Pharmacophore Modeling in Oncology Drug Discovery: A Comprehensive Guide to Targeting Cancer Mechanisms

This article provides a comprehensive overview of pharmacophore modeling and its pivotal role in modern oncology drug discovery.

Pharmacophore Modeling in Oncology Drug Discovery: A Comprehensive Guide to Targeting Cancer Mechanisms

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of pharmacophore modeling and its pivotal role in modern oncology drug discovery. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational concepts of pharmacophores as abstract descriptions of essential molecular features for biological activity. The content delves into both structure-based and ligand-based methodological approaches, illustrating their application through case studies on specific cancer targets like XIAP and ESR2. It further addresses critical challenges including conformational flexibility and model validation, while examining comparative advantages over other computational methods. The synthesis of current trends, including the integration of machine learning and MD simulations, offers a forward-looking perspective on optimizing targeted cancer therapies.

The Essential Blueprint: Unpacking Pharmacophore Concepts for Cancer Targets

The pharmacophore concept, established over a century ago, remains a cornerstone of modern rational drug design. This conceptual model has evolved from Paul Ehrlich's early ideas on specific molecular groups responsible for biological effects to the current International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) definition as "an ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or to block) its biological response" [1]. This whitepaper traces the historical development of the pharmacophore concept and demonstrates its practical application in contemporary oncology drug discovery through detailed methodologies, visualization of key workflows, and specific examples targeting cancer-related proteins. By integrating traditional computational approaches with emerging artificial intelligence (AI) technologies, pharmacophore modeling continues to provide powerful tools for identifying and optimizing novel therapeutics, particularly for challenging oncology targets where conventional discovery approaches often fail.

The conceptual foundation of the pharmacophore dates back to the late 19th century when Paul Ehrlich proposed that certain chemical groups within molecules are responsible for their biological effects [2]. Although Ehrlich himself used the term "toxophore" rather than "pharmacophore," his work established the fundamental principle that specific molecular features mediate biological activity [2]. The term "pharmacophore" emerged in the scientific literature in the 1960s, with F. W. Schueler using the expression "pharmacophoric moiety" and Lemont B. Kier popularizing the concept in publications between 1967-1971 [1] [2]. This early concept focused primarily on identifying key chemical groups responsible for biological activity.

A significant transformation occurred in the understanding and application of pharmacophores with Schueler's 1960 work, which extended the concept beyond specific chemical groups to spatial patterns of abstract features [2]. This evolution culminated in the 1998 IUPAC formalization of the modern pharmacophore definition, which emphasizes the ensemble of steric and electronic features necessary for optimal supramolecular interactions with biological targets [3] [1]. This abstract representation enables the identification of structurally diverse compounds that share the essential molecular interaction capacities required for binding to a common biological target, making pharmacophore approaches particularly valuable in scaffold hopping and lead optimization [4] [3].

Table 1: Historical Evolution of the Pharmacophore Concept

| Time Period | Key Contributor | Conceptual Focus | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Late 19th Century | Paul Ehrlich | Specific chemical groups ("toxophores") | Understanding structure-activity relationships |

| 1960s | F. W. Schueler | "Pharmacophoric moiety" | Bridging historical and modern concepts |

| 1967-1971 | Lemont B. Kier | Abstract molecular features | Early computational drug design |

| Post-1998 | IUPAC Definition | Ensemble of steric and electronic features | Modern computer-aided drug discovery |

In contemporary oncology drug discovery, pharmacophore modeling has become an indispensable tool, enabling researchers to target specific cancer-related proteins such as aromatase in breast cancer [5], XIAP in hepatocellular carcinoma [6], and VEGFR-2/c-Met in various malignancies [7]. The abstraction from specific chemical groups to general molecular features allows medicinal chemists to identify novel therapeutic candidates that would be overlooked by traditional similarity-based approaches, particularly valuable in addressing drug resistance and off-target toxicity in cancer treatment.

Core Principles and Feature Definitions

Essential Pharmacophore Features

The modern pharmacophore model represents key interaction patterns as abstract features rather than specific atoms or functional groups. This abstraction enables the recognition of bioisosteric replacements and scaffold-hopping opportunities, which are crucial for overcoming intellectual property constraints and optimizing drug properties. According to the IUPAC definition, these features represent the "ensemble of steric and electronic features" necessary for molecular recognition [3] [1].

The most fundamental pharmacophore features include hydrogen bond acceptors (HBA) and donors (HBD), which identify regions capable of forming directional hydrogen bonds with complementary protein residues [4] [3]. Hydrophobic (H) features represent aromatic or aliphatic regions that participate in van der Waals interactions and drive the burial of non-polar surface area upon binding. Charged features include positive ionizable (PI) and negative ionizable (NI) groups that form electrostatic interactions, while aromatic rings (AR) enable cation-π and π-π stacking interactions [4] [7]. Some advanced pharmacophore models also incorporate additional features such as metal-coordinating atoms (MB), halogen bond acceptors (XBD), and exclusion volumes (XVOL) that represent sterically forbidden regions [8] [9].

Table 2: Core Pharmacophore Features and Their Structural Correlates

| Feature Type | Structural Correlates | Interaction Type | Common Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Bond Acceptor (HBA) | Carbonyl, ether, nitro, sulfoxide groups | Directional hydrogen bonding | Feature projection points |

| Hydrogen Bond Donor (HBD) | Amine, amide, hydroxyl groups | Directional hydrogen bonding | Feature projection vectors |

| Hydrophobic (H) | Alkyl chains, aromatic rings | Van der Waals interactions | Spherical volumes |

| Positive Ionizable (PI) | Primary, secondary, tertiary amines | Electrostatic attraction | Charged spheres |

| Negative Ionizable (NI) | Carboxylic acid, tetrazole, phosphonate | Electrostatic attraction | Charged spheres |

| Aromatic Ring (AR) | Phenyl, pyridine, other aromatic systems | π-π stacking, cation-π | Ring plane projections |

| Exclusion Volume (XVOL) | Protein backbone and sidechain atoms | Steric hindrance | Forbidden regions |

Pharmacophore Model Typologies

Pharmacophore modeling approaches are broadly categorized into three methodologies based on available input data. Structure-based pharmacophore models are derived from three-dimensional structural information of the target protein, typically obtained from X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, or homology modeling [4] [6]. These models explicitly encode the steric and electronic features of the binding site, often including exclusion volumes that represent the shape complementarity requirements. Ligand-based pharmacophore models are generated when the protein structure is unknown but a set of active compounds is available [4] [3]. These approaches identify common molecular features and their spatial arrangements shared by known actives. Complex-based pharmacophore models represent a hybrid approach that utilizes structural data of protein-ligand complexes, providing the most comprehensive representation of interaction patterns [3].

Methodological Workflows in Pharmacophore Modeling

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

Structure-based pharmacophore modeling begins with the preparation of the target protein structure, which involves adding hydrogen atoms, assigning correct protonation states, and refining any structural inconsistencies [4] [6]. The binding site is then characterized using tools such as GRID or LUDI to identify regions favorable for specific interactions [4]. From this analysis, pharmacophore features are generated to represent the optimal interaction points within the binding site.

In a study targeting the X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP) for cancer therapy, researchers used the LigandScout software to generate a structure-based pharmacophore model from the XIAP protein complexed with a known inhibitor (PDB: 5OQW) [6]. The resulting model contained 14 chemical features: four hydrophobic features, one positive ionizable feature, three hydrogen bond acceptors, five hydrogen bond donors, and 15 exclusion volumes representing steric constraints [6]. This comprehensive model successfully captured the essential interactions necessary for high-affinity binding to XIAP.

