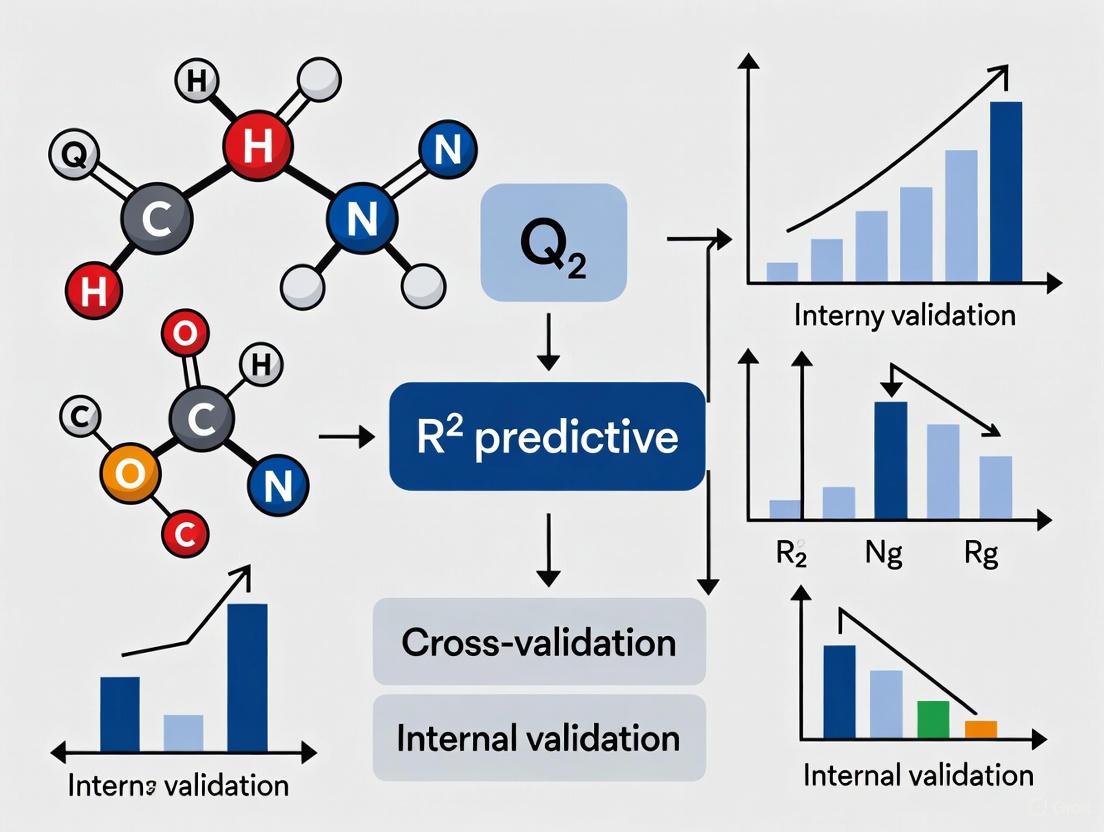

QSAR Validation Demystified: A Practical Guide to Q², R², and Predictive R²

This article provides a comprehensive overview of essential validation metrics for Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models, crucial for researchers and drug development professionals.

QSAR Validation Demystified: A Practical Guide to Q², R², and Predictive R²

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of essential validation metrics for Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models, crucial for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational principles of internal validation (Q²), model fit (R²), and external validation (predictive R²), explaining their roles in assessing model robustness and predictive power. The content delves into methodological best practices for application, addresses common troubleshooting and optimization scenarios, and explores advanced and comparative validation techniques, including novel parameters like rm². By synthesizing these concepts, the article aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to build, validate, and reliably deploy predictive QSAR models in regulatory and research settings.

QSAR Validation Fundamentals: Understanding Q², R², and Predictive R²

The Critical Importance of Validation in QSAR Modeling

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling represents one of the most important computational tools employed in drug discovery and development, providing statistically derived connections between chemical structures and biological activities [1]. These mathematical models predict physicochemical and biological properties of molecules from numerical descriptors encoding structural features [2]. As QSAR applications expand into regulatory decision-making, including frameworks like REACH in the European Union, the scientific validity of these models becomes paramount for regulatory bodies to make informed decisions [2] [1].

Validation has emerged as a crucial aspect of QSAR modeling, serving as the final gatekeeper that determines whether a model can be reliably applied for predicting new compounds [2] [3]. The estimation of prediction accuracy remains a critical problem in QSAR modeling, with validation strategies providing the necessary checks to ensure developed models deliver reliable predictions for new chemical entities [2] [4]. Without proper validation, QSAR models may produce misleading results, potentially derailing drug discovery efforts or leading to incorrect regulatory assessments.

Traditional Validation Metrics and Their Limitations

Fundamental Validation Parameters

QSAR model validation traditionally relies on several established metrics that assess different aspects of model performance:

Internal Validation (Q²): Typically performed using leave-one-out (LOO) or leave-some-out (LSO) cross-validation, where portions of the training data are systematically excluded during model development and then predicted. The cross-validated R² (Q²) is calculated as Q² = 1 - Σ(Yobs - Ypred)² / Σ(Yobs - Ÿ)², where Yobs and Ypred represent observed and predicted activity values, and Ÿ is the mean activity value of the entire dataset [4]. Traditionally, Q² > 0.5 is considered indicative of a model with predictive ability [4].

External Validation (R²pred): Conducted by splitting available data into training and test sets, where models developed on training compounds predict the held-out test compounds. Predictive R² is calculated as R²pred = 1 - Σ(Ypred(Test) - Y(Test))² / Σ(Y(Test) - Ÿtraining)², where Ypred(Test) and Y(Test) indicate predicted and observed activity values of test set compounds, and Ÿtraining represents the mean activity value of the training set [4].

Model Fit (R²): The conventional coefficient of determination indicating how well the model explains variance in the training data.

Identified Limitations and the Need for Improved Metrics

Research has revealed significant limitations in these traditional validation parameters:

Inconsistency Between Internal and External Predictivity: High internal predictivity (Q²) may result in low external predictivity (R²pred) and vice versa, with no consistent relationship between the two [2] [4].

Dependence on Training Set Mean: Both Q² and R²pred use deviations of observed values from the training set mean as a reference, which can lead to artificially high values without truly reflecting absolute differences between observed and predicted values [5].

Overestimation of Predictive Capacity: Leave-one-out cross-validation has been criticized for frequently overestimating a model's true predictive capacity, especially with structurally redundant datasets [4].

These limitations have prompted the development of more stringent validation parameters that provide a more realistic assessment of model predictivity [2] [5] [3].

Advanced Validation Metrics for Stringent Assessment

The rm² Metrics and Their Variants

Roy and colleagues developed the rm² metric as a more stringent validation parameter that addresses key limitations of traditional approaches [2] [5]. Unlike Q² and R²pred, rm² considers the actual difference between observed and predicted response data without reliance on training set mean, providing a more direct assessment of prediction accuracy [5].

The rm² parameter has three distinct variants, each serving a specific validation purpose:

rm²(LOO): Used for internal validation, based on correlation between observed and leave-one-out predicted values of training set compounds [2] [5].

rm²(test): Applied for external validation, calculated using observed and predicted values of test set compounds [2] [5].

rm²(overall): Analyzes overall model performance considering predictions for both internal (LOO) and external validation sets, providing a comprehensive assessment based on a larger number of compounds [2] [5].

The rm²(overall) statistic is particularly valuable when test set size is small, as it incorporates predictions from both training and test sets, making it more reliable than external validation parameters based solely on limited test compounds [2].

Additional Stringent Validation Parameters

Randomization Test Parameter (Rp²): This parameter penalizes model R² for large differences between the determination coefficient of the non-random model and the square of the mean correlation coefficient of random models in randomization tests [2]. It addresses the requirement that for an acceptable QSAR model, the average correlation coefficient (Rr) of randomized models should be less than the correlation coefficient (R) of the non-randomized model.

Concordance Correlation Coefficient (CCC): Gramatica and coworkers suggested CCC for external validation of QSAR models, with CCC > 0.8 typically indicating a valid model [3]. The CCC is calculated as: CCC = [2Σ(Yi - Ÿ)(Yi' - Ÿi')] / [Σ(Yi - Ÿ)² + Σ(Yi' - Ÿi')² + nEXT(Ÿi' - Ÿi')²], where Yi is the experimental value, Ÿ is the average of experimental values, Yi' is the predicted value, and Ÿi' is the average of predicted values [3].

