Pharmacophore Modeling for Estrogen Receptor Alpha Inhibitors: From Foundational Concepts to AI-Driven Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of pharmacophore modeling as a pivotal computational strategy for identifying and optimizing Estrogen Receptor Alpha (ERα) inhibitors, a critical therapeutic target in hormone receptor-positive...

Pharmacophore Modeling for Estrogen Receptor Alpha Inhibitors: From Foundational Concepts to AI-Driven Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of pharmacophore modeling as a pivotal computational strategy for identifying and optimizing Estrogen Receptor Alpha (ERα) inhibitors, a critical therapeutic target in hormone receptor-positive breast cancer. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, the content spans from foundational principles and key ERα structural features to advanced methodological applications, including structure-based and ligand-based approaches. It further addresses common challenges and optimization strategies, such as managing structural flexibility and balancing novelty with pharmacophoric fidelity. The discussion extends to rigorous validation protocols using molecular dynamics, MM-PBSA, and in vitro assays, alongside comparative analyses of novel compounds against established therapies. By synthesizing insights from recent case studies and emerging AI methodologies, this resource aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to leverage pharmacophore modeling for accelerating the discovery of next-generation ERα-targeted therapeutics.

Understanding ERα and the Core Principles of Pharmacophore Modeling

The Critical Role of ERα in Breast Cancer Pathogenesis and Therapy

Estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) is a ligand-activated transcription factor that belongs to the nuclear receptor superfamily and serves as the primary driver in the majority of breast cancer cases. As a critical regulatory protein, ERα mediates the hormonal development of breast cancer, with approximately 70% of diagnosed cases exhibiting overexpression of this receptor [1] [2]. The central role of ERα in breast cancer pathogenesis establishes it as a pivotal therapeutic target for intervention strategies. Upon activation by its primary ligand, 17β-estradiol (E2), ERα undergoes conformational changes that enable it to regulate transcriptional programs governing cell proliferation, survival, and differentiation [3] [4]. The significance of ERα extends beyond its biological functions to encompass critical clinical applications, as ERα status serves as an essential biomarker for breast cancer classification, treatment decisions, and prognosis assessment [5] [2]. Understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying ERα signaling and its regulation provides the foundation for developing targeted therapies that have substantially improved outcomes for patients with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer.

Molecular Mechanisms of ERα Signaling

Genomic and Non-Genomic Signaling Pathways

ERα exerts its biological effects through multiple distinct signaling mechanisms categorized as genomic and non-genomic pathways. The classical genomic pathway involves direct DNA binding, where ligand-activated ERα dimerizes and translocates to the nucleus, binding to specific DNA sequences known as estrogen response elements (EREs) to regulate gene transcription [4]. This direct genomic signaling results in the expression of genes involved in cell cycle progression (e.g., cyclin D1), anti-apoptosis (e.g., Bcl-2), and estrogen biosynthesis [4]. Additionally, ERα employs an indirect genomic mechanism by tethering to other transcription factors such as AP-1 and SP-1, thereby modulating gene expression without direct ERE binding [3].

Parallel to these genomic actions, ERα mediates rapid non-genomic effects through interactions with cytoplasmic signaling proteins, including kinases and G protein-coupled receptors. These non-genomic actions activate downstream signaling cascades such as PI3K/Akt and MAPK pathways, contributing to cell growth and survival [4]. The complexity of ERα signaling is further enhanced by its cross-talk with other nuclear receptors, including Estrogen-Related Receptor Alpha (ESRRA), which cooperates with ERα in orchestrating transcriptional activation of super enhancers and target genes [6] [7].

Structural Dynamics and Conformational Regulation

The functional versatility of ERα is governed by structural dynamics within its ligand-binding domain (LBD), particularly the conformation of helix-12 (H12), which serves as a molecular switch determining receptor activity. Recent structural insights have revealed that H12 adopts distinct conformational states—active (estrogen-bound), inactive (SERM/SERD-bound), and a third unique conformation in the unliganded (apo) state [8]. In the active state, H12 positions itself perpendicular to H3 and H4, forming the activation function-2 (AF2) surface that enables coactivator recruitment through conserved LxxLL motifs [8]. The apo state reveals H12 in a vertical orientation wedged between H3 and H11, enclosing the ligand-binding pocket and partially masking the AF2 interface [8].

This structural understanding provides critical insights into the mechanistic basis of cancer-associated mutations, particularly Y537S and D538G within H12, which disrupt contacts stabilizing the apo conformation and confer constitutive receptor activation, driving tumor development and endocrine resistance [8]. The ternary switch model of H12 conformation offers a framework for understanding ligand-dependent and independent regulation of ERα, with significant implications for therapeutic intervention.

Table 1: Key Structural Elements Governing ERα Function

| Structural Element | Functional Role | Clinical/Therapeutic Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Helix-12 (H12) | Determines receptor activity state; forms AF2 surface | Target for SERMs/SERDs; site of resistance mutations |

| Activation Function-2 (AF2) Surface | Binding interface for LxxLL motifs of coactivators | Determines transcriptional output |

| Ligand-Binding Pocket (LBP) | Binds estrogens, SERMs, SERDs | Primary target for endocrine therapies |

| F-domain | Disordered C-terminus containing phospho-T594 | Recognition site for 14-3-3 protein; alternative targeting strategy |

ERα Signaling Pathway Visualization

Current ERα-Targeted Therapeutic Approaches

Established Endocrine Therapies

Targeted therapies against ERα represent the cornerstone of treatment for hormone receptor-positive breast cancer and are categorized based on their mechanism of action. Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators (SERMs), such as tamoxifen and raloxifene, function as mixed agonists/antagonists by binding to the ERα LBD and inducing conformational changes that prevent the receptor from adopting an active state [3]. Selective Estrogen Receptor Degraders (SERDs), including fulvestrant, operate as full antagonists that promote ERα downregulation and proteasomal degradation [3]. These therapeutic approaches have demonstrated significant clinical efficacy; however, their effectiveness is often limited by the development of acquired resistance, particularly through mutations in the LBD that enable ligand-independent activation [3] [2].

The structural basis for these therapies lies in their differential impact on H12 conformation. Agonists stabilize H12 in the active position, facilitating coactivator recruitment, while SERMs and SERDs displace H12, remodeling the AF2 surface to prevent productive coactivator binding and promote corepressor recruitment [8]. Understanding these precise molecular mechanisms provides the foundation for developing next-generation ERα-targeted therapies capable of overcoming resistance mechanisms.

Emerging Alternative Strategies

Beyond direct LBD targeting, innovative approaches are emerging that focus on alternative mechanisms to inhibit ERα signaling. Stabilization of the native protein-protein interaction between 14-3-3 and the disordered C-terminus of ERα represents a promising strategy, particularly for cases involving acquired endocrine resistance [9]. Molecular glues that strengthen the 14-3-3/ERα complex have been developed using scaffold-hopping approaches based on multi-component reaction chemistry, leading to drug-like analogs that effectively stabilize this PPI and inhibit ERα transcriptional activity [9].

Another emerging target is ESRRA, an orphan nuclear receptor that cooperates with ERα in transcriptional activation. Pharmacological inhibition of ESRRA using inverse agonists such as XCT790 has demonstrated suppression of estrogen/ERα-induced gene transcription while enhancing type I interferon pathway and antitumor immunity, thereby restraining ERα-positive breast cancer growth [6] [7]. Combination treatments with XCT790 and established endocrine therapies have produced synergistic antitumor effects and resensitized tamoxifen-resistant ERα-positive breast cancer cells to treatment [6] [7].

Table 2: Current and Emerging ERα-Targeted Therapeutic Approaches

| Therapeutic Class | Representative Agents | Mechanism of Action | Clinical Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| SERMs | Tamoxifen, Raloxifene, Toremifene | Mixed agonist/antagonist; prevents active conformation | First-line endocrine therapy; prevention in high-risk patients |

| SERDs | Fulvestrant | Promotes ERα degradation; pure antagonist | Second-line after SERM failure; metastatic setting |

| Aromatase Inhibitors | Letrozole, Anastrozole, Exemestane | Reduces estrogen production | Postmenopausal women; often superior to tamoxifen |

| Molecular Glues | GBB-based compounds (under development) | Stabilizes 14-3-3/ERα interaction; inhibits transcription | Potential for overcoming LBD mutations |

| ESRRA Inhibitors | XCT790 (experimental) | Suppresses ERα/ESRRA cooperativity; enhances interferon signaling | Preclinical; combination therapy to overcome resistance |

