Optimizing QSAR Training and Test Sets: A Practical Guide for Robust Model Development

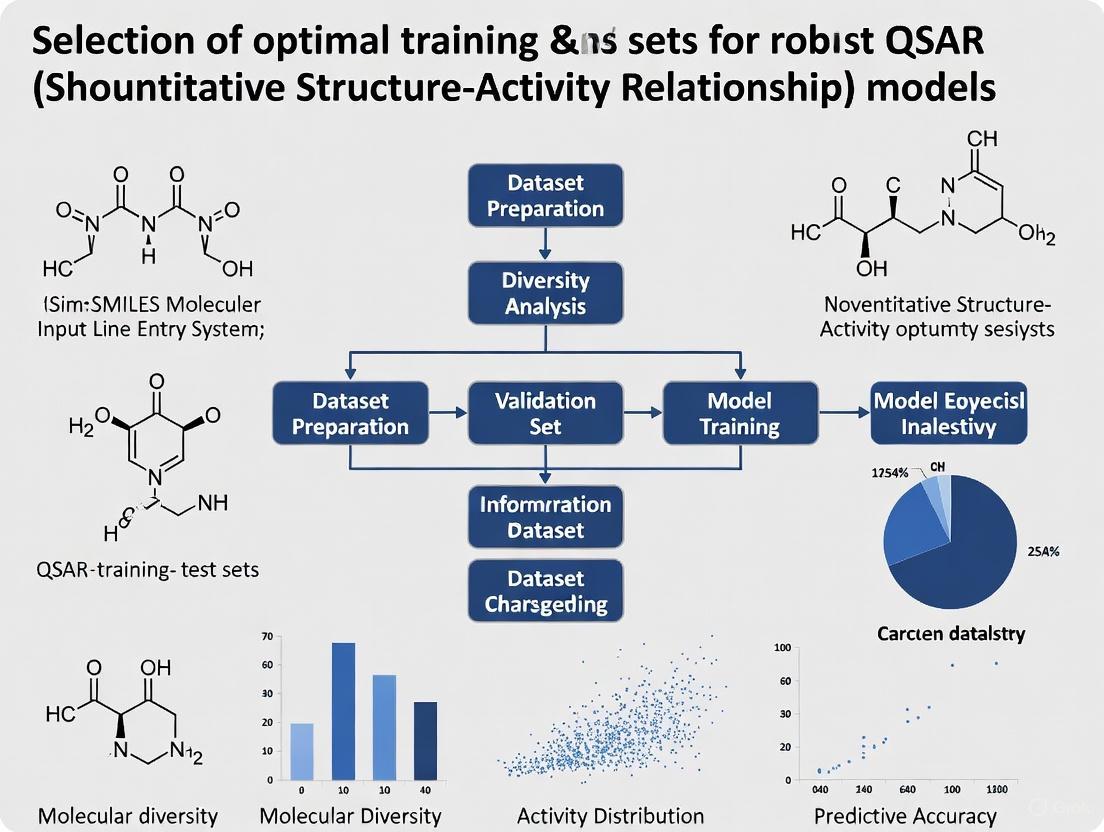

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on selecting optimal training and test sets to build robust Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models.

Optimizing QSAR Training and Test Sets: A Practical Guide for Robust Model Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on selecting optimal training and test sets to build robust Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models. We explore foundational principles of dataset preparation, including data curation, molecular descriptor calculation, and handling of imbalanced datasets. Methodological sections detail practical splitting strategies, such as the Kennard-Stone algorithm and various cross-validation techniques, while addressing critical challenges like small dataset sizes and class imbalance. The guide further covers advanced troubleshooting and optimization approaches, including feature selection methods and applicability domain determination. Finally, we present a comparative analysis of validation protocols and performance metrics, emphasizing the importance of external validation and metrics tailored to specific research goals, such as positive predictive value for virtual screening. This holistic approach equips scientists with actionable strategies to enhance QSAR model reliability and predictive power in drug discovery applications.

Laying the Groundwork: Essential Principles of QSAR Data Preparation

FAQ: What constitutes the essential components of a reliable QSAR dataset?

A reliable QSAR dataset is built on three fundamental pillars: the chemical structures, the biological activity data, and the calculated molecular descriptors [1] [2]. The quality and management of these components directly determine the predictive power and reliability of the final QSAR model [1].

- Chemical Structures: The dataset must contain a curated set of chemical structures that are representative of the chemical space you intend to model. Structures should be standardized (e.g., removal of salts, normalization of tautomers) to ensure consistency [3].

- Biological Activities: This is the experimental endpoint you aim to predict (e.g., IC₅₀, EC₅₀). The data must be quantitative, of high quality, and ideally obtained from consistent experimental protocols to reduce noise [1] [2].

- Molecular Descriptors: These are numerical representations of the structural, physicochemical, or electronic properties of the molecules [3]. Descriptors should be precise, computationally feasible, and relevant to the biological activity being modeled to avoid the "garbage in, garbage out" situation [1].

FAQ: How should I split my dataset into training and test sets?

A proper split into training and test sets is critical for an unbiased evaluation of your model's predictive power. The test set must be reserved exclusively for the final model assessment and not used during model building or tuning [3]. The optimal ratio for splitting a dataset is not universal and can depend on the specific dataset, the types of descriptors, and the statistical methods used [4]. Below are common methodologies for data splitting.

Table 1: Common Methods for Splitting QSAR Datasets

| Method | Brief Description | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Random Selection | Compounds are randomly assigned to training and test sets. | Simple but may not ensure representativeness of the chemical space in the training set [4]. |

| Activity Sampling | Data is sorted by activity and split to ensure activity ranges are represented in both sets. | Helps maintain a similar distribution of activity values but may not capture structural diversity [4]. |

| Kennard-Stone | Selects training samples to uniformly cover the descriptor space. | Ensures the training set is structurally representative of the entire dataset [3]. |

| Based on Chemical Similarity | Uses algorithms like Self-Organizing Maps (SOM) or clustering to select diverse training compounds. | A rational approach based on the principle that similar structures have similar activities, helping to define the model's applicability domain [4]. |

The following workflow outlines the key steps in dataset preparation and splitting:

FAQ: What is the impact of training set size on model predictivity?

The size of the training set can significantly impact the predictive ability of a QSAR model, but the effect is not uniform across all projects [4]. A study exploring this issue found that for some datasets, reducing the training set size severely degraded prediction quality, while for others, the impact was less pronounced [4]. Therefore, no general rule exists for an optimal ratio, and the required training set size should be determined for each specific case, considering the complexity of the data and the modeling techniques used [4]. A common rule of thumb is to maintain a minimum ratio of 5:1 between the number of compounds in the training set and the number of descriptors used in the model to avoid overfitting [4].

FAQ: How do I ensure my QSAR model is robust and not the result of chance?

Robustness and the absence of chance correlation are fundamental to a reliable QSAR model. This is established through rigorous validation, which includes several key techniques [5]:

- Internal Validation (Robustness): This is typically done using cross-validation techniques like Leave-One-Out (LOO) or Leave-Many-Out (LMO) cross-validation. The result is often expressed as Q², which estimates the model's ability to predict data it was not directly trained on [4] [6].

- External Validation (Predictivity): This is the most crucial test, performed by predicting the activity of the external test set that was never used in model development. The predictive R² (R²pred) is calculated to quantify this performance [4] [5].

- Y-Scrambling (Chance Correlation): This technique tests for the possibility that a good-looking model arose by chance. The response variable (biological activity) is randomly shuffled, and new models are built. A valid model should perform significantly better than these models built on scrambled data [6] [5].

Table 2: Key Validation Parameters for QSAR Models

| Parameter | Formula | Purpose & Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| LOO Q² | Q² = 1 - [∑(Yobs - Ypred)² / ∑(Yobs - Ȳtraining)²] | Estimates model robustness via internal cross-validation. A value > 0.5 is generally acceptable [4]. |

| Predictive R² (R²pred) | R²pred = 1 - [∑(Ytest - Ypred)² / ∑(Ytest - Ȳtraining)²] | Measures true external predictivity on a test set. Higher values indicate better predictive power [4]. |

| Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) | RMSE = √[∑(Yobs - Ypred)² / n] | An absolute measure of the model's average prediction error. Lower values are better [6]. |

FAQ: What are common data quality issues and how can I troubleshoot them?