Golbraikh and Tropsha Criteria: This approach proposes multiple conditions for model validity: (i) r² > 0.6 for the correlation between experimental and predicted values; (ii) slopes of regression lines through origin (K and K') between 0.85 and 1.15; and (iii) (r² - r₀²)/r² < 0.1 or (r² - r₀'²)/r² < 0.1, where r₀² and r₀'² are coefficients of determination for regression through origin [3].

Table 1: Comparison of Key QSAR Validation Metrics

| Metric | Validation Type | Calculation Basis | Acceptance Threshold | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q² | Internal | Leave-one-out cross-validation | > 0.5 | Assesses model robustness |

| R²pred | External | Test set predictions | > 0.6 | Estimates external predictivity |

| rm² | Internal/External/Both | Direct observed vs. predicted comparison | Higher values preferred | Independent of training set mean |

| Rp² | Randomization | Comparison with randomized models | Higher values preferred | Penalizes models susceptible to chance correlation |

| CCC | External | Agreement between observed and predicted | > 0.8 | Measures concordance, not just correlation |

Experimental Protocols for QSAR Validation

Standard Model Development and Validation Workflow

Implementing proper experimental protocols is essential for rigorous QSAR validation. The following workflow outlines key stages in QSAR model development and validation:

Diagram Title: QSAR Model Validation Workflow

Detailed Methodologies for Key Validation Experiments

Data Collection and Curation Protocol:

- Collect biological activity data from reliable sources (e.g., ChEMBL, AODB) with consistent experimental protocols [6].

- For antioxidant QSAR models, filter data based on specific assay types (e.g., DPPH radical scavenging activity with 30-minute time frame) to ensure consistency [6].

- Convert activity values to appropriate forms (e.g., IC50 to pIC50 = -logIC50) to achieve more Gaussian-like distribution [6].

- Remove duplicates using International Chemical Identifier (InChI) and canonical SMILES, calculating coefficient of variation (CV = σ/μ) with a cut-off of 0.1 to eliminate duplicates with high variability [6].

- Neutralize salts, remove counterions and inorganic elements, and exclude compounds with molecular weight >1000 Da [6].

Descriptor Calculation and Dataset Splitting:

- Calculate molecular descriptors using software packages like Mordred Python package, Dragon, or Cerius2, encompassing topological, structural, physicochemical, and spatial descriptors [2] [6].

- Split dataset into training and test sets using rational methods such as K-means clustering of factor scores, Kennard-Stone method, or sphere exclusion algorithm rather than random selection to ensure representative chemical space coverage [4].

Model Development and Validation Implementation:

- Develop models using training set with appropriate statistical techniques (multiple linear regression, partial least squares, machine learning algorithms) [3] [6].

- Perform internal validation using leave-one-out cross-validation to calculate Q² and rm²(LOO).

- Conduct external validation by predicting test set compounds to calculate R²pred and rm²(test).

- Execute randomization tests (Y-scrambling) with multiple iterations (typically 100-1000 permutations) to calculate Rp² and verify models are not based on chance correlations [2] [4].

- Calculate overall validation metrics including rm²(overall) and CCC for comprehensive assessment.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for QSAR Validation

| Reagent/Resource | Category | Function in QSAR Validation | Example Tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Descriptor Packages | Software | Calculate numerical representations of chemical structures | Dragon, Mordred, Cerius2 |

| Chemical Databases | Data Source | Provide curated biological activity data for model development | ChEMBL, AODB, PubChem |

| Statistical Analysis Software | Software | Perform regression and machine learning modeling | R, Python, SPSS |

| QSAR Validation Tools | Software | Calculate validation metrics and perform randomization tests | QSARINS, VEBIAN |

| Chemical Structure Standardization Tools | Software | Prepare and curate chemical structures for modeling | RDKit, OpenBabel |

Comparative Analysis of Validation Approaches

Performance Comparison of Validation Metrics

Comparative studies have revealed important insights about the effectiveness of different validation approaches:

Studies analyzing 44 reported QSAR models found that employing the coefficient of determination (r²) alone could not indicate the validity of a QSAR model [3]. The established criteria for external validation have distinct advantages and disadvantages that must be considered in QSAR studies.

Research demonstrates that models could satisfy conventional parameters (Q² and R²pred) but fail to achieve required values for novel parameters rm² and Rp², indicating these newer metrics provide more stringent assessment [2].

The impact of training set size on prediction quality varies significantly across different datasets and descriptor types, with no general rule applicable to all scenarios [4]. For some datasets, reduction of training set size significantly impacts predictive ability, while for others, no substantial effect is observed.

Regulatory Applications and Best Practices

The evolution of QSAR validation has significant implications for regulatory applications:

For regulatory use, especially under frameworks like REACH, QSAR models must satisfy stringent validation criteria to ensure reliable predictions for untested compounds [2] [7].

Studies evaluating QSAR models for predicting environmental fate of cosmetic ingredients found that qualitative predictions classified by regulatory criteria are often more reliable than quantitative predictions, and the Applicability Domain (AD) plays a crucial role in evaluating model reliability [7].

Best practices recommend that QSAR modeling should ultimately lead to statistically robust models capable of making accurate and reliable predictions of biological activities, with special emphasis on statistical significance and predictive ability for virtual screening applications [4].

QSAR model validation has evolved significantly from reliance on traditional parameters like Q² and R²pred to more stringent metrics including rm², Rp², and CCC. These advanced validation approaches provide more rigorous assessment of model predictivity, addressing limitations of conventional methods and offering enhanced capability to identify truly predictive models. As QSAR applications expand in drug discovery, toxicity prediction, and regulatory decision-making, implementing comprehensive validation protocols incorporating both traditional and novel metrics becomes increasingly important. The scientific community continues to refine validation strategies, with current research emphasizing the importance of applicability domain consideration, appropriate dataset splitting methods, and multiple validation metrics to ensure QSAR models deliver reliable predictions for new chemical entities.

In the field of Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling, the validation of predictive models is paramount for their reliable application in drug discovery and development. Among the various statistical tools employed, the coefficient of determination, R², is a fundamental metric for assessing model performance. However, its interpretation and sufficiency as a standalone measure of model validity are subjects of ongoing scrutiny and debate within the scientific community. This guide objectively examines the role of R² alongside other established validation metrics, such as Q² and predictive R², to provide researchers with a clear framework for evaluating QSAR models.

What is R²? Core Definition and Calculation

At its core, R² is a statistical measure that represents the proportion of the variance in the dependent variable that is predictable from the independent variable(s). It provides a quantitative assessment of how well the model's predictions match the observed experimental data.

The most recommended formula for calculating R², which is applicable to various modeling techniques including linear regression and machine learning, is given by [8]:

R² = 1 - Σ(y - ŷ)² / Σ(y - ȳ)²

Where:

- y is the observed response variable (e.g., biological activity).

- ȳ is the mean of the observed values.

- ŷ is the corresponding predicted value from the model.

In essence, R² compares the sum of squared residuals (the difference between observed and predicted values) of your model to the sum of squared residuals of a naive model that only predicts the mean value. A perfect model would have an R² of 1, indicating it explains all the variance in the data [8].

R² in the Context of QSAR Model Validation

QSAR model development involves a critical validation stage to ensure the model is robust and possesses reliable predictive power for new, untested compounds. The validation process typically involves different data subsets, and R² is calculated for each to assess different aspects of model performance [8].

Training Set: Data used directly to build the model. The R² calculated for this set (sometimes called fitted R²) indicates how well the model fits the data it was trained on. However, a high training R² alone is insufficient and can lead to overfit models that perform poorly on new data.

Test Set (or External Validation Set): Data that is withheld during model building and used solely to evaluate the model's predictive ability. The R² calculated on this set, often denoted as predictive R² or R²pred, is considered a more reliable and stringent indicator of a model's real-world utility [9] [8]. The independent test set is often regarded as the "gold standard" for assessing predictive power [8].

Limitations and Pitfalls of R² as a Standalone Metric

A critical analysis of QSAR literature reveals that relying solely on the R² value, particularly for the training set, is a profound limitation. A comprehensive study analyzing 44 reported QSAR models found that employing the coefficient of determination (r²) alone could not indicate the validity of a QSAR model [9] [3].