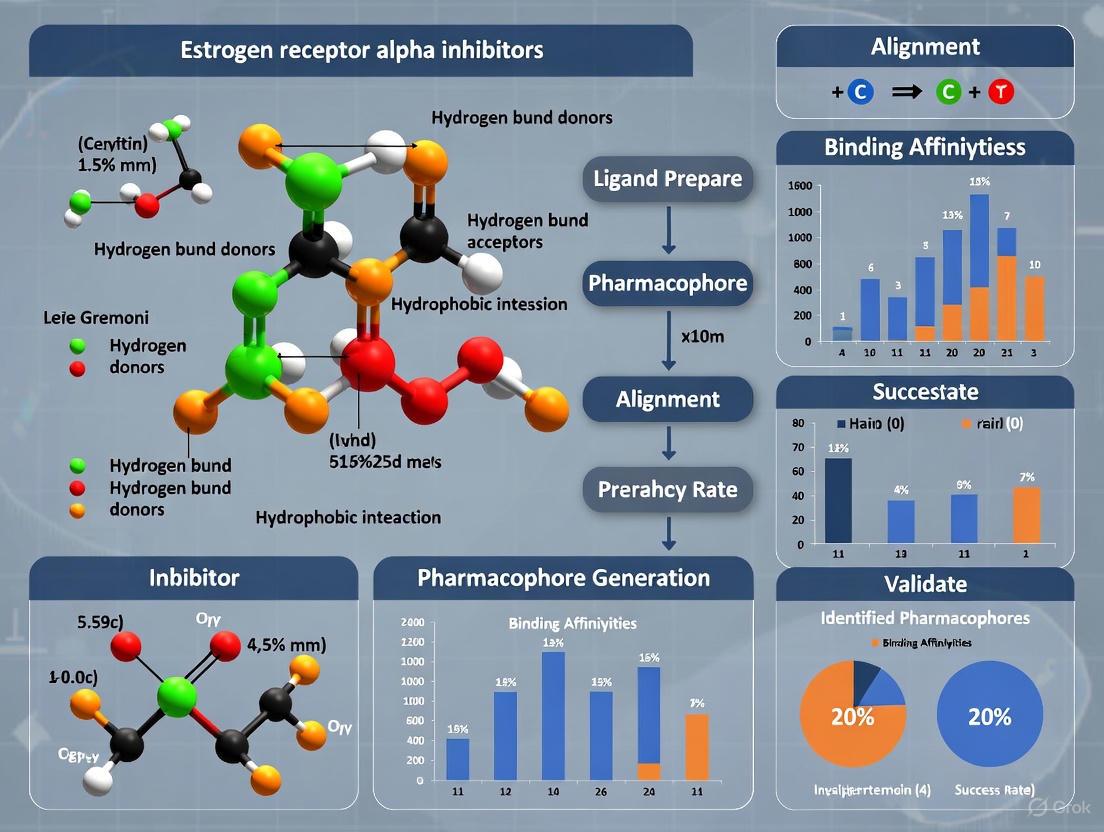

Pharmacophore Modeling for ERα Inhibitor Development

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

Structure-based pharmacophore modeling has emerged as a powerful computational approach for identifying and optimizing ERα inhibitors. This methodology utilizes the three-dimensional structural information from ERα-ligand complexes to define the essential chemical features necessary for molecular recognition and binding [3] [1]. Advanced pharmacophore models incorporate data from both wild-type and mutated ERα LBDs co-crystallized with partial agonists, SERMs, and SERDs, enabling the identification of key interaction points including hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions, and aromatic ring features [3]. These models have successfully guided virtual screening campaigns of large compound databases, leading to the identification of novel hit compounds such as Brefeldin A, which was subsequently optimized toward derivatives with picomolar to low nanomolar potency against ERα [3].

Complementary to structure-based approaches, ligand-based pharmacophore models developed from diverse inhibitor datasets have provided additional insights into critical pharmacophoric features, revealing that atoms with sp2-hybridization, lipophilic character, and specific combinations of hydrogen bond donors and acceptors significantly impact binding affinity [10]. The integration of these computational approaches with experimental validation has accelerated the discovery of novel ERα antagonists with improved efficacy and potentially reduced side effects compared to established therapies.

Three-Dimensional Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (3D-QSAR) Models

The application of three-dimensional QSAR modeling, particularly Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) and Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA), has significantly advanced ERα inhibitor optimization. These methodologies establish robust correlations between the spatial arrangement of molecular features and biological activity, enabling predictive optimization of compound potency [1]. For thiophene-[2,3-e]indazole derivatives, reliable 3D-QSAR models have been developed (CoMFA: Q² = 0.515, R² = 0.934; CoMSIA: Q² = 0.548, R² = 0.987), identifying key protein residues including GLU-353, ARG-394, PHE-404, ASP-351, TRP-383, and HIS-524 as critical for compound-protein interactions [1].

Molecular dynamics simulations further validate the stability of compound-ERα binding through analysis of RMSD, RMSF, binding free energy, and other parameters, providing atomic-level insights into the persistence of key interactions under dynamic conditions [1]. These computational approaches collectively form a powerful toolkit for rational drug design, enabling the efficient optimization of lead compounds with enhanced binding affinity and specificity for ERα.

Pharmacophore Modeling Workflow

Experimental Protocols for ERα Research

Protocol 1: Structure-Based Pharmacophore Model Development

Objective: To develop predictive structure-based pharmacophore models for virtual screening of novel ERα inhibitors.

Materials and Reagents:

- Structural data of ERα-ligand complexes from Protein Data Bank

- Molecular modeling software (e.g., MOE, Discovery Studio)

- Compound databases for virtual screening (e.g., NCI database)

- High-performance computing resources

Procedure:

- Structural Data Compilation: Retrieve all available ERα structures co-crystallized with partial agonists, SERMs, and SERDs from the PDB. Curate a dataset ensuring structural diversity and relevant biological annotations.

- Structure Preparation: Prepare protein structures by removing water molecules (except functionally relevant ones), adding hydrogen atoms, and optimizing hydrogen bonding networks using molecular modeling software.

- Pharmacophore Feature Identification: For each ERα-ligand complex, identify critical interaction features including:

- Hydrogen bond donors and acceptors

- Hydrophobic and aromatic regions

- Charged/ionizable features

- Exclusion volumes

- Model Generation and Validation: Generate multiple pharmacophore hypotheses using structure-based algorithms. Validate models using test sets of known active and inactive compounds. Select optimal model based on Guner-Henry scoring metrics and statistical significance.

- Virtual Screening: Employ validated pharmacophore model for screening compound databases. Apply filters for drug-likeness and synthetic accessibility.

- Hit Selection and Validation: Select top-ranking compounds for experimental validation using cell-based and biochemical assays.

Protocol 2: Evaluation of ERα-SVCT2 Regulatory Axis

Objective: To investigate the regulatory relationship between ERα and SVCT2 and its implications for chemoresistance.

Materials and Reagents:

- ERα-positive breast cancer cell lines (MCF7, T47D)

- ERα-negative breast cancer cell lines (MDA-MB-231)

- siRNA targeting ERα and SVCT2

- Antibodies for ERα, SVCT2, XIAP, p53

- Doxorubicin and other chemotherapeutic agents

- Ascorbic acid (vitamin C)

- Cycloheximide

- Proteasome inhibitors (e.g., MG132)

Procedure:

- Correlation Analysis: Examine endogenous expression levels of ERα and SVCT2 across multiple breast cancer cell lines using Western blot analysis.

- Knockdown Studies: Perform concentration-dependent knockdown of ERα using type I siRNA in MCF7 and T47D cells. Assess SVCT2 protein and mRNA levels at 48-72 hours post-transfection.

- Localization Studies: Determine subcellular localization of SVCT2 and ERα using cellular fractionation followed by Western blotting.

- Transcriptional Activity Assessment: Measure SVCT2 transcriptional activity using luciferase reporter assays following ERα knockdown. Investigate p53 involvement through concomitant p53 knockdown experiments.

- Protein Stability Assay: Evaluate SVCT2 protein stability using cycloheximide chase assays in control and ERα knockdown conditions. Treat cells with cycloheximide to inhibit new protein synthesis and collect samples at various time points for Western blot analysis.

- Ubiquitination Studies: Investigate SVCT2 ubiquitination in ERα-deficient conditions using immunoprecipitation followed by ubiquitin detection. Assess XIAP involvement as E3 ligase through XIAP knockdown experiments.

- Chemosensitivity Testing: Evaluate doxorubicin-induced cytotoxicity in ERα and SVCT2 knockdown conditions using MTT or similar viability assays. Analyze ABC transporter gene expression changes via qRT-PCR.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for ERα Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Lines | MCF7, T47D, MDA-MB-231 | Model systems for ERα+ and ERα- breast cancer |

| Chemical Inhibitors | Tamoxifen, Fulvestrant, XCT790 | ERα antagonists and degraders for mechanistic studies |

| siRNA/shRNA | ERα-targeting, SVCT2-targeting, XIAP-targeting | Gene knockdown to study pathway relationships |

| Antibodies | Anti-ERα, Anti-SVCT2, Anti-XIAP, Anti-p53 | Protein detection in Western blot, IP, IHC |

| Computational Tools | MOE, Discovery Studio, AutoDock | Structure-based drug design and molecular modeling |

| Expression Vectors | His-tagged ERα, Myc-tagged SVCT2 | Protein overexpression and interaction studies |

| Reporters | Luciferase constructs with EREs | Transcriptional activity assessment |

| Chemotherapeutic Agents | Doxorubicin | Chemosensitivity testing in resistance models |

Emerging Strategies and Future Directions

The evolving understanding of ERα pathogenesis and resistance mechanisms has catalyzed the development of innovative therapeutic strategies that extend beyond conventional endocrine therapies. Emerging approaches include the targeting of protein-protein interactions involving ERα, particularly through molecular glues that stabilize the 14-3-3/ERα complex [9]. The application of multi-component reaction chemistry has enabled rapid derivatization and optimization of drug-like molecular glue scaffolds, such as imidazo[1,2-a]pyridines developed via the Groebke-Blackburn-Bienaymé reaction, which demonstrate efficacy in stabilizing PPIs and inhibiting ERα transcriptional activity [9].

