Pharmacophore Modeling in Modern Drug Discovery: A Comprehensive Guide to Methods, Applications, and AI-Driven Advances

This article provides a comprehensive examination of pharmacophore modeling's pivotal role in computer-aided drug design, addressing the needs of researchers and drug development professionals.

Pharmacophore Modeling in Modern Drug Discovery: A Comprehensive Guide to Methods, Applications, and AI-Driven Advances

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of pharmacophore modeling's pivotal role in computer-aided drug design, addressing the needs of researchers and drug development professionals. It explores foundational concepts and historical development, details structure-based and ligand-based methodological approaches, and examines successful applications in virtual screening and lead optimization. The content analyzes current limitations and refinement strategies, presents validation metrics and comparative performance data against other virtual screening methods, and discusses the integration of artificial intelligence to enhance predictive accuracy and efficiency in modern drug discovery pipelines.

The Pharmacophore Concept: From Historical Origins to Modern Definition in Drug Discovery

Historical Evolution: From Paul Ehrlich's Original Concept to IUPAC Definition

The pharmacophore concept, a cornerstone of modern computer-aided drug design, has undergone a profound evolution from its initial conceptualization to its current formal definition. This whitepaper traces this critical journey, beginning with Paul Ehrlich's pioneering "magic bullet" hypothesis at the dawn of the 20th century, which introduced the paradigm of targeted therapy. The concept was later formally defined by the IUPAC as "an ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target" [1]. This document delineates the key historical milestones, conceptual shifts, and methodological advances that have positioned pharmacophore modeling as an indispensable tool in rational drug discovery. Framed within a broader thesis on its role in computer-aided drug design, this review underscores how the pharmacophore has transitioned from an abstract idea into a quantitative, computable model that drives virtual screening, de novo design, and lead optimization.

In the contemporary landscape of pharmaceutical research, the pharmacophore is a fundamental conceptual and computational model. It serves as a critical bridge connecting chemical structure to biological activity, enabling the rational identification and optimization of novel therapeutic agents. According to the IUPAC, a pharmacophore is "an ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target and to trigger (or block) its biological response" [1] [2]. It is not a specific molecule or functional group, but rather an abstract pattern of features that represents the essential molecular interaction capacities of a group of bioactive compounds [3].

The utility of pharmacophore models in computer-aided drug discovery is extensive. They are employed in:

- Virtual Screening: Filtering large chemical databases to identify novel compounds that match the essential feature map of a pharmacophore model [4].

- De Novo Design: Guiding the construction of novel chemical entities that conform to the pharmacophore requirements [4].

- Lead Optimization: Providing insights into Structure-Activity Relationships (SAR) by highlighting features critical for biological activity [5].

- Multi-Target Drug Design: Facilitating the design of ligands that interact with multiple biological targets by combining relevant pharmacophore features [4].

- ADMET Modeling: Applying the concept to model absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) properties [5].

This document explores the historical trajectory that has established the pharmacophore as such a versatile and powerful tool, detailing its origins, key evolutionary shifts, and the experimental protocols that underpin its modern application.

The Original Concept: Paul Ehrlich's 'Magic Bullet'

The intellectual foundation of the pharmacophore concept was laid by the German Nobel laureate Paul Ehrlich (1854–1915) in the early 1900s. While working at the Institute of Experimental Therapy, Ehrlich introduced the idea of a "magic bullet" (Zauberkugel)—a substance that could selectively target and eliminate disease-causing microbes without harming the host organism [6] [7]. The name was inspired by a German myth about a bullet that could not miss its target, reflecting Ehrlich's vision of a therapeutic agent with exquisite specificity [6].

Ehrlich's hypothesis was grounded in his earlier research with * Emil Behring* on diphtheria antitoxin (antibodies) and his own extensive work with synthetic dyes [6] [7]. He observed that certain dyes would selectively stain specific tissues and microbes, leading him to postulate that chemical compounds could be engineered to similarly seek out and bind to pathological targets [7]. He articulated this concept in his side-chain theory (later receptor theory), proposing that chemical interactions between a drug and a cellular receptor were highly specific, like a "key and lock" [6]. His famous postulate was: "wir müssen chemisch zielen lernen" ("we have to learn how to aim chemically") [6].

The first tangible realization of this concept was the development of Salvarsan (arsphenamine, Compound 606) in 1909, in collaboration with Sahachiro Hata [6] [7]. Salvarsan, an arsenic-based compound, became the first effective pharmacological treatment for syphilis and is recognized as the first magic bullet [6]. It demonstrated that a synthetic chemical could be selectively toxic to a pathogen (Treponema pallidum) in a host. Although Ehrlich himself did not use the word "pharmacophore" in his writings—he used terms like "toxophores" for the groups responsible for toxic effects—his work established the core principle that specific chemical features govern biological activity and selective binding [8]. For his immense contributions, including his work on immunity, Ehrlich shared the 1908 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine [6].

Conceptual Evolution and Formalization by IUPAC

The century following Ehrlich's seminal work saw the "pharmacophore" concept mature and become rigorously defined. A significant shift occurred in the meaning of the term, moving from Ehrlich's identification of specific chemical groups to a more abstract description of molecular features [8].

Credit for popularizing the modern term in the 1960s and 70s goes to Lemont B. Kier [1] [3]. However, research indicates that the pivotal redefinition was offered by F. W. Shueler in his 1960 book Chemobiodynamics and Drug Design, where he used the expression "pharmacophoric moiety" in a context aligning with the modern understanding [1] [8]. This evolution culminated in the formal, authoritative definition by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) in 1998, which codified the pharmacophore as an abstract ensemble of essential steric and electronic features [1] [2].

Table: Historical Evolution of the Pharmacophore Concept

| Time Period | Key Figure(s) | Conceptual Contribution | Terminology Used |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early 1900s | Paul Ehrlich | Introduced the concept of selective targeting via specific chemical groups. | "Magic Bullet" (Zauberkugel), "Toxophores" [6] [8] |

| 1960 | F. W. Shueler | Redefined the concept to focus on abstract features essential for activity. | "Pharmacophoric moiety" [1] [8] |

| 1967-1971 | Lemont B. Kier | Popularized the term "pharmacophore" in its modern sense through publications and applications [1]. | "Pharmacophore" |

| 1998 | IUPAC | Provided the formal, standardized definition widely accepted today. | "Ensemble of steric and electronic features" [1] |

This conceptual evolution is summarized in the following diagram, which maps the key transitions in the definition and application of the pharmacophore.