The primary pitfalls include:

- Insensitivity to Prediction Accuracy: A model can achieve a high R² value without making accurate predictions. This can occur if the model consistently over- or under-predicts the response variable, as R² primarily measures the proportion of variance explained, not the absolute agreement between observed and predicted values [5] [8].

- Dependence on Training Set Mean: Traditional validation metrics like R²pred compare predicted residuals to the deviations of the observed values from the training set mean. This can sometimes lead to deceptively high values without truly reflecting the absolute differences between observed and predicted values, especially for datasets with a wide range [5] [2].

Comparison of QSAR Validation Metrics: Beyond R²

Due to the limitations of R², several other statistical parameters have been developed and adopted by the QSAR community to provide a more rigorous and holistic validation of models. The table below summarizes key metrics and their performance based on an analysis of 44 QSAR models [9] [3].

Table 1: Comparison of Key Metrics for QSAR Model Validation

| Metric | Full Name | Purpose | Acceptance Threshold | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R² | Coefficient of Determination | Measures goodness-of-fit of the model. | > 0.6 (for external set) [3] | Simple, intuitive measure of explained variance. |

| Q² (q²) | Cross-validated R² | Estimates internal predictive ability via procedures like Leave-One-Out (LOO). | Varies, but must not be close to 1 without external validation [8] | Helps guard against overfitting. |

| R²pred | Predictive R² | Assesses predictive power on an external test set. | > 0.5 or 0.6 [9] | Gold standard for external validation. |

| rₘ² | Modified r² | A more stringent measure of predictivity that penalizes for large differences between observed and predicted values. | > 0.5 [5] [2] | Does not rely on training set mean; stricter than R²pred. |

| CCC | Concordance Correlation Coefficient | Measures both precision and accuracy (agreement with the line of perfect concordance). | > 0.8 [3] | Evaluates both linear relationship and exact agreement. |

| - | Golbraikh & Tropsha Criteria | A set of multiple criteria for external validation (includes slopes of regression lines). | Multiple conditions must be met [3] | Provides a multi-faceted assessment of model acceptability. |

The following decision pathway can guide researchers in selecting the appropriate validation metrics:

Experimental Protocols for Rigorous QSAR Validation

To ensure the development of a predictive and reliable QSAR model, a rigorous validation protocol must be followed. The workflow below outlines the key stages, emphasizing the role of different metrics at each step.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for QSAR Modeling

| Category / Tool | Specific Examples | Function in QSAR Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| Descriptor Calculation Software | Dragon Software, Image Analysis (for 2D-QSAR), Force Field Calculations (for 3D-QSAR) [9] | Translates chemical structures into numerical descriptors that serve as independent variables in the model. |

| Statistical & Machine Learning Platforms | Multiple Linear Regression (MLR), Partial Least Squares (PLS), Artificial Neural Networks (ANN), Genetic Function Approximation (GFA) [9] [2] | Develops the mathematical relationship between molecular descriptors and the biological activity. |

| Validation & Analysis Tools | Leave-One-Out (LOO) Cross-Validation, Bootstrapping, External Test Set Validation, Randomization Tests [8] [2] | Assesses model robustness, internal performance, and, most critically, external predictive power. |

| Data Sources | ChEMBL, PubChem, In-house corporate databases [10] | Provides high-quality, experimental biological activity data (e.g., IC50, Ki) for model training and testing. |

The standard workflow for a robust QSAR study involves:

- Data Collection and Curation: A set of compounds with their experimental biological activities (e.g., IC50, Ki) is collected from literature or databases like ChEMBL [10]. The data is then converted to a suitable scale (e.g., pIC50 = -logIC50) and carefully curated.

- Descriptor Calculation and Screening: Molecular descriptors are calculated using software tools. Redundant or irrelevant descriptors are filtered out to reduce noise and the risk of overfitting.

- Data Set Division: The entire data set is divided into a training set (used to build the model) and a test set (withheld for external validation). This can be done randomly or via methods like clustering to ensure representativeness [8].

- Model Development: A statistical or machine-learning algorithm is applied to the training set to establish a quantitative relationship between the descriptors and the activity.

- Model Validation:

- Internal Validation: Performed on the training set using techniques like Leave-One-Out (LOO) cross-validation, yielding metrics like Q² [8].

- External Validation: The final model is applied to predict the activity of the unseen test set compounds. This step calculates R²pred and other advanced metrics like rₘ² and CCC [9] [3].

- Applicability Domain: The chemical space where the model can make reliable predictions is defined.

The coefficient of determination, R², is an essential but incomplete metric for evaluating QSAR models. While it provides a valuable initial check on model fit, it must not be used in isolation. The scientific consensus, supported by empirical studies on dozens of models, firmly concludes that a high R² is not a guarantee of model validity or predictive power [9] [3].

Best practices for QSAR researchers and consumers of QSAR data include:

- Mandatory External Validation: Always validate models using a true external test set that was not involved in any stage of model building or selection [8].

- Adopt a Multi-Metric Approach: Rely on a suite of validation parameters. A robust model should simultaneously satisfy acceptable thresholds for R²pred, rₘ², and/or CCC [5] [3] [2].

- Report Transparently: Clearly document the source of data, the method of data splitting, and all validation statistics for both training and test sets. This allows for an objective assessment of the model's utility in drug development projects.

In Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling, internal validation is a crucial process for ensuring that developed models are reliable and predictive before their application for screening new compounds. The Organization for Economic and Co-operation and Development (OECD) explicitly includes, in its fourth principle, the requirement for "appropriate measures of goodness-of–fit, robustness and predictivity" for any QSAR model [11]. Internal validation primarily assesses a model's robustness—its ability to maintain stable performance when confronted with variations in the training data [11] [12].

Among the various metrics for internal validation, the Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation coefficient of determination (Q² LOO-CV), commonly referred to simply as Q², is a cornerstone. It provides an estimate of a model's predictive performance by systematically excluding parts of the training data, making it a key indicator of how well the model might perform on new, unseen data [11] [2].

This article explores Q² LOO-CV in detail, comparing it with other common validation metrics such as R² and predictive R², and situating it within the broader context of QSAR model validation for drug development.

Demystifying Q² (LOO-CV Q²): Concept and Calculation

The Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation Procedure

Q² LOO-CV is estimated through a specific resampling procedure. The following workflow illustrates the iterative process of Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation:

As shown in Figure 1, the LOO-CV process involves the following steps:

- Iterative Exclusion: Each compound in the training set (of size

n) is systematically omitted once [11]. - Model Training: For each iteration, a model is built using the remaining

n-1compounds. - Prediction: The omitted compound's activity is predicted using the model built without it.

- Prediction Aggregation: After all

niterations, the predicted activities for all compounds are collected.

The Q² Calculation Formula

The Q² value is calculated from these collected predictions using the following formula:

Q² = 1 - [ ∑(Yobserved - Ypredicted)² / ∑(Yobserved - Ȳtraining)² ]

Where:

- ∑(Yobserved - Ypredicted)² is the Predictive Sum of Squares (PRESS)

- ∑(Yobserved - Ȳtraining)² is the Total Sum of Squares of the training set activities

- Ȳ_training is the mean activity of the training set compounds

In essence, Q² represents the fraction of the total variance in the data that is explained by the model in cross-validation. A Q² value closer to 1.0 indicates a model with high predictive power, while a low or negative Q² suggests a non-predictive model [2].

Comparing Validation Metrics: A QSAR Researcher's Toolkit

QSAR model validation employs a suite of metrics, each providing unique insights into different aspects of model performance. The table below summarizes the purpose, strengths, and limitations of key metrics.

Table 1: Comparison of Key QSAR Validation Metrics

| Metric | Type | Purpose | Strengths | Limitations & Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q² (LOO-CV) | Internal Validation (Robustness) | Estimates model predictability by internal resampling. | - Efficient with limited data [2].- Standardized, widely accepted.- Directly relates to OECD principles [11]. | - Can overestimate performance on small samples [11].- May be insufficient for non-linear models like ANN/SVM [11]. |

| R² | Goodness-of-Fit | Measures how well the model fits the training data. | - Simple, intuitive interpretation.- Standard output for regression. | - Measures description, not prediction.- Highly susceptible to overfitting; can be misleadingly high [11] [3]. |

| Predictive R² (R²pred) | External Validation (Predictivity) | Assesses performance on a truly external, unseen test set. | - Gold standard for real-world predictability [11].- Not influenced by training data fitting. | - Requires holding back data, wasteful for small sets [2].- Value can be highly dependent on training set mean and test set selection [2] [3]. |

| r²m | Enhanced Validation (Internal/External) | Stricter parameter penalizing large differences between observed/predicted values [2]. | - More stringent than Q² or R²pred alone.- Can be calculated for overall fit (rm²(overall)) [2]. | - Less commonly used, no universal acceptance threshold.- Requires calculation beyond standard metrics. |

| CCC | External Validation (Predictivity) | Measures concordance between observed and predicted values [3]. | - Accounts for both precision and accuracy.- Recommended as a robust metric [3]. | - CCC > 0.8 is a common validity threshold [3]. |

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Standard Protocol for Q² LOO-CV

A robust internal validation requires a standardized protocol for calculating Q² LOO-CV:

- Dataset Curation: Assemble a high-quality dataset with experimentally measured activities and calculated molecular descriptors.