Problem: Poor Model Performance on External Test Set

- Possible Cause 1: The training set is not representative of the chemical space covered by the test set.

- Solution: Re-examine the data splitting method. Use a structure-based method like Kennard-Stone or clustering to ensure the training set covers the entire chemical space of your dataset [4].

- Possible Cause 2: The presence of outliers in the training data is skewing the model.

- Solution: Perform a careful analysis of the training set. Use cluster analysis of variables or quality control charts to identify and, if justified, remove outliers to build a more robust model [7].

Problem: Model Seems Overfitted (High R² for training but low Q²)

- Possible Cause: Too many molecular descriptors relative to the number of training compounds.

- Solution: Apply feature selection techniques (e.g., genetic algorithms, LASSO regression) to identify the most relevant descriptors. Adhere to the rule of thumb that the compound-to-descriptor ratio should be at least 5:1 [4] [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Software for QSAR

Table 3: Key Resources for Building QSAR Datasets and Models

| Tool / Resource Name | Category | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| PaDEL-Descriptor [3] | Descriptor Calculation | Software to calculate molecular descriptors and fingerprints from chemical structures. |

| Dragon [1] | Descriptor Calculation | Professional software for the calculation of a very large number of molecular descriptors. |

| OECD QSAR Toolbox [8] | Data & Profiling | Software designed to fill data gaps for chemical hazard assessment, including profiling and category formation. |

| RDKit [3] | Cheminformatics | An open-source toolkit for cheminformatics used for descriptor calculation, fingerprinting, and more. |

| k-fold Cross-Validation [3] [6] | Statistical Validation | A resampling procedure used to evaluate models on limited data samples, crucial for robustness testing. |

| Y-Randomization (Scrambling) [6] [5] | Statistical Validation | A method to test the validity of a QSAR model by randomizing the response variable to rule out chance correlation. |

For researchers in drug development, robust Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models are indispensable tools. The predictive power and reliability of these models hinge on a critical, often painstaking, preliminary step: the curation of the underlying chemical data. Errors or inconsistencies in data related to molecular structures and associated biological activities directly compromise model integrity, leading to unreliable predictions and wasted experimental effort. This guide addresses the most common data curation challenges—handling duplicates, managing missing values, and structural standardization—within the essential context of selecting optimal training and test sets for QSAR research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why is data curation especially critical for QSAR models used in virtual screening?

The primary goal of virtual screening is to identify a small number of promising hit compounds from ultra-large chemical libraries for expensive experimental testing. In this context, a model's Positive Predictive Value (PPV), or precision, becomes the most critical metric [9]. A high PPV ensures that among the top-ranked compounds selected for testing, a large proportion are true actives. Curating data to build models with high PPV, which may involve using imbalanced training sets that reflect the natural imbalance of large screening libraries, can lead to a hit rate at least 30% higher than models built on traditionally balanced datasets [9].

2. How does the size of the training set impact my QSAR model's predictability?

There is no single optimal ratio that applies to all projects. The impact of training set size on predictive quality is highly dependent on the specific dataset, the types of descriptors used, and the statistical methods employed [4]. One study found that for some datasets, reducing the training set size significantly harmed predictive ability, while for others, the effect was minimal [4]. The key is to ensure the training set is large and diverse enough to adequately represent the chemical space of interest. Best practices now often recommend using large datasets (thousands to tens of thousands of compounds) to enhance model robustness [10].

3. What is a fundamental principle for splitting my data into training and test sets?

The most rational approach for splitting data is based on the chemical structure and descriptor space, not random selection or simple activity ranking [4]. The training set should be representative of the entire chemical space covered by the full dataset. This helps ensure that the model can make reliable predictions for new compounds that are structurally similar to those it was trained on. Methods like the leverage approach define a model's "applicability domain," allowing you to assess whether a new compound falls within the structural space covered by the training set [11].

4. My EHR/clinical data has a lot of missing values. What is a robust and practical imputation method?

The optimal method can depend on the mechanism and proportion of missingness. However, for predictive models using data with frequent measurements (like vital signs in EHRs), Last Observation Carried Forward (LOCF) has been shown to be a simple and effective method, often outperforming more complex imputation techniques like random forest multiple imputation in terms of imputation error and predictive performance, all at a minimal computational cost [12]. For patient-reported outcome (PRO) data in clinical trials, Mixed Model for Repeated Measures (MMRM) and Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations (MICE) at the item level generally demonstrate lower bias and higher statistical power [13].

Troubleshooting Guides

Handling Duplicate Compounds

Problem: Duplicate entries for the same compound with conflicting activity data introduce noise and bias, weakening the model's ability to learn true structure-activity relationships.

Solution:

- Standardize Structures: Begin by converting all molecular representations (e.g., SMILES, InChI) into a standardized form. This includes removing salts, neutralizing charges, and generating canonical tautomers [10].

- Identify Duplicates: Use the standardized representations to find identical structures.

- Resolve Conflicts: For duplicates with differing activity values, apply a consistent rule.

- Preferred: Retain the data point from the most reliable source or the one measured with the most consistent protocol.

- Alternative: Calculate the mean or median of the activity values, provided the variance between them is low. If the variance is high, investigate the source of the discrepancy as it may indicate an underlying data quality issue.

- Deduplicate: Remove the redundant entries, keeping a single, canonical entry per unique compound.

Experimental Protocol for Data Deduplication:

- Tools: Utilize cheminformatics toolkits like RDKit or workflows within platforms like QSARtuna to automate structure standardization and duplicate identification [10].

- Data Sources: Assemble chemical-activity pairs from public databases like ChEMBL and PubChem, applying rigorous filters to ensure uniform activity scaling and remove duplicates [10].

- Documentation: Keep a record of the number of duplicates removed and the rules applied for conflict resolution. This ensures the process is transparent and reproducible.

Managing Missing Data

Problem: Missing values in biological activity or molecular descriptor fields can lead to the exclusion of valuable data (complete case analysis) or introduce bias if not handled properly.

Solution: The choice of method depends on the nature of your data and the modeling goal.

- Table 1: Comparison of Methods for Handling Missing Data

| Method | Description | Best For | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Last Observation Carried Forward (LOCF) | Fills a missing value with the last available measurement from the same subject/compound. | Time-series or longitudinal data with frequent measurements (e.g., EHR data) [12]. | A simple, efficient method that can be reasonable for predictive models, but may introduce bias if the value changes systematically over time. |

| Multiple Imputation (MICE) | Creates several complete datasets by modeling each variable with missing values as a function of other variables. | Complex datasets where data is Missing at Random (MAR). Shown to be effective for patient-reported outcomes (PROs) [13]. | Accounts for uncertainty in the imputed values. More computationally intensive than single imputation. |

| Mixed Model for Repeated Measures (MMRM) | A model-based approach that uses all available data without imputation, modeling the covariance structure of repeated measurements. | Longitudinal clinical trial data, especially for PROs [13]. | Does not require imputation, directly models the longitudinal correlation. Can be complex to implement. |

| Native ML Support | Using machine learning algorithms (e.g., tree-based methods like XGBoost) that can handle missing values internally without pre-imputation. | Large datasets with complex patterns of missingness [12]. | Avoids the potential bias introduced by a separate imputation step. Model performance is the primary metric for success. |

Experimental Protocol for Handling Missing Values in EHR Data for Clinical Prediction Models (Based on [12]):

- Data Preparation: Collapse raw, irregularly measured EHR data into clinically meaningful time windows (e.g., 4-hour blocks) using summary statistics (mean for numeric, mode for categorical variables).

- Method Selection & Implementation: For a pragmatic balance of performance and computational cost, consider implementing the LOCF method.

- Model Training & Evaluation: Train your clinical prediction model (e.g., for extubation success) on the dataset processed with the chosen imputation method. Evaluate its performance using metrics like balanced accuracy or mean squared error.