Core Methodologies: Building a Pharmacophore Model

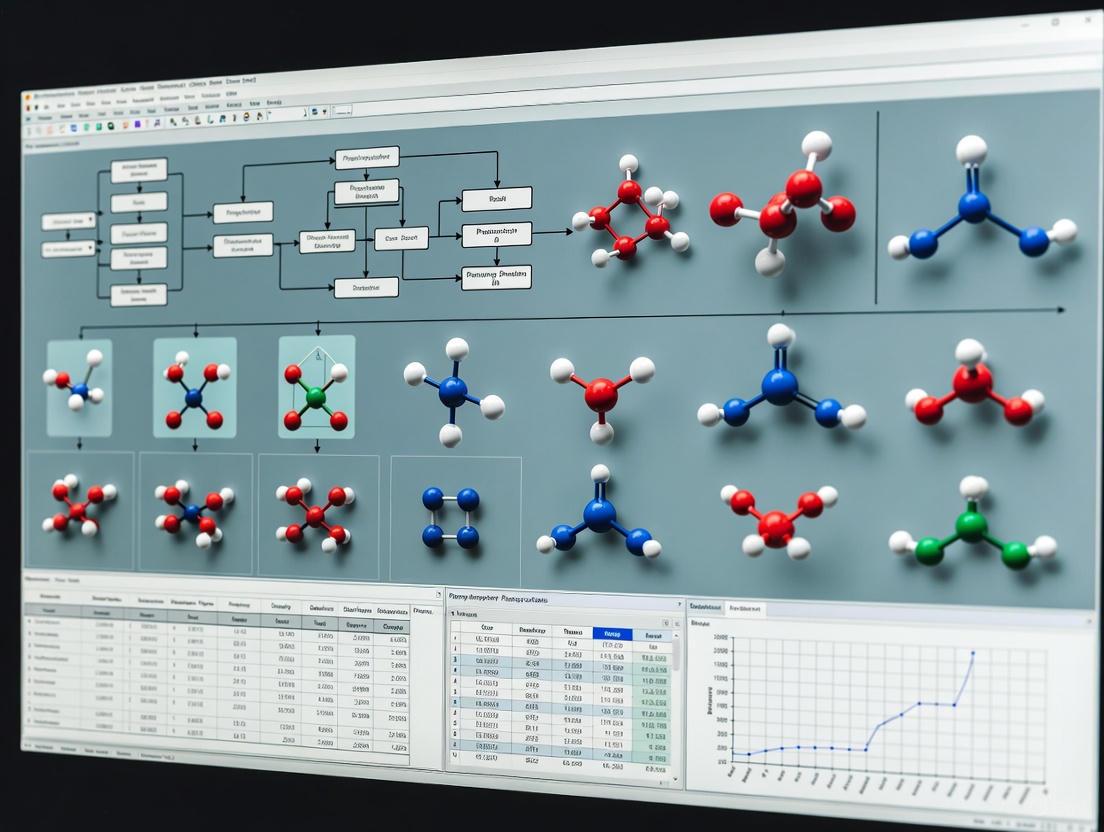

The creation of a pharmacophore model is a systematic computational process. The two primary approaches are ligand-based and structure-based pharmacophore modeling, both of which follow a coherent workflow [4] [2].

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

This approach is used when the 3D structure of the biological target is unknown but a set of active ligands is available. The protocol involves several key steps [4] [2]:

- Training Set Selection: A structurally diverse set of molecules known to be active against the target is selected. Including inactive compounds can help define features that are detrimental to activity.

- Conformational Analysis: For each molecule in the training set, a set of low-energy conformations is generated. The goal is to ensure that the conformational space is adequately sampled to include the putative bioactive conformation.

- Molecular Superimposition: Multiple low-energy conformations of the active molecules are superimposed. The objective is to find the best spatial overlap of common chemical features presumed to be critical for binding.

- Abstraction and Model Generation: The common chemical features from the superimposed molecules (e.g., hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions, charged groups) are extracted and abstracted into a pharmacophore model. This model consists of the spatial arrangement of these abstract features.

- Model Validation: The model is tested for its ability to predict the activity of a set of known active and inactive compounds not used in the training set. This validates its predictive power and refines its quality.

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

This method is employed when a 3D structure of the target (e.g., from X-ray crystallography or NMR) is available, often in complex with a ligand [4].

- Structure Preparation: The protein structure is prepared by adding hydrogen atoms, assigning correct bond orders, and optimizing the structure.

- Interaction Analysis: The binding site is analyzed for key interactions between the protein and a bound ligand, or by probing the empty binding site for potential interaction points (e.g., hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic patches, ionic contacts).

- Feature Identification: The identified protein-ligand interaction points or the potential interaction sites in the cavity are translated into pharmacophore features.

- Model Assembly: The spatial relationships (distances, angles) between the identified features are used to assemble the pharmacophore model.

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and decision process for selecting and executing these two primary methodologies.

The experimental and computational work in pharmacophore modeling relies on a suite of software tools and conceptual resources. The following table details key components of the modern pharmacophore modeler's toolkit.

Table: Essential Computational Tools and Resources for Pharmacophore Modeling

| Tool/Resource Name | Type/Function | Key Utility in Pharmacophore Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| Catalyst/HipHop [4] [3] | Commercial Software | One of the first automated systems for pharmacophore discovery; performs generation and 3D database searching. |

| DISCO [4] [3] | Computational Algorithm | (DIStance COmparisons) Aids in finding common pharmacophore patterns by comparing feature distances across molecules. |

| GASP [4] [3] | Computational Algorithm | (Genetic Algorithm Similarity Program) Uses molecular field similarity and evolutionary algorithms for pharmacophore discovery. |

| PHASE [4] | Software Module | Provides a comprehensive toolset for pharmacophore perception, 3D-QSAR model development, and 3D database screening. |

| RDKit [2] | Open-Source Cheminformatics Toolkit | Provides a wide array of cheminformatics functions, including the ability to generate pharmacophore features and handle molecular conformations. |

| LigandScout [2] | Software Application | Enables the creation of structure- and ligand-based pharmacophore models and advanced 3D pharmacophore screening. |

| Conformational Ensemble [4] | Computational Data | A set of low-energy 3D structures for a molecule, crucial for representing its flexible nature in ligand-based modeling. |

| Feature Definitions [1] [2] | Conceptual Framework | Standardized definitions of chemical features (e.g., Hydrogen Bond Acceptor, Hydrophobic), as per IUPAC guidelines. |

The journey of the pharmacophore from Paul Ehrlich's visionary "magic bullet" to the IUPAC's precise definition encapsulates a century of scientific progress in understanding molecular recognition. This evolution—from a focus on concrete chemical groups to an abstract ensemble of electronic and steric features—has been fundamental to the rise of rational drug design. Today, pharmacophore models are indispensable in the computational chemist's arsenal, providing a powerful abstract representation that drives virtual screening, de novo design, and lead optimization. As computational power increases and methodologies like machine learning become more integrated, the pharmacophore concept, rooted in Ehrlich's original insight, will continue to be refined and expanded. It remains a central paradigm in the ongoing effort to reduce the cost and time of drug discovery by providing a rational, structure-based framework for designing the next generation of therapeutics.

In the field of computer-aided drug discovery (CADD), the pharmacophore concept serves as a fundamental cornerstone for rational drug design. According to the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC), a pharmacophore is defined as "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or to block) its biological response" [9] [10] [11]. This conceptual framework provides an abstract representation of molecular interactions, focusing not on specific chemical structures but on the essential functional features required for biological activity. The historical development of this concept dates back to Paul Ehrlich in 1909, who first introduced the idea that molecular frameworks carry essential features responsible for biological activity [10] [11]. Over the past century, pharmacophore modeling has evolved into one of the most successful and widely applied tools in medicinal chemistry, enabling researchers to navigate complex chemical spaces and identify novel therapeutic candidates with greater efficiency and reduced costs [9] [10].

Fundamental Steric and Electronic Features of Pharmacophores

Core Feature Definitions and Spatial Characteristics

Pharmacophore models represent key chemical functionalities as geometric entities—typically spheres with defined radii, along with planes and vectors—that capture the spatial arrangement of molecular interactions. The radius of each sphere represents the tolerance for deviation from an ideal position, accommodating natural flexibility in ligand-receptor interactions [11]. The most critical pharmacophore features include well-defined steric and electronic properties that facilitate specific supramolecular interactions with biological targets.

Table 1: Fundamental Pharmacophore Features and Their Characteristics

| Feature Type | Electronic/Steric Character | Molecular Recognition Role | Representative Chemical Groups |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Bond Acceptor (HBA) | Electronic | Accepts hydrogen bonds from donors | Carbonyl oxygen, ether oxygen, nitrogen in aromatic rings |

| Hydrogen Bond Donor (HBD) | Electronic | Donates hydrogen bonds to acceptors | Amine groups, hydroxyl groups, amide NH |

| Positively Ionizable (PI) | Electronic | Forms electrostatic interactions with anions | Primary, secondary, tertiary amines; guanidine groups |

| Negatively Ionizable (NI) | Electronic | Forms electrostatic interactions with cations | Carboxylic acids, phosphates, sulfonates, tetrazoles |

| Hydrophobic (H) | Steric | Engages in van der Waals interactions with hydrophobic pockets | Alkyl chains, aromatic rings, alicyclic systems |

| Aromatic (AR) | Both electronic and steric | Participates in π-π stacking and cation-π interactions | Phenyl, pyridine, other aromatic ring systems |

| Metal Coordinating | Electronic | Chelates metal ions in active sites | Histidine imidazole, carboxylates, thiols |

These features represent the key elements that facilitate binding between a ligand and its biological target through various interaction types including hydrogen bonding, electrostatic attractions, hydrophobic effects, and aromatic interactions [9] [11]. The spatial arrangement of these features within a pharmacophore model defines the molecular recognition pattern necessary for biological activity, independent of the underlying chemical scaffold [9]. This abstraction enables pharmacophore approaches to identify structurally diverse compounds that share common biological activity—a process known as scaffold hopping [10].