Another promising avenue involves targeting the regulatory axis between ERα and nutrient transport systems, particularly the ERα-SVCT2 relationship. The discovery that ERα maintains SVCT2 protein stability and that XIAP-mediated ubiquitination regulates SVCT2 degradation in ERα-deficient conditions reveals a novel mechanism contributing to chemoresistance [4]. Therapeutic strategies targeting XIAP or modulating SVCT2 may represent promising approaches for overcoming resistance in ERα-positive breast cancer [4].

The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning in drug discovery platforms is accelerating the identification of novel ERα-targeted therapies. AI-enabled approaches enhance early diagnosis and enable patient-tailored therapeutic strategies by analyzing complex datasets including circulating tumor DNA, advanced imaging, and multi-omics profiles [2]. These computational advances, combined with structural insights and innovative therapeutic modalities, promise to transform the landscape of ERα-positive breast cancer treatment, offering new opportunities to overcome resistance and improve patient outcomes.

Estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) is a well-established therapeutic target for hormone receptor-positive breast cancer, which constitutes approximately 70-75% of all breast cancer cases [11] [12] [13]. The development of selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) and degraders (SERDs) represents a cornerstone of endocrine therapy, yet challenges with drug resistance and side effects persist [11] [12]. Pharmacophore modeling serves as a powerful computational approach to identify the essential steric and electronic features necessary for a molecule to interact with ERα and elicit an antagonistic response, thereby guiding the rational design of novel therapeutics with improved efficacy and safety profiles [14] [10].

This application note delineates the critical chemical features defining the ERα antagonist pharmacophore, supported by quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) data and molecular interaction analyses. Furthermore, it provides detailed protocols for employing these models in virtual screening and lead optimization campaigns within breast cancer drug discovery.

Core Pharmacophore Features for ERα Antagonism

Comprehensive analysis of co-crystallized ERα-antagonist complexes and QSAR studies reveals a consistent set of chemical features crucial for binding and functional antagonism. The table below summarizes the core pharmacophore features and their roles.

Table 1: Core Pharmacophore Features for ERα Antagonism

| Feature | Spatial & Chemical Properties | Role in Binding & Antagonism | Key Interacting Residues |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrophobic Groups | 1-2 aromatic or aliphatic rings; ClogP contribution [10] | Occupy hydrophobic sub-pockets; stabilizes ligand binding [15] [16] | Leu349, Leu387, Leu391, Met421, Ile424 [15] [16] |

| Hydrogen Bond Acceptors | 1-2 features; distance from hydrophobic core ~6-8 Å [14] | Critical for anchoring ligand via H-bonds [16] [17] | Glu353, Arg394 [16] [17] |

| Hydrogen Bond Donors | Often a phenolic or hydroxyl group [13] | Forms key H-bonds with binding pocket [17] [13] | Glu353, Arg394, His524 [17] [13] |

| Excluded Volumes | Defined by protein backbone and side chains [14] | Prevents ligand from adopting agonist-like pose; crucial for antagonist profile [14] | Governed by helix 12 positioning [14] |

The spatial arrangement of these features is critical. The canonical antagonist pharmacophore often requires a rigid core structure to maintain the correct distance and orientation between key features, particularly between hydrophobic moieties and hydrogen bond forming groups [15] [9]. Introducing conformational constraints has been shown to improve both binding affinity and antagonist efficacy by pre-organizing the ligand for optimal interactions with the binding pocket [9].

Quantitative Data and Validation

The predictive power of pharmacophore models is quantified through rigorous validation metrics. The following table compiles performance data from published ERα antagonist models, demonstrating their utility in distinguishing active from inactive compounds.

Table 2: Validation Metrics for ERα Antagonist Pharmacophore and QSAR Models

| Model Type | Dataset | Key Performance Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3D QSAR (Atom-Based) | Training Set (TR) of 39 co-crystal ligands | R² = 0.799, Q²LMO = 0.792, CCCex = 0.886 | [14] [10] |

| Machine Learning (Naive Bayesian) | BindingDB actives & DUD-E decoys | Sensitivity: 0.79, Specificity: 0.98, MCC: 0.80 | [11] |

| Machine Learning (Recursive Partitioning) | BindingDB actives & DUD-E decoys | Sensitivity: 0.75, Specificity: 0.96, MCC: 0.74 | [11] |

| Structure-Based Pharmacophore | External test set (97 known binders) | Successful identification of Brefeldin A as a hit; guided optimization to picomolar-potency leads (3DPQ series) | [14] |

These models have successfully driven the discovery and optimization of novel ERα antagonists. For instance, a structure-based 3D-QSAR model guided the hit-to-lead optimization of Brefeldin A, resulting in derivatives (3DPQ series) with picomolar to low nanomolar potency against ERα [14]. In another study, a ligand-based machine learning model combined with molecular docking identified several natural products as ERα antagonists, including genistein, ellagic acid, and epigallocatechin-3-gallate, which were experimentally validated in reporter gene assays [11].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

This protocol details the generation of a structure-based pharmacophore model using a known ERα-ligand complex.

Protein Preparation:

- Obtain the crystal structure of the ERα ligand-binding domain (LBD) in complex with an antagonist (e.g., PDB ID: 3ERT for 4-hydroxytamoxifen) [15] [16].

- Using software like Schrödinger's Protein Preparation Wizard or MOE, remove the native ligand and all water molecules. Add hydrogen atoms, assign bond orders, and optimize the protonation states of key residues (e.g., Glu353, Arg394) at physiological pH (7.4).

- Perform energy minimization of the protein structure using an appropriate force field (e.g., OPLS3e or MMFF94s) to relieve steric clashes, constraining heavy atoms to their crystallographic positions with a root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) cutoff of 0.3 Å.

Pharmacophore Generation:

- In molecular modeling suites such as Schrödinger's PHASE [14] or LigandScout [15] [16], use the prepared protein structure to automatically generate pharmacophore features based on protein-ligand interaction sites.

- Define features including:

- Hydrogen bond donors (interacting with Glu353, Arg394)

- Hydrogen bond acceptors (interacting with Arg394, His524)

- Hydrophobic features (targeting pockets around Leu387, Met421)

- Excluded volumes (to represent protein atoms and enforce antagonist pose by blocking helix 12) [14].

Model Refinement & Validation:

Protocol 2: Virtual Screening Workflow

This protocol applies the validated pharmacophore model to screen compound libraries for novel ERα antagonists.

Library Preparation:

- Prepare a database of compounds for screening (e.g., in-house natural product library, ZINC database, or NCI Diversity Set) [11] [18].

- Generate low-energy 3D conformers for each compound. Perform geometry optimization using a force field like MMFF94 [17]. Filter the library using Lipinski's Rule of Five to prioritize drug-like molecules [15].

Pharmacophore Screening:

- Load the validated pharmacophore model and the prepared compound database into screening software (e.g., Catalyst, Phase, or LigandScout).

- Perform a rapid 3D search to identify compounds that match the pharmacophore features within defined spatial tolerances (typically 1.0-1.5 Å). Retrieve the top matching compounds (hits) based on fit score.

Post-Screening Analysis:

- Subject the pharmacophore hits to molecular docking against the ERα structure (e.g., using AutoDock 4.2 [15] [16] or AutoDock Vina) to evaluate binding poses and predict binding affinities.

- Analyze the binding interactions of top-ranked poses to ensure they form key interactions with residues like Glu353 and Arg394 [16].

