qPCR vs. dPCR: A Strategic Guide to Maximizing Biomarker Accuracy in Research and Diagnostics

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of quantitative PCR (qPCR) and digital PCR (dPCR) platforms for biomarker analysis, addressing the critical needs of researchers and drug development professionals.

qPCR vs. dPCR: A Strategic Guide to Maximizing Biomarker Accuracy in Research and Diagnostics

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of quantitative PCR (qPCR) and digital PCR (dPCR) platforms for biomarker analysis, addressing the critical needs of researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of both technologies, details methodological applications across key areas like oncology and infectious diseases, and offers practical troubleshooting and optimization strategies. A central focus is the validation and comparative analysis of platform performance in terms of sensitivity, precision, and suitability for specific biomarker tasks, such as detecting rare variants or achieving absolute quantification. The goal is to equip scientists with the knowledge to select the optimal PCR platform to enhance the accuracy, reliability, and impact of their biomarker data.

Understanding the Core Technologies: From qPCR Fundamentals to dPCR Partitioning

The invention of the Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) in 1983 by Kary Mullis marked a revolutionary moment in molecular biology, providing an elegant method to exponentially amplify specific DNA sequences from minimal starting material [1] [2]. This foundational technology enabled unprecedented advances in genetic research, forensics, and diagnostics, earning Mullis the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1993 [2]. While conventional PCR demonstrated remarkable capabilities for DNA amplification, it remained largely qualitative, relying on endpoint detection methods like gel electrophoresis that offered limited quantitative information [2].

The evolution toward quantification began with the development of real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) in the early 1990s, which introduced the ability to monitor DNA amplification as it occurred [1]. This breakthrough was further refined through probe-based detection systems like TaqMan probes, introduced in 1996, which significantly improved specificity by using fluorescent reporter dyes quenched in close proximity until degraded during amplification [2]. The advent of digital PCR (dPCR) in the late 1990s, facilitated by microfluidics, represented the next evolutionary leap by enabling absolute nucleic acid quantification without standard curves through sample partitioning into thousands of individual reactions [1] [3]. This technological progression from conventional to qPCR and dPCR has fundamentally transformed molecular diagnostics, biomarker discovery, and precision medicine, providing researchers with increasingly sophisticated tools for nucleic acid quantification.

Technological Principles and Methodologies

Fundamental Workflows and Detection Mechanisms

The core principles distinguishing qPCR and dPCR stem from their fundamentally different approaches to quantification. qPCR operates through kinetic fluorescence monitoring during thermal cycling, where the accumulation of amplified DNA products is tracked in real-time using either intercalating dyes or sequence-specific fluorescent probes [2] [4]. The critical measurement in qPCR is the threshold cycle (Ct), which represents the PCR cycle number at which the fluorescence signal exceeds a predetermined threshold above background levels [4]. This Ct value exhibits an inverse logarithmic relationship with the initial template concentration, enabling relative quantification through comparison with standard curves of known concentrations [4].

In contrast, dPCR employs a partitioning-based absolute quantification approach, where the reaction mixture is divided into thousands to millions of separate compartments prior to amplification [4] [3]. Following endpoint PCR amplification, each partition is analyzed as either positive (containing the target sequence) or negative (lacking the target). The absolute concentration of the target nucleic acid is then calculated using Poisson statistical analysis based on the ratio of positive to total partitions, completely eliminating the need for standard curves [4] [3].

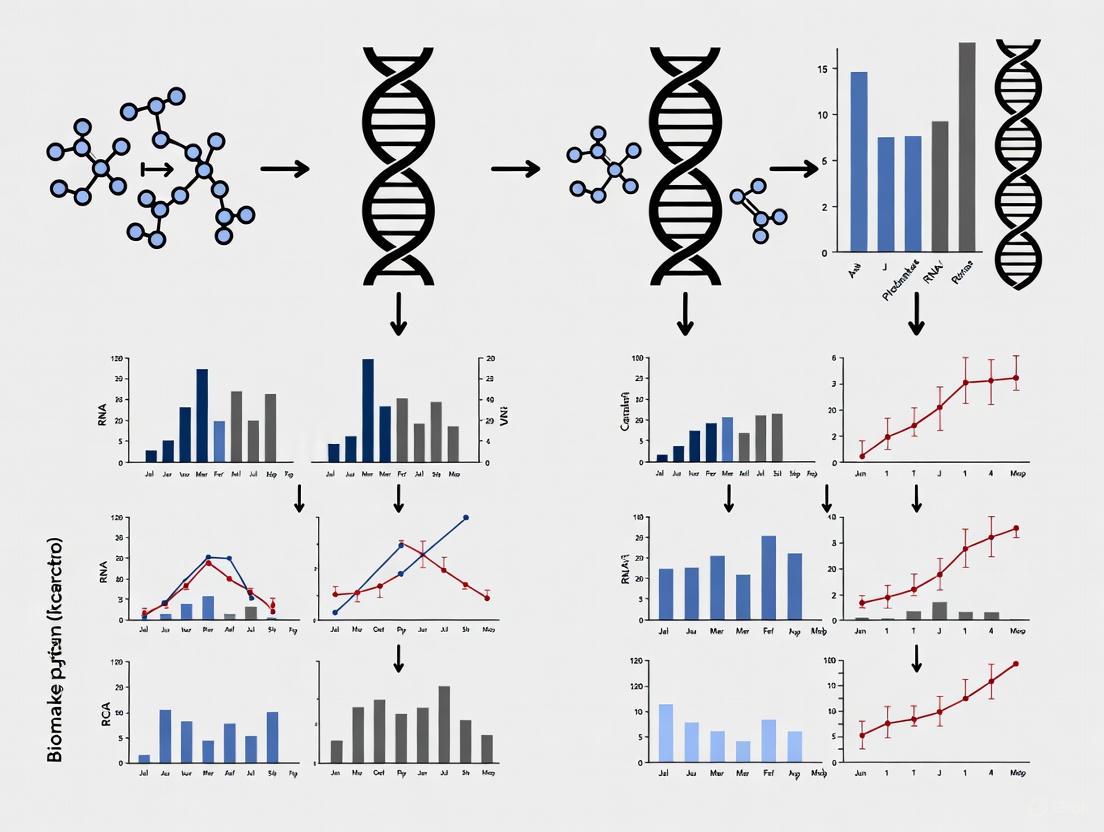

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental procedural differences between these two quantification approaches:

Experimental Protocol for Comparative Performance Analysis

Recent studies have directly compared the performance characteristics of qPCR and dPCR using standardized experimental protocols. A 2025 investigation evaluating respiratory virus detection during the 2023-2024 "tripledemic" provides a representative methodology for such comparative analyses [5].

Sample Preparation:

- Collect 123 respiratory samples (122 nasopharyngeal swabs, 1 bronchoalveolar lavage) from symptomatic patients

- Stratify samples based on qPCR cycle threshold (Ct) values: high (≤25), medium (25.1-30), and low (>30) viral loads [5]

- Extract nucleic acids using automated systems (e.g., KingFisher Flex with MagMax Viral/Pathogen kit)

qPCR Protocol:

- Utilize multiplex Real-Time RT-PCR with commercial respiratory panel kits

- Perform amplification on standard thermocyclers with fluorescent signal detection

- Include internal controls to monitor extraction and amplification efficiency [5]

dPCR Protocol:

- Employ nanowell-based dPCR systems with five-target multiplex capability

- Partition samples into approximately 26,000 individual reactions

- Conduct endpoint PCR amplification followed by fluorescent signal detection and absolute quantification [5]

Data Analysis:

- Compare quantification consistency and precision across viral load categories

- Assess performance in co-infection scenarios with multiple viral targets

- Evaluate statistical significance using appropriate measures (e.g., Kruskal-Wallis tests) [5]

Comparative Performance Analysis

Technical Parameter Comparison

The distinctive methodologies of qPCR and dPCR result in significantly different performance characteristics that determine their suitability for specific applications. The table below summarizes key technical parameters based on recent comparative studies:

Table 1: Technical comparison between qPCR and dPCR

| Parameter | qPCR | dPCR |

|---|---|---|

| Quantification Method | Relative (based on standard curves) | Absolute (counting of molecules) |

| Precision | Good, but susceptible to inhibitor effects and amplification efficiency variations | Superior, particularly for low-abundance targets and rare mutation detection |

| Dynamic Range | Broader (up to 7-8 orders of magnitude) | Limited by partition count (typically 4-5 orders of magnitude) |

| Throughput | Higher (real-time monitoring, 96-well formats) | Lower (requires partitioning and post-PCR analysis) |

| Sample Volume | Accommodates larger volumes | Limited by partition capacity |

| Cost Considerations | Lower per-test cost, established infrastructure | Higher consumable costs, specialized equipment |

| Optimal Application Scope | High-throughput screening, routine diagnostics, gene expression profiling | Absolute quantification, rare variant detection, copy number variation, complex samples |