Advanced Feature Considerations: Exclusion Volumes and Directional Vectors

Beyond the primary features described above, sophisticated pharmacophore models incorporate additional elements that enhance their biological relevance and predictive accuracy. Exclusion volumes (XVOL) represent forbidden areas that correspond to steric clashes between the ligand and receptor, effectively mapping the shape and boundaries of the binding pocket [9] [12]. These exclusion spheres ensure that generated or identified ligands not only possess the necessary interacting groups but also fit within the spatial constraints of the binding site.

For features where interaction geometry is critical, such as hydrogen bonding, directional vectors may be incorporated to represent the optimal trajectory for these interactions [11]. Similarly, aromatic rings may be represented with vector normal to their plane to capture the geometry of π-π stacking interactions [11]. These advanced features increase the precision of pharmacophore models, improving their ability to distinguish true actives from inactive compounds in virtual screening applications.

Methodological Approaches to Pharmacophore Modeling

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

Structure-based pharmacophore modeling relies on the three-dimensional structural information of macromolecular targets, typically obtained from X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, or cryo-electron microscopy [9] [13]. When experimental structures are unavailable, computational techniques such as homology modeling or machine learning-based methods like AlphaFold2 can generate reliable 3D models [9]. The workflow for structure-based pharmacophore modeling follows a systematic protocol:

Step 1: Protein Structure Preparation The quality of the input structure directly influences the resulting pharmacophore model. This critical first step involves evaluating and optimizing:

- Protonation states of residues under physiological conditions

- Position of hydrogen atoms (absent in X-ray structures)

- Presence and functional role of non-protein groups (cofactors, water molecules)

- Completeness of the structure (addressing missing residues or atoms)

- Stereochemical parameters and overall energetic feasibility [9]

Step 2: Ligand-Binding Site Characterization Identification of the binding site is achieved through:

- Analysis of protein-ligand co-crystal structures if available

- Computational detection of potential binding pockets using tools like GRID or LUDI

- GRID uses molecular interaction fields with different probe types to identify energetically favorable interaction sites

- LUDI applies geometric rules and statistical distributions from known protein-ligand complexes [9]

Step 3: Pharmacophore Feature Generation and Selection Interaction points between the binding site and potential ligands are mapped:

- Features are generated based on complementarity with binding site residues

- When a protein-ligand complex is available, features are derived directly from observed interactions

- In apo structures, all possible interaction points are calculated, often requiring manual refinement

- Initial feature sets are refined by removing non-essential features to create selective hypotheses [9] [13]

Table 2: Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling Software and Applications

| Software/Tool | Methodological Basis | Key Application | Representative Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| GRID | Molecular interaction fields using chemical probes | Binding site characterization and interaction energy mapping | Identification of hydrophobic regions and hydrogen bonding sites [9] |

| LUDI | Geometric rules and statistical contact distributions | Fragment-based de novo design and binding site analysis | Prediction of potential interaction sites in novel targets [9] |

| LigandScout | Structure-based feature detection from protein-ligand complexes | Automated pharmacophore model generation | Creation of validated pharmacophore models for XIAP protein [13] |

| Structure-Based Pharmacophore (SBPM) | Interaction points from holo or apo protein structures | Virtual screening and lead optimization | Identification of natural anti-cancer agents targeting XIAP [13] |

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

When the 3D structure of the target macromolecule is unavailable, ligand-based pharmacophore modeling provides a powerful alternative approach. This method extracts common chemical features from a set of known active ligands that represent the essential interactions with the biological target [9] [10]. The methodology involves:

Step 1: Training Set Compilation

- Selection of structurally diverse compounds with confirmed biological activity

- Inclusion of inactive compounds when available to improve model selectivity

- Ensuring appropriate representation of different chemical scaffolds while maintaining common pharmacological activity [10]

Step 2: Conformational Analysis and Molecular Alignment

- Generation of biologically relevant conformations for each compound

- Alignment of molecules to maximize overlap of common chemical features

- Application of algorithms such as maximum common substructure (MCS) or field-based alignment techniques [10]

Step 3: Common Feature Pharmacophore Generation

- Identification of conserved steric and electronic features across the aligned molecule set

- Definition of spatial tolerances for each feature based on molecular variability

- Optimization of feature combinations to balance model selectivity and generality [9] [10]

Ligand-based approaches are particularly valuable for targets with limited structural information, such as many G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) [14]. The quality of ligand-based models depends heavily on the diversity and quality of the training set compounds, with greater structural diversity typically leading to more robust and generally applicable models.

Experimental Implementation and Validation Protocols

Pharmacophore Model Validation Methods

To ensure the reliability and predictive power of pharmacophore models, rigorous validation protocols must be implemented. The validation process typically involves:

Decoy Set Validation This method evaluates the model's ability to distinguish known active compounds from decoy molecules that are similar in physicochemical properties but presumed inactive [13]. The protocol includes:

- Compilation of known active compounds with experimental activity data (IC50, Ki values)

- Generation of decoy sets using tools like the Database of Useful Decoys (DUDe)

- Calculation of enrichment factors (EF) and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves

- Assessment of the area under the ROC curve (AUC) with values closer to 1.0 indicating superior performance [13]

In a recent study on XIAP inhibitors, structure-based pharmacophore validation achieved an exceptional early enrichment factor (EF1%) of 10.0 with an AUC value of 0.98, demonstrating excellent discriminatory power [13].

Experimental Correlation The ultimate validation of any pharmacophore model comes from experimental confirmation:

- Selected virtual hits are subjected to biological testing

- Dose-response relationships establish potency of identified compounds

- Specificity testing confirms target engagement

- Structural analysis (X-ray crystallography, NMR) verifies predicted binding modes [13] [15]

Practical Application: Virtual Screening Protocol

Once validated, pharmacophore models serve as queries for virtual screening of compound databases. A standard protocol includes:

Step 1: Database Preparation

- Selection of appropriate compound libraries (ZINC, Enamine, in-house collections)

- Generation of biologically relevant 3D conformations for each compound

- Consideration of tautomeric states and protonation at physiological pH [13] [16]

Step 2: Pharmacophore-Based Screening

- Flexible fitting of database compounds to the pharmacophore model

- Scoring based on the quality of feature matching and spatial overlap

- Application of exclusion volume constraints to eliminate sterically hindered compounds [9] [11]

Step 3: Post-Screening Analysis

- Visual inspection of top-ranking hits to verify reasonable chemical structures

- Assessment of chemical diversity among selected compounds

- Evaluation of drug-like properties using filters such as Lipinski's Rule of Five [13] [15]

In a case study targeting breast cancer, researchers employed pharmacophore-based virtual screening followed by molecular dynamics simulations, which led to the identification of a novel compound (Molecule 10) with potent antitumor activity (IC50 = 0.032 µM) against MCF-7 cells [15].