Structural Standardization and Representation

Problem: Inconsistent molecular representation (e.g., different salt forms, tautomers, or stereochemistry) leads the model to treat the same core structure as multiple different compounds, corrupting the learning process.

Solution:

- Remove Salts and Standardize Tautomers: Strip away counterions and represent molecules in a canonical tautomeric form [10].

- Calculate Diverse Descriptors: Generate a comprehensive set of molecular descriptors that capture relevant physicochemical and structural properties. This can include:

- Define Applicability Domain: Use methods like the leverage approach to establish the chemical space your model is valid for. This helps identify query compounds that are too dissimilar from the training set to be reliably predicted [11].

Experimental Protocol for QSAR Model Development (Based on [11]):

- Data Collection & Curation: Collect a dataset of compounds with experimentally measured activities (e.g., IC50). Apply structural standardization, handle duplicates, and address missing values.

- Descriptor Calculation & Selection: Calculate a pool of molecular descriptors. Use feature selection optimization strategies (e.g., ANOVA) to identify the most statistically significant descriptors for predicting activity [11].

- Data Splitting: Split the curated dataset into training and test sets using a rational method that ensures both sets cover similar chemical space. Avoid simple random splitting.

- Model Building & Validation: Develop models using both linear (e.g., Multiple Linear Regression - MLR) and non-linear (e.g., Artificial Neural Networks - ANN) techniques. Rigorously validate models using both internal (cross-validation) and external (test set) validation [11].

Workflow and Toolkit

Data Curation Workflow for Robust QSAR

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for curating data and developing a QSAR model, highlighting the stages where troubleshooting guides provide specific solutions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

- Table 2: Key Resources for QSAR Data Curation and Modeling

Item Function Example Tools & Databases Chemical Databases Source of chemical structures and associated biological activity data. ChEMBL [10], PubChem [10], eMolecules Explore [9] Cheminformatics Toolkits Software libraries for structure standardization, descriptor calculation, and molecular manipulation. RDKit [10], Mordred [10] Descriptor Calculation Software Generate numerical representations of molecular structures for model development. RDKit, Mordred, Integrated Platforms [10] Automated QSAR Platforms End-to-end workflows that help standardize the data curation and model building process. QSARtuna [10] Advanced Modeling Frameworks For implementing complex models like graph neural networks that can automate feature learning. PyTorch Geometric [10]

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs for Robust QSAR Research

This technical support center addresses common challenges researchers face when selecting molecular representations and building reliable Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models. The guidance is framed within the critical context of constructing optimal training and test sets for predictive and generalizable QSAR research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between traditional molecular descriptors and modern AI-driven representations?

Traditional molecular descriptors are pre-defined, rule-based numerical values that quantify specific physical, chemical, or topological properties of a molecule. Examples include molecular weight, calculated logP, HOMO/LUMO energies, and atom counts [14] [15]. They are computationally efficient and interpretable.

Modern AI-driven representations, learned by deep learning models like Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) or Transformers, are continuous, high-dimensional feature embeddings. These are derived directly from molecular data (e.g., SMILES strings or molecular graphs) and automatically capture intricate structure-property relationships without pre-defined rules, often leading to superior performance on complex tasks [14] [16].

Q2: My QSAR model performs well on the training data but poorly on the test set. What could be wrong?

This is a classic sign of overfitting and often relates to the data split and the nature of the molecular property landscape. The issue may be that your training and test sets have different distributions of Activity Cliffs (ACs). ACs are pairs of structurally similar molecules with large differences in activity, which violate the core QSAR principle and create a "rough" landscape that is difficult for models to learn [16].

To diagnose this, calculate landscape characterization indices like the Roughness Index (ROGI) or the Structure-Activity Landscape Index (SALI) for your dataset. A high density of ACs in the test set can explain the performance drop [16]. Ensuring your training set adequately represents these discontinuities or using representations that smooth the feature space can mitigate this problem.

Q3: For virtual screening of ultra-large libraries, should I balance my training dataset to have equal numbers of active and inactive compounds?

No. Traditional best practices that recommend dataset balancing for the highest Balanced Accuracy (BA) are not optimal for virtual screening [9]. In this context, the goal is to nominate a very small number of top-ranking compounds for experimental testing. Therefore, the key metric is Positive Predictive Value (PPV), or precision.

Training on imbalanced datasets that reflect the natural imbalance of large libraries (skewed heavily towards inactives) produces models with a higher PPV. This means a higher proportion of your top-scoring predictions will be true actives, leading to a significantly higher experimental hit rate—often 30% or more compared to models trained on balanced data [9].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Inconsistent or Poor Predictive Performance in 3D-QSAR Models

- Symptoms: Low cross-validated ( R^2 ) or ( Q^2 ), high prediction errors for the test set, model instability.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low predictive accuracy | Conformational selection and alignment | Ensure all molecules are in a global minimum energy conformation and use a consistent, biologically relevant alignment rule (e.g., based on the active site pharmacophore) [17] [18]. |

| Model not generalizing | Over-reliance on 2D descriptors in a "3D" model | Use true 3D descriptors (e.g., MoRSE descriptors, 3D-pharmacophores) that capture spatial information about the molecular field, as they can provide information not available in 2D representations [17] [19]. |

| High error for specific analogs | Presence of activity cliffs in the test set | Characterize the dataset using SALI or ROGI indices. Apply scaffold-based splitting to ensure structurally distinct molecules are in the test set, providing a more realistic assessment of generalizability [16]. |

Experimental Protocol: Developing a Robust 3D-QSAR Model using CoMSIA

This protocol outlines the key steps for building a Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA) model, as applied in the study of dipeptide-alkylated nitrogen-mustard compounds [18].

Dataset Curation and Preparation:

- Assemble a series of molecules with consistent core structures and known biological activities (e.g., IC50 values).

- Split into Training and Test Sets: Randomly divide the compounds, ensuring the test set is representative of the structural and activity diversity of the entire dataset. A common ratio is 80/20 for training/test.

Molecular Modeling and Conformational Alignment:

- Structure Building: Draw all molecular structures using software like ChemDraw.

- Geometry Optimization: Import structures into a program like HyperChem. Perform initial geometry optimization using a molecular mechanics force field (e.g., MM+), followed by more precise optimization using a semi-empirical quantum mechanical method (e.g., AM1 or PM3) until the root mean square gradient is below 0.01 kcal/(mol·Å) [18].

- Alignment: Superimpose all energetically minimized structures onto a common template molecule, typically the most active compound, based on a presumed pharmacophore or the core scaffold.

Descriptor Calculation and Model Building:

- CoMSIA Field Calculation: In software like Sybyl, calculate steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, and hydrogen-bond donor/acceptor similarity fields around the aligned molecules.

- Partial Least Squares (PLS) Analysis: Use PLS regression to correlate the CoMSIA fields with the biological activity data for the training set. The model is validated using leave-one-out (LOO) or leave-many-out (LMO) cross-validation to determine the optimal number of components and the cross-validated ( Q^2 ).

Model Validation and Application:

- Predict Test Set: Use the developed model to predict the activity of the external test set compounds that were excluded from model building.

- Contour Map Analysis: Interpret the 3D coefficient contour maps to identify regions in space where specific molecular properties (e.g., steric bulk, electropositive groups) enhance or diminish activity. Use these insights to design new compounds [18].