Experimental Performance Data in Respiratory Virus Detection

Recent research directly comparing qPCR and dPCR performance in clinical applications provides quantitative insights into their respective capabilities. A 2025 study analyzing respiratory virus detection during the 2023-2024 tripledemic yielded the following comparative results:

Table 2: Performance comparison in respiratory virus detection across viral load categories

| Virus | Viral Load Category | qPCR Performance | dPCR Performance | Superior Platform |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Influenza A | High (Ct ≤25) | Moderate consistency | Excellent accuracy and precision | dPCR |

| Influenza B | High (Ct ≤25) | Moderate consistency | Excellent accuracy and precision | dPCR |

| SARS-CoV-2 | High (Ct ≤25) | Moderate consistency | Excellent accuracy and precision | dPCR |

| RSV | Medium (Ct 25.1-30) | Variable quantification | Superior consistency and precision | dPCR |

| All Viruses | Low (Ct >30) | Acceptable detection | Improved sensitivity | Comparable |

This study demonstrated that dPCR provided superior accuracy for high viral loads of influenza A, influenza B, and SARS-CoV-2, along with better performance for medium viral loads of RSV [5]. The consistency and precision advantages of dPCR were particularly notable when quantifying intermediate viral levels, highlighting its value for applications requiring precise quantification across varying concentration ranges.

Biomarker Research Applications

In biomarker accuracy research, the choice between qPCR and dPCR significantly impacts result reliability and clinical applicability. dPCR offers particular advantages for copy number variation (CNV) analysis, a critical application in biomarker discovery and validation. A recent study comparing qPCR and two dPCR platforms for detecting FCGR3B copy number variations found full concordance between platforms across 32 donors with copy numbers ranging from 0 to 4 [6]. While all platforms provided reliable CN estimation, dPCR demonstrated advantages in precision and absolute quantification without requiring standard curves.

For liquid biopsy applications and rare mutation detection, dPCR's capability to identify mutant alleles present at frequencies as low as 0.001% in wild-type backgrounds makes it particularly valuable for cancer biomarker research and non-invasive prenatal testing [3]. Conversely, qPCR remains the preferred technology for high-throughput gene expression studies where relative quantification across multiple samples provides sufficient information for biomarker identification.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of qPCR and dPCR workflows requires carefully selected reagents and materials optimized for each technology platform. The following table outlines core components essential for both methods:

Table 3: Essential research reagents and materials for qPCR and dPCR workflows

| Reagent/Material | Function | Technology Application |

|---|---|---|

| Sequence-Specific Primers | Target DNA amplification through complementary binding | qPCR & dPCR |

| Fluorescent Probes (TaqMan) | Sequence-specific detection with fluorophore-quencher system | qPCR & dPCR |

| DNA Polymerase (Taq) | Enzyme catalyzing DNA strand synthesis during amplification | qPCR & dPCR |

| dNTP Mix | Nucleotide building blocks for new DNA strand synthesis | qPCR & dPCR |

| Buffer/MgCl₂ Solution | Optimal reaction environment maintenance and enzyme cofactor provision | qPCR & dPCR |

| Reverse Transcriptase | RNA-to-cDNA conversion for gene expression analysis | RT-qPCR & RT-dPCR |

| Partitioning Oil/Matrix | Physical separation of reactions into nanodroplets or nanowells | dPCR-specific |

| Microfluidic Chips/Cartridges | Sample partitioning and reaction containment platform | dPCR-specific |

| Quantification Standards | Standard curve generation for relative quantification | qPCR-specific |

Selection Guidelines for Biomarker Research Applications

Strategic Technology Selection

Choosing between qPCR and dPCR for biomarker accuracy research requires careful consideration of experimental objectives, sample characteristics, and practical constraints. The following decision pathway provides a systematic approach to technology selection:

Implementation Considerations and Challenges

Despite their advanced capabilities, both qPCR and dPCR face implementation challenges in biomarker research. qPCR remains limited by its dependence on standard curves and reduced precision for targets with low amplification efficiency or present in complex matrices containing PCR inhibitors [3]. While dPCR addresses many of these limitations, it introduces challenges related to higher costs, particularly for consumables; limited dynamic range constrained by partition numbers; and reduced throughput compared to qPCR platforms [5] [3].

The implementation of dPCR in routine clinical practice faces additional barriers, including higher costs and reduced automation compared to established qPCR workflows [5]. However, for research applications requiring absolute quantification, exceptional precision, or rare allele detection, dPCR's technical advantages often outweigh these practical limitations. As the field of biomarker research increasingly focuses on liquid biopsy applications and rare mutation detection, dPCR's superior performance characteristics position it as an essential tool for precision medicine initiatives.

Future Perspectives and Emerging Applications

The evolution of PCR technologies continues with emerging trends focusing on automation, miniaturization, and point-of-care applications [8] [3]. qPCR systems are incorporating enhanced sensitivity, expanded multiplexing capabilities, and integration with cloud computing for real-time data analysis [8]. Simultaneously, dPCR platforms are addressing current limitations through increased partition densities, improved throughput, and reduced costs [3].

The growing emphasis on precision medicine and biomarker-driven therapeutic development is accelerating the adoption of both technologies in novel research areas. qPCR remains indispensable for high-throughput biomarker validation and gene expression profiling in large cohort studies, while dPCR is finding expanding applications in liquid biopsy development, copy number variation analysis, and rare mutation detection for cancer biomarkers [9] [10] [3].

The integration of artificial intelligence with both qPCR and dPCR data analysis represents a promising frontier, potentially enhancing detection accuracy, enabling automated anomaly detection, and facilitating complex multi-analyte pattern recognition for biomarker signature identification [10] [3]. As these technologies continue to evolve, their complementary strengths will ensure both qPCR and dPCR maintain critical roles in the biomarker research ecosystem, each serving distinct applications while collectively advancing precision medicine initiatives.

Relative quantification in quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) is a widely used method to measure changes in gene expression by comparing the expression level of a target gene to one or more reference genes, typically housekeeping genes with stable expression levels [11]. This approach provides a fold-change difference in expression between samples without requiring knowledge of the exact initial copy numbers, making it particularly valuable for research applications where understanding relative differences is sufficient, such as in biomarker discovery, drug response studies, and pathway analysis [12] [11]. The fundamental principle relies on the relationship between the quantification cycle (Cq) value—the PCR cycle number at which the amplification curve crosses the fluorescence threshold—and the starting quantity of the target nucleic acid [13].

The accuracy of relative quantification depends critically on several technical factors: proper baseline correction to account for background fluorescence variations, appropriate threshold setting within the exponential amplification phase, and validation of amplification efficiency for both target and reference genes [14] [13]. When these parameters are carefully controlled, relative quantification provides a robust, reproducible method for gene expression analysis that balances practical feasibility with analytical precision, making it a cornerstone technique in molecular biomarker research [15].

Core Principles of Cq-Based Quantification

The Cq Value and Its Determinants

The quantification cycle (Cq) represents the fundamental measurement in qPCR analysis, defined as the fractional cycle number at which the fluorescence of a reaction crosses a predetermined threshold [13]. This value is inversely proportional to the logarithm of the initial target concentration: samples with higher starting concentrations of the target molecule will display lower Cq values, while those with lower concentrations will yield higher Cq values [14]. The mathematical relationship between Cq and starting concentration is expressed as: Cq = log(Nq) - log(N₀) / log(E), where Nq represents the threshold quantity, N₀ is the initial target copy number, and E is the amplification efficiency [13].

Several critical factors influence Cq values and must be carefully controlled for reliable quantification. Amplification efficiency (E), which ranges from 1 (no amplification) to 2 (perfect doubling each cycle), significantly impacts Cq values; small efficiency differences can substantially alter calculated expression ratios [13] [11]. The quantification threshold setting must be positioned within the exponential phase of amplification, above background fluorescence but below the plateau phase, where all amplification curves demonstrate parallel trajectories [14]. Additionally, sample-specific factors including PCR inhibitors, RNA quality, and reverse transcription efficiency can introduce variability that affects Cq measurements and must be addressed through proper experimental design and normalization strategies [13].