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Pharmacophore Modeling

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Primary Function | Accessibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Structure Resources | RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB), AlphaFold2 Database, SWISS-MODEL | Source of 3D structural data for targets and homologs | Public access with registration for some features |

| Compound Databases | ZINC, Enamine, CHEMBL, PubChem | Libraries for virtual screening and training set compilation | Publicly accessible with varying download options |

| Pharmacophore Modeling Software | LigandScout, MOE, Discovery Studio, PHASE | Creation, visualization, and application of pharmacophore models | Commercial with academic licensing options |

| Computational Chemistry Suites | Schrödinger Suite, OpenEye, AutoDock Vina | Molecular docking, dynamics, and structure preparation | Commercial and open-source options available |

| Force Fields | CHARMM, AMBER, GAFF | Energy calculations and molecular dynamics simulations | Openly available with parameter generation tools |

| MD Simulation Packages | GROMACS, NAMD, AMBER | Assessment of binding stability and conformational sampling | Open source with community support |

Emerging Innovations and Future Perspectives

The field of pharmacophore modeling continues to evolve with emerging technologies that enhance its capabilities and applications. Artificial intelligence and machine learning are being integrated with pharmacophore approaches to create more predictive models. The recently developed Pharmacophore-Guided deep learning approach for bioactive Molecule Generation (PGMG) uses graph neural networks to encode spatially distributed chemical features and transformers to generate novel molecular structures that match specific pharmacophores [17]. This integration addresses the challenge of data scarcity in drug discovery, particularly for novel target families.

Dynamic pharmacophore modeling represents another significant advancement, where molecular dynamics simulations are used to capture the flexibility of both ligands and targets [14]. By accounting for protein flexibility and the multiple conformational states accessible to both receptors and ligands, these dynamic models provide a more realistic representation of molecular recognition events, potentially leading to improved virtual screening performance.

The application of pharmacophore approaches has also expanded beyond conventional drug targets to address challenging therapeutic areas. Recent studies have demonstrated their utility in targeting protein-protein interactions [11], designing selective allosteric modulators [14], and predicting potential off-target effects and toxicities [12] [11]. As structural biology continues to provide insights into previously intractable targets, and computational methods become increasingly sophisticated, pharmacophore modeling remains a versatile and indispensable tool in the modern drug discovery arsenal.

Pharmacophore modeling represents a cornerstone of computer-aided drug design (CADD), providing an abstract framework that defines the essential molecular interactions necessary for biological activity. This technical guide examines the three-dimensional arrangement of key pharmacophore features—hydrogen bond donors and acceptors, hydrophobic areas, and ionizable groups—that facilitate supramolecular interactions between ligands and their biological targets. Within modern CADD pipelines, pharmacophore models serve as powerful tools for virtual screening, lead optimization, and de novo drug design by capturing the steric and electronic features responsible for molecular recognition. This whitepaper details the fundamental characteristics of these core features, their roles in molecular interactions, and the methodological approaches for their implementation in structure-based and ligand-based drug discovery. As artificial intelligence and machine learning increasingly transform computational pharmacology, understanding these foundational elements remains critical for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to accelerate therapeutic discovery.

The official International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) definition describes a pharmacophore as "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or to block) its biological response" [18] [9]. This conceptual framework dates back to Paul Ehrlich's late-19th century work on specific molecular groups responsible for biological activity, establishing the fundamental principle that compounds sharing common chemical functionalities with similar spatial arrangements typically exhibit similar biological activities toward the same target [18] [9].

In contemporary computer-aided drug design (CADD), pharmacophore models abstract specific atoms and functional groups into generalized chemical features that mediate ligand-target interactions [18]. This abstraction enables the identification of structurally diverse compounds that interact with the same biological target through equivalent molecular recognition patterns. Pharmacophore approaches have evolved into indispensable tools within CADD pipelines, particularly valuable for virtual screening of large chemical libraries, scaffold hopping to identify novel chemotypes, lead optimization, and multi-target drug design [9].

The foundational principle of pharmacophore modeling rests on identifying the essential, minimum structural features required for target binding and biological activity [19]. By focusing on interaction capacities rather than specific chemical scaffolds, pharmacophore models facilitate the discovery of structurally distinct compounds with similar target profiles, significantly expanding the explorable chemical space in drug discovery programs.

Fundamental Pharmacophore Features

Hydrogen Bond Donors and Acceptors

Hydrogen bond donors (HBD) are functional groups featuring a hydrogen atom bonded to an electronegative atom (typically oxygen or nitrogen) that can participate in directional interactions with electron-rich acceptor atoms [9]. In pharmacophore models, these features represent the capacity to donate a hydrogen bond to complementary acceptor groups on the biological target, such as carbonyl oxygen atoms or negatively charged centers in the binding pocket.

Hydrogen bond acceptors (HBA) constitute regions with electron-rich atoms (commonly oxygen, nitrogen, or sulfur) that can form directional interactions with hydrogen bond donors from the target protein [9] [20]. These features typically include lone pairs of electrons capable of forming stabilizing interactions with hydrogen atoms bonded to electronegative atoms.

The spatial directionality of hydrogen bonding interactions represents a critical parameter in pharmacophore modeling, as the optimal geometry maximizes interaction energy and binding specificity [20]. Modern pharmacophore tools incorporate directional vectors to ensure proper alignment of these features between ligand and target.

Hydrophobic Areas

Hydrophobic features represent molecular regions characterized by non-polar atoms or alkyl chains that preferentially associate with other non-polar surfaces through van der Waals interactions and the hydrophobic effect [9] [20]. These features typically include aliphatic carbon chains, aromatic rings, and other non-polar molecular regions that avoid aqueous environments.

In pharmacophore modeling, hydrophobic features drive ligand binding through the entropic gain resulting from water displacement from hydrophobic binding pockets and the favorable van der Waals contacts between complementary non-polar surfaces [19]. Unlike hydrogen bonding features, hydrophobic interactions are generally less directional but highly dependent on the close complementarity of interacting surfaces.

Ionizable Groups

Positively ionizable groups (PI) represent molecular features that can carry a positive charge under physiological conditions, typically including amine groups that can be protonated [9]. These groups can form strong electrostatic interactions with negatively charged residues in binding pockets, such as carboxylate groups from aspartic or glutamic acid side chains.

Negatively ionizable groups (NI) constitute molecular regions that can carry a negative charge, typically including carboxylic acids, phosphates, sulfonates, or tetrazoles [9]. These features interact favorably with positively charged residues in binding sites, such as ammonium groups from lysine side chains or guanidinium groups from arginine residues.

The strength and longer range of electrostatic interactions involving ionizable groups make them particularly important for initial molecular recognition and binding affinity. The protonation state of these groups at physiological pH significantly influences their interaction capacities and must be carefully considered during pharmacophore model development [19].

Table 1: Fundamental Pharmacophore Features and Their Characteristics

| Feature Type | Atomic Components | Interaction Type | Directionality | Energy Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Bond Donor | O-H, N-H | Electrostatic, dipole | High | -1 to -5 kcal/mol |

| Hydrogen Bond Acceptor | O, N, S | Electrostatic, dipole | High | -1 to -5 kcal/mol |

| Hydrophobic Area | C-H groups, aromatic rings | van der Waals, entropic | Low | -0.1 to -0.2 kcal/mol per atom |

| Positively Ionizable | Amines, guanidines | Electrostatic | Medium | -5 to -10 kcal/mol |

| Negatively Ionizable | Carboxylates, phosphates | Electrostatic | Medium | -5 to -10 kcal/mol |

Methodological Approaches in Pharmacophore Modeling

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

Structure-based pharmacophore modeling derives pharmacophore features directly from the three-dimensional structure of the target protein, typically obtained from X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, or cryo-electron microscopy [9]. When experimental structures are unavailable, computationally predicted structures from tools like AlphaFold or homology models serve as suitable alternatives [21] [22]. The methodology follows a systematic workflow:

Protein Preparation: The initial step involves optimizing the protein structure through hydrogen atom addition, residue protonation appropriate for physiological pH, and correction of any structural anomalies or missing atoms [9]. This ensures the model accurately represents the biological reality.

Binding Site Detection: Identification of the ligand-binding site employs computational tools such as GRID and LUDI, which analyze protein surfaces to locate regions with favorable interaction potentials based on geometric, energetic, and evolutionary constraints [9].