The workflow for this protocol is summarized in the following diagram:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

The following table details key computational tools and descriptors used in modern QSAR workflows, as referenced in the search results.

| Item Name | Function / Description | Application in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Extended-Connectivity Fingerprints (ECFP) | A circular fingerprint that encodes molecular substructures as integer identifiers, capturing features in a radius around each atom [16]. | Used for molecular similarity searching, clustering, and as input for machine learning models [14] [16]. |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | A class of deep learning models that operate directly on the graph structure of a molecule (atoms as nodes, bonds as edges) to learn data-driven representations [14] [16]. | Used for automatic feature learning and molecular property prediction, often outperforming traditional descriptors on complex tasks [14] [20]. |

| CoMSIA (Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis) | A 3D-QSAR method that evaluates similarity indices in molecular fields (steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, etc.) around aligned molecules [18]. | Used to build 3D-QSAR models and generate contour maps for visual interpretation and guidance in molecular design [18] [19]. |

| alvaDesc Molecular Descriptors | A software capable of calculating over 5,000 molecular descriptors encoding topological, geometric, and electronic information [14]. | Provides a comprehensive set of features for building QSAR models, as seen in the BoostSweet framework for predicting molecular sweetness [14]. |

| Topological Data Analysis (TDA) | A mathematical approach that studies the "shape" of data. In cheminformatics, it analyzes the topology of molecular feature spaces [16]. | Used to understand and predict which molecular representations will lead to better machine learning performance on a given dataset [16]. |

The decision process for selecting an appropriate molecular representation is guided by the problem context and data characteristics, as illustrated below:

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: How do dataset size and train/test split ratios influence the performance of my multiclass QSAR model? The size of your dataset and how you split it into training and testing sets are critical factors that significantly impact model performance, especially in multiclass classification.

- Experimental Evidence: A systematic study evaluating these factors with five different machine learning algorithms found clear differences in outcomes based on dataset size and, to a lesser extent, the train/test split ratio. The XGBoost algorithm was noted for its strong performance even in these complex scenarios [21].

- Quantitative Guidance: The study employed specific dataset sizes and split ratios, as summarized in the table below [21]:

| Factor | Values/Categories Investigated |

|---|---|

| Dataset Size (Number of samples) | 100, 500, [Total available data] |

| Train/Test Split Ratio | 50/50, 60/40, 70/30, 80/20 |

- Troubleshooting Tip: Do not assume a single split ratio is optimal for all projects. You should experimentally verify the best ratio for your specific dataset, as its effect can vary [21] [4].

FAQ 2: My dataset is imbalanced, with one activity class dominating the others. Should I always balance it before modeling? Not necessarily. The best approach depends on the primary goal of your QSAR model. The traditional practice of balancing datasets is being re-evaluated, particularly for virtual screening applications.

- For Virtual Screening (Hit Identification): If your goal is to screen ultra-large libraries to find active compounds, models trained on imbalanced datasets can be superior. The key metric here is Positive Predictive Value (PPV), which ensures a high hit rate among the top predictions. Studies show that such models can achieve a hit rate at least 30% higher than models built on balanced datasets when selecting the top compounds for testing [9].

- For Lead Optimization: If your goal is to refine a series of compounds and you need reliable predictions for both active and inactive classes, then striving for a balanced dataset and using metrics like Balanced Accuracy remains a sound strategy [9].

- Methodology: To handle imbalanced data, techniques like Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE) or clustering and undersampling the majority class can be employed [21].

FAQ 3: How can I quickly assess if my dataset is even suitable for building a predictive QSAR model? You can calculate the MODelability Index (MODI), a simple metric that estimates the feasibility of obtaining a predictive QSAR model for a binary classification dataset.

- Protocol:

- For every compound in your dataset, identify its first nearest neighbor (the most similar compound based on Euclidean distance in your descriptor space).

- Count how many compounds have their nearest neighbor in the same activity class.

- Calculate MODI using the formula:

MODI = (1 / Number of Classes) * Σ (Number of same-class neighbors for class i / Total compounds in class i)

- Interpretation: A MODI value above approximately 0.65 suggests your dataset is amenable to modeling with an acceptable correct classification rate (e.g., > 0.7). This metric helps identify datasets with too many "activity cliffs"—where very similar structures have different activities—which pose a major challenge for modeling [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Dataset Analysis

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function in Dataset Analysis |

|---|---|

| MODI (MODelability Index) | A pre-modeling diagnostic tool to quickly assess the feasibility of building a predictive QSAR model on a binary dataset [22]. |

| Gradient Boosting Machines (e.g., XGBoost) | A machine learning algorithm robust to descriptor intercorrelation and effective for modeling complex, non-linear structure-activity relationships [23]. |

| Text Mining (e.g., BioBERT) | A natural language processing tool used to automatically extract and consolidate experimental data from scientific literature (e.g., PubMed) for dataset construction [24]. |

| ToxPrint Chemotypes | A set of standardized chemical substructures used to characterize the chemical diversity of a dataset and identify substructures enriched in active compounds [24]. |

| Correlation Matrix | A diagnostic plot to visualize intercorrelation between molecular descriptors, helping to identify redundant features that could lead to model overfitting [23]. |

Experimental Protocols for Robust Dataset Handling

Protocol 1: Rational Data Curation and Consolidation for Model Development A high-quality, curated dataset is the foundation of any reliable QSAR model.

- 1. Data Collection: Gather data from public databases (e.g., ChEMBL, PubChem) and scientific literature. For literature, use text-mining tools like BioBERT, fine-tuned on annotated abstracts, to efficiently identify relevant studies and results [24].

- 2. Data Curation:

- Standardization: Convert structures to canonical SMILES, neutralize salts, and remove duplicates [24].

- Filtering: Remove mixtures, polymers, and inorganic compounds. Ensure experimental data complies with relevant OECD test guidelines (e.g., OECD 487 for in vitro micronucleus) [24].

- Conflict Resolution: Manually review and resolve conflicting data points for the same compound, retaining the result that best complies with current regulatory criteria [24].

- 3. Chemotype Analysis: Generate ToxPrint chemotypes for your curated dataset. Perform an enrichment analysis to identify substructures that are over-represented in active compounds, which helps understand the chemical space and structural alerts in your data [24].

Protocol 2: A Workflow for Assessing Dataset Modelability and Splitting This workflow helps you evaluate your dataset's potential and create meaningful training/test sets.

Key Experimental Pathways in Dataset Analysis

The following diagram outlines the logical process for handling class distribution, a central challenge in dataset preparation.

In Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling, the dataset forms the very foundation upon which reliable and predictive models are built. The quality, size, and composition of your dataset directly determine a model's ability to generalize beyond the compounds used in its development. The process of splitting this dataset into training and test sets is not merely a procedural step but a critical strategic decision that balances statistical power with practical constraints. As QSAR has evolved from using simple linear models with few descriptors to employing complex machine learning and deep learning algorithms capable of processing thousands of molecular descriptors, the requirements for adequate dataset sizing have become increasingly important. This technical guide addresses the fundamental challenges researchers face in dataset preparation and provides evidence-based protocols for optimizing this process to build more robust, predictive QSAR models.

Essential Concepts: Key Definitions and Principles

Applicability Domain (AD): The chemical space defined by the compounds in the training set and the model descriptors. Molecules within this domain are expected to have reliable predictions, while those outside it may have uncertain results [11] [25].

Balanced Accuracy (BA): A performance metric that averages the proportion of correct predictions for each class, particularly valuable when dealing with imbalanced datasets where one class significantly outnumbers the other [9].

Positive Predictive Value (PPV): Also known as precision, this metric indicates the proportion of positive predictions that are actually correct. It has become increasingly important for virtual screening applications where the goal is to minimize false positives in the top-ranked compounds [9].

Molecular Descriptors: Numerical representations of chemical structures that encode various properties, from simple atom counts to complex quantum chemical calculations. These serve as the input variables for QSAR models [1] [26].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Dataset Challenges and Solutions

FAQ 1: How large should my dataset be for a reliable QSAR model?

- Problem Context: Researcher has collected 50 compounds with measured activity and is unsure if this provides sufficient statistical power.

- Evidence-Based Guidance: While no universal minimum exists, dataset requirements vary significantly by model complexity. Traditional statistical methods like Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) may perform adequately with 20+ compounds, while Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) and other complex machine learning algorithms require substantially larger datasets [11] [1]. A representative bibliometric analysis of QSAR publications from 2014-2023 shows a clear trend toward larger datasets, with studies increasingly utilizing hundreds to thousands of compounds to ensure model robustness [1].

- Risk Assessment: Models built with insufficient data are highly prone to overfitting, where they perform well on training data but fail to predict new compounds accurately. Such models may show excellent internal validation metrics but poor external predictive power.

