Revolutionizing Cancer Target Discovery: A Practical Guide to AlphaFold2 and AlphaFold3 for Structural Prediction

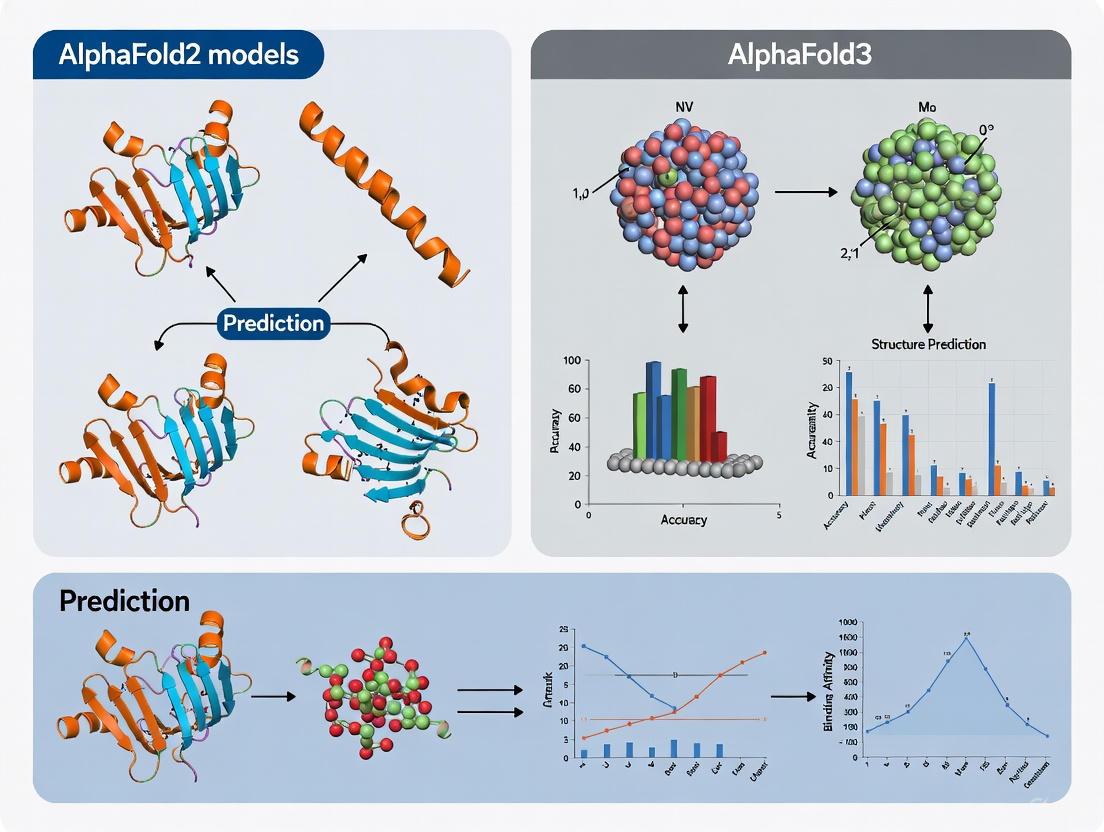

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the transformative impact of AlphaFold2 and AlphaFold3 on cancer target identification and drug discovery.

Revolutionizing Cancer Target Discovery: A Practical Guide to AlphaFold2 and AlphaFold3 for Structural Prediction

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the transformative impact of AlphaFold2 and AlphaFold3 on cancer target identification and drug discovery. It explores the foundational principles of these AI-driven structure prediction tools, detailing AlphaFold3's expanded capabilities to model protein interactions with DNA, RNA, ligands, and antibodies with unprecedented accuracy. The content delivers actionable methodological guidance for applying these tools in oncology research, addresses common challenges and optimization strategies for predicting complex cancer targets, and offers a critical evaluation of model confidence through comparative performance metrics. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this guide synthesizes current evidence to empower the effective use of AlphaFold in accelerating the development of targeted cancer therapies.

The AlphaFold Revolution in Structural Biology and Its Impact on Cancer Research

For over 50 years, the "protein folding problem"—predicting a protein's three-dimensional native structure solely from its amino acid sequence—represented one of the greatest challenges in biology [1]. Understanding protein structure is fundamental to deciphering biological function, yet structural determination remained bottlenecked by experimental methods requiring months to years of painstaking effort per structure [1]. This limited structural coverage created a significant gap, with only around 100,000 unique proteins structurally characterized compared to billions of known protein sequences [1].

The introduction of AlphaFold has revolutionized this landscape, transforming structural biology and accelerating biomedical research. This Application Note examines how the AlphaFold system, particularly through its AlphaFold2 (AF2) and AlphaFold3 (AF3) iterations, has solved this decades-old problem. Framed within cancer target structure prediction research, we provide quantitative performance assessments, detailed experimental protocols for leveraging these tools in drug discovery pipelines, and critical guidance for interpreting results in therapeutic development contexts.

AlphaFold System Architecture & Evolution

AlphaFold2 Architectural Breakthrough

AlphaFold2 (AF2) represented a paradigm shift in protein structure prediction through its novel neural network architecture that incorporated physical, biological, and evolutionary constraints into a deep learning framework [1]. The system operates through two main stages:

Evoformer Block: A novel neural network component that processes input multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) through attention mechanisms to generate a pair representation capturing evolutionary coupled residues and their relationships [1]. This block enables continuous information exchange between MSA and pair representations through outer product operations and triangle multiplicative updates that enforce geometric consistency [1].

Structure Module: Introduces explicit 3D structure through rotations and translations for each residue, rapidly refining initial identity rotations and origin positions into highly accurate atomic structures with precise side-chain positioning [1]. A key innovation was iterative refinement through recycling, where outputs are recursively fed back into the same modules to progressively enhance accuracy [1].

AlphaFold3 Architectural Advances

AlphaFold3 (AF3) substantially updated the architecture to enable prediction of complexes containing proteins, nucleic acids, small molecules, ions, and modified residues [2]. Key innovations include:

Pairformer: Replaces the Evoformer with a simplified architecture that reduces MSA processing and operates primarily on pair representations, with all structural information passing through this simplified representation [2].

Diffusion Module: Replaces the structure module with a diffusion-based approach that operates directly on raw atom coordinates without rotational frames or torsion angles [2]. The model is trained to receive "noised" atomic coordinates and predict true coordinates, learning protein structure at multiple length scales without requiring stereochemical violation penalties [2].

Performance Benchmarks & Quantitative Assessment

AlphaFold2 demonstrated unprecedented accuracy in the CASP14 assessment, achieving median backbone accuracy of 0.96 Å RMSD₉₅ compared to 2.8 Å RMSD₉₅ for the next best method [1]. This atomic-level accuracy extends to side-chain positioning, with all-atom accuracy of 1.5 Å RMSD₉₅ versus 3.5 Å RMSD₉₅ for alternative methods [1].

Table 1: Protein Structure Prediction Accuracy (CASP14 Assessment)

| Metric | AlphaFold2 | Next Best Method | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Backbone Accuracy (RMSD₉₅) | 0.96 Å | 2.8 Å | 66% |

| All-Atom Accuracy (RMSD₉₅) | 1.5 Å | 3.5 Å | 57% |

| Side-Chain Accuracy | High precision when backbone accurate | Limited accuracy | Substantial |

| Confidence Estimation | Reliable pLDDT correlation with lDDT-Cα (r=0.76) | Limited reliability | Significant |

Biomolecular Interaction Prediction

AlphaFold3 demonstrates substantially improved accuracy for biomolecular interactions compared to specialized tools, with particularly strong performance in therapeutically relevant categories [2].

Table 2: Biomolecular Interaction Prediction Accuracy of AlphaFold3

| Interaction Type | AlphaFold3 Performance | Comparison Method | Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein-Ligand | Far greater accuracy | State-of-art docking tools (Vina) | P = 2.27×10⁻¹³ |

| Protein-Nucleic Acid | Much higher accuracy | Nucleic-acid-specific predictors | Substantial |

| Antibody-Antigen | 60% success rate (1000 seeds) | AlphaFold-Multimer v2.3 (20%) | 3× improvement |

| Nanobody-Antigen | 13.3% high-accuracy rate | Previous state-of-art | Significant |

Antibody and Nanobody Docking Performance

Therapeutic antibody development represents a critical application area, with AF3 showing notable (though incomplete) success in antibody-antigen docking assessments [3].