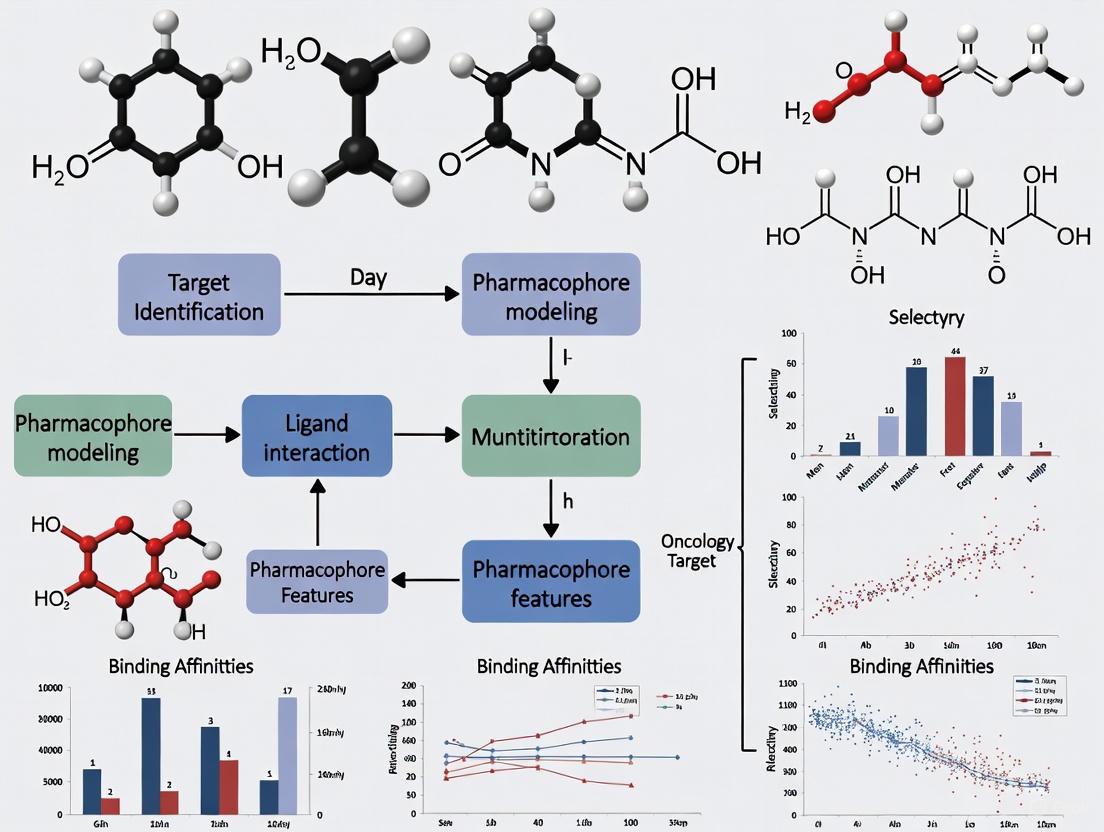

Diagram 1: Structure-based pharmacophore modeling workflow

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

When protein structural information is unavailable, ligand-based approaches provide a powerful alternative for pharmacophore model development. This methodology begins with the selection of a training set of biologically active compounds, ideally with diverse structural scaffolds but common mechanism of action [1]. Conformational analysis is then performed to generate a representative set of low-energy conformations for each compound. Molecular superimposition techniques are applied to identify the optimal alignment that maximizes the overlap of common chemical features [1]. The shared features are then abstracted into a pharmacophore hypothesis, which is validated for its ability to discriminate between active and inactive compounds.

The critical challenge in ligand-based pharmacophore modeling is the identification of the bioactive conformation, which may not correspond to the global energy minimum in the unbound state. To address this, most implementations consider multiple low-energy conformations and identify the common spatial arrangement of features that best explains the biological activity data [3] [1]. Advanced implementations incorporate activity cliffs (large changes in activity from small structural changes) to refine the model and identify features most critical for binding.

Model Validation Techniques

Rigorous validation is essential to ensure the predictive power of pharmacophore models. The most common validation approach measures the model's ability to enrich active compounds from decoy sets in virtual screening experiments [6] [7]. This is typically quantified using the enrichment factor (EF) and the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC-ROC) [7]. A model with EF1% > 10 and AUC > 0.9 is considered excellent, while models with AUC > 0.7 and EF > 2 are generally acceptable for virtual screening [7].

In the XIAP study, the structure-based pharmacophore model achieved an exceptional early enrichment factor (EF1%) of 10.0 with an AUC value of 0.98, demonstrating outstanding ability to distinguish true actives from decoys [6]. Additional validation approaches include testing the model against an external test set of known actives and inactives not used in model generation, and verifying that the model can correctly predict the activity of compounds with known structure-activity relationship data [7].

Experimental Protocols for Oncology Targets

Structure-Based Protocol: Targeting XIAP for Cancer Therapy

Objective: Identify natural product-derived inhibitors of XIAP for hepatocellular carcinoma treatment using structure-based pharmacophore modeling [6].

Protein Preparation:

- Retrieve XIAP crystal structure (PDB: 5OQW) from Protein Data Bank

- Remove water molecules and add hydrogen atoms using Discovery Studio

- Correct missing residues and optimize hydrogen bonding network

- Energy minimization using CHARMM force field

Pharmacophore Generation:

- Generate structure-based pharmacophore using LigandScout 4.3

- Identify key interaction features: HBD, HBA, hydrophobic, positive ionizable

- Define exclusion volumes based on protein binding site shape

- Select critical features contributing to binding energy

Virtual Screening:

- Screen ZINC natural compound database (~230,000 compounds)

- Apply Lipinski's Rule of Five and Veber's criteria for drug-likeness

- Filter compounds matching ≥ 4 pharmacophore features

- Evaluate ADMET properties (absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, toxicity)

Validation:

- Test model against 10 known XIAP antagonists and 5199 decoy compounds from DUD-E

- Calculate enrichment factor and AUC-ROC values

- Molecular docking of top hits to verify binding modes

- Molecular dynamics simulations (100 ns) to confirm complex stability

This protocol identified three natural compounds (Caucasicoside A, Polygalaxanthone III, and MCULE-9896837409) as promising XIAP inhibitors with potential for further development as anticancer agents [6].

Dual-Target Protocol: Targeting VEGFR-2 and c-Met in Cancer

Objective: Identify dual-target inhibitors of VEGFR-2 and c-Met to overcome resistance in cancer therapy [7].

Data Collection:

- Collect 18 VEGFR-2 and 47 c-Met crystal structures from PDB

- Select 10 VEGFR-2 and 8 c-Met complexes based on resolution (< 2.0 Ã…) and biological activity

- Prepare validation sets: 25 active inhibitors and 375 inactive compounds per target from DUD-E

Parallel Pharmacophore Development:

- Generate structure-based pharmacophores for each target using Discovery Studio

- Set parameters: 4-6 features, include HBA, HBD, hydrophobic, aromatic, ionizable features

- Validate models using enrichment calculations (EF and AUC)

- Select top pharmacophore hypothesis for each target based on validation metrics

Virtual Screening:

- Filter 1.28 million compounds (ChemDiv database) using Lipinski and Veber rules

- Screen against both VEGFR-2 and c-Met pharmacophores

- Select compounds matching both pharmacophore models

- Evaluate ADMET properties and structural diversity

Hit Confirmation:

- Molecular docking of dual hits against both targets

- Select 18 compounds with best binding affinities for both VEGFR-2 and c-Met

- Molecular dynamics simulations (100 ns) for top 2 compounds

- MM/PBSA calculations to determine binding free energies

This integrated approach identified compound17924 and compound4312 as promising dual-target inhibitors with superior binding free energies compared to reference compounds [7].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Pharmacophore-Based Screening

| Reagent/Resource | Type | Function in Pharmacophore Modeling | Example Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Database | Source of 3D protein structures for structure-based modeling | RCSB PDB [4] |

| ZINC Database | Compound Library | Curated collection of commercially available compounds for virtual screening | ZINC [6] |

| DUD-E Database | Validation Set | Directory of useful decoys for method validation and benchmarking | DUD-E [6] |

| LigandScout | Software | Structure-based pharmacophore generation and visualization | Intel:Ligand [6] |

| Discovery Studio | Software Suite | Comprehensive environment for pharmacophore modeling and screening | BIOVIA [7] |

| CHARMM Force Field | Computational Method | Energy minimization and molecular dynamics simulations | Academic [6] |

| ChemPLP Scoring | Algorithm | Docking pose evaluation and ranking | PLANTS [10] |

Advanced Applications in Oncology Research

AI-Enhanced Pharmacophore Modeling

Recent advances in artificial intelligence are revolutionizing pharmacophore approaches. The DiffPhore framework represents a cutting-edge application of deep learning to pharmacophore modeling, implementing a knowledge-guided diffusion framework for 3D ligand-pharmacophore mapping [8]. This approach leverages two specialized datasets: CpxPhoreSet (derived from experimental protein-ligand complexes) and LigPhoreSet (containing perfectly-matched ligand-pharmacophore pairs from diverse chemical space) [8].