- Training Set Definition: The entire dataset used for model building is defined as the training set. No external test set is required for Q² LOO-CV.

- Iterative Modeling: For

i = 1ton(wherenis the number of compounds in the training set):- The

i-thcompound is temporarily removed from the dataset. - A model is built using the exact same modeling algorithm (e.g., MLR, PLS) and descriptor set on the remaining

n-1compounds. - The activity of the omitted

i-thcompound is predicted using this model.

- The

- Calculation: The PRESS is computed from all

npredictions, and Q² is derived using the standard formula.

Comparative Validation Study Design

To objectively compare Q² with other metrics, studies often follow this design:

- Data Splitting: The full data is split into a training set (e.g., 70-80%) for model building and internal validation, and a test set (e.g., 20-30%) for external validation [3].

- Model Development: Multiple models are developed using different algorithms (e.g., MLR, PLS, ANN) on the training set.

- Metric Calculation: For each model, R², Q² LOO-CV, and other internal metrics are calculated.

- External Validation: The models are used to predict the hold-out test set, and predictive R², CCC, and r²m are computed.

- Analysis: The correlation and consistency between internal (like Q²) and external validation parameters are analyzed. Studies often find that good internal validation does not guarantee high external predictivity, highlighting the need for multiple validation approaches [11] [2].

Critical Insights and Data-Driven Comparisons

Interdependence of Validation Metrics

Research reveals complex relationships between different validation metrics. A study investigating the relevance of OECD-QSAR principles found that goodness-of-fit (R²) and robustness (Q²) parameters can be highly correlated for linear models over a certain sample size, suggesting one might be redundant [11]. However, the same study noted that the relationship between internal and external validation parameters can be unpredictable, sometimes even showing negative correlations depending on how "good" and "bad" modelable data is assigned to the training or test set [11].

Performance in Different Modeling Contexts

The utility and interpretation of Q² can vary significantly depending on the modeling context:

- Model Type: While Q² LOO-CV and the related Leave-Many-Out (LMO) Q² can often be rescaled to each other, the feasibility of goodness-of-fit and robustness parameters can be questionable for complex, non-linear models like Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) and Support Vector Machines (SVR) [11]. These models can achieve a near-perfect fit to the training data (high R²), but their internal robustness metrics require careful interpretation.

- Dataset Balance and Objective: Traditional best practices emphasized balanced datasets and Balanced Accuracy. However, for virtual screening of ultra-large libraries, the goal is to identify a small number of active compounds. Recent studies suggest that models trained on imbalanced datasets, prioritized for high Positive Predictive Value (PPV), can achieve hit rates ~30% higher than models built on balanced data [13]. In such applications, while Q² remains important for robustness, PPV for the top-ranked predictions becomes a critical metric for success.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for QSAR Validation

The following table details key computational tools and their roles in the rigorous validation of QSAR models.

Table 2: Key Reagents & Tools for QSAR Validation

| Tool / Resource | Function in Validation | Relevance to Q² & Robustness |

|---|---|---|

| Cerius2 / GFA | Software platform for model development using techniques like Genetic Function Approximation [2]. | Provides algorithms to generate models for which Q² LOO-CV and other parameters can be calculated. |

| Dragon Software | Calculates a wide array of molecular descriptors (topological, structural, physicochemical) [3]. | Supplies the independent variables (X-matrix) for model building, forming the basis for any validation. |

| VEGA Platform | A freely available QSAR platform that often includes an assessment of the Applicability Domain (AD) [7]. | The AD is the 3rd OECD principle; predictions for compounds within the AD are more reliable, contextualizing Q². |

| EPI Suite | A widely used suite of predictive models for environmental fate and toxicity [7]. | Its models (e.g., BIOWIN) are often benchmarked, with performance assessed via validation metrics including cross-validation. |

| Stratified Sampling | A sampling method that maintains the distribution of classes (e.g., active/inactive) in each cross-validation fold [14]. | A best practice to ensure that Q² LOO-CV estimates are stable and representative when dealing with imbalanced data. |

Q² (LOO-CV Q²) remains a fundamental metric for assessing the internal robustness of QSAR models, directly addressing the OECD's validation principles. It provides a computationally efficient means to estimate model predictability, especially valuable when dataset size is limited. However, a single metric cannot provide a complete picture of a model's value. Robust QSAR validation is a multi-faceted process, and regulatory-grade model assessment requires a weight-of-evidence approach. This strategy integrates Q² with other critical metrics, including predictive R², r²m, and CCC for external predictivity, and a clear definition of the model's Applicability Domain. Furthermore, the choice of metrics must align with the model's intended use, as demonstrated by the shift towards PPV for virtual screening applications.

The Role of Predictive R² (R²pred) in External Validation and Assessing True Predictivity

In the field of Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling, the primary objective extends beyond merely explaining the biological activity of compounds within a training set; it aims to develop robust models capable of accurately predicting the activity of new, untested compounds. This predictive capability is crucial in drug discovery and development, where reliable in silico models can significantly reduce the time and cost associated with experimental screening. While internal validation techniques, such as cross-validation, provide initial estimates of model robustness, they often deliver overly optimistic assessments of a model's predictive power [8]. Consequently, external validation using an independent test set is widely regarded as the 'gold standard' for rigorously evaluating a model's true predictive capability [3] [8].

Among the various metrics employed for this purpose, the Predictive R² (R²pred) has been a subject of extensive discussion, application, and scrutiny. This metric, also denoted as q² for external validation, serves as a key indicator of how well a model might perform when applied to new data. However, its calculation and interpretation are not straightforward and have been sources of confusion within the scientific community [15] [8]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of R²pred, elucidates its proper application within a suite of validation metrics, and details experimental protocols for its computation, aiming to equip researchers with the knowledge to more accurately assess the predictive power of their QSAR models.

Theoretical Foundations: Demystifying R² and its Predictive Counterpart

The Coefficient of Determination (R²)

The standard R², or the coefficient of determination, is a fundamental metric that measures the proportion of variance in the dependent variable explained by the model relative to a simple mean model. It is calculated as [8]:

R² = 1 - (SSR / TSS)

Where:

- SSR (Sum of Squared Residuals) = Σ(y - ŷ)²

- TSS (Total Sum of Squares) = Σ(y - ȳ)²

In this context, y represents the observed activity, ŷ the predicted activity, and ȳ the mean of the observed activities. A critical limitation of R² is that it only measures the model's fit to the training data on which it was built and does not reflect its ability to generalize to new data [16].

The Predictive R² (R²pred)

The Predictive R² (R²pred) adapts this concept to evaluate performance on an external test set. The formula is analogous but applied strictly to compounds not used in model training [17]:

R²pred = 1 - (PRESS / TSStest)

Where:

- PRESS (Prediction Error Sum of Squares) = Σ(ytest - ŷtest)²

- TSStest = Σ(ytest - ȳtrain)²

A pivotal distinction lies in the calculation of the total sum of squares. For R²pred, TSStest uses ȳtrain (the mean activity of the training set), not ȳtest (the mean of the test set) [15] [17]. This is because the predictive capability is judged against the simplest possible model—one that always predicts the training set mean for any new compound [17]. Using ȳtest can introduce a systematic overestimation of predictive power, particularly when the training and test set means differ significantly [15].

Comparative Analysis of QSAR Validation Metrics

QSAR validation relies on a multi-faceted approach, employing a suite of metrics to assess different aspects of model quality. The table below summarizes the key metrics used in modern QSAR studies.