Standard Curves and Efficiency Determination

The standard curve method provides a robust approach for determining amplification efficiency and enabling relative quantification [12] [14]. This technique involves creating a dilution series of a known standard template—typically cDNA, synthetic oligonucleotides, or linearized plasmids—across several orders of magnitude [14] [11]. The Cq values obtained from these dilutions are plotted against the logarithm of the relative concentration or dilution factor, generating a standard curve with slope that reflects PCR efficiency [11].

Amplification efficiency is calculated from the standard curve slope using the formula: E = 10^(-1/slope) [11]. Ideal amplification with 100% efficiency (doubling each cycle) produces a slope of -3.32, while deviations from this value indicate suboptimal reactions [11]. Efficiency is typically expressed as a percentage: % Efficiency = (E-1) × 100, with acceptable ranges falling between 90-110% for most applications [11]. For relative quantification, the standard curve method quantitates unknown samples based on comparison to this curve, with results expressed as n-fold differences relative to a calibrator sample after normalization to reference genes [12].

Methodologies for Relative Quantification

Comparative ΔΔCq Method

The comparative ΔΔCq method provides a straightforward approach for relative quantification when the target and reference genes amplify with approximately equal efficiencies [11]. This method relies on the key assumption that amplification efficiencies between primer sets differ by no more than 5%, and both target and reference genes approach 100% efficiency [11]. The calculation involves multiple steps, beginning with the normalization of target gene Cq values to reference genes within each sample (ΔCq), followed by comparison of these normalized values to a calibrator sample (ΔΔCq) [11].

The fundamental equation for the ΔΔCq method is: RQ = 2^(-ΔΔCq), where RQ represents the relative expression ratio or fold-change [11]. The complete derivation involves:

- ΔCq(test) = Cq(target gene in test) - Cq(reference gene in test)

- ΔCq(calibrator) = Cq(target gene in calibrator) - Cq(reference gene in calibrator)

- ΔΔCq = ΔCq(test) - ΔCq(calibrator) [11]

This method's major advantage is its simplicity, as it doesn't require standard curves for each experiment and uses precious sample material more efficiently by eliminating the need for dilution series [12]. However, its validity completely depends on the assumption of equivalent, nearly perfect amplification efficiencies between target and reference genes, which must be verified experimentally prior to application [11].

Efficiency-Corrected Pfaffl Method

The Pfaffl method (also known as the standard curve method for relative quantification) provides a more robust approach for experiments where target and reference genes exhibit different amplification efficiencies [11]. This model incorporates actual reaction efficiencies into the calculation, correcting for efficiency variations that would otherwise compromise accuracy in the ΔΔCq method [11]. The efficiency-corrected calculation is expressed as: RQ = (Etarget)^(ΔCttarget) / (Ereference)^(ΔCtreference), where E represents the amplification efficiency (derived from standard curves) for target and reference genes, and ΔCt values represent the differences between calibrator and test samples for each gene [11].

The Pfaffl method offers significant advantages when working with suboptimal primer sets or challenging targets that cannot achieve perfect amplification efficiency [11]. Notably, the ΔΔCq method represents a special case of the Pfaffl method where both target and reference genes demonstrate 100% efficiency (E=2) [11]. The implementation of this approach requires preliminary experiments to establish standard curves and determine actual amplification efficiencies for each primer pair, adding experimental steps but substantially improving accuracy when efficiency differences exist [11].

Advanced Statistical Approaches

Recent methodological advances have introduced more sophisticated statistical approaches to qPCR data analysis, particularly Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA), which offers enhanced statistical power compared to traditional methods [15]. ANCOVA utilizes raw fluorescence data from the entire amplification curve rather than relying solely on Cq values, potentially detecting subtle expression differences that might be overlooked by conventional approaches [15]. This method also demonstrates greater robustness to variability in qPCR amplification efficiency and provides P-values that are not affected by such variations [15].

The implementation of these advanced methods aligns with growing emphasis on reproducibility and transparency in qPCR research [15]. Current best practices encourage researchers to share raw qPCR fluorescence data alongside detailed analysis scripts, enabling independent verification of results and facilitating meta-analyses [15]. Additionally, the development of graphical methods that simultaneously depict target and reference gene behavior within the same figure enhances interpretability and helps identify potential technical artifacts that might compromise experimental conclusions [15].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

qPCR Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow for relative quantification in qPCR, from assay design to data interpretation:

Efficiency Validation Protocol

Determining primer amplification efficiency is a critical prerequisite for accurate relative quantification [11]. The experimental protocol involves:

Template Preparation: Create a minimum of five 10-fold serial dilutions of cDNA or DNA template. Using cDNA from control samples is preferred, though artificial oligonucleotides or linearized plasmids containing the target sequence are acceptable alternatives [14] [11].

qPCR Run: Amplify each dilution in duplicate or triplicate using the target and reference gene primer sets under standardized cycling conditions [11].

Standard Curve Construction: Plot the Cq values obtained for each dilution against the logarithm of the dilution factor or concentration [11]. Apply linear regression to generate a standard curve with slope and correlation coefficient (R²) values.

Efficiency Calculation: Compute amplification efficiency using the formula E = 10^(-1/slope), with ideal efficiency (100%) corresponding to a slope of -3.32 [11]. Convert to percentage efficiency: % Efficiency = (E-1) × 100.

Validation Criteria: Primer sets with efficiencies between 90-110% are generally acceptable [11]. Discard primers falling outside this range or with R² values <0.985, as they may yield unreliable quantification [11].

Data Analysis Procedures

Proper data analysis begins with quality assessment of amplification curves and appropriate processing [14] [13]:

Baseline Correction: Define the baseline using cycles in the early linear phase (typically cycles 5-15), avoiding the initial cycles (1-5) that may contain reaction stabilization artifacts [14]. Proper baseline setting is crucial, as errors can significantly alter Cq values—miscalculations may cause Cq variations exceeding 2 cycles, substantially impacting fold-change calculations [14].

Threshold Setting: Position the quantification threshold within the exponential phase of all amplification curves, ensuring:

- The threshold is sufficiently above background fluorescence to avoid premature crossing

- All amplification curves demonstrate parallel trajectories in this region

- The threshold avoids the plateau phase where reaction kinetics become nonlinear [14]

Reference Gene Validation: Verify reference gene stability across all experimental conditions using algorithms such as geNorm or NormFinder [11]. When possible, normalize to multiple reference genes to improve accuracy, applying the geometric averaging method described by Vandesompele et al. [11].

Comparative Performance Data

Method Comparison Table

The following table summarizes the key characteristics, requirements, and applications of the main relative quantification methods:

| Parameter | ΔΔCq Method | Pfaffl Method | ANCOVA Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Efficiency Requirement | Equal efficiencies (≤5% difference) between target and reference genes [11] | Accommodates different efficiencies between assays [11] | Accounts for efficiency variations in model [15] |

| Standard Curve Need | Not required for final calculation, but needed for initial validation [11] | Required for efficiency determination [11] | Not required [15] |

| Key Assumptions | 100% PCR efficiency (E=2) for both target and reference [11] | Efficiency is constant across samples but can differ between genes [11] | Linear relationship between fluorescence and cycle number in exponential phase [15] |

| Calculation Complexity | Simple [11] | Moderate [11] | Advanced statistical implementation [15] |

| Data Utilized | Only Cq values [11] | Only Cq values with efficiency corrections [11] | Raw fluorescence curves [15] |

| Statistical Power | Lower, especially with efficiency variations [15] | Moderate, with proper efficiency correction [15] | Higher, detects smaller effect sizes [15] |

| Reproducibility Concerns | High when efficiencies unequal [13] | Moderate to high with proper validation [11] | Potentially higher with shared raw data [15] |

Technology Comparison Studies

Recent comparative studies provide performance data across quantification platforms:

qPCR vs. Digital PCR: A 2025 study comparing qPCR and droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) for DNA copy number measurement found ddPCR showed 95% concordance with the gold standard (PFGE), while qPCR results were only 60% concordant [16]. qPCR demonstrated an average 22% deviation from reference values, with particular inaccuracy at higher copy numbers [16].