Feature Generation: Analysis of the binding site geometry identifies potential interaction points complementary to ligand features—hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic patches, and regions accommodating ionizable groups [9]. Exclusion volumes (XVOL) are added to represent steric constraints from protein atoms [9].

Feature Selection: The final step refines the model by selecting only the most critical features—those with strong energetic contributions to binding, evolutionary conservation, or demonstrated importance through mutagenesis studies [9].

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling Workflow

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

Ligand-based approaches develop pharmacophore models from a set of known active compounds without requiring target structure information [9]. This method identifies common molecular interaction patterns among diverse ligands that bind the same target:

Conformational Analysis: Generation of energetically favorable 3D conformations for each active ligand, ensuring comprehensive coverage of accessible spatial arrangements [18].

Molecular Alignment: Superposition of ligand structures to identify common spatial arrangements of chemical features despite potential scaffold differences [18].

Common Feature Identification: Detection of conserved pharmacophore elements—hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic areas, and ionizable groups—across the aligned ligand set [9].

Model Validation: Assessment of the resulting pharmacophore hypothesis using both active and inactive compounds to verify its ability to discriminate true actives [19].

The quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) pharmacophore generation represents a sophisticated ligand-based approach that incorporates biological activity data to create models that correlate feature arrangement with potency [19].

Experimental Implementation and Validation

Virtual Screening Protocols

Pharmacophore-based virtual screening applies pharmacophore models as search queries to identify potential hits from large chemical databases [9]. The standard protocol involves:

Database Preparation: Conversion of compound libraries into searchable 3D formats with representative conformational ensembles for each molecule [23].

Pharmacophore Searching: Screening of database compounds against the pharmacophore model using flexible alignment algorithms that evaluate both feature matching and geometric constraints [9].

Hit Selection and Ranking: Identification of molecules satisfying the pharmacophore hypothesis and ranking based on fit quality, chemical novelty, and drug-like properties [23].

Post-Screening Analysis: Further evaluation of top-ranking hits using complementary methods like molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulations, and binding affinity predictions [23].

Comparative studies demonstrate that pharmacophore-based virtual screening (PBVS) frequently outperforms docking-based virtual screening (DBVS) in retrieval rates of active compounds across diverse targets, with superior enrichment factors observed in 14 of 16 benchmark evaluations [23].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Virtual Screening Methods Across Eight Protein Targets

| Target Protein | Pharmacophore-Based VS | Docking-Based VS | Enhancement Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Angiotensin Converting Enzyme (ACE) | 72% hit rate | 58% hit rate | 1.24 |

| Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) | 68% hit rate | 52% hit rate | 1.31 |

| Androgen Receptor (AR) | 75% hit rate | 61% hit rate | 1.23 |

| D-alanyl-D-alanine Carboxypeptidase (DacA) | 70% hit rate | 55% hit rate | 1.27 |

| Dihydrofolate Reductase (DHFR) | 65% hit rate | 50% hit rate | 1.30 |

| Estrogen Receptor α (ERα) | 71% hit rate | 59% hit rate | 1.20 |

| HIV-1 Protease (HIV-pr) | 69% hit rate | 54% hit rate | 1.28 |

| Thymidine Kinase (TK) | 66% hit rate | 51% hit rate | 1.29 |

Advanced AI-Driven Approaches

Recent advancements integrate artificial intelligence with pharmacophore modeling, exemplified by frameworks like DiffPhore—a knowledge-guided diffusion model for 3D ligand-pharmacophore mapping [20]. This approach leverages deep learning to generate ligand conformations that optimally align with pharmacophore constraints while addressing the sparse feature challenge inherent to pharmacophore models [20].

The methodology employs three integrated modules:

- Knowledge-guided LPM Encoder: Incorporates pharmacophore type and direction matching rules to represent alignment between ligand conformations and pharmacophores [20].

- Diffusion-based Conformation Generator: Utilizes score-based diffusion models parameterized by SE(3)-equivariant graph neural networks to explore conformation space informed by pharmacophore constraints [20].

- Calibrated Conformation Sampler: Adjusts conformation perturbation strategies to minimize discrepancies between training and inference phases [20].

This AI-enhanced approach demonstrates superior performance in predicting binding conformations compared to traditional pharmacophore tools and several advanced docking methods, particularly in virtual screening applications for lead discovery and target fishing [20].

Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Pharmacophore Modeling and Analysis

| Tool Category | Specific Software/Resource | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmacophore Modeling Software | Catalyst/Discovery Studio | Build pharmacophore models and perform virtual screening | Ligand- and structure-based model development [18] |

| MOE | Molecular modeling and pharmacophore development | Integrated drug design platform [18] | |

| LigandScout | Generate 3D pharmacophores from protein-ligand complexes | Structure-based pharmacophore modeling [18] [23] | |

| PHASE | 3D pharmacophore modeling and QSAR analysis | Ligand-based pharmacophore modeling [19] [20] | |

| Protein Structure Databases | Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Repository of experimental protein structures | Source of target structures for structure-based design [18] [9] |

| Compound Libraries | ZINC Database | Curated collection of commercially available compounds | Virtual screening for lead identification [20] |

| AI-Driven Platforms | DiffPhore | Knowledge-guided diffusion for ligand-pharmacophore mapping | AI-enhanced pharmacophore modeling and screening [20] |

| Molecular Docking Tools | AutoDock Vina, GOLD, Glide | Predictive ligand positioning in binding sites | Complementary validation of pharmacophore hits [23] [24] |

Pharmacophore Modeling in Drug Discovery Pipeline

The strategic integration of key pharmacophore features—hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic areas, and ionizable groups—within computational frameworks continues to drive advances in structure-based and ligand-based drug design. As CADD methodologies evolve, particularly through incorporating artificial intelligence and machine learning, pharmacophore modeling maintains its fundamental role in bridging molecular structure and biological activity. The ongoing refinement of these abstract representations of molecular interaction capacities, coupled with emerging computational technologies, promises to enhance the efficiency and success rates of therapeutic development across diverse disease areas. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering these core pharmacophore features remains essential for leveraging the full potential of computer-aided drug discovery in both academic and industrial settings.

In the field of computer-aided drug discovery, the pharmacophore concept represents a fundamental abstraction that distills molecular recognition down to its essential interaction features, deliberately moving beyond specific chemical groups and scaffolds. According to the official IUPAC definition, a pharmacophore is "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interaction with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or block) its biological response" [25]. This definition emphasizes that a pharmacophore is not a specific molecular structure itself, but rather an abstract pattern of functionalities that can be embodied by diverse chemical structures [25]. This conceptual framework enables medicinal chemists to transcend the limitations of particular chemical classes and focus on the essential determinants of biological activity.

The abstract depiction of molecular interactions avoids a bias toward overrepresented functional groups in small datasets, allowing researchers to identify bioisosteric replacements and discover novel scaffold hops [26]. For example, the β-lactam ring in penicillins and cephalosporins represents a classic pharmacophore that remains constant across multiple generations of antibiotics, even as surrounding structures evolve to overcome drug resistance [25]. This abstraction capability makes pharmacophore modeling particularly valuable for scaffold hopping in virtual screening, where the objective is to identify structurally diverse compounds that share the same biological activity through common interaction patterns [26]. By focusing on the spatial arrangement of key chemical features rather than specific atoms or bonds, pharmacophores provide a powerful framework for navigating chemical space and accelerating lead discovery and optimization.

Fundamental Feature Types

Pharmacophore models represent ligands through an abstract collection of chemical features that are essential for molecular recognition and biological activity. These features capture the key interactions between a ligand and its biological target, focusing on the quality of interactions rather than the specific atoms or functional groups producing them. The most common features include hydrogen bond acceptors (HBA) and donors (HBD), hydrophobic regions (H), aromatic rings (RA), positive and negative ionizable groups, and metal-binding moieties [27] [25] [28]. These features represent the capability to form specific non-covalent interactions rather than particular chemical functionalities, enabling the recognition of shared interaction patterns across structurally diverse compounds.

