TaqMan miRNA assays, which employ a miRNA-specific forward primer, a universal reverse primer, and a TaqMan probe with a fluorophore and quencher. Alternatively, SYBR Green-based systems with specifically designed primers can be used, though they may require meticulous optimization to ensure specificity. The quantification cycle (Cq) values are obtained, and relative quantification is performed using the comparative ΔΔCt method. Normalization is critical and can be achieved using the spiked-in synthetic controls (e.g., cel-miR-39) or a combination of endogenous stable miRNAs identified in the specific sample matrix (e.g., miR-16-5p, miR-484) [12]. The selection of appropriate reference genes must be empirically validated for the specific sample set and cancer type under investigation.

Table 1: Key miRNA Biomarkers in Cancer Detection and Monitoring

| miRNA | Cancer Type | Expression Change | Potential Clinical Utility | Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-21 | Breast Cancer, Lung Cancer, Melanoma | Upregulated | Diagnosis, Prognosis, Therapeutic Resistance | Prevalent in multiple cancer types; acts as an "oncomiR" [12] |

| miR-145 | Breast Cancer, Lung Cancer | Downregulated | Tumor Suppressor, Early Detection | Frequently downregulated in carcinomas [12] |

| miR-205-5p | Pancreatic Cancer | Upregulated | Early Detection (vs. chronic pancreatitis) | 91.5% accuracy distinguishing cancer from pancreatitis [14] |

| miR-1247-5p, miR-301b-3p, miR-105-5p | Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) | Upregulated | Diagnostic Panel | AUCs of 0.769, 0.761, and 0.777, respectively [14] |

| miR-29c | Melanoma | Downregulated | Diagnostic (vs. other cancers) | Distinguishes melanoma from metastatic colon/renal cancer [13] |

| MEL38 Signature | Melanoma | Specific Signature | Diagnostic and Prognostic Panel | 93% sensitivity, 98% specificity for invasive melanoma [13] |

Messenger RNA (mRNA) as Biomarkers

Biology and Significance

Messenger RNA (mRNA) serves as the intermediary template for protein synthesis, carrying genetic information from DNA in the nucleus to the ribosomes in the cytoplasm. In the context of liquid biopsy, the presence of circulating mRNA fragments, often encapsulated within extracellular vesicles or bound to protective proteins, provides a snapshot of the active gene expression profile of tumor cells [11]. The analysis of tumor-specific mRNAs in circulation, such as those related to hormone receptors, growth factors, or epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) markers, can offer invaluable insights into tumor subtype, aggressiveness, and potential therapeutic vulnerabilities [15].

A key application in breast cancer research, for instance, involves detecting mRNAs for the estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) from circulating tumor cells (CTCs) or exosomes [15]. This can help monitor dynamic changes in receptor status, a phenomenon known as receptor conversion, which may underlie acquired resistance to targeted therapies [15]. Similarly, the detection of PD-L1 mRNA in EVs or CTCs presents a non-invasive strategy to identify patients who might respond to immunotherapy [15]. However, a significant technical challenge is the inherent instability of cell-free mRNA in plasma due to its susceptibility to ribonucleases, making robust pre-analytical protocols paramount [15].

Experimental Protocol for mRNA Analysis

Workflow: RT-qPCR Analysis of Circulating mRNA

The protocol for mRNA analysis from liquid biopsy samples often requires an initial enrichment step for the mRNA source, such as Circulating Tumor Cells (CTCs) or extracellular vesicles (EVs). CTCs can be isolated from whole blood using platforms like the FDA-cleared CellSearch system (based on EpCAM immunomagnetic enrichment) or microfluidic devices [1]. EVs, including exosomes, can be harvested from plasma or serum via differential ultracentrifugation, density gradient centrifugation, or commercial polymer-based precipitation kits [11].

Following isolation, the RNA extraction process is critical. Due to the fragmented nature of circulating mRNA, total RNA is typically extracted. However, for CTC-derived mRNA, a higher-quality RNA may be obtained. The use of oligo(dT) magnetic beads is highly recommended as they selectively enrich for polyadenylated mRNA, thereby reducing background from non-polyadenylated RNA (like miRNA and ribosomal RNA) and improving the detection sensitivity for protein-coding transcripts.

A DNase treatment step is imperative to remove any contaminating genomic DNA that could lead to false-positive amplification signals. This is typically performed on the column or in solution after RNA extraction.