qPCR vs. nCounter NanoString: A 2025 analysis of oral cancer samples revealed weak to moderate correlation (Spearman's r: 0.188-0.517) between qPCR and nCounter techniques for copy number alteration validation [17]. Cohen's kappa scores showed moderate to substantial agreement for only 8 of 24 genes analyzed, highlighting platform-specific variability [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table outlines essential materials and reagents required for implementing relative quantification in qPCR experiments:

| Reagent/Material | Function | Critical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| High-Quality RNA/DNA | Template for quantification | Purity (A260/280 ~1.8-2.0), integrity (RIN >7), appropriate storage conditions [13] |

| Reverse Transcription Kit | cDNA synthesis from RNA | Consistent efficiency across samples, minimal batch-to-batch variation [13] |

| Sequence-Specific Primers | Target amplification | Validated specificity, minimal primer-dimer formation, appropriate Tm (typically 58-62°C) [11] |

| Fluorogenic Probes | Detection of amplified product | Probe chemistry (TaqMan, molecular beacons), quenching efficiency, spectral compatibility [13] |

| qPCR Master Mix | Reaction components | Polymerase fidelity, buffer optimization, inhibitor resistance [13] |

| Reference Gene Assays | Normalization control | Validated stability across experimental conditions, expression level comparable to targets [11] |

| Standard Curve Templates | Efficiency determination | Known concentration, sequence identity to target, appropriate matrix [14] [11] |

| Low-Binding Tubes/Tips | Liquid handling | Minimize nucleic acid adsorption, especially for dilute samples [12] |

Analysis Workflow and Decision Pathway

The following diagram outlines the decision process for selecting and implementing the appropriate quantification method:

Relative quantification using Cq values and standard curves remains a fundamental methodology in qPCR analysis, with the comparative ΔΔCq and efficiency-corrected Pfaffl methods serving as the principal approaches for most research applications [11]. The choice between these methods depends primarily on the equivalence of amplification efficiencies between target and reference genes, which must be determined through rigorous validation experiments [11]. Recent advances in statistical approaches, particularly ANCOVA modeling of raw fluorescence data, offer promising alternatives with enhanced statistical power and reduced sensitivity to efficiency variations [15].

The implementation of rigorous methodology aligned with MIQE (Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments) and FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reproducible) principles substantially improves the reliability and reproducibility of qPCR data [15] [13]. As biomarker research continues to evolve toward clinical applications, proper understanding and implementation of relative quantification principles will remain essential for generating robust, translatable findings in drug development and precision medicine [10].

Digital PCR (dPCR) represents a significant technological advancement in nucleic acid quantification by enabling absolute measurement without standard curves. This methodology relies on sample partitioning into thousands of nanoscale reactions, endpoint amplification, and Poisson statistical analysis to calculate target concentration with exceptional precision. Particularly valuable for biomarker research and applications requiring detection of minor frequency variations, dPCR outperforms quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) in sensitivity, precision, and tolerance to PCR inhibitors. This guide provides an objective comparison of dPCR versus qPCR performance, supported by experimental data relevant to researchers and drug development professionals.

Digital PCR operates on a fundamentally different principle than quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR). While qPCR monitors amplification kinetics in a bulk reaction, dPCR partitions a sample into thousands to millions of individual reactions, performs endpoint amplification, and applies Poisson statistics to determine absolute target concentration [3]. This partitioning-based approach provides dPCR with several key advantages: it eliminates the need for standard curves, reduces the impact of PCR efficiency variations, and increases tolerance to inhibitors commonly encountered in complex biological samples [18] [19].

The evolution of dPCR technology has progressed through several platforms, including droplet-based systems (ddPCR) that create water-in-oil emulsions and nanoplate-based systems that use microfluidic chips to generate partitions [20] [21]. Despite these implementation differences, all dPCR platforms share the core principles of limiting dilution, endpoint detection, and statistical analysis that enable absolute quantification of nucleic acids with precision unattainable with qPCR methodologies [3] [19].

Principle of dPCR: Partitioning and Poisson Statistics

Core Mechanism

The fundamental innovation of dPCR lies in its sample partitioning approach. The PCR reaction mixture is randomly distributed across thousands of individual partitions, with each partition effectively serving as a separate amplification reactor. Through limiting dilution, most partitions contain either zero or one target molecule, creating a binary digital readout (positive/negative) after endpoint PCR [3] [19]. This partitioning occurs before amplification begins, typically generating 20,000-26,000 partitions in modern systems [18] [20].

Poisson Distribution Analysis

The quantification in dPCR relies on Poisson distribution statistics, which account for the random distribution of molecules across partitions. The fundamental equation is: [ C = -ln(1-p) \times N/V ] Where C is the target concentration, p is the fraction of positive partitions, N is the total number of partitions, and V is the partition volume [3]. This statistical approach enables absolute quantification without reference standards and provides greater precision, particularly for low-abundance targets [22].

Figure 1: dPCR Workflow and Principle. The sample is partitioned, amplified via endpoint PCR, and analyzed using Poisson statistics for absolute quantification.

Direct Performance Comparison: dPCR vs. qPCR

Analytical Performance Metrics

Multiple studies have systematically compared the performance characteristics of dPCR and qPCR across various applications and sample types. The accumulated evidence demonstrates clear advantages for dPCR in precision, sensitivity, and accuracy, particularly at low target concentrations.

Table 1: Comprehensive Performance Comparison of dPCR vs. qPCR

| Performance Parameter | Digital PCR | Quantitative Real-Time PCR | Experimental Support |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantification Method | Absolute (no standard curve) | Relative (requires standard curve) | [3] [19] |

| Precision (CV%) | 37-86% lower CV than qPCR [22]; Median CV: 4.5% for periodontal pathogens [18] | Higher variability; Significantly higher CV than dPCR | [18] [22] |

| Sensitivity | Superior for low-abundance targets; Detects mutation rates ≥0.1% | Limited sensitivity; Detects mutation rates >1% | [18] [19] |

| Dynamic Range | 3-6 logs depending on partition count | 5-7 logs with standard curve | [3] [21] |

| Tolerance to Inhibitors | High (partitioning dilutes inhibitors) | Moderate to low (inhibitors affect amplification efficiency) | [18] [3] |

| Accuracy at Low Concentration | Higher accuracy; Reduces false negatives in pathogen detection [18] | Underestimates targets at low concentrations (<3 log10Geq/mL) | [18] [22] |

| Reproducibility | Superior day-to-day reproducibility (7-fold improvement) [22] | Moderate reproducibility affected by amplification efficiency | [22] |

Platform Comparison: Nanoplate vs. Droplet dPCR

Different dPCR platforms show variations in performance characteristics, though both outperform qPCR in key metrics.

Table 2: Comparison of dPCR Platforms Using Synthetic Oligonucleotides and Environmental Samples

| Parameter | Nanoplate dPCR (QIAcuity) | Droplet dPCR (QX200) | Experimental Details |

|---|---|---|---|

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | 0.39 copies/µL | 0.17 copies/µL | Synthetic oligonucleotides with serial dilution [21] |

| Limit of Quantification (LOQ) | 1.35 copies/µL | 4.26 copies/µL | 3rd degree polynomial model fit [21] |

| Precision (CV%) with Restriction Enzymes | CV 0.6-27.7% (EcoRI), 1.6-14.6% (HaeIII) | CV 2.5-62.1% (EcoRI), <5% (HaeIII) | Paramecium tetraurelia DNA; enzyme choice impacts precision [21] |

| Accuracy (R²) | R²adj = 0.98 | R²adj = 0.99 | Comparison of expected vs. measured gene copies [21] |

| Partitioning Method | Microfluidic nanoplates (26,000 partitions) | Water-oil emulsion droplets | [18] [20] |

Experimental Protocols and Validation Data

Periodontal Pathobiont Detection Study

A 2025 study directly compared multiplex dPCR and qPCR for detecting periodontal pathogens in subgingival plaque samples, providing robust experimental data on performance differences [18].

Methodology:

- Sample Collection: Subgingival plaque samples from 20 periodontitis patients and 20 healthy controls collected with absorbent paper points

- DNA Extraction: QIAamp DNA Mini kit (Qiagen) following manufacturer's instructions

- dPCR Protocol: QIAcuity Nanoplate 26k 24-well system; 40µL reactions with restriction enzyme digestion; 45 amplification cycles

- Targets: Porphyromonas gingivalis, Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans, Fusobacterium nucleatum

- Analysis: Poisson quantification with QIAcuity Software Suite; statistical analysis included Mann-Whitney U test, McNemar's test, and Bland-Altman plots

Results: dPCR demonstrated superior sensitivity with high linearity (R² > 0.99) and significantly lower intra-assay variability (median CV%: 4.5% for dPCR vs. higher for qPCR, p = 0.020). Critically, dPCR detected lower bacterial loads, particularly for P. gingivalis and A. actinomycetemcomitans, with qPCR producing false negatives at low concentrations (<3 log10Geq/mL) and underestimating A. actinomycetemcomitans prevalence 5-fold in periodontitis patients [18].

miRNA Quantification for Cancer Biomarker Analysis

A landmark study compared ddPCR and qPCR for microRNA quantification, demonstrating substantial improvements in precision and diagnostic performance [22].