The DiffPhore architecture consists of three innovative modules: a knowledge-guided ligand-pharmacophore mapping encoder that incorporates type and directional alignment rules; a diffusion-based conformation generator that estimates translation, rotation, and torsion transformations; and a calibrated conformation sampler that reduces exposure bias in the iterative generation process [8]. When benchmarked against traditional methods, DiffPhore demonstrated superior performance in predicting binding conformations and exhibited powerful virtual screening capabilities for lead discovery and target fishing [8].

Emerging Shape-Focused Approaches

Shape-focused pharmacophore modeling represents another significant advancement in the field. The O-LAP algorithm introduces a novel graph clustering approach that generates cavity-filling models by aggregating overlapping atomic content from docked active ligands [10]. This method transforms the traditional feature-based paradigm by emphasizing shape complementarity as the primary screening criterion.

The O-LAP workflow involves filling the protein binding site with top-ranked docked active ligands, removing non-polar hydrogen atoms, and applying pairwise distance-based graph clustering to group overlapping atoms with matching types into representative centroids [10]. The resulting models can be optimized using enrichment-driven greedy search algorithms and have demonstrated remarkable effectiveness in both docking rescoring and rigid docking scenarios across multiple challenging drug targets [10].

Diagram 2: Shape-focused pharmacophore modeling with O-LAP

The pharmacophore concept has undergone substantial evolution from Ehrlich's original focus on specific chemical groups to the modern IUPAC definition emphasizing abstract molecular interaction features. This conceptual framework has proven exceptionally durable and adaptable, maintaining its relevance across more than a century of scientific advancement. In contemporary oncology drug discovery, pharmacophore modeling provides powerful computational approaches for targeting challenging proteins such as XIAP, VEGFR-2, c-Met, and mutant ESR2 in breast cancer [5] [6] [7].

The integration of pharmacophore modeling with complementary computational techniques—including molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulations, and virtual screening—creates a robust framework for identifying and optimizing novel therapeutic candidates [6] [7]. Emerging technologies, particularly AI-enhanced approaches like DiffPhore and shape-focused methods like O-LAP, are further expanding the capabilities of pharmacophore modeling [8] [10]. These advancements promise to accelerate the discovery of innovative cancer therapeutics by enabling more efficient exploration of chemical space and more accurate prediction of bioactive conformations.

As the field progresses, pharmacophore modeling will continue to evolve, incorporating more sophisticated representations of molecular interactions and leveraging the growing availability of structural and bioactivity data. This progression ensures that the foundational concept of the pharmacophore will remain essential to rational drug design, particularly in addressing the persistent challenges of oncology drug discovery, including drug resistance, off-target toxicity, and tumor heterogeneity.

A pharmacophore is defined as the "ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or to block) its biological response" [3] [4]. This abstract concept represents the essential molecular interaction capacities of compounds that share biological activity toward a specific target, independent of their chemical scaffold [3] [11]. In modern drug discovery, particularly in oncology, pharmacophore modeling serves as a critical tool for identifying and optimizing novel therapeutic agents by focusing on these key features [4] [6].

The fundamental principle underlying pharmacophore modeling is that compounds binding to the same biological target often share common chemical functionalities arranged in a specific three-dimensional orientation [3] [12]. These features include hydrogen bond donors and acceptors, hydrophobic regions, aromatic rings, positively and negatively ionizable groups, and metal-binding sites [4] [11]. The spatial relationships between these features create a unique pattern that complements the target's binding site, enabling high-affinity interactions [13]. This review focuses on three core pharmacophoric features—hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions, and aromatic interactions—within the context of oncology target research, providing detailed methodologies for their identification and application in cancer drug discovery.

Core Pharmacophoric Features: Definitions and Quantitative Parameters

Hydrogen Bond Donors and Acceptors

Hydrogen bond donors (HBD) and hydrogen bond acceptors (HBA) are crucial for forming specific, directional interactions between ligands and proteins [14]. These features facilitate molecular recognition through electrostatic attractions and play a pivotal role in determining binding affinity and selectivity [3] [11].

Hydrogen Bond Donors are typically characterized by hydrogen atoms bound to electronegative atoms (most commonly oxygen or nitrogen) that can participate in non-covalent bonding with acceptor atoms [11]. In pharmacophore modeling, HBD features are represented as vectors pointing from the hydrogen atom toward the expected direction of interaction [13].

Hydrogen Bond Acceptors are usually electronegative atoms (such as oxygen, nitrogen, or sulfur) with available lone electron pairs that can form interactions with hydrogen atoms [11]. These are represented as vectors pointing away from the acceptor atom along the expected direction of lone pair availability [13].

The geometry of hydrogen bonds follows specific distance and angular parameters that optimize electrostatic interactions. As revealed in analyses of protein-ligand complexes, optimal hydrogen bond distances generally range from 2.7-3.3 Å between donor and acceptor atoms, with angles typically greater than 120° for optimal interaction strength [14].

Table 1: Geometric Parameters of Hydrogen Bonds in Protein-Ligand Complexes

| Parameter | Optimal Range | Measurement Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Distance (D-A) | 2.7 - 3.3 Ã… | Between donor and acceptor atoms |

| Donor Angle | >120° | Angle at hydrogen donor atom |

| Acceptor Angle | >120° | Angle at acceptor atom |

| Feature Tolerance | 1.0 - 1.5 Ã… | Radius in pharmacophore models |

Hydrophobic Regions

Hydrophobic features represent non-polar regions of molecules that participate in van der Waals interactions and drive the desolvation and exclusion of water from binding interfaces [14] [11]. These features are critical for the overall binding energy through the hydrophobic effect, which provides a significant entropic contribution to ligand-receptor association [14].

In pharmacophore modeling, hydrophobic regions are typically mapped as points in three-dimensional space corresponding to the centers of hydrophobic moieties such as aliphatic chains, cycloalkyl rings, or the centroids of aromatic systems [11]. The spatial arrangement of these hydrophobic centers helps define the molecular shape complementarity between the ligand and the binding pocket [13].

Key characteristics of hydrophobic features include:

- Location at the center of hydrophobic molecular regions

- Interaction radius of approximately 1.0-1.5 Ã… in pharmacophore models

- Preference for interaction with non-polar amino acid side chains (e.g., leucine, valine, isoleucine, phenylalanine)

- Contribution to membrane permeability and pharmacokinetic properties

Aromatic Interactions

Aromatic interactions, particularly π-π stacking, play vital roles in biological recognition and organization of biomolecular structures [14]. These interactions contribute significantly to binding affinity in many protein-ligand complexes, especially in oncology targets where aromatic residues frequently populate binding sites [14].

Aromatic interactions in pharmacophore models are represented by the ring aromatic (RA) feature, which captures the geometry of π-π stacking, cation-π interactions, and other ring-based contacts [11]. The geometry of π-π stacking follows two predominant patterns observed in experimental structures of ligand-protein complexes:

- Parallel/Offset Stacking: Characterized by approximately parallel ring planes with a center-to-center distance of 4.5-5.5 Å and a small interplanar angle (typically <30°)

- Perpendicular/T-Shaped Stacking: Features rings oriented approximately perpendicular to each other (interplanar angle of 60-90°) with a center-to-center distance of 5.0-6.5 Å

Table 2: Geometric Parameters of Aromatic Interactions in Protein-Ligand Complexes

| Interaction Type | Distance Range | Angle Range | Energetic Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parallel π-π | 4.5 - 5.5 Å | <30° | -2 to -3 kcal/mol |

| Perpendicular π-π | 5.0 - 6.5 Å | 60-90° | -1 to -2 kcal/mol |

| Cation-Ï€ | 4.0 - 6.0 Ã… | Variable | -3 to -8 kcal/mol |

| Feature Tolerance | 1.2 - 1.7 Å | 30° | Radius in pharmacophore models |

Statistical analyses of protein-ligand complexes reveal that perpendicular and offset-parallel configurations represent the dominant geometries of π-π interactions at biological interfaces, consistent with theoretical calculations indicating these arrangements correspond to energy minima of comparable depth [14].