The reverse transcription reaction should utilize a mix of oligo(dT) primers and random hexamers. Oligo(dT) primers bind to the poly-A tail of eukaryotic mRNAs, ensuring the reverse transcription of full-length or near-full-length transcripts, while random hexamers can prime from any point on the RNA molecule, which is useful for degraded RNA or transcripts that may lack a complete poly-A tail.

For qPCR amplification, TaqMan probe-based chemistry is generally preferred over SYBR Green for its superior specificity, especially when dealing with complex backgrounds and closely related gene family members. The assays must be designed to span exon-exon junctions to prevent amplification from any residual genomic DNA. The amplicon size should be kept relatively short (80-150 bp) to accommodate the typically fragmented nature of circulating RNA.

Data analysis requires careful normalization. When analyzing RNA from isolated CTCs or EVs, classic endogenous housekeeping genes (e.g., GAPDH, ACTB, HPRT1) can be used, but their stability must be rigorously validated in the specific sample context. For cell-free mRNA in plasma, the use of spiked-in synthetic external RNA controls or globally identified stable mRNA references is necessary for reliable relative quantification using the ΔΔCt method.

Table 2: Key mRNA Biomarkers and Their Applications in Liquid Biopsy

| mRNA Target | Cancer Type | Source in Liquid Biopsy | Clinical/Research Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| ER/PR/HER2 | Breast Cancer | CTCs, Exosomes | Monitoring receptor status and therapy resistance [15] |

| PD-L1 | Triple-Negative Breast Cancer (TNBC), Melanoma | CTCs, Exosomes, Plasma | Predicting response to immunotherapy [15] |

| EMT Markers (e.g., Vimentin, N-cadherin) | Various Carcinomas | CTCs | Assessing metastatic potential and aggressiveness [1] |

| TMPRSS2-ERG | Prostate Cancer | CTCs | Subtyping and prognostic stratification |

| B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2) | Chronic Lymphocytic Leukaemia (CLL) | Blood | Linked to apoptotic resistance [14] |

Other Circulating RNA Biomarkers

Beyond miRNA and mRNA, the circulatory landscape contains other RNA species with biomarker potential. Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) and circular RNAs (circRNAs) are gaining attention for their roles in cancer biology and their notable stability in biofluids, often attributed to their circular structure or association with EVs [11]. Furthermore, the total pool of circulating cell-free RNA (cfRNA) can be interrogated for global transcriptomic changes, mutation detection, or fusion transcripts, providing a comprehensive view of the tumor's genetic activity [11]. The protocols for analyzing these molecules often overlap with those for mRNA but may require specific enzymatic treatments or library preparation strategies to capture their unique features (e.g., backsplicing junctions for circRNAs).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful RT-qPCR analysis of RNA biomarkers in liquid biopsy relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The following table details key solutions and their critical functions in the experimental workflow.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for RT-qPCR in Liquid Biopsy

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Importance |

|---|---|---|

| Blood Collection & Stabilization | EDTA or Citrate Tubes; Cell-Free DNA/RNA Blood Collection Tubes (e.g., Streck, PAXgene) | Prevents coagulation and preserves RNA integrity by stabilizing nucleated blood cells, preventing gene expression changes post-phlebotomy. |

| RNA Extraction | miRNeasy Serum/Plasma Kit (Qiagen); miRCURY RNA Isolation Kit (Bio-Rad); TRIzol LS Reagent | Efficiently isolates high-quality total RNA, including the small RNA fraction (<200 nucleotides), from complex biofluids like plasma and serum. |

| Spike-In Controls | Synthetic C. elegans miRNAs (e.g., cel-miR-39, cel-miR-54, cel-miR-238); External RNA Controls Consortium (ERCC) RNA Spike-Ins | Monitors and corrects for variations in RNA extraction efficiency and reverse transcription efficacy, enabling reliable relative quantification. |

| Reverse Transcription | Stem-Loop RT Primers (for miRNA); Oligo(dT) Primers (for mRNA); Random Hexamers; High-Efficiency Reverse Transcriptase (e.g., MultiScribe) | Generates complementary DNA (cDNA) from RNA templates. Stem-loop primers provide superior specificity and efficiency for short miRNA targets. |

| qPCR Amplification | TaqMan MicroRNA Assays; TaqMan Gene Expression Assays; SYBR Green Master Mix | Enables specific and sensitive quantification of target sequences. TaqMan probes offer higher specificity, crucial for discriminating between homologous sequences. |

| Reference Genes | Endogenous miRNAs (e.g., miR-16-5p, miR-484); Housekeeping mRNAs (e.g., GAPDH, ACTB); Spiked Synthetic RNAs | Used for data normalization to correct for technical variations, ensuring accurate interpretation of target RNA expression levels. |