Table 1: Key Validation Metrics for QSAR Models

| Metric | Formula | Purpose | Interpretation | Key Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R² | 1 - (SSR / TSS) | Measure fit to training data. | Closer to 1.0 indicates better fit. | [8] |

| Adjusted R² | 1 - [(1-R²)(n-1)/(n-p-1)] | Fit to training data, penalized for number of predictors (p). | Mitigates overfitting; higher is better. | [16] |

| Q² (LOO-CV) | 1 - (PRESS_CV / TSS) | Estimate internal predictivity via Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation. | > 0.5 is generally acceptable. | [2] |

| R²pred | 1 - (PRESS / TSStest) | Quantify predictivity on an external test set. | > 0.6 is often considered predictive. | [15] [17] |

| rₘ² | r² × (1 - √(r² - r₀²)) | Stringent metric combining fit with and without intercept. | > 0.5 is recommended. | [2] |

| CCC | Formula (2) in [3] | Measure agreement between observed and predicted values. | > 0.8 indicates a valid model. | [3] |

Limitations and Misconceptions of R²pred

While invaluable, R²pred has specific limitations that researchers must acknowledge:

- Dependence on Training Set Mean: The metric's reliance on

ȳtrainmeans its value can be sensitive to the representativeness of the training set [15]. - Not a Standalone Metric: A high R²pred alone is not sufficient to prove model validity. Studies have shown that models can achieve high R²pred yet fail other, more stringent validation tests [3].

- Potential for Misuse: The multiplicity of definitions for R² in different software contexts (e.g., ordinary least squares vs. regression through origin) can lead to inconsistent calculations and misinterpretations if not carefully managed [18] [8].

The Rise of Stringent Complementary Metrics

Due to the limitations of traditional metrics, researchers have developed more robust parameters:

- The rₘ² Metric: This metric penalizes models for large differences between the squared correlation coefficient of regressions with (r²) and without (r₀²) an intercept. It provides a more stringent assessment of predictive potential than R²pred alone [2].

- Concordance Correlation Coefficient (CCC): The CCC evaluates both precision and accuracy by measuring how far the observations deviate from the line of perfect concordance (y=x). It is considered a highly reliable metric for external validation [3].

Table 2: Summary of Validation Criteria from Different Studies

| Study / Proposed Criteria | Key Parameters | Recommended Thresholds |

|---|---|---|

| Golbraikh & Tropsha [3] | R², slopes (k, k'), and differences (r² - r₀²) | R² > 0.6; 0.85 < k < 1.15; (r² - r₀²)/r² < 0.1 |

| Roy et al. (rₘ²) [2] | rₘ², Δrₘ² | rₘ² > 0.5; Δrₘ² < 0.1 |

| Gramatica et al. (CCC) [3] | Concordance Correlation Coefficient | CCC > 0.8 |

| Roy et al. (Range-Based) [3] | AAE (Absolute Average Error) & SD vs. Training Range | AAE ≤ 0.1 × range; AAE + 3×SD ≤ 0.2 × range |

Experimental Protocols for External Validation

A robust external validation workflow ensures that the calculated R²pred and other metrics are reliable indicators of a model's true predictive power.

Workflow for External Validation of QSAR Models

The following diagram outlines the standard protocol for model development and validation:

Detailed Methodological Steps

Data Curation and Preparation: Collect a dataset of compounds with experimentally determined biological activities. Calculate molecular descriptors using reliable software (e.g., Dragon). Preprocess the data by removing duplicates and addressing missing values.

Training-Test Set Division: Split the dataset into training and test sets. This can be done randomly for large datasets or via more strategic methods (e.g., Kennard-Stone, clustering) for smaller datasets to ensure the test set is representative of the chemical space and activity range of the training data [8]. A typical split is 70-80% for training and 20-30% for testing.

Model Development: Construct the QSAR model using only the training set data. Various statistical and machine learning methods can be employed, such as:

- Multiple Linear Regression (MLR)

- Partial Least Squares (PLS) Regression

- Artificial Neural Networks (ANN)

- Random Forest (RF)

Internal Validation: Perform internal validation on the training set using Leave-One-Out (LOO) or Leave-Many-Out (LMO) cross-validation to calculate Q². This provides an initial check of model robustness [2].

External Prediction and Metric Calculation: Apply the finalized model to the held-out test set to generate predictions. Use these predictions and the experimental values to calculate all relevant external validation metrics, as detailed in the following protocol.

Protocol for Calculating R²pred and Complementary Metrics

Inputs: Experimental activities (ytest) and model-predicted activities (ŷtest) for the test set; Training set mean activity (ȳ_train).

| Step | Operation | Formula / Code | Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Calculate PRESS | PRESS = Σ(y_test - ŷ_test)² |

Scalar value |

| 2 | Calculate TSStest | TSS_test = Σ(y_test - ȳ_train)² |

Scalar value |

| 3 | Compute R²pred | R²pred = 1 - (PRESS / TSS_test) |

Value between -∞ and 1 |

| 4 | Compute r² and r₀² | r²: correlation (ytest, ŷtest)²r₀²: from RTO | Two values |

| 5 | Compute rₘ² | rₘ² = r² * (1 - √(r² - r₀²)) |

Value between 0 and 1 |

| 6 | Compute CCC | See formula (2) in [3] | Value between -1 and 1 |

Note: RTO = Regression Through Origin. There are different opinions on the correct calculation of r₀², which can lead to software-dependent variations [3] [18].

Table 3: Key Software and Resources for QSAR Validation

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in Validation | Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dragon Software | Descriptor Calculator | Calculates thousands of molecular descriptors from chemical structures. | Foundational for model building. |

| Cerius2 | Modeling Software | Integrated platform for QSAR model development and internal validation. | Includes GFA and other algorithms [2]. |

| SPSS / R / Python | Statistical Analysis | Calculate R², R²pred, CCC, and other statistical parameters. | Be aware of algorithm differences for RTO [18]. |

| SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) | Explainable AI | Provides post-hoc interpretability for complex ML models. | Critical for understanding model decisions [19]. |

The Predictive R² (R²pred) remains an essential metric in the toolbox of QSAR researchers, providing a direct measure of a model's performance on an independent test set. However, the evolving consensus in the field clearly indicates that no single metric is sufficient to establish the predictive validity of a QSAR model [3] [20]. Reliance on R²pred alone can be misleading. A robust validation strategy must incorporate a suite of complementary metrics, including but not limited to rₘ² and CCC, and adhere to strict protocols for data splitting and model application. As computational methods advance and models become more complex, the principles of rigorous, multi-faceted validation will only grow in importance for the successful and reliable application of QSAR in drug discovery and environmental risk assessment.

Why All Three? The Interplay and Differences Between Q², R², and Predictive R²

In the field of Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling, a statistically significant model is the cornerstone for reliable predictions in drug discovery and development [3] [21]. However, a model's journey from development to deployment relies on rigorous validation to confirm its robustness and predictive power. Within this process, three critical metrics often come to the forefront: R², Predictive R², and Q² [3] [22]. While they may appear similar, each provides a distinct lens through which to assess a model's performance. R² evaluates the model's fit to the data it was trained on, while Predictive R² and Q² offer insights into its ability to generalize to new, unseen data [16] [22]. This guide objectively compares these three validation metrics, detailing their calculations, interpretations, and roles in building trustworthy QSAR models for researchers and drug development professionals.

Defining the Metrics: Core Concepts and Calculations

R² (Coefficient of Determination)

R², known as the coefficient of determination, is a fundamental metric for assessing the goodness-of-fit of a model to its training data [16] [23]. It quantifies the proportion of variance in the dependent variable (e.g., biological activity) that is explained by the model's independent variables (e.g., molecular descriptors) [24].

- Formula: R² is calculated as: ( R^2 = 1 - \frac{RSS}{TSS} ) Where:

- Interpretation: An R² value of 1 indicates a perfect fit, meaning the model explains all the variance in the training data. A value of 0 means the model explains none of the variance [16] [23]. It's important to note that R² is inflatory; it can artificially increase as more predictors are added to a model, which can lead to overfitting [22].

Predictive R²

Predictive R² (sometimes denoted as ( R²{pred} ) or ( Q^2{F1} )) is the most straightforward metric for evaluating a model's performance on an external test set [8] [25]. This test set consists of compounds that were not used in any part of the model building process, providing an unbiased estimate of how the model will perform on new data [8].

