Pharmacophore-Based Virtual Screening for Breast Cancer Targets: A Comprehensive Guide for Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of pharmacophore-based virtual screening (PBVS) and its pivotal role in accelerating the discovery of novel therapeutics for breast cancer.

Pharmacophore-Based Virtual Screening for Breast Cancer Targets: A Comprehensive Guide for Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of pharmacophore-based virtual screening (PBVS) and its pivotal role in accelerating the discovery of novel therapeutics for breast cancer. It covers foundational concepts, from the historical definition of a pharmacophore to the identification of key breast cancer targets like the estrogen receptor and aromatase. The guide details modern methodological workflows, including both structure-based and ligand-based modeling approaches, and explores their successful application in identifying potent inhibitors. It further addresses common troubleshooting and optimization strategies to enhance model quality and screening efficiency. Finally, the article examines validation protocols through case studies that integrate molecular docking, dynamics, and experimental assays, and discusses how PBVS compares with other virtual screening methods. This resource is tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to implement or optimize PBVS in their oncology discovery pipelines.

Understanding Pharmacophores and Key Breast Cancer Targets

The pharmacophore concept stands as a foundational pillar in modern rational drug design, providing an abstract framework to understand and predict molecular recognition between a ligand and its biological target. In the field of breast cancer research, where targeted therapies are increasingly crucial for addressing complex malignancies, pharmacophore-based approaches offer powerful tools for identifying novel therapeutic candidates. According to the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC), a pharmacophore is defined as "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or block) its biological response" [1]. This definition emphasizes the essential molecular features rather than specific chemical structures, enabling medicinal chemists to transcend traditional structural scaffolds in their pursuit of effective therapeutics.

The utility of pharmacophore models is particularly valuable in targeting breast cancer, a disease characterized by molecular heterogeneity and evolving resistance mechanisms. By abstracting key interaction patterns from known active compounds or protein structures, researchers can efficiently screen vast chemical libraries to identify novel scaffolds with potential anticancer activity. This application note traces the historical development of the pharmacophore concept, details its formal definition and features, and presents contemporary protocols for its application in breast cancer drug discovery, complete with specific case studies and practical implementation guidelines.

Historical Development and Conceptual Evolution

The conceptual origins of the pharmacophore date back to the late 19th century when Paul Ehrlich, in his 1898 paper, described "toxophores" as peripheral chemical groups in molecules responsible for binding and eliciting biological effects [2] [3]. Although Ehrlich himself did not use the term "pharmacophore," his contemporaries employed it to describe these essential molecular features, establishing the groundwork for modern receptor theory. For decades, Ehrlich was credited with originating the concept, though this attribution was later challenged by John Van Drie in 2007, who noted that Ehrlich never actually used the term in his writings [2].

The term "pharmacophore" was redefined in 1960 by Frederick W. Schueler, who shifted the emphasis from specific chemical groups to spatial patterns of abstract molecular features [2] [3]. This evolution continued through the work of Lemont B. Kier between 1967 and 1971, which aligned with and ultimately informed the IUPAC's formal definition [4] [2]. This transition from qualitative chemical analogies to quantitative, computer-aided models has positioned the pharmacophore as an indispensable tool in contemporary drug discovery pipelines, particularly for complex diseases like breast cancer where multiple molecular targets may be involved.

Table 1: Historical Evolution of the Pharmacophore Concept

| Time Period | Key Contributor | Conceptual Contribution | Impact on Drug Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| Late 19th Century | Paul Ehrlich | Introduced concept of "toxophores" - chemical groups responsible for biological effects | Laid foundation for structure-activity relationship understanding |

| 1960 | Frederick W. Schueler | Redefined pharmacophore as spatial patterns of abstract features | Shifted focus from specific functional groups to arrangement of molecular features |

| 1967-1971 | Lemont B. Kier | Developed modern 3D pharmacophore concept | Enabled computational approaches to drug design |

| 1998 | IUPAC | Formalized standard definition | Established consistent framework for international research |

The Modern IUPAC Definition and Key Features

The IUPAC definition of a pharmacophore as "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or block) its biological response" represents the current standard for the field [4] [1]. This definition captures several critical aspects: the pharmacophore is an abstract concept rather than a specific molecular structure; it encompasses both steric (three-dimensional arrangement) and electronic characteristics; and its purpose is to facilitate specific molecular interactions that modulate biological function.

Pharmacophore models incorporate distinct structural and physicochemical features that enable molecular recognition. The primary features include:

- Hydrophobic centroids: Regions representing non-polar interactions, often depicted as spheres or volumes encompassing hydrophobic groups [4]

- Aromatic rings: Planar motifs that enable π-π stacking and cation-π interactions [4] [3]

- Hydrogen bond donors/acceptors: Features representing capacity for hydrogen bonding [4] [5]

- Charged groups: Positive or negative ionizable features facilitating electrostatic interactions [4] [3]

These features are arranged in specific three-dimensional patterns with defined spatial relationships (distances, angles) and tolerance ranges to account for molecular flexibility [3]. The combination and arrangement of these abstract features define the essential molecular interaction capabilities required for biological activity, independent of the underlying chemical scaffold.

Pharmacophore Modeling in Breast Cancer Research: Case Studies

Application in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer (TNBC) Therapeutics

In triple-negative breast cancer, characterized by aggressive behavior and limited treatment options, pharmacophore approaches have been employed to target critical protein-protein interactions. Recent research has focused on disrupting the MKK3-MYC interaction, a key regulatory axis in TNBC pathogenesis [6]. Researchers implemented a dynamic structure-based pharmacophore modeling strategy that incorporated steered molecular dynamics simulations to account for protein flexibility. This approach enabled virtual screening of over 2 million compounds from ChemDiv and Enamine libraries, identifying 16,766 initial hits that were subsequently refined through docking and molecular dynamics analyses [6].

The top-ranked compounds Z332428622, 4476-2273, and 4292-0516 demonstrated stronger binding affinities and mechanical stability compared to the reference inhibitor SGI-1027, making them promising candidates for further development as TNBC therapeutics [6]. This case study illustrates how advanced pharmacophore methodologies can address challenging targets like protein-protein interactions that are increasingly recognized as important in cancer biology but difficult to drug with conventional approaches.

Targeting the Adenosine A1 Receptor in Breast Cancer

A comprehensive study integrating bioinformatics and computational chemistry approaches identified the adenosine A1 receptor as a promising target for breast cancer treatment [7]. Researchers constructed a pharmacophore model based on binding information from molecular docking and dynamics simulations, which then guided the virtual screening of additional compounds. This approach led to the rational design and synthesis of a novel molecule (Molecule 10) that exhibited potent antitumor activity against MCF-7 breast cancer cells with an IC₅₀ value of 0.032 µM, significantly outperforming the positive control 5-FU (IC₅₀ = 0.45 µM) [7].

The success of this study demonstrates the power of pharmacophore-based screening for identifying novel chemotypes with optimized biological activity, particularly in the context of breast cancer where targeting specific receptor subtypes may yield enhanced therapeutic efficacy with reduced side effects.

Table 2: Representative Breast Cancer Targets Addressed Through Pharmacophore Approaches

| Molecular Target | Breast Cancer Subtype | Pharmacophore Approach | Key Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| MKK3-MYC PPI Interface | Triple-Negative Breast Cancer (TNBC) | Dynamic structure-based pharmacophore modeling with steered MD | Identified compounds with superior binding affinity vs. reference inhibitor |

| Adenosine A1 Receptor | MCF-7 (ER+) | Ligand-based pharmacophore from active compounds | Designed novel molecule with IC₅₀ = 0.032 µM |

| FGFR1 | FGFR1-amplified breast cancers | Multi-ligand consensus pharmacophore model | Identified novel inhibitors with improved selectivity profiles |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol 1: Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Model Development

Purpose: To generate a pharmacophore hypothesis from a set of known active ligands when the 3D structure of the biological target is unavailable, particularly relevant for breast cancer targets with unknown structures.

Materials and Reagents:

- Set of structurally diverse active compounds (15-30 molecules with known IC₅₀ or Ki values)

- Inactive compounds (for model validation)

- Computational software: MOE, Catalyst/Discovery Studio, or Phase

- Hardware: Workstation with multi-core processor, 16+ GB RAM, dedicated graphics card

Procedure:

Training Set Selection: Curate a structurally diverse set of 15-30 active compounds against the breast cancer target of interest, ensuring a range of potencies (ideally spanning 2-3 orders of magnitude). Include known inactive compounds to enhance model specificity [4] [8].