The integration of mRNA, miRNA, and circulating RNA biomarkers with RT-qPCR technology represents a powerful paradigm in liquid biopsy research. This combination offers a minimally invasive means to obtain critical diagnostic, prognostic, and predictive information, enabling a shift towards personalized cancer management. While challenges remain in standardizing pre-analytical variables, normalizing data, and validating biomarkers across diverse populations, the trajectory of research is clear. As isolation techniques become more refined, detection technologies more sensitive, and bioinformatic analyses more sophisticated, the routine clinical application of RT-qPCR-based RNA biomarker detection is poised to revolutionize cancer care, from early detection to the monitoring of advanced disease. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering these protocols and understanding the biological context of these biomarkers is essential for driving this transformative field forward.

Quantitative Reverse Transcription PCR (RT-qPCR) stands as a cornerstone technology in molecular diagnostics, offering an unparalleled combination of analytical sensitivity, robust standardization, and cost-efficiency. This technical guide delineates the core advantages of RT-qPCR, with a specific focus on its application in liquid biopsy for cancer detection research. We detail experimental protocols that underpin its performance, provide structured quantitative data comparisons, and visualize key workflows. For the research scientist, this whitepaper serves as a foundational resource, affirming the critical role of RT-qPCR in advancing precision oncology through reliable, scalable, and accessible biomarker analysis.

Liquid biopsy, the analysis of tumor-derived markers in biofluids like blood, has emerged as a transformative approach for cancer diagnosis, prognosis, and therapy monitoring. Within this field, RNA biomarkers—including microRNAs (miRNAs), messenger RNAs (mRNAs), and other non-coding RNAs—offer profound insights into the tumor's molecular state [16] [17]. The detection of these biomarkers, however, is technically challenging due to their low abundance and the complex background of clinical samples. RT-qPCR has established itself as a preeminent method for this task. Its unique value proposition lies in its ability to deliver a gold-standard level of performance for the sensitive, specific, and quantitative detection of RNA targets, making it indispensable for both foundational research and clinical assay development in oncology [18]. This document elucidates the technical foundations of RT-qPCR's key advantages, framing them within the critical needs of liquid biopsy research.

Core Technical Advantages

The utility of RT-qPCR in liquid biopsy applications is anchored on three principal advantages: exceptional sensitivity, a high degree of standardization, and significant cost-effectiveness.

Superior Sensitivity and Specificity

The ability of RT-qPCR to detect minute quantities of nucleic acid is paramount for liquid biopsies, where targets like cell-free RNA can be present at extremely low concentrations.

- Wide Dynamic Range and Low Limit of Detection (LOD): Advanced one-pot RT-qPCR methods have demonstrated a wide linear dynamic range from 7.5 × 10¹ to 7.5 × 10⁸ copies/reaction, enabling the accurate quantification of target RNA across a vast concentration span, which is essential for monitoring disease progression [16]. The LOD can reach femtomolar concentrations, allowing for the detection of rare RNA transcripts [16].

- Specificity for Sequence Variants: The combination of sequence-specific priming and fluorescent probe systems (e.g., TaqMan hydrolysis probes) allows RT-qPCR to distinguish between closely related miRNA family members or single-nucleotide polymorphisms, which is critical for identifying specific cancer-associated mutations or isoforms [16] [19].

- Performance in Complex Matrices: RT-qPCR reagents have been engineered for robust performance in inhibitory clinical matrices such as plasma, serum, and samples derived from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue. Next-generation polymerases and optimized buffers mitigate the effects of PCR inhibitors commonly found in these samples, ensuring reliable results [18].

Table 1: Sensitivity and Dynamic Range of RT-qPCR in Biomarker Detection

| Target Type | Reported Linear Dynamic Range (copies/reaction) | Key Application in Liquid Biopsy | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| miRNA | 7.5 x 10¹ to 7.5 x 10⁸ | Multiplex detection of cancer biomarkers in serum | [16] |

| mRNA (e.g., PIK3CA) | Comparable performance in diluted blood lysates | SNP analysis and deletion detection from whole blood | [20] |

| SARS-CoV-2 RNA | Detection in direct (no extraction) protocols | Model for rapid, sensitive viral RNA detection | [21] |

Robust Standardization and Reproducibility

The quantitative nature of RT-qPCR demands rigorous standardization to minimize measurement uncertainty and ensure data reproducibility across experiments and laboratories.