Experimental and Computational Methodologies

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling Protocol

Structure-based pharmacophore modeling relies on three-dimensional structural information of the target protein, typically obtained from X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, or homology modeling [4] [6]. This approach is particularly valuable for oncology targets with available crystal structures.

Diagram: Structure-based pharmacophore modeling workflow for identifying key interaction features from protein structures.

Step 1: Protein Structure Preparation

- Source: Obtain 3D structure from Protein Data Bank (PDB) or through homology modeling [4] [6]

- Processing: Add hydrogen atoms, assign proper protonation states, and optimize hydrogen bonding networks using tools like MOE or Discovery Studio [15] [6]

- Quality Assessment: Evaluate resolution, missing residues, and stereochemical parameters [4]

Step 2: Binding Site Identification

- Detection Methods: Use computational tools like GRID or LUDI to identify potential binding pockets [4]

- Site Characterization: Analyze physicochemical properties, residue conservation, and known mutagenesis data [4]

- Validation: Compare with experimentally determined binding sites from co-crystal structures when available [6]

Step 3: Pharmacophore Feature Generation

- Interaction Analysis: Identify key interaction points between protein and bound ligands [6]

- Feature Mapping: Translate protein-ligand interactions into pharmacophore features using software such as LigandScout [15] [6]

- Exclusion Volumes: Add exclusion volumes to represent steric constraints of the binding pocket [4]

Step 4: Feature Selection and Model Refinement

- Conservation Analysis: Select features that are conserved across multiple complexes or are critical for binding [4]

- Energy Considerations: Prioritize features that contribute significantly to binding energy [4]

- Spatial Constraints: Define distance and angle tolerances based on observed interactions [13]

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling Protocol

Ligand-based pharmacophore modeling is employed when the 3D structure of the target protein is unknown, relying on a set of known active compounds to derive common chemical features [3] [11].

Diagram: Ligand-based pharmacophore modeling workflow for extracting common features from active compounds.

Step 1: Compound Selection and Preparation

- Dataset Curation: Collect structurally diverse compounds with known activity against the target [11]

- Chemical Space: Include compounds spanning a range of potencies (e.g., IC50 values) [15]

- Structure Preparation: Generate 3D structures, assign proper stereochemistry, and optimize geometries using force fields like MMFF94 [15]

Step 2: Conformational Analysis

- Conformer Generation: Use systematic search, Monte Carlo, or molecular dynamics methods to explore conformational space [11]

- Bioactive Conformation: Aim to sample the bioactive conformation through energy minimization and diverse sampling [11]

- Software Tools: Utilize Catalyst, MOE, or OMEGA to generate representative conformers [11]

Step 3: Molecular Alignment and Common Feature Identification

- Alignment Methods: Employ point-based or property-based techniques to superimpose compounds [11]

- Feature Detection: Identify common HBA, HBD, hydrophobic, and aromatic features across aligned molecules [11]

- Algorithm Selection: Use HipHop for qualitative models or HypoGen for quantitative models incorporating activity data [11]

Pharmacophore Model Validation Protocols

Validation is crucial to ensure the quality and predictive power of pharmacophore models before application in virtual screening [6] [13].

Internal Validation Methods

- ROC Curve Analysis: Generate receiver operating characteristic curves to evaluate model selectivity [6]

- Enrichment Factors: Calculate early enrichment (EF1%) to assess ability to identify actives in early screening stages [6]

- Cross-Validation: Perform leave-one-out or bootstrapping to test model robustness [13]

External Validation Methods

- Test Set Screening: Use an independent set of active and inactive compounds not included in model generation [13]

- Decoy Sets: Employ databases like DUD-E containing decoy molecules with similar physicochemical properties but different 2D topology [15] [6]

- Performance Metrics: Calculate AUC values, sensitivity, specificity, and precision [6] [13]

Table 3: Validation Metrics for Pharmacophore Model Assessment

| Metric | Calculation | Acceptance Criteria | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| AUC | Area under ROC curve | >0.7 (Good), >0.9 (Excellent) | Overall model performance |

| EF1% | (Hitssampled/ð‘sampled)/(Hitstotal/ð‘total) at 1% | >5 (Moderate), >10 (Good) | Early enrichment capability |

| Sensitivity | TP/(TP+FN) | >0.7 | Ability to identify true actives |

| Specificity | TN/(TN+FP) | >0.7 | Ability to reject inactives |

| GH Score | Guner-Henry score | >0.7 | Overall model quality |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Table 4: Essential Software Tools for Pharmacophore Modeling in Oncology Research

| Tool Name | Type | Key Functionality | Application in Oncology |

|---|---|---|---|

| LigandScout | Commercial | Structure & ligand-based modeling, virtual screening | XIAP inhibitor identification [15] [6] |

| MOE | Commercial | Molecular modeling, conformational analysis, QSAR | Kinase inhibitor optimization [3] [15] |

| Discovery Studio | Commercial | Comprehensive drug discovery suite, pharmacophore modeling | HDAC inhibitor development [3] [13] |

| Catalyst/HypoGen | Commercial | Ligand-based model generation with activity prediction | HSP90 inhibitor discovery [11] |

| Phase | Commercial | 3D pharmacophore modeling, virtual screening | Kinase inhibitor screening [3] |

| ZINCPharmer | Free | Pharmacophore-based screening of ZINC database | Natural product screening [13] |

| Lavendomycin | Lavendomycin, MF:C29H50N10O8, MW:666.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Camaric acid | Camaric acid, MF:C35H52O6, MW:568.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Table 5: Research Databases and Reagents for Pharmacophore-Based Screening

| Resource | Type | Content/Application | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| RCSB PDB | Database | Protein-ligand complex structures | Public [4] |

| ZINC Database | Database | Commercially available compounds for virtual screening | Public [6] |

| ChEMBL | Database | Bioactive molecules with drug-like properties | Public [6] |

| DUD-E | Database | Directory of useful decoys for validation | Public [15] |

| AfroCancer Database | Database | Natural products from African medicinal plants | Research use [15] |

| NPACT | Database | Naturally occurring plant-based anticancer compounds | Public [15] |

Application in Oncology Target Research: Case Study of XIAP Inhibition

The X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP) represents an important oncology target where pharmacophore modeling has successfully identified novel inhibitors [6]. XIAP overexpression decreases apoptosis in cancer cells, contributing to chemotherapy resistance, making it a promising target for cancer treatment [6].

In a recent study, structure-based pharmacophore modeling was employed to identify natural product inhibitors of XIAP [6]. The methodology included:

Target Preparation

- Retrieved XIAP crystal structure (PDB: 5OQW) complexed with a known inhibitor

- Prepared protein structure by adding hydrogens, optimizing hydrogen bonding, and assigning charges

Pharmacophore Model Generation

- Used LigandScout to generate initial pharmacophore features from protein-ligand interactions

- Identified 14 initial chemical features including hydrophobics, positive ionizable, H-bond acceptors, and H-bond donors

- Refined to essential features: 4 hydrophobic, 1 positive ionizable, 3 H-bond acceptors, 5 H-bond donors

- Added exclusion volumes to represent steric constraints of the binding pocket

Model Validation

- Validated using 10 known active XIAP antagonists and 5199 decoy compounds from DUD-E

- Achieved excellent AUC value of 0.98 and early enrichment factor (EF1%) of 10.0

- Demonstrated high capability to distinguish true actives from decoys

Virtual Screening and Hit Identification

- Screened ZINC natural product database using validated pharmacophore model

- Identified hit compounds including Caucasicoside A, Polygalaxanthone III, and MCULE-9896837409

- Confirmed stability through molecular dynamics simulations

- Proposed as lead compounds for XIAP-related cancer treatment

This case study demonstrates how pharmacophore modeling integrating hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic, and aromatic features can successfully identify novel oncology drug candidates with potential to overcome limitations of conventional chemotherapy.

The strategic integration of hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions, and aromatic interactions in pharmacophore modeling provides a powerful framework for oncology drug discovery. These core features represent fundamental molecular recognition elements that drive target engagement and biological activity. As computational methods advance, particularly through integration with machine learning and improved handling of protein flexibility, pharmacophore approaches will continue to evolve in sophistication and predictive power. For oncology researchers, these methodologies offer rational strategies to identify and optimize novel therapeutic agents targeting critical cancer pathways, ultimately contributing to more effective and selective cancer treatments.