- Formula: Its calculation mirrors that of R² but uses the external test data:

( R^2{pred} = 1 - \frac{PRESS{ext}}{TSS{ext}} )

Where:

- PRESS (Prediction Error Sum of Squares) = (\sum (y - ŷ{ext})²) (the sum of squared prediction errors for the external test set) [17] [22].

- TSS{ext} is typically calculated using the mean of the training set ((\bar{y}{training})) as the reference point, maintaining the comparison to the naïve model built during training [17].

Q² (Cross-Validated R²)

Q² typically refers to the cross-validated R², which is a measure of a model's internal predictive ability and robustness [22] [25]. It is estimated through procedures like leave-one-out (LOO) or leave-many-out cross-validation, where parts of the training data are repeatedly held out as a temporary validation set [8].

- Formula: The most common form is: ( Q^2 = 1 - \frac{PRESS{CV}}{TSS{training}} ) Where:

- Interpretation: Like R², Q² ranges from 0 to 1 in theory, with higher values indicating better predictive robustness. However, cross-validation methods can sometimes provide overly optimistic estimates of a model's predictive power for truly external data [8].

Table 1: Core Definitions and Characteristics of the Validation Metrics

| Metric | Full Name | Primary Data Set | Core Question it Answers | Key Characteristic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R² | Coefficient of Determination | Training Set | How well does the model fit the data it was built on? | Goodness-of-fit; can be inflatory with more parameters [22]. |

| Q² | Cross-validated R² | Training Set (via CV) | How well can the model predict data it was not trained on, internally? | Measure of internal predictive ability and robustness [25]. |

| Predictive R² | Predictive R² | External Test Set | How well will the model predict on entirely new, unseen compounds? | Unbiased estimate of external predictivity; the "gold standard" [8]. |

A Comparative Analysis: Validation in Practice

Direct Metric Comparison

Understanding the nuanced differences between these metrics is crucial for proper model validation.

- Purpose and Philosophy: R² is a diagnostic measure of fit, looking backward at the data used to create the model. In contrast, Q² and Predictive R² are prospective measures of prediction, looking forward to new data. Predictive R² is considered the gold standard for assessing real-world predictive power because it uses a fully independent test set [8].

- Calculation and Denominator: A key technical difference lies in the calculation of the TSS denominator for Q². While often calculated using the training set mean ((\bar{y}{training})), a more statistically rigorous approach for LOO Q² involves calculating a unique TSS for each left-out compound using the mean of the remaining training compounds ((\bar{y}{-i})) [17]. Despite this nuance, for model selection purposes, the ranking of models based on PRESS is equivalent regardless of which TSS denominator is used [17].

- Performance and Interpretation: A high R² does not guarantee a high Predictive R². In fact, an overly complex model might have a high R² but a low Predictive R², a classic sign of overfitting [16] [8]. Q² often falls between R² and Predictive R² in value. It is possible for Q² to be higher than R² in some cases, which generally indicates a robust model [17]. According to the Golbraikh and Tropsha criteria, a reliable QSAR model should have R² > 0.6 and Q² > 0.5, among other parameters [3].

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Metric Performance and Interpretation

| Aspect | R² | Q² (LOO-CV) | Predictive R² |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Role | Evaluate model fit to training data. | Estimate internal robustness and predictivity. | Evaluate true external predictivity. |

| Value Trend | Inflationary; increases with model complexity. | Not inflationary; peaks at optimal complexity [22]. | Can decrease with overfitting. |

| Strengths | Simple to calculate and interpret. | Does not require a separate test set; useful for small datasets. | Provides the most honest estimate of real-world performance [16]. |

| Weaknesses | Does not measure predictive ability; can be misleading [3] [8]. | Can be overly optimistic; not a true test of external prediction [8]. | Requires a dedicated, external test set, reducing data for training. |

When to Use Each Metric

The three metrics are not mutually exclusive but are used in different stages of the model development and validation workflow.

- R² is most useful during the model building phase to get an initial sense of how well the chosen descriptors and algorithm capture the relationship in the available data.

- Q² is applied during the model selection and internal validation phase. It helps in tuning model parameters and selecting the optimal model complexity to avoid overfitting, especially when data is limited and a hold-out test set is not feasible.

- Predictive R² is the cornerstone of the final model validation phase. Before a model is deployed or published, its predictive power must be confirmed using a true external test set that was never used in training or model selection [8] [25].

Experimental Protocols for Metric Evaluation

For researchers to accurately compute and report these metrics, a standardized experimental protocol is essential.

Workflow for QSAR Model Validation

A robust validation workflow ensures that the model's performance is assessed without bias. The following diagram illustrates the key stages and where each metric is applied:

Detailed Methodologies

Calculating R² from the Training Set

- Model Fitting: Develop the QSAR model (e.g., using Partial Least Squares regression) using the entire training set.

- Generate Predictions: Use the fitted model to predict the activities ((ŷ)) of the training set compounds.

- Compute RSS: Calculate the Residual Sum of Squares: (RSS =\sum(y{training}-ŷ{training})^2) [17] [22].

- Compute TSS: Calculate the Total Sum of Squares using the mean of the training set: (TSS = \sum(y{training}-\bar{y}{training})^2) [17] [22].

- Calculate R²: Apply the formula: ( R^2 = 1 - RSS/TSS ) [17].

Calculating Q² via Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation (LOO-CV)

- Iteration: For each compound

iin the training set ofncompounds:- Temporarily remove compound

i. - Fit the model using the remaining

n-1compounds. - Use this model to predict the activity of the held-out compound

i((ŷ_{ext,i})).

- Temporarily remove compound

- Compute PRESSCV: After processing all compounds, calculate the PRESS: (PRESS{CV} = \sum{i=1}^n (yi - ŷ_{ext,i})^2) [22].

- Compute TSS_training: This is the TSS of the full training set, as defined in 4.2.1.

- Calculate Q²: Apply the formula: ( Q^2 = 1 - \frac{PRESS{CV}}{TSS{training}} ) [22].

Calculating Predictive R² from an External Test Set

- Predict Test Set: Apply the final model (trained on the entire training set) to predict the activities of the external test set compounds ((ŷ_{test})).

- Compute PRESSext: Calculate the PRESS for the test set: (PRESS{ext} = \sum (y{test} - ŷ{test})^2) [17] [22].

- Compute TSSext: There is a debate here. The most consistent practice is to use the mean of the training set ((\bar{y}{training})) to calculate TSS for the test set: (TSS{ext} = \sum (y{test} - \bar{y}_{training})^2). This evaluates the model against the naïve baseline established during training [17].

- Calculate Predictive R²: Apply the formula: ( R^2{pred} = 1 - \frac{PRESS{ext}}{TSS_{ext}} ) [22].

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for QSAR Model Validation

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in Validation | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dragon Software | Descriptor Calculation | Generates a wide array of molecular descriptors from chemical structures to be used as model predictors [3]. | Calculating topological, geometrical, and constitutional descriptors for a library of compounds. |

| PLS Regression | Statistical Algorithm | A core multivariate technique used to develop QSAR models, especially when the number of descriptors exceeds the number of compounds [22]. | Building a model that correlates molecular descriptors to biological activity (pIC50). |

| Cross-Validation | Statistical Protocol | A resampling method used to estimate Q² and assess model robustness without an external test set [8] [25]. | Performing Leave-One-Out CV to tune the number of components in a PLS model. |

| Applicability Domain (AD) | Validation Framework | Defines the chemical space where the model's predictions are considered reliable, addressing OECD Principle 3 [25]. | Filtering out new compounds for prediction that are structurally dissimilar to the training set, increasing prediction confidence. |

| rm² Metrics | Validation Metric | A group of stringent metrics that combine traditional R² with regression-through-origin analysis to better screen predictive models [3] [18]. | Comparing two candidate models with similar R² and Q² values to select the one with superior predictive consistency. |

In the rigorous world of QSAR modeling, the question is not which metric to use, but why all three are necessary. R², Q², and Predictive R² offer a synergistic suite of assessments that, together, provide a complete picture of a model's journey from a good fit to a powerful predictive tool. R² confirms the model learned from its training, Q² checks its internal consistency and robustness, and Predictive R² ultimately certifies its utility for real-world decision-making in drug discovery. Relying on any one in isolation, particularly R² alone, can be misleading and risks deploying a model that fails on new chemical matter [3] [8]. A robust validation strategy that integrates all three metrics, alongside adherence to OECD principles and a defined Applicability Domain, is therefore indispensable for building QSAR models that researchers can trust to guide the design of new, effective compounds.