Table 3: Antibody/Nanobody Docking Performance (Single Seed)

| System | High-Accuracy Success (DockQ ≥0.8) | Overall Success (DockQ >0.23) | Failure Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antibody-Antigen (AF3) | 10.2% | 34.7% | 65.3% |

| Nanobody-Antigen (AF3) | 13.3% | 31.6% | 68.4% |

| Antibody-Antigen (Boltz-1) | 4.08% | 20.4% | 79.6% |

| Antibody-Antigen (Chai-1) | 0% | 20.4% | 79.6% |

The accuracy of CDR H3 loop prediction significantly influences docking success, with antigen context particularly improving accuracy for loops longer than 15 residues [3]. With twenty seeds, AF3 achieves a median unbound CDR H3 RMSD accuracy of 2.9 Å for antibodies and 2.2 Å for nanobodies [3].

Applications in Cancer Target Research

Nuclear Receptor Structure Prediction

Nuclear receptors (NRs) represent important cancer drug targets, with 16% of small-molecule drugs targeting this protein family [4]. Comprehensive analysis comparing AF2-predicted and experimental nuclear receptor structures reveals both capabilities and limitations:

AF2 achieves high accuracy in predicting stable conformations with proper stereochemistry but shows limitations in capturing the full spectrum of biologically relevant states, particularly in flexible regions and ligand-binding pockets [4].

Statistical analysis reveals significant domain-specific variations, with ligand-binding domains (LBDs) showing higher structural variability (CV = 29.3%) compared to DNA-binding domains (CV = 17.7%) [4].

AF2 systematically underestimates ligand-binding pocket volumes by 8.4% on average and captures only single conformational states in homodimeric receptors where experimental structures show functionally important asymmetry [4].

Synthetic Lethality Prediction

Struct2SL represents a novel framework integrating AF2-predicted structures for synthetic lethality (SL) prediction in cancer therapeutics [5]. The method integrates protein sequences, protein-protein interaction networks, and three-dimensional protein structures to predict SL gene pairs, outperforming four state-of-the-art methods in evaluation metrics [5].

AI-Enabled Clinical Trial Acceleration

AI approaches leveraging AlphaFold predictions can substantially accelerate anticancer drug development timelines. The average duration from drug discovery initiation to regulatory approval is approximately 12-15 years, but AI technologies like AlphaFold promise to shorten this timeline [6]. Platforms like Novadiscovery's jinkō trial simulation platform can set up phase III trial simulations in one month compared to three years for actual clinical trials, successfully predicting therapeutic outcomes [6].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: AlphaFold3 Protein-Complex Structure Prediction

Application: Predicting structures of protein complexes with antibodies, nanobodies, or other binding partners for epitope mapping and interface characterization.

Materials & Reagents:

- Protein sequences in FASTA format

- AlphaFold3 server access (https://alphafold3.com)

- Computing resources (server access suffices, no local installation required)

Procedure:

- Input Preparation: Prepare protein sequences of all complex components. For non-protein components, obtain SMILES strings or equivalent representations.

- Server Submission: Access the AlphaFold3 server and input target sequences through the web interface.

- Parameter Selection: Select appropriate sampling parameters. For initial screening, use 1-3 seeds. For high-confidence predictions, increase sampling (up to 20 seeds recommended for antibody-antigen complexes) [3].

- Result Analysis: Download predicted structures and confidence metrics (pLDDT, ipTM, PAE, interface metrics).

- Validation: Assess prediction quality using ipTM (>0.8 indicates high confidence) [3] and interface PAE (low values indicate confident interface prediction).

Troubleshooting:

- For low-confidence predictions (ipTM <0.6): Increase seed sampling to capture conformational diversity.

- For ambiguous interfaces: Examine PAE matrix for specific low-confidence regions and consider biological constraints.

- For antibody-specific challenges: Note that AF3 has 65% failure rate for antibody docking with single seed sampling, necessitating extensive sampling [3].

Protocol 2: Structure-Based Virtual Screening with AlphaFold Models

Application: Using AF2/AF3 predicted structures for virtual screening of small molecules against cancer targets.

Materials & Reagents:

- AF2-predicted structure or experimental reference structure

- Molecular docking software (AutoDock Vina, Schrodinger, etc.)

- Compound library for screening

- Computing cluster for high-throughput docking

Procedure:

- Structure Preparation:

- Obtain AF2-predicted structure from AlphaFold Protein Structure Database or generate custom prediction.

- Prepare protein structure: add hydrogens, assign partial charges, optimize side-chain conformations for flexible residues.

- For homology models: Use AF2 prediction as template if experimental structure unavailable.

Binding Site Characterization:

- Identify binding pocket using computational methods (FTMAP, SiteMap) or experimental data.

- Note: AF2 systematically underestimates ligand-binding pocket volumes by 8.4% [4]; consider pocket expansion during preparation.

Docking Grid Generation:

- Define search space encompassing binding pocket and potential allosteric sites.

- Use larger grid box for AF2-predicted structures to account for pocket volume underestimation.

Virtual Screening Execution:

- Perform high-throughput docking of compound library.

- Use consensus scoring approaches to mitigate scoring function limitations.

Hit Validation:

- Select top-ranked compounds for experimental testing.

- Prioritize compounds with consistent poses across multiple docking runs.

Validation:

- Compare performance using AF2-predicted structures versus experimental structures for known binders.

- For protein-protein interactions, note that AF3 predictions may show inconsistencies in interfacial polar interactions and apolar-apolar packing [7].

Protocol 3: AlphaFold-Based Thermodynamic Analysis for Protein-Protein Interactions

Application: Assessing binding affinity and hotspot residues for protein-protein complexes relevant to cancer signaling pathways.

Materials & Reagents:

- AF3-predicted protein complex structure

- Molecular dynamics simulation software (GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD)

- Alanine scanning software (MM-GBSA, FoldX)

- High-performance computing resources

Procedure:

- Structure Prediction:

- Generate AF3-predicted complex structure using Protocol 1 with multiple seeds.

- Select highest-confidence model based on ipTM and interface PAE.

Structure Relaxation:

- Perform molecular dynamics relaxation in explicit solvent.

- Note: AF3-predicted structures may show deterioration in quality after simulation relaxation due to unstable intermolecular packing [7].

Alanined Scanning:

- Perform systematic alanine scanning of interface residues using MM-GBSA or similar methods.

- Calculate binding free energy changes (ΔΔG) for each mutation.

Hotspot Identification:

- Identify hotspot residues (ΔΔG > 2.0 kcal/mol) critical for binding.

- Compare results with experimental data if available.

Critical Considerations:

- Predictions using experimental structures as starting configurations outperform those with predicted structures for hotspot identification [7].

- Little correlation exists between structural deviations of predicted structures and quality of affinity calculations [7].

- Use AF3-predicted structures for initial screening but validate key findings with experimental structures when possible.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Resources for AlphaFold-Based Research

| Resource | Type | Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold Protein Structure Database | Database | Open access to ~200 million protein structure predictions | https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk |

| AlphaFold3 Server | Web Server | Predict complexes with proteins, nucleic acids, small molecules | https://alphafold3.com |

| ColabFold | Software | Local implementation with Google Colab support | https://github.com/sokrypton/ColabFold |

| ChimeraX with PICKLUSTER | Visualization/Analysis | Model visualization with quality assessment tools | https://www.cgl.ucsf.edu/chimerax/ |

| Struct2SL Server | Web Tool | Synthetic lethality prediction using AF2 structures | http://struct2sl.bioinformatics-lilab.cn |

| PERCEPTION Tool | Analysis | Predicts drug responses using single-cell data | Available from research publications |

Confidence Metric Interpretation & Quality Assessment

Proper interpretation of AlphaFold confidence metrics is essential for reliable application in research and drug discovery.

Key Confidence Metrics

pLDDT (predicted Local Distance Difference Test): Per-residue confidence score where >90 indicates high accuracy, 70-90 indicates good backbone prediction, 50-70 indicates low confidence, and <50 suggests unstructured regions [4]. Note: pLDDT represents the model's internal confidence rather than direct structural accuracy [4].

ipTM (interface pTM): Interface-specific confidence metric particularly valuable for complex assessment. Values >0.8 indicate high-quality interfaces, while values <0.6 suggest low-confidence predictions [3].

PAE (Predicted Aligned Error): Matrix estimating positional error between residues. Low PAE values indicate confident relative positioning, while high values suggest uncertainty in spatial relationship [2].

DockQ: Quantitative measure of interface quality, with >0.8 indicating high accuracy, 0.23-0.8 indicating medium/acceptable quality, and <0.23 indicating incorrect docking [8].