In the realm of oncology drug discovery, pharmacophore modeling has emerged as an indispensable computational approach for targeting the specific molecular drivers of cancer. The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) defines a pharmacophore as "an ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target and to trigger (or block) its biological response" [1] [3]. This abstract representation captures the essential molecular interaction capabilities of compounds without being constrained to specific chemical scaffolds, making it particularly valuable for identifying novel therapeutic agents against cancer targets.

In oncology, two particularly promising applications of pharmacophores include targeting overexpressed proteins that drive tumor progression and restoring defective apoptosis that allows cancer cells to evade programmed cell death. Pharmacophore models provide a strategic framework for addressing these pathological mechanisms by enabling the identification of compounds that can selectively inhibit overexpressed oncoproteins or reactivate apoptotic pathways in malignant cells [9] [6]. The power of this approach lies in its ability to facilitate scaffold hopping—identifying structurally diverse compounds that share the same essential interaction features—thus expanding the chemical space for potential cancer therapeutics beyond known chemotypes [16].

Pharmacophore Fundamentals: Features and Modeling Approaches

Core Pharmacophore Features

Pharmacophore models are built from a set of fundamental chemical features responsible for molecular recognition between a ligand and its biological target. The core features utilized in pharmacophore modeling include [1] [3]:

- Hydrogen bond donors (HBD) and acceptors (HBA): Features representing the capacity to form hydrogen bonds with complementary targets

- Hydrophobic interactions (HPho): Features capturing van der Waals interactions and lipid-soluble contacts

- Aromatic rings (Ar): Features enabling π-π stacking and cation-π interactions

- Charged/ionizable groups: Positively or negatively charged features for electrostatic interactions

- Halogen bond donors (XBD): Features representing halogen-specific interactions

These abstract features allow pharmacophore models to transcend specific chemical functionalities and identify diverse compounds capable of similar molecular interactions with biological targets—a particularly valuable capability in oncology where chemical novelty is often essential for overcoming resistance mechanisms [3].

Pharmacophore Modeling Methodologies

Three primary approaches are employed for developing pharmacophore models, each with distinct advantages for oncology applications:

Structure-based pharmacophore modeling: Derived from analysis of target-ligand complexes, typically from X-ray crystallography or NMR structures. This approach directly captures the essential interactions between a ligand and its protein target [6] [17]. For example, in targeting the X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP), a structure-based pharmacophore model was generated from a crystal structure (PDB: 5OQW) complexed with a known inhibitor, identifying 14 key chemical features including hydrophobics, hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, and a positive ionizable feature [6].

Ligand-based pharmacophore modeling: Developed from a set of known active compounds when structural information of the target is unavailable. This approach identifies common molecular features shared by active ligands and establishes their spatial relationships [1] [3].

Complex-based approaches: Integrate information from both target structures and multiple ligands, providing a comprehensive view of interaction possibilities, especially valuable for targets with multiple binding modes [3].

Table 1: Comparison of Pharmacophore Modeling Approaches in Oncology

| Modeling Approach | Data Requirements | Strengths | Oncology Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structure-Based | Target-ligand complex structure | Directly captures biologically relevant interactions | Targeting proteins with known structures (e.g., XIAP, ESR2) |

| Ligand-Based | Set of active compounds | Applicable when target structure is unknown | Targeting proteins with known ligands but unknown structures |

| Complex-Based | Multiple target-ligand complexes | Captures binding flexibility and multiple modes | Targets with conformational flexibility or multiple binding sites |

Targeting Overexpressed Proteins in Oncology: ESR2 Case Study

Biological Context and Rationale

In breast cancer, a leading cause of cancer mortality among women, mutations and overexpression of estrogen receptor beta (ESR2)—particularly in the ligand-binding domain—contribute to altered signaling pathways and uncontrolled cell growth [9]. Approximately 70% of breast cancers exhibit mutations in estrogen receptors, making them prime targets for endocrine therapy. However, long-term exposure often leads to resistance, necessitating the development of novel drugs targeting ESR2 mutations [9].

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling Protocol

A recent study employed structure-based pharmacophore modeling to identify inhibitors targeting mutant ESR2 proteins [9]:

Protein Structure Retrieval: Three mutant ESR2 protein structures (PDB ID: 2FSZ, 7XVZ, and 7XWR) were retrieved from the Protein Data Bank with specific criteria: Homo sapiens source, X-ray diffraction method, and refinement resolution of 2.0-2.5 Ã… [9].

Shared Feature Pharmacophore Generation: Individual pharmacophores were constructed for each co-crystallized ligand using structure-based pharmacophore module in LigandScout software. The shared feature pharmacophore (SFP) model was generated by combining individual pharmacophores, resulting in a model with 11 features: HBD (2), HBA (3), HPho (3), Ar (2), and XBD (1) [9].

Virtual Screening: An in-house Python script distributed the 11 features into 336 combinations used as queries to screen a library of 41,248 compounds from ZINCPharmer [9].

Hit Identification and Validation: Virtual screening identified 33 hits with potential pharmacophoric fit scores and low RMSD values. The top four compounds (ZINC94272748, ZINC79046938, ZINC05925939, and ZINC59928516) showed fit scores >86% and satisfied Lipinski's rule of five. Molecular docking against wild-type ESR2 (PDB: 1QKM) revealed binding affinities ranging from -5.73 to -10.80 kcal/mol, outperforming the control (-7.2 kcal/mol) [9].

Molecular Dynamics Validation: The stability of selected candidates was confirmed through 200 ns molecular dynamics simulations and MM-GBSA analysis, identifying ZINC05925939 as a promising ESR2 inhibitor for further development [9].

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for developing ESR2-targeted pharmacophore models and identifying inhibitors for breast cancer.

Restoring Defective Apoptosis: Targeting XIAP in Cancer

Biological Context and Rationale

X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP) is a key anti-apoptotic protein that neutralizes caspase-3, -7, and -9, effectively blocking programmed cell death [6]. Overexpression of XIAP decreases apoptosis in cancer cells, contributing to tumor development and chemotherapy resistance. In hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)—the fourth most common cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide—targeting XIAP represents a promising strategy to restore apoptotic function in malignant cells [6].

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling Protocol

A comprehensive study employed structure-based pharmacophore modeling to identify natural XIAP inhibitors [6]:

Protein Preparation: The XIAP crystal structure (PDB: 5OQW) in complex with a known inhibitor (Hydroxythio Acetildenafil, PubChem CID: 46781908) was prepared using the Protein Preparation Wizard in Schrödinger Maestro. The process included adding hydrogen atoms, assigning bond orders, creating disulfide bonds, and optimizing hydrogen bonds followed by constrained energy minimization (OPLS3 force field) until RMSD reached 0.3 Å [6].

Pharmacophore Generation: Structure-based pharmacophore generation using LigandScout identified 14 key chemical features: 4 hydrophobic, 1 positive ionizable, 3 hydrogen bond acceptors, 5 hydrogen bond donors, and 15 exclusion volumes [6].

Model Validation: The pharmacophore model was validated using 10 known active XIAP antagonists and 5199 decoy compounds from the DUD-E database. The model demonstrated excellent discriminatory power with an AUC value of 0.98 and early enrichment factor (EF1%) of 10.0, confirming its ability to distinguish active from inactive compounds [6].

