Pharmacophore vs. Docking-Based Virtual Screening: A Performance Comparison for Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of pharmacophore-based virtual screening (PBVS) and docking-based virtual screening (DBVS) for researchers and drug development professionals.

Pharmacophore vs. Docking-Based Virtual Screening: A Performance Comparison for Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of pharmacophore-based virtual screening (PBVS) and docking-based virtual screening (DBVS) for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of each method, detailing their specific workflows, software, and application scenarios. The content addresses common challenges and optimization strategies, supported by validation data and benchmark studies that directly compare performance metrics like enrichment factors and hit rates. By synthesizing key takeaways, this review offers practical guidance for selecting and integrating these computational techniques to streamline early-stage drug discovery, reduce costs, and improve the efficiency of identifying viable lead compounds.

Virtual Screening Foundations: Core Principles of Pharmacophore and Docking Methods

Defining Virtual Screening: Its Role and Workflow in Modern Drug Discovery

Virtual screening (VS) has become a cornerstone of modern drug discovery, enabling researchers to computationally evaluate massive libraries of chemical compounds to identify promising candidates that are likely to bind to a therapeutic target. This process significantly accelerates lead discovery by prioritizing molecules for costly and time-consuming experimental testing. Two primary structure-based methodologies dominate the VS landscape: docking-based virtual screening (DBVS) and pharmacophore-based virtual screening (PBVS). DBVS predicts how a small molecule (ligand) fits into a protein's binding site and estimates the binding affinity, while PBVS uses a 3D model of essential interactions a ligand must make with the protein. A persistent and critical question in the field is which method delivers superior performance in identifying active compounds. This guide objectively compares the performance of these two approaches, drawing on recent benchmarking studies and experimental data to inform the selection of virtual screening protocols.

Core Concepts and Workflows

What is Virtual Screening?

Virtual screening is a computational technique used to search large databases of small molecules to identify those structures most likely to bind to a drug target, such as a protein. By simulating the interaction between compounds and the target, VS acts as a powerful filter, enriching the hit rate of subsequent experimental assays and reducing the resources required for lead identification.

Docking-Based Virtual Screening (DBVS)

DBVS relies on the three-dimensional structure of the target protein. It involves computationally "docking" each small molecule from a library into the target's binding site, sampling various orientations and conformations, and then ranking them based on a scoring function that predicts binding affinity. The workflow typically includes protein and ligand preparation, conformational sampling via docking algorithms, and post-docking analysis.

Pharmacophore-Based Virtual Screening (PBVS)

A pharmacophore is an abstract model that defines the spatial and functional features necessary for a molecule to interact with a biological target. These features include hydrogen bond donors, hydrogen bond acceptors, hydrophobic regions, and charged groups. PBVS scans compound libraries to find molecules that match this essential pharmacophore pattern, irrespective of their overall chemical scaffold.

Performance Comparison: PBVS vs. DBVS

The debate over the relative effectiveness of PBVS and DBVS is long-standing. A foundational benchmark study from 2009 provided compelling evidence for the advantages of the pharmacophore-based approach.

Table 1: Benchmark Comparison of PBVS and DBVS Across Eight Protein Targets [1] [2]

| Target Protein | Number of Actives | PBVS Enrichment (Catalyst) | DBVS Enrichment (Best of DOCK, GOLD, Glide) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Angiotensin Converting Enzyme (ACE) | 14 | High | Lower |

| Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) | 22 | High | Lower |

| Androgen Receptor (AR) | 16 | High | Lower |

| D-Alanyl-D-Alanine Carboxypeptidase (DacA) | 3 | High | Lower |

| Dihydrofolate Reductase (DHFR) | 8 | High | Lower |

| Estrogen Receptor α (ERα) | 32 | High | Lower |

| HIV-1 Protease (HIV-pr) | 21 | High | Lower |

| Thymidine Kinase (TK) | 15 | High | Lower |

This comprehensive study concluded that in 14 out of 16 virtual screening scenarios (one target versus two different decoy databases), PBVS demonstrated higher enrichment factors than DBVS. When considering the top 2% and 5% of ranked compounds, the average hit rate for PBVS across all eight targets was "much higher" than those achieved by any of the three docking programs [1] [2].

Advanced and Integrated Workflows

Given the complementary strengths of different VS methods, researchers often combine them to leverage their respective advantages. Integrated workflows can significantly improve screening performance.

Combining PBVS and DBVS

A common strategy is to use PBVS as a pre-filter to rapidly reduce the size of a massive compound library before applying the more computationally intensive DBVS. This hybrid approach was demonstrated in a study searching for marine natural products as SARS-CoV-2 inhibitors, where pharmacophore screening efficiently narrowed down candidates later evaluated by comparative molecular docking [3].

Machine Learning Acceleration

A significant innovation is the application of machine learning (ML) to accelerate VS. One study developed an ensemble ML model that learned from docking results to predict docking scores directly from 2D molecular structures. This approach achieved a 1000-fold acceleration in binding energy predictions compared to classical docking, enabling the ultra-rapid screening of billions of compounds [4].

Fragment-Based Pharmacophore Screening

The FragmentScout workflow represents a modern, data-driven approach to PBVS. It aggregates pharmacophore feature information from multiple experimental fragment poses obtained through high-throughput crystallographic screening (e.g., XChem). These features are combined into a single, powerful "joint pharmacophore query" used to screen large databases. Applied to the SARS-CoV-2 NSP13 helicase, this method successfully identified 13 novel micromolar inhibitors, showcasing its utility in fragment-based lead discovery [5].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear technical reference, below are detailed methodologies for key experiments cited in this guide.

- Target Selection and Preparation: Select eight structurally diverse protein targets (e.g., ACE, AChE, DHFR). For each target, obtain high-resolution crystal structures of protein-ligand complexes from the PDB.

- Pharmacophore Model Generation: Using software like LigandScout, create a consensus pharmacophore model based on multiple co-crystallized ligands for each target.

- Docking Model Preparation: For DBVS, prepare a single high-resolution protein structure for each target, defining the binding site from the co-crystallized ligand.

- Dataset Curation: For each target, compile a set of known active compounds and generate property-matched decoy molecules to create a challenging benchmark database.

- Virtual Screening Execution:

- Perform PBVS using the Catalyst software with the generated pharmacophore models.

- Perform DBVS using three different docking programs (DOCK, GOLD, Glide) against the prepared protein structures.

- Performance Evaluation: Calculate enrichment factors and hit rates for each method by analyzing their ability to rank known active compounds at the top of the list (e.g., within the top 2% and 5%).

- System Preparation:

- Protein: Obtain crystal structures of the target (e.g., PDB IDs 6A2M and 6KP2 for wild-type and quadruple-mutant PfDHFR). Prepare the protein using OpenEye's "Make Receptor" GUI: remove water molecules and redundant chains, add hydrogens, and optimize.

- Ligand Library: Prepare the DEKOIS 2.0 benchmark set, which includes active molecules and structurally similar decoys, using Omega and OpenBabel to generate 3D conformations and correct file formats.

- Molecular Docking: Dock the entire library against the prepared protein structures using multiple docking tools (e.g., AutoDock Vina, FRED, PLANTS) with grid boxes centered on the binding site.

- Machine Learning Rescoring: Extract the top poses generated by each docking program. Rescore these poses using pretrained ML scoring functions such as RF-Score-VS v2 (Random Forest-based) and CNN-Score (Convolutional Neural Network-based).

- Performance Analysis: Evaluate the screening performance using metrics like pROC-AUC and Enrichment Factor at 1% (EF1%). Analyze chemotype enrichment to ensure the retrieval of diverse, high-affinity binders.