- Select compounds with favorable docking scores and interaction profiles for in vitro validation in ERα competitor assays (e.g., fluorescence polarization) and luciferase reporter gene assays in MCF-7 cells [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table lists key reagents and computational tools essential for conducting ERα pharmacophore modeling and antagonist discovery.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for ERα Antagonism Research

| Category | Item / Software | Specifications / Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Structures | ERα LBD crystal structure (e.g., PDB: 3ERT) | Structure of ERα bound to 4-hydroxytamoxifen (antagonist); resolution ≤ 2.0 Å [15] [16] | Template for structure-based pharmacophore modeling and molecular docking. |

| Chemical Libraries | NCI Diversity Set / Natural Product Libraries | Collections of structurally diverse, drug-like small molecules for virtual screening [11] [18]. | Source of compounds for pharmacophore-based virtual screening to identify novel hits. |

| Computational Software | Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) | Calculates 186 2D and 148 3D molecular descriptors for QSAR and machine learning [11]. | Generation of molecular descriptors for building predictive machine learning models. |

| Computational Software | Schrödinger Suite (Phase) | Integrated platform for structure-based and ligand-based pharmacophore model generation and screening [14]. | Creation of 3D pharmacophore hypotheses and atom-based 3D-QSAR models. |

| Computational Software | AutoDock 4.2 / AutoDock Vina | Open-source molecular docking tools for predicting ligand binding modes and affinities [15] [16]. | Validation of pharmacophore hits and analysis of protein-ligand interactions. |

| Assay Kits & Reagents | ERα Competitor Assay Kit | Fluorescence-based kit to measure direct binding of test compounds to ERα. | Primary in vitro validation of predicted binders from virtual screening. |

| Cell Lines | MCF-7 Human Breast Cancer Cells | ERα-positive cell line for functional characterization of antagonists [11] [18]. | Luciferase reporter gene assays to confirm antagonistic activity and IC₅₀ determination. |

Defining the ERα antagonist pharmacophore through the integration of structural biology, QSAR, and machine learning provides a powerful blueprint for rational drug design. The core features—hydrophobic groups, hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, and excluded volumes—are critical for high-affinity binding and functional antagonism. The detailed protocols and toolkit provided herein offer a validated roadmap for researchers to apply these models in virtual screening and lead optimization campaigns. This structured approach accelerates the discovery of novel ERα antagonists, potentially overcoming the limitations of current endocrine therapies and addressing the challenge of drug resistance in breast cancer.

Estrogen Receptor Alpha (ERα) is a ligand-inducible nuclear transcription factor and the primary driver of approximately 70% of breast cancers, classified as ER-positive (ER+) breast cancer [19]. Its ligand-binding domain (LBD) serves as a critical regulatory switch, controlling receptor activation, dimerization, and co-regulator recruitment. The ERα LBD is composed of 12 α-helices (H1-H12) and a small β-sheet, arranged in a three-layer helical sandwich fold that is highly conserved among nuclear receptors [20] [21]. Within this architecture, helix 12 (H12) functions as a molecular gatekeeper, determining whether the receptor adopts transcriptionally active or inactive states based on ligand binding and post-translational modifications [8]. The structural plasticity of the ERα LBD, particularly the dynamic behavior of H12, enables its regulation by diverse chemical entities—from endogenous hormones to therapeutic antagonists—making it a paramount target for structure-based drug design in oncology. Understanding its essential structural motifs is fundamental to developing next-generation therapies that overcome endocrine resistance.

Key Structural Motifs and Their Functional Roles

The ERα LBD contains several evolutionarily conserved structural motifs that dictate its signaling output. Table 1 summarizes the key motifs, their locations, and primary functions.

Table 1: Essential Structural Motifs in the ERα Ligand-Binding Domain

| Motif Name | Structural Location | Primary Function | Ligand-Induced Conformational Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Activation Function-2 (AF2) | Primarily H12, with contributions from H3, H4, and H5 | Forms coactivator binding surface for LXXLL motif recognition | Agonists stabilize H12 over AF2; antagonists displace H12 to block AF2 [21] |

| Ligand-Binding Pocket (LBP) | Hydrophobic cavity formed by H3, H5, H6, H7, H8, and H11 | Binds endogenous estrogens, SERMs, SERDs, and other ligands | Determines the positional fate of H12 and subsequent receptor activity [15] |

| Helix 11-Helix 12 Loop | Short loop connecting H11 and H12 | Determines H12 mobility and positional stability | Somatic mutations (Y537S, D538G) shorten loop, stabilizing agonist conformation [20] [8] |

| Hydrophobic Cluster | Buried interface involving H3 (M343, T347), H5 (W383), H11 (L525), and H12 (L536, L540) | Stabilizes the apo conformation of H12 | Ligand binding disrupts cluster, displacing H12 [8] |

| Salt Bridge Network | Between H12 (D538) and H3/K529 (Y537) | Stabilizes apo H12 conformation through π-stacking and ionic interactions | Mutations (D538G) disrupt network, leading to constitutive activity [8] |

| Dimerization Interface | Primarily H10 and H11 | Facilitates ERα homodimerization and DNA binding | Ligand binding enhances dimerization stability [22] |

The Activation Function-2 (AF2) surface is arguably the most critical functional motif, serving as the docking site for LXXLL motifs found in transcriptional coactivators. In the agonist-bound state, H12 adopts a conformation that packs tightly against H3 and H4, completing the AF2 surface and enabling coactivator recruitment. In contrast, selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) like lasofoxifene contain bulky side chains that sterically prevent H12 from adopting the active conformation, instead displacing it to occupy the coactivator binding groove [21]. This molecular antagonism provides the structural basis for SERM activity in breast tissue.

The Helix 11-Helix 12 loop has emerged as a critical regulatory hotspot, with recent structural studies revealing that breast cancer-associated mutations Y537S and D538G fundamentally alter its properties. These mutations shorten and increase the flexibility of the H11-H12 loop, allowing H12 to adopt the active "stable agonist" conformation even in the absence of natural ligand [20]. Biophysical studies using FlAsH-ER assays demonstrate that unliganded Y537S and D538G mutants adopt H12 conformations nearly identical to estradiol-bound wild-type receptors, explaining their constitutive transcriptional activity [20].

Impact of Somatic Mutations on LBD Structure and Dynamics

Acquired mutations in the ESR1 gene encoding ERα are detected in 30-50% of therapy-resistant metastatic ER+ breast cancers and represent a major clinical challenge [19]. These mutations primarily occur at key positions within the H11-H12 loop and adjacent structural elements, fundamentally altering the energy landscape of H12 dynamics. Table 2 quantifies the biophysical and functional consequences of prevalent ESR1 mutations.

Table 2: Biophysical and Functional Impact of Common ESR1 Mutations

| Mutation | Structural Location | Effect on H12 Conformation | Effect on Ligand-Independent Activity | Reported IC₅₀ for E2 (nM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-Type | H11-H12 Loop | Dynamic, ligand-dependent | Baseline | 16.69 ± 4.74 [20] |

| Y537S | H11-H12 Loop | Stabilized agonist conformation | Highly increased | 15.82 ± 3.13 [20] |

| D538G | H11-H12 Loop | Stabilized agonist conformation | Highly increased | 19.78 ± 3.71 [20] |

The Y537S mutation replaces tyrosine with serine at position 537, disrupting a critical π-stacking interaction with Y526 that helps maintain the apo conformation of H12 [8]. Similarly, the D538G mutation eliminates a salt bridge with K529, further destabilizing the inactive state. Molecular dynamics simulations reveal that these mutations lower the energy barrier for H12 transition to the active state, resulting in ligand-independent receptor activation and reduced efficacy of endocrine therapies [20] [8].

Structural analyses indicate that these mutations create a receptor that mimics the agonist-bound conformation, with H12 positioned to facilitate coactivator recruitment even in the absence of estrogen. This structural understanding directly informs the development of next-generation therapeutics that specifically target these mutant receptors, such as complete estrogen receptor antagonists (CERANs) and selective estrogen receptor covalent antagonists (SERCAs) [19].

Experimental Approaches for Analyzing LBD Structure and Dynamics

FlAsH-ER Assay for Monitoring H12 Dynamics

The FlAsH-ER assay provides a robust method for monitoring ligand-dependent and ligand-independent H12 transitions in real-time [20]. This technique utilizes bipartite tetracysteine (C4) display coupled with the biarsenical fluorophore FlAsH-EDT2.

Protocol:

- Engineering C4-tagged ERα-LBD constructs: Introduce C4 motifs (CCPGCC) into specific positions of the ERα-LBD to enable FlAsH binding only when H12 is in extended conformation.

- Site-directed mutagenesis: Generate constitutively active mutants (Y537S, D538G) in C4-tagged background while mutating native cysteine residues (C417, C530) to prevent nonspecific labeling.

- Protein purification: Express and purify ERα-LBD mutants using standard chromatographic techniques.

- Fluorescence labeling: Incubate ERα-LBD constructs (1-10 μM) with FlAsH-EDT2 (0.1-1 μM) in presence or absence of ligand (e.g., 17β-estradiol, 100 nM).

- Fluorescence measurement: Monitor fluorescence emission at 528 nm (excitation 508 nm) over time or as endpoint measurements.

- Data analysis: Compare fluorescence intensities between unliganded and liganded states, with decreased fluorescence indicating H12 folding into stable agonist conformation.

Applications: This assay demonstrated that unliganded Y537S and D538G mutants exhibit fluorescence intensities comparable to liganded wild-type ERα, confirming their tendency to adopt stable agonist conformations without ligand [20].

Computational Approaches for Pharmacophore Modeling

Structure-based pharmacophore modeling identifies essential chemical features responsible for effective ERα binding and can guide the design of novel ligands.

Protocol:

- Protein preparation: Obtain ERα-LBD structure from PDB (e.g., 3ERT for tamoxifen-bound form). Remove bound ligand, add hydrogens, and optimize hydrogen bonding.