Methodology:

- Sample Design: Six synthetic miRNA oligonucleotides diluted in water and plasma RNA matrix

- Experimental Design: Hierarchical nested replicates with triplicate dilution series prepared on different days

- Platform Comparison: Droplet digital PCR (Bio-Rad) vs. standard real-time PCR using identical reaction mixtures

- Clinical Validation: Analysis of miR-141 in serum from 20 prostate cancer patients and 20 controls

Results: ddPCR reduced coefficients of variation by 37-86% compared to qPCR and improved day-to-day reproducibility by a factor of seven. In clinical serum samples, ddPCR better resolved cancer cases from controls (P = 0.0036 vs. P = 0.1199 for qPCR) and showed superior diagnostic accuracy (AUC: 0.770 for ddPCR vs. 0.645 for qPCR) [22].

Research Reagent Solutions for dPCR Implementation

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for dPCR Experiments

| Reagent/Equipment | Function | Example Products/Alternatives |

|---|---|---|

| dPCR Instrument | Partitioning, thermocycling, imaging | QIAcuity series, Bio-Rad QX200, Thermo Fisher QuantStudio [18] [20] |

| Partitioning Consumables | Create nanoreactors for individual PCRs | QIAcuity Nanoplates (26,000 partitions), Droplet generation cartridges [18] [20] |

| PCR Master Mix | Provides enzymes, nucleotides, buffer for amplification | QIAcuity Probe PCR Kit, ddPCR Supermix [18] [21] |

| Sequence-Specific Probes/Primers | Target detection with high specificity | Hydrolysis probes, double-quenched designs [18] |

| Restriction Enzymes | Improve DNA accessibility and precision | EcoRI, HaeIII (choice impacts results) [21] |

| DNA Extraction Kits | Nucleic acid purification from samples | QIAamp DNA Mini kit, Maxwell RSC systems [18] [20] |

| Analysis Software | Poisson calculation and data interpretation | QIAcuity Software Suite, QX Manager [18] [20] |

Application Recommendations and Implementation Guidelines

When to Choose dPCR vs. qPCR

The choice between dPCR and qPCR should be guided by specific application requirements and experimental goals:

Select dPCR for:

- Absolute quantification without standard curves [3] [19]

- Detection of rare targets or minor allele frequencies (<1%) [19]

- Applications requiring maximum precision and reproducibility [22]

- Analysis of samples with potential PCR inhibitors [18] [3]

- Low-abundance target detection in complex backgrounds [18] [22]

qPCR remains suitable for:

- High-throughput screening with broad dynamic range [3]

- Gene expression analysis with established reference genes [19]

- Applications where cost-effectiveness and established protocols are priorities [3]

- Situations requiring rapid results with minimal optimization [19]

Figure 2: Decision Framework for Selecting Between dPCR and qPCR Platforms

Digital PCR represents a paradigm shift in nucleic acid quantification, offering absolute measurement capabilities through its core principles of sample partitioning and Poisson statistical analysis. The accumulated experimental evidence demonstrates clear advantages over qPCR in precision, sensitivity, and robustness, particularly for applications requiring detection of low-abundance targets or precise quantification without reference standards. While qPCR remains suitable for many applications, dPCR provides superior performance for biomarker discovery, rare variant detection, and analysis of complex samples where quantification accuracy is paramount. As dPCR technology continues to evolve with improved workflows and reduced costs, its adoption in research and clinical diagnostics is expected to expand significantly.

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) and digital PCR (dPCR) represent two pivotal technologies in molecular diagnostics and biomarker research. These platforms have revolutionized the detection and quantification of nucleic acids, enabling advances in personalized medicine, drug development, and clinical diagnostics. qPCR, also known as real-time PCR, allows for the monitoring of amplification as it occurs, providing relative quantification of target sequences through cycle threshold (Cq) values. In contrast, dPCR partitions a sample into thousands of individual reactions, enabling absolute quantification without the need for standard curves. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the core technical distinctions in amplification efficiency, calibration requirements, and data output between these platforms is critical for selecting the appropriate technology for biomarker accuracy studies. This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison to inform these strategic decisions, framed within the context of optimizing biomarker research outcomes.

Core Technical Comparison: qPCR versus dPCR

The fundamental differences between qPCR and dPCR significantly impact their application in biomarker research. The following table summarizes the key technical parameters:

Table 1: Fundamental Technical Differences Between qPCR and dPCR Platforms

| Technical Parameter | Quantitative PCR (qPCR) | Digital PCR (dPCR) |

|---|---|---|

| Quantification Method | Relative quantification (requires standard curve) | Absolute quantification (counts positive/negative partitions) |

| Amplification Efficiency | Highly sensitive to reaction efficiency variations [15] | More robust to PCR efficiency variations [23] [3] |

| Calibration Requirements | Requires standard curve in each run for accurate quantification [24] | Does not require standard curves [3] [25] |

| Data Output | Cycle threshold (Cq) values; relative expression | Copy number per reaction; absolute quantification |

| Sensitivity & Dynamic Range | High sensitivity; broad dynamic range | Superior sensitivity for rare targets; detection of single molecules |

| Tolerance to Inhibitors | Moderate sensitivity to PCR inhibitors | Higher resilience to PCR inhibitors [3] [25] |

| Throughput & Cost | High-throughput; cost-effective per sample [3] | Lower throughput; higher cost per sample [3] |

| Multiplexing Capability | Well-established for multiplex detection | Emerging multiplexing capabilities |

Amplification Efficiency

Theoretical Foundations and Measurement

Amplification efficiency (E) refers to the fold increase of amplicon per PCR cycle, ideally approaching 2.0 (100% efficiency), meaning the product doubles every cycle [26]. In practice, efficiency is influenced by multiple factors including primer design, template quality, reagent concentrations, and reaction conditions [27]. qPCR determines efficiency empirically from standard curves, calculated as E = 10^(-1/slope) - 1 [24]. Optimal efficiency falls between 90-110%, corresponding to slopes of -3.6 to -3.1 [24]. dPCR, by partitioning the reaction, mitigates efficiency concerns as quantification relies on binary endpoint detection (positive/negative partitions) rather than amplification kinetics, making it less vulnerable to efficiency variations [23] [3].

Impact of Sequence-Specific Biases

In multi-template PCR applications, such as biomarker panels, sequence-specific amplification efficiencies can cause significant quantification bias. Deep learning models have identified that specific sequence motifs adjacent to priming sites, particularly those enabling adapter-mediated self-priming, are closely associated with poor amplification efficiency [27]. This efficiency bias progressively skews coverage distributions with increasing cycle numbers, potentially compromising biomarker accuracy. One study demonstrated that sequences with poor amplification efficiency (as low as 80% relative to the population mean) could be halved in relative abundance every 3 cycles, effectively disappearing from detection after 60 cycles [27].

Comparative Experimental Data

Experimental comparisons highlight practical differences in how platforms handle amplification efficiency:

Table 2: Experimental Comparison of Amplification Efficiency Parameters

| Study Focus | qPCR Performance | dPCR Performance | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Methylation Quantification [23] | N/A | Strong correlation (r=0.954) with ddPCR; sensitivity 99.08%, specificity 99.62% | CDH13 promoter methylation in 141 FFPE breast cancer samples |

| Enterotoxigenic B. fragilis Detection [25] | TaqMan qPCR: 48-fold higher copies than SYBR green; LOD <1 copy/μL | 75-fold higher copies than SYBR green qPCR; LOD <1 copy/μL | Detection of bft gene in clinical stool samples from colorectal cancer patients |

| miRNA Profiling Reproducibility [28] | Inter-run concordance: Moderate (ccc >0.9) | N/A | Cross-platform evaluation of miRNA quantitation in human biofluids |

| Inter-assay Variability [24] | Efficiency variability between runs: 90.97%-94.63% for viral targets | N/A | 30 independent standard curve experiments for 7 viruses |

Calibration Needs

qPCR Standard Curve Requirements

qPCR quantification relies heavily on standard curves constructed from serial dilutions of known template concentrations. This approach exhibits inherent variability that must be accounted for in rigorous biomarker research. A comprehensive study evaluating inter-assay variability of standard curves for seven viruses across 30 independent experiments found that although all viruses presented adequate efficiency rates (>90%), significant variability was observed between assays [24]. Notably, norovirus GII showed the highest inter-assay variability in efficiency, while SARS-CoV-2 N2 gene exhibited the largest Cq variability (CV 4.38-4.99%) and the lowest efficiency (90.97%) [24]. These findings underscore the necessity of including standard curves in every qPCR run to ensure reliable results in biomarker applications.

dPCR Absolute Quantification Without Calibration

dPCR eliminates the need for standard curves by providing absolute quantification through Poisson statistical analysis of positive and negative partitions [3] [25]. This partition-based approach directly yields copy number concentrations, removing a major source of variability and potential bias. The calibration-free nature of dPCR makes it particularly advantageous for applications requiring high precision, such as detecting rare genetic variants, validating biomarker concentrations, and quantifying minute expression differences in limited samples [23] [3].