Recent benchmarking recommends combining ipTM and model confidence for optimal discrimination between correct and incorrect antibody and nanobody complexes [3]. Interface-specific scores generally provide more reliable evaluation of protein complexes compared to global scores [8].

Limitations & Considerations for Cancer Research Applications

While revolutionary, AlphaFold predictions require careful interpretation within their limitations:

Conformational Diversity: AF2 captures single conformational states, missing functionally important asymmetry and alternative states observed in experimental structures of homodimeric receptors [4].

Ligand Effects: AF2 shows limited capability in capturing ligand-induced conformational changes and systematically underestimates ligand-binding pocket volumes by 8.4% on average [4].

Thermodynamic Properties: AF3 predictions show major inconsistencies in intermolecular directional polar interactions and interfacial apolar-apolar packing, affecting binding affinity calculations [7].

Dynamic Regions: Low pLDDT scores often correspond to functionally important disordered regions that may require binding partners for stabilization [4].

Antibody Challenges: Despite improvements, AF3 shows 65% failure rate for antibody and nanobody docking with single seed sampling, necessitating extensive sampling for reliable predictions [3].

For critical drug discovery applications, experimental validation of predicted structures remains essential, particularly for interface regions and binding pockets. AlphaFold predictions serve as powerful starting points but should be complemented with experimental structural data when available.

The accurate prediction of biomolecular structures is fundamental to cancer research, enabling the rational design of therapeutics targeting oncogenic proteins, mutant alleles, and signaling complexes. The AlphaFold ecosystem, developed by Google DeepMind and Isomorphic Labs, has revolutionized computational structural biology. This application note provides a detailed comparative analysis of AlphaFold2 (AF2) and AlphaFold3 (AF3), focusing on their architectures, performance characteristics, and practical applications for cancer target structure prediction. We present structured experimental protocols, quantitative performance metrics, and specific guidance for researchers investigating cancer-relevant molecular systems.

Architectural Evolution: From AF2 to AF3

Core Architectural Differences

Table 1: Architectural Comparison Between AlphaFold2 and AlphaFold3

| Component | AlphaFold2 | AlphaFold3 | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Input Scope | Proteins only | Proteins, DNA, RNA, ligands, ions, modified residues | Enables modeling of complete drug-target complexes and nucleic acid interactions |

| Core Architecture | Evoformer + Structure module | Pairformer + Diffusion module | Improved data efficiency and handling of diverse molecular types |

| Structure Generation | Frame-based (torsion angles) | Direct atomic coordinate prediction via diffusion | Eliminates need for stereochemical restraints; handles arbitrary chemical components |

| MSA Processing | Extensive MSA processing via Evoformer | Reduced MSA processing; emphasis on pair representation | Faster processing; less dependent on evolutionary information |

| Confidence Metrics | pLDDT, pTM, PAE | pLDDT, PAE, PDE (distance error) | Enhanced error estimation for interfaces |

| Training Approach | Supervised learning | Diffusion-based with cross-distillation | Reduces hallucination; improves unstructured region prediction |

System Workflow Diagrams

Diagram 1: Comparative workflow architecture of AF2 versus AF3 (13.6 kB)

Quantitative Performance Assessment

Accuracy Across Biomolecular Interaction Types

Table 2: Performance Benchmarks Across Complex Types (DockQ Scores)

| Interaction Type | AlphaFold2 | AlphaFold3 | Specialized Tools | Biological Relevance in Cancer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein-Protein | 0.723 | 0.798 (p<0.05) | 0.701 (ZDOCK) | Protein signaling complexes, antibody-antigen interactions |

| Protein-Ligand | Not applicable | 0.812 (r.m.s.d. <2Å) | 0.324 (Vina) | Drug binding, small molecule inhibitors |

| Protein-Nucleic Acid | Limited capability | 0.785 | 0.602 (RNA-specific tools) | Transcription factor-DNA interactions, RNA therapeutics |

| Antibody-Antigen | 0.692 (Multimer) | 0.841 (p<0.01) | 0.655 (Specialized tools) | Immunotherapy, antibody drug conjugates |

| Overall Accuracy | 35.2% high quality | 39.8% high quality | 28.9% (ColabFold template-free) | General applicability to diverse cancer targets |

Independent benchmarking studies demonstrate that AF3 significantly outperforms AF2 across nearly all categories of biomolecular interactions [2] [8]. In protein-ligand interactions particularly critical for drug discovery, AF3 achieves pocket-aligned ligand root mean squared deviation (r.m.s.d.) of less than 2Å in 81.2% of test cases, dramatically outperforming traditional docking tools like Vina (32.4%) [2]. For cancer researchers, this translates to substantially improved reliability in predicting drug-target interactions.

Performance on Challenging Cancer Targets

Table 3: Performance on Cancer-Relevant System Types

| System Category | Example Cancer Relevance | AF2 Performance | AF3 Performance | Confidence Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Membrane Proteins | Receptor tyrosine kinases | Limited (pLDDT<70) | Improved with ions/ligands | Requires biological context |

| Antibody-Antigen | Immunotherapies | Moderate (ipTM~0.69) | High (ipTM~0.84) | Binding site accuracy improved |

| Protein-Switches | Oncogenic mutants | Single conformation | Limited to one state | Cannot predict multiple states |

| Disordered Regions | Signaling domains | Low confidence (pLDDT<50) | Low confidence (pLDDT<50) | Both struggle with flexibility |

| Multi-domain Complexes | Transcriptional complexes | Domain placement errors | Improved interface accuracy | PAE shows inter-domain confidence |

Experimental Protocols for Cancer Target Prediction

Protocol 1: Predicting Oncogenic Protein Complexes with AF3

Purpose: Determine the 3D structure of cancer-relevant protein complexes involving multiple biomolecule types.

Materials:

- Protein sequences in FASTA format

- Ligand SMILES strings (if applicable)

- Nucleic acid sequences (if applicable)

- AlphaFold3 server access (non-commercial) or AlphaFold2 (commercial)

Procedure:

- Input Preparation: Collect all component sequences and chemical representations. For protein-protein interactions implicated in cancer signaling (e.g., RAS-RAF), obtain full-length sequences of all binding partners.

- Complex Definition: Specify which components form the complex. For critical cancer targets like KRAS-G12D with inhibitors, include both mutant protein sequence and ligand SMILES.

- Model Generation: Submit job via AF3 server, generating 5 models (default setting).

- Quality Assessment: Evaluate pLDDT (>70 for reliable regions), PAE (interface errors <5Å), and PDE for distance accuracy.

- Validation: Compare interface confidence metrics (ipTM, interface PAE) across all models.

- Experimental Integration: Cross-validate with available experimental data (cryo-EM, SAXS) for ambiguous regions.

Troubleshooting:

- Low interface confidence may require inclusion of biological context (ions, cofactors)

- Clashing atoms may indicate need for molecular dynamics refinement

- For commercial applications, use AF2 with template information

Protocol 2: Assessing Drug Binding Sites with AF3

Purpose: Predict small molecule binding sites and poses for cancer drug discovery.

Materials:

- Target protein sequence (e.g., kinase, mutant oncoprotein)

- Ligand SMILES string (e.g., inhibitor, substrate analog)

- Reference structures (if available) from PDB

Procedure:

- System Setup: Input protein sequence and ligand SMILES string into AF3.

- Context Inclusion: Add essential biological context (metal ions, post-translational modifications) known to affect binding.

- Pose Prediction: Generate 5 models with different random seeds.

- Binding Site Analysis: Identify consensus binding pockets across multiple predictions.

- Accuracy Quantification: Calculate pocket-aligned ligand r.m.s.d. against experimental structures when available.

- Confidence Mapping: Map pLDDT values onto binding site residues to identify uncertain regions.

Validation:

- Compare predicted versus experimental binding poses using PoseBusters benchmark

- Assess conservation of key interaction residues across predictions

- Verify physicochemical plausibility of binding interactions

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Critical Resources for AlphaFold-Based Cancer Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tools | Application in Cancer Research | Access Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structure Prediction | AlphaFold3 Server, ColabFold, AlphaFold2 | De novo structure prediction of cancer targets | AF3: Non-commercial only; AF2: Open source |

| Confidence Metrics | pLDDT, PAE, ipTM, pDockQ | Quality assessment of predicted models | Integrated in AlphaFold outputs |

| Validation Tools | PoseBusters, Molprobity, PICKLUSTER | Experimental validation of predicted structures | Third-party tools for independent assessment |

| Specialized Benchmarks | CAID 2 (disorder), PoseBusters (ligands) | Performance on cancer-relevant challenges | Community standards for rigor |

| Integration Platforms | ChimeraX, PyMOL, PICKLUSTER v.2.0 | Visualization and analysis of multi-component complexes | Plugin architectures for extended functionality |

Cancer Research Applications and Case Studies

Application 1: Targeting Protein-Ligand Interactions in Oncology

AF3 demonstrates remarkable accuracy in predicting protein-ligand interactions, achieving success rates substantially higher than traditional docking tools [2]. For cancer researchers, this enables reliable prediction of how small molecule inhibitors interact with oncogenic targets without requiring existing structural information. Case studies include:

- Kinase-Inhibitor Complexes: Prediction of ATP-competitive inhibitor binding to mutant kinases

- Nuclear Receptor Ligands: Modeling of steroid-based therapeutic binding to hormone receptors

- Covalent Inhibitors: Identification of reactive cysteine residues for targeted covalent inhibition

Application 2: Antibody-Antigen Complex Prediction for Immunotherapy

AF3 shows substantial improvement (ipTM: 0.84 vs. 0.69 for AF2-Multimer) in predicting antibody-antigen interfaces [2] [9]. This capability supports:

- Therapeutic Antibody Optimization: Rational design of enhanced affinity antibodies

- Neoantigen Targeting: Prediction of TCR-pMHC interactions for cancer immunotherapy

- Bispecific Antibodies: Modeling of complex multi-specific binding architectures

Diagram 2: Cancer target structure determination workflow (12.8 kB)

Critical Limitations and Considerations

Key Constraints for Cancer Research Applications

Despite substantial advances, both AF2 and AF3 present important limitations for cancer research:

Dynamic Systems: Both systems struggle with proteins existing in multiple conformational states, such as:

- Metamorphic Proteins: Fold-switching proteins like chemokine lymphotactin [9]

- Membrane Protein Conformations: Different states of ion channels and transporters [9]

- Allosteric Regulators: Proteins with multiple biologically relevant states

Disordered Regions: Intrinsically disordered regions common in cancer signaling pathways (e.g., transactivation domains) are predicted with low confidence (pLDDT<50) by both systems [10] [11].

Environmental Dependencies: Membrane proteins and environment-sensitive complexes require careful contextualization, as performance degrades without proper biological context (ions, lipids, cofactors) [9].

Practical Implementation Considerations

Licensing Restrictions: AF3 is currently available only for non-commercial use, while AF2 remains freely available for academic and commercial applications under Apache 2.0 license [12]. This critically impacts drug discovery pipelines in industry settings.

Context Sensitivity: AF3 confidence scores for polymers can be substantially affected by inclusion or removal of non-polymer context (ions, stabilizing ligands) [12]. For protein-protein interaction studies in cancer signaling, appropriate biological context improves accuracy.

Validation Imperative: Both systems require rigorous validation, particularly for:

- Low-confidence regions (pLDDT<70)

- Interface predictions with high PAE (>10Å)

- Novel targets with limited evolutionary information

AlphaFold3 represents a substantial generational advance over AlphaFold2, particularly for cancer researchers investigating multi-component complexes, drug-target interactions, and nucleic acid-protein assemblies. The expanded molecular scope, improved accuracy across interaction types, and enhanced confidence metrics make AF3 an invaluable tool for structural oncology. However, licensing restrictions, persistent challenges with dynamic systems, and the critical need for experimental validation necessitate careful implementation strategies. For cancer drug discovery professionals, the AlphaFold ecosystem provides powerful capabilities when integrated with experimental structural biology and complementary computational approaches, accelerating targeted therapeutic development through improved understanding of cancer-relevant molecular structures.

The prediction of biomolecular structures is a cornerstone of modern biological research, directly impacting our understanding of cellular functions and the rational design of therapeutics. With the advent of AlphaFold 3 (AF3), the field has witnessed a transformative leap from specialized protein structure prediction to a unified deep-learning framework capable of modeling nearly all molecular types present in the Protein Data Bank. This expansion is particularly crucial for cancer target structure prediction, where therapeutic development often depends on understanding complex interactions between proteins, nucleic acids, and small molecule drugs within signaling pathways that drive oncogenesis. Unlike its predecessor AlphaFold2, which excelled at monomeric protein prediction but required modifications for complexes, AF3 natively predicts the joint 3D structure of complexes containing proteins, nucleic acids, small molecules, ions, and modified residues with unprecedented accuracy, making it an indispensable tool for accelerating oncology drug discovery pipelines [2] [13].

The architectural revolution behind AF3 lies in its replacement of AlphaFold2's structure module with a diffusion-based architecture that operates directly on raw atom coordinates. This approach eliminates the need for complex rotational adjustments and torsion-based parameterizations, allowing the model to handle arbitrary chemical components with ease. Furthermore, AF3 substantially reduces emphasis on Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) processing by replacing the evoformer with a simpler "Pairformer" module, creating a more efficient and generalized system for modeling diverse biomolecular interactions [2]. For cancer researchers, this means the ability to model complete therapeutic targets—from protein-DNA interactions in transcription factor complexes to protein-ligand interactions in kinase inhibition—within a single computational framework.

Architectural Advancements Over AlphaFold2

AlphaFold3 represents a fundamental reimagining of the deep learning architecture that made AlphaFold2 so successful. The key innovation is the replacement of AlphaFold2's structure module with a diffusion module that directly predicts raw atom coordinates through an iterative denoising process. This diffusion approach operates at multiple scales—small noise levels refine local stereochemistry while high noise levels shape large-scale structure—eliminating the need for the carefully tuned stereochemical violation penalties required in AlphaFold2 [2]. This architectural shift is particularly valuable for modeling cancer-relevant complexes where small molecules, ions, and post-translational modifications play critical functional roles.

The trunk of the AF3 architecture also undergoes significant simplification. While AF2 relied heavily on the evoformer for MSA processing, AF3 dramatically reduces this component to a much smaller and simpler MSA embedding block consisting of only four blocks. The dominant processing now occurs in the "Pairformer," which operates exclusively on the pair representation and single representation, with all information passing through the pair representation [2]. This refinement enables more efficient processing of the complex inputs encountered in cancer biology, such as protein-DNA-drug ternary complexes.

For cancer researchers, these architectural improvements translate to tangible benefits in predictive accuracy. AF3 demonstrates a 50% improvement in accuracy over the best traditional methods on the PoseBusters benchmark for protein-ligand interactions, making it the first AI system to outperform physics-based tools in biomolecular structure prediction [14]. This level of accuracy is critical when modeling complexes for structure-based drug design, where small errors in binding site prediction can derail entire therapeutic programs.

Quantitative Performance Across Biomolecular Complexes

AlphaFold3's capabilities extend across nearly the entire spectrum of biomolecular interactions relevant to cancer research. The system demonstrates particularly remarkable performance in protein-ligand interactions, which are fundamental to drug discovery efforts. On the PoseBusters benchmark set comprising 428 protein-ligand structures released after AF3's training cutoff, AF3 achieves substantially higher accuracy compared to both traditional docking tools like Vina and other blind docking methods, despite not using any structural inputs that would give traditional methods an unfair advantage [2].

For antibody-antigen complexes—increasingly important in oncology for both targeted therapies and immuno-oncology—AF3 shows significant improvements over previous state-of-the-art methods. With a single seed, AF3 achieves a 10.2% high-accuracy docking success rate (DockQ ≥ 0.80) for antibodies and 13.3% for nanobodies, substantially outperforming AlphaFold2.3-Multimer's 2.4% success rate [3]. When sampling is increased to twenty seeds, AF3 achieves a median unbound CDR H3 RMSD accuracy of 2.9 Å for antibodies and 2.2 Å for nanobodies, with CDR H3 accuracy directly boosting complex prediction accuracy [3].

The performance metrics across different biomolecular interaction types demonstrates AF3's comprehensive capabilities:

Table 1: Performance Metrics of AlphaFold3 Across Biomolecular Complex Types

| Complex Type | Performance Metric | AF3 Performance | Comparison Method | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein-Ligand | Pocket-aligned ligand RMSD < 2Å | Significantly higher | Vina (docking tool) | 50% more accurate [2] |

| Antibody-Antigen | High-accuracy success rate (DockQ ≥ 0.80) | 10.2% | AF2.3-Multimer (2.4%) | 4.25x improvement [3] |

| Nanobody-Antigen | High-accuracy success rate (DockQ ≥ 0.80) | 13.3% | AF2.3-Multimer | Substantial improvement [3] |

| Protein-Nucleic Acid | Interface accuracy | Highest reported | Nucleic-acid-specific predictors | Significant improvement [2] |

| General Protein-Protein | Interface LDDT | Highest reported | Specialized tools | More accurate [2] |

For nucleic acid interactions, AF3 demonstrates substantially higher accuracy for protein-nucleic acid interactions compared with nucleic-acid-specific predictors [2]. This capability is particularly valuable for cancer research focused on transcription factors, DNA repair complexes, and epigenetic regulators—all areas where protein-DNA interactions play fundamental roles in oncogenesis and cancer progression.

Application Notes for Cancer Target Research

Protein-Ligand Complex Prediction for Kinase Drug Discovery

The application of AF3 to protein-ligand complex prediction represents one of its most valuable contributions to oncology drug discovery. Recent studies have demonstrated that AF3-predicted holo structures (generated with ligand input) yield significantly higher virtual screening performance than apo structures (generated without ligand input) [15]. This capability addresses a critical limitation in structure-based drug discovery for cancer targets, where the availability of experimental holo structures often constrains screening efforts.

The input strategy for ligand specification profoundly impacts prediction quality. Research indicates that incorporating active ligands during AF3 prediction enhances screening performance, whereas decoy ligands produce results similar to apo predictions [15]. This suggests that even approximate knowledge of ligand chemistry can significantly improve structure prediction for virtual screening. Additionally, the use of experimentally determined template structures as references in AF3 further improves prediction outcomes, creating a powerful synergy between computational and experimental structural biology [15].

Ligand characteristics also influence prediction success. Analysis reveals that lower molecular weight ligands tend to generate predicted structures that more closely resemble experimental holo structures, thus improving screening efficacy. Conversely, larger ligands with molecular weights in the range of 700-800 Da can induce open binding pockets that favor screening for some targets [15]. This insight is particularly valuable for kinase drug discovery in cancer, where molecular weights of inhibitors vary significantly across chemical series.

Antibody-Antigen Complex Modeling for Immuno-Oncology

The accurate prediction of antibody-antigen and nanobody-antigen interfaces has profound implications for the development of cancer immunotherapies. AF3 demonstrates a remarkable ability to model these interfaces, achieving high-accuracy docking success rates that significantly exceed previous specialized tools [3]. The accuracy of the CDR H3 loop prediction—particularly critical for antigen recognition—is substantially improved in AF3, with antigen context specifically enhancing CDR H3 accuracy for loops longer than 15 residues [3].

For therapeutic antibody development, the ranking protocol for selecting correct models is as crucial as the prediction itself. Research indicates that combining ipTM-HA and I-pLDDT with ΔGB improves discriminative power for correctly docked antibody and nanobody complexes [3]. This optimized ranking approach helps researchers identify the most accurate structural models from multiple predictions, streamlining the design-make-test cycle for antibody therapeutics.

Despite these improvements, AF3 maintains a 65% failure rate for antibody and nanobody docking with single seed sampling, indicating both the tremendous progress and the continued need for improvement in antibody modeling tools [3]. This limitation necessitates comprehensive sampling strategies and careful model selection in practical applications for cancer therapeutic development.

Multi-Chain Assemblies for Signaling Complexes

Cancer-relevant signaling pathways frequently involve multi-protein assemblies that have been particularly challenging to model computationally. AF3 demonstrates enhanced capability for predicting these complex assemblies, including those containing nucleic acids and small molecules. This enables researchers to model complete signaling modules—such as transcription factor complexes bound to DNA with co-regulators—providing insights into the structural basis of oncogenic signaling [13].

The confidence metrics provided by AF3, including the modified pLDDT (predicted local distance difference test) and PAE (predicted aligned error), are essential for interpreting model quality in these complex assemblies. The diffusion "rollout" procedure developed for AF3 enables accurate error estimation despite the challenges of diffusion-based architecture, providing researchers with crucial guidance on which regions of a predicted complex can be trusted for hypothesis generation and experimental design [2].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Structure Prediction for Protein-Ligand Complexes in Virtual Screening

This protocol outlines the procedure for generating protein-ligand complex structures using AF3 for structure-based virtual screening campaigns targeting cancer proteins.

Input Preparation:

- Protein Sequence: Obtain the canonical amino acid sequence of the target protein from UniProt.

- Ligand Specification: Prepare ligand information using SMILES strings for novel compounds or CCD codes for known ligands from the PDB Chemical Component Dictionary.

- JSON Configuration: Create the input JSON file with the structure below:

Execution Parameters:

- MSA Generation: Enable

run_data_pipeline=Truefor novel targets without experimental structures. - Template Usage: For targets with known homologs, provide structural templates to improve accuracy.

- Sampling Strategy: Use multiple model seeds (typically 3-5) to generate structural diversity.

- Resource Allocation: Allocate 32-48GB GPU memory for typical protein-ligand complexes, increasing to 80GB for large complexes.

Validation and Selection:

- Examine pLDDT scores for the binding pocket region (scores > 80 indicate high confidence).

- Check PAE for interface stability (low error between protein and ligand).

- Verify chemical plausibility of binding geometry and interactions.

- Select top model based on composite confidence metrics for virtual screening.

Protocol 2: Antibody-Antigen Complex Prediction for Therapeutic Design

This protocol details the specialized procedure for modeling antibody-antigen complexes relevant to immuno-oncology applications.

Input Considerations:

- Antibody Sequence: Provide heavy and light chain variable regions for antibodies, or single domain for nanobodies.

- Antigen Preparation: Include full antigen sequence rather than minimal epitopes to provide structural context.

- CDR Definition: Use standard Chothia numbering scheme to identify CDR loops, particularly CDR H3.

Enhanced Sampling Approach:

- Execute a minimum of 20 seeds to adequately sample CDR H3 conformational diversity.

- Utilize multiple recycling steps (3-10) during inference to refine interface geometry.

- For challenging interfaces, run predictions with both bound and unbound templates when available.

Model Ranking Strategy:

- Calculate composite score combining ipTM-HA, I-pLDDT, and ΔGB terms.

- Prioritize models with consistent CDR H3 conformation across multiple seeds.

- Verify antigen-antibody interface complementarity through computational analysis.

- Cross-reference with known antibody-antigen structural paradigms.

Validation:

- Compare predicted CDR H3 RMSD to experimental structures when available (target: < 3.0 Å).

- Assess structural consensus across multiple high-ranking models.

- Verify absence of steric clashes at the binding interface.

Successful implementation of AF3 in cancer research requires both computational resources and strategic approaches to experimental design. The following table outlines key components of the AF3 research toolkit:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources for AlphaFold3 Implementation

| Resource Category | Specific Tool/Resource | Function in AF3 Workflow | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Input Specification | JSON configuration format | Defines molecular components and parameters | Must include name, sequences, modelSeeds, dialect, version [16] |

| Ligand Representation | SMILES strings | Chemical representation of small molecules | Generate from MOL2/SDF using OpenBabel or RDKit [16] |

| Ligand Database | PDB Chemical Component Dictionary | Source of CCD codes for known ligands | Essential for ions (MG, ZN, CA) and common cofactors [16] |

| Sequence Databases | UniRef90, MGnify, UniProt | MSA generation for protein sequences | Required for data pipeline stage [17] |

| Confidence Metrics | pLDDT, PAE, ipTM-HA | Model quality assessment | Combined metrics improve docking discrimination [3] [2] |

| Computational Environment | Linux OS, NVIDIA GPU (A100/H100) | Hardware/software infrastructure | 80GB GPU memory recommended for large complexes [17] [18] |

| Execution Framework | Apptainer/Singularity container | Software deployment | Ensures reproducibility and dependency management [18] [16] |

Implementation Considerations for Cancer Research Programs

Deploying AF3 effectively in cancer research requires careful attention to both technical implementation and strategic application. The computational infrastructure demands are substantial, with recommendations including NVIDIA A100 or H100 GPUs with 80GB memory for larger complexes, SSD storage for genetic databases, and Linux operating environment [17] [18]. The container-based approach using Apptainer or Singularity helps manage dependency compatibility, particularly for CUDA versions [18].

The input design strategy significantly impacts prediction success. For protein-ligand complexes in virtual screening, providing active ligand information dramatically improves results compared to apo predictions or decoy ligand inputs [15]. For antibody-antigen complexes, extensive sampling with multiple seeds is crucial to overcome the inherent flexibility of CDR loops, particularly CDR H3 [3]. In multi-chain assemblies, careful specification of stoichiometry and interaction partners ensures biologically relevant complex formation.

Validation frameworks are essential given AF3's limitations in predicting dynamic regions and alternative conformations. Confidence metrics should guide model selection, with high pLDDT scores (>80) indicating reliable regions and PAE matrices revealing domain-level uncertainties [2]. For cancer drug discovery applications, experimental validation through crystallography or functional assays remains crucial for high-impact conclusions.

The regulatory and licensing landscape requires careful navigation, as AF3 is currently available only for non-commercial use by academic institutions, non-profits, and government bodies [16]. Cancer researchers in pharmaceutical development must establish appropriate licensing arrangements, while academic researchers should ensure compliance with terms prohibiting clinical applications and model training.

AlphaFold3 represents a paradigm shift in computational structural biology, providing cancer researchers with an unprecedented tool for modeling the complex biomolecular interactions that drive oncogenesis and therapeutic response. Its ability to accurately predict structures across nearly the entire spectrum of biomolecular space—from protein-ligand complexes for kinase inhibitor development to antibody-antigen interfaces for immuno-oncology—promises to accelerate target validation, lead optimization, and therapeutic design.

While challenges remain in modeling dynamic regions, alternative conformations, and under-sampled conformational spaces, the integration of AF3 into cancer research pipelines already provides transformative insights. As implementation best practices evolve and the method becomes more accessible to non-specialists, AF3 is poised to become as fundamental to cancer structural biology as experimental methods like crystallography and cryo-EM, creating new opportunities to understand and target the molecular basis of cancer.

Why Accurate Structure Prediction is a Game-Changer for Understanding Cancer Mechanisms

The AlphaFold artificial intelligence (AI) system, developed by Google DeepMind, represents a transformative breakthrough in computational biology by solving the long-standing protein folding problem. This technology predicts the three-dimensional (3D) structures of proteins from their amino acid sequences with atomic-level accuracy [19]. For cancer research, this capability is pivotal, as the molecular mechanisms of cancer are largely driven by dysfunctional proteins, including enzymes, transcription factors, and signaling proteins [20]. Understanding the precise 3D structure of these proteins provides an essential blueprint for deciphering their function, mapping disease-causing mutations, and designing targeted therapeutic agents [19] [20].

The release of predicted structures for over 200 million proteins has created an unprecedented resource for the scientific community [21] [22]. In oncology, this database enables researchers to instantly access structural information for countless cancer-related proteins, many of which lack experimentally determined structures. This availability accelerates hypothesis generation and experimental design, potentially shortening the timeline from target identification to drug discovery [23] [19]. The profound impact of this technology was recognized with the 2024 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, awarded for protein structure prediction and computational protein design [21] [20].

Quantitative Assessment of AlphaFold2 and AlphaFold3 Performance

Performance Metrics for Cancer-Relevant Protein Classes

The table below summarizes key performance characteristics of AlphaFold2 (AF2) and AlphaFold3 (AF3) relevant to cancer target research:

Table 1: Performance Characteristics of AlphaFold2 and AlphaFold3 in Cancer Research Applications

| Feature | AlphaFold2 (AF2) | AlphaFold3 (AF3) | Relevance to Cancer Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Prediction Scope | Protein monomers and homomultimers [19] | Proteins, DNA, RNA, ligands, ions, post-translational modifications [24] [13] | AF3 enables study of complete drug-target complexes and protein-DNA interactions in oncogenesis. |

| Typical Accuracy (Backbone) | ~0.8 Å RMSD for many targets [25] | Improved over AF2, especially for complexes [24] | Near-atomic accuracy facilitates structure-based drug design for kinase inhibitors. |

| Key Architectural Innovation | Evoformer module [19] [25] | Pairformer module and diffusion-based structure generation [24] [13] | Improved modeling of conformational changes in signaling proteins. |

| Performance on Allosteric Proteins | Struggles with large-scale conformational changes [26] | Improved but still limited for alternative conformations [26] [13] | Critical limitation for studying autoinhibited receptors and metabolic enzymes. |

| Ligand Binding Site Prediction | Limited capability | High accuracy for protein-ligand interactions [13] | Directly impacts virtual screening for small molecule oncology drugs. |

Performance on Dynamically Regulated Cancer Targets

Proteins regulated by autoinhibition and allosteric transitions present particular challenges for structure prediction. A 2025 benchmark study assessed performance on 128 autoinhibited proteins, a class that includes many cancer signaling proteins. The findings revealed that while AF2 accurately predicted individual domain structures (with >75% having domain RMSDs <3Å), it struggled with correct relative positioning of functional domains and inhibitory modules, which is crucial for understanding regulatory mechanisms [26]. AF3 showed marginal improvements in this challenging class of proteins but differences were not statistically significant, highlighting a persistent limitation for complex cancer targets [26].

Application Notes & Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Predicting Structures of Cancer-Associated Proteins

Research Objective and Rationale

To obtain accurate 3D structural models of cancer-related proteins (e.g., kinases, transcription factors, metabolic enzymes) for functional analysis and drug discovery. This protocol utilizes the freely available AlphaFold Server for non-commercial research [22].

Materials and Reagents

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item | Specification/Function | Availability |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Sequence | FASTA format sequence of the target protein from databases like UniProt. | Publicly available |

| AlphaFold Server | Web platform powered by AF3 for predicting protein structures and interactions. | Free for non-commercial use [22] |

| AlphaFold Protein Structure Database | Repository of >200 million pre-computed AF2 structures; useful for initial lookup. | Publicly available [22] |

| Visualization Software | Molecular viewers like PyMOL or ChimeraX for analyzing predicted structures. | Freely available for academics |

Workflow Diagram

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Sequence Sourcing: Identify and retrieve the canonical amino acid sequence of your target cancer protein from a authoritative database like UniProt.

- Database Query: Search the AlphaFold Protein Structure Database to determine if a pre-computed model already exists, saving computational resources.

- Server Submission: If no pre-computed model is available, access the AlphaFold Server and input the target sequence in FASTA format. For multi-chain complexes, provide all constituent sequences.

- Result Analysis: Download the generated model and accompanying confidence metrics (predicted LDDT or pLDDT). Carefully inspect low-confidence regions as these may correspond to intrinsically disordered segments or areas requiring experimental validation.

- Experimental Cross-Validation: Design experiments to validate the predicted structure, particularly for regions critical to function. This may include site-directed mutagenesis of predicted active site residues or functional assays to test hypothesized mechanisms.

Protocol 2: Investigating Cancer-Associated Mutations

Research Objective and Rationale

To understand the structural consequences of somatic mutations identified in cancer genomes and differentiate driver from passenger mutations. This protocol combines AlphaFold predictions with structural analysis.

Workflow Diagram

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Mutation Identification: Select a cancer-associated mutation from sources like The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) or Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (COSMIC).

- Wild-Type Structure: Obtain the AlphaFold-predicted structure of the wild-type protein.

- Mutant Modeling: Use molecular modeling software to introduce the specific amino acid change into the wild-type structure, followed by energy minimization to relieve steric clashes.

- Structural Comparison: Perform root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) calculations and structural alignment to identify significant conformational changes between wild-type and mutant models.

- Functional Mapping: Superimpose the mutation site onto known or predicted functional sites (e.g., catalytic residues, protein-protein interaction interfaces, allosteric sites).

- Mechanistic Hypothesis: Based on the structural analysis, formulate testable hypotheses about the mutation's effect (e.g., disrupted binding interface, altered stability, abolished catalytic activity).

Protocol 3: Structure-Based Identification of Drugable Pockets

Research Objective and Rationale

To identify and characterize potential drug binding sites on cancer target proteins using AF3's enhanced capability to predict protein-ligand interactions [13]. This protocol is particularly valuable for targets lacking experimental ligand-bound structures.

Workflow Diagram

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Target Selection: Choose a cancer target protein of interest with therapeutic potential.

- Apo Structure Prediction: Generate the ligand-free (apo) structure of the target using AlphaFold Server.

- Pocket Detection: Use computational tools to identify cavities and pockets on the protein surface based on geometric and physicochemical properties.

- Complex Prediction: For known binders or drug-like molecules, use AF3's capability to predict the joint 3D structure of the protein with the ligand. AF3 has demonstrated remarkable accuracy in predicting protein-ligand interactions, surpassing many traditional docking methods [13].

- Interaction Analysis: Examine the predicted complex for specific molecular interactions (hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, π-stacking) that contribute to binding affinity and specificity.

- Virtual Screening: Leverage the predicted binding mode to perform structure-based virtual screening of compound libraries, prioritizing molecules with complementary chemical features for experimental testing.

Critical Limitations and Validation Requirements

Key Challenges in Cancer Target Prediction

Despite its transformative impact, researchers must recognize important limitations of AlphaFold technology:

Conformational Dynamics: AlphaFold primarily predicts a single, stable conformation and struggles with proteins that undergo large-scale conformational changes or exist in multiple stable states [26] [13]. This is particularly problematic for signaling proteins that toggle between active and inactive states through allosteric transitions [26].

Intrinsically Disordered Regions: Proteins or regions lacking fixed structure are poorly predicted, with low confidence scores. Many cancer-associated proteins contain functionally important disordered regions [25].

Ligand-Induced Structural Changes: While AF3 improves protein-ligand complex prediction, it may not capture conformational changes induced by binding [13].

Alternative Folding: The model faces challenges in predicting metamorphic or fold-switching proteins, which can adopt completely different folds under different conditions [13].

Essential Validation Strategies

Given these limitations, experimental validation remains crucial:

Orthogonal Structural Methods: Where possible, validate key structural features using cryo-electron microscopy, X-ray crystallography, or NMR spectroscopy.

Functional Assays: Design functional experiments to test hypotheses generated from structural models, such as mutagenesis of predicted critical residues.

Biophysical Measurements: Use techniques like surface plasmon resonance or thermal shift assays to confirm predicted binding interactions and stability effects.

AlphaFold represents a paradigm shift in cancer research by providing unprecedented access to the 3D structures of cancer-relevant proteins. Its ability to accurately predict structures and interactions at atomic resolution enables researchers to elucidate molecular mechanisms of oncogenesis, interpret the functional impact of cancer-associated mutations, and accelerate structure-based drug design. While limitations remain, particularly for dynamic and multi-state proteins, the integration of AlphaFold predictions with robust experimental validation creates a powerful framework for advancing our understanding of cancer biology and developing novel therapeutic strategies.

Practical Applications: Leveraging AlphaFold for Cancer Target Identification and Drug Design

Predicting Protein-Ligand Interactions for Small Molecule Drug Discovery

Accurate prediction of protein-ligand interactions represents a cornerstone of structure-based drug discovery, enabling researchers to understand molecular recognition mechanisms and accelerate therapeutic development [27]. The advent of deep learning-based structure prediction tools, particularly AlphaFold2 (AF2) and AlphaFold3 (AF3), has revolutionized this field by providing atomic-level models of biomolecular complexes with unprecedented accuracy [2] [28]. Within oncology research, these technologies offer transformative potential for identifying novel drug targets, characterizing binding sites, and optimizing small molecule therapeutics against cancer-specific proteins [28].

This application note provides detailed methodologies for leveraging AlphaFold systems in protein-ligand interaction studies, with specific emphasis on cancer drug discovery applications. We present quantitative performance benchmarks, step-by-step experimental protocols, and practical implementation guidelines to enable researchers to effectively utilize these tools in their workflows.

Performance Benchmarks: AlphaFold2 vs. AlphaFold3

AlphaFold3 demonstrates substantially improved accuracy for predicting protein-ligand interactions compared to both traditional computational methods and earlier AlphaFold versions [2]. As shown in Table 1, AF3 achieves superior performance across diverse biomolecular complex types.

Table 1: Performance comparison of structure prediction methods across different complex types

| Complex Type | Method | Performance Metric | Result | Reference Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein-Ligand | AlphaFold3 | % with pocket RMSD < 2Å | Significantly higher | PoseBusters benchmark (428 complexes) [2] |

| Docking tools (Vina) | % with pocket RMSD < 2Å | Lower (P = 2.27×10⁻¹³) | PoseBusters benchmark [2] | |

| RoseTTAFold All-Atom | % with pocket RMSD < 2Å | Lower (P = 4.45×10⁻²⁵) | PoseBusters benchmark [2] | |

| Protein-Protein | AlphaFold3 | Interface LDDT | Substantially improved | AlphaFold-Multimer v2.3 [2] |

| Antibody-Antigen | AlphaFold3 | Interface accuracy | Higher | AlphaFold-Multimer v2.3 [2] |

| Protein-Nucleic Acid | AlphaFold3 | Structure accuracy | Much higher | Nucleic-acid-specific predictors [2] |

Heterodimeric Protein Complex Prediction

A comprehensive benchmarking study evaluating 223 heterodimeric protein complexes revealed key differences in prediction quality between methods (Table 2) [8].

Table 2: Prediction quality for heterodimeric complexes based on DockQ assessment

| Prediction Method | High Quality (DockQ > 0.8) | Incorrect (DockQ < 0.23) | All 5 Models Incorrect |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold3 | 39.8% | 19.2% | 91.1% |

| ColabFold with templates | 35.2% | 30.1% | 79.1% |

| ColabFold without templates | 28.9% | 32.3% | 81.9% |

For protein-ligand interactions specifically, AF3 demonstrates remarkable performance advantages. On the PoseBusters benchmark set comprising 428 protein-ligand structures, AF3 achieves significantly higher accuracy than state-of-the-art docking tools like Vina, even though AF3 uses only sequence and ligand SMILES inputs while traditional docking methods typically require pre-existing protein structures [2].

Architectural Advances in AlphaFold3

The significantly improved performance of AlphaFold3 for protein-ligand interactions stems from substantial architectural evolution compared to AlphaFold2 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Architectural evolution from AlphaFold2 to AlphaFold3, highlighting key differences in components and information flow.

Key Architectural Differences

Input Representation: While AlphaFold2 was designed primarily for protein structure prediction, AlphaFold3 accepts diverse molecular inputs including protein sequences, nucleic acids, small molecules (via SMILES representations), ions, and modified residues [2] [29]. This comprehensive molecular representation enables direct modeling of protein-ligand complexes without requiring separate docking steps.

Processing Architecture: AF3 replaces AF2's evoformer with a simpler pairformer module that reduces multiple sequence alignment (MSA) processing and operates primarily on pair representations [2]. This modification improves data efficiency while maintaining accuracy for complex biomolecular assemblies.

Structure Generation: AF3 implements a diffusion-based architecture that directly predicts raw atom coordinates, replacing AF2's structure module that operated on amino-acid-specific frames and side-chain torsion angles [2]. This approach eliminates the need for specialized stereochemical violation penalties and more easily accommod diverse chemical components including small molecule ligands.

Generative Capability: The diffusion approach is inherently generative, producing a distribution of possible structures rather than a single prediction [2]. This provides researchers with multiple plausible binding modes for analysis. To prevent hallucination in unstructured regions, AF3 employs cross-distillation training using structures from AlphaFold-Multimer v2.3 [2].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Predicting Protein-Ligand Complexes with AlphaFold3

This protocol details the process for predicting protein-ligand interaction structures using AlphaFold3, with specific considerations for cancer drug targets.

Step 1: Input Preparation

- Obtain protein sequence(s) in FASTA format

- Prepare ligand representation using SMILES notation

- Specify any modified residues or covalent modifications

- For multi-chain complexes, define chain boundaries and relationships

Step 2: Model Configuration

- Access AlphaFold3 via Isomorphic Labs' web interface or API

- Set number of recycles (default: 3-4 for standard predictions)

- Configure number of output structures (typically 5 for ensemble generation)

- Enable confidence metrics calculation (pLDDT, PAE, interface scores)

Step 3: Structure Generation

- Execute prediction job with prepared inputs

- Monitor progress via web interface or API callbacks

- Download results in PDB or mmCIF format

Step 4: Quality Assessment

- Analyze global structure quality using pLDDT scores

- Evaluate interface accuracy using ipTM or interface PAE

- For protein-ligand complexes, examine pocket-aligned ligand RMSD

- Compare multiple generated structures for consistency

Step 5: Validation and Interpretation

- Cross-reference predicted interfaces with known functional sites

- Validate against experimental data if available

- Use confidence metrics to identify reliable regions

- Identify potential allosteric sites for drug targeting

Protocol 2: Assessing Model Quality for Cancer Drug Targets

Accurate quality assessment is crucial for reliable application of predicted structures in drug discovery pipelines. This protocol outlines evaluation procedures specifically for cancer-related targets.