Conformational Analysis: For each compound in the training set, generate a comprehensive set of low-energy conformations using appropriate algorithms (e.g., systematic search, stochastic methods). Ensure adequate coverage of conformational space by setting energy thresholds typically 10-15 kcal/mol above the global minimum [4].

Molecular Superimposition: Systematically superimpose all combinations of low-energy conformations across the training set compounds. Identify the set of conformations (one from each active molecule) that yields the best spatial overlap of common functional groups, presuming this represents the bioactive conformation [4].

Feature Abstraction: Transform the superimposed molecular structures into an abstract representation by replacing specific functional groups with pharmacophore features (e.g., hydroxy groups → hydrogen-bond donor/acceptor, phenyl rings → aromatic ring feature) [4].

Model Validation: Validate the pharmacophore hypothesis by screening a test set of known active and inactive compounds. Quantitative validation metrics should include:

Protocol 2: Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling for Breast Cancer Targets

Purpose: To develop a pharmacophore model directly from the 3D structure of a protein-ligand complex, applicable when crystal structures of breast cancer targets are available.

Materials and Reagents:

- Protein Data Bank (PDB) structure of target protein (e.g., FGFR1, estrogen receptor)

- Co-crystallized ligand(s) or known active compounds

- Computational tools: LigandScout, MOE, Structure-Based Focusing module in Schrödinger

- High-performance computing resources for molecular dynamics simulations (optional)

Procedure:

Protein Preparation: Obtain the 3D structure of the target protein from PDB. For breast cancer targets, structures may include FGFR1 (PDB: 4ZSA), estrogen receptor variants, or other relevant oncogenic proteins. Process the structure using protein preparation workflows to add hydrogen atoms, assign proper bond orders, optimize side-chain orientations, and perform energy minimization [9].

Binding Site Analysis: Define the binding pocket around the co-crystallized ligand or through binding site detection algorithms. Identify key residues involved in molecular recognition and catalytic activity if applicable.

Interaction Analysis: Map the specific interactions between the protein and bound ligand, including:

- Hydrogen bonds (donors and acceptors)

- Hydrophobic contact regions

- Ionic and cation-π interactions

- Aromatic stacking geometries [5]

Feature Generation: Translate the identified interactions into pharmacophore features with specific geometric constraints (distances, angles, tolerance radii). For kinase targets common in breast cancer (e.g., FGFR1), include features representing hinge-binding motifs, hydrophobic pockets, and specificity regions [9].

Model Refinement with Dynamics: For enhanced accuracy, perform molecular dynamics simulations (50-100 ns) of the protein-ligand complex to account for flexibility. Extract multiple snapshots to create a dynamic pharmacophore model that captures essential interactions across conformational ensembles [6].

Virtual Screening Application: Employ the validated pharmacophore model to screen large compound libraries (e.g., ZINC, PubChem, in-house collections). Apply filtering criteria based on feature matching complemented by docking studies and binding free energy calculations (MM/GBSA) to prioritize hits for experimental validation [10] [9].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Pharmacophore Modeling

| Category | Specific Tools/Resources | Function/Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Software Platforms | MOE, Schrödinger Suite, Catalyst/Discovery Studio, LigandScout | Pharmacophore model development, visualization, and screening | Comprehensive computational environment for model building and validation |

| Compound Libraries | PubChem, ZINC, ChemDiv, Enamine, TargetMol Anticancer Library | Sources of compounds for virtual screening | Diverse chemical space for hit identification; TargetMol specifically useful for cancer targets |

| Protein Structures | Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Source of 3D structural information for structure-based approaches | Essential for structure-based pharmacophore modeling |

| Target Prediction | SwissTargetPrediction | Predicting potential protein targets for compounds | Understanding polypharmacology in complex breast cancer signaling networks |

| Validation Tools | ROC curve analysis, Enrichment calculations, MD simulation packages (GROMACS, AMBER) | Assessing model quality and predictive power | Critical for establishing model reliability before experimental investment |

| ADMET Prediction | Molinspiration, admetSAR, PreADMET | Predicting absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity | Early assessment of drug-likeness for hit compounds |

The pharmacophore concept has evolved significantly from Ehrlich's initial observations to a sophisticated, computationally-driven framework central to modern drug discovery. The IUPAC definition provides a standardized conceptual foundation that emphasizes the ensemble of essential steric and electronic features required for molecular recognition, independent of specific chemical scaffolds. In breast cancer research, where targeted therapies are paramount, pharmacophore-based approaches have demonstrated considerable utility in identifying novel chemotypes against challenging targets, including protein-protein interfaces and receptor tyrosine kinases.

The protocols outlined in this application note provide practical methodologies for implementing both ligand-based and structure-based pharmacophore strategies in breast cancer drug discovery pipelines. As computational power continues to grow and structural databases expand, pharmacophore modeling will likely play an increasingly prominent role in the development of precise, effective therapeutics for breast cancer subtypes, ultimately contributing to improved patient outcomes in this complex disease landscape.

Critical Breast Cancer Molecular Targets for Virtual Screening

Breast cancer remains a major global health challenge, with its molecular heterogeneity necessitating the discovery of novel therapeutic targets. Pharmacophore-based virtual screening has emerged as a powerful computational approach to identify potential drug candidates by targeting key molecular drivers of breast carcinogenesis. This application note provides a comprehensive overview of critically relevant molecular targets for breast cancer, supported by structured quantitative data, detailed experimental protocols, and essential visualization tools to guide researchers in rational drug design.

Extensive research has identified several high-value molecular targets for breast cancer therapeutic development. The table below summarizes five critical targets with their quantitative binding profiles and functional significance.

Table 1: Critical Breast Cancer Molecular Targets for Virtual Screening

| Target | Biological Significance | Exemplary Compounds | Reported Binding Affinity/IC₅₀ | Cellular Assay Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adenosine A1 Receptor | Key candidate from intersection analysis; regulates cancer cell proliferation | Molecule 10 | LibDock Score: 148.673 [11] | IC₅₀: 0.032 µM (MCF-7 cells) [11] |

| HER2 Kinase Domain | Receptor tyrosine kinase; overexpression drives aggressive BC subtypes | Ibrutinib (for L755S mutant) | MM-PBSA: Most negative binding energy [12] | Preferential anti-proliferative effects on HER2+ cells [13] |

| Aromatase (CYP19A1) | Catalyzes estrogen synthesis; key for ER+ BC | CMPND 27987 (Marine Natural Product) | Docking: -10.1 kcal/mol; MM-GBSA: -27.75 kcal/mol [14] | Effective in postmenopausal BC models [14] |

| EGFR | Epidermal growth factor receptor; mutated in various cancers | ZINC103239230 | Docking: -9.5 kcal/mol [15] | Induced 30.8% apoptosis in MCF-7 [15] |

| MKK3-MYC PPI | Protein-protein interaction in TNBC signaling | Z332428622 | Stronger binding affinity vs. reference [6] | Disrupts oncogenic signaling in TNBC models [6] |

These targets represent diverse biological pathways and cancer subtypes, providing multiple strategic options for therapeutic intervention. The adenosine A1 receptor has recently emerged as a particularly promising candidate, with Compound 5 demonstrating exceptional binding stability (LibDock Score: 148.673) and the newly designed Molecule 10 showing remarkable potency in cellular assays (IC₅₀: 0.032 µM) [11].

Experimental Protocols

Comprehensive Virtual Screening Workflow

Objective: To identify novel lead compounds against breast cancer targets through integrated computational screening. Materials:

- Target protein structures (PDB IDs: 7LD3, 3EQM, 6JXT, 3RCD)

- Compound libraries (ChemDiv, Enamine, CMNPD, Natural Products)

- Software: Schrödinger Suite, VMD, GROMACS, LigandScout

Procedure:

- Target Preparation

- Obtain crystal structure from PDB database

- Remove co-crystallized ligands and water molecules >5Å from active site

- Add hydrogen atoms and optimize hydrogen bonding network

- Perform restrained minimization using OPLS3/OPLS4 force field (RMSD: 0.3Å) [13]

Pharmacophore Modeling

- For structure-based: Use LigandScout to identify key interaction features from protein-ligand complexes [15]

- For ligand-based: Generate conformers for training set compounds (Best Settings, 100 conformers)

- Define pharmacophore features: H-bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions, aromatic rings, ionizable groups

- Merge and optimize pharmacophore hypotheses [14]

Virtual Screening

- Prepare ligand library using LigPrep (ionization at pH 7.0±0.5, generate stereoisomers)

- Perform high-throughput virtual screening (HTVS) using Glide

- Select top 10,000 compounds for standard precision (SP) docking

- Refine top 500 hits with extra precision (XP) docking [13]

- Apply filters: docking score ≤ -6.00 kcal/mol, Lipinski's Rule of Five compliance

Molecular Dynamics Validation

- Set up system using GROMACS: solvate in water box, add ions for neutralization

- Energy minimization: steepest descent algorithm (5000 steps)

- Equilibration: NVT (100 ps) and NPT (100 ps) ensembles

- Production run: 100-1000 ns at 300K [12]

- Analyze RMSD, RMSF, hydrogen bonds, and binding energy (MM-GBSA/PBSA)

Advanced Binding Validation Protocol

Steered Molecular Dynamics (sMD) for Binding Stability Assessment:

- Apply external forces to ligand-protein complex (1000-2000 pN/s)

- Pull ligand along reaction coordinate away from binding site

- Monitor work values and rupture events

- Combine with MM-GBSA for correlation analysis [6]

Binding Free Energy Calculations:

- Extract snapshots from MD trajectory (every 100 ps)

- Calculate binding free energy using MM-GBSA/PBSA method: ΔGbind = Gcomplex - (Gprotein + Gligand)

- Decompose energy contributions per residue [6]

Signaling Pathways & Experimental Workflows

Critical Breast Cancer Signaling Pathways

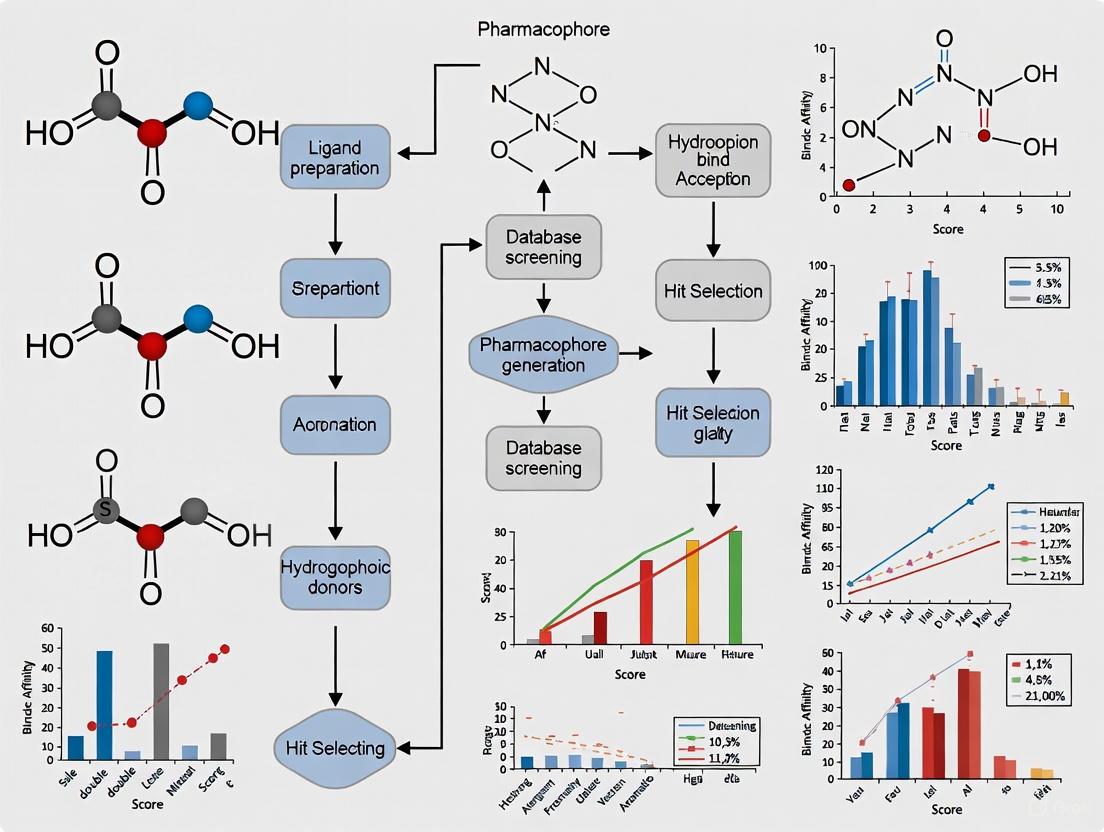

Diagram 1: Critical Breast Cancer Signaling Pathways (76 characters)

Integrated Virtual Screening Workflow

Diagram 2: Pharmacophore Virtual Screening Workflow (53 characters)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Breast Cancer Virtual Screening

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Purpose | Exemplary Sources/Details |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Structures | Molecular docking and dynamics simulations | PDB IDs: 7LD3 (Adenosine A1), 3EQM (Aromatase), 6JXT (EGFR), 3RCD (HER2) [11] [14] [13] |

| Compound Libraries | Source of potential lead compounds | ChemDiv, Enamine, CMNPD (Marine Natural Products), Commercial NP databases [14] [6] |

| Docking Software | Protein-ligand interaction prediction | Schrödinger Glide (HTVS/SP/XP), CHARMM, Discovery Studio [11] [13] |

| MD Simulation Tools | Binding stability assessment | GROMACS, AMBER, Desmond [11] [12] |

| Pharmacophore Modeling | Key interaction feature identification | LigandScout, Schrödinger Phase [14] [15] |

| Cell Lines | In vitro validation of candidate compounds | MCF-7 (ER+), MDA-MB-231 (TNBC), HER2-overexpressing lines [11] [13] |

This application note outlines a comprehensive framework for targeting critical molecular drivers in breast cancer through pharmacophore-based virtual screening. The integration of multi-omics data, advanced computational methods, and systematic experimental validation provides a robust platform for accelerating the discovery of novel therapeutic agents. The protocols and resources detailed herein offer researchers a structured approach to identify and optimize lead compounds with improved potency and selectivity against high-value breast cancer targets.

The Role of Pharmacophore Models in Modern Computer-Aided Drug Discovery (CADD)

The concept of the pharmacophore, defined by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) as "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or to block) its biological response", serves as a foundational pillar in modern computer-aided drug discovery (CADD) [16]. This abstract representation of molecular interactions enables researchers to transcend specific chemical scaffolds and focus on the essential steric and electronic features responsible for biological activity, including hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions, charged groups, and aromatic interactions [16]. In the context of breast cancer research, where targeted therapies are paramount, pharmacophore models provide a strategic framework for identifying novel compounds that specifically interact with key proteins involved in cancer progression, such as hormone receptors and metabolic enzymes [11] [17].

The implementation of pharmacophore-based approaches has become increasingly sophisticated, with current methodologies seamlessly integrating both ligand-based and structure-based design strategies [16]. This integration is particularly valuable in breast cancer drug discovery, where resistance to existing therapies remains a significant challenge and the identification of new chemotypes with activity against established targets is urgently needed [17] [18]. By capturing the critical interaction patterns necessary for target engagement, pharmacophore models serve as efficient virtual filters that can rapidly prioritize compounds from large chemical databases with a higher probability of biological activity, thereby accelerating the early stages of drug discovery campaigns [16].

Theoretical Foundations and Methodology

Pharmacophore Model Generation Approaches

The development of pharmacophore models follows two principal methodologies, each with distinct advantages and applications in drug discovery research:

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling: This approach derives pharmacophore features directly from experimentally determined ligand-target complexes, typically obtained from X-ray crystallography or NMR spectroscopy and available through repositories like the Protein Data Bank [16]. The process involves analyzing the three-dimensional structure of a protein-ligand complex to identify key interaction points between the ligand and amino acid residues in the binding pocket. These interactions are then translated into abstract pharmacophore features representing hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic contacts, charged interactions, and aromatic rings. Advanced implementations of this method can also generate models based solely on binding site topology without a co-crystallized ligand, using the protein's active site residues to define potential interaction points [16]. Additionally, computationally derived ligand-target complexes from molecular docking studies can serve as input for structure-based pharmacophore generation, sometimes refined further through molecular dynamics simulations to account for protein flexibility [16].

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling: When structural information about the target protein is unavailable, ligand-based approaches provide a powerful alternative. This method involves identifying common chemical features shared by a set of known active molecules through three-dimensional alignment [16]. The process begins with conformational analysis of training set compounds to explore their accessible three-dimensional space. Subsequently, molecular alignment algorithms identify the optimal spatial overlay that maximizes the shared pharmacophore features across the active compounds. The resulting model represents the essential steric and electronic features conserved among structurally diverse actives, presumed critical for target engagement and biological activity [16]. The quality and structural diversity of the training set molecules significantly influence model effectiveness, with carefully curated datasets containing confirmed actives yielding more predictive models.

Model Validation and Quality Metrics

Before deployment in virtual screening campaigns, pharmacophore models must undergo rigorous validation to assess their ability to distinguish active from inactive compounds. This process involves testing the model against a benchmarking dataset containing known active molecules and decoys (presumed inactives with similar physicochemical properties) [16]. Several quality metrics are employed to evaluate model performance:

- Enrichment Factor (EF): Measures the enrichment of active molecules in the virtual hit list compared to random selection [16].

- Yield of Actives: Represents the percentage of active compounds retrieved in the virtual hit list [16].

- Specificity and Sensitivity: Assess the model's ability to exclude inactive compounds and identify active molecules, respectively [16].

- ROC-AUC Analysis: The Area Under the Curve of the Receiver Operating Characteristic plot provides a comprehensive measure of model performance across all classification thresholds [16].

Theoretical validation ensures that the pharmacophore model possesses sufficient discriminatory power to identify novel bioactive compounds while minimizing false positives, thereby increasing the efficiency of subsequent experimental testing [16].

Application Notes: Pharmacophore-Based Virtual Screening for Breast Cancer Targets

Case Study 1: Targeting the Adenosine A1 Receptor in Breast Cancer

A 2025 study demonstrated the application of integrated pharmacophore modeling to identify critical therapeutic targets and design potent antitumor compounds for breast cancer treatment [11]. The research employed a comprehensive approach combining bioinformatics and computational chemistry to identify the adenosine A1 receptor as a promising target. Following target identification, researchers conducted molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulations to evaluate binding stability with the human adenosine A1 receptor-Gi2 protein complex (PDB ID: 7LD3) [11].

The workflow involved constructing a pharmacophore model based on binding information to guide virtual screening of additional compounds [11]. This model facilitated the identification of compounds with stable binding properties, which subsequently informed the rational design and synthesis of a novel molecule (Molecule 10) [11]. Experimental validation revealed that this newly designed compound exhibited potent antitumor activity against MCF-7 breast cancer cells with an IC~50~ value of 0.032 μM, significantly outperforming the positive control 5-FU (IC~50~ = 0.45 μM) [11]. This case study highlights how pharmacophore-based approaches can directly contribute to the development of highly effective therapeutic candidates for breast cancer treatment.

Case Study 2: Discovery of Marine-Derived Aromatase Inhibitors

Breast cancer treatment, particularly for hormone-receptor-positive subtypes, often involves aromatase inhibitors (AIs) to block estrogen synthesis [17]. A 2024 study focused on identifying novel marine-derived aromatase inhibitors to address challenges such as drug resistance and side effects associated with current AIs [17]. The research combined ligand-based and structure-based pharmacophore models for virtual screening against the Comprehensive Marine Natural Products Database (CMNPD) [17].

The ligand-based model was derived from a series of novel, non-steroidal AIs with an azole group at the 3rd position in a 2-phenyl indole scaffold, while the structure-based model utilized docking-assisted methodology based on the human aromatase enzyme (PDB ID: 3EQM) [17]. Through virtual screening of over 31,000 compounds, researchers identified 1,385 potential candidates, with only four compounds passing stringent binding affinity criteria [17]. The top candidate, CMPND 27987, demonstrated the highest binding affinity (-10.1 kcal/mol) and exhibited superior stability at the protein's active site in molecular dynamics simulations, with an MM-GBSA free binding energy of -27.75 kcal/mol [17]. This study illustrates the power of integrated pharmacophore approaches to identify novel natural product-derived inhibitors with potential applications in breast cancer therapy.

Case Study 3: Optimization of Estrogen Receptor Beta Binders

A recent study focused on optimizing estrogen receptor beta (ERβ) binders for hormone-dependent breast cancers through pharmacophore pattern identification [19]. Researchers developed an e-QSAR model with excellent predictive accuracy (R²tr = 0.799, Q²LMO = 0.792, CCCex = 0.886) that also provided mechanistic insights into critical pharmacophore features [19]. Analysis revealed that atoms with sp²-hybridization, particularly carbon and nitrogen atoms, significantly impact binding profiles along with lipophilic atoms [19]. Additionally, specific combinations of hydrogen bond donors and acceptors involving carbon, nitrogen, and ring sulfur atoms played crucial roles in target engagement [19].

The study integrated multiple computational approaches, including molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulations, which provided consensus and complementary results to the pharmacophore analysis [19]. This multi-faceted approach enabled the identification of both reported and novel ERβ binders, with the structural insights offering valuable guidance for future drug development campaigns targeting estrogen receptor beta in breast cancer therapy [19].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling for Breast Cancer Targets

This protocol outlines the steps for creating a structure-based pharmacophore model targeting breast cancer-related proteins, such as the adenosine A1 receptor or aromatase enzyme [11] [17].

Step 1: Protein Structure Preparation

- Obtain the three-dimensional structure of the target protein from the Protein Data Bank (PDB)

- Perform necessary preprocessing steps: remove crystallographic water molecules (except catalytic waters), add hydrogen atoms, and assign appropriate protonation states to amino acid residues at physiological pH

- Energy minimization may be performed to relieve steric clashes using molecular mechanics force fields

Step 2: Binding Site Definition

- Identify the binding pocket using automated binding site detection tools or manual selection based on known ligand binding locations

- Define the active site by selecting residues within a specific radius (typically 5-10 Å) from the co-crystallized ligand or predicted binding site

Step 3: Pharmacophore Feature Extraction

- Use pharmacophore modeling software (e.g., LigandScout, Discovery Studio, MOE) to automatically generate potential pharmacophore features based on protein-ligand interactions or binding site properties

- Manually curate features to include only those critical for binding: hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions, charged/ionizable groups, and aromatic rings

Step 4: Exclusion Volume Assignment

- Add exclusion volumes to represent steric constraints of the binding pocket, preventing compounds with unfavorable steric clashes from mapping to the model

- Adjust exclusion volume sizes based on the van der Waals radii of protein atoms lining the binding site

Step 5: Model Validation

- Validate the model using known active and inactive compounds for the target

- Calculate enrichment factors and other quality metrics to ensure model robustness before proceeding to virtual screening

Protocol 2: Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling for Breast Cancer Targets

This protocol describes the creation of a ligand-based pharmacophore model when structural information about the target protein is limited or unavailable [17] [16].

Step 1: Training Set Compilation

- Curate a diverse set of known active compounds (typically 10-20 molecules) with confirmed biological activity against the target

- Ensure structural diversity while maintaining consistent mechanism of action

- Include experimentally determined IC~50~ or K~i~ values, with preference for compounds exhibiting high potency (typically < 1 μM)

Step 2: Conformational Analysis

- Generate representative conformational ensembles for each training set compound using appropriate algorithms (e.g., stochastic search, systematic torsion driving)

- Apply energy window (typically 10-20 kcal/mol) and RMSD criteria (0.5-1.0 Å) to ensure coverage of biologically relevant conformations

Step 3: Molecular Alignment and Common Feature Identification

- Perform flexible alignment to identify the optimal spatial overlay of training set compounds that maximizes shared pharmacophore features

- Identify common chemical features conserved across the aligned active compounds

- Define feature tolerances based on the spatial variance observed in the alignment

Step 4: Model Generation and Refinement

- Generate initial pharmacophore hypotheses using automated algorithms (e.g., HipHop, Common Feature Approach)

- Refine models by adjusting feature definitions, weights, and tolerances based on known structure-activity relationships

- Optional: Define some features as optional if not all active compounds contain them

Step 5: Model Selection and Validation

- Select the best model based on its ability to discriminate between known active and inactive compounds

- Validate using external test sets not included in model generation

- Calculate statistical parameters (e.g., ROC curves, enrichment factors) to quantify model performance

Protocol 3: Integrated Pharmacophore-Based Virtual Screening

This protocol outlines a comprehensive virtual screening workflow combining multiple pharmacophore approaches for identifying novel breast cancer therapeutics [11] [17].

Step 1: Database Preparation

- Select appropriate chemical databases for screening (e.g., CMNPD for natural products, ZINC, DrugBank, or in-house corporate libraries)

- Preprocess compounds: generate 3D structures, tautomers, and stereoisomers; perform energy minimization; filter based on drug-like properties (Lipinski's Rule of Five)

Step 2: Parallel Pharmacophore Screening

- Screen the preprocessed database against multiple validated pharmacophore models (both structure-based and ligand-based)

- Use flexible fitting algorithms to account for ligand conformational flexibility during screening

- Set appropriate feature mapping criteria (typically requiring mapping of 70-100% of essential features)

Step 3: Hit Selection and Diversity Analysis

- Select compounds that successfully map to pharmacophore models

- Apply additional filters: drug-likeness, absence of toxicophores, synthetic accessibility

- Cluster hits based on chemical structure to ensure structural diversity in selected compounds

Step 4: Molecular Docking Validation

- Perform molecular docking of selected hits into the target protein binding site

- Use appropriate docking software (e.g., AutoDock Vina, GOLD, Glide) with validated protocols

- Select poses based on docking scores and conservation of critical pharmacophore interactions

Step 5: Binding Affinity Refinement

- Submit top-ranked docked complexes to molecular mechanics-based binding free energy calculations (MM-GBSA/PBSA)

- Perform molecular dynamics simulations (100 ns or longer) to assess complex stability and interaction persistence

- Select final candidates based on consensus from multiple computational approaches

Visualization of Workflows and Signaling Pathways

Pharmacophore Modeling and Virtual Screening Workflow

Estrogen Receptor Signaling in Breast Cancer and AI Targeting

Table 1: Computational Tools and Software for Pharmacophore Modeling

| Tool/Software | Application in Pharmacophore Modeling | Key Features | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| LigandScout | Structure-based & ligand-based model generation | Automated feature extraction from protein-ligand complexes; virtual screening capabilities | [17] [16] |

| Discovery Studio | Comprehensive drug discovery suite | Pharmacophore modeling, virtual screening, QSAR analysis | [11] [16] |

| Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) | Molecular modeling and simulation | Integrated pharmacophore modeling, docking, and molecular dynamics | [10] [16] |

| AutoDock Vina | Molecular docking | Binding pose prediction for structure-based pharmacophore modeling | [17] |

| GROMACS | Molecular dynamics simulations | Assessment of binding stability and interaction persistence | [11] |

Table 2: Key Databases for Breast Cancer Target Research

| Database | Content Type | Application in Breast Cancer Research | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | 3D protein structures | Source of target structures for structure-based pharmacophore modeling | [17] [16] |

| Comprehensive Marine Natural Products Database (CMNPD) | Marine natural products | Source of novel chemical diversity for virtual screening | [17] |

| SwissTargetPrediction | Target prediction | Identification of potential protein targets for compounds | [11] |

| PubChem Bioassay | Bioactivity data | Source of active and inactive compounds for model validation | [16] |

| ChEMBL | Bioactive molecules | Curated bioactivity data for training set compilation | [16] |

Table 3: Experimental Validation Resources for Breast Cancer Targets

| Resource | Type | Application | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| MCF-7 cell line | ER+ breast cancer cells | In vitro validation of anti-proliferative activity | [11] |

| MDA-MB cell line | Triple-negative breast cancer cells | Assessment of activity against aggressive subtypes | [11] |

| Molecular dynamics simulations | Computational validation | Assessment of binding stability and interaction analysis | [11] [10] |

| MM-GBSA/PBSA | Binding free energy calculation | Quantitative assessment of binding affinity | [17] |

Pharmacophore modeling represents an indispensable component of modern CADD, particularly in the complex landscape of breast cancer drug discovery. By abstracting specific molecular structures into essential interaction features, pharmacophore models enable efficient exploration of chemical space and facilitate the identification of novel chemotypes with desired biological activities [16]. The integration of structure-based and ligand-based approaches, complemented by molecular docking and dynamics simulations, creates a powerful framework for addressing challenges in breast cancer therapy, including drug resistance and off-target effects [11] [17].

The continued evolution of pharmacophore methodologies, coupled with advances in computational power and algorithmic sophistication, promises to further enhance their predictive accuracy and application scope. As breast cancer research increasingly focuses on personalized medicine and targeted therapies, pharmacophore-based strategies offer the flexibility to address diverse molecular targets and patient-specific mutations [18]. By serving as a conceptual bridge between chemical structure and biological activity, pharmacophore modeling will remain a cornerstone of rational drug design efforts aimed at developing more effective and selective therapeutics for breast cancer patients.

Breast cancer treatment has been revolutionized by targeting specific molecular pathways. Among the most significant targets are estrogen receptors (ERs), the aromatase enzyme, and emerging protein targets that offer new therapeutic opportunities. Estrogen receptor-positive (ER+) breast cancer constitutes approximately 75% of all breast cancer cases, making therapeutic intervention against estrogen signaling a cornerstone of treatment [20]. Two primary pharmacological strategies have been employed: endocrine therapy using selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) that act as ER antagonists, and aromatase inhibitors (AIs) that disrupt exogenous estrogen synthesis [17]. Aromatase, a member of the cytochrome P450 family (CYP450), catalyzes the rate-limiting step in estrogen biosynthesis through aromatization of androgen precursors [17]. Despite the effectiveness of current therapies, challenges such as drug resistance, long-term side effects including cognitive decline and osteoporosis, and toxicity concerns necessitate the discovery of novel inhibitors [17] [20]. Computational approaches, particularly pharmacophore-based virtual screening, have emerged as powerful tools for identifying new therapeutic candidates with improved efficacy and safety profiles.

Computational Workflow for Target Identification and Validation

The discovery of novel therapeutic agents for breast cancer involves a multi-stage computational and experimental workflow that integrates target identification, virtual screening, and experimental validation. The following diagram illustrates this integrated approach:

Estrogen Receptors: Pharmacophore Modeling and Selective Targeting

Biology and Signaling Pathways

Estrogen receptors exist in two main subtypes: ERα and ERβ, which belong to the nuclear receptor superfamily. Despite significant sequence homology, these receptors have notable differences in tissue distribution and function. ERα is predominantly expressed in bone, breast, prostate, uterus, ovary, and brain, while ERβ is typically present in ovary, bladder, colon, immune, cardiovascular, and nervous systems [21]. ERα mediates the classic proliferative functions of estrogen, whereas ERβ activation often produces anti-proliferative effects that oppose ERα actions in reproductive tissues [21]. The activation mechanism involves ligand binding, receptor dimerization, and regulation of target gene expression.

Computational Protocols for ER-Targeted Discovery

Shared Feature Pharmacophore Modeling

Recent advances have enabled the development of subtype-specific pharmacophore models capable of capturing selective ligands. A robust protocol for generating shared feature pharmacophore models involves:

- Protein Structure Retrieval: Collect high-resolution crystal structures of wild-type and mutant ER proteins from the Protein Data Bank. Filter structures using specific criteria: Homo sapiens source organism, X-ray diffraction method, and refinement resolution of 2.0-2.5 Å [22].

- Structure-Based Pharmacophore Generation: For each protein-ligand complex, use software such as LigandScout to construct individual pharmacophores identifying key features including hydrogen bond donors (HBD), hydrogen bond acceptors (HBA), hydrophobic regions (HyPho), and aromatic moieties (Ar) [22].

- Shared Feature Model Construction: Incorporate individual pharmacophores into an alignment module to generate a consolidated shared feature pharmacophore (SFP) model. A recently developed SFP for mutant ESR2 proteins contained HBD: 2, HBA: 3, HPho: 3, Ar: 2, and halogen bond donors (XBD): 1, totaling 11 features [22].

- Feature Combination Generation: Use Python scripts to distribute features using permutation formulas. For a model with 11 features, this can generate 336 unique combinations for comprehensive virtual screening [22].

Virtual Screening and Validation

- Database Screening: Employ the pharmacophore model to screen commercial databases (e.g., Maybridge, Enamine) using platforms such as ZINCPharmer or Discovery Studio [21].

- Structure-Based Refinement: Subject top-ranked compounds to molecular docking against ER crystal structures (e.g., PDB: 1X78) using standard precision protocols [21].

- Binding Affinity Estimation: Apply MM-GBSA methods to estimate binding affinity and conduct visual analysis of binding modes [21].

- Biological Validation: Test selected compounds using yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) assays for activity and selectivity profiling, followed by luciferase reporter assays to measure transcriptional activity [21].

Research Reagent Solutions for ER-Targeted Discovery

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents for Estrogen Receptor Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Specifications/Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Structures | Molecular docking and structure-based design | PDB IDs: 2FSZ, 7XVZ, 7XWR (mutant ESR2); 1QKM (wild-type) [22] |

| Chemical Databases | Source compounds for virtual screening | Maybridge, Enamine, ZINC [22] [21] |

| Pharmacophore Software | Model development and virtual screening | LigandScout, ZINCPharmer, Discovery Studio [22] [21] |

| Yeast Two-Hybrid System | Detect ligand activity and selectivity | AH109 yeast strain with pGADT7-SRC1 and pGBKT7-ER LBD plasmids [21] |

| Reporter Assay System | Measure ER transcriptional activity | CHO-K1 cells, pGL2-ERE3-luc reporter, pRL-SV40 control [21] |

Aromatase Enzyme: Structure-Based Inhibitor Design

Biological Function and Therapeutic Significance

Aromatase (CYP19A1) is a microsomal cytochrome P450 enzyme that catalyzes the conversion of androgens (androstenedione and testosterone) to estrogens (estrone and estradiol). This conversion represents the final and rate-limiting step in estrogen biosynthesis, making aromatase a critical therapeutic target for hormone-dependent breast cancers [17]. In postmenopausal women, where ovarian estrogen production has ceased, peripheral aromatization in adipose tissues becomes the primary source of estrogen, and its inhibition has proven effective in regulating the regression of estrogen-dependent breast tumors [17]. Aromatase inhibitors are classified into two types: Type I (steroidal) inhibitors that mimic the natural substrate and bind irreversibly, and Type II (non-steroidal) inhibitors that coordinate with the heme iron atom in the enzyme's active site and bind reversibly [17].

Integrated Protocol for Aromatase Inhibitor Discovery

Combined Pharmacophore Screening Strategy

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling:

- Select a training set of known active compounds (e.g., 18 non-steroidal AIs with 2-phenyl indole scaffolds) [17].

- Sketch compounds in MarvinSketch and minimize 3D coordinates using Merck Molecular Force Field (MMFF94).

- Use LigandScout to divide compounds into training and test sets (e.g., 14:4 ratio) and perform conformational analysis with best settings and 100 conformers [17].

- Generate ligand-based pharmacophore using pharmacophore fit and atom overlap scoring function.

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling:

- Obtain aromatase crystal structure (PDB: 3EQM, 2.90 Å resolution) from Protein Data Bank [17].

- Prepare protein by removing co-crystallized ligand, adding hydrogens, and conserving catalytic water molecules.

- Perform molecular docking of reference compound (e.g., Compound 6 from literature) using AutoDock Vina with defined box parameters (size: 16, 20, 16; center: 85.1, 51.016, 43.076; exhaustiveness: 100) [17].

- Create structure-based pharmacophore based on docking pose with azaheterocyclic ring oriented toward heme center.

Pharmacophore Merging and Screening:

- Align ligand-based and structure-based models using alignment module in LigandScout.

- Merge common pharmacophoric attributes to create a unified model [17].

- Screen databases (e.g., Comprehensive Marine Natural Products Database) using the merged pharmacophore with parameters: maximum 2 omitted features, volume exclusion.

Molecular Docking and Dynamics Validation

Molecular Docking Protocol:

- Prepare protein structure by removing native ligand, adding polar hydrogens, and calculating Kollman charges.

- Define active site using grid box centered on crystallized ligand location.

- Dock potential hits using AutoDock Vina with exhaustiveness setting of 100 [17].

- Select compounds based on binding affinity and key interactions with heme group and active site residues.

Molecular Dynamics Simulations:

- Perform MD simulations using GROMACS with AMBER99SB-ILDN force field for protein and GAFF for ligands [7].

- Solvate system in TIP3P water model in a cubic box with minimum 0.8-1.0 nm distance to boundary.

- Add ions to neutralize system and conduct energy minimization followed by equilibration.

- Run production MD for 15-200 ns at 298.15 K and 1 bar pressure [7] [22].

- Calculate binding free energies using MM/GBSA or MM/PBSA methods.

Quantitative Analysis of Aromatase Inhibitors

Table 2: Experimentally Validated Aromatase Inhibitors from Recent Studies

| Compound ID/Type | IC₅₀ (µM) / Binding Affinity | Research Model | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Azole/Pyrrole-containing Pyridinylmethanamine | 0.04 - 2.31 µM | In vitro aromatase inhibition | More potent than exemestane (IC₅₀ = 2.40 µM); compound 17 showed IC₅₀ = 0.04 µM [20] |

| Marine Natural Product CMPND 27987 | Binding affinity: -10.1 kcal/mol | Molecular docking & dynamics | MM-GBSA binding energy: -27.75 kcal/mol; most stable at active site [17] |

| Indole-based Compound 4 | pIC₅₀: 0.719 nM | SOMFA-based 3D-QSAR | Superior binding affinity compared to letrozole; validated by 100ns MD simulation [23] |

| Novel Azole 7 | 0.34 µM | Structure-based virtual screening | ~98% aromatase inhibition at 12.5 µM; novel scaffold confirmed via DrugBank similarity search [20] |

Research Reagent Solutions for Aromatase Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Aromatase Inhibition Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Specifications/Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Aromatase Structures | Molecular docking and structure-based design | PDB IDs: 3EQM (2.90 Å), 3S7S (crystallized with exemestane) [17] [20] |

| Natural Product Databases | Source of novel inhibitor scaffolds | Comprehensive Marine Natural Products Database (CMNPD) [17] |

| Docking Software | Binding pose prediction and affinity estimation | AutoDock Vina, Gold, SwissDock [17] [24] |

| MD Simulation Packages | Complex stability and dynamics analysis | GROMACS, AMBER with AMBER99SB-ILDN/GAFF force fields [7] [22] |

| Aromatase Inhibition Assay | Experimental validation of inhibitor activity | In vitro aromatase inhibition measuring conversion of androgens to estrogens [20] |

Emerging Protein Targets in Breast Cancer Therapy

Novel Targets and Their Biological Rationale

Beyond established targets like ER and aromatase, several emerging proteins show significant promise for breast cancer therapy. Focal adhesion kinase 1 (FAK1) is a non-receptor tyrosine kinase involved in cancer metastasis and tumor progression through regulation of cell migration and survival [24]. Human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER2) is a tyrosine kinase receptor overexpressed in 15-30% of breast cancers and associated with aggressive disease and poor prognosis [25]. The adenosine A1 receptor has also been identified as a promising target through bioinformatics approaches, with newly designed molecules showing potent antitumor activity [7].

Research Reagent Solutions for Emerging Targets

Table 4: Research Resources for Emerging Breast Cancer Targets

| Target Protein | Key Reagents/Resources | Applications and Findings |

|---|---|---|

| FAK1 Kinase Domain | PDB ID: 6YOJ (1.36 Å); Pharmit for pharmacophore modeling; DUD-E database for actives/decoys [24] | Virtual screening identified ZINC23845603 as stable binder with similar interactions to known ligand P4N [24] |

| HER2 Receptor | PDB ID: 3PP0; Natural ligand 03Q; Autodock Vina for docking; GROMACS for MD simulations [25] | Axitinib and prunetin showed strong binding affinity and stable complexes in 250ns MD simulations [25] |

| Adenosine A1 Receptor | PDB ID: 7LD3; Pharmacophore-based screening; MCF-7 cell assays [7] | Rationally designed Molecule 10 showed IC₅₀ of 0.032 µM against MCF-7 cells, superior to 5-FU control (IC₅₀ = 0.45 µM) [7] |

Integrated Workflow for Multi-Target Drug Discovery

The most effective approach to breast cancer drug discovery involves integrating methodologies across multiple target classes. The following workflow illustrates how computational and experimental techniques can be combined in a comprehensive screening strategy:

This integrated workflow demonstrates how modern drug discovery leverages computational efficiency to prioritize the most promising candidates for experimental validation, significantly reducing time and resource requirements while increasing the probability of success.

Pharmacophore-based virtual screening represents a powerful strategy for identifying novel therapeutic agents targeting key proteins in breast cancer pathogenesis. The approaches outlined in this application note for estrogen receptors, aromatase, and emerging targets like FAK1 and HER2 provide robust frameworks for drug discovery pipelines. The integration of computational methods with experimental validation creates an efficient pathway for transitioning from virtual hits to biologically active leads. As structural biology advances and computational power increases, these methodologies will continue to evolve, enabling more accurate predictions and accelerating the development of next-generation breast cancer therapeutics. Future directions will likely include machine learning-enhanced virtual screening, proteome-wide polypharmacology assessments, and patient-specific structure-based design to overcome resistance mechanisms and improve treatment outcomes.

Implementing PBVS: From Model Construction to Hit Identification

Structure-based pharmacophore modeling is a foundational technique in modern computational drug discovery. It involves the abstraction of key interaction features from a three-dimensional protein-ligand complex to create a model that defines the essential steric and electronic properties required for a molecule to interact with a specific biological target [26]. This approach is particularly valuable when the three-dimensional structure of the target protein is known, as it directly translates observed molecular interactions into a search query for identifying novel drug candidates [27] [28].

In the context of breast cancer research, this method offers a powerful strategy for targeting specific proteins implicated in disease progression. For instance, mutations in the ligand-binding domain of estrogen receptor beta (ESR2) have been closely linked to altered signaling pathways and uncontrolled cell growth in breast cancer [22]. Structure-based pharmacophore modeling enables researchers to target these specific mutant proteins, paving the way for precision inhibition and the development of novel therapeutics that overcome challenges such as endocrine therapy resistance [22].

Theoretical Foundation

Core Concepts and Definitions

A pharmacophore is formally defined by IUPAC as "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or to block) its biological response" [26]. Unlike ligand-based approaches that rely on comparing known active compounds, structure-based pharmacophore models are derived directly from the analysis of protein-ligand complexes [26]. This method captures the critical interactions observed in the binding site, including:

- Hydrogen bond donors (HBD) and acceptors (HBA)

- Hydrophobic interactions (HPho)

- Aromatic interactions (Ar)

- Halogen bond donors (XBD)

- Ionic and metal coordination features [22] [27] [29]

Advantages in Breast Cancer Target Research

Structure-based pharmacophore modeling offers distinct advantages for targeting breast cancer proteins:

- Target-Specific Design: Models can be developed for specific mutant variants, such as ESR2 mutants, addressing therapy resistance mechanisms [22].

- Scaffold Hopping: The ability to identify novel chemotypes with similar interaction patterns but different structural scaffolds [28].

- Efficiency: Significantly reduces time and resources in early drug discovery by focusing experimental efforts on the most promising candidates [24] [28].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Comprehensive Workflow for Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow for structure-based pharmacophore modeling and its application in virtual screening, integrating multiple steps from target preparation to lead identification.

Protocol 1: Structure Preparation and Pharmacophore Generation

Objective: Prepare a protein-ligand complex and generate a structure-based pharmacophore model.

Materials and Software:

- Protein Data Bank (PDB) structure file

- Molecular visualization software (Maestro, Discovery Studio)

- Structure preparation tools (Protein Preparation Wizard in Schrödinger)

- Pharmacophore modeling software (LigandScout, Phase in Schrödinger, Pharmit)

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Retrieve Protein-Ligand Complex

- Obtain the crystal structure from PDB (e.g., PDB ID: 2FSZ, 7XVZ, 7XWR for ESR2 mutants) [22].

- Select structures with high resolution (typically 1.0-2.5 Å) and complete binding site information.

Structure Preparation

- Add hydrogen atoms using standard protonation states at physiological pH.

- Fill in missing side chains or loop regions using modeling tools like MODELLER [24].

- Optimize hydrogen bonding networks and remove structural clashes.

- Generate multiple models if necessary and select the one with the best stereochemical quality (lowest zDOPE score) [24].

Interaction Analysis

- Identify key interactions between the protein and co-crystallized ligand.

- Classify interactions into: hydrogen bonds (donors and acceptors), hydrophobic contacts, aromatic interactions, ionic interactions, and halogen bonds.

- In Maestro, use the "Interactions" panel to visualize non-covalent bonds, including ligand-receptor interactions and aromatic H-bonds [30].

Pharmacophore Feature Identification

- Using LigandScout or similar software, automatically detect pharmacophore features from the protein-ligand complex.

- Manually add missing features that weren't automatically detected. For example, add a donor feature for a hydrogen bond between TRP 311 backbone and the ligand by selecting the specific hydrogen atom involved [30].

- Adjust feature positions and directions to accurately represent interaction geometries.

Pharmacophore Hypothesis Generation

- Create the initial hypothesis using either:

- E-Pharmacophore Method: Automatically generates features based on interaction energy landscapes [30].

- Manual Method: Manually select and position features observed in the complex.

- Define excluded volumes to represent steric constraints of the binding pocket.

- Save the final pharmacophore model for validation and screening.

- Create the initial hypothesis using either:

Protocol 2: Pharmacophore Validation and Virtual Screening

Objective: Validate the pharmacophore model and use it for virtual screening of compound libraries.

Materials and Software:

- Validated pharmacophore model

- Compound libraries (ZINC, NCI, in-house collections)

- Virtual screening tools (ZINCPharmer, Pharmit, Phase)

- Statistical analysis software

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Model Validation

- Collect known active compounds and decoys from databases like DUD-E (Directory of Useful Decoys - Enhanced) [24].

- Screen these validation sets using the pharmacophore model.

- Calculate statistical metrics to evaluate model performance:

Virtual Screening Preparation

- Select appropriate compound libraries for screening (e.g., ZINC database, National Cancer Institute library).

- For complex pharmacophore models with multiple features, use computational scripts to generate feature combinations. For example, with 11 total features, use permutation formulas to create 336 unique combinations for screening [22].

- Pre-filter compounds based on drug-like properties (e.g., Lipinski's Rule of Five).

Virtual Screening Execution

- Screen the compound library against the pharmacophore model using software such as MOE, LigandScout, or Phase.

- Rank hits based on fit scores that indicate how well compounds match the pharmacophore features.

- Select top candidates with high fit scores (typically >80%) for further analysis [22].

Post-Screening Analysis

- Perform molecular docking (e.g., using AutoDock Vina, Glide) to validate binding modes and estimate binding affinities.

- Select compounds with strong binding affinity (e.g., -10.80 kcal/mol for ZINC05925939 to ESR2) [22].

- Evaluate pharmacokinetic properties and potential toxicity using ADMET prediction tools.

Protocol 3: Advanced Validation Using Molecular Dynamics

Objective: Validate the stability of protein-ligand complexes identified through pharmacophore screening.

Materials and Software:

- Molecular dynamics simulation software (GROMACS, AMBER)

- Protein-ligand complexes from docking studies

- High-performance computing resources

Step-by-Step Procedure:

System Preparation

- Prepare protein-ligand complex using appropriate force fields (AMBER99SB-ILDN for proteins, GAFF for ligands) [7].

- Solvate the system in a water box (e.g., TIP3P water model) with a minimum distance of 0.8 nm between the protein and box boundary.

- Add ions to neutralize the system charge.

Energy Minimization and Equilibration

- Perform energy minimization to remove steric clashes.

- Conduct restrained MD simulations (150 ps) at 298.15 K to equilibrate the solvent around the protein.

- Gradually release restraints on the protein backbone and side chains.

Production MD Simulation

Trajectory Analysis

- Calculate root mean square deviation (RMSD) to assess complex stability.

- Analyze root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) to identify flexible regions.

- Compute radius of gyration to monitor compactness.

- Identify key interactions and their persistence throughout the simulation.

Binding Free Energy Calculations

- Perform MM/GBSA or MM/PBSA calculations to estimate binding free energies.

- Use multiple trajectory snapshots for statistically significant results.

- Compare calculated binding energies with experimental data when available.

Application in Breast Cancer Research: Case Study

Targeting Estrogen Receptor Beta (ESR2) Mutants

In a recent study targeting breast cancer, structure-based pharmacophore modeling was applied to mutant forms of estrogen receptor beta (ESR2) [22]. Researchers established a common pharmacophore model among three mutant ESR2 proteins (PDB ID: 2FSZ, 7XVZ, and 7XWR) that identified 11 key features: 2 hydrogen bond donors, 3 hydrogen bond acceptors, 3 hydrophobic interactions, 2 aromatic interactions, and 1 halogen bond donor [22].

Using an in-house Python script, these 11 features were distributed into 336 combinations which were used to screen a library of 41,248 compounds [22]. Virtual screening identified 33 hits, with the top four compounds (ZINC94272748, ZINC79046938, ZINC05925939, and ZINC59928516) showing fit scores exceeding 86% and compliance with Lipinski's Rule of Five [22]. Molecular docking against wild-type ESR2 (PDB ID: 1QKM) revealed binding affinities ranging from -5.73 to -10.80 kcal/mol, outperforming the control compound (-7.2 kcal/mol) [22].

Following 200 ns molecular dynamics simulations and MM-GBSA analysis, ZINC05925939 emerged as the most promising candidate, demonstrating stable binding interactions with ESR2 [22]. This comprehensive approach exemplifies how structure-based pharmacophore modeling can identify novel inhibitors for challenging breast cancer targets.

Signaling Pathways and Therapeutic Targeting

The diagram below illustrates key breast cancer signaling pathways involving ESR2 and other relevant targets, highlighting points for therapeutic intervention.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

| Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Key Functionality | Application in Breast Cancer Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Structure Databases | Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Source of experimental protein-ligand complex structures | Retrieve structures of breast cancer targets (e.g., ESR2 mutants: 2FSZ, 7XVZ, 7XWR) [22] |

| Pharmacophore Modeling Software | LigandScout, Phase (Schrödinger), Pharmit | Generate and validate structure-based pharmacophore models | Create shared feature pharmacophore models for mutant ESR2 proteins [22] [30] |

| Compound Libraries | ZINC Database, NCI Library, PubChem | Source of compounds for virtual screening | Screen for novel inhibitors against breast cancer targets [22] [31] |

| Molecular Docking Tools | AutoDock Vina, Glide (Schrödinger), SwissDock | Predict binding modes and affinities of hit compounds | Validate pharmacophore hits against breast cancer targets [22] [24] |

| Dynamics Simulation Software | GROMACS, AMBER | Assess stability of protein-ligand complexes | Perform 200 ns MD simulations of ESR2-inhibitor complexes [22] [7] |

| Validation Databases | DUD-E (Directory of Useful Decoys - Enhanced) | Provide active compounds and decoys for pharmacophore validation | Validate pharmacophore models for FAK1 and other kinase targets [24] |

| Scripting and Automation | Python, RDKit | Customize screening protocols and analyze results | Generate feature combinations for comprehensive screening [22] [26] |

Table 2: Key Pharmacophore Features and Their Chemical Significance

| Feature Type | Chemical Groups | Role in Protein-Ligand Interactions | Example in Breast Cancer Targets |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Bond Donor (HBD) | -OH, -NH, -NH2 | Forms hydrogen bonds with protein acceptors | Critical for interaction with ESR2 binding site residues [22] |

| Hydrogen Bond Acceptor (HBA) | C=O, -O-, -N | Forms hydrogen bonds with protein donors | Important for binding to kinase domains in FAK1 inhibitors [24] |

| Hydrophobic (HPho) | Alkyl chains, aromatic rings | Participates in van der Waals interactions and desolvation | Stabilizes binding to hydrophobic pockets in KHK-C inhibitors [31] |

| Aromatic (Ar) | Phenyl, heterocyclic rings | Enables π-π and cation-π interactions | Key feature in adenosine A1 receptor ligands for breast cancer [7] |

| Halogen Bond Donor (XBD) | Cl, Br, I | Forms specific halogen bonds with carbonyl oxygens | Present in optimized pharmacophore models for ESR2 mutants [22] |

| Ionic/Charged | -COO-, -NH3+ | Participates in salt bridges and electrostatic interactions | Important for binding to charged residues in catalytic sites |

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Quantitative Analysis of Screening Results

Table 3: Representative Virtual Screening Results for Breast Cancer Targets

| Target Protein | Compound Library Size | Initial Hits | Validation Method | Binding Affinity Range | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESR2 Mutants | 41,248 compounds | 33 hits | Molecular Docking, MD Simulations | -5.73 to -10.80 kcal/mol | [22] |

| FAK1 Kinase | DUD-E Database | 114 actives, 571 decoys | Statistical Validation (EF, GH) | N/A | [24] |

| Ketohexokinase (KHK-C) | 460,000 compounds (NCI) | 10 top candidates | Docking, MD, MM-GBSA | -57.06 to -70.69 kcal/mol (ΔG) | [31] |

| Adenosine A1 Receptor | PubChem Database | 4 compounds (6-9) | Molecular Docking, Synthesis | IC50: 0.032 µM (MCF-7 cells) | [7] |

Success Metrics and Validation Parameters

The success of structure-based pharmacophore modeling should be evaluated using multiple validation parameters:

- Statistical Validation: Enrichment factors (>10-20), goodness of hit scores (>0.5), and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves assess the model's ability to distinguish actives from decoys [24].

- Binding Affinity: Docking scores and calculated binding energies provide quantitative measures of interaction strength. For example, ZINC05925939 showed a binding affinity of -10.80 kcal/mol to ESR2, significantly better than the control compound [22].

- Stability Assessment: Molecular dynamics simulations evaluate complex stability through RMSD (<2-3 Å), RMSF, and interaction persistence throughout the simulation trajectory [22].

- Experimental Validation: Ultimately, compounds should be validated through in vitro assays. For instance, a novel adenosine A1 receptor ligand demonstrated potent antitumor activity against MCF-7 cells with an IC50 of 0.032 µM, significantly outperforming 5-FU (IC50 = 0.45 µM) [7].

Troubleshooting and Optimization

Common Challenges and Solutions

Low Specificity in Virtual Screening

Incomplete Coverage of Binding Site Interactions

- Problem: Automated feature detection misses important interactions.

- Solution: Manually add features based on detailed interaction analysis. In Schrödinger's Phase, use the "Manual Hypothesis" option to add missing donors, acceptors, or hydrophobic features [30].

Handling Protein Flexibility

- Problem: Single crystal structure doesn't represent binding site flexibility.

- Solution: Use multiple protein structures (e.g., apo and holo forms) to create a comprehensive pharmacophore model. Incorporate molecular dynamics snapshots to account for binding site flexibility [27].

Limited Chemical Diversity in Hits

Structure-based pharmacophore modeling represents a powerful approach in the toolkit for breast cancer drug discovery, enabling researchers to leverage structural information to design targeted therapies with improved precision and efficiency. The protocols and applications outlined herein provide a foundation for implementing these methods in ongoing research efforts aimed at developing novel therapeutics for breast cancer treatment.

In the targeted therapeutic landscape of breast cancer research, ligand-based pharmacophore modeling stands as a cornerstone computational technique for rational drug design when three-dimensional structural data of the target protein is unavailable or limited. A pharmacophore is formally defined by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) as "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or to block) its biological response" [32] [33]. In essence, it is an abstract representation of the essential molecular interactions a compound requires to exhibit biological activity, divorced from specific molecular scaffolds.

Ligand-based pharmacophore modeling specifically deduces these critical interaction patterns by analyzing the three-dimensional structural commonalities of a set of known active compounds against a target of interest [34]. This approach is particularly valuable in breast cancer research for targeting proteins like the estrogen receptor alpha (ERα), progesterone receptor (PR), and various kinases where numerous active ligands are known, but obtaining high-quality protein structures for every ligand complex remains challenging [35] [36]. The primary strength of this method lies in its ability to identify novel chemotypes through scaffold hopping, thereby enabling the discovery of innovative therapeutic agents with potentially improved efficacy and safety profiles for breast cancer treatment [32].

Key Concepts and Terminology

Fundamental Pharmacophore Features

A pharmacophore model represents interaction patterns through a set of abstract features that define the type of interaction rather than a specific functional group. The most common features include [32] [33] [34]:

- Hydrogen Bond Acceptor (HBA): An atom or region that can accept a hydrogen bond, typically represented as a vector.

- Hydrogen Bond Donor (HBD): An atom with a hydrogen that can participate in a hydrogen bond, also typically vectorial.

- Hydrophobic (H): A region of the molecule with low polarity, often aliphatic or aromatic carbon chains.

- Aromatic Ring (AR): Pi-electron systems that can engage in cation-π or π-π stacking interactions.

- Positive/Ionic Charge (P): A region with a positive charge that can form electrostatic interactions.

- Negative/Ionic Charge (N): A region with a negative charge for electrostatic binding.

The Conceptual Workflow

The overall process of ligand-based pharmacophore modeling and its application in virtual screening follows a logical sequence, from data collection to experimental validation, as visualized below.

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for Pharmacophore Modeling

Successful implementation of ligand-based pharmacophore modeling relies on a suite of computational tools and data resources. The table below catalogs the essential "research reagents" for the workflow.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

| Tool/Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Software Platforms | PHASE [37], MOE [36], LigandScout [32], Discovery Studio [32] | Provides algorithms for common pharmacophore identification, model generation, and virtual screening. |

| Open-Source Tools | PharmaGist [38], pmapper [38] | Offers free alternatives for pharmacophore generation and screening, though sometimes with limitations (e.g., requiring a template molecule). |

| Compound Databases | ChEMBL [32] [39], ZINC [39] [36], DrugBank [32] | Repositories of bioactive molecules and commercially available compounds used for training sets and virtual screening. |

| Validation Tools | DUD-E [32] [37] | Provides decoy molecules for rigorous model validation and estimation of enrichment factors. |

| Activity Data Repositories | PubChem Bioassay [32], ChEMBL [38] [39] | Sources of bioactivity data (e.g., IC₅₀, Ki) for categorizing compounds as active or inactive. |