- Standardized Data Analysis: Statistical methods have been developed to objectively handle outliers and compare calibration curves, moving beyond subjective visual assessments. The implementation of guidelines for accepting or rejecting statistical outliers, such as those based on ISO 17025, is critical for generating reliable and comparable quantitative data [22].

- Reference Gene Validation: Accurate normalization is the cornerstone of reliable gene expression data. Studies emphasize that the expression of commonly used "housekeeping" genes (e.g., ACTB, GAPDH, RPL13A) can vary significantly under different experimental conditions, such as in dormant cancer cells. It is therefore mandatory to validate reference genes for each specific biological context to prevent significant distortion of gene expression profiles [23].

- Multiplexing Capability: RT-qPCR's strong multiplexing capability allows for the simultaneous detection of multiple clinically relevant RNA targets in a single reaction. This not only conserves precious sample but also ensures that all targets are amplified under identical conditions, improving the internal consistency and reliability of the data. For example, multiplex panels can simultaneously assess alterations in several genes (e.g., EGFR, KRAS, BRAF) from limited liquid biopsy material [18] [24].

Unmatched Cost-Effectiveness and Workflow Efficiency

In an environment of constrained research budgets and the need for scalable testing, the economic and practical advantages of RT-qPCR are significant.

- Low per-Reaction Cost: The cost of RT-qPCR testing is substantially lower than next-generation sequencing (NGS), typically ranging from $50 to $200 per test compared to $300 to $3,000 for NGS. This affordability makes RT-qPCR ideal for large-scale screening initiatives and routine diagnostics [18].

- Rapid Turnaround Time: Unlike sequencing platforms that can take days to generate data, RT-qPCR delivers clinically actionable results within a few hours. This rapid turnaround is crucial for time-sensitive scenarios in research and potential clinical decision-making [18] [21].

- Protocol Simplification and Resource Savings: Recent methodological advances enable further cost and time savings. For instance, the GG-RT PCR method allows for real-time PCR amplification directly from diluted and heat-treated whole blood lysates, eliminating the need for DNA/RNA extraction kits and reducing both cost and processing time [20]. Similarly, direct RT-PCR assays for SARS-CoV-2 that omit the RNA extraction step have maintained high sensitivity (93.9%) while reducing turnaround time and reagent costs [21].

Table 2: Cost and Workflow Comparison of RNA Detection Technologies

| Parameter | RT-qPCR | Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) | Microarray |

|---|---|---|---|

| Approximate Cost per Test | $50 - $200 | $300 - $3,000 | $100 - $500 |

| Typical Turnaround Time | 2 - 4 hours | 1 - 5 days | 1 - 2 days |

| Sample Throughput | High (96/384-well formats) | High (multiplexed) | Medium to High |

| Ease of Data Analysis | Relatively Simple | Complex, requires bioinformatics | Moderate |

| Best Suited For | Targeted, quantitative analysis of known biomarkers | Discovery, comprehensive transcriptome profiling | Profiling of known, pre-defined transcripts |

Experimental Protocols for Liquid Biopsy Research

The following section outlines detailed protocols that leverage the advantages of RT-qPCR for cancer biomarker detection.

Protocol 1: One-Pot, One-Step Multiplex miRNA RT-qPCR

This novel protocol, mediated by a reverse transcription-hairpin occlusion system (RT-HOS), enables highly specific, one-pot detection of multiple miRNAs, ideal for profiling serum or plasma samples [16].

- Sample Preparation and Lysis: Extract total RNA, including small RNAs, from serum or plasma using a phenol-guanidine-based lysis reagent. Include a spike-in synthetic RNA for normalization to control for extraction efficiency.

- Primer and Reaction Setup: Design and synthesize RT-HOS primers. Each primer functions as a reverse transcription primer, a fluorescent probe (labeled with a 5' fluorophore), and a reverse PCR primer. Combine with a complementary hairpin quencher oligonucleotide.

- Prepare a master mix containing: High-Fidelity or Taq DNA polymerase, dNTPs, reaction buffer, and the RT-HOS primer/hairpin quencher complexes.

- Aliquot the master mix into a qPCR plate and add the RNA template.

- Reverse Transcription and Amplification: Run the one-step reaction on a real-time PCR instrument with the following cycling conditions:

- Reverse Transcription: 50°C for 15-30 minutes (higher temperature enhances specificity).

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 2 minutes.

- Amplification (40-50 cycles): Denature at 95°C for 15 seconds, then anneal/extend at 60-65°C for 30-60 seconds (with fluorescence acquisition).