- Protocol Enhancement: When limited by small datasets, employ stricter validation protocols including leave-one-out cross-validation and y-scrambling to assess model robustness. Consider similarity-based methods like read-across or topological regression that may be more suitable for small datasets [27] [25].

FAQ 2: What is the optimal train/test split ratio for my dataset?

- Problem Context: Team is debating whether to use an 80/20 or 70/30 split for their dataset of 200 compounds.

- Evidence-Based Guidance: The optimal split ratio is highly dependent on total dataset size. Studies examining dataset size and split ratio effects found that with larger datasets (>1000 compounds), performance differences between common ratios (80/20, 70/30) become minimal. However, with smaller datasets (<200 compounds), more conservative splits (e.g., 70/30 or 60/40) that allocate more compounds to training may be beneficial [28].

- Performance Impact: Research comparing split ratios across multiple machine learning algorithms found statistically significant differences in model performance based on both dataset size and split ratios, with the effects being more pronounced for complex algorithms like XGBoost [28].

- Advanced Protocol: For datasets with limited compounds, implement nested cross-validation instead of a single train/test split. This approach maximizes data usage for both model building and validation while providing more robust performance estimates [28] [26].

FAQ 3: Should I balance my dataset if I have many more inactive compounds than actives?

- Problem Context: Virtual screening project has highly imbalanced data with 95% inactive compounds and seeks the best preprocessing approach.

- Paradigm Shift: Traditional best practices often recommended balancing datasets through undersampling of the majority class. However, recent research demonstrates that for virtual screening applications where the goal is identifying active compounds from large libraries, models trained on imbalanced datasets can achieve at least 30% higher hit rates in the top predictions [9].

- Metric Selection: When using imbalanced training sets for virtual screening, prioritize Positive Predictive Value (PPV) over Balanced Accuracy (BA) as your key performance metric. PPV directly measures the model's ability to correctly identify actives among its top predictions, which aligns with the practical objective of virtual screening campaigns [9].

- Implementation Guidance: For virtual screening applications, maintain the natural imbalance in your training data while focusing model optimization on PPV in the top ranking compounds (e.g., top 128 corresponding to a standard screening plate) [9].

FAQ 4: How does dataset size affect different machine learning algorithms?

- Problem Context: Research group needs to select the most appropriate algorithm for their dataset of 150 compounds.

- Algorithm Sensitivity: Studies comparing machine learning algorithms across different dataset sizes found that XGBoost consistently outperformed other algorithms including Random Forests, Support Vector Machines, and k-Nearest Neighbors, particularly for multiclass classification problems [28]. However, the performance advantage varies significantly with dataset size and split ratio.

- Quantum Advantage Emerging Research: Investigations into quantum machine learning for QSAR have found that quantum classifiers can outperform classical counterparts when dealing with limited data availability and reduced feature numbers, suggesting potential for specialized applications where data is scarce [29].

- Selection Framework: Match algorithm complexity to your dataset size. For smaller datasets (<200 compounds), prefer simpler models like Multiple Linear Regression or similarity-based methods. As dataset size increases (>500 compounds), more complex algorithms like ANN, XGBoost, or deep learning architectures become increasingly advantageous [11] [28] [26].

Quantitative Evidence: Dataset Size Impact on Model Performance

Table 1: Performance Metrics Across Dataset Sizes and Split Ratios

| Dataset Size | Split Ratio (Train:Test) | Algorithm | Key Performance Metrics | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 121 compounds [11] | 66:34 | Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) | R²: Reported | Direct comparison on NF-κB inhibitors |

| 121 compounds [11] | 66:34 | Artificial Neural Network [8.11.11.1] | R²: Reported | Superior reliability and prediction |

| 2710 compounds [28] | Multiple ratios (50:50 to 90:10) | XGBoost | 25 parameters calculated | Optimal for multiclass classification |

| 3592 compounds [30] | Not specified | Random Forest | RMSE: 0.71, R²: 0.53 | Toxicity prediction with large dataset |

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Modeling Approaches for Different Dataset Scenarios

| Scenario | Recommended Approach | Advantages | Limitations | Validation Priority |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small datasets (<100 compounds) | Topological regression, Read-across [27] [25] | Better interpretation, Less overfitting | Limited complexity | Applicability domain, Y-scrambling |

| Medium datasets (100-500 compounds) | Multiple Linear Regression, Random Forest [11] [26] | Balance of performance and interpretability | May not capture complex patterns | External validation, Cross-validation |

| Large datasets (>500 compounds) | ANN, Deep Learning, XGBoost [28] [26] | Captures complex non-linear relationships | Black box, Computational demands | External test set, Prospective validation |

| Imbalanced datasets (Virtual Screening) | Maintain natural imbalance [9] | Higher hit rates in top predictions | Requires PPV focus | PPV in top rankings, Experimental confirmation |

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for Optimal Dataset Utilization

Protocol 1: Systematic Approach to Train/Test Splitting

- Stratified Splitting: For classification problems, ensure that both training and test sets maintain similar distributions of activity classes to prevent bias [28] [1].

- Applicability Domain Definition: Use methods such as the leverage approach to define the chemical space of your training set. This helps identify when test compounds fall outside this domain and may have unreliable predictions [11].

- Iterative Splitting: For smaller datasets, implement multiple random splits (e.g., 5 different 80/20 splits) to assess the stability of model performance across different partitions [28].

- External Validation: Whenever possible, reserve a completely external validation set that is not used in any model building or parameter optimization steps [11] [25].

Protocol 2: Workflow for Dataset Size and Split Ratio Optimization

The following workflow provides a systematic approach to determining optimal dataset configuration:

Protocol 3: Handling Imbalanced Data for Virtual Screening

- Objective Alignment: If the primary goal is virtual screening to identify active compounds from large libraries, preserve the natural imbalance in your training data rather than balancing it [9].

- Metric Selection: Focus optimization and model selection on Positive Predictive Value (PPV) calculated for the top N predictions (where N matches your experimental throughput capacity, e.g., 128 compounds for a standard plate) [9].

- Performance Assessment: Compare models based on the number of true positives identified in the top predictions rather than overall balanced accuracy [9].

- Experimental Validation: Always plan for experimental confirmation of top-ranked predictions to validate the virtual screening approach [25].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for QSAR Dataset Preparation

Table 3: Key Computational Tools for Dataset Preparation and Modeling

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| PaDEL [27] [26] | Descriptor Calculator | Extracts molecular descriptors from structures | Standard workflow for feature generation |

| RDKit [27] [29] | Cheminformatics Toolkit | Calculates molecular descriptors and fingerprints | General purpose QSAR modeling |

| QSARINS [26] | Modeling Software | Classical QSAR development with validation | Educational purposes and traditional QSAR |

| Chemprop [27] | Deep Learning Framework | Message-passing neural networks for molecular properties | Complex datasets with non-linear relationships |

| OCHEM [30] | Online Platform | Multiple modeling methods and descriptor packages | Consensus modeling approaches |

| scikit-learn [26] | Machine Learning Library | Standard ML algorithms and validation methods | General purpose machine learning in QSAR |

The critical role of dataset size in QSAR modeling requires careful consideration of statistical power, model complexity, and practical research constraints. Evidence indicates that optimal train/test split ratios are dependent on overall dataset size, with different strategies needed for small, medium, and large datasets. Furthermore, the traditional practice of balancing datasets for virtual screening applications should be reconsidered in favor of maintaining natural imbalances when the goal is identifying active compounds from large chemical libraries. By implementing the systematic approaches and experimental protocols outlined in this guide, researchers can make informed decisions about dataset preparation that maximize model performance and predictive power within their practical constraints. As QSAR continues to evolve with advancements in artificial intelligence and quantum machine learning, these fundamental principles of dataset management will remain essential for building reliable, predictive models that accelerate drug discovery and materials development.