Virtual Screening and Hit Identification: The validated model screened natural compound databases, identifying three promising candidates—Caucasicoside A (ZINC77257307), Polygalaxanthone III (ZINC247950187), and MCULE-9896837409 (ZINC107434573)—which demonstrated stable binding in molecular dynamics simulations and potential as lead compounds for XIAP-related cancers [6].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Oncology Pharmacophore Studies

| Research Reagent | Specific Tool/Software | Application in Workflow | Key Functionality |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Structure Database | Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Target identification and preparation | Source of 3D protein structures for structure-based modeling |

| Pharmacophore Modeling | LigandScout, Schrödinger PHASE | Pharmacophore generation and screening | Structure-based and ligand-based pharmacophore development |

| Compound Libraries | ZINC, SuperNatural 3.0 | Virtual screening | Source of commercially available and natural compounds for screening |

| Docking Software | Glide (Schrödinger), AutoDock | Binding mode analysis and validation | Molecular docking to predict binding poses and affinities |

| Dynamics Software | AMBER, GROMACS, Desmond | Conformational stability assessment | Molecular dynamics simulations to validate complex stability |

| Validation Tools | DUD-E Decoy Finder | Model validation | Generation of decoy sets for pharmacophore model validation |

Advanced Methodologies and Emerging Approaches

Integrating Molecular Dynamics with Pharmacophore Modeling

The static nature of traditional structure-based pharmacophore modeling can be overcome by integrating molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, which capture the dynamic behavior of protein-ligand complexes [18]. Recent approaches generate pharmacophore models from multiple snapshots along MD trajectories, creating a comprehensive ensemble of possible interaction patterns. The Hierarchical Graph Representation of Pharmacophore Models (HGPM) provides an intuitive visualization of numerous pharmacophore models from extended MD simulations, emphasizing their relationships and feature hierarchy [18]. This approach is particularly valuable for allosteric targets or proteins with significant conformational flexibility common in oncology targets.

Quantitative Pharmacophore Activity Relationship (QPhAR)

A novel methodology termed Quantitative Pharmacophore Activity Relationship (QPhAR) enables the construction of predictive quantitative models directly from pharmacophore features [16]. Unlike traditional qualitative pharmacophore screening, QPhAR establishes continuous relationships between pharmacophore feature arrangements and biological activity values, allowing for activity prediction of novel compounds. This approach demonstrates particular robustness with small dataset sizes (15-20 training samples), making it valuable for early-stage oncology drug discovery projects where limited active compounds are available [16].

Machine Learning-Enhanced Pharmacophore Optimization

The integration of machine learning algorithms with pharmacophore modeling has created new opportunities for automated model optimization and hit identification [19]. Recent approaches use SAR information extracted from validated QPhAR models to automatically select features that drive pharmacophore model quality, reducing the reliance on manual expert curation. These automated workflows can derive optimized pharmacophores from input datasets and provide insights into favorable and unfavorable interactions for compounds of interest [19].

Figure 2: Integrated workflow combining advanced methodologies for pharmacophore-based drug discovery in oncology.

Pharmacophore modeling represents a powerful strategy for addressing two fundamental challenges in oncology: targeting overexpressed proteins and restoring defective apoptosis. The case studies targeting ESR2 in breast cancer and XIAP in hepatocellular carcinoma demonstrate how structure-based pharmacophore approaches can identify novel inhibitors with therapeutic potential. The continuing evolution of pharmacophore methodologies—including integration with molecular dynamics, development of quantitative approaches, and implementation of machine learning optimization—promises to further enhance the efficiency and success rate of oncology drug discovery.

As these computational approaches become increasingly sophisticated and accessible, pharmacophore modeling is poised to remain an essential component of the oncology drug discovery toolkit, enabling researchers to efficiently navigate complex chemical and biological spaces to identify promising therapeutic candidates for some of the most challenging cancer targets.

A pharmacophore is defined as the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or to block) its biological response [13]. In simpler terms, it is an abstract model that distills the essential chemical functionalities a molecule must possess to interact with its target, without including the specific molecular scaffold itself. This concept is foundational in medicinal chemistry, providing a framework for understanding the essential features of ligands that interact with biological targets, which is particularly critical in oncology research where targeting specific pathways can lead to more effective and less toxic treatments [20]. The core value of a pharmacophore model lies in its ability to guide the identification and optimization of novel drug candidates by focusing on the key molecular features responsible for biological activity, thereby streamlining the drug discovery process and reducing associated time and costs [13].

The terms "pharmacophore" and "binding site" are often discussed together, but they represent complementary perspectives on the same interaction event. While the pharmacophore focuses on the ligand, representing the essential features of active compounds that interact with the target, the binding site refers to the complementary region on the target protein that accommodates the ligand and forms specific interactions [13]. Understanding this distinction is crucial for researchers: the pharmacophore is a hypothesis about what elements are required for activity, derived from ligands or the target structure, whereas the binding site is the physical location on the protein where these interactions manifest. In successful drug design, especially for oncology targets, the pharmacophore derived from active ligands or protein structures must map precisely onto the binding site to facilitate molecular recognition and binding [13].

Core Terminology and Fundamental Features

Essential Pharmacophoric Features

Pharmacophore models are constructed from key chemical features that facilitate non-covalent interactions between a ligand and its biological target. These features represent the fundamental language of molecular recognition. The following table summarizes the core pharmacophoric features and their roles in molecular interactions.

Table 1: Essential Pharmacophoric Features and Their Characteristics

| Feature Type | Symbol | Description | Role in Molecular Recognition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Bond Acceptor | HA | Atom that can accept a hydrogen bond (e.g., O, N) | Forms specific, directional interactions with hydrogen bond donors in the binding site [8]. |

| Hydrogen Bond Donor | HD | Atom with a hydrogen that can donate a hydrogen bond (e.g., OH, NH) | Forms specific, directional interactions with hydrogen bond acceptors in the binding site [8]. |

| Hydrophobic | HY | Non-polar atom or region (e.g., alkyl chains) | Drives association via entropic effects and van der Waals forces, often in pocket sub-sites [21] [8]. |

| Aromatic Ring | AR | Planar, conjugated ring system | Participates in cation-π, π-π stacking, and hydrophobic interactions [21] [8]. |

| Positive Ionizable | PI | Atom or group that can carry a positive charge (e.g., amine) | Engages in strong electrostatic interactions with negatively charged groups [13] [8]. |

| Negative Ionizable | NI | Atom or group that can carry a negative charge (e.g., carboxylate) | Engages in strong electrostatic interactions with positively charged groups [13] [8]. |

| Exclusion Volume | EX | Region in space occupied by the protein | Represents steric hindrance, preventing ligand atoms from occupying this space [8]. |

These features are not merely present or absent; their spatial arrangement and distances between them are critical for determining the specificity and affinity of ligand-target interactions [13]. A pharmacophore model quantitatively defines the allowed spatial relationships, including distances, angles, and tolerances, between these features to create a three-dimensional query that can be used to search for new potential drugs.

Pharmacophore versus Binding Site: A Critical Distinction

A clear understanding of the difference between a pharmacophore and a binding site is fundamental to rational drug design. The following table outlines the key distinctions.

Table 2: Pharmacophore vs. Binding Site

| Aspect | Pharmacophore | Binding Site |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | An abstract model of essential ligand features for biological activity [13]. | A physical cavity or region on the target protein where ligand binding occurs [13]. |

| Perspective | Ligand-centric. | Target-centric. |

| Composition | A set of chemical feature types (HBA, HBD, Hy, etc.) with 3D constraints. | Amino acid residues, their side chains, and backbone atoms forming a specific 3D environment. |

| Representation | Points, vectors, and exclusion spheres in 3D space. | A structural, atomic-resolution 3D coordinate set. |

| Role in Drug Discovery | Serves as a hypothesis for virtual screening and lead optimization [13]. | Provides a structural template for structure-based design methods like docking [22]. |

The relationship between these two concepts is symbiotic. The binding site presents a unique chemical environment, and the pharmacophore is a hypothesis about which ligand features complement this environment to achieve high-affinity binding. In structure-based drug design, the binding site is analyzed to generate a pharmacophore hypothesis, which can then be used to find or design new molecules that match this hypothesis [13].

Methodological Approaches: Building the Pharmacophore Model

Ligand-Based and Structure-Based Strategies

Pharmacophore model development relies on two primary sources of information: known active ligands or the structure of the biological target. Each approach has its strengths and is chosen based on data availability.

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling addresses the absence of a known receptor structure by building models from a collection of ligands known to be active against the target of interest [21]. This approach is based on the principle that structurally diverse small molecules exhibiting the same biological activity likely share a common mode of interaction, which can be captured as a pharmacophore. The process involves conformational analysis of the active compounds to generate multiple 3D conformers and identify the likely bioactive conformation, followed by molecular alignment techniques to superimpose the active compounds and identify the shared pharmacophoric features [13]. This method is particularly powerful for targets with no experimentally determined 3D structure, such as many G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) common in oncology signaling pathways.