- Data Analysis: Determine Cycle Threshold (Ct) values using the instrument's software. Use a standard curve of synthetic miRNA for absolute quantification or the ΔΔCt method for relative quantification to a validated reference gene.

Protocol 2: Direct RT-qPCR from Whole Blood (GG-RT PCR)

This cost-effective protocol bypasses the nucleic acid extraction step, saving time and resources while being suitable for applications like SNP analysis from blood [20].

- Blood Lysate Preparation:

- Mix 400 µL of EDTA-treated whole blood with 1.6 mL of distilled water (to achieve an ~80% dilution, facilitating cell lysis via osmotic pressure).

- Incubate the mixture at 95°C for 20 minutes, vortexing 2-3 times during incubation.

- Centrifuge at 14,000 rpm for 5 minutes to pellet debris.

- Collect the clear supernatant (lysate) and use it directly as a template, or prepare 1:5 and 1:10 dilutions in water.

- qPCR Reaction Setup:

- Use a SYBR Green I Master Mix.

- In each reaction, combine 2.5 µL of blood lysate (or dilution) with 5 pmol of each sequence-specific primer.

- Ensure amplicons are designed to be small (80-150 bp) for efficient amplification from the complex lysate.

- qPCR Amplification:

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 10 minutes.

- Amplification (40 cycles): 95°C for 15 seconds, 60-61°C for 30 seconds (with fluorescence acquisition).

- Post-Amplification Analysis:

- Perform melt curve analysis by incrementally heating the products from 65°C to 95°C while monitoring fluorescence. A single sharp peak confirms specific amplification.

- Compare Ct values to a standard curve generated from samples with known DNA concentrations to determine PCR efficiency.

Visualizing Workflows and Reagent Systems

RT-qPCR Workflow for Liquid Biopsy

The following diagram illustrates the streamlined workflow of RT-qPCR for liquid biopsy analysis, from sample collection to data interpretation.

RT-HOS Primer System for miRNA Detection

This diagram details the mechanism of the RT-HOS primer system, a key innovation for specific, one-pot miRNA detection.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for RT-qPCR in Oncology Research

| Reagent / Material | Critical Function | Technical Notes for Liquid Biopsy |

|---|---|---|

| High-Sensitivity Master Mix | Provides DNA polymerase, dNTPs, buffers, and fluorescence dye/probe system. | Select mixes engineered for inhibitor resistance (e.g., tolerant to heparin, heme) and compatible with multiplexing [18]. |

| RT-HOS Primers & Quenchers | Enable one-pot, one-step multiplex miRNA detection. | HPLC-purified primers are essential for specificity. The system allows reverse transcription at higher temperatures, improving accuracy for short RNA targets [16]. |

| Validated Reference Genes | Serve as endogenous controls for data normalization. | Crucially validate stability in your specific sample type (e.g., plasma, serum) and cancer model. Do not assume standard genes (e.g., ACTB) are stable [23]. |

| RNA Stabilization Reagents | Preserve RNA integrity in blood samples pre-processing. | Prevents degradation of labile RNA biomarkers, ensuring an accurate representation of the in vivo profile. |

| Synthetic RNA Standards | Generate standard curves for absolute quantification. | Allows precise determination of miRNA/mRNA copy numbers per volume of biofluid, critical for longitudinal monitoring [16]. |

RT-qPCR remains an indispensable technology in the arsenal of cancer researchers, particularly in the rapidly advancing field of liquid biopsy. Its trifecta of advantages—exceptional sensitivity capable of detecting low-abundance RNA biomarkers, a highly standardized framework that ensures reproducible and reliable data, and superior cost-effectiveness that enables scalable application—solidifies its status as a gold standard. As innovations in reagent engineering, assay design, and protocol simplification continue to emerge, the utility of RT-qPCR will only expand, further accelerating its role in the discovery, validation, and ultimately, the clinical translation of novel RNA biomarkers for precision oncology.

Liquid biopsy represents a transformative, minimally invasive approach for cancer management, enabling the detection of tumor-derived biomarkers from biofluids such as blood, urine, and cerebrospinal fluid [1]. Unlike traditional tissue biopsies, which provide a snapshot from a single anatomical site, liquid biopsies capture the molecular heterogeneity of tumors and allow for real-time monitoring of disease progression and treatment response [25] [26]. Reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) has emerged as a cornerstone technology for analyzing RNA biomarkers from liquid biopsies due to its exceptional sensitivity, specificity, quantitative capabilities, and cost-effectiveness [5] [18]. This technical guide provides a comprehensive workflow for implementing RT-qPCR in liquid biopsy cancer detection research, framed within the context of advancing precision oncology.