- Active site analysis: Define the binding pocket around the cognate ligand, identifying key residues (Leu346, Thr347, Leu349, Ala350, Glu353, Leu387, Met388, Leu391, Arg394, Met421, Leu525) that contribute to binding [15].

- Pharmacophore feature generation: Extract chemical features including:

- Hydrogen bond donors/acceptors

- Hydrophobic regions

- Aromatic rings

- Positive ionizable areas

- Model validation: Test pharmacophore model against known active and inactive compounds to determine screening efficiency.

- Virtual screening: Apply validated model to compound libraries to identify potential novel binders.

Applications: This approach successfully identified ChalcEA derivatives with improved binding affinity over the parent compound, demonstrating the utility of computational methods in ERα inhibitor development [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for ERα LBD Structural and Functional Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| ERα Expression Constructs | ERα-LBD-ΔC4, ERα-LBD-ΔC4(Y537S), ERα-LBD-ΔC4(D538G) | FlAsH-ER assays, biophysical studies | C4 tags for FlAsH binding; cysteine-to-alanine mutations to prevent nonspecific labeling [20] |

| Fluorescent Probes | FlAsH-EDT₂ | H12 conformational monitoring | Binds bipartite tetracysteine motifs; fluorescence increases with H12 extension [20] |

| Reference Ligands | 17β-estradiol (E2), 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT), lasofoxifene | Control conditions, conformational standards | E2: full agonist; 4-OHT: SERM; lasofoxifene: SERM with defined crystal structure [15] [21] |

| Cell-Based Reporter Systems | T47D-KBluc (ERE-luciferase) | Functional activity screening | Endogenously expresses ERα and ERβ; responsive to estrogenic compounds [23] |

| Dimerization Assay Systems | BRET (Bioluminescence Resonance Energy Transfer) | Live-cell dimerization monitoring | Quantifies ERα/α, ERβ/β, and ERα/β dimer formation in response to ligands [23] |

Visualizing Structural Transitions and Experimental Workflows

ERα LBD Conformational States and Transitions

Experimental Workflow for ERα LBD Analysis

The essential structural motifs of the ERα LBD—particularly the dynamic Helix 12, AF2 surface, and H11-H12 loop—constitute a sophisticated molecular switch governing receptor function. The precise characterization of these motifs provides critical insights for drug discovery, especially in addressing the challenge of treatment-resistant ESR1 mutations. Contemporary research leverages integrated structural biology approaches, combining FlAsH-ER assays, X-ray crystallography, hydrogen-deuterium exchange mass spectrometry (HDX-MS), and computational modeling to elucidate the conformational landscapes of both wild-type and mutant receptors.

These foundational insights directly enable structure-guided drug design against endocrine-resistant breast cancers. Next-generation therapeutic platforms—including SERDs, complete estrogen receptor antagonists (CERANs) like OP-1250, and proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs) like ARV-471—are being developed to specifically target the active conformations stabilized by Y537S and D538G mutations [19]. Furthermore, emerging strategies such as eIF4A inhibition to disrupt ER translation offer complementary approaches to directly targeting the receptor protein itself [24]. As structural characterization techniques advance, particularly in capturing transient conformational states, the continued elucidation of ERα LBD structural motifs will undoubtedly yield novel therapeutic strategies for overcoming endocrine resistance in breast cancer.

Within the framework of pharmacophore modeling research for Estrogen Receptor Alpha (ERα) inhibitors, understanding the template provided by established drugs is paramount. Tamoxifen, and its active metabolite 4-Hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT), represent cornerstone selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) therapies for hormone receptor-positive breast cancer [15] [25]. Their efficacy stems from the ability to bind to ERα and exert an antagonistic effect in breast tissue, thereby inhibiting cancer cell proliferation [15]. This application note delineates the critical pharmacophore features of Tamoxifen and 4-OHT, providing a structured reference for the design and evaluation of novel ERα inhibitors. By abstracting their key steric and electronic characteristics into a defined model, researchers can accelerate the virtual screening and rational design of next-generation therapeutics with improved potency and reduced side-effect profiles [26] [27].

Pharmacophore Feature Analysis of 4-OHT

The molecular recognition of 4-OHT by the ERα ligand-binding domain (LBD) is governed by a specific ensemble of steric and electronic features. Analysis of the crystallographic complex (PDB: 3ERT) reveals a defined pharmacophore model essential for its antagonist activity [15] [28].

Table 1: Key Pharmacophore Features of 4-OHT in the ERα Binding Pocket

| Feature Type | Structural Origin on 4-OHT | Role in Molecular Recognition & Bioactivity |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrophobic Groups | Aromatic rings and the butenyl side chain | Form van der Waals interactions with hydrophobic residues (e.g., Leu346, Leu349, Ala350, Leu387, Leu391) in the largely hydrophobic LBD [15]. |

| Hydrogen Bond Acceptor | Phenolic oxygen atom | Acts as a critical hydrogen bond acceptor with the key residue Glu353 [15] [28]. |

| Hydrogen Bond Donor | Hydroxyl group on the phenolic ring | Serves as a hydrogen bond donor to the backbone carbonyl of His524 [15]. |

| Positive Ionizable Group | Tertiary amine nitrogen atom | The basic amine, often protonated, can form a salt bridge or charge-assisted hydrogen bond with the carboxylate group of Asp351 [15]. |

The spatial arrangement of these features forces a conformational change in ERα, particularly the displacement of Helix-12. This repositioning occludes the coactivator binding site, shifting the receptor's pharmacology from agonist to antagonist mode, which is crucial for its anti-proliferative effect in breast cancer [15].

Experimental Protocols for Pharmacophore Modeling

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling Protocol

This protocol details the generation of a structure-based pharmacophore model using a protein-ligand complex, such as ERα with 4-OHT (PDB: 3ERT).

Step 1: Protein Preparation

- Obtain the 3D structure of the ERα-4-OHT complex from the Protein Data Bank (PDB ID: 3ERT) [26].

- Prepare the protein structure by adding hydrogen atoms, correcting protonation states of residues (e.g., Glu353, Asp351), and optimizing hydrogen bonding networks using software like LigandScout or Discovery Studio [26].

- Resolve any missing side chains or loops using homology modeling tools if necessary.

Step 2: Binding Site Analysis

- Define the ligand-binding site based on the coordinates of the crystallized 4-OHT ligand.

- Analyze the protein-ligand interaction pattern to identify key amino acid residues involved in hydrophobic contacts, hydrogen bonding, and ionic interactions [26].

Step 3: Pharmacophore Feature Generation

- Use the prepared complex to automatically or manually map pharmacophore features.

- Hydrogen Bond Donor/Acceptor: Derive from interactions like the 4-OHT hydroxyl with His524 and the phenolic oxygen with Glu353 [15] [28].

- Hydrophobic Features: Map from the contacts between the aromatic rings of 4-OHT and hydrophobic residues like Leu387 and Leu391 [15].

- Positive Ionizable Feature: Assign based on the interaction between the tertiary amine of 4-OHT and Asp351 [15].

- Incorporate exclusion volumes to represent the spatial constraints of the binding pocket, preventing steric clashes [26].

Step 4: Model Validation

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling Protocol

This protocol is used when the 3D structure of the target protein is unavailable, and a model is built from a set of known active ligands.

Step 1: Training Set Selection

- Compile a structurally diverse set of molecules with confirmed ERα antagonist activity, including Tamoxifen, 4-OHT, and other known inhibitors.

- Include confirmed inactive compounds to enhance model selectivity, if available.

Step 2: Conformational Analysis

- For each molecule in the training set, generate a representative ensemble of low-energy conformations using molecular mechanics or molecular dynamics methods [29].

Step 3: Molecular Superimposition

- Superimpose the multiple low-energy conformations of all active training set molecules.

- Identify and align common functional groups (e.g., aromatic rings, hydrogen bond acceptors/donors, basic amines) to find the best consensus fit [29].

Step 4: Pharmacophore Abstraction and Hypothesis Generation

- Abstract the aligned functional groups into pharmacophore features (e.g., H-bond acceptor, hydrophobic area, positive ionizable).

- Define the relative spatial 3D arrangement and distance tolerances between these features to create the pharmacophore hypothesis [29].

Step 5: Model Validation and Refinement

- Test the hypothesis by screening a database of compounds and evaluating its predictive power for identifying active molecules.

- Refine the model iteratively based on validation results and new biological data [29].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for ERα Pharmacophore Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Crystallographic Structure | Provides atomic-level details of the ligand-receptor complex for structure-based modeling. | ERα-4-OHT Complex (PDB: 3ERT). Resolution: 1.9 Å. Serves as the foundational template [15]. |

| Reference Ligands | Serve as training sets for ligand-based modeling and as controls in experimental validation. | Tamoxifen, 4-Hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT), Endoxifen. Source: Commercial suppliers (e.g., Sigma-Aldrich) [15] [25]. |

| Pharmacophore Modeling Software | Used to build, visualize, and validate pharmacophore models. | LigandScout: For structure- and ligand-based modeling [15]. Phase: For ligand-based QSAR pharmacophore development [27]. |

| Molecular Docking Software | Evaluates binding poses and predicts affinity of novel compounds. | AutoDock 4.2/ Vina. Validated docking protocols for ERα are established [15] [30]. |

| Cell-Based Assay System | For experimental validation of antagonist activity and potency. | MCF-7 Cell Line. ERα-positive human breast cancer cells used to measure proliferation inhibition (IC₅₀) [15] [31]. |

Workflow Integration in Drug Discovery

The following diagram illustrates how pharmacophore modeling of established inhibitors like 4-OHT integrates into a broader drug discovery workflow for novel ERα antagonists.