Strategic Data Splitting: Methods for Optimal Training-Test Partitioning

Frequently Asked Questions

1. Why shouldn't I just split my QSAR data randomly? Random splitting is a common starting point, but it can easily lead to over-optimistic performance estimates that do not reflect a model's real-world predictive power [31]. This happens due to "data leakage," where very similar compounds end up in both the training and test sets. A model may then simply memorize structural features from training compounds rather than learning generalizable rules, performing poorly when it encounters truly novel chemical scaffolds [32] [31]. For data with inherent autocorrelation, random splitting is particularly unreliable [31].

2. My dataset is relatively small. What is the best splitting approach?

For smaller datasets, the choice of splitting method is critical. While there is no universal rule for the optimal training/test set ratio, studies suggest that methods based on the chemical descriptor space (X-based) or a combination of descriptors and activity (X- and y-based) generally lead to models with better external predictivity compared to methods based on activity (y-based) alone [33]. If using random splits, it is highly recommended to perform multiple iterations and average the results to ensure stability [34].

3. How can I evaluate my model if the test set is imbalanced? Accuracy can be highly misleading for imbalanced datasets [35]. Instead, use Cohen's Kappa (κ), a metric that accounts for the possibility of agreement by chance [35]. The table below provides a standard interpretation for κ values.

| κ Value | Level of Agreement |

|---|---|

| 0.00 - 0.20 | None |

| 0.21 - 0.39 | Minimal |

| 0.40 - 0.59 | Weak |

| 0.60 - 0.79 | Moderate |

| 0.80 - 0.90 | Strong |

| 0.91 - 1.00 | Almost Perfect to Perfect |

Models with a κ value above 0.60 are generally considered useful [35].

4. In a federated learning environment, can I still use advanced splitting methods? Yes, but with specific constraints. Since chemical structures cannot be shared between partners, methods that require a centralized pool of all structures are not feasible [32]. However, approaches like locality-sensitive hashing (LSH), sphere exclusion clustering, and scaffold-based binning have been successfully applied in such privacy-preserving settings to ensure consistent splitting across partners [32].

Experimental Protocols for Data Splitting

The following protocols outline detailed methodologies for key splitting approaches cited in QSAR literature.

Protocol 1: Stratified Splitting to Counter Autocorrelation This protocol is designed for data where consecutive samples are highly similar, such as in time-series or structural data [31].

- Visualize the Data: Before splitting, plot your feature (

x) against the response (y) to visually check for autocorrelation or clear patterns [31]. - Create Strata: Instead of random points, divide the data into sequential chunks or "bins" along the feature axis. For example, split the data into 5 consecutive chunks [31].

- Assign Folds: Label each data point according to the chunk it belongs to [31].

- Split Data: For each validation round, use 4 chunks for training and the remaining 1 chunk for testing. This ensures the model is tested on a region of chemical or temporal space it has not seen during training [31].

- Validate: Compare the model's performance on this split with its performance on a random split. A significant drop in performance (e.g., R² from 0.97 to -1.15) indicates that the random split was giving an over-optimistic estimate [31].

Protocol 2: Scaffold-Based Splitting for Robust QSAR This method ensures the test set contains structurally distinct compounds by grouping molecules based on their core molecular scaffolds [32].

- Generate Scaffolds: For every compound in the dataset, compute its central molecular scaffold (e.g., using the Bemis-Murcko method) [32].

- Bin by Scaffold: Group all compounds that share an identical core scaffold into the same "bin" [32].

- Assign to Sets: Assign entire bins of compounds to either the training or test set. This guarantees that no compounds in the test set share a core scaffold with any compounds in the training set [32].

- Manage Size: Monitor the resulting split ratios, as assigning whole scaffolds may lead to an uneven distribution of data between the training and test sets [32].

Protocol 3: Comparison of Splitting Algorithms This protocol systematically evaluates the impact of different data splitting methods on model predictivity [33].

- Select Models: Choose several well-documented, reproducible QSAR models from the literature (e.g., from the JRC QMRF Database) [33].

- Define Splitting Methods: Apply multiple splitting algorithms to the same parent dataset. Common methods include [33]:

- Z:1 (

y-based): Sort by activity and select every Z-th compound for the test set. - Kennard-Stone (

X-based): Selects test compounds to be uniformly distributed across the descriptor space. - Duplex (

X-based): Selects test compounds to be both spread out and distant from training compounds.

- Z:1 (

- Rebuild and Validate: For each splitting method, rebuild the model using the new training set and calculate external validation statistics (e.g.,

Q²ₑₓₜandRMSEP) on the corresponding test set [33]. - Compare Results: Compare the validation statistics across all splitting methods. Studies show that

X-based methods (Kennard-Stone, Duplex) typically yield models with superior and more realistic external predictivity [33].

Performance Comparison of Splitting Methods

The table below summarizes key characteristics and performance insights of different data splitting approaches, helping you select the right method for your research.

| Method | Basis | Key Advantage | Key Disadvantage | Impact on External Predictivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Split | Chance | Simple, fast | High risk of data leakage and over-optimistic estimates [31] | Unreliable; can be highly exaggerated [31] [33] |

| Stratified Split | Feature/Response | Controls for autocorrelation; ensures representation | Requires careful definition of strata | More realistic than random for autocorrelated data [31] |

| Scaffold-Based | Molecular Structure | Tests ability to predict truly novel chemotypes; highly realistic | Can create imbalanced train/test set sizes [32] | High quality; provides a realistic assessment of generalizability [32] |

| Clustering-Based (e.g., Sphere Exclusion) | Chemical Space | Ensures structural distinctness between train and test sets | Computationally expensive in federated settings [32] | High quality; leads to robust external validation [32] |

| Kennard-Stone / Duplex | Descriptor Space (X) |

Optimizes representativeness and diversity of test set | More complex than random splitting | Better external predictivity compared to y-based methods [33] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Data Splitting

This table lists key computational tools and metrics essential for implementing robust data splitting in QSAR workflows.

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Cohen's Kappa (κ) | A performance metric that corrects for chance agreement, essential for evaluating models on imbalanced datasets [35]. |

| Concordance Correlation Coefficient (CCC) | A stringent external validation metric proposed as a more stable and prudent measure for a model's predictive ability [36]. |

| Molecular Descriptors (e.g., RDKit, Mordred) | Standardized numerical representations of molecular structures that form the basis for X-based splitting methods [10]. |

| Scaffold Network Algorithm | A method to bin compounds based on their molecular core structure, enabling scaffold-based splits to assess performance on novel chemotypes [32]. |

| Locality-Sensitive Hashing (LSH) | A clustering method suitable for privacy-preserving, federated learning environments where data cannot be centralized [32]. |

| Permutation Tests (Y-Scrambling) | A technique to validate models by randomizing response values; a robust model should fail when trained on scrambled data [4]. |

Data Splitting Selection Workflow

The following diagram illustrates a logical workflow to guide the selection of an appropriate data splitting method based on your dataset characteristics and research goals.

Data Splitting Method Decision Tree

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary advantage of using rational splitting methods like Kennard-Stone or Sphere Exclusion over random selection? Rational splitting methods systematically ensure that your training and test sets provide good coverage of the entire chemical space represented by your dataset. While random selection can lead to over-optimistic performance metrics, methods based on molecular descriptors (X) or a combination of descriptors and the response value (y) consistently lead to models with better external predictivity [33]. This is because they intelligently select a training set that is structurally representative of the whole set, ensuring the model learns a broader range of chemical features [37].

Q2: My dataset contains compounds from several distinct chemical classes. Which splitting method is most appropriate? For datasets with multiple chemical series, scaffold-based binning is a highly effective strategy [32]. This method groups compounds based on their molecular scaffold (core structure) before splitting. Allocating entire scaffolds to either the training or test set prevents information leakage that occurs when very similar structures are present in both sets. This approach avoids the "Kubinyi paradox," where models perform well in validation but fail in prospective forecasting because they were tested on structures too similar to their training set [32].