In the field of Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling, the coefficient of determination, R², is one of the most frequently cited statistics for evaluating model quality. A high R² value is traditionally interpreted as indicating a good model fit, leading to a common misconception that it invariably translates to high predictive accuracy. However, this interpretation can be dangerously misleading. An overreliance on R² without understanding its limitations often masks the problem of overfitting, where a model demonstrates excellent performance on training data but fails to predict new, unseen compounds accurately [26] [8]. This article dissects the pitfalls of misusing R² and contrasts it with robust validation metrics essential for developing reliable, predictive QSAR models suitable for regulatory decision-making and drug discovery.

Understanding R² and Its Inherent Limitations

What R² Really Measures

The coefficient of determination, R², is defined as the proportion of variance in the dependent variable that is explained by the model [16]. It is calculated as:

R² = 1 - (SSR / SST)

Where SSR is the sum of squared residuals (the difference between observed and predicted values) and SST is the total sum of squares (the difference between observed values and their mean) [8]. While this provides a useful measure of goodness-of-fit, it is calculated exclusively on the training data used to build the model and does not inherently measure the model's ability to generalize.

Why R² is a Misleading Indicator of Predictive Power

The common intuition that higher R² signifies a better model is seriously faulty [26]. Several key limitations contribute to this:

- R² Can Be Artificially Inflated: Adding more predictor variables to a model, even irrelevant ones, will never decrease the R² value. This creates a false sense of improvement as model complexity increases, inevitably leading to overfitting [26] [16].

- Lack of Penalty for Complexity: Standard R² does not account for the number of predictors used in the model. A model with numerous descriptors might achieve a high R² by memorizing noise in the training data rather than capturing the true underlying relationship [8].

- Sensitivity to Data Variability: R² is a measure of variance explanation. By reducing the variability in the dataset (e.g., through aggregation), one can achieve a higher R² even with a worse model, as there is "less to explain" [26].

The Critical Transition from Explanation to Prediction

The Overfitting Paradigm in QSAR

Overfitting occurs when a model is excessively complex, learning not only the underlying relationship in the data but also the random noise. In QSAR, this is a significant risk due to the high dimensionality of descriptor spaces. A model may appear perfect on paper with an R² > 0.9, yet perform poorly when predicting the activity of novel chemical structures [8]. This is because the model has been tailored too specifically to the training set and lacks robustness and generalizability.

Case Study: The Illusion of Improvement

A compelling example from the literature demonstrates how adding an uninformative variable can deceive researchers. When a randomly generated variable with no real relationship to the response was added to a model with an initial R² of 0.5, the R² increased to 0.568, creating the illusion of an improved model [26]. In reality, the model's predictive power on new data would likely decrease due to the inclusion of this spurious variable.

Table 1: Impact of Adding Variables on R² and Model Quality

| Scenario | Model Variables | R² | True Predictive Power |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Model | Meaningful Descriptors | 0.50 | Moderate |

| Deceptive Model | Meaningful Descriptors + Random Noise | 0.57 | Lower (Overfit) |

| Overfit Model | Right-leg-length to predict Left-leg-length | 0.996 | None (Nonsensical) |

Beyond R²: A Framework of Robust Validation Metrics for QSAR

Internal Validation: Cross-Validation Techniques

Internal validation methods assess model stability using only the training set data.

- Leave-One-Out (LOO) Cross-Validation: This involves repeatedly building models with one compound left out and predicting its activity. The cross-validated R² (denoted as Q²) is then calculated from these predictions [8] [2]. While useful, Q² can still provide overly optimistic estimates of predictive power [8] [27].

- Double Cross-Validation: Also known as nested cross-validation, this method uses two layers of cross-validation. The inner loop performs model selection, while the outer loop provides a nearly unbiased estimate of the prediction error, making it more reliable than single-level cross-validation under model uncertainty [27].

External Validation: The True Test of Predictivity

External validation is considered the 'gold standard' for assessing a model's predictive power [8] [27]. This involves:

- Training-Test Set Split: The available data is divided into a training set for model development and a completely held-out test set for final evaluation [25] [8].

- Predictive R² (R²ₚᵣₑd): This is calculated on the external test set and provides an honest estimate of how the model will perform on new data [2] [16]. Unlike the fitted R², R²ₚᵣₑd can be negative, indicating that the model performs worse than simply predicting the mean [8].

Novel and Complementary Validation Parameters

To address the shortcomings of traditional metrics, researchers have developed stricter validation parameters:

- rm² Metrics: The rm² parameter (and its variants: rm²(LOO), rm²(test), rm²(overall)) provides a more stringent test than Q² and R²ₚᵣₑd by penalizing models for large differences between observed and predicted values [2]. It is based on the correlation between observed and predicted values, with a threshold of rm² > 0.5 suggested for acceptable models.

- Rp² for Randomization Tests: The Rp² metric penalizes the model R² based on the difference between the squared correlation coefficient of the non-random model and the average squared correlation coefficient of models built with randomized response values. This helps guard against chance correlations [2].

Table 2: Comparison of Key QSAR Validation Metrics

| Metric | Calculation Basis | Purpose | Acceptance Threshold | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R² | Training Set | Goodness-of-fit | Context-dependent | Measures variance explained; easy to compute |

| Q² (LOO) | Training Set (Cross-Validation) | Internal Robustness | > 0.5 | More conservative than R²; assesses stability |

| R²ₚᵣₑd | External Test Set | External Predictivity | > 0.6 | Honest estimate of performance on new data |

| rm² | Training/Test/Overall Set | Predictive Consistency | > 0.5 | Stricter than R²ₚᵣₑd; penalizes large errors |

| Rp² | Randomization Test | Significance Testing | > 0.5 | Guards against chance correlation |

Experimental Protocols for Reliable QSAR Validation

The OECD Principles: A Regulatory Framework

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has established five principles for validating QSAR models for regulatory use [25]:

- A defined endpoint

- An unambiguous algorithm

- A defined domain of applicability

- Appropriate measures of goodness-of-fit, robustness, and predictivity

- A mechanistic interpretation, if possible

Principle 4 explicitly calls for the use of both internal (goodness-of-fit, robustness) and external (predictivity) validation measures, moving beyond a sole reliance on R² [25].

Workflow for Robust QSAR Model Development and Validation

The following diagram illustrates a rigorous experimental protocol that incorporates double cross-validation and external testing to minimize overfitting and reliably estimate predictive power.

Diagram Title: QSAR Model Validation with Double Cross-Validation

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for QSAR Validation

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Cerius2 / MOE | Software Platform | Calculates molecular descriptors and enables model building with GFA. |

| Genetic Function Approximation (GFA) | Algorithm | Generates multiple QSAR models with variable selection, helping to avoid overfitting. |

| Double Cross-Validation Script | Computational Protocol | Provides nearly unbiased estimate of prediction error under model uncertainty [27]. |

| Applicability Domain (AD) Tool | Statistical Method | Defines the chemical space where the model's predictions are reliable, a key OECD principle [25]. |

| Randomization Test Script | Statistical Test | Generates models with randomized response to calculate Rp² and test for chance correlation [2]. |

A high R² value in a QSAR model should be viewed not as a final stamp of approval, but as a starting point for more rigorous investigation. As demonstrated, an overreliance on this single metric is a critical pitfall that can hide an overfit model with poor generalization ability. The path to robust and predictive QSAR models lies in adhering to the OECD principles and employing a comprehensive validation strategy that combines internal validation (e.g., Q²), external validation (R²ₚᵣₑd), and novel metrics (rm², Rp²) within a framework that includes double cross-validation and a clear definition of the model's applicability domain. By moving beyond R², researchers can build models that are not just statistically elegant but truly predictive, thereby accelerating reliable drug discovery and safety assessment.

Applying Validation Metrics: A Step-by-Step QSAR Workflow

The Standard QSAR Modeling and Validation Workflow

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling represents a cornerstone computational approach in modern drug discovery and environmental chemistry. These mathematical models link chemical compound structures to their biological activities or physicochemical properties, enabling researchers to prioritize promising drug candidates, reduce animal testing, and guide structural optimization [28]. The reliability of any QSAR model hinges entirely on a rigorous, standardized workflow for model development and—most critically—validation. Within this framework, validation metrics such as R² and Q² serve as essential indicators of model performance, distinguishing between mere mathematical fitting and genuine predictive power [22]. This guide details the standard QSAR modeling and validation workflow, with a focused comparison of the methodologies and metrics that underpin predictive, trustworthy models.