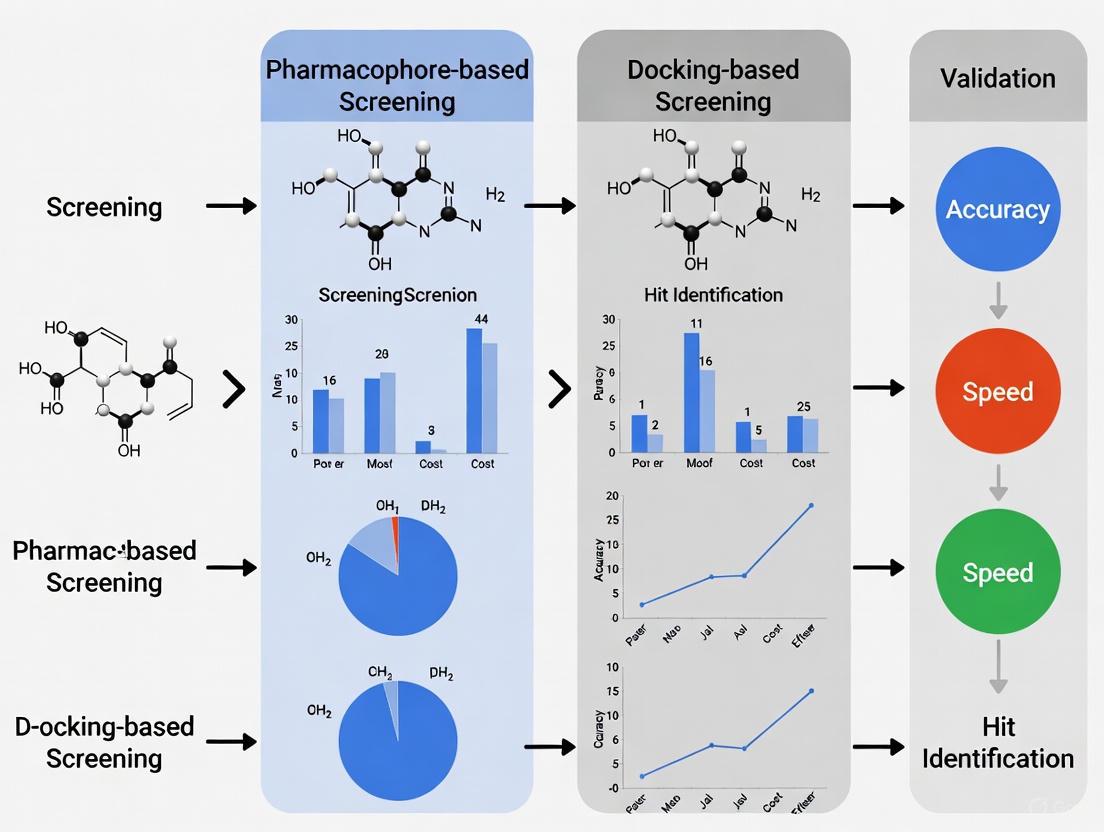

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates a modern, integrated virtual screening workflow that combines pharmacophore screening, molecular docking, and machine learning to maximize the efficiency and success of a drug discovery campaign.

Integrated Virtual Screening Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Software

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Virtual Screening [6] [1] [5]

| Tool Name | Type/Function | Key Application in VS |

|---|---|---|

| AutoDock Vina | Docking Software | Open-source tool for flexible ligand docking and scoring. |

| Glide (Schrödinger) | Docking Software | High-performance docking tool using a hierarchical scoring approach. |

| PLANTS | Docking Software | Docking software that uses ant colony optimization algorithms. |

| LigandScout | Pharmacophore Modeling | Software for creating structure- and ligand-based pharmacophore models and performing PBVS. |

| Catalyst (BIOVIA) | Pharmacophore Modeling | Software for creating pharmacophore hypotheses and performing 3D database searching. |

| DEKOIS 2.0/DUDE-Z | Benchmarking Sets | Public databases containing targets, known actives, and carefully selected decoys for VS benchmarking. |

| RF-Score-VS & CNN-Score | Machine Learning Scoring | Pretrained ML models used to rescore docking poses, significantly improving enrichment. |

| FragmentScout | Fragment-Based Workflow | A specialized workflow for generating pharmacophore queries from XChem fragment screening data. |

| O-LAP | Shape-Based Modeling | Algorithm for generating shape-focused pharmacophore models to improve docking enrichment. |

| Smina | Docking Software | A fork of AutoDock Vina optimized for scoring function development and customizability. |

The choice between pharmacophore-based and docking-based virtual screening is not a simple matter of one being universally superior. The evidence shows that PBVS can achieve higher enrichment in many scenarios, making it an excellent choice for fast, efficient filtering of large libraries or when key ligand-target interactions are well-defined. DBVS provides atomic-level insight into binding modes and is a powerful tool for lead optimization. However, the most impactful modern strategy is an integrated approach that leverages the strengths of both methods. Combining PBVS pre-filtering with DBVS and enhanced by machine learning rescoring represents the current state-of-the-art, offering researchers the best chance of efficiently identifying novel and potent therapeutic candidates in the vast chemical space.

In the landscape of computer-aided drug discovery, virtual screening stands as a pivotal technology for identifying novel lead compounds in a cost-effective manner. Virtual screening methodologies are broadly classified into two categories: structure-based and ligand-based approaches. Pharmacophore-Based Virtual Screening (PBVS) is a powerful ligand-based method that operates on the principle that molecules sharing a common three-dimensional arrangement of essential steric and electronic features will elicit the same biological response [7]. The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) defines a pharmacophore as "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supra-molecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or to block) its biological response" [7] [8]. This abstract representation of interaction capabilities, rather than specific functional groups, enables PBVS to identify structurally diverse compounds that nonetheless possess the necessary characteristics to bind to a target, a significant advantage in scaffold hopping and lead optimization [7].

Performance Comparison: PBVS vs. Docking-Based Virtual Screening (DBVS)

Docking-Based Virtual Screening (DBVS) has gained popularity as it directly simulates the ligand-receptor binding process. However, a benchmark study provides compelling experimental data on their relative performances in retrieving active compounds from databases containing decoys [1].

Quantitative Performance Metrics

The following tables summarize the key findings from a comprehensive comparison study involving eight structurally diverse protein targets: angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE), acetylcholinesterase (AChE), androgen receptor (AR), D-alanyl-D-alanine carboxypeptidase (DacA), dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR), estrogen receptors α (ERα), HIV-1 protease (HIV-pr), and thymidine kinase (TK) [1].

Table 1: Summary of Virtual Screening Performance Across Eight Targets

| Virtual Screening Method | Number of Cases Where Method Outperformed Alternatives | Average Hit Rate at Top 2% of Database | Average Hit Rate at Top 5% of Database |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmacophore-Based (PBVS) | 14 out of 16 cases | Significantly Higher | Significantly Higher |

| Docking-Based (DBVS) | 2 out of 16 cases | Lower | Lower |

| DOCK | Varies by target | Lower | Lower |

| GOLD | Varies by target | Lower | Lower |

| Glide | Varies by target | Lower | Lower |

Table 2: Enrichment Factors for Different Virtual Screening Approaches

| Target | PBVS Enrichment Factor | Best DBVS Enrichment Factor | Performance Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACE | Higher | Lower | PBVS |

| AChE | Higher | Lower | PBVS |

| AR | Higher | Lower | PBVS |

| DacA | Higher | Lower | PBVS |

| DHFR | Higher | Lower | PBVS |

| ERα | Higher | Lower | PBVS |

| HIV-pr | Higher | Lower | PBVS |

| TK | Higher | Lower | PBVS |

The data consistently demonstrates that PBVS achieved higher enrichment factors than DBVS in the vast majority of test cases (14 out of 16) [1]. Furthermore, when considering the top 2% and 5% of the highest-ranked compounds in the database, the average hit rate for PBVS was substantially higher than those obtained by any of the three docking programs (DOCK, GOLD, Glide) [1]. This indicates that PBVS is more effective at prioritizing truly active compounds in the early stages of screening, a critical factor for efficient resource allocation in drug discovery campaigns.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling Protocol

The structure-based approach requires the three-dimensional structure of the target protein, typically obtained from sources like the Protein Data Bank (PDB) [7].

- Protein Preparation: The first critical step involves preparing the protein structure by evaluating and correcting protonation states of residues, adding hydrogen atoms (absent in X-ray structures), and addressing any missing residues or atoms [7].

- Binding Site Detection: The ligand-binding site is identified, either manually using knowledge from experimental data or computationally using tools like GRID or LUDI, which analyze the protein surface for energetically favorable interaction sites [7].