This workflow demonstrates the iterative cycle from template analysis and model generation through to virtual screening, lead optimization, and experimental validation, providing a rational path for discovering novel ERα inhibitors [15] [26] [32].

The pursuit of novel estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) inhibitors is a central focus in breast cancer research. Contemporary drug discovery, particularly pharmacophore modeling, benefits from an unexpected source: the evolutionary and structural conservation between human ERα and prokaryotic taxis receptors. Emerging evidence suggests that the ligand-binding domain (LBD) of ERα shares a remarkably conserved structural architecture with bacterial chemotaxis receptors, despite significant sequence divergence [33]. This conservation suggests a potential for convergent molecular evolution, where unrelated proteins independently develop similar structural solutions to the problem of environmental sensing [33]. This application note details the experimental and computational protocols that leverage this evolutionary insight, providing researchers with a framework to enhance ERα inhibitor discovery through structural analysis of bacterial homologs, advanced pharmacophore modeling, and innovative delivery systems inspired by bacterial mechanisms.

Structural and Functional Conservation Between Taxis Receptors and ERα

Evidence of Conserved Structural Architecture

Comparative bioinformatics analyses reveal that the structural similarity between bacterial taxis receptors and ERα is a conserved architectural feature, not a sequence-based homology.

Table 1: Key Evidence for Structural Conservation Between Bacterial Taxis Receptors and ERα

| Evidence Type | Description | Implication for ERα Research |

|---|---|---|

| Domain Architecture | High conservation in domain structural fold architecture between ERα-LBD and bacterial taxis receptor LBDs, despite <30% sequence similarity [33]. | Suggests deep functional conservation; ERα's ligand-binding core is an evolutionarily optimized scaffold. |

| Structural Alignment | TM-align analysis shows significant structural superposition between human ERα-LBD and the LBD of E. coli Tsr taxis receptor [33]. | Provides a structural template for understanding ERα's promiscuity toward diverse ligands. |

| Pharmacophore Features | Ligands for ER and bacterial chemotaxis receptors share common pharmacophore features, and cross-interaction is observed in docking studies [33]. | Indicates that bacterial receptor ligands can serve as a source of novel chemical scaffolds for ERα inhibition. |

| Phylogenetic Analysis | Unrooted gene trees cluster ERα separately from bacterial receptors, confirming independent evolution (convergence) rather than shared ancestry [33]. | Highlights the functional importance of the conserved fold for sensing tasks across biological kingdoms. |

Experimental Protocol: Establishing Structural Conservation

Objective: To identify and validate structural similarities between bacterial taxis receptors and ERα.

Materials & Reagents:

- Protein Structures: PDB files for ERα (e.g., 3ERT) and bacterial taxis receptors (e.g., E. coli Tsr, P. putida broad ligand chemoreceptor).

- Software: COBALT for multiple sequence alignment, TM-align for structure alignment, MEGA X for phylogenetic analysis.

Procedure:

- Data Retrieval: Download amino acid sequences and structural files for the LBDs of ERα and selected bacterial taxis receptors from NCBI and the RCSB Protein Data Bank.

- Sequence Alignment: Perform a Constraint-Based Multiple Protein Alignment Tool (COBALT) analysis. This tool integrates pairwise constraints from conserved domain databases and is more sensitive for detecting distant relationships than standard BLAST [33].

- Structural Superposition: Use TM-align to perform sequence-independent structural alignment of the ERα-LBD with the LBDs of bacterial taxis receptors. Calculate Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD) of the aligned residues to quantify structural similarity.

- Phylogenetic Analysis: Construct an unrooted phylogenetic tree using Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) version X to confirm the independent evolutionary origin of the proteins despite structural similarities.

Interpretation: A high degree of structural conservation (low RMSD in TM-align) coupled with a lack of sequence similarity and separate phylogenetic clustering provides strong evidence for convergent evolution at the structural level.

Figure 1: Workflow for establishing structural conservation between bacterial taxis receptors and ERα. The parallel alignment steps highlight the dual evidence of sequence divergence and structural similarity.

Application in ERα Pharmacophore Modeling and Drug Delivery

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents and Computational Tools for Cross-Species ERα Research

| Item/Category | Function/Description | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial AB5 Toxins (e.g., CTB) | Non-toxic B-subunit pentamer that binds to GM1 receptors on mucosal cells and the blood-brain barrier [34]. | Serves as a "taxi" platform for needle-free vaccine and drug delivery; can be repurposed for targeted CNS delivery of therapeutic agents. |

| Computational Docking Software (AutoDock 4.2/Glide) | Programs to model atomic-level interaction between a small molecule (ligand) and a protein (receptor) [15] [35]. | Used to predict binding affinity and poses of novel inhibitors within the ERα ligand-binding domain. |

| 3D Pharmacophore Modeling (LigandScout) | Derives key interaction features (H-bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobics) from active ligands or protein-ligand complexes [15] [35] [17]. | Creates a predictive model for virtual screening of compound databases to identify novel ERα inhibitor scaffolds. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation (e.g., GROMACS) | Simulates physical movements of atoms and molecules over time to assess complex stability [35] [17]. | Validates stability of predicted ERα-inhibitor complexes from docking and provides binding free energy estimates (e.g., via MMPBSA). |

| PAS-domain MCPs (from Magnetospirillum) | Bacterial receptors sensing oxygen via a flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) cofactor [36]. | Model systems for understanding the structural basis of small molecule sensing, informing ERα ligand binding studies. |

Experimental Protocol: Pharmacophore Modeling and Virtual Screening

Objective: To develop a structure-based pharmacophore model for ERα and use it to screen for novel inhibitors, potentially informed by ligands of bacterial taxis receptors.

Materials & Reagents:

- Software: LigandScout, Molecular docking software (AutoDock 4.2 or Glide), MD simulation software.

- Structural Data: X-ray crystal structure of ERα LBD (PDB: 3ERT).

- Compound Libraries: Database of commercially or synthetically available compounds for virtual screening.

Procedure:

- Structure Preparation: Obtain the ERα structure (3ERT). Remove the native ligand (4-hydroxytamoxifen) and all water molecules. Add hydrogen atoms and optimize the protein structure for docking and pharmacophore generation.

- Pharmacophore Model Generation: Using LigandScout, generate a structure-based pharmacophore model from the prepared ERα structure and the bound ligand. The model will identify key features like hydrogen bond acceptors/donors, hydrophobic regions, and aromatic interactions [35] [17].

- Model Validation: Validate the model by screening a dataset of known active compounds and decoys. A robust model will efficiently retrieve active compounds (good yield) and reject decoys.

- Virtual Screening: Use the validated pharmacophore model as a 3D query to screen large electronic compound databases. Retrieve compounds that match the critical pharmacophore features.

- Molecular Docking: Perform molecular docking (e.g., using AutoDock 4.2 or Glide) of the hit compounds from the virtual screening into the ERα binding site. This refines the pose prediction and provides an estimated binding affinity [15] [35].

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation: Subject the top-ranked ERα-inhibitor complexes from docking to MD simulations (e.g., 100-200 ns) to evaluate the stability of the binding interactions and calculate binding free energies using methods like MMPBSA [35] [17].

Interpretation: Compounds that successfully pass the pharmacophore screen, show favorable docking scores, and form stable complexes in MD simulations with a calculated strong binding affinity (e.g., ΔGTotal ~ -48 kcal/mol, as seen for a promising glycine-conjugated α-mangostin [17]) are strong candidates for experimental validation.

Experimental Protocol: Utilizing Bacterial Toxin Platforms for Delivery

Objective: To design a needle-free delivery system for an ERα vaccine or therapeutic using the B5 subunit of bacterial AB5 toxins.

Materials & Reagents:

- Platform: Recombinant B5 subunit of Cholera Toxin (CTB).

- Antigen/Therapeutic: ERα-specific antigen or inhibitor molecule.

- Expression System: Suitable bacterial or plant-based system for producing the CTB-antigen fusion protein.

Procedure:

- Genetic Engineering: Using genetic engineering techniques, remove the gene for the toxic A subunit and replace it with the gene for the chosen ERα-specific antigen [34].

- Protein Production & Purification: Express the resulting fusion protein in a suitable host (e.g., E. coli or even lettuce cells for oral delivery [34]). Purify the assembled holotoxin-like structure.

- Formulation: Formulate the purified protein for needle-free administration. This could involve stabilization in a sugar capsule for oral ingestion, incorporation into a skin patch, or preparation as a nasal spray [34].