Q3: In a federated learning context where data cannot be centralized, can I still use these advanced splitting methods? Yes, but with specific considerations. Methods like locality-sensitive hashing (LSH) and scaffold-based binning are applicable in a privacy-preserving, federated setting because they can be run independently at each partner site or without sharing raw chemical structures [32]. However, clustering methods like sphere exclusion that require the computation of a complete, cross-partner similarity matrix are often computationally prohibitive in such environments due to the inability to co-locate sensitive data [32].

Q4: How does the size of my training set impact the model's predictive ability? The impact of training set size is dataset-dependent. For some datasets, reducing the training set size significantly degrades predictive ability, while for others, the effect is less pronounced [4]. There is no universal optimal ratio; the optimum size should be determined based on the specific dataset, the descriptors used, and the modeling algorithm. A general recommendation is to ensure the training set is large and diverse enough to adequately represent the chemical space you intend the model to cover [4].

Q5: Are there validated workflows for applying these algorithms to specific RNA targets? Yes, recent research has established workflows for building predictive QSAR models for RNA targets, such as the HIV-1 TAR element. These workflows involve calculating conformation-dependent 3D molecular descriptors, measuring binding parameters via surface plasmon resonance (SPR), and combining feature selection with multiple linear regression (MLR) to build robust models. This platform has been validated with new molecules and can be extended to different RNA targets [38].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Model Performs Well on Cross-Validation but Poorly on External Test Set

Potential Cause: The splitting method failed to ensure the training and test sets are structurally independent, leading to data leakage and over-optimistic internal validation. This is a common flaw of random splitting [32] [33].

| Solution | Description | Best For |

|---|---|---|

| Apply Scaffold Splitting | Group compounds by their Bemis-Murcko scaffolds and assign entire scaffolds to either the training or test set. This ensures structurally distinct sets. | Datasets with multiple, well-defined chemical series [32]. |

| Use Kennard-Stone Algorithm | Selects training set compounds to be uniformly distributed across the chemical space defined by the molecular descriptors. This ensures the training set is representative of the whole. | Creating a representative training set that covers the entire descriptor space [33]. |

| Validate Domain Applicability | Check that your test set compounds fall within the applicability domain of your model, defined by the chemical space of the training set. A large dissimilarity (>0.3 Tanimoto Coefficient) can indicate low prediction confidence [39]. | All models, as a final check before trusting predictions. |

Issue 2: Splitting Algorithm is Computationally Too Expensive for a Large Dataset

Potential Cause: Some algorithms, particularly certain clustering methods, have high computational complexity that does not scale well to very large datasets or federated learning environments [32].

| Solution | Description | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Use Directed Sphere Exclusion (DISE) | A modification of the Sphere Exclusion algorithm that generates a more even distribution of selected compounds and is designed to be applicable to very large data sets [40]. | Improves scalability over the standard sphere exclusion approach. |

| Apply Locality-Sensitive Hashing (LSH) | A federated privacy-preserving method that can approximate similarity and assign compounds to folds without a full similarity matrix [32]. | Reduces computational costs in distributed computing settings. |

| Opt for Scaffold Network Binning | A computationally efficient method that operates on molecular scaffolds rather than full fingerprint similarity [32]. | Provides a good balance between structural separation and compute time. |

Issue 3: Test Set is Not Representative of the Broader Chemical Space

Potential Cause: The splitting method was based solely on the response value (y) or failed to account for the overall distribution of molecular descriptors (X) [33].

Solution: Implement a splitting method that explicitly uses the molecular descriptor matrix (X) to select compounds.

- Method Choice: Use the Kennard-Stone algorithm or the duplex algorithm [33].

- Procedure: These algorithms select compounds for the training set that are uniformly distributed across the principal component space of your molecular descriptors. This guarantees that the training set is representative and that the test set compounds are close (in chemical space) to the training set, enabling more reliable predictions.

- Verification: Use Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to project your training and test sets into a 2D or 3D space. A visual inspection will confirm if both sets cover similar areas of the chemical space. The figure below illustrates a rational splitting method that ensures training and test sets are intermixed in chemical space, unlike an activity-only split.

Figure: A workflow for creating representative training and test sets based on chemical space coverage.

Quantitative Data Comparison

Table 1: Comparison of Key Dataset Splitting Algorithms

| Algorithm | Basis for Splitting | Key Advantage | Key Disadvantage | Impact on External Predictivity (Q²ₑₓₜ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random | Chance | Simple and fast to implement | High risk of non-representative splits and information leakage; over-optimistic validation [37] [33]. | Lower and less reliable compared to rational methods [33]. |

| Activity Sampling (Z:1) | Response value (y) only | Even distribution of activity values in both sets | Does not consider structural similarity; can lead to test compounds outside training chemical space [33]. | Lower than X-based or (X,y)-based methods [33]. |

| Kennard-Stone | Molecular descriptors (X) | Selects a training set uniformly covering the descriptor space [33]. | May not select outliers, which could be informative. | Leads to better external predictivity compared to y-only methods [33]. |

| Sphere Exclusion | Molecular descriptors (X) | Can control dissimilarity within the training set; DISE variant offers even distribution [40]. | Computationally expensive for very large datasets [32]. | High (when computationally feasible) [40]. |

| Scaffold Binning | Molecular scaffold | Creates structurally distinct training and test sets; ideal for multi-series datasets [32]. | Can lead to very uneven split ratios if one scaffold is dominant. | Provides a realistic assessment of model performance on novel scaffolds [32]. |

Table 2: Typical Binding Kinetics for RNA-Ligand Interactions (for Context in Validation)

| RNA-Ligand Set | Median kₒₙ (M⁻¹s⁻¹) | Median kₒff (s⁻¹) | Median Kd (M) |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA (in vitro-selected) | 8.1 × 10⁴ | 6.3 × 10⁻² | 4.3 × 10⁻⁷ |

| RNA (naturally occurring) | 5.5 × 10⁴ | 1.9 × 10⁻² | 3.0 × 10⁻⁷ |

| HIV-1 TAR–Ligand (as in [38]) | 3.8 × 10⁴ | 7.9 × 10⁻² | 5.0 × 10⁻⁶ |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing the Kennard-Stone Algorithm for Training Set Selection

This protocol is used to select a training set that is uniformly distributed over the chemical space defined by the molecular descriptors [33].

- Standardization: Standardize all molecular descriptors to have a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one to prevent scaling biases.

- Initial Point Selection: Identify the two compounds that are farthest apart in the descriptor space (i.e., have the maximum Euclidean distance). Add these to the training set.

- Iterative Selection: For each remaining compound in the dataset, calculate its distance to the nearest compound already in the training set.

- Maximize Minimum Distance: Select the compound with the largest of these minimum distances and add it to the training set.

- Repeat: Repeat steps 3 and 4 until the desired number of compounds has been selected for the training set. The remaining compounds form the test set.

Protocol 2: A Workflow for Building Predictive QSAR Models for RNA Targets

This validated workflow outlines the steps for building a predictive QSAR model, such as for the HIV-1 TAR RNA, incorporating advanced splitting and validation [38].

Compound Selection and Preparation:

- Select a diverse set of compounds covering multiple scaffolds (e.g., aminoglycosides, diphenyl furans, diminazenes) [38].

- Calculate a comprehensive set of molecular descriptors (e.g., topological, electrostatic, 3D). Account for possible protonation and tautomerization states by using Boltzmann-weighted averages of low-energy conformations [38].

Experimental Measurement of Binding Parameters:

- Measure binding affinity (Kd) and kinetic rate constants (kon, koff) using a technique like surface plasmon resonance (SPR). Ensure parameters span a wide range (e.g., 2 log units) for reliable modeling [38].

Data Splitting and Model Building:

- Split the dataset into training and test sets using a rational method like Kennard-Stone or Sphere Exclusion to ensure broad chemical space coverage [38] [33].

- Use multiple linear regression (MLR) combined with feature selection on the training set to build a model that correlates descriptors with binding parameters [38].

Model Validation and Application:

- Internal Validation: Validate model robustness using leave-one-out (LOO) cross-validation and y-scrambling to check for chance correlation [6] [4].

- External Validation: Test the model's predictive power on the held-out test set that was generated by the rational split. Use metrics like Q²F2 and RMSEP [6] [33].