- Feature Generation and Selection: From the protein-ligand complex or the binding site alone, a map of potential interactions (e.g., hydrogen bond acceptors/donors, hydrophobic areas, ionizable groups) is generated. The initial multitude of features is refined to select only those essential for bioactivity, resulting in the final pharmacophore hypothesis [7]. Exclusion volumes are often added to represent the physical boundaries of the binding pocket [8].

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling Protocol

When the 3D structure of the target is unavailable, pharmacophore models can be developed from a set of known active ligands.

- Training Set Selection: A set of structurally diverse molecules with confirmed biological activity and known affinities against the target is assembled. The quality of this dataset directly influences the model's success [8].

- Conformational Analysis: Multiple feasible conformations are generated for each ligand in the training set to account for flexibility [9].

- Common Feature Alignment: The software identifies the maximal common set of pharmacophoric features shared by the active molecules and determines their optimal spatial alignment. Algorithms like HipHop or PharmaGist are commonly used for this purpose [10] [9].

- Model Validation: The generated model is validated using a test set containing both active and inactive molecules or decoys. Metrics like the enrichment factor, yield of actives, and ROC-AUC are calculated to evaluate the model's ability to distinguish active from inactive compounds [8].

Virtual Screening Workflow

Once a validated pharmacophore model is obtained, it serves as a query for screening compound databases.

Diagram 1: The typical workflow for a pharmacophore-based virtual screening campaign, often followed by docking refinement and experimental validation [10] [11] [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Successful implementation of PBVS relies on a suite of computational tools and databases. The table below details key resources used in the featured studies.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for PBVS

| Tool/Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in PBVS | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| LigandScout [1] | Software | Structure-based & ligand-based pharmacophore model generation. | Used to create pharmacophore models from X-ray crystal structures of protein-ligand complexes [1]. |

| Catalyst/HypoGen [1] [10] | Software | Generates quantitative 3D pharmacophore models from a set of active and inactive training molecules. | Utilized to develop a pharmacophore model (Hypo1) for Topoisomerase I inhibitors from CPT derivatives [10]. |

| PharmaGist [9] | Web Server/Software | Ligand-based pharmacophore detection from a set of input ligands, handling flexibility deterministically. | Applied for virtual screening on GPCR alpha1A dataset and the DUD dataset [9]. |

| ZINC Database [10] [12] | Compound Database | A freely available database of commercially available compounds for virtual screening. | Screened to discover potential Topoisomerase I inhibitors; used as a source for phytocompounds [10] [12]. |

| Directory of Useful Decoys, Enhanced (DUD-E) [8] | Decoy Database | Provides optimized decoy molecules for rigorous virtual screening validation. | Used to generate decoys with similar 1D properties but different 2D topology compared to active molecules [8]. |

| Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) [12] | Software Suite | Integrated platform for molecular modeling, simulation, and docking. | Used for molecular docking and virtual screening of a phytochemical library [12]. |

| PyRx [11] | Software | Tool for virtual screening using AutoDock Vina or other docking engines. | Employed for virtual screening of a marine sponge bioactive compound library against multiple Alzheimer's disease targets [11]. |

Pharmacophore-Based Virtual Screening represents a robust and highly effective methodology for lead identification in drug discovery. The experimental evidence demonstrates that PBVS can outperform docking-based methods in enriching active compounds across a wide range of biological targets [1]. Its strength lies in its abstract representation of molecular interactions, which facilitates the identification of novel chemotypes through scaffold hopping. While the choice between structure-based and ligand-based pharmacophore modeling depends on data availability, both approaches have proven successful in prospective virtual screening campaigns, yielding hit rates substantially higher than random high-throughput screening [8]. When integrated into a comprehensive workflow that may include docking refinement and ADMET profiling, PBVS serves as a powerful first-line tool for efficiently navigating vast chemical space and accelerating the discovery of new therapeutic agents.

Molecular docking is a computational cornerstone of structure-based drug design, enabling researchers to predict how small molecule ligands interact with protein targets at the atomic level. Docking-based virtual screening (DBVS) employs computational algorithms to automatically evaluate vast libraries of chemical compounds, predicting their binding conformations (poses) and estimating interaction strengths (affinities) with biomolecular targets. This approach has become indispensable in pharmaceutical research for identifying promising therapeutic candidates from millions of potential compounds, significantly accelerating the early drug discovery pipeline while reducing experimental costs [13] [14].

The fundamental challenge DBVS addresses is balancing computational efficiency with predictive accuracy. Docking methods essentially solve intricate three-dimensional puzzles by identifying the optimal fit between two molecules, typically a protein receptor and a small molecule ligand, through search algorithms and scoring functions. These scoring functions approximate binding affinity by calculating interaction energies, serving the dual purpose of identifying most probable binding poses and ranking compounds by their predicted binding strength [15] [13]. Despite advances, DBVS operates within a competitive landscape alongside other virtual screening approaches, particularly pharmacophore-based methods, with each demonstrating distinct strengths and limitations depending on the specific application context [1] [2].

Performance Comparison: DBVS Versus Alternative Approaches

Benchmark Comparison with Pharmacophore-Based Virtual Screening

A comprehensive benchmark study directly compared pharmacophore-based virtual screening (PBVS) and DBVS across eight structurally diverse protein targets: angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE), acetylcholinesterase (AChE), androgen receptor (AR), D-alanyl-D-alanine carboxypeptidase (DacA), dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR), estrogen receptors α (ERα), HIV-1 protease (HIV-pr), and thymidine kinase (TK). The research employed rigorous experimental design, testing each method against two datasets containing both active compounds and decoys, using Catalyst for PBVS and three docking programs (DOCK, GOLD, and Glide) for DBVS [1] [2].

Table 1: Performance Comparison Between PBVS and DBVS Methods

| Performance Metric | PBVS (Catalyst) | DBVS (Average across DOCK, GOLD, Glide) |

|---|---|---|

| Cases with higher enrichment factors | 14 out of 16 | 2 out of 16 |

| Average hit rate at top 2% of database | Much higher | Lower |

| Average hit rate at top 5% of database | Much higher | Lower |

| Advantages | Superior early enrichment; effectively identifies essential binding features | Directly models physical binding process; provides structural binding information |

| Limitations | Limited detailed energy calculations | Lower enrichment in benchmark study; scoring function challenges |

The results demonstrated that PBVS significantly outperformed DBVS in retrieval of active compounds across most test cases. Of the sixteen sets of virtual screens (one target versus two testing databases), PBVS achieved higher enrichment factors in fourteen cases compared to DBVS methods. When considering the top 2% and 5% of highest-ranked compounds from the entire databases, the average hit rates for PBVS were substantially higher than those for DBVS across all eight targets [1] [2]. This performance advantage suggests that pharmacophore approaches may offer superior early enrichment in virtual screening campaigns, though DBVS provides valuable binding mode information that pharmacophore methods lack.

Comparison Among Docking Scoring Functions

The performance of DBVS is heavily dependent on the scoring functions used to rank potential ligands. A 2025 pairwise comparison study evaluated five scoring functions implemented in Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) software using protein-ligand complexes from the PDBbind database. The research applied InterCriteria Analysis (ICrA), a multi-criterion decision-making approach, to assess performance based on multiple docking outputs including best docking score, lowest root mean square deviation (RMSD), and their combinations [15].

Table 2: Docking Scoring Function Performance Comparison

| Evaluation Metric | Best Performing Function | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Pose prediction accuracy | Lowest RMSD | Most reliable indicator of pose prediction quality |

| Overall comparability | Alpha HB and London dG | Showed highest consistency and performance across multiple criteria |

| Evaluation approach | InterCriteria Analysis (ICrA) | Enabled robust multi-dimensional comparison of scoring functions |

The study identified lowest RMSD as the best-performing docking output metric for assessing pose prediction accuracy. Among the specific scoring functions evaluated, Alpha HB and London dG demonstrated the highest comparability and consistent performance across multiple evaluation criteria. This research highlights the substantial variability between different scoring functions and emphasizes that no single function universally outperforms others across all target proteins and ligand types [15].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard DBVS Workflow and Benchmarking Methods

The experimental protocol for comprehensive DBVS evaluation typically follows a structured pipeline to ensure fair comparison and reproducible results. The benchmark study comparing PBVS and DBVS employed this rigorous methodology [1] [2]:

Target Selection: Eight pharmaceutically relevant proteins with diverse pharmacological functions and structural characteristics were selected.