- Testing: Administer the formulation to a model organism (e.g., mice or cows [34]) and monitor for the development of a targeted immune response or therapeutic effect, assessing both barrier (mucosal) and systemic immunity.

Interpretation: A positive immune response or therapeutic effect following needle-free administration demonstrates successful harnessing of the bacterial toxin's entry mechanism for targeted delivery, potentially leading to improved patient compliance and novel treatment modalities.

Figure 2: Utilizing bacterial AB5 toxins as a delivery platform for ERα-targeted therapies. The platform leverages the natural cell-entry function of the toxin's B-subunit for needle-free administration.

Practical Guide to Structure-Based and Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

Estrogen Receptor Alpha (ERα) is a primary driver in the majority of breast cancers, making it a critical target for therapeutic intervention [15] [8]. Structure-based modeling provides an essential foundation for understanding the molecular interactions between ERα and its ligands, enabling the rational design of novel inhibitors. The crystal structure of the human ERα ligand-binding domain (LBD) in complex with the antagonist 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT) (PDB ID: 3ERT), determined at 1.90 Å resolution, serves as a cornerstone for these efforts [37]. This structure reveals the precise atomic-level details of how antagonists block coactivator binding by inducing a characteristic "autoinhibitory" conformation in helix 12 (H12) of the receptor, a mechanism distinct from that of agonists [37] [21]. This application note details the protocols for deriving pharmacophore features and conducting docking analyses based on the 3ERT structure, providing a framework for the identification and optimization of novel ERα inhibitors within a broader pharmacophore modeling research context.

Structural Basis of ERα Antagonism

The ERα LBD adopts a three-layer helical sandwich fold, with the ligand-binding pocket (LBP) housed within its interior [21]. The conformational state of the C-terminal Helix 12 (H12) is the critical determinant of agonist versus antagonist activity.

- Agonist Mechanism: Agonists (e.g., estradiol) stabilize H12 in a conformation that docks against the LBD, forming a contiguous groove with helices 3, 4, and 5. This creates the activation function-2 (AF-2) surface, which is essential for the recruitment of LXXLL motif-containing coactivator proteins like SRC-1 and GRIP1 [21] [8].

- Antagonist Mechanism: As revealed by the 3ERT structure, antagonists like 4-OHT possess a bulky pendant side chain that sterically clashes with the agonist-position of H12. This displaces H12, causing it to occlude the coactivator-binding groove. This "autoinhibitory" conformation prevents coactivator recruitment and thereby blocks transcriptional activation [37] [21].

The 4-OHT ligand in the 3ERT structure is anchored by a key hydrogen-bonding network between its phenolic hydroxyl group and the side chains of Glu353 and Arg394 residues within the LBP [37] [15]. The extended dimethylaminoethoxy side chain projects toward the base of H12, facilitating its displacement.

Quantitative Data from ERα-Ligand Complexes

The table below summarizes key structural parameters and ligand interactions from representative ERα-ligand co-crystal structures, providing a quantitative basis for comparative analysis.

Table 1: Key Structural and Energetic Parameters of ERα-Ligand Complexes

| PDB ID | Ligand | Ligand Type | Resolution (Å) | Key Interacting Residues | Reported Binding Energy (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3ERT [37] | 4-Hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT) | Antagonist (SERM) | 1.90 | Glu353, Arg394, Asp351, Leu387, Leu391 | -11.04 [15] |

| N/A [15] | HNS10 (ChalcEA derivative) | Antagonist | N/A (Docking) | Leu346, Thr347, Glu353, Leu387, Arg394, Leu525 | -12.33 [15] |

| N/A [17] | Am1Gly (α-Mangostin conjugate) | Antagonist | N/A (Docking/MD) | Glu353, Arg394, etc. | -10.91 (Docking), -48.79 (MM/PBSA) [17] |

| 9D8Q [8] | Estradiol (E2) | Agonist | 2.00 (rfERα) | Glu353, Arg394, His524, Leu525 | N/A |

These quantitative metrics are vital for validating computational models and setting benchmarks for the design of new ligands with improved affinity and specificity.

Application Notes & Protocols

Protocol 1: Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling from 3ERT

This protocol details the generation of a structure-based pharmacophore model using the 3ERT complex to identify key interaction features for antagonist design.

Software: LigandScout 4.1 Advanced or equivalent [15].

Methodology:

- Protein and Ligand Preparation:

- Obtain the 3ERT structure from the Protein Data Bank (https://www.rcsb.org) [37].

- Isolate the 4-OHT ligand and the ERα LBD chain. Add hydrogen atoms and assign correct protonation states at physiological pH (e.g., Glu353 and Asp351 are deprotonated; Arg394 is protonated).

- Interaction Feature Identification:

- Automatically or manually map the interaction features between 4-OHT and the ERα LBD binding pocket. The key features derived from 3ERT typically include [15] [17]:

- Hydrogen Bond Donor/Acceptor: Corresponding to the phenolic oxygen of 4-OHT interacting with Glu353 and Arg394.

- Hydrophobic Features: Representing the aromatic rings and the ethyl group of the dimethylaminoethoxy side chain, interacting with hydrophobic residues like Leu387, Leu391, and Leu349.

- Positive Ionizable Feature: Representing the tertiary amine of the dimethylaminoethoxy side chain.

- Automatically or manually map the interaction features between 4-OHT and the ERα LBD binding pocket. The key features derived from 3ERT typically include [15] [17]:

- Pharmacophore Model Generation:

- Export the spatial arrangement of these chemical features, including their geometries (vectors, planes) and tolerances, to create the 3D pharmacophore model.

- Model Validation:

Protocol 2: Molecular Docking of Novel Ligands into the ERα LBD

This protocol validates the binding pose and affinity of novel potential ERα ligands using molecular docking simulations with the 3ERT structure as the receptor.

Software: AutoDock 4.2, AutoDock Vina, or similar molecular docking suites [15] [17].

Methodology:

- System Preparation:

- Receptor Preparation: Use the 3ERT structure. Remove water molecules and the native 4-OHT ligand. Add polar hydrogen atoms and Kollman charges, then save in PDBQT format [17].

- Ligand Preparation: Sketch or obtain the 3D structure of the test ligand. Perform energy minimization, add Gasteiger charges, and define rotatable bonds. Save in PDBQT format [17].

- Grid Box Definition:

- Define a grid box large enough to encompass the entire LBP. A typical box size of 40 × 40 × 40 Å centered on the coordinates of the native ligand (e.g., x=30.010, y=-1.913, z=24.207 for 3ERT) is recommended [17].

- Docking Simulation:

- Run the docking algorithm (e.g., Lamarckian Genetic Algorithm in AutoDock) with a sufficient number of runs (e.g., 100) to ensure comprehensive sampling [17].

- Pose Analysis and Validation:

- Pose Validation: Validate the docking protocol by re-docking the native 4-OHT ligand and calculating the Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) between the docked pose and the crystallographic pose. An RMSD of <2.0 Å is generally acceptable, with the study on ChalcEA derivatives achieving an RMSD of 0.893 Å [15].

- Analysis of Docked Complexes: Analyze the top-ranked poses of novel ligands for key interactions with residues such as Glu353, Arg394, and Asp351, and check if the ligand induces the characteristic antagonist conformation by potentially sterically clashing with Leu540/L536 [37] [8].

Figure 1: Workflow for structure-based pharmacophore modeling and docking using ERα co-crystals.

Visualizing the Structural Mechanism of Antagonism

The following diagram illustrates the critical conformational change in Helix 12 induced by antagonist binding, as revealed by the 3ERT structure, and the key ligand-receptor interactions.

Figure 2: Structural mechanism of ERα antagonism by 4-OHT (3ERT).

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for ERα Structure-Based Modeling

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Description | Example Use in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| PDB ID 3ERT [37] | The atomic coordinates of the ERα LBD/4-OHT complex. | Serves as the primary structural template for pharmacophore modeling and docking. |

| Structure-Based Pharmacophore Software (e.g., LigandScout) [15] | Software to automatically or manually derive pharmacophore features from a protein-ligand complex. | Used in Protocol 1 to identify key H-bond donors/acceptors and hydrophobic features from 3ERT. |

| Molecular Docking Suite (e.g., AutoDock 4.2, AutoDock Vina) [15] [17] | Software to predict the bound conformation and binding affinity of a small molecule to a protein target. | Used in Protocol 2 to pose and score novel ligands within the ERα LBD from 3ERT. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation Software (e.g., GROMACS, AMBER) [17] | Software to simulate the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time, assessing complex stability. | Used for advanced validation of binding poses and calculating free energy of binding (MM/PBSA) [17]. |

| ERα LBD Expression System (E. coli) [37] | Heterologous expression system for producing the human ERα ligand-binding domain for biochemical and structural studies. | Used to generate the protein for the original 3ERT crystallography study [37]. |

The discovery of novel Estrogen Receptor Alpha (ERα) inhibitors is a critical frontier in the fight against hormone-dependent breast cancer. With resistance to existing therapies like tamoxifen representing a major clinical challenge, the efficient identification of new lead compounds is paramount [39] [40] [41]. This application note details a robust computational workflow that integrates pharmacophore modeling and virtual screening to accelerate the early-stage discovery of potent ERα inhibitors. By leveraging both the structural knowledge of the receptor and the chemical intuition from known active compounds, this protocol provides a powerful, cost-effective strategy for identifying and optimizing novel therapeutic candidates with improved pharmacological profiles [26].