The spatial arrangement of these features is typically defined through interfeature distances and angular relationships that specify the geometric constraints necessary for productive binding [25]. For instance, a pharmacophore model might specify two hydrogen bond acceptors separated by 5.5-6.5 Å and a hydrophobic region positioned 7.2-8.2 Å from both acceptors. This spatial representation captures the essential geometry required for complementary interactions with the target binding site while allowing flexibility in the specific chemical implementations of these features. The abstract nature of this representation enables pharmacophore models to identify structurally diverse compounds that share the same interaction capability, facilitating scaffold hopping and expanding the chemical space available for drug discovery campaigns.

Comparison with Related Concepts

Table 1: Distinguishing Pharmacophores from Related Chemical Concepts

| Concept | Definition | Focus | Level of Abstraction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmacophore | Ensemble of steric and electronic features necessary for optimal supramolecular interactions with a biological target [25] | Interaction capabilities and their spatial arrangement | High (abstract features) |

| Privileged Structure | Structural motifs often associated with biological activity toward multiple targets [25] | Specific molecular scaffolds | Low (concrete structures) |

| Functional Group | Specific grouping of atoms with characteristic chemical behavior | Atomic composition and bonding | None (concrete atoms) |

| Binding Site | Complementary region on the target protein that accommodates the ligand [28] | Structural complementarity | Medium (physical structure) |

It is crucial to distinguish pharmacophores from the related concept of "privileged structures," which are specific structural motifs (e.g., dihydropyridines, benzodiazepines) that frequently appear in biologically active compounds across different target classes [25]. While privileged structures represent concrete molecular scaffolds, pharmacophores describe abstract interaction patterns that can be realized by diverse chemical structures. This distinction highlights the unique value of pharmacophores in enabling scaffold hopping and identifying structurally novel active compounds that might be missed by similarity-based approaches focused on specific molecular frameworks [26].

Methodological Approaches to Pharmacophore Modeling

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

Ligand-based pharmacophore modeling approaches derive pharmacophore models exclusively from a set of known active compounds without requiring structural information about the biological target. These methods operate on the principle that compounds sharing a common biological activity must contain similar features responsible for that activity, arranged in a conserved spatial pattern [29] [28]. The process typically begins with conformational analysis of each active compound to generate multiple 3D conformers, ensuring adequate coverage of the accessible conformational space [28]. Molecular alignment techniques, including common feature alignment and flexible alignment, are then employed to superimpose the active compounds and identify shared pharmacophoric features and their spatial arrangement [28].

The HipHopRefine algorithm, implemented in Catalyst (now part of Discovery Studio), represents a sophisticated ligand-based approach that generates pharmacophore hypotheses from a set of aligned ligands [30]. The algorithm prioritizes compounds based on their activity levels, with highly active compounds (e.g., with IC50 values in the low nanomolar range) typically assigned the highest priority during model generation [30]. The resulting pharmacophore models consist of a collection of chemical features (hydrophobic, hydrogen bond donor/acceptor, charged, aromatic) with associated tolerances for their spatial relationships [30]. Ligand-based methods are particularly valuable when structural information about the target is unavailable, making them widely applicable to various drug targets, including membrane proteins such as GPCRs and ion channels [29].

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

Structure-based pharmacophore modeling approaches derive pharmacophore models directly from the 3D structure of the target protein, typically obtained through X-ray crystallography or homology modeling [28]. These methods analyze the binding site to identify key interaction points and generate complementary pharmacophoric features based on the protein's functional groups and physicochemical properties [28]. The process involves characterizing the binding pocket to identify regions capable of forming hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic interactions, electrostatic interactions, and other non-covalent contacts with ligands. These regions are then translated into corresponding pharmacophore features that define the essential interaction capabilities required for ligands to bind effectively.

Structure-based approaches offer the advantage of not requiring known active ligands, making them particularly valuable for novel targets with few known modulators [28]. Additionally, they can incorporate information about exclusion volumes derived from the protein structure, representing regions that ligands cannot occupy due to steric clashes with the target [30]. However, these methods must account for protein flexibility and induced fit effects, as static protein structures may not accurately represent the conformational changes that occur upon ligand binding [28]. Structure-based pharmacophore generation is often integrated with molecular docking studies to validate the resulting models and ensure they accurately represent the key interactions mediating ligand binding.

Integrated and Advanced Approaches

Recent advances in pharmacophore modeling have blurred the traditional distinction between ligand-based and structure-based approaches, with integrated methods leveraging both ligand activity data and target structural information to generate more comprehensive and reliable pharmacophore models [28]. These hybrid approaches map ligand-based pharmacophores onto protein binding sites to refine and validate the pharmacophoric features, incorporating additional information about protein flexibility and induced-fit effects [28]. The resulting models benefit from both the experimental validation provided by known active compounds and the structural insights derived from the target protein.

Emerging methodologies include quantitative pharmacophore activity relationship (QPhAR) modeling, which extends traditional qualitative pharmacophore models to predict continuous activity values based on pharmacophore features [31] [26]. QPhAR uses machine learning algorithms to establish quantitative relationships between the spatial arrangement of pharmacophoric features and biological activity, enabling not only virtual screening but also activity prediction for novel compounds [26]. Another innovative approach is pharmacophore-guided deep learning for bioactive molecule generation, which uses pharmacophore hypotheses as constraints to guide generative models in producing novel molecules with desired bioactivity [17]. These advanced approaches demonstrate how the abstract representation of pharmacophores can be leveraged to address increasingly complex challenges in drug discovery.

Table 2: Comparison of Pharmacophore Modeling Approaches

| Method | Data Requirements | Key Algorithms/Tools | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ligand-Based | Set of known active compounds | HipHop (Catalyst/Discovery Studio) [30], PHASE [26] | No target structure needed; Directly reflects structure-activity relationships | Dependent on quality and diversity of known actives |

| Structure-Based | 3D structure of target protein | LigandScout [27], MOE [27] | No known ligands needed; Incorporates exclusion volumes | Requires high-quality protein structure; May miss important ligand features |

| Quantitative (QPhAR) | Compounds with continuous activity data | QPhAR algorithm [26] | Predicts activity values; Handles activity cliffs | Requires significant training data; Model quality depends on QPhAR performance [31] |

| Pharmacophore-Guided Generation | Pharmacophore hypothesis | PGMG (Pharmacophore-Guided Molecule Generation) [17] | Generates novel molecules matching pharmacophore; Flexible to different design scenarios | Complex training process; Limited by pharmacophore quality |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol 1: Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling for Virtual Screening

This protocol outlines the steps for developing and validating a ligand-based pharmacophore model for virtual screening applications, based on established methodologies [30] [28]:

Training Set Selection and Preparation: Curate a structurally diverse set of known active compounds with comparable biological activity data (e.g., IC50 or Ki values). Include inactive compounds if available for model validation. Generate multiple low-energy conformations for each compound using conformational analysis tools such as iConfGen [26] or similar algorithms implemented in molecular modeling packages.

Molecular Alignment and Feature Identification: Align the active compounds using flexible alignment algorithms to identify common chemical features and their spatial arrangement. Employ feature detection algorithms to identify hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions, aromatic rings, and charged groups consistently present across active compounds.

Pharmacophore Hypothesis Generation: Use algorithms such as HipHopRefine [30] to generate pharmacophore hypotheses based on the aligned active compounds. Assign higher weights to features present in highly active compounds. Define spatial tolerances for each feature based on the observed variations in the aligned set.

Model Validation: Evaluate the model's ability to discriminate between active and inactive compounds using internal validation (e.g., leave-one-out cross-validation) and external validation with a test set of compounds not used in model development [28]. Calculate statistical metrics including enrichment factor, ROC curves, and AUC values to quantify model performance [28].

Virtual Screening: Apply the validated pharmacophore model to screen large chemical databases (e.g., ZINC, NCI, commercial libraries) to identify potential hits. Use flexible search algorithms to account for ligand conformational flexibility during screening.