Structure Preparation: High-resolution crystal structures of each target protein in complex with ligands were obtained from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). For docking studies, a single representative structure was used, while pharmacophore models incorporated multiple complex structures.

Compound Dataset Preparation: Active compounds for each target were curated from the DrugBank database. Two separate decoy sets (Decoy I and Decoy II) containing approximately 1000 non-active molecules each were generated using different methodologies to avoid bias.

Virtual Screening Execution: Each compound database was screened using both PBVS (Catalyst software) and DBVS (DOCK, GOLD, and Glide programs) approaches against the corresponding target.

Performance Evaluation: Screening effectiveness was quantified using enrichment factors (EF) and hit rates at specific percentages (2% and 5%) of the top-ranked database compounds.

Advanced DBVS Integration Protocols

Recent methodological advances have integrated multiple approaches to overcome limitations of traditional DBVS:

DockBind Framework: IBM Research developed DockBind, which leverages docking poses with advanced machine learning. This approach uses MACE, an SO(n) equivariant graph neural network, to capture detailed atomic environments in binding regions defined by spatial proximity of ligand and protein atoms. The method incorporates data augmentation using top-10 ranked docking poses from DiffDock (a diffusion-based blind docking algorithm) rather than relying solely on the top-ranked pose. Ensembling predictions across multiple poses improves robustness against misranked conformations. The framework additionally integrates physical and chemical descriptors including neural potential energy estimates, molecular fingerprints, and DFT-based energy calculations to refine binding affinity predictions [16].

Pose Ensemble Graph Neural Networks: The DockBox2 (DBX2) approach introduces graph neural networks that encode ensembles of computational poses rather than single conformations. This method represents a significant advancement as it accounts for the dynamic nature of ligand-protein interactions. DBX2 was trained on the PDBbind dataset to jointly predict binding pose likelihood (node-level task) and binding affinity (graph-level task), demonstrating that learning from multiple conformations improves both docking and virtual screening performance compared to physics-based and single-pose ML methods [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

Table 3: Key Computational Tools for Docking-Based Virtual Screening

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| DOCK | Docking Program | Search algorithm & physics-based scoring | General purpose DBVS |

| GOLD | Docking Program | Genetic algorithm & empirical scoring | DBVS with protein flexibility |

| Glide | Docking Program | Hierarchical docking & precision scoring | High-accuracy DBVS |

| AutoDock Vina | Docking Program | Monte Carlo optimization & empirical scoring | Rapid DBVS with balanced accuracy |

| DiffDock | Deep Learning Docking | Diffusion-based generative pose prediction | Blind docking scenarios |

| FeatureDock | Deep Learning Docking | Transformer-based pose & affinity prediction | Feature-based local environment learning |

| PDBbind | Database | Curated protein-ligand complexes with binding data | Method training & benchmarking |

| Directory of Useful Decoys (DUD) | Database | Active compounds & decoys for specific targets | Virtual screening performance validation |

| MOE (Molecular Operating Environment) | Software Suite | Multiple scoring functions & molecular modeling | Comprehensive drug discovery platform |

| RosettaVS | Software Suite | Physics-based docking with flexibility modeling | High-precision virtual screening |

Recent Advances and Future Directions

Deep Learning Transformations in Molecular Docking

Traditional molecular docking approaches primarily follow search-and-score algorithms that are computationally demanding and often simplify protein flexibility to maintain feasibility. Recent years have witnessed a surge in deep learning (DL) applications that are transforming the docking landscape. Methods such as EquiBind, TankBind, and particularly DiffDock have demonstrated accuracy rivaling or surpassing traditional approaches while significantly reducing computational costs [18].

DiffDock implements diffusion models to molecular docking, progressively adding noise to ligand degrees of freedom (translation, rotation, and torsion angles) then using an SE(3)-equivariant graph neural network to learn a denoising score function that iteratively refines ligand poses. This approach has achieved state-of-the-art accuracy on PDBBind test sets while operating at a fraction of the computational cost of traditional methods [18]. However, DL docking models face challenges with generalizing beyond training data and sometimes mispredict key molecular properties like stereochemistry and bond lengths, leading to physically unrealistic predictions [18].

Addressing Protein Flexibility and Scoring Limitations

A significant limitation of many docking approaches is the treatment of proteins as rigid structures, neglecting inherent flexibility and induced fit effects upon ligand binding. Recent advancements aim to incorporate protein flexibility more comprehensively. Methods like FlexPose enable end-to-end flexible modeling of protein-ligand complexes regardless of input protein conformation (apo or holo) [18]. Similarly, RosettaVS incorporates receptor flexibility through modeling of sidechains and limited backbone movement, which proves critical for targets requiring induced conformational changes [14].

For scoring function limitations, new approaches combine physical models with machine learning. FeatureDock utilizes transformer-based architecture to leverage physicochemical features from protein local environments, achieving both pose prediction and improved scoring power for virtual screening. This method discretizes binding pockets into grid points using 3D-invariant FEATURE representations, then applies transformer encoders to predict probability density envelopes for ligand binding [19]. The DockBind framework similarly integrates multiple feature types including MACE-based binding predictions, neural potential energy estimates, and molecular fingerprints to enhance affinity estimation accuracy [16].

Emerging Trends and Integration Strategies

The future of DBVS points toward hybrid approaches that leverage the strengths of multiple methodologies. The benchmark results demonstrating PBVS superiority in early enrichment suggest strategic integration where pharmacophore methods could pre-filter compound libraries before applying more computationally intensive DBVS [1] [2]. Similarly, using deep learning for initial binding site identification followed by traditional docking for pose refinement represents another promising hybrid strategy [18].

Ultra-large library screening capabilities are also advancing rapidly. The development of platforms like OpenVS incorporating active learning techniques enables efficient screening of billion-compound libraries by training target-specific neural networks during docking computations to triage promising compounds for expensive calculations [14]. These advances, combined with improved handling of protein flexibility and more sophisticated scoring functions, are progressively expanding the capabilities and applications of docking-based virtual screening in modern drug discovery.

Virtual screening (VS) has become a cornerstone of modern drug discovery, enabling researchers to computationally evaluate vast libraries of compounds to identify promising candidates for further experimental testing. Among the various VS strategies, two primary methodologies have emerged as particularly influential: pharmacophore-based virtual screening (PBVS) and docking-based virtual screening (DBVS). These approaches differ fundamentally in their underlying principles, information requirements, and methodological execution. PBVS relies on the identification and matching of essential chemical features responsible for biological activity, while DBVS focuses on predicting the atomic-level binding geometry and affinity between a small molecule and a protein target. This guide provides a detailed, objective comparison of these two methodologies, examining their respective information requirements, underlying mechanisms, and performance based on experimental benchmarking studies, to inform researchers and drug development professionals in selecting the appropriate tool for their projects.

Core Methodological Principles

Pharmacophore-Based Virtual Screening (PBVS)

A pharmacophore is an abstract model that defines the essential chemical features a molecule must possess to interact with a specific biological target and elicit a pharmacological response. It captures the steric and electronic features necessary for optimal molecular interactions, without being tied to a specific chemical scaffold. Key features include hydrogen bond donors and acceptors, positive and negative ionizable areas, hydrophobic regions, and aromatic rings.

The PBVS process typically involves:

- Pharmacophore Model Generation: Creating a hypothesis of the essential interaction features.

- Database Searching: Screening virtual compound libraries to identify molecules that match the pharmacophore model in three-dimensional space.

- Hit Identification: Selecting compounds that fulfill the spatial and chemical constraints of the model for further evaluation.

Docking-Based Virtual Screening (DBVS)

Molecular docking simulates the process of how a ligand binds to a protein's active site. It is a more physically grounded approach that aims to predict the binding pose (geometry) of the ligand and often estimate the binding affinity using a scoring function.