Impact on Biomarker Measurement Accuracy

The calibration approach directly impacts measurement accuracy and reproducibility in biomarker studies. Research indicates that omitting standard curves in qPCR experiments to reduce costs can compromise result accuracy, particularly when comparing results across different experiments or laboratories [24]. dPCR's inherent lack of dependency on external standards makes it preferable for establishing standardized biomarker measurements across multiple sites or for creating reference materials. However, the higher per-sample cost and lower throughput of dPCR often make qPCR the more practical choice for large-scale biomarker screening studies [3].

Data Output Characteristics

Quantification Metrics and Output Format

qPCR and dPCR generate fundamentally different data outputs that influence their interpretation in biomarker research:

Table 3: Data Output Characteristics Comparison

| Output Characteristic | qPCR | dPCR |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Metric | Cycle threshold (Cq) or Crossing point (Cp) | Copies/μL (absolute concentration) |

| Normalization Requirements | Requires reference genes for relative quantification [15] [29] | Can be used without normalization or with reference genes for ratio-based results |

| Precision & Reproducibility | Moderate inter-assay variability [24] | High reproducibility for low-abundance targets [28] [23] |

| Dynamic Range | 6-8 orders of magnitude | 5 orders of magnitude for droplet-based systems [3] |

| Data Analysis Complexity | Varies from simple (2-ΔΔCT) to advanced (ANCOVA, linear modeling) [15] | Simplified analysis through proprietary software |

Analysis Methods and Statistical Considerations

qPCR data analysis has evolved beyond the commonly used 2-ΔΔCT method, which often overlooks amplification efficiency variability. More robust statistical approaches like Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA) enhance statistical power and are less affected by variability in qPCR amplification efficiency [15]. Proper analysis must also account for reference gene stability, as using inappropriate reference genes remains a significant source of error in biomarker studies [15] [29]. dPCR data analysis employs Poisson statistics to account for partition occupancy, with precision increasing with higher partition numbers [3]. This fundamental difference in data structure requires distinct statistical approaches when designing biomarker validation studies.

Experimental Workflow for Platform Comparison

The following diagram illustrates a typical experimental workflow for comparing PCR platform performance in biomarker detection:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of PCR-based biomarker studies requires careful selection of reagents and materials. The following table details essential components and their functions:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for PCR-Based Biomarker Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits (e.g., DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit [23] [25]) | Isolation of high-quality DNA/RNA from various sample types | Critical for removing PCR inhibitors; choice depends on sample matrix (tissue, biofluids, FFPE) |

| Reverse Transcription Kits (for RNA targets) | Conversion of RNA to cDNA for RT-qPCR/RT-dPCR | Source of significant variability; optimized kits reduce technical noise [29] |

| PCR Master Mixes | Contains polymerase, dNTPs, buffers, MgCl₂ for amplification | Polymerase choice affects efficiency; inhibitor-resistant formulations valuable for complex samples |

| Sequence-Specific Primers/Probes | Target recognition and amplification | Design critically impacts efficiency and specificity; TaqMan probes offer higher specificity than SYBR Green [25] |

| Standard Curve Materials (qPCR) | Quantification reference standards | Synthetic oligonucleotides with known concentrations provide accurate standards [24] |

| Digital PCR Partitioning Plates/Chips (dPCR) | Sample compartmentalization for absolute quantification | Nanoplate or droplet-based systems; partition number affects precision [23] [3] |

| Quality Control Materials | Monitoring technical performance | Positive controls, no-template controls, inter-assay controls essential for rigor [24] |

The selection between qPCR and dPCR platforms for biomarker accuracy research involves careful consideration of technical requirements and practical constraints. qPCR offers established, cost-effective solutions for high-throughput applications where relative quantification suffices and sample quality is consistent. However, its dependence on calibration curves and sensitivity to amplification efficiency variations can introduce variability. dPCR provides superior precision for absolute quantification of rare targets and challenging samples, with inherent resilience to efficiency fluctuations and inhibitors. For biomarker research requiring the highest accuracy, particularly in clinical validation studies or when analyzing low-abundance targets, dPCR's technical advantages often justify its implementation. Ultimately, the optimal platform choice depends on specific research objectives, target abundance, required precision, and available resources, with both technologies offering complementary strengths in the biomarker development pipeline.

In the fields of molecular diagnostics and drug development, the accuracy of a biomarker is fundamentally defined by its sensitivity, specificity, and precision. These parameters form the essential triad that determines a test's analytical performance and its subsequent clinical utility [30]. As researchers and pharmaceutical professionals increasingly rely on molecular tools for patient stratification, therapeutic monitoring, and companion diagnostics, rigorous validation of these parameters becomes paramount. Biomarker validation transitions a promising molecular signal into a reliable tool for clinical decision-making, encompassing everything from diagnosis and prognosis to predicting treatment response [30]. Within this framework, quantitative PCR (qPCR) and digital PCR (dPCR) platforms have emerged as cornerstone technologies for nucleic acid-based biomarker analysis. This guide provides an objective comparison of these platforms, focusing on their performance in validating the critical triad of accuracy metrics, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies.

Fundamental Concepts: Defining the Validation Parameters

The validation of a biomarker assay requires a clear understanding of its key performance characteristics, which are defined as follows [30]:

- Analytical Sensitivity: The ability of an assay to detect the lowest concentration of an analyte. It is often expressed as the Limit of Detection (LOD), the minimum detectable concentration.

- Analytical Specificity: The ability of an assay to distinguish the target analyte from other, non-target analytes in the sample.

- Analytical Precision: The closeness of agreement between repeated measurements of the same sample under prescribed conditions. It is often reported as the coefficient of variation (CV) between replicates.

- Diagnostic Sensitivity: The proportion of true positives that are correctly identified by the assay (True Positive Rate).

- Diagnostic Specificity: The proportion of true negatives that are correctly identified by the assay (True Negative Rate).

It is critical to differentiate these analytical performance metrics from a test's clinical performance, which includes positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV), as these are influenced by disease prevalence in the study population [30]. The validation process must be fit-for-purpose, meaning the level of rigor is sufficient to support the biomarker's intended context of use [30].

Figure 1: A conceptual map of biomarker validation, showing the relationship between core performance parameters and influencing factors. The validation pathway is guided by the fit-for-purpose principle, leading to appropriate technology selection.

Platform Comparison: qPCR vs. dPCR for Biomarker Analysis

The choice between quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) and digital PCR (dPCR) is crucial, as each technology offers distinct advantages and limitations for biomarker validation.

qPCR is a well-established gold standard that monitors the amplification of target DNA in real-time. Its quantification relies on the cycle threshold (Cq), which is the cycle number at which the fluorescence signal crosses a predefined threshold. The Cq value is compared to a standard curve to determine the initial target quantity [31] [32]. This dependency on a calibration curve can introduce variability [33].

dPCR, often called the third-generation PCR, takes a different approach. The PCR reaction mixture is partitioned into thousands of individual nanoliter- or picoliter-scale reactions. Following end-point amplification, each partition is analyzed as either positive (containing the target) or negative (not containing the target). The absolute concentration of the target is then calculated directly using Poisson statistics, without the need for a standard curve [21] [34]. This partitioning step is the source of dPCR's enhanced precision and resistance to inhibitors.

Comparative Performance Data from Recent Studies

Recent studies directly comparing these platforms provide quantitative performance data. A 2025 study on respiratory virus diagnostics during the 2023-2024 "tripledemic" found that dPCR demonstrated superior accuracy, particularly for high viral loads of influenza A, influenza B, and SARS-CoV-2, and for medium loads of RSV. It showed greater consistency and precision than Real-Time RT-PCR across these viral targets [5].