Hit Selection and Experimental Validation: Select compounds that match the pharmacophore model for experimental testing, prioritizing structurally diverse scaffolds to maximize scaffold-hopping potential [30].

Protocol 2: Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

This protocol describes the generation of pharmacophore models from protein-ligand complex structures or apo protein structures [28]:

Binding Site Identification and Analysis: Identify the binding site of interest from the protein structure using pocket detection algorithms or literature information. Analyze the binding site to characterize key interaction regions, including hydrogen bonding opportunities, hydrophobic patches, charged areas, and metal coordination sites.

Feature Mapping: Map complementary pharmacophore features onto the binding site, including hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic features, and ionic interaction sites. Define the spatial coordinates and tolerances for each feature based on the geometry of the binding site.

Exclusion Volume Placement: Add exclusion volumes to represent regions occupied by protein atoms that ligands cannot penetrate, derived from the van der Waals surfaces of protein residues lining the binding site [30].

Model Refinement: Refine the initial model by comparing it with known active ligands if available, adjusting feature definitions and tolerances to ensure compatibility with known structure-activity relationships.

Virtual Screening and Validation: Apply the structure-based pharmacophore model for virtual screening following similar steps to the ligand-based protocol, with particular attention to handling ligand flexibility and protein conformational variability.

QPhAR Workflow for Quantitative Pharmacophore Modeling

The QPhAR workflow represents an advanced approach for building quantitative pharmacophore models that predict continuous activity values [31] [26]:

Dataset Preparation: Collect a set of compounds with measured biological activity values (e.g., IC50, Ki). Split the data into training and test sets using appropriate stratification to ensure representative distribution of activity values and structural diversity.

Consensus Pharmacophore Generation: Generate a merged consensus pharmacophore that represents common features across the training set compounds, accounting for their bioactive conformations [26].

Feature Alignment and Descriptor Calculation: Align all training set pharmacophores to the consensus pharmacophore and extract position-dependent information relative to the merged model to create feature descriptors [26].

Model Training: Use machine learning algorithms (e.g., partial least squares regression, random forests, or neural networks) to establish a quantitative relationship between the pharmacophore descriptors and biological activity values [26].

Model Validation: Validate the QPhAR model using cross-validation techniques and external test sets, calculating performance metrics such as R², RMSE, and Q² to assess predictive capability [26]. A robust QPhAR model should achieve RMSE values competitive with traditional QSAR methods while providing better interpretability and scaffold-hopping potential [26].

The following diagram illustrates the automated end-to-end QPhAR workflow:

Figure 1: QPhAR Automated Workflow for Quantitative Pharmacophore Modeling

Validation Strategies and Performance Metrics

Statistical Validation Methods

Robust validation is essential to ensure the predictive capability and reliability of pharmacophore models. Both internal and external validation strategies should be employed to assess model quality comprehensively [28]. Internal validation techniques, such as leave-one-out cross-validation and bootstrapping, evaluate the model's stability and performance on the training set compounds [28]. External validation using an independent test set of compounds not included in model development provides a more realistic assessment of the model's predictive power for novel compounds [28]. The test set should include both active and inactive compounds to properly evaluate the model's ability to discriminate between them.

For quantitative pharmacophore models, standard regression metrics including R², RMSE (Root Mean Square Error), and Q² (cross-validated R²) should be reported [26]. In validation studies across diverse datasets, QPhAR models have demonstrated average RMSE values of approximately 0.62 with a standard deviation of 0.18, indicating robust predictive performance across different target classes [26]. For classification models, metrics such as enrichment factor, ROC curves, AUC values, sensitivity, specificity, and precision provide comprehensive assessment of model performance in distinguishing active from inactive compounds [28]. The Fβ-score and FSpecificity-score are particularly valuable for virtual screening applications where the objective is to maximize true positives while controlling false positives [31].

Application-Based Validation

Beyond statistical metrics, pharmacophore models should be validated through practical application to virtual screening campaigns with subsequent experimental confirmation. Successful identification of novel active compounds through pharmacophore-based screening provides the most compelling validation of model utility [30]. For example, in a study targeting microsomal prostaglandin E2 synthase-1 (mPGES-1), pharmacophore-based virtual screening identified nine novel inhibitor scaffolds with IC50 values ranging from 0.4 to 7.9 μM, demonstrating the practical utility of the approach for lead discovery [30].

Application-based validation should also assess the scaffold-hopping potential of pharmacophore models by examining the structural diversity of identified hits compared to the training set compounds [26]. Successful models should identify active compounds with novel scaffolds that were not represented in the training data, demonstrating that the model has captured the essential interaction patterns rather than memorizing specific structural motifs. This capability is particularly valuable for overcoming intellectual property constraints and exploring novel chemical space in drug discovery programs.

Table 3: Key Software Tools for Pharmacophore Modeling

| Tool/Software | Type | Key Features | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| LigandScout [27] | Commercial | Structure-based and ligand-based pharmacophore modeling; Virtual screening | High-performance pharmacophore modeling with advanced visualization |

| Discovery Studio [27] | Commercial | HipHop/Hypogen algorithms; QSAR integration; Comprehensive modeling environment | End-to-end pharmacophore modeling workflows in industrial settings |

| MOE (Molecular Operating Environment) [27] | Commercial | Pharmacophore modeling, docking, and molecular dynamics in unified platform | Integrated structure-based design in pharmaceutical R&D |

| Pharmit [27] | Online Platform | Online pharmacophore modeling and virtual screening | Rapid accessible screening for academic researchers |

| PHASE [26] | Commercial (Schrödinger) | 3D pharmacophore fields; PLS-based QSAR | Quantitative pharmacophore modeling aligned with molecular fields |

| QPhAR [26] | Research Algorithm | Quantitative pharmacophore activity relationship; Machine learning integration | Building predictive quantitative models from pharmacophores |

The abstract nature of pharmacophores, focusing on essential molecular interaction features beyond specific chemical groups, represents a powerful paradigm for navigating the complexity of molecular recognition in drug discovery. By distilling ligand-receptor interactions to their fundamental components and spatial relationships, pharmacophore modeling enables scaffold hopping, facilitates exploration of novel chemical space, and provides a rational framework for lead optimization [26]. The continued evolution of pharmacophore methods, including quantitative approaches like QPhAR and integration with deep learning for molecule generation, promises to further enhance the utility of this abstract representation in addressing challenging drug discovery problems [17] [31] [26].

As structural biology advances provide increasing insights into protein-ligand interactions, and machine learning algorithms become more sophisticated at extracting patterns from complex data, the abstract representation offered by pharmacophores will continue to serve as a valuable intermediary between structural information and functional activity. This positions pharmacophore modeling as an enduring and evolving methodology in the computational drug discovery toolkit, capable of bridging the gap between structural complexity and functional abstraction to accelerate the identification and optimization of novel therapeutic agents.

Building and Applying Pharmacophore Models: Structure-Based and Ligand-Based Approaches

Computer-Aided Drug Discovery (CADD) employs computational tools to investigate molecular properties and develop novel therapeutic solutions, reducing the time and costs associated with traditional drug development [9]. Within the CADD toolkit, pharmacophore modeling represents one of the most sophisticated and widely used strategies for hit identification and optimization [10]. According to the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC), a pharmacophore is defined as "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target and to trigger (or block) its biological response" [9] [10]. In essence, a pharmacophore model abstracts the key chemical functionalities required for biological activity into a three-dimensional arrangement of features, independent of a specific molecular scaffold [9].

Pharmacophore modeling approaches are broadly classified into two categories: ligand-based and structure-based [9]. Ligand-based methods derive models from the structural alignment and common features of known active compounds. In contrast, structure-based pharmacophore modeling, the focus of this technical guide, extracts critical interaction points directly from the three-dimensional structure of a protein-ligand complex [32] [9]. This approach provides an atomic-level insight into the binding interactions, making it a powerful tool for virtual screening when a reliable target structure is available [10]. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of the structure-based pharmacophore modeling workflow, its applications in drug discovery, and recent methodological advances.