The application of RT-qPCR in liquid biopsy spans multiple critical areas in cancer research, including the detection of circulating tumor cells (CTCs), analysis of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), and profiling of various RNA species such as messenger RNA (mRNA), microRNA (miRNA), and circular RNA (circRNA) [1]. Among these, circRNAs have gained significant attention as promising biomarkers due to their remarkable stability in bodily fluids, a characteristic conferred by their covalently closed-loop structure that confers resistance to exonuclease degradation [25]. This structural stability makes circRNAs exceptionally suitable for the liquid biopsy context, where biomarkers are often present at low concentrations and must withstand variable conditions before analysis.

Liquid Biopsy Sample Collection and Processing

Sample Source Selection

The initial critical step in the liquid biopsy workflow involves selecting the appropriate biofluid source, which significantly impacts biomarker yield and analytical sensitivity. Blood remains the most commonly used source, with plasma being preferred over serum for ctDNA and RNA analyses due to less contamination from genomic DNA released during the clotting process [27] [26]. For cancers located in specific anatomical sites, local biofluids often offer superior biomarker concentration and reduced background noise. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) demonstrates enhanced sensitivity for central nervous system tumors, while urine is particularly effective for urological cancers such as bladder cancer, where studies have reported mutation detection sensitivity of 87% in urine versus only 7% in plasma [26]. Saliva and sputum serve as valuable sources for head and neck cancers and lung adenocarcinoma, with studies showing high concordance (93%) in ctDNA detection between saliva and blood samples [27].

Sample Collection and Pre-analytical Processing

Proper sample collection and processing are paramount for preserving nucleic acid integrity and ensuring reliable RT-qPCR results. Blood samples should be collected in specialized tubes containing stabilizers to prevent nucleic acid degradation and processed within a narrow time window to maintain biomarker stability [1]. Plasma separation through centrifugation must be performed carefully to avoid contamination with cellular components. For RNA biomarkers like circRNAs, the exceptional stability conferred by their closed-loop structure provides some protection against degradation, but proper handling remains essential [25]. The following table summarizes key considerations for sample collection from different biofluids:

Table 1: Liquid Biopsy Sample Collection Guidelines for RT-qPCR Analysis

| Biofluid Source | Recommended Collection Tubes | Processing Timeline | Centrifugation Conditions | Primary RNA Biomarkers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood Plasma | EDTA or specialized cfDNA/RNA tubes | Within 2-4 hours of draw | Dual-centrifugation: 1,600-2,000 × g followed by 10,000-16,000 × g | circRNA, miRNA, mRNA |

| Cerebrospinal Fluid | Sterile collection tubes | Immediate processing preferred | 2,000-3,000 × g for 10 minutes | circRNA, miRNA |

| Urine | Sterile containers with RNA stabilizers | Within 4 hours | 2,000-3,000 × g for 10 minutes | circRNA, mRNA |

| Saliva/Sputum | Containers with RNA stabilizers | Within 2 hours | 2,000-3,000 × g for 10 minutes | circRNA, mRNA |

After processing, samples are typically aliquoted to avoid freeze-thaw cycles and stored at -80°C until nucleic acid extraction. Maintaining a consistent cold chain throughout transportation and storage is critical for preserving RNA integrity, particularly for less stable linear RNA species.

Nucleic Acid Isolation and Quality Control

Extraction Methods for Liquid Biopsy Samples

Nucleic acid extraction from liquid biopsy samples requires specialized protocols optimized for low-abundance targets and challenging sample matrices. For RNA isolation, methods incorporating guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction combined with silica membrane-based purification consistently yield high-quality RNA suitable for sensitive RT-qPCR applications [5]. The closed-loop structure of circRNAs provides natural resistance to degradation during extraction, but proper handling remains essential to preserve other RNA species. For comprehensive biomarker analysis, parallel extraction of DNA and RNA from the same sample aliquot enables correlative studies of DNA mutations and RNA expression patterns from a single liquid biopsy specimen.

The extraction process must address several challenges unique to liquid biopsies, including low nucleic acid concentrations, the presence of PCR inhibitors (hemoglobin in blood, mucins in saliva), and the need for high recovery efficiency. Incorporating carrier RNA during extraction can improve yields when working with low-input samples, but may interfere with accurate quantification. For circRNA analysis, protocols often include RNase R treatment to digest linear RNAs and enrich for circular forms, thereby enhancing detection sensitivity for these biomarkers [25].