Another 2025 study compared the precision of two dPCR platforms—the QX200 Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR) from Bio-Rad and the QIAcuity One nanoplate-based dPCR from QIAGEN—for gene copy number analysis. The study found that both platforms demonstrated similar detection and quantification limits and yielded high precision across most analyses. However, it highlighted that the choice of restriction enzyme (HaeIII vs. EcoRI) significantly impacted precision, especially for the QX200 system [21].

Table 1: Comparative Analytical Sensitivity and Specificity of PCR Platforms

| Platform | Principle of Quantification | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Analytical Specificity | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantitative PCR (qPCR) | Relative quantification via Cq and standard curve [31] | Varies with assay; requires standard curve for LOD determination | High, but can be affected by reaction inhibitors and non-specific amplification [33] | High throughput, cost-effective, well-established protocols, widely available [32] |

| Digital PCR (dPCR) | Absolute quantification via Poisson statistics of partitioned reactions [21] [34] | QIAcuity ndPCR: ~0.39 copies/µL input [21] QX200 ddPCR: ~0.17 copies/µL input [21] | Superior for distinguishing rare alleles and low-abundance targets; less affected by PCR inhibitors [5] [34] | Absolute quantification without standard curve, high precision, high tolerance to inhibitors, excellent for rare target detection [5] [21] |

Table 2: Comparative Precision Data from Platform Studies

| Study & Sample Type | qPCR Precision (CV) | dPCR Precision (CV) | Notes & Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Respiratory Viruses (2025) [5] | Not explicitly stated, but lower than dPCR for medium/high viral loads | Superior consistency and precision, especially for intermediate viral levels | Study involved 123 clinical samples; dPCR demonstrated superior accuracy. |

| Gene Copy Number in Ciliates (2025) [21] | Not the focus of this comparative dPCR study | QIAcuity ndPCR: CVs 0.6%-27.7% (EcoRI) QX200 ddPCR: CVs 2.5%-62.1% (EcoRI) | Precision highly dependent on restriction enzyme. With HaeIII, ddPCR CVs fell to <5%. |

| Ecotoxicology Biomarkers [32] | No statistical differences from ddPCR | No statistical differences from RT-qPCR | Both methods showed comparable linearity and efficiency, but RT-qPCR was faster and more cost-effective. |

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking PCR Performance

To ensure reliable and reproducible comparisons between platforms, a standardized experimental approach is critical. The following protocols are synthesized from the cited studies.

Protocol 1: Comparative Analysis of dPCR and RT-qPCR for Viral Load Quantification

This protocol is adapted from the 2025 study on respiratory viruses [5].

Step 1: Sample Collection and Stratification

- Collect respiratory samples (e.g., nasopharyngeal swabs) and confirm positivity for target viruses (Influenza A/B, RSV, SARS-CoV-2) using a standard RT-qPCR panel.

- Stratify samples into categories based on RT-qPCR Ct values: high (Ct ≤ 25), medium (Ct 25.1–30), and low (Ct > 30) viral load.

Step 2: Nucleic Acid Extraction

- Extract RNA from all samples using an automated platform (e.g., KingFisher Flex system) with a viral/pathogen nucleic acid isolation kit to ensure consistency across the technological comparison.

Step 3: Parallel PCR Analysis

- RT-qPCR Workflow: Use commercial multiplex respiratory panel kits on a standard thermocycler (e.g., CFX96). Include all necessary positive and negative controls.

- dPCR Workflow: Perform assays on a nanoplate-based dPCR system (e.g., QIAcuity). Use a multiplexed assay for the same viral targets. Load samples into nanoplates for partitioning and endpoint PCR. Analyze fluorescence signals with the instrument's software to obtain absolute copy numbers.

Step 4: Data Analysis

- Compare the quantitative results (viral load) and qualitative detection (positive/negative calls) between the two platforms across the different Ct-based strata. Statistical analysis (e.g., Kruskal-Wallis test) can be used to compare the precision and accuracy of quantification.

Protocol 2: Evaluating Precision and Limits of Detection for Gene Copy Number Analysis

This protocol is based on the 2025 study comparing dPCR platforms [21].

Step 1: Preparation of Standard Material

- Use synthetic oligonucleotides with a known sequence of the target gene. Precisely dilute the oligonucleotides to create a dilution series covering a wide dynamic range (e.g., from < 0.5 copies/µL to > 3000 copies/µL input).

Step 2: Assessment of Restriction Enzyme Digestion Impact

- To analyze genomic DNA, test the impact of different restriction enzymes (e.g., EcoRI and HaeIII) on the precision of copy number quantification. This step is critical for accessing tandemly repeated genes.

Step 3: Parallel dPCR Analysis on Multiple Platforms

- Run the same dilution series and genomic DNA samples on the platforms being compared (e.g., QIAcuity ndPCR and QX200 ddPCR). Follow the manufacturer's recommended protocols for reaction setup and thermal cycling for each system.

Step 4: Determination of LOD and LOQ

- Limit of Detection (LOD): The lowest concentration at which the target can be reliably detected.

- Limit of Quantification (LOQ): The lowest concentration at which the target can be reliably quantified with acceptable precision and accuracy. This can be determined using a polynomial model fit to the data from the dilution series [21].

Step 5: Precision Calculation

- For each sample and platform, run multiple technical replicates. Calculate the coefficient of variation (CV) for the measured copy numbers to assess intra-assay and inter-assay precision.

Figure 2: A side-by-side comparison of the core experimental workflows for qPCR and dPCR platforms. The fundamental difference lies in the method of quantification, which drives the key performance characteristics.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful biomarker validation relies on a suite of high-quality research reagents. The following table details key solutions and their critical functions in the experimental workflow.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for PCR-Based Biomarker Validation

| Reagent / Material | Function & Importance in Validation | Considerations for Selection |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | Purifies DNA/RNA from complex biological matrices; quality and consistency directly impact assay sensitivity and precision [5] [30]. | Automated platforms (e.g., KingFisher Flex, STARlet) enhance reproducibility. Kits should be selected based on sample type (e.g., swab, tissue, wastewater) [5] [35]. |

| Reverse Transcriptase (for RNA targets) | Converts RNA to complementary DNA (cDNA) for PCR amplification; its fidelity and efficiency are critical for accurate quantification of RNA biomarkers [30]. | High-efficiency enzymes are essential for low-abundance targets. The choice between random hexamers and gene-specific priming depends on the assay design. |

| PCR Master Mixes | Contains polymerase, dNTPs, and optimized buffers. Its quality determines amplification efficiency, specificity, and robustness against inhibitors [33] [21]. | dPCR systems often require specific master mixes (e.g., Naica multiplex PCR Mix, ddPCR supermix). Tolerance to inhibitors is a key differentiator [33] [21]. |

| Primers & Probes | Define the analytical specificity of the assay by determining the exact nucleic acid sequence targeted for amplification [30]. | Must be rigorously validated for minimal off-target binding. Hydrolysis probes (TaqMan) are common for multiplex qPCR and dPCR. Concentration optimization is vital [33]. |

| Restriction Enzymes | Used in copy number variation studies to digest genomic DNA, improving access to the target sequence and enhancing amplification efficiency and precision [21]. | The choice of enzyme (e.g., HaeIII vs. EcoRI) can significantly impact the precision and accuracy of results, especially in dPCR [21]. |

| Reference Genes / Materials | For qPCR, stable reference genes are required for data normalization. For both qPCR and dPCR, synthetic oligonucleotides are used as standards for determining LOD/LOQ [21] [36]. | Reference genes must be validated for stable expression under specific experimental conditions. Digital PCR Counting standards can be used for dPCR quality control [30] [36]. |

The objective comparison of qPCR and dPCR platforms reveals a clear trade-off between established efficiency and superior precision. qPCR remains a powerful, cost-effective workhorse for high-throughput applications where relative quantification is sufficient [32]. However, for applications demanding the highest level of absolute quantification, such as detecting rare mutations in liquid biopsies, validating low-abundance biomarkers, or achieving maximum precision without calibration, dPCR demonstrates a distinct and growing advantage [5] [34].

The future of biomarker validation lies in selecting the right tool for the specific context of use. As dPCR technology continues to evolve, becoming more automated and integrated with other omics technologies, its role in companion diagnostic development and personalized medicine is poised to expand significantly [34] [37]. For researchers and drug developers, a rigorous, fit-for-purpose validation strategy—underpinned by a clear understanding of sensitivity, specificity, and precision—is the definitive factor in translating a promising biomarker from a research finding into a clinically actionable tool.

Platform Selection in Practice: Matching qPCR and dPCR to Biomarker Applications

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) remains one of the most widely utilized techniques in molecular biology laboratories for quantifying nucleic acid sequences, with particular dominance in gene expression analysis and detection of abundant targets. Despite the emergence of newer technologies like digital PCR and various high-throughput sequencing platforms, qPCR maintains its position due to its cost-effectiveness, established workflows, and robust performance characteristics. This guide objectively compares qPCR's performance against alternative technologies within high-throughput biomarker research contexts, drawing on recent experimental data to delineate its optimal use cases, limitations, and implementation best practices.

The technique's foundation in real-time fluorescence monitoring during polymerase chain reaction amplification provides both quantitative and qualitative information without opening reaction tubes, reducing contamination risk while increasing throughput capabilities. Modern instrumentation facilitates substantial parallel processing with 96, 384, or even 1536 reactions in a single run, positioning qPCR as a workhorse for validation studies and targeted analyses where sample numbers are high but the gene targets are well-defined [38]. Within biomarker accuracy research specifically, qPCR's value proposition centers on its established reproducibility, minimal sample requirement, and relatively low operational complexity when properly validated and executed.

Technology Comparison: qPCR Versus Alternative Platforms

Performance Benchmarking Against Competing Methodologies

Table 1: Platform Comparison for Gene Expression and Copy Number Analysis

| Parameter | qPCR | nCounter NanoString | RNA-seq | Digital PCR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Throughput (samples) | High (96-1536 per run) | Moderate | Very High | Low to Moderate |

| Multiplexing Capacity | Limited (typically <6-plex) | High (up to 800 targets) | Genome-wide | Limited |

| Sensitivity | High | Comparable to qPCR | High | Very High |

| Dynamic Range | ~9 logs with optimized assays | Wide | Very Wide | Limited |

| Sample Input Requirement | Low | Moderate | Moderate to High | Low |

| Hands-on Time | Moderate | Low | High | Moderate |

| Cost Per Sample | Low | Moderate | High | High |

| Absolute Quantification | Requires standard curve | Relative only | Relative primarily | Yes (absolute) |

| Turnaround Time | Fast (hours) | Fast | Slow (days) | Moderate |

Direct comparative studies reveal qPCR's particular strengths in validation workflows where target numbers are limited but sample numbers are high. A 2025 comprehensive comparison with nCounter NanoString for copy number alteration analysis in oral cancer demonstrated that while both platforms showed "moderate to substantial agreement" with Cohen's kappa scores, qPCR remained the more robust method for validating genomic biomarkers, with Spearman's rank correlation ranging from r = 0.188 to 0.517 across 24 genes [39]. Notably, the platforms produced divergent prognostic associations for specific genes like ISG15, highlighting how technological differences can influence clinical interpretations.

For whole blood transcriptomic profiling in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) research, qPCR effectively validated RNA-seq findings despite the latter's discovery power. When researchers selected five genes upregulated in ALS (B2M, CAPZA1, RPS18, TNFSF10, TPT1) for qPCR confirmation in an independent cohort, the fold-changes in gene expression observed by qPCR closely matched those identified by RNA-seq, reinforcing qPCR's continued role in orthogonal verification of high-throughput screening results [40].

Analysis of Platform-Specific Advantages and Limitations

qPCR's principal advantage lies in its operational simplicity and cost structure for focused assays, while nCounter NanoString provides superior multiplexing without enzymatic reactions, directly measuring target genes through color-coded reporter probes [39]. RNA-seq offers discovery-level breadth but with substantially higher computational burden and cost per sample. Digital PCR provides absolute quantification without standard curves and enhanced sensitivity for rare targets but with reduced throughput and higher reagent costs.

The "dots in boxes" quality assessment method developed during NEB's Luna qPCR product development captures key performance metrics (PCR efficiency, dynamic range, specificity, precision) as single data points, enabling rapid visualization of multiple targets and conditions. This approach situates optimal performance within a graphical box defined by PCR efficiency of 90-110% and ΔCq (difference between no-template control and lowest template dilution) of ≥3 cycles, with quality scores of 4-5 indicating publication-ready data [38].

Experimental Design for High-Throughput qPCR Applications

Establishing Rigorous Methodological Standards

Table 2: Essential Quality Control Metrics for High-Throughput qPCR

| QC Parameter | Target Value | Calculation Method | Impact on Data Quality |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amplification Efficiency | 90-110% | Standard curve slope: Efficiency = 10^(-1/slope) - 1 | Affects accuracy of quantification |

| Dynamic Range | 5-6 orders of magnitude | Linear regression of Cq vs. log template dilution | Determines usable concentration range |

| Linearity (R²) | ≥0.98 | Coefficient of determination from standard curve | Ensures proportional quantification |

| Precision (CV) | <5% for high abundance | Standard deviation/mean of Cq values | Impacts ability to detect small fold-changes |

| Signal Intensity | RFU consistent across replicates | Visual inspection of amplification curves | Identifies inhibition or pipetting errors |

| Specificity | Single peak in melt curve | Melt curve analysis post-amplification | Confirms target-specific amplification |

Implementation of the Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments (MIQE) guidelines remains critical for generating reliable, reproducible data. The recently published MIQE 2.0 guidelines reinforce this framework, emphasizing that "without methodological rigour, data cannot be trusted" [41]. Key considerations include proper sample handling, reverse transcription optimization, assay validation with efficiency calculations, and appropriate normalization strategies.

Technical and biological replication structures must be carefully planned. Technical replicates (repetitions of the same sample) help estimate system precision and identify outliers, while biological replicates (different samples within the same group) account for population-level variation. In high-throughput designs, triplicate technical replicates represent a common balance between reliability and practical constraints [42].

Reference Gene Validation in Metabolic Research

Housekeeping gene selection requires empirical validation, as commonly used references may demonstrate unexpected variability under specific experimental conditions. A 2025 study evaluating six candidate reference genes (GAPDH, Actb, HPRT, HMBS, 18S, and 36B4) in 3T3-L1 adipocytes treated with L. paracasei supernatants found HPRT and HMBS to be the most stable pair, while the widely used GAPDH and Actb showed significant variability [43]. This highlights the critical importance of experimental validation rather than presumed stability, with recommendations for using a triplet of genes (HPRT, 36B4, and HMBS) for reliable normalization in metabolic studies.

Data Analysis Frameworks for Robust Interpretation

Advanced Analytical Approaches

Traditional 2−ΔΔCT analysis methods are increasingly superseded by more statistically rigorous approaches. Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA) provides greater statistical power and robustness compared to 2−ΔΔCT, with P-values unaffected by variability in qPCR amplification efficiency [15]. This linear modeling approach accommodates multiple experimental variables simultaneously, reducing false positive rates while improving detection sensitivity for small expression changes.

For high-throughput applications, automated analysis pipelines address the particular challenges of large datasets. The "dots in boxes" method represents one such approach, compressing multiple quality metrics into a visual format that facilitates rapid evaluation of numerous targets across conditions [38]. This method incorporates quality scoring (1-5 scale) based on five criteria: linearity, reproducibility, RFU consistency, curve steepness, and curve shape, with penalties applied when established parameters are not met.

Handling Missing Data and Low-Abundance Targets

Data missingness presents particular challenges in qPCR experiments, especially when working with low-abundance targets like circulating miRNAs. A specialized data handling pipeline improves accuracy and precision by categorizing results as "valid, invalid, or undetectable" rather than applying uniform imputation rules [44]. This distinction is critical because missing data due to low concentration (true zeros) require different handling than missing data due to technical failures (missing at random).

The pipeline employs four sequential steps:

- Curve analysis to confirm correct amplification

- Handling replicate measurements using Poisson-derived acceptable Cq ranges

- Categorization based on mean Cq values

- Application of imputation rules based on categorization

This approach prevents the analytical bias that occurs when all missing data are either excluded or uniformly imputed with maximum Cq values, a particular concern in biomarker studies where target abundance may span orders of magnitude across samples [44].

Essential Reagents and Research Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for High-Throughput qPCR

| Reagent/Component | Function | Performance Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Polymerase Master Mix | Enzymatic amplification | Hot-start capability, inhibitor resistance, efficiency |

| Fluorescence Chemistry | Signal generation | SYBR Green vs. hydrolysis probes, multiplexing capacity |