- Prospective Prediction: Use the validated model to predict the activities of new, untested compounds [38].

Figure: A comprehensive workflow for building a predictive QSAR model, from data preparation to validation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Resources for Robust QSAR Modeling

| Item / Resource | Function / Purpose | Example / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Descriptor Software | Calculates physicochemical and topological descriptors from chemical structures. | Software like MOE (Molecular Operating Environment) can calculate 400+ descriptors and handle conformation-dependent 3D descriptors [38]. |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Measures binding affinity (Kd) and kinetic parameters (kₒₙ, kₒff) for biomolecular interactions. | Used to generate high-quality binding data for RNA-targeted small molecules, as demonstrated in HIV-1 TAR studies [38]. |

| Sphere Exclusion Algorithm | Clusters compounds based on molecular similarity to select diverse subsets. | Used to oversample inactive compounds from large databases like ChEMBL and PubChem for target prediction models [39]. The DISE variant offers improved distribution [40]. |

| Scaffold Network Analysis | Groups molecules by their core molecular framework (scaffold). | Essential for creating structurally distinct training and test splits in multi-series datasets and for federated learning [32]. |

| Naïve Bayes Classifier | A machine learning algorithm for target prediction and bioactivity classification. | Effective for large-scale target prediction models trained on millions of bioactivity data points, including inactive ones [39]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental reason for splitting my dataset into training, validation, and test sets? Splitting your dataset is crucial to prevent overfitting and to obtain an unbiased evaluation of your model's performance on new, unseen data. Using the same data for training and evaluation gives a false, overly optimistic impression of model accuracy. The training set teaches the model, the validation set is used for model selection and hyperparameter tuning, and the test set provides a final, unbiased assessment of generalization capability [41] [42] [43].

Q2: Is there a single, universally optimal train/validation/test split ratio? No, there is no universally optimal ratio. The best split depends on several factors, including the total size of your dataset, the complexity of your model (e.g., the number of parameters), and the level of noise in the data [44] [41]. However, some common starting points are 80/10/10 or 70/20/10 for large datasets, and 60/20/20 for smaller datasets [43].

Q3: How does the total dataset size influence the split ratio? With very large datasets (e.g., millions of samples), your validation and test sets can be a much smaller percentage (e.g., 1% or 0.5%) while still being statistically significant. For smaller datasets, a larger percentage is required for reliable evaluation, and you may need to use techniques like cross-validation to use the data more efficiently [44] [43]. Research shows that dataset size can significantly affect model outcome and performance parameters [21].

Q4: My dataset has imbalanced classes. How should I split it? For imbalanced datasets, a simple random split is not advisable as it may not preserve the class distribution in each set. You should use stratified splitting, which ensures that the relative proportion of each class is maintained across the training, validation, and test sets. This prevents bias and ensures the model is trained and evaluated on representative data [41] [42] [43].

Q5: What is cross-validation and when should I use it instead of a fixed split? Cross-validation (e.g., k-Fold Cross-Validation) is a technique where the data is repeatedly split into different training and validation sets. It is particularly useful when you have a limited amount of data, as it allows for a more robust estimate of model performance by using all data for both training and validation across multiple rounds. For QSAR regression models under model uncertainty, double cross-validation (nested cross-validation) has been shown to reliably and unbiasedly estimate prediction errors [45].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: High Variance in Model Performance Metrics

Problem: The reported accuracy or other performance metrics change dramatically when the model is trained or evaluated on different random splits of the data.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: Test set is too small. A small test set may not be statistically representative of the data distribution, leading to high variance in the performance statistic.

- Cause 2: Inadequate shuffle before splitting. If the data is not randomly shuffled, the splits might contain unintended biases or patterns.

- Solution: Always ensure your data is randomly shuffled before creating splits, unless working with time-series or grouped data [42].

Issue 2: Model is Overfitting

Problem: The model performs exceptionally well on the training data but poorly on the validation and test data.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: Training set is too small. The model cannot learn the general underlying patterns and instead memorizes the limited training examples.

- Cause 2: Over-tuning on the validation set. Repeatedly using the validation set to guide hyperparameter tuning can cause the model to overfit to the validation set.

Issue 3: Poor Performance on a Rare Class in an Imbalanced Dataset

Problem: The model has high overall accuracy but fails to predict instances of an under-represented class.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Improper splitting method. A random split may have placed a disproportionate number of the rare class into one set (e.g., the test set), leaving the model with too few examples to learn from during training.

Quantitative Data on Split Ratios and Performance

The following table summarizes findings from a systematic study investigating the effects of dataset size and split ratios on multiclass QSAR classification performance [21].

Table 1: Impact of Dataset Size and Split Ratios on Model Performance (Multiclass Classification)

| Factor | Levels / Values Investigated | Impact on Model Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Dataset Size | 100, 500, (and total set size) | Showed a clear and significant effect on model performance and classification outcomes. Larger datasets generally lead to more robust models [21]. |

| Train/Test Split Ratios | Multiple ratios were compared (e.g., 50/50, 60/40, 70/30, 80/20) | Exerted a significant, though lesser, effect on the test validation of models compared to dataset size. The optimal ratio can depend on the specific machine learning algorithm used [21]. |

| Machine Learning Algorithm | XGBoost, Naïve Bayes, SVM, Neural Networks (NN), Probabilistic NN (PNN) | XGBoost was found to outperform other algorithms, even in complex multiclass modeling scenarios. Algorithms were ranked differently based on the performance metric used [21]. |

For regression models with variable selection, double cross-validation has been systematically studied. The parameterization of the inner and outer loops significantly influences model quality.

Table 2: Key Considerations for Double Cross-Validation in QSAR/QSPR Regression [45]

| Cross-Validation Loop | Influenced Aspect | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| Inner Loop (Model Building & Selection) | Bias and Variance of the resulting models | The design of the inner loop (e.g., number of folds) must be carefully chosen as it directly affects the fundamental quality (bias and variance) of the models being produced [45]. |

| Outer Loop (Model Assessment) | Variability of the Prediction Error Estimate | The size of the test set in the outer loop primarily affects how much the final estimate of your model's prediction error will vary. A larger test set in the outer loop reduces this variability [45]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standard Data Splitting for a Typical QSAR Modeling Task

This protocol outlines a standard workflow for splitting data in a QSAR project, incorporating best practices for validation.

Diagram 1: Standard data splitting workflow.

Methodology:

- Data Preparation: Standardize molecular structures, calculate descriptors, and curate the final modeling dataset.

- Assess Class Distribution: Analyze the distribution of your response variable (e.g., active/inactive, or multiclass categories) to determine if the dataset is imbalanced [41].

- Shuffle: Randomly shuffle the entire dataset to remove any underlying ordering that could introduce bias [42].

- Split:

- Secure Test Set: Set the test set aside and do not use it for any further analysis until the final model evaluation.

Protocol 2: Double Cross-Validation for Robust Model Validation

This protocol is adapted from studies on reliable estimation of prediction errors under model uncertainty, common in QSAR with variable selection [45].

Diagram 2: Double cross-validation process.

Methodology:

- Outer Loop (Model Assessment): Split the entire dataset into ( k ) folds. For each iteration ( i ):

- Hold out fold ( i ) as the test set.

- Use the remaining ( k-1 ) folds as the training set for the inner loop.

- Inner Loop (Model Selection): On the training set from the outer loop, perform another cross-validation (e.g., 5-fold or 10-fold).

- This inner loop is used for hyperparameter tuning and variable selection.

- Identify the best model configuration based on the average performance in the inner loop.

- Final Assessment: Train a model on the entire ( k-1 ) training folds using the best configuration from the inner loop. Evaluate this model on the held-out outer test set (fold ( i )) to get an unbiased performance estimate.

- Repeat and Average: Repeat steps 1-3 for all ( k ) folds in the outer loop. The final model performance is the average of the performance across all outer test folds. This process validates the modeling procedure rather than a single final model [45].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Robust QSAR Validation

| Item / Solution | Function in Validation | Brief Explanation |

|---|---|---|