The DBVS process typically involves:

- Protein and Ligand Preparation: Defining the protein's binding site and generating feasible 3D conformations for the ligands.

- Conformational Search: Exploring possible orientations and conformations of the ligand within the binding site.

- Scoring and Ranking: Evaluating and ranking each predicted pose using a scoring function to estimate binding strength.

Comparative Analysis: Information Requirements and Methodologies

The fundamental differences between PBVS and DBVS stem from their distinct objectives, which directly dictate their information requirements and methodological workflows. The table below summarizes these key distinctions.

Table 1: Key Differences in Information Requirements and Methodologies between PBVS and DBVS

| Aspect | Pharmacophore-Based Virtual Screening (PBVS) | Docking-Based Virtual Screening (DBVS) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Objective | Identify compounds that match a set of essential chemical features for biological activity. [1] [20] | Predict the atomic-level binding geometry and affinity of a ligand in a protein's binding site. [21] |

| Essential Information Requirement | • A set of key functional features and their spatial arrangement.• Can be derived from known active ligands or a protein-ligand complex structure. [22] [23] | A high-resolution 3D structure of the target protein (e.g., from X-ray crystallography or Cryo-EM). [6] [24] |

| Underlying Methodology | Creates an abstract, chemical feature-based query to search 3D compound databases. [22] | Performs a conformational search and scores poses based on force fields, empirical data, or machine learning. [21] |

| Handling of Protein Flexibility | Implicitly handled by the abstract nature of chemical features. | Often challenging; typically requires explicit sampling or ensemble docking, which is computationally expensive. |

| Computational Speed | Generally faster, suitable for rapid screening of ultra-large libraries. [25] | Slower, computational cost scales with the complexity of the search algorithm and scoring function. [25] |

| Key Output | A list of compounds that match the pharmacophore hypothesis. | Ranked list of compounds with predicted binding poses and scores. |

Experimental Benchmarking and Performance Data

A Landmark Performance Comparison

A seminal benchmark study directly compared PBVS and DBVS across eight structurally diverse protein targets: ACE, AChE, AR, DacA, DHFR, ERα, HIV-pr, and TK. The study utilized the Catalyst program for PBVS and three popular docking programs (DOCK, GOLD, Glide) for DBVS. The performance was evaluated using enrichment factors (EF)—a measure of a method's ability to prioritize known active compounds over inactive decoys in a database. [1] [20]

The results were revealing. In fourteen out of sixteen virtual screening scenarios (one target screened against two different decoy databases), PBVS demonstrated higher enrichment factors than DBVS. [1] [20] The average hit rates, which indicate the number of true actives found within a small percentage of the top-ranked compounds, further underscored this trend.

Table 2: Average Hit Rate Comparison from Benchmark Study on Eight Targets [1] [20]

| Method | Average Hit Rate at 2% of Database | Average Hit Rate at 5% of Database |

|---|---|---|

| Pharmacophore-Based VS (Catalyst) | Much Higher | Much Higher |

| Docking-Based VS (DOCK, GOLD, Glide) | Lower | Lower |

The study concluded that for the tested targets, PBVS was more powerful than DBVS in retrieving active compounds from the databases. [1] [20] This superior enrichment performance has been corroborated in other target-specific studies, such as one identifying CXCR4 antagonists, where a pharmacophore model achieved the highest virtual screening performance compared to docking and shape-matching approaches. [23]

Advancements and Hybrid Approaches

While traditional docking methods have limitations, the field is rapidly evolving. The integration of machine learning (ML) has shown significant promise in improving DBVS performance. For instance, rescoring docking outputs with ML-based scoring functions like CNN-Score has been shown to dramatically improve enrichment, elevating some docking tools from worse-than-random to better-than-random performance in screening for antimalarial compounds. [6]

Furthermore, combining both methodologies in a sequential or hybrid workflow is a common and effective strategy in modern drug discovery campaigns. A typical pipeline involves:

- Using a fast PBVS step to rapidly filter large compound libraries and remove obvious mismatches.

- Subjecting the resulting, smaller subset of compounds to more computationally intensive DBVS for a detailed binding assessment.

- This approach was demonstrated in a study seeking VEGFR-2/c-Met dual inhibitors, where pharmacophore screening was used first to narrow down 1.28 million compounds, after which molecular docking was applied to refine the selection. [22]

Diagram: A typical hybrid virtual screening workflow that leverages the speed of PBVS for initial filtering and the detailed assessment of DBVS for refined hit selection.

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

The experimental protocols cited in this guide rely on a suite of specialized software tools and data resources. The following table details key "research reagent solutions" essential for conducting PBVS and DBVS experiments.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Virtual Screening

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in VS | Example Use in Cited Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| LigandScout [1] | Software | Constructs structure-based pharmacophore models from protein-ligand complexes. | Used to generate pharmacophore models for the 8-target benchmark study. [1] |

| Catalyst/Hypogen [1] | Software Algorithm | Performs pharmacophore-based database searching and validation. | Used for all PBVS runs in the 8-target benchmark study. [1] |

| Glide, GOLD, DOCK [1] [21] | Docking Software Suite | Programs for performing molecular docking and scoring. | Represented the DBVS methods in the 8-target benchmark; Glide is noted for high physical validity. [1] [21] |

| AutoDock Vina [6] [21] | Docking Software | A widely used open-source program for molecular docking. | Evaluated for screening performance against PfDHFR; performance improved with ML rescoring. [6] |

| DEKOIS [6] | Benchmark Database | Provides sets of known active molecules and carefully selected decoys for VS benchmarking. | Used to evaluate docking tools and ML rescoring for PfDHFR variants. [6] |

| CryoXKit [24] | Software Tool | Incorporates experimental electron density maps from Cryo-EM or X-ray crystallography to guide docking. | Improved docking pose prediction and virtual screening performance by using experimental density as a bias. [24] |

| Machine Learning Scoring Functions (e.g., CNN-Score, RF-Score-VS) [6] | Scoring Algorithm | ML-based functions to re-score docking poses, improving affinity prediction and enrichment. | Significantly improved the enrichment power of traditional docking programs in benchmark tests. [6] |

The comparative analysis of pharmacophore-based and docking-based virtual screening reveals that the choice of method is not a matter of one being universally superior, but rather of selecting the right tool for the specific research context. PBVS, with its lower information requirement and computational cost, excels in the rapid enrichment of large compound libraries and is highly effective when protein structures are unavailable. DBVS provides an atomistically detailed view of the binding interaction, which is invaluable for lead optimization, but is more computationally demanding and historically showed lower enrichment in some benchmark studies. [1] [20]

The future of virtual screening lies in the synergistic integration of these methods, often in sequential workflows, and the adoption of new technologies. The rise of deep learning is beginning to address traditional docking limitations, though challenges with physical plausibility and generalization remain. [21] Furthermore, methods that directly integrate experimental data, such as Cryo-EM density, to guide docking exemplify the trend toward more hybrid and data-driven approaches. [24] For researchers, a pragmatic strategy that leverages the speed and feature-based logic of PBVS for initial filtering, followed by the detailed structural insights from DBVS (potentially enhanced by ML), represents a powerful paradigm for accelerating drug discovery.

The Synergistic Role of VS in the Broader Drug Discovery Pipeline

Virtual screening (VS) has become an indispensable tool in modern drug discovery, enabling the efficient identification of potential drug candidates from vast chemical libraries. The two predominant computational strategies—pharmacophore-based screening and molecular docking—each offer distinct advantages and face unique challenges. This guide provides an objective comparison of their performance, supported by recent experimental data and methodologies, to inform researchers and drug development professionals.