Quality Assessment and Quantification

Rigorous quality assessment of extracted nucleic acids is essential before proceeding to RT-qPCR analysis. For RNA samples, integrity is typically evaluated using microfluidic capillary electrophoresis systems, which generate RNA Integrity Numbers (RIN) that correlate with amplification efficiency. While circRNAs remain stable despite partial RNA degradation, high-quality total RNA (RIN >7) is recommended for accurate gene expression analysis. Spectrophotometric methods provide concentration measurements but cannot distinguish between intact and degraded RNA or differentiate circRNAs from their linear counterparts.

For liquid biopsy samples with limited material, droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) offers an alternative quantification approach that provides absolute copy number measurements without requiring standard curves. This method is particularly valuable for establishing input amounts for rare biomarker detection. The following table outlines quality control parameters and thresholds for liquid biopsy nucleic acids:

Table 2: Quality Control Standards for Liquid Biopsy Nucleic Acids

| Parameter | Assessment Method | Acceptance Criteria for RT-qPCR | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA Concentration | Fluorometric quantification | ≥0.5 ng/μL | Spectrophotometry may overestimate due to contaminants |

| RNA Purity | Spectrophotometry (A260/A280) | 1.8-2.1 | Deviations suggest protein or chemical contamination |

| RNA Integrity | Microfluidic electrophoresis (RIN) | ≥7.0 | circRNAs may be detectable in partially degraded samples |

| circRNA Enrichment | RT-qPCR with divergent primers | ΔCt >5 vs non-enriched | Confirm enrichment after RNase R treatment |

| Genomic DNA Contamination | No-RT control | Ct >35 or undetectable | Indicates need for DNase treatment |

RT-qPCR Experimental Workflow

Reverse Transcription: Converting RNA to cDNA

The reverse transcription (RT) reaction represents a critical first step in RT-qPCR, converting RNA templates into more stable complementary DNA (cDNA) suitable for PCR amplification. This process requires several key reagents: primers to initiate synthesis, reverse transcriptase enzyme, dNTPs as building blocks, MgCl₂ as a cofactor, and RNase inhibitors to protect template RNA [5]. Three primer strategies are commonly employed, each with distinct advantages for liquid biopsy applications. Oligo(dT) primers target the poly(A) tails of mRNAs, generating full-length transcripts but excluding non-polyadenylated RNAs such as some circRNAs. Random primers provide comprehensive coverage of all RNA species by annealing at multiple points along RNA transcripts, making them particularly suitable for detecting diverse RNA biomarkers. Gene-specific primers offer the highest sensitivity for predetermined targets and are ideal when focusing on specific circRNAs or mutations [4].

The RT reaction follows a defined four-step process: (1) denaturation of RNA secondary structures at 65-70°C for 5-10 minutes; (2) primer annealing at optimal temperature; (3) cDNA synthesis at 37-50°C for 30-60 minutes; and (4) reaction termination by enzyme inactivation at 70-85°C [5]. For circRNA analysis, additional considerations include the potential need for specialized reverse transcriptases that can handle highly structured RNA elements and the possible incorporation of RNase R treatment to enrich circular transcripts before reverse transcription.

Quantitative PCR: Amplification and Detection

The qPCR phase amplifies and quantifies specific cDNA targets using sequence-specific primers, DNA polymerase, dNTPs, and fluorescent detection systems [5]. Two primary detection chemistries are employed: intercalating dyes like SYBR Green that bind nonspecifically to double-stranded DNA, and fluorescent probes such as TaqMan probes that provide target-specific detection through fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) mechanisms [5] [4]. Probe-based systems offer superior specificity for liquid biopsy applications where distinguishing closely related sequences or detecting single-nucleotide variants is essential.

Primer design represents perhaps the most critical factor in successful qPCR assay development. For mRNA targets, primers should ideally span exon-exon junctions to prevent amplification of contaminating genomic DNA [4]. For circRNA detection, "divergent" primers that target the unique back-splice junction are essential to specifically amplify circular transcripts while excluding linear isoforms [25]. Optimal primers are typically 18-25 nucleotides in length with GC content of 40-60%, and should be validated for specificity and efficiency using dilution series [5]. The thermal cycling profile consists of initial denaturation (95°C), followed by 30-40 cycles of denaturation (95°C), primer annealing (55-65°C), and extension (72°C), with fluorescence measurement occurring during each cycle [5].