Foundational Concepts of QSAR Modeling

At its core, QSAR modeling operates on the principle that molecular structure variations systematically influence biological activity or chemical properties. Models transform chemical structures into numerical vectors known as molecular descriptors, which quantify structural, physicochemical, or electronic properties [28]. The fundamental relationship can be expressed as:

Biological Activity = f(Molecular Descriptors) + ϵ

where f is a mathematical function and ϵ represents the unexplained error [28]. Models are broadly categorized as linear (e.g., Multiple Linear Regression (MLR), Partial Least Squares (PLS)) or non-linear (e.g., Support Vector Machines (SVM), Neural Networks (NN)), with the choice depending on the relationship complexity and dataset characteristics [28].

The Standard QSAR Workflow: A Step-by-Step Analysis

A robust QSAR modeling workflow integrates sequential phases from data preparation to model deployment. The diagram below illustrates the standard workflow and the role of validation metrics at each stage.

Step 1: Data Preparation and Curation

The foundation of any reliable QSAR model is a high-quality, well-curated dataset. This initial stage involves compiling chemical structures and their associated biological activities from reliable sources such as literature, patents, or databases like ChEMBL [28] [29]. Key steps include:

- Data Cleaning: Removing duplicate, ambiguous, or erroneous entries.

- Structure Standardization: Normalizing chemical representations by removing salts, handling tautomers, and standardizing stereochemistry [28].

- Activity Data Standardization: Converting all biological activities to a common unit and scale (e.g., log-transform) [28].

- Dataset Division: Splitting the cleaned data into a training set for model development and a hold-out external test set for final model validation. The test set must remain completely independent of the training process to provide an unbiased performance estimate [28].

Step 2: Molecular Descriptor Calculation and Feature Selection

Molecular descriptors are numerical representations of a molecule's structural and physicochemical properties. Hundreds to thousands of descriptors can be calculated using software tools like PaDEL-Descriptor, Dragon, or RDKit [28]. Feature selection is then critical to identify the most relevant descriptors, reduce overfitting, and improve model interpretability. Common methods include:

- Filter Methods: Ranking descriptors based on individual correlation with the activity.

- Wrapper Methods: Using the modeling algorithm to evaluate descriptor subsets.

- Embedded Methods: Performing feature selection during model training (e.g., LASSO regression) [28].

Step 3: Model Building and Internal Validation

With the prepared training set, predictive algorithms are applied. The model's initial performance is assessed via internal validation using the training data. The most common technique is cross-validation (e.g., k-fold or leave-one-out), which yields the Q² (or Q²ₑᵥₐₗ) metric [22]. Q² estimates the model's ability to predict new data within the same chemical space used for training. It is calculated as 1 - PRESS/TSS, where PRESS is the Predictive Error Sum of Squares from cross-validation [22].

Step 4: External Validation and Predictive Power Assessment

This is the most critical step for evaluating real-world predictive ability. The final model is used to predict the held-out external test set, yielding the predictive R² (R²ₑₓₜ) [28] [22]. A high R²ₑₓₜ demonstrates that the model can generalize to truly unseen compounds. It is calculated as 1 - RSSₑₓₜ/TSSₑₓₜ, where RSSₑₓₜ is the Residual Sum of Squares for the test set predictions.

Step 5: Defining the Applicability Domain (AD)

No QSAR model is universally applicable. The Applicability Domain defines the chemical space within which the model's predictions are reliable [7]. Predictions for compounds structurally dissimilar to the training set are considered less reliable. Assessing the AD is a mandatory step before using a model for screening new compounds [7].

Comparative Analysis of QSAR Validation Metrics

The predictive confidence of a QSAR model is quantified using a suite of metrics. The table below provides a structured comparison of the core validation metrics, with particular emphasis on Q² and R².

Table 1: Key Metrics for QSAR Model Validation and Interpretation

| Metric Name | Formula | Optimal Value | Primary Function | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R² (Goodness-of-Fit) | ( R^2 = 1 - \frac{RSS}{TSS} ) [30] | Closer to 1.0 | Measures how well the model fits the training data [22]. | Simple to calculate and interpret. | Inflationary; increases with added features, risking overfitting [22]. |

| Q² (Goodness-of-Prediction) | ( Q^2 = 1 - \frac{PRESS}{TSS} ) [22] | > 0.5 (Generally) | Estimates internal predictive ability via cross-validation [22]. | More robust estimate of generalizability than R². | Can be optimistic; still based on resampling the training set. |

| Predictive R² (R²ₑₓₜ) | ( R^2{ext} = 1 - \frac{RSS{ext}}{TSS_{ext}} ) | > 0.6 (Generally) | Measures true predictive power on a held-out external test set [28]. | Gold standard for assessing real-world performance. | Requires a dedicated, representative test set that is never used in training. |

| RMSE (Root Mean Square Error) | ( RMSE = \sqrt{\frac{1}{N} \sum (yi - \hat{y}i)^2} ) [30] | Closer to 0 | Measures average prediction error, on the same scale as the target variable [30]. | Easy to understand (e.g., "average error in pIC₅₀ units"). Penalizes large errors. Sensitive to outliers [30]. | |

| MAE (Mean Absolute Error) | ( MAE = \frac{1}{N} \sum |yi - \hat{y}i| ) [30] | Closer to 0 | Measures average prediction error magnitude [30]. | Robust to outliers. Easy to interpret. | Does not penalize large errors as severely as RMSE. |

The relationship between these metrics during model development is crucial for diagnosing model quality. The following diagram illustrates the decision-making process based on their values.

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation

Protocol 1: Internal Validation via Cross-Validation

- Divide Training Set: Split the training data into k subsets (folds). A common k is 5 or 10 [28].

- Iterate Training: For each fold i, train the model on the remaining k-1 folds.

- Generate Predictions: Use the resulting model to predict the activities of compounds in fold i. This generates a set of cross-validated predictions for the entire training set.

- Calculate Q²: Compute the PRESS from the cross-validated predictions and use it to calculate Q² [22]. A Q² > 0.5 is generally considered acceptable.

Protocol 2: External Validation with a Test Set

- Hold Out Data: Before model building, randomly set aside a portion (typically 20-30%) of the dataset as the external test set. Do not use this set for feature selection or parameter tuning [28].

- Build Final Model: Train the final model using the entire training set and the selected features/parameters.

- Predict and Calculate: Use the final model to predict the activities of the external test set compounds. Calculate the predictive R² (R²ₑₓₜ) and RMSE using these predictions versus the actual values [28] [30]. A predictive R² > 0.6 is a common benchmark for a model with good external predictive ability.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Software

Table 2: Key Software Tools for QSAR Modeling and Validation

| Tool Name | Type/Category | Primary Function in QSAR Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| PaDEL-Descriptor [28] | Descriptor Calculation Software | Calculates a wide array of molecular descriptors and fingerprints from chemical structures. |

| RDKit [28] | Cheminformatics Toolkit | An open-source toolkit for cheminformatics, used for descriptor calculation, fingerprinting, and molecular operations. |

| VEGA [7] | Integrated QSAR Platform | A platform hosting multiple validated (Q)SAR models, particularly useful for regulatory endpoints like toxicity and environmental fate. |

| EPI Suite [7] | Predictive Suite | A widely used suite of physical/chemical and environmental assessment models (e.g., KOWWIN, BIOWIN). |

| Danish QSAR Model [7] | (Q)SAR Model Database | Provides access to multiple individual QSAR models, such as the Leadscope model for persistence prediction. |

| ADMETLab 3.0 [7] | Online Prediction Platform | A web-based platform for predicting ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, Toxicity) properties. |

| SYNTHIA [31] | Retrosynthesis Software | Used for designing synthetic routes for novel compounds identified via QSAR models. |

The standard QSAR modeling and validation workflow is a disciplined, iterative process. The distinction between R² (goodness-of-fit), Q² (internal predictability), and predictive R² (external generalizability) is non-negotiable for rigorous model assessment. A high R² alone is a warning sign of potential overfitting, not a guarantee of predictive power. The most reliable models are those validated by a high Q² and, crucially, a high predictive R² on a truly external test set. As the field advances with increased AI and deep learning integration, the principles of this standardized workflow—especially robust external validation and clear definition of the applicability domain—remain the bedrock of generating trustworthy, scientifically valid, and regulatory-ready QSAR models.