Performance Comparison: Pharmacophore-Based Screening vs. Molecular Docking

The table below summarizes key performance characteristics of pharmacophore-based and docking-based virtual screening methods, based on recent benchmarking studies.

| Performance Metric | Pharmacophore-Based Screening | Docking-Based Screening |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Speed | Extremely fast (sub-linear time, orders of magnitude faster than docking) [26]; ML-predicted scores can be ~1000x faster than classical docking [4] | Computationally intensive and time-consuming, a key bottleneck for ultra-large libraries [27] [26] |

| Typical Library Size | Suitable for screening millions of compounds quickly [26] | Screening billions of compounds requires substantial computing resources [4] [26] |

| Key Strength | High resource efficiency; effective for rapidly filtering large libraries [26] | Direct, physics-based simulation of ligand pose and affinity within a protein binding site [28] |

| Common Limitations | Quality of results heavily dependent on the quality of the pharmacophore query [26] | Scoring functions remain imperfect, with limitations in accuracy and high false positive rates [27] |

| Hit-Rate & Affinity | Successfully identified novel micromolar inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 NSP13 [5] | Hit-rates can be modeled as a function of library size and scoring noise; improved scoring can substantially enhance hit-rates and affinities [29] |

| Generalizability | Models can be generated from ligand data or protein structure; automated tools like PharmacoForge show promise for generalizability [26] | Performance can degrade with novel protein binding pockets; deep learning methods show significant generalization challenges [21] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Data

Fragment-Based Pharmacophore Screening for SARS-CoV-2 Inhibitors

A novel workflow named FragmentScout was developed to efficiently identify potent inhibitors from weak fragment hits [5].

- Methodology: The protocol starts with high-throughput crystallographic fragment screening data (e.g., from XChem). Multiple fragment poses binding to a specific site on the target protein (SARS-CoV-2 NSP13 helicase) are processed using Inte:ligand's LigandScout software. The software automatically detects pharmacophore features (e.g., hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic areas) from each fragment pose and aggregates them into a single, comprehensive joint pharmacophore query. This query is then used to screen large 3D conformational databases [5].

- Performance Outcome: This method led to the discovery of 13 novel micromolar potent inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 NSP13, which were validated in cellular antiviral assays. It effectively bridges the gap between millimolar fragment hits and micromolar lead compounds [5].

Benchmarking Docking and Machine Learning Rescoring for Malaria

A comprehensive study evaluated the performance of docking tools and machine learning (ML) rescoring against wild-type (WT) and drug-resistant (Q) Plasmodium falciparum dihydrofolate reductase (PfDHFR) [6].

- Methodology: Three docking tools—AutoDock Vina, PLANTS, and FRED—were used to screen the DEKOIS 2.0 benchmark set against both PfDHFR variants. The resulting ligand poses were then rescored by two pretrained ML scoring functions: RF-Score-VS v2 and CNN-Score. Performance was measured by enrichment factor at the top 1% of ranked molecules (EF 1%) [6].

- Performance Outcome:

- For WT PfDHFR, PLANTS combined with CNN-Score yielded the best enrichment (EF 1% = 28).

- For the resistant Q variant, FRED combined with CNN-Score performed best (EF 1% = 31).

- Rescoring with ML significantly improved the performance of some docking tools, with CNN-Score consistently enhancing the retrieval of diverse, high-affinity binders for both variants [6].

Machine Learning-Accelerated Pharmacophore Screening for MAO Inhibitors

A universal methodology was introduced that uses ML to predict docking scores, drastically speeding up the virtual screening process [4].

- Methodology: An ensemble ML model was trained on docking results from Smina software to predict docking scores based solely on 2D molecular structures and fingerprints. This model was then used to perform a pharmacophore-constrained screening of the ZINC database, prioritizing compounds that matched the pharmacophore model and had favorable predicted scores [4].

- Performance Outcome: The ML-based score prediction was ~1000 times faster than classical molecular docking. From the top-ranked compounds, 24 were synthesized and tested, leading to the discovery of new weak inhibitors of MAO-A [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

The table below lists key software and resources used in the featured studies, which are essential for building a virtual screening pipeline.

| Tool Name | Type/Function | Key Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| LigandScout | Pharmacophore Modeling & Screening | Generating joint pharmacophore queries from fragment data and performing pharmacophore-based virtual screening [5]. |

| Glide | Molecular Docking | High-performance, physics-based docking; often used as a benchmark for accuracy and pose validity [5] [21]. |

| AutoDock Vina | Molecular Docking | Widely used, generic docking tool; commonly evaluated in benchmarking studies [6] [21]. |

| Smina | Molecular Docking | A variant of Vina often used for its customizability and as a basis for training ML models [4]. |

| CNN-Score / RF-Score-VS v2 | Machine Learning Scoring Functions | Rescoring docking outputs to significantly improve enrichment and identify active compounds [6]. |

| PharmacoForge | AI-Based Pharmacophore Generation | Generating 3D pharmacophore hypotheses directly from a protein pocket structure using a diffusion model [26]. |

| DEKOIS | Benchmarking Sets | Public sets of active and decoy molecules for rigorous evaluation of virtual screening methods [6]. |

Integrated Workflows and Emerging Trends

The most successful virtual screening campaigns often leverage the strengths of both pharmacophore and docking methods in a sequential or integrated workflow [28].

- Sequential Filtering: A common strategy uses a fast pharmacophore screen as an initial filter to reduce the size of a large database, followed by more computationally intensive molecular docking on the top hits [28] [30]. This combines the speed of pharmacophore screening with the detailed pose analysis of docking.

- Rise of Deep Learning and AI: AI is transforming both methodologies. Deep learning models are now being applied to docking for pose prediction and scoring, though they still face challenges with physical plausibility and generalization [21]. For pharmacophores, generative AI models like PharmacoForge can automatically design pharmacophore queries from protein pockets, streamlining the process [26].

- Addressing Resistance and Generalization: As seen in the malaria study, combining docking with ML rescoring is a powerful strategy against drug-resistant targets. The ability of these pipelines to identify leads for resistant variants is crucial for modern drug discovery [6].

The following diagram illustrates a modern, synergistic virtual screening workflow that integrates these various tools and strategies.

Synergistic VS Workflow

In conclusion, pharmacophore-based and docking-based virtual screening are not mutually exclusive but are highly synergistic components of the drug discovery pipeline. Pharmacophore models excel as a rapid, efficient initial filter to manage the scale of modern chemical libraries. Molecular docking provides a more detailed, physics-based assessment of binding interactions and poses. The integration of both methods, now supercharged by machine learning and AI, creates a robust and effective strategy for identifying novel, potent, and even resistance-beating drug candidates, solidifying the critical role of virtual screening in accelerating therapeutic development.

Methodologies in Action: Implementing PBVS and DBVS Workflows

Structure-Based vs. Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling Approaches

In the field of computer-aided drug discovery (CADD), pharmacophore modeling has emerged as a powerful and versatile technique for identifying potential therapeutic compounds. A pharmacophore is formally defined as "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or to block) its biological response" [7]. In practical terms, it represents the essential molecular functionalities and their spatial arrangement required for biological activity against a specific target. Pharmacophore approaches reduce the time and costs needed to develop novel drugs, making them particularly valuable for addressing health emergencies and the growing field of personalized medicine [7].

The fundamental features comprising a pharmacophore model include hydrogen bond acceptors (HBA), hydrogen bond donors (HBD), hydrophobic areas (H), positively or negatively ionizable groups (PI/NI), aromatic rings (AR), and metal coordinating areas [7]. These abstract features are represented as geometric entities such as spheres, planes, and vectors in three-dimensional space, allowing them to capture the essential interaction capabilities of molecules beyond their specific atomic compositions [7]. This abstraction enables pharmacophore models to identify structurally diverse compounds that share key interaction features, facilitating scaffold hopping and the discovery of novel chemotypes.

Pharmacophore modeling primarily branches into two distinct methodologies: structure-based and ligand-based approaches. The selection between these methods depends on available data, with structure-based approaches requiring three-dimensional structural information of the target protein, while ligand-based methods rely on the physicochemical properties and structural features of known active compounds [7]. Both approaches serve as valuable tools in virtual screening, where they guide the efficient evaluation of large compound libraries to identify potential candidates for further development [1].