One-Step vs. Two-Step RT-qPCR Protocols

Researchers must choose between one-step and two-step RT-qPCR protocols based on their specific application requirements. In one-step protocols, reverse transcription and qPCR occur in the same tube with a unified buffer system, minimizing pipetting steps and reducing contamination risk [4]. This approach is ideal for high-throughput applications and when analyzing multiple samples for a limited number of targets. Two-step protocols separate the reverse transcription and qPCR reactions, allowing for optimized conditions in each step and enabling the generated cDNA to be used for multiple qPCR assays [4]. This flexibility makes two-step approaches preferable for longitudinal studies or when analyzing each sample for numerous targets.

For liquid biopsy applications, one-step protocols offer advantages in minimizing sample loss during transfer steps, while two-step protocols provide more flexibility for assay optimization and multiple analyses from precious samples. The decision between these approaches should consider sample quantity, number of targets, throughput requirements, and need for assay optimization.

Table 3: Comparison of One-Step vs. Two-Step RT-qPCR Approaches

| Parameter | One-Step RT-qPCR | Two-Step RT-qPCR |

|---|---|---|

| Workflow Efficiency | Combined reaction in single tube | Separate reactions in different tubes |

| Hands-on Time | Minimal pipetting steps | Additional transfer steps required |

| Sample Consumption | Lower - single reaction uses less sample | Higher - multiple reactions from same cDNA |

| Optimization Flexibility | Limited - compromised conditions for both reactions | High - independent optimization of RT and qPCR |

| Contamination Risk | Reduced - closed tube system | Increased - multiple open tube steps |

| cDNA Archive | Not possible - immediate amplification | Stable cDNA bank for future analyses |

| Ideal Application | High-throughput targeted screening | Multiple targets from limited samples |

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Quantification Methods and Normalization

RT-qPCR data analysis centers on the cycle threshold (Ct) value, which represents the amplification cycle at which the fluorescence signal exceeds a defined threshold [5]. Low Ct values indicate high target abundance, while high Ct values reflect low abundance. Two primary quantification approaches are employed: absolute quantification, which determines exact copy numbers using a standard curve of known concentrations, and relative quantification, which compares expression levels between samples using reference genes for normalization [5]. For most liquid biopsy applications, relative quantification is preferred due to challenges in creating accurate standards for rare biomarkers.

Proper normalization is essential for meaningful RT-qPCR results, particularly in liquid biopsy where sample input may vary. Reference genes (often called housekeeping genes) should be carefully selected based on stable expression across sample types and experimental conditions. For circRNA analysis, normalization approaches may include using stable linear RNAs as references or spike-in synthetic circRNAs to control for extraction efficiency. The ΔΔCt method is widely used for relative quantification, calculating expression fold changes based on differences in Ct values between target and reference genes [5].

Quality Control and Validation

Robust quality control measures are essential for generating reliable liquid biopsy data. Each RT-qPCR experiment should include multiple controls: no-template controls to detect contamination, no-reverse transcription controls to assess genomic DNA contamination, and positive controls to verify reaction efficiency [4]. Amplification efficiency should be calculated from standard curves and fall within 90-110% for optimal results, with correlation coefficients (R²) >0.98 indicating a strong linear relationship [5].

For circRNA detection, additional validation is crucial to confirm circular nature rather than linear isoforms. This may include RNase R treatment resistance assays, Sanger sequencing of back-splice junctions, or comparison with linear transcript detection using convergent primers. In cancer biomarker applications, establishing clinical thresholds is particularly important, often requiring receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis to determine Ct values that optimally distinguish patient groups [25].

Applications in Cancer Research and Biomarker Development

circRNA Biomarkers in Drug Resistance Monitoring

Circular RNAs have emerged as particularly promising biomarkers for monitoring therapy response and detecting emergent drug resistance in cancer. Their stability, abundance in body fluids, and functional involvement in gene regulation make them ideal candidates for liquid biopsy approaches [25]. Several circRNAs have been implicated in mediating resistance to targeted therapies through diverse mechanisms including microRNA sponging, regulation of autophagy, inhibition of apoptosis, and modulation of drug efflux pumps [25].

In non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), circRNA_102231 overexpression is associated with resistance to gefitinib, an EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitor, through sponging of miR-130a-3p [25]. Similarly, in breast cancer, CDR1as correlates with tamoxifen resistance via modulation of the miR-7/EGFR pathway [25]. The following table highlights key circRNAs implicated in therapy resistance: