Real-Time PCR in Transcriptional Biomarker Discovery: A Foundational Guide from Discovery to Clinical Application

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the critical role real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) plays in the discovery and validation of transcriptional biomarkers for drug development and clinical diagnostics.

Real-Time PCR in Transcriptional Biomarker Discovery: A Foundational Guide from Discovery to Clinical Application

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the critical role real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) plays in the discovery and validation of transcriptional biomarkers for drug development and clinical diagnostics. It covers foundational principles, from the advantages of nucleic acids as biomarkers to the various RNA types (mRNA, miRNA, lncRNA) under investigation. The piece delves into detailed methodological protocols for assay design and data normalization, addresses key troubleshooting and optimization strategies as per MIQE guidelines, and explores validation frameworks, including comparisons with emerging high-throughput transcriptomic technologies. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this article serves as a practical guide for employing qPCR to develop robust, clinically actionable biomarker signatures.

The Transcriptional Biomarker Landscape: Why qPCR is a Gold Standard for Discovery

Transcriptional biomarkers, comprising both protein-coding mRNAs and non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs), are revolutionizing molecular diagnostics and therapeutic development. These biomarkers provide critical insights into cellular states, disease mechanisms, and treatment responses. The discovery and validation of these biomarkers increasingly rely on robust molecular techniques, with real-time PCR standing as a cornerstone technology due to its quantitative precision, sensitivity, and throughput. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical guide to defining transcriptional biomarkers, with emphasis on integrated analytical approaches and the pivotal role of real-time PCR in translating biomarker discovery into clinically actionable tools.

Transcriptional biomarkers are measurable RNA molecules whose expression patterns are indicative of specific biological states, pathological conditions, or responses to therapeutic intervention. The transcriptome encompasses not only messenger RNAs (mRNAs) that code for proteins but also a diverse array of non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) with crucial regulatory functions [1]. Once considered "junk," ncRNAs are now established as key players in cellular homeostasis, with microRNAs (miRNAs) and long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) being the most extensively studied families in pathological conditions such as cancer [2].

The stability of DNA methylation patterns in cell-free DNA (cfDNA) makes them particularly attractive as biomarkers for liquid biopsies, offering enhanced resistance to degradation compared to more labile RNA molecules [3]. As the field advances, the integration of multiple biomarker types—mRNA, miRNA, lncRNA, and DNA methylation marks—within coordinated regulatory networks is providing unprecedented insights into disease mechanisms and enabling more precise diagnostic and therapeutic applications.

Classes of Transcriptional Biomarkers

mRNA Biomarkers

mRNAs represent the classical transcriptional biomarkers, serving as intermediaries between genes and proteins. Their expression levels directly reflect the transcriptional activity of genes and can indicate disease states, cellular differentiation, or response to environmental stimuli. In cancer, mRNA expression profiles of key genes involved in oncogenic pathways (e.g., cell cycle regulation, apoptosis, metastasis) provide valuable diagnostic, prognostic, and predictive information [1].

Non-Coding RNA Biomarkers

Table 1: Major Classes of Non-Coding RNA Biomarkers

| RNA Class | Size | Primary Function | Role in Disease | Example Biomarkers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| microRNA (miRNA) | 18-24 nt | Post-transcriptional gene regulation via mRNA targeting | Oncogenic or tumor suppressor roles; deregulated in cancer, viral diseases, cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases [2] | miR-21 (suppresses tumor suppressors), miR-155 (oncogenic) |

| Long Non-Coding RNA (lncRNA) | >200 nt | Transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation; miRNA sponging | Influence tumour growth, invasion, and metastasis; drug sensitivity/resistance [2] | HOTAIR (promotes cancer development), MEG3 (tumor suppressor) |

| Circular RNA (circRNA) | Variable | miRNA sponging; protein decoys | Emerging roles in various cancers | Not specified in search results |

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are short RNA transcripts that typically regulate gene expression by binding to the 3'-untranslated region of target mRNAs, leading to translational repression or mRNA degradation [2]. A single miRNA can target multiple mRNAs, enabling coordinated regulation across entire pathways. miRNA expression is frequently tissue-specific and deregulated in numerous diseases, making them promising biomarker candidates.

Long Non-Coding RNAs (lncRNAs) exceed 200 nucleotides and exhibit diverse regulatory mechanisms, including chromatin modification, transcriptional interference, and sequestration of miRNAs (acting as "miRNA sponges") [2]. They show remarkable cell- and tissue-specific expression patterns and are specifically deregulated under pathological conditions, offering high specificity as biomarkers.

Real-Time PCR: The Gold Standard in Biomarker Analysis

Fundamental Principles and Workflow

Real-time PCR, also known as quantitative PCR (qPCR), has revolutionized transcriptional biomarker analysis by enabling accurate quantification of nucleic acids during the amplification process. Unlike traditional PCR that relies on end-point detection, real-time PCR monitors PCR product accumulation in real-time using fluorescent reporter molecules [1]. This approach provides both quantification and amplification capabilities within a single, closed-tube system, significantly reducing contamination risk while increasing throughput.

The critical distinction between qPCR (quantification of DNA targets) and RT-qPCR (quantification of RNA targets after reverse transcription to cDNA) is essential for proper experimental design [1]. RT-qPCR represents one of the most sensitive gene analysis techniques available, capable of detecting down to a single copy of a transcript, making it indispensable for studying low-abundance biomarkers in complex biological samples [1].

Experimental Design and Workflow

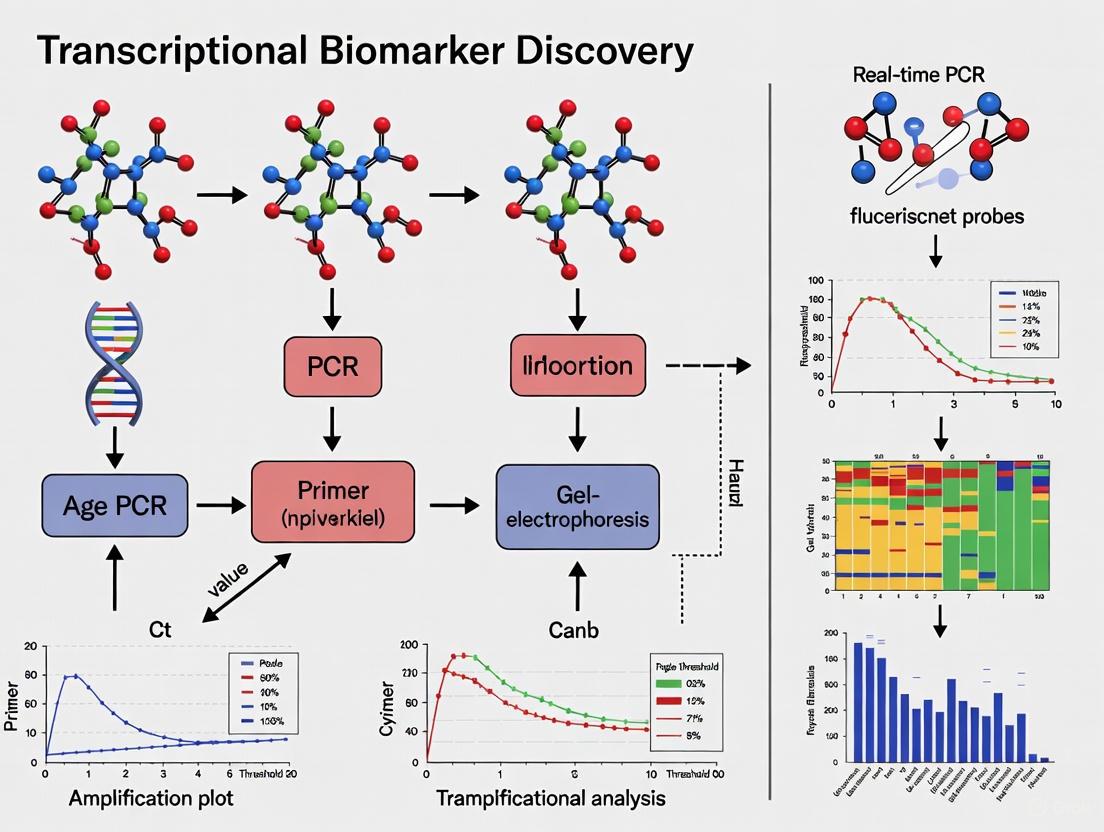

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive RT-qPCR workflow for transcriptional biomarker analysis:

Key Considerations for Robust qPCR Assays

Assay Specificity and Efficiency: qPCR assays must demonstrate high specificity for intended targets with amplification efficiencies between 90-110% for reliable quantification [1]. Proper assay design requires checking against known sequence databases (NCBI, Ensembl) to ensure target specificity, particularly for discriminating between closely related gene family members or splice variants.

Normalization Strategies: Accurate gene expression quantification requires appropriate normalization using validated reference genes (endogenous controls) to correct for technical variations in RNA input, reverse transcription efficiency, and sample quality [1]. The selection of stable reference genes must be empirically determined for specific experimental conditions as their expression can vary across tissue types and treatments.

MIQE Guidelines: The Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments (MIQE) guidelines provide a comprehensive framework for ensuring qPCR assay quality, transparency, and reproducibility [4]. Recent updates to MIQE 2.0 emphasize the need for rigorous methodological practices, including proper documentation of sample handling, assay validation, efficiency calculations, and normalization strategies. Adherence to these guidelines is critical for generating reliable transcriptional biomarker data, particularly in molecular diagnostics where results inform clinical decisions [4].

Advanced Biomarker Discovery and Validation

Integrated Transcriptomic Analysis

Advanced biomarker discovery increasingly focuses on regulatory networks rather than individual molecules. Integrated analyses of mRNA-lncRNA-miRNA interactions reveal complex regulatory circuits that drive disease processes. For example, in hepatocellular carcinoma, a comprehensive mRNA-lncRNA-miRNA (MLMI) network identified 16 miRNAs, 3 lncRNAs, and 253 mRNAs with reciprocal interactions that synergistically modulate carcinogenesis [5]. Such networks provide a more complete understanding of molecular mechanisms and identify coordinated biomarker signatures with enhanced diagnostic and prognostic value.

The following diagram illustrates the complex interactions within an integrated mRNA-lncRNA-miRNA network:

Biomarker Categorization in Meta-Analysis

With the accumulation of transcriptomic datasets, meta-analysis approaches have become essential for identifying robust biomarkers across multiple studies. Biomarker categorization by differential expression patterns across studies helps explain between-study heterogeneity and classifies biomarkers into functional categories [6]. Advanced statistical methods, such as the adaptively weighted Fisher's method, now enable biomarker categorization that simultaneously considers concordant patterns, biological significance (effect size), and statistical significance (p-values) across studies [6].

This approach is particularly valuable in pan-cancer analyses, where biomarkers can be categorized as: (1) universally dysregulated across all cancer types, (2) specific to particular cancer lineages, or (3) exhibiting context-dependent regulation. Such categorization facilitates more focused downstream analyses, including pathway enrichment and regulatory network construction specific to each biomarker category [6].

Analytical Validation Frameworks

Robust biomarker validation requires rigorous analytical frameworks. For real-time PCR assays, both laboratory-developed tests (LDTs) and commercial assays must undergo comprehensive verification to establish analytical specificity, sensitivity, precision, and reproducibility [7]. Key validation parameters include:

- Limit of Detection (LOD): The lowest concentration of the biomarker that can be reliably detected

- Dynamic Range: The quantitative range over which the assay provides accurate measurements

- Precision: Reproducibility of measurements across replicates, operators, and days

- Specificity: Ability to distinguish target from related biomarkers

The validation process must also consider sample-specific factors, including the presence of inhibitors, RNA integrity, and reverse transcription efficiency [7]. For clinical applications, analytical validation should follow established guidelines such as CLIA requirements in the United States or IVD Regulations in Europe [7].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Transcriptional Biomarker Analysis

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| NGS Panels | Comprehensive biomarker discovery via transcriptome sequencing | Enables identification of mRNA, miRNA, lncRNA in parallel; Foundation Medicine offers RNA testing for >1,500 genes [8] |

| qPCR Assays | Targeted biomarker quantification and validation | Pre-designed assays available for pathways or specific gene sets; TaqMan and SYBR Green chemistries [1] |

| Reverse Transcription Kits | cDNA synthesis from RNA templates | Choice of oligo dT (mRNA-specific) or random primers (total RNA/broader representation) [1] |

| Reference Genes | Normalization of qPCR data | Essential for accurate quantification; must be validated for specific tissue/experimental conditions [1] |

| PCR Arrays | Multi-gene expression profiling | Pre-configured 96- or 384-well plates with assays for specific pathways or disease states [1] |

| Standard Curves | Absolute quantification | Serial dilutions of standards with known concentration for calibration [1] |

| Internal Controls | Monitoring reaction efficiency | Included in each reaction to detect inhibitors or reaction failure [7] |

Applications in Drug Development and Clinical Translation

Transcriptional biomarkers play increasingly critical roles throughout the drug development pipeline. In cellular therapies, potency testing represents one of the most challenging analytical requirements, where gene expression profiling of both coding and non-coding RNAs can serve as important tools for quantifying biological activity [9]. The complexity of cellular therapies, combined with limited product quantity and short release timelines, makes transcriptional biomarkers particularly attractive for lot-release testing and quality control [9].

In pharmacogenomics, transcriptional biomarkers inform drug selection and dosing strategies. The FDA's Table of Pharmacogenomic Biomarkers in Drug Labeling includes numerous examples where gene expression patterns guide therapeutic decisions [10]. For instance, hormone receptor (ESR) status determines eligibility for multiple targeted therapies in breast cancer, while PD-L1 expression levels inform immunotherapy selection across multiple cancer types [10].

The transition of transcriptional biomarkers into clinical practice requires demonstration of clinical utility through large-scale validation studies. Liquid biopsy approaches, particularly those leveraging DNA methylation biomarkers in plasma, urine, or other biofluids, offer minimally invasive options for cancer detection and monitoring [3]. While few DNA methylation-based tests have achieved routine clinical implementation to date, promising examples such as Epi proColon for colorectal cancer detection demonstrate the potential of epigenetic transcriptional markers in diagnostic applications [3].

The field of transcriptional biomarkers has evolved dramatically from single mRNA quantification to integrated analyses of complex regulatory networks encompassing multiple RNA species. Real-time PCR remains foundational to biomarker discovery and validation, offering unparalleled sensitivity, quantitative accuracy, and practical utility across research and clinical applications. As biomarker approaches increasingly incorporate multi-omic data and complex analytical frameworks, the fundamental principles of robust assay design, rigorous validation, and analytical transparency remain essential for generating reliable, clinically actionable results. The continued advancement of transcriptional biomarkers promises to enhance personalized medicine through improved disease detection, monitoring, and therapeutic selection.

Abstract This whitepaper delineates the pivotal advantages of nucleic acid biomarkers—specifically, their superior sensitivity, specificity, and cost-efficiency—within the framework of modern drug development. The discourse is centered on the indispensable role of real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) in the discovery and validation of transcriptional biomarkers, providing a technical guide for researchers and scientists. We present quantitative data, detailed protocols, and essential toolkits to facilitate the integration of these biomarkers into preclinical and clinical research pipelines.

1. Introduction: The Centrality of Real-Time PCR in Biomarker Discovery Transcriptional biomarkers, comprising mRNA and non-coding RNA species, offer a dynamic snapshot of cellular state and physiological responses. Their utility in diagnosing disease, predicting therapeutic response, and monitoring treatment efficacy is paramount. Real-time PCR serves as the cornerstone technology for this field, enabling the sensitive, specific, and quantitative detection of transcript levels. The subsequent sections will dissect how the intrinsic properties of nucleic acid biomarkers, as measured by qPCR and its advanced derivatives, confer significant advantages in biomarker-driven research.

2. Quantitative Advantages of Nucleic Acid Biomarkers The following table summarizes key performance metrics of nucleic acid biomarkers, particularly when assessed via qPCR and digital PCR (dPCR), compared to traditional protein-based biomarkers.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Biomarker Performance Characteristics

| Characteristic | Nucleic Acid Biomarkers (qPCR/dPCR) | Traditional Protein Biomarkers (ELISA) |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Detects down to a few copies of RNA/DNA per reaction. LOD can be <1 fg for specific transcripts. | Typically in the picogram (pg) to nanogram (ng) per milliliter range. |

| Specificity | Extremely high; ensured by primer/probe design targeting unique genomic sequences. | Can be compromised by cross-reactivity with structurally similar proteins or isoforms. |

| Dynamic Range | 7-8 orders of magnitude for qPCR; >4 orders for dPCR. | Typically 3-4 orders of magnitude. |

| Sample Throughput | Very high (96-, 384-, 1536-well formats). | Moderate to high (96-well format standard). |

| Sample Input | Low (nanograms of total RNA required). | Higher (microliters of serum/plasma often required). |

| Multiplexing Capacity | Moderate (up to 4-6 targets per well with probe-based multiplex qPCR). | Low to moderate (2-3 targets per well in validated panels). |

| Time to Result | Fast (from sample to data in 3-4 hours). | Slower (often 5-8 hours including long incubation steps). |

| Cost per Sample | Low for single-plex, increases with multiplexing. Reagent costs are generally lower. | Higher, driven by costly capture and detection antibodies. |

3. Detailed Experimental Protocol: qPCR Workflow for Transcriptional Biomarker Validation This protocol outlines the steps from sample collection to data analysis for validating a candidate mRNA biomarker.

3.1. Sample Lysis and Nucleic Acid Extraction

- Principle: Homogenize tissue or lyse cells to release total RNA while preserving RNA integrity.

- Procedure:

- Homogenize 10-30 mg of tissue or pellet from 1x10^6 cells in 1 ml of TRIzol reagent.

- Incubate for 5 minutes at room temperature.

- Add 0.2 ml of chloroform, vortex vigorously for 15 seconds, and incubate for 3 minutes.

- Centrifuge at 12,000 x g for 15 minutes at 4°C.

- Transfer the aqueous upper phase to a new tube.

- Precipitate RNA by adding 0.5 ml of isopropyl alcohol. Incubate for 10 minutes at room temperature.

- Centrifuge at 12,000 x g for 10 minutes at 4°C to form an RNA pellet.

- Wash the pellet with 1 ml of 75% ethanol.

- Air-dry the pellet and resuspend in 20-50 µl of RNase-free water.

- Quantify RNA concentration using a spectrophotometer (e.g., NanoDrop).

3.2. Reverse Transcription (cDNA Synthesis)

- Principle: Convert RNA into complementary DNA (cDNA) using reverse transcriptase.

- Procedure (using a 20 µl reaction):

- Combine 1 µg of total RNA, 1 µl of Oligo(dT)18 primer (500 µg/ml), and 1 µl of 10 mM dNTP mix. Add nuclease-free water to 13 µl.

- Heat the mixture to 65°C for 5 minutes, then quickly chill on ice.

- Add 4 µl of 5X Reverse Transcription Buffer, 1 µl of RNase Inhibitor (20 U/µl), and 1 µl of Reverse Transcriptase (200 U/µl).

- Incubate in a thermal cycler: 42°C for 60 minutes, followed by 70°C for 5 minutes to inactivate the enzyme.

- Dilute the cDNA 1:5 or 1:10 with nuclease-free water before qPCR.

3.3. Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qPCR)

- Principle: Amplify and quantify a specific cDNA target in real-time using a sequence-specific TaqMan probe.

- Procedure (using a 20 µl reaction in a 384-well plate):

- Prepare a master mix for each target: 10 µl of 2X TaqMan Master Mix, 1 µl of 20X TaqMan Gene Expression Assay (primers and probe), 4 µl of nuclease-free water.

- Aliquot 15 µl of master mix into each well.

- Add 5 µl of diluted cDNA template per well.

- Seal the plate and centrifuge briefly.

- Run on a real-time PCR instrument using the following cycling conditions:

- Hold Stage: 50°C for 2 minutes (UDG incubation), 95°C for 10 minutes.

- PCR Stage (40 cycles): 95°C for 15 seconds (denaturation), 60°C for 1 minute (annealing/extension).

- Data Analysis: Calculate the Cycle Threshold (Cq) values. Use the comparative ΔΔCq method to determine relative gene expression, normalizing to a validated endogenous control (e.g., GAPDH, ACTB) and relative to a calibrator sample (e.g., untreated control).

4. Visualizing the Workflow and Technology Comparison

Diagram Title: qPCR Biomarker Workflow

Diagram Title: Detection Tech Comparison

5. The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents The following table lists critical reagents and their functions for a successful qPCR-based biomarker study.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for qPCR Biomarker Analysis

| Reagent / Material | Function | Critical Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Stabilization Reagent (e.g., RNAlater, TRIzol) | Preserves RNA integrity immediately upon sample collection by inactivating RNases. | Essential for preventing pre-analytical RNA degradation, which directly impacts data accuracy. |

| DNase I, RNase-free | Degrades genomic DNA contamination during RNA purification to prevent false-positive amplification in qPCR. | A critical step for accurate mRNA quantification. |

| High-Capacity Reverse Transcription Kit | Synthesizes stable cDNA from total RNA templates. | Should include RNase inhibitor and use random hexamers or oligo-dT primers for comprehensive conversion. |

| TaqMan Gene Expression Assays | Pre-optimized, sequence-specific primers and FAM-labeled probes for target amplification. | Provides high specificity and reproducibility; requires prior knowledge of the target sequence. |

| TaqMan Universal Master Mix | Contains HotStart Taq DNA Polymerase, dNTPs, and optimized buffer for robust probe-based qPCR. | Includes UNG to prevent carryover contamination; ensures efficient and specific amplification. |

| Validated Endogenous Control Assays | Targets housekeeping genes (e.g., GAPDH, 18S rRNA) for normalization of Cq values. | Must be empirically validated to ensure stable expression across all experimental conditions. |

| Nuclease-Free Water | Serves as a solvent and negative control. | Guarantees the absence of nucleases that could degrade reagents or templates. |

The Central Role of qPCR in Translating NGS Discoveries to Clinical Assays

The journey from genomic discovery to routine clinical assay represents a critical pathway in modern precision medicine. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized genomic discovery by providing unprecedented capacity to identify novel genetic biomarkers across the entire transcriptome without prior knowledge of target sequences [11] [12]. However, the transition of these discoveries into robust, clinically implementable assays presents significant challenges related to validation, reproducibility, and cost-effectiveness that NGS alone cannot optimally address [13] [14]. Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) fulfills this essential role as the bridge between discovery and application, providing the methodological rigor necessary to validate NGS findings and transform them into reliable clinical tools [15] [16]. This technical guide examines the central role of qPCR in the translational pipeline, detailing the experimental protocols, performance characteristics, and practical implementations that make it indispensable for bringing NGS discoveries to patient care.

The complementary relationship between these technologies stems from their fundamental strengths: NGS offers unparalleled discovery power, while qPCR delivers precision, sensitivity, and practical efficiency for targeted analysis [17] [12]. This synergy enables researchers to leverage the comprehensive screening capabilities of NGS while relying on the proven reliability of qPCR for validation and routine monitoring [13] [16]. As the demand for personalized medicine grows, with the market projected to reach nearly $590 billion by 2028, the efficient translation of genomic discoveries into clinically actionable assays becomes increasingly critical [16]. This guide provides researchers and drug development professionals with the technical framework for effectively integrating qPCR into their translational workflows, ensuring that NGS discoveries can be rapidly, reliably, and economically implemented to improve patient outcomes.

Technological Synergy: How qPCR and NGS Complement Each Other

Fundamental Technological Differences

The functional synergy between NGS and qPCR emerges from their complementary operational characteristics and performance metrics. NGS operates as a hypothesis-free discovery engine, capable of sequencing millions of DNA fragments simultaneously to provide a comprehensive view of genetic variations, gene expression profiles, and epigenetic modifications without requiring prior knowledge of target sequences [11] [12]. This unbiased approach enables identification of novel transcripts, alternatively spliced isoforms, and non-coding RNA species that might be missed by targeted methods [17] [12]. In contrast, qPCR functions as a precision validation tool, employing sequence-specific probes or primers to quantitatively detect predefined targets with exceptional sensitivity, reproducibility, and quantitative accuracy [15] [18]. This fundamental difference in scope—broad discovery versus targeted quantification—creates a natural partnership in the translational pipeline.

The key distinction lies in what each technology detects. While qPCR reliably detects only known sequences for which probes have been designed, NGS can identify both known and novel variants in a single assay [16] [12]. This gives NGS significantly higher discovery power, defined as the ability to identify novel genetic elements [12]. However, for validation and routine application where targets are already defined, qPCR offers superior practical efficiency, with familiar workflows, accessible equipment available in most laboratories, and significantly lower per-sample costs for limited target numbers [17] [12]. The technologies also differ in mutation resolution, with NGS capable of detecting variants ranging from single nucleotide changes to large chromosomal rearrangements, while qPCR is generally limited to detecting specific predefined mutations [12].

Performance Characteristics and Applications

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of NGS and qPCR Technical Characteristics

| Parameter | Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) | Quantitative PCR (qPCR) |

|---|---|---|

| Discovery Power | High (detects known and novel variants) [12] | Limited to known sequences [16] |

| Throughput | High (1000+ targets simultaneously) [12] | Moderate (optimal for ≤20 targets) [17] [12] |

| Sensitivity | High (detects variants at 1% frequency) [12] | Very High (detects rare transcripts) [15] [19] |

| Quantitative Capability | Absolute quantification via read counts [12] | Relative or absolute quantification via Ct values [15] |

| Turnaround Time | Days to weeks (including data analysis) [17] | Hours (rapid results) [17] [16] |

| Cost per Sample | Higher for comprehensive analysis [17] [16] | Lower for limited target numbers [16] [12] |

| Best Applications | Novel biomarker discovery, comprehensive profiling [11] [17] | Targeted validation, routine monitoring, clinical implementation [13] [16] |

The performance characteristics outlined in Table 1 demonstrate how these technologies naturally complement each other in translational research. NGS provides the comprehensive breadth needed for initial discovery, while qPCR delivers the precision and efficiency required for validation and clinical implementation [17] [16]. For example, in cancer genomics, NGS can identify a complex array of mutations across thousands of genes, but qPCR provides the rapid, cost-effective means to monitor specific actionable mutations in clinical settings [20] [16]. This division of labor creates an efficient translational pipeline where each technology performs the tasks best suited to its capabilities.

The difference in throughput characteristics is particularly important for practical implementation. While NGS can profile hundreds to thousands of targets across multiple samples in a single run, this comes with substantial data analysis burdens and longer turnaround times [17]. qPCR, while handling fewer targets per reaction, provides results in hours rather than days, making it more responsive for clinical decision-making [16]. This speed advantage, combined with significantly lower equipment costs and greater accessibility in clinical laboratories, positions qPCR as the optimal technology for routine monitoring of established biomarkers [17] [12].

The Validation Pipeline: Methodological Framework

Experimental Workflow for NGS Discovery Followed by qPCR Validation

The standard validation pipeline begins with NGS-based discovery and progresses through systematic qPCR confirmation. This workflow ensures that initial findings from NGS experiments are rigorously verified before implementation in clinical settings. The process can be visualized as a sequential pathway with distinct phases:

NGS Discovery Phase: The process initiates with comprehensive profiling using NGS technology. For transcriptomic studies, this typically involves RNA-Seq to capture both known and novel transcripts, or targeted transcriptome sequencing focused on protein-coding genes [17]. The critical requirement at this stage is generating high-quality sequencing data with sufficient depth to detect even low-abundance transcripts. Studies have shown that sequencing depth of at least 20-30 million reads per sample is often necessary for robust transcript quantification [11]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, researchers used the ARTIC sequencing method for SARS-CoV-2 genomic characterization, though this approach demonstrated limitations with high PCR cycle threshold (Ct) values and primer-variant mismatches in heavily mutated lineages [13].

Bioinformatic Analysis: Following sequencing, specialized bioinformatics pipelines process the raw data to identify differentially expressed genes, splice variants, or other transcriptional biomarkers of interest [11] [20]. For cancer applications, this includes identification of single-nucleotide variants (SNVs), small insertions and deletions (indels), copy number alterations (CNAs), and structural variants (SVs) using tools like Mutect2 (for SNVs/indels), CNVkit (for CNAs), and LUMPY (for gene fusions) [20]. Variants are typically classified according to established guidelines such as the Association for Molecular Pathology (AMP) tiers, with Tier I representing variants of strong clinical significance and Tier II representing variants of potential clinical significance [20].

Candidate Selection: Bioinformatic analysis typically generates a substantial list of candidate biomarkers that must be prioritized for validation. Selection criteria generally include statistical significance of expression differences, magnitude of fold-change, biological plausibility, and potential clinical utility [15]. This prioritization step is crucial as it determines which candidates will advance to the more resource-intensive validation phase.

qPCR Assay Design: For each selected candidate, specific qPCR assays are designed according to MIQE (Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments) guidelines to ensure reproducibility and reliability [15]. TaqMan assays represent the gold standard approach, utilizing sequence-specific probes and primers that ideally span exon-exon junctions to avoid genomic DNA amplification [17] [18]. For variant-specific detection, assays must be carefully designed to distinguish between closely related sequences, such as different transcript isoforms or mutant versus wild-type alleles [17].

Experimental Validation: The core qPCR validation process involves testing the candidate biomarkers on independent sample sets that were not used in the initial discovery phase. This critical step confirms that the NGS findings are reproducible across different patient cohorts and experimental conditions [15] [17]. The quantitative nature of qPCR allows for precise measurement of expression levels, enabling researchers to establish clinical thresholds and define positive/negative cutoffs for diagnostic implementation [18].

Clinical Implementation: Successfully validated assays transition to clinical application, where they are used for diagnostic, prognostic, or predictive testing. At this stage, considerations shift to clinical reproducibility, turnaround time, cost-effectiveness, and regulatory compliance [14] [16]. qPCR excels in this environment due to its rapid processing time (typically hours rather than days), lower cost per sample for limited target numbers, and established regulatory pathways for clinical laboratory implementation [16] [12].

Case Study: SARS-CoV-2 Variant Surveillance

A compelling example of this synergistic approach comes from SARS-CoV-2 variant surveillance during the COVID-19 pandemic [13]. Researchers implemented a two-pronged strategy combining NGS for comprehensive genomic characterization with qPCR for rapid variant tracking. This approach leveraged the TaqPath COVID-19 Combo Kit to monitor S-gene target failure (SGTF), which is associated with specific spike protein deletions (H69-V70) present in Alpha and certain Omicron lineages [13].

The methodology included:

- Periodic NGS: Using the ARTIC sequencing method for definitive variant identification and phylogenetic analysis [13]

- Targeted RT-qPCR assays: Designed to detect lineage-specific deletions including NTD156-7 (for Delta variant tracking) and NTD25-7 (for Omicron BA.2, BA.4, and BA.5 lineage tracking) [13]

- In silico validation: Ensuring primer and probe binding sites showed low variability in publicly available SARS-CoV-2 genome databases [13]

- In vitro correlation: Demonstrating excellent agreement between qPCR results and NGS-confirmed variants [13]

This combined approach enabled near-real-time monitoring of circulating variants while providing ongoing validation of qPCR screening through periodic sequencing. The efficiency of qPCR allowed for widespread variant surveillance, while NGS provided definitive characterization of novel variants and validation of the qPCR assays [13]. This model demonstrates how qPCR can transform NGS discoveries into practical surveillance tools for public health applications.

Practical Implementation: Experimental Protocols and Reagents

Detailed Validation Protocol for Transcriptional Biomarkers

The transition from NGS-derived candidate biomarkers to clinically applicable qPCR assays requires meticulous experimental validation. The following protocol outlines a robust framework for this critical translational step:

Step 1: RNA Extraction and Quality Control

- Extract total RNA using silica-membrane based methods (e.g., QIAamp kits) suitable for the sample type (FFPE tissues, liquid biopsies, fresh frozen tissue) [20].

- Assess RNA quality and quantity using appropriate methods. For FFPE samples, implement additional quality control measures due to potential RNA fragmentation [20].

- Critical Step: Determine RNA integrity numbers (RIN) or similar quality metrics. Only proceed with samples meeting predetermined quality thresholds (typically RIN >7 for fresh samples, with adjusted thresholds for FFPE specimens) [15].

Step 2: Reverse Transcription

- Convert 100-1000 ng of total RNA to cDNA using reverse transcriptase with random hexamers and/or oligo-dT primers [15].

- Include controls without reverse transcriptase (-RT controls) to assess genomic DNA contamination.

- Use uniform reaction conditions across all samples to minimize technical variability [15].

Step 3: qPCR Assay Selection and Design

- Select appropriate assays based on the candidate biomarkers identified through NGS.

- For known transcripts: Use commercially available TaqMan Gene Expression Assays that span exon-exon junctions [17] [18].

- For novel variants or specific isoforms: Design custom assays using tools like the TaqMan Custom Assay Design Tool [17].

- Critical Step: Validate assay specificity and efficiency through dilution series, ensuring amplification efficiency between 90-110% with R² >0.98 [15].

Step 4: Experimental Setup and Run Conditions

- Perform reactions in technical and biological replicates (minimum 3 each) to account for variability [15].

- Utilize appropriate qPCR instrumentation capable of detecting the specific fluorescence chemistry (e.g., QuantStudio 12K Flex system for high-throughput applications) [18].

- Standardize reaction volumes and master mix compositions across all samples. Commercial master mixes (e.g., Thermo Fisher's TaqMan Universal Master Mix) provide consistent performance [18].

Step 5: Data Analysis and Normalization

- Calculate cycle threshold (Ct) values using the instrument's software with consistent threshold settings.

- Normalize data using carefully selected reference genes that show stable expression across the sample set [15].

- Critical Step: Validate reference gene stability using algorithms like geNorm or NormFinder [15].

- Express results as ΔCt (relative to reference genes) or ΔΔCt (relative to control group) for fold-change calculations [15].

Step 6: Establishment of Clinical Thresholds

- Analyze receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves to determine optimal cut-off values that maximize clinical sensitivity and specificity [20].

- Establish positive/negative thresholds based on validation cohort results.

- Define gray zones where applicable and establish protocols for retesting or alternative testing in these cases.

This protocol emphasizes the critical quality control checkpoints that ensure the reliability of the validated assays. Adherence to MIQE guidelines throughout the process is essential for generating clinically actionable data [15].

Research Reagent Solutions for qPCR Validation

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Platforms for qPCR Validation Workflows

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| qPCR Master Mixes | TaqMan Universal Master Mix, dUTP master mixes [16] | Enzymatic components for amplification | Contains polymerase, dNTPs, optimized buffer; dUTP formats prevent amplicon contamination |

| Assay Formats | Individual tubes, 96/384-well pre-loaded plates, TaqMan Array Cards, OpenArray Plates [18] | Flexible formats for different throughput needs | Pre-plated assays increase reproducibility; Array cards enable high-throughput profiling |

| Reverse Transcription Kits | High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit [17] | Convert RNA to cDNA for gene expression analysis | High efficiency conversion with minimal bias |

| RNA Extraction Kits | QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit [20] | Nucleic acid purification from various sample types | Optimized for challenging samples including FFPE tissues |

| Quality Control Assays | Qubit dsDNA HS Assay, NanoDrop Spectrophotometer [20] | Assess nucleic acid quantity and quality | Accurate quantification and purity assessment |

| Instrument Platforms | QuantStudio 12K Flex System [18] | Detection and quantification of qPCR reactions | Scalable from single tubes to 384-well plates and arrays |

The selection of appropriate reagents and platforms significantly impacts the success and reproducibility of qPCR validation studies. Commercial master mixes optimized for specific applications (e.g., lyo-ready formulations for ambient-temperature stability or glycerol-free enzymes for enhanced performance) can improve assay robustness [16]. Similarly, matching the assay format to the experimental needs—from individual tubes for maximum flexibility to OpenArray plates for the highest throughput—ensures efficient resource utilization while maintaining data quality [18].

Performance Metrics and Clinical Utility

Analytical Performance Comparison

The translation of NGS discoveries to clinical assays requires careful consideration of the performance characteristics of both technologies. Understanding these metrics is essential for designing an effective translational workflow:

Table 3: Analytical Performance Metrics for NGS and qPCR

| Performance Metric | NGS Performance | qPCR Performance | Clinical Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | High (detects variants at 1% frequency) [12] | Very High (detects single copies) [19] | qPCR better for minimal residual disease detection |

| Specificity | High (with appropriate bioinformatics) [14] | Very High (sequence-specific probes) [18] | Both suitable for clinical application |

| Reproducibility | Moderate (library prep introduces variability) [14] | High (coefficient of variation typically <5%) [15] | qPCR more reliable for serial monitoring |

| Dynamic Range | >5 logs [12] | 7-8 logs [15] | qPCR better for quantifying large expression differences |

| Multiplexing Capacity | Very High (1000+ targets) [12] | Moderate (typically 4-6 targets per reaction) [18] | NGS more efficient for comprehensive profiling |

| Turnaround Time | 2-7 days (including analysis) [17] | 2-4 hours [16] | qPCR preferable when rapid results needed |

The data in Table 3 highlight why qPCR remains the gold standard for analytical validation despite the discovery advantages of NGS. The exceptional reproducibility of qPCR, with coefficients of variation typically below 5%, makes it ideally suited for clinical applications where consistent performance across time and laboratories is essential [15]. Similarly, the extensive dynamic range of 7-8 logs enables accurate quantification of biomarkers that may be expressed at vastly different levels in clinical samples [15].

The difference in turnaround time has significant implications for clinical implementation. While NGS requires days to weeks from sample preparation to final report (particularly when outsourced to core facilities), qPCR can generate results in hours [17] [16]. This rapid processing time makes qPCR more suitable for clinical scenarios where timely results directly impact patient management decisions, such as selection of targeted therapies or infectious disease diagnosis [16].

Clinical Implementation and Economic Considerations

The successful implementation of genomically-matched therapies in real-world clinical practice demonstrates the practical utility of the NGS-to-qPCR pipeline. A 2025 study of 990 patients with advanced solid tumors who underwent NGS testing found that 26.0% harbored Tier I variants (strong clinical significance) and 86.8% carried Tier II variants (potential clinical significance) [20]. Among patients with Tier I variants, 13.7% received NGS-based therapy, with response rates of 37.5% (partial response) and 34.4% (stable disease) among those with measurable lesions [20]. This study illustrates how NGS identifies actionable biomarkers, but also highlights the need for more efficient methods to routinely monitor these biomarkers during treatment.

Economic considerations strongly favor qPCR for routine clinical monitoring once biomarkers have been identified. While NGS provides comprehensive profiling, its cost-effectiveness diminishes when tracking a limited number of known biomarkers [16] [12]. The infrastructure requirements also differ significantly: NGS demands substantial bioinformatics resources, specialized personnel, and computational infrastructure, while qPCR can be implemented in most clinical laboratories with minimal additional resources [20] [16]. This accessibility advantage makes qPCR particularly valuable for resource-limited settings or point-of-care applications.

The combination of both technologies in a hybrid approach maximizes economic efficiency. In this model, NGS serves as the comprehensive discovery tool, while qPCR provides the cost-effective monitoring solution for established biomarkers [16]. This approach was successfully implemented during the COVID-19 pandemic, where NGS provided genomic surveillance of emerging variants while qPCR enabled widespread testing and tracking of specific variants of concern [13] [16]. Similarly, in oncology, NGS can identify the complex mutation profile of a tumor, while qPCR enables monitoring of minimal residual disease or emergence of specific resistance mutations during treatment [16].

The integration of NGS and qPCR represents a powerful paradigm for translating genomic discoveries into clinically actionable assays. NGS provides the unparalleled discovery power needed to identify novel biomarkers across the entire transcriptome, while qPCR delivers the precision, reproducibility, and practical efficiency required for clinical implementation [17] [16]. This synergistic relationship enables researchers to leverage the strengths of both technologies, creating an efficient pipeline from initial discovery to routine clinical application.

The future of molecular diagnostics will increasingly embrace hybrid approaches that strategically deploy each technology at the appropriate point in the clinical workflow [16]. Emerging technologies such as digital PCR chips and microfluidic PCR platforms will further enhance the role of qPCR in clinical translation by enabling absolute quantification of rare biomarkers and single-cell analysis [19]. These advancements, coupled with the growing availability of lyophilized, ambient-temperature stable reagents, will expand the application of qPCR to point-of-care settings and resource-limited environments [16].

For researchers and drug development professionals implementing this pipeline, several best practices emerge:

- Utilize qPCR both upstream and downstream of NGS—for quality control of input samples and validation of results [17]

- Adhere to MIQE guidelines throughout qPCR assay development and validation to ensure reproducibility and reliability [15]

- Establish clear criteria for transitioning from comprehensive NGS profiling to targeted qPCR monitoring based on clinical utility and economic considerations [16]

- Leverage standardized assay formats such as TaqMan Array Cards or OpenArray Plates to maintain consistency across validation studies and clinical implementation [18]

As personalized medicine continues to evolve, the complementary relationship between NGS and qPCR will remain fundamental to the translation of genomic discoveries into improved patient care. By understanding the respective strengths and optimal applications of each technology, researchers can effectively bridge the gap between discovery and clinical implementation, ultimately accelerating the delivery of precision medicine to patients who stand to benefit.

The transcriptome represents a dynamic and rich source of molecular information for biomarker discovery, extending far beyond the protein-coding genes that comprise just 1-2% of the human genome [15]. The remaining majority of the genome is pervasively transcribed into non-coding RNAs, once dismissed as "junk DNA" but now recognized as crucial regulatory molecules [21] [22]. Among these, messenger RNA (mRNA), microRNA (miRNA), and long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) have emerged as particularly valuable transcriptional biomarkers in molecular diagnostics and therapeutic development. These RNA species offer distinct advantages for clinical applications, including the ability to detect pathological changes minutes after a cellular signal, significantly earlier than corresponding protein-level alterations [15]. Furthermore, transcriptional biomarkers can be detected with exceptional sensitivity through amplification methods like reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR), enabling their measurement in minimal sample volumes, including liquid biopsies [15]. This technical guide explores the characteristics, functions, and research methodologies for these three RNA classes within the context of transcriptional biomarker discovery, with particular emphasis on the role of real-time PCR in validation workflows essential for translating biomarker signatures into clinically applicable tools.

RNA Types: Characteristics and Biological Functions

The following table summarizes the defining characteristics, biological functions, and biomarker potential of mRNA, miRNA, and lncRNA.

Table 1: Comparative overview of key RNA types in transcriptional biomarker research

| Characteristic | Messenger RNA (mRNA) | MicroRNA (miRNA) | Long Non-Coding RNA (lncRNA) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Definition | Protein-coding RNA transcript | Short non-coding RNA (~22 nt) | Long non-coding RNA (>200 nt) [15] |

| Primary Function | Template for protein synthesis | Post-transcriptional gene regulation | Diverse regulatory roles (transcriptional, epigenetic, structural) [21] [22] |

| Sequence Conservation | Generally high | High | Generally low to moderate [21] |

| Expression Level | Variable, from low to high | Variable | Typically low and tissue-specific [21] [15] |

| Stability in Circulation | Lower | High (protected in vesicles/protein complexes) [15] | Variable |

| Key Regulatory Mechanisms | Transcription, degradation | Transcription, processing, target mRNA interaction | Transcription, chromatin modification, molecular scaffolding [21] |

| Biomarker Applications | Disease signatures, treatment response [23] | Diagnostic and prognostic markers in cancer [15] [24] | Diagnostic, prognostic markers (e.g., H19, HOTAIR) [15] [24] |

Messenger RNA (mRNA)

As the intermediary between DNA and protein, mRNA has been the traditional focus of gene expression analysis. Its expression frequently correlates with pathological processes, making it a valuable biomarker. For instance, the PAM50 signature, consisting of 50 mRNA transcripts, is used for breast cancer subtyping and prognosis [15].

MicroRNA (miRNA)

miRNAs are small non-coding RNAs that regulate gene expression post-transcriptionally by binding to target mRNAs, leading to translational repression or mRNA degradation [21] [15]. Their remarkable stability in body fluids (e.g., blood, urine, saliva) due to protection within extracellular vesicles or by RNA-binding proteins makes them excellent biomarker candidates [15]. Specific isoforms of miRNAs, known as isomiRs, can display even higher discriminatory power than canonical miRNAs for cancer diagnosis [15].

Long Non-Coding RNA (lncRNA)

lncRNAs are defined as non-coding transcripts longer than 200 nucleotides [15] and represent a vast, heterogeneous RNA class. They exhibit more tissue-specific expression than protein-coding genes [15] and function through diverse mechanisms, including interactions with DNA, RNA, proteins, and chromatin-modifying complexes [21] [22]. Their specific expression patterns and roles in disease pathogenesis, especially cancer, underscore their growing biomarker potential [15] [24]. Examples include H19 for liver and bladder cancer, and HOTAIR for breast cancer prognosis [15].

The Role of Real-Time PCR in Transcriptional Biomarker Discovery

Real-time PCR, or quantitative PCR (qPCR), is a cornerstone technology in the biomarker development pipeline, bridging the gap between high-throughput discovery platforms like RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) and routine clinical application [15]. Its exceptional sensitivity, specificity, wide dynamic range, and quantitative capabilities make it indispensable for validating biomarker signatures identified through holistic discovery approaches [15] [25] [23].

The Biomarker Development Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the standard pipeline for developing and validating a transcriptional biomarker, highlighting the critical role of RT-qPCR.

Diagram 1: Transcriptional biomarker development workflow.

This workflow typically begins with hypothesis generation and target discovery, often using RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) for unbiased, holistic profiling of the transcriptome to identify differentially expressed RNA candidates [15] [26]. Bioinformatic analysis then refines these findings into a candidate biomarker signature [24]. The signature undergoes rigorous RT-qPCR validation using specific assays (e.g., TaqMan) on independent sample sets. This step is critical for confirming the accuracy and reproducibility of the biomarker signature using a highly specific and quantitative platform [15]. Finally, the validated signature moves into clinical validation, where its diagnostic accuracy (e.g., via Receiver Operating Characteristic - ROC analysis) and prognostic value (e.g., via survival analysis) are assessed in well-defined patient cohorts, paving the way for its development into a routine diagnostic assay [24].

Key Phases of RT-qPCR in Biomarker Workflows

- Discovery Support with High-Throughput qPCR: In early stages, function-tested RT-qPCR assays can facilitate high-throughput screening of dozens to hundreds of putative biomarker candidate genes from in silico selections across various models (e.g., cell lines, xenograft models) [23].

- Signature Verification: RT-qPCR is the gold-standard method for confirming the expression patterns of candidate biomarkers (e.g., lncRNAs, miRNAs) identified through discovery platforms like RNA-seq. This step often involves confirmation in both tissue and liquid biopsies [24].

- Analytical and Clinical Validation: For a biomarker to be clinically useful, its measurement must be robust and reproducible. Adherence to the MIQE (Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments) guidelines is essential at this stage to ensure experimental rigor, proper normalization using validated reference genes, and reliable data analysis [15].

Experimental Protocols for Biomarker Validation

This section outlines detailed methodologies for validating transcriptional biomarkers using RT-qPCR, from sample preparation to data analysis.

Sample Collection and Nucleic Acid Isolation

The choice of sample type and isolation method significantly impacts RNA quality and assay performance.

- Sample Types: Liquid biopsies (blood plasma, urine, saliva) are increasingly popular due to their minimally invasive nature and ability to provide systemic disease information [15]. Traditional solid tissues (fresh frozen or FFPE) are also widely used.

- Nucleic Acid Isolation: Commercial kits (e.g., Qiagen AllPrep DNA/RNA kits) are commonly used for concurrent DNA/RNA extraction from the same sample, which is crucial for integrated analyses [26]. For liquid biopsies, specialized protocols are required to isolate cell-free RNA (cfRNA) or RNA from extracellular vesicles.

- Quality Control (QC): RNA quantity and quality must be assessed using instruments like Qubit Fluorometer and TapeStation. Metrics such as RNA Integrity Number (RIN) are critical for FFPE samples, which often contain fragmented RNA [26].

Reverse Transcription and qPCR Assay Design

This phase converts RNA into a stable cDNA template and designs specific detection assays.

- Reverse Transcription: This is a critical "key step" where RNA is reverse-transcribed into complementary DNA (cDNA) using reverse transcriptase. The reaction conditions and enzyme choice must be optimized, especially for challenging samples like FFPE or for specific RNA types (e.g., miRNA requires specialized stem-loop primers) [15].

- Assay Design: For mRNA and lncRNA, assays are typically designed to span exon-exon junctions to avoid genomic DNA amplification. For miRNA, specific stem-loop RT primers and TaqMan assays are often employed due to their short length [25].

- Reference Gene Selection: Proper normalization using stable reference genes (e.g., GAPDH, tubulin, ribosomal RNAs) is fundamental for accurate quantification. Reference genes must be validated for the specific sample type and experimental condition [15] [27].

qPCR Execution and Data Analysis

The final experimental phase involves running the qPCR reaction and analyzing the data.

- qPCR Reaction: The reaction mix includes cDNA template, primers/probe, dNTPs, and a thermo-stable DNA polymerase in a suitable buffer. The process involves repeated cycles of denaturation, annealing, and extension in a thermal cycler equipped with optical modules to excite fluorophores and detect fluorescence [27].

- Detection Chemistry:

- Non-specific detection using DNA-binding dyes (e.g., SYBR Green) is cost-effective but requires melt curve analysis to confirm amplicon specificity.

- Sequence-specific DNA probes (e.g., TaqMan) provide superior specificity, enable multiplexing, and prevent false signals from primer-dimers, making them ideal for clinical biomarker validation [15] [27].

- Data Analysis: The quantification cycle (Cq) is the primary output, representing the cycle number at which fluorescence crosses a threshold. The Cq value is inversely proportional to the starting amount of the target transcript. Relative gene expression is typically calculated using the ΔΔCq method, which compares the Cq of the target gene to a reference gene across different sample groups [15] [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

The table below details key reagents and technologies essential for working with mRNA, miRNA, and lncRNA in biomarker research.

Table 2: Key research reagents and solutions for transcriptional biomarker analysis

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Application | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Isolation Kits | Parallel isolation of DNA and RNA from same sample; specialized isolation of cell-free RNA from liquid biopsies. | Qiagen AllPrep DNA/RNA kits [26]; kits optimized for FFPE tissue (e.g., AllPrep DNA/RNA FFPE Kit) or liquid biopsies. |

| Reverse Transcriptase Enzymes | Converts RNA into stable cDNA for subsequent PCR amplification; critical for assay performance. | Enzymes must be selected based on sample type (e.g., high efficiency for degraded RNA from FFPE). |

| TaqMan Assays | Sequence-specific probes and primers for highly specific target detection and quantification in qPCR. | Ideal for discriminating between highly homologous targets or quantifying small-fold changes; available for mRNA, miRNA, and lncRNA [25]. |

| MIQE Guidelines | A framework for ensuring the transparency, rigor, and reproducibility of qPCR experiments. | Critical for proper experimental design, reporting, and data analysis in biomarker validation studies [15]. |

| Normalization Reference Genes | Stable endogenous controls for reliable relative quantification of gene expression. | Housekeeping genes (GAPDH, tubulin) or ribosomal RNAs; must be validated for each experimental system [15] [27]. |

| Integrated RNA-seq & WES Assays | Holistic discovery platform for identifying biomarker signatures from DNA and RNA from a single sample. | BostonGene's Tumor Portrait assay; enables correlation of somatic alterations with gene expression and fusion detection [26]. |

The field of transcriptional biomarker research is rapidly evolving, driven by technological advancements. Key future trends expected to shape the field by 2025 include:

- Enhanced Integration of AI and Machine Learning: AI-driven algorithms will revolutionize biomarker data processing, enabling more sophisticated predictive models for disease progression and treatment response, automated data interpretation, and personalized treatment plans [28].

- Rise of Multi-Omics Approaches: Researchers will increasingly integrate data from genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics to identify comprehensive biomarker signatures that reflect the full complexity of diseases [28].

- Advancements in Liquid Biopsy and Single-Cell Analysis: Liquid biopsies are poised to become a standard tool, with improved sensitivity and specificity for early detection and real-time monitoring [28]. Single-cell analysis technologies will provide deeper insights into tumor heterogeneity and identify rare cell populations driving disease [28].

In conclusion, mRNA, miRNA, and lncRNA each offer unique advantages and challenges as transcriptional biomarkers. Their successful translation into clinical tools relies heavily on a robust development pipeline in which real-time PCR remains an indispensable technology for validation and verification. By adhering to rigorous guidelines like MIQE and leveraging emerging trends in multi-omics and AI, researchers can harness the full potential of these RNA types to advance personalized medicine and improve patient outcomes.

From Raw Data to Reliable Results: qPCR Workflows for Biomarker Analysis

This whitepaper details the core experimental protocol for real-time reverse transcription PCR (RT-qPCR), a cornerstone technology in the discovery and validation of transcriptional biomarkers. The accuracy of this method is paramount for molecular diagnostics and drug development, as it directly influences the reliability of gene expression data used to identify disease states and therapeutic targets. This guide provides researchers with a standardized framework encompassing in silico primer design, robust laboratory setup, and optimized thermal cycling parameters to ensure the generation of precise, reproducible, and meaningful results in transcriptional biomarker research.

Transcriptional biomarkers, which are measurable indicators of biological state based on RNA expression levels, have revolutionized molecular diagnostics and personalized medicine. They offer a dynamic view into cellular processes, allowing for the detection of diseases long before symptoms manifest or proteins are produced [15]. The transcriptome includes protein-coding messenger RNA (mRNA) and various non-coding RNAs, such as microRNA (miRNA) and long non-coding RNA (lncRNA), many of which have demonstrated high discriminatory power as biomarkers for cancers, infectious diseases, and other pathologies [15] [29].

Among the technologies available for quantifying these biomarkers, RT-qPCR remains the gold standard due to its exceptional sensitivity, specificity, broad dynamic range, and relative cost-effectiveness [15] [30]. Its ability to reliably detect and quantify RNA from minimal sample input, such as liquid biopsies, makes it indispensable for both foundational research and clinical assay development [15]. The subsequent sections of this guide will provide a detailed, actionable protocol to ensure that this powerful technique is implemented with the rigor required for robust transcriptional biomarker research.

In Silico Primer and Probe Design

The foundation of a successful RT-qPCR assay lies in the meticulous design of primers and probes. Specificity here is critical to accurately measure the intended biomarker without cross-reacting with homologous genes or non-target sequences.

Core Design Parameters

The following parameters are essential for designing effective primers and probes [31] [32].

Table 1: Core Design Guidelines for Primers and Probes

| Parameter | Primer Guidelines | Probe Guidelines (TaqMan) |

|---|---|---|

| Length | 18–30 nucleotides | 20–30 nucleotides |

| Melting Temperature (Tm) | 60–64°C; difference between forward & reverse ≤ 2°C | 5–10°C higher than primers |

| GC Content | 35–65% (ideal: 50%) | 35–65%; avoid 'G' at 5' end |

| Amplicon Length | 70–200 base pairs (ideal for qPCR: 90-110 bp) | N/A |

| 3' End | Avoid stable secondary structures and complementary | N/A |

Ensuring Specificity and Efficiency

- Avoiding Secondary Structures: Screen all oligonucleotides for self-dimers, heterodimers, and hairpin loops. The ΔG value for any secondary structure should be weaker (more positive) than –9.0 kcal/mol to prevent stable, non-productive structures from forming [31] [33]. Tools like the IDT OligoAnalyzer are indispensable for this analysis.

- Genomic DNA Control: Design primers to span an exon-exon junction, thereby ensuring amplification only from cDNA and not from contaminating genomic DNA [31] [32].

- Specificity Validation: Always perform an in silico specificity check using tools like NCBI Primer-BLAST to confirm that primers are unique to the desired target sequence across all homologous genes, a step especially critical in plant and animal genomes with gene families [31] [34].

Experimental Workflow and Reaction Setup

A rigorous wet-lab protocol is essential for converting a well-designed in silico assay into reliable quantitative data.

RNA Isolation and Quality Control (QC)

The quality of the starting RNA template is the most critical variable. RNA should be extracted using a robust method (e.g., column-based kits) and must undergo stringent QC [32]:

- Purity: Assess spectrophotometrically (A260/A280 ratio ~2.0; A260/A230 ratio >1.8).

- Integrity: Verify via denaturing agarose gel electrophoresis, observing sharp 28S and 18S ribosomal RNA bands, or using specialized instruments like a Bioanalyzer.

cDNA Synthesis (Two-Step Protocol)

The reverse transcription reaction converts RNA into stable cDNA.

- Input Standardization: Use a standardized amount of high-quality total RNA (e.g., 500 ng) per reaction to ensure comparability across samples [35] [32].

- Genomic DNA Control: Include a no-reverse transcriptase control (-RT control) for each sample to detect genomic DNA contamination [32].

- Thermal Cycling: A typical protocol involves primer annealing (25°C for 2 min), cDNA synthesis (55°C for 10-60 min), and enzyme heat inactivation (95°C for 1 min) [35] [32]. The resulting cDNA should be diluted (e.g., 1:10 to 1:20) before use in qPCR.

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) Setup

- Master Mix Preparation: Assemble reactions on ice using a pre-formulated qPCR master mix. Prepare a single master mix for each gene to minimize pipetting errors and ensure well-to-well consistency [35] [32].

- Reaction Composition: A standard 20 µL reaction contains [32]:

- 10 µL of 2X qPCR Master Mix

- 0.5 µL each of Forward and Reverse Primer (10 µM stock)

- 5 µL of diluted cDNA template

- 4 µL Nuclease-Free Water

- Essential Controls:

- No-Template Control (NTC): Contains water instead of cDNA to check for reagent contamination.

- -RT Control: To confirm the absence of gDNA amplification.

Table 2: The Scientist's Toolkit - Essential Reagents and Equipment

| Category | Item | Function & Note |

|---|---|---|

| Core Reagents | RNA Isolation Kit | Obtains pure, intact RNA; column-based (e.g., RNeasy, Zymo Research) are common. |

| Reverse Transcription Kit | Converts RNA to cDNA; contains reverse transcriptase, buffer, dNTPs. | |

| qPCR Master Mix | Core of amplification; contains hot-start DNA polymerase, dNTPs, MgCl₂, and fluorescent reporter (SYBR Green or probe). | |

| Primers & Probes | Sequence-specific oligonucleotides for target amplification and detection. | |

| Critical Controls | No-RT Control | Detects genomic DNA contamination. |

| No-Template Control (NTC) | Detects reagent/labware contamination. | |

| Positive Control | Confirms assay functionality; use a sample with known target expression. | |

| Inter-Plate Calibrator | Controls for run-to-run variation. | |

| Equipment | Real-time PCR Cycler | Instrument for thermal cycling and fluorescence detection. |

| Spectrophotometer | Measures nucleic acid concentration and purity (e.g., NanoDrop). | |

| RNase Decontamination Solution | Eliminates RNases from surfaces and equipment to protect sample integrity. |

Thermal Cycling and Data Acquisition

The thermal cycler is not merely a heating block; its performance is a key determinant of assay specificity, efficiency, and speed.