Methodological Foundations: Key Approaches and Techniques

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

Structure-based pharmacophore modeling derives its hypotheses directly from the three-dimensional structure of a macromolecular target. This approach requires either an experimental structure (from X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, or cryo-EM) or a high-quality homology model of the target protein [7]. The workflow for structure-based pharmacophore modeling follows a systematic process, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Protein preparation represents the critical first step, involving the assessment and optimization of the protein structure. This includes evaluating residue protonation states, positioning hydrogen atoms (which are typically absent in X-ray structures), handling non-protein groups, addressing missing residues or atoms, and verifying stereochemical and energetic parameters [7]. The quality of the input structure directly influences the quality of the resulting pharmacophore model, making this preparation phase essential.

Ligand-binding site detection follows, where the region of the protein where ligands bind is identified. This can be achieved through manual analysis of residues with known functional roles from experimental data, or more efficiently using bioinformatics tools that scan the protein surface for potential binding sites based on evolutionary, geometric, energetic, or statistical properties [7]. Programs such as GRID and LUDI are commonly employed for this purpose, with GRID using molecular interaction fields and LUDI applying geometric rules derived from known non-bonded contacts in experimental structures [7].

Pharmacophore feature generation and selection constitutes the final phase. When a protein-ligand complex structure is available, the pharmacophore features are derived from the interactions observed between the ligand and protein, with the ligand's bioactive conformation informing the spatial arrangement of features [7]. The presence of the receptor also allows for the incorporation of exclusion volumes to represent spatial restrictions of the binding site [7]. In the absence of a bound ligand, the pharmacophore model must be generated based solely on the target structure, which typically results in less accurate models that require manual refinement [31].

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

Ligand-based pharmacophore modeling approaches generate hypotheses based on the structural and chemical features shared by a set of known active compounds, without requiring direct knowledge of the target protein's structure. This method operates on the principle that compounds sharing common chemical functionalities in similar spatial arrangements likely exhibit similar biological activities against the same target [31]. The methodology proceeds through several well-defined stages, as depicted in Figure 2.

The process begins with the selection of experimentally validated active compounds that constitute the training set. The quality, diversity, and potency range of these compounds significantly influence the resulting model's quality and discriminatory power [10]. An ideal training set includes structurally diverse compounds covering a range of biological activities to ensure the identification of essential features correlated with potency.

Generation of 3D conformations and structural alignment follows, where multiple low-energy conformations are generated for each active compound. These conformations are then aligned to identify common spatial arrangements of chemical features [31]. The conformational flexibility of molecules presents a challenge, as the bioactive conformation must be adequately sampled or approximated.

Identification of structural characteristics and functional groups involved in molecular recognition forms the core of model development. The model identifies conserved features across the aligned active compounds, including hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions, ionizable groups, and aromatic rings [31]. Two primary scoring function methods exist for evaluating how well compounds fit the pharmacophore model: RMSD-based methods, which measure distances between compound functional groups and pharmacophore feature centers, and overlay-based methods, which use atomic and functional group radii to estimate functional similarity [31].

Model validation using test compounds represents the final crucial step. The pharmacophore hypothesis is tested against a set of known active (true positives) and inactive (false positives) compounds to evaluate its ability to discriminate between them [31]. Striking an appropriate balance between model restrictiveness and flexibility is essential, as overly strict models may limit structural diversity, while excessively permissive models may retrieve too many false positives [31].

Experimental Comparison: Performance Evaluation and Benchmark Studies

Experimental Design for Method Evaluation

Rigorous benchmarking studies have been conducted to evaluate the relative performance of structure-based and ligand-based pharmacophore modeling, particularly in comparison with other virtual screening methods. A comprehensive study published in Acta Pharmacologica Sinica employed a systematic research pipeline to compare pharmacophore-based virtual screening (PBVS) with docking-based virtual screening (DBVS) across eight structurally diverse protein targets [1] [2].

The experimental design incorporated eight pharmaceutically relevant targets: angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE), acetylcholinesterase (AChE), androgen receptor (AR), D-alanyl-D-alanine carboxypeptidase (DacA), dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR), estrogen receptor α (ERα), HIV-1 protease (HIV-pr), and thymidine kinase (TK) [1]. These targets represent diverse pharmacological functions and disease areas, ensuring broad applicability of the findings.

For each target, researchers constructed active compound datasets from experimentally validated actives sourced from the DrugBank database [2]. To ensure rigorous assessment, they employed two separate decoy datasets (Decoy I and Decoy II) comprising approximately 1000 non-active molecules each, generated using different methodologies to avoid bias [2]. This design created sixteen distinct test scenarios (eight targets × two decoy sets) for robust method evaluation.

The study implemented multiple screening methodologies to minimize tool-specific bias. For PBVS, they used Catalyst software with pharmacophore models generated from multiple X-ray structures of protein-ligand complexes using LigandScout [1]. For DBVS, they employed three different docking programs: DOCK, GOLD, and Glide, applying each to high-resolution crystal structures of ligand-protein complexes [2]. This multi-program approach helped account for variations in algorithm performance.

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The benchmark study yielded compelling quantitative results comparing the effectiveness of pharmacophore-based and docking-based virtual screening approaches. Performance was primarily evaluated using enrichment factors (measuring the relative abundance of active compounds in the top-ranked fraction compared to random selection) and hit rates (the percentage of identified compounds that are truly active) [1].

Table 1: Virtual Screening Performance Across Eight Protein Targets

| Screening Method | Enrichment Factor (Average) | Hit Rate at Top 2% | Hit Rate at Top 5% |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmacophore-based (PBVS) | Higher in 14/16 cases | Much higher | Much higher |

| Docking-based (DBVS) | Lower in most cases | Lower | Lower |

| DOCK | Variable | - | - |

| GOLD | Variable | - | - |

| Glide | Variable | - | - |

The results demonstrated that PBVS significantly outperformed DBVS across most test conditions. Of the sixteen virtual screening scenarios (eight targets against two decoy sets), PBVS achieved higher enrichment factors in fourteen cases [1]. When examining the top 2% and 5% of highest-ranked compounds from the entire databases, the average hit rates for PBVS were substantially higher than those for all docking methods [1].

This performance advantage was consistent across most targets, suggesting that PBVS offers generally superior retrieval of active compounds from complex compound libraries compared to DBVS approaches [2]. The robustness of pharmacophore-based methods stems from their focus on essential interaction features rather than complete atomic-level complementarity, which appears to provide better discrimination between actives and inactives in virtual screening applications.

Case Studies in Practical Applications

Real-world applications further demonstrate the strengths and appropriate use cases for both structure-based and ligand-based pharmacophore approaches. In the search for selective carbonic anhydrase IX (hCA IX) inhibitors for cancer therapy, researchers successfully employed ligand-based pharmacophore modeling to identify novel chemotypes from natural sources [32]. Using seven known active compounds with IC₅₀ values below 50 nM, they developed a pharmacophore model featuring two aromatic hydrophobic centers and two hydrogen bond donor/acceptor features [32]. This model successfully identified 43 potential inhibitors through virtual screening, with subsequent molecular docking and dynamics simulations confirming their potential for selective hCA IX inhibition.

Another study applied combined structure-based and ligand-based strategies to discover mosquito repellents from essential oil constituents. Researchers used the structure of DEET complexed with an odorant-binding protein for structure-based modeling, while also employing structural similarity searching as a ligand-based approach [31]. This integrated strategy identified seven natural volatile compounds with predicted repellent activity, including p-cymen-8-yl, thymol acetate, and carvacryl acetate [31].

For Topoisomerase I inhibitor discovery, researchers developed a ligand-based pharmacophore model using 29 camptothecin derivatives through the HypoGen algorithm [10]. After rigorous validation, this model screened over one million drug-like molecules from the ZINC database, ultimately identifying three promising candidates with strong binding interactions, favorable toxicity profiles, and stable molecular dynamics simulations [10].

Integrated Workflows and Advanced Methodologies

Synergistic Integration of Approaches

Rather than positioning structure-based and ligand-based approaches as mutually exclusive alternatives, modern drug discovery increasingly employs integrated workflows that leverage the complementary strengths of both methodologies. Structure-based pharmacophores can serve as effective pre-filters or post-filters for docking-based virtual screening, helping to eliminate compounds that lack essential interaction features or possess undesirable characteristics [1]. This hybrid approach has been shown to increase enrichment rates compared to docking alone [2].