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling utilizes the 3D structure of the target protein, typically obtained from X-ray crystallography, NMR, or cryo-EM, or through homology modeling [13]. This method involves a direct analysis of the binding site to identify key interaction points—such as hydrogen bonding partners, hydrophobic patches, and charged regions—to generate complementary pharmacophoric features [21]. This approach considers the shape and chemical properties of the binding site to define the pharmacophore model, providing a direct physical basis for the hypothesized interactions. It is especially valuable in oncology drug discovery for targeting well-characterized enzymes and receptors with known crystal structures.

Combined Ligand and Structure-Based Methods integrate information from both active ligands and the target protein structure to generate a more comprehensive and reliable pharmacophore model [13]. In this integrated workflow, a ligand-based pharmacophore is mapped onto the protein binding site to refine and validate the pharmacophoric features. This synergy can incorporate additional information such as protein flexibility and induced-fit effects, leading to more accurate and biologically relevant models.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

The creation of a robust, predictive pharmacophore model is a multi-step, iterative process. The workflow below illustrates the general pathway for pharmacophore model development.

Figure 1: Pharmacophore Model Development Workflow

Data Set Curation and Conformational Analysis. The process begins with assembling a set of known active compounds, ideally with a range of potencies and diverse chemical scaffolds. For each compound, conformational analysis is performed to explore their conformational space. Techniques such as systematic search, Monte Carlo sampling, and molecular dynamics simulations are used to generate a representative set of low-energy conformers, ensuring the model can account for ligand flexibility and identify the biologically relevant conformation [13].

Molecular Alignment and Feature Identification. The core of model building involves superimposing the active compounds to identify common chemical features and their spatial arrangement. Common feature alignment identifies shared pharmacophoric features among the active compounds and aligns them based on these features, while flexible alignment allows for conformational flexibility during the alignment process to better capture the bioactive conformation [13]. Chemical feature recognition algorithms then detect hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions, aromatic rings, and charged groups. Statistical analysis and feature selection methods are employed to identify the most discriminating features for biological activity.

Model Building, Refinement, and Validation. The pharmacophore model is constructed by combining the selected pharmacophoric features and defining their spatial constraints, including interfeature distances, angles, and tolerances [13]. Model refinement involves adjusting these parameters to optimize the model's ability to discriminate between active and inactive compounds. Validation is a critical final step to assess the model's quality, robustness, and predictive power. This involves internal validation (e.g., leave-one-out cross-validation) using the training set and external validation with an independent test set of compounds not used in model development [13]. Statistical metrics like the Enrichment Factor (EF) and the area under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUC-ROC) are calculated. A model is generally considered reliable if it has an AUC greater than 0.7 and an EF value exceeding 2 [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Implementing pharmacophore modeling requires a suite of specialized software tools and computational resources. The table below details key resources used in the field.

Table 3: Essential Tools and Resources for Pharmacophore Modeling

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application in Workflow |

|---|---|---|---|

| MOE (Molecular Operating Environment) | Commercial Software | Comprehensive computational chemistry suite with structure- and ligand-based pharmacophore generation modules [22]. | Model development, virtual screening, and analysis. |

| Discovery Studio | Commercial Software | Provides a full environment for pharmacophore modeling, including the "Receptor-Ligand Pharmacophore Generation" protocol [7]. | Model building, validation, and screening. |

| LigandScout | Commercial Software | Advanced platform for creating 3D pharmacophore models from protein-ligand complexes and for ligand-based design [13]. | Structure-based pharmacophore modeling and screening. |

| RDKit | Open-Chemoinformatics | Provides open-source functionalities for pharmacophore feature identification and topological pharmacophore fingerprint calculation [23] [24]. | Feature identification and descriptor calculation. |

| ZINC Database | Public Compound Library | A curated collection of commercially available compounds for virtual screening [8]. | Source of compounds for pharmacophore-based screening. |

| ChEMBL Database | Public Bioactivity Database | A manually curated database of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties, providing bioactivity data for model training and validation [24]. | Data set curation and model validation. |

| UM-C162 | UM-C162, MF:C30H25N3O4, MW:491.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| BTZ-N3 | BTZ-N3, MF:C17H16F3N5O3S, MW:427.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Advanced Applications and Innovations in Oncology Research

Integrating AI and Machine Learning with Pharmacophore Modeling

The field of pharmacophore modeling is being transformed by the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML). These technologies are enhancing the power and applicability of pharmacophores in drug discovery, particularly for complex oncology targets.

Machine Learning for Feature Prioritization. ML frameworks are now used to analyze pharmacophore features derived from protein-binding sites to identify key features associated with ligand-specific protein conformations [22]. By leveraging molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to generate an ensemble of protein conformations, an AI/ML framework can prioritize pharmacophore features uniquely associated with conformations selected by ligands. This enables a more mechanism-driven understanding of binding interactions, integrating biophysical insights with machine learning by focusing on pharmacophoric properties such as charge, hydrogen bonding, hydrophobicity, and aromaticity [22]. This approach has shown significant improvements, with one study reporting up to a 54-fold enrichment of true positive ligands compared to random selection [22].

Deep Learning for Molecular Generation. Deep generative models represent a frontier in AI-driven pharmacophore applications. The Pharmacophore-Guided deep learning approach for bioactive Molecule Generation (PGMG) uses pharmacophore hypotheses as input to generate novel molecules that match the given pharmacophore [23]. PGMG employs a graph neural network to encode spatially distributed chemical features and a transformer decoder to generate molecules. A key innovation is the introduction of a latent variable to solve the many-to-many mapping problem between pharmacophores and molecules, thereby improving the diversity of generated compounds [23]. This approach is particularly valuable for novel target families or understudied targets in oncology where known active molecules may be scarce.

Knowledge-Guided Diffusion Models. The state-of-the-art continues to advance with frameworks like DiffPhore, a knowledge-guided diffusion model for 3D ligand-pharmacophore mapping [8]. DiffPhore leverages ligand-pharmacophore matching knowledge to guide ligand conformation generation and uses calibrated sampling to mitigate exposure bias in the iterative conformation search process. Trained on large datasets of 3D ligand-pharmacophore pairs, this method has demonstrated superior performance in predicting ligand binding conformations compared to traditional pharmacophore tools and several advanced docking methods, showing great promise for virtual screening in lead discovery and target fishing for oncology applications [8].

Case Study: Identification of Dual VEGFR-2/c-Met Inhibitors for Oncology

A practical application of pharmacophore modeling in oncology is illustrated by a study aiming to identify dual inhibitors of VEGFR-2 and c-Met, two critical targets in cancer pathogenesis and progression that synergistically contribute to angiogenesis and tumor progression [7]. The computational workflow integrated multiple techniques, with pharmacophore modeling serving as a key initial filter.

Methodology and Workflow:

- Pharmacophore Generation: Multiple pharmacophore models were built for both VEGFR-2 and c-Met using the "Receptor Ligand Pharmacophore Generation" module in Discovery Studio, based on crystal structures of protein-ligand complexes [7].

- Model Validation: The models were validated using decoy sets containing known active and inactive compounds. The top models for each target were selected based on high Enrichment Factor (EF) and AUC values [7].

- Virtual Screening: A database of over 1.28 million compounds was first filtered by drug-likeness rules (Lipinski, Veber) and ADMET properties. The resulting library was then screened against the selected VEGFR-2 and c-Met pharmacophores [7].

- Molecular Docking and Dynamics: The top hits from pharmacophore screening were subjected to molecular docking against the target structures. The most promising compounds, compound17924 and compound4312, were further evaluated using molecular dynamics (MD) simulations and MM/PBSA calculations to assess binding stability and calculate binding free energies [7].

Results and Significance: The study successfully identified hit compounds with potential dual inhibitory activity. The MD simulations confirmed that the identified compounds had superior binding free energies compared to positive controls [7]. This case demonstrates the power of pharmacophore modeling as an efficient initial filter to rapidly narrow down large chemical libraries to a manageable number of promising candidates for more computationally intensive methods like docking and MD simulations. This integrated approach is vital in oncology for discovering novel, multi-targeted therapeutic strategies that can overcome tumor resistance mechanisms.