The core of this methodology lies in its synergistic use of structure-based and ligand-based drug design approaches. Structure-based methods derive essential interaction features directly from the 3D architecture of the ERα ligand-binding domain (LBD), while ligand-based methods distill the common chemical characteristics of known active molecules [26]. This integrated framework ensures that generated pharmacophore models are both mechanistically grounded and informed by experimental structure-activity relationships, creating a solid foundation for the subsequent virtual screening of large compound libraries.

Integrated Workflow for Pharmacophore Modeling and Virtual Screening

The following workflow delineates a sequential protocol for identifying novel ERα inhibitors, from initial model generation through the prioritization of hit compounds. This integrated pathway is designed to maximize the identification of biologically relevant candidates while conserving computational resources.

- Node 1: Data Collection and Preparation. The workflow begins with the retrieval of a high-quality ERα structure, typically from the Protein Data Bank (e.g., PDB ID: 3ERT or 8AWG) [42] [41]. Critical preparation steps include adding hydrogen atoms, assigning correct protonation states to residues (e.g., Glu353, Arg394), and performing energy minimization to ensure a chemically sensible and stable structure [26] [16].

- Node 2 & 3: Pharmacophore Model Generation. Two parallel paths converge to create a consensus model. The structure-based approach analyzes the ERα binding pocket to define a set of chemical features—such as Hydrogen Bond Acceptors (HBA), Hydrogen Bond Donors (HBD), and Hydrophobic (H) regions—that are critical for ligand binding [26] [16]. Concurrently, the ligand-based approach distills the essential shared features from a set of known active ERα inhibitors (e.g., 4-OHT, raloxifene) [43] [35].

- Node 4: Virtual Screening and Filtering. The validated hybrid pharmacophore model serves as a 3D query to rapidly screen millions of compounds from digital libraries (e.g., ZINC, ChEMBL). Molecules that match the pharmacophore features are subsequently filtered for drug-like properties based on Lipinski's Rule of Five to improve the likelihood of favorable oral bioavailability [39] [16].

- Node 5 & 6: Binding Affinity and Stability Validation. The top-ranking compounds undergo rigorous molecular docking to predict their binding pose and affinity within the ERα binding site [35] [16]. The most promising candidates are then subjected to molecular dynamics (MD) simulations (typically 100-200 ns) to evaluate the stability of the protein-ligand complex in a simulated physiological environment. The binding free energy is calculated using methods like MM/GBSA or MM/PBSA to provide a quantitative estimate of binding strength [39] [43] [40].

Experimental Protocols

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

This protocol generates a pharmacophore model based on the 3D structure of the ERα ligand-binding domain.

Protein Preparation:

- Obtain the ERα crystal structure (e.g., PDB: 3ERT).

- Using a molecular visualization tool (e.g., DS Visualizer, Maestro), remove all water molecules, co-crystallized solvents, and original ligands.

- Add hydrogen atoms and assign partial charges using a suitable force field (e.g., CHARMm).

- Perform energy minimization to relieve any steric clashes or structural strains [41].

Binding Site Analysis:

- Define the binding site centroid using the coordinates of the native co-crystallized ligand.

- Set a cavity radius of approximately 10-15 Å to encompass all key interacting residues [41].

- Identify critical amino acids for interaction, notably Glu353 and Arg394 for hydrogen bonding, and Phe404 for π-π stacking interactions [35] [16].

Feature Generation:

- Use software like LigandScout or MOE to map interaction points within the defined binding cavity.

- Generate pharmacophore features that are complementary to the protein's binding site, including:

- Add exclusion volumes to represent steric constraints of the binding pocket, preventing clashes in generated molecules [26].

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

This protocol is used when the protein structure is unavailable, but a set of active ligands is known.

Ligand Dataset Curation:

- Compile a structurally diverse set of known ERα inhibitors (e.g., 10-50 compounds) with their corresponding experimental bioactivity data (e.g., IC50, Ki).

- Ensure the dataset encompasses a range of potencies to aid in identifying features correlated with high activity.

Conformational Analysis and Alignment:

Hypothesis Generation and Validation:

- Use software like Catalyst or Phase to create a common pharmacophore hypothesis that accounts for the shared features of the active compounds.

- Validate the model by assessing its ability to correctly rank active molecules over inactive (decoy) molecules. A good model will have a high Güner-Henry (GH) score (>0.7), indicating strong predictive power [35] [44].

Integrated Virtual Screening Protocol

Pharmacophore-Based Screening:

- Use the validated pharmacophore model (from sections 3.1 or 3.2) as a 3D query to screen a multi-million compound library (e.g., ZINC15, Enamine).

- Use software like UNITY or Phase to retrieve compounds that fit the spatial and chemical constraints of the model.

- Output a hit list of compounds that match all critical features of the pharmacophore.

Molecular Docking:

- Prepare the hit compounds from the previous step by generating 3D structures and optimizing their geometry using force fields (e.g., MMFF94).

- Perform molecular docking using programs like Glide (SP then XP modes), AutoDock Vina, or GOLD.

- Analyze the binding poses of the top-ranking compounds to ensure they form key interactions with ERα residues (Glu353, Arg394, His524, Phe404) [35] [16].

- Apply a binding affinity threshold (e.g., Glide XP docking score < -9.0 kcal/mol) to filter for the most promising candidates [35].

Binding Free Energy Calculations:

- For the final shortlist of compounds, run MD simulations (e.g., 100-200 ns using AMBER or GROMACS) to assess complex stability (RMSD < 2.0 Å).

- Use the MM/GBSA or MM/PBSA method on a set of stable trajectory frames to calculate the binding free energy.

- Compare the ΔG values of new hits to a reference drug (e.g., 4-OHT, ΔG ~ -53 kcal/mol) to gauge relative potency [43] [16].

Case Studies and Data Analysis

Case Study: Pyrazoline Benzenesulfonamide Derivatives

A recent study designed novel Pyrazoline Benzenesulfonamide Derivatives (PBDs) as ERα antagonists [16]. The workflow involved structure-based design, followed by docking and dynamics simulations.

Table 1: Binding Analysis of Selected PBD Compounds against ERα [16]

| Compound | Docking Score (ΔG, kcal/mol) | MM/PBSA Binding Energy (kJ/mol) | Key Interacting Residues |

|---|---|---|---|

| PBD-17 | -11.21 | -58.23 | ARG394, GLU353, LEU387 |

| PBD-20 | -11.15 | -139.46 | ARG394, GLU353, LEU387 |

| 4-OHT (Ref) | - | -145.31 | GLU353, ARG394, HIS524 |

The data shows that PBD-20 exhibited a binding free energy comparable to the reference drug 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT), suggesting it as a highly promising lead candidate. Pharmacophore screening further confirmed that both PBD-17 and PBD-20 aligned well with the generated model, each achieving a high match score of 45.20 [16].

Case Study: AI-Driven Generation of ERα Inhibitors

A novel AI-based generative framework was employed to design new drug-like molecules for ERα by balancing pharmacophore similarity to reference drugs with structural diversity [42]. The model's reward function integrated Quantitative Estimate of Drug-likeness (QED) with pharmacophore and structural similarity metrics.

Table 2: Performance of AI-Generated Molecules with Different Reward Functions [42]

| Setup | Pharmacophore Similarity (Cosine, ↑) | Structural Similarity (Tanimoto, ↓) | QED (↑) | Docking Score (↓) | Synthetic Accessibility (SA, ↓) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 0.58 | 0.34 | 0.30 | -8.64 | 6.28 |

| Setup 2 | 0.83 | 0.36 | 0.59 | -6.71 | 4.72 |

| Setup 4 | 0.87 | 0.35 | 0.34 | -6.47 | 4.61 |

Key: ↑ Higher is better; ↓ Lower is better.

The results demonstrate that integrating pharmacophore guidance (Setups 2 & 4) successfully improved drug-likeness (QED) and synthetic accessibility (SA) compared to the baseline. While the docking scores were less favorable, the generated molecules maintained high pharmacophoric fidelity and novelty (84.5-100%), highlighting the AI's ability to produce patentable chemical matter with a high potential for biological activity [42].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item / Software | Type | Primary Function in Workflow | Example Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| ERα Protein Structure | Protein Data | Template for structure-based design | PDB IDs: 3ERT, 8AWG [42] [41] |

| Known Active Ligands | Chemical Data | Training set for ligand-based modeling | ChEMBL, PubChem BioAssay [35] |

| Compound Libraries | Chemical Data | Source of candidates for virtual screening | ZINC, Enamine, SPECS, Natural Product DBs [39] [41] |

| LigandScout | Software | Structure- & ligand-based pharmacophore modeling | Inte:Ligand [16] |