The emergence of machine learning and artificial intelligence has further advanced integrated pharmacophore strategies. The CMD-GEN framework exemplifies this trend, bridging ligand-protein complexes with drug-like molecules through coarse-grained pharmacophore points sampled from diffusion models [33]. This approach employs a hierarchical architecture that decomposes three-dimensional molecule generation into pharmacophore point sampling, chemical structure generation, and conformation alignment, effectively addressing instability issues in molecular generation [33].

Another innovative methodology, O-LAP, introduces shape-focused pharmacophore modeling through graph clustering algorithms that generate cavity-filling models by clustering overlapping atomic content from docked active ligands [34]. This approach significantly improves docking enrichment by comparing shape similarity between flexibly sampled poses and target binding cavities, demonstrating the continued evolution of pharmacophore techniques [34].

Experimental Protocols and Research Reagents

Successful implementation of pharmacophore modeling requires specific computational tools and protocols. The experimental benchmarks discussed employed several established software packages and data resources, detailed in Table 2.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Pharmacophore Modeling

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Sources | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Structure-Based Tools | LigandScout, GRID, LUDI | Generate structure-based pharmacophores from protein-ligand complexes |

| Ligand-Based Tools | Molecular Operating Environment (MOE), Pharmer, Align-it | Develop pharmacophore models from active ligand sets |

| Virtual Screening Platforms | Catalyst, Pharmit, PharmMapper | Screen compound libraries against pharmacophore models |

| Data Resources | RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB), DrugBank, ZINC Database | Source protein structures, active compounds, and screening libraries |

| Validation Tools | Decoy sets (DUD-E, DUDE-Z) | Assess model performance with known actives and inactives |

For structure-based pharmacophore modeling, a typical protocol involves: (1) retrieving and preparing the protein structure from PDB, including hydrogen addition and optimization; (2) identifying and characterizing the binding site using tools like GRID or LUDI; (3) generating interaction features from protein-ligand complexes or binding site analysis; (4) selecting essential features for the pharmacophore hypothesis; and (5) validating the model using known actives and decoys [7] [35].

For ligand-based pharmacophore modeling, standard methodology includes: (1) compiling and curating a set of known active compounds with diverse structures and potency data; (2) generating representative 3D conformations for each compound; (3) performing molecular alignment to identify common features; (4) creating the pharmacophore hypothesis based on conserved spatial features; and (5) validating the model with test compounds and refining based on performance [31] [32].

The comprehensive comparison of structure-based and ligand-based pharmacophore modeling approaches reveals a nuanced landscape where each methodology offers distinct advantages depending on available data and research objectives. Structure-based approaches provide superior performance when high-quality protein structures are available, particularly when derived from protein-ligand complexes that offer detailed interaction information. These methods directly incorporate spatial constraints from the binding site and can identify novel scaffold types not represented in existing ligand sets.

Ligand-based approaches demonstrate remarkable effectiveness when structural information for the target is limited or unavailable, leveraging the collective information embedded in known active compounds. These methods excel at identifying common functional features essential for activity and can successfully scaffold-hop to discover novel chemotypes that maintain these key interactions.

The benchmark evidence clearly indicates that pharmacophore-based virtual screening generally outperforms docking-based approaches in retrieving active compounds from large databases across diverse target types [1] [2]. This performance advantage, combined with typically lower computational requirements, positions pharmacophore modeling as a powerful first-line tool for virtual screening campaigns.

Ultimately, the most effective strategy for modern drug discovery involves the integrated application of both structure-based and ligand-based approaches, often in combination with docking and other computational methods. This multimodal strategy leverages the complementary strengths of each methodology, maximizing the probability of identifying novel, potent, and drug-like compounds for therapeutic development. As artificial intelligence and machine learning continue to advance, further refinement and integration of pharmacophore approaches will undoubtedly enhance their precision and utility in the ongoing quest for new therapeutic agents.

Molecular docking stands as a cornerstone technique in modern computational drug discovery, enabling researchers to predict how small molecules interact with biological targets at the atomic level. This methodology has evolved significantly from its initial rigid-body approximations to sophisticated algorithms that account for molecular flexibility, with profound implications for virtual screening accuracy. The fundamental objective of docking is to predict the three-dimensional structure of a protein-ligand complex and estimate the binding affinity, thereby identifying promising therapeutic candidates before costly experimental validation [36]. As docking methodologies have advanced, a critical question has emerged within computational pharmacology: how do these approaches compare to pharmacophore-based screening strategies in identifying biologically active compounds?

The transition from rigid to flexible docking represents one of the most significant technical advancements in the field. Early docking methods treated both proteins and ligands as rigid bodies, dramatically reducing computational complexity but oversimplifying the dynamic nature of biomolecular interactions [18]. This simplification often compromised accuracy, as both ligands and protein receptors undergo conformational changes upon binding—a phenomenon known as induced fit. Modern flexible docking approaches address this limitation by accounting for ligand flexibility and, in more advanced implementations, protein flexibility as well [18]. Understanding the capabilities, limitations, and appropriate application contexts of these different docking strategies is essential for researchers aiming to optimize their virtual screening pipelines, particularly when weighed against complementary pharmacophore-based methods.

Theoretical Foundations: From Rigid-Body to Flexible Docking Approaches

Rigid Docking: Foundations and Limitations

The earliest molecular docking approaches operated on the principle of rigid-body docking, which treats both the protein receptor and the ligand as fixed three-dimensional structures without internal flexibility. In this simplified model, the docking algorithm searches for the optimal alignment by exploring only six degrees of freedom—three translational and three rotational—much like fitting a key into a static lock [18]. This approach significantly reduces computational demands and enables rapid screening of compound libraries, making it practical for early virtual screening efforts when computational resources were limited.

However, the rigid-body assumption represents a significant simplification of biological reality. In actual binding processes, both ligands and proteins exhibit considerable flexibility, with bonds rotating and side chains adjusting to accommodate binding partners. The inability of rigid docking to account for these conformational changes often results in inaccurate pose predictions and unreliable binding affinity estimates, particularly for flexible ligands or proteins with binding sites that undergo substantial rearrangement upon ligand binding [18]. Despite these limitations, rigid docking remains useful for preliminary screening scenarios where the protein structure is known to be relatively static or when computational efficiency is paramount.

Flexible Docking: Accounting for Biological Reality

Ligand Flexibility

The first major advancement beyond rigid docking came with the incorporation of ligand flexibility, which acknowledges that small molecules can adopt multiple conformations when binding to protein targets. Modern docking programs typically account for ligand flexibility through various sampling strategies, including systematic torsion sampling, genetic algorithms, and Monte Carlo methods [36]. These approaches generate multiple ligand conformations during the docking process, evaluating which orientation best complements the binding site geometrically and energetically. The "anchor-and-grow" strategy employed by tools like DOCK6 represents one effective implementation, where a rigid core fragment is initially positioned followed by incremental rebuilding and conformational sampling of flexible substituents [37].

Receptor Flexibility

Accounting for protein flexibility remains one of the most significant challenges in molecular docking. Proteins are dynamic entities whose binding sites can undergo substantial conformational changes upon ligand binding—a phenomenon known as induced fit. Traditional docking struggles with these rearrangements, particularly in cross-docking scenarios where ligands are docked to receptor conformations different from their native bound states [18]. Several strategies have emerged to address protein flexibility, including:

- Ensemble Docking: Using multiple protein structures from different crystal forms or molecular dynamics simulations to represent conformational diversity

- Side-Chain Flexibility: Allowing rotation of amino acid side chains within the binding site while keeping the protein backbone fixed

- Backbone Flexibility: Incorporating limited backbone movements, though this substantially increases computational complexity

- Internal Coordinates: Using internal coordinate representations that naturally accommodate structural flexibility

Recent deep learning approaches have begun to transform flexible docking by using equivariant neural networks and diffusion models to predict conformational changes during binding [18]. Methods like FlexPose enable end-to-end flexible modeling of protein-ligand complexes regardless of input protein conformation (apo or holo), offering promising avenues for more accurate prediction of binding poses for challenging targets [18].

Comparative Performance: Rigid vs. Flexible Docking Strategies

Performance Metrics and Benchmarking Studies