Theoretical Foundations and Definition

The structure-based approach operates on the fundamental principle of molecular recognition, identifying and mapping the complementary chemical features between a ligand and its binding pocket [9]. The model is generated by analyzing the protein-ligand complex to pinpoint the amino acid residues and ligand functional groups that participate in key interactions, such as hydrogen bonding, ionic attractions, and hydrophobic contacts [9].

These interactions are translated into abstract pharmacophore features. The most common pharmacophoric feature types include [9]:

- Hydrogen Bond Acceptors (HBA)

- Hydrogen Bond Donors (HBD)

- Hydrophobic areas (H)

- Positively and Negatively Ionizable groups (PI/NI)

- Aromatic rings (AR)

- Metal Coordinating areas

In addition to these chemical features, exclusion volumes (XVOL) are often added to represent the steric constraints of the binding pocket, indicating regions where ligand atoms cannot be positioned due to clashing with the protein [9]. The resulting model serves as a 3D query that can screen chemical libraries for molecules possessing the same spatial arrangement of essential features, thereby predicting potential biological activity.

A Step-by-Step Workflow for Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

The generation of a robust, structure-based pharmacophore model follows a systematic protocol. The flowchart below illustrates the key stages of this process.

Figure 1: The core workflow for developing a structure-based pharmacophore model, from initial data preparation to final validation.

Protein-Ligand Complex Preparation

The initial and a critical step involves curating the input structure. The 3D structure of the target, typically a protein-ligand complex, is often sourced from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) [9]. The quality of this input structure directly determines the quality of the resulting pharmacophore model [9].

Key preparation steps include:

- Structure Quality Assessment: Evaluate the resolution of crystal structures, check for missing atoms or residues, and assess the overall stereochemical quality.

- Protonation: Add hydrogen atoms, which are absent in X-ray structures, and assign correct protonation states to amino acid residues at the physiological pH of interest.

- Energy Minimization: Perform a limited optimization to relieve steric clashes introduced during the protonation process.

- Ligand Handling: Ensure the bound ligand's structure and geometry are chemically sensible.

If an experimental structure is unavailable, alternative approaches such as homology modeling or the use of AI-based structure prediction tools like AlphaFold2 can generate a reliable 3D model for the target [9]. Molecular docking can also be used to generate a protein-ligand complex if the binding pose of an active compound is unknown [9].

Binding Site Detection and Analysis

The next step is to identify and characterize the ligand-binding site. While this can be done manually by inspecting the co-crystallized ligand, automated tools are often employed for a more comprehensive analysis [9]. These tools probe the protein surface to locate cavities with favorable properties for ligand binding.

Commonly used programs are:

- GRID: A grid-based method that uses different chemical probes to sample the protein surface and identify energetically favorable interaction sites, generating molecular interaction fields [9].

- LUDI: A knowledge-based tool that predicts potential interaction sites using geometric rules derived from statistical analyses of non-bonded contacts in experimental structures [9].

Pharmacophore Feature Generation and Selection

Using the prepared protein-ligand complex, the software identifies potential pharmacophore features by analyzing the interactions between the ligand and the binding site residues. Initially, a large number of features may be detected. Therefore, it is crucial to select only those that are essential for ligand binding and bioactivity to create a selective and effective model [9] [10].

Feature selection can be guided by:

- Energetic Contribution: Prioritizing features that contribute significantly to the binding energy.

- Evolutionary Conservation: Selecting interactions with conserved residues, often identified through sequence alignments.

- Structural Conservation: If multiple protein-ligand complexes are available, identifying the most conserved interactions across different structures.

- Spatial Constraints: Incorporating exclusion volumes to represent the shape of the binding pocket, which helps in discerning molecules that are sterically incompatible with the target [9].

Advanced Methodologies and Recent Advances

The field of structure-based pharmacophore modeling is evolving beyond static crystal structures to incorporate dynamics and complex data representation.

Incorporating Molecular Dynamics

Proteins are flexible entities, and interactions with ligands are inherently dynamic. Static X-ray structures may not capture all relevant binding modes or protein conformations. To address this, Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations are now frequently used to sample the conformational space of a protein-ligand complex [33]. Pharmacophore models can be generated from multiple snapshots of an MD trajectory, capturing transient but critical interactions that are absent in the static structure [33]. This approach leads to the creation of an ensemble of pharmacophore models, providing a more holistic view of the binding interactions.

Hierarchical Graph Representation

To manage and visualize the multitude of pharmacophore models generated from MD simulations, the Hierarchical Graph Representation of Pharmacophore Models (HGPM) has been developed [33]. This method represents all unique pharmacophore models and their relationships in a single, interactive graph. The HGPM provides an intuitive tool for analysts to observe feature hierarchies, identify consensus patterns, and strategically select a subset of models for virtual screening campaigns, thereby reducing computational overhead while maintaining model diversity [33].

Shape-Focused and AI-Enhanced Modeling

Recent innovations are integrating shape matching and artificial intelligence into pharmacophore modeling.

- Shape-Focused Models: Algorithms like O-LAP generate cavity-filling models by clustering overlapping atoms from top-ranked docking poses of active ligands. These models focus on the overall shape and electrostatic complementarity between the ligand and the binding pocket, and have shown significant success in improving docking enrichment in virtual screening [34].

- AI Integration: Tools like dyphAI integrate machine learning with ensemble pharmacophore models derived from MD simulations. This approach captures key protein-ligand interaction patterns and has been successfully applied to discover novel, potent acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, demonstrating the power of combining dynamic pharmacophore modeling with AI-driven virtual screening [35].

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

The successful application of structure-based pharmacophore modeling relies on a suite of software tools and data resources. The table below details key components of the modern computational pharmacologist's toolkit.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Software Solutions for Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling.

| Tool/Resource Name | Type/Function | Key Application in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB) [9] | Data Repository | Source of experimental 3D structures of protein-ligand complexes. |

| GRID [9] | Software Module | Identifies energetically favorable interaction sites in the binding pocket. |

| LUDI [9] | Software Algorithm | Predicts potential interaction sites using knowledge-based geometric rules. |

| LigandScout [33] [34] | Pharmacophore Modeling Software | Generates structure-based pharmacophore models from PDB structures or MD snapshots; includes virtual screening capabilities. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) [33] | Simulation Technique | Samples protein flexibility and generates an ensemble of conformations for model building. |

| O-LAP [34] | Graph Clustering Algorithm | Generates shape-focused pharmacophore models by clustering atoms from docked ligands. |

| dyphAI [35] | AI-Integrated Platform | Combines machine learning with dynamic pharmacophore models for enhanced virtual screening. |

| Exclusion Volumes (XVOL) [9] | Pharmacophore Feature | Represents steric constraints of the binding pocket to improve model selectivity. |

Application in Virtual Screening: A Practical Protocol

The primary application of a validated pharmacophore model is in virtual screening (VS) of large compound libraries to identify novel hit molecules [10]. The following protocol outlines a typical VS campaign.

Protocol: Virtual Screening Using a Structure-Based Pharmacophore Model

- Query Creation: Load the validated pharmacophore model into screening software (e.g., LigandScout). Use exclusion volumes to define the steric boundaries of the pocket [9].

- Database Preparation: Convert a commercial or in-house compound library (e.g., ZINC, ChEMBL) into a searchable 3D format. This involves generating multiple conformers for each molecule to ensure flexibility during the matching process [33] [35].

- Screening Run: Execute the screening query. The algorithm will rapidly scan the database and match compounds that fit the spatial and chemical constraints of the pharmacophore model.

- Hit Analysis and Post-Processing: Analyze the top-ranking hits.

- Visual Inspection: Manually check the alignment of hits with the pharmacophore features.

- Docking Validation: Subject the hits to molecular docking to refine the binding pose and estimate affinity [34].