The precise understanding of core pharmacophore terminology—distinguishing between features, binding sites, and their respective roles in molecular recognition—is not merely an academic exercise but a practical necessity in modern drug discovery. As the case studies and methodologies outlined in this guide demonstrate, pharmacophore modeling serves as a versatile and powerful framework for rational drug design, particularly in the complex landscape of oncology research. The integration of these classical concepts with cutting-edge AI and machine learning techniques, such as those seen in PGMG and DiffPhore, is pushing the boundaries of what is possible [23] [8]. These innovations are making the process more predictive, efficient, and interpretable, ultimately accelerating the journey from a theoretical hypothesis to a tangible therapeutic candidate. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering these core concepts and their contemporary applications is essential for leveraging the full potential of computational methods to develop the next generation of oncology therapeutics.

From Theory to Therapy: Building and Applying Oncology Pharmacophore Models

Structure-based pharmacophore modeling represents a pivotal methodology in modern computer-aided drug discovery, particularly for oncology targets where understanding ligand-receptor interactions is crucial. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to generating and applying pharmacophore models derived from three-dimensional protein structures available in the Protein Data Bank (PDB). By abstracting key steric and electronic features necessary for optimal supramolecular interactions with specific biological targets, researchers can efficiently identify novel therapeutic candidates. This guide details comprehensive methodologies for model construction, validation, and implementation in virtual screening campaigns, with specific emphasis on applications in oncology drug development. The integration of these approaches reduces the time and costs associated with conventional drug discovery while providing critical insights for targeting protein classes frequently implicated in cancer pathways.

Fundamental Concepts

The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) defines a pharmacophore as "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or to block) its biological response" [4]. This abstract representation focuses on chemical functionalities rather than specific molecular scaffolds, enabling the identification of structurally diverse compounds that share common biological activity toward a particular target. In oncology research, this capability for "scaffold hopping" is particularly valuable for discovering novel chemotypes that can modulate cancer-relevant pathways while overcoming patent constraints or optimizing drug-like properties.

The core pharmacophore features include [4]:

- Hydrogen bond acceptors (HBA)

- Hydrogen bond donors (HBD)

- Hydrophobic areas (H)

- Positively and negatively ionizable groups (PI/NI)

- Aromatic groups (AR)

- Metal coordinating areas

Additional spatial constraints in the form of exclusion volumes (XVOL) can be incorporated to represent the shape and steric restrictions of the binding pocket, crucially improving model selectivity [4].

Structure-Based vs. Ligand-Based Approaches

Structure-based pharmacophore modeling distinguishes itself from ligand-based approaches by utilizing the three-dimensional structural information of the target protein, typically obtained from X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, or high-quality homology models [4]. This approach is particularly advantageous for oncology targets where: (1) few active ligands are known, (2) the binding site contains distinctive structural features, or (3) researchers aim to target specific protein conformations (e.g., allosteric sites). The method extracts essential interaction points from the protein's binding site or protein-ligand complexes, directly mapping the chemical features required for molecular recognition [4].

Methodological Workflow

The generation of a structure-based pharmacophore model follows a systematic workflow that ensures the resulting hypothesis accurately represents the essential interactions between a ligand and its biological target.

Protein Structure Preparation

The initial step involves obtaining and critically evaluating a high-quality three-dimensional structure of the target protein. The RCSB Protein Data Bank (www.rcsb.org) serves as the primary repository for experimentally determined structures [4]. Key considerations during preparation include:

- Structure Evaluation: Assess resolution, completeness, and steric clashes, particularly for structures determined by X-ray crystallography [4]

- Protonation States: Assign appropriate protonation states to residues, especially histidines, acidic, and basic amino acids, under physiological conditions [4]

- Hydrogen Atom Addition: Add hydrogen atoms that are typically absent in X-ray structures and optimize their positions [4]

- Missing Residues/Atoms: Address gaps in the structure through modeling or refinement when necessary [4]

- Cofactors and Water Molecules: Decide on the inclusion or exclusion of non-protein elements based on their functional significance [4]

For targets lacking experimental structures, computational techniques such as homology modeling or machine learning-based methods like AlphaFold2 can generate reliable 3D models [4].

Binding Site Identification and Analysis

Accurate characterization of the ligand-binding site is fundamental to generating a relevant pharmacophore model. While the binding site may be manually inferred from residues with known functional roles or from co-crystallized ligands, computational tools can systematically detect potential binding pockets:

- GRID: A grid-based method that uses chemical probes to sample protein surfaces and identify energetically favorable interaction points [4]

- LUDI: Employs knowledge-based distributions of non-bonded contacts from experimental structures or geometric rules to predict interaction sites [4]

These tools analyze the protein surface based on evolutionary, geometric, energetic, and statistical properties to locate regions with high binding potential [4].

Pharmacophore Feature Generation and Selection

When a protein-ligand complex structure is available, the ligand in its bioactive conformation directly guides the spatial arrangement of pharmacophore features corresponding to its functional groups engaged in target interactions [4]. In the absence of a bound ligand, the protein structure alone is analyzed to detect all potential ligand interaction points within the binding site, though this typically generates more features that require manual refinement [4].

Table 1: Core Pharmacophore Features and Their Chemical Significance

| Feature Type | Symbol | Chemical Groups Represented | Role in Molecular Recognition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Bond Acceptor | A | Carbonyl, ether, sulfoxide, tertiary amine | Forms hydrogen bonds with donor groups |

| Hydrogen Bond Donor | D | Hydroxyl, amine, amide, guanidine | Forms hydrogen bonds with acceptor groups |

| Hydrophobic | H | Alkyl, aryl, alicyclic groups | Participates in van der Waals interactions |

| Positively Ionizable | P | Primary, secondary, tertiary amines | Forms salt bridges with acidic groups |

| Negatively Ionizable | N | Carboxylic acid, tetrazole, phosphonate | Forms salt bridges with basic groups |

| Aromatic | R | Phenyl, furan, thiophene, pyrrole | Engages in π-π and cation-π interactions |

| Exclusion Volume | XV | - | Represents sterically forbidden regions |

Feature selection prioritizes interactions that are energetically significant to binding affinity and biologically relevant to function. This can be achieved by [4]:

- Removing features that do not strongly contribute to binding energy

- Identifying conserved interactions across multiple protein-ligand complexes

- Preserving residues with key functions from sequence alignments or mutational analysis

- Incorporating spatial constraints from receptor information

Model Validation

Validation is essential to verify the pharmacophore model's ability to distinguish active from inactive compounds [25] [6]. The most robust method employs Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve analysis, which plots the true positive rate against the false positive rate [25]. The Area Under the Curve (AUC) quantifies the model's discriminative power, with values approaching 1.0 indicating excellent performance [25]. The early enrichment factor (EF1%) is another valuable metric, representing the ratio of true positives identified in the top 1% of screened compounds compared to a random selection [6].

Experimental Protocols

Structure-Based Model Generation from Protein-Ligand Complex

This protocol outlines the steps for generating a pharmacophore model when a protein-ligand complex structure is available, typically providing the highest quality hypotheses [4] [6].

Materials and Software Requirements:

- Protein-ligand complex structure (PDB format)

- Molecular modeling software with pharmacophore generation capabilities (e.g., LigandScout, Schrödinger Phase, Discovery Studio)

- High-performance computing workstation

Procedure:

- Import the PDB file of the protein-ligand complex into the molecular modeling software

- Prepare the protein structure by adding hydrogen atoms, assigning appropriate protonation states, and optimizing hydrogen bonding networks

- Analyze protein-ligand interactions to identify key molecular recognition elements, including:

- Hydrogen bonding interactions (donors and acceptors)

- Hydrophobic contact surfaces

- Charge-assisted interactions (ionic, salt bridges)

- Aromatic stacking interactions (Ï€-Ï€, cation-Ï€)

- Metal coordination interactions

- Convert specific interactions into corresponding pharmacophore features with appropriate geometries:

- Hydrogen bond donors and acceptors (vector features)

- Hydrophobic regions (sphere features)

- Charged groups (point features with directionality)

- Aromatic rings (plane and center features)

- Add exclusion volumes to represent the steric boundaries of the binding pocket

- Refine the initial hypothesis by removing redundant features and prioritizing those with highest energetic contributions to binding