Standard Thermal Cycling Profile

A universal cycling protocol for SYBR Green-based detection is outlined below. Note that the annealing temperature (Ta) must be optimized for each primer pair.

Table 3: Standard qPCR Thermal Cycling Parameters

| Step | Temperature | Time | Cycles | Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Denaturation | 95°C | 5–15 min | 1 | Activates hot-start polymerase; fully denatures complex templates. |

| Denaturation | 95°C | 10–30 sec | Separates double-stranded DNA. | |

| Annealing | 55–65°C* | 20–30 sec | 35–45 | Allows primers to bind to the template. |

| Extension/Data Acquisition | 72°C | 20–30 sec | Polymerase extends the primers. Fluorescence is measured at this step in each cycle. | |

| Melt Curve Analysis | 65°C to 95°C, read every 0.2–0.5°C | 1 | Verifies amplification of a single, specific product. |

*The annealing temperature is typically set 5°C below the primer Tm and must be determined empirically [31] [35].

Instrument Considerations and Fast PCR

- Thermal Cycler Performance: Critical metrics include temperature accuracy (how close the block is to the setpoint) and uniformity (consistency across all wells), as these directly impact amplification efficiency and reproducibility [36].

- Fast PCR: Advancements in polymerase enzymes and instrument design (faster ramp rates) enable "Fast PCR" protocols. These can reduce run times from ~2 hours to under 1 hour without compromising sensitivity or specificity, as demonstrated in SARS-CoV-2 diagnostics [37]. This is particularly beneficial for high-throughput biomarker validation.

Quality Control and Data Analysis

Robust quality control is non-negotiable for data integrity in biomarker research.

- Amplification Efficiency: Determine via a standard curve of serially diluted cDNA. The ideal efficiency is 90–110% (a slope of -3.1 to -3.6), which is a prerequisite for accurate quantification using the comparative Ct (2–ΔΔCt) method [34] [30] [32].

- Melt Curve Analysis: For SYBR Green assays, a single, sharp peak in the melt curve confirms the amplification of a single, specific product. Multiple peaks indicate primer-dimer formation or non-specific amplification [35] [32].

- Reference Gene Validation: The choice of reference genes (e.g., GAPDH, ACTB, cyclophilin A) for normalization must be experimentally validated for stability under the specific experimental conditions. Unstable reference genes are a major source of error in gene expression studies [35] [34] [32].

Mastering the core protocol of primer design, reaction setup, and thermal cycling is fundamental to leveraging the full power of RT-qPCR in transcriptional biomarker discovery. By adhering to the detailed guidelines presented in this whitepaper—from in silico design that accounts for genetic homology to meticulous laboratory practice and rigorous quality control—researchers can generate data of the highest quality. This rigor ensures that transcriptional biomarkers can be reliably discovered and validated, accelerating their translation into clinical diagnostics and personalized therapeutic strategies.

In the realm of transcriptional biomarker discovery, real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) remains the gold standard for validating gene expression patterns due to its exceptional sensitivity, specificity, and dynamic range [38] [39]. However, the precision of this powerful technique is entirely dependent on appropriate normalization to control for technical variations introduced during RNA isolation, reverse transcription, and PCR amplification [40]. The identification of stable reference genes—formerly called housekeeping genes—represents a critical methodological step that underpins the validity of all subsequent expression data and biological conclusions.

Historically, researchers normalized gene expression against a single, presumed invariant internal control, such as β-actin (ACTB) or glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). This practice has been fundamentally challenged by accumulating evidence demonstrating that the expression of these classic reference genes can vary significantly across different tissues, developmental stages, and experimental conditions [40] [41]. Such variability introduces substantial bias, potentially leading to erroneous biological interpretations. As emphasized by Bustin et al. (2009), failing to implement appropriate normalization controls represents one of the most frequent pitfalls in qPCR experimental design, threatening the reliability of countless studies [38]. Within biomarker discovery pipelines, where subtle expression differences may carry profound diagnostic or therapeutic implications, rigorous reference gene validation transitions from a recommended practice to an absolute necessity.

The Critical Need for Systematic Validation

The assumption that commonly used reference genes maintain constant expression levels has been systematically debunked across diverse biological contexts. A seminal study by Vandesompele et al. (2002) demonstrated that using a single reference gene for normalization can lead to significant errors—in some cases exceeding 20-fold differences—in a substantial proportion of samples tested [40]. This problem is exacerbated in complex experimental systems, such as developmental time courses or disease progression models, where cellular composition and metabolic activity are inherently dynamic [41].

The consequences of inappropriate normalization are not merely theoretical. Investigations have revealed that the expression of commonly used reference genes can fluctuate dramatically under experimental conditions. For instance, during early postnatal development of the mouse cerebellum, mRNA levels of candidate reference genes like Tbp and Gapdh exhibited significant variation, with fold changes that would profoundly skew the normalized expression profile of target genes like Mbp [41]. Similarly, in clinical samples, the ratio of rRNA to mRNA can vary significantly, as evidenced by imbalances observed in approximately 7.5% of mammary adenocarcinomas, rendering normalization to total RNA mass unreliable [40]. These findings underscore a fundamental principle: reference gene stability must be empirically determined for each specific experimental system rather than assumed based on convention or historical usage.

Table 1: Consequences of Improper Normalization Demonstrated in Various Studies

| Experimental Context | Observation | Impact on Normalized Data | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse Cerebellum Development | Actb mRNA levels varied significantly across postnatal time points | Mbp expression profiles showed dramatically different kinetics | [41] |

| Human Tissue Panels | Expression ratios of common reference genes (e.g., ACTB, GAPDH) varied between samples | Potential for >20-fold errors in expression calculations | [40] |

| Mammary Adenocarcinomas | rRNA:mRNA ratio imbalance in 7.5% of samples | Normalization to total RNA introduces significant errors | [40] |

Selection of Candidate Reference Genes

The initial step in the validation pipeline involves selecting a panel of candidate reference genes for evaluation. Traditional approaches selected candidates based on their known involvement in basic cellular maintenance, including genes encoding structural proteins (e.g., β-actin, tubulin), glycolytic enzymes (e.g., GAPDH), or proteins involved in protein synthesis (e.g., ribosomal proteins) [38] [42]. However, contemporary strategies increasingly leverage transcriptomics data to identify genes with inherently stable expression across specific experimental conditions [43] [44].

An effective candidate panel should include genes from diverse functional classes to minimize the likelihood of co-regulation, which represents a key consideration in selection strategy [40]. For example, a robust panel might include genes involved in different cellular processes such as cytoskeletal structure (ACTB, TUB), glycolysis (GAPDH), protein degradation (UBC), and translation (RPL13A, RPS). The number of candidate genes typically ranges from 7 to 12, providing sufficient diversity for comprehensive stability analysis without becoming prohibitively labor-intensive [45] [43] [41].

Table 2: Common Candidate Reference Genes and Their Cellular Functions

| Gene Symbol | Gene Name | Primary Cellular Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACTB/ACT | β-Actin | Cytoskeletal structural protein | Highly abundant; often varies across conditions |

| GAPDH | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | Glycolytic enzyme | Expression affected by cellular metabolism |

| TUB | Tubulin | Cytoskeletal structural protein | May vary during cell division/differentiation |

| UBC | Ubiquitin C | Protein degradation | Multiple isoforms; generally stable |

| RPS/RPL | Ribosomal proteins | Protein synthesis | High abundance; potential variation |

| EF1α/EEF1A | Elongation Factor 1-α | Protein translation | Often highly stable across conditions |

| B2M | Beta-2-microglobulin | MHC class I component | May vary in immune contexts |

| HPRT1 | Hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase 1 | Purine synthesis | Moderate expression; generally stable |

Methodological Framework for Validation

Experimental Design and RNA Quality Control

Robust validation begins with proper experimental design that incorporates biological replicates representing the entire scope of the intended experimental conditions. RNA integrity represents a fundamental prerequisite for reliable qPCR data; degraded RNA samples inevitably yield variable results regardless of normalization strategy [38]. Quality assessment should include spectrophotometric measurement (A260/280 ratios ~1.9-2.1) and evaluation via denaturing gel electrophoresis to confirm the presence of sharp, distinct ribosomal RNA bands [45]. More sophisticated approaches may employ the SPUD assay or RNA Integrity Number (RIN) assessment, though researchers should note that RIN algorithms were originally optimized for mammalian tissues and may require adaptation for plants or other organisms [38].

Primer Design and Amplification Efficiency