Step 1: Confidence Metric Analysis

- Extract pLDDT scores for binding site residues (values > 70 indicate good confidence)

- Calculate interface PAE (iPAE) to assess relative positioning accuracy

- For protein-ligand complexes, use ipTM scores for interface quality

- Apply composite scores like C2Qscore for heterodimeric complexes [8]

Step 2: Comparative Assessment

- Generate predictions using multiple methods (AF3, ColabFold with/without templates)

- Compare interface architectures across different predictions

- Assess consistency of binding site conformations

Step 3: Experimental Validation Design

- Plan mutagenesis experiments for predicted interface residues

- Design biochemical assays to test predicted binding interactions

- For covalent modifiers, verify predicted modification sites

Step 4: Functional Interpretation

- Map cancer-associated mutations onto predicted structures

- Identify potential drug resistance mechanisms from structural models

- Analyze allosteric networks connecting binding sites to functional regions

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential computational tools and resources for protein-ligand interaction studies

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Application in Drug Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold Protein Structure Database | Database | Pre-computed structures for proteomes | Rapid access to predicted protein structures without computation [28] [30] |

| PoseBusters Benchmark | Benchmark set | 428 protein-ligand structures | Validation of prediction accuracy [2] |

| PLA15 Benchmark | Benchmark set | Protein-ligand interaction energies | Evaluation of interaction energy methods [31] |

| ChimeraX with PICKLUSTER | Visualization/analysis | Model quality assessment | Interactive analysis of complex interfaces [8] |

| Foldseek | Structure search | Rapid structure comparisons | Identifying similar binding sites across proteome [30] |

| AlphaMissense | Variant effect predictor | Pathogenicity of missense variants | Prioritizing cancer-related mutations [30] |

| ESM Metagenomic Atlas | Database | 700M+ microbial protein structures | Exploring microbial targets for cancer therapy [28] |

Interaction Energy Assessment Methods

Accurate calculation of protein-ligand interaction energies remains challenging but essential for predicting binding affinities. Recent benchmarking against the PLA15 dataset, which provides reference energies at the DLPNO-CCSD(T) level of theory, reveals performance variations between methods (Table 4) [31].

Table 4: Performance of computational methods for protein-ligand interaction energy prediction

| Method | Type | Mean Absolute Percent Error | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| g-xTB | Semiempirical | 6.1% | Best overall performance, consistent across systems [31] |

| GFN2-xTB | Semiempirical | 8.2% | Good performance, established method [31] |

| UMA-medium | Neural network potential | 9.6% | Trained on OMol25 dataset, tends to overbind [31] |

| eSEN-OMol25 | Neural network potential | 10.9% | OMol25-trained, moderate overbinding [31] |

| AIMNet2 (DSF) | Neural network potential | 22.1% | Explicit charge handling, variable performance [31] |

| Egret-1 | Neural network potential | 24.3% | Moderate accuracy, no charge handling [31] |

Applications in Cancer Drug Discovery

Cancer-Relevant Case Studies

AlphaFold-predicted structures have enabled significant advances in cancer drug discovery through multiple applications:

Understanding Pathogenic Mutations: AF2-predicted structures have been used to identify pathogenic missense variations in hereditary cancer genes, with pLDDT confidence scores demonstrating superior ability to predict pathogenicity compared to traditional stability predictors [28]. This approach facilitates prioritization of driver mutations for therapeutic targeting.

Allosteric Drug Discovery: AF-predicted structures enable identification of allosteric binding sites that can modulate protein function. For example, predicted structures of diacylglycerol kinase (DGK) paralogs have revealed conserved domains and spatial arrangements, enabling docking studies to investigate ATP-binding sites and membrane orientation [28]. Allosteric drugs identified through such approaches can potentially overcome resistance to conventional orthosteric inhibitors.

Target Prioritization: Machine learning approaches combining AlphaFold structures with protein features (subcellular localization, network properties, essentiality) can generate druggability scores for novel cancer targets [32]. These methods achieve high accuracy (AUC = 0.89) in predicting clinical trial drug targets, significantly accelerating target identification [32].

Integration with Drug Discovery Workflows

The workflow in Figure 2 illustrates how AlphaFold predictions integrate into comprehensive structure-based drug discovery pipelines for oncology targets.

Figure 2: Integration of AlphaFold predictions into cancer drug discovery workflow, from target identification to experimental validation.

Limitations and Considerations

Method-Specific Limitations

Despite their transformative impact, AlphaFold systems have important limitations that researchers must consider:

Confidence Assessment: While AF3 provides confidence metrics (pLDDT, PAE), these may not always correlate perfectly with accuracy, particularly for novel binding modes or unusual structural motifs [8]. Independent validation using complementary assessment tools like VoroIF-GNN or pDockQ is recommended for critical applications [8].

Structural Artifacts: Both AF2 and AF3 can occasionally produce confident but unrealistic structures, particularly for proteins with unusual sequence compositions such as perfect repeats, which may be folded into implausible β-solenoid structures with high confidence [33]. Such artifacts necessitate careful structural validation.

Dynamic Properties: Static structural predictions do not capture protein dynamics, conformational changes, or allosteric transitions that often mediate drug binding [28]. Integration with molecular dynamics simulations may be necessary to understand binding mechanisms.

Target Specific Performance: Performance varies across different protein classes and complex types. AF3 shows particularly strong performance for antibody-antigen interfaces and protein-ligand complexes, but researchers should verify performance for their specific target classes [2] [8].

AlphaFold3 represents a significant advancement in protein-ligand interaction prediction, offering substantially improved accuracy compared to both traditional docking methods and AlphaFold2. By providing detailed protocols, benchmarking data, and implementation guidelines, this application note enables researchers to leverage these tools effectively in cancer drug discovery. As the field continues to evolve, integration of AlphaFold predictions with experimental validation and complementary computational methods will further enhance their utility in identifying and optimizing novel cancer therapeutics.

Modeling Antibody-Antigen Complexes to Advance Immuno-Oncology

The precise prediction of antibody-antigen (Ab-Ag) complex structures is a cornerstone of modern immuno-oncology, enabling the rational design of novel therapeutics such as bispecific antibodies and antibody-drug conjugates. The advent of deep learning-based structure prediction tools, notably AlphaFold2 (AF2) and its successors, has initiated a paradigm shift in this field. These tools offer the potential to accelerate drug discovery by providing high-confidence structural models of immune complexes, thereby reducing reliance on time-consuming and resource-intensive experimental methods. This Application Note details the integration of AlphaFold series tools into a standardized computational workflow for predicting and analyzing antibody-antigen interactions, with a specific focus on applications in cancer research. We provide benchmark performance data, step-by-step protocols for complex structure prediction and affinity analysis, and a curated list of essential research tools to equip scientists with the methodologies needed to advance targeted immunotherapies.

State of the Field: Performance Benchmarking of Computational Tools

Accurate benchmarking is essential for selecting the appropriate computational tool for a given project. The performance of structure prediction tools can vary significantly based on the specific task, such as docking accuracy or side-chain modeling. The tables below summarize the key performance metrics for current state-of-the-art tools.

Table 1: Benchmarking of Antibody-Antigen Complex Prediction Tools

| Tool Name | Type | Reported Docking Success Rate (CAPRI Medium/High) | Key Strengths | Notable Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold3 (AF3) [3] | Generalist ML Complex Predictor | ~35% (Single seed, DockQ≥0.23) | State-of-the-art accuracy for Ab-Ag docking; models full complexes from sequence. | Server access is limited; performance can vary with seed sampling. |

| AlphaFold-Multimer (AF2) [34] [35] | Specialized ML for Protein Complexes | ~18-30% (Top-ranked model) | Strong performance; established, widely used protocol. | Less accurate for Ab-Ag complexes than AF3; struggles with flexible loops. |

| RoseTTAFold [34] | Generalist ML Complex Predictor | Lower than AlphaFold-Multimer [34] | Useful for general protein-protein interactions. | Lower accuracy for antibody-antigen specific docking. |

| RFdiffusion (Fine-tuned) [36] | De Novo Antibody Designer | N/A (Design, not prediction) | Capable of atomically accurate de novo design of antibody CDR loops and scFvs. | Requires experimental screening (e.g., yeast display) of designed candidates. |

| ClusPro (Ab-mode) + SnugDock [34] | Rigid-body Docking + Local Refinement | Intermediate between AF2 and RoseTTAFold [34] | Docking of pre-modeled antibody and antigen structures; allows for local flexibility. | Accuracy depends heavily on the quality of the input unbound structures. |

Table 2: Performance on Specific Structural Elements (Nanobodies and CDR H3)

| Tool / Model | Nanobody High-Accuracy Docking Success [3] | Median Unbound CDR H3 RMSD (Å) [3] | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold3 | 13.3% | 2.9 (Ab); 2.2 (Nb) | Antigen context improves CDR H3 prediction, especially for long loops (>15 residues). |

| Boltz-1 | 5.0% | 2.08 (Ab); 3.78 (Nb) | Improved CDR H3 accuracy on antibodies but poor performance on nanobodies. |

| Chai-1 | 3.3% | 2.71 (Ab); 3.63 (Nb) | Low high-accuracy docking success despite moderate CDR H3 accuracy. |